In July 1867, Portugal became one of the first European countries to legally recognize cooperatives as special-purpose entities, thus distinct from other nonprofit organizations and business structures.Footnote 1 Upon first consideration the decision may seem odd. At that time, only the United Kingdom, Prussia, and France had similar legislation in place.Footnote 2 All of them were rapidly growing industrial economies with flourishing and expanding cooperative sectors. Portugal, by contrast, was a peasant country and counted only one organization with cooperative features.Footnote 3

A closer look into the issue, however, reveals that the oddity is only apparent. Unlike its contemporary counterparts, the Portuguese law on cooperatives was not conceived as a response to grassroots changes in the socioeconomic environment, but rather as an attempt to shape this environment in a way that fitted the best interests of the ruling elite. In the view of the country’s authorities, cooperatives would contribute to improve the well-being of the working class; this, in turn, would prevent the emergence of a class cleavage between labor and capital, thus preserving the stability of the liberal economic and political order.

From the perspective of labor policy, the distinct, original rationale underlying the passing of the Portuguese legislation raises two fundamental questions. The first concerns the formulation process. How did the Portuguese authorities come up with the idea of using cooperatives to avert the adverse socioeconomic and political effects of industrialization? The second question regards the impact of the policy measure. To what extent did one of the most backward countries in Europe succeed in promoting the development of an organization that was typical of most advanced capitalist societies?

This study seeks to shed light on both issues by combining the methods of historical research with the insights of contemporary public policy analysis. To achieve this purpose, the discussion has been organized as follows. Section 2 sets the theoretical framework and provides a brief overview of the primary and secondary historical sources employed in the research. Section 3 traces the evolution of the socioeconomic and political factors that converged to create a window of opportunity for policy formulation. Section 4 focuses on the phase of policy elaboration, emphasizing the role and the rationale of key political actors. Section 5 examines the impact of the policy from the perspective of the involved stakeholders —the ruling elite and the emergent working class. Section 6 concludes the paper with a discussion and an indication on future work.

Methodology and Sources

Determining the reasons behind the passing of the 1867 Cooperative Societies Act requires a theory of policymaking. Contemporary public policy scholars have developed a variety of approaches, each one of which relies on different assumptions and/or emphasizes different aspects of the policy process.Footnote 4 Considering the nature of the problem at hand, this study adopts John Kingdon’s multiple-streams framework.Footnote 5 This approach has the advantage of assuming that solutions and problems are generated independently of each other; it does not deny a degree of rationality on the part of the policymakers (in the sense that they take decisions based on reasoned judgment), but admits that the policy process is permeated by political interests and therefore prone to ambiguity and manipulation.Footnote 6

In its classic formulation, the multiple-streams approach assumes that the setting of the policy agenda is shaped by three independent streams of activity—problems, politics, and policies. The problem stream refers to the process by which a given social phenomenon comes to be defined as social problem deserving public attention. As Kingdon observes, this process is deeply subjective, since it presupposes the perception of “mismatch between the observed conditions and one’s conception of an ideal state.”Footnote 7 The policy stream concerns the expertise and technical knowledge that allow the development of solutions; it involves a relatively loose community of policy experts “who have a shared concern and engage in working out alternatives to policy problems of a specific policy field.”Footnote 8 Finally, the political stream deals with the struggle for power; it refers to the interests and views of the agents that compete in the political arena, and to their influence on the definition of problems and on the search for solutions.

According to Kingdon’s approach, a window of opportunity for policy formulation opens at the precise moment in which these three streams of activity intersect, that is, when a public problem is matched by a technically and politically feasible solution. The model also assigns a pivotal role to the so-called policy entrepreneurs. These are individuals who champion a particular solution and who, at the proper time and in the proper context, are ready to invest their own resources (reputation, time, etc.) in order to couple the three streams together.Footnote 9

Assessing the effects of policy intervention, by contrast, presupposes some understanding about the scope and limits of policy evaluation. The scarcity of available sources and the multi-stakeholder and multidimensional nature of the policy outcomes compromise the accuracy and validity of any objective assessment attempt. With this caveat in mind, this study sets the more modest goal of exploring the implications of the policy measure from the perspective of its main stakeholders. Taking a constructivist approach, it assumes that the worth of a policy program is a social construction shaped by the perceptions, opinions, beliefs, and norms of the people who have a stake in the program.Footnote 10 The emphasis is consequently placed on determining whether the policy fulfilled the expectations of its promoters—Portugal’s ruling elite—as well as on how it was received by the people it was meant to benefit, Portugal’s nascent working class.Footnote 11

The time frame of the study is from the late 1840s to the late 1880s. The analysis of the policy process roughly spans from the aftermath of the 1848 European liberal revolutions—a period that saw the first articulations of economic inequality as a social problem in Portugal—until the passing of the law on cooperatives, in June 1867. The evaluation of the policy impact, for its part, covers the twenty-one-year period during which the law was in force, that is, from its enactment in July 1867 until the moment it was overridden by a reform of the Commercial Code, in June 1888.Footnote 12

Both primary and secondary sources are employed in the study. Previous historical accounts of socioeconomic and political events and conditions in Portugal and Europe are used to explain (1) the factors that led the Portuguese ruling elite to gradually perceive inequality as a problem deserving public attention; (2) those that triggered the political decision to intervene; and (3) those that allowed cooperatives to be perceived as an effective and legitimate policy tool. Legislative records and policy reports are used to examine the process that led to the coupling of the three streams of activity (problems, politics, policies). Finally, statistics produced by the Portuguese government and opinion and news articles collected from the working-class press are used to assess the impact of the policy intervention.

