The Yellow River is a unit. It cannot be divided into a few sections, repairing only a few parts of it. It is not like a railway or a highway. . . . If the north side of the river is well repaired but the south side is in turmoil then we have gained no real benefit. If military action keeps swaying back and forth then the dykes cannot be held long enough by either side for repair. This problem must be discussed.Footnote 1

Introduction

On March 15, 1947, China's Nationalist government, with significant aid from the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), finally succeeded in closing a major breach in the southern dike of the Yellow River, thus returning the river to the northern course it had followed between 1855 and 1938. For people from the broad swaths of Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu provinces that had been inundated when the river shifted south after the Nationalists deliberately breached the dike in June 1938 in a desperate attempt to use flooding to slow the advance of the Imperial Japanese Army, the closure provided welcome relief from nine years of constant flooding (Dagongbao, January 12, 1947). For Hebei and Shandong residents living along the pre-1938 course of the river, however, and for the more than 400,000 people who had moved into the dry riverbed to farm after the course change, the return of the river was a tremendous burden. “The coming of the river is not considered a blessing,” noted UNRRA representative Irving Barnett after visiting eastern Shandong a few months after the closure of the breach. The enormous amount of dike-repair work necessary to prepare for the returning waters exhausted the entire area, and evacuees from the old riverbed were bitter about the homes and land lost to the river (Barnett c. Reference Barnett1947: 2–4). The fact that China's Nationalist Party (Guomindang, Kuomintang, GMD, or KMT) government controlled most of the flooded areas of Henan and Anhui during the war with Japan, while the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) established a significant presence behind Japanese lines in rural areas along the river's pre-1938 course through Shandong, meant that the question of when and how to close the breach and return the river to its northern course became entangled in the Chinese Civil War (1946–49) once relations between the rival parties broke down after the Japanese defeat.

Both the Yellow River and the Chinese Civil War have received considerable scholarly attention in recent years, but how the two intertwined during the war years has not been examined in much detail (Dodgen Reference Dodgen2001; Lai Reference Lai2011; Lew Reference Lew2009; Minguo Huanghe Shi xiezuo zu [MHS] 2009; Pepper Reference Pepper1999; Pietz Reference Pietz2015; Westad Reference Westad2003).Footnote 2 Similarly, the events leading up to Nationalist leadership's decision to breach the Yellow River dike for strategic purposes in the early stages of World War II, and the multifaceted impact the ensuing years of flooding had on Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu, have been well investigated (Edgerton-Tarpley Reference Edgerton-Tarpley2014, Reference Edgerton-Tarpley2016; Lary Reference Lary2001, Reference Lary, Selden and Alvin2004; Mei Reference Mei2009; Mitter Reference Mitter2013a; Muscolino Reference Muscolino2011, Reference Muscolino2015; Qu Reference Qu2003), but how the disappearance of the river in 1938 and its sudden return in 1947 influenced areas along its northern course has been largely overlooked.Footnote 3 After briefly introducing key hydrological characteristics of the Yellow River and contextualizing the 1938 breach, this article employs archival documents, media reports from the 1940s, and county-level narratives published in China after 1949 to examine the following points: (1) how the breach-closure project became embroiled in the Chinese Civil War; (2) the impact the river's return had on communities along its northern course; and (3) ways in which both the Nationalists and the Communists imagined the Yellow River and made strategic and rhetorical use of it to discredit the rival party and foster their own legitimacy. I find that the campaign to return the Yellow River to its northern course after Japan's defeat was complicated not only by China's descent into civil war but also by tension between local and national interests within the Communist Party, and that UNRRA's attempts to mediate between the Communists and the Nationalists at times put the organization at odds with both parties. Moreover, in 1946 and 1947 the intense struggle to reroute, control, make strategic use of, or cross the Yellow River became an important metaphor for the battle to control China.

The Yellow River and Strategic Breach in Historical Context

The Yellow River, a “restless, unpredictable, and dangerous stream” known as both the cradle of Chinese civilization and “China's Sorrow,” created major challenges and opportunities for Chinese states and riverine communities long before the 1938 breach (Dodgen Reference Dodgen2001: 11; Lary Reference Lary2001: 192; Pietz Reference Pietz2015: ch. 3). The river, which runs for 3,400 miles from the Tibetan Plateau to the Bohai Sea, picks up enormous amounts of silt as it flows through a plateau of fine-grained loess soil between Shaanxi and Shanxi. When the river's current slows as it emerges from the mountains and flows east across the flat North China Plain, approximately one-third of the silt picked up in the loess highlands settles on the riverbed (Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 13–15). The buildup of silt causes the riverbed to rise steadily, “at an average rate of about three feet per year.” Before the advent of human intervention in the form of dikes, “sedimentation raised the river until it poured over its banks and spread across the landscape, eventually carving a new channel to the sea,” and wreaking havoc on riverine communities in the process (Marks Reference Marks2012: 89; Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 16).

The sharp variation in the Yellow River's flow made life on the North China Plain even more precarious. Because 50 to 60 percent of the annual rainfall in the Yellow River area falls between June and August, the river changed from a relatively small stream to a “massive torrent” during the summer monsoon season. Aware of the danger posed by flooding, Chinese rulers began diking the Yellow River as early as the seventh century BCE. By the Qing period (1644–1912), the river was “hemmed in by dikes that stretched eight hundred kilometers,” from Henan to the sea (Dodgen Reference Dodgen2001: 11–13, 3; Marks Reference Marks2012). These massive dikes, some of which were “up to sixty feet tall at their crest,” were built specifically to withstand the force of the river during the summer high-water season (Lary Reference Lary, Selden and Alvin2004: 144). Perhaps because the Chinese state historically devoted so many resources to controlling Yellow River floodwaters, Chinese rulers also proved willing to manipulate the river in dramatic ways for both strategic and statecraft purposes. Some rulers and officials of the Northern Song dynasty (960–1127), not unlike the Nationalist leadership in 1938, argued that the harm diverted floodwaters would cause the land and people of one locale was justifiable if it benefited the imperial state as a whole and turned the river into a defensive barrier against invaders (Zhang Reference Zhang and Meinert2013: 143–59). In 1128, a Song governor named Du Chong intentionally breached the Yellow River dike near Kaifeng in an unsuccessful attempt to use flooding to save the capital from invading Jurchen Jin (1115–1234) forces. This strategic breach shifted the river south, unleashing an “ecological catastrophe” that was the origin of an even more major course change. By the end of the twelfth century (1194), after nearly a millennium of emptying into the sea north of the Shandong peninsula, the Yellow River captured the lower course of the Huai River, and began to enter the sea south of the peninsula (Lamouroux Reference Lamouroux, Elvin and Ts'ui-jung1998: 545–46; Marks Reference Marks2012: 153).

Controlling the Yellow River became even more complex after the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) completion of the Grand Canal, which crossed the Yellow River and incorporated part of it as it carried tribute grain from the Yangzi valley to the North China Plain (Dodgen Reference Dodgen2001: 1–3; Pietz Reference Pietz2002: 9–12). Historian Ma Junya argues that Ming and Qing rulers (1368–1644), like their Northern Song and Nationalist counterparts, chose to manipulate the Yellow River in ways that placed broad state interests over the well-being of people in a particular region. The Ming and Qing states shifted potential flooding south to the Huai River, thus prioritizing the transport of tribute grain using the Grand Canal over the livelihood of people in the Huai basin (Ma Reference Ma2010: 75–84). Water-control efforts on the lower Yellow River “reached their zenith” in the early eighteenth century, explains Pietz, but a century later the beleaguered late-Qing state was “struggling with insolvency,” and “simply could not keep up with the increasing demands of water management” in the complex Yellow River-Huai River-Grand Canal matrix. When a series of dike ruptures occurred in the 1840s and early 1850s, the Qing state was unable to mobilize the resources to deal with the buildup of silt and the increased pressure on the dikes (Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 64–65). In 1855 a serious breach in Henan precipitated another major course change. After emptying into the sea south of the Shandong Peninsula since the 1100s, the Yellow River adopted the northern course that it would follow until the 1938 breach.

