Introduction

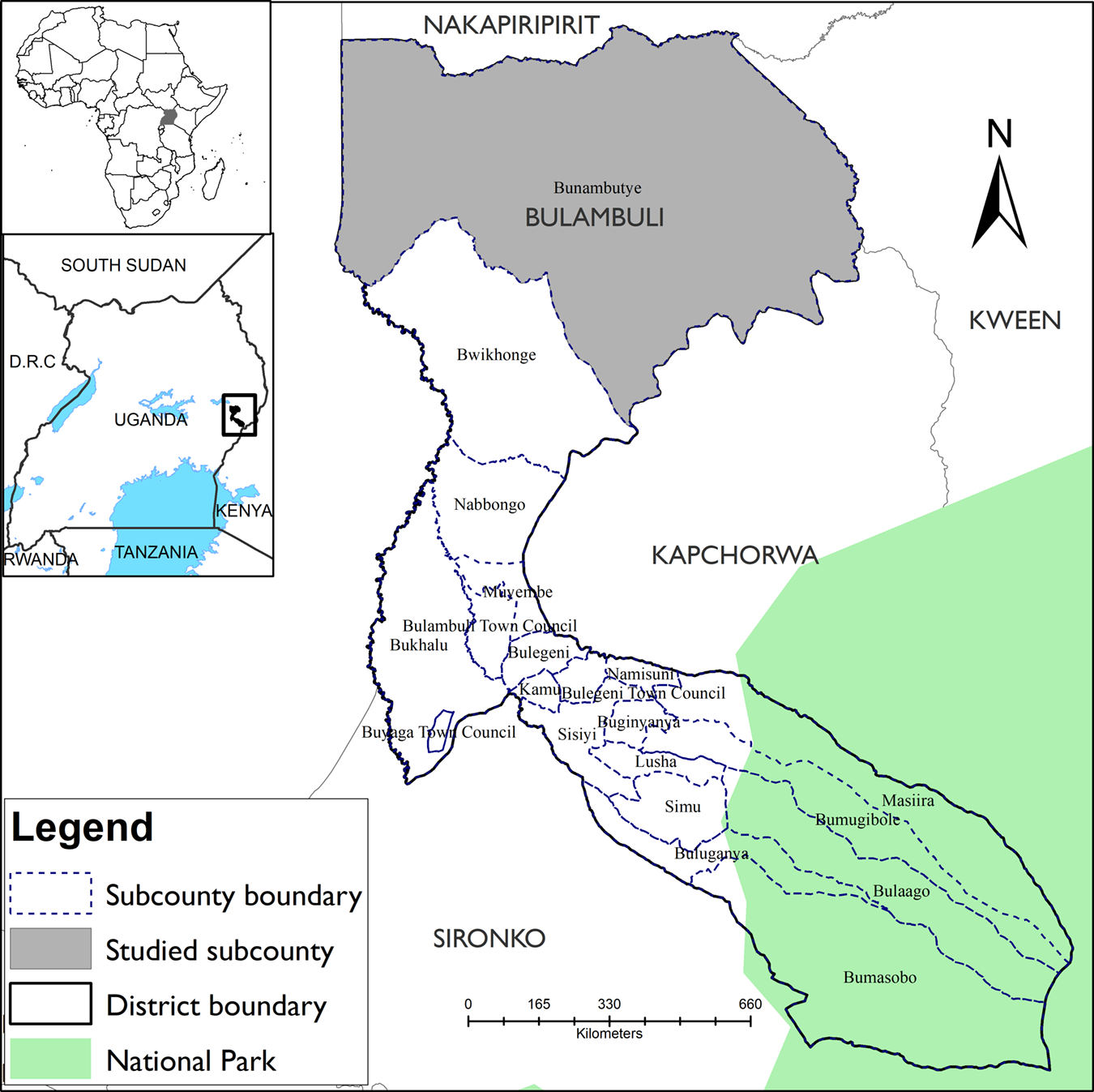

Cattle rustling has been known to benefit from and promote arms proliferation, as may be seen in Uganda and Kenya, where the proliferation of small arms has intensified conflicts among the Karimojong and their pastoralist neighbors, namely the Turkana and Pokot of Kenya (Mkutu Reference Mkutu2007, Reference Mkutu2008; Mirzeler & Young Reference Mustafa and Young2000). Additionally, scholars have associated cattle rustling with inter-communal conflicts (Dyson-Hudson Reference Dyson-Hudson1966), terrorism, as revealed in the case of Boko Haram in Nigeria (Okoli Reference Okoli2019), and other organized crimes such as kidnapping (Olaniyan & Yahaya Reference Olaniyan and Yahaya2016) and the commercialization of stolen animals (Eaton Reference Eaton2010). What has not yet been explored in the literature is the ways in which cattle rustling has engendered land conflicts. In particular, scholars have not examined the contexts in which cattle rustling has created land conflicts as a result of the chronic insecurity caused by the accompanying violence. This article seeks to fill in this lacuna by exploring the ways in which cattle rustling activities by some Karimojong men of northeastern Uganda have displaced residents and subsequently fueled land conflicts in eastern Uganda. It focuses in particular on one case in Bunambutye sub-county in Bulambuli district. Bordered by Nakapiripirit district to the north, Kapchorwa and Kween to the east, Sironko to the south, and Bukedea to the west, Bulambuli District, and Bunambutye sub-county in particular, became a hotbed of multiple land wrangles during the first two decades of the twenty-first century. With an area of 126 square miles (67,400 acres) of land, Bunambutye is one of the largest but least populated sub-counties in the eastern region. It also has the lowest provision of social infrastructure including roads, schools, water, and health. Residents of Bunambutye are primarily Babukusu Bagisu and Sabiny. (See map, Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map showing location of Bulambuli District

In September 2008, some complainants from Bunambutye reported their land disputes to President Museveni who, in turn, instructed the Minister of Internal Affairs to inquire into the matter. In April 2010, the Ministry convened the Bunambutye Land Verification Committee (BLVC) to investigate the problem. The committee established that the most disputed land included plots 100, 112, 113, and 114, constituting 53.5 square miles (34,317 acres), which had issues of questionable ownership arising from irregular acquisition, survey, sale, and alienation. The BLVC recommended that the fraudulently acquired land titles to the above plots be cancelled while those to plots 86, 87, and 94 be further scrutinized.Footnote 1 Unfortunately, the latter titles were not reviewed in a timely enough manner to prevent the situation from escalating further. There were also incidents of forgery, including one in which Mbale Municipality authorities connived with local leaders in Bunambutye to forge the names of purported owners and sold the land without consulting the true owners, and another in which residents accused the district leaders of leasing 14.5 square miles (9,250 acres) of land to an investment company without consulting the owners.

