That bilingual speakers are rarely balanced regarding their two (or more) languages in all linguistic dimensions and contexts of language use is a well-established fact in research on bilingual language development, already acknowledged in early work by Weinreich (Reference Weinreich1953) and further discussed in influential publications such as Grosjean (Reference Grosjean1982). We also know that language balance in bilingual speakers is not static; it may change when input conditions change in the course of the speakers’ lives (De Houwer, Reference De Houwer2011). For instance, long-term migration is assumed to significantly impact migrants’ shift from preferring to communicate in their first language (L1) toward a preference to use the language of the host society (normally, their second language/L2) (Clyne, Reference Clyne1991; Jia et al., Reference Jia, Aaronson and Wu2002). Factors such as changes in the family composition, age of migration, language policies, size of the migrant community, and even traumatic experiences suffered in the home country and associated with the L1 further influence the degree and speed of dominance shifts (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Aaronson and Wu2002; Montrul, Reference Montrul, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016; Santello, Reference Santello2014; Schmid, Reference Schmid2002). Depending on the definition of dominance (see the section “Measuring language dominance”), its shift at the individual level may be understood as a change in the relative strength of the bilingual’s two (or more) languages. The effects of such shift may be visible at the level of language preferences, language control, and code-switching or language proficiency in different domains (e.g., oral fluency, writing, lexical repertoire).

This study focuses on a group of bilinguals who are particularly vulnerable to processes of dominance shift, namely returnee heritage speakers (HSs), henceforth called returnees. Returnees are bilinguals who grow up in a migration context, normally as second-generation migrants, and at a certain moment of their life move to their (parents’) country of origin (Flores, Reference Flores, Schmid and Köpke2019). As a result, these bilinguals experience a reversal of the dominant environmental language at a certain age (during childhood, in adolescence or as young adults). Crucially their heritage language (HL) becomes the language of the wider community after return, whereas the former societal language (SL) turns into a minority language (Daller, Reference Daller1999; Flores & Snape, Reference Flores, Snape, Montrul and Polinsky2021).

This change raises several interesting questions pertaining to the issues of language attrition and reactivation. Since the exposure to the previous dominant language is drastically reduced or even ceases in many contexts of daily life (see Flores, Reference Flores2010), wherein the HL is employed instead, one may wonder whether such change leads to a dominance shift from the former SL to the HL. Moreover, how to characterize and account for the dominance shift in returnees still remains a largely unsolved puzzle. In this study, we address these questions by looking into language dominance in three groups of adult bilingual speakers of Portuguese and German: (a) Portuguese-descendant HSs who live in a German-speaking country; (b) highly proficient Portuguese late learners of German; (c) returnees, who grew up in a German-speaking environment but moved to Portugal at different stages of life, for example, childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood.

Dominance shift in bilingual speakers

Measuring language dominance

The concept of language dominance has been widely discussed in the literature (see Silva-Corvalán & Treffers-Daller, Reference Silva-Corvalán and Treffers-Daller2016, for an overview). Broadly defined, language dominance refers to the degree of balance between the two (or more) languages of a bilingual speaker. One key feature of language dominance is its multidimensional construct, including language proficiency, language exposure, and language use (De Cat, Reference De Cat2020; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018). Many studies on bilingual language development resort to solely one of these indicators as proxy for bilinguals’ language dominance, for instance, determining dominance either in terms of relative proficiency or of the amount of exposure and/or use of two languages (see Flores et al., Reference Flores, Kupisch, Rinke, Pericles Trifonas and Aravossitas2017; Treffers-Daller, Reference Treffers-Daller2019). In the literature, the former is normally referred to as performance-based measurements, whereas the latter as experience-based measuring procedures (Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018). Whilst the state of language dominance cannot be wholly inferred from one single component, it has been shown that there is a relationship between different indicators, for example, language proficiency tends to positively correlate with language exposure and use (Bedore et al., Reference Bedore, Peña, Summers, Boerger, Resendiz, Greene, Bohman and Gillam2012; Bonvin et al., Reference Bonvin, Brugger and Berthele2021; Treffers-Daller, Reference Treffers-Daller2019; Unsworth, Reference Unsworth, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016). Thus, performance-based and experience-based measures may yield comparable estimations for language dominance, although each method has its own strengths and weaknesses (for a detailed discussion, see Treffers-Daller, Reference Treffers-Daller2019).

With respect to performance-based measurements, which target the relative proficiency in the two (or more) languages of a bilingual, it is necessary to consider the way proficiency is determined. Language proficiency can be broadly defined as linguistic ability and fluency in a language (Montrul, Reference Montrul, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016). It covers “those aspects of language that usually constitute the outcome measures or dependent variables for linguistic investigations – that is, measurable phenomena that relate to the knowledge, use and processing of all of a bilingual’s languages at all linguistic levels” (Schmid & Yılmaz, Reference Schmid and Yılmaz2018, p. 2). Depending on the bilingual population under investigation (children or adults, biliterate bilinguals or speakers who are literate in only one language), a wide range of instruments can be administered to estimate the proficiency of a certain language. They comprise, for instance, the mean length of utterance, lexical knowledge/diversity, phonological performance, or employing grammar tasks and standardized language assessment tests widely used in academic contexts (Montrul, Reference Montrul, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016). Although there is no doubt that proficiency cannot be reduced to one single language domain (e.g., phonology, lexicon, or grammar, see Schmid & Yılmaz, Reference Schmid and Yılmaz2018), it is hardly feasible to assess all indicators of language proficiency in a single study due to time limits. Moreover, one has to bear in mind that variation is inherent to human language and even more to bilinguals’ linguistic outcomes (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean2008). It would be unrealistic (and impracticable) to strive for a way to capture all facets of bilinguals’ performance outcomes. Therefore, estimating language proficiency on the basis of one relevant indicator has been a common practice in research on bilingualism, which turns out to have enriched the field with insightful and replicable results. Among several indicators of global language proficiency, it has been argued that lexical competence is a reliable predictor (Bonvin et al., Reference Bonvin, Brugger and Berthele2021; Laufer & Nation, Reference Laufer and Nation1999; Treffers-Daller & Korybski, Reference Treffers-Daller, Korybski, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016), because adequate lexical knowledge is considered to be a prerequisite of effective language use and the lexical knowledge normally grows when proficiency increases.

Important to highlight in this domain is the distinction between absolute and relative proficiency (Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018). The absolute proficiency of a given language can be obtained in a straightforward way by testing a bilingual’s performance in that language (at least in the tested domain). Dominance, however, “implies a relative relationship of control or influence between the two languages of bilinguals” (Montrul, Reference Montrul, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016, p. 16). Thus, for the construct of dominance with performance-based measurements, it is essential to determine the relative strength of bilinguals’ proficiency in each language. One way to do so is to subtract the performance outcome of one language (e.g., a test score) from that of the other language, obtaining the so-called between-language subtractive differentials (Birdsong, Reference Birdsong, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018; see Treffers-Daller & Korybski, Reference Treffers-Daller, Korybski, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016 for several constraints that have to be considered when using this approach). To illustrate, for a bilingual who scores 80 out of 100 in the proficiency test for Language A, and 40 out of 100 in the analogous test for Language B, the Language A dominance index would be 40 (see the section “DIALANG vocabulary test in German and in Portuguese”). The interpretation of between-language differentials is rather straightforward: scores close to zero are indicative of language balance, while higher scores in the negative or in the positive direction signal imbalance in favor of one language, which is classified as the dominant one. Another way of assessing the relative weight of two languages is to apply the ratio method (see Flege et al., Reference Flege, Mackay and Piske2002). Between-language ratios are normally computed by dividing the smaller of the two raw proficiency scores by the larger one, yielding a dominance index between 0 and 1 (see Birdsong, Reference Birdsong, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016, for further discussion). Returning to the illustration above, for the bilingual who scores 80 in Language A and 40 in Language B, the between-language ratio would be 0.5. As for the ratio-based dominance index, a ratio approaching 1 indicates a tendency toward a balance between both languages (see the section “DIALANG vocabulary test in German and in Portuguese”).

