Published online by Cambridge University Press: 26 April 2005

Departing from interactionally focused research on the “representations” (cf. “constructions”) of the “other,” including recent dynamic approaches to the sociolinguistics of style/styling, this article looks into the practice of talk about men that resonated in the conversations of four Greek adolescent female “best friends.” The discussion sheds light on the interactional resources that participants draw upon to refer to and identify or categorize men, their local meanings, and their consequentiality for gender identity constructions (in this case, both masculinities and femininities). It is shown that personae and social positions of men are drawn in the data by means of a set of resources (nicknames, character assessments, stylizations, membership categorization devices) that occur in, shape, and are shaped by story lines (intertextual and coconstructed stories that locate men in social place and time). It is also shown that the men talked about are predominantly marked for their gendered identities: Social styles that represent men as “soft” (“babyish,” “feminine”) or “tough” (“hard”) are those that are more routinely invoked. Each mobilizes specific resources (e.g. stylizations of the local dialect for “hard” men), but both are drawn playfully. The conclusion considers the implications of such discursive representations for the gender ideologies at work and the participants' own identity constructions and subjectivities.Earlier versions of this article were presented at the Birkbeck College Applied Linguistics seminars and at the 8th International Pragmatics Association Conference, Toronto, 2003. I am grateful to audiences there for their comments, to Nikolas Coupland for fiercely constructive criticism, to an anonymous reviewer for encouragement, and last but not least, to the sharp editorial eye of Jane Hill.

The focus of this article is on the discursive practice of talk about men that was found to resonate in a large number of conversational events in the social life of a close-knit group of four female adolescents. More specifically, the data on which this study is based present a relentless talking of or about men, a constant drawing of space for discussion of absent others, who happen to be men, both specific individuals and more generic males. The men talked about by the participants are their romantic interests or suitors – men they would like to have a relationship with.

Within discourse analysis and sociolinguistics, the phenomenon of talking about others has commonly attracted content categories and labels such as “gossip,” or “talk about third parties”; more specifically in the case of female adolescents, “sex talk” and “friendship talk” have also been used (e.g. Coates 1996). Such characterizations are helpful for capturing the propositional or representational aspects of the phenomena in the data, but, in another sense, they are restrictive labels that do not go a long way in exploring the interactional and/or performance aspects of those phenomena. Furthermore, their links with identity work tend to be focused on the speakers' identities rather than on the kinds of identities ascribed to the talked-about parties and the implications that those can have for self-identity construction.

Nonetheless, representations of “others” are being increasingly viewed in interactional and constitutive terms – that is, as constructions jointly achieved through talk. A case in point is the conversation analytic tradition of membership categorization devices (henceforth MCDs, introduced by Sacks 1992), which departs from the premise that the members' (speakers') descriptions of people and the world are not simple representations but constructions of social and moral orders and realities. It also instructs us that in order for the analysts to have insights into such categorizations, they should be looking not just for category identifications, but also for activities that the members themselves routinely attach to categories (see Baker 1997:131–32). This research has drawn attention to the significance of the social actors' own sense-making devices in any process of categorization. I will show that MCDs are one important way for working up interactional constructions of men in the data at hand.

Another line of inquiry with which the present study can draw interesting parallels is that of “styling the other,” which has attracted interactional sociolinguistic, anthropological linguistic and conversation analytic studies of how the “other” can be discursively constructed. Such studies have unraveled the ways in which “people use language and dialect in discursive practice to appropriate, explore, reproduce and challenge influential images and stereotypes of groups that they do not themselves (straightforwardly) belong to. By performing a variety that is stereotypically associated with a group, they can evoke, represent or even identify with the group” (Rampton 1999:421). The key to this “knowing deployment of culturally familiar styles and identities” is that they are “marked as deviating from those periodically associated with the current speaking context” (Coupland 2001a:345). Studies of styling have richly documented the importance of iterative, quotable fragments of language for the discursive (re)enactment of “other” voices. They have also brought to the fore the difficulties of separating self and other in such cases and telling “where and how the self is being positioned” (Rampton 1999:422).

This perspective is symptomatic of a dynamic approach to language choice and heterogeneity as a marker of style and identity, an approach which has an increasing purchase within sociolinguistics and discourse studies (e.g. see essays in Eckert & Rickford 2001). The realization here is that speakers do complex identity work through creatively and strategically mobilizing diverse (often incongruous) language resources that are typically associated with speakers and situations other than the current ones.

In line with that approach, this study aims at shedding light on the interactional resources that participants draw upon to “construct” men, the local meanings that such constructions present, and their implications for self-identity work. The analysis will draw on work on MCDs and styling, as outlined above, while at the same time moving beyond their typical problematic and expanding their scope in order to address the following crucial aspects of the present data: (i) the systematic co-occurrence of MCDs with instances of styling1

It is to be noted here that there have been no cross-fertilizations between work on stylization and ethnomethodological studies of MCDs.

