1. Introduction

Dust storms pose a unique opportunity to study particle-laden turbulent flows at extremely high-Reynolds numbers. Several physical mechanisms, including cleavage/fractoelectrification, bombardment charging, pyroelectrification, piezoelectrification, polarisation by Earth’s atmospheric electric field, triboelectrification and contact electrification (Kanagy & Mann Reference Kanagy and Mann1994; Zheng Reference Zheng2013), are believed to cause dust particles to acquire a substantial charge, thereby generating electric fields with intensities exceeding

![]() $100$

kV m

$100$

kV m

![]() $^{-1}$

(e.g. Rudge Reference Rudge1913; Stow Reference Stow1969; Schmidt, Schmidt & Dent Reference Schmidt, Schmidt and Dent1998; Shinbrot & Herrmann Reference Shinbrot and Herrmann2008; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Nathou, Hicks, Pontikis, Russell, Miller and Bartholomew2009; Zhang & Zhou Reference Zhang and Zhou2020; Rahman, Cheng & Samtaney Reference Rahman, Cheng and Samtaney2021). Consequently, in addition to the particle–turbulence couplings in ordinary particle–laden turbulent flows, particle–electrostatics couplings also play a crucial role (e.g. Zheng, Huang & Zhou Reference Zheng, Huang and Zhou2003; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Nordsiek, Saw and Shaw2010; Karnik & Shrimpton Reference Karnik and Shrimpton2012; Zheng Reference Zheng2013; Grosshans & Papalexandris Reference Grosshans and Papalexandris2017; Zhang, Cui & Zheng Reference Zhang, Cui and Zheng2023).

$^{-1}$

(e.g. Rudge Reference Rudge1913; Stow Reference Stow1969; Schmidt, Schmidt & Dent Reference Schmidt, Schmidt and Dent1998; Shinbrot & Herrmann Reference Shinbrot and Herrmann2008; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Nathou, Hicks, Pontikis, Russell, Miller and Bartholomew2009; Zhang & Zhou Reference Zhang and Zhou2020; Rahman, Cheng & Samtaney Reference Rahman, Cheng and Samtaney2021). Consequently, in addition to the particle–turbulence couplings in ordinary particle–laden turbulent flows, particle–electrostatics couplings also play a crucial role (e.g. Zheng, Huang & Zhou Reference Zheng, Huang and Zhou2003; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Nordsiek, Saw and Shaw2010; Karnik & Shrimpton Reference Karnik and Shrimpton2012; Zheng Reference Zheng2013; Grosshans & Papalexandris Reference Grosshans and Papalexandris2017; Zhang, Cui & Zheng Reference Zhang, Cui and Zheng2023).

Depending on the flow characteristic parameters, turbulence–particle–electrostatics couplings can be categorised into several regimes. Concerning turbulence–particle couplings, when the particle mass loading is low, the influence of particles on turbulence can be disregarded, which is referred to as a one-way coupling regime. When the particle mass loading is high and the volume fraction is small, turbulence is significantly affected by particles, which is referred to as a two-way coupling regime. When both the mass loading and volume fraction of particles are high enough, particle collisions occur, forming a four-way coupling regime (Elghobashi Reference Elghobashi1994; Balachandar & Eaton Reference Balachandar and Eaton2010; Brandt & Coletti Reference Brandt and Coletti2022). Regarding particle–electrostatics couplings, when the electrostatic Stokes number of particles is small (or large), particle dynamics is dominated by the inertial (or electrostatic) effects of particles (Grosshans et al. Reference Grosshans, Bissinger, Calero and Papalexandris2021; Boutsikakis, Fede & Simonin Reference Boutsikakis, Fede and Simonin2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Cui and Zheng2023). In dust storms, the dust concentration decreases exponentially with height (McGowan & Clark Reference McGowan and Clark2008; Zheng Reference Zheng2009). As a result, the mass loading of particles is low at locations far from the wall, allowing the turbulence modulation by particles to be neglected. In contrast, close to the wall, both the mass loading and electrostatic Stokes number of particles are large, indicating a strong turbulence–particle–electrostatics coupling (Zhang & Zhou Reference Zhang and Zhou2023), which warrants special attention. It is widely recognised that such strong multifield couplings have pronounced effects on particle transport and aggregation (Lu et al. Reference Lu, Nordsiek, Saw and Shaw2010; Karnik & Shrimpton Reference Karnik and Shrimpton2012; Lu & Shaw Reference Lu and Shaw2015; Boutsikakis et al. Reference Boutsikakis, Fede and Simonin2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Cui and Zheng2023; Ruan, Gorman & Ni Reference Ruan, Gorman and Ni2024), turbulence modulation (Cui, Zhang & Zheng Reference Cui, Zhang and Zheng2024), the charging properties of particles (Grosshans & Papalexandris Reference Grosshans and Papalexandris2017; Jantač & Grosshans Reference Jantač and Grosshans2024) and the formation of turbulent electric fields (Di Renzo & Urzay Reference Di Renzo and Urzay2018).

One of the major characteristics of dust storms is the significant small-scale intermittency in multiple fields, including wind velocity, the mass concentration of dust particles smaller than 10

![]() $\unicode {x03BC}$

m (hereafter, PM10 dust concentration) and electric field (Zhang, Tan & Zheng Reference Zhang, Tan and Zheng2023). Intuitively, the time series of these fields displays intense sporadic local fluctuations. Statistically, the probability density function of the increments in these fields deviates increasingly from the Gaussian distribution as the scale decreases (i.e. the flatness increases and exceeds three with decreasing scale), and the high-order structure functions deviate from Kolmogorov linear scaling. Compared to clean-air conditions, the intermittency of wind velocity in dust storms is significantly enhanced at small scales, while it remains largely unchanged at large scales. This may be due to high concentrations of dust particles injecting velocity fluctuations at small scales in the near-surface region (Horwitz & Mani Reference Horwitz and Mani2020). Notably, at 5 m above the surface, the intermittency of PM10 dust concentration is the strongest in dust storms, followed by the electric field, with wind velocity showing the least intermittency. In short, compared with the traditional Fourier transform, the wavelet analysis is more suitable for analysing multifield data series recorded in dust storms. This is because the Fourier transform analyses the entire time series globally and provides characteristics in a time-averaged sense, while the wavelet transform provides both time and frequency information (e.g. Meneveau Reference Meneveau1991; Daubechies Reference Daubechies1992; Farge Reference Farge1992; Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Torrence & Compo Reference Torrence and Compo1998; Zhou Reference Zhou2021), effectively extracting and characterising intermittent events.

$\unicode {x03BC}$

m (hereafter, PM10 dust concentration) and electric field (Zhang, Tan & Zheng Reference Zhang, Tan and Zheng2023). Intuitively, the time series of these fields displays intense sporadic local fluctuations. Statistically, the probability density function of the increments in these fields deviates increasingly from the Gaussian distribution as the scale decreases (i.e. the flatness increases and exceeds three with decreasing scale), and the high-order structure functions deviate from Kolmogorov linear scaling. Compared to clean-air conditions, the intermittency of wind velocity in dust storms is significantly enhanced at small scales, while it remains largely unchanged at large scales. This may be due to high concentrations of dust particles injecting velocity fluctuations at small scales in the near-surface region (Horwitz & Mani Reference Horwitz and Mani2020). Notably, at 5 m above the surface, the intermittency of PM10 dust concentration is the strongest in dust storms, followed by the electric field, with wind velocity showing the least intermittency. In short, compared with the traditional Fourier transform, the wavelet analysis is more suitable for analysing multifield data series recorded in dust storms. This is because the Fourier transform analyses the entire time series globally and provides characteristics in a time-averaged sense, while the wavelet transform provides both time and frequency information (e.g. Meneveau Reference Meneveau1991; Daubechies Reference Daubechies1992; Farge Reference Farge1992; Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Torrence & Compo Reference Torrence and Compo1998; Zhou Reference Zhou2021), effectively extracting and characterising intermittent events.

Previous studies have focused on utilising cospectral analysis to investigate the time-averaged linear coupling behaviour in dust storms. For instance, Wang, Zheng & Tao (Reference Wang, Zheng and Tao2017) performed cospectral analysis between the PM10 dust concentration and wind velocity during dust storms. Their findings indicated that low-speed very large-scale motions (VLSMs) reduce the upward flux of PM10 in the logarithmic layer, while high-speed VLSMs enhance the downstream and upward transport of PM10 in higher regions. Subsequently, Zhang & Liu (Reference Zhang and Liu2023) examined the influence of electric fields on dust transport in dust storms using the cospectrum between PM10 dust concentration and electric field. The results demonstrated that electric fields significantly promote PM10 transport at the kilometer-sized synoptic scale, have a secondary inhibitory effect at the hectometer-sized VLSM scale, and exhibit negligible effects at the decameter-sized turbulent integral scale. Similarly, in wind-tunnel blowing snow experiments, Paterna, Crivelli & Lehning (Reference Paterna, Crivelli and Lehning2016) analysed the cospectrum between measured wind velocity and particle mass flux to explore the effects of turbulence on snow particle entrainment. They identified two regimes of snow particle saltation: (a) a turbulence-dependent regime, where turbulence directly regulates weak saltation; (b) a turbulence-independent regime, where strong saltation develops its own length scale independent of turbulence forcing. Besides linear coupling, various phenomena such as the transition to turbulence, transitions from one turbulence regime to another (Monsalve et al. Reference Monsalve, Brunet, Gallet and Cortet2020) and energy transfer between different spectral components (Ritz & Powers Reference Ritz and Powers1986) can be explained only by the nonlinearity of turbulent flows. Bispectral analysis, as introduced by Hasselmann, Munk & MacDonald (Reference Hasselmann, Munk and MacDonald1963) is an effective method to evaluate quadratic phase coupling in the frequency triad

![]() $f_1$

,

$f_1$

,

![]() $f_2$

and

$f_2$

and

![]() $f_1+f_2$

. Note that quadratic phase coupling is also referred to as three-wave coupling or triadic interactions in the literature (see e.g. Agnon & Sheremet Reference Agnon and Sheremet1997; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Wan, Song and Li2003; Biferale, Musacchio & Toschi Reference Biferale, Musacchio and Toschi2012; Monsalve et al. Reference Monsalve, Brunet, Gallet and Cortet2020). Strong quadratic coupling processes have been shown to be responsible for spectral energy redistribution (e.g. Elgar & Guza Reference Elgar and Guza1985; Ritz & Powers Reference Ritz and Powers1986; Dudok de Wit & Krasnosel’skikh Reference Dudok de Wit and Krasnosel’Skikh1995), leading to a smoother (Bountin, Shiplyuk & Maslov Reference Bountin, Shiplyuk and Maslov2008) or broader (Unnikrishnan & Gaitonde Reference Unnikrishnan and Gaitonde2020) power spectral density (PSD). Despite its paramount importance, bispectral characteristics in dust storms, especially for PM10 concentration and electric field, have not been explored previously.