Three Parallel Streams of Activity

The Problem Stream

The analysis of the policy process must logically begin with an examination of the factors that influenced the public perception of inequality as a social problem deserving state intervention. This, in turn, leads to focus the attention on the actors who were involved in the policy arena. At the time the law on cooperatives was implemented, the Portuguese working class was small and still lacked an autonomous and self-governing representative structure capable of articulating a common political and economic agenda.Footnote 13 The country was ruled by a Constitutional Monarchy based on limited suffrage and rigged elections that guaranteed continued power for the incumbent elite.Footnote 14 While the majority of the population was disenfranchised, the institutions of the state were populated by a bourgeoisie of senior military officers, university professors, and administrative and judicial officials, as well as by a new class of landowners who benefited from the selling of disentailed church land.Footnote 15

Heavily influenced by the ideas of French Enlightenment and Freemasonry, the members of the ruling elite had a liberal conception of the state and society, grounded on the respect of the natural right to life, liberty, and property.Footnote 16 Socioeconomic and political disparities originating from privileges of blood were generally rejected, but those originating from individual effort, merit, and skill were accepted as legitimate.Footnote 17 With specific regard to the legitimacy of inequality between capital and labor, opinions differed considerably. Although the boundaries between existing political parties were fuzzy and fluid—more based on local contingencies and pragmatic calculations than on programmatic considerationsFootnote 18—at least two tendencies can be loosely distinguished: one that encouraged workers to become more active in self-improvement, and the other that remained largely indifferent to the workers’ plight. Following an approach embraced by other students of Portuguese nineteenth-century politics, the former will be henceforth referred to as “left-wing” or “progressive” and the latter as “right-wing” or “conservative.”Footnote 19

An embryonic version of the progressive stance emerged in the early 1840s, a few years after the consolidation of liberal Constitutional Monarchy.Footnote 20 Concerned about the possible harmful social effects of the abolition of guilds and other institutions of the Ancien Régime, Silvestre Pinheiro Ferreira, a statesman who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the early years of the liberal revolution, advocated the creation of associations of artisans and workers. Though he did not espouse the cause of radical social change, Pinheiro Ferreira believed that mutual aid and corporatelike organizations were necessary to provide the lower classes with some protection against the social harms that would inevitably come with unleashed capitalist expansion.Footnote 21

By the early 1850s, this kind of moderate liberal progressive thinking began to give over to more radical stances. Substantially influenced by the wave of liberal revolutions that swept Europe in 1848,Footnote 22 a younger generation of liberal activists and thinkers suggested that an improvement in the living conditions of the working classes would require a profound transformation of the existing political and economic structures. In his Estudos sobre a Reforma em Portugal (Studies on Reform in Portugal), José Félix Henriques Nogueira, an influential figure of the emergent republican thought, envisioned the creation of cooperativelike organizations (local associations) which, acting in coordination with local-level corporate institutions, would form the pillars of a more just and efficient, decentralized political and economic system.Footnote 23 From the pages of the weekly journal Ecco dos Operários, Francisco Maria de Sousa Brandão, a radical progressive who would later become one of the founders of the Portuguese Socialist Party, encouraged workers to gather and organize in free associations, which would not only provide mutual aid and protection for its members, but would also engage in production and other economic activities.Footnote 24 These associations, in Sousa Brandão’s view, would operate in complete autonomy from the state authorities,Footnote 25 eventually becoming the main production engine of a noncapitalist—thus more equal—free-market industrial society.Footnote 26

The Political Stream

The radical stance of the progressive liberals was soon moderated by a structural transformation of the country’s political environment. After nearly a decade and a half of power struggles between various liberal factions (which were marked by a succession of armed insurrections, civil wars, and institutional crises), in 1851 a military coup opened a new era of consensus and political compromise.Footnote 27 Under the motto of “reconcile and regenerate,” the members of the ruling elite overcame their major ideological divides and converged on a pragmatic policy agenda aimed at promoting faster economic growth.

