1 Introduction

In Indo-European languages, aspectual oppositions are quite common in the past tense and are generally restricted to tensed forms, as emerges from the discussion in Comrie (Reference Comrie1976: 39–40, 55), which considers aspect in non-finite verb forms only in passing. Slavic languages differ from Standard Average European languages in that their aspectual opposition (the perfective : imperfective opposition) is not marked by inflectional endings, but derivationally, by prefixes and suffixes (e.g. po-stroitˈ ‘build.pfv’ formed by prefixation from simplex stroitˈ ‘build.ipfv’, and za-kaz-yvatˈ ‘order.ipfv’ formed by suffixation from za-kazatˈ ‘order.pfv’). Thus, Slavic aspectual systems are built on aspectually correlated lexical verbs, each with its own paradigm, which means that the perfective : imperfective opposition is encoded not only in finite but also in non-finite verb forms, including the infinitive, subjunctive and imperative, as well as some participles and verbal adverbs, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Russian verbal categories and aspect for ‘read’.

The organization of the Russian verb shown in Table 1 resembles the aspectual organization of verbs in Ancient Greek or Vedic, in which present and aorist stems not only had preterit forms, but also non-finite forms (e.g. imperatives and subjunctives).

Even in Slavic linguistics, studies of aspect have tended to focus on tensed verb forms, and past-tense verb forms in particular. (A notable exception is Forsyth Reference Forsyth1970, who devotes considerable attention to aspectual usage in Russian imperatives and infinitives.) And it is not surprising that Slavists have likewise generally focused on the past tense in studies of aspect, because written narratives provide clear contexts in which the differences between the perfective and imperfective verbs are most accessible and seem to be the most rigid and least dependent on tacit assumptions made by discourse participants. Aspectual usage in non-narrative contexts, i.e. conversational discourse, can be very difficult to motivate without detailed knowledge of the discourse factors in play, e.g. what the speaker assumes about the fact structure of the discourse and the relationship of other participants to it (an excellent study demonstrating these effects is Israeli Reference Israeli2001, which analyzes aspectual usage in past-tense verbs of communication in Russian conversational discourse).

This imbalance raises the question of how the recognized functions of the Russian perfective : imperfective opposition in non-finite verb forms – in particular, the imperative – can be incorporated into the analyses that have focused on tensed usage in general, and past-tense usage in narratives in particular. I think it is safe to say that most Slavic linguists would say that they can; moreover, most would say that the meaning commonly assumed for the perfective, i.e. totality (or some other synoptic category, see e.g. Zaliznjak & Šmelev Reference Zaliznjak and Šmelev2000, who argue that the meaning of the Russian perfective is an event, i.e. a situation including a change of state), can account for the observed uses of the perfective in imperatives, and conversely, that the meaning commonly assumed for the imperfective, i.e. non-totality (processuality), can generally account for the observed uses of imperfective imperatives, albeit by semantic extension. This default position makes sense, particularly if one keeps in mind that the diversity of aspectual marking in Russian (an array of prefixes and suffixes and their combinations) alongside the relatively fixed rules of usage practically forces an analysis of Russian aspect to rely on some sort of invariant or prototypical meaning expressed by perfective verbs on the one hand, and imperfective verbs on the other. However, the synoptic theory of Russian aspect outlined above is not the only possibility, and Section 1.2 presents an alternative approach, which is grounded in cognitive linguistics.

1.1 The cognitive linguistic approach

The approach to language taken in this analysis is that of cognitive linguistics, in particular Cognitive Grammar (CG; see e.g. Taylor Reference Taylor2003 Langacker Reference Langacker2008) and Construction Grammar (CxG; see e.g. Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006), which share many assumptions. The following assumptions about meaning made by CG and CxG are particularly relevant for the analysis presented here. First, the meanings of linguistic units, whether lexical units (words and morphemes) or grammatical units (tense and aspect markers, etc.), are categories. These semantic categories can (and usually do) have internal structure, such as a central prototypical meaning with related peripheral meanings (a radial category) or a family-resemblance structure, in which the individual members share some but not all of a set of features with each other.

An important principle of cognitive linguistics is the lack of a clear distinction between lexicon and grammar (Langacker Reference Langacker2008: 18). Similarly, as a usage-based approach, cognitive linguistics makes no sharp distinction between semantic and pragmatic knowledge (see Langacker Reference Langacker2008: 40), and both types of knowledge can comprise the meanings of linguistic units. In other words, the meanings of linguistic units reflect encyclopedic knowledge. The lack of clear distinctions between traditional ‘levels’ of language is particularly important for accounts of the functions of Russian aspect, which is a category organized around verbs as lexical units as opposed to being expressed by inflectional endings in a part of a verbal paradigm; the lexical verbs comprising the aspectual opposition have discourse functions that are more characteristic of purely grammatical morphemes. CxG can make sense of this phenomenon, inasmuch as it considers complex words such as the aspectually correlated prefixed and suffixed verbs of Russian to be constructions on a par with syntactic constructions (see Goldberg Reference Goldberg2006, Booij Reference Booij, Hoffmann and Trousdale2013).

The basic semantic categories employed in this analysis, temporal definiteness and temporal indefiniteness, are schemas, i.e. schematic representations of content that is extracted from all uses of a form (see Langacker Reference Langacker2008: 17). Schemas are necessarily abstract, forming the most abstract level of complex semantic networks that consist of various more particular instantiations, which may have the status of a central or local prototypes. By way of example, Langacker (Reference Langacker2008: 17) points out that in the case of the English word ring a maximally abstract schema of ‘circular object’ which is instantiated by (and immanent in) the word’s prototypical sense of ‘circular piece of jewelry worn on the finger’.

To illustrate this situation with material from this analysis, the basic schema of the temporal definiteness of the Russian perfective (Figure 1 below) is instantiated by a more particular schema representing what is expressed by a perfective imperative (Figure 4 in Section 2 below). To return to the lack of a distinction between lexicon and grammar in cognitive linguistics, the semantic meanings both of lexical and grammatical units can be described in terms of semantic networks consisting of a schema and its instantiations. Thus, in the analysis advocated here, the meanings both of the perfective and the imperfective aspect are to be described as networks, consisting of a schema and its more particular (including prototypical) instantiations. Given the nature of this analysis, these networks are not described in full; only the elements of the network relevant for imperative usage are described here.

1.2 The meanings of the perfective and imperfective aspects in Russian

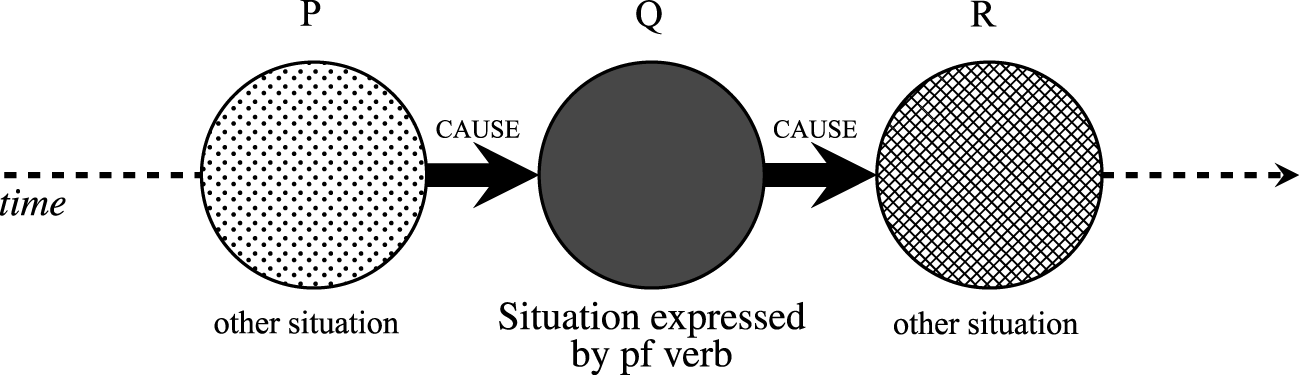

This study takes as its point of departure the analysis of the Russian perfective : imperfective opposition laid out in Dickey (Reference Dickey2000, Reference Dickey, Schrager, Fowler, Franks and Andrews2015) and updated in Dickey (Reference Dickey2018). According to this analysis, the Russian perfective does not simply express totality or change of state, as has been traditionally assumed (see e.g. Bondarko Reference Bondarko1996 and Zaliznjak & Šmelev Reference Zaliznjak and Šmelev2000); instead, it expresses a category termed temporal definiteness (adopted from Leinonen Reference Leinonen1982), which is diagrammed in Figure 1. A situation is temporally definite if it is unique in the temporal fact structure of a discourse, i.e. if it is construed as (a) some kind of complete whole that is (b) qualitatively different from preceding and subsequent states of affairs (the uniqueness condition); the Russian perfective asserts that a situation is temporally definite.

