This is a study of five specimens from a group of religious visual artefacts spanning about a millennium in Chinese history and coming from sources included in the Taoist Canon (Zhengtong daozang 正統道藏), a mid-fifteenth-century collection of about 1,500 texts of various origins and representing various traditions.Footnote 2 All five specimens are called “Great Peace Symbol” (“Taiping fu” 太平符). By briefly introducing the source of each specimen, describing its morphology and discussing its use, I hope to improve our knowledge of the category of artefact to which they belong, the fu 符, and of some facets of its historical evolution.

A foreword on terminology

In his Explanation of Graphs and Analysis of Characters (Shuowen jiezi 說文解字), the first Chinese graphological dictionary, completed by 100 ad, the Chinese scholar and official Xu Shen 許慎 gave the following definition of the word fu:Footnote 3

符, 信也. 漢制以竹長六寸, 分而相合.

Fu is a credential. [According to] Han [漢 dynasty (206 bc–220 ad)] institutions, it is made of bamboo, six inches in length, and divided [into two halves], which are then joined to one another [for the purpose of authentication].Footnote 4

The word fu thus originates in administrative language, where it refers to an official document split in two matching halves and used for authentication.Footnote 5 A recent synthetic approach to archaeological and transmitted materials suggests that the device mostly served bureaucratic and military functions. It was used as a certificate to authenticate a liaison officer, or as a passport to cross passes and outposts or to enter the imperial capital.Footnote 6 To some extent, it may be compared to what the Romans called tessera.Footnote 7

We find the word used in the context of political legitimacy by the founding of the first Chinese Empire. Especially when combined with another word, ming 命 (a “mandate”), it refers to a token of sovereignty sent by heaven to legitimize a new emperor.Footnote 8 By the second century of our era at the latest, the word was imported into the religious lexicon where, while retaining its earlier basic meanings, it soon came to be defined as a cosmic credential and a heavenly graph or pattern.Footnote 9 But the idea that “gods matched the ‘earthly’ parts with their ‘heavenly’ part of the fu [and, if] both parts tallied exactly … were prepared to listen” to the priests asking them for help, seems to be a late interpretation not confirmed by textual evidence.Footnote 10 This interpretation echoes a statement by Anna Seidel, which is not supported by the source to which she refers.Footnote 11

In practice, these early medieval religious artefacts were esoteric figures and writings of varying complexity, drawn by specialists on specific media using special inks or powders, and endowed with various powers (some examples of which we shall discuss below).Footnote 12 Their use was not restricted to the Taoists. Rather, they were quite common among other religious traditions, including popular cults and Buddhism.Footnote 13

Fu was first translated as “magic sign”, “charm”, or “talisman” in modern Western sources.Footnote 14 John Lagerwey argued convincingly that the Chinese word shares several meanings both with the current English word “symbol” and its root word σύμβολον in Greek.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, “talisman” imposed itself among students of Taoism. A first problem with “talisman” is that it corresponds only to one of the historical meanings of the Chinese word, and not even the original one.Footnote 16 The same may be said of “charm”, also frequently encountered. In particular, both terms fail to render the earlier meanings of “tessera” and “token”. A second problem is that some talismans were called “diagram” (tu 圖), “seal” (yin 印) or “seal imprint” (yinwen 印文), not fu at all.Footnote 17 To complicate the matter further, modern Chinese scholars have used the word fu in connection with various funerary artefacts, some – but not all – of which bear inscriptions containing the character fu or identified variants of it.Footnote 18 This modern use has misled some Western scholars into calling the legal documents themselves “fu” or “talismans”:Footnote 19 their primary purpose was to protect surviving relatives from harm by placing the deceased under the jurisdiction of the otherworldly bureaucracy.Footnote 20

This case study confirms that “talisman” cannot be used indiscriminately in Western publications as a rendition of the Chinese word “fu”. Simply put, some talismans are not called fu and some artefacts called fu are not talismans. The two groups overlap, but they are not identical. Therefore, “symbol”, despite its own limitations as a translation, seems more appropriate when referring to the category of fu as a whole, and “talisman” should be reserved for relevant cases only.