In order to create a national market and consolidate commercial ties with the largest consumer centers in Europe, the development strategy involved the engagement of the state in the provision of basic infrastructures, such as roads, railways, port facilities, and telegraph lines.Footnote 28 The promoters of this program expected that increased commerce would spur industrial development, unleashing a virtuous circle of economic prosperity and social improvement. At the same time, however, they feared that rapid industrialization might also increase the size and power of the working class, sowing the seeds of a social conflict that could threaten the stability of the political regime. To prevent such an undesirable outcome, and to ensure that economic development would not endanger the supreme value of freedom and the rights of property ownership, the elite devised a parallel strategy aimed at controlling the expectations and demands of the emergent labor movement.

In what has been characterized as a “triumph of the ‘center’ over the ‘extremes,’” the most progressive members of the liberal elite abdicated their commitment to the autonomy of the workers’ organizations.Footnote 29 In 1852, Sousa Brandão and other radical liberals joined the vanguard of the labor movement to found the Center for the Promotion of the Betterment of Laboring Classes (CPMCL). According to its bylaws, written by Sousa Brandão himself, the CPMCL would promote the dissemination of elementary and technical education, the foundation of asylums for the disabled, and the creation of new workers’ associations.Footnote 30 The nature and scope of these associations was very different from the nature and scope of the associations for which Sousa Brandão had advocated in the pages of the Ecco dos Operários, just a few years earlier. The focus on production was replaced by a focus on mutual aid, and the quest for autonomy was abandoned for the sake of political stability. Indeed, the decree that approved the CPMCL’s bylaws established that the government could, whenever deemed necessary, appoint agents to supervise the operation of the workers’ associations, as well as to declare them dissolved in case they were not pursuing the purposes for which they had been created.Footnote 31 As some contemporary observers have rightly noted, the CPMCL functioned as a de facto organ of the state, taking initiatives that were less aimed at empowering the working class than they were at containing the activism of its most literate and politicized members.Footnote 32

For more than a decade, this mechanism of informal control, complemented by a few repressive measures, which included a ban on strikes and the requirement of governmental authorization to establish associations of more than twenty people, achieved its intended purposes. Through the 1850s and early 1860s, strikes were rare, and when they did occur, they were invariably defensive and, more often than not, unsuccessful.Footnote 33 By the mid-1860s, however, the political and economic developments of most advanced nations began to reveal the shortcomings of the paternalistic, repressive strategy. In 1864, the formation of the International Workingmen’s Association (IWA) marked the beginning of a new phase in the class struggle between the capitalist bourgeoisie and the industrial proletariat. In the organization’s inaugural address, Marx emphasized the relationship between “political privileges” and the “perpetuation of [the bourgeoisie’s] economic monopolies,” encouraging workers “to conquer political power” as a means of economic and social emancipation.Footnote 34 The revolutionary tone of Marx’s discourse resonated among a group of young Portuguese workers, who would soon begin to put into question the goals and mission of the CPMCL.

Perceiving that coercive measures and philanthropic action had become insufficient to appease the growing demands of the country’s emergent working class, the various ideological currents of the Portuguese ruling elite began to converge on the need to change the approach to the labor question. As a first step in that direction, in 1865 the CPMCL convened the representatives of more than seventy mutual-aid associations from around the country to a conference in Lisbon. The First Portuguese Social Congress, as the conference was called, assessed the activity developed by mutual-aid societies (particularly in their relation to the working classes) and discussed strategies aimed at increasing the workers’ share of the benefits produced by industrial capitalism. In line with this goal, the participants to the meeting elaborated a two-point document, asking the government to pass legislation to facilitate the creation of new mutual-aid societies, and recommending the nomination of a commission to study and propose concrete actions “conducive to social improvements.”Footnote 35

The Policy Stream

By the time the Portuguese elite began searching ways to promote the economic empowerment of the working class, the liberal vanguards of some of the most advanced European nations were taking the first steps to regulate and promote the operation of cooperatives. In 1852, the British Parliament passed the Industrial Provident and Societies Act, which freed these organizations from the constraints of unlimited liability.Footnote 36 Amended a few years later to grant cooperatives a number of tax cuts and fiscal benefits,Footnote 37 this legislation set a precedent that was quickly followed by other rapidly industrializing countries. In 1863, Hermann Schulze-Delitzsch, a prominent politician and advocate of credit cooperatives, engaged in a seven-year-long struggle to convince the members of the Prussian Parliament to pass enabling regulations.Footnote 38 At around the same time, a group of prominent French liberals, including Auguste Casimir-Périer, Léon Say, and Léon Walras, embarked on a propaganda campaign to promote the virtues of the cooperative model among the country’s rapidly growing working population. Following the publication of a number of specialized journals, pamphlets, and brochures, in 1864 they submitted a legislative proposal to the State Council, which served as the basis of a Commercial Code reform that, in July 1867, granted cooperatives a specific corporate status.Footnote 39