Before the Japanese invaded China proper in July 1937, yet another dramatic course change seemed unlikely. Well aware of “the traditional Chinese notion that political legitimacy could be enhanced by a state's success in ‘ordering the waters,’” the Nationalist state took concrete steps to reassert hydraulic control in North China as soon as it reunified the country and established a national government in Nanjing in 1927. The new government established the Huai River Conservancy Commission in 1929, followed by the Yellow River Conservancy Commission (YRCC) in 1933, and encouraged Chinese and foreign engineers to collaborate on modernist projects that aimed to both manage the Yellow River and exploit it for development purposes. It also conducted a “massive relief effort” after the 1935 Yellow River flood (Li Reference Li2007: 306; Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 87–92).

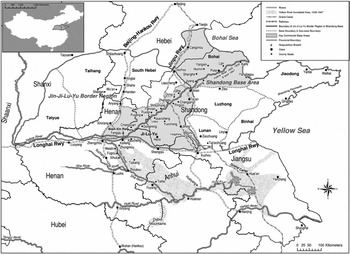

Less than a year after the Japanese invasion, however, China's military situation was so dire that the Nationalist government made the decision to deliberately unleash the river it had worked so hard to control. The Nationalist capital, Nanjing, had fallen in December 1937 and its residents had been massacred by Japanese troops. The Chinese government relocated to Wuhan, but by early June 1938 that temporary capital was also in peril. The Japanese army was advancing westward toward the city of Zhengzhou, a major city in Henan Province and the locus of the strategically crucial railway juncture between the north-south Beijing-Hankou Railway and the east-west Longhai line (Lary Reference Lary2001: 196–98; Reference Lary, Selden and Alvin2004: 143–47). The capture of Zhengzhou would have enabled the Japanese to use the Beijing-Hankou line to rush troops directly to Wuhan (see figure 1). “There was a serious chance that the entire Chinese war effort would collapse,” writes Rana Mitter. Chiang Kai-shek and Nationalist military commanders thus ordered troops to break the southern dike of the Yellow River at Huayuankou, a village north of Zhengzhou, with the aim of halting the enemy's advance and buying time for the Chinese armies and leadership to evacuate Wuhan (Mitter Reference Mitter2013a: 157). The Nationalist leadership understood the repercussions of unleashing the river, but like their predecessors in imperial China believed that the harm caused by strategic flooding was justifiable. “It is clearly known that the sacrifice will be heavy,” the Western Henan Divisional Command wired Chiang Kai-shek on June 3, “but with the urgent need to save the nation the pain must be endured” (Muscolino Reference Muscolino2015: 26).

FIGURE 1 The Yellow River and the Chinese Civil War, 1946–47 (see supplementary material for large format).

On June 9, with Japanese forces only 30 miles away, Yellow River water began flowing through the opening at Huayuankou. Within days the strategic breach widened into a 5,000-foot-wide break, causing the Yellow River to depart from the northern course it had followed since 1855. As it split into several channels that spread over the plain and flowed southeast instead of northeast, the river inundated much of eastern Henan, joined the Huai River and flooded large swaths of northern Anhui, and finally inundated northern Jiangsu as it flowed toward the sea (Lary Reference Lary2001: 199–201; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiao, Yangdong and Mingfang1994: 249–50; Muscolino Reference Muscolino2015: 55). The massive flood postponed by five months but did not stop the Japanese advance on Wuhan, which fell in October 1938. It did buy the Chinese government time to retreat from Wuhan to Chongqing, and also prevented the Japanese from taking some of the flooded areas of Henan and Anhui (Lary Reference Lary2001: 201–2; Van de Ven Reference Van de Ven2003: 226). The Nationalist government did not take responsibility for breaching the dike during the war, but instead blamed Japanese warplanes for causing the disaster by bombing the Yellow River dikes. The Japanese denied the charge, and the international press began attributing the breach to the Chinese within a few weeks of the event. In contrast, China's wartime press upheld the government's account, and even Communist newspapers refrained from holding the Nationalist leadership responsible for the catastrophe until after Japan's defeat (Dagongbao, June 12, 1938; Edgerton-Tarpley Reference Edgerton-Tarpley2014: 460–63; Reference ribaoXinhua ribao, June 12, 1938). The breach and flood destroyed rural infrastructure and brought great misery and chaos to people living what came to be called the Yellow River Inundated Area, or Huangfanqu. The catastrophic flooding killed more than 800,000 people in Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu, and turned close to 4 million people into refugees (Li et. al Reference Li, Xiao, Yangdong and Mingfang1994: 255–56; Mei Reference Mei2009; Muscolino Reference Muscolino2015: 31; Qu Reference Qu2003).

The strategic breach had a markedly different impact on riverine communities along the pre-1938 course of the Yellow River in Hebei and Shandong. Initially the sudden disappearance of the river posed a hardship for transport workers and fishing communities that depended on the river for their livelihood. Of the roughly 5,000 junks engaged in fishing and transport work along the Yellow River in northeastern Shandong before 1938, only about 100 remained by 1947. The rest were either sold when the river shifted south, fell into disrepair over the years, or “were used for firewood by the Japanese when they were in this area” (Barnett c. Reference Barnett1947: 7). For many who had lived in the shadow of the Yellow River since 1855, however, the river's absence was a great boon. First, the course change sharply reduced the risk of summer flooding, which had posed a constant threat to farmers and salt workers situated along the river's northern course. Dikes in the Hebei-Shandong-Henan border area had breached once every two years on average in the 25 years before the breach, and many villagers alive in 1946 would have experienced the serious flooding that struck the area in 1931, 1933, and 1935 (Thaxton Reference Thaxton1997: 21, 86; Xinhua ribao, April 11, 1946). The river's absence also meant that it was no longer necessary for riverine communities to provide their share of the copious amount of labor and materials required to repair the dikes each year (Barnett c. Reference Barnett1947: 3–4). Finally, some farmers profited from the course change in even more direct ways. When the river dried up, nearly half a million people moved into the dry riverbed, where they grew crops, planted trees, and gradually formed 1,400 new villages (Zhou Enlai to General Marshall, May 18, 1946, GL5-1946-9, Yellow River Conservancy Commission Archives, Zhengzhou [YRCCA]). Postwar aerial views of the river's old course, noted the official history of UNRRA, showed “practically the entire area between the dikes, which varied from one to four or five miles in width, to be under intensive cultivation” (Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 436).

The Decision to Close the Breach

Pressured by representatives from the flooded area and eager to bolster their legitimacy by undoing the damage caused by the breach, in March 1940 the Nationalist government announced that once the Japanese were defeated, the breach would be closed and the river returned to its northern course (MHS 2009: 218).Footnote 4 In the fall of 1944, Chinese government planners drew up an ambitious plan for closing the mile-wide breach at Huayuankou, repairing the dilapidated dikes that ran for more than 400 miles along each side of the river's northern course between Huayuankou and the sea, and restoring agricultural production throughout the entire Yellow River Inundated Area (Huanghe shuili weiyuanhui [HSW] 2004: 183; Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 431–32). People living within or alongside the dry bed of the river's pre-1938 course strongly opposed the diversion plan. Indeed, disagreements over which region would have to bear the burden of managing the Yellow River were common after major course changes. For example, after the 1855 breach caused the river to leave its southern course and flow to the sea north of the Shandong Peninsula, Qing officialdom spent three decades debating how best to regain control over the troublesome river. In a reversal of the situation in 1946, people in late-Qing Shandong, eager to see the river depart their province, advocated plugging the 1855 breach and returning the river's flow to its pre-1855 southern course. In contrast, advocates in Anhui and Jiangsu, glad to be free of “China's Sorrow,” championed making the northern course permanent by building dikes along it. Concerned by the high cost of trying to return the river to its southern course, and beset by domestic rebellions and the threat posed by Western imperialist powers, the Qing state in the end “had little choice but to accept the new course of the Yellow River” (Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 67).