1. “Li Er's Great Peace Symbol” (fourth century)

The first specimen comes from a work by Ge Hong 葛洪 (283–343) – an erudite man of Southern China who was involved in alchemy, medicine, and longevity practices – known as the Master Who Embraces Simplicity (Baopu zi 抱朴子). Composed during the first quarter of the fourth century, its final version dates to about 330 ad.Footnote 21 It is a unique testimony to the religious traditions existing in the regions to the south of the River Yangtze, prior to the penetration of the Taoist Church – the Way of the Heavenly Master (Tianshi dao 天師道) – and the Taoist revelations of Upper Clarity (Shangqing 上清) and Numinous Treasure (Lingbao 靈寶) in the mid-fourth and early fifth centuries.Footnote 22 The “inner chapters” (neipian 内篇) of this work give symbols an important role as prophylactic and apotropaic tools for resisting plague effects and avoiding death, especially in combination with a strict observance of prohibitions, and also as a means of perceiving a category of numinous minerals.Footnote 23

In a chapter devoted to the experiences of anchorites, Ge Hong introduces eighteen symbols used by travellers and hermits to ward off wilderness-specific hazards. Some, which are worn, are, correctly speaking, talismans; others, magical signs to be placed inside the footsteps of wild beasts to divert their route. In addition, all of them can be affixed to beams or columns inside buildings. Illustrations are provided.Footnote 24 The first seven symbols and the last of the series are called “Lord Lao's symbol for entering mountains” (“Laojun rushan fu” 老君入山符) by reference to perhaps the most renowned patron saint of Taoism, the deified Laozi 老子.Footnote 25 The eighth and ninth are called “Symbols to avoid tigers and wolves [when] entering mountains” (“Rushan pi hulang fu” 入山辟虎狼符). The tenth one, called “Symbol carried by Lord Lao” (“Laojun suo dai fu” 老君所戴符), is said to be efficient against ghosts, snakes, tigers, wolves, and spirits. The next three are “Symbols to hang to [one's] belt [when] entering mountains” (“Rushan peidai fu” 入山佩帶符). The last four are thus introduced:

或用七星虎步及玉神符, 八威五勝符, 李耳太平符, 中黃華蓋印文及石流黃散, 燒牛羊角. 或立西岳公禁山符. 皆有驗也.

Some use the Tiger Pace of the Seven StarsFootnote 26 along with the Jade God Symbol, the Symbol of the Eight Awe-Inspiring OnesFootnote 27 and Five Conquests,Footnote 28 Li Er's Great Peace Symbol,Footnote 29 a print from the Seal of the Sumptuous CanopyFootnote 30 of the Central Yellow as well as sulphur powder and a burned bovid horn. Others set up the Symbol of the Duke of the Western PeakFootnote 31 Prohibiting Mountain [Access]. All prove effective.Footnote 32

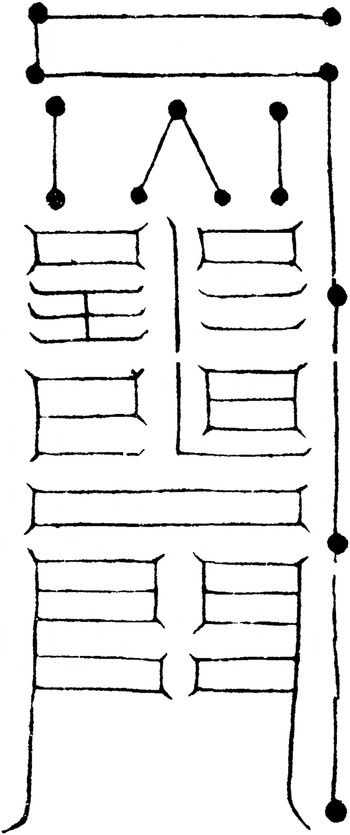

Five figures follow this section. The Great Peace Symbol being the third symbol mentioned in the preceding passage, I assume it corresponds to the third figure in the series (see Figure 1).Footnote 33 One of the most conspicuous features in this illustration is the Northern Dipper (Beidou 北斗) constellation along its top and right sides. This constellation, which is composed of the seven brightest stars in the Ursa Major of Western astronomers, is the “most prominent circumpolar asterism” of the starry sky and, as such, it has fascinated the Chinese from the earliest times.Footnote 34 In Taoism, it has played a central role in the meditation practices, liturgy, and artefact design of many traditions.Footnote 35 The three dots forming an upside-down “V” symbolize another constellation, also part of the Western Ursa Major and also a noted visual feature recurring in Taoism, the Three Terraces (Santai 三臺), and the two lines on its sides are probably also stellar references.Footnote 36 The remaining visual components also belong to the kind of symbolic grammar analysed by Monika Drexler. For example, the item “曰” (a horizontally stretched ri 日) could either symbolize the Five Agents, or the beasts emblematic of the Five Agents, or the sun or the moon, or a deity of the sun or of the moon.Footnote 37 The semiotics of individual components is liable to change from one specimen to the next and each tradition certainly used its own symbolic grammar.Footnote 38

Figure 1. [“Li Er's Great Peace Symbol”?] (CT 1185, 17.21b)

2. “Great Peace Symbol” (seventh–ninth century?)

