I. From Fiction to Science, from Science to Religion

A. Loss of Hope

With the Great Tōhoku Earthquake in 2011 and the resulting nuclear disaster in Fukushima, our pre-existing values [in JapanFootnote 2] were shaken and brought to collapse. Instead of thinking about development and progress, we shifted our attention to how to create a stable and sustainable society. “Desire less, be content” (shōyoku chisoku 少欲知足) became the catchphrase, and people stressed problems of heart and mind over economics. However, after some time, the values of old floated up once again. Abenomics, cries for “strong Japan”… People spoke of a return to tradition, but nobody took the time to sift through what this tradition might entail. With this, a thoughtless age of shortsighted living for the moment spread.

However, it is not the case that such a Zeitgeist arrived out of nowhere on 3/11. The “two lost decades” of economic stagnation had been going on since the 1990s, and the world as a whole seemed to be at an impasse. Several significant turning points of this [time] were the unification of East and West Germany in 1990, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, and the end of the Cold War. This at first seemed to represent the victory of capitalism and the end of the looming threat of war, but it was not to be. In the same year as the collapse of the Soviet Union, 1991, the Gulf War broke out, and the world was thrust into a state of chaos beyond the simple binary of capitalism versus socialism. It was in such a climate that Japan experienced the Hanshin Awaji Great Earthquake and the Aum Shinrikyo sarin gas attack in 1995.

Seen from the viewpoint of the history of thought, the fall of the Soviet Union is very significant. While for certain the reality of the Soviet Union was a long way off from its ideals, it was, at the very least, a movement that aimed to construct an ideal society by overcoming capitalism via Marxism. It had an ideal telos and a clear hope and aim in keeping this in view. Furthermore, this ideal was not merely a vision but was said to be a historical necessity, as seen from scientific historical principles.

Marxism had a great impact. If one takes the perspective that history is not a matter of chance but is ruled by certain principles, it becomes possible to have scientific pursuit in the social and historical sciences that is as rigorous as in the natural sciences. What drew intellectuals to Marxism were both the humanitarian idealism of realizing an equal society free from discrimination and its being the cutting-edge scientific theory of history. It was truly the vanguard. Marxist economics, Marxist historiography, all of these had strong positions (even in terms of university posts) in post-war academism [in Japan]. The idea of the stages of history – from primitive communism to ancient slave society, medieval feudalism, modern capitalism, and finally arriving at the communist society of the future – was seen as a principle of universal historical progress, applicable to all national histories. The core of the debate was how it might apply to actual history.

Even if one argued that the Soviet Union was far from ideal, the fact that at the very least there was a state that was built on the basis of these ideals and that the communist bloc was actually established was proof that Marxism could have actual power. People thought that even if the direction of the Soviet Union was mistaken, that was a mistake not of Marxist theory but of its interpretation. In either case, people considered it a given that capitalist society – unequal and founded on competition – is lacking something, and that it must be overcome in the future by the realization of an equal and peaceful socialist (communist) society. In this, one can see that there was a firm hope directed toward the ideals of the future.

Because of this, the fall of the Soviet Union and the collapse of the eastern bloc were much more significant than a mere change in the international status quo. The end of the Cold War by no means implied that Marxism and socialism were wrong and that capitalism was right. Nor did it mean that peace had arrived. Rather, the actuality of society showed growing inequality, wars became more complicated, the egos of nation-states crashed headlong into each other, and hope for resolution was nowhere to be found. It placed a huge question mark over the ideal of progress wherein humankind necessarily moves forward toward an ideal future of equality and peace. Fundamental doubts began to arise: Was the ideal society we had hoped for nothing but an unrealizable fiction? Was it but a dream? To begin with, to what extent can we grasp human endeavors like history and economics via reason and science? Is history really principled, lawful? Far from that, the 3/11 nuclear disaster put an end to the optimism that the progress of natural science leads directly to human happiness. We thought that things were moving “from fiction (superstition and religion) to science,” but that scientific worldview can no longer be said to be correct. Perhaps optimistic faith in science was also a kind of fiction?

If so, then ideas and philosophies that have previously been cast aside need to be brought back. If humankind has not necessarily progressed much, then the ideas of the past have by no means been simply “overcome.” [I think] it is necessary to bring back religion, which humankind has believed in and accumulated wisdom about for a long time. This does not mean the negation of science. But it is necessary to reconsider religion, remember its wisdom (which was thought to have been overcome by science), and see what we can retrieve from it.

B. Is It Right to Separate Religion and Politics?

If we are going to reconsider modern ratiocentrism, this implies that we can no longer indiscriminately force the givens of modernity – ideals like freedom, equality, rights, democracy – as some sort of golden rule. Here, I would like to consider the problem of secularism (the separation of religion and politics, or more commonly, “Church and state”). The principle of the separation of religion and politics is enshrined in Article 20 of the Japanese Constitution as follows:

Freedom of religion is guaranteed to all. No religious organization shall receive any privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority.

No person shall be compelled to take part in any religious act, celebration, rite or practice.

The State and its organs shall refrain from religious education or any other religious activity.Footnote 3

In this connection, Article 28 of the earlier Meiji Constitution had stipulated, “Japanese subjects shall, within limits not prejudicial to peace and order, and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects, enjoy freedom of religious belief.”Footnote 4 One quickly sees the erasure of the restriction “within limits not prejudicial to peace and order, and not antagonistic to their duties as subjects.” But not only that, I must point out that the present constitution's emphasis itself greatly differs. That is to say, guaranteeing “freedom of religion” is simple, but the emphasis is placed on the separation of religion and politics, as seen in “No religious organization shall receive any privileges from the State, nor exercise any political authority.” The second and third statements strengthen that, and the third particularly prohibits religious activities by the state.

As one can see, Article 20 of the current Japanese Constitution prohibits state involvement in religion and religion's interference with the state to an unusual extent. Supposedly, a fear of [the recurrence of] State Shinto is behind this. But in the first place, pre-war State Shinto was not a religion; since it was not a religion, the stipulation becomes pointless. In an actual case regarding the Shinto ground-breaking ceremony (jichinsai 地鎮祭) in Tsu city (ruled by the Supreme Court in 1977), the involvement of local government was accepted because ground-breaking ceremonies held in the Shinto way were seen as socially acceptable customary rites.

If so, then what is the stipulation in the constitution about? The strictest advocacy of the separation of religion and politics is the French idea of laïcité. Arguably, the Japanese Constitution was based on this. The principle of laïcité is not a simple matter of separating Church and state, but emphasizes the exclusion of religion from the state. This has its basis in the French Revolution. This revolution was based on the Enlightenment and its philosophical materialism, and one of its driving forces was an animosity toward religion. Similarly, while the Japanese Constitution may seem at the start to be about respect for religion, reading on, one cannot help but interpret it as an expulsion of religion from the state and politics – a form of anti-religion. If one actually examines the facilities for the victims of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, one is likely to find religious elements callously expunged.Footnote 5

This sort of secularism that excludes religion fits the materialist fixation on progress. And with this, there are people who criticize the involvement of some religions or religious groups in political issues as “unconstitutional,” as if to assert the rightness of abandoning the work of critically considering political problems. But this makes no sense. For example, in the case of peace, freedom, or equality, can we realize these purely in the realm of politics, without considering religious ideals? While freedom and equality seen from religion may seem different from these ideals in politics, it is unconvincing that these are completely disparate from each other. If religion does not provide politics with ideals, would political ideas of freedom and equality really exist? The idea that, given secularism, religions cannot or should not talk about political ideals is just a cop-out, a mere excuse for maintaining the status quo. For example, can one really say that there are no political elements implied in the criticism of nuclear energy from religious sectors?