The decision of the liberal governing elites to support the development of the cooperative sector was the result of two separate but converging processes. The first was the approximation of the cooperative model to the dictates of free-market industrial capitalism. Developed in the late eighteenth century as a pragmatic response to the social problems posed by incipient industrialization, cooperatives were subsequently embraced by socialist intellectuals and activists who aimed at subverting the capitalist mode of production.Footnote 40 This political tint, together with a disappointing record of failed social experiments, lent support to the idea that cooperatives were inefficient and incompatible with the logics of the market. In the 1840s, however, the introduction of a series of operational innovations, which included the payment of a fixed interest on capital and the distribution of profits in proportion to the members’ trade, turned cooperatives into a commercial success and contributed to debunk the myth of inefficiency among the champions of capitalism.Footnote 41

The second process drawing elites' attention toward cooperatives was the emergence of social policy as a distinct sphere of government intervention. Until the early nineteenth century, initiatives aimed at alleviation of poverty and other social ills were mostly carried out by charitable religious organizations and philanthropists. With the consolidation of the national states and the rapid rise of industrialization, these responsibilities were increasingly assumed by national governments. Aware of the fact that cooperatives could improve the well-being of the lower classes without burdening state coffers, the governing liberal elites of the core European countries became interested in the model and began to develop frameworks to support its development.

Coupling the Streams Together

By the mid-1860s, the political, problem, and policy streams had all come close to the intersecting point. Progressives and conservatives had consolidated a rotative political system anchored in a free-market, industrial capitalist ideology. The conclusions of the Social Congress had laid the foundations of a broad-based consensus about the need to reduce inequality, and cooperatives had cemented their reputation as market-based instruments of social protection. The final, necessary condition for policy action (i.e., the appearance of a policy entrepreneur capable of coupling the streams together), was met in July 1866, when João de Andrade Corvo, a progressive liberal who opposed both unrestrained free-market capitalism and excessive state interventionism,Footnote 42 was appointed Minister of Public Works, Commerce, and Industry, a key cabinet position during the Regeneration period.

After a few months in office, Minister Andrade Corvo took the recommendations of the 1865 Social Congress and appointed two commissions of academics, intellectuals, and association activists—one based in Lisbon and the other in Porto—to study and propose measures conducive to social improvements. The decree that convened both commissions was preceded by a brief report, in which Andrade Corvo expressed his desire to establish organizations with goals that went beyond the boundaries of mutual aid, engaging in activities such as production, consumption, and credit.Footnote 43

A window of opportunity to materialize the minister’s idea opened up in February 1867, when the Parliament began to discuss a bill simplifying procedures for registering commercial (capitalist) companies. Framing cooperatives as a type of business especially suited to the needs of poverty-stricken workers, Andrade Corvo exhorted the Chamber of Deputies in the following terms: “At a time when we are trying to establish general rules for the operation of capitalist companies … it would be a serious fault, a lacuna, all the more to deplore as it concerns the interests of the working people who aspire to improve their economic and moral status, not to lay down the legal basis for the establishment of cooperative societies.”Footnote 44 Although he did not make any explicit reference to his intellectual sources, the theoretical arguments and the statistics used to support his bill indicate that Andrade Corvo was familiar with the writings of French liberal advocates of the cooperative model. Following this line of thinking, the minister articulated his proposal around two conceptual pillars, namely, the ability of the cooperative to operate within a free-market environment (legitimacy), and its superiority vis-à-vis alternative solutions to economic inequality (effectiveness).

The Arguments of the Bill’s Proposer

Andrade Corvo carefully crafted his argument to ensure that cooperatives would appear as a legitimate tool in the eyes of the pro-capitalist liberal ruling elite. Having stressed that they would operate “in perfect harmony with the laws of the economy,” he went on to set explicit limits to the scope of state intervention: “It is not for the State to protect [the co-operatives], but only to lay down general rules that guide their first steps and secure the interests of those who join or contract with them, leaving wide scope to individual initiative and personal freedom.”Footnote 45 Conceiving cooperatives as autonomous entities, however, did not obscure the fact that they might not be able to withstand competition from the more economically powerful capitalist companies. In order to make up for competitive disadvantages, the bill included two sets of supportive measures. The first set reproduced the provisions contained in the British Industrial and Provident Societies Act (amended in 1862), exempting cooperatives from payment of registration fees, stamp duties, and taxes on profits.Footnote 46 The second set of provisions was instead original to Andrade Corvo’s proposal. Grounded on the assumption that poor schooling and lack of managerial skills would likely hamper the workers' ability to create and run successful business organizations, the Portuguese bill (i) mandated the government to elaborate model bylaws, and (ii) introduced the figure of “honorary members,” subsequently defined as “enlightened persons external to the cooperative, but who are nevertheless generously willing to assist the workers their endeavor.”Footnote 47

