Article contents

A new species of trypanosome, Trypanosoma desterrensis sp. n., isolated from South American bats

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 October 2003

Abstract

Trypanosomes isolated from South American bats include the human pathogen Trypanosoma cruzi. Other Trypanosoma spp. that have been found exclusively in bats are not well characterized at the DNA sequence level and we have therefore used the SL RNA gene to differentiate and characterize kinetoplastids isolated from bats in South America. A Trypanosoma sp. isolated from bats in southern Brazil was compared with the geographically diverse isolates T. cruzi marinkellei, T. vespertilionis, and T. dionisii. Analysis of the SL RNA gene repeats revealed size and sequence variability among these bat trypanosomes. We have developed hybridization probes to separate these bat isolates and have analysed the DNA sequence data to estimate their relatedness. A new species, Trypanosoma desterrensis sp. n., is proposed, for which a 5S rRNA gene was also found within the SL RNA repeat.

Keywords

- Type

- Research Article

- Information

- Copyright

- © 2003 Cambridge University Press

INTRODUCTION

Several bat species around the world are infected by trypanosomes from the section Stercoraria. While instances of infection with the subgenus T. (Herpetosoma) are rare, at least 9 distinct species of Trypanosoma from Europe, the Americas, and Australia, thought to be specific to bats, have been assigned to the subgenus T. (Schizotrypanum), and 8 species from Europe, South America and Africa to the subgenus Megatrypanum (Molyneux, 1991). Studies on T. (Schizotrypanum) species isolated from bats are of particular interest due to their morphological similarity with T. cruzi, the aetiological agent of Chagas disease in humans (Molyneux, 1991; Hoare, 1972; Marinkelle, 1976; Bower & Woo, 1981; Steindel et al. 1998). Other trypanosomes such as T. evansi and T. equiperdum are veterinary pathogens which can also be found infecting bats (Molyneux, 1991). These trypanosome species are transmitted among mammals via the bite of vampire bats or mechanical vectors (Molyneux, 1991).

Methods used to differentiate and characterize members of the T. (Schizotrypanum) subgenus isolated from bats include isoenzyme electrophoresis (Baker et al. 1978; Teixeira et al. 1993), DNA buoyant density (Baker et al. 1978), schizodeme analysis (Teixeira et al. 1993), monoclonal antibodies (Petry, Baltz & Schottelius, 1986), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (Steindel et al. 1998) and experimental infections (Molyneux, 1991; Steindel et al. 1998).

The nuclear multicopy spliced leader (SL) RNA gene, also known as the mini-exon gene, has been used as a genetic marker to distinguish and/or characterize different protozoan species within the suborder Trypanosomatina, such as Trypanosoma sp. (Tibayrenc et al. 1993; Murthy, Dibbern & Campbell, 1992; Grisard, Campbell & Romanha, 1999; Souto et al. 1996; Fernandes et al. 1998; Sturm et al. 1998), Crithidia sp. (Fernandes et al. 1997), Phytomonas sp. (Sturm, Fernandes & Campbell, 1995; Dollet, Sturm & Campbell, 2001), Leishmania sp. (Fernandes et al. 1994; Grisard et al. 2000), the suborder Bodonina (Campbell, 1992; Santana et al. 2001) and the Euglenozoa (Maslov et al. 1993). The SL RNA genes are present at 200–300 copies per cell and arranged as tandem repeats. The gene consists of a conserved exon, usually 39 nt long, that is trans-spliced to the 5′ end of all nuclear mRNA, an intron, between 50 and 100 nt, of variable sequence but resulting in a transcript with conserved secondary structure; and a variable non-transcribed intergenic spacer (Murthy et al. 1992). In some cases the SL RNA gene may be associated with a 5S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene (Murthy et al. 1992; Grisard et al. 1999).

In this study we have used the SL RNA gene as a molecular marker to examine the relationships among trypanosomes isolated from different host bats. Using the complete SL RNA gene repeat (exon, intron and the non-transcribed intergenic spacer region) for phylogenetic analysis, we report the identification of a third major group of bat-specific trypanosomes from southern Brazil. The third group's SL RNA gene repeat contains a 5S ribosomal RNA gene, distinguishing it from the other bat groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites, strains and DNA preparation

Trypanosoma spp. strains M-504 (type strain) and M-511 were isolated from Eptesicus furinalis bats in Florianópolis Island, Santa Catarina State, Brazil (Steindel et al. 1998) and are deposited at the cryobank of the Laboratório de Protozoologia, Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina (UFSC), Brazil. A T. vespertilionis strain, originally isolated from Pipistrellus pipistrellus in England (Baker et al. 1978), was obtained from Fundação Oswaldo Cruz culture collection (Fiocruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and kindly donated by S. Murta and A. Romanha. T. c. marinkellei (M1909 strain and clone 9-3), which were isolated in Brazil (Teixeira et al. 1993), were obtained as DNA samples from C. Barnabé (IRD, France) and A. Romanha (Fiocruz, Brazil). Genomic DNA was extracted as previously described (Steindel et al. 1998).

