I

The Aberdeenshire branch of the Leslie Family were intensely involved with the material culture of Catholicism, before and after the reformation.Footnote 1 The Leslies of Leslie and the Leslies of Balquhain and Fetternear (subsequently the Counts Leslie in the Holy Roman Empire) played a part in the survival of pre-reformation objects—most notably the unique print of the Compassio Beatae Mariae,Footnote 2 now in the National Library of Scotland, and the Fetternear Banner, now in the National Museum of Scotland.Footnote 3 Once established on the continent, their fortunes were advanced rapidly by the part which Walter Leslie (1606-67) played in the assassination of Albrecht von Wallenstein at Cheb (Eger) on 25 February, 1634, and the collections which they formed at their Castle at Ptuj (Oberpettau) in Slovenia survive intact to a remarkable degree to the present day.Footnote 4 Little of what James Leslie, second Count Leslie, sent to Scotland in the 1690s to furnish the Castle or Palace of Fetternear in Aberdeenshire (either sacred or secular) has survived two Jacobite risings, various lawsuits, and a fire, but one superb set of High Mass vestments survives at the Blairs museum and these form the focus of this article.

The Leslies were one of the most successful families of the Scottish military diaspora, a notable part of that long tradition of foreign service which extends temporally from the Garde Ecossaise in mediaeval France to General Barclay de Tolly in Russian service in the Napoleonic wars. Both northern Catholic Leslies and their Protestant kinsmen from the lowland Rothes branch of the family seem to have prospered in this arena.Footnote 5 Five generals of the name of Leslie commanded the armies of four different nations – ‘Scotland, Germany, Sweden, and Russia – nearly all at the same time’ in the seventeenth century.Footnote 6 As well as Walter Leslie, first Count Leslie and Count James Leslie in the Habsburg Empire, these included the protestant Lord Leven in Swedish service and then in civil-war Scotland, as well as David Leslie, Lord Newark, of the Rothes family, who commanded in Sweden and England. In addition to this, the family produced ‘many colonels’ and lesser officers. Leven commanded 4,000-5,000 troops as Swedish military governor of Stralsund in Swedish Pomerania, to which post he was appointed in the middle of the unsuccessful 1628 siege of that city by the Imperial general Albrecht von Wallenstein.Footnote 7

It was the assassination of Wallenstein in February 1634 which brought about the dramatic rise of the Balquhain branch of the Leslie family in the person of Walter, later first Count. As the second son of the third marriage of John Leslie of Balquhain to Jean Erskine of Gogar, he had no expectations of inheritance in Scotland and initially served in the Protestant armies of the Netherlands and either Denmark or Sweden with a lowly rank. He appears to have either converted or re-converted to Catholicism after his part in the assassination of Wallenstein in 1634, but before his elevation to the rank of reichsgraf in 1637.Footnote 8 In his early career he appears to have identified as ‘Calvinist’ and David Worthington’s authoritative study describes Walter as being ‘an Episcopalian by background.’Footnote 9

In an interesting echo of earlier Leslie alliances with the leading Catholic family of Aberdeenshire, Sergeant (and future Count) Walter Leslie’s commanding officer in the War of the Mantuan Succession (1628-1631) and at the subsequent Thirty Years’ War battles of Bentheim, Freistadt and Lutzen was a Colonel. John Gordon. Despite their large difference in rank, the two men seem to have been close friends, and a commission for Leslie had been procured by the end of 1632. Their joint assassination of Wallenstein in 1634, was lavishly rewarded, but thereafter Walter Leslie’s focus seems to have been ceremonial (including one Embassy in 1665-66 to the Sublime Porte) rather than military: ‘his subsequent military career was sporadic and frequently disastrous, and absenteeism led to his being deprived of his last regiment by 1642.’Footnote 10 Writing in a different venue, however, Worthington qualifies his own statement:

[N]one of this ended his military influence. In 1650, besides receiving appointment to the rank of Field Marshal, Leslie became warden of the ‘Sclavonian marches’ and a general on the aforementioned ‘Croatian-Slavonian Frontier’, while, seven years on from that, he received promotion to the Vice-Presidency of the Imperial War Council.Footnote 11