Experienced-based measures of language dominance quantify variables related to language exposure and use, usually through background questionnaires. The underlying assumption is that the type and amount of contact that bilinguals have with each of their languages determine the relative strength of these languages in their minds, that is, the degree of language dominance. Unsworth (Reference Unsworth, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016) and Unsworth et al. (Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018), for instance, tested language dominance of bilingual children by estimating the relative amount of language exposure and use with a parental questionnaire. Similar proposals have been made to assess language dominance in bilingual adults (Dunn & Fox Tree, Reference Dunn and Fox Tree2009; Jia et al., Reference Jia, Aaronson and Wu2002). Much like proficiency-based models, the experience-based outcome for one language only predicts the absolute amount of contact with that language. The relative weight between exposure to two languages are measured by subtraction procedures. To quantify the degree of exposure with more precision, the questionnaire normally targets a wide range of components of bilinguals’ lives (number of interlocutors speaking each language, activities performed in each language, languages used at school and work, etc.). It is believed that these variables serve as snapshot at the moment of data collection or cumulatively at different periods of life (Tao et al., Reference Tao, Cai and Gollan2021). In fact, many studies that compare experience-based and performance-based measurements of language balance found that the quantification of language exposure and use can be used as a proxy for language dominance because they are correlated with measures of language proficiency (Bonvin et al., Reference Bonvin, Brugger and Berthele2021; Dunn & Fox Tree, Reference Dunn and Fox Tree2009; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018).

Furthermore, dominance may vary according to the various domains of language use and dimensions of language proficiency (see Birdsong, Reference Birdsong, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016, for the definition of domains and dimensions of language). An HS, for instance, may be more balanced in contexts of daily communication, feeling comfortable in using both the HL and the SL, but much more dominant in the SL in contexts of formal communication, particularly when writing skills are required. In addition, both language experience and proficiency provide continuous quantifications, but very often bilinguals are assigned to categories (Bedore et al., Reference Bedore, Peña, Summers, Boerger, Resendiz, Greene, Bohman and Gillam2012). However, there is a growing consensus that language dominance is inherently gradient, rather than categorical (Birdsong, Reference Birdsong, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016, p. 86; Treffers-Daller, Reference Treffers-Daller, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016, p. 253).

Finally, self-ratings of relative language proficiency by bilinguals may also be valid to classify a speakers’ language dominance (Hakuta & D’Andrea, Reference Hakuta and D’Andrea1992). Jia et al. (Reference Jia, Aaronson and Wu2002), for instance, asked their Mandarin–English bilingual participants to self-evaluate their speaking, reading, and writing skills in both their L1 and L2 as a complementary way of measuring their language proficiency. They found a positive correlation between the self-evaluated and the behaviorally measured language proficiency (assessed through a Grammaticality Judgment Task in English and in Mandarin), indicating that self-assessment of language dominance may be taken as a complementary criterion to determine bilinguals’ language balance, in addition to more objective measurements.

When dominance shifts: Reversal, attrition, and reactivation

As discussed above, early bilinguals are often more dominant in one language than in the other. Language balance may vary across different domains and dimensions of dominance (Birdsong, Reference Birdsong, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016; Fishman, Reference Fishman1965). Furthermore, dominance may change over the speaker’s life span (Grosjean, Reference Grosjean1982). While this observation is not controversial, empirical evidence for dominance changes across the lifespan is less available than we would expect.

For bilingual children, in particular for child HSs, it is assumed that a significant change in language balance occurs when entering the school system, particularly when the main language of instruction is the SL (Benmamoun et al., Reference Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky2013; De Cat, Reference De Cat2020). For instance, in a study on global accent in German–Russian bilingual children living in Germany (with Russian as HL and German as SL), Kupisch et al. (Reference Kupisch, Kolb, Rodina and Urek2021) compared preschool with primary school children and concluded that a significant change in their accent occurred in this age span. The authors argue that this may be the consequence of quantitative and qualitative changes in language exposure (maybe also in language attitudes), and be indicative of changes in language dominance toward the dominant SL (German).

Normally the imbalance in favor of the SL, initiated at school age, remains over the HS’s life span. It may become even more pronounced with growing age, particularly when HSs leave their parents’ home and constitute their own family. As a consequence, adult HSs tend to be considerably more dominant in the SL than in the HL (Rothman, Reference Rothman2009). Although this imbalance is ubiquitously assumed in research on different HLs across the globe (Montrul, Reference Montrul, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016), many studies only target the HL itself, instead of measuring the relative strength between both the HL and the SL (naturally, there are many exceptions, e.g., Lein et al., Reference Lein, Kupisch and Van der Weijer2016).

In the current globalized world, the country of residence is less and less frequently a constant in an individual’s life. Migration, due to economic and/or political reasons, is an integrative part of globalization; also repeated migration (migrating several times to different countries) and remigration (moving back to the country of origin) are growing realities. In particular how cases of repeated migration and remigration affect bilinguals’ language dominance is still not systematically investigated (see discussion in Kubota, Reference Kubota2019).

In cases of remigration of second-generation HSs, the loss of contact with the previous SL and increasing exposure to the HL leads to a reversal of the speaker’s bilingual situation. The loss of exposure to the former SL may cause processes of language attrition in different linguistic domains, particularly when the return occurs during childhood (Flores, Reference Flores2010, Reference Flores2020; Yoshitomi, Reference Yoshitomi and Hansen1999). In contrast, how such a return affects the HL has been little explored yet. Since returnees move to the country where the HL is now the SL, one may predict that linguistic properties that stagnated in HSs’ competence due to restricted contact with the HL during migration may further develop after return (i.e., be reactivated). Supporting evidence comes, mainly, from studies on Turkish returnees, who moved (back) to Turkey from Germany (Antonova-Unlu et al., Reference Antonova-Unlu, Wei and Kaya-Soykan2021; Daller, Reference Daller1999; Daller & Yıldız, Reference Daller, Yıldız, Treffers-Daller and Daller1995; Kaya-Soykan et al., Reference Kaya-Soykan, Antonova-Unlu and Sagin-Simsek2020; Treffers-Daller et al., Reference Treffers-Daller, Özsoy and van Hout2007; Treffers-Daller et al., Reference Treffers-Daller, Daller, Furman and Rothman2016). Research on other “reactivated” HLs is still residual (see Flores & Rato, Reference Flores and Rato2016, on global accent, and Kubota et al., Reference Kubota, Chondrogianni, Clark and Rothman2021, on the narrative abilities of children who returned to Japan from an English-speaking country).