Moving forward a few hundred years, we meet a second specimen in the Divine Symbols of the Five Peaks of the Most High Numinous Treasure of Pervading Mystery (Taishang dongxuan Lingbao wuyue shenfu 太上洞玄靈寶五嶽神符), an anonymous, undated collection, which could be a Tang 唐 dynasty (618–907) archaistic composition (CT 390).Footnote 39 The first eleven symbols are introduced by citations of an earlier collection, now lost, the Diagrams of the Divine Immortals (Shenxian tu 神仙圖). This generic title refers to a nomenclature of visual materials which have been traced back to the library of Ge Hong's master Zheng Yin 鄭隱 (c. 215–c. 302).Footnote 40 Our second specimen is thus linked to the same Southern tradition as the first one.

The present collection unfolds the following twenty-six symbols, with transmission lines or dedicated guidelines for use or worship: the five symbols of the Five Peaks;Footnote 41 six (sic) symbols of the Perfected of the Five Peaks (wuyue zhenren 五嶽真人); a “White Tiger Symbol” (“Baihu fu” 白虎符), with a rite ascribed to the three mythical rulers Yao 堯, Shun 舜 and Yu 禹; “Five stabilization symbols” (“Wuzhen fu” 五鎮符); a “Great Peace Symbol”, with a rite ascribed to Yao; seven “Awe-inspiring Virtue Symbols” (“Weide fu” 威德符); and a “Five Generals Symbol” (“Wu jiangjun fu” 五將軍符) with a military function. The whole sequence may be interpreted as a liturgy for conformity to cosmic cycles, Earth stability, and the pacification of the empire.

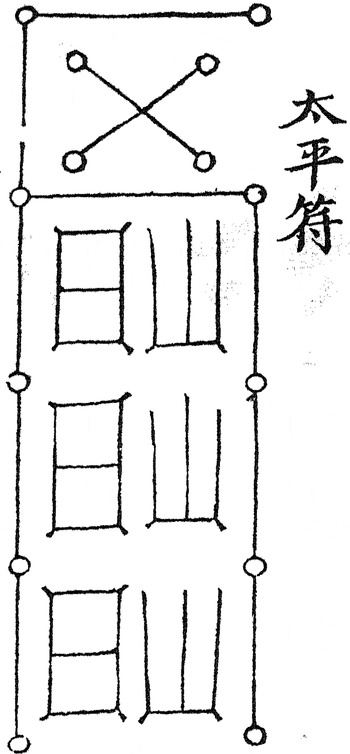

The drawing of this second Great Peace Symbol (see Figure 2) is composed of four rectangular spaces arranged into columns of two, without any obvious resemblance to our first artefact. It is followed by this text:

堯鳯凰元年正月甲子, 師巫咸受堯天子. 王有天下五嶽, 四瀆, 山川常禁司神, 天有厭鎮. 以威四海, 服八夷, 兵寇不起, 疾疫自除. 與響相應, 神常助之. 祭法: 用三牲物牛角五寸, 羊角七寸, 䐗百二十斤; 清酒五斛, 黄粢米飯, 果實; 十二香火, 毎面三枚; 壇面二十八丈; 白茅爲蓆, 長二尺二寸. 亦用粢米五斗; 千二百杯, 面四百杯; 二丈八尺長竿, 立之中庭; 十二丈旛, 四方等; 五大案二十四杯, 合百二十杯; 五色相校; 書繒四丈一尺. 清人, 公子, 內臣臨祭三日受戒. 元年三月, 祭受福氣見; 三月,令平氣見; 三年, 天下太平.