$f_1+f_2$

. Note that quadratic phase coupling is also referred to as three-wave coupling or triadic interactions in the literature (see e.g. Agnon & Sheremet Reference Agnon and Sheremet1997; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Wan, Song and Li2003; Biferale, Musacchio & Toschi Reference Biferale, Musacchio and Toschi2012; Monsalve et al. Reference Monsalve, Brunet, Gallet and Cortet2020). Strong quadratic coupling processes have been shown to be responsible for spectral energy redistribution (e.g. Elgar & Guza Reference Elgar and Guza1985; Ritz & Powers Reference Ritz and Powers1986; Dudok de Wit & Krasnosel’skikh Reference Dudok de Wit and Krasnosel’Skikh1995), leading to a smoother (Bountin, Shiplyuk & Maslov Reference Bountin, Shiplyuk and Maslov2008) or broader (Unnikrishnan & Gaitonde Reference Unnikrishnan and Gaitonde2020) power spectral density (PSD). Despite its paramount importance, bispectral characteristics in dust storms, especially for PM10 concentration and electric field, have not been explored previously.

In the aforementioned time-averaged coupling analysis, an implicit assumption is that coupling behaviour remains uniform over time. However, owing to the intrinsic intermittency of the various interacting fields in dust storms, it is reasonable to anticipate that both linear and quadratic nonlinear couplings exhibit intermittent behaviour across both temporal and scale domains. In particular, coherent structures, which are highly localised in time and scale (Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Grilliat, Caputi-Gennaro and Jacob2010), give rise to short-lived, sporadic coupling between turbulent fields (Camussi, Robert & Jacob Reference Camussi, Robert and Jacob2008; Bernardini et al. Reference Bernardini, Della Posta, Salvadore and Martelli2023) and are known to contribute significantly to the transport of heat, mass, and momentum (Marusic et al. Reference Marusic, McKeon, Monkewitz, Nagib, Smits and Sreenivasan2010). In this regard, while time-averaged coupling analysis has provided valuable insights into certain multifield interactions in dust storms, this framework is inherently limited in its capacity to capture the critical intermittent coupling dynamics that play a crucial role in these processes.

To elucidate the localised linear and nonlinear coupling characteristics of multiple fields in dust storms, we conducted a series of simultaneous measurements of three-dimensional wind velocity, PM10 dust concentration and electric field at a height of 0.9 m above the surface at the Qingtu Lake Observation Array in 2021. At this measurement height, the particle-to-air mass loading ratio and particle electrostatic Stokes number reached the order of 0.1, indicating significant particle–turbulence and particle–electrostatics couplings. Instead of using a Fourier-based data analysis framework, we adopt a wavelet conditional averaging method based on the local intermittency measure, supplemented by wavelet coherence and bicoherence analyses, to evaluate the multifield localised linear and quadratic nonlinear coupling behaviours.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows: In

![]() $\S$

2, we provide detailed information on the 2021 field measurement set-up and the selected high-fidelity dataset. In

$\S$

2, we provide detailed information on the 2021 field measurement set-up and the selected high-fidelity dataset. In

![]() $\S$

3, we describe the wavelet-based multiple field coupling analysis methods used in this study. The local intermittency, linear coupling and quadratic nonlinear coupling behaviours of multiple fields in dust storms are examined and discussed in detail in

$\S$

3, we describe the wavelet-based multiple field coupling analysis methods used in this study. The local intermittency, linear coupling and quadratic nonlinear coupling behaviours of multiple fields in dust storms are examined and discussed in detail in

![]() $\S$

$\S$

![]() $\S$

4.1–4.4, respectively. Finally, we summarise the main conclusions of this article in

$\S$

4.1–4.4, respectively. Finally, we summarise the main conclusions of this article in

![]() $\S$

5.

$\S$

5.

2. Dataset

2.1. Measurement set-up

Field measurements were conducted from April to June 2021 at the Qingtu Lake Observation Array (QLOA), an atmospheric surface layer turbulence observatory situated between the Badain Jaran Desert and Tengger Desert in China. The dry lake bed of Qingtu Lake, which spans a flat surface covering approximately 20 km

![]() $^2$

, is devoid of roughness elements such as rocks, vegetation and sand dunes. This extensive flat surface ensures that the atmospheric surface-layer flows at the QLOA site can be considered analogous to the canonical turbulent boundary layers over flat plates after performing standard data quality control procedures (see below) (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007; Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012). From April to June, the QLOA site experiences frequent dust storms due to Mongolian cyclones accompanied by strong northwesterly surface winds (Zheng Reference Zheng2009), offering an excellent opportunity to study randomly occurring dust storms.

$^2$

, is devoid of roughness elements such as rocks, vegetation and sand dunes. This extensive flat surface ensures that the atmospheric surface-layer flows at the QLOA site can be considered analogous to the canonical turbulent boundary layers over flat plates after performing standard data quality control procedures (see below) (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007; Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012). From April to June, the QLOA site experiences frequent dust storms due to Mongolian cyclones accompanied by strong northwesterly surface winds (Zheng Reference Zheng2009), offering an excellent opportunity to study randomly occurring dust storms.

The three-dimensional wind velocity components, denoted by

![]() $U$

,

$U$

,

![]() $V$

and

$V$

and

![]() $W$

for the streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions respectively, along with the ambient temperature (

$W$

for the streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions respectively, along with the ambient temperature (

![]() $\varTheta$

), were measured at heights of

$\varTheta$

), were measured at heights of

![]() $z = \{0.5, 0.9, 1.5, 2.5, 3.49, 5, 7.15, 10.24, 14.65, 20.96, 30\}$

m above the surface. Simultaneously, the PM10 dust concentration (

$z = \{0.5, 0.9, 1.5, 2.5, 3.49, 5, 7.15, 10.24, 14.65, 20.96, 30\}$

m above the surface. Simultaneously, the PM10 dust concentration (

![]() $C$

) and electric field (

$C$

) and electric field (

![]() $E$

) were recorded at a height of 0.9 m. Additionally, the size distribution of total airborne dust particles was determined by analysing the particle sample collected at 0.9 m height (Microtrac S3500 tri-laser particle size analyzer, Verder Scientific). At this measurement height, the total particle concentration is sufficiently high to bring about strong turbulence–particle–electrostatics couplings, yet it avoids reaching excessively high particle concentrations that could cause the measurement instruments to cease functioning. Throughout this article, the fluctuating components of the measured physical quantities are represented by lowercase letters

$E$

) were recorded at a height of 0.9 m. Additionally, the size distribution of total airborne dust particles was determined by analysing the particle sample collected at 0.9 m height (Microtrac S3500 tri-laser particle size analyzer, Verder Scientific). At this measurement height, the total particle concentration is sufficiently high to bring about strong turbulence–particle–electrostatics couplings, yet it avoids reaching excessively high particle concentrations that could cause the measurement instruments to cease functioning. Throughout this article, the fluctuating components of the measured physical quantities are represented by lowercase letters

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

,

$v$

,

![]() $w$

,

$w$

,

![]() $\theta$

,

$\theta$

,

![]() $c$

and

$c$

and

![]() $e$

. The wind velocities and ambient temperatures were recorded using sonic anemometers (CSAT3B, Campbell Scientific), PM10 dust concentration was measured using a DustTrak II Aerosol Monitor (Model 8530EP, TSI Incorporated), and the electric field was monitored using an electric field mill (CS110, Campbell Scientific). In addition to the size distribution of total airborne dust particles, all other physical quantities were monitored in real-time. The sampling frequency of CSAT3B is 50 Hz, while that of 8530EP and CS110 is 1 Hz. All instruments were factory calibrated to meet the following specifications: the offset error of the CSAT3B was less than

$e$

. The wind velocities and ambient temperatures were recorded using sonic anemometers (CSAT3B, Campbell Scientific), PM10 dust concentration was measured using a DustTrak II Aerosol Monitor (Model 8530EP, TSI Incorporated), and the electric field was monitored using an electric field mill (CS110, Campbell Scientific). In addition to the size distribution of total airborne dust particles, all other physical quantities were monitored in real-time. The sampling frequency of CSAT3B is 50 Hz, while that of 8530EP and CS110 is 1 Hz. All instruments were factory calibrated to meet the following specifications: the offset error of the CSAT3B was less than

![]() $\pm$

8 cm s

$\pm$

8 cm s

![]() $^{-1}$

; the zero drift of the 8530EP was within

$^{-1}$

; the zero drift of the 8530EP was within

![]() $\pm$

0.002 kg m

$\pm$

0.002 kg m

![]() $^{-3}$

over 24 hours; and the accuracy of the CS110 was

$^{-3}$

over 24 hours; and the accuracy of the CS110 was

![]() $\pm$

5 % of the reading, with a maximum offset of 8 V m

$\pm$

5 % of the reading, with a maximum offset of 8 V m

![]() $^{-1}$

.

