Introduction

Globally, there are nearly 50 million people living with dementia and this is predicted to reach 131.5 million by 2050 (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2015). With no silver bullet cure on the horizon, researchers have called for a greater focus on ‘care over cure’ (Whitehouse, Reference Whitehouse2014). ‘Ecopsychosocial’ (Zeisel et al., Reference Zeisel, Reisberg, Whitehouse, Woods and Verheul2016) initiatives are considered a core element of dementia care research (Orrell Reference Orrell2012; Kenigsberg et al., Reference Kenigsberg, Aquino, Berard, Gzil, Andrieu, Banerjee, Bremond, Buee, Cohen-Mansfield, Mangialasche, Platel, Salmon and Robert2016) as they provide a cost-effective means of supporting the wellbeing (Aguirre et al., Reference Aguirre, Spector and Orrell2014; Dugmore et al., Reference Dugmore, Orrell and Spector2015; Oyebode and Parveen, Reference Oyebode and Parveen2016) and psychological needs (Nyman and Szymczynska, Reference Nyman and Szymczynska2016) of people living with the condition. The term ‘ecopsychosocial’ is used in this paper as it provides more positive language that defines the nature of the initiative, rather than its outcomes, and takes into account the contextual and environmental factors (eco) that are also likely to influence its success. Zeisel et al. (Reference Zeisel, Reisberg, Whitehouse, Woods and Verheul2016) argue that this terminology enables academics and practitioners to describe better the full range of approaches and interventions within the dementia care field, thereby ensuring that they can be more readily compared and connections can be drawn between them.

Despite the known beneficial outcomes of ecopsychosocial initiatives, there is a dearth of literature that provides a theoretical interpretation of the ‘active mechanisms’ (Dugmore et al., Reference Dugmore, Orrell and Spector2015) that underpin them; that is, the factors that work, appeal to and support the positive outcomes for people with dementia. This means it is difficult to generalise the findings and consequently this hinders practitioners’ abilities to support people with dementia effectively and ensure that resources are used most efficiently. As such, researchers have called for a better understanding of the factors for successful employment of ecopsychosocial initiatives (Dugmore et al., Reference Dugmore, Orrell and Spector2015; Kenigsberg et al., Reference Kenigsberg, Aquino, Berard, Gzil, Andrieu, Banerjee, Bremond, Buee, Cohen-Mansfield, Mangialasche, Platel, Salmon and Robert2016; Oyebode and Parveen, Reference Oyebode and Parveen2016). This is particularly important when working with older men (65+ years) more generally, and those living with dementia, who may find it difficult to address issues relating to their mental, physical and emotional wellbeing (White et al., Reference White, de Sousa, de Visser, Hogston, Madsen, Makara, Richardson and Zatonski2011), and are often reluctant to engage with health initiatives, thereby increasing their risk of isolation, social exclusion and subsequently poorer health outcomes (White, Reference White2011; White et al., Reference White, de Sousa, de Visser, Hogston, Madsen, Makara, Richardson and Zatonski2011; Baker et al., Reference Baker, Dworkin, Tong, Banks, Shand and Yamey2014; Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015). An acknowledgement of this issue has resulted in a call for men to be included within the global health equity agenda (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Dworkin, Tong, Banks, Shand and Yamey2014) and led to a specific focus on men's health policies in countries such as Australia (Australian Government, 2010), Ireland (Baker, Reference Baker2015) and Brazil (Spindler, Reference Spindler2015).

This suggests there is a need to develop a theoretically driven understanding of how to engage successfully older men with dementia in community ecopsychosocial initiatives. This paper addresses this by using an ‘off-the-shelf’ digital gaming technological initiative as a medium to explore the ‘active mechanisms’ for engaging community-dwelling older men with dementia living within three rural areas of England. In doing so, it provides recommendations for researchers, practitioners and policy makers when designing and implementing ecopsychosocial initiatives to support the wellbeing of this population. The research question central to this paper is: what are the ‘active mechanisms’ for engaging rural-dwelling older men (65 years+) with dementia in a community technological initiative?

Masculinity as a theoretical lens

The concept of masculinity provides a useful theoretical lens for addressing the above question. It sits within the wider context of ‘gender’, which is a dynamic, social structure constructed by individuals, to perceive and make sense of the world around them (Connell and Pearse, Reference Connell and Pearse2015), and performed in particular social, cultural and historical contexts to establish themselves as ‘male’ or ‘female’ in the eyes of others (Courtenay, Reference Courtenay2000). Masculinity ideologies (masculinities) refer to those cultural attitudes and beliefs that are thought to be ‘male’ (Connell and Pearse, Reference Connell and Pearse2015; Thompson and Bennett, Reference Thompson and Bennett2015). They are developed and reinforced throughout a lifetime in accordance with the culture of the society for that particular time and place (Connell, Reference Connell2005; Thompson and Bennett, Reference Thompson and Bennett2015) and by adulthood, the majority of men will be aware of the standards and expectations that are associated with masculinity (Connell and Messerschmidt, Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005; Connell and Pearse, Reference Connell and Pearse2015).

The seminal work of Connell on ‘hegemonic masculinity’ is integral for understanding work within this field. This masculinity is distinguished from other masculinities and embodies the current ‘most honoured way of being a man’ (Connell and Messerschmidt, Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005: 832) as defined by the historical era, social institution or community. Whilst hegemonic masculinities may be practised by only a minority of men, it can act as a benchmark to guide men's gendered lives and judge their achievements (Connell and Messerschmidt, Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005; Thompson and Bennett, Reference Thompson and Bennett2016; Thompson and Langendorefer, Reference Thompson and Langendorefer2016; Twigg, Reference Twigg2020) as well as provide a hierarchical status that favours them over heterosexual women, people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender (LGBT), as well as other perceived ‘lesser’ masculinities (Connell, Reference Connell2005; Connell and Messerschmidt, Reference Connell and Messerschmidt2005).

These traditional Westernised masculinities that today's older men would have grown up in, expected them to follow conventional heteronormative masculinities and succeed in a career, and as husbands and fathers (Thompson and Langendorefer, Reference Thompson and Langendorefer2016). It favoured men that were white, middle class, heterosexual, in their early midlife who displayed characteristics of stoicism, emotional impenetrability and fierce resolve, as well as strength, competitiveness and success, reliability, capability and a sense of control (Kimmel, Reference Kimmel1996; Coston and Kimmel, Reference Coston, Kimmel, Kampf, Marshall and Petersen2013). To acquire these masculinities, men would suppress emotions, needs and ‘feminine traits’ (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman, Brod and Kaufman1994). These masculinities would have been prevalent throughout the lives of today's older men and may have influenced their pattern of gender relations (Connell, Reference Connell2005) and their health-seeking behaviours (Sloan et al., Reference Sloan, Conner and Gough2015), setting them up for difficult late-life experiences (Coston and Kimmel, Reference Coston, Kimmel, Kampf, Marshall and Petersen2013). Research also suggests they may be particularly pertinent in rural-dwelling men who can align more closely with hegemonic masculine ideals when compared to their urban male counterparts (Levant and Habben, Reference Levant, Habben and Stamm2003; Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Vogel and Heimerdinger-Edwards2013).