This article focuses on the dispute over Plot 94 in Bukiyabi village in Bunambutye. Measuring approximately 0.42 square miles (270 acres), Plot 94 belonged to the late Peter Wanambuko who, along with his family, fled to Kenya in 1980 following the violence that was associated with Karimojong cattle rustling in the sub-district. Those involved in the dispute included Wanambuko’s family, who claimed customary rights to the land, and two new claimants, namely George Ochwo and Lt. Col. Kitts, a brother to one of Wanambuko’s widows. Members of Wanambuko’s immediate family claim that, when they fled, Wanambuko entrusted his more than 200 acres of land to his brother-in-law, Kitts, who lived in the nearby town of Mbale. However, when the family returned to their land in the mid-2000s, they confronted a new claimant named Ochwo, who possessed a title deed to the land. While the returning family accused Ochwo of irregularly acquiring their land, Ochwo accused them of criminal trespass over his land which he purportedly had bought from Kitts. The complainants maintained that Wanambuko never sold the land to Kitts, but merely entrusted it to him. The dispute over Plot 94 exemplifies many of the problems surrounding land tenure, especially in cases arising from the displacement of the population.

This article examines this controversy and traces the genesis of the competing claims. By unleashing violence and insecurity in Bunambutye since the 1960s, Karimojong cattle rustling activities not only separated the residents from their land but also provided space for opportunistic individuals to engage in fraudulent and irregular land transactions. Reflecting on this, the article provides a nexus between cattle rustling, land conflicts, and attempts at building peace. It shows that by failing to end the Karimojong cattle rustling and subsequent land conflicts in a timely manner, the Ugandan government failed to build peace and protect the residents of Bunambutye. Although the National Resistance Movement under President Yoweri Museveni had created a semblance of peace in the region since the mid-2000s, it failed to address the emerging land disputes in a timely manner, leaving many customary owners dispossessed.

The narratives of the returning residents raise questions about the meaning of and official attempts at peacebuilding. Whereas conventional definitions of peace refer to an end to war and establishment of civil order, Johan Galtung (Reference Galtung1976) calls for an extended concept of peace, one which includes both a reduction in direct violence and action to fight social injustice. Although the violence that displaced the Bunambutye residents in 1980 had ended, there was no peace for them, owing to the threats of land dispossession. This conforms to Patricia Daley’s (Reference Daley2006) observation that peace is a process and not merely an abrupt end to conflict. I discuss the role of arbitration with an impartial mediator engaging the disputants (Belloni Reference Belloni2012) and the implementation of the recommendations of the various commissions of inquiry that have investigated the different disputes over land in Bunambutye. Involving returning residents and addressing their grievances is critical to establishing lasting peace (Karbo Reference Karbo and Francis2008; Murithi Reference Murithi and Francis2008).

Research for this article drew on both oral and written sources. Oral interviews in Bunambutye were conducted in August and September 2015; they largely focused on key informants and Focused Group Discussions (FDGs) with aggrieved returning residents, including members of Wanambuko’s family. The study employed both purposive and snowballing sampling techniques and, in total, twenty individual interviews and three FDGs, each consisting of between six and eight people, were conducted. In-depth interviews lasting about two hours were conducted in Lugisu and Lubukusu with members of the aggrieved family. The two research assistants and I are fluent in both languages and translated the interviews ourselves.

I use archival documents from the National Records Centre and Archives (NRCA) in Kampala, the Africana section at Makerere University Library, and the Parliament of Uganda Department of Library and Research (PUDLR). Research at the NRCA yielded colonial and postcolonial district reports relating to Karimojong cattle rustling in Bunambutye dating from the 1960s to the 1990s. Colonial reports and ethnographies from the Africana section yielded information on land tenure in the Bugisu region dating back to the 1940s. The PUDLR archives provided detailed correspondence on the Bunambutye land conflicts, including letters of complaint from the returning residents to the president and the prime minister, letters from the local authorities and Bulambuli District officials to the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), reports from the Ministry of Lands and Urban Planning, and reports by the Parliamentary Committee and commission of inquiry on Bunambutye. These presented the claims of the different actors who contested ownership of the disputed land. I also used different media, including local newspapers dating been 1990 and 2020, and watched YouTube recordings by NTV (TV channel in Uganda) of the 2019 Land Commission hearing in Bunambutye.

Karimojong Cattle Rustling and Displacement in Bunambutye

The controversy over plot 94 in particular and the roots of several other contemporary land conflicts in Bunambutye in general stretch back to the period of increasing violence arising from the Karimojong cattle rustling activities in the region over the course of the twentieth century. As Sara Berry (Reference Berry2002:640) emphasizes, locating land conflicts in “specific historical contexts taking account of the way multiple interests and categories of people come into play, and impinge on one another, as people seek to acquire, defend, and exercise claims on land” is vital because it provides a deeper understanding of the conflict and the forces that shape it.