Figure 1 Basic schema of temporal definiteness.

There is no space in this article to present arguments in favor of the idea that the Russian perfective asserts sequential (and causal) links with other states of affairs. (The interested reader is referred to Dickey Reference Dickey2018, Section 4 and the references cited there for a recent treatment.)

The meaning of the imperfective in Russian is simply the cancellation of temporal definiteness, shown in Figure 2, which I term (qualitative) temporal indefiniteness. That is to say, the situation is construed as being outside of any sequence with other qualitatively different states of affairs. There are three major instantiations of temporal indefiniteness, each of which should be considered a local prototype of the schema of temporal indefiniteness: (i) a situation construed as a process ongoing at some reference time or over some period of time, (ii) habitual (unbounded) repetition, and (iii) various kinds of statements of fact, in which a situation, often a completed action, is mentioned either in isolation from its temporal context or purposefully defocusing it. Note that a process which is ongoing at a reference point is nevertheless temporally indefinite, as its full temporal extent is indeterminate (i.e. it began at some undetermined point in time before the reference point and unless interrupted continues for some undetermined length of time thereafter; see Šatunovskij Reference Šatunovskij2009: 26).

Figure 2 Basic schema of temporal indefiniteness.

If the Russian perfective asserts temporal sequencing as its core meaning, its semantic nature differs considerably from that of perfective categories in many other languages, such as the English simple tenses or even the perfective aspect in Czech, another Slavic language. These latter grammemes do occur in contexts of sequentiality; however, they are not limited to such contexts and express merely totality or completion, without asserting the temporal uniqueness of a situation. While the Russian (and East Slavic) perfective aspect appears to be quite unusual among perfective categories in this regard, it is important to point out that its meaning encapsulates a basic conceptualization of time.

While this view was already advanced by Galton (Reference Galton1976) on the basis of Slavic data, it becomes more theoretically grounded in light of Moore (Reference Moore2006, Reference Moore2014) and Evans (Reference Evans2013), who argue for the existence of a sequential conceptualization of time as a cognitive conceptualization of time distinct from the traditionally recognized deictic conceptualizations of moving-ego time and (ego-centered) moving time. Whereas the deictic conceptualizations have an ego-based frame of reference, the sequential conceptualization has a field-based frame of reference (see Moore Reference Moore2006: 204–206). That is to say, the substrate itself, actions, as opposed to the ego, provide the frame of reference. The sequential conceptualization thus simply construes events as in succession irrespective of the conceptualizer’s deictic viewpoint, as in Moore’s example The sound of an explosion followed the flash, and is diagrammed in Figure 3.

Figure 3 The sequential conceptualization of time.

In Figure 3, the flash is situation A, and the sound of the explosion is situation B, which is in a sequential relationship with the flash. The sound of the explosion is the figure, whereas the flash is the ground, with respect to which the sound of the explosion is located in time. Note that this conceptualization is not restricted temporally; as Moore (Reference Moore2006: 207) points out it occurs both in the past (A reception followed the conference), the future (A reception will follow the conference), and the (habitual) present (A reception always follows the conference).

The approach to Russian aspect outlined above is of importance to an account of Russian aspectual usage outside narrative contexts or even tensed usage in general. If the Russian perfective : imperfective opposition reflects a cognitive conceptualization of time (the sequential model) and the meanings of temporal definiteness and temporal indefiniteness are inherent in perfective and imperfective verbs (respectively) as lexical units, then the cognitive conceptualization of time expressed by the perfective will be operative in nearly any use of any Russian verb, whether in narrative or conversational discourse and in finite or non-finite forms. That is to say, Russian aspect introduces the sequential conceptualization of time into any usage of any verb (whether signaling that conceptualization of time via the perfective or canceling it via the imperfective).

1.3 Previous approaches to aspectual usage in Russian imperatives

Though aspectual usage in imperatives in Russian has not been studied as thoroughly as tensed usage, a detailed review of previous treatments lies beyond the scope of this paper. Here I simply outline some analytical approaches to the problem in recent decades and note some challenges. Relatively recent treatments can be divided into two kinds: (i) attempts to explain aspectual usage in imperatives directly as cases of the semantic categories of aspectual usage established for tensed usage, focusing on temporal metrics and issues of reference, and (ii) those actively incorporating the concepts and approaches of linguistic pragmatics into more discourse-oriented explanations of aspectual usage in imperatives.

To begin, it should be noted that all accounts observe that imperatives requesting the listener to carry out a single action to completion tend to be coded perfective, as in example (1) below, and that imperatives requesting the listener to begin or continue an open-ended activity or to carry out an action repeatedly are coded imperfective, as in the examples in (2). These basic facts are not in dispute.

These cases are not discussed further here (but see Sections 2 and 3 for an explanation in terms of the analysis proposed in this paper).

The first approach has been dominated by structuralist treatments, e.g. Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1970: 194–219) and Xrakovskij (Reference Xrakovskij1988). While these recognize that imperatives occur in various kinds of speech acts in Russian and that the social (power) relationship between the speaker and listener can affect coding, such points are considered only intuitively, without recourse to work in the field of pragmatics. Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1970) and Xrakovskij (Reference Xrakovskij1988) also assume a privative markedness relationship between the perfective and the imperfective, i.e. that the perfective refers to a single, total event, whereas the imperfective makes no statement in this regard (albeit with a chief meaning of processuality). The markedness approach leads these studies to the view that in affirmative imperatives referring to single completed actions there is little semantic difference between the perfective and imperfective aspect (see Xrakovskij (Reference Xrakovskij1988: 281), who suggests that imperfective imperatives referring to single completable actions can be replaced by perfective imperatives without a ‘marked’ difference in meaning), despite contextually-conditioned tendencies in aspectual usage (which are relegated to the domain of pragmatics, and are thus are not considered to be elements of the semantic aspectual meaning of the forms).

Regarding the referential properties of perfective imperatives, both Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1970: 199–200) and Xrakovskij (Reference Xrakovskij1988: 283) suggest that imperatives are coded perfective when the predicate is new information, i.e. when the listener has not previously considered carrying out the action under request. Conversely, if the listener is already aware of the necessity of the action, the imperfective is employed to request that the listener initiate the action, which is considered to be an instantiation of the processual meaning of the imperfective. Consider example (3), taken from Xrakovskij (Reference Xrakovskij1988: 283).

In (3), the mother’s idea to turn on the television is new for the listener; according to this view, if the listener were already aware that the mother wanted the television turned on, the imperative would be coded imperfective.

While it is true that perfective imperatives are often new information in the discourse, they do occur when the listener has already considered the action, as in (4).

Here the first interlocutor wants to turn off the light to avoid unwanted attention; the second interlocutor initially dismisses her concern, but then changes his mind and tells her to turn it off.

Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1970: 199) also suggests that perfective imperatives are employed in cases of sequences of events (see also Fortuin & Pflaumgraff Reference Fortuin, Pflaumgraff and Benacchio2015: 224), as in (5), taken from Forsyth (Reference Forsyth1970: 199).

This is another case of a tendency that is far from absolute. The examples in (6) are representative.

In (6a), the imperatives for two actions in sequence are coded imperfective. In (6b), the first is coded imperfective and the second is coded perfective. The usage exemplified in (6) is common, and indicates that the function of event sequencing, which is dominant in finite and some non-finite usage, is weaker in imperatives.

A very recent iteration of the first approach is Alvestad (Reference Alvestad, Zybatow, Biskup, Guhl, Hurtig, Mueller-Reichau and Yastrebova2015), which focuses on imperfective imperatives that follow perfective imperatives, as in (7), and presents a DRT account of their semantics.

On the basis of such constructions, Alvestad assumes that imperfective imperatives occurring after lexically identical perfective imperatives represent event anaphora, as they refer to the same event as the preceding perfective imperative. Note that her inserted ellipsis omits content that provides context that motivates the discourse function of the second imperfective imperative, which is one of forceful insistence. Further, she argues that, as such imperfective imperatives refer to single completed events, they are aspectually ‘fake’, i.e. their aspectual value is perfective.

This line of reasoning, which I consider bizarre, can be perhaps be seen as a development of the structuralist markedness analysis mentioned above, according to which in the context of single completable actions an imperfective imperative is, as it were, semantically indistinguishable from the corresponding perfective imperative: if completion is the sole criterion for the use of the perfective aspect in contrast to the imperfective, then imperfective verbs referring to completed events have perfective value and are ‘fake’. Apart from the complete neglect of the discourse contexts triggering such imperfective usage, Alvestad’s argument about an event-anaphoric function of the imperfective aspect is largely based on a single example from a work by Chekhov incompletely cited by Grønn (Reference Grønn2003: 192), which he claims to be confirmation that the imperfective has an anaphoric function in tensed usage. I have argued against this analysis of this example and presented other contradictory data in Dickey (Reference Dickey2018: 89–91), to which the interested reader is referred.

Moreover, Alvestad’s (Reference Alvestad, Zybatow, Biskup, Guhl, Hurtig, Mueller-Reichau and Yastrebova2015) account is simply descriptively mistaken, as imperfective imperatives commonly occur to refer to single completable actions without a preceding lexically identical perfective, as in (6a) above. In addition, perfective verbs can occur when the action has already been mentioned, as in (4) above, and when commands are repeated, as, for instance, in example (8), taken from Zorixina-Nilˈsson (Reference Zorixina-Nilˈsson and Voejkova2012: 192).

In (8) the judge tells Kartinkin to sit down three times, once with an imperfective imperative and then twice with perfective imperatives. Such data is very difficult to reconcile with the idea that signaling event anaphora is a specific function of imperfective imperatives. Such data must be accounted for in any analysis arguing that imperfective imperatives function as event anaphora, if it is to be taken seriously.

The aforementioned difficulties in explaining aspectual usage in imperatives with the traditionally posited temporal and referential qualities of the perfective and imperfective aspects have led to more pragmatically oriented analyses, which incorporate the findings from pragmatics (especially concerning politeness, e.g. Brown & Levinson Reference Brown and Levinson1987). Benacchio (Reference Benacchio2010) is a seminal work in this direction. Beyond the basic aspectual functions of perfective and imperfective imperatives outlined at the beginning of this section, Benacchio analyzes perfective imperatives as expressing negative politeness, as they are generally more formal and distant than imperfective imperatives, in a metaphorical extension of the distal perspective of the perfective on the action and its result. In contrast, imperfective imperatives, as they focus on the phases of an action, tend to occur in less formal contexts, in a metaphorical extension of the close-up view of an action. Further, she analyzes imperfective imperatives as expressing positive politeness if they request actions that are in the interest of the listener, whereas they are gruff/rude if they request an action not in the listener’s interest.

Benacchio (Reference Benacchio2010) is also a comparative cross-Slavic study, and provides an analysis that accounts for a great deal of data for Russian and other Slavic languages. Nevertheless, there are cases when it is difficult to see a clear alignment between the politeness effects of imperfective imperatives and the benefit or lack thereof for the listener. A case in point is that of military orders in the imperfective, which are difficult to analyze in terms of politeness; inasmuch as they can be gruff or harsh, as in (9), they also present difficulties for an analysis in terms of the benefit for the listener.

The context of (9), which is taken from the movie Doroga na Berlin (‘The Road to Berlin’) is a German attack, during which a Russian antitank gun commander shouts at his crew to turn their gun around to fire on German tanks that are unexpectedly drawing near. Politeness is simply not relevant, and regarding the benefit to the listeners, one can only assume that it is to their benefit to get the gun turned around, as this is their only chance of surviving the attack.

Another recent study focusing on the politeness of aspectual usage in Russian imperatives is Zorixina-Nilˈsson (Reference Zorixina-Nilˈsson and Voejkova2012). Zorixina-Nilˈsson rejects the apparent synonymy of the perfective and imperfective in imperatives referring to single completable actions, and examines imperatives in requests, commands, advice and granting permission from the perspective of politeness, in terms of the speaker’s intention and whose interests are served by the action. She explains various cases of impoliteness (usually in imperfective usage, but some in perfective usage) as instances in which the speaker expresses intentions that are appropriate according to the logic of a situation. Thus, if the listener has not previously considered an action and a perfective imperative is therefore appropriate, an impoliteness effect arises if the speaker uses an imperfective imperative, which would signal that the action is something that the listener should be ready to perform in the situation. Conversely, if the listener has already considered the action and the imperfective is appropriate, then use of the perfective can be impolite.

One area of usage in which Zorixina-Nilˈsson’s description seems debatable is that of orders. According to Zorixina-Nilˈsson (Reference Zorixina-Nilˈsson and Voejkova2012: 197), the perfective is the default aspect of orders because the content of most orders is new to the listener. While this characterization of their information structure is true, orders are often in the imperfective, even when the content is new for the listener, and regardless of whether the order is urgent (as in (9) above), or not. Indeed, an examination of the first half of a well-known Russian war novel (V okopax Stalingrada ‘In the Trenches of Stalingrad’ by Viktor Nekrasov) my count of orders expressed by imperative forms referring to completable actions yielded roughly even numbers for each aspect: 14 perfective orders and 16 imperfective orders.Footnote [3] Orders are a complex phenomenon and are discussed in Sections 2 and 3.2 below.

Both Benacchio (Reference Benacchio2010) and Zorixina-Nilˈsson (Reference Zorixina-Nilˈsson and Voejkova2012) provide valuable descriptive and explanatory insights, which are discussed in the following sections where relevant. However, the analysis proposed here takes a different approach, adopting the overall semantic approach to Russian aspect outlined in Section 1.2 above and arguing that the usage of perfective and imperfective verbs in the imperative follows fairly straightforwardly from the prototypical meanings of the aspects, temporal definiteness and temporal indefiniteness. In particular, the analysis advocated here builds on Šatunovskij’s (Reference Šatunovskij2009, chapter 10) analysis of Russian aspectual usage in the imperative, which is not described here, but in Sections 2 and 3; Šatunovskij’s analysis is recast in terms of the approach to aspect taken here. Further, I argue that the analysis finds support in Leech’s (Reference Leech2014) pragmalinguistic approach to politeness in directives, according to which politeness in directives is correlated with the degree of optionality offered to the listener, with requests in principle offering the listener the opportunity to choose whether to comply, whereas more forceful directives do not. In a nutshell, aspectual usage in imperatives is determined primarily by the decision to perform the requested action: who makes the decision, and when the decision is made relative to speech time.