Despite some discourses depicting a de-gendering process in later life (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg2018), as men age, research has suggested they continue to draw from a gendered lens when understanding their experiences and constructing their identities (Hurd Clarke and Lefkowich, Reference Hurd and Lefkowich2018; Twigg, Reference Twigg2020). For some older men, their constructed ageing masculinities can be closely aligned with this hegemonic ideal and so result in them downplaying health concerns (Hurd Clarke and Bennett, Reference Hurd and Bennett2013), avoiding seeking help (Yousaf et al., Reference Yousaf, Grunfeld and Hunter2015) and positioning themselves relationally superior to heterosexual women and LGBT populations (Hurd Clarke and Lefkowich, Reference Hurd and Lefkowich2018). They may also adopt masculine norms that are reminiscent of their younger hegemonic masculinities. For instance, Thompson and Langendorefer (Reference Thompson and Langendorefer2016) found that as no ‘blueprint’ for ageing exists, some older men still sought to follow, yet struggled to obtain, these traditional masculinities. These masculinities may result in the social exclusion and subsequent health deterioration of older men due, in part, to their resistance to participate in community-based social groups as well as community-based health services and preventative health activities (White, Reference White2011; White et al., Reference White, de Sousa, de Visser, Hogston, Madsen, Makara, Richardson and Zatonski2011; Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015). However, other studies have found that as some men age, and in response to life changes, they reinterpret their masculinities. This includes willingly embracing the opportunity to abandon the hyper-masculine work culture in favour of developing other aspects of their identities (Slevin and Linneman, Reference Slevin and Linneman2010) or to focus on their family life (Wentzell, Reference Wentzell2013), as well as openly acknowledging their vulnerability (Hurd Clarke and Lefkowich, Reference Hurd and Lefkowich2018) and consequently engaging in help-seeking behaviours (Courtenay, Reference Courtenay2000).

Despite contrasting findings, these strands of research suggest that, whilst there is a tendency for research to construe older men as androgynous and stripped of their gendered, sexual identity (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015), gender and masculinities still remain an important determinant for men's experiences and health behaviour in later life. As such, it is necessary to adopt a more refined understanding of how to engage the growing population of older men more widely (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015) as well as those living with dementia.

Masculinity and dementia

Gender is rarely acknowledged when exploring the lived experiential accounts of people with dementia (Hulko, Reference Hulko2009; Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Dahlke and Purves2013; Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Gjernes, Lotherington and Obstefelder2018). In part, this may be attributed to some dehumanising discourses that can engulf dementia and result in the de-gendering of people living with the condition (Sandberg, Reference Sandberg2018). Despite this, the limited research suggests masculinities are an important influence on the lives of men. Hulko (Reference Hulko2009) demonstrated that dementia was perceived as more devastating to those socio-economically privileged participants such as white, middle- to upper-class men, and they required the involvement of others to alleviate issues. This was opposed to less-privileged individuals who perceived dementia as ‘no big deal’ in the grander scheme of challenges they contended with in their daily lives. Furthermore, Phinney et al. (Reference Phinney, Dahlke and Purves2013) highlighted that as two Canadian community-dwelling older men with dementia became less active and less independently capable, they expressed a sense of loss to their masculinity and this resulted in periods of frustration. Consequently, in an attempt to regain or sustain their masculinities, they often opted to undertake work-related pursuits and masculine activities that had filled their lives in the past. They were supported in these endeavours by their care partners and families who noted the importance of providing the men with a sense of continuity so they felt connected and included. The families also discussed their desire to uphold the men's role as head of the family despite the challenges and tensions that this could result in.

Therefore, similar to older men more generally, this limited literature highlights the importance of masculinities in the experiences of community-dwelling older men with dementia. Consequently, it is important to consider them when engaging this population. However as Bartlett et al. (Reference Bartlett, Gjernes, Lotherington and Obstefelder2018) posit, it is still unclear how health and social care professionals can incorporate gender awareness into their work. This study provides recommendations on how this may be achieved.

Engaging community-dwelling older men in ecopsychosocial initiatives

The ‘Men in Sheds’ literature has been successful in elucidating factors for engaging community-dwelling older men, particularly those in rural areas, and demonstrating benefits for ‘members’ mental, physical, social and emotional health and wellbeing (Wilson and Cordier, Reference Wilson and Cordier2013; Cordier and Wilson, Reference Cordier and Wilson2014; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Cordier, Doma, Misan and Vaz2015; Waling and Fildes, Reference Waling and Fildes2017). The ‘sheds’ are often located in community spaces or residential care settings and are equipped with a range of workshop tools. Milligan et al. (Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015) suggest part of their appeal is their ability to provide a gendered space that enables older men to perform and reaffirm their masculinities. This includes undertaking activities they have been accustomed to throughout their lives, in an informal, less-pressurised setting, as well as socially interacting within a male-only environment. This former point resonates with other research that has demonstrated older men (Genoe and Singleton, Reference Genoe and Singleton2006; Wiersma and Chesser, Reference Wiersma and Chesser2011) and those with dementia (Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Dahlke and Purves2013) enjoy engaging in activities that are reminiscent of their younger masculinities, particularly when they are not required to compete as they may have done in their youth. However, Wiersma and Chesser (Reference Wiersma and Chesser2011) warn that these leisure activities, if performed unsuccessfully, can reinforce the stigma attached to the social construction of an ‘old man’ and so detrimentally impact on men's wellbeing.

Whilst this research offers a more refined understanding of engaging community-dwelling older men, Milligan et al. (Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015) note that participants with dementia struggled to connect socially. As posited by other research (McParland et al., Reference McParland, Kelly and Innes2017), this was partly attributed to the reluctance of those without cognitive impairments (through discomfort or anxiety) to socialise with members with dementia. This highlights the need for further research to outline the factors required to promote an inclusive and non-threatening, or ‘conceptually safe’ (Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, O'Connor, Loiselle, Hickman, Heibein, Hounam and Mann2016; Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Kelson, Baumbusch, O'Connor and Purves2016), community ecopsychosocial initiative that appeals to older men with dementia.

A limited number of studies have addressed this aim, and all have used the medium of football (Solari and Solomons, Reference Solari and Solomons2012; Tolson and Schofield, Reference Tolson and Schofield2012; Carone et al., Reference Carone, Tischler and Dening2016). This research has highlighted certain factors for success, including repositioning the men as experts during the conversations (Tolson and Schofield, Reference Tolson and Schofield2012) and providing a male-only environment that encourages a ‘dementia-free’ (no talk about dementia) zone (Carone et al., Reference Carone, Tischler and Dening2016). However, these studies offer no discussion linking their findings to theories of masculinities. Therefore, further research that adopts a masculinity lens is likely to provide theoretical insight into the ‘active mechanisms’ for engaging community-dwelling older men with dementia, thereby enhancing the generalisability of the work and better informing dementia practitioners.

Using off-the-shelf digital gaming technology

Over recent years, the role of technology to support people throughout their ‘journey with dementia’ has become better acknowledged (Meiland et al., Reference Meiland, Innes, Mountain, Robinson, van der Roest, García-Casal, Gove, Thyrian, Evans, Dröes and Kelly2017; Kenigsberg et al., in press; Lorenz et al., Reference Lorenz, Freddolino, Comas-Herrera, Knapp and Damant2019). These various forms can include Assistive Technology (AT) such as medication aids or locator devices, Information and Communication Technology (ICT) including telecare and telemedicine, as well as off-the-shelf, digital gaming technology. Scholars have argued that technology development within the dementia field has primarily focused on providing safety and security for people living with the condition and their care partners. Consequently, there is a need to understand better how it can be used to provide people with opportunities for new experiences and to engage in leisure activities that are stimulating, enjoyable and fun (Astell, Reference Astell, Sixsmith and Gutman2013; Joddrell and Astell, Reference Joddrell and Astell2016), equally important facets for living well with dementia. This is particularly pertinent in rural areas (Baker et al., Reference Baker, Warburton, Hodgkin and Pascal2017), including in the United Kingdom (Townsend et al., Reference Townsend, Sathiaseelan, Fairhurst and Wallace2013) where the rural–urban digital divide continues; although as Bowes et al. (Reference Bowes, Dawson and McCabe2018) note, this is starting to change across rural Europe with dementia-specific and off-the-shelf technologies (such as iPads) becoming more widespread within dementia care practice.

