Introduction

Malaysia remains an attractive destination location for refugees from countries in Southeast Asia, South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM) reports that the number of documented and undocumented foreign residents in Malaysia, including asylum seekers and refugees, has increased significantly over the last fifteen years. There is a significant presence of migrant workers from Indonesia, Nepal, Bangladesh, India and Myanmar, in addition to refugees and asylum seekers from Yemen, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Palestine. Indonesia in particular has contributed a large number of migrants to the Malaysian labour market, as well as to those of Saudi Arabia, Hong Kong, and Taiwan over the last 30 years (Latief Reference Latief2017; Loveband Reference Loveband, Hewison and Young2006; Silvey Reference Silvey2006).

The Indonesian government sent at least 250,000 migrant workers abroad each year from 2017 to 2019 to work in the formal or informal sector. A survey by the Indonesian Migrant Workers’ Placement and Protection Agency (BNP2TKI) found that in 2017 and 2018, 262,899 and 288,640 workers were sent by the Indonesian government, respectively (BNP2TKI 2020). In 2019, this number was 276,553, lower than that in 2018 but higher than that in 2017 (BNP2TKI 2020). The primary destination country of these migrants was Malaysia, followed by Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia.

Migration from Indonesia to Malaysia is not a new story. Rather, it is part of the dynamic interaction among people in the archipelago and of a continuation of past Indo-Malay relationships. Malaysia was a country of destination for certain Indonesian ethnic groups even before the colonial era. Under colonialism, three models of migration from Indonesia emerged, namely, “forced migration,” contract workers, and “spontaneous migration,” which supported colonial projects, including plantations and road construction (Hugo Reference Hugo1993). The British colonial government in Malaysia imported labourers from China and India, as well as from Indonesia.

Recent studies of migration in Southeast Asia and Malaysia have demonstrated a significant development, which was concomitant with the “migration transition” that took place in Malaysia decades ago, from being an exporter of migrants to becoming “a significant net labour importer” for both skilled and unskilled labours (Lim Reference Lim1996: 320). Studies have also investigated Indonesian migrants in Malaysia in terms of their cultural identities, labour market, interstate relationships between Indonesia and Malaysia (Clark and Pietch Reference Clark and Juliet2014), problems faced by undocumented Indonesian migrant workers (Liow Reference Liow2003), government pressures on migration and border issues (Ford Reference Ford, Kaur and Metcalfe2006; Killias Reference Killias2018), the remittances sent home by migrants along with their economic contribution (Rahman and Fee Reference Rahman and Fee2009; Hernández-Coss et al. Reference Hernández-Coss2008) and other issues, including gender inequality, citizenship, and ethnic identity.