With this sudden advance of his fortunes in the Empire, Walter, Count Leslie also acquired new influence in Britain, and his elder brother William Leslie became a member of the Privy Chamber of King Charles I in 1642, apparently at the behest of Walter, who had played a part in obtaining Prince Rupert’s release from prison in Linz four years earlier. Count Walter bought Ptuj Castle ‘from the Jesuits at auction in Zagreb in 1656’Footnote 12 Childless, he arranged that he would be succeeded in his various possessions by his nephew James Leslie (c.1621-1694), later second Count Leslie, who is best known for his service as General of Artillery at the battle of Vienna in 1683. Count James purchased the castle in Graz now known as the Leslie-Hof in 1684, and furnished it with costly textiles from the Low Countries, most notably a set of verdure hunting tapestries with figures woven from gold and silver threads.Footnote 13 By 1692, Count James was so profoundly associated with the Catholic community in Scotland that he is addressed as ‘Domino ac Patrono nostro Gratiosissimo’ by his kinsman William Aloysius Leslie SJ (1641-1704), who describes himself and his Jesuit colleagues as ‘Patres Societatis Jesu, Missionis Scotiae’ in a remarkable baroque history of the family published as the Laurus Leslaeana. Footnote 14

This Laurus Leslaeanus is a work of considerable interest: seldom has a British Catholic family, successfully established on the continent, set forth their perception of themselves, their position, and their origin with more confidence. It may be reasonably conjectured that the contents of the Laurus accord to a considerable degree with the version of their own history that would have been put into circulation in central Europe when Walter Leslie was raised to the nobility of the Empire. As well as emphasising the family’s Catholicism, especially the connection to John Leslie (1527-96), last Catholic bishop of Ross and apologist for Mary Queen of Scots, the Laurus emphasises the military successes of both Catholic and Protestant branches of the family, claiming that Leslies simultaneously held commands in Scotland, Muscovy and GermanyFootnote 15 . Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the book is that it claims a central European origin for the Leslies, as well as continuous connections with central Europe throughout the middle ages. It is not uncommon for Scottish elite families to attribute their origins to a specific warrior arriving from outside the borders of the Kingdom of Scotland as recently as the 1200s; logically, this suggests that early modern Scots in general—and certainly those of noble rank—would have seen Scotland to some degree as a ‘nation of immigrants,’ and themselves as personally linked to one or more specific other European countries. In the case of the Leslies, there is a suggestion of a very long and perhaps unbroken tradition of military activity in what might be broadly termed the Hungarian or anti-Ottoman interest. The account of origins offered by the Laurus Lesleiana is a great deal simpler and more immediate than the extraordinary world-history offered in the genealogy of their Aberdeenshire neighbours, the Urquharts of Cromarty (latterly, of Craigston) as set forth in 1652 in the ΠΑΝΤΟΧΡΟΝΟΧΑΝΟΝ by Sir Thomas Urquhart, which begins with the creation of red earth by God the Father, Son and Holy Ghost and finally gets the Urquharts to Scotland forty one generations later via the sister of Hiber (who gave his name to Hibernia) and Scota the daughter of Pharaoh (from whom the Urquharts are descended in the female line).Footnote 16

The first ancestor claimed for the Leslies is Bartolf (or Berthold or Bartholomaeus) the Hungarian, who is said to have accompanied St Margaret of Scotland from Hungary to England and thence to Scotland. He is claimed as a direct founder of the Leslie fortunes by standing in such high regard with King Malcolm that, as well as being knighted and made Keeper of Edinburgh Castle, he was granted lands in those parts of Scotland where branches of the Leslies were to become established: Fife, Angus, the Mearns, Cushnie in Mar and Leslie in the Garioch.Footnote 17 Perhaps because he was writing in exile, the earliest Scottish evidence for the history of the family which William Leslie can produce is a fragment of a ballad:

Between the Lesse Ley and the Mair

He slue the Knight and left him there.Footnote 18

He also leaves an honourable central European origin open for the name, by advancing a possible alternative derivation from Ladislaus.Footnote 19 The Victorian historian of the family, Colonel Charles Leslie of Balquhain, accepted the Bartolf narrative and accepted a date of 1067 for his arrival in Scotland and 1121 for his death.Footnote 20 He also accepts almost all of the account offered of the Balquhain branch of the family (although he is intensely sceptical of the account offered of the Rothes branch) especially the emphasis on continuous military service abroad. Bartolf’s grandson Malcolm was killed on crusade in the twelfth century, and a great-great grandson, Leonard, ‘went to the wars abroad’ in the thirteenth.Footnote 21 Norman de Leslie was reportedly in the party that conveyed King Robert Bruce’s heart to the Holy Land in 1330,Footnote 22 and Walter Leslie, fourth son of the sixth laird, ‘served in the Imperial army under the emperors Louis IV and Charles IV (1346-1378), with great distinction, against the Saracens [… and went] to the wars in Germany in 1356.’Footnote 23 This same Walter Leslie later served in the army of King Charles V of France, and received an annuity of 200 gold francs for his services against the English at the 1370 Battle of Pontvallain.Footnote 24