The postwar Nationalist state may have been in a similar position had it not been for two important factors. First, the Nationalist state had compelling strategic and political reasons to prioritize diverting the river north rather than accepting and regularizing its postbreach southeastern course. Chiang Kai-shek hoped that “reimposing hydraulic stability” in the inundated area would boost support for the Nationalist government there, while diverting the river north would divide Communist forces in Shandong Province, a “principal battlefield in the CCP-GMD conflict” (Lai Reference Lai2011: xv; Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 119; Westad Reference Westad2003: 169). Moreover, unlike its late-Qing predecessor, Nationalist China did not face the enormous cost of rerouting the Yellow River on its own; substantial transnational aid provided by UNRRA made the endeavor more feasible (Muscolino Reference Muscolino2015: 201; Todd Reference Todd1949: 48–51). The Nationalists championed the use of modern technology and international aid in the struggle to rebuild war-ravaged China (Henan Minguo ribao, September 2, 1943). After UNRRA was established in November 1943 with the aim of rehabilitating countries that had been occupied during the war, the Chinese government made a formal request for 2,200 foreign experts, and supplies totaling $945 million dollars to be used for agricultural and industrial rehabilitation as well as health and welfare services. UNRRA historian George Woodbridge termed this request “moderate,” given China's enormous population and level of devastation, but it exceeded what the organization could provide. Still, UNRRA's China program was its largest in value, and was second only to Germany in terms of staff. UNRRA ultimately delivered $517.8 million worth of supplies to China, compared to $477 million to Poland and $418 million to Italy (Greene Reference Greene1951: 100–1; MHS 2009: 220; Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 372, 376–77, 453).

The Yellow River project was “perhaps the best known among all the specific rehabilitation enterprises sponsored by UNRRA,” writes Woodbridge, as well as “one of the most difficult in execution, technically, financially, and politically.” To push forward the project, in late 1944 the Chinese government asked UNRRA to send a highly experienced engineer, 20 skilled technicians, 5,000 tons of heavy construction equipment, and 109,000 tons of grain for the workers (MHS 2009: 221; Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 431). UNRRA officials responded with enthusiasm. Convinced that closing the breach would reclaim 2 million acres of cropland flooded due to the course change, they called diversion of the river the “most important contribution UNRRA can make to the agricultural rehabilitation of China” (New York Times, January 20, 1946: 20; Todd Reference Todd1949: 40).

Initially it looked as though the enormous task of rechanneling the Yellow River might become a rare area of cooperation for the Nationalists and Communists, and a symbol of hope for those eager to forge a united China across ideological lines. In late 1945, UNRRA selected O. J. Todd, a respected American hydrologist who had conducted river work in China from 1919 to 1938, as top engineer and UNRRA advisor for the Yellow River project.Footnote 5 UNRRA agreed to work through the Chinese National Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (CNRRA), a partner agency formed by the Nationalist government, to manage relief efforts within China (Todd Reference Todd1973: 3–4, 144, 152; Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 374). Because UNRRA's agreement with China assumed the country would soon be unified under the Nationalists in coalition with the Communists, CNRRA was expected to handle the distribution of supplies in Communist as well as Nationalist-controlled areas.Footnote 6 Eager to enlist CCP support for the Yellow River project, shortly after his arrival in China in December 1945, Todd met with Zhou Enlai, a member of the key decision-making organ in the CCP's Central Committee and the “main external conveyor of CCP policy during the civil war.” Zhou pledged his support for the endeavor, and commented positively on UNRRA's goal of restoring China's food-producing capacity. Zhou voiced CCP approval more formally in a telegraph he sent to CNRRA head Jiang Tingfu on March 1, 1946 (Fisher Reference Fisher1977: 193–94; Todd Reference Todd1973: 144; Westad Reference Westad2003: 41; Zhou to Marshall, May 18, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA).

The early cooperation on the Yellow River project reflects the fact that early 1946 was a time of relative optimism in terms of relations between the rival parties. In December 1945, US President Harry Truman had sent General George C. Marshall, the wartime head of the US Joint Chiefs of Staff, to China to mediate between the Nationalists and Communists in a “dramatic move to prevent a full-scale civil war.” The Communists welcomed Marshall's arrival, hoping to use his mediation “to get a break in a war that was going badly for them.” The high-profile Marshall negotiations resulted in a cease-fire, and the two parties agreed to a truce that began on January 13, 1946 (Lew Reference Lew2009: 33; Westad Reference Westad2003: 31, 44). With the apparent support of both parties, preparation for the closure project began with the construction of an eight-mile railway spur that connected the closure site at Huayuankou to the Beijing-Hankou Railway, and the shipment in January 1946 of “seventeen carloads of engineering equipment and food” from UNRRA (New York Times, January 20, 1946: 20; Todd Reference Todd1949: 49). Work at Huayuankou officially commenced on March 1, 1946, and the original goal was to close the breach by July 15 of that year. Tens of thousands of laborers, most of them from the inundated area, were employed at the breach site and paid in part by a daily allotment of 2.5 pounds per person of flour imported from the United States by UNRRA (HSW 2004: 197–98; Todd Reference Todd1949: 48–51).

Behind the scenes, however, opposition to the breach-closing project in Communist-controlled base areas along the river's pre-1938 course, as well as key events in the Chinese Civil War, meant that Communist support for the project was contested and tenuous. During the Sino-Japanese War of 1937–45, the Japanese occupied most of North China, but were spread too thin to fully control the countryside. The Communists capitalized on that situation by organizing guerrilla resistance from bases located in rural areas behind Japanese lines (Thaxton Reference Thaxton1997: 240). After the strategic breach, the dry bed of the Yellow River ran through Japanese-occupied territory, from Kaifeng in Henan Province, through Dongming in southern Hebei, and northeast across Shandong into the Bohai Sea. When the Japanese withdrew, the Communists came to dominate much of the river's northern course, though the Nationalists held the railways and cities. The western half of the old riverbed, or the section that ran through 20 counties between Kaifeng and Jinan (see figure 1), was located in the Ji-Lu-Yu (Hebei-Shandong-Henan) base, one of the four bases administered by the Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu (Shanxi-Hebei-Shandong-Henan) Border Region government founded by the CCP in 1941. The lower reaches of the Yellow River, which ran northeast through 11 counties between Jinan and the sea, was largely under the control of the Bohai subdistrict of the Shandong Base Area (Goodman Reference Goodman1994: 1007, 1010–11; MHS 2009: 224, 229).Footnote 7

During the war with Japan, Communist bases located behind enemy lines had of necessity acted with some degree of autonomy from the CCP headquarters in Yan'an, Shaanxi (Goodman Reference Goodman1994: 1010–11, 1024). With the Japanese gone, by early 1946 Yan'an was tightening its administrative control over its base areas, which the Communists came to term “liberated areas” (jiefangqu). Nevertheless, due in part to the wartime legacy of altering, or sometimes even ignoring directives from above based on local circumstances (DeVido Reference DeVido, Chongyi, David and Goodman2000: 18), border region officials and residents of the Ji-Yu-Lu and Shandong base areas did not hesitate to voice their reservations about the closure plan. After UNRRA inspectors arrived in Shandong in January 1946 to examine the dikes there in preparation for the diversion, Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu Border Region authorities telegraphed central government authorities in Yan'an to explain that there was strong local opposition to the plan. Cadres in the Ji-Lu-Yu base argued that returning the river to its old course would be extremely harmful to the liberated areas due to the extensive flooding that would result (Ji-Lu-Yu Huang weihui, GL2-1947-17, YRCCA; MHS 2009: 222).

After looking into the matter, the CCP's Central Committee affirmed Zhou Enlai's initial support for the Yellow River project by emphasizing its importance for the entire nation. On February 13, 1946, the center sent the following directive to Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu and Shandong Base authorities: “Returning the Yellow River to its old course has different advantages and disadvantages for North China and Central China, but returning the river occupies the dominant position in the country as a whole; we have no way to oppose it” (HSW 2004: 197; MHS 2009: 222). According to an explanation published in the Communist-operated Xinhua ribao (New China daily), the Communists agreed “in principle” with the closure plan because while the Yellow River alone brought many disasters, the catastrophes created when it flowed southeast and combined with the Huai River were on a far greater scale of magnitude (Xinhua ribao, May 30, 1946).Footnote 8 Upon receiving orders from the center, base area officials began establishing water conservancy bureaus that would organize the dike-repair work along the river's dry bed (MHS 2009: 222). At the same time, the directive from Yan'an did not prevent people in riverine communities, many of whom had learned mobilization tactics from Communist organizers during the war with Japan (Wou Reference Wou1994: chs. 5–6), from taking action to protect their villages when they learned that the closure work at Huayuankou had commenced. In the spring of 1946 thousands of people in the Ji-Lu-Yu area gathered in the old riverbed to march and petition against the breach closure, and some even planned to construct horizontal dikes in the riverbed to prevent water from flowing east. When informed of this, Zhou Enlai immediately cabled Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu authorities to order them to stop the construction of such dikes, and to push forward the dike-repair work to ensure the safety of people living along the river's old course (MHS 2009: 223).

