Published literature often presents the Nigeria–Biafra War (1967–1970) as marking a ‘before and after’ in the history of humanitarian aid.Footnote 1 Generally speaking, the founding of Médecins sans Frontières (Doctors without Borders, MSF) after this conflict has been put forward to justify this assertion, as has been the development of its new methods, breaking with a more traditional humanitarianism represented by the International Committee of the Red Cross. The political activism of these new humanitarian organisations, focused on speaking out and operating without borders, was the driving force behind the emergence of a new generation of humanitarian actors.Footnote 2 This interpretation is the key to understanding the subsequent positioning of these new humanitarian actors, and especially of MSF vis-à-vis the ICRC. However, the emphasis on this issue in the history of humanitarianism, especially in the analysis of the Nigeria–Biafra conflict, has been to the detriment of other developments of the time. This article aims at looking beyond this narrow focus on speaking out in order to chart the larger-scale shift in the humanitarian sector in the late 1960s. Among the factors that can shed new light on the practices of emergency relief organisations at the time, particularly those of the ICRC, are the increasing number of non-governmental organisations whose involvement was no longer limited to fundraising but now also extended to field operations, growing media coverage of humanitarian crises, and the post-colonial context in which aid operations were conducted.Footnote 3

For the ICRC, despite its experience in armed conflict, the Nigeria–Biafra war was in many ways a relatively new response scenario.Footnote 4 Studies of this period in the ICRC's history are few and far between,Footnote 5 but the literature generally agrees on the importance of this conflict.Footnote 6 Some go so far as to describe it as a turning point, as one former ICRC delegate remarked:

The modern ICRC was born in Africa, in the smoking ruins of Biafra in the late 1960s. This is where the new ICRC was brought to the baptismal font of a new humanitarian era, during the development of a huge rescue operation for hundreds of thousands of victims of the Nigerian civil war.Footnote 7

This view of the conflict raises questions about its impact on the way in which the ICRC functioned, especially since, as David Forsythe has explained, the organisation has generally been reluctant to accept change: ‘the ICRC embraced change only slowly, frequently when anticipated negative outcomes left little choice but to change’.Footnote 8 A book on the ICRC covering the 1945–1980 period also concluded that significant developments had taken place in the wake of the Biafra conflict, which transformed the ICRC's assistance policy.Footnote 9 This became increasingly oriented towards areas outside Europe, particularly in Africa and South America, and gained in magnitude. In addition, a jump in the ICRC's budget and workforce occurred during this period.Footnote 10 Finally, a restructuring got under way between 1970 and 1974, when the organisation was taking stock of its Nigeria–Biafra operation.Footnote 11

To understand the impact of the Nigeria–Biafra conflict, it is necessary to analyse the way in which it exposed the ICRC's weaknesses and prompted a process of reform. These weaknesses were particularly evident in three areas. First, the functioning of the organisation itself and its ability to manage a large-scale operation were called into question. Second, its interaction with other organisations and individuals – governments, other humanitarian agencies, and the media – also became subject to criticism. Third, the difficulties encountered by the ICRC in recruiting and training qualified staff were part and parcel of a new challenge: how to work more effectively in the field. In the face of these problems, the ICRC had to demonstrate flexibility and take the initiative in order to conduct such a complex operation.

The purpose of this article is therefore to understand how a series of emergency measures, affecting the ICRC's internal functioning and other aspects, fit into a wider reform process that profoundly re-shaped the ICRC in subsequent years. More generally, an analysis of this process reveals how changes in the internal structure of humanitarian organisations can be driven by action taken in the field. Even the relatively short time period covered here suffices to shed light not only on the principles underpinning the action of such organisations but also on how they function.Footnote 12

Operation Nigeria–Biafra: new challenges for the ICRC?

