There are foreign individuals or companies who like to invest their capital in foreign lands in order to increase their wealth. In doing so, they prefer host states that can offer them the best and most suitable protection for their investment. Accordingly, they try to avoid those states where there is risk of expropriation, legal uncertainty, political disturbance, terrorism, undeveloped infrastructures, and so on. Among these, legal safeguards for their invested properties are a foremost requirement for the maximization of business profits. Therefore, legal protection through national legislation or bilateral agreements is a significant attraction for their capital investment, and motivates them towards further investment in host states. On the other hand, host states which are heavily dependent on foreign direct investments [FDI] seek to offer maximum protection to foreign investors and also to ensure that they can exercise their desired economic freedom. Due to these reasons, host states’ laws and bilateral investment treaties [BITs] are significantly influenced by, and geared towards, guaranteeing investment protection. Consequently, the words “Promotion and Protection” frequently appear in foreign investment laws or policies, and especially in BITs.Footnote 1

Foreign investors always require maximum protection of their investment in a host state, and Bangladesh is no exception. Most importantly, they require protection against expropriation and protection through dispute settlement mechanisms. Usually, these protections are guaranteed through FDI legislation and BITs. Nowadays, due to globalization and the fall of communism, there is a unilateral assertion of protection against expropriation through national legislations or BITs. Regarding investment dispute settlement, foreign investors have various options to choose from, and settlement through the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes [ICSID] has become the preferred means of settlement.Footnote 2

In the case of an undesired government intervention or a barrier to enforcement of the investment contract, foreign investors require impartial legal certainty for settling investment disputes. Due to this, host states most often adopt laws or policies to the satisfaction of foreign investors or capital exporting countries, compromising on the requirement of the exhaustion of local remedies for dispute settlement. Given the importance of legal protection of FDI, this paper will explore how far the protection through judicial or arbitral settlement is established in the legal framework and BITs of Bangladesh.

This paper contributes to the existing literature by providing a review of Bangladeshi commercial dispute settlement mechanisms in relation to foreign investments. This research is centred on a desk-based analysis of primary sources, as well as the limited secondary literature on Bangladeshi law. However, a lack of access to materials has prevented analysis of some of the most recent legislative and case-law developments. Nonetheless, this paper provides a valuable first step towards greater understanding on the subject matter.

No empirical fieldwork was undertaken, and further research is needed to analyze the extent to which legislation has been implemented, as well as its effectiveness; this paper provides a firm foundation for such research. The paper commences with dispute settlement mechanisms in Bangladesh, and then discusses various ICSID cases involving Bangladesh. In relation to FDI, domestic arbitral arrangements, international arbitration, conflicts between Bangladesh and foreign investors, and the negative attitude of foreign investors towards judicial protection in Bangladesh are discussed. The commercial dispute settlement laws and policies themselves are explored in detail, followed by an analysis of issues and challenges. Last, tentative recommendations are provided in areas where law, policy, and governance might be enhanced.

I. FDI AND DISPUTE SETTLEMENT MECHANISMS IN BANGLADESH

The Foreign Private Investment (Promotion and Protection) Act 1980 [FPIA, 1980] in Bangladesh lacks any provisions in relation to the method of dispute settlement.Footnote 3 Similarly, the National Industrial Policy 2016 [NIP 2016] also lacks any specific provisions regarding the investment dispute settlement process, and only recommends maintaining “international norms and system[s] in conflict resolution”.Footnote 4 This is only a policy guideline, and not obviously suggestive as to the applicable methods, and usually appears to be blurred. At present, regarding FDI dispute settlement mechanisms, there are no set international norms and systems in Bangladesh. Therefore, in the absence of clear legal provisions, such dispute resolution depends entirely on the relevant provisions in BITs or the parties’ agreements. Given these current circumstances, the FPIA 1980 needs to be amended to close this legal gap by incorporating a dispute settlement mechanism.