In the first year of the Fenghuang [era] of Yao's [rule], during the normative (=first) month, on the first day of the sexagesimal cycle, WuxianFootnote 42 the master recognized Yao as Son of Heaven. The king (Yao) had the Overseers of the DeitiesFootnote 43 of the Five Peaks, Four Rivers,Footnote 44 mountains and waterways of the realm permanently prohibited, thereby bringing stability to Heaven. By inspiring awe to the four seas and subduing the Eight Barbarians,Footnote 45 [he] prevented armed brigands from rising, and epidemics spontaneously dissipated. Responding like an echo, the gods assisted him constantly. Sacrificial method: Use the three domestic animals [under the species of] a five-inch long ox horn, a seven-inch long ram horn, and 120 cattiesFootnote 46 of pork [meat]; 5 bushelsFootnote 47 of sacrificial wine; yellow sacrificial millet, husked and cooked, and fruits; twelve sticks of incense, three on each side; an altar, 28 toisesFootnote 48 a side; weedy grassFootnote 49 for the mats, [each] two feet and two inches long. Also use 5 pintsFootnote 50 of husked sacrificial millet; 1,200 cups – 400 cups a side; a bamboo pole, two toises and eight feetFootnote 51 long, erected in the centre of the area; 12 toisesFootnote 52 of banner arranged on the four sides; five large tables [with] 24 cups [each] – 120 cups in all; [soil] of the five colours in matching proportions;Footnote 53 4 toises and 1 footFootnote 54 of calligraphy silk. The pure ones, the noble scions,Footnote 55 and the court dignitaries attended the sacrifice and received the precepts for three days. In the third month of the first year, the sacrifice obtained the appearance of blessed pneumata.Footnote 56 In the third month, it made the pneumata of Great Peace appear. In the third year, the realm [knew] Great Peace.Footnote 57

Figure 2. “Great Peace Symbol” (CT 390, 11b–12a)

This text opens and closes as a narrative of sovereignty, while the intervening part unfolds detailed preparations for a rite whose ultimate purpose is to establish Great Peace, a potent concept evoking a golden age of perfect universal harmony and its re-actualization.Footnote 58 This ritual performance by a mythical Chinese figure at the beginning of his rule goes far beyond the production of a talisman. The name of the illustrated symbol has clearly retained one of the early meanings of fu, “token” – a token of the advent of Great Peace.

In mythical context, the rite marked the founding of a new political and religious order. In the present liturgy, by preparing the rite as prescribed and performing it, the officiating Taoist re-enacts a founding liturgy of power and thereby restores cosmic equilibrium.

*

Our final three specimens come from sources which date from within a century or two and appear in the context of Taoist liturgy as performed by a trained officiant on behalf of an individual or a community. They share an internal use, as all three were to be physically ingested during the religious service.

3. “Great Peace Symbol” (thirteenth century)

The third specimen is found in the Jade Mirror of Numinous Treasure (Lingbao yujian 靈寶玉鑑), an undated, anonymous manual, whose contents borrow from different Taoist traditions (CT 547). Incomplete, its present edition seems not to predate the thirteenth century.Footnote 59 Preceding the work, the Lingbao yujian mulu 靈寶玉鑑目錄, its table of contents (CT 546), mentions a “Great Peace Symbol” under the heading of chapter 18. This chapter belongs to a series of five consecutive chapters (17–21) identically titled “Class: Flying deities visiting the [Heavenly] Emperor” (“Feishen yedi men” 飛神謁帝門)Footnote 60 and devoted to divine petitioning from different traditions, most notably Orthodox Unity (Zhengyi 正一).Footnote 61 In the usual bureaucratic fashion, these rites consist of sending a divine emissary to petition the supreme deity on behalf of the supplicant. The “Great Peace Symbol” first appears in the description of an Orthodox Unity “Method for submitting petitions and performing ablutions” (“Shangzhang muyu fa” 上章沐浴法). This ritual sequence is thus introduced:

凡爲國爲民上章拜表, 非一日一時所可行之事. 須於日前, 調運身心, 令神炁泰定. 沐浴七日, 服五神符, 誦五神呪; 七日, 服太平符; 七日, 服通神符. 遇立夏日, 伐棗木造丹元君一身, 如真人狀, 長三寸廣七分, 同沐浴入室. 行持四十九日. 次服心章符. 庶通達誠意, 上合天心, 元氣自升矣.

Generally, submitting a petition or addressing a memorandum on behalf of the dynasty or the people is not a matter executable in a single day or moment. [The priest] must, before the [foreseen] day, moderate bodily activities and adopt the right mental attitude, so as to make divine pneumata stable. Perform ablutions for seven days, [then] absorb a Five Gods Symbol and chant the invocation to the Five Gods.Footnote 62 [After] seven [more] days, absorb a Great Peace Symbol. [After] seven [more] days, absorb a Symbol for Transmission to the [Heart] God. [When you] come across the first day of Summer,Footnote 63 cut down a jujube tree and model a figure of the Lord of Cinnabar Prime, similar to a Perfected, three inches long and seven-tenths [of an inch] wide; together with [this figure], perform ablutions and enter the oratory.Footnote 64 Keep practising for forty-nine days. Next, absorb a Heart Petition Symbol. Should [you] convey intentions with sincerity, [they will] unite with the mind of Heaven above, and primordial pneuma will spontaneously ascend.Footnote 65

