The last decade or so has seen a fundamental shift in Aboriginal cultural heritage law in Australia. A number of subnational jurisdictions in Australia have undergone major reforms to their Aboriginal heritage legislation. Other subnational jurisdictions are currently in the reform process or have promised reform in coming years. Some of the reform processes, such as those in New South Wales (NSW) and Western Australia, have been ongoing for many years and have often seen multiple draft reform proposals (often with significant time in-between proposals). These reforms have happened amid a complex and constantly evolving domestic political background. Australia thus becomes a site for reimagining cultural heritage law’s ability to grapple with the nuances of ever-changing culture and peoples’ relationships with it. These shifts are of special relevance in the Indigenous context because of the fraught relationships between settler states and Indigenous cultures, on the one hand, and the possibilities of using cultural heritage as a springboard for the recognition and safeguarding of identity and difference.

Part of this broader political context is the Indigenous-led proposals for constitutional reform. The Australian Constitution currently does not include Indigenous Australians in any way.Footnote 1 Within this constitutional reform debate has also been the strong call from Indigenous peoples for a treaty, given that Australia has never signed a treaty with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Some of the subnational jurisdictions, such as Victoria, have developed their own legislative treaties with the Indigenous peoples within their jurisdiction. Other jurisdictions have started processes of treaty negotiations, such as the Northern Territory. This context is highly relevant to Aboriginal heritage reforms, but the link between heritage reform and this background is not always recognized. The heritage law reform processes in Australia are, and have been, used by Indigenous communities as opportunities for Indigenous peoples to seek “recognition” and control of governance mechanisms that relate to their heritage. However, many of these aspirations may end up frustrated in the Eurocentric heritage law’s fraught relationship with its own politics.Footnote 2 Bureaucrats, politicians, Indigenous peoples, and their advocates end up enmeshed in battles about contested meanings, identities, visibility, and control. These actors make heritage law reform a microcosm of broader recognition, while, at the same time, focusing on the tensions that happen every day.

These everyday tensions involve high stakes. One contemporary NSW example relates to a coal mine in northwest NSW. This mine was approved by both the NSW and federal governments. The Aboriginal traditional owners of the area are currently challenging the decision of the federal environment minister that denies them protection of several areas of significant cultural heritage in the area of the mine.Footnote 3 As will be detailed below, an application to protect cultural heritage is generally only made to the relevant federal minister as a last resort after protection is first sought through the state government (in this case, NSW). The federal minister accepted that the coal mine would “destroy or desecrate” the specified cultural heritage and that “‘NSW laws were inadequate to protect” the cultural heritage.Footnote 4 However, she weighed the broader economic and social benefits of the mine and determined that they outweighed the destruction of the Aboriginal cultural heritage. The traditional owners are currently challenging the legality of this weighing-up exercise in a judicial review in the Federal Court. This example demonstrates not only the high stakes for Indigenous peoples where they face the destruction of their cultural heritage but also the contested and adversarial dynamics of settler state decision-making processes about heritage.

Australian jurisdictions are useful sites of legal analysis because the first iterations of Australian Aboriginal heritage legislation evolved prior to many of the contemporary international legal frameworks. In this sense, Australian jurisdictions that developed their own approaches in the 1970s are transitioning and adjusting within the contemporary international framework. We use the latest (and, at the time of writing, ongoing) process to reform Aboriginal heritage legislation in the state of NSW in order to explore some of the legal issues and themes emanating from the Australian experience. Currently, the relevant legislation “protecting” Aboriginal heritage in NSW is the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NPW Act).Footnote 5 Since 2011, the NSW government has been moving toward implementing standalone Aboriginal cultural heritage legislation. The process has involved a range of on-site consultations with Indigenous communities and the community at large as well as the possibility of organizations and individuals representing the community and different forms of expertise to make written submissions.

If the legislative effort in NSW succeeds, it seems that Indigenous peoples will have more control over their heritage in many respects. However, several background norms of “stage management” in this area, which apportion power through issues like the composition of advisory bodies, for instance, are still problematically undecided and leave much room to curtail the emancipatory potential of the new legislation, thus leading to power dilemmas with respect to heritage. Therefore, the NSW example is not only a useful case study in Australia or for other federal countries but also more broadly for thinking about how minority heritage regulation can serve broader social movements while simultaneously undercutting some of its own possibilities. We argue that even law that is ostensibly in place to promote the control of communities over their own heritage must perform difficult balancing acts that can default to path dependencies and effectively cause the law to detract from its own projected goals.

We note two important facts upfront. First, we are both non-Indigenous scholars, and there are several issues that are inappropriate for us to comment on. These issues are identified in this article when they arise. Second, we have contributed some of the ideas below in the form of a submission during the consultations for the current draft legislation in NSW.Footnote 6 As part of our submission writing process, one of us attended both an information session and a consultation workshop that were part of the wider consultation process undertaken by the NSW government. Both of these sessions were facilitated by a non-governmental facilitator who was engaged by the NSW government, and there were NSW government representatives present to answer questions.

The article proceeds in the following way. The next section introduces cultural heritage and federalism in Australia. We then move on to discuss Aboriginal heritage legislative reform efforts in Australia through the lens of NSW. Following this discussion, we move to the central part of this article, which focuses on NSW’s Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Bill 2018 (ACH Bill) and some of its promises and pitfalls to promote Indigenous control over heritage. There will then be some concluding remarks.Footnote 7