Due to the importance of the Yellow River project and the many competing interests involved, representatives from CNRRA, UNRRA, and the CCP met at Kaifeng, Heze, Nanjiing, and Shanghai to negotiate specific terms for closing the breach. The first set of talks was held in Kaifeng in March 1946. Voicing a perspective that would surface repeatedly during negotiations, Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu representative Chao Zhefu argued that repair of the old riverbed and its dikes must be completed before the breach closure, and the Nationalist government must provide relief funds for the people residing in the old riverbed. In contrast, Nationalist representatives led by Zhao Shouyu, the head of the YRCC, urged that the breach should be plugged as quickly as possible so that the work could be completed before the summer flood season (MHS 2009: 223–24). The rival parties continued their negotiations in April in Heze, Shandong. Before the meeting, a group of inspectors from UNRRA and the YRCC joined Communist representatives in conducting a survey of the river's old course through 17 different counties in southern Hebei and Shandong. The inspectors found that more than 30 percent of the 1,500 kilometers (932 miles) of dikes lining both sides of the pre-1938 course had been damaged over the previous eight years, the riverbed had filled with silt and must be dredged, and nearly half a million farmers had moved into the dry bed. Given that information, representatives from both parties signed the Heze Agreement of April 15, which stated that the closure of the breach would occur only after the completion of the necessary repair work along the river's old course, and funds for the evacuation and relief of the riverbed residents should be provided (MHS 2009: 224–25; Zhou to Marshall, May 18, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA). The timing of the closure, however, as well as precise terms for compensating the riverbed inhabitants, became sticking points that were never fully resolved.

Despite the Heze Agreement, when it became clear that the Nationalists were making rapid progress on the closure project at Huayuankou, on May 3 roughly 150,000 people from the Ji-Lu-Yu area held a rally and published an open telegram voicing their opposition. The protestors stated that if Guomindang authorities insisted on rushing to close the breach without first restoring the dikes along the lower reaches, “the people will surely be forced to defend themselves” (MHS 2009: 226; Xinhua ribao, May 17, 1946). In what appears to be an attempt to discredit the Nationalists and rally public opinion against an early closure, in mid-May the Xinhua ribao,Footnote 9 the main Communist-run newspaper published in Nationalist-controlled territory, at last broke with the wartime narrative that Japanese planes had caused the 1938 breach, and publicly blamed the Nationalists for bringing about the calamitous course change in a failed attempt to check the Japanese advance (Edgerton-Tarpley Reference Edgerton-Tarpley2014: 460–64; Xinhua ribao, May 14, 1946).

By that point opposition to the Yellow River project in the Ji-Lu-Yu base was strong enough to warrant General Marshall's intervention. Because Communist representatives in western Shandong were “protesting the execution of this project due to their fears of flooding,” wrote Marshall to Zhou Enlai on May 18, “it has therefore been suggested that you might wish to reaffirm your stand of 1 March with a view to directing the Communist delegates in western Shantung to give complete cooperation to UNRRA and CNRRA.” Zhou's response to Marshall demonstrates that the degree of resistance in the Ji-Lu-Yu base had complicated Yan'an's support for the project. Zhou acknowledged that he had in March voiced approval for the closure plan, but explained that he now needed assurance that the interests of the people living in the dry riverbed would be protected and flooding along the old course would be prevented (Marshall to Zhou, May 18, 1946; Zhou to Marshall, May 18, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA).

UNRRA representatives tried to allay Communist concerns when the involved parties continued their negotiations concerning the Yellow River project, this time in Nanjing. On May 18, Franklin Ray Jr., acting director of the UNRRA China Office, and chief engineer Todd discussed with Zhou Enlai the work involved in repairing the river's old course, and came to an agreement that, “All materials and foodstuff needed for the completion of this work will be provided by UNRRA [through CNRRA] and this supply shall not be affected by political and military affairs” (MHS 2009: 227–28; “The Oral Agreement,” May 18, 1946, GL5-1946-11, YRCCA). Understandings reached at the top continued to be undermined by local actors, however. Just a week after the Nanjing negotiations, Todd wrote to Zhou Enlai from Zhengzhou to report that “a rather serious act of sabotage and kidnapping” had recently occurred at a quarry where UNRRA was obtaining rock needed for the breach closure. Todd's investigation led him to believe that the destruction of valuable air compressors provided by UNRRA had been conducted by armed men from a Communist area where people opposed to the diversion plan, so he requested Zhou's assistance. Zhou did step in to see that the personnel seized at the quarry were released (June 23, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA; Todd to Zhou, May 26, 1946). Nevertheless, the incident reminds us that the CCP was not a monolith, and the actions of its supporters were “often conditioned by the local context in which they functioned” (Saich Reference Saich1994: 1005).

UNRRA and Nationalist officials continued to press for a July 1946 closure date despite CCP opposition (HSW 2004: 197; Todd to Zhou, June 12, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA). In the end, the river, combined with technical difficulties, made this goal impossible to meet. On June 25, the water began to rise prematurely in the upper reaches of the Yellow River. When floodwater reached the Huayuankou breach, it washed away much of the stone material and trestle work erected since March. By mid-July it was clear to all that the attempt to close the breach before the high-water season had met defeat (Dagongbao, July 6, 1946; July 20, 1946; MHS 2009: 233). Once rising waters ended the threat of an immediate closure, the Communists turned their attention to obtaining their share of UNRRA assistance for repairing the river's old course. On July 8, Zhou Enlai wrote to General Marshall to protest that the transport of flour for the dike workers in Communist areas was far too slow, and that while dike work in the Ji-Lu-Yu area was proceeding apace, “not a single cent” had reached the base area from the outside. “Up to the present the Communist Liberated Areas have only received 0.5 percent of the total quantity of relief supplies shipped to China by UNRRA,” he wrote; “it is far from being fair and just” (“Memorandum for Marshall,” July 8, 1946; July 10, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA). The official history of UNRRA acknowledged that due in part to civil war conditions, shipments to Communist areas “amounted to between 2 and 3 per cent by weight, or 4 and 5 per cent by value, of the total UNRRA supply program for China” (Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 389).

Between July 18 and July 22, Communist, Nationalist, and UNRRA representatives met again in Shanghai to discuss ongoing differences concerning the Yellow River project. The representatives agreed that all closure work at Huayuankou would be suspended during the summer high-water period, and would resume in mid-September, with the aim of completing the breach closure by late December (Dagongbao, July 23, 1946). The delegates also concurred that CNRRA would provide another 2 billion yuan to Communist authorities for dike repair, in addition to the 4 billion already delivered, and would send 8,600 tons of flour for dike workers in Communist-controlled areas (“Memorandum of Agreement,” July 22, 1946, GL5-1946-11, YRCCA). The most contentious issue at the Shanghai conference was funds for the people living in the dry riverbed. Communist representatives, who wanted to compensate the riverbed inhabitants for their losses as well as provide basic relief, requested a minimum of 30.4 billion yuan for them. In contrast, the Nationalists argued that because the riverbed people had no ownership rights over the riverbed land, there was no reason to provide compensation, and a sum of 8 billion yuan for relief would suffice (Dagongbao, July 17, 1946; MHS 2009: 234). Finally, after tense negotiation, all parties agreed that CNRRA director Jiang Tingfu would request a total of 15 billion yuan from the National Treasury for the relief, relocation, and rehabilitation of the riverbed residents. Four billion yuan was to be made available in August, September, and October, respectively, and the final 3 billion would be delivered in November (“Memorandum of Agreement,” July 22, 1946, GL5-1946-11, YRCCA; see also Dagongbao, July 23, 1946; MHS 2009: 232–36). As late as July 1946, then, the effort to forge a national consensus regarding the Yellow River appeared to have a reasonable chance of success. Events on the ground along the river's old course, however, soon rendered obsolete the agreements reached in Shanghai.