Extending over several months, this ritual preparation demands a remarkable investment both in time and discipline. It includes the oral absorption of four symbols (discussed and given illustrations in the chapter) and the chanting of invocations. On a given calendar conjunction, the priest is requested to carve a small wooden figure of his or her own most vital corporeal god, the Lord of Cinnabar Prime (Danyuan jun 丹元君), the deity of the organ heart.Footnote 66

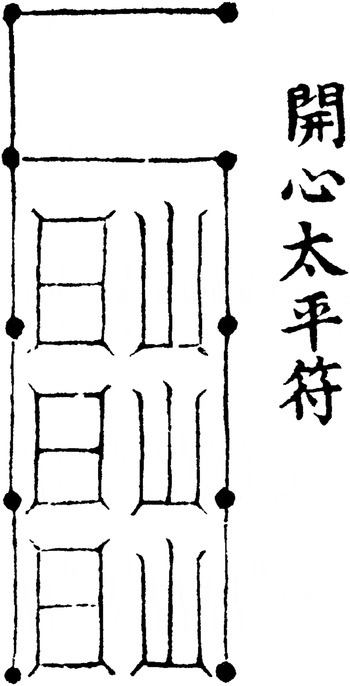

Next comes the recipe of a seven-ingredient decoction designed for the ritual bath where the ablutions should take place (jian yutang 煎浴湯) every day at the seventh (wu 午) hour (noon). The recipe is followed by an invocation to be chanted, and by the illustrations of the “Five Gods Symbol”, to be swallowed (tun 吞), and of a “Symbol to Purify the Unclean [while] Performing Ablutions” (“Muyu jinghui fu” 沐浴淨穢符), to be dissolved (hua 化) in the bath. Each symbol comes with an invocation. Then the illustration of the “Great Peace Symbol” is given (see Figure 3). This symbol shares with our former two specimens a vertical structure and, with the first one, the schematic rendition of the Northern Dipper in the same location. However, the seven extra dots form different groupings – an X-shaped group of four inside the “bowl” of the Dipper, and three linked dots connected to the lower left angle of the “bowl”. The former group could be a representation of the twenty-eight Lodges (xiu 宿) organized into four series of seven.Footnote 67 On the basis of the first specimen, the latter group seems to be a linear, “flattened” rendition of the Three Terraces constellation. The central part combines items similar to the regular Chinese characters ri 日 and shan 山, both featured three times – here again, these are not characters but visual elements pertaining to a symbolic grammar. The latter (“山”) may symbolize various deities of the Taoist pantheon.Footnote 68 Next comes a set of guidelines:

右符以燈心棗湯化服. 想丹元君㝠坐絳宮, 黙念三天隱諱, 泓, 澄, 明, 八十一徧, 乗三素雲上升玉堂玉帝訣. 呵氣于身, 次調息, 咽津九過.

The preceding symbol is to be absorbed, dissolved in a decoction of lamp wickFootnote 69 and jujube. Think about the Lord of Cinnabar Prime quietly sitting in the Crimson Palace.Footnote 70 Silently recite the hidden, avoided names of the Three Heavens, Immense, Clear, and Luminous,Footnote 71 eighty-one times, and the Instructions of the Jade EmperorFootnote 72 for Riding the Clouds of the Three Original ColoursFootnote 73 and ascending to the Jade Hall. Breathe the air out of the body, then regulate breathing and swallow saliva nine times.Footnote 74

This ritual segment, included in the liturgical sequence of ablutions, includes visualization, recitation and breathing practices.

Figure 3. “Great Peace Symbol” (CT 547, 18.25a)

4. “Great Peace Symbol Opening the Heart” (mid-fourteenth century)

A few decades later we meet a fourth specimen in the Pearls Bequeathed from the Sea of Rites (Fahai yizhu 法海遺珠), a liturgical compendium in 46 chapters (CT 1166). A preface by one Zhang Shunlie 章舜烈, where the year 1344 is mentioned, has led modern scholarship to ascribe the whole work to the fourteenth century. This compendium reflects one of the traditions collectively known as Thunder Methods (Leifa 雷法), which developed during the eleventh century.Footnote 75 It is assumed to document practices prevalent to the south of the River Yangtze from the twelfth to the fourteenth century.Footnote 76