Moving towards the time of the Reformation, it becomes possible to trace something of the religious and political position of the Leslies. The generally accepted version is the one set forth by David McRoberts in his classic article on the Fetternear Banner:

In the wholesale alienation of ecclesiastical property which was such a marked feature of sixteenth-century Scotland, the barony of Fetternear with its castle and pertinents passed from the bishopric of Aberdeen into the possession of the family of Leslie of Balquhain. The Leslies of Balquhain retained possession of the Fetternear lands from that time down to the present century. . . The Leslies of Balquhain, unlike many other beneficiaries of the sixteenth-century economic revolution, maintained their adherence to the Old Faith, and, under their protection, the lands of Fetternear, lying between Bennachie and the Don, have ever remained a traditionally Catholic district.Footnote 25

However, this needs to be balanced by the evidence which David Worthington advances for Walter Leslie having been Protestant in youth. It is a period and society in which it is a complex undertaking to trace religious confession with any precision. George Gordon, Earl of Huntly, took a thirteen-year lease of the ‘barony and shire of Fetternear’ from William Gordon, Bishop of Aberdeen, in 1549.Footnote 26 A little less than eighteen months later, however, the same bishop leased the same lands to John, 8th Baron Leslie of Balquhain, for nineteen years at approximately the same annual rent as before.Footnote 27 It is not easy to reconstruct this sequence of events, but the general implication would seem to be that valuable church property was being placed in the hands of sympathetic Catholic laymen at a time of heightened tension. John, 5th Baron Leslie of Leslie, was an ally of the Gordons in the Scottish Wars of Religion.Footnote 28 William, 9th Baron Leslie of Balquhain,

afforded great assistance to the Bishop of Aberdeen in protecting the cathedral from the ravages of the Reformers, and […] supported the bishop in his diocese when all other bishops in Scotland were persecuted.

It appears to be in gratitude for this that the bishop granted William Leslie the barony, palace, fortalice and tower of Fetternear in 1566.Footnote 29 Remarkably, this ownership was confirmed by both King James VI, in 1602, and Pope Clement X in 1670.Footnote 30

While members of the family, like many Aberdeenshire gentry Catholics, conformed to the Protestant church at times of conflict and crisis, or simply to secure employment with the army of a reformed state,Footnote 31 there can be little doubt of the religious position which Patrick, Count Leslie (15th Baron of Balquhain) expressed in stone by the time that he took possession of Fetternear in 1690.Footnote 32 He seems to have gone out of his way to proclaim not only his foreign title—with a Count’s coronet over the substantial carving of his and his wife’s arms over the central door—but also Roman Catholic devotion in lettered panels with I.H.S. and M.R.A. [Maria Regina Angelorum].Footnote 33 It is at this point that the Fetternear vestments would appear to have been sent to Scotland:

Count Patrick Leslie fitted up the mansion-house of Fetternear in a magnificent manner, and furnished and adorned it with a valuable collection of pictures and objects of art which were sent to him from Germany by his uncle, Count Walter Leslie, by his brother, Count James, and by his son, Count James Ernest. Many of these articles had been taken from the Turks, by Count James Leslie, during the siege of Vienna in 1683, and in other battles in which he defeated them. Amongst them were pieces of rich silk and gold and silver brocade stuffs, which were made into church vestments, and some of which still remain at Fetternear.Footnote 34

II

Having established something of the context, we can now turn to those vestments made of gold and silver brocade, and captured Turkish armoury, which Count James Leslie sent back to the family estates after the siege of Vienna. Over the years, most of the vestments have been displenished or disappeared but one High Mass set seems to have survived at Fetternear, where the pre-reformation ‘Fetternear banner’ (an unfinished sixteenth century embroidered banner for a confraternity of the Holy Blood, probably that at St Giles’s in Edinburgh) was also preserved. On display in the Blairs Museum, a magnificent chasuble lies in one of the drawers of the old vestment chest where it is labelled as ‘The Fetternear Vestment’. It came to Blairs College, the former Scottish Junior Seminary as part of a bequest made by the last Leslie laird in 1921 when he left such items as were then in its possession to the Diocese of Aberdeen. The vestment can be identified in photographs of the opening of the new buildings in 1901, so it must have been in the possession of the church by then and the Leslie provenance would appear to be established.