Descent into Civil War: The Politicization of Flooding

During the first half of 1946 the Marshall peace talks kept the conflict between the Nationalists and Communists from devolving into a full-scale civil war, though serious fighting between the rival parties occurred in Manchuria after the Soviet withdrawal in April (Bernstein Reference Bernstein2014: 376–79). By the end of June the negotiations were deadlocked, and a second truce—the so-called Manchuria armistice arranged by General Marshall and promulgated on June 7—came to an end without bearing fruit (New York Times, June 8, 1946: 19; July 1, 1946: 14). The Nationalists, aiming to destroy the main military forces of the Communists, then launched a general offensive against Communist-held areas (Lew Reference Lew2009: 37, 40–41; Westad Reference Westad2003: 40–48). Between July 1946 and June 1947, the Nationalists recaptured county seats and communication lines north of the Yangzi River, while the Communists followed a defensive policy characterized by “mobile warfare and strategic withdrawal from the towns back into the countryside” (New York Times, July 28, 1946: 1, E5; Pepper Reference Pepper1999: xiii–xiv). As part of their offensive, soon after the July conference in Shanghai Nationalist forces commenced an attack on the Ji-Lu-Yu liberated area. By late September, the Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu Field Army, which had the reputation of being “the most successful unit in the Communist Army,” had to withdraw from the Ji-Lu-Yu headquarters in Heze as the Nationalists gained the upper hand south of the Yellow River (Lew Reference Lew2009: 49–50; MHS 2009: 236). By year's end the Guomindang had captured 24 of the 35 county seats previously controlled by the Ji-Lu-Yu Communists. “Gloom pervaded the local Party organization,” writes Suzanne Pepper (Reference Pepper1999: 301).

The Nationalists resumed work on the breach closure in early October after the flood season ended, but with the two sides engaged in active warfare, did not provide any of the agreed-upon 15 billion yuan for the riverbed residents that fall (MHS 2009: 237; “Preliminary Meeting,” December 2, 1946, GL5-1946-3, YRCCA). On November 3, Zhou Enlai wrote to General Glen Edgerton, director of UNRRA's China Office, to explain that the Nationalist offensive against the liberated areas, combined with the government's failure to provide the promised relief funds, had prevented the Communists from carrying out dike repair and relocation work as scheduled. He thus requested the immediate suspension of the closure work (Zhou to Edgerton, November 3, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA). The Nationalists instead doubled down on their attempt to plug the breach by the end of the year. On December 27, workers at Huayuankou released some Yellow River water back into the old course in an attempt to speed the closure by relieving pressure on the mouth of the gap (Dagongbao, January 16, 1947; HSW 2004: 214). Headwaters reached the Bian-Xian Railway by January 5, 1947, and arrived in Zhangqiu on January 19. The water was shallow and slow moving, but some villages in the old riverbed flooded (Dagongbao, January 6, 1947; Xinhua ribao, January 9, 1947; January 25, 1947). In early January Chiang Kai-shek ordered water conservancy officials to complete the closure without delay, and instructed the transportation bureau to “stop military transport rather than impeding the transport of stones for plugging the breach.” Later that month more than 60,000 workers were assembled at the breach site. They worked “day and night” to seal the gap, which had by that point been reduced from a mile-wide break to “a swirling gap less than 500 feet wide” (Dagongbao, January 16, 1947; Los Angeles Times, January 21, 1947: 4; MHS 2009: 237–39).

The politicization of the Yellow River project came to a head in January 1947, as both the Communists and the Nationalists sought to use the breach closure to denigrate the rival party and bolster their own legitimacy. December 1946 through January 1947 was a fraught time for China domestically and with regard to Sino-US relations. On December 18, President Truman issued “a major statement on China policy reaffirming that the U.S. would not become directly involved in the KMT-CCP conflict.” A week after his statement a young Beijing National University student was raped by a US marine, leading to massive student-led anti-American demonstrations across the country. On January 6, General Marshall was recalled to Washington, and on January 29 the United States announced “the formal termination of its mediation effort” (Pepper Reference Pepper1999, xiv–xv; Shaffer Reference Shaffer2000: 36–38). Moreover, after the relative success of their late-summer offensive, in January 1947 the Nationalists launched the so-called Strong Point Offensive. In it Chiang Kai-shek, aiming to end the war, transferred “the bulk of his elite forces” east into Shandong and west into Shaanxi with the aim of using two “large-scale pincer maneuvers that would first destroy the Communists on the east and west flanks,” and then converge in the center to finish them off. The heaviest campaigning was in Shandong, explains Lew, where Communist field armies were outnumbered nearly three to one (Lew Reference Lew2009: 55–57).

The Nationalist state's record of using the Yellow River against the Japanese on multiple occasions (Muscolino Reference Muscolino2015: 34–41; Xinhua ribao, August 21, 1946), combined with the fact that the Strong Point Offensive coincided so closely with the Guomindang's final push to close the breach, has convinced scholars of the Chinese Civil War as well as contemporary observers that tactical concerns influenced the timing of the closure. Sealing the breach, explains Westad, allowed the Nationalists to place “half a mile of water” between the two main Communist armies in North China, Liu Bocheng's Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu Field Army north of the Yellow River's pre-1938 course, and Chen Yi's East China Field Army in southern Shandong (Belden Reference Belden1949: 354–55; Westad Reference Westad2003: 169, 112). “In the end the strategic factor came to determine the actual time of the gap closure,” judged UNRRA representative Irving Barnett in his 1953 report. Returning the Yellow River to its northern course quickly was “highly favorable to the Nationalist troops,” he observed, “since it would cut the forward forces of the Communists from their supply source, north and west of the pre-1938 river course” (Barnett Reference Barnett1953: 27–28).

The Communists responded with fury to the late December discharge of water into the river's old course and the rush to close the breach. The Guomindang had broken all prior agreements when it released Yellow River water without consulting Communist representatives and before the necessary repairs downstream were complete, wrote Dong Biwu, Chairman of the Chinese Liberated Areas Relief Association (CLARA), to UNRRA in early January. As a result, continued Dong, the “life and property of several million inhabitants along the lower stream is now being gravely endangered.” Dong proposed that all closure and diversion work should be postponed for five months, until the necessary repairs and evacuations were complete downstream and the Nationalists had provided the long-awaited 15 billion yuan for the riverbed residents. He pressed UNRRA to withdraw all its aid for the closure project if the Nationalists would not agree to the delay (Dagongbao, January 6, 1947; Dong Biwu to Edgerton, January 3 1947, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA). On January 8, Zhou Enlai gave a major speech at Yan'an that sought to foster domestic and international criticism of the Nationalist state's handling of the closure. Guomindang authorities, he charged, had military rather than altruistic motives for rushing to close the breach. “We ask compatriots throughout the nation and international figures with a sense of justice to take a stand for humanitarianism,” called Zhou. “Arise as one to oppose and quickly halt the Guomindang government's vicious breach closure and water releasing operation” (MHS 2009: 239; Xinhua ribao, January 10, 1947: 2).

The Nationalist state countered Communist allegations by blaming CCP intransigence for the standoff and highlighting pragmatic and humanitarian reasons for an immediate closure. The influential Dagongbao (The impartial),Footnote 10 an independent but relatively pro-Guomindang newspaper, carried state press releases from the Central News Agency claiming that the YRCC had conducted the closure work in accordance with agreements reached with the Communists the previous year, while the CCP had concocted one problem after another in a deliberate attempt to delay the closure. Moreover, Communist troops had reportedly gone so far as to try to disrupt the diversion work by shooting at river works officials and international engineers sent to inspect the dikes along the lower reaches (Dagongbao, January 5, 1947; January 8, 1947; see also Shenbao, January 12, 1947).

On January 16, Peng Xuepei, the government's minister of information, met with journalists to provide a lengthy and technical explanation of why closing the breach could not be delayed for five more months as the CCP proposed. According to Peng, the breach must be plugged straightaway, while the water level was low and the flow capacity was only about 1,000 cubic meters (gongchi) per second. After early February, chunks of melting ice would raise the water level and break the embankments, undoing much of the previous breach work. Problems would increase in late March, he continued, when the spring high-water period began and the river's flow capacity would increase to 4,000 cubic meters per second. A five-month delay was thus counterproductive (Dagongbao, January 17, 1947; see also Dagongbao, January 11, 1947). Peng also downplayed CCP warnings that an immediate closure of the breach would bring disaster upon the riverbed residents. Everyone had known all along that the river would return to its old course, he claimed, so Communist publicity about the issue was overstated. The riverbed inhabitants would receive relief, and their homes were temporary dwellings that could easily be moved. Moreover, since the late-December release of water, roughly a tenth of the Yellow River's flow was already running through the old course, but it was shallow and flowed more slowly than a person could walk, and much of it was absorbed by the dry riverbed. The Communist claim that several million people would be swept away by the river's return was thus “sensationalist fear-mongering.” This press report, filled with precise measurements and technical information, demonstrates the Nationalist government's confidence that modern hydrology and technology had propaganda value, and could ultimately solve the problems created by the course change (Dagongbao, January 17, 1947; see also Edgerton-Tarpley Reference Edgerton-Tarpley2014: 463).