The existing studies, which focus on different linguistic properties and use diverse methodologies, come to different conclusions regarding the question of full reactivation of the HL. Daller and Yıldız (Reference Daller, Yıldız, Treffers-Daller and Daller1995), Treffers-Daller et al. (Reference Treffers-Daller, Özsoy and van Hout2007), and Treffers-Daller et al. (Reference Treffers-Daller, Daller, Furman and Rothman2016), who analyzed the overall proficiency of returnees, their knowledge of syntactic embeddings, and of collocations in the heritage Turkish, respectively, argue that the returnees’ HL becomes indistinguishable from their homeland peers about eight years after return. Kaya-Soykan et al. (Reference Kaya-Soykan, Antonova-Unlu and Sagin-Simsek2020) and Antonova-Unlu et al. (Reference Antonova-Unlu, Wei and Kaya-Soykan2021), on the other hand, show that even after a decade of residence in Turkey, the returnees deviate from monolingual controls with respect to the use of evidentiality markers.

There are also studies showing persistent difficulties of returnees in catching up with monolingual counterparts at school, due to HSs’ low academic skills in the HL as well as to the difficulties of the homeland’s school systems in attending to returnees’ specific educational and linguistic needs (Kubota, Reference Kubota2019; Zúñiga & Hamann, Reference Zúñiga and Hamann2006). Taking together all the evidence that we have gathered by now, the question on which factors may influence the reactivation of the HL in contexts of return remains largely unanswered. Even less is known about their relative language dominance and how it may change over time.

Factors affecting dominance changes in returnees

One crucial factor affecting the language competence of returnees is age; however, we have to distinguish between age of onset of acquisition (AoA) of the bilinguals’ languages and age of loss of continued input, which normally corresponds to the moment of return (age of return [AoRET]).

AoA of the SL has been shown to play a role in the development of bilingual language competence, but mainly at initial stages of early L2 development (Meisel, Reference Meisel, Haznedar and Gavruseva2008). Child HSs who start acquiring the SL later in childhood (e.g., at age 5) may diverge from monolingual or simultaneous bilingual children concerning the rate and route of L2 acquisition (Chondrogianni & Marinis, Reference Chondrogianni and Marinis2011), but HSs tend to catch up with their peers. In later stages of development, AoA effects are often no longer detectable in many linguistic domains (Schulz & Grimm, Reference Schulz and Grimm2019), at least in normally developing children. AoA effects seem to be leveled by schooling and intense exposure to the SL, among other factors (De Cat, Reference De Cat2020). Even immigrant children who are not born in the host country tend to become dominant in the SL (Oller et al., Reference Oller, Jarmulowicz, Pearson, Cobo-Lewis, Durgunoglu and Goldenberg2011), contrary to immigrants who start acquiring the L2 in adulthood (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Aaronson and Wu2002). Thus, in situations of return, it is not likely that AoA is a relevant predictor of attrition in returnees’ former SL. Flores (Reference Flores2020) effectively found no effect of AoA in a study on nominal morphology in returnees’ attrited language (German).

More important than AoA is the age at which returnees move to their homeland. Several studies demonstrated that the loss of continued exposure to the (prior) SL during childhood significantly impacts its retention, whereas the return in older ages leads to considerably less attrition effects (see Flores, Reference Flores, Schmid and Köpke2019, for an overview). Flores (Reference Flores2010, Reference Flores2020) argued that the bilinguals’ languages need time to stabilize in the speakers’ mind; an early return and consequent loss of exposure to the SL may interrupt mental stabilization of linguistic knowledge and, thus, affect the relative strength of bilinguals’ languages (i.e., their dominance).

Conversely, AoRET may also impact the HL. The Turkish returnees studied by Kaya-Soykan et al. (Reference Kaya-Soykan, Antonova-Unlu and Sagin-Simsek2020) revealed nontarget-like use of evidentiality markers in Turkish even a decade after their return. The authors hypothesized that the HL may never fully “reactivate” in all linguistic domains in post-puberty returnees (see also Antonova-Unlu et al., Reference Antonova-Unlu, Wei and Kaya-Soykan2021). A possible explanation is based on a maturational account: certain linguistic properties that are not acquired (or stabilized) in the HL will not be acquired (or fully stabilized) if the immersion in the HL environment happens after childhood, due to maturational constraints of language development. In fact, all mentioned studies on Turkish returnees tested speakers who returned as adolescents, making verification of this hypothesis impossible.

Even if AoRET is a relevant predictor of competence changes, it does not impact in isolation, that is, it is only predictive if accompanied by effective loss of continued exposure to the prior SL. Flores (Reference Flores2012) showed that only the returnees who lost daily contact with their former SL (German) effectively produced nontarget like object omissions in German. Inversely, participants who continued to use German on a daily basis within the family or/and for professional reasons were very (although not completely) immune to attrition effects. In fact, the reported cases of severe attrition of the former SL describe situations of extreme reduction of exposure. Thus, quantity (and type) of language exposure is a crucial variable in dominance changes, particularly concerning the language that is no longer the SL.

On the other hand, the HL becomes the language of environment. Therefore, contact increases drastically after the return. The relevant question that arises in this case is not how much contact the returnee now has with the HL (since it becomes the dominant SL), but how long it takes for this dominant contact to impact the returnees’ HL and, consequently, to lead to dominance changes. Thus, length of stay in the country of origin is a further relevant predictor of dominance changes, which needs to be investigated. So far, we know that the length of stay may have differential impacts on the HL in different linguistic domains (Daller, Reference Daller1999; Kaya-Soykan et al., Reference Kaya-Soykan, Antonova-Unlu and Sagin-Simsek2020). Naturally, the variables length of stay and quantity of contact are associated with other extralinguistic factors which may further impact processes of dominance change, for instance, literacy skills attained in both languages before return and language attitudes and ideologies (see Flores & Snape, Reference Flores, Snape, Montrul and Polinsky2021, for a discussion).

This study

Participants

The database includes responses from 97 adult participants (mean age: 37.4; SD: 10.1). Sixty-three participants are early bilingual speakers of German and Portuguese, that is, they acquired both languages in childhood through naturalistic exposure while living in Germany or in the German-speaking part of Switzerland as second-generation children from Portuguese migrant families. All early bilinguals acquired Portuguese from birth as HL and German, the SL, either simultaneously or as early L2 before the age of 10. Forty-two out of these 63 participants no longer live in the German-speaking society, having returned to Portugal in childhood, as teenagers or young adults. The remaining 21 participants still live in the German-speaking country, being typical HSs of Portuguese.

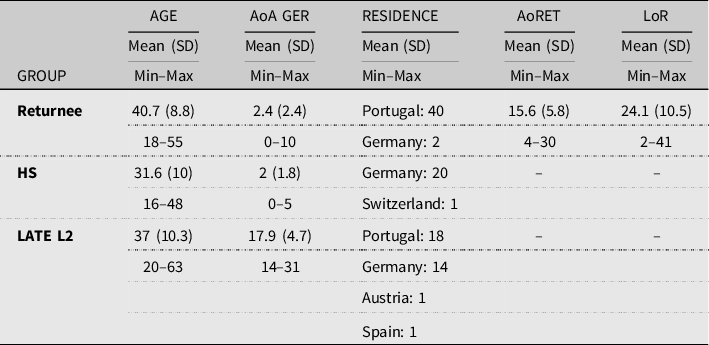

In addition, a group of 34 highly proficient late learners of German was recruited. They are L1 speakers of Portuguese who started acquiring German after the age of 14 through formal instruction and/or immersion in a German-speaking country (Germany, Switzerland, Austria). Table 1 gives an overview of the relevant background variables as a function of group (current age/AGE, AoA of German/AoA GER, country of residence at the moment of data collection/RESIDENCE). For the returnee group, the AoRET and the length of residence back in Portugal (LoR) are also indicated.