In the mid-1960s, the ICRC had not yet fully recovered from its difficulties at the end of World War II, when the fall in its activities led to a drastic reduction in its budget and workforce.Footnote 13 In addition, it had been heavily criticised for its failure to help the victims of the Nazi genocide and prisoners from the Eastern Front. Although the ICRC gradually managed to overcome these difficulties, the situation in the mid-1960s remained precarious. Between 1945 and 1965, it did carry out significant operations, but generally only ones requiring relatively limited resources. Indeed, in those conflicts in which it was called on to act, the ICRC focused mainly on its traditional tasks – that is to say, activities for detainees, whether prisoners of war or civilian internees, and supporting National Red Cross Societies in cases of disturbances. While the ICRC contributed to major relief operations for civilians, this was not its primary focus and required significant resources. In this respect, the operation that took place following the entry of Soviet troops into Hungary in 1956, in which the ICRC distributed food to Hungarian refugees in Vienna, was a notable case, accounting for a significant proportion of the aid distributed in the 1950–1960 period.Footnote 14 In several other cases, the ICRC mainly supported the work of National Red Cross Societies. In the Cyprus and Algeria conflicts, for example, it was involved in relief efforts for civilians alongside the British and French Red Cross Societies, but did not have primary responsibility for those operations. Whenever it looked like the ICRC would have to develop this type of activity, its policy was to try to off-load the responsibility onto others. This was particularly the case in the Congo, during the conflicts that erupted in the wake of independence in 1960. While ICRC delegates took initiatives to protect and assist civilians, they were not really supported by headquarters, which felt that the ICRC could not afford to get involved and that this task was the responsibility of other organisations such as the United Nations.Footnote 15 Overall, for the period up to the mid-1960s, Françoise Perret and François Bugnion describe how

[t]he ICRC, which did not have the means to match its policies, was reduced to matching its policies to its means. All too often, without adequate resources, it had to trim its programmes or cut short an operation while victims were still in need.Footnote 16

In the late 1960s, with more and more situations requiring the ICRC's attention, resources were stretched further. Alongside the Nigeria–Biafra operation, the ICRC had to deal with the Vietnam, Arab–Israeli and Yemen conflicts, as well as with Greek political prisoners. The end of the 1960s thus saw the ICRC stepping up its activities and operating in a wider range of settings.Footnote 17 It was no longer present in just Europe, the Middle East and Asia, but also in sub-Saharan Africa. Establishing the ICRC in sub-Saharan Africa posed quite a challenge. When several African states were declared independent in the early 1960s, the ICRC had to raise awareness of its work, which hitherto had been relatively limited. The African populations that had been victims of violence during colonisation were not initially considered by the ICRC to fall within its remit.Footnote 18 Thus its first real contact with sub-Saharan Africa was during the Italo-Ethiopian War.Footnote 19 Moreover, it was often when situations involved European victims that the ICRC took action. In 1960, when the ICRC became involved in the Congo, protecting the black population was not its primary concern at first, although some delegates took initiatives along those lines. ICRC delegates were first dispatched to help the white settlers, at the request of the Belgian and French Red Cross Societies, and ended up coordinating the establishment of Red Cross medical teams in the country. During the troubles that heralded or accompanied independence in Kenya, Rwanda, Burundi, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland, and South Africa, the ICRC dealt relatively little with the local population, about whom there were still very widespread prejudices at the time.Footnote 20 Some at the ICRC, however, felt that the organisation should establish activities in independent sub-Saharan Africa and raise the ICRC's profile in that part of the world. By appointing a delegate for Africa at the beginning of the 1960s,Footnote 21 the ICRC sought to improve its relationship with the newly independent states and to develop its activities there. Despite these initiatives, the ICRC was still not well known or experienced in the region when the Nigeria–Biafra War started.

In the summer of 1967, following the Republic of Biafra's proclamation of independence, the Federation of Nigeria took up arms to stop the secession.Footnote 22 The ICRC became involved in the war zone by offering its services to the belligerents. The first step was to inquire after the fate of prisoners of war and to support the activities of the local Red Cross by providing equipment and medical staff. At the end of 1967, the ICRC also started relief operations for civilians affected by the war on both sides of the front line. When famine took hold in Biafra in 1968, this became the organisation's main focus. The challenge was to feed a population of several million people in complex circumstances. For the ICRC, the main stumbling block was the difficulty of obtaining the consent of the belligerents to bring aid into Biafra, which was blockaded by the Nigerian government. While the government accepted the principle, it wanted control over what was delivered and how, in order to assert its sovereignty over the breakaway province. Conversely, the Biafran authorities tried to impose their own conditions on relief efforts in order to show that they were not subject to the whims of the federal government. In addition, for each belligerent, humanitarian aid was strongly linked with questions of military strategy.