In order to convince the Parliament that cooperatives were effective instruments of social protection, Andrade Corvo used two different arguments. On the one hand, he pointed to the merits and successful examples of cooperatives in most advanced industrial nations, supporting his assertions with up-to-date statistics extracted from the journal Le Travail, edited by Léon Walras and Léon Say.Footnote 48 On the other hand, he highlighted the comparative advantages of cooperatives versus other types of self-help organizations. In the explanatory statement that accompanied his proposal, Andrade Corvo stressed that consumer and housing cooperatives were superior to mutual-aid societies (sociedades de socorros mutuos) because they not only provided a “safeguard against misery and abandonment in distressing hours” but also allowed for expenditure savings that fostered the economic status of their members.Footnote 49 In a similar vein, he argued that credit cooperatives were more autonomous and self-sufficient than saving banks (caixas económicas) because they were managed by their own members, with little or no intervention from state officials.Footnote 50

Quite interestingly, Andrade Corvo’s optimistic view of housing, consumer, and credit cooperatives contrasted with his skepticism about production cooperatives. Taking up an argument made by contemporary French cooperative advocates,Footnote 51 he wrote:

It is not so easy, nor is it so secure, without being impossible, to organize collective work units by the application of the cooperative principle… . Production societies depend upon the continuous action of managers, of people who can firmly run the factory or the workshop; they need a manager who concentrates all decision-making authority, … and such authority can only be given by the confidence that his fellow members have, not only in his moral qualities, but also in his faculties, in his aptitude for the job. Production cooperatives must reconcile equality with subordination. There lies the main difficulty.Footnote 52

The Reaction of the Parliament

The bill on cooperatives entered the Chamber of Deputies on February 22, 1867. Just about two months later, on April 23, the Committee on Commerce and the Arts and the Committee on Civil Law produced a joint document recommending its approval without amendments. Notably, the committees’ report—read in the Chamber on June 7, 1867—devoted the bulk of its attention to the problem of inequality, indicating it as the fundamental reason for promoting cooperatives. The argument for state intervention was built upon three related assumptions, the first of which was that the development of industrial capitalism would lead to massive economic growth, and that such growth would enhance the quality of life for all sectors of society: “The progress in economic science and in the industrial arts … multiply commodities and pleasures… . If the general wealth increases, the way of life of all social classes changes for the better, and the welfare of the poor improves.”Footnote 53

A second related assumption was that the balance of power in capital-labor relations was overwhelmingly tilted in favor of the former: “The tools and the processes that characterize modern industry require the concentration of manpower in workshops, as well as the prevalence, or at least the powerful intervention of capital. In this relationship between capital and labor, the entrepreneur and the simple worker fight with unequal weapons.”Footnote 54

With the benefit of hindsight, the committees’ report finally acknowledged that industrialization and economic inequality would eventually lead to social unrest: As emerges from the following quote, inequality was deemed unacceptable not because of its moral implications per se, but because of its potentially detrimental consequences for the stability of the liberal socioeconomic and political order: “The strikes and the workers’ seditious demonstrations that are taking place in large production centers and in manufacturing countries are warnings of forthcoming storms, which the statesmen, the righteous minds, the friends of peace and freedom, and the ultimate guarantors of property rights, are determined to eradicate. It is our duty to prevent this evil by contributing to the moral and material improvement of the working classes.”Footnote 55

Having explained the instrumental rationale for addressing inequality, the committees’ report went on to reinforce the legitimacy of cooperatives as intervention tools. Unlike the craft-guilds that regulated the work of artisans and apprentices in the pre-liberal era, cooperatives were organized on a voluntary basis; they did not “annihilate the individual, absorbing him in a despotic community,” but were based on the principle of self-determination and therefore in line with the fundamental liberal ideal of personal freedom.Footnote 56 Unlike socialist solutions, however, cooperatives did not assume the existence of “an inexorable antagonism between labor and capital”; they could adapt perfectly well to the logics of free-market competition, allowing workers to become entrepreneurs and thus to have a better share of the benefits of capitalist development.Footnote 57

A Late Reflection on the Cooperative’s Moral” Benefits

Approved in general terms and in each of its twenty-two articles, in a matter of days the bill reached the Chamber of Peers. In a very concise joint report, the Committee on Legislation and Agriculture and the Committee on Commerce and the Arts highlighted the “public significance” of the proposal and lauded its consistency with “the just or (the) liberal theory” and with “the practices of the most enlightened governments.”Footnote 58 With almost no discussion, in mid-June 1867 the bill was approved by the Peers and two weeks later it was enacted by King Luís I.