Research within this field has been slowly growing and therefore has contributed to the decision to select off-the-shelf digital gaming technology, given the potential benefits it may offer both dementia practitioners and people living with the condition. For instance, this technology is ubiquitous within society, ensuring it is more readily available for purchase and use than other forms of dementia-specific technology, and furthermore it may not be associated with the same stigma that can accompany these other devices (Meiland et al., Reference Meiland, Innes, Mountain, Robinson, van der Roest, García-Casal, Gove, Thyrian, Evans, Dröes and Kelly2017). Emerging research has also demonstrated the benefits that this technology can have for the quality of life and social inclusion of people with dementia. A synthesis of the literature (Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Hicks and Innes2016; Joddrell and Astell, Reference Joddrell and Astell2016; Dove and Astell, Reference Dove and Astell2017; Cutler Reference Cutler2018) suggests this includes providing an opportunity for people to: interact with novel devices to remain connected to contemporary society; continue their life-long learning; challenge themselves and master new and sometimes complex skills; (re)engage with meaningful and enjoyable activities that promote cognitive stimulation, mild physical exercise and social interaction; increase self-confidence by challenging their perceptions of their own capabilities; and challenge public views regarding the competencies of people living with dementia. Finally, research has also pointed to the gendered nature of technology (Ravneberg, Reference Ravneberg2012), with these gaming ‘gadgets’ of modern society potentially appealing more to men rather than women.

All of these factors suggest that engaging with off-the-shelf gaming technology is likely to be a new experience for rural-dwelling older men with dementia, but one that has the potential to provide an appealing activity that is beneficial for their wellbeing.

Research approach

This study sought to address the issue of social exclusion for rural-dwelling older men with dementia within an English county. The research was initially framed as a Participatory Action Research (PAR) study, although, as outlined below, it did not adhere strictly to the PAR processes but rather drew from the principles of the approach (Reason and Bradbury, Reference Reason and Bradbury2008; Schneider, Reference Schneider2012; Chevalier and Buckles, Reference Chevalier and Buckles2013). These centred on the participation of the men throughout the research and included promoting their voices at all opportunities, situating them as ‘experts’ and providing a platform for mutual learning, as well as upholding their rights for autonomy and respect. This approach is widely advocated for enabling the inclusion of people with dementia throughout the entire research process (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Gillies, Carson, Whyte, Genoe, Loiselle and Sadler2012, 2016a; Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, O'Connor, Loiselle, Hickman, Heibein, Hounam and Mann2016) and ensured the initiative was fit for purpose.

As part of the PAR process the men were asked to name their group, provide feedback on the delivery of each session (including the set-up of the room and the technology and games used) as well as the final analysis, and take photographs (this was carried out by one man in each group who showed a desire to take on this role) and provide quotes to illustrate their experiences of participating in the study. These latter aspects were used as evidence to support three successful funding bids (one per group) to a local organisation, which enabled the initiatives to continue beyond the research period and provided an indication that the approach was welcomed amongst the county.

Ethical approval for the study was received from the lead author's institution ethics board.

The rural settings

Working in collaboration with dementia support charities based within the county, the research team identified the rural areas that would receive the technology initiative. This decision was made to ameliorate time and resource restrictions placed on the study.

The 2011 Rural–Urban Classification (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2015) was used as a guide to define the rural settlements and three rural areas were selected to host the initiative. Adopting a multi-site design enabled the findings to be compared across the different rural locations, thus improving the generalisability of the research. Table 1 presents a demographic overview of the rural locations with data gathered from the 2011 Census.

Table 1. Demographic overview of the three rural locations

Location One could be considered a ‘bypassed’ rural community (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales and Phillips2013). It had poor services and transport links, and was suffering from economic depression, with most of the local funding being directed towards an urban conurbation, which was situated nearby. Consequently, the technology initiative was one of very few services being offered locally for people with dementia (and the only one specifically for men with dementia). Conversely, Locations Two and Three were more consistent with ‘bucolic’ rural communities (Keating et al., Reference Keating, Eales and Phillips2013) with good resources and assets that were attracting recent retirees and London second-home owners (this was ascertained during informal discussions with local residents during the recruitment phase of the study). Location Two had good transport links to a nearby major urban conurbation whereas Location Three was surrounded by rural hamlets and isolated dwellings. Both of these rural locations provided some formal activities for people with dementia, although none offered technological initiatives or groups specifically for men with dementia.

The Technological Initiative (TI)

Developing the TI

The technology used during the TI was selected based on an extensive review of the literature, which outlined the range of off-the-shelf platforms that had been previously explored with people with dementia, and the findings from four consultation sessions held in the county with older men with dementia, their care partners and local dementia practitioners. The details of the consultation sessions are reported elsewhere (Hicks, Reference Hicks2016), although their implications for the design of the main TI are summarised below.

(1) Technology used within the TI: The men were offered an opportunity to use an iPad, Nintendo Wii, Nintendo DS, Nintendo Balance Board and Microsoft Kinect. Findings from the consultation sessions suggested the men struggled to engage with the Nintendo DS due to the small screen size. Consequently, it was removed from the main TI as many of the activities could also be undertaken on the iPad (something the men found easier to interact with). Furthermore, although some men found it difficult to interact with the Nintendo Wii within the short timeframe of the consultation (due to the combination of hand movements and simultaneous button pressing), this remained within the TI, as previous research has suggested people with dementia can engage with this motion sensor technology provided they are given appropriate time to do so (Fenney and Lee, Reference Fenney and Lee2010; Leahey and Singleton, Reference Leahey and Singleton2011; Dove and Astell, Reference Dove and Astell2017; Cutler, Reference Cutler2018). However as a result of this, it was decided to introduce the Microsoft Kinect within the preliminary sessions, as the men found this easier to engage with as there was no need for a controller. Once the men were accustomed with the sensor technology the more complicated games and movements required on the Nintendo Wii were introduced.

(2) Recruitment for the TI: Following feedback from the men that the word ‘technology’ could evoke fear or a misunderstanding of the TI (i.e. it was for educating them on using computer packages such as Microsoft Word or emails), this was removed from the recruitment flyers and terms ‘gadgets’ and ‘gismos’ used instead, as recommended by the participants. The groups were also promoted as ‘social clubs’ to remove further the focus from the technology and to highlight the other potential benefits of the TI as outlined by the men, such as having the opportunity to try something new and to interact with others socially.

(3) Set-up of the TI: Although care partners were present during the consultation and provided reassurance to the men, it was noticeable that the men appreciated the opportunity to engage in the activities on their own. Consequently, during the TI, care partners were invited to stay and watch the activities from afar but not actively participate in the groups. Interestingly, only care partners in Location Two remained to watch the TI, where they sat away from the activities and reported that they used the time as an informal support group. This ensured that the male-only environment could be maintained throughout the TI; that is, an environment where only the men were actively participating in the activities, group discussions and development of the initiative. Furthermore, although some of the men were initially reluctant to engage with the games, by watching others it encouraged them to also participate. This is consistent with Kahlbaugh et al. (Reference Kahlbaugh, Sperandio, Carlson and Hauselt2011) who suggest co-viewing is an important unifying process that can create a more relaxed social environment. As such, it was seen as important that the TI placed an emphasis on group activities as this would help to ameliorate any fears men had around using the technology and promote a more socially engaging atmosphere.

Delivering the TI

The TI consisted of three individual deliveries of a programme that ran in three rural locations of the county. Each programme continued for a total of nine weeks with one session per week lasting for two hours, including breaks for refreshments and informal discussions.