Despite these difficulties, in September 1968, the ICRC was able to establish an airlift for Biafra. In accordance with the principle of impartiality, and to avoid operating only on the Biafran side, it also set up and coordinated a relief operation in the areas recaptured by the federal army, where it had to contend with major logistical problems. This operation lasted until the summer of 1969, at which time the Nigerian government took an increasingly hard line. The ICRC commissioner-general of the Nigeria–Biafra operation was declared persona non grata in Nigerian territory; an aircraft, part of the Red Cross airlift, was shot down; and the Nigerian government decided to take over the relief operation in federal territory. This change in attitude forced the ICRC to reconsider its involvement and, unable to negotiate an agreement between the belligerents, the organisation suspended the Biafra airlift. The second half of 1969 therefore saw the ICRC gradually winding down its activities in the conflict, although it pursued its traditional tasks and maintained its medical teams in Biafra. The surrender of Biafra in January 1970 put an end to humanitarian operations in Biafra.

The ICRC's assessment of its role in the war was mixed. It had conducted a large-scale operation, but had been forced to stop most of its activities before the conflict ended. It had been an expensive operation, requiring a large and highly trained workforce and rigorous management, particularly when it came to negotiating with the belligerents. This had quickly highlighted the need for the ICRC to undertake reforms if it wished to reaffirm its role as an organisation that assisted people affected by war. Three areas were central to this process: the functioning of the organisation, staff management, and the organisation's relationship with other humanitarian actors and the media.

Seeking direction

The scale of the Nigeria–Biafra operation, the largest the ICRC had carried out since the end of World War IIFootnote 23, and the new conditions in which it unfolded highlighted the amateurism of the ICRC's humanitarian response. There were two particularly acute problems. Firstly, there was a complex relationship between ICRC headquarters, where decisions were made, and the field, where other concerns held sway. Secondly, the unique functioning of the ICRC, with the central role played by the Committee (now the Assembly) in the decision-making process, raised issues specific to its organisational structure.Footnote 24

In 1967, when the Nigeria–Biafra conflict began, the Committee had 17 co-opted members,Footnote 25 who attended a plenary meeting once a month. They set the ICRC's policy and fixed its general direction. Alongside the Committee, the Presidential Council met more regularly every fortnight between each plenary session of the Committee and oversaw the everyday affairs of the organisation. It was composed of the president and two vice-presidents (elected by all the members), along with several other members of the ICRC. Finally, the Directorate, made up of two directors-general and a director, managed the ICRC's daily activities and administration. A critical evaluation of the way in which those bodies functioned at the end of 1967 brought to light several factors that might help explain the lack of initiative taken by the ICRC in pursuing its action.Footnote 26 Overall, the Committee members did not seem to be sufficiently committed to their duties. Despite receiving an internal briefing document that was produced specifically for them, they did not seem to pay enough attention or know enough about the issues. Being more dynamic also meant recruiting more diverse and younger Committee members, whose average age prior to the recruitment of four new members at the end of 1967 was 65. Moreover, the distinction between the Presidential Council and the Committee was not clear, and plenary meetings put too much emphasis on the details of the implementation of ICRC policy, which was actually the responsibility of the Presidential Council and the Directorate. Finally, there was a need to boost the Directorate by appointing one or more assistants.Footnote 27

While these problems were not linked specifically to the Nigeria–Biafra operation, they did have an impact on it. As a result, the ICRC was late to take charge of the operation. According to Thierry Hentsch, the initial difficulties encountered by the ICRC in the negotiations with the warring parties stemmed from a degree of insouciance.Footnote 28 The Nigeria–Biafra situation was initially not a subject of particular interest to the Committee. Uninformed about the situation, it relied primarily on information from Swiss diplomats stationed in Lagos, where it was widely believed that the federal army would swiftly overcome secessionist Biafra.Footnote 29 Within the ICRC, the conflict was not given due consideration, which caused the ICRC to mishandle its dealings with the Nigerian and Biafran authorities, sowing doubt in the minds of its contacts about ‘the credibility of its humanitarian, neutral and impartial action’.Footnote 30 Furthermore, the ICRC failed to give sufficient weight to its representations to the belligerents. It would have had more of an impact if it had sent a member of the Committee to the field.Footnote 31