Before proceeding, I should point out that in what follows I adopt the term mand as a cover term for the semantic category expressed by imperative forms in Russian from Leech (Reference Leech2014). Leech’s term, which refers to speech acts directed from the speaker to the listener expressing the desirability of a situation (in particular, that the listener perform the action) is particularly suitable for Russian, because imperatives occur in Russian with high frequency (much higher than in English, for instance) and express a range of speech acts, including orders, requests, suggestions and invitations, etc.Footnote [4]

2 Perfective imperatives in Russian

In this paper I adopt Šatunovskij’s (Reference Šatunovskij2009) approach to the Russian perfective imperative, basically without alteration, though I formulate it in terms of temporal definiteness as the prototypical meaning of the Russian perfective. According to Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 254–255), a perfective imperative in Russian communicates a request for the addressee to first make the choice to perform an action and then perform it with the intended outcome/result. That is to say, Russian perfective imperatives include an opportunity for the listener choose to comply with the mand, and then to do so.Footnote [5] Other accounts have made observations that comport with Šatunovskij’s idea. For instance, Voejkova (Reference Voejkova2015: 39) suggests that perfective imperatives ‘allow the listener some time to consider the command’, i.e. perfective imperatives do not request the instantaneous performance of the action (in contrast to many imperfective imperatives). Whether the time intervening between the speech time and the anticipated time of the requested event involves the choice on the part of the listener at the most abstract level of schematization is not important; in a usage-based account, a moment given to the listener to choose to carry out the action will be part of an operative schema (see Figure 4). Note also that if one considers Leech’s (Reference Leech2014: 135) view that ‘a request is normally considered a speech act that gives H [the listener] as choice as to whether to perform the desired act or not’, then a Russian perfective imperative is a paradigm case of a request.Footnote [6]

Let us take (1), repeated here as (10), which is a simple example of a perfective imperative, to illustrate the mechanism at work.

This example is taken from a forum in which the previous post by Ivan discussed an idea for a bicycle game and his thoughts on bicycling. Now the speaker asks Ivan to recommend a bicycle, something that has not been a topic in the discussion, and so naturally the speaker’s request involves a covert request for Ivan to choose to make the recommendation. That is to say, the perfective imperative in (10) gives Ivan the chance to decide to comply with the mand. This is presumably why the perfective imperative, as a direct or on-record request, can nevertheless be quite polite in Russian.

Such perfective imperatives instantiate the schema for temporal definiteness in the following manner. The imperative form itself refers to situation Q; the preceding situation O is the ground (the speech situation), in which the speaker recognizes Ivan’s expertise in bicycles; the subsequent situation R is the post-event outcome where Ivan has made the recommendation and the speaker has gained knowledge that will allow him to attain some goal. The time allowed for the choice by the listener to carry out the action P is conceptually a distinct component relevant for aspectual usage in imperatives and thus comprises one element of a sequential chain that instantiates the temporal definiteness template given in Figure 1. The structure just described is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 The Russian perfective imperative as an instantiation of temporal definiteness.

Regarding the perfective imperative as an instantiation of temporal definiteness, it is important to point out that this term should only be understood as set out in Section 1.2. Temporally definite predicates are not necessarily definite in the sense of definiteness as ordinarily applied to noun phrases (i.e. referring to entities that are unique in the shared knowledge of both speaker and listener). In the case of perfective imperatives, the sequencing of temporal definiteness means only that the verb form refers to a unique, i.e. specific requested action, and does not signal that both speaker and listener share knowledge about it. Thus, the perfective imperative signals that the listener is given a moment in time to choose to perform the action; the chain of events beginning with the speech time, followed by the moment in time allowed for the listener to decide to comply with the request, which is in turn followed by the action itself and its subsequent anticipated result is what comprises the sequentiality schematized in Figure 1 above.

Unlike tensed usage, in which taxis relationships are very strict and the usage of perfective and imperfective verbs depends on the temporal relations between predicates, in imperative usage, the temporal relationships between predicates are of secondary importance to the temporal relations existing between the requested action and the choice to perform the action in the dynamic between speaker and listener. To be sure, one can find chains of perfective imperatives expressing mands for actions to be carried out in sequence, as in (11).

However, each perfective imperative can be analyzed as instantiating the schema in Figure 4, inasmuch as each is a newly requested action concerning which the listener is given the opportunity to comply with the request. Morever, as pointed out in Section 1.3, perfective coding of mands for sequenced events is not obligatory. Particularly where single completable actions are concerned, aspectual usage is primarily dependent on the dynamic between the speaker and the listener and is determined individually for each verb. This makes sense, as this dynamic is of paramount importance for imperatives in general, and conversely, sequencing actions is relatively unimportant.Footnote [7] Consider (6a, b) above and (12).

In (12) there is a string of perfective imperatives, which refer to actions that are all to occur simultaneously (this is not impossible in tensed usage, but is not particularly common); each is perfective because the speaker is asking the listener to make the choice to perform the action. These are followed by an imperfective imperative. According to the principle of sequential relationships, the last imperative should be perfective as well, but it is imperfective, for reasons that are given in Section 3.2 (to anticipate – because the speaker infers that the listener has already made the choice to come to the writer’s workshop).

As Mehlig (Reference Mehlig and Scholz1977: 218) observes, in Russian the perfective is the default aspect for imperatives referring to single, temporally localized situations. In the analysis presented here, the general restriction in Russian of perfective imperatives to refer to unique, temporally localized events is not a consequence of a meaning of totality/completion; rather, it is a consequence of the temporal uniqueness inherent in the temporal definiteness of the Russian perfective. This can be seen in comparative data with other Slavic languages, in which the perfective expresses totality and not temporal definiteness. As shown in (13), Czech and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian allow and even prefer the perfective imperative in cases of habitual repetition.

In Russian, in such contexts, the perfective imperative napiši is unacceptable, and the imperfective piši must be used, because the perfective asserts temporal uniqueness, whereas the imperfective cancels temporal uniqueness. This difference is part of a larger east–west difference in the aspect of imperatives in cases of habitual repetition, first discussed by Benacchio (Reference Benacchio2010: 87–91).

Further evidence that perfective imperatives refer to more than completion are imperatives formed from perfective po- delimitatives, which merely express that an action occurs for some period of time, as shown in (12) above. The imperatives of po- delimitatives in (12) request that the listener do certain things (work, write, and live) for some indeterminate time, after which he will have some degree of experience more suitable for working in the writer’s workshop, whereupon he can come to it again. It must be stressed that these predicates are not telic – they can always continue a little longer, and the increase in experience mentioned by the speaker is not a direct result of these activities, in contrast to telic perfective predicates such as postroitˈ dom ‘build.pfv a house’ or uničtožitˈ dom ‘destroy.pfv a house’, in which the results of the existence and nonexistence (respectively) of a house are asserted. The sequentiality inherent in the meaning of Russian po- delimitatives is what requires them to be used in this context. Note that Slavic languages such as Czech and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian would code these imperatives as imperfective, because their perfective : imperfective oppositions are based on totality/completion and do not regularly create perfective verbs of atelic activity predicates.

If the instantiation of temporal definiteness by the perfective imperative shown in Figure 4 overlaps to considerable extent with the discourse structure of imperatives as such, this is because ordinary, polite imperatives necessarily communicate a request for the listener to first make the choice to carry out an action, i.e. they express negative politeness to the listener (see again Leech Reference Leech2014: 135). It should therefore come as no surprise that in Russian the perfective is the default aspect of imperative requests to complete a single action. Moreover, as Benacchio (Reference Benacchio2010: 44) observes, perfective imperatives, though they may be uttered impatiently and can be uttered more or less politely with different intonation contours, are never in and of themselves improper. Benacchio (Reference Benacchio2010: 41–42) ascribes the propriety of Russian perfective imperatives to a metaphorical distance ultimately arising from the focus of the perfective on the result of the action. I prefer to view the propriety of perfective imperatives and the aforementioned distance as a consequence of the inclusion of a moment in time for the listener first to make the choice to carry out the action: by requesting that the listener first make the choice to carry out an action, perfective imperatives tacitly communicate a recognition of the listener’s decision-making role, and thus is a face-saving strategy oriented toward the negative face of the listener.