In reality, the Nippon Kaigi 日本会議 (Japan Conference), which exerts a strong influence on conservative politics today, originally spun off from Seichō no Ie 生長の家 (House of Growth) and is known to have a strong sense of religiosity.Footnote 6 A clearer example of a political group with a religious base is the Shintō Seiji Renmei 神道政治連盟 (Shinto Association of Spiritual Leadership). Many conservative politicians belong to this association. The first article of its manifesto reads, “[We] resolve to establish the foundation of the Japanese government on the basis of Shinto spirit.” It clearly states the intention to found government on the basis of religious ideals. The Komeito Party 公明党 (Clean Government Party) – part of the ruling coalition party – is backed by Soka Gakkai 創価学会. Given that, one might say that today's ruling party is under the considerable influence of religion. Of course, this is not in violation of the separation of politics and religion in the constitution. It is not as if a religious group is directly “exercising political authority.” Even under secularism, it is perfectly possible for religion to supply politics with ideals.

These days, socially engaged Buddhism is attracting much attention. Originally this movement arose from monks protesting the war in Vietnam, giving this movement a strong sense of politicality. [However,] socially engaged Buddhism in Japan has a primarily apolitical social activist focus. Even when the religious were carrying out relief efforts after 3/11, they carefully avoided political criticism. The profession “Clinical Religious Worker” (rinshō shūkyōshi 臨床宗教師), which started in 3/11 and is beginning to take root in Japan, is also characterized by its apoliticality.

But is this a good thing? Is religion not originally supposed to give politics its ideals and sense of direction? In the global contemporary, after Marxist materialism has fallen, religion has come to possess great political significance. When we hear “religious fundamentalism,” militaristic evil immediately comes to mind, but are things really so simple? Religion originally begins from fundamental principles and rules. There may be religions that take war as a principle, but are there not also religions that take non-violence as their principle? We need to consider further the relationship between religion and the principle of peace.

C. Is Peace Universally Sought?

The contemporary idea of freedom and peace comes from the Peace of Augsburg (1555) and its continuity with the Treaty of Westphalia (1648), which ended the war between Catholics and Protestants. It is said that modern international law began here. However, this is a fruit of compromise, wherein not interfering with the content of religion is an expedient means of preventing war. Of course, such a compromise is necessary in reality. But as something that fails to enter into fundamental principles, it is a merely provisional [compromise].

The UNESCO Constitution (1945) is an example of an attempt to understand peace from the point of view of the essence of humankind. It tried to see a peace transcending political compromise, peace as something “in the minds of men.” Its preamble is as follows:

That since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed;

That ignorance of each other's ways and lives has been a common cause, throughout the history of mankind, of that suspicion and mistrust between the peoples of the world through which their differences have all too often broken into war;

That the great and terrible war which has now ended was a war made possible by the denial of the democratic principles of the dignity, equality and mutual respect of men, and by the propagation, in their place, through ignorance and prejudice, of the doctrine of the inequality of men and races;

That the wide diffusion of culture, and the education of humanity for justice and liberty and peace are indispensable to the dignity of man and constitute a sacred duty which all the nations must fulfil in a spirit of mutual assistance and concern;

That a peace based exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments would not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support of the peoples of the world, and that the peace must therefore be founded, if it is not to fail, upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind.Footnote 7

This expounds very lofty ideals. Peace must not be “based exclusively upon … political and economic arrangements.” The foundation of this peace must be placed in the “minds of men” and in “the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind.” This [preamble suggests that] war and inequality result from ignorance and prejudice. Therefore, a democratic peace founded on the “dignity, equality and mutual respect of men” must be built on the abovementioned solidarity. However, after seventy years, is this ideal really headed in the direction of its realization? Is the world not moving in the complete opposite direction? War and inequality do not merely arise from ignorance. It is because of this that they cannot be solved by intellectual enlightenment alone. If so, we need to rethink the view of humankind that is presupposed here.

Modeled after the UNESCO Constitution, the Japanese Constitution's preamble resoundingly advocates pacifism:

We, the Japanese people, desire peace for all time and are deeply conscious of the high ideals controlling human relationship, and we have determined to preserve our security and existence, trusting in the justice and faith of the peace-loving peoples of the world. We desire to occupy an honored place in an international society striving for the preservation of peace, and the banishment of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance for all time from the earth. We recognize that all peoples of the world have the right to live in peace, free from fear and want.

We believe that no nation is responsible to itself alone, but that laws of political morality are universal; and that obedience to such laws is incumbent upon all nations who would sustain their own sovereignty and justify their sovereign relationship with other nations.Footnote 8

Here, it acknowledges that “laws of political morality are universal,” and that abiding by these is “incumbent upon all nations.” However, this is based on “trusting in the justice and faith of the peace-loving peoples of the world,” and without that trust, it just does not work. Given that, we cannot really call these “universal” laws. Today, “preservation of peace, and the banishment of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance for all time from the earth” no longer hold currency at all. Is each country not “responsible to itself alone”? “Peace-loving” is no longer clearly self-evident and can no longer be called a universal law of humankind. If there is but one state that prioritizes its own expansion and strengthening over peace, this “universality” weakly crumbles.

Can peace and non-violence remain fundamental principles despite that? If they are to remain so, it is not in the domain of politics or “universal” reason, but perhaps in relation to the problem of religion. Should we rather seek the foundations of ethical problems not within the secular world but in the dimension that transcends it? In what way can religion, which transcends this world, found the ethics of this world? Or is this impossible? Is religion something that leads us to violence and the turmoil of war, or otherwise? It is an urgent and indispensable task for us today to rethink religion from its foundations.

II. The Problem of Views of Life and Death and the Other World

A. A New Ethics and View of the Next Life

One reason for the ethical conundrum we face today is that problems have become so big and complex that they can no longer be reduced to individual responsibility. A gigantic structure like a state includes individual responsibility via democracy but moves at a level far beyond individual control. Natural science also requires immense funding and large equipment to progress. It is as if the idyllic ethics of the UNESCO Constitution, where the “minds of men” move international relations, no longer holds sway.

However, despite that, the problems of the individual have not disappeared. To the contrary, the ethical problems grow: within such a large and incomprehensible structure, on what basis, what general principles, should individuals act? It is very difficult to swim free and firmly place one's foundations in what the authentic individual ought to do, instead of floundering in this gigantic world, tossed about by its waves. To make this possible, we need to truly return to the fundamental principles (genri gensoku 原理原則) of humanity and construct ethics from the ground up.

If so, problems cannot be restricted to the secular domain. Modernity has avoided problems of religion and theology. It has treated the secular world as if it could be resolved by the secular world alone. Kant cast out the problems of God and the soul from the domain of pure reason. This was not necessarily a victory of reason but rather a clarification of the limits of reason. Through the demands of practical reason, God and the soul ended up being reinstated. However, philosophy after Kant denigrated the problem of God and the soul, evicted anything inexplicable to science from the realm of reason, and reached its apex with materialism. Since nobody can prove [anything about] the problem of life after death, it was conveniently ignored.