To take each issue separately, MCDs and styling in the data are themselves part of a package of language resources mobilized when talking about men. These present a continuum of more or less implicit resources that have developed over time and through the participants' interactional history; as such, they bear their meanings more indexically than referentially, evoking a host of associations (Silverstein 1976). Furthermore, they are recyclable and variously used in different contexts (i.e., recontextualized; see Bauman & Briggs 1990).

Language resources for talking about men cannot be disassociated from the discourse activity of story lines about men. The term “story line” is consciously chosen instead of the more widely used “stories” in order to emphasize the dynamic nature, open-endedness, and intertextuality of the activities in question. Story lines are thus defined here as conversationally and situationally embedded and open-ended (as opposed to self-contained), intertextually and dialogically linked, coconstructed spatiotemporal worlds of shared past, future, and hypothetical events. In this sense, story lines depart significantly from the commonly studied Labovian type (Labov 1972) of largely monologic, personal, past experience, nonshared events story (Georgakopoulou 2003a:78; Goodwin 1997:107–12; Ochs & Capps 2001:20ff.). As I will show, story lines locate men in time and space as well as presenting a communality of past, present, and future: Past plots inform and shape future plots but are also revisited in local contexts. This co-occurrence of MCDs and stylization with story lines forces attention to processes of recontextualization and circulation of shared linguistic resources as well as to the participants' interactional history and lived experience.

Finally, the discussion will focus on the importance of talking about men in story lines for the evoking and construction of gender meanings. It will be argued that the men talked about are predominantly marked for their gendered identities, and more specifically their masculinities. Of the available stereotyped masculinities, the ones that are routinely invoked and recontextualized are the two extreme poles of a continuum of social positions: those that mark men as tough (hard) or, conversely, soft (babyish, feminine). Both are worked up playfully on the basis of indexical choices (e.g. stylizations, membership categorization devices) and within story lines. The article concludes by considering the implications of such categorizations for the gender ideologies at work and the participants' own identity constructions and subjectivities.

The data for this study come from the self-recorded conversations (20 hours) of a group of three Greek women (a fourth female person joins in occasionally but is not seen as a “core” member). The ethnographic study of this group was conducted in the context of a larger study of young people's peer groups in Greece; the fieldwork took place in various stages between 1998 and 2000. When the recordings started in early 1998, the participants were 17 years old and living in a small town of 25,000 inhabitants in Arcadia, part of the Peloponnese region in southern Greece. At that point, they were resitting their university entrance exams and, as such, were outside the school framework. Their daily routine thus involved self-study in the mornings, private tuition in the early afternoons, and socializing thereafter; the last mostly took the form of hanging out with one another and chatting at cafés. This regular socializing over a long period of time (the participants had known one another and, in their description, had been “best friends” – the term in the original is kollites, ‘glued friends’ – for 10 years) had resulted in a dense interactional history, rich in shared assumptions that were consistently and more or less strategically drawn upon to suit various purposes in local interactional contexts.

The participants had a whole identity kit as an emblem of their togetherness: They dressed similarly, went to the same gym, shared musical tastes, and so on. Furthermore, in the ethnographic interviews and their conversations, there emerged a number of shared social group representations and language ideologies – that is, representations that construe the intersections of forms of talk with forms of social life, linking language differences with social meanings (Woolard 1998:3). The most predominant of those involved the participants' explicit distancing from the local dialect, particularly the broader instances of it that were mostly to be found in the villages surrounding the participants' home town. The participants frequently made jokes about and mocked a key phonological feature of the dialect, the palatalization of lateral /l/ and nasal /n/ before front vowel /i/ (Newton 1972). In contrast, they seemed closely affiliated with and aspiring to what they defined as the Athenian accent.2

It is important to note here that the Athenian accent is not to be taken as an undifferentiated whole. Although sociolinguistics studies of its variation are sadly lacking, the study participants seem to model their own accent on certain youth-oriented TV shows and media personalities.

An integral part of talk about men in the group's conversations involves locating men in physical time and space in the participants' small-town community. These spatiotemporal locations are mostly articulated in story lines, or meaningful configurations of temporally ordered events, characters, and activities. This process of locating involves informing other participants of the recent whereabouts of men they are interested in; it also allows participants to make plans for future meetings with those men. To understand how such story lines work, it is important to have a picture of the participants' social and physical landscape. Within the town's topography, the most important places for the participants are those that are centered around socializing: cafeterias, bars, pubs, and so on, “hang-outs” (stekia) which almost without exception attract people in the age group of 15 to 30, with a concentration of 18- to 24-year-olds. These hang-outs have been added to the town's landscape in the past 10 years, in some cases replacing the patisseries which used to host family Sunday-afternoon outings. Few traditional cafés for men remain open, and those are in the town's main piazza, where no youth hang-outs are to be found. Hang-outs are mostly concentrated in a street that was recently made a pedestrian mall and filled up with bars on each side. Young people now refer to it as the “pedestrianized street” (pezodromos). Youth-oriented shops (e.g. boutiques, music shops) are also important, but mostly as meeting points. Men in whom the participants are interested tend to fall into two broad categories: those who hang out vs. those who work in a hang-out.