CULTURAL HERITAGE AND FEDERALISM IN AUSTRALIA

As indicated above, Australia is a federated system with a federal (or, as it is often referred to in Australia, a Commonwealth) government and state and territory jurisdictions. The two territory jurisdictions in Australia have less power than the six states. In Australia, the competence for heritage is shared between the federal and state or territory governments (hereafter referred simply as "states" for short), leading to some duplication in this area. The federal government draws its competence in some measure from the foreign affairs power, which states that the federal government may acquire legislative competence over subject matters reserved for states when the exercise of said powers relates to compliance with an international legal obligation. More specifically, since Commonwealth v. Tasmania (coincidentally, a case about an international cultural heritage treaty, the World Heritage Convention), it has been clear that any international treaty that the federal government enters into dislocates legislative competence from the constituent unit (CU) to the federal government.Footnote 8 The minority in this case posed an argument grounded on subsidiarity, indicating that the CU government would be best placed to make a decision on the measures of implementation. Nevertheless, the majority read the language of the World Heritage Convention as controlling, rather than managing, the heritage site based on other social and economic considerations.Footnote 9 Subsidiarity, therefore, was pushed aside in favor of a centralizing internationalist narrative around heritage, but it left the door open for states to introduce legislation on the day-to-day management of cultural heritage. This interpretation of foreign affairs power has made it one of the most important justifications for environmental federal legislation in Australia, for instance.Footnote 10

States, on the other hand, rely on “the legislative powers of the Parliament of each State [which] include full power to make laws for the peace, order and good government [POGG] of that State that have extra-territorial operation.”Footnote 11 The POGG power is deemed to be a “plenary power.”Footnote 12 In general, each level enjoys immunity in relation to the other.Footnote 13 However, in the event of simultaneous application of inconsistent laws between federal and state law in Australia, the former prevails, rendering state law invalid to the extent of the inconsistency.Footnote 14

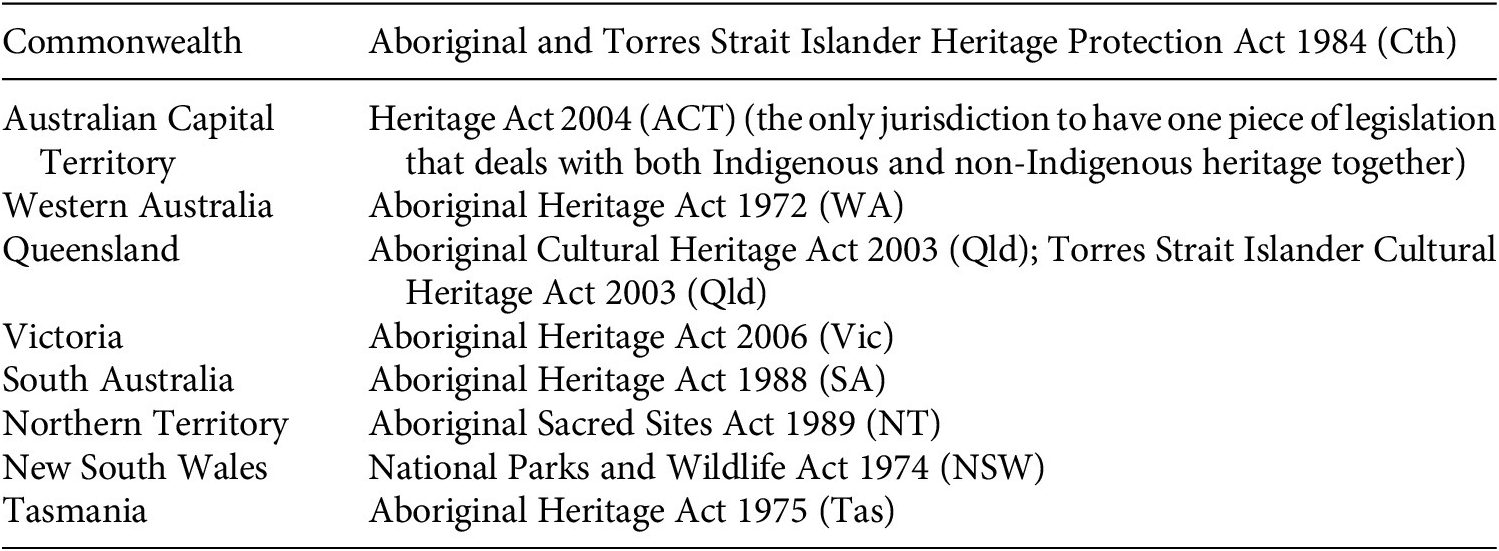

With respect to heritage, therefore, both the federal and state levels have competence to legislate in the area and, in fact, have done so in the past. The federal legislation, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984 (Cth), has been described by the then Justice Robert French (who went on to become the Chief Justice of Australia) as legislation that should be used “as a last resort” if protection under state or territory laws is inadequate.Footnote 15 The relevant legislation is set out in Table 1.

Table 1 Cultural heritage legislation in Australian jurisdictions

As noted above, only one jurisdiction in Australia has joint non-Indigenous and Indigenous heritage protection—the Australian Capital Territory—which is a very small jurisdiction. There is an important question to be asked whether treating Indigenous heritage separately from other types of heritage advances or hinders the political claims concerning the autonomy and self-determination of Indigenous peoples that the move ostensibly makes. For instance, Ana Vrdoljak recounts the process through which Indigenous art in Australia has been (re)classified as ethnographic art by some museums and as contemporary art by others.Footnote 16 On the one hand, to think of Indigenous art as ethnographic means acknowledging the special place of Indigenous culture; it also means othering that culture. On the other hand, to label Indigenous art as contemporary art enmeshes Indigenous identity into the fabric of the nation and puts it on par with other cultural expressions; it also dilutes the power of artistic expression as a focal point for political struggle.

From a pro-self-determination perspective, safeguarding Indigenous heritage through a separate legislative act underscores Indigenous peoples’ distinctive cultural identity and their separate existence from society at large. It also promotes mechanisms for control over heritage that are not normally sought after in the same way for heritage in non-minority contexts. Further, it is in line with the language of international instruments on Indigenous rights, such as the 2007 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)Footnote 17 and the 2016 American Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (ADRIP).Footnote 18

The UNDRIP contains two provisions on Indigenous heritage, which declare the right to practice and control heritage.Footnote 19 The ADRIP, by contrast, benefits from close to 10 years of use of the UNDRIP (not to mention that it did not have the African bloc’s last-minute push against self-determination) and therefore has somewhat more sophisticated provisions on these matters.Footnote 20 The key provisions on heritage are somewhat similar in tone to those in the UNDRIP.Footnote 21 A notable difference between the UNDRIP and the ADRIP is that the language in the latter, precisely benefiting from the activity under the former, is more assertive in some respects. In relation to heritage, the most notable difference is the ADRIP’s stronger emphasis on control over heritage as well as over reparations and restitution, which are more tentatively addressed in the UNDRIP. International instruments on Indigenous peoples’ rights, therefore, indirectly support the separation of Indigenous and non-Indigenous heritage by requiring the protection of Indigenous culture and offering important insights into the purposes of this split.