But that is odd, is it not? This is something I have argued up to this point, and I will not repeat myself here. Instead, I would like to move forward a step and consider head-on the problems of what comes after death as well as the next life (raise 来世, also translatable as the afterlife or other world, lit. “coming world”). Perhaps some might tell me that these are matters of individual faith and thus pointless to discuss. But if so, is arguing only about things that everyone can [already] come to terms with really discourse? This is dangerous, just like it is dangerous to build peace on superficial compromises, without entering into the essence of religion.

For sure, the views of the next life differ according to religion. But one cannot obviate discussing views of the hereafter just because there are these differences. Human existence cannot be completed within this world alone. If you agree with this, then do we not need to think about the human being as a whole, including the part that goes beyond this life? This may be a theological or Buddhological problem, but that does not mean it is a problem we can afford to ignore. Of course, amidst that, we can keep materialism that negates the next life as an option [we can choose].

B. The Discourse in Modern Japan on the Next Life

Truth be told, Japan was not apathetic about the problem of what comes after death until after World War II. The afterlife (shigo 死後) was at the center of a heated debate in pre-war modernity. As Christianity was newly progressing, one important doctrine was “the immortal soul.”Footnote 9 The Christian theory that the soul is eternally immutable and heads to heaven or hell did not sit well with the Japanese. Furthermore, [Japan] was in the midst of taking up modern science. It was a big challenge for Christian missionaries as to how they could preach a theory like this in a way that was convincing. For example, Kashiwagi Gien 柏木 義円 (1860–1938), one of the leaders of Christianity during that time, wrote the following in The Theory of the Immortal Soul (Reikon fumetsu ron, 1908): “Spiritually, everyone yearns for his/her infinite growth (hatten 発展), but in this world, this is not completely reachable.”Footnote 10 Because of this, he argues for the necessity of the next life. This is slightly different from orthodox Christian doctrine, but is an interesting view that has some resonance with Buddhist Bodhisattvas.

The problem of the soul was also discussed in Buddhism, an early [example] being Kiyozawa Manshi's The Skeleton of Religious Philosophy (1892). But I draw attention to the Shin Bukkyō Dōshi Kai 新仏教同志会 (Association of New Buddhist Friends), who asked more than 180 religious and intellectuals about “the existence or non-existence of the upcoming next life (mirai raise 未来来世),” “the reason for judging its existence,” and “if it exists, what kind of state (jōkyō 状況) it would be.”Footnote 11 The responses of those from Buddhist circles were not always clear, and some took a roundabout way in order to avoid answering this question. Certainly, things are not so simple when it comes to the Buddhist view of the next life, but instead of deepening [their engagement with] this problem, modern Buddhists have decided to strengthen the direction of this-world-centrism (genseshugi 現世主義) and focus on living the present life well instead of longing for the next. Things like saṃsāra (the cycle of rebirth/transmigration) and rebirth in the Pure Land were seen as pre-modern superstitions, and perhaps circumstances caused them to seek to get away from that. Saṃsāra was also seen as a hotbed for discrimination [(i.e. the idea that lower castes are reborn that way because of their bad karma)], so they were trying to remove it from their doctrine.

In the midst of this, it was Yanagita Kunio 柳田 國男 who dealt head-on with the problem of Japan's particular view of the next life. Yanagita's About Our Ancestors (Senzo no hanashi 先祖の話) was written close to the defeat of Japan in World War II, in around May of 1945, and was published in that year. It was a troubling time; countless Japanese had died in the war. This book directly confronted the problem of how to commemorate (or enshrine, matsuru 祀る) the Japanese war dead. One problem Yanagita raised was that while it is also necessary for the state to commemorate the dead, as in the Yasukuni Shrine, that would not be enough to appease the war dead. Arguing the need for them to be brought home to their family graves, he argued for a recognition of home ancestral rites (sosen saishi 祖先祭祀). Yanagita tried to shed light on the ancient Japanese view of life and death prior to Buddhism and thought that the souls of the dead looked over their descendants, and gradually losing their individuality, merged with the ancestors and kami.

According to Yanagita, key characteristics of the Japanese view of the next life can be seen in four points: “[people] think that despite dying, the souls of the dead stay and do not go far,” “the communion (kōtsū 交通) between the worlds of the manifest (ken 顕) and the secluded (the dead, yū 幽) is rich,” thus the dead are not cut off from the present world. Furthermore, “the wishes at the last moment of life are certainly fulfilled after death,” and “many think that people can be reborn into similar undertakings.”Footnote 12 To an extent, these insights are persuasive, but they are not sufficiently proven.

In such a fashion, views on the next life were discussed even in modernity. But public discussions on this would come to a halt after the war. Perhaps one might say that the post-war rebuilding period was not a good fit for thinking about the problems of the next life. However, even after [Japanese] society restabilized itself to a degree, people continued to dodge these problems. In the twenty-first century, people have begun to discuss problems of how to pacify the spirits of the dead from the Tōhoku disaster, or how to deal with funerals and graves amidst a declining birthrate and an aging population. But we have yet to discuss the problem of our views of the next life.

Generally, the expression that “after death, one goes to heaven (tengoku 天国)” is widespread. But what is “heaven?” That remains unclear. Certainly, one can see the influence of Christianity here, but heaven is not seen as a world cut off from the present life, unlike in Christianity. As Yanagita says, [Japanese people] feel an affinity between this world and the next. This is similar to how many in contemporary Japan say “God (kami),” and the monotheistic God of Christianity compounds with the many kami of Japan, making matters vague. Many Japanese get married at a church, pledging their love before “God.” But this God does not conflict with the kami at a Shinto shrine. One might say that the general religious situation of present Japan is an amalgamation of Shinto, Buddhism, and Christianity (Shin Butsu Ki shūgō 神仏キ習合).

I have no intention of criticizing such a situation. To the contrary, I think it is strange to ignore and seal off the problems of our view of god/s and the next life. I think the problem of the other world needs to be posed directly.

C. The Vagueness of the Japanese View of the Next Life

The lack of clarity of the Japanese view of the next life and its multi-layering and vagueness are not new to modernity. The Japanese way of thinking was formed with the overlapping of various philosophies and religions entering Japan from the Asian continent and has an ambiguity that cannot be cleanly delineated by general principles and rules. In The History of Japanese Mortuary Practices (Nihon sōsei shi 日本葬制史) edited by Katsuda Itaru 勝田 至, he writes that in the Japanese view of the next life, there is an overlap between the following four views: first, there is no destination; second, one goes to a world separate from this; third, one's soul transmigrates and one is born as an animal or human being in this world; fourth, one remains in this world, albeit unseen.Footnote 13 This applies even today. For example, the idea that one goes to the world of the dead (heaven?) but returns during Obon (the Bon holidays) shows a crossing of the second and fourth ideas. Even though the dead are supposed to be in heaven, we think that when we visit their graves, they are there. The first idea rarely implies people clearly advocating materialism, but rather shows the spread of the view wherein one focuses on living this life without dwelling on the next life.

This sort of chaos and ambiguity was already a problem in late pre-modernity (kinsei 近世).Footnote 14 While Buddhism fundamentally teaches transmigration, Chinese ideas teach about life and death as the gathering and dispersal of qi 気 (Jp. ki) energy, allowing matters to be settled within this world with no need for recourse to another world. Buddhism and Daoism spoke about the next life/world, but this was not really something that intellectuals took up much. As a result, even in Japan, Confucians strongly tend to negate the existence of an afterlife. But one complicated issue here is that Confucianism stresses ancestor worship, making it impossible for them to view the souls of ancestors as completely ceasing to exist. Thus, they thought that the accumulation of qi must linger for a certain amount of time.

