Introduction

In this paper, I look at the intersections between ageing and retirement migration from the post-Soviet Baltic country of Latvia, situating my analysis within the wider context of other diverse post-socialist older-age migration settings. A strategy of active ageing (Walker, Reference Walker2002) is nowadays seen as a policy solution to the unprecedented demographic challenges of an ageing population in Europe and beyond. As a result, active ageing has recently gained traction amongst gerontologists and other social scientists who study ageing populations (Walker and Maltby, Reference Walker and Maltby2012; Boudiny, Reference Boudiny2013). I propose to broaden the conceptual take on emigration from post-Soviet Latvia as a relevant example of active ageing and ‘reversing retirement frontiers’. Older migrants push forward the temporal retirement frontier and continue working as long as they can. At the same time, older people also push the retirement frontier geographically outward, through emigration. Moreover, due to movements back and forth, older migrants are engaging in, and are subject to, transnational social protection processes. In these multiple ways, the retirement frontier becomes more porous.

In terms of ageing, the 21st century is defined by significant demographic changes. The world's population is increasingly ageing (Skinner et al., Reference Skinner, Andrews, Cutchin, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018: 9), and the trends are particularly stark in the post-Soviet countries and in other countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Geographic differences are crucial in demographic ageing. According to United Nations forecasts, in 2050 around 80 per cent of ageing people will live in low- and medium-income countries in the Global South (Rishworth and Elliott, Reference Rishworth, Elliott, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2018: 110–111). While there is an increasing awareness of the key role of ageing in population structural change worldwide, post-Soviet legacies and (im)mobilities remain under-theorised and empirically under-explored.

Hence, the main research question addressed by this paper, taking the Latvian case as an exemplar, is:

• How do people envisage, practise and narrate pre-retirement or retirement migration?

Moreover, since the empirical data show that ageing people often work in precarious jobs abroad (Lulle and King, Reference Lulle and King2016), I focus also on what keeps people continuing to go abroad despite restrictions on the types of work they can achieve.

The paper proceeds as follows. Firstly, I will analyse the context which has ‘reversed’ the retirement frontier in post-socialist spaces, compared to Western countries. This is important for developing a theoretical framework on how new retirement migration frontiers emerge in the context of the severe weakening of welfare systems. Secondly, I will explain in more detail what I mean by reverse retirement frontiers, and thereby make an effort to theorise them. Following a brief presentation of data and methods, the subsequent empirical analysis is structured in three sections: intergenerational motivations to migrate, aspirations of financial income in older age, and transnational learning about retirement. I will illustrate these themes, and the broader theoretical framework, with data from my long-term research with ageing migrants from Latvia, both Latvian and Russian speakers, and, when possible, place the findings in a wider discussion of similar trends from other post-Soviet countries. Finally, I will summarise the key conclusions and throw light on relevant future research avenues for post-socialist retirement migration.

Approaching retirement in Latvia

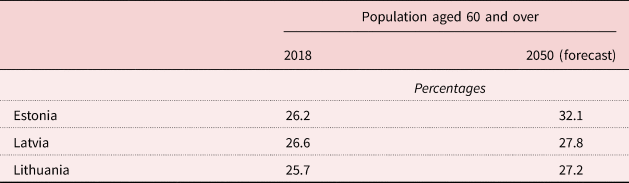

As a more-or-less global phenomenon, demographic ageing takes place in all post-Soviet countries, but in the Baltic countries this process is particularly advanced. More than a quarter of the populations in all three Baltic states are aged 60+ (Table 1). This is the combined result of very low birth rates throughout the period since the countries regained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and large-scale emigration in recent decades, especially since the countries joined the European Union (EU) in 2004.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, emigration trends were high in the Baltic countries and involved all age groups. Retired former military personnel also often relocated to Russia, but some moved to other former Soviet republics. The history behind this needs a brief note of explanation. During Soviet times, along with Moscow-led urbanisation and industrialisation, in-migration took place, mostly from Russia, but also from Ukraine, Belarus and other republics. Especially in Latvia and Estonia, in-migration significantly changed the ethnic proportions of the populations. Taking the case of Latvia, in the last census before the Second World War (in 1935) ethnic Latvians made up 77 per cent of the population, while in the last census during Soviet times, in 1989, the proportion had decreased to 52 per cent. Most of the in-migrating inhabitants lived in the largest cities. This in-migration, along with increased rural–urban migration, changed the patterns of care for older people, moving away from three-generation co-resident households towards more nuclear family livelihoods. During the period 1991–1995, more than 168,000 people left Latvia, mainly moving to Russia; among them more than 50,000 Soviet military officers. Roughly half of the ethnic Russians left, while the rest stayed with their families (Jundzis, Reference Jundzis2014).