$^{-1}$

.

2.2. Dataset description

Since atmospheric flows are uncontrolled, we need to perform a series of rigorous quality control procedures on the observed data to obtain high-fidelity usable data. Firstly, the continuous observations of multiple fields over two months were divided into a series of one-hour datasets. Subsequently, stationarity and stratification stability parameters were calculated for each one-hour dataset. The stationarity of a time series was assessed using the relative non-stationarity parameter (

![]() $RNP$

), which is defined as the relative difference between the variance of the entire time series and the mean variance of its 12 contiguous 5-minute subsequences. A time series is considered broadly stationary if

$RNP$

), which is defined as the relative difference between the variance of the entire time series and the mean variance of its 12 contiguous 5-minute subsequences. A time series is considered broadly stationary if

![]() $RNP \leqslant 0.3$

(Foken & Wichura Reference Foken and Wichura1996), and such series were used for the subsequent data analysis in this study. Notably, a time series is regarded as strongly stationary if all possible moments and joint moments remain invariant over time (Bendat & Piersol Reference Bendat and Piersol2011). However, for atmospheric surface layer data, achieving strong stationarity is challenging due to diurnal variations (synoptic scale) and the limited occurrence of neutral stability conditions (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007).

$RNP \leqslant 0.3$

(Foken & Wichura Reference Foken and Wichura1996), and such series were used for the subsequent data analysis in this study. Notably, a time series is regarded as strongly stationary if all possible moments and joint moments remain invariant over time (Bendat & Piersol Reference Bendat and Piersol2011). However, for atmospheric surface layer data, achieving strong stationarity is challenging due to diurnal variations (synoptic scale) and the limited occurrence of neutral stability conditions (Hutchins & Marusic Reference Hutchins and Marusic2007).

The stratification stability of the wind flow was evaluated using the Monin–Obukhov stability parameter,

![]() $z/L$

. Here,

$z/L$

. Here,

![]() $L = -\langle \varTheta \rangle _t u_\tau ^3/(\kappa g (\langle w \theta \rangle _t)_0)$

is the Obukhov length,

$L = -\langle \varTheta \rangle _t u_\tau ^3/(\kappa g (\langle w \theta \rangle _t)_0)$

is the Obukhov length,

![]() $\kappa = 0.41$

is the von Kármán constant,

$\kappa = 0.41$

is the von Kármán constant,

![]() $g = 9.81$

m s

$g = 9.81$

m s

![]() $^{-2}$

is gravitational acceleration, and

$^{-2}$

is gravitational acceleration, and

![]() $(\langle w \theta \rangle _t)_0$

represents the surface heat flux. As done in numerous previous studies (e.g. Klewicki, Priyadarshana & Metzger Reference Klewicki, Priyadarshana and Metzger2008; Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012; Chowdhuri, Kumar & Banerjee Reference Chowdhuri, Kumar and Banerjee2020), the friction velocity was calculated as

$(\langle w \theta \rangle _t)_0$

represents the surface heat flux. As done in numerous previous studies (e.g. Klewicki, Priyadarshana & Metzger Reference Klewicki, Priyadarshana and Metzger2008; Hutchins et al. Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012; Chowdhuri, Kumar & Banerjee Reference Chowdhuri, Kumar and Banerjee2020), the friction velocity was calculated as

![]() $u_\tau = (\langle u w \rangle _t^2 + \langle v w \rangle _t^2)^{1/4}$

at

$u_\tau = (\langle u w \rangle _t^2 + \langle v w \rangle _t^2)^{1/4}$

at

![]() $z = 1.5\,\rm m$

. When

$z = 1.5\,\rm m$

. When

![]() $|z/L| \leqslant 0.1$

, the wind flow is approximately neutrally stratified, and thermal buoyancy effects are negligible (Kunkel & Marusic Reference Kunkel and Marusic2006).

$|z/L| \leqslant 0.1$

, the wind flow is approximately neutrally stratified, and thermal buoyancy effects are negligible (Kunkel & Marusic Reference Kunkel and Marusic2006).

Following the aforementioned data quality control procedures, nine sets of high-fidelity one-hour data were selected for analysis in this study, consisting of eight dust storm datasets and one clean-air dataset. The main parameters of these datasets are outlined in table 1. For the clean-air dataset, the mean electric field was negative (i.e. downward-pointing) with a magnitude of approximately

![]() $0.21$

kV m

$0.21$

kV m

![]() $^{-1}$

. In contrast, during dust storms, the mean electric field was positive (i.e. upward-pointing) and reached magnitudes of several tens of kilovolts per meter, indicating intense electrical activity.

$^{-1}$

. In contrast, during dust storms, the mean electric field was positive (i.e. upward-pointing) and reached magnitudes of several tens of kilovolts per meter, indicating intense electrical activity.

Table 1. Overview of the used one-hour datasets. Here, ‘0428/14–15’ (similarity for others) denotes this dataset was taken on April 28, 2021 at 14: 00–15:00 UTC + 8,

![]() $U_c= \langle U \rangle _t$

is the convection velocity,

$U_c= \langle U \rangle _t$

is the convection velocity,

![]() $u_\tau$

is the friction velocity,

$u_\tau$

is the friction velocity,

![]() $\langle \varTheta \rangle _t$

is the mean ambient temperature,

$\langle \varTheta \rangle _t$

is the mean ambient temperature,

![]() $\langle C \rangle _t$

is the mean PM10 dust concentration,

$\langle C \rangle _t$

is the mean PM10 dust concentration,

![]() $\langle E \rangle _t$

is the mean electric field,

$\langle E \rangle _t$

is the mean electric field,

![]() $RNP$

is the relative non-stationarity parameter of the streamwise wind velocity,

$RNP$

is the relative non-stationarity parameter of the streamwise wind velocity,

![]() $z/L$

is the Monin–Obukhov stability parameter of the wind flow,

$z/L$

is the Monin–Obukhov stability parameter of the wind flow,

![]() $\varPhi _m$

is the particle-to-air mass loading ratio,

$\varPhi _m$

is the particle-to-air mass loading ratio,

![]() $\overline {St_{el}}$

is the mean electrostatic Stokes number, and

$\overline {St_{el}}$

is the mean electrostatic Stokes number, and

![]() $St^+$

is the viscous Stokes number of the 10-

$St^+$

is the viscous Stokes number of the 10-

![]() $\unicode {x03BC}$

m-diameter dust particles.

$\unicode {x03BC}$

m-diameter dust particles.

Furthermore, the particle-to-air mass loading ratio (

![]() $\varPhi _m$

) and the mean electrostatic Stokes number (

$\varPhi _m$

) and the mean electrostatic Stokes number (

![]() $\overline {St_{el}}$

) are used to quantify the importance of particle–turbulence and particle–electrostatics couplings, respectively, while the viscous Stokes number (

$\overline {St_{el}}$

) are used to quantify the importance of particle–turbulence and particle–electrostatics couplings, respectively, while the viscous Stokes number (

![]() $St^+$

) is employed to assess the particle inertial effects. First, the particle-to-air mass loading ratio is defined as

$St^+$

) is employed to assess the particle inertial effects. First, the particle-to-air mass loading ratio is defined as

![]() $\varPhi _m = \rho _p / \rho _f \phi _V$

, where

$\varPhi _m = \rho _p / \rho _f \phi _V$

, where

![]() $\rho _p$

,

$\rho _p$

,

![]() $\rho _f$

, and

$\rho _f$

, and

![]() $\phi _V$

represent the particle mass density, air mass density, and particle volume fraction, respectively. It is well established that turbulence modulation by particles intensifies with increasing

$\phi _V$

represent the particle mass density, air mass density, and particle volume fraction, respectively. It is well established that turbulence modulation by particles intensifies with increasing

![]() $\varPhi _m$

, becoming prominent at

$\varPhi _m$

, becoming prominent at

![]() $\varPhi _m \sim O(0.1)$

(e.g. Kulick, Fessler & Eaton Reference Kulick, Fessler and Eaton1994; Yousefi et al. Reference Yousefi, Costa, Picano and Brandt2023). Second, the electrostatic Stokes number is defined as the ratio of the particle relaxation time scale,

$\varPhi _m \sim O(0.1)$

(e.g. Kulick, Fessler & Eaton Reference Kulick, Fessler and Eaton1994; Yousefi et al. Reference Yousefi, Costa, Picano and Brandt2023). Second, the electrostatic Stokes number is defined as the ratio of the particle relaxation time scale,

![]() $\tau _p = d_p^2 \rho _p / (18 \nu \rho _f)$

(Maxey Reference Maxey1987; Eaton & Fessler Reference Eaton and Fessler1994), to the characteristic time scale of electrostatic interactions,

$\tau _p = d_p^2 \rho _p / (18 \nu \rho _f)$

(Maxey Reference Maxey1987; Eaton & Fessler Reference Eaton and Fessler1994), to the characteristic time scale of electrostatic interactions,

![]() $\tau _{el} = (6\pi \varepsilon _0 m_p / (n q^2))^{1/2}$

(Boutsikakis et al. Reference Boutsikakis, Fede and Simonin2022), expressed as

$\tau _{el} = (6\pi \varepsilon _0 m_p / (n q^2))^{1/2}$

(Boutsikakis et al. Reference Boutsikakis, Fede and Simonin2022), expressed as

![]() $St_{el} = \tau _p / \tau _{el}$

. Here,

$St_{el} = \tau _p / \tau _{el}$

. Here,

![]() $d_p$

,

$d_p$

,

![]() $\nu$

,

$\nu$

,

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

,

$\varepsilon _0$

,

![]() $m_p$

,

$m_p$

,

![]() $n$

and

$n$

and

![]() $q$

denote the particle diameter, air kinematic viscosity, vacuum permittivity, particle mass, particle number density, and particle electric charge, respectively. The definition of