Masuho Zankō 増穂 残口 (1655–1742), a Nichiren monk who converted to Shinto and grew in popularity because of his sermons to the public, wrote “Because Japanese classics do not clearly teach the return of the soul to the Plain of High Heaven (Takamagahara 高天が原) and the way of the return of the soul, for a long time, the foolish men and women only heard of [the Buddhist teaching of] being reborn in hell or heaven, not knowing if it was true or false. The Confucian idea of the soul scattering and perishing is most majestic but unconvincing. People drift between Confucianism and Buddhism, relying on neither.”Footnote 15 In the view of life and death during that time, the Buddhist idea of heaven and hell and the Confucian idea of the scattering of the soul varied, and there were those who could not decide which to believe in, resulting in confusion. Because of this, he argued for the need to establish the ancient Japanese Shinto view of life and death.

That said, Zankō himself failed to come up with a clear view of life and death. Even Motoori Norinaga 本居 宣長 (1730–1801), who came later, seemed to have given up when he wrote, “Japanese believe that when one dies one just goes to the netherworld (Yominokuni よみの国), there is nothing to feel but sorrow, and nobody doubts this view.”Footnote 16 It was with Hirata Atsutane 平田 篤胤 (1776–1843) that there finally was a unique view of the next life where the land of the dead was part of this world. He wrote, “The region of the concealed [the dead] (meifu 冥府) is not separate from this realm of the manifest (Utsushikuni 顕国).”Footnote 17 Thus we see that the Japanese view of life and death was not really clearly established from the beginning but rather wavered beneath the influence of various thoughts and philosophies.

D. How Buddhism Sees the Next Life

In the case of Buddhism, was the idea of transmigration clearly established and accepted? For sure, the fundamental view of humanity in early Buddhism is a theory of saṃsāra on the basis of karma. Because Buddhists seek emancipation from the suffering of repeated transmigration in the six realms (hell, hungry ghosts, beasts, Asura [demi-gods], humans, gods), they idealize the spiritual practices of household-leavers, which leads to enlightenment and Nirvāṇa, a state of peace. The theory of transmigration was accepted in Japan, and it became the foundation of ethics. That is, if one does something bad in this life, in the next life one will be reborn into a miserable form. After Kyōkai's 景戒 Record of Japanese Wonders (Nihon ryōiki 日本霊異記, written in the Heian Period), this idea spread widely, and people believed in it until the late pre-modern period, or perhaps even until modernity. But this idea was criticized because it was taught that unhappiness in this life was a result of bad karma sown in the previous life – a way of thinking that justified discrimination. In Theravāda and Tibetan Buddhism, people take transmigration as a presupposition even until today. According to this principle, the only way to be liberated from the cycle of rebirth is to become a household-leaver (monk) and carry out spiritual practices. Because of this, laypersons cannot attain liberation. [All they can] do is accumulate good karma and hope to be reborn in better circumstances in the next life where they can conduct spiritual cultivation. And even for monks, attaining Nirvāṇa is far from easy. One needs to be repeatedly reborn and slowly draw closer to Nirvāṇa.

However, in Japanese Buddhism, these fundamental principles do not hold much water because enlightenment and Nirvāṇa came to be considered as easily attainable. For example, in Mikkyō 密教 (esoteric Buddhism), the philosophy of “Attaining Buddhahood in this Body” (sokushin jōbutsu 即身成仏) developed, and it was considered possible to attain enlightenment and become a buddha in this life. In Zen, according to the idea of sudden enlightenment (tongo 頓悟), it was considered possible to attain enlightenment through spiritual cultivation in this life. This thought traces back to China, and fits with China's this-world-centrism. Furthermore, the idea of rebirth in the Pure Land became widely accepted. This idea recognizes the next life, but it is not a cycle of transmigration. Instead, one is reborn in the Pure Land of Amida Buddha.

Does that mean that Mikkyō and Zen do not talk about the next life? That is not the case. If one fails to attain Buddhahood in this life, one hopes to attain it in the next. And here it is possible to have an eclectic idea of being born in the Pure Land first [to aid future practice]. For memorial services (kuyō 供養) for the dead to be meaningful, there arose the idea of a possibility of offering the good karma of the living to the dead and thus helping lost spirits attain Buddhahood. In this way, Buddhism [also] possesses this-world-centric tendencies and a plurality of views of the next life. It does not necessarily have clear and set principles [on the afterlife].

III. The Possibility of Bodhisattva Ethics

A. The Formation of Bodhisattva Philosophy

As we see above, the Japanese view of the next life is by no means clear and fixed. This is not a denial of the next life, but rather, various ideas about it overlap, resulting in ambiguity. This vagueness is not necessarily a bad thing. But might it be possible instead to come up with a more constructive (sekkyokuteki 積極的) view of the next life on the basis of the fundamental doctrines of Buddhism? Next, I would like to return to the origins of Mahāyāna Buddhism and give this idea some thought.

Originally, the fundamental principle of Buddhism is “reaping what you sow” (jigō jitoku 自業自得). This means that the suffering of saṃsāra arises as a result of one's own karma (actions). The only way to be free from this suffering is one's own spiritual cultivation and enlightenment. The root of suffering is avidyā (fundamental ignorance), and the path from ignorance to suffering is explained as the twelve-fold path of dependent origination (dvādaśāṅgika-pratītyasamutpāda). This is a problem thoroughly concerned with the way of being of the self, and there is no room for the other to have any part in it.

However, in actuality, one is not completely disconnected from others. In the first place, one does not carry out spiritual cultivation in isolation. One forms and participates in the shared life of the sangha (monastic community) and practices under the guidance of the Buddha. In order to keep the sangha together, the precepts were formed as shared rules – a form of sociality. Furthermore, for spiritual practitioners to focus on their practice, they need to rely on laypersons for their daily necessities like food. This created a new relationship between the community of household-leavers and lay believers. For lay believers, believing in the Buddha and the sangha and trying to help them are the highest form of good karma. So, from the beginning, there was a relationship with others.

There is another considerable problem here: the truth may be immutable, but the one who discovered that truth and taught it through words is Śākyamuni Buddha. If Buddha had not taught the truth, his disciples would not have been able to practice and attain enlightenment. This is why Buddha, the preacher of the dharma, is seen as special. If enlightenment is a matter for the self, then there is nothing that necessitates teaching it – others should discover the truth for themselves. However, Buddha and his disciples spread the teachings, thus spreading the Buddhist order around India and beyond.

As we see above, in principle “you reap what you sow.” But, in actuality, we are thrust into relationships with others whether we like it or not, in a way that cannot be explained by general principles alone. This became even stronger in the Buddhist order after Śākyamuni's death. The truth did not change with Buddha's passing, so nothing should have changed. But despite this, faith in the departed Buddha became stronger and stronger, and stūpas containing relics of Buddha became sacred sites and objects of worship.

With the ascent of Buddha into a sacred figure, episodes of his life were developed as stories, and his previous lives were told as the Jātaka Tales. These are stories of Buddha's spiritual cultivation, based on the presupposition that for Buddha to have attained enlightenment, his practices in his last life alone would not have been sufficient – he must have practiced for it in the past, over countless turns of the cycle of transmigration. This Buddha “in training” is referred to as a “bodhisattva,” which means a sentient being (sattva) that seeks awakening (bodhi). This is not restricted to human beings. Sentient beings take various forms in the six worlds and the human form is but one.