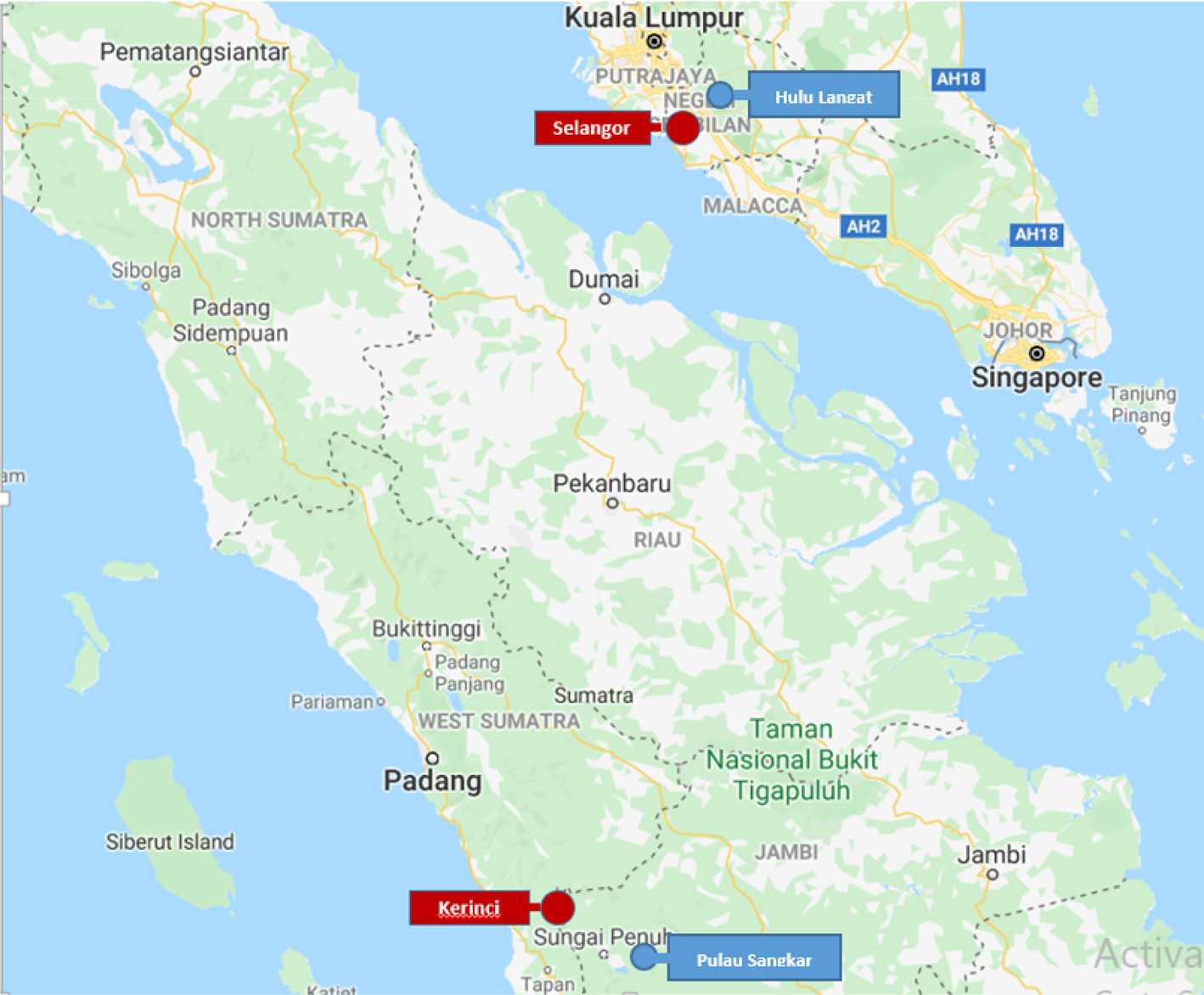

This paper examines the narratives of Indonesian migrants from the regency of Kerinci, Sumatra, living in the state of Selangor, Malaysia. It takes a closer look at the lives of three generations of migrants from the village of Pulau Sangkar in the regency of Kerinci who are living in the district of Hulu Langat in Selangor by exploring their experiences as members of the Kerinci (or Malay) ethnic group in Malaysia, the factors that encouraged their emigration from Pulau Sangkar to Malaysia and their decision to settle in Hulu Langat. Their narratives can help develop an understanding of migration and citizenship and indicate how these migrants have come to terms with their new identity as Malaysians, as well as their longing for the culture and memories they associate with their home (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Fox1994; Koh Reference Koh2015). The research questions are as follows. What stories have brought these Kerinci people to Malaysia? How has the migration led to their effort to reconnect with family, preserve family assets, and maintain their ethnic boundaries?

This case study focuses on Kerinci communities in the district of Hulu Langat in the state of Selangor, Malaysia, which is inhabited largely by Kerinci from Pulau Sangkar. Fieldwork was conducted in Hulu Langat and Pulau Sangkar in 2016 and 2017 to trace stories of at least three generations of Kerinci migrants. Pulau Sangkar is about 450 km from the city of Jambi in the province of Sumatra, and Hulu Langat is between Kuala Lumpur and Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia, and it is the largest district in Selangor.Footnote 1

Map 1. Kerinci and Selangor

(modified from Google Maps data)

Observations and interviews were used to gather data in both countries (Indonesia and Malaysia). The researchers conducted participant observation, taking part in religious gatherings, weddings and cultural events in Hulu Langat, where they spoke with second-, third- and fourth-generation of Kerinci migrants; all of the representatives of the first generation were no longer living. During fieldwork in 2017, we were lucky enough to be able to speak with the only person from the second generation who was still alive, 90 years old at that time. She died in 2019.

In-depth interviews were conducted with six informants from the third generation. Some of them are Kerinci-born migrants who remained in Hulu Langat to inherit their parents’ or grandparents’ property. In Pulau Sangkar, interviews were conducted with six former migrants who were living in Kerinci after many decades in Malaysia. They had acquired assets in Hulu Langat in the form of land and dwellings, which are now being managed by their children. The remaining data were collected from observation and informal conversations with other Kerinci, including some teenagers who were born in Malaysia to Kerinci families and represented the fourth generation. Pseudonyms are used here to protect informant privacy. The migrants in Malaysia shared various stories of how and why they decided to reside in Malaysia. Here, a migrant is considered not only in relation to seeking work, but also in terms of a destiny, so to speak. In this, politics, religion, economy, brotherhood and kinship are intermingled, shaping cause of migration and constructing a new identity for the Kerinci migrants. Here, “migrant decision-making” is not always considered to be “straightforward and linear”, as “emotions and non-economic factors” play crucial roles in motivating people to migrate and acquire a particular residency status (Koh Reference Koh2015).

Migration and Ethnic (Re)Construction

Migration has been part of the vibrant mobility of human civilisation for centuries. The dynamics of international migrations during the twenty-first century have had a profound impact on the variety of studies of migrants and migrations for observers and policymakers. In the European and Asian contexts, the debate over migration has only increased as migrations have led to a wide range of problems that arose in many countries related to security, racial division issues, ethnic identity, integration, settlement and economic stability. In the post-colonial geopolitical context, the presence of large numbers of Muslim migrants in the United States, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, to name but a few, has received widespread scholarly attention. The rise of hostile anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant sentiment due to religious and cultural differences (Becker-Cantarino Reference Becker-Cantarino2012: 6), the widespread negative understanding of migrant culture and the stigmatisation of minority religions and races have “led to what has been called the exaggerated securitisation” of illegal migrants (Liow Reference Liow2003: 44) and a “governmentality” of migration (Kaya Reference Kaya2009: 8; Kneebone Reference Kneebone2010). In many countries, migration policies have become characterised by changes in border controls, citizenship regulations and integration of policies to shape patterns in dominant identity (Dickinson Reference Dickinson2017; Kaya Reference Kaya2009; Morris-Suzuki Reference Morris-Suzuki2010; Spaan, Naerssen, and Kohl Reference Spaan, van Naerssen and Gerard2002).

Migration also has a profound impact on identity and the sense of belonging among migrants. As minority groups, migrants have adopted a range of strategies to survive and become integrated with the dominant groups where they live. Kerinci migrants and native Malay have a similar ethnic culture, and thus, they may avoid what the scholars such as Barth (Reference Barth1998) and Nagata (Reference Nagata1974) have termed “ethnic bondaries”. However, living as “transitory residents,” these migrants must cope with social, economic and political contexts where they may not quickly integrate with local residents or, to borrow Davidson's expression, where the migrants must “negotiate a feeling of belonging based on their perceptions and memories of their social situations” (Davidson Reference Davidson, Eng and Davidson2008; see also Varjonen et al. Reference Varjonen, Linda and Inga2013).