In chapter 19 of the compendium, the last ritual sequence, called “Secret method for petitions and memorials of the Numinous Treasure” (“Lingbao zhangzou mifa” 靈寶章奏祕法), includes a shorter variant of the Orthodox Unity “Method for submitting petitions and performing ablutions” appearing in the source of our third specimen. This ritual sequence opens with a set of prescriptions and an invocation:

凡未拜章, 七日之前, 齋戒三日, 入靖不交人事. 每日作用心章符, 太平符, 伏章符, 向旺方以淨水吞之. 服時, 含符於口中, 舌拄上腭, 仰面看東方, 以鼻引青炁, 在口存青炁; 次仰看天上, 以鼻引紅炁入口; 次俯看地下, 以鼻吸地中黄炁入口; 存三色炁, 混合併在口中, 團成一丸燦爛, 光芒如日; 存符在光中, 以水吞下. 毎日服符之次, 持念通章呪曰:

心中神, 丹元君, 長三寸, 廣七分, 着朱衣, 繫絳裙, 乗威德, 顯至靈, 通造化, 達至真, 住心中, 莫離身. 外有急事, 疾來告人; 今有心章, 伏請報應, 急急如律令.

Generally, seven days before presenting a petition, observe abstinence for three days, enter the oratory,Footnote 77 and do not meddle in human affairs. Each day, prepare for use a Heart Petition Symbol, a Great Peace Symbol, and a Deferential Petitioning Symbol. Swallow them with pure water, facing the dominant direction.Footnote 78 Place the symbols to absorb in the middle of the mouth, press the tongue against the palate, raise the face and look to the East; inhale green pneuma through the nose and keep it in the mouth. Next, raise the head and look to Heaven above; inhale red pneuma through the nose, and [make it] enter the mouth. Next, incline the head and look to Earth below; through the nose, inhale yellow pneuma from the centre of Earth and [make it] enter the mouth. Visualize the pneumata of the three colours and merge [them by] assembling [them] in the middle of the mouth and rolling [them] into a brilliant pill, resplendent as the sun. Visualize the symbols in the middle of the light, and swallow [them] with water. Each day, after absorbing the symbols, observe the recitation of the [following] Invocation for the Transmission of the Petition:

“God in the centre of [my] heart, Lord of Cinnabar Prime, three inches long and seven-tenths [of an inch] wide, wearing a vermilion-red tunic and a crimson-red skirt, controlling awe-inspiring virtue and manifesting the supremely numinous, understanding creative transformation and reaching supreme perfection. Stay in the centre of [my] heart and do not leave [my] body. There is a pressing matter outside, in haste [I] come to call upon you. Now here is a Heart Petition, deferentially [I] ask [you] to report in answer. Promptly, pursuant to the statutory orders.”Footnote 79

Both the set of prescriptions and the invocation to the Heart God have already appeared in the source of our third specimen, albeit differently ordered within the liturgical sequence.Footnote 80 The size of the wooden figure to be carved in our third source here applies to the Heart God itself as visualized by the officiant. The illustration of the Heart Petition Symbol and the ritual guidelines for its production and absorption lead to the illustration of a “Great Peace Symbol Opening the Heart” (“Kaixin taiping fu” 開心太平符) (see Figure 4). This illustration is mostly identical to the third artefact, except that in the upper register, the four dots joined by two strokes forming an X are lacking, rather a deliberate alteration than the accidental result of a defective master woodblock or printing process.

Figure 4. “Great Peace Symbol Opening the Heart” (CT 1166, 19.21a–b)

The phrases “Opening the Heart” and “Great Peace” from the name of the symbol occur again in the rhymed “Imperious Invocation” (Chi zhou 敕呪) subsequently given:

- 飡食神符

[I] ingest the divine symbol and

- 通招真靈

Communicate with the Perfected and Numina, beckoning them.

- 百神走使

All the gods enter [my] service,

- 調徹中情

Harmoniously penetrating [my] innermost conscience.

- 六甲肅衞

The Six Jia,Footnote 81 [my] Majestic Guardsmen,Footnote 82

- 淵淵清清

Are unfathomable and crystal-clear

- 五行元炁

The Five Agents and primordial pneuma,

- 窈窈冥冥

Fathomless and inconspicuous.

- 混沌未始

Chaotic, not yet begun,

- 百物逃形

All beings refrain from taking shape.

- 聞色已知

By perceiving forms [I] already know

- 天地神經

The divine scriptures of Heaven and Earth.

- 號曰開心

[They] call [this symbol] “opening the heart” and

- 服之太平

By Absorbing it one [brings forth] Great Peace.