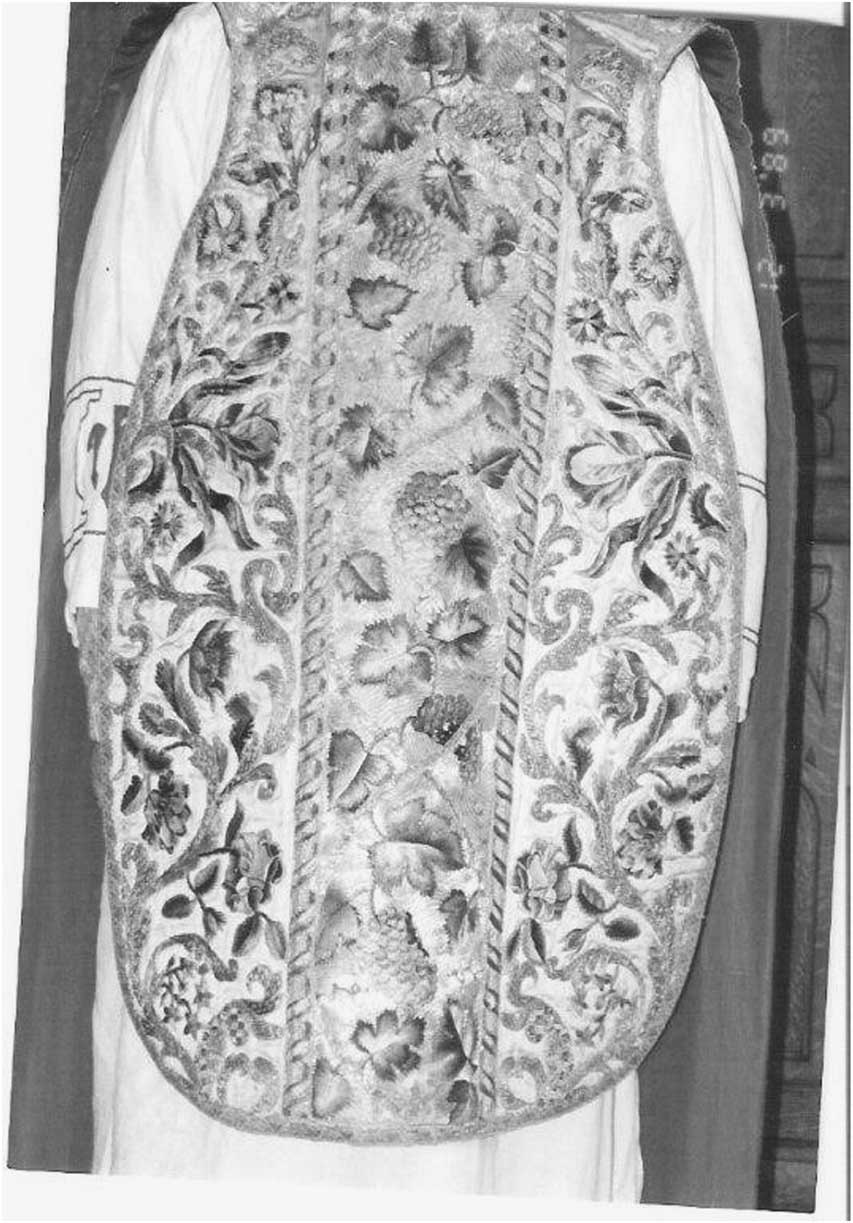

Figure 1 Chasuble and dalmatic (late c17, central European) formerly at Fetternear, Aberdeenshire. Blairs Museum, Aberdeen. Image courtesy of Ian Forbes/Blairs Museum.

What of the other features of the vestment (and its companions)? Do they substantiate the claim to be the vestments sent back after 1693 which are listed in an inventory as being made from the ‘spoil of the Moslem army defeated at Vienna?’Footnote 35 A case can most certainly be made for it if the techniques and materials, especially of the chasuble (Figure 1), are examined.