Regarding emigration, the biggest influence has been the integration of Latvia and the other Baltic republics in the EU in 2004. While the majority of leavers are young, increasingly more ageing people have joined the outward stream. Statistics may not register the precarious moves of pre-retirement people, but in the case of Latvia, for example, at least 10 per cent of the emigrants in 2001–2011 were aged 55 and older, and the trend continues to grow (Hazans, Reference Hazans and Hazans2013; Lulle, Reference Lulle2018). Unlike the cases of Western European retired migrants, where ‘lifestyle’ motives are dominant, the emigration of ageing people from post-socialist countries is more related to working purposes. Moreover, many of those who emigrated at younger ages are reaching their mid-life and growing older in their places of immigration. Hence, questions about pensions earned abroad have appeared in the political agenda. Although the EU envisages portability of pensions (EU, nd), the biggest barrier for return to Latvia in older age is taxation rules. The European Latvian Association (2019) proposed that minimum pensions earned in other EU countries should be exempt from income tax, which created heated debates over pension inequality, but resulted in indecision. The current legislation stipulates that income tax should be paid for income from old-age pensions. The non-taxable minimum in Latvia was €300 per month in 2020. The return migration of post-retirement age groups (65+) is rather small in Latvia, although increasing: it was 174 (3.1% of all returnees) in 2013, rising to 336 (8.2%) in 2018 (CSB, 2020b).

Further evidence for the pauperisation of older age groups in Latvia is revealed by data on incomes, pensions and unemployment. According to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data for 2016, 39 per cent of women over 65 and 20 per cent of men (hence, 30% overall), had a disposable income which was less than half the median income for the population as a whole. This cut-off, which is the official threshold of poverty, showed that the poverty rate for older people (65+) has increased by 10 percentage points since the mid-2000s (OECD, 2019). On the pensions front, according to 2018 figures (CSB, 2018; Jankovska, Reference Jankovska2019: 33–35, 59), around 5 per cent of pensioners in Latvia receive less than €100 per month, 20 per cent receive below €250 and 59 per cent get between €250 and €400. An average pension for a 65–69-year-old was €332 in 2017, below the minimum monthly salary of €430. Pensions and other forms of social welfare were cut during the years of austerity following the global economic crisis, which hit Latvia and the Baltic states particularly hard. Pension levels have partially recovered since then, but are eroded by steady increases in the consumer price index. Regarding unemployment, mid-life and older age groups suffer disproportionately high rates, twice or three times the average for the total population; for 2019, average unemployment was 5.7 per cent, but it was 11.0 per cent for those aged 45–49, 12.6 per cent for 50–54, 15.8 per cent for 55–59 and 11.8 per cent for 60+ (Riga City Council, 2019). Across all these age groups, unemployment for women was higher than for men, due to persistent gendered and ageist stereotypes, care duties and demographics. It is also the case that post-Soviet countries such as Latvia are characterised by extreme inequality (Eurostat, 2019; CSB, 2020a; for the case of Lithuania, see Juska and Ciciurkaite, Reference Juska and Ciciurkaite2015). A few well-off older people can emulate leisure-oriented lifestyle migration trajectories, but most retired or pre-retirement people are rather poor, their relative poverty exacerbated by the neoliberal restructuring of the labour market in favour of younger workers, the legacy of austerity-driven reductions in welfare and old-age support, and rising costs of health care.

Not surprisingly, people who are physically and mentally able push their working lives further in order to enable better lives in old age (Ministry of Welfare, 2013; Opmane, Reference Opmane2018). While the working age has been incrementally increased, pensionable ages will be raised even further (Table 2). For instance, in neighbouring Estonia, retired people keep working and the situation is similar in post-Soviet Russia (Dingemans and Henkens, Reference Dingemans and Henkens2020). People continue in paid employment, if they can, with the main purpose of making ends meet (Kolev and Paskal, Reference Kolev and Paskal2002; Dingemans et al., Reference Dingemans, Henkens and Van Solinge2017). This trend illustrates a kind of rethinking of agency and ageing, and opens up new retirement frontiers, not for leisure, but for working purposes.

Table 2. Retirement ages in the Baltics

Work abroad around and after retirement age is a pragmatic solution for some, even if it is envisaged as a temporary or circular migration pattern. While flexibilisation and retirement have been studied in certain occupation groups in ‘Western’ contexts (Flynn, Reference Flynn2010; Danson and Gilmore Reference Danson and Gilmore2012), post-Soviet lifecourses, and especially migrant lifecourses, exhibit more intense economic, gendered and cultural intersections in terms of choice to emigrate for work. Push factors for emigration and its outcomes are gendered.

In immigration countries, older women work in seasonal jobs in agriculture, where often older instead of younger workers are preferred by employers due to their reliability and more serious attitude to this kind of work (Lulle, Reference Lulle2014). But most often these older female ‘economic migrants’ work in care, where older carers are desired for various care forms, including live-in care; sometimes a migrant care provider can be older than the person she cares for (Andall, Reference Andall2013). Older-age migration motivations for work abroad as a specific way of ‘frontiering retirement’ are at the core of this research. I will now explain what I mean by this.

‘Frontiering retirement’: theoretical considerations

The influences on ageing across geopolitical frontiers by two cultures or transnationally are increasingly studied by researchers on ageing and migration (e.g. Torres, Reference Torres2001; Hunter, Reference Hunter2011). I propose the notion ‘frontiering retirement’ as a conceptual tool to broaden debates about the processes of migration now taking place in post-Soviet and post-socialist countries. The idea of ‘frontiering’ comes from transnational family studies, where Bryceson and Vuorela (Reference Bryceson, Vuorela, Bryceson and Vuorela2002) coined the notion of ‘frontiering families’. This notion combines a dual meaning: (a) family members enact their agency in order to face and adapt to at least two different ways of life across frontiers; and (b) they need to be in the front line for supporting and maintaining their transnational families. I found this dual meaning an evocative departure point in conceptualising retirement migration in this study.