In the absence of any specific FDI dispute settlement mechanism in the FPIA 1980, another way to settle investment disputes is through predetermined dispute resolution mechanisms provided in the disputing parties’ BITs or agreements. This includes, among others, bilateral negotiation between the Contracting Parties. Usually, there are two types of dispute settlement provisions available in the investment treaties: those relating to investment disputes and those relating to the interpretation or application of the agreement. In BITs, Contracting Parties mutually agree on the methods of settling investment-related disputes, and when any host state signs a BIT it is giving consent to the foreign investors to invoke remedies through arbitration, which mainly refers to international arbitration systems, such as ICSID. However, many BITs also have provisions for amicable settlement or recourse to the local courts. There is no global consensus on how BITs should be drafted, and they therefore take many forms. Apart from BITs, there are also individual agreements, where parties mutually select specific dispute settlement mechanisms (e.g. by inserting arbitration clauses). Therefore, it appears that dispute settlement matters may fall under the BITs or may be dealt with discretely, depending on the agreements between the Contracting Parties.Footnote 5

Since 1980, Bangladesh has signed thirty-one BITs with various countries, most of which are available on the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development [UNCTAD] website.Footnote 6 All these BITs typically cover three successive options for dispute settlement, with little difference. These are: peaceful settlement through negotiations and consultations; recourse to a local court; and recourse to international arbitration. However, there is a lack of similarity and consistency between the BITs as to the structure of the dispute settlement process. For example, under Article 10 of the Bangladesh-Turkey BIT, investors may submit a dispute to either a competent court of the Contracting Party in whose territory the investment has been made, to ICSID, or to an arbitral tribunal established under the Arbitration Rules of Procedure of the United Nations Commission for International Trade Law [UNCITRAL];Footnote 7 under Article 12 of the Bangladesh-Iran BIT, either the host Contracting Party or investor may refer the dispute to either the competent courts of the host Contracting Party, or to an arbitral tribunal applying UNCITRAL rules;Footnote 8 and under Article 9 of the Bangladesh-Denmark BIT, either Contracting Party may refer the dispute to a competent court of the Contracting Party or to international arbitration under ICSID, by an ad hoc tribunal established under the Arbitration Rules of UNCITRAL, or in accordance with the Rules of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce [ICC].Footnote 9 In contrast, the majority of the BITs refer to ICSID in reference to international arbitration as the primary dispute settlement mechanism, such as the Bangladesh-Uzbekistan BIT.Footnote 10

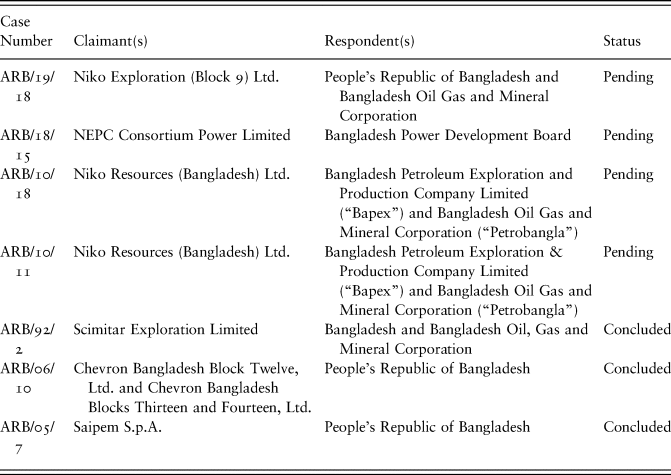

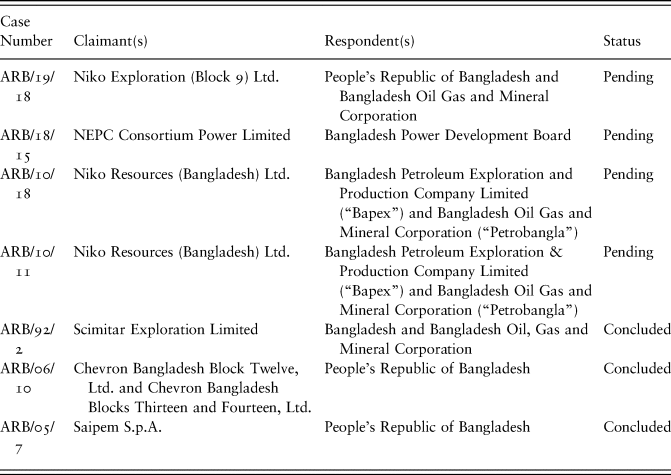

Thus, it appears that sometimes the option for a means of dispute settlement is given—to choose between the national court and international arbitration—and sometimes the option for international arbitration comes as a third stage of dispute resolution. Also, in some BITs, there is an option for the Contracting Parties to choose between local courts or arbitration in default of an amicable settlement. Sometimes the exhaustion of local remedies is a condition, and in other cases the simultaneous application of two methods is required, such as litigation in local courts and in international arbitration.Footnote 11 All three methods of dispute settlement mechanisms are in place in Bangladesh. Interestingly, there is no precedent of amicable settlement of investment disputes between Bangladesh and foreign investors. In the most notable Chevron Footnote 12 and Niko Footnote 13 cases, the Parties endeavoured to resolve the dispute through conciliation, but were unsuccessful in achieving any settlement. Table I shows the list of cases referred to ICSID.Footnote 14

Table I. List of cases referred to ICSID.