However, there is also something to be said about mainstreaming Indigenous heritage. The 2003 Convention for Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage (CSICH), for instance, rejects any reference to Indigenous heritage in its text (except for one short reference in the preamble) as a means of conveying the message that it is not only Indigenous peoples and other minorities that have this type of living heritage, which is traditionally referred to in Western law and legal systems as folklore or even “low culture.”Footnote 22 This traditional terminology evokes the problem with the separation: Indigenous peoples and other minorities are given culture at the expense of other forms of power, particularly political and economic (and they might also lose control of this culture through heritage legislation done wrong). By separating Indigenous and non-Indigenous heritage, a reified discourse about culture makes and authorizes a reality in which those with culture will always be subaltern, instead of conveying the message that everyone (Indigenous and non-Indigenous) has cultural heritage and that heritage safeguarding should not be seen as a concession to identity politics nor a limited pathway to power.

There are thus two competing views on legislative safeguarding of Indigenous heritage: merger and separation. A merger of Indigenous heritage legislation with other forms of heritage clearly signals that Indigenous and non-Indigenous culture are on the same footing and occupy the same place in society, but it can also code the “backgrounding” of Indigenous culture by not allowing it to receive the same level of attention as settler heritage or by enabling the merged legislation to be predominantly controlled by non-Indigenous peoples. Thus, while the merger of Indigenous and non-Indigenous heritage legislation can in theory articulate the power of heritage more clearly by aligning it with other forms of power more readily available to settler society, Indigenous heritage can still be bypassed by preferencing non-Indigenous heritage over Indigenous heritage in the implementation of the legislation.

The second strategy—the separation of Indigenous heritage legislation from other forms of heritage—underscores the distinctiveness of Indigenous identity. It provides a more focused understanding of Indigenous cultural heritage and a clearer opportunity for Indigenous power over, and involvement in, the legislative process. The possibilities of tapping into culture for the pursuit of a wide range of claims can also be made explicit in tailor-made legislation. At the same time, however, Indigenous culture can be ghettoized and separated from settler society, thereby also undermining the possibilities of leveraging heritage as a pathway to power. The question of whether to create separate legislation on Indigenous heritage or make it part of a more holistic approach to heritage safeguarding therefore echoes many of the tensions described by Vrdoljak as well as recounted above with respect to the status of Indigenous art in Australian public museums.Footnote 23 Therefore, either solution can increase or reduce the possibilities of Indigenous power via heritage.

In the case of the 2018 ACH Bill, as with almost every other jurisdiction in Australia, the separation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous heritage made its way into law. In NSW, this separation was done precisely as a measure of recognition, as the bill enunciates.Footnote 24 As suggested above, this separation might have unintended consequences for its purported political objectives in favor of Indigenous communities, but the current frameworks for non-Indigenous heritage in Australia are not suitable for the protection of Indigenous heritage.

ABORIGINAL HERITAGE LEGISLATIVE REFORM EFFORTS IN AUSTRALIA THROUGH THE LENS OF NSW

As identified above, the current provisions dealing with Aboriginal heritage in NSW are in the National Parks and Wildlife Act 1974 (NPW Act).Footnote 25 The NPW Act provides that the minister may declare a place to “be an Aboriginal place for the purposes of this Act” if the minister is of the opinion that it “is or was of special significance with respect to Aboriginal culture.”Footnote 26 However, rather than focus on what the minister is required to do to protect heritage, the NPW Act is based around the criminal offence of damaging Aboriginal heritage. There are then defenses and ways for persons and entities to guard against committing such an offence. This is a simplistic way of protecting heritage that does not involve any mandated Aboriginal involvement. Such an approach is not unique to NSW and is also the way that other pieces of “older” Indigenous heritage legislation have operated, and continue to operate, in jurisdictions such as Western Australia.Footnote 27

In the NPW Act, there is an offence of “harming or desecrating Aboriginal objects and Aboriginal places.”Footnote 28 This offence is categorized into three types:

1. A person must not harm or desecrate an object that the person knows is an Aboriginal object.Footnote 29

2. A person must not harm an Aboriginal object.Footnote 30

3. A person must not harm or desecrate an Aboriginal place.Footnote 31

The second two offences are offences of strict liability (there is no need to prove that the perpetrator knowingly harmed the object/place), but the defense of honest and reasonable mistake of fact applies.Footnote 32 It is also a defense to the second offence if the defendant “reasonably determined that no Aboriginal object would be harmed.”Footnote 33

It is a defense to prosecution for all three offences if the harm or desecration concerned was authorized by an Aboriginal heritage impact permit (AHIP), and the conditions to which that AHIP was subject were not contravened.Footnote 34 Therefore, a development proponent that was potentially going to damage Aboriginal heritage would apply for an AHIP. An AHIP can be issued in relation to “a specified Aboriginal object, Aboriginal place, land, activity or person or specified types or classes of Aboriginal objects, Aboriginal places, land, activities or persons.”Footnote 35 The chief executive of the NSW’s Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) makes the decision on whether to grant or refuse an AHIP and whether there should be any conditions placed on the AHIP.Footnote 36 Part of the application process for the AHIP outlined in the National Parks and Wildlife Regulation 2009 (NPW Regulations) requires “Aboriginal community consultation.”Footnote 37 Relevant Aboriginal “parties” are given 28 days to respond to a draft cultural heritage assessment report provided by the development proponent.Footnote 38 These reports can be lengthy and technical, and the relevant Aboriginal parties may be responding to these assessments in their own time (that is, they may not be employed or paid to review the documents). Further, even if these consultation requirements are not met, the NPW Regulations state that an AHIP application is not invalid solely for that reason.Footnote 39 There is an appeal process through which an applicant for an AHIP can appeal the decision of the chief executive to the NSW Land and Environment Court.Footnote 40 This is a form of merits review where there is a total rehearing of the issue and where the judge has to determine if the “correct and preferable decision” was made. There is no equivalent provision for Indigenous peoples that are impacted by an AHIP. Therefore, the only option for Indigenous peoples would be to challenge it through judicial review, which requires an error of law. An error of law is a much higher bar than appealing on the basis that it was not the “correct and preferable decision.”