Table 1. Participants’ background variables per group

As shown in Table 1, the returnees are between 18 and 55 years old (mean: 40.7; SD: 8.8); they started acquiring German between birth and age 10 through immersion in a German-speaking environment (mean AoA of German: 2.4 years). Forty out of the 42 returnees live in Portugal (since their remigration); two of them recently returned to Germany (less than one year ago). The AoRET to Portugal ranges from 4 to 30 years (mean: 15.6; SD: 24.1). They have lived in Portugal for 2–41 years (mean LoR: 24.1; SD: 10.5).

The HSs are between 16 and 48 years old (mean: 31.6 years; SD: 10). As with their returnee counterparts, they grew up with exposure to Portuguese since birth, within their family. Some also started to acquire German from birth while others started to acquire the SL after entering kindergarten up to age 5 (mean AoA GER: 2 years; SD: 1.8). Twenty participants lived in Germany and one lived in Switzerland.

Finally, the late L2 learners of German (mean age: 37 years; SD: 10.3) grew up monolingual in Portugal with unique exposure to Portuguese. They started to acquire German between the ages of 14 and 31 through instruction and/or migration to Germany. All speakers have a strong bond to German, either because they studied it at school/university, lived or still live in a German-speaking country (16 out of 34) or/and use German at work.

Instruments and procedure

Data collection was conducted entirely online. Participants were contacted through personal connections. Participation requests were distributed to mailing lists and shared via social media. The instruments included a background questionnaire in Portuguese, and the German and the Portuguese versions of the DIALANG vocabulary test (Alderson, Reference Alderson2005), both presented in Google Forms. These instruments were part of a larger study, wherein participants also completed other tasks (e.g., a translation task in PCIBEX, see Sá-Leite et al., Reference Sá-Leite, Flores, Eira, Haro and Comesañasubmitted). All participants were informed about the general aims of this study and gave consent to participating. The study was approved by the Ethics Council of the University of Minho (CEICSH 120/2020).

Background questionnaire

The background questionnaire included 40 questions targeting current personal and professional information, such as age, place of residence (city/country), occupation, and degree of instruction. Participants were asked to answer questions concerning their linguistic background, that is, AoA of Portuguese, German, and other languages, country of birth, country of residence in childhood, age of (re)migration, and to estimate their current amount of contact with all the languages they knew, in percentage (the total being 100%). For quantification of relative exposure to Portuguese and German, we calculated the differential between the percentage of contact indicated for Portuguese and for German (and excluded the other languages, mainly English). Negative values indicate more current contact with Portuguese and positive values more contact with German (e.g., 50% Portuguese, 30% German, 20% English; dif = −20).

Participants further indicated their current dominant language (Portuguese or German or both) and their dominant language before (re)migration. Finally, they were asked to rate their proficiency in Portuguese, German, and in the other languages they knew, on a scale from 1 to 7 (from very low to very high) in speaking, listening, reading, and writing. For the quantification, we added the ratings for speaking and writing and obtained a total self-assessment score on a scale from 1 to 14 for both languages. We then computed the differential between both language scores to define a value for self-assessed relative proficiency. Again, negative values indicate higher self-estimated proficiency in Portuguese and positive values in German (e.g., Portuguese speaking: 7 + Portuguese writing: 6 = 13; German speaking: 5 + German writing: 5 = 10; dif: −3). Note that not all questions were applied to all speaker groups, for instance, HSs and late L2ers were only asked about their current dominance, since remigration did not apply to their situation. The questionnaire that we used can be accessed at https://osf.io/e47vz/?view_only=23563982b8984355a6d454282dc7ef36.

DIALANG vocabulary test in German and in Portuguese

The objective assessment of proficiency was conducted using the DIALANG vocabulary size placement tests (VSPTs) in version 1 for Portuguese and German.Footnote 1 Each versionFootnote 2 consists of a list of 75 words: 50 are real words in the evaluated language, and 25 are nonwords. Participants had to indicate whether or not each word is a real word in Portuguese/German, without being told how many nonwords are included (see Alderson, Reference Alderson, Fox, Wesche, Bayliss, Cheng, Turner and Doe2007, for a detailed description). The tests were performed in Google Forms with the add-on Quilgo, which allows a timer to be set and indicates if participants are focused on the task or not (i.e., whether they opened other browser tabs). Participants first completed the Portuguese and then the German version. They had a total of 7 min to complete the task. The test score was computed following the suggestion by Alderson (Reference Alderson2005), namely a simple total of words correctly identified as either real words or nonwords.Footnote 3 The maximum score for each language was, thus, 75 points.

Based on the DIALANG VSPT test scores, we computed the relative language proficiency as language dominance indices. Following Birdsong (Reference Birdsong, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016), we employed both the differential as well as the ratio method. The former method calculates between-language subtractive differentials by subtracting the scores of German from that of Portuguese. Again, negative values indicate higher proficiency in Portuguese and positive values in German (e.g., German: 64 − Portuguese: 74; dif: −10). Values close to zero indicate balanced performance. The ratio procedure computes between-language ratios by dividing the smaller of the two raw proficiency scores by the larger one, yielding a dominance index between 0 and 1 (e.g., German: 64: Portuguese: 74; ratio: 0.86). In this procedure, values near 1 indicate balanced performance and near 0 high imbalance, even though the direction of imbalance is not explicit in the ratio. We consider both scoring methods in the analysis.

Research questions and predictions

Our research questions and respective predictions are twofold. The first two questions focus on language dominance across the three bilingual groups included in the study: the returnees, who moved to their country of origin, HSs living in the migration context and late L2 learners of German. The groups differ concerning their AoA of German, their current relative amount of contact with German and Portuguese and their country of residence. Taking these differences into consideration, we formulate the following research questions and predictions:

-

Q1: Do the three groups of speakers differ with regard to their relative degree of language dominance, that is, can different degrees of language dominance be predicted by the variable group?

-

P1.1: Following common observations on heritage and second language development (Jia et al., Reference Jia, Aaronson and Wu2002; Montrul, Reference Montrul, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016), we expect HSs, who grew up and live in German-speaking environments, to be German-dominant and the late L2 learners, who grew up monolingual in Portugal and started acquiring German after age 14 (late L2), to be Portuguese-dominant.

-

P1.2: For the returnees the picture may be less clear. In terms of dominance, we expect them to be situated between the HSs and the late L2 groups, since a shift of dominance from German to Portuguese is to be assumed, on the basis of previous research on returnees (Flores, Reference Flores2010). The decrease of proficiency in German and an increase of proficiency in Portuguese may, in fact, cause higher degrees of balance, leading to the prediction that this group of bilinguals may be the most balanced one.

-

Q2: Is there a correlation between the variables “amount of contact with the two languages” and “language proficiency” measured with the DIALANG test, between “self-assessment of language proficiency”/“self-assessment of dominant language” and “language proficiency”?

-

P2.1: Prior research has suggested that self-assessment may be used to define language dominance (Dunn & Fox Tree, Reference Dunn and Fox Tree2009). Based on these findings, we predict significant positive correlations between the self-assessment differentials and the measuring of language proficiency using the DIALANG tests in all three groups.

-

P2.2: In addition, experience-based measurements have been shown to be correlated with language proficiency (Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018). Thus, we predict that the “amount of contact with the two languages,” as estimated by the participants, may also be correlated with the lexical knowledge differential. Moreover, we speculate that this correlation might be clearer in the late L2 group than in both HS groups, because the participants were asked to estimate the degree of language contact according to their use of Portuguese and German at the moment of data collection. This means that variation of language exposure over the HSs’ life span is not taken into account. Knowing that it is in particular the contact during childhood that modulates language development, the absence of these data may blur a potential correlation between amount of contact and language proficiency.