The ethnographic study of the group revealed that the complex semiotics and aesthetics of a hang-out were encapsulated in the so-called alphabet of hang-outs, where each letter of the alphabet stands for an aspect of a hang-out that is important for the participants (for a detailed discussion see Georgakopoulou 2003b:416–19). These aspects mostly revolve around the opportunities they afford the participants for meeting men they are attracted to or would like to get to know better. There are two important aspects in that connection. A big-screen television is an important feature of a hang-out, as it allows for watching sports events, particularly football and basketball matches, which are popular among the young men of the town. The presence of a big screen guarantees attendance by men at specific times (mostly early evening) and on specific days of the week. The second is visibility with reference to the street(s) adjacent to the hang-out and to the passersby; this can have implications for the types of narrative plots that the participants construct with respect to meetings with men.

In Blommaert & Maryns's study (2000:67), place in narrative inevitably interacts with time, particularly at the level of inducing time frames. This applies to the data at hand as well: Different hang-outs are associated with different time frames, both in the sense of times of the day, seasons, and so on, and in the sense of social time (e.g. festive occasions). Thus, narratively referring to places also invokes certain temporal frames of reference. In turn, such associations between place and time become a part of possible story lines, which develop out of habitual and reproducible activities and types of events at specific times and in specific places. At the same time, it is noteworthy that the story lines are discursively constructed in hang-outs and as part of the participants' daily socializing over a cup of coffee or a drink. In this way, the setting acts as a sphere in Hill's conceptual terms: “an interactional zone felt to be dedicated to particular purposes … characteristically accomplished at certain institutional loci and felt to have at least a relative temporal stability, that elicits from speakers particular genres and registers of language” (1999:545). In sum, story lines about men are mutually implicated with lived place and spheres of interaction, and simultaneously keyed to texts, situations, ways of speaking, and speakers.

As already suggested, talk about men in the data is a discourse practice that involves storytelling activities (story lines) and specific ways of referring to men. The two are intimately linked: Not only are ways of referring to men routinely part of the construction of story lines, but they themselves also are largely traceable in “key episodes” and “key events” (that is, lived or interactional story lines) in the group's history. As I have shown elsewhere (2001, 2002), these story lines are dialogically interrelated: Stories of past events that the group have co-experienced or told are revisited and retold in the context of other stories about future events. In this way, past story lines shape a horizon of expectations for future story lines. The tellings of the story lines in the data are thus heavily embedded in the surrounding talk (as opposed to self-contained), unfinished (ongoing), and intertextually linked. Although they are told (and retold) in different encounters and at different times, they are linked in a complex speech event (here referred to as discourse activity), that of talking about men. In this way, they are reminiscent of Goodwin's “family” of stories – stories that are structurally different but integrally linked and deeply embedded in the larger process of disputes in the conversations of certain adolescent females (1997:111). The main story lines are as follows:

Breaking news (“reports”)

Projections (near future events) --------------- hypothetical scenarios

Shared (near) past events ------------------ reminiscing

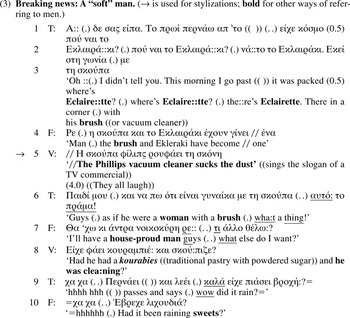

In breaking news, participants report recent sightings of men in hang-outs. Consider the following example:

As we can see, the newsworthiness of breaking news resides in the actual sightings of men: In this “spotting” game, the more desirable a man is, the more noteworthy a sighting of him is (see the reaction of Fotini, line 8, to the mention of a sighting of a man nicknamed “Baileys,” line 7).

The role of projections in the group has been discussed in detail elsewhere (Georgakopoulou 2002). These are by far the most common type of stories in the data. Projections present many intertextual connections among them; they are typically about men, in the sense of planning a meeting with and/or asking out the man that one of the participants happens to be romantically interested in. This planning involves a turn-by-turn co-authoring and negotiation of details in the taleworld, particularly of an orientation kind (e.g. time, place; see lines 8–10 below):

The plotline of projections typically consists of planned events and verbal interactions (of the ‘You/we will say – he will say’ kind; see exx. 4, 5.22, 26–27 below). Stories of projected events are dialogically connected to stories of shared (known) past events. In the context of future narrative worlds, participants draw upon shared past narrative worlds in order to support and legitimize their own projected version of events (for a detailed discussion, see Georgakopoulou 2001).3

Reminiscing, the other end of the continuum of stories of past events, is outside the scope of this article. Although recent stories of past events tend to be shared, these can be first-time tellings. They too can be used argumentatively and in the context of projections.