As per law regulations, between December 1867 and May 1872 the government published model bylaws for consumer, housing, and credit cooperatives.Footnote 59 These models were accompanied by reports that highlighted the multiple social benefits of the cooperative and explained its basic operational principles. Almost as an afterthought, these documents introduced two rationales for the promotion of cooperatives that had not been previously considered by the Portuguese lawmakers. One closely corresponds to Robert Putnam’s contemporary notion of social capital.Footnote 60 According to the drafter of the statutes for credit cooperatives, the relation of mutual dependence upon which the cooperative was based, translated into a “greater and more intimate interpersonal interactions,” which in turn contributed “the strengthening of bonds of fraternity and [to the development] of benevolent feelings.”Footnote 61 The other argument pointed to the purported moralizing power of private property. According to the drafter of the model bylaws for housing cooperatives, the ownership of a house would “strengthen [the worker’s] dignity, obliterate madly tendencies towards impossible social organizations, and reinforce family ties.”Footnote 62

An Assessment of the Policy Outcomes

Any attempt to assess the impact of institutions on economic outcomes is bound to be hampered by methodological problems. The decision to set up a new organization can be influenced by myriad factors that go well beyond the existence of a favorable regulatory framework. At the same time, the implementation of new legislation can have multiple and unforeseen consequences that are difficult to identify and measure. With this caveat in mind, this section looks at the outcomes of the Cooperative Societies Act in relation to the expectations of its proponents, and provides a brief account of its reception among the vanguard of the emergent (but still largely unorganized) working class.

The Expectations of the Ruling Elite

In the view of the ruling elite, the law on cooperatives would achieve a series of interrelated goals: it would encourage the formation of cooperatives, which in turn would improve the well-being of the lower classes, ultimately reducing the gap in income and wealth and therefore the risks of social upheaval and conflict. Figure 1 shows the number of cooperatives established in Portugal between 1858 and 1887. When the law was implemented, in July 1867, the country counted only one organization with cooperative features.Footnote 63 Over the following two decades, at least another ninety-three were formed, most of them dedicated to the provision of small credit and the sale of foodstuffs.Footnote 64 Although it is not possible to determine how many of these cooperatives were founded as a direct result of the government’s policy, the statistics plotted in Figure 1 suggest that the existence of a favorable legal framework had a positive impact on the sector.

Fig. 1. Cooperatives established in Portugal, by year of foundation and type, 1858–1887

Notes: The Associação Fraternal dos Fabricantes de Tecidos e Artes Correlativas —originally established in 1858—adapted its bylaws pursuant the 1867 Cooperative Societies Act in 1874; "na" refers to cooperatives for which the year of foundation could not be clearly identified.

Sources: Own elaboration based on Annuário estatístico do Reino de Portugal, 1875 (Lisboa, 1877); Costa Goodolphim, A Associação, 138-143; Costa Goodolphim, A Previdência, 37-70; Ministério da Fazenda, Annuário estatístico de Portugal, 1892 (Lisboa, 1899); Ministério das Obras Públicas, Commércio e Indústria, Sociedades Cooperativas Fundadas na Conformidade da Lei de 2 de Julho de 1867 (Lisboa, 1883); Ministério das Obras Públicas, Commércio e Indústria, Annuário estatístico de Portugal, 1886 (Lisboa, 1890); O Pensamento Social, issues n. 1 (February, 1872) through n. 55 (October, 4, 1873); O Protesto: Periodico Socialista, issues n. 52 (August 1876) through n. 341 (February, 26, 1882); O Protesto Operário: órgão do Partido Operário Socialista, issues n. 1 (March, 5, 1882) through n. 348 (December, 30, 1888).

A key question that arises at this point is whether the growing number of cooperatives actually led to an improvement in the well-being of the working class. The scanty available data indicate that most cooperatives were short-lived. According to Costa Goodolphim, only thirty were still in operation by the late 1880s.Footnote 65 Anecdotal evidence suggests that they suffered from mismanagement and capital shortages, as well as from the hostility of shopkeepers and small producers, who saw them as direct threats to their established businesses.Footnote 66