I argue that ageing post-socialist migrants confront and reshape retirement frontiers through at least two different systems, one in the lifecourse and the other spatial. First, they confront how ageing is socially constructed in particular societies, notably how the length of their working lives and social contributions were calculated before and after the collapse of the socialist bloc. Second, as a result of migration, ‘frontiering’ further takes place in at least two geographical contexts. Geographically, it involves the practice of crossing international borders and questioning the dominant notion of retirement migration as lifestyle migration. This case-study pushes the idea of retirement frontiers through a focus on migrating for work, not so much for leisure and lifestyle.

Ageing people are confronted with new cultural notions both in their rapidly changing home countries and when migrating abroad. Discourses of responsibilisation, reinventing the self, and material and ‘lifestyle’ consumption in post-Soviet society are directed not just at the younger age cohorts but also towards ageing people (Davidenko, Reference Davidenko2019); but the social support systems and incomes do not permit most of them to live up to such notions, especially their low pensions. In terms of retirement migration, the post-socialist case recontextualises existing notions of ‘active ageing’ (Moulaert and Biggs, Reference Moulaert and Biggs2012). Ageing people are not encouraged politically to emigrate; they ‘activate’ ageing in a bottom-up way. While the notion of ‘active ageing’ is usually applied to sedentary national contexts or, in the case of migration, to lifestyle migrants, post-socialist ageing migrants redefine active ageing through employment abroad.

The lifecourses of adults who are currently in their mid-forties or older correspond to the generational divide created by the post-Soviet transition; for many, the skills obtained under the Soviet education, agriculture and industrial systems turned out to be obsolete and no longer needed in the more neoliberal service and consumer-dominated economy which quickly emerged in the 1990s. Also, negative attitudes to ageing, starting in mid-life, are documented in academic research (Lulle, Reference Lulle2018) and policy documents (Cabinet of Ministers, 2016). However, jobs in agriculture and industrial production were relatively easily available in ‘Western’ countries, along with the manual work of cleaning. Most Latvian households cannot afford cleaners. So, former professionals became cleaners and care workers abroad (Lulle, Reference Lulle2014). Moreover, the social and economic frontiering of retirement prefigures intergenerational ways of life. Young and middle-aged migrants tend to support their retired parents back in post-socialist countries (Lulle and King, Reference Lulle and King2016). They see it as their moral duty and also as a necessity when the severely weakened welfare system – low pensions, difficult to access health care, which is also expensive – cannot provide basic needs to aged and poor people (Robinson, Reference Robinson2013). Some older people may try relocating to live with their emigrated children and receive at least a minimal pension in the country of immigration, if they qualify for such a pension (for the case of Hungary, see Illes, Reference Illes2006). Retirement frontiers are spanned through social contributions at least in two places: usually small-amount pensions are accumulated in the home country and then migrants try to earn additional pension rights in the country of immigration. However, this involves tackling bureaucracies. Even in the case used here – Latvian migrants in the EU and European Economic Area, where social transfers across the borders are formally in place – dealing with pension issues in at least two countries is difficult. Hence ageing migrants deal with socio-spatial and gendered inequalities, transnational social protection and occupational welfare, and enact agency through formal and informal practices of obtaining employment and welfare while simultaneously migrating and ageing (Ackers and Dwyer, Reference Ackers and Dwyer2004; Levitt et al., Reference Levitt, Jocelyn, Mueller and Lloyd2017). Research in various Western contexts shows that both the difficulties of making ends meet, on the one hand, and high occupational status and higher household income, on the other, may encourage post-retirement employment (in Finland, see Leinonen et al., Reference Leinonen, Chandola, Laaksonen and Martikainen2020; in the United Kingdom (UK) and other European countries, see Platts et al., Reference Platts, Corna, Worts, McDonough, Price and Glaser2019). However, ageing people in the post-socialist realm can amplify their retirement better by moving abroad for work reasons.

Data and methods

My research presented here builds on two projects spanning a decade-long study of family life transitions and migration in multiple countries: Latvian migrants in the UK, Norway and Finland, and transnationally living between these and other countries. The UK features as the most important destination for Latvian migrants, while migration to Nordic countries has increased in recent years. The core data analysed in this paper consists of life-history interviews made with 49 Latvian women aged in their forties, fifties, sixties and seventies. The ‘mid-life’ chronological age in the sampling, forties and fifties, is socially, culturally and politically significant, as these age groups represent a frontier: they came of age still in Soviet times and therefore experience and perceive ageing and migration opportunities with reference to the Soviet era as well. Moreover, I suggest that the mid-life stage is a particularly important and unexplored transition when the ageing process is considered.

The interviews, which were recorded and analysed thematically, took place in two periods of time, 2010–2014 and 2016–2018. The first source of interviews (39) comes from my doctoral thesis (Lulle, Reference Lulle2014), which also includes several more recent follow-up interviews. Much of my doctoral thesis fieldwork was done on the Channel Island of Guernsey, where there is a large Latvian presence. Some interviews were also carried out in London and Boston, where people moved for work during my UK fieldwork. While the Channel Island of Guernsey is not part of the EU, during my fieldwork in 2010–2013 it did take advantage of EU freedom of labour movement regulations. However, the island applies specific housing regulations. This means that migrants could stay on the island for up to nine months per year, if they were employed in agriculture or packaging, and up to three or five years, if employed in other sectors such as hospitality, services and office work. Women came from both rural and urban areas in Latvia. In Guernsey, more women from rural areas tend to work in the agriculture sector. Rural–urban mix was observed also in other European destinations. The second set consists of ten interviews with older migrant women who live in Finland and Norway. Most of these two groups of women maintain multiple links with localities in Latvia and regularly travel back there.