Monos monos, an allusion to the slogan of a popular TV advertisement about a travel agency called Manos, has achieved in the group's interactional history the status of a successful chat-up line and has enhanced Vivi's “street credibility” when it comes to older and experienced men. Vivi famously uttered this line when she asked out Nikos, a man in whom she was interested, and his response was positive. At that point, I had already started working with the group. I was thus in a position to experience the life cycle of this quotation. For weeks after the incident of asking Nikos out had taken place, monos monos appeared as the punchline of a story that was triumphantly told and retold, first by Vivi and then jointly by the rest of the group – the story of how Vivi asked Nikos out. I was told that details of the story had been recorded in the group's diary (literally called “Proceedings”), to which I nonetheless never obtained access. After that, retellings of the story gradually became briefer and more elliptical, to the point that, about six months later, they were normally condensed to the quotation monos monos. Monos monos was thereafter variously recontextualized in stories of projected events: As is the case with the group's citations that are traceable to their interactional history (also see discussion below), monos monos started to be used as an argumentative device by different participants in the context of projections.

In addition to projections, another type of stories of events that have not happened yet is that of hypothetical scenarios. These are less anchored in a specific temporal frame, although their events too are temporally ordered; as such, they show less commitment to the events' actually taking place. Orientation details are not so heavily discussed and negotiated. Finally, they tend to be in the form of short episodes that involve the dislocation or displacement of the men talked about from their normal spheres of activity (see ex. 6 below).

In their synergy, references to men and story lines construct social roles or personae of men inasmuch as they bring up and rework cumulative fragments of a lived shared biography, including known attributes of the characters talked about. These in turn can be brought to bear on personae that are fleetingly and momentarily tried on and experimented with in the course of constructing story lines. The main resources for talking about men are:

The term “stylization” is chosen here over terms such as “quotation,” “impersonation,” “enactment of voices,” etc., to capture the fact that such instances involve exaggerated and performed shifts to “codes” other than the one of the surrounding talk (and, for that matter, the participants' baseline idiolect). Rampton (2003:55) provides a set of diagnostic criteria for what is undoubtedly not a straightforward process of identifying what constitutes stylization (e.g. as opposed to routine variability). The co-presence of performance elements that are set off from the speech both before and after (e.g. increased density in co-occurrence of marked phonetic features, marked grammar, lexis, quotative verbs, abrupt prosodic shifts) is an important criterion and one with resonance in the stylization instances of the data at hand. Formulaicity and fixedness in linguistic expression are another common element in the data. Finally, all turns that introduce stylization in the data are followed up with some kind of acceptance, recognition, or ratification response (e.g. laughter; cf. Rampton 2003).

The common denominator of these resources is that they are traceable to the group's interactional history: They are resources that have developed over time and are shared, and thus they are indexical – short-cut devices that can evoke a whole range of meanings and connotations for the participants. Furthermore, as has been shown about indexical resources (e.g. Spitulnik 2001), they are recyclable (repeatedly used) and recontextualizable (locally occasioned in different ways). Through such repeated uses, they tend to develop a fixity in language expression, and their indexical meanings get consolidated (Spitulnik 2001:99), so that, for example, mentioning a nickname conjures up a whole set of meanings and associations that have been added to the original meanings (see the discussion of the nickname “Eclairette” in ex. 3 below).

Ways of referring to men present a continuum in terms of explicitness. Categories of identification are sometimes named (as in character assessments), and at other times implied through the activities attached to them. The choice of specific descriptors here, as ethnomethodologists have argued, is “from a range of possibilities” (Baker 1997:132). As such, it constructs one version of moral and social worlds and not another. In turn, the selection calls on specific domains of reason and knowledge and calls into play certain categories or activities attached to them. As the discussion will show, the participants routinely associate a set of activities, places, occupations, physical traits, and social behaviors with the categories “man/woman”; gendered positions, or “male/female,” are constructed on the basis of them. The enactments of voices of the men talked about are even more implicit. In this case, “repeated performances lead to increasing stylization, as people come to expect a limited set of features to index a relatively limited repertoire of ways of using the same variety” (Johnstone 1999:514). Stylizations are mostly quoted punchlines or formulaic (through repeated use) fragments from shared stories, such as monos monos, discussed above.

The following excerpts will show how modes of reference to men and story lines about men co-occur and work together to evoke images of the characters talked about. It has to be stressed that all such constructions draw on and construct a multiplicity of meanings. They are also locally occasioned: The same fragments of speech perform different social actions in different contexts (Antaki & Widdicombe 1998). Having said that, it still is an inescapable fact of the data that talk about men has to do with sexuality, in the sense of the socially constructed expression of erotic desire (Cameron & Kulick 2003:4): The men talked about are men with whom the participants wish to form an erotic relationship. It is not accidental, then, that the constructed voices, images, and personae of those men are deeply gendered and specifically related to notions of masculinity.5

Details of a man's body, outfits, gaze, movement, etc., are also frequently invoked, particularly as part of breaking news.

This breaking news story line typically introduces the character talked about with a nickname (line 2,

; also see the nicknames “Danny” and “Baileys” in ex. 1, and “Carnation” in ex. 2). Nicknames figure prominently in breaking news: Conversations occur in public places, and it is important that the participants use their secret code. In addition to that cryptographic function, however, nicknames are ways of conjuring up a host of shared meanings that make the activities reported intelligible. These meanings both get reinforced in their local use and render new plots intelligible.