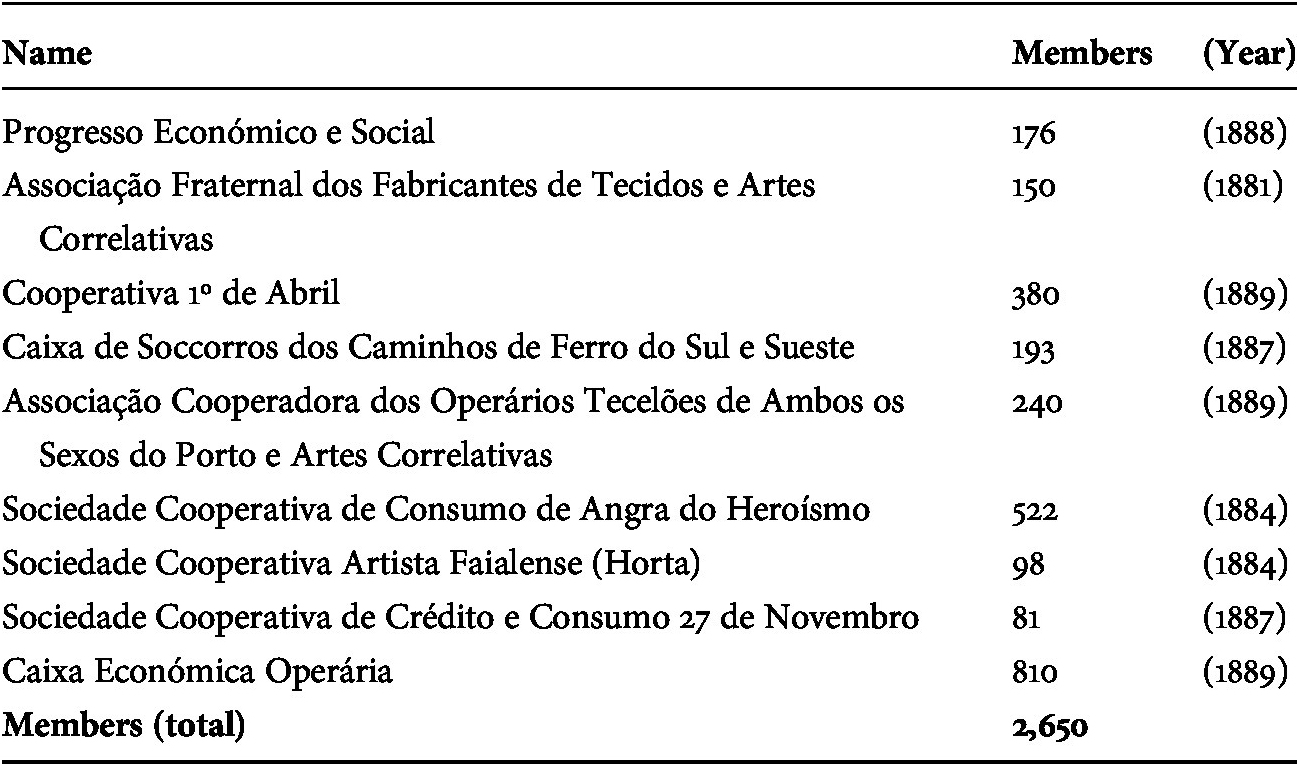

Table 1 shows data on membership for ten of the thirty cooperatives that were active in the late 1880s. The most conservative estimates suggest that, by that time, Portugal had a population of around 90,000 factory workers.Footnote 67 Hence, even if the 2,650 cooperative members reported in Table 1 are extrapolated under the most optimistic assumptions, one must conclude that only a small portion of the country’s labor force was actually engaged in some kind of cooperative endeavor.Footnote 68 Data on wages are not more encouraging. The few available statistics suggest that the gap between small struggling cooperatives and large and prosperous investor-owned firms could be notably large, in some cases reaching as much as 300 percent.Footnote 69 Even the most prosperous cooperatives, such as the Cooperativa Indústria Social—founded in Lisbon in 1872 with the assistance of Sousa Brandão—paid salaries that were slightly lower than those of comparable capitalist firms.Footnote 70

Table 1. Membership of a sample of cooperatives operating in the late 1880s

Source: Author’s elaboration based on Costa Goodolphim, A Previdência, 37–70.

The Reaction of the Working Class

The reaction of the working class seems to have been substantially shaped by the fluid political circumstances of the early 1870s. As some historians have noted, this period marked the end of a nearly two-decade-long collaborative relationship between the ruling elite and the leaders of the still-unorganized but increasingly politicized Portuguese working class.Footnote 71 Inspired by the events of the Paris Commune, in 1872 a group of socialist workers made a vain attempt to adapt the bylaws of the CPMCL to the goals of the IWA. Shortly after they split from the organization and formed the Worker’s Brotherhood Association —an entity that functioned as the local branch of the IWA and later became one of the founding pillars of the Portuguese Socialist Party.Footnote 72

Once they freed themselves from the straitjacket of the CPMCL, the workers began to regard with suspicion any government-sponsored welfare scheme. Within this increasingly divided society, the law on cooperatives produced at least two paradoxical effects. The first is that the socialist-sponsored cooperative, conceived as a tool to fight against capitalist exploitation, took advantage of the benefits granted by a legal framework that had been devised for the very opposite purpose—to preserve the stability of capitalism.Footnote 73 A subtle—and perhaps more enduring—consequence has to do with the legitimacy of the cooperative model in the eyes of the country’s emerging labor movement.

In 1876, Azedo Gneco, co-founder of the Socialist Party, made explicit his mixed views on the cooperative model. In a letter to Engels, he expressed his intention to encourage socialist supporters to create their own cooperatives, though he warned that the model had become “detrimental to the working class.”Footnote 74 Through the 1870s and early 1880s, the journals ‘O Protesto’ and ‘O Operário, press organs of the Socialist Party, devoted considerable space to reporting the progress of the existing endeavors. By the late 1880s, however, the growing number of middle-class cooperatives, particularly in the area of consumption and credit, seem to have further reinforced the socialists’ distrust.Footnote 75 From the pages of ‘O Protesto Operário’, the party’s new organ,Footnote 76 these cooperatives were belittled as “politically innocuous,”Footnote 77 and the Cooperative Societies Act of 1867 was depicted as “old-fashioned” and based on “fallacious premises.”Footnote 78 An opinion article signed by João Ramos Lourenço, leader of a socialist reformist current that gained ground in the late 1880s, summarizes with utter clarity the party’s position vis-à-vis state-sponsored cooperatives:Footnote 79