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays and DNA analysis

PCR amplification of the SL RNA gene was performed as described previously (Grisard et al. 1999) using oligonucleotides ME-L (5′-CCCGA ATTCT GTACT ATATT GGT-3′) and ME-R (5′-CAGTT TCTGT ACTTT ATTGA GGAAA CAGCT-3′). Amplification products were electrophoresed in 1% agarose gel containing TAE buffer, visualized through ethidium bromide staining, purified and subsequently cloned using either TA or TOPO-TA Cloning Kits® (Invitrogen, La Jolla, USA). PCR amplification products resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis were denatured and blotted onto nylon membranes (Micron Separations, Westborough, USA) by standard techniques (Fernandes et al. 1998) and hybridized in BLOTTO (Johnson et al. 1984). Filters were washed in 2×SSC/0·1% SDS at 55 °C. Oligonucleotide probes were: M, 5′-CCGGA AGCTT CGCGT AC-3′; Tcm, 5′-GCCGC GTAAT TGCGG TT-3′; Tvp, 5′-CGACC GTTCG GACGC AT-3′.

The DNA sequence of the cloned inserts was obtained from both strands using the Sequenase® Kit (Amersham, Uppsala, Sweden) and aligned by PILEUP and GAP routines of the University of Wisconsin GCG package. Secondary structures were made by eye in combination with the mFOLD program (Zuker, Mathews & Turner, 1999) available on the internet (http://bioinfo.math.rpi.edu/~mfold/rna/). After alignment by ClustalX software (Thompson et al. 1997), the complete SL repeat (exon, intron and non-transcribed intergenic regions) were analysed by bootstrapped (1000 replicates) neighbour-joining and maximum parsimony methods using MEGA v. 1.02® software (Kumar, Tamura & Nei, 1993) in order to estimate the relatedness among the bat trypanosomes.

RESULTS

Amplification and DNA sequence of SL RNA gene repeats

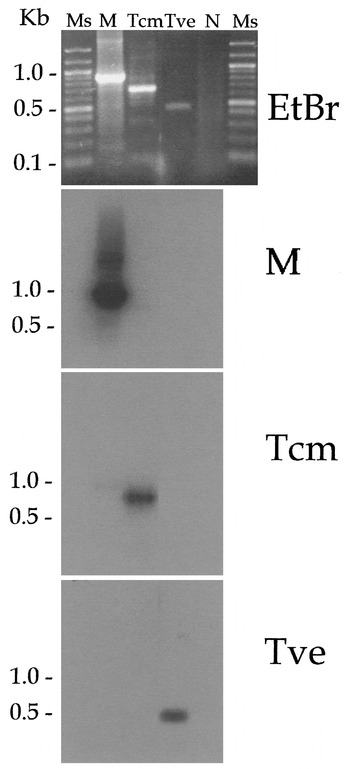

In order to define the variety of trypanosome species found in bat populations better, we have examined the SL RNA gene repeats from 10 isolates of South American bats. The amplification products were resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis and the major band from each isolate was cloned and sequenced (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. PCR amplification of the SL RNA gene repeat with oligonucleotides ME-L and ME-R. Amplification products were resolved by 1% TAE agarose gel electrophoresis, visualized by ethidium bromide staining (EtBr). Ms, molecular size marker, 100 bp DNA Ladder® (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA); M, strain M-504; Tcm, T. c. marinkellei (strain M1909); Tve, T. vespertilionis; N, no DNA negative control. A bi-directional DNA blot of the gel was hydridized with oligonucleotide probes for M-504 (M), T. c. marinkellei (Tcm), and T. vespertilionis (Tve).