The chief executive also keeps a database known as the Aboriginal Heritage Information Management System (AHIMS). The AHIMS contains information that has been provided to the chief executive about Aboriginal objects and other objects, places, and features of significance to Aboriginal people.Footnote 41 However, by the government’s own admission, “[the] AHIMS is not designed for detailed monitoring, evaluation and reporting and is centrally administered, limiting opportunities for local participation in information management.”Footnote 42

The contemporary reform process in NSW started in 2011 when the NSW government announced a broad legislative review in relation to Aboriginal heritage. The initial public consultation consisted of two phases, and the NSW government published an initial discussion paper to stimulate discussion and summarize feedback. In 2011, the NSW government established an independent body called the Aboriginal Culture and Heritage Reform Working Party (Working Party). In December 2012, the Working Party published a report entitled “Reforming the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage System in NSW: Draft Recommendations to the NSW Government,”Footnote 43 in which 23 individual recommendations were made relating to six “key themes”: stand-alone legislation; administrative structures; early planning process; local decisions by local people; streamlined processes; and funding Aboriginal cultural heritage outcomes.Footnote 44

In response to the Working Party’s recommendations, the NSW government published a report outlining reasons for reform and the key elements of a proposed reform model.Footnote 45 This report was the basis of another phase of public consultation. A NSW government document summarizing this next phase of feedback states that “[o]verall the … feedback indicated strong support for stand-alone legislation as well as the intent to ensure ACH values are considered earlier in the development assessment process and proactively for conservation” and also identifies some areas where feedback was varied or critical.Footnote 46 According to the website of the OEH, “feedback showed there was general support for the principles of the proposed model, but wide-ranging and often contrasting views on detailed design elements.”Footnote 47

There is little information about what happened in the intervening period from 2014 to mid-2017. The OEH website states that the “[g]overnment considered the wide-ranging feedback received and best practice in other jurisdictions to revise the 2013 model and prepare draft legislation for further consideration.”Footnote 48 Some parts of the OEH website describe the current reform proposal as a continuation of the previous reform attempt.Footnote 49 Elsewhere, however, the OEH frames the current reform process as a “new” system with two new stages of public consultation.Footnote 50 On 11 September 2017, the NSW government released a proposed new legal framework for Aboriginal cultural heritage, known as the Consultation Document, alongside associated documents.Footnote 51 The new framework is based, in particular, on the recommendations of the Working Party and public feedback received on the 2013 reform model. It has five key aims that are detailed in the next section. Following the release of the proposed new legal framework, on 23 February 2018, the OEH released the 2018 draft ACH Bill. The ACH Bill is a draft of a bill that will be debated in Parliament before being passed as legislation. Not all bills have a draft publicly provided, but this practice is used in Australia to seek public comment before finalizing the terms of a bill. The next section engages with the ACH Bill in order to discuss some of these possibilities in the ACH Bill’s own terms.

DISSECTING THE 2018 ACH BILL: PROMISES AND PITFALLS

The draft ACH Bill would create a standalone piece of legislation relating to Aboriginal heritage. Although it is standalone and would be a new piece of legislation, the areas for proposed reform can be seen, and have been viewed by the NSW government, as relating back to the NPW Act’s provisions. Five broad areas for reform have been suggested by the NSW government: a broader definition of Aboriginal heritage, a process that includes and emphasizes decision making by Aboriginal people, better management of information about heritage, improved “protection, management and conservation” of Aboriginal heritage, and “greater confidence” in the general regulatory system.Footnote 52 Beyond these identified areas, these reforms are a move away from a regime built around a criminal offence provision toward a framework that is focused on knowledge sharing, planning, agreement making (between proponents of actions affecting heritage and Aboriginal peoples), and entrenched Aboriginal involvement in decision making. Of course, the criminal offence provisions still exist in the ACH Bill and have an important role to play, but they are no longer bluntly at the center of the legislation. There is much to critique about the ACH Bill, but this overall shift in focus should be applauded.

At the time of writing, the ACH Bill is still a draft and, therefore, a “work-in-progress” that is being actively discussed around NSW. Among the many issues that arise from the bill, we have chosen to highlight the following: (1) the definition of heritage in the bill; (2) the bill’s objectives and, particularly, the tension between control over, and visibility of, heritage; (3) matters of agency (that is, who gets to speak on behalf of heritage) and, relatedly, background norms affecting the possible modalities of the exercise of Indigenous agency (seen through the perspective of actions affecting Indigenous heritage in relation to interests of other segments of society, particularly the banner of “development projects”); and (4) regulatory challenges related particularly to enduring governmental authority over Indigenous heritage. Each of these issues says something about how power is narrated and contested with respect to Indigenous heritage.