Collectively known as the Ateker, the Karimojong of Kotido, Moroto, and Nakapiripirit districts in northeastern Uganda inhabit one of the most inhospitable ecozones in Africa. They engage in violent cattle rustling because of a combination of factors, including environmental variations, livestock disease, and lack of state security (Bevan Reference Bevan2008). The Karimojong have struggled to retain their pastoralist orientation because it ensures their survival amid the harsh ecological realities. They regard cattle rustling as a mechanism of resolving competition for scarce resources and redistribution of livestock after a catastrophe (Gray Reference Gray2004). Over the course of the twentieth century, the Karimojong engaged in cattle rustling with their pastoralist neighbors, including the Turkana and Pokot in Kenya (Knighton Reference Knighton2010) and the Iteso in Uganda (Närman Reference Närman2003). Believing that cattle-raiding was the result of primitivity and backwardness, British colonial authorities in Uganda restricted Karimojong movements and alienated them from huge tracts of grazing land in an attempt to prevent further raiding. The droughts of 1943 and the early 1950s eroded inter-communal relations, as increasing “competition for resources in contested zones finally inaugurated a renewal of raiding along the Pokot-Pian border in the early 1950s” and across northern Ugandan and Kenya in the 1960s (Gray Reference Gray2004:409).

In an attempt to stamp out this pastoral system which was regarded as inherently prone to conflict, and informed by the Bataringaya Report (GOU 1961), postcolonial governments in Uganda employed a strategy of disarmament. This had disastrous consequences (Knighton Reference Knighton2010), including internal displacement, especially of women and children, as they out-migrated from Karamoja to Kampala to escape the violence associated with the government operations (Sundal Reference Sundal2010). The Bataringaya Report recommended punitive actions, including deploying the army in a campaign to punish the raiders and confiscate their weapons. President Milton Obote’s punitive action in the late 1960s did not, however, deter Karimojong cattle rustling activities, as the area continued to suffer attacks. In April 1968, Bugisu District authorities reported that “Karamojong are still active in invading inhabitants of Bunambutye” and that the police were “doing all means to lessen a hostile entrance.”Footnote 2 With further droughts and livestock epidemics in the 1960s, together with the government policy of confiscating livestock, Karimojong cattle rustling intensified, resulting in violence between the Karimojong and their neighbors through the 1970s and 1980s (Gray Reference Gray2004). During this period, Bunambutye was not spared, as one chief reported in 1975:

This office received much correspondence from the Gombolola chief Bunambutye of Karamojong people who have started again to raid cattle from Bunambutye and on top of that they killed some cattle owners and their food crops were damaged seriously. This was reported to high authorities for action. But I suggest that there should be a joint meeting at Ngenge being the centre of three districts – Sebei, Bugisu and south Karamojo [sic] to look into this matter.Footnote 3

In contrast with the 1960s, when local authorities called for police protection, in 1975 they also sought to employ dialogue involving both the perpetrators and victims as a mechanism of peacebuilding. But this approach also failed. During a public meeting held at Bunambutye sub-county headquarters on August 16, 1976, the saza chief called for “Erecting [a] police post at Katta Bunambutye in order to block entrance of the Karamojong cattle raiders.”Footnote 4 Those present at the meeting resolved that each tax payer should contribute Uganda Shillings 50/= to support the initiative.Footnote 5

In spite of such efforts, the violence escalated in the late 1970s and into the 1980s. This was partly because of the upsurge in arms proliferation through illicit trade networks throughout East Africa, which complicated and intensified the conflicts among the pastoralists (Mkutu Reference Mkutu2008; O’Connor Reference O’Connor, Hansen and Twaddle1988). The overthrow of the Amin regime by the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) and the Tanzanian People’s Defence Force (TPDF) in 1979 increased the proliferation of arms in Karamoja, resulting in unprecedented violence in the region (Meyerson Reference Meyerson2019; Gray Reference Gray2004). In the context of the disorder following Amin’s downfall, and amid the famine of 1979 in Karamoja as well as the arms proliferation, Karimojong men intensified raids on the neighboring districts of northeastern Uganda (Mkutu Reference Mkutu2008; Gray Reference Gray2004; Närman Reference Närman2003), resulting in massive displacement in the Teso and Acholi regions during the late 1980s and early 1990s (Kandel Reference Kandel2017; Sjögren Reference Sjögren2014).

The attacks on Bunambutye in the late 1970s forced many residents to flee. One man who returned in 2012 narrated: “Since 1940 we had lived here peacefully except for attacks by the Karamojong … [who] used to attack us with spears and for us we had bows and arrows.” He further explained that in the previous years, the Karimojong “would attack us at night but now [after acquiring guns] they started attacking during broad daylight. They chased us from here. They stole property and killed people. They chased us from our land.”Footnote 6 Reflecting on the period before and during the violence of 1979, one of Wanambuko’s widows recounted in an interview in 2015:

We lived here since I got married. I came here when I was still a young girl. My firstborn was born here. Even my last born. Until the children got over in the womb. We ran away to escape insecurity from this place in May 1979. We ran away from the Karimojong. We left everything behind. We left here two tractors. A ford lorry also remained here. We left naked.Footnote 7

This narrative reveals the widow’s historical attachment to the land under dispute and the agony arising from the cattle rustling violence.

When Museveni assumed power in 1986, his government was confronted with the insecurity arising from cattle rustling in eastern Uganda, including the violence in Bunambutye. On visiting the area in 1989, Museveni promised to establish a barracks at Kata to serve as a barricade against the Karimojong rustlers. Knowingly or unknowingly, Museveni took up the 1976 proposal by local chiefs for construction of a barracks in Bunambutye. Unfortunately, Museveni’s promise was not immediately fulfilled. In 1991 during a meeting with the Mbale District Council, under whose jurisdiction Bunambutye fell at the time, one government deputy minister acknowledged the government failure in restoring peace and thanked the District Council “for reminding government about shortfalls” especially the issue of insecurity in Bulambuli county.Footnote 8 Nonetheless, the deputy minister believed that, compared to 1986, the security situation in Bulambuli had improved by 1991. In response, one councilor observed that although the number of raiders had reduced, they had become more dangerous, as they had shot five people dead within a period of two months. Noting that the people of Bunambutye were capable of training up to five hundred Local Defense Units, the councilor appealed to the government to provide them with guns to curb the situation.Footnote 9 By the early 1990s, the few residents remaining in Bunambutye were desperate and ready to confront the Karimojong, but they needed equally sophisticated weapons to do so. The bows and arrows that they had used earlier in the twentieth century could not match the sophisticated arms and ammunition of the raiders.