In the Saipem v. Bangladesh case,Footnote 15 based on the BIT between Bangladesh and Italy, the Tribunal decided in favour of Saipem, on the grounds of indirect expropriation in the light of an expropriation provision.Footnote 16 In the Chevron Bangladesh Block Twelve, Ltd. and Chevron Bangladesh Blocks Thirteen and Fourteen, Ltd. case,Footnote 17 after hearing the arguments of both sides, the Tribunal gave the verdict in favour of Bangladesh. It concluded that Petrobangla had been rightfully deducting the wheeling charges, and it had the right to continue charging Chevron for the same. In the Scimitar Exploration Limited v. Bangladesh and Bangladesh Oil, Gas and Mineral Corporation case,Footnote 18 the Tribunal observed that, based on the agreed positions of the parties and the uncontested evidence before it, the proceedings were not initiated with proper authorization. Also, there was no evidence that the absence of such authorization had been remedied by any action subsequent to the commencement of the proceedings. Therefore, the Tribunal held that the dispute was not within its jurisdiction.

In the Niko case,Footnote 19 while Niko was drilling the Chattack gas field, two blowouts occurred on 7 January and 24 June 2005. Niko's negligence and lack of experience giving rise to responsibility were evident; however, the arbitrators ignored these and instead concentrated solely on the failure of Petrobangla to make payment under the gas purchase and sales agreement. The Tribunal, in its award, ordered Petrobangla to pay for Niko's invoices for gas delivered from November 2004 to April 2010 with interest compounded annually. On 6 August 2015, Bangladesh requested the Tribunal to declare that “the outstanding amounts under the Payment Claim Decision will be payable … only after all issues regarding Niko's liability are resolved”; but this was rejected. Subsequently, Niko filed another case in 2019 against Petrobangla, which is still pending. In the NEPC Consortium Power Limited case,Footnote 20 the Bangladesh Power Development Board has recently extended the contract for two further years, but its status is now unclear. This is an ongoing case and analysis of the Judgment will need to wait until the Judgment is released.

Sometimes the provision for recourse to domestic courts is curtailed by a contract-based arbitration clause. However, recourse to a local court by any party would not be a violation of a treaty. Nonetheless, the proceedings of the Niko arbitration clearly showed the lacklustre representation of the competing interest of Bangladesh before the Arbitral Tribunal. Bapex did not dispute Niko's factual account of the blowouts and simply stated that it “ha[d] never invoked Niko's liability for the two blowouts” and that “it ha[d] little or nothing to add in response to Niko's description of the facts”.Footnote 21 Also Bapex certainly did not contest in any substantive manner “the question whether Niko breached any obligation or law and whether Niko ha[d] any liability with respect to the blowouts”.Footnote 22 Consequently, Bangladesh lost in a distinctly winnable arbitration.

Bangladesh as a host state is accepting FDI not merely for fun but instead for its economic development—FDIs are not an end in themselves but a means towards the goal of economic development. Therefore, Bangladesh must be prepared and position itself to withstand and face the challenge of international arbitration actions initiated by foreign investors, such as Niko, to protect its national interests.Footnote 23

II. FDI AND JUDICIAL PROCEDURE IN BANGLADESH

In Bangladesh, the High Court Division [HD] of the Supreme Court has original, appellate, revision, and reference jurisdiction to deal with investment-related disputes.Footnote 24 Any complaint related to writ jurisdiction or a violation of fundamental human rights may be lodged with any Bench of the HD. Any decision of the HD is appealable to the Appellate Division [AD] of the Supreme Court, and the HD is also vested with the power to hear appeals from District Judge Courts. Litigation may be lodged with any bench of the HD, which primarily deals with company-related civil matters regarding the Companies Act 1994,Footnote 25 the Banking Companies Ordinance 1962,Footnote 26 and the Admiralty Court Act 2000.Footnote 27 In relation to FDI disputes, the Saipem and Niko cases (discussed above) were initially filed at the District Judge Court by Bangladesh.