- 達知自然

Reaches the knowledge of naturalness,Footnote 83

- 飛升紫庭

And ascends, flying, to the Purple Court.Footnote 84

急急如上帝律令

Promptly, pursuant to the statutory orders of the Emperor on High.Footnote 85

Thus “to open the heart” means to interiorize the pantheon and to become aware again of one's inner primordial chaotic state, corresponding to an early stage in cosmogony, filled with limitless potential. The chapter ends without further mention of a Great Peace Symbol, but all these elements will also be found in the source of the fifth specimen.

5. “Heart-Opening Great Peace Symbol for Communicating with the Perfected and Reaching the Numina” (late fourteenth-century edition)

The source of our last specimen is the Major Method of the Upper Scripture of Universal Salvation of the Numinous Treasure (Lingbao wuliang duren shangjing dafa 靈寶无量度人上經大法), a long synthesis of salvation rites for the living and the dead, in 72 chapters (CT 219). Despite the presence of two in-text references to the Ming dynasty (da Ming guo 大明國) inviting to date the canonical edition to the late fourteenth century at the earliest, Lagerwey believes that the original version of the text was put together around 1200.Footnote 86

The “Section: Circulating Gods to Join the Effulgences” (“Yunshen hejing pin” 運神合景品, Chapters 43–4) describes a ritual programme involving the circulation of the corporeal pantheon visualized by the officiating Taoist within his or her body, as he or she performs an internalized rite of divine petitioning justified by the identity of both the inner and outer divine spheres.Footnote 87 Chapter 43 displays a “Heart-Opening Great Peace Symbol for Communicating with the Perfected and Reaching the Numina” (“Tongzhen daling kaixin taiping fu” 通真達靈開心太平符). Except for a single stroke on the left of the figure, we easily recognize our third specimen. That missing stroke seems to confirm that the three linked dots on the lower left side of the figure, independent from the Northern Dipper in the present rendition, are indeed a linear rendition of the Three Terraces (see Figure 5).

Figure 5. “Heart-Opening Great Peace Symbol for Communicating with the Perfected and Reaching the Numina” (CT 219, 43.5a)

Written in reduced-size characters, a subheading adds that this symbol must be “drawn in vermilion red [ink on] yellow plain silk” (zhushu huangsu 朱書黃素). Practical prescriptions of this sort are frequently encountered in Taoist sources presenting symbols and blank forms of various religious documents. In the present case, red is the emblematic colour of the South and the organ heart in the correlative system of the Five Agents; and yellow, one of the basic colours of the medium on which such symbols are usually drawn.

Like our previous two specimens, this “Great Peace Symbol” was intended for internal use. Its illustration is followed by an “invocation” to be uttered by the officiating Taoist as he or she “absorbs the symbol” (“Fufu zhou” 服符呪). Composed in rhymed, four-syllable verse, this invocation probably served as model for the “Imperious Invocation” (“Chi zhou”) from the preceding source, translated above.Footnote 88 Concise guidelines close this invocation:

呪畢, 叩齒三通, 以符安口内方, 存炁吞之.

The invocation being completed, strike [your] teeth together three times, place the symbol inside [your] mouth, hold [your] breath, and swallow it.Footnote 89

The chapter then turns to the Heart Petition – which we have met in the preceding two sources – a bureaucratic document the priest addresses to his or her heart god with the express order to messenger it to the upper deities. In reduced-size characters the detailed guidelines to ingest a Heart Petition (to be drawn using a blank form scrupulously reproduced in the text) are given, together with a “Great Peace Symbol”: these are basically identical to those appearing in the source of the fourth specimen and, again, involve the visualization and inhalation of coloured pneumata.Footnote 90 The major difference is that here, the sole symbol to be ingested, rather than three distinct symbols, is the “Great Peace Symbol”. More importantly, immediately following the ingestion of the Great Peace Symbol comes the swallowing of the petition itself, previously reduced to ashes (hui 灰):

其服心章, 以章灰入口, 一依符訣.

As regards the absorption of the Heart Petition, enter the ashes of the petition into [your] mouth and comply exactly with the instructions [for absorbing] the symbol.Footnote 91

These guidelines lead to a “Spell for the Transmission of the Absorbed Petition to the Gods” (“Fuzhang tongshen zhu” 服章通神祝), which must have served as model for the “Invocation to the Lord of Cinnabar Prime” (“Danyuan jun zhou” 丹元君呪) from the source of the third specimen, called in the source of the fourth specimen (translated above) “Invocation for the Transmission of the Petition” (“Tongzhang zhou” 通章呪).Footnote 92 The text then moves on to describe further ritual segments of this layered liturgy, but our “Great Peace Symbol” does not appear again.