During the January war of words, leading newspapers and Nationalist officials also emphasized humanitarian reasons for an immediate closure. A Dagongbao correspondent who interviewed laborers toiling at the breach site in the freezing January weather, for instance, found that more than 85 percent of them were from inundated counties in Henan. Floodwaters had turned these people into “homeless wanderers” for close to nine years, noted the reporter. “All they ask,” he continued, “is for the Yellow River to be returned to its old course early so that they can return to farming” (Dagongbao, January 12, 1947). According to a state news agency release, upon learning of Communist opposition to the closure timeline, “the masses in the Yellow River Inundated Area” sent representatives to Huayuankou to implore the breach closure bureau there not to stop its work. If the Communists continued to block the closure, warned the representatives, flood refugees would themselves “voluntarily come and throw stones to plug the breach” (Dagongbao, January 11, 1947; see also Dagongbao, January 9, 1947; Shenbao, January 13, 1947). Minister of Information Peng Xuepei contributed a numerical argument to underscore the government's humanitarian motives. Only about 150,000 riverbed people still needed to be relocated along the river's old course, claimed Peng, while sealing the breach would allow the more than 6 million people who had suffered disaster after the 1938 course change to return to their homes and farms (Dagongbao, January 17, 1947).

The CCP, however, which included in its calculations both riverbed residents and people living along the river's pre-1938 course, claimed that 6 million people would be put at risk by a hasty breach closure (Dagongbao, January 11, 1947). The CCP had supported the Yellow River project to relieve areas that had suffered eight years of flooding, explained Zhou Enlai, “but [we] certainly cannot restore the old inundated area and in the process create a new flood zone” (Xinhua ribao, January 10, 1947; see also January 21, 1947). The Communists also used the diversion project to criticize the Nationalist state's dependence on the United States and call into question its legitimacy and Chinese identity. For example, a January 12 editorial in the Xinhua ribao drew sharp contrasts between the Nationalist government's handling of the American marine who had raped a female student in Beijing the previous monthFootnote 11 and its treatment of the riverbed residents. “They [Guomindang authorities] are so considerate of and respectful to the American troops who humiliate our nation and murder our compatriots, but when it comes to the people of their own country they don't hesitate to release Yellow River water to flood them and their property,” charged the editorial. “Can the government directed by Guomindang authorities still be considered ‘the Chinese government?’ Can these Guomindang authorities still be regarded as ‘Chinese people?’” (Xinhua ribao, January 12, 1947).

UNRRA officials, concerned by the vehemence of CCP opposition and “reluctant to become involved in explosive civil war issues,” responded to the January dispute by arranging additional talks with both parties and pressuring the Nationalists to again postpone the final closure of the breach. In a clear sign of tension between UNRRA and the Nationalist government, Todd went so far as to tell US reporters that “the main reason for the delay. . . is the Nanking government's procrastination in providing $15,000,000,000 in Chinese national currency (about $2,500,000 in U.S. dollars) promised last July” for the relocation of the river bed residents (Los Angeles Times, January 21, 1947: 4; New York Times, January 8, 1947: 5). On February 7 UNRRA, CNRRA, and CLARA representatives once again met in Shanghai to discuss the impasse. The Guomindang government finally agreed to release the 15 billion yuan, but by that point the rampant inflation that eroded public confidence in the Nationalist government during the civil war had significantly reduced the purchasing power of this sum (HSW 2004: 219–20; MHS 2009: 239).Footnote 12 Even when the allotment was agreed upon in July 1946, the average per capita payment from the 15 billion yuan would have been barely sufficient to cover the resettlement expenses of a riverbed inhabitant, asserted CLARA representative Wu Yunfu. By spring of 1947, “[T]his sum would hardly buy a pair of cloth shoes” (Wu Yunfu to Edgerton, March 4, 1947, GL5-1946-3, YRCCA; see also New York Times, December 27, 1946: 7).

At the February 7 meeting, the involved parties also agreed to meet again in March to evaluate the state of the old riverbed before determining the final closure date (Edgerton to Xue Dubi, March 14, 1947, GL5-1946-10, YRCCA; HSW 2004: 219; Wu Yunfu to Edgerton, March 21, 1947, GL5-1946-4, YRCCA). By early March, however, it became clear that the Nationalists were unwilling to wait any longer to close the gap, and had no intention of consulting with the Communists again on the final date. At that point, UNRRA “protested very sharply” and “withdrew its personnel. . . from active participation in the final stage of the closure work” (Harlan Cleveland to Lin Zhong and Cheng Run, July 7, 1947, GL5-1946-3, YRCCA). Nationalist military authorities took control of the project from civilian engineers, so “the last stages of the closure were actually accomplished by the army” (Barnett Reference Barnett1953: 27–28; see also MHS 2009: 236–38). The Nationalists succeeded in completely closing the breach at Huayuankou on March 15, 1947, and the Yellow River began flowing back into its original course in full the next day. That May, on the symbolically charged anniversary of China's May Fourth Movement, the Guomindang held a “lavish ceremony” at Huayuankou to celebrate the success of the project (Dagongbao, March 16, 1947; Lary Reference Lary, Selden and Alvin2004: 156; Shenbao, May 5, 1947).

The Nationalist government's ability to complete such a large project during civil war and economic crisis is impressive. According to the Minguo Huanghe shi, between the official start date of March 1, 1946 and the closure date of March 15, 1947, the breach closure project cost 59.2 billion yuan, plus UNRRA supplies and equipment valued at 2.5 million US dollars (HSW 2004: 221; MHS 2009: 241).Footnote 13 Not only the “transnational subsidies” from UNRRA, but also the material and labor procured by Nationalist authorities were crucial to the success of the project. UNRRA furnished more than 5,000 tons of flour for the workers, and 9,000 long tons of heavy equipment and supplies ranging from bulldozers and barges to 2.5 million jute bags from India. For its part, the Chinese government provided “150,000 cubic meters of rock, 50,000 tons of willow branches, 1,000 tons of hemp for rope, 198,412 units of short piling and stakes, 20,000 tons of kaoliang (tall Chinese millet) stalks, 191 iron anchors, and miscellaneous supplies” for the closure project (Muscolino Reference Muscolino2015: 202; Todd Reference Todd1949: 48; Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 433). Moreover, Nationalist authorities arranged for more than 10,000 laborers to work on the closure project at any one time, and at key periods as many as 60,000 laborers worked at the breach site, more than the 35,000 to 40,000 workers employed on the Panama Canal project at the height of its construction. Laborers completed some 3 million cubic meters of earthwork, and spent a total of more than 3 million work days to close the breach (HSW 2004: 198, 219–21; MHS 2009: 239–41; Thatcher Reference Thatcher1915: 62; Woodbridge Reference Woodbridge1950, 2: 433–35).

Immediate Impact of the Closure: Boon or Calamity

For tens of thousands of people from the inundated area who conducted back-breaking closure- or dike-repair work to survive while their farms were under water, and for the even larger number of flood refugees who fled to other provinces and spent years being “bullied and humiliated” in “strange places where they had no relatives to rely on,” the successful closure of the breach was a great relief (Fugou xianzhi zongbian jishi 1986: 91–92; Song Reference Song2005: 201–3). Water receded quickly in the inundated area once the river returned to its northern course, and the number of displaced people who returned from Shaanxi and other areas “increased daily.” As of July 1947, roughly 360,000 refugees had returned to Henan's flooded area, and by the end of that summer “cultivation had resumed in 80 percent of the entire flooded area.” Like their compatriots along the pre-1938 course of the river, farmers in Henan moved into the now-dry 1938–47 riverbed to cultivate crops. By the early 1950s, “[T]he bulk of the Henan flooded area's population had returned,” finds Muscolino, and “the flooded area's agro-ecosystems returned to prewar levels of productivity” (Reference Muscolino2015: 203, 205, 208, 211, 230).