The third research question focused solely on the group of returnees. Aiming to understand which extralinguistic variables modulate language dominance and potential dominance shift in situations of return, we ask the following question:

-

Q3: Which extralinguistic variables (AoRET, AoA GER, LoR, Contact) predict the degree of language balance in the returnee group?

-

P3.1: Taking into account previous studies on returnees which have shown that the AoRET, associated with the amount of contact with the former SL, explains effects of language attrition (Flores, Reference Flores2010, Reference Flores2020), we predict that these variables are the most influential ones in explaining returnees’ degree of proficiency in German. If a decrease of German proficiency was motivated by an early AoRET, the LoR in Portugal would be less relevant in predicting the degree of proficiency in German. In other words, in cases of early return, changes in German proficiency occur right after moving to Portugal (within 18 months, as suggested by Flores, Reference Flores2015) and are not reinforced by longer LoR. Regarding AoA, if its influence on the development of the SL was mostly overcome at school age, as often demonstrated in the literature (Schulz & Grimm, Reference Schulz and Grimm2019), we speculate that AoA in German would not be a predictor of the DIALANG results either.

-

P3.2: Since the returnees immerse in the HL environment and start to have intense daily contact with Portuguese, we predict that a process of reactivation of the HL is triggered, which may have stagnated at some point during migration as outcome of reduced HL exposure (Montrul, Reference Montrul, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016). The process of reactivation will be mirrored in increasing proficiency in Portuguese, which will not be an abrupt process, but be prolonged over time. For this reason, we hypothesize that LoR in Portugal may be the most influential predictor of proficiency in Portuguese, that is, it will take time to increase proficiency in the HL. The longer the speaker lives in the Portuguese environment, the higher the proficiency in the HL. In this scenario, the role of AoRET is less clear. For German, which ceases to be present in the returnees’ daily life, the return brings an abrupt loss of contact; therefore, AoRET is predicted to be influential (see P3.1). For Portuguese, it brings an increase of exposure to a language that was already present in the speakers’ life. Therefore, AoRET may be less predictive for gaining proficiency in Portuguese than for losing it in German. As for the variable AoA GER, if we assume that AoA effects disappear in advanced childhood, including for the HL, it will not predict the returnees’ proficiency in adulthood. If, on the other hand, AoA effects are lasting, as suggested by Flores and Rato (Reference Flores and Rato2016) for HL pronunciation, it may also predict the level of proficiency as assessed by the Portuguese DIALANG test. Since the study by Flores and Rato (Reference Flores and Rato2016) focused solely on perceived accent in a reduced number of participants, more evidence on lasting effects of AoA of the SL on the HL is indeed required.

Results

Language dominance across different bilingual groups

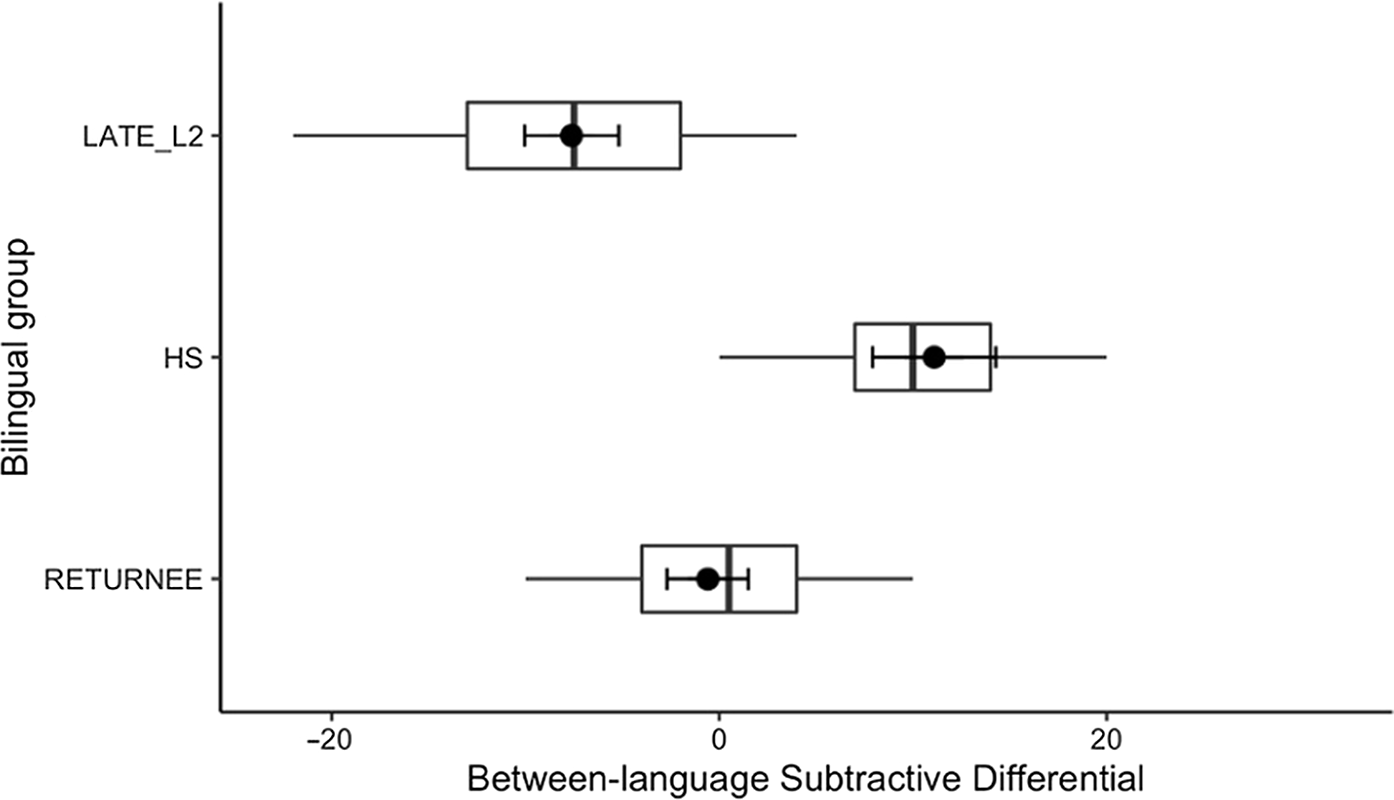

Regarding Q1, we start by reporting the descriptive statistics concerning DIALANG test scores and dominance indices calculated by the differential and ratio methods as a function of group (returnee, HS, late L2, see Table 2). Figure 1 plots subtraction-derived dominance indices by the three groups. The de-identified raw data and commented analysis scripts (in R Markdown) for all statistical models reported in this paper have been uploaded to the Open Science Framework. They can be accessed at https://osf.io/e47vz/?view_only=23563982b8984355a6d454282dc7ef36.

Table 2. Absolute and relative proficiency measurements per group (mean, minimum, maximum)

Figure 1. Language Dominance Indices as a Function of Participant Group Calculated by the Differential Method (Values Close to 0 Indicate Balanced Dominance, Negative Values for Dominance toward Portuguese, Positive Values for Dominance toward German; Error Bars Represent 95% CI).

In the returnee group, the absolute proficiency scores for Portuguese and German, assessed through the DIALANG vocabulary tests, are similar. This leads to a near-zero between-language subtractive differential, implying a high degree of language balance in the returnee group.