The size of the amplification products varied between 0·5 kb for T. vespertilionis and 0·85 kb for the 7 Trypanosoma spp. isolates from the bat colony in southern Brazil (Steindel et al. 1998). Of the amplified products of the 7 Trypanosoma sp. isolates, strain M-504 was randomly chosen as a representative for further analysis, since all samples were isolated from the same bat species and the sequencing of the SL RNA of two strains showed no differences (data not shown). Two samples of T. c. marinkellei, designated M1909 and clone 9-3, were amplified. The major products from these amplifications were cloned, and single representatives were sequenced (GenBank accession numbers AF124146, AF116568, AF116570, AF116564).

All products reported here contained the expected SL RNA gene repeat structure, including the SL RNA exon, intron and non-transcribed spacer region. Although we cannot be certain about each nucleotide position found under the amplification primers (nts 21–42), the variable AT-rich nucleotides between positions 11 and 20 (Sturm et al. 2001) found in the bat trypanosomes in this study were identical to each other (data not shown) and to those of T. cruzi (Murthy et al. 1992), T. rangeli (Murthy et al. 1992; Grisard et al. 1999) and to T. dionisii (Gibson et al. 2000), which was isolated from a bat in Europe.

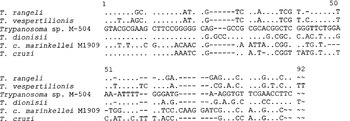

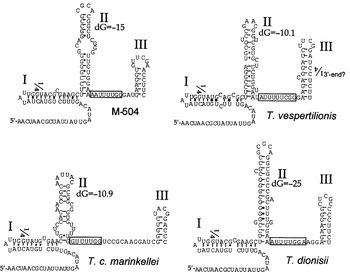

In contrast, the intron sequences showed some variation, as illustrated by PILEUP analysis (Fig. 2), which includes T. cruzi and T. rangeli introns for comparison. The introns of 2 isolates from T. c. marinkellei were identical with the exception of 1 additional nucleotide at position 98 relative to the start of transcription. Despite the differences in their primary sequences, all of the intron sequences could be folded into the standard Form II structure for the SL RNA (LeCuyer & Crothers, 1993), as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 2. Alignment of bat trypanosome SL RNA gene sequences. Parasites and/or strains are indicated on the left; dots indicate identity; dashes indicate gaps introduced to maximize the alignment of the repeats. The SL sequences from Trypanosoma cruzi (GenBank accession number X62674) and T. rangeli (GenBank accession number X62675) were included for comparison.

Fig. 3. The SL RNAs from trypanosomes isolated from bats can be folded into the standard Form II secondary structure. Structures were derived for SL RNAs from M-504, T. vespertilionis, T. c. marinkellei isolate M1909, and T. dionisii (GenBank accession number AJ250744). These structures typically include 3 stem-loops (labeled I, II and III) and a single-stranded region between stem-loops II and III that contains the Sm-binding site motif (AUUUUGG or some variation). The predicted transcribed regions of the SL RNA genes were defined as beginning at the conserved AACUAACG sequence at the 5′ end, and ending in the downstream poly T tract. U residues from the T tract are included in these structures if indicated by the base-pairing of stem-loop III. The dG values are indicated for stem-loop II, and were calculated using the mFOLD program.

The non-transcribed spacer regions, which we have defined as starting at the beginning of the T tract that signals SL RNA transcription termination (Sturm, Yu & Campbell, 1999) and are interrupted by the presence of the 5S rRNA in T. rangeli (Murthy et al. 1992; Grisard et al. 1999), were useful for inter-specific characterization, despite their intraspecific sequence variability (Grisard et al. 1999; Fernandes et al. 1998; Sturm et al. 1998). The 2 strains of T. c. marinkellei showed 10% variability with 18 gaps in GAP analysis using values of 20 and 1 for gap weight and gap length penalties, respectively (data not shown). The M-504 spacer region contained a 5S ribosomal RNA gene (positions 452–563) in the same transcriptional orientation as the SL RNA gene.

Hybridization analysis

To distinguish the different trypanosomes of bats, we designed oligonucleotide probes based on either the intron or non-transcribed spacer regions of the respective SL RNA genes. DNA blot analysis (Fig. 1) demonstrated the specificity of each probe for the major PCR product derived from the homologous strain. Thus we report diagnostic reagents that are specific for 3 groups of bat trypanosomes.