Apart from the HD, there are three District Judge Courts: the Court of the District Judge, the Court of the Additional District Judge, and the Court of the Joint District Judge. These courts have original jurisdiction without any pecuniary limit, in addition to appellate jurisdiction to try investment and trade-related cases. Other special courts exist which have specific jurisdiction to deal with commercial and labour related disputes constituted under respective laws that have implications for foreign investment in Bangladesh. These are: the Money Loan Court (the Artho Rin Adalat Ain 2003),Footnote 28 Income Tax Appellate Tribunals (the Income Tax Ordinance 1984),Footnote 29 Labour Courts (the Bangladesh Labour Act 2006),Footnote 30 and Insolvency Courts (the Income Tax Ordinance 1984).Footnote 31

At present, according to the researchers’ knowledge, there are no specific Acts or Rules for commercial dispute settlement (including foreign investment) in Bangladesh. However, some existing provisions relating to commercial dispute settlement are as follows:

• sections 89A, 89B, and 89C of the Code of Civil Procedure 1908 have provisions for Alternative Dispute Resolution [ADR];Footnote 32

• certain provisions in the Bankruptcy Act 1997 provide for ADR;Footnote 33

• based on UNCITRAL Model Law, the Arbitration Act 2001 [AA 2001] introduced a single and unified legal regime for commercial dispute settlement;Footnote 34

• the Money Loan Court Act 2003 was enacted for the settlement of disputes between the borrowers and the lenders under the District Judge Court;Footnote 35

• the Bangladesh International Arbitration Centre [BIAC] provides a neutral, efficient environment where clients can meet their arbitration needs, and also has a reliable commercial dispute resolution service;

• any cyber or digital crime in relation to e-investment will be dealt by the Cyber Tribunal (section 68 of the Information & Communication Technology Act 2006 [ICTA 2006]), and any appeal is dealt with by the Cyber Appellate Tribunal (section 83 of the ICTA 2006);Footnote 36

• Bangladesh is a member of the World Trade Organisation [WTO], so any aggrieved party has the option to file a case with the Dispute Settlement Body of the WTO.

From the above, it may be concluded that existing judicial arrangements in relation to FDI dispute settlement can be strengthened further by establishing a special economic court, as is the case in China. Such a court would deal only with company and foreign investment related disputes.

III. FDI AND DOMESTIC ARBITRAL ARRANGEMENTS

Based on the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration, the AA 2001 was enacted by the parliament of Bangladesh.Footnote 37 This Act has the following salient features:

• it establishes the present legal structure for international commercial arbitration;

• it recognizes and enforces domestic arbitration and foreign arbitral awards involving the existing judiciary in Bangladesh;

• section 2(c) defines “international commercial arbitration”, which covers commercial disputes arising out of legal relationships by foreign investment agreements;Footnote 38

• it covers parties’ procedural rights to justice in pre-award and post-award stages of arbitration;

• it pursues global standards in procedural matters (sections 12, 17, 23–35, 42–4);

• it focuses on party autonomy; minimal judicial intervention in arbitration; the independence of the arbitral tribunal; fair, expeditious, and economic resolution of disputes; and the effective enforcement of arbitral awards;

• it provides a speedy procedural arrangement for seeking remedy by arbitration, and prescribes the place and location of arbitration in Bangladesh;

• it accords all arbitral award the status of a decree of a civil court under the Code of Civil Procedure 1908 of Bangladesh;

• it has incorporated the mechanism of the New York Convention for the recognition and enforcement of foreign arbitral awards in Chapter X;

• it also provides the grounds for the refusal of the award (section 46).

Thus, the AA 2001 creates a single and unified legal regime for commercial dispute settlement as an alternative to judicial settlement. It also gives Bangladesh a legal face-lift, making it an attractive place for commercial dispute resolution in the field of international trade, commerce, and investment.

IV. BANGLADESH INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION CENTRE: A NEW BEGINNING

There are several arbitral institutions that have been developed at the local level for settling disputes, such as the Bangladesh International Arbitration Centre. It is the first international arbitration institution in Bangladesh, and was established in April 2011 with an aim of settling commercial disputes in a quick, transparent, and cost-effective manner. It is hoped that the BIAC will help to bring in more transparency and reliability in the arbitration process, and provide a more cost-effective, quick, and efficient solution for companies which otherwise would have to go overseas to settle disputes.