The HSs, who still live in Germany or Switzerland, scored less in the Portuguese test than in the German one. Their dominance in favor of German is instantiated by the positive between-language proficiency differential. A look at the minimum and maximum values obtained through the differential score further shows that no participant of this group is Portuguese-dominant (no negative scores).

In the late L2 group, as expected, the test score for Portuguese is higher than for German. The resulting negative differential indicates that the late L2ers are Portuguese-dominant. It is worth noting that some late L2 learners of German are nearly balanced (or even German-dominant), as instantiated by their above-zero differential (e.g., +4).

Apart from relying on the between-language differential, the difference pertaining to the language dominance as a function of participant group is also clearly demonstrated by the ratio-derived indices, visualized in Figure 2. The descriptive statistics, thus far, supports the P1.1 that the HS group is German-dominant, while the late L2 group is Portuguese-dominant.

Figure 2. Language Dominance Indices as a Function of Participant Group Calculated by the Ratio Method (0 Indicates Imbalance, 1 Indicates Perfect Balance; Error Bars Represent 95% CI).

To test whether the returnees are more balanced than the other groups, as stated in P1.2, a beta regression model was fitted in R (R core team, 2021), using the gamlss package (Rigby & Stasinopoulos, Reference Rigby and Stasinopoulos2005). The beta regression model is one-inflated because the range of our outcome variable, the between-language ratio, is (0, 1]. The model had Participant Group (three levels: returnee, HS, late L2) as the predictor (reference level: returnee). The beta regression confirms what is observed in Figure 2, namely, that the returnees are more balanced than the HSs (b = .78, CI = [0.43, 1.12], p < .001) and the late L2ers (b = .53, CI = [0.21, 0.85], p = .002).

Relationship between self-assessed/experience-based and performance-based measurements

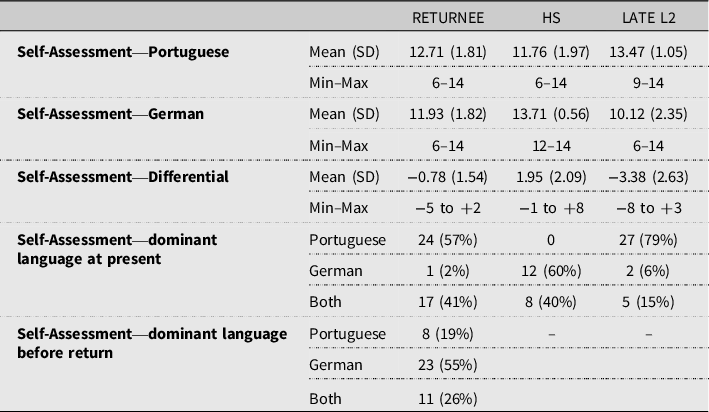

The second research question (Q2) is about whether the self-assessed and experience-based measurements are correlated with performance-derived indices of language dominance. The descriptive statistics of the self-reported proficiency and dominance is presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Self-reported proficiency and dominance per group (mean, minimum, maximum)

The returnees’ self-assessment differential lies close to 0, stemming from the fact that their self-rating for Portuguese nearly resembles that for German. The HSs evaluated their German to be better than their Portuguese, whereas the opposite is true for the late L2ers. Therefore, for all three groups, the between-language differentials calculated on the basis of self-reported proficiency follow the similar trend of proficiency differentials assessed through the DIALANG tests.

Regarding the self-reported dominant language, the majority of the returnees identified themselves as Portuguese-dominant (57%) or as balanced (41%). Only one participant considered herself to be German-dominant. The picture is different when indicating the dominant language before return with 55% pointing to German (26% indicated both languages). In the HS group no participant indicated to be Portuguese-dominant, with 60% pointing to German and 40% to both languages. Finally, the majority of the late L2ers considered themselves to be dominant in Portuguese (79%), 6% in German, and 15% to be balanced.

To explore the relationship between self-assessment and relative proficiency measured through the DIALANG differential, a set of bivariate correlational analyses were conducted as a function of participant group. The self-reported proficiency differentials correlated significantly with performance-based measurements for the returnee group (r = .72, p < .001), the HS group (r = .68, p < .001) and the late L2 group (r = .55, p < .001). Following prior research (Bedore et al., Reference Bedore, Peña, Summers, Boerger, Resendiz, Greene, Bohman and Gillam2012; Thordardottir, Reference Thordardottir2011; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018), we fitted a set of linear, quadratic, and cubic regression models to examine whether the relation between self-reported and performance-based measurements was better explained by nonlinear regression models than linear ones. The results of model comparison revealed that, for the correlation found in all three groups, there was no significant difference between the linear models and the nonlinear ones.

At a next step, several linear regression models were fitted to test whether self-reported dominance (Portuguese, German, or both) is a good predictor of DIALANG differential. Results of model comparison indicated a main effect of the self-reported dominant language for the three groups (returnees: F (−2, 41) = 6.15, p = .0048; HSs: F (−2, 20) = 4.2, p = .032; late L2ers: F (−2, 33) = 5.73, p = .0076). Therefore, P2.1 was borne out. There is a moderate-to-strong positive correlation between the bilinguals’ self-assessed and objective proficiency differentials. Moreover, the self-reported dominant language was identified as a significant predictor for DIALANG differentials. In line with other studies, our results show that, along with objective performance-based measurements, asking the participants to evaluate their proficiency may provide useful information on estimating language dominance.

Next, we probed the relation between experience-based and performance-based measurements. The descriptive statistics of the amount of contact is summarized in Table 4.

Table 4. Amount of contact with Portuguese and German as a function of participant group

As for the estimated amount of contact with Portuguese and German, the between-language differential shows that the returnees have very restricted contact with German. On the contrary, the HSs have frequent contact with German, whereas little or moderate contact with their HL Portuguese. For the late L2 group, the range is higher (−90 to +55), with a mean differential of −27.50 (and a very high SD of 43.82). This considerable variation is due to the fact that half of the L2ers currently live in German-speaking environments (see Table 1) and have more contact with German than the speakers living in Portugal.

Several bivariate correlational analyses were first conducted as a function of participant group to investigate the relationship between amount of language contact and DIALANG differential. The estimated amount of contact with German only correlated significantly with the DIALANG differential for the late L2 group (r = .5, p = .0028). The amount of contact with Portuguese, on the other hand, correlated significantly with the DIALANG score for the HS group (r = −.46, p = .034). Finally, the contact differential correlated with the DIALANG differential both for the HS group (r = .46, p = .038) and the late L2 group (r = .44, p = .01). No significant correlation between experience-based and performance-based measurements was found for the returnees.

Curve-fitting analyses were then conducted to determine whether the relation between experience-based and performance-based ways of measuring is better accounted for by nonlinear models, as observed in the literature (Bedore et al., Reference Bedore, Peña, Summers, Boerger, Resendiz, Greene, Bohman and Gillam2012; Thordardottir, Reference Thordardottir2011; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018). The results of model comparison, shown in Table 5, reveal that the relation between experienced-based and performance-based measurements obtained in the HS group is better modeled by nonlinear regressions. No difference between linear and nonlinear models is found when accounting for this relation in the late L2 group.

Table 5. Results of model comparison on the relationship between amount of language contact and DIALANG differential

*p < .05; **p < .01.

The P2.2, pointing to an association between performance-based and experience-based variables, was only partially confirmed, as evident by the mixed results: No correlation was found in the returnee group. In the HS group, the contact differential is significantly correlated with the proficiency differential; however, it is the contact with Portuguese (not with German) that is, indeed, (negatively) correlated with the DIALANG differential. Less contact with Portuguese leads to higher proficiency differential values (thus signaling German dominance).