In both projects, I asked participants to describe their lives and life-events related to migration, education, family and working lives, first during the Soviet Union era and then after 1991 (McAdams and Bowman, Reference McAdams, Bowman, McAdams, Josselson and Lieblich2001; Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Kearns, Kontos and Wilson2006). Moreover, I applied new ways of triangulation of qualitative data. Beyond the recorded and transcribed interviews, I was able to place these narrated accounts in a broader ethnographic context. I engaged in multiple unrecorded conversations, observing family lives across generations and with diverse references to lifecourse virtues ‘then’ – in Soviet times and the early transition period – and ‘now’, in the mid- and late 2010s (Pratt and Fiese, Reference Pratt and Fiese2014: 15–16).

I undertook a thematic analysis of retirement frontiers. The three most common themes in the interviewee narratives were the complex intergenerational motivations for migration in later age, the participants’ minimum aspirations for social and economic security, and finally their transnational learning on how to live better in older age, which entwined geographical, cultural and social retirement ‘frontiering’. One final methodological note must be emphasised: the empirical evidence of Latvian migrants must be assessed in the context of the relatively ‘free mobility’ in the EU and European Economic Area.

In the following three analytical sections, I will firstly demonstrate how the phenomena of ‘reversing retirement frontiers’ works through intergenerational motivation. Ageing migrants compare their situation and future options with those of their parents’ generation. Additionally, the intergenerational motivation to migrate in older age is strongly influenced by the need and moral perception to provide for aged parents and children, even when the latter are grown up. Only then does the motivation to migrate turn back to the needs and hopes of ageing migrants themselves.

Secondly, ageing migrants strongly emphasise what they regard as their ‘minimum’ aspirations. This minimum is related to the pensions they got from Latvia or will get from work abroad, at a time when they are close to retirement or already retired according to the Latvian system. Minimum also refers to timing – how many years and months should a person work to accumulate some additional earning through migration. Furthermore, ‘minimum’ is what participants refer to as the material gains and needs for a slightly better life, especially in terms of their housing improvement.

Thirdly, retirement frontiers are also reversed through transnational learning. Such learning happens through comparisons and observations: how other pensioners live abroad, how other ageing migrants live, work and learn to negotiate their retirement income, and how retired people live back in Latvia.

Intergenerational motivation

In terms of their parents, who are often fragile and old, the research participants overwhelmingly emphasised how much they need and want to help them materially. The material situation of retired people in Latvia, in most cases, is frugal. As I demonstrated earlier, the majority receive pensions that are barely enough, or actually not enough, to make ends meet. In many cases, their daily expenses require extra help, usually from younger relatives. Moreover, many retired people, who are already experiencing age and health fragilities, spend a large portion of their meagre income on medicines and treatments. Unlike, for instance, in the UK, the health services in Latvia are not free and some are not even subsidised. Severe restrictions in welfare support were implemented as part of the austerity measures following the sudden financial crisis in Latvia after 2008. Further difficulties include the need to buy utilities and services, which make a considerable annual expense, such as coal or logs for heating in countryside houses or communal heating in flats, bearing in mind the long and cold winter season in Latvia. These hardships intersect with experiences of several crises during the turbulent post-socialist times: losing savings in the banking collapse in the mid-1990s, frozen annual pension indexation for inflation during the financial crisis in 2009–2011, and lay-offs that hit all, including many retired (but still working) people.

Hence, for some of the older generation, full retirement was forced upon them due to lay-offs. Experiences of the sudden loss of employment by their parents strongly inform the decisions to work abroad of current ageing migrants. Middle-aged participants emphasised intergenerational moral duties: they help their retired parents through remittances, motivated by the moral duty to do so, and by a broader sense of intergenerational solidarity. However, for some middle-aged migrants, in order to obtain a pension in the UK, the best help for their retired parents was to provide them with some short-term earning opportunities abroad. Maruta, in her forties at the time of the interview, arrived in Guernsey when she was still in her late twenties, and started from the bottom – doing manual agricultural work in greenhouses. After ten years, she was managing a team of short-term migrant workers:

Well, I like it best when I do not need to send money. I like to help with work opportunities. My mom can come and work here from time to time and make some money. She is retired already. I get a job for her, she has a place where to live [with Maruta's family, while working in Guernsey] and she can earn money herself. (Maruta, Guernsey, emphasis in italics)

Short-term work for the already-retired people I met is usually hard, physical work: in agriculture, in factories packaging goods or in cleaning of some kind – either in private houses or in hotels for women, and gardening or some sort of construction assistant jobs for men. On the one hand, Maruta and others who help their retired parents to find short-term employment somewhat ‘juniorise’ their older parents. This is a variation of what Davidenko (Reference Davidenko2019) has observed as discourses of responsibilisation of retired people in post-Soviet Russia. Precisely the same tactics – juniorisation as responsibilisation – are carried out by middle-aged parents for their children: they help their teenage kids to find a summer job during the Latvian schools’ long summer break of three months. On the other hand, these short-term jobs empower retired parents, and increase their autonomy and wellbeing. Ausma, already in her early seventies and long retired, kept coming back to Guernsey for years:

My energy comes from a sense of happiness. Sweat is dripping off me but the rooms [she cleans] are nice; my room [where she sleeps] is nice. And I earn in a week as much as I was able to earn in two months in Latvia, if working really hard. In fact, I get even more here, if I take extra [cleaning] jobs. (Ausma, Guernsey)

Her adult son helped in the beginning to get the job in Guernsey but then he himself left. Ausma kept coming independently, emphasising her empowerment through work and independent earning, which, in turn, makes life better when she is back in Latvia. For instance, her foreign income enables her to take holidays elsewhere in Europe, something she was unable to do during the Soviet Union's restrictive travel policy, or during post-socialist times and on a meagre pension.

Both the chronologically young (in their twenties and thirties) or middle-aged (forties and fifties) help their retired parents and grandparents by sending regular remittances. For example, Inese (late forties) was sending approximately the same amount as her mother's monthly Latvian pension: €130. ‘She could survive on her pension just about, but if a shoe breaks, if the doctor is needed, and medicines are getter more expensive all the time, it is not enough’, Inese rationalised. Others send payments for houses, flats and utilities to their ageing parents.

Many in their fifties said they do not think yet about their pension, like Arnis, in his fifties, who was specifically emphasising that he ‘does not think about such things, the main thing is to survive everyday life’. He, like others, was also laughing, albeit nervously, when pronouncing the word ‘pension’ as it will, sarcastically, be a laughably small amount. But the most important factor which informs pre-pension-age migrants is to earn for their children's needs:

I have not thought about my pension. My aim is to send my children to universities, and only then can I think about myself. I need to help and push my children on the right tracks first. (Zaiga, London, fifties)

Solari (Reference Solari2010) has aptly explained how migration, specifically the migration of older women, feeds into the state's efforts to reorganise gendered orders in families, by making women more independent. The state is absent in the case of retirement migrants because many migrate precisely due to poor welfare provisions; but the state is also present, as these ageing migrants are embodied ‘facts’ on how individuals can improve their lives. Hence, the ‘success’ of retirement migrants can be used in public discourses on the successful ageing of post-socialist retirees, whose lifestyle and income, due to high inequality in the origin society, resemble more those of ‘Western’ pensioners.

Minimum aspirations

Aspirations for a good life in older age are interwoven with mobility motivations. Such aspirations are mainly pursued through pushing the retirement frontiers outwards (by emigration), forward (by working during retirement age) and making frontiers porous (by transnational linkages). However, in most of the participants’ narratives, a persistent trope is the notion of ‘minimum’. I will illustrate in this sub-section in which domains this minimum for a better life is envisaged, and how.

Minimum aspirations are pragmatically linked to low earnings or precarious employment during the post-socialist changes of the 1990s and 2000s. ‘Minimum’ hopes are specifically related to a pension, not the overall economic and financial future. Not infrequently, research participants otherwise were dreaming about becoming landlords, buying a property that would bring in a good rental income; or, again, in the words of several unrelated participants, were fantasising about winning the lottery. But mainly pre-retirement and already-retired people were working abroad to make some extra money for everyday needs, and had not even enrolled in pension schemes in the UK. Sarmite, in her late fifties, was a nurse in Latvia and was able to negotiate with her hospital that she could go to Boston in Lincolnshire to work in agricultural jobs for up to three months. She did this for several subsequent years, in order to satisfy very specific house-improvement targets at home:

Windows have been replaced one year, a new roof for the house next year. There are many needs to improve the house. (Sarmite, Boston)

Everyday rental and maintenance payments for a flat or a house are among the main push factors why people look for work abroad. While the retirement age is increased gradually, uncertainty prevails when, if at all, people will manage to reach their retirement years and get their small Latvian pension. Hence, work abroad, for shorter spells over several years, like for Sarmite, is the key to maintaining minimum needs now: she has been able to pay for utilities, heating in winter and generally maintaining the property.

In terms of their own pensions, the hope was for a minimum to be able to survive satisfactorily. However, due to the accumulation of transnational work experience and social protection, a minimum pension from one country is topped up with the additional minimum accumulation in another country too. This was a pragmatic ‘frontiering’ by most, as the fear of old-age poverty, if relying on the minimum only in Latvia, is real.

Future retirees need to accumulate some years of working life abroad but also need to reach official retirement age. Rudite, still pre-retirement age, stated:

I am not sure whether I will ever be able to live only in Latvia. I may have earned a minimum working life period here already. But I have to wait until I am 65. It is a lot. It means ten more years of waiting and coming here again and again, and again. (Rudite, fifties, Guernsey)

But Astrida, already retirement age, illustrated her dual engagement in frontiering retirement as follows:

My pension is very tiny. But [the British state] helps. Since the pension is so small [British civil servants] recommended that I continue working until I have worked ten continuous years in the UK. Then I will get some kind of minimum, really, the minimum. But they help and advise in other ways too: I get working tax credit, other allowances. Theoretically, I could stop working since I have a minimum pension from Latvia too but I will try and continue earning as long as I can. (Astrida, London, sixties)

As soon as she turned 58, she started receiving letters from the UK Work and Pensions Department. They reminded her that she is approaching retirement, told her about working-life rules, about options she has and so she got regular updates each year on how to reach the UK minimum pension; the full minimum was £168.60 a week in 2019 but many migrants could not obtain this full minimum due to their short length of employment in the UK.