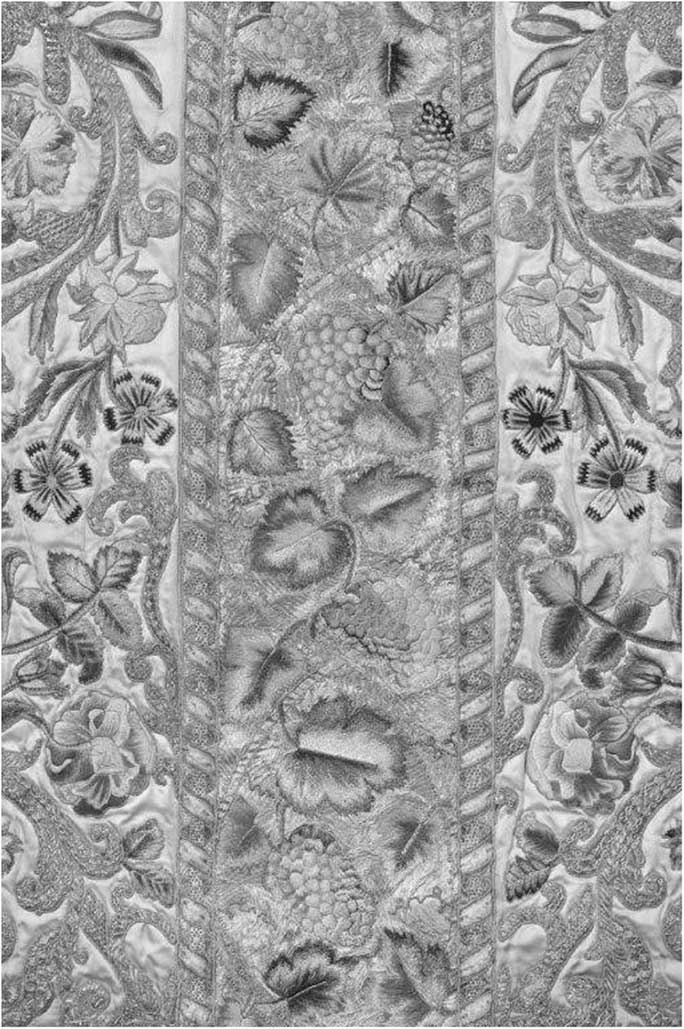

Figure 2a Fetternear Chasuble, front. Late c17, central European embroidery, incorporating re-used Turkish goldwork. Image courtesy of Ian Forbes/Blairs Museum.

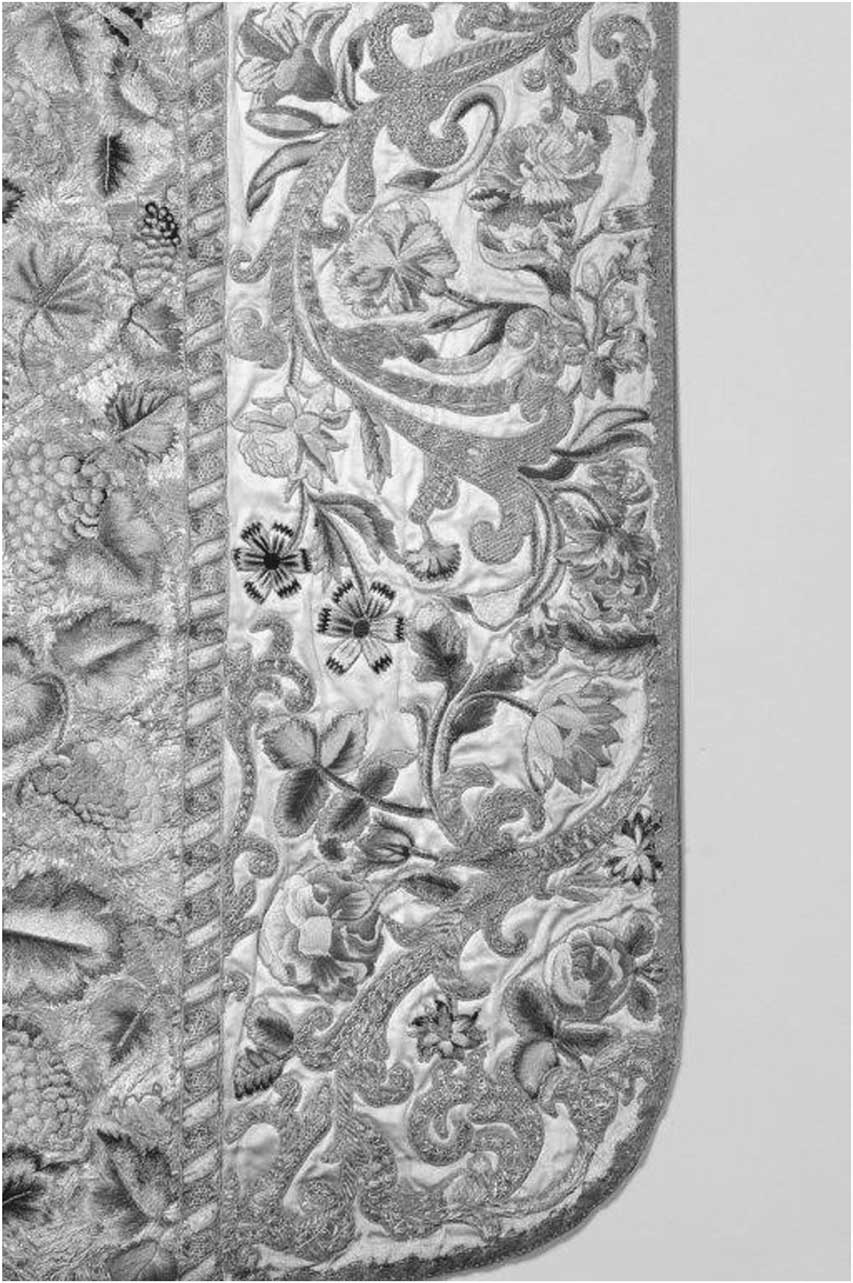

Figure 2b Fetternear Chasuble, back. Late c17, central European embroidery, incorporating re-used Turkish goldwork. Image courtesy of Ian Forbes/Blairs Museum.