The TI was individually tailored towards the interests and capabilities of the men in each group as advocated by a person-centred approach (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, Dakheel-Ali, Regier and Thein2010; Kolanowski et al., Reference Kolanowski, Litaker, Buettner, Moeller and Costa2011). This meant that often the activities varied across the three rural locations, although there were three sessions that remained consistent (sessions 1, 2 and 9). These were:

• Introductory session (session 1) with two main activities that aimed to promote light-hearted dialogue between the men. The first was an ‘ice-breaker’ activity using the camera application on the iPad. The men were asked to take a photograph of another person around the table and once their picture had been taken they were invited to introduce themselves to the group. This activity engaged the men with the technology and provided valuable information that could be used to tailor subsequent activities towards their interests. The second activity involved the men naming their group. This encouraged them to take ownership of it and removed any associations with it being a support group for men with dementia. This name was used throughout the remainder of the research (Location One: Old Boys; Location Two: Done Roaming; Location Three: Marching On). Within this session, the sensor technology (Microsoft Kinect) was also introduced through playing the Kinect Sports Golf game, which was slow moving and required simple, basic movements to interact with it. This was important as research has highlighted detrimental impacts on people with dementia's willingness to re-engage with technology if they fail at their first attempt (Hicks and Miller, Reference Hicks and Miller2012).

• Session 2 introduced the ‘Game of Life’ application, a board game that works in conjunction with the iPad (which was connected to a television screen). This game was used as an additional medium to introduce the iPad (beyond the camera application) to the men and also encourage discussions about their lives. Again this information was used to tailor future sessions and highlight any similar life histories or interests between the men.

• The final session (session 9) was used to undertake an extensive discussion with the men about their experiences of taking part in the TI (discussed in the Research Methods section).

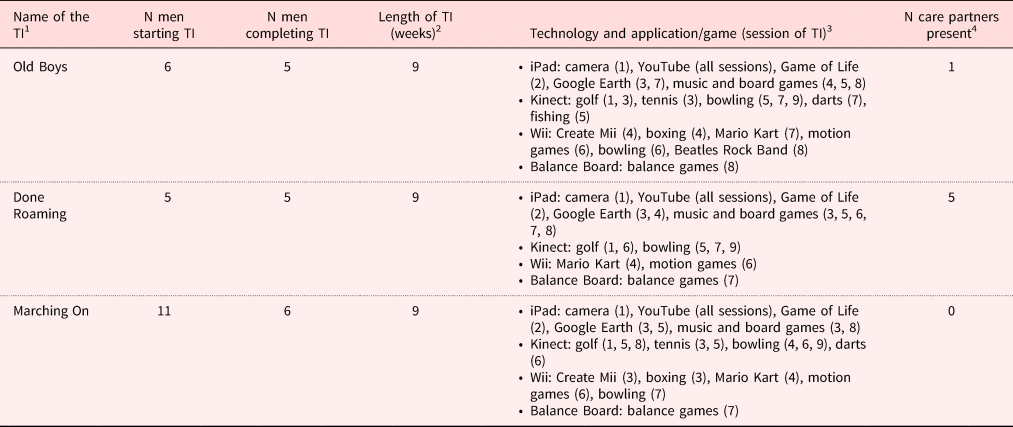

During the remaining sessions, other technologies were introduced to the men at different points such as the Nintendo Wii and the Nintendo Balance Board, and they were encouraged to suggest the games they wished to play. The majority of the activities were played within a group setting, although on occasions some of the men elected to use the iPad for board/music games on their own or in pairs, often whilst they waited for others to arrive at the session. The iPad was frequently connected to a large television to enhance its inclusivity, and the primary aim of these activities was to promote discussions between the men about their lives and interests. This included finding songs they enjoyed on YouTube or photographs of objects and places that were meaningful to them as well as using Google Earth to visit virtually the places they previously lived or had stayed on holiday. The motion sensor technology was used to promote physical activities that the men enjoyed such as golf, tennis and bowling. They were encouraged to play on their own (or in pairs) and compete against others in the group, or work together to challenge a computer opponent (e.g. play a hole each in a nine-round golf game against the computer). The majority of the games were embraced by the men and enjoyed to a more or lesser extent; however, a few were rejected after limited play by the different groups. These included the fishing (considered slow moving, boring and difficult to control the rod) and Beatles Rock Band (fast moving and difficult to time the appropriate actions) by the Old Boys, as well as the Wii Boxing (unrealistic) and Mario Kart (fast moving and difficult to navigate the racer) by the Marching On group. Table 2 provides a full breakdown of the games that were introduced throughout the TI.

Table 2. Overview of the Technology Initiative (TI)

Notes: 1. Named by the men attending. 2. One session per week lasting two hours from August to October 2014. 3. Games varied in each TI according to the interests and capabilities of the men as advocated by a person-centred approach (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Reference Cohen-Mansfield, Marx, Dakheel-Ali, Regier and Thein2010; Kolanowski et al., Reference Kolanowski, Litaker, Buettner, Moeller and Costa2011). 4. Not participating but in eyeshot.

During any activities or discussions, no reference was made to the men's dementia unless it was initiated by the men themselves. The activities focused solely on promoting the men's capabilities and engaging them in discussions about the wider context of their lives over and above their diagnosis of dementia. This is consistent with other initiatives that have sought to appeal to men with dementia through the creation of ‘dementia-free’ zones (Carone et al., Reference Carone, Tischler and Dening2016).

The rural venues

Each rural venue was spacious enough to run the activities safely, had Wi-Fi availability as well as kitchen facilities to provide refreshments. They were also situated within a central location to enhance their accessibility. The venues were set up to support both the group activities and the one-to-one discussions. This included having a large open area, with chairs set up in a semi-circle around the television for the activities on the motion sensor devices, or a quiet area with tables, chairs and refreshments that would facilitate conversations or provide a place where the men could retreat to if they desired. A separate area was provided at the back of the venue for any care partners wishing to stay and watch the activities, although this only occurred in the Marching On group.

Role of the researcher during the delivery of the TI

The lead author acted as facilitator and primary researcher of the TI, with the aims of introducing the men to the various technologies and games, supporting them to engage with them successfully and collecting their feedback throughout each session to inform the subsequent sessions. During the TI, in an attempt to democratise the research process and break down the barriers between researcher/facilitator and participant, the lead researcher also engaged with the activities, sharing aspects of his life during discussions and pairing with the men during the competitive gaming activities. Through these means it was hoped that he could transition from a position of group ‘outsider’ to ‘insider’ (Bryce, Reference Bryce2013) through the research process, thereby enabling him to develop a trusting relationship with the men that could result in richer and more honest data being collected. This process may be particularly important in rural communities where ‘outsider’ professionals can be treated with initial distrust and scepticism (Szymczynska et al., Reference Szymczynska, Innes, Mason and Stark2011).

Participant recruitment

A purposive sample of 22 older men living in rural communities (65+ years) with a dementia diagnosis and five community volunteers participated in the TI. In addition to this, 15 care partners of the participating men took part in interviews that sought to elicit greater insight into their daily rural lives (as a means to contextualise the TI) and the perceived impact of the initiative (particularly immediately after the sessions and in the subsequent days). All participants were recruited through Memory Support Workers and Activity Leads within the communities as well as recruitment flyers that were distributed in local buildings (churches, pubs, libraries, halls) and in newspapers. The Process Consent procedure (Dewing, Reference Dewing2008) was followed to ensure the men's ongoing consent throughout the research. A demographic overview of the participants is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Demographics of participants

Notes: All participants were White British ethnicity. NA: not applicable.