However, for some, the minimum pension from Guernsey (not constitutionally part of the UK or EU) may not be possible due to the too-short working time there. Even in these cases, a discourse revolves around a minimum, which should be somehow secured:

One person says it is possible to get a pension from Guernsey, the other says it is not. But I do not count on a pension from here [Guernsey]. If I get it, fine, if not, nothing to do. I started paying into a private pension fund in Latvia, a very small amount but then I was told that this money is frozen [due to the economic crisis]. It is a very small amount but I do not touch it. At least something, a very little bit I may have [when I retire]. (Valentina, Guernsey, fifties)

The working conditions of pre-retirement participants in Guernsey and the UK were usually physically demanding and often precarious too (Dingemans and Henkens, Reference Dingemans and Henkens2020: 2054–2055). But in Norway, the sense of welfare security was significantly higher. Participants at pre-retirement age also tend to stay put to maintain this sense of current security:

I am simply living my life to the fullest right now. It seems to me so far that since everything is normal now, especially with work, everything happens. I will have a pension as well. I don't think that it is necessary to save something on purpose, you save a bit by bit anyway, but it is not like if we are saying no to something that we want. (Marite, fifties, Norway)

In another case, Zenija migrated to join her daughter in Norway when Zenija herself was already close to Latvian retirement age after her husband died. This experience has influenced her view on life in Latvia too for her generation. Therefore, she also prioritised the security of ‘now’:

I believe I won't get a good result [referring to qualifying for her pension in Latvia], maybe just the minimum. I won't receive anything much and our generation, between years 50–60, are terribly unhealthy in Latvia. Now I am in Norway. There's fresh air, hills, I lack nothing. Right here I feel alive. (Zenija, sixties, Norway)

Zenija also engaged in language learning as soon as she arrived and did casual cleaning work for money, apart from the economic security provided by her daughter. In sum, minimum aspirations clearly underpin the post-Soviet generation which is retiring soon, whether they continue circulating between Latvia and abroad, or staying put in the country of immigration.

Transnational learning

Frontiers, either physical and political borders or social separation lines in lifecourses and between cultures, are further recontextualised through learning about the ways of life retirees live in different places. Participants reveal learning through comparisons and reflections with the lives of other pensioners whom they observe or encounter.

Narratives revolve, for example, around issues on how retired ‘locals’ live abroad or where they prefer to retire geographically. Brigita was working in a cafeteria in Guernsey. Local retirees and older tourists were her usual customers. She related how retirees spend their days walking from one cafe to other, comparing the service, and how they disappear during the coldest months, reappearing again in spring:

Those who have enough money, they have second homes in a better climate and they spend most of the winter in the sunshine. (Brigita, fifties, Guernsey)

Retiring ‘under the sun’ was rarely a plan of my research participants; rather it was a fantasy, inspired by such observations. Post-Soviet countries are characterised by high inequalities: a few relatively well-off people emulate lifestyle migration and trajectories similar to other Western countries, e.g. alternating between two or more international homes seasonally. No informants in my sample could afford it, and only scattered examples were mentioned in regards to some of their acquaintances.

Older migrants also extended their comparisons on how other ageing migrants live and work, and how retired people live back in Latvia. Despite a prevailing pessimism surrounding minimum income in old age, some participants demonstrated considerable agency. They found formal and informal ways of obtaining support in older age (for the case of older migrants in the UK, see Ackers and Dwyer, Reference Ackers and Dwyer2004). My participants emphasised that states, either in the UK or Nordic countries, were considerably more oriented towards explaining the welfare regimes and rights, as illustrated by the interview extract from Astrida above. This, in turn, empowers them to seek further information through social networks (Ackers and Dwyer, Reference Ackers and Dwyer2004), despite their lack of or minimal language skills. While many avoided thinking of their pensions, scared of how negligible they might be, some regretted that they did not have such knowledge and confidence before:

I do think about my pension now. But when I was working in a private care home for the elderly, the company did not contribute anything towards my own pension. The same was in [her other previous job] in a hotel. They said [that pension contributions are]: ‘Not applicable’. In a shop where I work now, the employer pays 8 per cent from my salary into a pension fund. I am now thinking that I had to worry about the pension already earlier, but it turned out as it was. (Laimdota, fifties, Guernsey)

Issues with pensions go hand-in-hand with other social allowances and support: in state and civil service work there is guaranteed annual and sickness leave. Many women, who arrived in Guernsey in the late 1990s, began with no social guarantees at all, and their work time did not count towards pensions either. The situation was considerably different in Norway, where all the interviewees who worked, received social guarantees. This system was highly appreciated by research participants:

An employer must pay a certain amount towards our pensions. And when you retire, you know that you will have this money. However, I would have a full pension only if I have worked 40 years in Norway. In my case this is simply impossible. So, according to the current laws, I will make only the minimum pension. (Irina, fifties, Norway)

Since she is preparing to stay in Norway for good, hopes for minimum pensions require preparations now. Therefore, Irina learned that she will be better off if she owns her own property. She bought an apartment. Paying rent with the minimum pension in older age would not be a feasible option for her.