Inside migrant communities in this study, their long residence overseas has led them to develop a strategy to maintain their values and identity, including religion, customs, and arts in places where they are currently living by, in Madsen and Naerssen's expression, “carrying home and making home” (Reference Madsen and van Naerssen2003: 68). The cultural proximity between Kerinci migrants and Malays cannot guarantee smooth cultural negotiation to (re)construct identity. Plüss, who studied three ethnic groups among Indian migrants in Hong Kong argues that the ability of her subjects “to negotiate positions in networks with the majorities did not primarily depend on the degree to which the minorities adapted to, or resisted assimilating, the characteristics of the majorities. Rather, it depended on the degree to which transregional cultural capital could be fruitfully embedded in essential identities” (Plüss Reference Plüss2005). Observing the lives and identities of Indonesian migrants in Malaysia, Lim argued that “ethnic similarity does not necessarily mean that immigrant workers will be readily welcomed by the host community” (Lim Reference Lim1996: 335). Migrant workers thus experience an “process of ethnicisation”, characterised by a stereotyped sense of the nationality. Loveband's work about Indonesian migrant workers in Hong Kong, Guinness’ observations of Indonesian migrants in Malaysia and Becker-Cantarino and Kaya's reporting on Muslim migrants in Europe made similar observations concerning the levels of cultural burden faced by migrants due to labelling and ethnicisation. In her findings, drawn from her research in Taiwan, Loveband argues that ethnicisation has led Indonesian women to be placed “in the most exploited positions in a segmented labour market”, which has resulted in “a situation of ‘double-exploitation’” (Loveband Reference Loveband, Hewison and Young2006: 86).

Other observers have also indicated that migrant identity can be in relation to multiculturalism. Debates over the necessity of integration and assimilation may be reinforced by policymakers. In the United States, Australia and European and Asian countries that are major recipients of migrant flows have been sites of such debates regarding pluralism, assimilation and integration (Madsen and Naerssen Reference Madsen and van Naerssen2003: 72–73). Undocumented migration, in particular, has been seen to relate to a surge of complexity in the interaction between migrants and host country citizens, the rise of anti-migrants, and increased prejudice or stigmatisation against migrants. Guinness's studies of Indonesian migrants in Johor Malaysia, for example, show that public complaint are rooted in the Malaysian response to negative sides of migration, such as criminality, the diseases of malaria and tuberculosis brought by the migrants, the spread of perceived deviant practices and a tendency to send money home country instead of spending in Malaysia (Guinness Reference Guinness1990: 126–127; Kassim Reference Kassim1997: 72–73). Likewise, in the study of Indonesian illegal migrants in Malaysia, Azizah Kassim argues the following:

Many Malays, afraid of the competition from them, have started to call for their repatriation; they are also unwilling to share the rights enjoyed under the special position of the Bumiputra with the Indonesians or their descendants. If the illegals are not repatriated there is a possibility that a new ethnic group will emerge among Malaysians. The presence of other illegal aliens, such as those from the Philippines (except for those in Sabah), Bangladesh, India, and Myanmar, is not politicised. This is primarily because their number is relatively small and they do not share cultural similarities with the Bumiputra and are not, therefore, expected to assimilate with the latter. This category of aliens is generally regarded as transient workers who will eventually return to their own countries. (Kassim Reference Kassim1997: 75)

The question of the preservation of ethnic identity among migrants cannot be detached from the cultural and political contexts where they reside. Kassim and Guinness's research has resonances with the situation of Kerinci migrants, both in those of the third and fourth generation, as well as in those who came to Malaysia following the formation of the nation-state, especially those who become migrant workers during the period from the 1980s to the present. Recent data show a tradition of migration from certain regions of Indonesia, including Sumatra, West Java, East Java, Sulawesi, Kalimantan and West Nusa Tenggara, continues until the present. The number of Indonesian migrants living in Malaysia has also increased over time. In 2017, the Indonesian government reported that there were 2.5 million Indonesian migrants in Malaysia working in both the formal and informal sectors. Some of these arrived illegally for economic reasons, seeking jobs. Indonesian migrants in Malaysia have contributed to the development of Indonesia through remittances, but some have encountered challenges in their host country and have had bitter experiences, including exploitation and humiliation (Liow Reference Liow2003; Maksum and Surwandono Reference Maksum and Surwandono2017).

Narratives of Migration among the Kerinci

Indonesia and Malaysia are neighbours that had close interaction and population interchange over the course of centuries. Migration has characterised Malay society in the Indonesia–Malay archipelago. A long time ago, before the establishment of the modern nation-state, inter-kingdom relationships in the Malay world tended to strengthen ties for trading and diplomacy, along with religious interchange (Andaya and Andaya Reference Andaya and Leonard Y.1982; Clark and Pietsch Reference Clark and Juliet2014; Reid Reference Reid1988). Migration from Sumatra to the Malay Peninsula began centuries ago, pioneered by certain ethnic groups that developed a great tradition of migration, including the Minangkabau from West Sumatra and the Bugis from South Sulawesi. Minangkabau have been settling in Malaysia since the 1400s (de Jong Reference De Jong1980), followed by Bugis people (Sulawesi) in the 1700s (Bahrin Reference Bahrin1964, Reference Bahrin1967). Javanese groups then followed in 1880–1940, primarily moving to Selangor (Thamrin Reference Thamrin1985).

More than 150 years ago, Kerinci migrated to and built settlements in Malaysia. The first of these settlements was called “Kampong Kerinci,” and then was renamed “Bangsar South” by the Malaysian government. It is located in the contemporary Kuala Lumpur. The history of “Kampong Kerinci” is related to the migration of people from Sumatra, especially the Jambi, Aceh and Minangkabau, between 1901 and 1911 (Wandi Reference Wandi1992: 12). The Kerinci are a sub-Malay ethnic group from Jambi, the central highland area of Sumatra. The main source of livelihood in Kerinci is farming of rice and other crops, influenced by migrants from Minangkabau in West Sumatra (Burgers 2008; Zainuddin Reference Zainuddin2013).