Research methods

Qualitative methods, advocated for exploratory research (Robson, Reference Robson2011; Flick, Reference Flick2014) and eliciting ‘active mechanisms’ (Dugmore et al., Reference Dugmore, Orrell and Spector2015), were employed throughout the research. Multiple methods, including researcher's reflective field notes, aimed to collect data from the men as well as the care partners and volunteers as a form of ‘triangulation’ to add further insight into the research topic (Flick, Reference Flick2014). All of the sessions were filmed and then reviewed by the lead researcher when making reflective field notes. During the TI, informal discussions were undertaken with the men as they engaged with the technology or more formally at the end of each session during a longer focused conversation. These discussions asked them to reflect on the technology and games used, as well as the structure and format of the sessions. The data collected were used to inform the subsequent sessions of the TI. The data were supplemented with information obtained from the men during a formal focus group at the end of the nine-week initiative (as part of the TI) as well as a one-to-one, face-to-face open interview held at the men's home after the final TI session. These multiple qualitative methods were employed to offer the men varied opportunities to give feedback on the TI, in both a social setting, where they could share ideas amongst themselves (during the focus groups), and an intimate setting, where they could discuss their views in more detail and divulge information they might not have felt comfortable sharing within a group context. Table 4 provides an overview of the men who took part in each method, as well as the care partners who were interviewed.

Table 4. Overview of the research methods

Notes: 1. Left due to poor health. 2. Left due to concerns with the group. TI: Technology Initiative. NA: not applicable.

Data analysis

All data were transcribed, anonymised and uploaded on to NVivo 10 to manage the analysis process. An inductive six-phase thematic approach, as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006), ensured the themes were grounded in the original words of the participants. The data obtained from the men were initially analysed and, following this, volunteer, care partner and reflective field note data were examined to elicit further insights. During construction of the themes, detailed discussions were undertaken between the research team to provide rigour to the analytical process. Once the themes were constructed, a cross-case analysis was undertaken to explore any differences between the groups.

The final themes were presented to the men during a feedback session within their group around five months after the initiative finished. No changes were made to the themes or their sub-components post-discussions.

Findings

The data demonstrated that the TI provided the men with beneficial outcomes for their wellbeing and sense of social inclusion. These findings are not the focus of this paper and can be found elsewhere (Hicks, Reference Hicks2016). This paper examines the factors that appealed to and engaged the men in the TI. Three themes, constructed from the data, highlighted the mechanisms that were crucial for its success. These were the enabling technological activity, the conceptually safe male-only environment and the empowering approach. These, along with their sub-themes, are discussed in more detail below.

An enabling technological activity

The technology was important to the TI's success through providing a jovial activity that was meaningful to the men, and enabled them to express themselves and re-connect with a modern society.

Meaningful, accessible and jovial activity

The TI provided an enjoyable ‘outlet for everybody’ (Phil, Done Roaming, focus group) or ‘escape from home lives’ (Dick, Marching On, interview) that the majority of men welcomed within their rural location.

Yeah getting out of the house and getting away from your siblings or your wife or whatever is going on at home [is a benefit]. (David, Old Boys, focus group)

The men, their care partners and the volunteers discussed the importance of providing a range of technologies and games that enabled the activities to be tailored towards the men's previous interests, thereby enhancing the TI's appeal and enjoyment, and ensuring it ‘did not become stale’ (Gordon, Marching On, focus group).

I think a lot of it is very good … and you find, good lord, what a funny game this is. And, it's great fun, and you can see it, and all of them respond [the men], I respond, I don't always win but it's great! (Simon, Marching On, interview)

The sensor technology supported sporting or active games such as boxing, tennis, golf or bowling (all embraced by the majority of men) and the iPad was attractive to men with previous interests in board games such as chess (Bill) or backgammon (Joe). Furthermore, the intuitive nature of the games ensured that the men who had previously played games such as golf in reality would automatically adopt the appropriate actions/stance with little prompting. This enabled them to engage with the game with minimal support, and so re-connect with activities that were once important to them.

I loved the golf game … I can't go out and play on a course anymore. I don't have the money or equipment and … I'm not physically able to now but I love it … and I played it and I hit a good shot occasionally. About once every three weeks! (Tel, Marching On, interview)

Yes he really enjoys it. He used to play golf and fly fishing. He misses his golf and was in his element the other day when you played. I was driving him back and he just said: ‘I feel so elevated.’ And I said: ‘You mean like happy?’ And he said: ‘Yeah. We played golf today and I haven't played in ages!’ (Maggie, Done Roaming, reflective field notes (RFN), session 7)

Indeed, on some occasions when the activities could not be tailored towards the men's interests or perceived capabilities, they declined to participate. In two extreme cases, care partners from the Marching On group believed their husbands, Chris and Harry, left the TI as the activities did not align with their previous interests. However, it should be noted they never watched the TI, and so could only speculate. Unfortunately, when interviewed both men were unable to remember the TI in great detail.

Furthermore, the games’ light-hearted music, colourful graphics and jovial content along with the actions required to engage with the sensor technology (such as hitting moles around the head with a mallet or hula hooping) ensured the activities were humorous. The men and the volunteers noted that this was appealing as it ensured the men experienced little pressure when engaging with the activities.

Those games I will tell you are a cracker! … there's so much harmonies and laughs and jokes and you know, and it's good. (Bill, Old Boys, interview)

Those games were really good and the golf one we had a lot of fun with … Yeah that bloody golf game, we had a lot of fun that day. It's a great method of getting a laugh as well as encouraging them [the men] to be interested in, and part of, a group. (Greg, Done Roaming, volunteer, interview)

Indeed, on the rare occasions the men felt a sense of pressure to perform, the games lost their appeal. These instances usually occurred when the games were linked to activities the men were once competent with in their younger years, and as such they perceived a requirement to perform to a certain standard. For example, some men in the Marching On group who had previously been boxing coaches struggled to engage with the boxing game on the Nintendo Wii. As they failed to hit their opponent, they became increasingly frustrated with their performance as well as the volunteer supporting them, with one man shouting: ‘what would you know? How many fights have you been in?’ (Peter, Marching On, RFN, session 3). During feedback, Tel suggested he had not liked the game as it was ‘too unrealistic’ (Tel, Marching On, RFN, session 3) and consequently the game was never played again. This was also the case in session 3 with the Old Boys, when David struggled to engage with tennis (a previous interest of his) on the Nintendo Wii, and yelled at his female avatar ‘you're worse than my wife’ (David, Old Boys, RFN, session 3). After a few unsuccessful attempts he gave up on the game and refused to play it again. Although instances where the games had a detrimental impact on the men's wellbeing were rare, they needed to be carefully managed. This was usually overcome by placing the ‘fault’ on the mechanics of the technology rather than the individual, thereby alleviating some of the threat that the men felt to their sense of identity and their perceived capabilities.

This finding demonstrates the importance of tailoring activities to the interests and capabilities of older men with dementia and ensuring that they are not placed under any pressure to perform to certain standards.

An opportunity to express themselves

The activities enabled the men to express themselves both physically and verbally, and so garner respect from others present. Physical characteristics including athleticism and strength were demonstrated by the men when engaging with sensor technology games such as boxing and tennis. In particular, this technology enabled the men to display competitive characteristics during activities such as bowling and golf. As Angela noted:

Well it made him do a little bit of exercise, but it also boosted his morale, in as much as he felt he was achieving, he felt that he was you know winning the game. (Angela, Marching On, interview)

Interestingly, this competitive element was most pronounced in the Done Roaming group where care partners watched from a distance and would support the men from afar by shouting words of encouragement and heaping praise on them if they were successful. This appeared to enhance the men's enjoyment of the activities and their sense of achievement as they sought to be crowned ‘champion of the group’ (Barry, Done Roaming, RFN, session 6).