In 1998, in spite of ongoing insecurity arising from the Karimojong raiders, some of the displaced persons from the 1980s begun to return and resettle on their land in Bulambuli. In April 1998, however, Karimojong rustlers killed seven people and took several head of cattle (The Monitor 1998). Two months later, they struck again, killing eight people, abducting women, taking several head of cattle, and destroying property, including the burning of homes. Faced with this insecurity, the returning residents appealed to the government to establish a military unit at the border separating Karamoja from Bulambuli (Mututa Reference Mututa1998). However, by 2000, there was no progress toward this action, despite Museveni’s 1989 promise. Instead, with a forthcoming referendum on multiparty governance, Museveni announced that “a district-wide disarmament campaign would be launched in Karamoja in July” of 2000 (Gray Reference Gray2004:412). Like Obote, Museveni took punitive action against the Karimojong in order to disarm them (Muhereza Reference Muhereza2018). The disarmament operation began in 2002, resulting in massive displacement as Karimojong women and children fled to the streets of Kampala and other towns to escape the violence and find alternative means of survival (Sundal Reference Sundal2010; Knighton Reference Knighton2010).

In 2006, faced once more with an upcoming presidential election, Museveni’s government fulfilled its promise and established a military barracks at Kata on Plots 86 and 87, both adjacent to Plot 94 in Bulambuli. Records indicate that the Uganda People’s Defense Forces (UPDF) bought Plots 86 and 87 from Kitts, who “claimed to have bought the land in question from the late Peter Wanambuko, who had taken refuge in Kenya due to the insecurity caused by the Karimojong cattle raiders in Bunambutye at the time.”Footnote 10 The report details that Kitts paid for the land in 1980 through two of the deceased’s wives—one of them since deceased and the other being Kitts’ sister—who took the money to their husband in Kenya. Responding to complaints by Wanambuko’s family in 2014, the Chairman of Local Council V explained that after buying the land from Wanambuko, Kitts surveyed and subdivided it into plots 85, 86, and 87. He sold plots 86 and 87 to the UPDF, and this subsequently “brought a great deal of security because of the presence of soldiers.”Footnote 11 The Chairman applauded the government for ending the insecurity associated with cattle rustling and was not sympathetic toward the aggrieved family.

In what seems to be obvious support for the accused, the Chairman narrated that Kitts subdivided the remaining Plot (85), with part of it becoming Plot 94 that he then sold to Uganda Organic Plantation Ltd, an Indian-owned firm. In 2006, the firm sold the plot “to Mr. Ochwo George Wilson who is the current owner and had Title Deed with a Lease of 44 Years.”Footnote 12 In their response to the Chairman, one of Wanambuko’s widows and his children refuted the claim that Wanambuko had sold the land in question to Kitts.Footnote 13 Indeed, Kitts had no proof of purchase. Yet the original land title of Plot 94 was in his name before Kitts transferred it to Uganda Organic Plantation.Footnote 14 How was the title processed in his name when he had no proof of ownership? This suggests an irregular transaction at some point. Furthermore, by outrightly supporting the new claimants, the Chairman of the district-level Local Council Five (hereafter LC V) confirmed early concerns by the BLVC that political leaders in Bulambuli were ignoring the plight of the complainants who had lost access to their land.Footnote 15

“We Have Nowhere to Go”: Tenure Insecurity for Returning Residents

Scholarship on land-related conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa has long emphasized the increasing significance of land as a contested resource in the changing economies of both the colonial and postcolonial periods. International scholars have offered multiple interpretations of the conflicts, including increasing population (Downs & Reyna Reference Downs and Reyna1988), social differentiation and class formation (Peters Reference Peters2013), the rise in social transformations and inequality (Peters Reference Peters2004), land reforms (Berry Reference Berry1993), and large-scale land expropriation—or “land grabbing” (Cotula Reference Cotula2012; Peters Reference Peters2004; Sjögren Reference Sjögren2014). Research in Uganda provides similar explanations for the conflicts, including social differentiation (Kandel Reference Kandel2017), the changing value of land and systems in land governance (Leonardi & Santschi Reference Leonardi and Santschi2016), land grabbing (Sjögren Reference Sjögren2014), appropriation of land as a political resource (Medard & Golaz Reference Medard and Golaz2013), competition over the access and use of natural resources such as grazing lands and water resources, and disputes over territorial land and boundary demarcations (Sjogren Reference Sjögren2014; Khanakwa Reference Khanakwa2012).

In an African Studies Review special forum on land (2017), the authors examined the connection between land acquisition and political authority (Berry Reference Berry2017) and the ways in which conflicts and displacement have shaped land disputes in Africa. Lotte Meinert et al. (Reference Meinert, Willerslev and Seebach2017) and Susan Whyte and Esther Acio (Reference Whyte and Acio2017) investigated how land disputes in post-conflict northern Uganda led to generational and intergenerational tensions. During the war, the residents were forced out of their homes into camps for Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs); on returning home after the war in 2008, they could not access their land because the social relations through which young men and women could acquire land among the Acholi had been disrupted. As a result, some young Acholi men and women devised new strategies to access land, including showing respect and humility to elders and renting land (Whyte & Acio Reference Whyte and Acio2017). Others adopted the use of cemented graves and cement pillars as proof of ownership over disputed land. Cemented graves and cement pillars came to constitute important markers of belonging and evidence of ancestor presence on the land (Meinert et al. Reference Meinert, Willerslev and Seebach2017). Other studies on northern Uganda (Sjögren Reference Sjögren2014) and eastern Uganda (Kandel Reference Kandel2017) have demonstrated how violence in those regions led to massive displacement and separation of people from their land, subsequently making the land vulnerable to opportunistic actors.

In the period from 2012 to 2014, as more people returned to claim their land in Bunambutye, they encountered new claimants (Mafabi Reference Mafabi2014). In a letter to the President, dated July 27, 2013, members of Wanambuko’s family decried, “We do hereby complain and request your honorable office to help and save us and [our] young sisters and brothers from Mr. George Ocho [sic] and Retired Lt. Canal [sic] Kits Lawrence for they have encroached on our land which our late father left for us.” They narrated that their father “bought the land in question in 1954 from Mr. Muhunga Mamera at four cows and from Maikairi Yakobo at 4 cows and another at Bulugaya, he bought it at 1,100 shillings Sabuni Kangabasi and from Elukana Wopata at 8 cows.”Footnote 16 The family, they noted, had lived on that land until 1980 when they fled to Kenya, where Wanambuko later died in 1994.