In 2010, 1169 migrant workers were sent from Jambi, according to the Jambi Province Department of Finance, Public Works and Transmigration. As shown in Figure 1 below, although the number of Kerinci migrating to Malaysia significantly decreased after 2010, the number of migrants from Kerinci to Malaysia was above 200 each year for the following five years (2011–2015). This means that Kerinci was a main contributor to the number of Indonesian migrants in Malaysia. In relation to this, recent issues and development of Kerinci migrants in Malaysia can be established.

Figure 1. Number of Migrants from Kerinci to Malaysia 2010–2015

Sources: Modified from date presentation of the Department of Social, Public Works and Transmigration of Jambi Province

Our observations and interviews with Kerinci migrants and ex-migrants suggest that in the first decade of the twentieth century, some Kerinci made a series of journeys from the Sumatran highland to the Malay Peninsula for variety of reasons, including transit for the Hajj (pilgrimage), to start a new life, to establish a new settlement, escape from Dutch colonialism and to seek work. Selangor hosts several Kerinci settlements. These settlements were founded by migrants of different villages; it has been observed that it was common for migrants from one town in Kerinci to join together to make a new settlement. Many Kerinci migrants from Pulau Sangkar now reside in Hulu Langat, Selangor. Additionally, Kerinci migrants from other villages, including Jujun, Ambai and Keluru, occupy the Batu-14 area. Not far from there are settlements inhabited by Kerinci from the villages of Lolo and Pulau Pandan. Kerinci from the village of Tarutung inhabit the Batu-18 Simpang Pansun area, and the majority of those who come from Sumerap village live upstream of Batu-18.

The ideas of Malayness among Kerinci migrants does not always match with the idea of Malayness expressed in Malaysia or Singapore. Although this idea of Malayness has shifted from its exclusive meaning, “those of royal or noble descent” (Al Azhar Reference Al Azhar1997: 765), to a more inclusive sense of “Malay-speaking Muslims residing in the Peninsula and offshore islands” (Al Azhar Reference Al Azhar1997: 875; Andaya and Andaya Reference Andaya and Leonard Y.1982; Derks Reference Derks1997), the negotiation and construction of Indonesia/Malay/Muslim identity remains in process. This is part of the lived experience of Kerinci migrants who have experienced either “the settler model”, meaning “gradually integrated into economic and social relations, re-united or formed families and eventually became assimilated into the host society,” or “the temporary migration model” which refers to those who “stayed in the host country for a limited period and maintained their affiliation with their country of origin” (Castles Reference Castles2002: 1143–1144). Here, we may consider what Nagata's proposition has argued: “From the point of view of Malaysian society as a whole, then, there is clearly no universal or convergent assimilation process taking place, nor is there any consensus as to what kind of Malaysian should or will eventually emerge from the three major and other ethnic communities of which the population is composed” (Nagata Reference Nagata1974). The experience of the Kerinci migrants discussed in this paper is shaped within the dynamic of social, cultural and economic contexts in Malaysia, as indicated above.

Interviews with Kerinci migrants led the researchers to develop a range of narratives within the Kerinci migrants in Hulu Langat, Malaysia. The first generation of Kerinci in Hulu Langat has already passed away. This group crossed the sea to reach the Malay Peninsula after the arrival of the Dutch colonists in Jambi-Sumatra in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Locher-Scholten Reference Locher-Scholten2004). The descendants of the first generation reported that the motives that led the migrants to leave Pulau Sangkar included avoiding colonialism, to perform the Hajj and to start a new life. When they arrived in the new land in the Malay Peninsula, most became farmers. Before the era of the modern nation-state, the migrants could obtain land from the Sultan or provided by the colonial government.

For many years after the arrival of the Kerinci in Malaysia, migrants from several villages in Kerinci departed to Malaysia, worked as farmers and occupied land. In recent times, it has become evident that Kerinci in Malaysia are distributed according to their home villages in Kerinci. For example, the areas from Hulu Langat to Lui are inhabited by Kerinci from the villages of Pulau Sangkar, Jujun, Semerap, Seleman and Tanjung Tanah. Kerinci migrants from the villages of Sungai Penuh village and Pondok Tinggi are mostly in Kampong Kerinci, which is now located in central Kuala Lumpur.

The elderly woman Khadijah (like all informants, this is a pseudonym), the only survivor from the second generation (90 years old during the interview) provided information on the first motives of the earliest generations for coming to Malaysia. Khadijah was instrumental for providing us information on the first generation of migrants and on her contemporaries, the second generation of Kerinci migrants living in Hulu Langat. Khadijah was taken by her mother to Malaysia when she was a girl. When her parents returned home, Khadijah remained behind because she was married to a man from Pulau Pandan (another village in Kerinci) who was living in Malaysia. They married in Singapore and lived there for a long time. Khadijah had sixteen children from two husbands. At the time of the interview was conducted, eleven were still alive. She said, ‘I married a man from Pulau Pandan. We were married in Singapore. I came back from Singapore, I returned to Hulu Langat Selangor [instead of Pulau Sangkar Kerinci—authors] because my husband occupied lands here. It is difficult to return to Kerinci’ (Interview with Khadijah in 2017 in Hulu Langat).

Khadijah told us about Haji Akram from the first generation, who moved to Malaysia in the second decade of the twentieth century. After returning from Mecca, he took his son and his eight-year-old niece to Malaysia. There, he became a successful farmer. When he died, after many years, he left an inheritance in Hulu Langat in the form of land. This land was inherited by his son and then by his grandchildren, who are now still alive in Hulu Langat, Malaysia (Interview with Khadijah in 2017 in Hulu Langat). These stories suggest that the preservation of land and property by the subsequent generation was an essential issue that motivated the second and third generations to remain stay in Hulu Langat.