This spiritual cultivation was eventually compiled as the six perfections (pāramitā) – generosity (dāna), virtue (śīla), patience (kṣānti), diligence (vīrya), contemplation (dhyāna), and wisdom (prajñā) – six virtues that are practiced to completion. Amongst these, generosity is particularly stressed, and is often the subject of stories in the Jātaka Tales. In the famous story of King Sibi, who was a previous incarnation of Buddha, in order to save a dove being chased by a falcon, King Sibi offered his body in exchange for the dove's. This total generosity is seen to be the most important spiritual practice of a bodhisattva. If so, there is no ignoring one's relationship with the other. More accurately, the relationship with the other becomes the greatest fundamental principle.

As we see above, originally, “bodhisattva” referred to Buddha in his previous lives as he cultivated himself and sought enlightenment. But eventually the idea came about that anyone could be a buddha – although this remained an arduous task. Originally, “buddha” meant the world's greatest spiritual leader, and so only one buddha could exist in each age. In the past, there were seven buddhas, including Śākyamuni. In the future, supposedly, it is Maitreya who will appear. Because of this, it is not possible to have other buddhas. However, “buddha” is originally a generic appellation for anyone enlightened, and so it should be possible for any spiritual practitioner (even other sentient beings) to become a buddha. This is a great contradiction.

What resolved this contradiction was the arrival of a completely new way of thinking – that there could be worlds outside of this one, and so one could attain buddhahood. The domain of spiritual leadership of one buddha (a buddha-land, buddhakṣetra) is 10003 worlds (Trisāhasramahāsāhasralokadhātu), which is a billion worlds (with each world centered around Mount Sumeru). If a Mount Sumeru world is a planet like earth, a billion worlds are something like the universe. (That being said, in actuality, the Milky Way alone has 200 billion stars, and so the number of planets in the universe is far greater.) This is the sahā world over which Śākyamuni presides. A separate buddha-land would mean a world outside of this buddha-land – a universe outside the universe. If there are countless universes outside of this universe and one can attain buddhahood there, then one can have countless buddhas without violating the principle of one-world-one-age-one-buddha. It was by recognizing the idea of universes outside the universe (multiple buddha-lands) that the Mahāyāna idea of multiple buddhas became possible.

One example of another buddha-land is Amida Buddha's paradise (the Pure Land). It supposedly lies to the west of the sahā world, ten billion lands away. With the coming of modernity, this idea was thought to be pre-modern, an unscientific superstition, something to sneer at. But if one recognizes the existence of a multiverse, this idea is not impossible. But the key issue here is not whether it is scientifically recognizable. What we need to focus on here is its multi-layeredness – this world is placed after death, and while its distance from the present world is maintained, it does not lose its relationship with this life. The dead are both so far away from the living, yet they continue to relate with us.

However, Amida Buddha is special, a buddha, quite different from ordinary sentient beings. One might ask, even though one recognizes the possibility of buddhas in other worlds, are they not buddha-saviors completely unrelated to our way of existence? True, in the Infinite Life Sutra (Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, Muryōju Kyō) we use today, this might be so. But in the older Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra (Dai Amida Kyō) extant only in Chinese translation, there is a story of “The Prophecy of Prince Ajātaśatru.” When Prince Ajātaśatru (Ajase Taishi) heard Śākyamuni Buddha's preaching on Amida Buddha, he begged to become like Amida, and Śākyamuni Buddha prophesied that indeed he would become so in the future.Footnote 18 In other words, while Amida Buddha may be a savior, he is also a pattern showing that even ordinary fools (bonpu) can become like him, so long as they will it. A buddha is the completed form of a bodhisattva. One who is in the process of spiritual cultivation as a bodhisattva first takes a vow (seigan 誓願) and is recognized by the Buddha, and then proceeds to his/her self-cultivation. Amida Buddha walked the same path as Bodhisattva Dharmākara (Hōzō Bosatsu) and was able to save sentient beings. Just like him, anyone can take a vow and walk the path of a bodhisattva.

As we see above, the praxis of bodhisattvas became the core of Mahāyāna Buddhism. In order to look deeper into the inner insights of this, allow me to summarize the fundamental character that has come to light.

First, the praxis of bodhisattvas presupposes relating with the other. Benefiting others (rita 利他) is impossible without the other. While practice in early Buddhism began and ended with the solitary individual, the praxis of bodhisattvas is characterized by its being placed within the relation with the other.

Second, the praxis of bodhisattvas cannot be completed in this world/life (gense 現世) alone. It continues from distant past-lives to distant future lives. Furthermore, spatially it is not restricted to this universe (buddha-land) but extends to universes beyond. This can be said to be fantastical, and some may think it a form of escapism even. But the important point here is that ethics is not completed within this life alone.