In another letter to the Inspector General of Government (IGG), dated October 20, 2014, Moses Wanambuko (one of the orphans) further narrated: “as peace was restored in the area through the Karamoja disarmament process and eventual deployment of the Anti-stock theft unit (ASITU) coupled with the establishment of Kata Military Barracks adjacent to our plot, We found such effort by government helpful and appropriate for us to return and work on our land.”Footnote 17 When they returned in 2013, they reported to the local authorities before they could settle on their land. In 2015 one family member narrated:

When we arrived here we went to the R[esident] D[istrict] C[ommissioner] …. He asked if this is our place. I said yes. He asked for details and I said Bukiyabi Village, Bumufuni Parish, Bunambutye sub-county. And we came and we reported at chairman LC1. They welcomed us and … showed us our land. […] There was nothing on the land, not even a house … So we started construction and raised our houses.Footnote 18

Moses’s letter to the IGG reinforces this personal narrative detailing how they presented themselves before the relevant authorities for clearance. He explains: “we were introduced to” the local council authorities and “were cleared as true owners and were recommended to proceed to settle on our land.”Footnote 19 The family members went ahead and built houses and began cultivating the land.

However, their hopes were shattered when, as they reported, “on the 15th July 2013 one of us Mr. Salim Wafula Wanambuko was arrested by George Wilson Ocho who claimed that he bought the land from Lt. C. Kitisi [Kitts].”Footnote 20 In an interview in 2015, one family member recalled: “After about three months they confronted us. The parish-level L[ocal] C[ouncil] III came and told us that we were trespassing on some people’s land.” Shocked, the returning resident responded: “Trespassing? Trespassing on whose land?” The LC III said that the land belonged to Ochwo.Footnote 21 The LC III Chairman delivered a letter referenced “Criminal TRESPASS ON LAND OF MR. OCHWO GORGE [sic] WILSON on plot 94” to the family.Footnote 22 Ochwo had reported a case of criminal trespass against John Wanambuko at the Cheptui police station.Footnote 23 John was arrested and later released on bond, but he was told to report routinely to the police. On July 15, 2013, he was accompanied by some family members to report at the district police headquarters. While they were there, one family member narrated: “Mr. Ochwo George Wilson, Lt. Col. Lawrence Kitts escorted by military men drove to our home and demolished all the three family houses in our land and destroyed all personal properties.” The family “sought for help from relevant authorities in the district but to no avail.”Footnote 24

Demolition of property is characteristic of land evictions in Uganda, whether legal or not; this tactic is usually used by powerful individuals to intimidate the weak. Though devastated by the violence, the family did not give up. They appealed to the president for help. In response, the president’s Principal Private Secretary directed the RDC Bulambuli to investigate the matter and ensure that the family be settled and protected. After investigations, on August 19, 2013, “the RDC, Nabende Wamoto directed us to occupy our land.”Footnote 25 In his report on the matter, Wamoto recommended prosecution of Kitts and cancelation of the title.Footnote 26 However, in total disregard of the Wamoto’s directive, on August 24, 2013, Ochwo was “heavily guarded by the military [who] erected a barbed wire fence on our land.” Further efforts to get local authorities in the village and district to intervene were futile.Footnote 27

Months later, in a letter to the Wanambuko family in 2014, the Chairman LC V asserted that “Mr. Ochwo is the rightful owner of the said land because the Land Title Deed has an undeniable history down from 1980 which was sold by a willing owner, your late father and a willing buyer.”Footnote 28 The chairman openly defended the title deed holder and asserted that Kitts had bought the land from the deceased in 1980, although there was no evidence of any such purchase. Furthermore, he warned the family against criminal trespass on Ochwo’s land. In so doing, the chairman overturned the earlier decision of his deputy and regretted that the decision had been made: “The Office of the Vice Chairman LC V Bulambuli District made grave error by writing to the [village-level] L[ocal] C[ouncil] I Chairman Bukyabi Village (dated 24-03-2014) requesting that your family should be resettled on the land of Mr. Ochwo George Wilson that your parents willingly sold far back in 1980.” He further highlighted that “The office of the Vice Chairman LC V does not have legal competence to resettle people.”Footnote 29 To underscore his point, the chairman referred to President Museveni’s assertion that “that RDCs (and by extension the LCs at whatever level) should not handle land cases but submit reports to relevant authorities.” Museveni had issued a statement to that effect while addressing RDCs in Kyankwanzi (Baguma Reference Baguma2014:6). Drawing on what he called “wisdom in the advise [sic] of His Excellency,” the chairman stressed that “The public should not be deceived that the RDCs or LCs have the legal competence to settle or resettle people.”Footnote 30

Paradoxically, the same LC V chairman was using his office to privilege Ochwo as a bona fide owner of the disputed land simply because he had a title deed. He issued the complainants an ultimatum “to vacate Mr. Ochwo’s land in seven days” or face forceful eviction by “Regional Police Commander Elgon zone and DPC Bulambuli… so that the rightful owner of the land may freely continue to develop it.”Footnote 31 This was selective application of the law and presidential directive. Moreover, in a letter to the OPM, the chairman of the Land Verification Committee of Bunambutye shamelessly asserted that the committee had properly verified that the disputed land had “no encumbrances” as the new claimants including Ochwo had agreements of sale. In his view, the returning residents “who are claiming ownership of the above plot have no land there.”Footnote 32 Thus, he gave the OPM a go-ahead to pay Ochwo and acquire the land to resettle survivors of the 2010 Bududa landslides. The chairman’s submission was an outright lie, because as mentioned in the introduction, as early as 2010 members of BLVC had recommended further review of the title to Plot 94.Footnote 33

The submissions of the two chairpersons confirm the fears of critics of land reform. Contrary to advocates of reform who argue that possession of title deeds as proof of ownership would secure African’s land and reduce conflicts (De Soto Reference De Soto2003; World Bank 2003), critics point out that the land tenure reforms aggravated land conflicts through new forms of exclusion that promote social injustice and inequity (Shipton Reference Shipton2009; Moyo Reference Moyo2008; Manji Reference Manji2006). Evidence from across sub-Saharan Africa reveals that land registration and titling, as well as proposed mechanisms of land related conflict resolution, created more conflicts and deprived the poor of tenure security (Kanyinga & Lumumba Reference Kanyinga and Lumumba2003) and, as in the case of Tanzania, resulted in further displacement and marginalization (Shivji Reference Shivji1998).