$q$

denote the particle diameter, air kinematic viscosity, vacuum permittivity, particle mass, particle number density, and particle electric charge, respectively. The definition of

![]() $\tau _{el}$

is derived through dimensional analysis, assuming that

$\tau _{el}$

is derived through dimensional analysis, assuming that

![]() $\tau _{el}$

is solely determined by

$\tau _{el}$

is solely determined by

![]() $\varepsilon _0$

,

$\varepsilon _0$

,

![]() $m_p$

,

$m_p$

,

![]() $n$

and

$n$

and

![]() $q$

. Thus, the electrostatic Stokes number quantifies the relative importance of particle inertia compared to electrostatic forces: inter-particle electrostatic forces are negligible when

$q$

. Thus, the electrostatic Stokes number quantifies the relative importance of particle inertia compared to electrostatic forces: inter-particle electrostatic forces are negligible when

![]() $St_{el}$

is very small, whereas these forces dominate particle dynamics when

$St_{el}$

is very small, whereas these forces dominate particle dynamics when

![]() $St_{el}$

is large. In this study, the average electrostatic effect among charged particles is characterised by the mean electrostatic Stokes number

$St_{el}$

is large. In this study, the average electrostatic effect among charged particles is characterised by the mean electrostatic Stokes number

![]() $\overline {St_{el}}$

, taking into account only the particle class with the mean diameter. Third, the effects of particle inertia are evaluated using the viscous Stokes number,

$\overline {St_{el}}$

, taking into account only the particle class with the mean diameter. Third, the effects of particle inertia are evaluated using the viscous Stokes number,

![]() $St^+ \equiv \tau _p / \tau _\nu$

, where

$St^+ \equiv \tau _p / \tau _\nu$

, where

![]() $\tau _\nu = \nu / u_\tau ^2$

represents the viscous time scale. Particles with a large

$\tau _\nu = \nu / u_\tau ^2$

represents the viscous time scale. Particles with a large

![]() $St^+$

are expected to exhibit quasi-ballistic behaviour, while those with a small

$St^+$

are expected to exhibit quasi-ballistic behaviour, while those with a small

![]() $St^+$

tend to closely follow the fluid flow.

$St^+$

tend to closely follow the fluid flow.

The estimation of the particle-to-air mass-loading ratio

![]() $\varPhi _m$

and electrostatic Stokes number

$\varPhi _m$

and electrostatic Stokes number

![]() $\overline {St_{el}}$

is based on synchronous measurements of wind velocity, PM10 dust concentration and particle size distribution at 0.9 m height. Herein, several particle properties are used: (a) particle mass density is assumed to be 2650 kg m

$\overline {St_{el}}$

is based on synchronous measurements of wind velocity, PM10 dust concentration and particle size distribution at 0.9 m height. Herein, several particle properties are used: (a) particle mass density is assumed to be 2650 kg m

![]() $^{-3}$

, (b) the density and kinematic viscosity of the air are taken as 1.20 kg m

$^{-3}$

, (b) the density and kinematic viscosity of the air are taken as 1.20 kg m

![]() $^{-3}$

and 1.57

$^{-3}$

and 1.57

![]() $\times$

10

$\times$

10

![]() $^{-5}$

m

$^{-5}$

m

![]() $^2$

s

$^2$

s

![]() $^{-1}$

, respectively, and (c) the charge-to-mass ratio of particles is considered to have a typical value of 60

$^{-1}$

, respectively, and (c) the charge-to-mass ratio of particles is considered to have a typical value of 60

![]() $\unicode {x03BC}$

C kg

$\unicode {x03BC}$

C kg

![]() $^{-1}$

measured in dust storms (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Schmidt and Dent1998; Zheng, Huang & Zhou Reference Zheng, Huang and Zhou2003), although it may vary slightly from storm to storm. Further details regarding the estimation of

$^{-1}$

measured in dust storms (Schmidt et al. Reference Schmidt, Schmidt and Dent1998; Zheng, Huang & Zhou Reference Zheng, Huang and Zhou2003), although it may vary slightly from storm to storm. Further details regarding the estimation of

![]() $\varPhi _m$

and

$\varPhi _m$

and

![]() $\overline {St_{el}}$

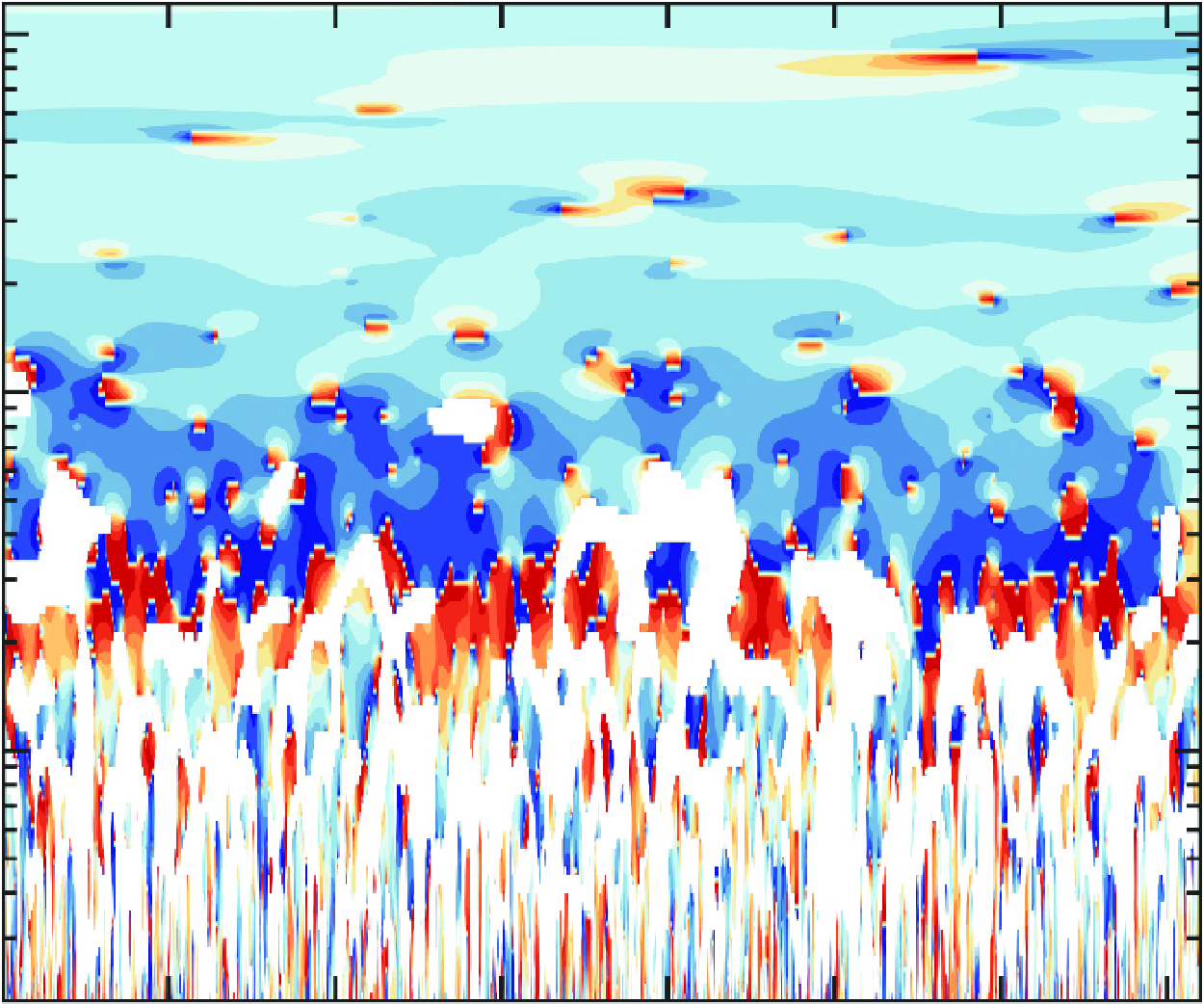

can be found in our previous study (Zhang & Zhou Reference Zhang and Zhou2023). Figure 1 displays an example of the complete time series of the multiple fields in dataset II. It is shown that the multiple fields, particularly PM10 dust concentration and electric field, exhibit significant local intermittent behaviour, posing new demands on data processing methods, which is discussed in

$\overline {St_{el}}$

can be found in our previous study (Zhang & Zhou Reference Zhang and Zhou2023). Figure 1 displays an example of the complete time series of the multiple fields in dataset II. It is shown that the multiple fields, particularly PM10 dust concentration and electric field, exhibit significant local intermittent behaviour, posing new demands on data processing methods, which is discussed in

![]() $\S$

3.

$\S$

3.

Figure 1. The complete data series of the dataset II. Panels (a–f) correspond to the streamwise (

![]() $U$

), spanwise (

$U$

), spanwise (

![]() $V$

) and wall-normal (

$V$

) and wall-normal (

![]() $W$

) components of the wind velocity, ambient temperature (

$W$

) components of the wind velocity, ambient temperature (

![]() $\varTheta$

), PM10 dust concentration (

$\varTheta$

), PM10 dust concentration (

![]() $C$

), as well as electric field (

$C$

), as well as electric field (

![]() $E$

), respectively.

$E$

), respectively.