There is empirical and theoretical support for this semantic analysis of Russian perfective imperatives. Empirical evidence can be found in the cooccurrence of perfective imperatives with the tag question ladno? ‘okay?’ and with požalujsta ‘please’, as shown in (14a) and (10), repeated here as (14b), respectively.

As for ladno, Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 275) notes the cooccurrence of perfective imperatives with this tag and observes that its function is to verify that the listener has made the choice covertly requested by the perfective imperative. The cooccurrence of perfective imperatives with požalujsta provides further confirmation of the aforementioned politeness of perfective imperatives as mands.

The inherent politeness of perfective imperatives brings us to the theoretical support for the theory given here. In recent decades studies of politeness have focused on the freedom of choice for the listener. Lakoff’s (Reference Lakoff1973: 298) three rules of politeness include as the second rule ‘Give options’, i.e. ‘Let [the Addressee] make his own decisions’. More specifically about requests, Leech (Reference Leech1983: 108) observes that one reason that indirect illocutions, e.g. Can you answer the phone?, are more polite than direct illocutions, e.g. Answer the phone, is because the former ‘increase the degree of optionality’ for the listener. Leech (Reference Leech1983: 109) also discusses politeness in terms of ‘minimizing impolite beliefs’, which can be applied to perfective imperatives, inasmuch as giving, or presuming to give the listener the opportunity to choose to carry out an action signals that the speaker does not believe that s/he has the right to decide for the listener. Lastly, as mentioned above by Leech (Reference Leech2014: 135), requests, which can be quite polite, are characterized by an opportunity for the listener to choose whether to comply or not.

We may make sense of the consensus that Russian perfective imperatives are never in and of themselves impolite with Šatunovskij’s analysis that the perfective imperative communicates a request for the listener to make the choice to perform the action: the request for the listener to make the choice represents a modicum of optionality and thus the recognized politeness. The main issue left to address is that of perfective imperatives that communicate authoritative mands, i.e. requests or orders by authorities, where the listener has practically little or no choice in the matter. An example is (15), an order given by Pontius Pilate in Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita.

None of Pilate’s subordinates would construe this mand as anything but an order. However, as Leech (Reference Leech2014: 135) points out, ‘[a]lthough linguistically an utterance allows both compliance and refusal, there may be little or no intention of offering a choice in practice. In this sense, many polite requests uttered by powerful speakers are hypocritical’. Accordingly, we may view orders such as (15) as polite requests that function as orders, similar to when a colonel in the US Army says Corporal, would you handle radioing for a helicopter? In this order the colonel uses a polite indirect request instead of the direct Corporal, radio for a helicopter.

Further evidence of the function of perfective imperatives to communicate a covert request for the listener to carry out the action is given in example (16), taken from Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 258).

Šatunovskij points out that in this context, in which the speaker approaches a random passerby, over whom he has no authority, with a request for directions, the listener cannot conceivably have considered carrying out the action, and the perfective is the only possible form, because it first asks the listener to make the decision to carry out the action. It should be pointed out here that the imperfective imperative can in certain contexts be used for a single completed event; in (16), it is the fact that the listener cannot have possibly made the choice to perform the action that is decisive for the unacceptability of the imperfective.

Conversely, if the speaker commands someone to perform an action which they have already chosen to carry out, the perfective is impossible, as in (17), taken from Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 260).

The context for (17) is that the listener has already taken aim, and is waiting for the command to shoot. As Šatunovskij points out, since the choice has already been made to carry out the action, the perfective is infelicitous.

Šatunovskij’s hypothesis that the perfective imperative communicates a covert request for the listener to make the choice to carry out an action can also account for the fact that, as mentioned in Section 1.3, perfective imperatives tend to communicate ‘new information’ in a discourse (see Xrakovskij Reference Xrakovskij1988: 283). If the perfective imperative communicates a covert request for the listener to make the choice to carry out an action, then it will ordinarily be felicitous in situations in which the speaker makes an initial request for the listener to perform an action.

If the perfective imperative contains a covert request for the listener to make the choice to carry out an action and as such is always ‘polite’, the question that arises is how imperfective imperatives are different. In Section 1.2 it was suggested that imperfective verbs are used to avoid communicating the content of perfective verbs. The usage of imperfective imperatives follows this same principle. Section 3 describes the functions of imperfective imperatives.

3 Imperfective imperatives in Russian

This section describes the usage of the imperfective imperative in Russian. The imperfective imperative functions at its core to avoid the content communicated by the perfective imperative. Thus, imperfective imperatives occur in two main cases. The first is when the requested action is not a single, specific action with some desired outcome, i.e. the temporal constituency of the requested situation matches the temporal indefiniteness characteristic of some basic finite uses of imperfective verbs (e.g. open-ended activities, habitual repetition). In the second case, imperfective imperatives occur when the speaker urges the listener to carry out single, specific actions to completion (see (17) above, for instance), but with particular pragmatic effects that contrast with perfective usage. The first case is treated in Section 3.1, and the second in Section 3.2.

3.1 Imperfective imperatives in cases of the temporal indefiniteness of the requested action

The first case of imperfective imperative usage is motivated by the temporal contours of the situation in question, and does not involve particular pragmatic effects. There are two subcases: activity predicates and habitual repetition.

The first subcase is the use of the imperfective for imperatives urging the addressee to continue or resume some activity, i.e. open-ended process. Example (2a), repeated here as (18), is representative.

The situation that the verbs refer to, smoking, is an activity predicate presented as an an open-ended situation, and thus is temporal indefinite (i.e. it is not located in its entirety uniquely in time relative to other states of affairs; see in this regard Šatunovskij Reference Šatunovskij2009: 250, who points out that such imperatives refer to situations extending indefinitely in time). Such processual imperfective imperatives are straightforward, and require no further comment.

The second case of temporal indefiniteness is that of imperatives urging the addressee to carry out an action habitually, as in (2b), repeated here as (19).

Though Russian does allow perfective verbs in certain contexts of habitual repetition, mostly in the present tense, the perfective is negligible in the imperative. Habitual repetition is a paradigm case of temporal indefiniteness, and so the preference for the imperfective imperative is unremarkable. Note again that the restriction to the imperfective in this context is not axiomatic: other Slavic languages such as Czech and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian allow and even prefer the perfective in such contexts, as pointed out in Section 2.

Beyond the expression of ongoing processes and habitual events, imperfective imperatives in Russian can also be employed to refer to single completable events, i.e. to urge the listener to carry out a single event to completion. In such cases, there are specific pragmatic effects that arise. The basic mechanism underlying these cases is discussed in Section 3.2.

3.2 Imperfective imperatives in cases of single completable events

This section treats imperfective imperatives employed by a speaker to urge the listener to carry out a single action to its completion. Such imperfective imperatives can have a range of pragmatic qualities, and a full treatment is beyond the scope of a single article – only the basic types of usage are discussed. For this reason, this section first lays out what the underlying mechanism is assumed to be; pragmatic effects are discussed with individual examples. Examples of such usage were given in examples (6) and (17), repeated here as (20a, b).

Such imperfective imperatives do not refer to protracted processes; in fact, (20a) is an urgent order to complete the action and might be more idiomatically translated as ‘Get the gun turned around!’.

Recall from Section 2 above that a perfective imperative includes as covert request for the listener to make the choice to carry out a single, specific action (refer to Figure 4 in Section 2). In the context of a single action, the imperfective is employed when a request for the listener to make the choice is infelicitous: the time for the choice to be made is already past. That is to say, the imperative is uttered after the choice has been made, but before the action is carried out; this configuration is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 The Russian imperfective imperative referring to a single event to be completed.