The bourgeois economists present cooperative societies as the only means to address social grievances; they tell the working classes that these are the kind of associations in which they should primarily engage, because they are the ones that aim at improving the economic well-being of their members… . Instead of feeling threatened by cooperative societies, governments regard them as a means to curb the development of the most advanced socialist ideas. By removing political concerns from their program, cooperatives become essentially conservative and selfish organizations, incapable of defending the material interests of their members against the tyranny of capital.Footnote 80

Concluding Remarks

The first cooperatives appeared in the late eighteenth century as pragmatic response to the social dislocations produced by industrial capitalism. By the mid-nineteenth century, they had become a significant economic and political force in most advanced European nations. Interestingly enough, cooperatives appealed to thinkers and activists of radically different political ideologies. While socialists of various stripes recognized their democratizing and emancipatory potential, the champions of free-market capitalism regarded them as instruments for preserving harmony and preventing the eruption of disruptive conflicts between capital and labor.

At the risk of oversimplification, it may be said that the introduction of cooperative legislation in the United Kingdom, Prussia, and France was aimed at shaping the contours of the cooperative movement in a way that suited the interests of the liberal governing classes. Although socioeconomic conditions in Portugal were substantially different from those prevailing in rapidly industrializing countries, the rationale behind the passing of the Cooperative Societies Act of 1867 was largely similar. The members of the Portuguese ruling elite believed in the virtues of industrial capitalism, but they were concerned about the practical (and moral) implications of its inherent inequality. Against this backdrop, they came to the conclusion that cooperatives could be fruitfully used to improve the well-being of the lower classes without compromising the integrity of the liberal capitalist order.

Kingdon’s streams approach has provided some insight into the complex and lengthy process that led the Portuguese ruling elite to this conclusion. In the 1840s and early 1850s, progressive liberals advocated the autonomous organization of artisans and workers. With the beginning of the Regeneration process, however, their position was curbed by the imperatives of political stability and economic progress. It was only when the international working-class movement began to articulate a revolutionary political agenda that progressive and conservative liberals finally converged on the need for a step-change in their approach to the labor question. By then, cooperatives had proved their ability to operate successfully within the boundaries of advanced free-market economies, liberal intellectuals were actively promoting their model, and governments were taking steps to regulate their activity. Realizing that both conservatives and progressives might see cooperatives as an effective and legitimate policy tool, Minister Andrade Corvo (a policy entrepreneur, in terms of Kingdon’s model) drafted the bill that turned Portugal into a pioneer in cooperative promotion.

As described in the last part of this article, however, the attempt to transfer an organizational model across national borders encountered a number of problems. Even by the most optimistic accounts, the cooperatives established under the auspices of the new legislation had a negligible overall impact on the well-being of the Portuguese working class. A plausible explanation for this disappointing outcome may be found on the socioeconomic composition of the country’s labor force. Poor and mostly illiterate Portuguese workers may have been unprepared to establish collective businesses that required at least a minimum amount of working capital, as well as considerable management and leadership skills. To make up for these shortcomings, the law provided cooperatives with economic incentives and logistical support—a novelty of Andrade Corvo’s proposal, which nevertheless did not seem to have had a noticeable effect on the workers’ entrepreneurial capabilities.

Another related explanation for the policy’s lack of success has to do with the changing political stance of the Portuguese working class. The spreading of revolutionary ideals that followed the 1871 Paris Commune affected the workers’ attitudes toward the government’s social and economic policies and programs. Within this new political context, the cooperative—an organization that was being promoted by the liberal elite as a tool to preserve its ruling status—began to be regarded with a certain degree of suspicion and skepticism.

The liberal ideology that inspired the Cooperative Societies Act of 1867 has certainly not sealed the fate of cooperatives in Portugal. Throughout the twentieth century, the cooperative model was embraced by a variety of actors pursuing the most diverse economic and political aims: from republicans dealing with scarcity and inflation during World War I to industrial workers seeking to preserve their jobs in the aftermath of the 1974 revolution.Footnote 81 Cooperatives were used as instruments of agricultural policy by the corporatist dictatorship of António Salazar and simultaneously envisioned as a tool of democratization and emancipation by the humanist and educator António Sérgio.

Despite this richness in ideological perspectives, however, the Portuguese cooperative movement has never reached the scale attained in other European countries. From the perspective of the path dependency theory, one may argue that the liberal, paternalistic foundations of the Cooperative Societies Act may have contributed to this outcome. The mistrust with which the leaders of the emergent working class regarded cooperatives (a direct reflection of elite’s endorsement of the model) may have undermined initial efforts to promote their establishment, setting off a pattern of sluggish development that may have reinforced itself over time. Further historical research should be conducted to investigate this hypothesis, which has the potential to improve our understanding of the long-term effects of policy measures for the cooperative sector.