3. Data analysis

3.1. Wavelet transform and wavelet PSD

Classical Fourier analysis represents data as a sum of trigonometric functions that extend to infinity, making it inefficient for dealing with local abrupt changes in multifield time series recorded in dust storms. In contrast, the use of a set of localised basis functions in wavelet transform allows us to unfold time series into the time and scale (or frequency) domain and, therefore, can uncover local intermittent events effectively (Daubechies Reference Daubechies1992; Farge Reference Farge1992; Torrence & Compo Reference Torrence and Compo1998; Zhou Reference Zhou2021). The continuous wavelet transform of a time series

![]() $\{x(t), \ t=0,\ldots ,N-1\}$

is defined as the convolution of

$\{x(t), \ t=0,\ldots ,N-1\}$

is defined as the convolution of

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

with a scaled and translated Morlet wavelet (Daubechies Reference Daubechies1992; Torrence & Compo Reference Torrence and Compo1998),

$\{x(t)\}$

with a scaled and translated Morlet wavelet (Daubechies Reference Daubechies1992; Torrence & Compo Reference Torrence and Compo1998),

\begin{align} W_{x}(t,\tau )=\sum _{t'=0}^{N-1}\sqrt {\frac {\delta _t}{\tau }}x(t')\overline {\psi _0}\left [ \frac {(t'-t)\delta _t}{\tau } \right ], \end{align}

\begin{align} W_{x}(t,\tau )=\sum _{t'=0}^{N-1}\sqrt {\frac {\delta _t}{\tau }}x(t')\overline {\psi _0}\left [ \frac {(t'-t)\delta _t}{\tau } \right ], \end{align}

where

![]() $t$

is the localised time index,

$t$

is the localised time index,

![]() $\tau$

is the wavelet scale that is inversely proportional to frequency

$\tau$

is the wavelet scale that is inversely proportional to frequency

![]() $f$

(i.e.

$f$

(i.e.

![]() $1/\tau =1.03f$

, see Torrence & Compo (Reference Torrence and Compo1998) for the details), Morlet wavelet is expressed as

$1/\tau =1.03f$

, see Torrence & Compo (Reference Torrence and Compo1998) for the details), Morlet wavelet is expressed as

![]() $\psi _0(\eta )=\pi ^{-1/4}e^{(i\omega _0\eta -\eta ^2/2)}$

with dimensionless frequency

$\psi _0(\eta )=\pi ^{-1/4}e^{(i\omega _0\eta -\eta ^2/2)}$

with dimensionless frequency

![]() $\omega _0=6$

satisfying the admissibility condition,

$\omega _0=6$

satisfying the admissibility condition,

![]() $\overline {()}$

denotes the complex conjugate, and

$\overline {()}$

denotes the complex conjugate, and

![]() $\delta _t$

is the sampling interval of the time series

$\delta _t$

is the sampling interval of the time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

. Here, the discrete scales

$\{x(t)\}$

. Here, the discrete scales

![]() $\{\tau (j)\}$

are selected as fractional powers of two:

$\{\tau (j)\}$

are selected as fractional powers of two:

where

![]() $\tau _0=2\delta _t$

is the smallest resolvable scale,

$\tau _0=2\delta _t$

is the smallest resolvable scale,

![]() $J$

determines the largest scale, and

$J$

determines the largest scale, and

![]() $\delta _j$

is the spacing between discrete scales.

$\delta _j$

is the spacing between discrete scales.

As the square of a wavelet coefficient gives a fluctuating energy at a given time index

![]() $t$

and scale

$t$

and scale

![]() $\tau$

, we thus define the local wavelet PSD of the time series

$\tau$

, we thus define the local wavelet PSD of the time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

as (Farge Reference Farge1992; Alexandrova et al. Reference Alexandrova, Carbone, Veltri and Sorriso-Valvo2008; Ruppert-Felsot, Farge & Petitjeans Reference Ruppert-Felsot, Farge and Petitjeans2009)

$\{x(t)\}$

as (Farge Reference Farge1992; Alexandrova et al. Reference Alexandrova, Carbone, Veltri and Sorriso-Valvo2008; Ruppert-Felsot, Farge & Petitjeans Reference Ruppert-Felsot, Farge and Petitjeans2009)

The global wavelet PSD is given by

\begin{align} \phi _{xx}(\tau ) = \langle \psi _{xx}(t,\tau ) \rangle _t=\frac {1}{N}\sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \psi _{xx}(t,\tau ), \end{align}

\begin{align} \phi _{xx}(\tau ) = \langle \psi _{xx}(t,\tau ) \rangle _t=\frac {1}{N}\sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \psi _{xx}(t,\tau ), \end{align}

where the time average

![]() $\langle \rangle _t$

is performed over the whole period. It is demonstrated that the global wavelet PSD corresponds to the smoothed Fourier PSD, providing an unbiased and consistent estimation of the true global PSD (Percival Reference Percival1995; Torrence & Compo Reference Torrence and Compo1998).

$\langle \rangle _t$

is performed over the whole period. It is demonstrated that the global wavelet PSD corresponds to the smoothed Fourier PSD, providing an unbiased and consistent estimation of the true global PSD (Percival Reference Percival1995; Torrence & Compo Reference Torrence and Compo1998).

3.2. Intermittency and coherent signature

Traditionally, the intermittency of a time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

at scale

$\{x(t)\}$

at scale

![]() $\tau$

can be characterised by the non-Gaussian probability density function (PDF) of the field increment

$\tau$

can be characterised by the non-Gaussian probability density function (PDF) of the field increment

![]() $\Delta x(t,\tau )=x(t+\tau )-x(t)$

between two time indexes

$\Delta x(t,\tau )=x(t+\tau )-x(t)$

between two time indexes

![]() $t$

and

$t$

and

![]() $t+\tau$

(Frisch Reference Frisch1995; Pope Reference Pope2000). Thanks to the fact that the real part of the wavelet coefficient

$t+\tau$

(Frisch Reference Frisch1995; Pope Reference Pope2000). Thanks to the fact that the real part of the wavelet coefficient

![]() $W_x(t,\tau )$

is proportional to the field increment

$W_x(t,\tau )$

is proportional to the field increment

![]() $\Delta x(t,\tau )$

(Bernardini et al. Reference Bernardini, Della Posta, Salvadore and Martelli2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Tan and Zheng2023), such deviations from the Gaussian PDF can be more conveniently measured by the wavelet flatness factor (Meneveau Reference Meneveau1991; Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Alexandrova et al. Reference Alexandrova, Carbone, Veltri and Sorriso-Valvo2008):

$\Delta x(t,\tau )$

(Bernardini et al. Reference Bernardini, Della Posta, Salvadore and Martelli2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Tan and Zheng2023), such deviations from the Gaussian PDF can be more conveniently measured by the wavelet flatness factor (Meneveau Reference Meneveau1991; Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Alexandrova et al. Reference Alexandrova, Carbone, Veltri and Sorriso-Valvo2008):

\begin{align} F_{x}(\tau )=\frac {\left \langle \left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^4 \right \rangle _t}{\left \langle \left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^2 \right \rangle ^2_t}, \end{align}

\begin{align} F_{x}(\tau )=\frac {\left \langle \left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^4 \right \rangle _t}{\left \langle \left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^2 \right \rangle ^2_t}, \end{align}

which quantifies the level of intermittency at scale

![]() $\tau$

. Notably, a Gaussian PDF corresponds to a wavelet flatness factor with a value of 3.

$\tau$

. Notably, a Gaussian PDF corresponds to a wavelet flatness factor with a value of 3.

In contrast to wavelet flatness factor, the so-called local intermittency measure (LIM) (Farge Reference Farge1992; Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997),

\begin{align} I_{x}(t,\tau )=\frac {\left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^2}{\left \langle \left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^2 \right \rangle _t }, \end{align}

\begin{align} I_{x}(t,\tau )=\frac {\left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^2}{\left \langle \left | W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right | ^2 \right \rangle _t }, \end{align}

is defined by the ratio of local energy at the time index

![]() $t$

and the scale

$t$

and the scale

![]() $\tau$

to the time-averaged energy at the same scale and is generally used to quantify the level of local intermittency.

$\tau$

to the time-averaged energy at the same scale and is generally used to quantify the level of local intermittency.

Based on LIM, it is convenient to extract time signatures of coherent structures from single-point measurements (Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Guj & Camussi Reference Guj and Camussi1999; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Grilliat, Caputi-Gennaro and Jacob2010). The basic idea is that intermittency is closely related to the strong field gradients (or field singularity) resulting from the passage of coherent structures. More specifically, the localised energetic coherent structures can be well projected onto a wavelet basis and thus are represented by sparse wavelet coefficients of large modules at a given time and scale (Salem et al. Reference Salem, Mangeney, Bale and Veltri2009; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Grilliat, Caputi-Gennaro and Jacob2010). In contrast, the random weak incoherent components have wavelet coefficients extensively spread in the time and scale domain with a considerably smaller module compared to the coherent coefficients. Consequently, a large LIM could be considered as a result of coherent structures passing through the measurement points according to (3.7) (Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Guj & Camussi Reference Guj and Camussi1999; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Robert and Jacob2008; Salem et al. Reference Salem, Mangeney, Bale and Veltri2009).