The competition was good … it was a healthy one and everybody … they could feel the progress they were making inside themselves. (Phil, Done Roaming, interview)

Furthermore, the technology provided a ‘scaffold’ (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton, Jones, Jutlla, Brooker and Grove2011) or prompt for social interaction and communication, whereby the men could position themselves as experts and highlight aspects of their lives and their achievements. Whilst there were instances of this occurring during games on the sensor technology, it was most prevalent when using applications on the iPad, as this provided instant access (through an internet connection) to applications, music, videos and pictures that could encourage and sustain social interaction, and so were ‘really good for getting the men to talk about their lives’ (Graham, Old Boys, volunteer, interview).

Terry used the iPad to locate areas of East London where he grew up. We had an interesting chat about this and he was able to find his old street using Street View

…He discussed the places where he had worked and showed me the streets he had frequented. He repeatedly commented that it had all changed with all the houses that had sprung up everywhere. (Done Roaming, RFN, session 4)

This finding demonstrates the importance of providing activities that enable older men with dementia to express themselves confidently and independently both physically and verbally, and so garner respect from others present.

‘Clobber along with the rest’ and re-connect with modern society

The data highlighted that whilst the majority of the men were initially unfamiliar with the technology, they welcomed the opportunity to engage with it. The men perceived the technology as a facet of modern society and so appreciated the chance to develop skills and knowledge that enabled them ‘to clobber along with the rest of them’ (Jess, Marching On, focus group).

But seriously it's progress. Everybody wants to be involved in progress don't you? No matter what you do. It opens a new chapter in your mind doesn't it? You would think it would never work but it does … But what you've proved is that things like that machine have opened our education. (Phil, Done Roaming, focus group)

For some men such as Joe, David (Old Boys) and Jess, engaging with the TI spurred their interest in buying the technology for their home so they could continue to play the games with their wives or grandchildren. As David noted:

It [the TI] sets you up to use it [technology] at home as well doesn't it? So that you don't just use it there but when you come home you can look back on what you did and then continue where you left off. (David, Old Boys, interview)

Whilst mastering these technological skills was integral for the men's sense of achievement, it also encouraged them to challenge negative assumptions around their capabilities, including their own perceptions of their abilities as well as those of the volunteers and the care partners. This was important for enhancing their sense of positive wellbeing.

As far as I'm concerned, I come here very glum, fed up and sorry for myself and I go away thinking that I can still do something even if it's something silly. I can still do something. (Doug, Done Roaming, focus group)

Just interesting to see how people who initially didn't look like they were that involved in it … even capable of being involved with it … took to it … So just to see that obviously it makes me look at things differently … and I don't now automatically assume that they are [unable to participate], you know, probably give them more time than maybe I would have before. (Tom, Old Boys, volunteer, interview)

This demonstrates the importance of enabling older men with dementia to engage in new and modern activities and to continue their learning so as to ensure they feel a connection to contemporary society.

A conceptually ‘safe’ male-only environment

The data suggested that the male-only environment was a ‘stroke of genius’ (Caroline, Old Boys, care partner, interview) and favoured by the men. It provided them with a non-threatening space where they felt comfortable speaking openly and did not have to temper their masculinities, thereby enabling them to develop a sense of comradeship and solidarity with others present.

A comfortable and familiar environment for self-expression

The data suggested the male-only environment encouraged the men to relax and engage freely in conversations with one another. This chance for socialisation was particularly important for some men, who suggested they were rarely afforded this opportunity in their daily lives.

Well it [the TI] helped to sort of meet other people. I don't socialise that much. (Bill, Old Boys, interview)

The men reported that their discussions would have been more restricted if women were present, as they would have ‘disapproved of the swearing’ (Joe, Old Boys, focus group) and the topics of conversation or would ‘take over’ (Joe, Old Boys, focus group) so that it became a ‘woman's club’ (Bill, Old Boys, interview). Consequently, they perceived this would have inhibited their ability to express themselves freely.

If you can swear, which now and then you can do, then you would feel offended with the women there. Then they would take over. And you would never get a word in edgeways and the woman always has the last word. I feel more relaxed with just men only. (Joe, Old Boys, focus group)

It's good amongst the boys you know? [With women] … you would sort of be limited in a lot of ways … you would have to be reasonable and so forth! (Dick, Marching On, focus group)

Yeah I think it's good [having a male-only environment] … All these blokes if they got annoyed would swear and relieve their feelings if they needed to do that … and they can here. (Doug, Done Roaming, focus group)

These sentiments were also conveyed by care partners and volunteers who stated that the environment enabled the men to engage in ‘male banter’ (Tom, Old Boys, volunteer, interview) and conversations that were ‘a bit naughty’ (Jean, Done Roaming, care partner, interview), as well as provided them sanctuary from a world that could potentially feel ‘over womaned’ (Veronica, Marching On, care partner, interview).

Well, I think it's a good idea [men-only], I think too many of these coffee mornings and things that we go to are full of women. There seem to be more women than men, and I think the men-only thing is good. (Sue, Marching On, care partner, interview)

Furthermore, care partners reported that this environment was one that the men would have been accustomed to during their younger years and working life, and so this sense of familiarity would have contributed to the men's feelings of security and so enhanced the appeal of the TI.

…all his working life he's been used to the company of men, he's never worked with women. And, all his hobbies were always to do with other men … the normality of socialising has, historically in his life, been with men and this is what he feels comfortable with. (Caroline, Old Boys, care partner, interview)

This male-only environment was rarely afforded the men in their current daily lives, but was viewed by both them and their care partners as important for enabling self-expression.

An opportunity for comradeship and solidarity

As the men were able to express themselves freely, they developed a sense of ‘comradeship’ (Doug, Done Roaming, focus group) and togetherness. They spoke in affectionate terms about one another, noting the ‘warm side to the group’ (Dick, Marching On, interview) and the ‘similar attitudes’ (Ken, Old Boys, focus group) where people ‘were only too glad to add their little bit’ (Dick, Marching On, interview).

I go there and it's like ‘alright Bob how are you doing?’ I don't think there's any there that will say anything against me. Yes they're good lads (laughs). (Bob, Old Boys, interview)

Furthermore, although the men's dementia was never openly discussed, the data suggested the environment enabled the men to connect emotionally around this issue, acknowledging all members were all on a ‘similar level’ (Dick, Marching On, focus group) but ‘you're not on your own’ (Gordon, Marching On, interview). This was appealing to the men and helped to provide them with comfort and reassurance, and there was a sense that if women were present then these connections would have been hindered as ‘blokes take notice of others because they are blokes’ (Doug, Done Roaming, focus group).

Well it's good to be with people and talk about things you have that you've experienced, and of course, meeting the Herberts in the same problem as yourself, it's a bit reassuring really. (Jess, Marching On, interview)

…you don't walk about with a placard saying I've got dementia … So it's helped me by seeing other people had the same problem as I had. Whether it was to the same degree or worse, you know, but there was other people there that I could see had got the same problem, and they were living their life okay. (Joe, Old Boys, interview)

However, it is noteworthy that through enabling the men to express themselves freely, the ‘diversity’ of the group and the ‘certain attitudes or interests’ became prominent, thereby making it difficult for certain men to ‘gel’ (Tel, Marching On, interview). For instance, in the Done Roaming group the tensions often centred on Doug, who felt his recent diagnosis of dementia was a threat to his masculinity. As such, he sought to ‘other’ the rest of the men in the group, refusing to sit with them at the beginning of the early sessions of the initiative and instead watched from a quiet corner of the venue where he could talk to the volunteer. This was managed within the group by slowly encouraging him to engage in activities with the men and join in discussions that centred on their lives, rather than dementia. Consequently, it was noticeable that, over time, he formed a bond with them and used the group as a source of support, although he was keen to disassociate himself with them during his final interview.