In this case, the nickname “Eclairette” is the diminutive form of the name of a pastry and has loose connections with the fact that the talked-about person frequently buys that pastry in quantities from the patisserie that Fotini's father owns. In the interactional history of the participants, there has been a suspicion that such visits are owed to the love interest that the man in question has in Fotini. Nonetheless, over a period of three years in use, the nickname has developed added layers of meaning. Its associations with sweetness have lent themselves to the attribution of feminine qualities to Eclairette. The gendered representation that this nickname short-cuts is that of a man with a feminine side. Tellingly, the breaking news episode above both indexes those meanings and adds to and reaffirms them. The story line is about Eclairette's domestic nature in the shop where he works. The activity of vacuum cleaning gives rise to a playful exchange in which an ironic tone is added by reference to a shared text, a slogan from a TV commercial (line 5) that is sung by Fotini. A clear parodic reference to the unmaleness of the reported activity is provided by Tonia in line 6. This line gives us a glimpse into MCDs and category-bound activities. Cleaning is something women do and men don't. Two lines of association work in parallel here to make up a “feminine” persona for Eclairette: domesticity and sweetness. The associations with sweetness are also picked up again in line 8 by Vivi. Her question is ironic. Language here is a “resource that allows a more subtle reconfiguration of meanings, through allusion, intertextuality, irony and co-operative humour” (Harvey 2002:1146–47).

Interestingly, there is no single label attached to such men by the participants.6

The term “new man” has not been translated into Greek. The term floros (pejorative for a “feminine” man) is infrequently used by the group. In addition, the men are not perceived as gay, although their speech is stereotyped as “camp talk.”

In a similar vein, consider the following example from the same story line as ex. (1):

The character talked about owes his nickname, “Carnation” (a brand of milk), to the nature of his family business, a traditional dairy-products patisserie. As with the nickname “Eclairette,” through recycling and recontextualization, the nickname has developed additional connotations. It also tends to co-occur with cues that represent the character as a soft man, such as humorous references his baby face and love of dairy products (themselves associated with babies). In (4), a dairy product, milk pie, is mentioned jokingly as the character's main “preoccupation” (line 44) and one that is set in contrast with a concept of social life. Vivi (line 45) responds with another reference to a dairy product that is tellingly rendered in diminutive form in Greek. This reference introduces a incongruous comic element (Vivi utters this laughingly) into the scenario of Tonia asking “Carnation” out.

While MCDs that are associated with the categories of “woman” and “baby/child” as well as camp talk play an important part in the stylization of soft men, it is the local dialect that provides the main vehicle for the enactment of hard men. Consider the example below:

Hard men (cf. “macho,” “tough”; referred to by the participants as adraklas ‘big man’, varys ‘heavy’, but also gatos/a, a category reserved for older, sexually experienced and exploitative men), such as Makis (nickname “Mikes”) and Pavlos above, are talked about by the participants as inarticulate, particularly around women, and lacking communication skills; they watch and play basketball and football, and they hang out with other men. They are also invariably represented as local men (some of them specifically called vlachoi ‘peasants’) and stylized with mainly phonological shifts to the local dialect. Local, in this case, includes a strong affiliation with the community. It is no accident that local men are presented as settled in the community, with no plans or aspirations for leaving it (e.g. for study or professional reasons). In fact, the local dialect is frequently described as “their language.”

In this respect, Johnstone's study (1999) is very illuminating in that it “raises questions” about “stylization in contexts in which the variety being adopted does not clearly “belong” to the outgroup” (505). Johnstone shows how speakers can have an ambivalent – partly “theirs,” partly “ours” – and very situated relationship with the dialect of their community, so that “region and the speech of people from that region are mediated by individuals' rhetorical and self-expressive choices” (1999:515). In the case of the data at hand, the women explicitly position themselves in the interviews outside the local variety; they also routinely and parodically stylize men with regionally marked language. Nonetheless, in their interactions, there are also instances of other kinds of rhetorical and more or less strategic switches to the dialect. Note also that a standard variationist analysis of their speech suggests the occurrence of certain phonological dialectal features in it, with varying frequency depending on the formality, topic, and other features of the interaction, and with clear quantitative differences among individuals; for example, Fotini is the speaker with the most dialectal features in her idiolect.

Stylizations of local men tend to be accompanied by switches to a stereotypical male voice. Furthermore, lexical choices characteristic of Greek magika (sociolectal vernacular) also occur. In (5) above, even before the character's voice is stylized, the first mention of Makis (line 22) is followed by a dialectal lexical choice in line 23 (kalandra instead of kalanda). This choice is recognized as a strategic style-shift on Tonia's part, a conscious deployment of another voice, as Vivi's laughter suggests. Despite Fotini's attempt to reorient to the story line under construction (line 25), the stylization is continued: Vivi's mention of ‘his [Mikes's] language’ (line 26) is immediately followed up by a phonological downshift that involves the raising of the unstressed mid vowel /o/ in the verb /pao/ (in this case, ‘fancy’) to /u/ (pau).7

Interestingly, this is not part of the local dialect, but a typical feature of Northern Greek dialects (see Newton 1972). This unlikely combination of Northern with Southern regional features, one that could not be part of a “realistic” and “authentic” representation of the speech of the character impersonated, may be seen as an indication of a critical strategy and parody at work. Certainly, the participants are perfectly aware of the features of the regional speech, having spent all of their lives in the specific community.