To clarify the relationships among the coherent structures of multiple fields in dust storms, a wavelet conditional average method is used to identify the phase-averaged coherent signatures of the wind velocity, PM10 dust concentration and electric field (Camussi & Guj Reference Camussi and Guj1997; Guj & Camussi Reference Guj and Camussi1999; Camussi Reference Camussi2002; Camussi & Di Felice Reference Camussi and Di Felice2006; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Robert and Jacob2008; Salem et al. Reference Salem, Mangeney, Bale and Veltri2009; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Grilliat, Caputi-Gennaro and Jacob2010; Crawley et al. Reference Crawley, Gefen, Kuo, Samimy and Camussi2018). The coherent signatures of a time series are defined as the portions of the original time series (i.e. time series segments of appropriate width) that are centred around the energetic coherent structures. It is reasonably expected that LIM at scale

![]() $\tau _s$

larger than a threshold

$\tau _s$

larger than a threshold

![]() $T_h$

are expected to correspond to the energetic coherent structures. Therefore, a set of time indices

$T_h$

are expected to correspond to the energetic coherent structures. Therefore, a set of time indices

![]() $\{t_0(i), \ i=0,\ldots ,N_e-1\}$

at which the coherent signatures are centred can be determined by

$\{t_0(i), \ i=0,\ldots ,N_e-1\}$

at which the coherent signatures are centred can be determined by

where

![]() $N_e$

is the number of the coherent signatures and

$N_e$

is the number of the coherent signatures and

![]() $\tau _s$

is set to be

$\tau _s$

is set to be

![]() $\tau _0$

in order to obtain a better time resolution and statistical convergence of the conditional average (Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Grilliat, Caputi-Gennaro and Jacob2010). In addition, the threshold LIM must be high enough, but not too high, so that only the most energetic coherent structures are detected and statistical convergence is achieved. A detailed discussion of the selection of threshold LIM

$\tau _0$

in order to obtain a better time resolution and statistical convergence of the conditional average (Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Grilliat, Caputi-Gennaro and Jacob2010). In addition, the threshold LIM must be high enough, but not too high, so that only the most energetic coherent structures are detected and statistical convergence is achieved. A detailed discussion of the selection of threshold LIM

![]() $T_h$

in the present study is provided in Appendix A. Apparently, a single coherent signature could be either positive or negative, but only positive LIM peaks are selected for identifying energetic signatures in the wavelet conditional average (Crawley et al. Reference Crawley, Gefen, Kuo, Samimy and Camussi2018).

$T_h$

in the present study is provided in Appendix A. Apparently, a single coherent signature could be either positive or negative, but only positive LIM peaks are selected for identifying energetic signatures in the wavelet conditional average (Crawley et al. Reference Crawley, Gefen, Kuo, Samimy and Camussi2018).

Once the threshold LIM is selected, the

![]() $i$

th extracted coherent signature

$i$

th extracted coherent signature

![]() $\{\widetilde {x}_i(j), j=0,\ldots ,\varXi \}$

can be explicitly expressed as

$\{\widetilde {x}_i(j), j=0,\ldots ,\varXi \}$

can be explicitly expressed as

where

![]() $\varXi +1$

is the width of each extracted coherent signature.

$\varXi +1$

is the width of each extracted coherent signature.

The resulting phase-averaged coherent signature of time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

is accordingly written as

$\{x(t)\}$

is accordingly written as

\begin{align} \langle \widetilde {x} \rangle = \langle \widetilde {x}_i(j) \rangle _{N_e} = \frac {1}{N_e}\sum _{i=0}^{N_e-1}\widetilde {x}_i(j), \end{align}

\begin{align} \langle \widetilde {x} \rangle = \langle \widetilde {x}_i(j) \rangle _{N_e} = \frac {1}{N_e}\sum _{i=0}^{N_e-1}\widetilde {x}_i(j), \end{align}

where

![]() $j=0,\ldots ,\varXi$

and the ensemble average

$j=0,\ldots ,\varXi$

and the ensemble average

![]() $\langle \rangle _{N_e}$

is taken over all extracted coherent signatures centred at

$\langle \rangle _{N_e}$

is taken over all extracted coherent signatures centred at

![]() $\{t_0(i)\}$

. It is clear that the averaged coherent signature

$\{t_0(i)\}$

. It is clear that the averaged coherent signature

![]() $\langle \widetilde {x} \rangle$

represents the pattern of the most energetic coherent structures hidden in the original time series.

$\langle \widetilde {x} \rangle$

represents the pattern of the most energetic coherent structures hidden in the original time series.

3.3. Wavelet coherence and linear coupling

To quantitatively assess the correlation between two time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

and

$\{x(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

, the cross wavelet transform

$\{y(t)\}$

, the cross wavelet transform

![]() $W_{xy}$

can be introduced as (Hudgins, Friehe & Mayer Reference Hudgins, Friehe and Mayer1993)

$W_{xy}$

can be introduced as (Hudgins, Friehe & Mayer Reference Hudgins, Friehe and Mayer1993)

In analogy with the Pearson correlation coefficient, the wavelet coherence between two time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

and

$\{x(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

is given by (Grinsted, Moore & Jevrejeva Reference Grinsted, Moore and Jevrejeva2004; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Robert and Jacob2008)

$\{y(t)\}$

is given by (Grinsted, Moore & Jevrejeva Reference Grinsted, Moore and Jevrejeva2004; Camussi et al. Reference Camussi, Robert and Jacob2008)

\begin{align} \gamma _{xy}^{2}(t,\tau )=\frac {\left |\mathcal {S}\left ( W_{xy}(t,\tau )\right )\right |^{2}}{\mathcal {S}\left (\left |W_{x}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}\right ) \mathcal {S}\left (|W_{y}(t,\tau )|^{2}\right )}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \gamma _{xy}^{2}(t,\tau )=\frac {\left |\mathcal {S}\left ( W_{xy}(t,\tau )\right )\right |^{2}}{\mathcal {S}\left (\left |W_{x}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}\right ) \mathcal {S}\left (|W_{y}(t,\tau )|^{2}\right )}, \end{align}

where

![]() $\mathcal {S}$

is a smoothing operator in time and scale domain and can be used to build a balance between desired time and scale resolution and statistical significance (Grinsted et al. Reference Grinsted, Moore and Jevrejeva2004). In this study, the smoothing operator is given by

$\mathcal {S}$

is a smoothing operator in time and scale domain and can be used to build a balance between desired time and scale resolution and statistical significance (Grinsted et al. Reference Grinsted, Moore and Jevrejeva2004). In this study, the smoothing operator is given by

![]() $\mathcal {S}(W)=\mathcal {S}_{{scale }}(\mathcal {S}_{{time }}(W(t, \tau )))$

, where

$\mathcal {S}(W)=\mathcal {S}_{{scale }}(\mathcal {S}_{{time }}(W(t, \tau )))$

, where

![]() $\mathcal {S}_{{scale }}$

and

$\mathcal {S}_{{scale }}$

and

![]() $\mathcal {S}_{{time }}$

denote smoothing along the wavelet scale and time axis, respectively. Following Grinsted et al. (Reference Grinsted, Moore and Jevrejeva2004) and Camussi et al. (Reference Camussi, Robert and Jacob2008), we define the time-axis smoothing as

$\mathcal {S}_{{time }}$

denote smoothing along the wavelet scale and time axis, respectively. Following Grinsted et al. (Reference Grinsted, Moore and Jevrejeva2004) and Camussi et al. (Reference Camussi, Robert and Jacob2008), we define the time-axis smoothing as

![]() $\mathcal {S}_{{time }}(W(t, \tau ))=W(t, \tau ) * c_1 \exp (-t^2/(2 \tau ^2))$

at a fixed

$\mathcal {S}_{{time }}(W(t, \tau ))=W(t, \tau ) * c_1 \exp (-t^2/(2 \tau ^2))$

at a fixed

![]() $\tau$

, and the scale-axis smoothing as

$\tau$

, and the scale-axis smoothing as

![]() $\mathcal {S}_{{scale }}(W(t, \tau ))=W(t, \tau ) * c_2 \Pi (0.6 \tau )$

at a fixed

$\mathcal {S}_{{scale }}(W(t, \tau ))=W(t, \tau ) * c_2 \Pi (0.6 \tau )$

at a fixed

![]() $t$

. Here, the symbol

$t$

. Here, the symbol

![]() $*$

denotes the convolution product,

$*$

denotes the convolution product,

![]() $c_1$

and

$c_1$

and

![]() $c_2$

are normalisation constants, and

$c_2$

are normalisation constants, and

![]() $\Pi$

is the rectangle function. The scale smoothing is implemented using a boxcar filter with a width of 0.6. It is obvious that wavelet coherence

$\Pi$

is the rectangle function. The scale smoothing is implemented using a boxcar filter with a width of 0.6. It is obvious that wavelet coherence

![]() $\gamma _{xy}^{2}(t,\tau )$

ranges from 0 to 1 and can be considered as a localised correlation coefficient in time and scale domain. In a system consisting solely of two interacting time series, wavelet coherence also represents a measure of the localised linear coupling between two time series (Ritz & Powers Reference Ritz and Powers1986; Narayanan & Hussain Reference Narayanan and Hussain1996; Bendat & Piersol Reference Bendat and Piersol2011). When

$\gamma _{xy}^{2}(t,\tau )$

ranges from 0 to 1 and can be considered as a localised correlation coefficient in time and scale domain. In a system consisting solely of two interacting time series, wavelet coherence also represents a measure of the localised linear coupling between two time series (Ritz & Powers Reference Ritz and Powers1986; Narayanan & Hussain Reference Narayanan and Hussain1996; Bendat & Piersol Reference Bendat and Piersol2011). When

![]() $\gamma _{xy}^2(t,\tau )=1$

,

$\gamma _{xy}^2(t,\tau )=1$

,

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

and

$\{x(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

are perfectly linearly coupled at time index

$\{y(t)\}$

are perfectly linearly coupled at time index

![]() $t$

and scale

$t$

and scale

![]() $\tau$

.

$\tau$

.