Following Šatunovskij’s idea that the choice to carry out an action is in a sense its real beginning – or at least inseparable from it, particularly in the case of imperatives, the schema given in Figure 5 means in fact that the speech time falls in medias res, inside the action. Thus, the perspective of the speaker is internal to the action, similar to the construal of a situation as an ongoing process, and the choice of the imperfective is motivated according to one of the chief meanings of the imperfective in Russian and other languages. (Recall also from Section 1 that the construal of a situation as an ongoing process is an instantiation of temporal definiteness, the semantic category expressed by the Russian imperfective.) The internal perspective of such imperfective imperatives is an extension, in that the action to be carried out by the verb itself, e.g. firing a shot in example (20b), is not construed as a process; rather, the internal perspective is a meta-discourse phenomenon. It should not come as a surprise that a meta-discourse refraction of the internal perspective of the imperfective would arise in a verb form that always occurs as a negotiating tool between discourse participants.

Before going on to discuss the discourse contexts in which the construal rendered in Figure 5 is relevant, it is worthwhile to mention a figurative, monologic use of imperfective imperatives in Russian that in my view is a piece of convincing, if circumstantial evidence that imperfective imperatives do express the construal of Figure 5. This use is termed by Jászay (Reference Jászay1995) the ‘imperative of compulsion’: a speaker is forced to do something s/he does not want to do and expresses that fact in monologic discourse by an imperfective imperative, as in example (21) (taken from Jászay Reference Jászay1995: 350).

Jászay (Reference Jászay1995) points out that such imperatives only occur in the imperfective. Such imperatives should be considered a kind of free direct discourse, i.e. the speaker ‘quotes’ a real or imagined imperative addressed to him/her. Following Gasparov (Reference Gasparov and Šeljakin1978), Jászay assumes that the reason for the imperfective in this construction is that the action takes time. However, it is a fact that people reflexively think that the things that they are forced to do to be lost time, i.e. to take too much time. Moreover, Jászay points out that this construction may be used by someone who will refuse to carry out the action, i.e. who is not currently engaged in it as a process.Footnote [10] Therefore, it makes just as much sense to explain the aspect of this construction as a consequence of the power dynamic of the situation, i.e. with the fact that the speaker has not been given the courtesy of making the choice to carry out the action or not, since it is forced on him/her.

This last point brings us to the issue of who makes the choice. There are two possibilities: (1) at speech time, the speaker knows or infers that the listener has already made the choice to perform the action; (2) at speech time, the speaker, for one reason or another, has made the choice for the action to be performed in the place of the listener. These two possibilities are now discussed in order.

According to Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009), the single most important factor triggering the imperfective in imperatives urging the listener to carry out single actions to completion is whether the listener has already made the choice to perform the action or not. If s/he has not, then the perfective is ordinarily the choice (recall Section 2 above); if the listener has already made the choice to perform the action, then the imperfective is the default choice, as in example (20b). The relevance of the listener’s choice for aspectual coding is seen quite easily in two common cases of the imperfective – polite invitations (22a; taken from Šatunovskij Reference Šatunovskij2009: 262), and polite expressions of permission (22b; taken from Benacchio Reference Benacchio2010: 56).

According to Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 261–262), in (22a) the imperfective is felicitous precisely because the addressee has already chosen to carry out the actions involved in the script situation, and the speaker knows it and simply gives the signal for the addressee to carry out the actions. Indeed, shared script knowledge allows the speaker to infer that the listener has made the choice to carry out the actions of the script (including, e.g. scripts such as a visit to the doctor or a university oral exam). Likewise, Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 263–264) observes that the politeness effect of (22b) lies in the fact that the speaker approves of the addressee’s prior choice and supports it, and again, all that is left to do is signal to the addressee to proceed with the action.

It is important to point out that politeness is not inherent in the use of the imperfective imperative in permissives. Another response to the question in (22b) is the imperfective imperative Otkryvajte! (open.imp.form.ipfv) without the encouraging adverb and different intonation, which communicates gruff indifference (Benacchio Reference Benacchio2010: 56) or indifference (Šatunovskij Reference Šatunovskij2009: 265). Again, according to Šatunovskij it is the speaker’s realization of the listener’s prior choice that produces the effect: What can I do? – You have already chosen to do it, so go ahead. But even politeness and gruff acquiescence are only two possibilities. Consider example (23), which seems to be neither, but rather a devil-may-care agreement with the listener. The context is the retreat of a Soviet unit in WWII, and the issue is what to take along and what to destroy. A staff clerk asks the quartermaster whether they should take the unit’s strongbox along or burn it, with a stated preference for the latter, and the quartermaster tells him to burn it:

The quartermaster is simply acting on his recognition of the preference voiced by the staff clerk, which he endorses. If anything, the pragmatic effect here is one of impatient agreement with the listener. Thus, even on the basis these limited examples it is clear that there are no consistent politeness effects of the imperfective imperative in such usage – rather, there is a range, depending on the speaker’s attitude toward the action that the listener has already chosen to carry out.

The preceding analysis closely follows Šatunovskij’s (Reference Šatunovskij2009) view of the importance of a prior choice by the listener to carry out the action for the aspectual coding of imperatives. Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 270) analyses other imperfective imperatives urging the listener to carry out a single completed action in contexts in which the listener has not made the decision as the effect of deontic modality – the listener is aware that s/he should carry out the action under the circumstances. Cases in point are (24a, b).

While it is true that these imperatives can occur when the listener is already aware that s/he is not welcome, they are also felicitous without forewarning, if the speaker blows up at the listener.

I think it is preferable to analyze such usage as cases in which the speaker has already chosen what the listener should do, and is not making the face-saving gesture of giving him/her the opportunity to make the choice to carry out the action. The assumption that the speaker is not treating the listener with such negative politeness accounts very easily for the invariably rude nature of such imperatives.

Two other cases provide further evidence that some cases involve the speaker making the choice for the listener: (1) particular cases when the listener is not in a position to make the choice, and (2) emergencies in situations when the speaker sees an imminent threat/danger to the listener, who must act immediately to avoid bodily harm, without thinking, at the speaker’s direction. An example of each is given in (25a, b).

In (25a), the child is asleep, and cannot have made the decision to wake up at the present time, and the speaker must invariably make the decision for the listener himself; indeed abrupt mands to wake up when someone is sleeping or to get up when someone is relaxing are typically imperfective in Russian. In (25b), the listener is unaware of the imminent danger (e.g. a tea kettle about to explode) and there is simply no time to request that s/he make a choice; rather, the speaker has extraordinarily suspended the listener’s decision-making power, in the interest of his/her timely avoidance of the danger. Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009) considers imperfective imperatives of this type to be a form of ‘compression’ – the choice is skipped. However, this view takes the speaker out of the equation, and as it is clear that the speaker has made a choice that the action should be carried out (which is what all imperatives communicate, regardless of aspect), there is no reason to assume that the imperfective imperative does not communicate that the speaker has made the choice for the listener.

Another case in which deontic modality runs into difficulties is the mand to surrender, as in (26).

In this case, members of a German air crew have holed up in a wood and are surrounded by Soviet soldiers. The Germans’ sense of obligation is in fact the opposite: their sense of duty is to avoid surrender (and surrender usually ensues when soldiers feel they have no choice if they are to survive). The most that can be said is that they are aware that the Russians want them to surrender. But again, the intention of the speaker for the listener to carry out an action is true of all imperatives, in either aspect. It is simpler to assume that such cases of duress imperfective imperatives communicate a suspension of the listener’s decision-making power on the part of the speaker.

If we analyze imperfective imperatives to carry out single completed actions as cases of these two variants (the speaker knows that the listener has already chosen to carry out the action, or the speaker has assumed the right to make the choice for the listener and is imposing it on the latter), then the bulk of imperfective imperatives referring to single completable actions are accounted for in a unified fashion – both cases are instantiations of the schema given in Figure 5.