Stylized phrases tend to co-occur in the group's conversations, thus forming part of a synergy of signals which work together to achieve the hallmarks of instances of stylization, as discussed by Rampton 1999 and others: a temporary breach of the ongoing activity, and language use that markedly departs from the current context. As we can see in (5) above, Tonia and Fotini echo the dialectal shift of se pau in lines 27 and 28: O idjos becomes U idjus (line 27); in addition, the /n/ of the name Fotini that precedes /i/ is palatalized (as already mentioned, this is a typical feature of the local dialect). Again, laughter accompanies these instances of stylization. This is one of the indications of stylization being taken up by the participants as a playful suspension of the ongoing activity. In fact, Fotini twice reorients (lines 25, 29) to the story line under construction as the main business in hand.8

That said, as I have argued elsewhere (2002), they are very much part of the interpretative grid for the story line under construction.

The stylization ends with the impersonation (line 30) ‘Talk to him man (..) talk to him man’, which comes from a shared story and forms one of the group's most recyclable quotations. In its uses, it epitomizes lack of communication skills and sociability, and it is exclusively reserved for men (in particular, Makis; in the story from which the phrase has been extracted, it served as the punchline and was in fact addressed to Makis, as a character in that taleworld). The phrase is told in a “harsh” tone of voice, which the participants stereotypically associate with hard men. So far, the representation of machismo and toughness for Makis is engineered by means of indexical cues: regional lexis and phonology, vernacular intonation, stylized set phrases. In the rest of the projection (which happens to be particularly long), category-bound activities associated with hard men are brought to bear on (to allow or disallow) the emplotment scenarios that the participants try on and jointly negotiate: The fact that Mikes and his friend Pavlos watch basketball at a specific time in a specific hang-out informs the story's plot. Character assessments are also used as part of a gradual drafting of a position of toughness for Mikes. As my previous close analysis of the story and the participants' interactional roles in its telling has shown (Georgakopoulou 2002:433–44), Vivi and Tonia collude in an attempt to convince Fotini not to get involved with Mikes. Drawing up a representation of Mikes as tough in this case becomes part of the local project of undermining Makis.9

The categorization of a talked-about man as “tough” (or “soft”) is situated, and its meanings are intricately localized.

The two kinds of male persona illustrated above can also be drawn for different characters of the same story line. In such cases, it is arguable that their contrastive relationship brings out particular meanings more forcefully. Consider the following example:

The excerpt starts off with breaking news (lines 1–3) which intertextually leads to a hypothetical story line (lines 5–8) involving the main character talked about (Sotirakis). The stylization of Sotirakis (note the diminutive) in line 2 enacts a child's voice. Other MCDs mobilized here and activities attached to them evoke stereotypical imageries of children/babies: the diminutive form in the character's name (Sotirakis lit. ‘little Sotiris’); the reference to his smile (line 3) and eyes (line 4; notably blue); the consumption of orange juice (line 7; also in diminutive form); the characterization of Sotirakis as a “baby” (line 7) by characters in the taleworld; and in a similar vein, the bar woman's baby talk (line 10). This representation of Sotirakis is set in contrast to the location of the hypothetical story line in a bar ‘outside’ (ektos)10

There is a sense of adventure and escape associated with hang-outs outside the participants' town. This is accentuated by the fact that it is normally men who venture out, as women of my participants' age are not allowed by their parents to leave the town for evening entertainment.

Part of the representation of Sotirakis is drawn by being put in the mouths of his male companions in the hypothetical taleworld (lines 7–8): their voice (in the form of a chorus) is stylized as a stereotypically “male” one, which stands in sharp contrast to the stylization of Sotirakis's enacted voice (line 2). The unmaleness of Sotirakis is thus juxtaposed to the maleness and toughness of his friends. As is typical in the data, however, both kinds of representation playfully invoke shared meanings in ways which do not bring to the fore clear, straightforward, or sustained affiliations or disaffiliations of the participants with one or the other. Evidence for this was found both during the fieldwork and in the group's conversational data. To begin, as already suggested, hard men tend to be local, older, and sexually experienced. Although the group, particularly Vivi, oppose the community discourse according to which young girls should not go out with much older men, they also very frequently refer to “bad experiences,” “lessons that have been learnt,” and the “need to be very careful about any kind of sexual attraction towards them,” which they admit often occurs. From this point of view, one can best talk about ambivalence rather than clear lines of affiliation or disaffiliation. Similar things apply to the case of soft men: pros are constantly weighed against cons, and the situation is best described as one of mixed feelings.