Well, I found them a bit odd actually [other men in the group], but then I'm a Londoner. So I did find it very hard to become a friend of … an associate. Alright, they're there and they're in the same poo as you are, so that's about all it amounts to. I wouldn't want to visit them or go out with them. I don't know. (Doug, Done Roaming, interview)

Unfortunately, within the Marching On group the men's conflicting interests were more difficult to manage and resulted in a few men making disparaging comments to others or refusing to engage with them. For instance, Tel would roll his eyes when Chris spoke of his love for classical music and vice versa when Tel would speak of his days as a boxing coach. At one point after Chris played a classical piece of music on the piano, Dave exclaimed ‘yeah I like music, but none of that rubbish’ (Dave, Marching On, RFN, session 2). Others such as Jess also commented ‘oh la-di-da, very posh!’ (Jess, Marching On, RFN, session 1) when Harry spoke at length about his home in the country and the tennis courts and horses he owned. This made for noticeable and uneasy tensions in the group that were only truly resolved when these men (Tel, Dave, Chris and Harry) left. As Josh, the Marching On volunteer, spoke of during his interview:

Now nobody is looking down their noses at somebody … I think that is what one or two had problems with initially. Like Harry and Tel, and I think that stopped them coming. (Josh, Marching On, volunteer, interview)

The finding demonstrates the importance of a male-only environment for providing a familiar and relaxing environment where older men with dementia can express themselves and connect on a deeper, emotional level. However, it also highlights the challenges that can be encountered when managing the multiple and diverse interests that may become apparent within this environment.

An empowering approach

The approach sought to empower the men by creating a platform that promoted mutual learning and respect between the researcher and the men throughout the development of the TI. This involved reducing the power of the ‘expert’ researcher to enable him to move from the position of ‘outsider’ researcher to ‘insider’ of the group by joining in with group discussions and activities. The data suggested that this approach was successful as researcher's reflective notes highlighted numerous instances where over time he became accepted by the men and they became more confident interacting with him. For instance, the men in all groups began to invite him to participate in the activities and make fun of his performances. Doug (Done Roaming) began to refer to him as ‘mate’ towards the end of the TI and Terry (Done Roaming) and Colin (Marching On) encouraged him to use their nicknames rather than their formal name. During feedback at one TI session, David noted that he had become a ‘friend of the circle’ (David, Old Boys, RFN, session 7) and on another occasion, Gordon (Marching On), who was initially reserved within the group, beckoned him aside at the end of a session to a quiet corner where his wife (who had come to pick him up) could not hear and began to open up about an intimate occasion he had with a lady on holiday (Gordon, Marching On, RFN, session 6). As Doug suggested during the final feedback session:

Your success is in the fact that really none of us are aware of you as being in charge or a tutor, which is so important. If you think you've got a governor then you'll be more wary. But you've been part of it. (Doug, Done Roaming, focus group)

In addition to reducing the power of the researcher, the approach further successfully empowered the men by positioning them as ‘experts’ in the development of the TI and encouraging them to name their group and take ownership of it. Although the men were initially reluctant to inform the TI, over time they became more willing, even if it might have offended the researcher. For instance, during one feedback session, the Old Boys stated the balance board games that included skiing and tightrope walking were too difficult, not a great deal of fun and possibly better suited for a younger audience. The data collected during the final focus groups and interviews demonstrated that this approach was welcomed by the men and something that

people I don't think are used to, especially that sort of age group and those with dementia. (Graham, Old Boys, volunteer, interview)

Yeah what I like about this [the TI] and what I have always liked every day I have come to this is the fact that we move into a mould for that day which is ‘what do you think boys?’ and it is coming from you. ‘Should we try this?’ You're the leader in other words without being bossy. (Phil, Done Roaming, focus group)

Some care partners also highlighted during feedback that this approach was an important mechanism for the success of the TI.

He thoroughly enjoyed it and every time you praised him or asked his opinion, he came away glowing! Really pleased he'd done so well with it. And he was always in a good mood afterwards and felt he had helped you with the club. He had big plans for it! (Maureen, Marching On, care partner, interview)

And I think your personality is important, if you'd been bossy, it wouldn't have worked at all, because men don't take to being told what to do or bossed around, but the way you handled it was brilliant! (Jean, Done Roaming, care partner, interview)

Furthermore, the men and their care partners suggested that providing a ‘dementia-free zone’ and removing the dementia focus from the TI was appealing to the men and was beneficial for their wellbeing and willingness to contribute.

I suppose because you know you've got a problem. But everything is alright yeah. It helps that the club does not focus on the problem. (Bill, Old Boys, interview)

Absolutely you don't focus on dementia and that is good. The atmosphere in the other one [group for people with dementia] is quite harrowing … is almost serious, serious medical and so very quickly you get grr (makes angry noise). (Doug, Done Roaming, focus group)

I mean he enjoys it … I shouldn't say this, he prefers yours because he feels better about going there, because he doesn't associate it as being part of the Dementia Club that kind of club. (Grace, Marching On, care partner, interview)

The findings demonstrate the importance of empowering older men with dementia when seeking to engage them, by positioning them as collaborators in the research, reducing the power of the researcher and removing any focus on dementia.

Discussion

The TI was welcomed by the majority of men and offered them an opportunity to engage in an activity that was not currently provided within their rural environments. It achieved its success through three ‘active mechanisms’ (Dugmore et al., Reference Dugmore, Orrell and Spector2015) that worked in tandem to appeal to them and provide them with an opportunity to express and reaffirm their masculinities. These were the enabling technological activity, the conceptually safe male-only environment and the empowering approach.

The following discussion examines these findings through a masculinity lens to provide a theoretical understanding of how to engage community-dwelling older men with dementia in a technological initiative. It also offers recommendations for policy, practice and research concerned with implementing ecopsychosocial initiatives more broadly that seek to engage with, and raise awareness of, this hard-to-reach population as well as to enhance their inclusion and wellbeing.

Provide opportunities to re-connect with activities associated with younger masculinities

The TI provided a wide range of applications and games that could be tailored towards the men's interests and capabilities. This ensured they were ‘meaningful’ (Roland and Chappell, Reference Roland and Chappell2015) and appealing to the men, by enabling them to re-connect with activities that were reminiscent of their younger masculinities and sense of ‘self’. This is consistent with research that suggests older men seek to maintain their engagement in activities they have undertaken throughout their lives (Genoe and Singleton, Reference Genoe and Singleton2006; Wiersma and Chesser, Reference Wiersma and Chesser2011; Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Dahlke and Purves2013; Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015). Previously, technological initiatives have tended to offer only one device in isolation (along with a limited set of games or applications chosen in advance by the researcher), such as the Nintendo Wii (Leahey and Singleton, Reference Leahey and Singleton2011) or iPads (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton, Jones, Jutlla, Brooker and Grove2011; Leng et al., Reference Leng, Yeo, George and Barr2014), and so this may limit their appeal to older men who have interests that cannot be catered for by this technology or who may struggle with some of the actions required to engage with it. Consequently, researchers and practitioners may find a more beneficial approach when delivering technological initiatives is to offer a wide range of devices and games/applications that are chosen by the men, thereby enabling them to be tailored towards their younger masculine leisure interests as well as their capabilities. This is also advisable for researchers and practitioners seeking to attract older men with dementia through other ecopsychosocial community initiatives. Currently, these initiatives, such as ‘Men in Sheds’ or football clubs (Solari and Solomons, Reference Solari and Solomons2012; Tolson and Schofield, Reference Tolson and Schofield2012; Carone et al., Reference Carone, Tischler and Dening2016), may be limited in scope and unappealing to men who, during their younger years, had limited knowledge of, or interest in, ‘sheds’ or football. Again, to ensure inclusivity, it is important that researchers and practitioners consider initiatives that provide a wide range of activities, thereby enabling them to be tailored to the multiple interests and masculinities of older men with dementia. A TI may be one such initiative that can achieve this and therefore warrants further exploration.