As flood refugees from Henan, Anhui, and Jiangsu began to return home, however, their compatriots living in or alongside the river's northern course were forced to flee villages inundated by the newly diverted river. Because the final stages of the breach closure were completed so rapidly, “inadequate notice was given to the riverbed dwellers of the coming of the water, and a considerable amount of damage resulted” (Barnett Reference Barnett1953: 28). On June 19, 1947, CLARA officials cited “incomplete preliminary statistics” concerning the damages that had resulted from the first three months of the river's return. Since the March closure, they reported, “hundreds of lives” had been lost, 463 villages inundated, 113,580 people rendered homeless, more than 700,000 dwellings damaged, and 4,934,779 mu (1,270 square miles) of farmland flooded (Lin Zhong and Cheng Run to Cleveland, June 19, 1947, GL5-1946-3, YRCCA).Footnote 14 An investigative report compiled by the Communist Yellow River Commission in the Ji-Lu-Yu area between January and October 1947 stated that more than 130 villages located close to the river, most of them in Fanxian, Puxian, Kunwu, and Changyuan counties, suffered extensive flooding soon after the river was diverted north. “The water level of the Yellow River rose very fast and the dikes had not been repaired for years, so villages along the river were mostly washed away,” stated the report. “The release of water brought great disaster for people in the liberated area” (Ji-Lu-Yu Huang weihui, GL2-1947-17, YRCCA).

The breach closure caused difficulties for the 11 riverine counties in the Bohai liberated area of northeastern Shandong as well. Irving Barnett was able to investigate the situation there during his 10-day inspection tour in May 1947. After traveling by steamer to Yangjiaogou, a port located south of the Yellow River's mouth in Communist-controlled territory, Barnett went by jeep to Putai and Kenli and back, then proceeded north from Putai to Huimin, and finally crossed back into Nationalist territory in Cangzhou, Hebei. As made clear by Bohai authorities, Kenli County, located at the mouth of the Yellow River, suffered the brunt of the damage in the spring of 1947. This was because the delta area in Kenli was settled primarily after the river shifted south in 1938, and thus had no prewar dikes to contain the returning waters. The Bohai government had started to build dikes in Kenli the previous year (1946), but they were still too low to provide sufficient protection. Thus 101 of the 104 villages in the Bohai area inundated between March and May were in Kenli, as were 26,635 of the 28,085 people flooded out of their homes (Barnett c. Reference Barnett1947: 1–4; notes on meeting 2).

People in Kenli knew that water would eventually flood the delta area, explained county officials, but due to the agreement reached with CNRRA and UNRRA in February 1947, they believed that they would be provided for before the floodwaters came, and that the water would not arrive unexpectedly. Instead, “[T]he telegram announcing that the gap was closed and that the water would be coming was followed immediately by the actual arrival of the flood.” When the waters came, the government mobilized 30 small junks and rushed to evacuate people, but there was insufficient time to rescue belongings. Cows were successfully evacuated because they would swim, but many donkeys, pigs, goats, and chickens drowned, and “anything made of wood was gone.” Bohai officials reported that an additional 96 villages home to 20,000 people had to be moved before the July flood season (Barnett c. Reference Barnett1947: 4–5, 9–10; notes on meeting 4). In addition to the direct damage caused by flooding, Bohai authorities emphasized the “indirect costs” imposed on people of the area due to the breach closure. Approximately 100,000 people had to be recruited to conduct dike-repair work, Barnett was informed, and the 11 riverine counties bore the brunt of the labor burden. The “enormous amount of dike work” required was draining manpower needed for agricultural labor, so authorities were organizing women and children to “fill the gap.” Moreover, due to the dearth of outside assistance, the cost of the materials needed for dike work was exacted from the area, and the local people also bore the burden of “supporting those who were evacuated from the river bed” (Barnett c. Reference Barnett1947: 3–4, 9; notes on meeting 1).

UNRRA's key role in the Yellow River project meant that after the breach closure the organization was no longer seen as an honest broker in areas along the river's northern course. When UNRRA representatives, among them Warren Sanger and D. K. Faris, visited the Ji-Lu-Yu area in May 1947 on a twofold mission to investigate incidents of Nationalist strafing along the river and observe dike-repair work in western Shandong, they met with suspicion and delays. While awaiting permission to proceed to the Communist Yellow River headquarters in Zhangqiu, a CLARA supply chief informed the observers that it was unsafe for them to visit the dikes because of the “strong current of bitter resentment against any UNRRA personnel” felt by people living along the river, who “directly associated UNRRA with the return of the Yellow River to their area and all the broken agreements which were involved in that accomplishment.” After waiting four days, the UNRRA observers were sent away without having visited the dikes (“Trip to Communist Dyke Area West Shantung,” May 27, 1947, GL5-1947-17, YRCCA).

CCP officials in the Bohai liberated area did permit Barnett to observe dike work and inundated villages during his visit there, but his findings confirmed that the local population no longer held UNRRA in high regard. People felt that the technical assistance provided by UNRRA had played a key role in the closure project, and that UNRRA should have stepped in to prevent the Nationalists from sealing the gap before dike repair and resettlement work had been completed. “Some few know of last minute efforts by UNRRA to detach itself from the Gap closure but they usually consider the moves nothing but gestures,” reported Barnett. He went on to explain that in Communist territory UNRRA was frequently confused with the American government, and that the menace posed by American-made planes only deepened people's conviction that the United States controlled UNRRA policy (Barnett c. Reference Barnett1947: 2–3). In sum, after the closing of the breach, prospects dimmed that UNRRA or joint participation in the Yellow River project could play a unifying role in an increasingly divided China.

Mobilizing the Masses, Fording the River: Postclosure Uses of the River

The Nationalist government overcame numerous technical and political hurdles to close the 5,000-foot-wide break at Huayuankou in precisely one year and 15 days.Footnote 15 The closure benefitted the large rural population of the inundated area, and though it unleashed misery upon several hundred riverine communities along the river's northern course, it did not result in the catastrophic loss of life predicted by the Communists. In the end, though, closing the breach was an engineering triumph but a political and military failure for the Nationalists. Diverting the river not only failed to weaken CCP armies in the north, but also affected the Yellow River Inundated Area in unintended ways. Communist guerilla groups were already active in eastern parts of the flooded zone before the breach closure, explains Muscolino, but floodwaters had provided a “natural boundary line” between Nationalist and Communist armies in the area. After rediverting the river north removed this water barrier, Communist forces could move more freely throughout what had been the inundated area, and began to expand their control there (Muscolino Reference Muscolino2015: 220–21). In addition, finds Barnett, while villagers in the former inundated area were aware of UNRRA's and CNRRA's role in closing the breach and reclaiming flooded land, “the UNRRA program seemed to have almost no effect in winning the people of the flooded area to loyalty to the Nationalist cause” (Barnett Reference Barnett1953: 70). In contrast, although the Communist campaign to postpone the closure and obtain more aid for the riverbed residents largely failed, the CCP proved quite adroit at transforming the threat posed by the returning Yellow River into an opportunity to discredit the Guomindang and its American supporters and mobilize and militarize the rural population along the river's northern course. Moreover, Communist mobilization efforts along the river laid a foundation for the pronounced emphasis on mass mobilization, self-reliance, local knowledge, and battling nature that would shape Mao-era water conservancy campaigns (Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 6, 138–39, Shapiro Reference Shapiro2001: 2–4, ch. 1).

Concerned that severe flooding would occur in the Ji-Lu-Yu and Bohai areas unless dike-repair work was finished before the summer high-water season, in the spring of 1947 Communist authorities in the Ji-Lu-Yu border area recruited more than 300,000 laborers to repair, raise, and strengthen dikes along the river, while another 100,000 workers were mobilized for the same purpose in the Bohai area (MHS 2009: 254). A local history account written by Guo Wenyuan, who took part in the dike-repair campaign in Puyang County,Footnote 16 demonstrates that Ji-Lu-Yu authorities depicted battling Nationalist troops and Yellow River floodwaters as part of the same larger struggle, and also called on people's basic desire for self-preservation. In late May 1946, recalls Guo, Ji-Lu-Yu administrative office director Duan Junyi called together county magistrates and river works personnel and urged them to mobilize people to “oppose Jiang [Chiang Kai-shek] and control the Yellow River,” and to “repair the dikes to rescue themselves” (Guo Reference Guo1996: 157).