For those who are very close to retirement or already retired, learning about transnational social transfers in practice causes lengthy problems. Tamara, for instance, was working both in Latvia and Finland, and taxes were deducted in both countries. When she reached the retirement age in Latvia, she learnt that several years were not included in the total count. She had mainly precarious jobs in Finland, including work for Latvian-owned enterprises there. Despite the formal EU framework of social transfers, in reality she had to ‘fight’ a lengthy battle:

When I started working in Finland, the Latvian state took away my accumulated pension from Latvia. Working-life length, accumulating towards pensions, was also taken away. I wrote to complain to both sides – Finland and Latvia – but it is not solved yet. (Tamara, sixties, Finland)

Similarly, other pensioners I interviewed had to learn, and quickly, complicated transnational regulations that had many concessions, individual interpretations and delays in decision-making about pensions. In cases where complexities intersect, such as work in different countries under different regimes (Soviet and after the collapse of the Soviet bloc, widow's pension and other entitlements, etc.), migrants who are effectively fending for themselves are placed in very unequal power relations to solve their pension issues. This learning involved mobilising social networks among Latvian pensioners, local acquaintances, and paying multiple visits and writing letters to state institutions. Some even hired private consultants in order to cope with the bureaucracies.

Stable welfare regimes that include ageing people into pension schemes became increasingly important for the research participants during the later years of my research in the mid- and late 2010s. Some of those who were in Guernsey, with its specific regulations, contemplated relocating, for instance to Germany, for the last decade before retirement, precisely due to their hope of receiving a minimum pension from there. Since 2014, due to the Latvian emigrant community's initiative, issues of pension transfers were brought up on the international agenda between Latvia and Guernsey (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2014), with no ultimate result yet in mid-2020.

Finally, several participants decided, through intergenerational learning, that they would not have enough individual old-age income in either country. So, Anita, 64 years old, was still working in Guernsey in the hospitality sector when I interviewed her. She supported one of her daughters, still living in Latvia, from her salary earned in Guernsey. Her other daughter lives in the UK. Anita's health was deteriorating, she was suffering constant back pain. The daughter in Latvia was sending her strong pain-killers, wrapped inside greeting cards. Anita judged that she will not be able to accumulate the full 450 work weeks to qualify for Guernsey's pension, neither could she survive on her Latvian minimum pension. She said she will move soon to her daughter in the UK where the daughter, as a care provider, will receive a social allowance for looking after her mother.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper has reoriented ideas of active ageing and new retirement frontiers through investigating the case where people in their mid-life, close to retirement age or already retired, migrate to begin a new working life abroad. In my research, I contribute a relevant broadening of the concept of active ageing by ‘democratising’ active ageing as a bottom-up process undertaken by people themselves instead of a top-down policy construct.

The case is rooted in the post-Soviet legacies of severely weakened social systems and disruptions of the accumulated lengths of people's working lives. The focus on post-Soviet migrants broadens the range and reveals different types of active ageing through migration. I illustrated my analysis with the experiences of ageing Latvian women (mainly) and men working abroad. With the methodological strategy of developing an analysis from the migrants’ own perspectives, I proposed the novel notion of ‘frontiering retirement’. The conceptual significance for broadening the debate on the concept of active ageing has been discussed through empirical data on how migrants are reversing retirement frontiers in three main ways. First, they cross geographical frontiers in the hope of finding better lives in their older age abroad, therefore, they are pushing the retirement frontiers outwards through emigration; second, while themselves approaching retirement, they push retirement frontiers forward and begin a new working lifecycle; and third, migrants span cultural boundaries of various understandings about ways of life in older age and make retirement frontiers porous through transnational learning. Hence, I provided an empirical route to re-think fundamentally some big issues in retirement migration research in this global era of ageing. Active ageing therefore means taking into account the prospect of retirement well before pensionable age. Older people from relatively lower-income countries have strong incentives to migrate for work and to accumulate pensions, given that European political regimes now permit ‘free’ movement, transnational living and pension transfer arrangements.

Ageing migrants are frontiering retirement, firstly, through intergenerational motivation. They carry the memories and experiences of the poverty of their parents, on the one hand, and are influenced by large emigration flows of younger people, on the other. Some go abroad to earn for their grown-up children and grandchildren, others remit to their aged parents, putting their own pension needs in last place. Older people generally engage in precarious and physically demanding jobs. Furthermore, already-retired people engage in casual work abroad in order to earn money to pay for bigger expenses, usually to maintain property and pay for utilities back home.

Secondly, older migrants, whose working lives were ruptured by post-socialist transitions, typically have minimum threshold aspirations for their pensions. Social contributions paid in Latvia were too low for most older people, while the ‘race against time’ – they migrated to the UK or Nordic countries while already ageing – does not give much hope for higher pensions. However, when both minimums – from Latvia and a job abroad – are combined, most are considerably better off than if they had remained in Latvia. While some researchers may denote relocation to children abroad as ‘pension seeking’ (Illes, Reference Illes2006), the Latvian case rather exemplifies that some post-socialist ageing migrants are ready to sacrifice a lot, including their health, while pushing the retirement frontiers through hard work, as long as their bodies allow.