Short of a Holistic Definition of Heritage

There was no formal definition of Aboriginal heritage in the NPW Act but, rather, a definition of Aboriginal object and, as seen above, a vague definition of “Aboriginal place” that was focused on the minister’s opinion. The new definition of “Aboriginal cultural heritage” is broad and includes explicit recognition that heritage is living:

Aboriginal cultural heritage is the living, traditional and historical practices, representations, expressions, beliefs, knowledge and skills (together with the associated environment, landscapes, places, objects, ancestral remains and materials) that Aboriginal people recognize as part of their cultural heritage and identity.Footnote 53

There are also additional definitions for Aboriginal objects, ancestral remains, Aboriginal cultural heritage significance, and intangible cultural heritage.Footnote 54

Protection of intangible cultural heritage is a new aspect of the draft ACH Bill. In this respect, NSW is following the Australian state of Victoria. In 2016, Victoria became the first Australian jurisdiction to introduce provisions around intangible cultural heritage.Footnote 55 More broadly, Victoria is currently regarded as the leading Australian jurisdiction in relation to Aboriginal cultural heritage. In the ACH Bill, intangible cultural heritage is defined as follows:

Intangible Aboriginal cultural heritagemeans any practices, representations, expressions, beliefs, knowledge or skills comprising Aboriginal cultural heritage (including intellectual creation or innovation of Aboriginal people based on or derived from Aboriginal cultural heritage), but does not include Aboriginal objects, Aboriginal ancestral remains or any other tangible materials comprising Aboriginal cultural heritage.Footnote 56

The definition of “Aboriginal cultural heritage” appears to draw from best international practice and holistically integrates different aspects of cultural heritage, acknowledging its role as the living culture of Indigenous peoples. It also includes the identification by Indigenous communities of their own cultural heritage as a key element in the definition. But two major concerns arise with the definitions, both as a matter of legal analysis and from the perspective of those who are to be impacted by the legislation. First, and specifically, it is not clear whether the definition of Aboriginal cultural heritage includes waters and coastal waters. Second, and more broadly, “intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage” seems to fall short of being holistically integrated with “Aboriginal cultural heritage.”

On the first point, it is not clear whether the definition of Aboriginal cultural heritage extends to waters and coastal waters. Section 4(1) defines Aboriginal cultural heritage as “the living, traditional and historical practices, representations, expressions, beliefs, knowledge and skills (together with their associated environment, landscapes, places, objects, ancestral remains and materials) that Aboriginal people recognise as part of their cultural heritage and identity.” The terms “environment,” “landscape,” and “place” are not further defined. The term “land” is defined in section 5(1) as including “any place”; however, “place” is not defined. While it seems that the definition in section 4(1) is attempting to be inclusive, it does not make clear that it applies to both waters and coastal waters. This clarification would be in keeping with the NSW ConstitutionFootnote 57 as well as other practice on Indigenous heritage in Australia.Footnote 58

On the matter of intangible cultural heritage, the bill defines intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage as “any practices, representations, expressions, beliefs, knowledge or skills comprising Aboriginal cultural heritage (including intellectual creation or innovation of Aboriginal people based on or derived from Aboriginal cultural heritage), but does not include Aboriginal objects, Aboriginal ancestral remains or any other tangible materials comprising Aboriginal cultural heritage.”Footnote 59 The definition of intangible cultural heritage in the draft ACH Bill seems to cut across the holistic definition of Aboriginal cultural heritage in section 4(1). Section 4(2) imposes a separation between “general” Aboriginal cultural heritage and intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage that is not supported by the experience of intangible heritage as living culture. It also seems like this was not the intent of the legislative scheme, given the definition in section 4(1) and the fact that tools such as the conservation agreements seem to apply across tangible and intangible heritage.

Further, the definition of intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage in the bill is at odds with best international practice. The CSICH, which has been ratified by over 175 countries around the world and considered by Victoria in the reform of its legislation,Footnote 60 is clear in connecting intangible heritage to the tangible materials associated with the cultural practice. To separate intangible heritage from its associated tangible materials and elements forces a separation between tangible and intangible heritage that yields to the connection between intellectual property and intangible cultural heritage. However, intellectual property concepts only capture part of what intangible heritage is and focus on a product rather than on the cultural processes that make up intangible cultural heritage.Footnote 61 The processes need the material support, and, by implying otherwise, the legislation prevents the holistic comprehension of Indigenous heritage and its uses, in favor of legal categories that are themselves exogenous to many Indigenous peoples. The bill therefore falls short in its definitions, with the consequence that power over certain heritage is elusive or is muddied by an unclear relationship between tangible and intangible heritage. The same uneasy relationship is seen with respect to the bill’s objectives.

Conflicting Objectives: Control versus Visibility

Section 3 (a) contains the objects of the draft ACH Bill, which are predicated on the recognition of Aboriginal people and “establishing a legislative framework that reflects Aboriginal people’s responsibility for and authority over Aboriginal cultural heritage.” Yet the best international practice on intangible cultural heritage under the CSICH focuses on visibility and awareness raising as key elements to promote understanding and respect for intangible heritage and the communities to which this heritage belongs. These two objectives may lead to tension. Regarding public awareness raising, the key issue is the balance of competing objectives. Specifically, a key objective of the bill is to tie recognition to the control by Aboriginal people of their own heritageFootnote 62 as well as to the status of Aboriginal heritage as living culture.Footnote 63 However, in the implementation of this idea of control over heritage, the awareness-raising objective may be ultimately frustrated.

Part of the reason for this uneasy and somewhat contradictory position vis-à-vis visibility has to do with what visibility as an imperative coming from an international treaty may mean for Indigenous peoples themselves. As is widely known, international law has not always favored Indigenous peoples (even if, conversely, it has been positive in other ways).Footnote 64 Some Indigenous peoples may agree with (and desire) visibility, but this value is less relevant for other peoples. It is acceptable for Indigenous peoples to push against the idea of visibility, especially if it is seen as requiring Indigenous communities to render their culture visible to outsiders that, historically and currently, have been exploitative in their interaction with Indigenous culture. In other words, there is a line of argument that Indigenous communities do not owe anything to the state or non-Indigenous peoples and that they should not be responsible for showcasing their culture as a strategy for “reconciling.” In the words of one Indigenous voice,

[y]ou seek to say that because you are Australians you have a right to study and explore our heritage because it is a heritage to be shared by all Australians, white and black. From our point of view we say you have come as invaders, you have tried to destroy our culture, you have built your fortunes upon the lands and bodies of our people and now, having said sorry, want a share in picking out the bones of what you regard as a dead past. We say that it is our past, our culture and heritage, and forms part of our present life. As such it is ours to control and it is ours to share on our terms.Footnote 65

Therefore, visibility might be something the challenge of which actually aligns with Indigenous peoples’ views, even if it goes against the CSICH.