Guo's account also shows Communist officials in the Ji-Lu-Yu area employing tactics that would later become hallmarks of Mao-era China (1949–76). Collecting the enormous amount of stone material required for dike-repair work proved a major challenge, recalled Guo, especially because people had not been able to bake new bricks during the war years. UNRRA had addressed the need for stone for the closure project by importing air compressors “worth about US$10,000 each” (the machines destroyed in the sabotage incident reported by Todd back in May 1946), and using them in tandem with jackhammers to expedite the production of rock (Todd to Zhou, May 26, 1946, GL5-1946-9, YRCCA; Todd Reference Todd1949: 48). In contrast, as would frequently be the case in the decades to follow, Communist authorities addressed a perceived need by mobilizing people through a mass campaign,Footnote 17 in this case a “contribute bricks and stones” campaign. “Donating one more brick or stone can save one more life and ensure that houses will not collapse after the Yellow River arrives,” people were told. Peasant associations played an important role in the mobilization, explains Guo. In 1947, landlord family homes still possessed many stone objects, such as tombstones, altar tables, and commemorative stelae. With an order from each peasant association, these items were commandeered for the dike-repair project, and landlords and other wealthy people dared not resist (Guo Reference Guo1996: 157–58). UNRRA personnel who traveled through the Ji-Lu-Yu area in May 1947 noted the effect of this campaign. “People were carting all available stone out of the villages toward the dyke,” they reported. “Stone monuments and ornamental arches were being dismantled and broken in pieces for dyke reinforcements” (“Trip to Communist Dyke Area West Shantung,” May 27, 1947, GL5-1947-17, YRCCA).

Mass mobilization also took place along the river in northeastern Shandong. As the summer flood season approached in 1947, on July 25 Bohai authorities issued a directive stating that all males between the ages of 16 and 55 who lived within five kilometers of the river should join a flood prevention team and take turns guarding the dikes. Authorities also made a point of drawing on local knowledge by soliciting suggestions from experienced river workers on how best to shore up the dikes (MHS 2009: 255–56). Barnett's trip through the Bohai area provides an outsider's view of Communist mobilization strategies there. “The dike repair is an all-out affair,” he wrote. “Everywhere I had the impression that dike repair was by far the most important concern,. . . second only to the war effort.” Dike workers received three catties of grain per day from the Bohai government. “Morale seems very high,” observed Barnett. “Competitive techniques are being used among the workers from different areas. Awards go to ‘labor heroes.’” Barnett also took note of how political education was employed by the Communists along the dikes. He witnessed “an organization of children who were entertaining dike workers with dancing and songs about the Yellow River and the Gap closure,” and saw government officials talking to groups of refugees about what had occurred at Huayuankou (Barnett, “Report,” May 29 to June 7, 1947, GL5-1947-17, YRCCA). Similar motivational tools, such as identifying model workers and using posters, slogans, songs, and speeches to increase efficiency, would also be employed by the Communists in flood-control campaigns after 1949 (Pietz Reference Pietz2015: 136–41). In short, along the Yellow River's northern course, Communist authorities transformed fear of the returning floodwaters into an opportunity to turn riverine communities against the Nationalists and UNRRA, while mobilizing them to repair dikes with the twin goal of saving their own homes and controlling the Yellow River.

In preparation for a Communist counteroffensive planned for the summer of 1947, authorities in the Ji-Yu-Lu area depicted the Yellow River not only as a danger to be controlled using large-scale dike-repair campaigns, but also as a formidable natural barrier that only the masses working together could cross. When the Nationalists moved most their elite forces east into Shandong and west into Shaanxi early in 1947 for their Strong Point Offensive, they left the “Central Plains” area along the lower reaches of the Yellow River in southern Shanxi, Henan, southern Hebei, and western Shandong relatively poorly defended. “Part of the reason for this weakness was the GMD's belief that the river itself was a sufficient obstacle,” explains Lew. After surviving the Strong Point Offensive, the Communist high command made the decision to cross the river into southwestern Shandong and Henan to attack the soft “underbelly” of Nationalist defenses (Lew Reference Lew2009: 56, 75–77; MHS 2009: 258; Westad Reference Westad2003: 168). In late April 1947, the Central Military Commission of the CCP ordered soldiers and civilians in the Ji-Lu-Yu area to prepare boats and ferry crossings so that the Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu Field Army commanded by Marshal Liu Bocheng and his chief political officer Deng Xiaoping could cross the Yellow River and launch an “all-out offensive” that would both reclaim territory lost in 1946 and penetrate “core areas of the Guomindang state” (Guo Reference Guo1986: 46; Westad Reference Westad2003: 168; Wou Reference Wou1994: 330–31).

Accounts compiled by participants in the river-crossing campaign and published by the Puyang literature and history materials (wenshi ziliao) officeFootnote 18 in the 1980s and 1990s detail the methods employed to mobilize local support for the crossing. Counties along the Yellow River were asked to establish eight ferry crossings along the 150-kilometer stretch of river that flowed from Puyang east through Puxian, Fanxian, Shouzhang, Zhangqiu, and Dong'e counties (see figure 1). Because the Yellow River had not flowed through the area for almost nine years, most of the boats used before the breach had been dismantled, so local carpenters and iron workers were recruited to build large boats that could ferry troops, artillery, and vehicles across the river. By the end of June some 140 boats had been completed (Guo Reference Guo1986: 47; MHS 2009: 259; see also Yang Reference Yang1998: 185). To prevent frequent Guomindang bombing raids from destroying the new boats, more than 5,000 local people were put to work digging waterways in wooded areas alongside the river where they could conceal boats and train sailors. Laborers also dug large holes in the cliffs along the waterways, and hid boats in the holes during the day (Ding Reference Ding1986: 55; Guo Reference Guo1986: 47).

In addition, approximately 2,000 young men from the Ji-Lu-Yu area were recruited to serve as sailors who would pilot the army across the river (MHS 2009: 259). Former sailors recall that volunteers received two sets of clothing and were provided with 2.5 jin Footnote 19 of millet per day (Huang and Wang Reference Huang and Zhengkui1986: 60). According to Yang Cuimin, who in 1947 served as the political commissar at the Linlou ferry crossing in Fanxian, the majority of the approximately 400 people who formed the Fanxian sailor's battalion “lacked experience piloting boats, and were not very familiar with the character of the Yellow River.” It was thus necessary to conduct two months of strict training that emphasized political education as well as military affairs and boat-piloting techniques. Recruits were first taught the “great significance” of the coming river crossing, which aimed to push forward the unification of the country by liberating regions under Nationalist control. Then during the technical training sessions, older boatmen shared their experiences on the Yellow River with the young recruits, and at night the trainees took turns conducting drills along the river under the cover of darkness (Ding Reference Ding1986: 55; Yang Reference Yang1998: 186).

Finally, when troops from the Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu Field Army began advancing into riverine counties in late June 1947, hundreds of local militiamen were recruited to survey the activities of the Nationalist troops on the south bank of the river to ensure that the final preparations for the crossing would not be disrupted (Belden Reference Belden1949: 357–59; Guo Reference Guo1986: 50). By the afternoon of June 30, all was in place. In Fanxian, the command center held an assembly to mobilize the sailors and soldiers, and as evening fell people took their places at the Linlou ferry and awaited the final order to begin the crossing (Yang Reference Yang1998: 187). That night, the 126,000-man Jin-Ji-Lu-Yu Field Army of Liu Bocheng and Deng Xiaoping began to cross the river in secret, taking Nationalist defenders along the southern bank by surprise. “Thanks to superior reconnaissance and the rapid river crossing,” writes Lew, Communist troops outflanked the Nationalist defense line, “which put them in prime position to destroy one unit after another with ease” (HSW 2004: 228; Lew Reference Lew2009: 77). “The natural barrier of the Yellow River was thus successfully broken,” concluded Yang. After the crossing was complete, senior officers in the Liu-Deng army wrote a letter commending the sailors and workers who had assisted in the crossing, and distributed one jin of pork to each of them in recognition of their hard work (Guo Reference Guo1986: 52; Yang Reference Yang1998: 188).