It is noteworthy that on occasions when the activities were tailored towards the men's previous leisure interests, this could evoke a sense of pressure to perform. When the men were unable to succeed, it detrimentally impacted on their wellbeing by emphasising their shortcomings when compared to the traditional masculinities they once aligned with. Fortunately, in these rare instances the men were able to situate the blame on the gaming technology and so diffuse any potential threat to their masculinities. However, this raises important implications for the broad-brush assertion that person-centred activities are always the most appropriate for people with dementia (Kolanowski et al., Reference Kolanowski, Litaker, Buettner, Moeller and Costa2011), and highlights the need for further research and guidance to support practitioners managing technological initiatives where these potentially difficult situations with older men with dementia can occur. This guidance may be particularly pertinent for practitioners running other ecopsychosocial initiatives, where the ‘blame’ for failure cannot be so easily situated on external devices, such as the technology. These instances are likely to be internalised by older men with dementia and so detrimentally impact on their perceived masculinities and sense of ‘self’ and wellbeing.

Provide non-threatening opportunities to perform and express masculinities

The TI provided welcome opportunities for the men to both physically and verbally perform and express their masculinities in a non-threatening or ‘conceptually safe’ (Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Kelson, Baumbusch, O'Connor and Purves2016; Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, O'Connor, Loiselle, Hickman, Heibein, Hounam and Mann2016) environment, and through this garner respect from others present.

Through the activities, the men were enabled to display and perform physical attributes associated with their masculinities such as strength, success, capability and competitiveness, but in a relaxed context due to the jovial concepts of the games and applications. This is similar to other initiatives that seek to engage older men by providing relaxed activities (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015). Particularly interesting was the men's willingness to undertake competitive practices. This was most pronounced in the Done Roaming group where men were competing for the respect of their care partners (who unlike the other groups had stayed to watch the activities) and using them to increase their ranking and sense of masculinity compared to the other men present, as posited by Genoe and Singleton (Reference Genoe and Singleton2006). Whilst it has been highlighted that older men still engage in competitive practices (Thompson and Langendorefer, Reference Thompson and Langendorefer2016), this is rarely encouraged in technological initiatives or more widely in ecopsychosocial initiatives targeted at this population, such as ‘Men in Sheds’, due to an assumption that it is not wanted or required (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015). These findings suggest a need for both technological and other ecopsychosocial initiatives to provide an element of friendly competition as this may appeal to the traditional masculinities of older men with dementia. Furthermore, they also add to the debate on the appropriateness of care partners within community initiatives for people with dementia (Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, O'Connor, Loiselle, Hickman, Heibein, Hounam and Mann2016), highlighting that within male-only initiatives, having them within eyeshot but out of earshot may help to create a social context that encourages older men to perform these important facets of masculinity, resulting in an enhanced sense of achievement. Further research is required to explore this within the context of technological initiatives as well as broader ecopsychosocial initiatives, and to elicit ways for practitioners to manage these dynamics appropriately to ensure care partners do not restrict the voices and autonomy of older men with dementia.

The TI also enabled the men to express their masculinities verbally by engaging in conversation whilst undertaking activities that encouraged and supported them to provide a narrative account of their life and achievements, thus offering them a secondary means to garner respect from others. This is consistent with wider research on ecopsychosocial initiatives, where Milligan et al. (Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015) posit that this form of ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’ communication (working while talking) is favoured by older men and enhances the appeal of the ‘Men in Sheds’ initiative. Through similar mechanisms, this study suggests that technological initiatives using ‘off-the-shelf’ digital gaming technological devices (and particularly the iPad) can also provide an appealing medium for promoting communication between older men with dementia. Furthermore, these devices (particularly the iPad) may offer a more beneficial means of ‘shoulder-to-shoulder’ communication for older men with dementia than typical ‘shed’ activities as, consistent with other research (Upton et al., Reference Upton, Upton, Jones, Jutlla, Brooker and Grove2011; Cutler et al., Reference Cutler, Hicks and Innes2016; Joddrell and Astell, Reference Joddrell and Astell2016; Dove and Astell, Reference Dove and Astell2017), they are able to prompt or ‘scaffold’ conversations through various media and so ameliorate memory difficulties that this population may face. This enables people to talk more competently and confidently about their lives and so provides greater opportunities for them to discuss their achievements and garner respect. Further research is required to provide guidance for practitioners on using this technology, as part of a community technological initiative, in a way that can stimulate and support conversations with older men with dementia.

The male-only environment and the ‘dementia-free zone’ approach were important contributing factors for enabling the men to perform, express and reaffirm their masculinities freely. The consideration of these environmental influencers is novel for a technological initiative but the findings are consistent with other ecopsychosocial initiatives that engage older men (Wilson and Cordier, Reference Wilson and Cordier2013; Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015; Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Cordier, Doma, Misan and Vaz2015) as well as those with dementia (Carone et al., Reference Carone, Tischler and Dening2016). Working in tandem, these factors were able to create a conceptually safe environment that is advocated when engaging people with dementia (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Gillies, Carson, Whyte, Genoe, Loiselle and Sadler2012, Reference Dupuis, Kontos, Mitchell, Jonas-Simpson and Gray2016b; Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Kelson, Baumbusch, O'Connor and Purves2016; Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, O'Connor, Loiselle, Hickman, Heibein, Hounam and Mann2016). The male-only environment, which was novel for the men within all three rural locations, appealed to them as it enabled them to re-connect with a familiar environment that was associated with their younger masculinities as well as limited the perceived threats they experienced to these masculinities. This latter aspect is particularly important as other research (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Payne, Bingley and Cockshott2015) has demonstrated how older men without dementia can perform actions associated with traditional hegemonic masculinities to exclude or ‘other’ (McParland et al., Reference McParland, Kelly and Innes2017) those living with the condition. Therefore, creating an environment where all the men acknowledged the difficulties they faced in sustaining their masculinities enhanced the inclusivity of the initiative. Furthermore, adopting an approach that did not encourage the men to discuss openly their dementia, and the emotional challenges they may encounter, appealed to them by ensuring they could maintain an outwardly stoic resolve and not have to express openly characteristics that might be viewed as feminine, thereby threatening their sense of masculinity. Through this appealing, ‘unspoken’ environment, the men were able to develop a sense of community and connect on an emotional level, and this provided them support and confidence. Developing this sense of ‘community’ has been posited as important and beneficial when engaging people with dementia in community initiatives (Dupuis et al., Reference Dupuis, Kontos, Mitchell, Jonas-Simpson and Gray2016b; Keyes et al., Reference Keyes, Clarke, Wilkinson, Alexjuk, Wilcockson, Robinson, Reynolds, McClelland, Corner and Cattan2016; Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Kelson, Baumbusch, O'Connor and Purves2016; Wiersma et al., Reference Wiersma, O'Connor, Loiselle, Hickman, Heibein, Hounam and Mann2016). Researchers and practitioners wishing to run technological initiatives as well as other ecopsychosocial activities would be advised to implement ‘dementia-free’ spaces that only encourage older men living with dementia to participate, if they wish to engage successfully with, and create a sense of community among, this population.

Provide opportunities for older men with dementia to retain authority