B. The Bodhisattva Theory of the Lotus Sutra I: “Bodhisattva as Existence” in Part I

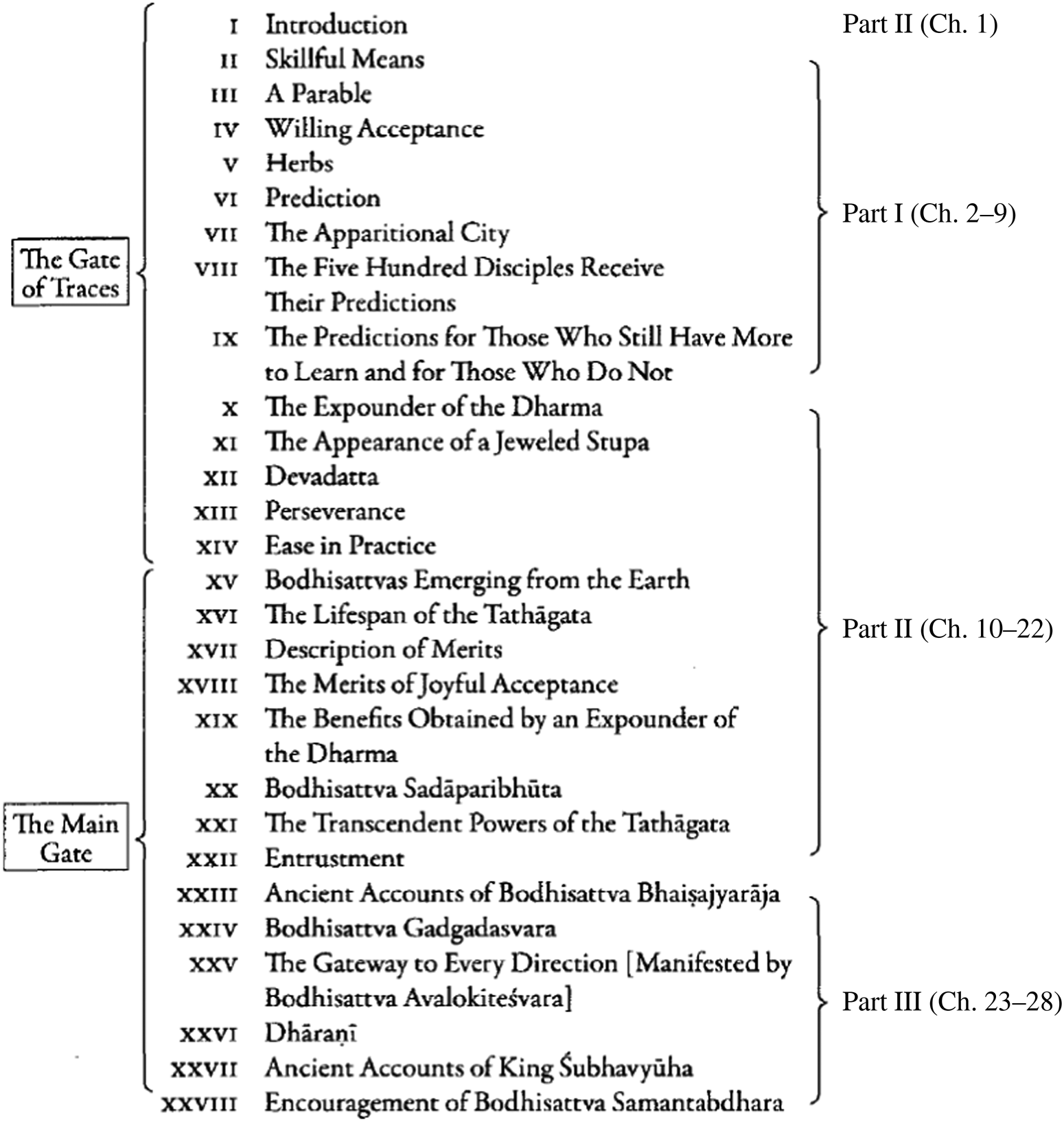

The quintessential exposition of the way of being of a Mahāyāna bodhisattva can be found in the Lotus Sutra.Footnote 19 This sutra has twenty-eight chapters, and is traditionally separated into two parts: the first half is called the “gate of traces” (shakumon 迹門) and the latter the “main gate” (honmon 本門). However, modern research divides it into three according to date of compilation: the first part is from “Chapter II. Skillful Means” to “Chapter IX. The Predictions for Those Who Still Have More to Learn and for Those Who Do Not”; the second from “Chapter X. The Expounder of the Dharma” to “Chapter XXII. Entrustment”; and the third part from “Chapter XXIII. Ancient Accounts of Bodhisattva Bhaiṣajyarāja” to “Chapter XXVIII. Encouragement of Bodhisattva Samantabhadra.” The third part records the activities of various bodhisattvas and is regarded as a later addition. Thus, the first two parts are considered central. These two parts are thought to have been compiled separately, but there is another theory that suggests they were made to be consistent with each other. I will not go into these authorial details here.

The core of the first part is usually thought to be “Skillful Means,” and it supposedly suggests that the theory of the three vehicles (śrāvaka, pratyekabuddha, and bodhisattva vehicles) that separates Theravāda and Mahāyāna Buddhism are actually one Buddha vehicle (esan kiitsu 会三帰一, “opening three and revealing one”). The core of the second part is “The Lifespan of the Tathāgata,” which clarifies that the true form of Śākyamuni Buddha is eternal (Kuon no Shaka 久遠の釈迦, the Eternal Buddha). It is possible to read it this way, but if one reads it without assumptions, one begins to see other facets.

Kariya Sadahiko 苅谷 定彦 formulates the central philosophy of the first part as follows: “All sentient beings are bodhisattvas.”Footnote 20 The fundamental idea of the chapter on “Expedient Means” is that all sentient beings can become buddhas, and Kariya's formula can be seen as a rewording of this. However, as I previously mentioned, bodhisattvas cannot be what they are without relating with others, given that “All sentient beings are bodhisattvas” suggests none other than that “no sentient being can exist without relating with the other.”

As one can see in the book [that this chapter is a part of], while the other is not reducible to our understanding, he/she is someone we cannot help but relate with. We cannot even exist without our relation to such an other. [And] the other is not necessarily the kind of other I hope for. The other is not necessarily nice to me. Sometimes, the other hurts me, bearing me ill will, or annoys me and frustrates me, stirring up various emotions. This may give rise even to suffering. But even so, one must relate to the other. What absurdity is this! “All sentient beings are bodhisattvas” implies accepting one's relationship with the other together with these downsides (and also upsides).

Let us call this way of considering that all sentient beings cannot but be bodhisattvas as “bodhisattva as existence” (sonzai toshite no bosatsu 存在としての菩薩). Recognizing “bodhisattva as existence” is the very task of Part I of the Lotus Sutra. On the other hand, the task of Part II is “bodhisattva as praxis” (jissen toshite no bosatsu 実践としての菩薩), finding out how to make the former proceed in a positive direction.

In order to think of Part I from the point of view of “bodhisattva as existence,” one needs to include not merely “Chapter II. Skillful Means” but also “Chapter III. A Parable” until “Chapter IX. The Predictions for Those Who Still Have More to Learn and for Those Who Do Not.” What we see in these chapters is the teaching on “Predictions for Śrāvakas” (shōmon juki 声聞授記). Śrāvakas, disciples of the Buddha who were content with the teachings of the “lesser vehicle” (Hīnayāna), were encouraged to realize that they are actually bodhisattvas, and received the prediction from Buddha that they too would become buddhas. This used to be interpreted as a mere addendum to the teaching of “opening three and revealing one” (that the three vehicles/schools return to one vehicle) and not given much weight. However, this is actually of great importance. Let us examine this more closely.

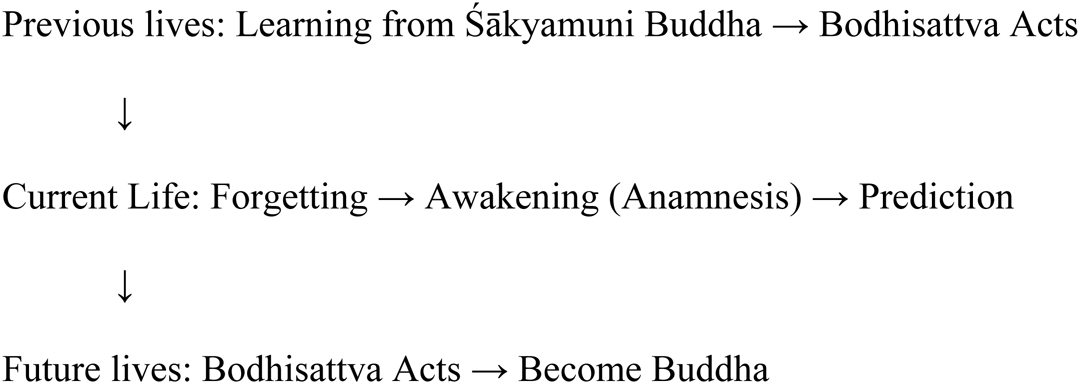

“A Parable” discusses Śāriputra, and in “Chapter IV. Willing Acceptance,” “Chapter V. Herbs,” and “Chapter VI. Prediction,” the four great Śrāvakas (Subhūti, Mahākatyāyana, Mahākāśyapa, and Maudgalyāyana) make an appearance. In “Chapter VII. The Apparitional City” and “Chapter VIII. The Five Hundred Disciples Receive Their Predictions,” Pūrṇa and 500 śrāvakas come up, and in “Chapter IX. The Predictions for Those Who Still Have More to Learn and for Those Who Do Not,” Ānanda, Rāhula, and 2000 śrāvakas … all the important disciples of Buddha are included. Buddha and his disciples trade questions and answers, much like in Plato's Dialogues. Taking “A Parable” as an example, Buddha instructs Śāriputra as follows: “In the presence of two hundred thousand koṭis of buddhas, I led and inspired you constantly for the sake of the highest path. You have followed my instructions for a long time.… Yet just now you had completely forgotten this and considered yourself to have attained nirvāṇa.”Footnote 21 Śāriputra came to a realization of this, and Śākyamuni Buddha prophesied that in the future, Śāriputra would attain enlightenment.