Performing the Hajj, one of the five pillars of Islam, is an essential motivating factor for overseas travel among Muslim communities in many parts of the world. Some stories of Kerinci migrants show a relation to the Hajj, such as being stranded in Malaysia on the way to Mecca or deciding to stay in Malaysia after returning from Mecca via Malaysia. It should be noted that in the early twentieth century and even until the 1970s, it has been difficult for people from Kerinci to return to their hometowns after a long journey overseas, including for the Hajj. According to Khadijah and informants from the third generation, the presence of Kerinci people in Malaysia in general is related to the pilgrimage. The story of Haji Darul indicates that economics are not the sole motive for his presence in Malaysia. The story told by his grandchildren indicates that Haji Darul was stranded in Malaysia on his way to Mecca for the Hajj. While in Malaysia, he became separated from his friends and brothers. His brother died en route to the Holy Land, and so did some of his friends. Haji Darul remained in Malaysia and decided not to return home (Interview with Khadijah and Jusuf, 70 years old in 2017 in Hulu Langat).

The descendants of these early settlers followed the path of the first generation and settled in Malaysia. The second and third generations were reconnecting with family as well as attempting to preserve the property owned by the first generation. One second-generation migrant was Zenabid, who spent his old age and died in Malaysia. Zenabid returned to Kerinci after Indonesian independence after remaining for a few years in Hulu Langat. In his hometown, he opened a lapau (grocery store), and some of his children were born in Pulau Sangkar at that time. Later, after Malaysian gained independence from the British colonialism in 1957, Zenabid returned to Malaysia to manage the property of his father (first generation) who was still in Hulu Langat (interview with Jusuf in 2017 in Hulu Langat). Zenabid's father died in Pulau Sangkar (Kerinci), and Zenabid spent the rest of his life in Malaysia. Here, the first generation of migrants opened the gate to settlement in Malaysia and then returned to homes in Kerinci, but the second and third generations worked to preserve their inheritance from the first generation.

Pradervis is another Kerinci from the second generation of migrants from Pulau Sangkar who settled in Hulu Langat. He was born and completed his primary education in Hulu Langat. His father, Hangtuao, lived in Malaysia for a long period. After Indonesian independence, Pradervis returned to Indonesia and continued his education in Padang Panjang, West Sumatra. Although Pradervis had returned to Kerinci, he frequently visited Malaysia. In Hulu Langat, his parents had acquired some assets, largely in the form of land. Unlike Zenabid, who spent his old age in Malaysia, Pradervis spent retired and died in his home of Pulau Sangkar (interview with Safar, Pradervis's son, in 2017 in Hulu Langat). Safar, one of Pradervis's children, continued in his footsteps by living in Hulu Langat until the present to ensure the property owned and inherited by his parents and grandparents will be preserved.

It should be noted that in the late 1940s, most migrants from Pulau Sangkar in Malaysia had returned to Kerinci. Indonesia's independence eliminated colonialist pressure throughout the country. Economic conditions in Kerinci improved greatly after independence. However, the prices of core commodities, such as rubber, cinnamon and coffee, were quite high, So, from the era of independence until the 1970s, there were not many people from Pulau Sangkar who migrated to Malaysia until the 1970s. Here, the deteriorating relationship and political confrontation between Indonesia and Malaysia in the 1960s should be noted as a factor, although not the most significant, in the lack of migration from Indonesia to Malaysia.

In the early 1980s, people from Pulau Sangkar began to return to Malaysia. They sought and re-established ties with family members who had been living in Malaysia for many years. From that era until the present, economic motives guided migration. During that decade, Kerinci also experienced an economic downturn. Thus, people from Pulau Sangkar who came to Malaysia in the 1980s largely settled in the houses of the second generation of migrants. Some of the new group of migrants had a genealogical relation to the second generation, so they inherited land in Hulu Langat. In 1984, for example, 13 new Pulau Sangkar migrants, constituting a third generation, entered and remained for long time in Malaysia (Interview with Jusuf in 2016). In 1996–2000, around 50 people from Pulau Sangkar Kerinci, both young and old, were resident in Malaysia.

The Hulu Langat became the base for a gathering of Kerinci. Our informants indicated that Hulu Langat would become the home for people from Pulau Sangkar who come to Malaysia in the future (Interview Safar and Marwadi in 2016 in Hulu Langat). When migrants from Pulau Sangkar have arrived in Malaysia seeking work, they have frequently visited Hulu Langat on the weekend to preserve their connection with members of their ethnic group whose ancestors are from the same village in Kerinci. Theoretically, a community may become integrated when its members experience a sense of belonging as a social group or collectivism based on mutually agreed-upon norms, values, and beliefs (Skrbiš et al. Reference Skrbiš, Baldassar and Poynting2007). Social integration implies social solidarity, which refers to a relationship based on moral conditions and shared beliefs, reinforced by their emotional experience. This bond is more fundamental than a contractual relationship developed through rational agreement (Johnson Reference Johnson1986: 181).

Ethnic Construction: Kerinci Language and Culture in Hulu Langat

The ethnic identity of migrants in Hulu Langat is well preserved in communities. Although the dominant Malay culture in Malaysia has many similarities with Kerinci traditions, efforts to present the uniqueness of Kerinci culture remains prevalent. As with migrants in other countries, who feel that they cannot be fully accepted by the dominant group in their host country, the sense of belonging of Kerinci migrants, including those who hold Malaysian citizenship, as seen in their behaviour, exhibit a sense of belonging to two cultures and nationalities (See Madsen and Naerssen Reference Madsen and van Naerssen2003: 68). This also is a form of preservation of the memories of their home in Kerinci (for comparison with Chinese migrants in Australia, see Davidson Reference Davidson, Eng and Davidson2008).