Awareness-raising and visibility as a safeguarding strategy can also have an impact on what type of cultural heritage is safeguarded as it may be skewed toward heritage that can be “understood” from a non-Indigenous perspective (which is often skewed toward tangible heritage). The objectives of the proposed bill are both protection in favor of communities and knowledge and respect. In its current format, though, one of the consequences is that the former is accomplished at the expense of the latter, whereas there are ways of better reconciling these objectives. In this respect, the objective of promoting understanding of, and respect for, Aboriginal heritage is in line with international practice. Yet international best practice is mindful of the need for Indigenous community control over heritage and intangible heritage in particular.Footnote 66 It also acknowledges that issues of cultural privacy may require that certain aspects of heritage be kept secret,Footnote 67 and tightly controlled, especially through intellectual property or intellectual property-like mechanisms.Footnote 68

However, tight control and cultural privacy are not the default positions in the best international practice, whereas they are the default position in the bill with respect to intangible cultural heritage. Rather, the international emphasis is on control and enhancing visibility of intangible heritage whenever possible and in accordance with community aspirations. The rationale is that intangible heritage will be better safeguarded if people can appreciate it, and this is done through promoting understanding and respect, as the bill aims to do. But the current division of the bill (Part 4, Division 3) on intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage frustrates this objective.

More specifically, the draft ACH Bill states that intangible cultural heritage can “only” be registered if “it is not widely known to the public.” This approach borrows from intellectual property law ideas of novelty or originalityFootnote 69 and, to a large extent, replicates the approach in the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Act 2016.Footnote 70 However, while intellectual property or intellectual property-like mechanisms can be an important part of the equation to safeguard intangible cultural heritage, they also miss the point.Footnote 71 Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage can be done successfully via control that is not based on secrecy around practices at all times. Whenever necessary, cultural privacy should be available to registered holders, but this should not be the default position.

A question remains as to whether a person already using intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage that is subsequently registered will commit an offence. That is in fact a concern, but it should not detract from the objective of raising awareness about Aboriginal heritage. As it stands, the bill in fact may be read as suggesting that intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage already widely known has flowed into the public domain and is no longer able to be protected. A registration requirement with a savings clause for third-party use prior to registration can still have the effect of claiming intangible heritage as Aboriginal, but protecting those who already use elements of Aboriginal heritage, should that be the desired intent. This clause should allow registration while excluding criminal liability but still requiring changes to current use should it be culturally inappropriate in the eyes of the community of origin.

One of the important aspects of a framework that is focused on awareness raising as well as planning and agreement making is the availability of accurate information. However, the availability of information is problematic where some information is culturally sensitive and should not be in the public domain or where community members are reluctant to put it in the public realm because they fear the implications, such as damage from tourists.Footnote 72 The draft ACH Bill seeks to establish a system that contains information in relation to Aboriginal cultural heritage (the “ACH Information System”). This new system would comprise a restricted access database for information that is not appropriate for the public domain as well as a public online portal for unrestricted information.Footnote 73 The ACH Information System would also include the documents that the Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Authority (ACH Authority) is responsible for developing: management plans, cultural heritage maps, strategic plans, and local cultural heritage maps as well as any places declared by the minister to be Aboriginal cultural heritage.Footnote 74

Who Speaks for Heritage?

The draft ACH Bill proposes the establishment of the ACH Authority. This body will take over the types of functions that were previously vested in the chief executive pursuant to the NPW Act but with a much broader remit. The ACH Authority will not be subject to the control of a minister and will be a NSW government agency.Footnote 75 However, as we will discuss below, the minister retains some decision-making authority. All members of the Board of the ACH Authority will be Aboriginal.Footnote 76 The method for choosing who will be the members of the ACH Authority has not been articulated in the ACH Bill. There is a “consultation note” in the ACH Bill that states:

The process for the nomination of Aboriginal persons as members of the Board, and their required collective skills and expertise, has not yet been determined and included in the draft Bill, but is intended to be a community-driven process to ensure the Board has cultural legitimacy and the requisite skills and expertise.Footnote 77

Two points should be made about this note. First, it is vital that the process is driven by the community. Second, as we are two non-Indigenous scholars, it is inappropriate for us to make any comment on what this community-driven process should look like. However, from a legal standpoint, there are inherent dangers in leaving such a crucial issue to be determined later. Certainly, these mechanics are going to take several years to determine and will take even longer to come into operation. We will return to this issue below.

The ACH Authority is the body that underpins the draft ACH Bill. The ACH Authority will make recommendations to the minister on the declaration of Aboriginal cultural heritage, register intangible heritage, prepare Aboriginal cultural heritage maps, approve cultural heritage management plans, care for Aboriginal objects or ancestral remains vested in the ACH Authority, and manage a funding allocation.Footnote 78 As part of undertaking of these functions, the ACH Authority will establish several Local Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Consultation Panels (Local ACH Consultation Panels) to engage with, and represent, the local Aboriginal communities.Footnote 79 These Local ACH Consultation Panels will “represent Aboriginal cultural heritage authority” in relation to the area or aspect of heritage for which they are established and will provide advice to the ACH Authority in relation to this heritage.Footnote 80

A community-driven process is required on the formation of the ACH Authority and the Local ACH Consultation Panels. These bodies underpin the draft ACH Bill so Aboriginal views must take precedence in the consultations about their formation. The ACH Authority is the body that underpins the draft ACH Bill, and the legislative scheme cannot operate until the ACH Authority is formed. Yet all of the detail as to its composition has been left until after the ACH Bill has passed. There are dangers of leaving such a crucial issue to be determined later. Other than goodwill and political accountability, there is nothing holding governments of the future accountable to complete this process. There are questions about deferring the power allocation on the composition of such a central organ, which not only speaks directly to the issue of stage management by non-Indigenous people (discussed below) but also has the potential to compromise those individuals who speak on behalf of Aboriginal heritage. In relation to the provisions of Schedule 1 (members and procedure of the board and of the ACH Authority), it is also stated that the minister can “remove a member from office at any time,” with what appears to be excessive or even absolute discretion.Footnote 81 If the minister is going to have such a power, there should be input from other members of the ACH Authority and defined considerations that the minister must consider. In this way, the power can be better distributed between Indigenous and non-Indigenous parties, with the prevalence of Indigenous authority.