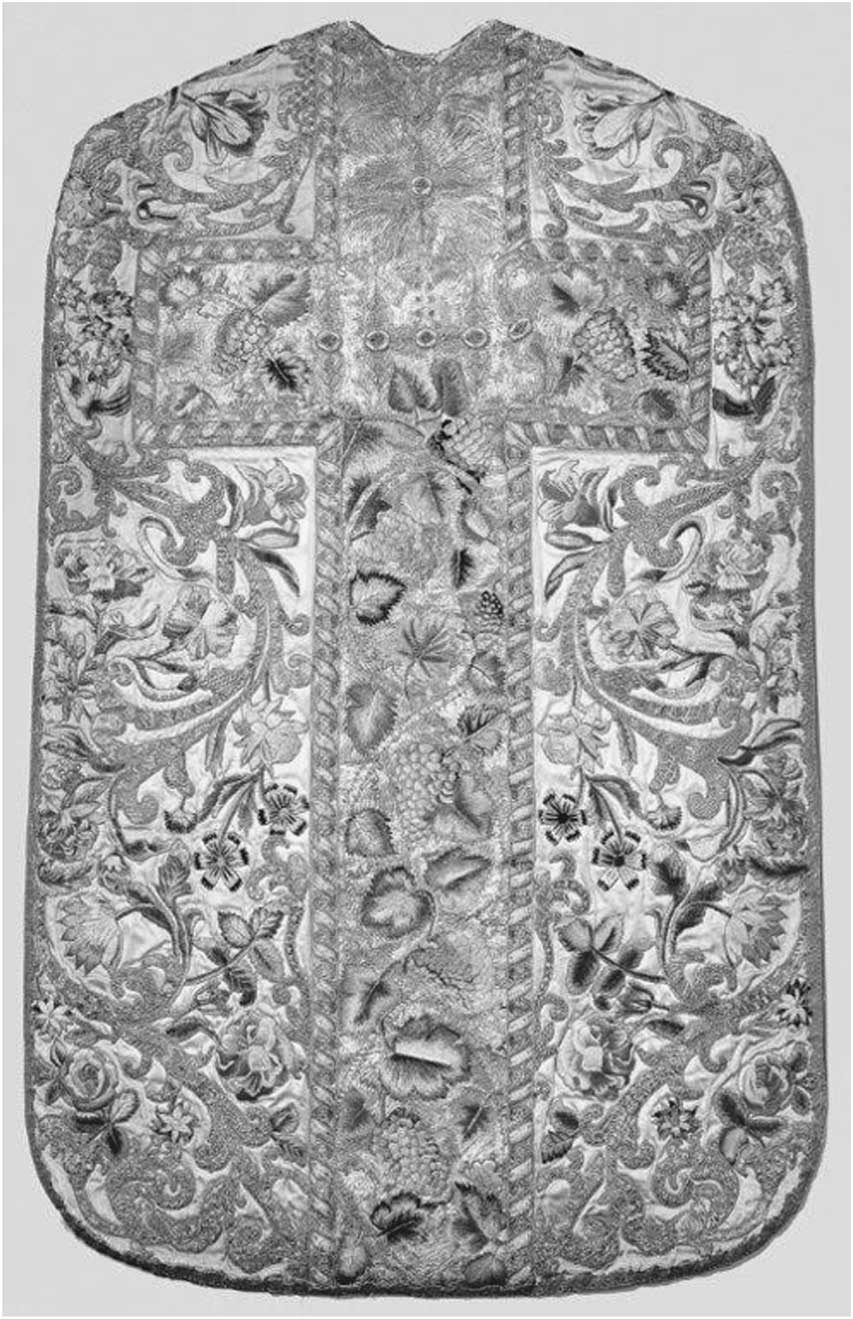

The vestments comprise a richly embroidered chasuble in the Baroque style, two dalmatics, two stoles and two maniples, but the most interesting item is the chasuble, which will be the main focus of this article (Figures 2a and 2b). It is of the Roman or Latin shape with a ground of white satin, covered in embroidered flowers worked in polychrome silks and interspersed with padded gold-work. The orphreys are silk embroidered vine leaves and clusters of grapes embroidered over a background of laid couched silver thread; a pillar orphrey to the front and a cross orphrey to the back. The back orphrey also has the sacred monogram IHS in the form customary on the badge of the Society of Jesus with a cross surmounting the H. The monogram has heavily padded areas giving a raised effect. Both orphreys are edged with an embroidered strip of even basket couching in metal threads and silk work, resembling a braid or heavy ribbon (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Fetternear Chasuble, detail of front pillar orphrey. Image courtesy of Ian Forbes/Blairs Museum.