The Kerinci language remains the predominant language in Hulu Langat and its use has become an emblem of pride for them. In the area of Pansun Batu 18, for example, the local community speaks Malay with a Kerinci accent. Similarly, migrants from the village of Semerap have not changed their daily language. Thus, even though officially they are Malaysian citizens, they continue to feel that they are Kerinci. One informant told us that he once attempted to hold a conversation with a friend in Malay, but his friend protested in Kerinci, saying, “kayao kan uhang Kincay pio kayo lah beso Malaysia pulao” (sir, you are a Kerinci, why do you speak Malaysian?) (Interview Jusuf in 2016 in Pulau Sangkar).

People from Jujun also consistently use Kerinci in everyday conversation. In the Batu 13 Hulu Langat, many people speak Kerinci. Their parents are of the second generation that entered Malaysia before the independence of Indonesia. They remain proud to be descendants of the Kerinci. In their third generation, Jujun people, even those were born in Malaysia, still communicate in Bahasa Kerinci. In one interview, an informant spoke to his wife in Malay because his wife is a Malaysian, but he communicated with the researchers in Bahasa Kerinci. Although this informant was born and raised in Malaysia, he was still fluent in Bahasa Kerinci. The preservation of language remains paramount among Kerinci groups in Malaysia and is part of how they preserve their cultural identity as Kerinci.

Although Kerinci have lived in Malaysia for an extended period, they still love Kerinci culture. One place where Kerinci culture, such as music and songs, is preserved is the Ethnic Bamboo Art Studio. Here, almost every weekend, dozens of Kerinci gather to share stories, sing, and dance. They sing the Tale (Bertale) of KerinciFootnote 2 and perform Rangguk of Kerinci.Footnote 3 The performing arts are also a means of relieving stress. Previously, they gathered to sing and talk because they did not have enough to eat. Their incomes depend on the presence or absence of work. Therefore, this studio was necessary for them to get by. An informant said, “we are happy here, the presence of Bertale and Merangguk and this routine activity in the Ethnic Bamboo Studio relieve us from hunger and stress” (Interview with Deni in Hulu Langat in 2016).

Thus, these Kerinci, who identify as Malaysian citizens, remain culturally tied to the Kerinci. Their identity as Kerinci remains still alive. Where there was a Kerinci cultural event where songs and dances from Rantak Kudo were performed, Kerinci arrived, with or without invitation. When the nephew of one of our informants got married, the venue was filled with Kerinci migrants from many places. The presence of Kerinci migrants at cultural events and even at private parties is motivated by a sense of belonging as Kerinci. At this wedding, they sang Rantak Kudo song together (Interview with Bawahid in 2016 in Pulau Sangkar). The researchers also noted an atmosphere of Kerinci culture in Hulu Langat. When they visited the Ethnic Bamboo Studio in Batu 13, many from the Kerinci community in Hulu Langat heard of their arrival and held a welcome ceremony. Girls and young women performed the Rangguk dance, and they sang Rideak Rile, a compulsory song for Kerinci wherever they are. The presence of the Bamboo Ethnic Studio as a venue for regular cultural performances by Kerinci helps preserve their ethnic distinction, develop their social system, and intensify their interactions. To borrow from Barth, “ethnic distinctions do not depend on an absence of social interaction and acceptance, but are quite to the contrary often the very foundations on which embracing social systems are built” (Barth Reference Barth1998: 10).

Picture 1. Kerinci party in Hulu Langat, Malaysia 2017

(Photo: Mahli Zainuddin's collection)

Kerinci culture draws the Kerinci closer to Malaysian society. Thanks to its similarities to Malay culture, it has received recognition from Malaysian society as a whole, including from the government. For instance, the studio was built with permission from the government. Kerinci cultural groups are sometimes invited by the Malaysian government to perform to entertain visiting officials and other guests from Indonesia. Some Malaysians have also sought to experience customary Kerinci weddings. Many local people also attend traditional Kerinci weddings to learn how little different Kerinci marriage customs are from Malay ones.

It is claimed that the arrival of the Kerinci people in the 1970s-1980s has also strengthened the practice of Islam in Hulu Langat. According to an informant, when he first came to Hulu Langat, many villagers did not fast. Although the official religion of Malaysia was Islam, religious life in the community was beginning to decline. After the arrival of the Kerinci group, some of them are knowledgeble about Islam and Qur'anic recitation, spiritual life in Hulu Langat began to improve. Local people started fasting and intensifying Qur'anic recitation. A study group was formed by migrants; members of the local community, especially earlier migrants, joined the study group (Interview Jusuf in 2016). The preservation of Kerinci identity, culture and tradition, including traditional Kerinci dances and Malay songs, is not only an indicator of assimilation but also of the reconnection between inter-generation immigrant groups to maintain memories of Malayness as Kerinci people overseas (see also Becker-Cantarino Reference Becker-Cantarino2012: 7; Taylor Reference Taylor2013).

The Hulu Langat district features extensive settlement by Kerinci migrants from Pulau Sangkar due to its geographical condition, which if similar to that of Pulau Sangkar. For these people, the experience of arriving in Hulu Langat from Kuala Lumpur is felt to be similar to arriving in Pulau Sangkar from Sungai Penuh, the capital of Kerinci Regency. On the left and right sides of the road, there are verdant hills. In 1983, there were only around 30 houses there, erected by Kerinci people from Pulau Pandan, Jujun and especially Pulau Sangkar.