One of the draft ACH Bill’s objectives is to instill “greater confidence” in the general regulatory system around Indigenous heritage.Footnote 82 This area of the proposed reform is the most complex as it deals with assessments of projects that may damage Aboriginal heritage. Further, it reaches into other areas of regulation such as land-use planning, development assessment, and land management. Project proponents will be required to apply for an ACH management plan.Footnote 83 The application for a management plan includes a process of assessment and negotiation. The assessment process involves four stages: viewing ACH maps to determine risk of damage to heritage; a preliminary investigation that includes meeting the Local ACH Consultation Panel; a scoping assessment to share information and understanding with the Local ACH Consultation Panel; and, finally, the production of an assessment report that enables negotiation and decision making.Footnote 84 The management plan is then to be negotiated by the proponent and the relevant Local ACH Consultation Panel.Footnote 85 The ACH Authority then approves, refuses, or refers back for a redraft the management plan.Footnote 86 There is a merits review appeal mechanism for the proponent against the ACH Authority’s decision.Footnote 87 There is no appeal mechanism for the Local ACH Consultation Panel, which seems to be based on an assumption that the ACH Authority will follow the recommendation of the Local ACH Consultation Panel.

While criticisms can be made of this process, it can be commended for being focused on negotiation, local engagement, and conservation rather than for just regulating the allowance of harm. The management plan will also be integrated into other development assessments and will be required to lodge development applications (whereas, currently, AHIPs are only required after a proponent has obtained a development approval). These are all worthwhile aspirations, the key challenge being who makes the decisions about how and when these processes are undertaken. In the absence of clear Indigenous participation in deciding the rules of the game, there is a significant risk that these processes will be biased (however unintendedly) toward non-Indigenous objectives.

One key example of the crucial role of Indigenous participation in the development context is heritage impact assessments. Part 5, Divisions 3 and 4, of the draft ACH Bill refer to the importance of impact assessment with respect to Aboriginal cultural heritage. The inclusion of negotiation as a key element in this area is important,Footnote 88 but the bill leaves much of this process to a code of practice that is yet to be developed.Footnote 89 What follows acknowledges the principles enshrined in Part 5, Division 4, while pointing to international best practice that may be useful in the area, which holds community participation to be key in these processes. Crucially, Part 5, Division 4, seems to largely exclude Aboriginal intangible cultural heritage from the process, whereas intangible heritage would also benefit from this form of impact assessment.

An important example of best international practice in this area derives from the 2004 Akwé: Kon Guidelines on Impact Assessment (Akwé: Kon Guidelines).Footnote 90 These guidelines were enacted bearing Article 8(j) of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), to which Australia is a party,Footnote 91 in mind. Article 8(j) is the core provision relating to traditional knowledge, and the CBD provides a framework that ensures the full involvement of Indigenous and local communities in assessing the cultural, environmental, and social impact of proposed developments on the interests and concerns of traditional communities. It considers traditional practices and knowledge to be part of the impact assessment process.Footnote 92 The idea of promoting cultural impact assessments predates these guidelines and is in line with experiences in the United States, for instance.Footnote 93

Cultural impact assessment is defined in the Akwé: Kon Guidelines as a process of evaluating the likely impacts of a proposed development on the way of life of a particular group or community, with the full involvement of this group or community of people and possibly undertaken by this group or community of people. A cultural impact assessment will generally address the impacts, both beneficial and adverse, of a proposed development that may affect, for example, the values, belief systems, customary laws, language(s), customs, economy, relationships with the local environment and particular species, social organization and traditions of the affected community.Footnote 94 The guidelines also offer a definition of a “cultural heritage impact assessment,” which is “a process of evaluating the likely impacts, both beneficial and adverse, of a proposed development on the physical manifestations of a community’s cultural heritage including sites, structures and remains of archaeological, architectural, historical, religious, spiritual, cultural, ecological or aesthetical value or significance.”Footnote 95 This definition refers primarily to built heritage, but it also takes into account the intangible values associated with it.

The Akwé: Kon Guidelines state that a single assessment process should integrate cultural, environmental, and social issues.Footnote 96 They also outline steps that should be considered when the developed project takes place on lands or sites that are sacred to, or traditionally occupied by, Indigenous or local communities. These steps include the identification of all relevant stakeholders likely to be affected by the project; the establishment of effective consulting mechanisms that include all segments of a community, including women, youth, the elderly, and other vulnerable groups; and a process of recording the views expressed by members of the community. The guidelines also determine that the community should have veto power over a project that can impact the community and that sufficient human, financial, technical, and legal resources should be given to communities in order to ensure the effectiveness of their participation in all phases of the impact assessment process. Actors should also be identified who would be responsible for liability, redress, insurance, and compensation, and measures must be identified to prevent or mitigate negative impacts.Footnote 97

However, the Akwé: Kon Guidelines are not without their problems. At least inasmuch as they concern community participation, the guidelines tend to individualize community members as opposed to referring to the community as a whole. This individualization implies a disbelief in traditional Indigenous agency, in which one single individual or select group of individuals speaks on behalf of the community and advances a more inclusive model, but one that may come into conflict with perceived notions of group identity and group rights in traditional communities, while, at the same time, advancing individualism. When it comes to the identification of stakeholders, for instance, the guidelines suggest that a formal process should be undertaken to identify all of the community members and that a committee representative of all the segments of the community then be established to advise on the impact assessment process.Footnote 98