It is straightforward to extend the concept of wavelet coherence to the case of multiple interacting time series, for example,

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

,

$\{y(t)\}$

,

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

and

$\{x_1(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{x_2(t)\}$

. In many situations,

$\{x_2(t)\}$

. In many situations,

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

(e.g. PM10 dust concentration) is coupled to both

$\{y(t)\}$

(e.g. PM10 dust concentration) is coupled to both

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

and

$\{x_1(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{x_2(t)\}$

(e.g. wind velocity and electric field). To uncover the ‘pure’ linear coupling between

$\{x_2(t)\}$

(e.g. wind velocity and electric field). To uncover the ‘pure’ linear coupling between

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

and

$\{y(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

, one can define the partial wavelet coherence analogous to partial correlation as (Mihanović, Orlić & Pasarić Reference Mihanović, Orlić and Pasarić2009; Xiang & Qu Reference Xiang and Qu2018)

$\{x_1(t)\}$

, one can define the partial wavelet coherence analogous to partial correlation as (Mihanović, Orlić & Pasarić Reference Mihanović, Orlić and Pasarić2009; Xiang & Qu Reference Xiang and Qu2018)

\begin{align} \gamma _{yx_1(x_2)}^2(t,\tau )=\frac {\left |\gamma _{yx_1}(t,\tau )-\gamma _{yx_2}(t,\tau )\overline {\gamma _{x_1x_2}}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}}{ \left ( 1-\gamma _{yx_2}^2(t,\tau ) \right ) \left( 1-\vphantom{\gamma _{yx_2}^2}\gamma _{x_1x_2}^2(t,\tau ) \right ) }, \end{align}

\begin{align} \gamma _{yx_1(x_2)}^2(t,\tau )=\frac {\left |\gamma _{yx_1}(t,\tau )-\gamma _{yx_2}(t,\tau )\overline {\gamma _{x_1x_2}}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}}{ \left ( 1-\gamma _{yx_2}^2(t,\tau ) \right ) \left( 1-\vphantom{\gamma _{yx_2}^2}\gamma _{x_1x_2}^2(t,\tau ) \right ) }, \end{align}

where

![]() $\gamma _{yx_1}$

(similarly for

$\gamma _{yx_1}$

(similarly for

![]() $\gamma _{yx_2}$

and

$\gamma _{yx_2}$

and

![]() $\gamma_{x_1x_2}$

) is given by

$\gamma_{x_1x_2}$

) is given by

\begin{align} \gamma _{yx_1}(t,\tau )=\frac { \mathcal {S}\left ( W_{yx_1}(t,\tau )\right )}{\mathcal {S}\left (\left |W_{y}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}\right )^{1/2} \mathcal {S}\left (\left |W_{x_1}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}\right )^{1/2}}. \end{align}

\begin{align} \gamma _{yx_1}(t,\tau )=\frac { \mathcal {S}\left ( W_{yx_1}(t,\tau )\right )}{\mathcal {S}\left (\left |W_{y}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}\right )^{1/2} \mathcal {S}\left (\left |W_{x_1}(t,\tau )\right |^{2}\right )^{1/2}}. \end{align}

Accordingly, partial wavelet coherence

![]() $\gamma _{yx_1(x_2)}^2$

measures the localised linear coupling between

$\gamma _{yx_1(x_2)}^2$

measures the localised linear coupling between

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

and

$\{y(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

after excluding the influence of

$\{x_1(t)\}$

after excluding the influence of

![]() $\{x_2(t)\}$

. Moreover, the multiple wavelet coherence defined by (Mihanović, Orlić & Pasarić Reference Mihanović, Orlić and Pasarić2009),

$\{x_2(t)\}$

. Moreover, the multiple wavelet coherence defined by (Mihanović, Orlić & Pasarić Reference Mihanović, Orlić and Pasarić2009),

\begin{align} \gamma _{yx_1x_2}^2(t,\tau )=\frac {\gamma _{yx_1}^2(t,\tau )+\gamma _{yx_2}^2(t,\tau )-2\text {Re}\left (\gamma _{yx_1}(t,\tau )\overline {\gamma _{yx_2}}(t,\tau )\overline {\gamma _{x_1x_2}}(t,\tau )\right )}{1-\gamma _{x_1x_2}^2(t,\tau )}, \end{align}

\begin{align} \gamma _{yx_1x_2}^2(t,\tau )=\frac {\gamma _{yx_1}^2(t,\tau )+\gamma _{yx_2}^2(t,\tau )-2\text {Re}\left (\gamma _{yx_1}(t,\tau )\overline {\gamma _{yx_2}}(t,\tau )\overline {\gamma _{x_1x_2}}(t,\tau )\right )}{1-\gamma _{x_1x_2}^2(t,\tau )}, \end{align}

can be used to account for the proportion of wavelet power of

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

at a time index

$\{y(t)\}$

at a time index

![]() $t$

and scale

$t$

and scale

![]() $\tau$

explained by the linear relationship with

$\tau$

explained by the linear relationship with

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

and

$\{x_1(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{x_2(t)\}$

. In (3.15),

$\{x_2(t)\}$

. In (3.15),

![]() $\operatorname {Re}()$

denotes the real part of a complex number.

$\operatorname {Re}()$

denotes the real part of a complex number.

Overall, as opposed to Fourier coherence, wavelet coherence and partial wavelet coherence provides a powerful tool to examine the localised linear coupling between two or three fields.

3.4. Wavelet bicoherence and quadratic nonlinear coupling

Aside from linear coupling, higher-order nonlinear couplings are undoubtedly broadband and significant in turbulent flows. In particular, frequency (or equivalently scale) components can interact with one another, generating new components at their sum (or difference) frequencies, known as combination components. In other words, the phases of the combination components are coupled to the primary interacting frequency pairs. This phenomenon goes by several different names including three-wave coupling, nonlinear triadic interactions and quadratic nonlinear (or phase) coupling but in each case the same basic mechanisms are involved.

Owing to the intermittent nature of turbulent fields, these phase couplings are not entirely filling in the time and frequency/scale space. In contrast to the Fourier bicoherence, which serves as a global phase coupling measure, the wavelet bicoherence can be used to detect the short-lived intermittent quadratic nonlinear coupling (Van Milligen, Hidalgo & Sanchez Reference Van Milligen, Hidalgo and Sanchez1995; Lancaster et al. Reference Lancaster, Iatsenko, Pidde, Ticcinelli and Stefanovska2018). The wavelet auto-bicoherence of time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

over the period

$\{x(t)\}$

over the period

![]() $t \in [0, \ N-1 ]$

is defined by (Van Milligen et al. Reference Van Milligen, Hidalgo and Sanchez1995; Schulte Reference Schulte2016)

$t \in [0, \ N-1 ]$

is defined by (Van Milligen et al. Reference Van Milligen, Hidalgo and Sanchez1995; Schulte Reference Schulte2016)

\begin{align} b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=\frac {\left | \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2)\overline {W_{x}}(t,\tau )\right |^2 }{\left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right |^2\right ) \left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2) \right |^2\right )}, \end{align}

\begin{align} b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=\frac {\left | \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2)\overline {W_{x}}(t,\tau )\right |^2 }{\left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x}(t,\tau ) \right |^2\right ) \left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2) \right |^2\right )}, \end{align}

where the frequency sum rule,

is satisfied. The auto-bicoherence

![]() $b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)$

determines the degree of quadratic nonlinear coupling among scales

$b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)$

determines the degree of quadratic nonlinear coupling among scales

![]() $\tau _1$

,

$\tau _1$

,

![]() $\tau _2$

and

$\tau _2$

and

![]() $\tau$

of time series

$\tau$

of time series

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

over the period

$\{x(t)\}$

over the period

![]() $t\in [0, N-1 ]$

. By definition, wavelet auto-bicoherence is bounded between 0 and 1, with

$t\in [0, N-1 ]$

. By definition, wavelet auto-bicoherence is bounded between 0 and 1, with

![]() $b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=0$

for independent random phase relationships, and

$b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=0$

for independent random phase relationships, and

![]() $b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=1$

for a maximum amount of coupling.

$b^2_{xxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=1$

for a maximum amount of coupling.

In turbulent flows, quadratic nonlinear couplings represent the nonlinear energy transfer among turbulent motions at scales

![]() $\tau _1$

,

$\tau _1$

,

![]() $\tau _2$

and

$\tau _2$

and

![]() $\tau$

, as well as the breakup of vortices (e.g.

$\tau$

, as well as the breakup of vortices (e.g.

![]() $\tau \rightarrow (\tau _1, \tau _2)$

) and the formation of new vortices (e.g.

$\tau \rightarrow (\tau _1, \tau _2)$

) and the formation of new vortices (e.g.

![]() $(\tau _1, \tau _2) \rightarrow \tau$

) (Kim & Williams Reference Kim and Williams2006). These processes ultimately lead to the redistribution of energy across different scales. Consequently, strong quadratic nonlinear couplings are indicative of notable spectral energy redistribution (Elgar & Guza Reference Elgar and Guza1985; Kim & Williams Reference Kim and Williams2006; Bountin et al. Reference Bountin, Shiplyuk and Maslov2008; Unnikrishnan & Gaitonde Reference Unnikrishnan and Gaitonde2020), by means of both nonlinear energy transfer and the generation and disintegration of turbulent structures.

$(\tau _1, \tau _2) \rightarrow \tau$

) (Kim & Williams Reference Kim and Williams2006). These processes ultimately lead to the redistribution of energy across different scales. Consequently, strong quadratic nonlinear couplings are indicative of notable spectral energy redistribution (Elgar & Guza Reference Elgar and Guza1985; Kim & Williams Reference Kim and Williams2006; Bountin et al. Reference Bountin, Shiplyuk and Maslov2008; Unnikrishnan & Gaitonde Reference Unnikrishnan and Gaitonde2020), by means of both nonlinear energy transfer and the generation and disintegration of turbulent structures.