Like in the HS group, a significant correlation between the contact and the proficiency differentials was observed in the late L2 group. In this case, it is the amount of contact with German that correlates significantly with language dominance index, indicating that the more contact the speakers have with their L2 German, the higher their differential value (the less Portuguese-dominant they are).

A detailed look at returnees

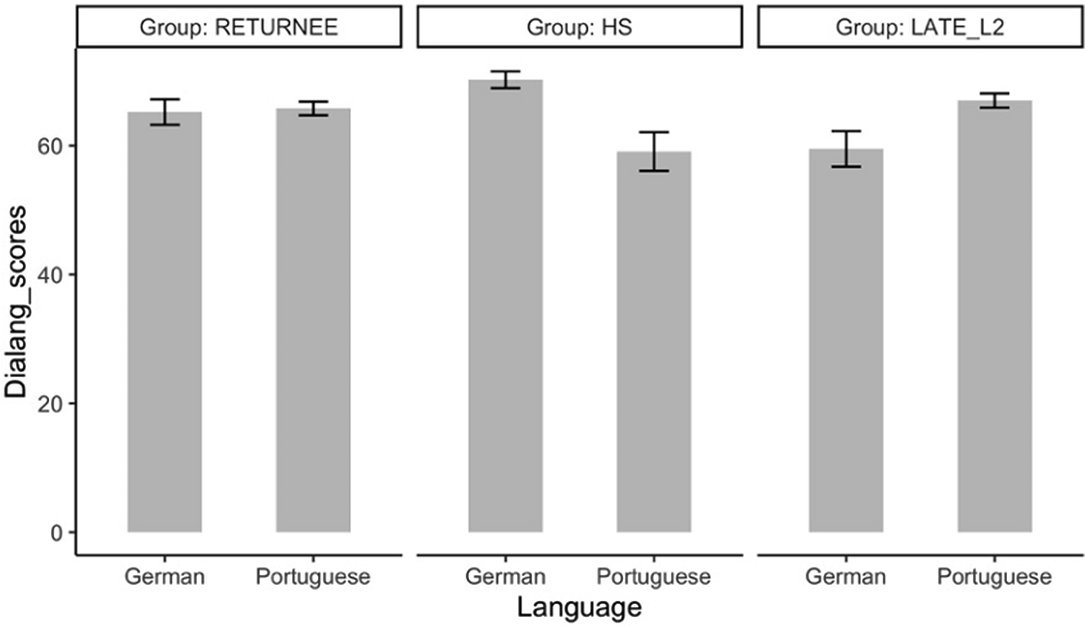

As confirmed in the section “Language dominance across different bilingual groups”, the returnees are more balanced, when compared to HSs and late L2ers. We reasoned that this group’s higher degree of language balance can be ascribed to a shift of dominance from German to Portuguese, namely a decrease of proficiency in German and an increase in Portuguese. This, indeed, seems to be the case, if we compare the absolute proficiency scores obtained by returnees with scores obtained by HSs (German-dominant) and by late L2ers (Portuguese-dominant), as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Raw Proficiency Scores as a Function of Participant Group (Error Bars Represent 95% CI).

To identify the predictive variables responsible for a decrease in German proficiency and an increase in Portuguese, two mixed logistic regression models were fitted on returnees’ responses in the DIALANG tests for German and Portuguese, respectively, using the package lme4 (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Mächler, Bolker and Walker2015).

In the model for German proficiency, the outcome variable was the accuracy in the DIALANG test for German.Footnote 4 The model had “AoA Ger,” “AoRET,” “LoR in Portugal,” and “Contact with German” as predictors. It also included random intercepts by participant and by test item. A main effect of “AoRET” was identified (b = .11, CI = [0.038, 0.17], p = .0022), indicating that bilinguals that returned to Portugal at an early age have lower German proficiency than their peers that moved back later in life.

Comparably, the model for Portuguese proficiency also had accuracy as an outcome variable. However, only the “AoA Ger,” “AoRET,” and “LoR in Portugal” were included in the model as predictors. Since the returnees live in a Portuguese-dominant environment, “Contact with Portuguese” is very high for all participants, thus there is no theoretical motivation to include this variable in the model. Random intercepts by participant and by test item were likewise included in the mixed model. This time, a main effect of “LoR in Portugal” was found (b = .02, CI = [0.0029, 0.038], p = .023), which means that lengthier stay in Portugal predicts an increase in returnees’ Portuguese proficiency. For the two models reported above, variance inflation factors (VIFs) indicated no problem with (multi)collinearityFootnote 5 and visual inspections of residual plots revealed no obvious violations of the normality and homogeneity of variance assumptions.

Discussion and concluding remarks

Findings from this study contribute to the emerging body of research concerning language dominance in diverse groups of bilingual speakers, with a particular focus on adult HSs who experienced a considerable change of input conditions due to remigration.

Q1 aimed at understanding whether different contexts of language acquisition and subsequent changes of the dominant language environment lead to differences in language balance across groups. The comparison between the three groups confirms that this is indeed the case.

The HSs living in the German-speaking environment have an unbalanced language dominance. They are more dominant in their SL German than in their HL Portuguese (see Figures 1 and 2). This finding is in line with the literature on HL development, which assumes a switch to the dominant SL as soon as child HSs enter the SL’s school system (Benmamoun et al., Reference Benmamoun, Montrul and Polinsky2013; Kupisch et al., Reference Kupisch, Kolb, Rodina and Urek2021; Rothman, Reference Rothman2009). Our results indicate that the effect of this switch lasts over the HSs’ lifetime if they maintain their residence in the migration setting.

As predicted, late L2ers, on the other hand, are mostly Portuguese-dominant. These speakers acquired German after age 14, but they are highly fluent in German because they use or used it on a daily basis, either at university, at work or within the family. As shown in Table 2, the amount of contact with German estimated at the moment of data collection varies across speakers. This may underlie the wide range of their language dominance indices. We return to this issue. In any case, their dominance in Portuguese is not surprising, given that it is their L1 and they acquired German as an L2 later in life.

Regarding the returnees, we predicted that this group would be the most balanced, as a result of a decrease of proficiency in German and an increase in Portuguese. The dominance differential and ratio show that this is indeed the case. The returnees’ average differential is close to zero, showing that they have similar proficiency in both languages (consequently, the ratio is close to 1). A look at Table 2 and Figure 3 indicates that the mean score of proficiency for both languages is situated between the scores obtained in the other groups. The score for Portuguese is 65.79 (compared to 59.10 for HSs and 67.00 for late L2ers) and for German 65.21 (compared to 70.24 for HSs and 59.50 for late L2ers). The beta regression confirms that the returnees are more balanced than the HSs (b = .78, CI = [0.43, 1.12], p < .001) and the late L2ers (b = .53, CI = [0.21, 0.85], p = .002).

What do these results say about language dominance in different bilingual populations? First, we should bear in mind that language dominance is not categorical, but should be interpreted as a continuum (Birdsong, Reference Birdsong, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016; Treffers-Daller, Reference Treffers-Daller, Silva-Corvalán and Treffers Daller2016). In this sense, our analysis focused on the degree of language balance, rather than on a direct comparison of the proficiency scores between the three groups. A comparison of the raw proficiency scores in German and in Portuguese obtained by the three groups indicates that remigration gives rise to dominance shift. HSs who grow up and remain in the migration setting are strongly imbalanced in favor of the SL (German); however, most of the returnees became balanced bilinguals, suggesting that moving to the HL environment levels this imbalance. We will see that the AoRET plays an important role in the process of dominance shift. Obtaining balanced language dominance may be a natural outcome of the return, as long as remigration does not occur in early age.