The process of land tenure reform in Uganda began in the 1990s, following the review of the country’s constitution. Article 237 of the 1995 Ugandan constitution stipulated that the parliament enact a new land law within two years of its first sitting. Accordingly, in 1998 the Land Act was passed, and shortly thereafter, “it became evident that there would be major difficulties involved in implementing the new law” (Manji Reference Manji2006:71). During the deliberations of the Land Bill, several issues were raised. Mahmood Mamdani warned that the bill “ignored the weakest and most vulnerable sections of society, the undocumented tenants and spouses.” Mamdani further criticized the bill for its emphasis on defining a “tenant by documentation rather than by land relations with his landlord” (Mwenda Reference Mwenda1998). The act altered the relationship between holders of customary tenure and the land. It meant that once an individual acquired a title to customary land, that person could easily exclude those with customary rights to the same land and trade the land as property by freely selling it off if they so wished. Untitled and unoccupied land under customary tenure was at particularly high risk of being usurped under the new legislation. The history of and contestations over Plot 94 confirm that these fears were justified.

Earlier, in April 2014, in a desperate effort to regain ownership of the land, Moses had issued a caveat “forbidding registration of any change in proprietorship or dealing with the estate Plot 94.”Footnote 34 He lamented that although he had reported the illegal surveying and parceling of the land to higher authorities, no action had been taken against the new claimants. He wrote, “on 20th January 2014, I saw some people who introduced themselves as officers from the office of the Prime Minister come on our clan land,” and they “told me that they were inspecting the land with a view of buying the same to resettle the people from Bududa.” In March 2010, landslides had displaced people in the nearby Bududa district, and the Uganda government had committed to acquiring land within the Bugisu region to settle the landslide survivors. Bunambutye was earmarked for this purpose because of the availability of unoccupied land. Moses feared that “there is a high likelihood that the above land will be sold off very soon including our 200 acres which were unlawfully surveyed and included therein.”Footnote 35 In spite of the caveat he had filed, on July 20, 2013, “we received information that Mr. Ochwo George had submitted our land as in part (sic) of Plot 94, bidding to offer it for sale to the office of the Prime Minister to resettle Bududa Landslide victims.”Footnote 36 Amid the obvious contestation, as already noted, the chairman of the Land Verification Committee of Bunambutye claimed that plot 94 had no encumbrances.

In total disregard of pleas from the affected communities, in September 2014, Wabudi, then RDC of Bulambuli, accused returning residents of being imposters. In a letter to the Minister of Disaster Preparedness, Wabudi said that although he was aware of the “numerous claims that the Political Leaders in the District have grabbed or are in the process of grabbing people’s Land,” his investigations had established that “Those people who are making false claims that they are customary tenants on this Land are not even settled on this Land.” Wabudi was bitter because the returning residents, as he stated: “had earlier on made me endorse Documents which they wrote to His Excellency the President of Uganda sometime back reporting that they had settlements on this Land when in actual fact, they did not own any settlement.”Footnote 37 In his view, the customary claimants had no basis to claim the land because they had neither settled nor owned any settlements on the land in question. This claim was unfortunate because, as reported on October 6, 2014, the houses of the complainants “were burnt down with petrol by Mr. Ochwo’s son escorted by the O.C Anti-Stock Theft Unit of Bunambutye.”Footnote 38 Moses reported the incident to the police, but the officer declined to record the statement. Instead, the Regional Police Commander notified him on October 16, 2014, that members of his family had been summoned to appear in court for matters relating to trespass.

The RDC ignored the family’s historical legitimacy and relationship to the land, and instead warned that “these continued speculation by these claimants in expectation of benefiting from on-going Government acquisition of this Land is likely to precipitate problems in the District since all Land owners with proper Titles are being threatened by the impostors who are exploring all avenues to frustrate the Government Programme to acquire Land for Resettlement.” The RDC’s letter reveals the vulnerability of returning customary land owners and how local level decisions might be overturned by powerful individuals in favor of elites. In defending the title holders, the RDC abused his office while claiming to support the government resettlement program. He concluded, “unless there are any reasons to the contrary, there is no reason why the legitimate owners of the Land with Titles should be frustrated from selling their land to Government.”Footnote 39 The post-cattle rustling context had provided new opportunities for accumulation (Cramer & Richards Reference Cramer and Richards2011) and, because of the interest of government in the disputed land as well as the interests of elite land dealers, the customary tenants were dismissed as imposters.

In 2015, one of the returning residents of Bunambutye recalled the times in the past when chiefs and elders resolved land disputes. He related that, “for our grandfathers, there were elderly men who would be invited to resolve conflicts emanating from boundaries. There used to be a mutongole chief and elders. We used to call him mutala chief who was the leader of the village.” The mutala chief “would call upon elders from both sides of the conflicting parties” and “give either person a chance to explain their side of the story. On the basis of the discussion, the chief and elders would resolve the conflict.”Footnote 40 In contrast, attempts at resolving land disputes by the beginning of the twenty-first century were drastically different, in part because of titling and the increasing value of and demand for land by different individuals, investment companies, and government agencies. Demand peaked in 2010, when the government of Uganda through the OPM sought to acquire land to resettle the survivors of the Bududa landslides. This coincided with the increasing return of displaced persons, including members of the aggrieved Wanambuko family.