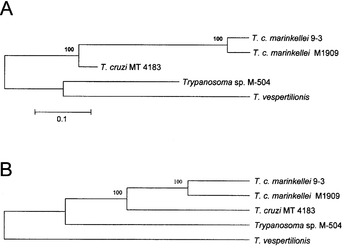

Phylogenetic analysis

To determine the genetic relatedness among the bat trypanosomes we performed a phylogenetic analysis using the complete SL RNA gene sequences (Fig. 4). Since T. dionisii SL-RNA sequence at the GenBank database is incomplete, this parasite was not included in phylogenetic analysis. The same tree topology was observed for 3 analysis methods (distance, neighbour-joining or maximum parsimony). The neighbour-joining analysis clearly revealed the presence of 2 distinct branches. One branch supported by high bootstrap values, also shown in bootstrap consensus tree, was formed by T. cruzi and both T. c. marinkellei strains used in this study. The second branch contained T. vespertilionis and the Santa Catarina isolate M-504. The latter result is consistent with the hybridization analysis (Fig. 1) and the presence of a 5S rRNA gene in M-504, which distinguished the 2 isolates.

Fig. 4. (A) Phylogram based on neighbour-joining analysis of bat trypanosome species and Trypanosoma cruzi SL RNA gene (GenBank accession number X62674) sequences. (B) Consensus tree obtained by Maximum Parsimony analysis with the ‘branch and bound method’ of the same bat trypanosome sequences. Both trees were derived from 1.000 bootstrap replicates and values shown above the nodes.

DISCUSSION

Since trypanosomes isolated from bats have a widespread distribution throughout the American continent (Molyneux, 1991; Hoare, 1972; Marinkelle, 1976; Bower et al. 1981), the use of both biological and molecular methods to distinguish between indigenous bat species and trypanosomes of medical relevance is of great importance.

The herein described trypanosomes were isolated from a single colony of E. furinalis bats (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) and were unable to infect triatomines and Swiss mice under experimental conditions (Steindel et al. 1998). There are no available data on the prevalence or transmission of these trypanosomes, since no possible vectors have been identified; however, due to the gregarious behaviour of bats direct transmission should be considered (Steindel et al. 1998).

Former studies on these trypanosomes revealed morphological characteristics of the subgenus T. (Schizotrypanum). A basket-like kinetoplast in trypomastigote forms and reservosomes (type I and II) were observed in epimastigote forms using both light and electron microscopy (Figueiredo, Steindel & Soares, 1994). Moreover, these trypanosomes were revealed to be distinct from T. cruzi, T. rangeli, T. hastatus and T. vespertilionis in RAPD, indirect immunofluorescence and isoenzyme assays (Steindel et al. 1998).

Here we report an assay using the SL-RNA gene that has allowed us to differentiate among bat trypanosome species, and to indicate the relatedness between these trypanosomatids. Amplification of the SL RNA gene from other bat-isolated strains revealed distinct product sizes allowing comparison with the recent isolates from Brazil (M-504) (Steindel et al. 1998). M-504 showed low similarity with the reference isolates. In light of the biological differences (Steindel et al. 1998) and the new DNA sequence, the trypanosomes from E. furinalis most likely represent a new species.

Various features of the SL RNA gene structure can be used to examine the relatedness of trypanosomes found in bats. The 39-nucleotide exon portion of the SL gene is well conserved at positions 1–10 and 21–39 among all kinetoplastids. In contrast, the AT-rich region at positions 11–20 shows variability (Santana et al. 2001). The sequence of the exon positions 11–20 in the bat trypanosomes studied here is identical to that of T. cruzi, T. rangeli, and a variety of related Trypanosoma species (Gibson et al. 2000) consistent with their relatedness in the American Trypanosoma clade (Stevens et al. 1999 b). While non-transcribed spacer differences were used to distinguish between T. cruzi and T. rangeli SL RNA genes (Murthy et al. 1992), DNA sequence variability in the intron region has enabled the design of probes that are specific to distinguish M-504, T. cruzi marinkellei and T. vespertillionis. It is noteworthy that these SL RNA gene markers can distinguish other members of the American Trypanosoma clade. While possessing almost identical exon and intron sequences, T. conorhini can be distinguished from T. rangeli and T. leeuwenhoeki on the basis of the non-transcribed spacer (LeCuyer et al. 1993). Although each intron is distinct, the intron alignment shows striking similarities between T. vespertilionis and M-504, and between T. c. marinkellei M1909 and a sylvatic representative of T. cruzi (Souto et al. 1996). These 3 groups may reflect the biological origins of the current species.