In this story we see Śākyamuni going back two hundred thousand koṭis of buddhas ago to constantly be the other to Śāriputra, relentlessly pursuing him. The relationship with the other is not merely about this life but continues from an infinite past to an infinite future. Śāriputra had forgotten that he was a bodhisattva. But Śākyamuni's teaching helped him remember, and he came into awareness of himself as a bodhisattva. This is quite similar to the Platonic theory of “anamnesis” (recollection of the world of ideas).

Figure 1. The structure of the Lotus Sutra.

C. The Bodhisattva Theory of the Lotus Sutra II: “Bodhisattva as Praxis” in Part II

Part II starts with “Chapter X. The Expounder of the Dharma.” At this point, the topic suddenly shifts to [matters] after the death of Śākyamuni. If Part I was about Śākyamuni being “the Buddha as the other,” Part II was about him being “the Buddha as the departed” (shisha toshite no Budda 死者としてのブッダ). As we have seen, compared to various kinds of “others,” the dead are the most other of others. This is the core problem of how to deal with the departed, how to relate with others. The departed Śākyamuni in Part II is none other than the representative of the dead.

In “The Expounder of the Dharma,” it is recommended that in order to practice as a bodhisattva after Śākyamuni's passing, one ought to remember, read, chant, explain, and transcribe the Lotus Sutra – the five kinds of expounding the dharma (goshu hōshi 五種法師). The Lotus Sutra is often criticized for constantly extolling its own virtues. However, after Śākyamuni's passing, The Lotus Sutra itself becomes the Buddha. How is that possible? What is death, and what are the dead? A hint to unravel these mysteries is “Chapter XI. The Appearance of a Jeweled Stupa.” In this chapter, a stupa (or a pagoda) appears, and within it we find Prabhūtaratna sitting in meditation, mummified. It is the Buddha as the departed. This dead Buddha appears in order to give praise to Śākyamuni, who was teaching the Lotus Sutra. Śākyamuni enters that stupa and sits beside Prabhūtaratna, and the rest of the sermon is carried out from within this stupa floating in the air.

Figure 2. Bodhisattva works, prediction, and becoming Buddha.

In this way, Śākyamuni becomes one with the departed Prabhūtaratna. Śākyamuni, who was about to enter nirvāṇa, unifies with the dead and manifests his full power even prior to his death. This is the unification of the power of the living and the dead. “The Lifespan of the Tathāgata” is the heart of Part II, and here Śākyamuni reveals that his ordinary human form that he had been showing was an “expedient means” (hōben 方便), and manifests his real form as “kuon jitsujō 久遠実成” (the Buddha Truly Attained in the Distant Past). This is true, but I think the important part is that Śākyamuni arrives at this eternity by unifying with the dead Prabhūtaratna. The living need the dead and the dead need the living. It is when the two become one that the authentic workings of both are manifest. And through this, even though Śākyamuni passes away, he becomes the undying Buddha. “Kuon jitsujō” is not a transcendence into some one-dimensional eternity, but rather becoming one who can work drawing from the greatest wellspring of energy by becoming one with the dead. That working is none other than the material manifestation of the Lotus Sutra. This is the profound mystery of Buddha revealed in Part II. By the Buddha as other deepening into the Buddha as the departed, Buddha is able to function beyond the framework of this world. This was presaged in Part I with Śākyamuni relating to his disciples from the distant past continuously until the future. However, this idea was laid out in full here.

If so, the sentient beings = bodhisattvas that relate with Buddha must also undergo a transformation. In Part I, it was brought to light that all sentient beings are bodhisattvas that relate with others. The disciples of Buddha were spurred to such a self-awareness. This is bodhisattva as existence. In Part II, due to the relationship with the dead, mere self-awareness is no longer sufficient – bodhisattvas are spurred to praxis. These are the bodhisattvas that arose in “Chapter XV. Bodhisattvas Emerging from the Earth.” These are not necessarily different bodhisattvas from those in Part I, but instead are all sentient beings awakened to self-awareness as bodhisattvas. But by relating with Buddha, who had attained the power of the dead, these bodhisattvas rise to a higher level and a new practice. Conversely, true praxis cannot arise in relations confined to the living. It is because of the relationship with the departed that the self-awareness of bodhisattvas can no longer remain mere self-awareness and necessarily overflows into praxis. This is what Tanabe Hajime 田辺 元 referred to as the existential communion with the dead (shisa to no jitsuzon kyōdō 死者との実存協同). It is a bodhisattva that includes not merely going to the Pure Land (ōsō 往相) but returning from the Pure Land (gensō 還相).

D. The Concrete Praxis of Bodhisattva Ethics

As we have seen above, bodhisattva ethics has the following two characteristics:

First, human beings – more broadly, sentient beings – themselves exist by continuously relating with others. Relation precedes existence. The recognition of this is “bodhisattva as existence.” The relationship with the other is turned toward a more positive relation, and because of this, one actively participates for the benefit of others – “bodhisattva as praxis.”

Second, this is not merely within this world, this life, but goes beyond to previous and subsequent lives.

Bodhisattva ethics presupposes the development of faith in the Buddha in the Jātaka Tales, which progressed in early Mahāyāna Buddhism, and whose theory became established in the Lotus Sutra. In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the activities of various bodhisattvas clarify the praxis of this bodhisattva ethics. A representative of this is Bodhisattva Kannon 観音 (Kanzeon 観世音), who takes various forms in an effort to save sentient beings. This way of being of bodhisattvas is referred to as the body that transcends saṃsāra (hen'yaku shin 変易身), which is distinguished from the body within saṃsāra (bundan shin 分段身). The latter transmigrates through the six worlds according to karma, but the former is unbound by those restrictions and can freely be taken in order to save sentient beings. Buddhas are said to be the completed form of such bodhisattvas. Now while all sentient beings are said to be bodhisattvas, by no means are we all at such a high level. In reality, [most of us] suffer within our saṃsāra body.

Perhaps some might criticize theories like this for being too utopian. It may resemble the debates on angels in medieval philosophy and theology in the west. In those times, they may have seemed to be very realistic arguments, but can they really hold in the contemporary period? Can these really be applied as an actual ethics today? But today, as modern thinking crumbles, nobody can simply laugh off medieval arguments. Actually, in the medieval age, these debates were not mere fancy, but were set up as a real aim and were realized in action. Do we not have something to learn from this?

As an example of this, let us examine Senkan's 千観 (918–983) Record of Taking the Ten Vows (Jūgan hosshin ki 十願発心記, 962). Senkan was a scholar monk from the middle of the Heian period. He lived prior to Genshin 源信 (who wrote the Essentials of Rebirth in the Pure Land, Ōjōyōshū 往生要集), and was also known as a believer in the Pure Land. In Senkan's Record, one learns from all buddhas and bodhisattvas, taking ten vows and practicing oneself. The vows are, first, to be born in Amida Buddha's Pure Land, and then to devote oneself to various activities to save sentient beings. For example, “In the sixth vow, I vow to spend much time in the worlds in the ten directions that are undergoing the kalpa of three disasters, take the form of a wealthy man and save the starving from suffering, manifest the body of a great medicine king and heal people from epidemics, to use the power of the fundamental charity and take away the ill will of soldiers…. In this original vow, one tries to be like Bhaiṣajyaguru.” Trying to be like Bhaiṣajyaguru (the Buddha of medicine and healing) may seem delusional, but it makes sense if you consider the origin of bodhisattvas.