The struggles over Plot 94 speak to the general privileging of title deed holders in Uganda. Although Uganda’s land legislation recognizes customary land rights, the government policy on land in the last two decades has tended to prioritize national development and efficient exploitation of land and associated resources. This promotes the need to acquire land titles and has heightened the stakes over land ownership. Moreover, fraud and irregularities in the land registration office in Kampala are commonly acknowledged to be rampant. In 2007, Omara Atubo, then Ugandan Minister of Lands, acknowledged that some criminals worked with the Ministry employees to forge or alter titles. Atubo promised that the Ministry would decentralize its registry to enable Ugandans living far from Kampala to process titles from nearby districts. “With a decentralized land registry,” Minister Atubo argued, “it will be easier for people to access loans as banks can easily log on to our records and verify anyone’s title” (Obore Reference Obore2007). Atubo was silent on the downside of titling, especially in regard to proof of land ownership. Plot 94 provides a good example of the inherent problems. When lawyers asked the Ministry of Lands and Urban Development to ascertain ownership of this land, the Ministry released a search statement on February 6, 2014, indicating that the land had no encumbrances and that the registered proprietor, George Ochwo, had registered it on September 2, 2013.Footnote 41 Ochwo had successfully registered the land in spite of the contestations from Wanambuko’s family and RDC Wamoto’s directive that the aggrieved family should occupy the land. The search at the Ministry merely drew on the available database and paid no attention to the reality on the ground. The Ministry’s disclaimer did little to help the situation: “It is you to satisfy yourself that this land is the property of the person in whom you are interested in and not of someone else of the same name.”Footnote 42 The history of Plot 94 shows that registration of land and possession of a title deed do not guarantee the absence of encumbrances.

Looking up to the President’s Office?

Emma Elfversson (Reference Elfversson2015) has argued that central governments often intervene in conflicts in order to control local resources and benefit their supporters. In East Africa, Claire Medard (Reference Medard2010:20) demonstrates that state involvement in land conflicts is sometimes a “deliberate political strategy on the part of the leaders to accumulate wealth and power through politics of patronage.” Land conflicts in Uganda, and the Mount Elgon region in particular, provided an opportunity for President Museveni to intervene as a peace broker during the 2006 and 2011 presidential elections (Medard & Golaz Reference Medard and Golaz2013). The use of local disputes by politicians as a political resource is a well-known tactic in Uganda (Medard & Golaz Reference Medard and Golaz2013; Sjögren Reference Sjögren2014).

Relatedly, the conflicts in Bunambutye show how the president centralizes power and renders local authorities redundant. In 2009, when elders in Bunambutye reported to President Museveni that some leaders had been selling land without regard to the bona fide owners, the president instructed the Minister of Lands to sort out the mess and cancel irregularly acquired land titles (Etukuri Reference Etukuri2015). However, this was not done. Similarly, frustrated by the unwillingness of the district authorities to address their predicament, the widows and children of Wanambuko appealed to Museveni to save them from the new claimants who “ha[d] encroached on our land which our late father left for us.”Footnote 43 They made this appeal after Ochwo’s team had demolished their houses and destroyed their property and the local leadership had failed to help them. Although the president’s Principal Private Secretary directed the RDC of Bulambuli to address the matter and resettle the family, and although the RDC cleared them to settle on their land, the new claimant fenced off the land to block the family from accessing it. He instead filed a suit of trespass against the lawful owners of the land.

With tensions continuing to escalate, in October 2014 President Museveni directed Prime Minister Ruhakana Rugunda to resolve the land conflicts in Bulambuli.Footnote 44 Complainants, including members of the Wanambuko family, were directed to channel their grievances to the president through the OPM. In a letter dated October 17, 2014, several decried the “rampant grabbing and Illegal sale of peoples land by the politicians of Bulambuli.” The letter, in part, reads:

The true and bonafide [sic] owners of PLOTS 10, 11, 93 and 94 Bunambutye sub-county, Bulambuli district would like to send our sincere appreciation to NRM government for the tireless efforts ensured in addressing the plight of the vulnerable citizens in Uganda.

We would like to send our warm greetings through your esteemed office to H.E. Y.K. Museveni the president of the republic of Uganda for the job well done for the past twenty-seven years in power and congratulate you upon the new appointment as the Prime Minister …. We have really tested and enjoyed the fruits of his liberation …. May the Almighty God bless him with more wisdom and prolong his life.Footnote 45

The complainants hoped that by cajoling President Museveni and praising his government, they would persuade the prime minister—and, by extension, the president—to address their plight. They detailed their history of displacement from Bunambutye and eventual return following the “defeat against Karamojong cattle rustlers by the NRM government.” However, they now feared dispossession by the new claimants.Footnote 46 Earlier, the aggrieved family had learned that Ochwo was bidding Plot 94 for sale to the OPM.Footnote 47 The very office that they were looking to for support was actually a potential buyer of the contested land. This complicated matters even further, because it created a clear conflict of interest.

Parker Shipton’s (Reference Shipton2009) study among the Luo of Kenya underscored the centrality of ancestral graves and land tenure and the ways in which ancestral land bound relatives together. This situation was similar among the Babukusu in Bunambutye. One of Wanambuko’s widows narrated that although her husband was buried in Kenya, her father-in-law and some of her children had been buried on the contested family land before the 1979 displacement: “My children were buried here!” she cried. “This land belongs to me and my children.”Footnote 48 Although graveyards serve as land markers because families bury the dead around homesteads on ancestral land, the district authorities were not sympathetic to the widow’s entreaties. Instead, they privileged the title holders as the bona fide owners. It was apparent that possession of knowledge and history of a relationship to the contested land would not guarantee customary rights and resolve the dispute.