In Hulu Langat, some continued their old hobby of river fishing. One of our informants at Kerinci had this hobby, which he continued in Hulu Langat. He visited many places in Hulu Langat, such as Ayik Semungkih, Batang Langat and Sungai Lung, just for fishing. For some migrants, fishing and diving became side jobs. Our informant reported, ‘The river in Malaysia is familiar to me. My net is still there too. The net that I have is a balanced mesh. I give other types of nets to friends’ (Interview with Umar in 2016 in Pulau Sangkar). The similarities in topography between Hulu Langat and Pulau Sangkar also confirm that the first and second generations were not simply motivated by the economy or employment. They moved from one village to another to become farmers, unlike more recent generations, who moved from small villages in Indonesia to work in large cities in Malaysia.

The pictures below (Pictures 2, 3, and 4) show the topographical similarities between Hulu Langat and Pulau Sangkar. Both are highlands filled with major rivers that have been sources of life for decades. A river means a great deal for people living in rural areas like Pulau Sangkar. People rely on rivers, which provide waters for their paddies, sanitation and transportation. The green and hilly areas in Hulu Langat surrounding the rivers and villages brings a sense of happiness to the migrants, as if they were close to Pulau Sangkar. Those who live in the hinterlands of Sumatra and then moving to large Malaysian cities for work, viewing the topography of Hulu Langat during the weekend conveys memories of their hoes.

Picture 2. River in Pulau Sangkar, Kerinci

(Source: Mahli Zainuddin's collection)

Picture 3. Pulau Sangkar, Kerinci

(Photo: Mahli Zainuddin's collection)

The social integration of the Kerinci in Malaysia is also intertwined with their sense of belonging as a social group functioning through the norms, values, and beliefs as Kerinci. The social integration of the Kerinci in Malaysia relates closely to social solidarity and normative integration, which go beyond contractual relations. Their values, norms and beliefs as Kerinci are concretely embedded in their shared language and culture. The Kerinci have created a new cultural enclave in Malaysia. This integration is strengthened in the topography of the area, which is similar to that of their hometown in Kerinci. The combination of these elements makes Kerinci living in Hulu Langat feel as if at home.

Being at ‘the Crossroads’: Citizenship and Sense of Belonging

“I was born here, and I grew up in this village. My family and all my friends also live here. I was unfortunate in that I could not enrol in a state college because of my mother's citizenship. But I would continue to live here, to serve as a Malaysian citizen.” (young Malaysian of the Kerinci ethnic group)

“I came to Malaysia when I was a kid with my uncle to inherit the property of my grandparents who came here decades ago. I finally found a job here. I feel just like a Malaysian, even though I had Indonesian citizenship until now. If Malaysia is criticised by—or in conflict with other countries—I will defend this country.” (male Kerinci migrant in Malaysia)

In the first quotation above, a Malaysian child of the last Kerinci-born generation expresses his opinion about being a migrant's child. His parents come from Pulau Sangkar. He was living in the dormitory of a private university near Kuala Lumpur, and his parents were in a Kerinci ethnic enclave in Hulu Langat. In the second quotation, an Indonesian migrant from Kerinci who has lived and worked for many years in Malaysia shares a different experience, reflecting on his sense of belonging in the Malaysian state. These experiences indicate a range of narratives constructed by Indonesian migrants from Kerinci Sumatra living in Hulu Langat.

Unlike members of the first and second generations, who may not have encountered many difficulties regarding citizenship, the third and fourth generations have been faced with the complex realities of migration in the era of the nation-state. Not all Kerinci people are now able to smoothly cross the border and remain in Malaysia because migration regulations have been strengthened. Similar to neighbouring countries in many parts of the world, borders have become an essential spot for the challenges of migration and immigration security. Due to the complexity of migration in Malaysia, the government of Malaysia has two policy models: strengthening migration and regulation and “spasmodic efforts” to arrest and deport many illegal migrants while also creating a framework to legalise undocumented workers by issuing red (residents’) identity cards (Guinness Reference Guinness1990: 127). The presence of undocumented migrant workers, or orang kosong, has had profound legal and political ramifications in the Malaysian context, including on working-permits and citizenship (Ford Reference Ford, Kaur and Metcalfe2006; Kassim Reference Kassim1987).

An informant with a red identity card (for permanent residents) reported not wanting to receive a green one (a temporary ID). That is, he preferred to remain an Indonesian citizen while enjoying a long, comfortable stay in Malaysia. His red card restricts him from political rights in Malaysia, and he cannot get a bank loan. His official status rides of that of his child. However, he also showed a commitment to defend Malaysia from threats. He said, “We are residents here, fellow Muslims are still one family. We sit in a family home that has a conflict with its neighbour, so we help our family” (Interview Safar in 2016 in Hulu Langat). As Sin Ye Koh has argued in her studies on temporalities of citizenship, “migration and citizenship decisions can be good reflections of the changing conditions in the origin and host locations” (Koh Reference Koh2015: 6), and migrants have always attempted to negotiate their citizenship together with their feelings and experiences in the host country, along with their sense of belonging to their country of origin.

Some people seemed to be at the intersection of seeking to live in Malaysia and those who return home to Kerinci. Many had children in Malaysia but still wanted to return and retire in Kerinci. They had red cards, enabling them to travel in and out of Malaysia whenever they wished. Those with a blue card or who wished to become Malaysian citizens require a visa when returning to Kerinci. As Malaysian citizens, however, they are entitled to assistance from the Malaysian government. The Kerinci who built homes in Hulu Langat generally held blue cards.

One informant who held a red card felt economically more secure in Hulu Langat than in Kerinci. However, all his family members were in Kerinci. He worked in Malaysia to financially support his family in Kerinci. Bringing his family would be difficult for him due to financial requirements. Although many Kerinci people build houses in Hulu Langat Selangor, some migrants do not wish to do so because their children and grandchildren live in Indonesia. In Hulu Langat, the informant simply occupied a house constructed by his ancestors. He stated that one day he would return to Kerinci. In the meantime, he had to be separated geographically from his family for a long time (Interview with Safar in 2016).