There are a range of cases in which the speaker makes the decision for the listener. We can divide them into an ‘uncompromising/stern’ variant and an ‘empathetic/gentle’ variant. The uncompromising/stern variant includes on the one hand urgent situations – emergencies, as in (25b) above, and threats/duress, as in (26) – and on the other, institutional contexts in which the speaker makes choices for the listener(s). A major case of the latter are military orders. Examples are given in (27).

Example (27a) is spoken by a major to his subordinates as he explains the plan of their unit’s impending withdrawal. He is the one who makes the decisions, and his subordinates are supposed to mechanically do as they are told. In (27b) a subordinate has asked his superior whether to lay a usual third row of mines; the superior responds in the negative and orders him and his men to go to the fourth section and lay mines there. In (27c) an officer orders his unit to form up – again, the soldiers are not supposed to think about whether they want to do it, but just do it. In all of these cases the superior’s command is to be executed without hesitation, regardless of whether the command is urgent (as in (20a) above) or not. Note also that it is typical of such situations that the listener is supposed only to do what is requested and then await further orders; in that sense such imperfective orders do not refer to larger episodes, but only to single actions in isolation, in a manner similar to imperfective statements of fact (see Section 1.2 above).

In the case of military orders, Šatunovskij’s idea of deontic modality, the awareness of the listener that s/he is supposed to do what the speaker says, certainly applies. However, military orders can likewise be analyzed as cases in which the speaker has made the decision for the listener and does not give him/her the opportunity to make the choice as a face-saving gesture. Indeed, if there is a case when negative politeness were institutionally recognized as inappropriate, it would be military orders.Footnote [11]

Commands given by military superiors are not always in the imperfective; they can switch to the perfective for various reasons. As pointed out in Section 2, superiors can employ the perfective imperative as a request, as in example (28a), which is spoken by the officer of (27a) shortly after the planning of the withdrawal, to two of his officers. Example (28b) is spoken by a commander to two soldiers to be left behind to hold off the Germans as a rearguard while the rest of the unit slips away.

In (28a), though the commander expects the two subordinates to comply, he is treating them more as individuals without an authoritative step-by-step command, as his intention is to offer them a drink and have a frank discussion with them about their situation.Footnote [12] In (28b), the first and last order are the basic, categorical orders (the two men cannot haul the machinegun away and escape, and everyone knows that the unit needs all the ammunition it can salvage); the middle order is coded perfective because it is more of a qualifying instruction appended to the previous order and does not need to assert the speaker’s authority, which has been established in the first imperative. Further, the action of removing the bolt is to be carried out before the machinegun is abandoned, and the perfective here makes it clear that the order to remove the bolt is causally connected to the order to ditch the machinegun.Footnote [13]

Let us now turn to the ‘empathetic/gentle’ variant. It involves the speaker attempting to make a decision for the listener, and in some cases the speaker acts as if s/he knows what is best for the listener, outside of any hierarchy of authority or emergency situation. A common case is where the speaker uses his/her ‘leverage’ with a loved one to get him/her to do what the speaker thinks is best for them, as in (16).

In this example a married couple shares a train compartment with an elderly professor. While the wife and the professor are talking in the evening, the husband comes back from a get-together in another compartment, perhaps slightly intoxicated and in any case obnoxiously intruding on their conversation. At this point his wife uses her influence as his spouse to get him to lie down and go to sleep. She has made the decision for him, not in an authoritarian way exactly, but as someone who knows him well and knows what his best for him, and who has some leverage over him as his spouse. She is also talking to him as one would to a child, which fits in with the idea that she is making the decision for him.

In the following example (30), the speaker is not close to the listener (they have just met on a flight), but empathizes with her, and the imperfective imperative expresses that empathy (see a similar example in Benacchio Reference Benacchio2010: 49).

In this case the speaker is trying to be considerate of the woman’s situation since she has to go off to get her luggage while he looks for a car that is supposed to pick them up. His empathy allows him to recognize the trouble that lugging the bag while getting her luggage will cause her, and so he acts on his idea that he knows what is best for her. In other words, he is assuming the assertive role of a cavalier. It is also worth pointing out that this case borders on the first type, in which the speaker knows that the listener has made the choice to carry out the action, in that the speaker assumes that the listener will carry out the action if given the chance. Such helpful suggestions frequently occur in the imperfective. This example is not as firm as the one in (29); note also that the perfective dajte (give.imp.form.pfv) is also possible in this context (see Benacchio Reference Benacchio2010: 49), but is more impersonal as it expresses the negative politeness of giving the listener the opportunity to make up her own mind about her own affairs.

Yet another case is given in (31), in which an invitation is combined with a prior decision by the speaker to create a kind of appeal:

In this example an officer is inviting a soldier who has served as his driver and who has come to say goodbye. The officer and the soldier are attached to one another, and the officer would really like for the soldier to come and see him if he is in Moscow. While this might be analyzed as an invitation, it’s a little stronger, and the officer has already made a decision that he would like to see the soldier again; communicating this will dispel any doubt the soldier could have about whether he should contact the officer. This decision results in a kind of appeal, which approximates the force of the English translation ‘do come by or give me a call’.

To sum up, this section has argued that the great bulk of imperfective imperatives urging the listener to carry out a single action to completion can be analyzed as cases in which the time for the choice to carry out the action has already elapsed (Figure 5), and thus represent an extension of the processual variant of the imperfective aspect. There are two main types: (i) the speaker knows or infers that the listener has already made the choice to carry out the action; and (ii) the speaker has taken the liberty to make the choice for the listener, and requests that the action be carried out without further ado. The latter type also has a range of contextual variants that can differ considerably in the strength of the illocutionary force exerted in the mand.

4 Negated imperatives

Based on the analyses of aspectual usage presented in Sections 2 and 3 above, this section presents a brief analysis of aspectual usage in negated imperatives, arguing that imperatives under negation can be accounted for with the same mechanisms used above. Negated imperfective imperatives are treated first, followed by negated perfective imperatives.

While in past-tense narratives perfective verbs are quite compatible with negation to signal that an entire event has failed to occur at a particular point in time, in sequence with other events (see Dickey & Kresin Reference Dickey and Kresin2009), such temporal specificity relative to other events rarely, if ever applies to negated imperatives. Rather, imperatives under negation ordinarily entail a lack of change and thus continuity (see Leinonen Reference Leinonen1982: 258). The temporal extension of such negated predicates is a case of temporal indefiniteness as described in Section 1.2. The connection between the temporal extension of negated commands and temporal indefiniteness applies to general prohibitions, requests not to perform or to discontinue an activity, as well as requests not to perform single completable action.

Negated imperatives functioning as general prohibitions and/or referring to events construed as processes are always imperfective, as is the case in affirmative imperfective imperatives, see the examples in (32).

Among negated imperatives general prohibitions with unrestricted temporal validity, e.g. (32a), are quite common, which explains why negated imperfective imperatives are so frequent (note as well that negative adverbials, e.g. nikogda ‘never’ are not necessarily present – negated imperfective imperatives function quite commonly on their own as general prohibitions). Negated activities, e.g. (32b), due to the indefinite temporal extension of the negated predicate are likewise cases of temporal indefiniteness. At the same time, the nature of such prohibitions, whether general or not, usually require some kind of authority on the part of the speaker: only someone with some kind of authority or assuming it can prohibit someone from doing something they have chosen or might choose to do.

Commands urging the listener not to carry out a single action to completion operate more or less according to the same principles. Consider (33).

Example (33) is a mand to not close the bag not only at the very next moment, but also for the time being, until the speaker gives another instruction. This example is a simple request for cooperation; in cases when the speaker is exercising authority, such negative imperfective imperatives are prohibitions; otherwise it can be an appeal. Indicative of the fact that simple negative mands requesting cooperation are not necessarily stern prohibitions is the fact that can be polite: they can occur with the tag question ladno? ‘okay?’ or požalujsta ‘please’ (recall the discussion in Section 2).