Epilogue

Due to its peculiar focus and its chronological extension, this survey has inherent limitations. It is not possible to state with utmost certainty whether these different symbols were ever used or not, and assuming they were, by whom and with which result. Also impossible to prove is that the various Great Peace Symbols on the one hand, and some of the practices advocated in the Great Peace Scripture (Taiping jing 太平經) on the other hand, reflect a single tradition. The hypothesis is all the more tempting since Ge Hong lists a Great Peace Scripture in the inventory of his master Zheng Yin's library.Footnote 93 Indeed, the ritual guidelines included in the sources of the last three specimens echo the visualization of colours in one's corporeal space, as described in a late product of the Great Peace tradition, the Great Peace Scripture: Secret Directives of the Saintly Lord (Taiping jing shengjun mizhi 太平經聖君祕旨), a short text based on ancient material but compiled in the late Tang dynasty or soon after (CT 1102).Footnote 94 In that particular context as well as in later internalized liturgy, however, Great Peace denotes a personal experience, a state of grace only vaguely reminiscent of the collective, eschatological aspiration it used to encapsulate in the early Great Peace tradition.Footnote 95

And yet, such practices already existed in early medieval Taoist communities. Texts, of which comparatively old versions subsist, such as the well-known Scripture of the Yellow Court (Huangting jing 黃庭經), explain how to visualize corporeal entities organized and depicted in accordance with the correlative framework of the Five Agents.Footnote 96 Furthermore, there is evidence – including in the textual sources of the last three specimens – that some symbols, once integrated into elaborate and at least partly internalized liturgies, did retain a basic talismanic function, albeit accessory in many cases. And of course, the rite of divine petitioning itself – a borrowing, as we have seen, from imperial bureaucratic procedures, and attested in Taoism since the early medieval era – remained prominent throughout the history of Taoism.Footnote 97 Thus did early forms of religiosity adapt to historical changes.

Can we prove the existence of any historical relationship between the first two specimens, quite dissimilar, and the three later ones, which are evidently variants of the same ritual tool? To this point, Mollier's treatment of Buddhist and Taoist symbols provides us with a crucial source, the Marvellous Scripture for Prolonging Life and Adding to the Account, Spoken by the Most High Lord Lao (Taishang Laojun shuo changsheng yisuan miaojing 太上老君説長生益筭妙經), a late-seventh-century Taoist text (CT 650).Footnote 98 The purpose of this text is to offer the adept the protection and help of life-governing gods, in particular the generals of the Six Jia 六甲, in order to extend his or her lifespan.Footnote 99 To this effect, the text presents a series of fifteen symbols, beginning with a “Heart-opening symbol” (“Kaixin fu” 開心符) closely resembling the last three specimens of our survey (see Figure 6). Of course, a third dot would seem to be missing on the left-side vertical stroke, three stars of the Northern Dipper are not dotted on the right-side vertical stroke, and the central area includes a supernumerary “山” as well as the item “甲”, the latter naturally representing the Six Jia.Footnote 100 These discrepancies notwithstanding, in all likeliness this “Heart-Opening Symbol” is the prototype of our last three “Great Peace Symbols”.

Figure 6. “Heart-Opening Symbol” (CT 650, 6a)

The first specimen known to Ge Hong was a talisman properly speaking, a portable device endowed with specific powers, almost like an amulet. Unlike its later morphotypes, but much like the symbols dealt with by Ge Hong, the “Heart-Opening Symbol” above was to be carried by the adept and therefore had an unquestionable talismanic function. But to that function a ritual dimension had already been added: the efficiency of the symbol depended on the adept reciting the scripture and worshipping it.Footnote 101 The last three specimens, with their standardized morphology, were certainly designed by adapting the general morphology and – in the fourth and fifth cases – borrowing the name of that earlier “Heart-Opening Symbol”. This borrowing may have been prompted by the lasting popularity the “Divine symbols for adding to the account” seem to have enjoyed.Footnote 102 But other sources may have been used as well – other “Heart-Opening Symbols” such as those preserved in the Taoist Canon, and which, though morphologically unrelated to our specimens, were also designed for absorption (fu 服) by swallowing (tun 吞).Footnote 103 No wonder our second specimen was ignored by the designers of these last three “Great Peace Symbols”, if it was not simply unknown to them: its purpose, unlike that expected from common talismans, was far too macrocosmic to satisfy individual practitioners who were looking for personal devices they would combine into ritual sessions in the framework of layered liturgical programmes.