Going a step further, Q2 asked whether the language dominance indices, based on proficiency scores obtained in the DIALANG tests, correlate with self-reported proficiency and with experience-based measurements. Our results show that, for all three bilingual groups, the DIALANG differential not only has a moderate-to-strong positive correlation with the self-assessed proficiency differential, but can also be predicted from the categorical self-identified language dominance (Portuguese, German, or both). This confirms that self-reported scores indeed provide some insight into participants’ language dominance, which was already acknowledged in early field work on bilingual populations (Hakuta & D’Andrea, Reference Hakuta and D’Andrea1992). Although self-reports should not replace objective performance-based measures, they may provide complementary evidence on estimation of participants’ language dominance.

For the returnees, and in line with the DIALANG differential, the self-assessed proficiency differential revealed high language balance. Furthermore, many participants indicated a dominance shift when asked about their current and prior dominant language. Informally, many returnees indicated that there are tasks, such as mental calculation, saying the alphabet, making a shopping list, which they no longer perform in German, taking this as a sign of having switched dominance to Portuguese. Still, the vast majority indicated feeling very comfortable when speaking German and feeling a strong affective bond to their childhood language.

As for the self-estimated current amount of contact with Portuguese and German, our results corroborate previous studies, showing that experiential quantifications can be taken as proxy for language dominance (Bedore et al., Reference Bedore, Peña, Summers, Boerger, Resendiz, Greene, Bohman and Gillam2012; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018); however, the current findings suggest that this is only true for the HS and the late L2er groups. Moreover, for participants of these two groups, it is the estimated amount of contact with the nondominant language that has an impact on their language proficiency: more contact with the HL Portuguese predicts a decrease in proficiency differentials (closer to zero, which means higher balance) for the HSs; more contact with German implies more balanced proficiency of the late L2ers.

It has been shown that the relationship between experience-based and performance-based measurements of dominance is generally best accounted for with a nonlinear model (Bedore et al., Reference Bedore, Peña, Summers, Boerger, Resendiz, Greene, Bohman and Gillam2012). Unsworth and colleagues (Reference Unsworth, Chondrogianni and Skarabela2018) further reported in their study that the additional variance captured by nonlinear models, in comparison to linear ones, is quite limited (between 1% and 8%) and can even be neglected in certain cases (<1%). Our results are largely in line with these previous studies. The relationship between relative experience and relative proficiency in the HS group was indeed better modeled by nonlinear models, while in the late L2 group no difference between linear and nonlinear models were found; however, our results also show that, in the returnee group, no correlation between experiential and performance-based measurements seems to exist. Thus, the estimation of current amount of contact should be used with caution, since it is not a valid measurement for all bilingual groups. In the next paragraph, we speculate on what underlies the difference between returnees and HSs.

While living in the migration context, the HSs’ contact with the HL Portuguese is not only more reduced, but also displays considerable between-subject variation. Research has shown that it is the amount of contact with the minority language (not the SL) that explains the degree of language (im)balance in HSs (Correia & Flores, Reference Correia and Flores2017; Rodina et al., Reference Rodina, Kupisch, Meir, Mitrofanova, Urek and Westergaard2020). Our results confirm that experience-based measurements may be taken as proxy for language dominance in minority language populations, who do not experience drastic changes. Indeed, no significant change of the input conditions of HSs is to be expected after enrolment in school. Therefore, the amount of contact with the HL estimated at the moment of data collection is assumed not to have drastically changed (although there is variation and there may be cases of drastic input changes even without a change of environment). Thus, it may be taken as estimation over time, differently from the returnee group. Of course, a deeper understanding of the factors that actually contribute to “amount of contact” and that modulate language dominance cumulatively over the HSs’ lifetime requires more fine-grained analyses and advanced quantitative methods (see De Cat, Reference De Cat2020).

The case of the returnees is different in terms of experience-based measurements, which leads us to Q3. In the returnee group, the amount of contact with German (in Portugal) varies considerably across speakers; however, the estimation is a snapshot of the moment of data collection. In general, contact with German is very restricted in this group (as shown by the high negative contact differential: −44.22 (34.33), displayed in Table 4), but we know from the HS group that the inverse situation was at play before return. Before remigration, returnees had more contact with German than with Portuguese. Thus, it is not the estimated current amount of contact, but rather the shift from the German-dominant to the Portuguese-dominant environment that modulates their language dominance. But what exactly explains the current language balance?

We may conclude that returnees become more proficient in their HL Portuguese, while they lose proficiency in their German, which together contribute to a high degree of language balance. Regarding the increase of proficiency in Portuguese, our data suggest that LoR in Portugal is responsible. Through the return to the country of origin and subsequent increasing exposure to the HL, a process of reactivation of HL development, which may have stagnated, was initiated. The process of reactivating the HL needs time, that is, higher LoR in Portugal predicts higher proficiency scores in Portuguese. We know that L1 development does not end abruptly in childhood. It may further develop in adolescence and beyond (see Braine et al., Reference Braine, Brooks, Cowan, Samuels and Tamis-LeMonda1993; Jia et al., Reference Jia, Aaronson and Wu2002). Our results indicate that this may be in fact the case for the HL Portuguese. Eventually, Portuguese ceases to be an HL for the returnees, if we follow the common definition that an HL is a family language that is not the dominant language of the environment (Rothman, Reference Rothman2009).

Furthermore, our findings indicate that it is the AoRET that explains returnees’ proficiency levels in German, rather than LoR. In other words, the earlier the returnees moved to Portugal, the more significant the decrease of proficiency in German. This is in line with prior research on returnees (Flores, Reference Flores2010, Reference Flores2015, Reference Flores2020), indicating that changes to the speakers’ competence (i.e., attrition effects in syntax and morphology) occur right after return in returnees who move to their (parents’) homeland in childhood. When the return occurs at adolescence (or adulthood), almost no effects of attrition (of decreasing competence) are observed. This study shows that the same holds true for lexical competence.

Taken together, what explains language balance in the returnees reported on in the current study is, in fact, the increasing proficiency in Portuguese as a result of an increasing LoR in Portugal. This increase is, however, not accompanied by a steady loss of proficiency in German (recall that LoR is not predictive for German), but rather by an abrupt decrease in returnees with an early AoRET.

In addition, results also revealed an absence of AoA effects. Even though the absence of an effect should be interpreted with caution, this may show that AoA effects in early bilinguals are leveled during the course of their lives and do not predict language balance in adulthood. The effect of AoA is only seen in the comparison between early (returnees and HSs) and late bilinguals in the sense that the late L2ers of German are, in general, more Portuguese-dominant than the early bilingual HSs.

In sum, this study demonstrated that different groups of bilingual speakers of Portuguese and German show different degrees of language balance and that different background variables predict these differences. Still, more empirical research on the processes of attrition of SL and reactivation of HL competences in the context of return is needed.

There are two methodological limitations in this study. First, bilinguals’ language proficiency was only assessed by vocabulary tests. Future studies may consider combining different measures (e.g., vocabulary test, oral fluency, and foreign-accent rating) to depict a more precise and comprehensive picture of language proficiency. Second, the observed limited predictive power of experience-based measures can arguably be ascribed to the fact that they only reflect the current amount of language contact. The effect of cumulative amount of contact (e.g., Tao et al., Reference Tao, Cai and Gollan2021) still needs further exploration.

Conflict of interests

The author(s) declare none.