One of the chants shared by many (but not all) Buddhist sects is the “Four Great Bodhisattva Vows” (Shi gu sei gan 四弘誓願). The original prototype of this came from Zhìyǐ 智顗 (Chigi, 538–597, [founder] of the Tiantai school), and various schools differ in the exact wording. In the Zen school, they say “However innumerable the sentient beings, I vow to save them all. However inexhaustible the worldly passions, I vow to extinguish them all. However immeasurable the dharma-gates, I vow to master them all. However incomparable the way of the Buddha, I vow to attain it.”Footnote 22 Saving all sentient beings, cutting off inexhaustible attachments, mastering the countless dharma-gates, attaining the highest Buddha way – realizing this seems impossible. However, one takes the arrant vow to fulfill this, and this tradition continues in the various schools of Japanese Buddhism. We need to rethink the meaning of this.

Miyazawa Kenji's 宮澤 賢治 poem “Be Not Defeated by the Rain” should be considered in this vein. It is not about trying to do something that a moral education textbook would teach. When Kenji wrote this poem, he was dying from a mortal illness. In the midst of this, Kenji wrote this poem as a vow of a bodhisattva going beyond life and death. After writing this poem in a notebook, he wrote “Myōhō renge kyō 妙法蓮華経” (the name of the Lotus Sutra) in the middle, Śākyamuni Buddha and Prabhūtaratna Buddha on each side, and the four teachers of the bodhisattvas who emerged from the Earth around the circumference. This is none other than the Nichiren mandala. As we see, the spirit of the bodhisattva has been ceaselessly maintained even up to the contemporary period.

Let us examine another example. An Account of My Hut (Hōjōki 方丈記) carefully records the details of the great famine during the Yōwa Era (1181–1182), and the activities of Ryūgyō Hōin 隆暁法印 from Ninnaji 仁和寺.

A monk by the name of Ryūgyō Hōin from Ninnaji, sorrowing to see people dying in such countless numbers, took to inscribing the sacred Sanskrit syllable “A” on the forehead of any he met with, to lead them to rebirth in paradise. When a count was made of all the dead, the total for the fourth and fifth months came to over 42,300 in the area from Ichijō south and from Kujō north, from East Kyōgoku west and Shujaku east.Footnote 23

Ryūgyō (1135–1206) was the child of Minamoto no Toshitaka 源俊隆 of Murakami Genji 村上源氏, and was the older brother of the poet Kōkamon'in no Bettō 皇嘉門院別当. He was of the Gon no Daisōzu 権大僧都 class, residing in Shōhō-in 勝宝院 in Ninnaji. A Buddhist priest of aristocratic birth and of the Hōin rank (the highest rank) was running about doing memorial services for countless dead commoners. The “A” syllable is the first character in Sanskrit, and means the origin of all things. By writing that on the forehead of the dead, one binds them to the Buddha's providence in the afterlife, allowing them to proceed toward enlightenment. This is precisely what Tanabe Hajime called the existential communion with the dead. After the Great Tōhoku Earthquake of 2011, how to relate with the dead was a big issue. We had to face the problem of how to deal with an enormous number of corpses. This is the same problem Ryūgyō faced. Here, a medieval problem links directly to the present.

In the fourth year of Jishō (1180), around the same time as Ryūgyō's activities, Taira no Shigehira's 平重衡 siege of Nara reduced the temples of the southern capital to ashes. But in the next year, Chōgen 重源 (1121–1206) was chosen as the official to solicit contributions for Tōdaiji. Chōgen made use of his wide network, soliciting funds regardless of the social standing of the contributors, and was able to put together the funds to rebuild. In the background of this solicitation was the idea of sazen 作善 (lit. making goodness), wherein even a small donation would, as good karma, lead to Buddha's providence. This too is part of bodhisattva work. In this way, the Buddhism of the Kamakura period was formed on bodhisattva thought. Going back to its origins, Saichō's 最澄 (767–822) adoption of Mahāyāna (Bodhisattva) Precepts was also based on the ideal of the bodhisattva, which is rooted in benefitting others. This is arguably a considerable tradition in Japanese Buddhism.

One person who re-theorized what it means to be a bodhisattva is Shinran 親鸞. The base of Shinran's philosophy is the double transfer of merit (nishu ekō 二種廻向) of going to and returning from the Pure Land (ōsō 往相 and gensō 還相). This is a two-way process of first dwelling in the Pure Land – the ideal world of Buddha – and from there returning to lead all sentient beings into enlightenment (shujō saido 衆生済度). Shinran did not think we could do this two-way movement by our own power, clarifying other power (tariki 他力) where one relies on the power of Buddha. It is the power of gensō of Buddha that is working on us. To take this further, one might say that it is the gensō of the countless dead of the past that is at work.

Another important part of Shinran's bodhisattva philosophy is his assertion of “genshō shōjōju 現生正定聚” (lit. “rightly-established group in this life,” or more colloquially translated as “saved by the Great Vow”). Shōjōju is the stage of bodhisattvas where they are certain to become Buddhas. Shinran saw this level as at par with Bodhisattva Maitreya, who waits in the Tuṣita realm to become the future Buddha of this world – the highest level of bodhisattvas. In East Asian Buddhism, there are usually fifty-two ranks for bodhisattvas. Ten stages of faith (jisshin 十信), ten stages of security (jūjū 十住), ten stages of practice (jūgyō 十行), ten stages of devotion (jūekō 十廻向), ten stages of development (jūji 十地), near perfect-enlightenment (tōgaku 等覚), and perfect enlightenment (myōgaku 妙覚). Maitreya is in the second to the last rank. In the theory of Tendai and Kegon, attaining Buddhahood in this body (sokushin jōbutsu) is realized when one enters the first stage of security (after completing the tenth stage of faith). If so, then Shinran's shōjōju comes after realizing sokushin jōbutsu and is a more advanced state.

However, even if it is said that the greatest other power is at work, or that one rises to a level at par with Maitreya, how are things in reality? In actuality, we cannot be enough help toward others. We are powerless, distant from the ideal of benefitting others. Even if one supposes that one is presently a bodhisattva, one is a puny bodhisattva. What are we to do with this dilemma? Here, once again, death is put into close relief. Is death not a freedom from that powerlessness, heading toward the authentic working of bodhisattvas? Is this not what Shinran meant by “ōsō” (going toward the Pure Land)? Here, we need to reconsider the multiple layers of the incomplete bodhisattvas of this life (this world) and the complete bodhisattvas (or buddhas) after death. In this way, the problem of bodhisattvas returns us to the problems of this world and the next, of life and death. The praxis of bodhisattvas unfolds, transcending the discontinuous continuity of the dilemma of life and death.

Above, we have quickly scanned the outlines of the practice and theory of bodhisattva ethics, concretely expressed in Japanese Buddhism. What we have seen is that this is not a fanciful abstraction, but that it functions as a strong theory rooted in actuality. This is not something that belongs in the closed-off past of the medieval period. The medieval circumstance can be surprisingly similar to the contemporary. Bodhisattva ethics is by no means complete – it harbors various contradictions and unsolved problems. However, I think that it is necessary to reconsider the broad lens of bodhisattva ethics in the midst of [the current] period of crisis.