While mands not to do something are fairly clear cases of temporal indefiniteness, it is interesting that Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 285) assumes that imperfective imperatives instructing the listener not to carry out a single completable action such as (33) are spoken only once the listener has chosen to carry out the action in question (or rather, when the speaker knows or infers that the listener has made the choice). Consider the following example from Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 289).

According to Šatunovskij, (34) can only be uttered once the listener has already chosen to shoot and is prepared to do so. Šatunovskij’s intuition in fact comports with views on the general semantic nature of negation. For instance, Givón (Reference Givón and Cole1978: 105–108) suggests that negative propositions have a ‘marked presuppositional status’: taken from the infinite set of non-events that could potentially be mentioned, a particular non-event becomes relevant as a figure only when the corresponding positive event is presupposed as a ground. Applying this idea to conversational discourse and imperatives, we can say that the positive event is presupposed and ‘part of the ground’ when the listener has already chosen to carry out the action.Footnote [14] That is to say, the imperfective imperative occurs after the choice and before the action (see again Figure 5). Note that in the case of a negative imperative requesting the cessation of an activity, as in (32b), the listener must have chosen (even if by agreement) to carry out the activity, whereas general prohibitions, as in (32a), the choice can only be considered as part of hypothetical condition (‘in the event that you decide to throw bread into the trash, do not do so’), based on an inference by the speaker that the listener is likely to choose to carry out an action if the situation arises.

Thus, there are two motivations for the imperfective in prohibitions and negative instructions. The temporal indefiniteness of the negated situation itself is sufficient to motivate the imperfective. However, the idea that such imperatives reflect the involve the prior choice of the listener is difficult to ignore, and I consider it possible that the two semantic elements converge to motivate the imperfective in prohibitions and negative instructions. In such imperatives, the negation does not negate the prior choice, only the execution of the chosen action. That is to say, negation appears have scope only over the situation expressed by the verb: ‘do not do what you have chosen to do’. This is why negated imperatives almost invariably represent an attempt to ‘override’ the listener’s prior choice by the speaker.

Let us now turn to negated perfective imperatives, which have a very restricted use in Russian. They are preventives, i.e. mands that serve to warn someone from doing something inadvertently, as in (35).

Note that (35a) is a completely accidental predicate resulting from prototypical inattention, whereas in (35b), in which the scaring away is also inadvertent, the possible undesirable event is tied to a particular agentive process (choosing a dress). Perfective verbs that are agentive can also occur in this construction, as in (36), but these tend to be humorous comments as opposed to real warnings.

Negated perfective imperatives have been analyzed by Xrakovskij (Reference Xrakovskij1988) and Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 290) as simply negating the result of the situation, i.e. as meaning ‘do not attain the result of the situation’. I see a problem with their approach if Šatunovskij’s hypothesis that the perfective imperative communicates a request to make a choice to perform an action, as diagrammed in Figure 4, is accurate. In particular, what does the negation mean for the choice? As Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009: 288) points out, it makes no sense for a negated perfective imperative to communicate the message ‘do not make the choice to perform P, and do not perform P’.

A solution is to be found by simply assuming that in contrast to negated imperfective imperatives, the perfective aspect has scope over the negation. Thus, a negated perfective communicates the following meaning: ‘make a choice not to perform P and do not perform P, thereby avoiding its result’. This view comports with Zorixina-Nilˈsson (Reference Zorixina-Nilˈsson, Josephson and Söhrman2013: 95, 98), who emphasizes that negated perfective preventives communicate that the listener should exercise mental control over his/her actions so that the undesired event does not take place. With inadvertent actions such as those in (35), the listener probably does not want to perform an action with an undesirable result, and in some sense has ‘made the choice not to perform the action’. However, such warnings are only uttered when the speaker infers that the listener might not be paying sufficient attention to the situation. In this case, we may say that the ‘the request to make a choice’ is in fact a request for the speaker to take control of the situation by expending mental energy to avoid the undesirable action and its result. It is interesting that an anonymous referee has noticed a parallel between the negative politeness of affirmative perfective imperatives (concern aimed at avoiding risk to the negative face of the listener) and the concern for the welfare of the listener in negated perfective imperatives. I would argue that it is the inclusion of a conceptual point in time for the listener to engage his/her own decision-making power that ultimately produces this accommodation of the listener on the part of the speaker.

Circumstantial evidence for the request that the listener exercise mental control in negated perfective imperatives is the fact that negated perfective imperatives commonly occur with the imperfective imperative smotri ‘watch/look’, as in (37), for example.

The imperative smotri, which could be translated as ‘watch out!’, is nevertheless a bare form of ‘watch/look’ and has been grammaticalized as a signal indicating that the listener should direct their attention/mental energy in a manner specified by the speaker. The frequent collocation of smotri and a negated perfective imperative can be taken to indicate a strengthening of the request that the listener exert mental control over the situation.

The analysis proposed here has the advantage of motivating negated perfective imperatives as straigtforward instantiations of temporal definiteness as applied to imperatives: the prior decision not to allow an event to occur is a conceptual moment in time that comprises one element of the sequentiality inherent in an action viewed as temporally definite. Moreover, this account does not suffer from the incoherence of the traditional view that negated perfective imperatives focus on the result, whereas negated imperfective imperatives focus on the action itself: commands are all about how the speaker wants the world to be, and negated imperfective imperatives are also given to prevent certain results from coming about. Thus, in (33) above the imperfective imperative is motivated by the speaker’s desire for the bag to remain open every bit as much as (35a) is motivated by the speaker’s desire for the keys to remain unforgotten.

To sum up, this section has shown that aspectual usage in negated imperatives is dependent on the same basic factors as aspectual usage in affirmative imperatives. Commands to not perform an action almost always allow the lack of the situation to be construed as extended in time, i.e. temporally indefinite, motivating the imperfective. At the same time, such commands (with the sole exception of mands never to do something) are difficult to imagine in a situation in which the listener has not already contemplated the action. The biggest difference is that negated imperfective imperatives often correspond to affirmative perfective imperatives. Thus, whereas an affirmative imperative often needs to communicate the request for the listener to make the choice and is thus temporally definite, a negative imperative is most likely to be an attempt to override an inferred prior choice, and in any case is temporally indefinite as mentioned above. In negated perfective imperatives the perfective has scope over the negation, with the result that the meaning is for the listener to ‘make a choice’ not to perform an action that might not have been the object of their current attention.

5 Summary and concluding remarks

The preceding sections have attempted to describe the dominant functions of the perfective : imperfective opposition in imperatives in Russian. Following Šatunovskij (Reference Šatunovskij2009), it has been argued that perfective imperatives communicate a covert request for the listener to make the choice to perform an action and then to perform it to completion with a desired outcome, which is an instantiation of temporal definiteness (i.e. the assertion of temporal sequencing, see Figure 4). Imperfective imperatives occur, similarly to imperfectives in tensed usage, to cancel the temporal links asserted by the perfective; this semantic category is termed temporal indefiniteness, and in affirmative imperatives has the following main instantiations: (i) to request that an open-ended activity be resumed or continued, (ii) to request the habitual repetition of an action, and (iii) in the case of single completable actions to signal that the time for the listener to make the choice to perform the action has already passed (Figure 5; an extension of the process meaning of the imperfective). If the time has already passed for the listener to make the choice, then there are two possibilities: either the speaker is acting on his/her knowledge that the listener has already made the choice to perform the action, or s/he is communicating that s/he has made the choice for the listener. This last case has a variety of instantiations ranging from emergency warnings and hierarchies of authority to milder variants where the speaker takes it upon himself/herself to make a decision in the best interests of the listener.