Thirdly, older people learn about life prospects from their co-nationals who have emigrated, and observe the lifestyles of their Western counterparts. Furthermore, despite formal social transfer systems in the EU (and wider European Economic Area), older working migrants face the frustrating opacity of bureaucracy and find themselves fighting and intensively learning about their rights and entitlements. People gather considerable social and informal support and enact agency to approach the bureaucracies of states where they worked and formerly lived, and seek justice in consolidation of their life-time social contributions. Other older migrants still do not qualify for state pensions and need to rely on intergenerational support. It must be emphasised that the case of Latvian migrants is relatively ‘easy’ because Latvia is a member of the EU and policies of social transfers are developed within the EU and European Economic Area. It is much more difficult for migrants from other former Soviet countries outside the EU. While some evidence emerges from a study on gendered migration and ageing from Ukraine (e.g. Solari, Reference Solari2010), more research is urgently needed to unpack experiences of older migrants from all of the post-Soviet countries. Such research would provide evidence for policies that go beyond Western contexts.

The Latvian case provides lessons for further inquiries in this relatively new phenomenon of migrating for work in mid-life and later, precisely with the aim of achieving better old-age income. Due to several economic crises in the 1990s and 2000s that exhausted their savings, older people got trapped in areas where they moved for work purposes and could not easily move internally, even if they wanted (Heleniak, Reference Heleniak2002). When the Soviet Union fragmented, almost 7 million people from the former Soviet Republics relocated to Russia during the 1990s, as I explained in the case of military personnel in Latvia. Along with dramatic political and socio-economic transformations, the outer borders of the former Soviet empire literally opened new frontiers for migration. Besides, this former space, along with other post-socialist countries in Central and Eastern Europe, is rapidly ‘greying’ (Hoff and Perek-Bialas, Reference Hoff and Perek-Bialas2015). For comparison, in 1990, after the collapse of the socialist system, the Central and Eastern Europe countries which joined the EU in 2004 and 2007 had around 10–13 per cent of their populations aged 65 years and older. The estimates show that by 2030, the 65+ population in Central and Eastern Europe countries will be from 20 to 36 per cent of their inhabitants (Lanzieri, Reference Lanzieri2011).

The retirement age varies mainly from 55 to 65 years and is set to increase in most countries (United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, 2016; OECD, 2017; Rybak, Reference Rybak2018; Pension Watch, 2020). Longer working lives is one of the key goals for ageing societies now in the post-socialist realm. The common trend in post-Soviet countries is that the very low retirement age of 55 for women is being gradually increased. Already in the early 2000s, Heleniak (Reference Heleniak2002) forecast that, in order to maintain pensions, the retirement age would need to be increased to 73 in the first few decades of the 21st century in Russia – the biggest country of the collapsed Soviet Union. It has not happened, however. Similar increases would be necessary in many post-socialist countries. Due to increasing life expectancy in Russia, from 65 in the mid-2000s to 72 years by 2017, the term ‘effective retirement’ which reflects an increase in the retirement age is being used to tackle the ageing challenge (World Bank, 2019). Active ageing through migration for work can diversify these debates as many mid-life and older post-Soviet migrants work in Western countries. Economic incentives to migrate are strong as the historical legacy of financial crises and diminishing welfare support informs poverty nowadays. Average pensions throughout the former Soviet Union are low. For example, in Russia, according to Rosstat (2017), the average pension in 2016 was 12,440 rubles (€179), equivalent to 34 per cent of an average monthly salary in the country. In Ukraine, the average pension in 2016 was ever lower – just €61 per month; and similarly in Moldova, the country with the largest proportionate emigration among the post-Soviet countries, the mean pension was only €59 (Meydan TV, 2016; Cojocari and Cupcea, Reference Cojocari and Cupcea2018). Hence, studies in ageing and migration could provide further understanding on how people manage active ageing in their own terms, often by overcoming difficult migration regime hurdles.

With this research I place the debate on new ‘retirement migration frontiers’ in a context where global inequalities are revealed in sharp relief: ongoing challenges of poverty, emigration and shifting retirement age in the ‘Global East’ (cf. Müller, Reference Müller2020) versus wealthier, new destinations-seeking retirees in ‘West’ Europe. This is equally relevant for many low- and medium-income countries across the globe, especially those which, like the post-Soviet states, have experienced periodic turbulences and even collapse of social systems. This sheds light on future research needs. More research in different empirical contexts from post-socialist countries is needed, including cases beyond the relatively ‘free’ EU mobility regime. As the world is ageing, new empirical evidence on ‘frontiering retirement’ is urgently needed, and holds a policy relevance as well, in a world with increasing socio-economic inequalities among retirement-age people.

Acknowledgements

I thank sincerely research participants for sharing their life stories. Many thanks to the journal editors, Prof. Russell King and Prof. Sarah Holloway for their continuous support and advice during multiple reviews. I happily acknowledge the European Social Fund, which funded my dissertation research at the University of Latvia and the Academy of Finland's grant for the project ‘Inequalities of Mobility: Relatedness and Belonging of Transnational Families in the Nordic Migration Space’ (2015–2019), led by Prof. Laura Assmuth.

Financial support

This work was supported by the European Social Fund; and the Academy of Finland.

Ethical standards

The University of Latvia PhD research did not require official ethical approval in 2010-2014, when the research was carried out. However, full international ethical guidelines were applied by the author. The University of Eastern Finland gave ethical approval to the for the Finland Academy project Inequalities of Mobility: Relatedness and Belonging of Transnational Families in the Nordic Migration Space (2015–2019), grant number 14960-288 552 data from which are included in this study.