Phylogenetic analysis carried out using the whole SL repeat revealed 2 robust branches with bootstrap support of 100%. One branch is formed by both T. c. marinkellei strains, which were isolated from the same bat species in Brazil. The unsupported group contained T. vespertilionis and M-504 strains isolated in Brazil, which are clearly distinct on the basis of non-transcribed spacer sequences and the presence of the 5S rRNA gene in the same array as the SL RNA gene in M-504. M-504 possessed the 5S rRNA gene as observed for T. rangeli (Murthy et al. 1992) and other kinetoplastids such as Herpetomonas sp. (Aksoy, 1992), Bodo sp. (Campbell, 1992) and Trypanoplasma sp. (Maslov et al. 1993). Although not an informative phylogenetic marker for long-range evolutionary studies of Trypanosoma spp. (Gibson et al. 2000), the SL RNA gene repeat is useful for both intra- and inter-specific characterization (Murthy et al. 1992; Grisard et al. 1999; Stevens et al. 1999) and short-range studies within closely related species (Grisard et al. 1999; Sturm et al. 1995). Moreover, the trees generated from SL sequences of bat trypanosomes are consistent with trees based on SSU ribosomal RNA sequences (Stevens & Gibson, 1999; Stevens et al. 1999 a, b), which show distinct branches for T. vespertillionis, T. cruzi marinkellei and other bat trypanosomes.

The trypanosome strain M-504 isolated from E. furinalis in southern Brazil is different from previously characterized South American bat trypanosomes. This result is consistent with previous biological and molecular characterization (Steindel et al. 1998). In all analyses, the bat-specific isolates were similar to each other and distinct from other trypanosome species found in bats and other vertebrates including T. rangeli and human pathogen T. cruzi (Steindel et al. 1998). Because the bat trypanosomes from Southern Brazil represented by M-504 are distinct with respect to biological, biochemical and molecular markers, we propose that they constitute a new species named Trypanosoma desterrensis sp. n. in honor of the Florianópolis Island, formerly known as Nossa Senhora do Desterro Island.

We thank S. L. Althoff for the identification of the bats; S. M. F. Murta, A. J. Romanha, C. Barnabé and M. Tibayrenc who provided DNA of some strains used in this study and A. M. R. Davila, M. Steindel and C. J. Carvalho-Pinto for helpful comments. E. C. Grisard was a CNPq and CAPES (Brazilian Government Agencies) grantee.

References

REFERENCES

Fig. 1. PCR amplification of the SL RNA gene repeat with oligonucleotides ME-L and ME-R. Amplification products were resolved by 1% TAE agarose gel electrophoresis, visualized by ethidium bromide staining (EtBr). Ms, molecular size marker, 100 bp DNA Ladder® (Promega, Madison, Wisconsin, USA); M, strain M-504; Tcm, T. c. marinkellei (strain M1909); Tve, T. vespertilionis; N, no DNA negative control. A bi-directional DNA blot of the gel was hydridized with oligonucleotide probes for M-504 (M), T. c. marinkellei (Tcm), and T. vespertilionis (Tve).

Fig. 2. Alignment of bat trypanosome SL RNA gene sequences. Parasites and/or strains are indicated on the left; dots indicate identity; dashes indicate gaps introduced to maximize the alignment of the repeats. The SL sequences from Trypanosoma cruzi (GenBank accession number X62674) and T. rangeli (GenBank accession number X62675) were included for comparison.

Fig. 3. The SL RNAs from trypanosomes isolated from bats can be folded into the standard Form II secondary structure. Structures were derived for SL RNAs from M-504, T. vespertilionis, T. c. marinkellei isolate M1909, and T. dionisii (GenBank accession number AJ250744). These structures typically include 3 stem-loops (labeled I, II and III) and a single-stranded region between stem-loops II and III that contains the Sm-binding site motif (AUUUUGG or some variation). The predicted transcribed regions of the SL RNA genes were defined as beginning at the conserved AACUAACG sequence at the 5′ end, and ending in the downstream poly T tract. U residues from the T tract are included in these structures if indicated by the base-pairing of stem-loop III. The dG values are indicated for stem-loop II, and were calculated using the mFOLD program.

Fig. 4. (A) Phylogram based on neighbour-joining analysis of bat trypanosome species and Trypanosoma cruzi SL RNA gene (GenBank accession number X62674) sequences. (B) Consensus tree obtained by Maximum Parsimony analysis with the ‘branch and bound method’ of the same bat trypanosome sequences. Both trees were derived from 1.000 bootstrap replicates and values shown above the nodes.

- 21

- Cited by