Reference to clan history proved equally ineffective. In a caveat to Plot 94, Moses claimed that their clan (Basimaolia-Babutu) had “since time immemorial customarily owned about 200 Acres” of the land under contestation.Footnote 49 Although this was an exaggeration, Moses intended to underscore the fact that the land had belonged to his father, who had bought it in 1954. The British colonial authorities had opened up Bunambutye and the surrounding areas for settlement in the 1920s, and “many men from the densely-populated areas of Southern and Central Bugisu migrated there for free land” (Heald Reference Heald1998:91). However, by the mid-twentieth century, there was individual land tenure under clans or families in the entire Bugisu region because of both the hard work involved in clearing heavy forests for cultivation and the increasing population. As a result, “boundaries hardened” between plots of land and sometimes “disputes took place,” but these were effectively settled by the elders (Gayer Reference Gayer1957:9). By the 1960s, there was no free land in Bugisu. The price per acre in the sparsely populated areas of Bunambutye went for about UGX200 an acre, compared to the densely populated coffee-growing areas where the price was as high as 1500 an acre (Heald Reference Heald1998). By invoking clan identity and claiming ownership since “time immemorial,” Moses sought to use old ties to support the family’s claims to physical space and to show that the land was part of the family’s history and identity (see Meinert et al. Reference Meinert, Willerslev and Seebach2017). Unfortunately, this did not persuade the local authorities to consider the plight of the aggrieved family.

Moreover, the chances of the complainants getting justice from the court system were minimal. As Matt Kandel (Reference Kandel2017:402) cautions, the statutory court system in Uganda “favours the elite and middle class who possess greater disposable income and are therefore more able to afford legal fees.” To confirm this, in his letter to the IGG, dated October 20, 2013, Moses bemoaned: “Madam, … my family is in untold pain and kindly seeks your indulgence into this case so that our family can secure justice.” The family could not afford legal fees. As he expressed it, “We have no money to start a court process as is advised by many and the people involved in this injustice are wealthy and powerful which leaves our family at the mercy of the state.” Moses hoped that the involvement of the IGG would “bring the truth into light and save us from this magnitude of violence we have suffered and [are] still suffering.”Footnote 50

In light of the heightened anxieties, violence, and rampant land evictions in the country, Museveni appointed a commission of inquiry into land matters in 2017. Chaired by Justice Catherine Bamugemereire, the commission was tasked to look into various land-related issues including, among others, the processes and procedures of land administration and registration, the legal and policy framework surrounding government land acquisition, as well as the mechanisms of dispute resolution available to persons involved in land disputes (PPU 2017). In July 2019, committee members visited Bunambutye to hear complaints and collect views on how the land administration in the region could be improved. During the hearings, land owners asked the commission to cancel all the land titles held by investors whom they accused of grabbing their land.Footnote 51 This proposal reinforced earlier recommendations by both the president and the Odwee committee. On July 29, 2020, the Bamugemereire Commission handed its report to the president. Among other things, the commission revealed that “the land fund established by government to settle land matters is used to finance irregular transactions involving payment of huge sums of money from the land fund to brokers and well-connected individuals in Kampala” (Vision reporter 2020). This further confirmed the ongoing fraud and conflict of interest in institutions responsible for land-related matters.

Government efforts to resolve the land conflicts in Bunambutye have not effectively addressed the concerns of the returning residents. The recommendations of the different committees which gathered the views of the affected persons have not been implemented. The general feeling among the affected persons is that their adversaries are too powerful to be touched. How then does one address such a crisis? Christian Lund (Reference Lund2008) proposes adjudication as a key aspect in resolving land disputes. Having an impartial arbiter listen to both parties without interference from partial local leaders and security forces might help. Combining both indigenous and endogenous approaches to peace building makes the process more inclusive (Murithi Reference Murithi and Francis2008).

Conclusion

Conflict over land in sub-Saharan Africa and in Uganda in particular continues to attract the attention of researchers and policy makers. Scholars have explained how increasing population, social differentiation, governance, large-scale land expropriation, and war or conflict, as in the case of Northern Uganda, all can lead to land conflicts. A less-researched area that deserves attention is the relationship between cattle rustling and land conflicts. The extant literature focuses on the rationale for cattle rustling and its effect on arms proliferation, intercommunal conflicts, terrorism, and organized crime. Focusing on the controversy over the ownership of Plot 94 in Bunambutye in eastern Uganda, this article has explored the ways in which Karimojong cattle rustling has engendered land conflicts and the various attempts to build peace in the aftermath of the violence.

The intensification of Karimojong cattle rustling following the fall of Amin’s regime in Uganda and the subsequent arms proliferation displaced residents of Bunambutye and separated them from their land. After more than twenty years, the Government of Uganda under Museveni contained the Karimojong attacks on Bunambutye through the use of forcible disarmament. This failed to bring peace to many of the displaced persons because, as they sought to return to their land, they encountered unscrupulous new claimants who had acquired titles for the disputed land through irregular means. The end of cattle rustling, coupled with the availability of unoccupied land, the increasing commercialization of agriculture, and government plans to resettle the survivors of the Bududa landslides attracted the attention of land dealers who rushed to acquire land in Bunambutye with the intention of reselling it at higher rates. The scramble for land coincided with the return of the displaced customary owners from Kenya. The ensuing competing land claims led to irreconcilable conflicts.

Instead of listening to both parties, most local leadership openly supported the elite title deed holders while disregarding those with customary claims. The pleas of the customary owners attracted the attention of President Museveni, who in turn constituted commissions of inquiry to investigate and make recommendations; but these recommendations were subsequently not implemented. To resolve such impasses, it may be more productive to place affected communities and families at center stage. The commissions of inquiry recommended irregularly acquired land titles be canceled. It is unfortunate when government-orchestrated commissions of inquiry recommendations end up shelved. Official responses to these disputes have enabled high profile personalities to defy rules without suffering consequences. The state has yet to take a clear stand in support of the customary rights of families.

Acknowledgments

Research for this article was funded by the African Peacebuilding Network of the Social Science Research Council and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation of New York. Initial drafts of this essay were presented at IFRA in Nairobi and at the ASAUK at Cambridge in 2016. I thank IFRA and Dr. Cherry Leonardi, who used her grant from the Gerda Henkel Institute to fund my travel to Cambridge. I am grateful to Prof. Cyril Obi and Rhiannon Stephens for reading through my drafts. Lastly, I am indebted to the editors of ASR and the anonymous reviewers for their comments that helped to shape my thoughts.