Similarly, the wavelet cross-bicoherence over the period

![]() $t\in [0, N-1 ]$

can be defined as (Van Milligen et al. Reference Van Milligen, Sanchez, Estrada, Hidalgo, Brañas, Carreras and García1995; Lancaster et al. Reference Lancaster, Iatsenko, Pidde, Ticcinelli and Stefanovska2018)

$t\in [0, N-1 ]$

can be defined as (Van Milligen et al. Reference Van Milligen, Sanchez, Estrada, Hidalgo, Brañas, Carreras and García1995; Lancaster et al. Reference Lancaster, Iatsenko, Pidde, Ticcinelli and Stefanovska2018)

\begin{align} b^2_{yxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=\frac {\left | \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2)\overline {W_{y}}(t,\tau )\right |^2 }{\left (\sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2) \right |^2 \right ) \left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left | W_{y}(t,\tau ) \right |^2\right ) }, \end{align}

\begin{align} b^2_{yxx}(\tau _1,\tau _2)=\frac {\left | \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2)\overline {W_{y}}(t,\tau )\right |^2 }{\left (\sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x}(t,\tau _1)W_{x}(t,\tau _2) \right |^2 \right ) \left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left | W_{y}(t,\tau ) \right |^2\right ) }, \end{align}

which measures the degree of quadratic nonlinear coupling in the period

![]() $ [0, N-1 ]$

among scales

$ [0, N-1 ]$

among scales

![]() $\tau _1$

and

$\tau _1$

and

![]() $\tau _2$

of

$\tau _2$

of

![]() $\{x(t)\}$

and scale

$\{x(t)\}$

and scale

![]() $\tau$

of

$\tau$

of

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

.

$\{y(t)\}$

.

The wavelet cross-bicoherence can be also extended to the case of three coupled time series

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

,

$\{x_1(t)\}$

,

![]() $\{x_2(t)\}$

and

$\{x_2(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

(e.g. Corke, Shakib & Nagib Reference Corke, Shakib and Nagib1991; Corke et al. Reference Corke, Arndt, Matlis and Semper2018; Arndt et al. Reference Arndt, Corke, Matlis and Semper2020; Middlebrooks et al. Reference Middlebrooks, Corke, Matlis and Semper2024):

$\{y(t)\}$

(e.g. Corke, Shakib & Nagib Reference Corke, Shakib and Nagib1991; Corke et al. Reference Corke, Arndt, Matlis and Semper2018; Arndt et al. Reference Arndt, Corke, Matlis and Semper2020; Middlebrooks et al. Reference Middlebrooks, Corke, Matlis and Semper2024):

\begin{align} b^2_{yx_1x_2}(\tau _1,\tau _2)= \frac {\left | \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} W_{x_1}(t,\tau _1)W_{x_2}(t,\tau _2)\overline {W_{y}}(t,\tau )\right |^2 }{\left (\sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x_1}(t,\tau _1)W_{x_2}(t,\tau _2) \right |^2 \right ) \left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left | W_{y}(t,\tau ) \right |^2\right ) }, \end{align}

\begin{align} b^2_{yx_1x_2}(\tau _1,\tau _2)= \frac {\left | \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} W_{x_1}(t,\tau _1)W_{x_2}(t,\tau _2)\overline {W_{y}}(t,\tau )\right |^2 }{\left (\sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left |W_{x_1}(t,\tau _1)W_{x_2}(t,\tau _2) \right |^2 \right ) \left ( \sum _{t=0}^{N-1} \left | W_{y}(t,\tau ) \right |^2\right ) }, \end{align}

which is a measure the degree of quadratic nonlinear coupling in the period

![]() $ [0, N-1 ]$

among scale

$ [0, N-1 ]$

among scale

![]() $\tau _1$

of

$\tau _1$

of

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

, scale

$\{x_1(t)\}$

, scale

![]() $\tau _2$

of

$\tau _2$

of

![]() $\{x_2(t)\}$

and scale

$\{x_2(t)\}$

and scale

![]() $\tau$

of

$\tau$

of

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

. Although the concept of partial wavelet coherence

$\{y(t)\}$

. Although the concept of partial wavelet coherence

![]() $\gamma _{yx_1(x_2)}^2$

mentioned above can be used to extract the ‘pure’ linear coupling between

$\gamma _{yx_1(x_2)}^2$

mentioned above can be used to extract the ‘pure’ linear coupling between

![]() $\{y(t)\}$

and

$\{y(t)\}$

and

![]() $\{x_1(t)\}$

(or

$\{x_1(t)\}$

(or

![]() $\{x_2(t)\}$

), we have no similar theory of partial wavelet bicoherence to isolate the ‘pure’ quadratic nonlinear coupling so far (McComas & Briscoe Reference McComas and Briscoe1980; Van Milligen et al. Reference Van Milligen, Hidalgo and Sanchez1995).

$\{x_2(t)\}$

), we have no similar theory of partial wavelet bicoherence to isolate the ‘pure’ quadratic nonlinear coupling so far (McComas & Briscoe Reference McComas and Briscoe1980; Van Milligen et al. Reference Van Milligen, Hidalgo and Sanchez1995).

Furthermore, the wavelet summed bicoherence is defined as (Van Milligen et al. Reference Van Milligen, Hidalgo and Sanchez1995)

where the sum is taken over all

![]() $\tau _1$

and

$\tau _1$

and

![]() $\tau _2$

such that (3.17) is satisfied and

$\tau _2$

such that (3.17) is satisfied and

![]() $\xi (\tau )$

is the number of summands in the summation. By essentially aggregating or averaging the quadratic nonlinear couplings over multiple frequency pairs

$\xi (\tau )$

is the number of summands in the summation. By essentially aggregating or averaging the quadratic nonlinear couplings over multiple frequency pairs

![]() $\tau _1$

and

$\tau _1$

and

![]() $\tau _2$

, the summed bicoherence

$\tau _2$

, the summed bicoherence

![]() $B^2(\tau )$

provides insight into the overall strength or prevalence of the quadratic nonlinear couplings across the entire spectrum. Clearly, a higher summed bicoherence value suggests a stronger quadratic nonlinear coupling between frequency components at specific frequency combinations.

$B^2(\tau )$

provides insight into the overall strength or prevalence of the quadratic nonlinear couplings across the entire spectrum. Clearly, a higher summed bicoherence value suggests a stronger quadratic nonlinear coupling between frequency components at specific frequency combinations.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. Strong two-way particle–turbulence and particle–electrostatics couplings

We begin by determining the presence of strong two-way particle–turbulence and particle–electrostatics couplings in the eight dust storm datasets. Since particles are influenced by turbulence and the electric field is generated by moving charged particles, our objective is to explore whether dust particles introduce a significant feedback effect on turbulence and whether the electric field substantially affects particle transport.

First, these significant two-way couplings can be indirectly inferred from the large dimensionless parameters,

![]() $\varPhi _m$

and

$\varPhi _m$

and

![]() $\overline {St_{el}}$

. At a height of 0.9 m, both

$\overline {St_{el}}$

. At a height of 0.9 m, both

![]() $\varPhi _m$

and

$\varPhi _m$

and

![]() $\overline {St_{el}}$

are estimated to reach approximately

$\overline {St_{el}}$

are estimated to reach approximately

![]() $O(0.1)$

(see table 1), indicating strong two-way couplings between particle–turbulence and particle–electrostatics, as suggested by the previously established criteria (Elghobashi Reference Elghobashi1994; Boutsikakis et al. Reference Boutsikakis, Fede and Simonin2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Cui and Zheng2023).

$O(0.1)$

(see table 1), indicating strong two-way couplings between particle–turbulence and particle–electrostatics, as suggested by the previously established criteria (Elghobashi Reference Elghobashi1994; Boutsikakis et al. Reference Boutsikakis, Fede and Simonin2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Cui and Zheng2023).

Additionally, direct evidence is provided by examining how dust particles regulate turbulence statistics and how electrostatic effects influence PM10 dust concentration and vertical turbulent flux within a narrow range of friction velocity. Wall-normal profiles of the inner-scaled mean streamwise wind velocity and Reynolds shear stress are presented in figure 2. For comparison, the Reynolds stress documented by Hutchins et al. (Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012) at the Surface Layer Turbulence and Environmental Science Test facility is also plotted in figure 2(b). Using the boundary layer thickness

![]() $\delta =166\pm 38$

m at the QLOA site (see Wang & Zheng Reference Wang and Zheng2016) and calculating the kinematic viscosity

$\delta =166\pm 38$

m at the QLOA site (see Wang & Zheng Reference Wang and Zheng2016) and calculating the kinematic viscosity

![]() $\nu$

based on Sutherland’s law (Sutherland Reference Sutherland1893), we find that the friction Reynolds number

$\nu$

based on Sutherland’s law (Sutherland Reference Sutherland1893), we find that the friction Reynolds number

![]() $Re_\tau \equiv u_\tau \delta /\nu$

varies from

$Re_\tau \equiv u_\tau \delta /\nu$

varies from

![]() $3.44\times 10^6$

to

$3.44\times 10^6$

to

![]() $6.72\times 10^6$

for the eight dust storm datasets, which is consistent with the values reported by Hutchins et al. (Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012). The strong consistency between the results of Hutchins et al. (Reference Hutchins, Chauhan, Marusic, Monty and Klewicki2012) and the clean-air dataset indicates the high quality of the datasets used herein. It is evident that the mean streamwise velocity and Reynolds stress for both clean-air and dust storm datasets fairly follow a logarithmic law. However, compared to the clean-air dataset, the dust storm datasets exhibit lower inner-scaled mean streamwise wind velocity and relatively higher inner-scaled Reynolds stress (especially for

$6.72\times 10^6$