The BIAC has its own arbitration rules, which conform to the Bangladesh AA 2001, and has also incorporated several of the leading developments in domestic and international arbitration.Footnote 39 Located at the heart of the capital (Dhaka), the BIAC has a reliable commercial dispute resolution service and provides a neutral and efficient environment where parties can meet their arbitration needs.Footnote 40

V. FDI, BANGLADESH, AND INTERNATIONAL ARBITRATION

Since 1980, under various BITs and other international contracts, Bangladesh has acknowledged the jurisdiction of arbitrations administered under the auspices of internationally recognized arbitral bodies over disputes arising out of FDIs, such as the ICC court of arbitration and ICSID. In relation to the interpretation and the application provisions of the agreements, only a few BITs, such as the Bangladesh-Italy BIT,Footnote 41 Bangladesh-Germany BIT,Footnote 42 and Bangladesh Model BIT, refer to the ICC's jurisdiction in investment disputes. However, the majority of BITs refer to ICSID's jurisdiction, as Bangladesh became a party to it in 1980. Since then, ICSID's arbitration jurisdiction has been consistently and prominently pursued in Bangladesh BITs along with others. Moreover, Article 13 of the Bangladesh Model Agreement 2009 suggests ICSID as an option to settle investment-related disputes in the following words:

[T]he international arbitration may be held by the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes for settlement by arbitration under Washington Convention, 1965 provided that both the parties are parties to the Convention. The arbitration award under ICSID shall be binding on both the parties and shall not be subject to any appeal or remedy other than those provided in the said convention.

The Model Agreement also confirms the enforcement of an arbitral award by the domestic court in accordance with domestic law through the ICSID provision. In addition, sections 45(a) and 46 of the AA 2001 articulate a method for the enforcement of a foreign arbitral award in Bangladesh.Footnote 43

From the above discussion, it can be concluded that, by being party to the ICC and ICSID, Bangladesh is showing its commitment to permitting foreign investors to exercise their right to access to justice in settling disputes; thus their legal protection is guaranteed there, insofar as they have access to a fair and efficient method of dispute resolution. Even though the FPIA 1980 does not have any reference to international arbitration, international arbitration still finds its way into the dispute resolution fora for foreign investors through the BITs of Bangladesh. Notwithstanding this, it remains necessary to include the relevant provisions to incorporate international arbitration into the FPIA 1980, as it is the only law in relation to FDI. In doing so, Bangladesh will provide more certainty to the foreign investors, which will likely have a positive effect on FDI growth.

VI. CONFLICTS BETWEEN BANGLADESH AND FOREIGN INVESTORS

A. Dispute Between BTRC and Grameenphone

Grameenphone [GP] is the leading telecommunications service provider in Bangladesh.Footnote 44 In November 2018, the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission [BTRC] declared that GP would be treated as a Significant Market Player [SMP], and since then there has been a disagreement between the BTRC and GP over the penalties for being a SMP. Consequently, the BTRC has been trying to impose various rules on GP in order to restrict its growth and maintain healthy competition in the market. However, GP is still maintaining strong growth in the telecommunications sector in Bangladesh. In this regard, GP claims that it has earned its market share in Bangladesh through fair practices, and within the stipulated market regulation overseeing the industry. To date, this dispute is still ongoing.

Another dispute is ongoing between GP and the BTRC and National Board of Revenue [NBR].Footnote 45 In 2019, the BTRC audited GP's books and claimed that it had unearthed financial discrepancies amounting to almost BDT 12,579.96 crore (US$ 1.5 billion) from its inception until June 2015. Following the order of the Appellate Division, on 24 February 2020, GP paid BDT 1000.00 crore (US$ 11.76 million) to the BTRC.Footnote 46 However, it reiterated that it disputed the validity of the BTRC audit claim and that this deposit should not be seen as an admission of liability.

B. Dispute Between BTRC and Robi

Similar to the Grameenphone dispute, there is another ongoing dispute between BTRC and Robi (the second largest mobile operator in Bangladesh). On 31 July 2019, BTRC issued a demand letter to Robi claiming payment of BDT 867.23 crore (US$ 1.02 billion), including BDT 197.21 crore (US$ 23 million) to the NBR as missed or under payments over a nineteen-year period, detected after a thorough audit.Footnote 47 On 14 January 2020, Robi paid its first instalment of BDT 276 million (US$ 3.2 million) to the BTRC and is due to pay rest of the amount.Footnote 48

The above-mentioned cases were and are being dealt with by the domestic courts in Bangladesh. As it appears that both multinational enterprises [MNEs] were not and are not satisfied with the local court system, this raises certain issues which will be discussed below.