In a similar vein, in the group's conversations, although stylizations of both hard and soft men are oriented to as playful, ludic, and even parodic instances, the men stylized are not statically and uniformly constructed as “bad.” Instead, different participants may position themselves differently toward the same man talked about in different local contexts, and to suit different purposes. For instance, in (5) above, although all three participants playfully stylize Mikes, they have different views on him: Vivi and Tonia present him in a negative light while Fotini is keen to go out with him. Alliances or lack of them are thus strategically and contextually constructed, and as such, they are dynamic, contingent, and even indeterminate. In that respect, judgments of which of the two types of men, hard or soft, ranks more highly in the eyes of the participants can be made only as reifications or naturalizations of the data. On the ground, the picture is that of ever-shifting affiliations and disaffiliations.11

Eclairette of ex. (2), for instance, is frequently parodied for his lack of masculinity, yet toward the end of the story in (5) above, he is invoked by Tonia (‘=Man (.) Eclairette's s-so:: much better!=’) and Vivi (‘=By far (..) by far’) as a more suitable candidate than Mikes as Fotini's boyfriend.

The discussion above shows how talking about, enacting, and styling men is a broad interactional practice of dialogically locating them (in the sense of bringing them into social location and time, conferring spatial and temporal specificity; see Butler 1997:29) through interrelated story lines and categorization or reference cues (cf. address and naming in Butler 1997: 28–38). In this way, it is both practice-enabled and practice-enabling: a mode of articulating men (making them the talking point as well as constituting them), indexing them (more or less subtly evoking hosts of meanings associated with them and their locations in social space and time), and gendering them (playfully invoking notions of masculinity). As shown, this process of gendering mobilizes two main and largely contrastive representations of men as soft (feminine) and hard (tough, macho). No straightforward relationships of affiliation were identified with any of the two representations. Instead, they both seemed to be drawn playfully, and at times parodically. Parody is located here in any exaggerations of the speakers' orientations to identities (e.g., in the co-occurrence of Northern Greek dialect with local dialect features).

The gendered meanings and ideologies of such representations on one hand have to do with shared associations and definitions of masculinity, femininity, and male-female relationships within the group. On the other hand, they interact with and certainly make visible certain mainstream and stereotypical discourses of masculinity in the small town where the participants live.12

As social identities tend to be co-articulated and interact in various complex ways (Ochs 1992), it needs to be stressed that it is not just gender ideologies and identities that are operative here. Cultural ideologies of regionalism and urban (capital) identities are also important. Tellingly, the participants were at the time of the recordings preparing to move out of their home town and go to a bigger city (possibly Athens) to study. The ways in which gendered positions coarticulate with cultural and other ideologies and identities are beyond the scope of this article.

In that light, the participants' discursive constructions of men present interesting parallels with the citations of notions of femininity that have been reported as part of “queerspeak” (Harvey 2002). In his study, Harvey discusses in detail (2002:1158–60) similarities between the concept of citationality (adapted from Butler 1993) and other closely related concepts, such as performance (genre), intertextuality, parody, double-voicing, and quotations (this list could easily include stylization as well). He argues that citationality captures heightened awareness and self-referentiality; it signals vigilance in relation to the code along with a parodic stance (2002:1153), while at the same time being more diffuse and general than parody. Although boundaries between these notions are not clear-cut, as in the cases of citationality, both the orientation to form and the critical strategy are important in the representations, including stylizations, of the data: They too are “predicated on a self-consciousness, a knowing allusiveness, meant not only to bond speaker and hearer but also to index even to mock the means of its achievement” (2002:1159). In both cases, specific shared understandings are playfully alluded to. There is also a frequent mixing of elements, resulting in humorous incongruity.

Citationality in this respect makes a sharper comment than stylization on the degrees of critical awareness and self-referentiality involved in enacting “other” voices. Although work on stylization has stressed that in such cases it is very difficult to locate self and other, relevant studies have by and large brought to the fore instances of playful appropriation of and heartfelt identification with the enacted voices (Hill 1999:547). From this point of view, citationality can be usefully applied to the data to capture the critical distancing and acute meta-awareness involved in the participants' “doing” male voices. In addition, there is another layer of meaning that citationality allows us to bring in: the idea that the stylized other voices can be specifically and stereotypically gendered voices. These can be drawn upon and evoked in the social actors' attempt to develop and reflect on their own gendered voices.

Although not concerned with gender, Rampton 2003 has identified the performative stylization of British “posh” and “Cockney” in the conversations of adolescents as a way of denaturalizing cultural class hegemonies: “Through the process of objectification … stylization partially denaturalized this pervasive cultural hierarchy and disrupted its authority as ‘doxa’,” as an interpretive frame that was “accepted, undiscussed, unnamed, admitted without scrutiny” (Bourdieu 1977:169–70, quoted in Rampton 2003:76). This interpretation is not far from Butler's ideas about the potential for subversion and resignification of meanings that performative acts have – “a potential to break with their original context assuming meanings and functions for which [they were] never intended” (1997:147). By the same token, it can be argued that there are acts of resistance and subversion in the performances of masculinities put on interactionally by the women of this study. The notions of masculinity they work with are always of a dominant or mainstream kind in the sense of widely available discourses within their community13

This clearly turned out to be true in the ethnographic interviews both with the participants and with their parents. In addition, although a full discussion is outside the scope here, stereotyped representations of “macho” and “soft” men were frequent in the kinds of media that the participants engaged with (e.g. magazines they read frequently, their favorite TV programs).