The silver work on the orphreys has been likened to South German work, and there are similar examples on part of a frontal in the Marienkirche in Lübeck and a chasuble in the Cathedral of Frankurt am Main which bears the arms of the Thurn und Taxis family.Footnote 36 There was an Ursuline convent at Neuburg am Donau which was noted for its metal thread work, but the Ursulines more generally seemed to have been fond of working with metal threads, and there was an Ursuline convent established by Eleanora Gonzaga, the wife of Emperor Ferdinand III in 1663 in Vienna. An outstanding example of their work, the Rosenornat chasuble can be seen in the Museum für angewandte Kunst in Vienna.Footnote 37 It is of gold, silver and coloured silk embroidery on a ground of laid silver work. Comparison suggests that perhaps the orphreys were worked in Vienna. (Interestingly, there is a slight difference between the orphreys on the chasuble and those on the dalmatics.)

Figure 4a Detail of the Fetternear Chasuble, showing central European flower embroidery, Image courtesy of Ian Forbes/Blairs Museum.

Figure 4b The Pázmány Chasuble (c17, central European) Cathedral of Estergom, Hungary. Image courtesy of Dr Marta Járó, Budapest.

The silk flowers on the chasuble were worked as “slips” individually on to linen and then laid on the satin ground, being edged up with a fine silver cord. The flowers are obviously European work and consist of examples of roses, lilies, tulips, cornflowers; the polychrome silks still stunning in their brilliance. The immediate assumption would be that they were worked in the same convent workshop, but interestingly the flowers bear a strong similarity to the Pázmány Chasuble in the Cathedral of Estergom in Hungary (Figures 4a and 4b).Footnote 38 In the seventeenth century the Holy Roman Empire included a considerable tranche of central Europe beyond the German-speaking countries, and the Leslies owned estates at Ptuj in what is now Slovenia, so a Hungarian origin for some elements of the embroidery seems wholly possible. It seems therefore equally possible that there could have been Sisters of Hungarian origin in whichever convent worked the embroideries.

It is the gold work on the chasuble which can finally be identified as “the Turkish or Moslem armoury.” There are Turkish saddles in the Esterházy collection in the Iparművészeti Museum in Budapest and there is one in Krakow in Wawel Royal Castle. The elaborate saddles and the caparisons of warhorses were not merely for ornamental purposes; their use was protective to prevent the mounts being slashed and so debilitated. Heavily embroidered cloths with metal-work in the embroidery allowed for ease of movement, whilst preventing superficial injury to the horse by deflecting the sword blades.Footnote 39 All of this explains where the gold work may have been obtained, but where did it originate and how can it be identified?

There was a fraternity of Turkish gold work embroiderers, the Cemaat-i Zerduzan established in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. Their work was used to cover saddles, quivers, bow bags, garments and furnishings.Footnote 40 Like the opus anglicanum embroiderers of medieval England theirs was an all-male guild. At the time their main skills were zerzud which was couching in gold threads, dival which is known in Europe as guipure (and which became popular in the west around the turn of the eighteenth century) and sama, a satin stitch worked in gold. As well as working on cloth, the zerduzans also worked on leather, but it is their work on fabric which appears on the Fetternear vestment in the form of scrolling and stylised arabesques. Elaborate patterns of stitching in metal thread of gold and silver have been worked over areas padded with silk work. These would have been carefully eased from their original ground and laid as slips on to the chasuble and have been edged up with the same fine silver cord as the slips with flowers.

Figure 5 Detail of the wound metallic thread known as Passing. Image courtesy of Prue King, Blairs Museum.

The skills of the workers are shown in the variety of their stitch work. Fine passing (Figure 5) is wire wrapped round a silk core and thin enough to be used to stitch through fabric. It is used in many ways:

Diagonal mesh, strands of three fine threads laid criss-cross in a diamond pattern.

Larger couched areas with a variety of stitches used as filling.

Basket or underside couching.

Cable chain effect, a linked chain.

Stars.

Coils, like miniature rope coils in the centre of flower designs.

Herringbone effect, double back stitch, like frogging.

Figures of eight, linked and alternated with coils in a continuous line.

Squares with a central coil.

Verticals and diagonals, like modern Turkish musabak stitch, with an oblong filling.