VII. NEGATIVE ATTITUDE OF FOREIGN INVESTORS TOWARDS JUDICIAL PROTECTION IN BANGLADESH

As of September 2019, a total of 3,088,291 cases were pending before the lower courts across the country. Amongst these, 96,114 civil cases were at the High Court Division, and 1,453,107 civil cases were at the Appellate Division, which included investment disputes cases.Footnote 49 Unfortunately, a separate figure of only e-investment cases was not available. As the statistics suggest, there is a huge backlog of cases, which is due to procedural delays, and therefore timely commercial dispute resolution is often not available. Even though foreign investors may mutually agree through BITs to seek recourse through the local courts for settling disputes in Bangladesh, in practice they prefer international arbitration despite it being the case in many BITs that the exhaustion of local remedies is a precondition for international arbitral proceedings to be triggered.Footnote 50

The Saipem and Chevron cases are examples where foreign investors showed their lack of interest in the local arbitration system. However, the government should still boost the confidence level of foreign investors in the internal arbitral system in Bangladesh as it presents a viable route for dispute resolution, one that provides significant advantages over recourse through domestic courts. Notably, the government of Bangladesh did raise its concerns about the international arbitration system, such as cultural differences, bias on the part of the arbitrators, the Tribunal's disregard of issues pertaining to environmental regulation and protection of human rights, location, and so on.Footnote 51 Nevertheless, the government should also increase or develop its capacity of legal skills in conducting international arbitrations, in the light of the shortcomings of judicial protection in Bangladesh.

VIII. FINDINGS

From the above discussions, it appears that a situation of conflict exists between the government and foreign investors in Bangladesh in relation to dispute settlement mechanisms. Despite clear provisions in the BITs or individual contracts, foreign investors are reluctant to seek remedies in local courts or the internal arbitration system. It also appears that both foreign investors and the government of Bangladesh are divided in their own ways in terms of their preference for a dispute resolution mechanism.

In terms of legislation, there are few Acts in relation to ADR, and different procedures are prescribed in different laws; further, so far there are no specific rules. Even though the AA 2001 exists, it lacks coverage of the necessary arbitral techniques. It also has no provision for an appeal on the merits if any party is not satisfied with the outcome of a resolution of the ADR. Moreover, existing FDI laws and the judicial system still require significant development to attain international standards and to increase the confidence of foreign investors. Last, the representatives of Bangladesh have inadequate experience in dealing with international arbitration (ICSID), and therefore require proper training in order to put them in a better position to win cases.

IX. RECOMMENDATIONS

Based on the aforementioned findings, a fair and steady dispute settlement procedure is required to balance the competing interests of both Bangladeshi and foreign investors. In this regard, the following are recommended for consideration:

• in the national FDI legislation (the FPIA 1980), a consent-based dispute settlement clause should be included in the Act;

• only where both Contracting Parties consent can the disputed matter then be transferred to international arbitration in order to settle the matter;

• a proposal can be made to ICSID to establish a region-based arbitral centre, such as one in South and East Asia so as to shrink the cultural gap and the associated costs for countries in this area;

• the “rule of law” is very important for any country; therefore, any trial including and involving MNEs should be conducted with fairness, equality, and justice—and as a corollary, it must be free from any kind of political involvement and bias;

• the government can establish a commission for commercial dispute settlement through ADR, which will lay down principles and policies to make ADR available to all entrepreneurs, including foreign investors;

• training facilities should be increased to train local mediators and arbitrators, judges, and the legal community at large to be capable of settling commercial disputes.

X. CONCLUSION

From the above discussion, it appears that investment-related dispute settlement in Bangladesh still requires more improvement to match international standards, and it is suggested that the aforementioned recommendations can be taken into consideration by the government. Moreover, existing laws and regulations need to be developed, and institutional rules such as the BIAC Rules 2011 need to be re-examined and revised at regular intervals. In doing this, new experiences from disputed cases can be taken into account from their practical implementation. While it is admittedly a difficult task to make the national court systems cohere with different investment-related dispute settlement mechanisms, this process of development should nonetheless be continued.

In order to preserve foreign investors’ confidence, the modernization and transparency of arbitration rules and institutions is a must. As Bangladesh is currently a major player in international trade, and requires more FDI for its economic growth, the government must provide legal security for such investments, including the option of settling commercial disputes through international arbitration. When a dispute arises, foreign investors should not view the government as a competitor, but try instead to resolve the issue through mutual discussion and peaceful settlement. There is no point in making enemies and souring the relationship when any dispute can potentially be solved through friendship (i.e. peacefully). It is hoped that by taking into consideration the recommendations suggested in this paper, Bangladesh will become an attractive destination for foreign investments in the near future.