At the same time, to echo Butler again, “social performatives ritualized and sedimented through time are central to the process of subject formation” (1997:157). In the data at hand, this would mean that constructing gendered positions for men is an integral process for the participants' constitution of their own gendered selves: They learn about self through representation of the other, through looking into the boundaries between self and other. They are certainly at an age at which their notions of sexuality and femininities are not settled (if they ever become so). Constructing and deconstructing “other” gendered positions (in this case, male) can thus be legitimately linked with the process of exploring and ultimately naturalizing (Butler 1993) their own gendered positions.

On another level, talk about men is a powerful discursive practice in the group for constructing and communicating desire and sexuality. As shown, the story lines mainly involve hypothetical scenarios and events that have not taken place yet. The fictionalizing, imaginary, and even fantasizing elements of such stories are pivotal in the process of knowing and intimating the other.

Drawing on recent sociolinguistic approaches to the discursive representation of “others” (e.g. styling) and the ethnomethodological work on MCDs, this article has attempted to shed light on the discursive practice of talk about men that was found to be salient in the conversations of a group of four female adolescents. More specifically, the discussion focused on the interactional resources that participants draw upon to “construct” men, the local meanings that such constructions present, and their implications for self-identity work. It was argued that talk about men consisted of specific cues (categorizations/identifications) and of story lines as specific activities in which these occurred and, in fact, largely originated. Put differently, resources for talking about and referring to men were embedded in and integrally connected with the emplotment (both actual and possible plots) of story lines that were intertextually linked and that concerned men. Furthermore, they acted as indexical resources, frequently presenting a fixedness in linguistic expression (e.g. nicknames), which carried and evoked in their recontextualization a history of connotations and meanings. In this way, talk about men involved a rich semiotic system of shared representations and associations between ways of speaking and situations.

On another level, the resources for talking about men were intimately linked with the social roles and identities that were ascribed to them. These concerned their masculinities and mostly invoked and recontextualized the two extreme poles of a continuum of social positions – those that mark men as hard (tough) or soft (babyish, feminine). Both were worked up playfully on the basis of indexical choices (e.g. stylizations, MCDs) and within story lines. It was suggested that constructing those gendered positions for men was an integral process for the participants' constitution of their own gendered selves.

As already mentioned, the findings of this study extend the typical scope and problematic of work on styling in two ways. First, they show the need for looking into the co-occurrence of instances of styling with other social representation cues. Second, they suggest the importance of locating instances of styling in specific discourse activities. Hill's instruction here is pertinent: In her discussion of studies of styling, Hill urges that such phenomena are explored in terms of “interactional zones,” “spheres of activity,” and “other dimensions of social organisation that we might recognise beyond the strictly local context” (1999: 545). In the data at hand, stylizations could not have been disassociated from a specific interactional practice (story lines involving men) in informal/leisurely conversational contexts, which, as shown, were themselves part of a trajectory of interactions and of a social chrono-topology. Finally, they point to the potential for cross-fertilization between styling and identity analysis that is specifically keyed to cases of crossing into gendered voices that are not demonstrably the speaker's, as I showed in discussing the concept of citationality.

On a different note, the findings of this study provide further evidence for and understanding of the recently offered view of styles both as pivotal for social representations and as constituting a package – a rich semiotic system that associatively links speakers, speech styles, discourse activities, situational contexts, and social categories (Irvine 2001:77; cf. Bauman 2001). Talk about men in the data mobilized the conventional co-occurrence of linguistic signals and their associations with specific speakers (types of men), activities, practices, and contexts of use. In this sense, it was firmly grounded in shared social evaluations of both types of speaker and speech.

Finally, it is hoped that the focus of this study on the construction of gendered meanings and roles that are not demonstrably the speaker's will have implications for identity work with a gender focus. This is a relatively unexplored phenomenon with huge potential for identity analysis. However, insights into it do not come readily from the otherwise illuminating research that has worked with a somewhat cozy distinction between women doing femininities and men doing masculinities (e.g. Coates 1996, papers in Johnson & Meinhoff 1996). More pertinent are the ideas of performativity and “polyphonous identities” (e.g. Barrett 1999; Butler 1993, 1997) which stress the contradictory and multiple repertoires of positions available and problematize distinctions between “authentic” and “represented” identities (also see Bamberg 1997, Coupland 2001b); further useful studies highlight the staged acts (in the sense of embodied performances) involved in the constitution of gendered subjects and positions (Butler 1993, 1997), and are alert to the sophisticated traffic of citationality and allusion underpinning gendered talk (Harvey 2002).

Such ideas have more often than not been divorced from empirical micro-analysis; what is more, when they have filtered down to interactional work, they have mostly been applied to cross-sex talk (and transgenderism), thus not informing other strands of research. To this effect, local interactional constructions of the “other” could become an integral part of the research agenda on language and gender, bringing in new perspectives on the construction of the participants' own gendered identities.