Other informants who held the red card chose not to change their citizenship and take a blue card, even though it was possible to do so. For them, although lived in Hulu Langat for decades and had children and grandchildren there, they could not forget Kerinci. They reported hoping to return to Pulau Sangkar someday. They wanted to retire in their hometown. One informant said, “We are here only as migrants. No matter how far as the stork flies, it will always return to its puddle. For our children, they will make their own decision” (Interview with Safar in 2017). Some of them admitted that from an economic standpoint, their lives in Malaysia were better than those at home. However, Kerinci would always remain their home, no matter what the condition. For one informant, being in Malaysia was only an economic problem. By migrating to Malaysia, he could buy land in three locations in Hulu Langat, so that when he returned to Kerinci later, his children would be safe in Malaysia. One elderly informant told the researchers that he lacked tertiary education, but he would go anywhere for economic reasons. He felt like a bird that was flying anywhere in search of a place with plenty of yellow rice that would return to the nest after eating the rice. This principle was not supported by his friend who had become a Malaysian citizen; he said, in a sarcastic tone, “You are not good; you eat here but defecate in your hometown” (Interview with Safar in 2017 in Hulu Langat).

The latest generation of Kerinci migrants were at a crossroads. One informant was a young man born in Malaysia to parents from Kerinci. He was a student of one of the universities in Selangor and identified as Kerinci, but he could not speak it. He could not dance Rangguk or sing Kerinci songs, and he was not familiar with the Ethnic Bamboo Studio. At home in Hulu Langat, he generally remained at home, not passing time with his friends, because he was at home only on Sundays.

Unlike his parents, he felt like a full citizen of Hulu Langat. He and his siblings have blue cards, making them Malaysian citizens. He confessed that he was disappointed with the government because despite holding the Blue IC, he could not enter a state university. He could enrol in private universities or state universities but only for diploma programs, partly because both of his parents still hold red cards. If one of his parents had a blue card, he would be able to enter a public university. The fate of his niece is better. Although born as a child of Kerinci parents, the niece was considered a native of Malaysia so she was entitled to a scholarship from the government and could study at a public university.

He was disappointed that he was not considered a Malaysian native. He was born and raised in Hulu Langat. His entire education, from the elementary level to higher education, were all conducted in Malaysia. But he could not enroll in a public university because his parents were Indonesian citizens. Even sadder for him was the fate of his very accomplished brother, who, despite his perfect grades in school, could not go to a public university because of his Indonesian parents. Even so, the informant said, “I will remain in Hulu Langat because my friends and childhood are here” (Interview with Syafira, son of Safar, in 2017). Under these circumstances, citizenship is an essential issue for migrant workers. It is part of self-identification and belonging among migrants, personally or collectively. Although Malaysia can provide better incomes and improve migrants’ wellbeing, becoming a Malaysian citizen, as reflected in the experience of the second and third generation, is not the choice of all. However, the younger generations expect a different destiny from that of their parents because they desire a clearer citizenship status of citizenship, wishing not to become what Becker-Cantarino (Reference Becker-Cantarino2012: 32) called, “a migrant without a homeland.”

Conclusion

This study investigated ethnic identity among Kerinci migrants living in Malaysia. As has been found in other migration studies, Kerinci migrants have formed a kind of cultural process of negotiating their cultural identity within the dominant society and of preserving their ethnic identity through demonstrating cultural uniqueness. Although four generations of Kerinci migrants have lived in Malaysia for almost 100 years, efforts maintenance of cultural differences among the members of their community continue in cultural events. Ethnic identification has preserved their distinct identity in the novel Malay world in which they are living. Although they face ethnic boundaries in Malaysia's new ecological context, attempts to negotiate and restore their Sumatran origins and to maintain ethnic boundaries among Kerinci migrants continue to predominate. As Fredrik Barth suggested, “ethnic groups only exist as significant units if they mean marked behavioral differences.” In this sense, “persisting cultural differences,” can, exemplified in various activities, be a way for an ethnic group to maintain “a connection or a community of culture” (Barth Reference Barth1998: 16).

The continuance of ethnic identification among migrants was supported by economic and primary motives, such as finding jobs, joining family members and preserving ancestral lands. For the Kerinci and perhaps others, arrival in Malaysia has not meant earning cash, and the influence of Kerinci culture also persists. The creation of a Malay identity among the Kerinci is part of their negotiation with economic needs, including their current work, the protection of inherited property and their future lives. The experiences of four generations of Kerinci migrants in Malaysia have shown that the presence of settlement among the Kerinci that we discovered in Hulu Langat, has a profound impact on the preservation of ethnic identity. To borrow from Parenti's study of ethnic identification in the multicultural society of the United States, ‘In the face of widespread acculturation, the minority still maintained a social sub-structure encompassing primary and secondary group relations composed essentially of fellow ethnics’ (Parenti Reference Parenti1967: 719). A settlement or village overseas can function not only as a place where people of one ethnic background can stay and interact but also as a place where ancestral cultural traditions and a memory of a hometown or country of origin can be preserved. The use of Kerinci in daily conversation and the continuation of past lifestyles (such as fishing and diving) represents the connection of migrants’ memories in a new ecological environment to their hometown. Settlements and cultural events can intensify and transform a society. As Barth noted, ‘the persistence of ethnic groups in contact implies not only identification criteria and signals but also structuring of interaction that allows cultural differences to persist’ (Barth Reference Barth1998: 16). Migration can also imply family reunification and reintegration among the Kerinci. From ethnic identification, the reunification of a large family among migrants also means preserving boundaries and functioning to fulfill duties as a new generation to protect their ancestors’ legacy.