Gold plate, flat metal with a ribbon effect (Figure 6), laid in strips over a padded silk ground, tied down with diagonals of fine thread and topped with coils and scrolls and musabak of passing. ‘It added lightness and texture to the embroidery and a touch of brilliance when worked in metal thread and plate.’Footnote 41 It is this last which characterises it as being of Turkish work. It was one of the highly prized crafts in Ottoman times.

Figure 6 Detail of the flat metallic ribbon known as Plate. Image courtesy of Prue King, Blairs Museum.

The use of plate was not common in European work at the time, and it resembles a modern Turkish embroidery called tel kakma which has been undergoing something of a revival recently. The plate would have been hammered to get it to lie smooth and flat.

The Fetternear chasuble goldwork is all made from passing and plate: there is none of the bullion which forms the basis for so much more modern work, with its smooth and rough purls and its check metal wire threads. The artistry of the worker has to be seen to be believed, it is no wonder that their work was so highly prized and that to be a Zerduzan was to have achieved the height of one’s profession.

Mention was made of a difference in the orphreys on the chasuble and those on the dalmatics. The laid silver work ground on the chasuble varies in direction, as though to accommodate the leaves and these have no cord edgings. The silver work on the dalmatic orphreys is much more uniform and it is interesting to note that the grapes and the leaves on them have been laid on as slips, and edged with the same silver cord, while it is impossible to discern whether the silver goes under the leaves and grapes on the chasuble in whole or in part. At times, the silk covers a thread or two of the silver, while at others it appears to run alongside. Two visiting professional embroiderers of many years’ experience found it impossible to decide.

The orphreys on the dalmatics are edged with a narrow silver braid and not the braid effect embroidery of the chasuble. It is interesting to note that the leaves and grapes are the work of different embroiderers; the treatment of the shading of the coloured silks varies despite a certain uniformity. There are no embroidered flowers on the dalmatics, whose background is of woven floral patterned silk brocade, possibly eighteenth century, which allows of the possibility that they are of slightly later date and that the orphreys may have been sent to Scotland before being mounted. It is known that orphreys were frequently transported separately as strips, rolled up, making for ease of transport. More research into the background fabric is needed. Interestingly, the stoles and maniples are on the same white satin ground as the chasuble and have flowers as their sole decoration apart from Latin and saltire crosses, braid and fringe. Some of the flowers are of a higher standard than others, but they are all beautiful and still exquisitely coloured.

In conclusion, a case has been made for the possible provenance of the various elements which make up the Fetternear chasuble and dalmatics, but it can only be conjecture. It is possible that Count James Leslie commissioned the central-European Ursuline Sisters to make a vestment using the embroideries captured from the Turkish officers whilst incorporating their own specialist skills and this is the result. It may be the sole survivor of several items of the same sort, indeed this is the implication of Colonel Leslie’s Historical Records of the Family of Leslie Footnote 42 which records dispersals of the rich furnishings of Fetternear throughout the eighteenth century. Between 1715 and 1720, in the wake of the Jacobite rising of 1715, chapel furnishings and vestments were sold by the Hon. Margaret Elphinstone, Protestant widow of Count Patrick Leslie’s son George, due to the fact that she ‘shared in the bitter anti-Catholic spirit of the times.’ One of the buyers was James Gordon of Cowbairdy, a younger son of Sir James Gordon of Park.Footnote 43 After the second Jacobite rising, in 1762, an officer in the Dutch army named Peter Leslie-GrantFootnote 44 sued his distant relative Anthony, Count Leslie, for possession of Fetternear and Balquhain, on the grounds that the latter was ‘a Papist and an alien’; the House of Lords found in Leslie-Grant’s favour, but he had only lived in the house for six years when, ‘much pressed for money’, he leased it to a Edinburgh lawyer named Orme.Footnote 45

Many of the records of the family were lost when Fetternear House, the former summer palace of the Bishops of Aberdeen, burned to the ground in the 1920s.Footnote 46 Happily the vestment was already in the possession of the Diocese of Aberdeen when it did, or there would be nothing left for our conjecture and wonder and amazement. How much else was lost cannot now be assessed. The composite nature of the vestment, Turkish goldwork and central European embroidery, accords very closely with the image of themselves and of their antecedents projected by the late seventeenth-century Counts Leslie – as long-time guardians of the eastern frontier of Europe, from whence they derived their own origin. The vestment is the combination of the spoils of war and the labours of the Ursuline Sisters, amongst whom there many well have been Hungarians. Much more of the Leslie inheritance is now preserved in Slovenia than in Scotland, although the Leslies were instrumental in preserving two of the finest Roman Catholic material objects in Scotland from before and after the Reformation.