Specifically regarding cultural impact assessments, the Akwé: Kon Guidelines indicate several factors to be considered, including impacts on the customary use of resources; impacts on traditional knowledge; impacts on sacred sites and the associated ceremonial or ritual activities; concerns for cultural privacy (especially regarding the disclosure of sacred or secret knowledge, which then includes protection measures and prior informed consent); impacts on customary laws (which may include the need to codify customary law, clarify matters of jurisdiction, and “negotiate ways to minimize breaches of local laws”); and protocols to be established between the communities and the parties undertaking the developing project to facilitate the conduct of the development project and of the personnel associated with it.Footnote 99 The section of the guidelines on “general considerations” also highlights some elements more closely related to the cultural dimension of the process and even to intangible heritage concerns, such as the assessment of the impact over ownership, protection, and control of traditional knowledge and the need for prior and informed consent.Footnote 100 This instance of best international practice, therefore, suggests that the draft ACH Bill would benefit from clearer provisions on the need and importance of the role of local communities as well as clearer provisions on benefit sharing with respect to cultural and cultural heritage impact assessments connected to any development project, whether it affects tangible or intangible heritage.

Regulatory Challenges

There are several new “tools” that the draft ACH Bill proposes, including declarations and agreements. One criticism is that the relationship between all of these tools is not clear in the current draft bill. To protect particular places, objects, or intangible heritage, the ACH Bill has declarations of Aboriginal cultural heritage, Aboriginal cultural heritage conservation agreements, and intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage agreements. A declaration is similar to the documents that existed under the NPW Act, including final ministerial decision making, but it has a broader definition of Aboriginal cultural heritage attached to it now.Footnote 101 Conservation agreements are voluntary agreements that will be between a landowner and the ACH Authority and can relate to either, or both, tangible and intangible cultural heritage.Footnote 102 Intangible Aboriginal cultural heritage agreements are aimed at protecting intangible Indigenous heritage from being used inappropriately for commercial purposes.Footnote 103 These agreements will be entered into between the ACH Authority and groups of Indigenous peoples (such as a Local ACH Consultation Panel, a registered Native title body corporate, or a local Aboriginal Land Council).Footnote 104

The minister’s powers with respect to declarations of Aboriginal cultural heritage pursuant to section 18 are unclear. It appears that the minister currently has excessive discretion as to the relevant considerations and timing of his or her decision. Pursuant to section 18(1), the “Minister may, on the recommendation of the ACH Authority, declare an area to be Aboriginal heritage” (emphasis added). Section 18(4) also requires the minister to consult the Local ACH Consultation Panel, the landholders, any public or local authority, and the owners of the object or material. However, there is no further guidance on what the minister needs to consider. Therefore, the minister has absolute discretion. Further, this power effectively includes the ability to declare that certain activities can be carried out despite a declaration and are therefore exempt from the harm offence provisions.Footnote 105

Instead, the ACH Authority should have the power to make declarations and determine whether any activities can be carried out despite the declaration. Giving the minister, who may be non-Indigenous, the final decision-making power over declarations directly counters the aspirations of the Consultation DocumentFootnote 106 as well as of the draft ACH Bill in relation to Aboriginal decision-making. However, if the minister is to retain this power, then a set of relevant considerations, at a minimum, is required and would be beneficial to all parties involved, including the ACH Authority. The Consultation Document preceding the ACH Bill stated that the “draft Bill will create more transparency around the matters that are to be considered by the Authority in recommending a nomination for the Minister.”Footnote 107 However, the bill does not contain this information. A nomination process needs to be set out in the bill, and a form of interim protection needs to be put in place while a declaration nomination is being processed. Finally, in allocating power in this area in favor of Indigenous peoples, provision must be made for a merits appeal in the Land and Environment Court by the ACH Authority (if the minister retains the power) and by Aboriginal peoples and groups more generally against a decision pursuant to section 18.

In connection to these regulatory challenges and the tools to safeguard Aboriginal cultural heritage, it is not clear from the draft ACH Bill what the purpose and consequence of a declaration of Aboriginal cultural heritage in section 18 means. Given the way in which the bill is currently formulated, declared cultural heritage should appear on Aboriginal cultural heritage maps, any activity that impacts declared cultural heritage should require an ACH management plan (as is suggested in the Consultation Document),Footnote 108 and any harm offences would apply. However, none of this is set out in the bill, muddying its power dynamics.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Indigenous cultural heritage law is at the intersection of multiple struggles in countries like Australia. And while its contemporary ostensible objective is clear (power goes to Indigenous peoples), the tools used to pursue this objective are unclear. There is a lingering question as to how the rules for the establishment and deployment of this power are set out and what they mean for its actual exercise. As the NSW Bill example shows, good intentions and rhetoric are not always enough, and one must stay vigilant in observing the design and deployment of background “stage management” rules. Reliance on political and bureaucratic discretion may seem like a good way of introducing flexibility in a policy area as mutable as culture and heritage, but it can also displace Indigenous voices. Only by clarifying stage management rules can the power of heritage and heritage law in promoting political goals that favor Indigenous peoples be truly deployed.

Our analysis of the NSW reform process shows that power is contested and negotiated in multiple and complex ways. The key dilemma of power in the cultural heritage law context is where it lies, followed closely with what the power is to be used for. Domestic cultural heritage law with respect to Indigenous and other minority groups is a double-edged sword: done right, it can promote Indigenous control over heritage as a platform for broader governance opportunities, but, done poorly, it can separate Indigenous or minority heritage from other forms of heritage, which may lead to unintended consequences due to the lack of comparative legal protection between the two. For us, as authors who joined together to share our expertise in domestic and international heritage respectively, the aspect of NSW’s reform process (and the broader Australian context) that is most complex is the relationship between the formula set out in Article 1 of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s Constitution of promoting reconciliation through awareness-raising and cultural exchange and the contested context of contemporary Aboriginal heritage protection in the settler state. This is fertile ground for further research since nuanced thinking is needed about future possibilities.