With people's needs growing dramatically in the late spring of 1968, the ICRC made a public appeal entitled ‘SOS Biafra’, in which it advocated lifting the blockade imposed by the federal government. These efforts, made in haste and without informing the Nigerian government, only exacerbated the misunderstandings with the authorities.Footnote 32 The ICRC's amateurism not only hindered negotiations about the relief effort in Biafra, but also affected the management of the operation on Nigerian soil. With thousands of tonnes of aid sent by governments and organisations beginning to arrive in Lagos, the ICRC struggled to coordinate its distribution. (Fig. 1 & 2)

Figure 1. A DC4 in Geneva loading 6.5 tonnes of medicines and vitamins for Biafra via Santa Isabel, 27 May 1968. © ICRC photo library/V. Markevitch.

Figure 2. A convoy in the Nigeria–Biafra war. © ICRC photo library/Max Vaterlaus.

In Lagos, this provoked considerable criticism from the Nigerian authorities, British and American diplomats, and ICRC staff who complained about the organisation's handling of the situation.Footnote 33 The Swiss ambassador in Lagos was also concerned about the implications for the image of Switzerland and urged his superiors to entrust the operation to Swiss figures who could handle it. He wrote:

Möglicherweise bietet sich Ihnen doch eine Gelegenheit, mitzuhelfen, dass die IKRK die richtige Persönlichkeiten für die Nigeria-Aktion findet. Schliesslich steht indirekt auch der Ruf unseres Landes auf dem Spiel, dass die ganze Aktion unter schweizerischer Leitung durchgeführt werden muss. Es wäre in der Tat bedauerlich, wenn die Spenderstaaten und anderen Geberorganisationen den Eindruck bekommen sollten, dass die Schweizer der Aufgabe nicht gewachsen sind.Footnote 34

With images of malnourished children splashed across the Western media in July 1968, pressure mounted on the ICRC to find solutions and be more effective.Footnote 35 Afraid that the operation would be taken off its hands, the ICRC decided to entrust it to an outsider who was able to take charge.Footnote 36 It made a formal request to the Swiss Confederation to make the Swiss ambassador in Moscow, Auguste Lindt, available. Among other positions, the latter had been Special Delegate for the ICRC in Berlin and had served as UN High Commissioner for Refugees.Footnote 37 In July 1968, he was appointed commissioner-general for the Nigeria–Biafra operation, for which he had full responsibility. When it put Lindt at the disposal of the ICRC, the Swiss government specified that he must not be hindered in his actions by the Committee.

At first, his appointment appeared to be a success, since the Biafra relief effort was temporarily unblocked. A regular airlift was set up, carrying hundreds of tonnes of relief supplies every night from the island of Fernando Po (now Bioko). In addition, Lindt brought order to the operations being conducted on the federal side so as to improve the ICRC's credibility with the Nigerian government. Finally, he was a driving force for the operation, emphasising the need to pursue it, to plan, and to stay on track, whereas some Committee members believed that it was too much for the ICRC.Footnote 38 His year-long efforts saw the ICRC commit fully to a major operation, during which it handled more than 100,000 tonnes of food.Footnote 39

Within the ICRC in Geneva, however, Lindt's taking over the operation did not entirely solve the management and organisation problems. Friction was generated at headquarters by the creation of Lindt's office within the ICRC and the arrival of new staff in Geneva to cope with the operation's new dimensions. This clearly demonstrated the limitations of using external staff to manage the operation, as pointed out in hindsight by one of the ICRC directors:

The arrival in Geneva of staff from outside the organization, who came with the idea that they would teach us how to work and set themselves up with a parallel organization, like a foreign body, could only ever provoke a ‘transplant rejection’.Footnote 40

Moreover, the division of responsibilities between the Lindt services and the ICRC was not clearly established and generated confusion. This had a direct impact on the management of field operations, as explained by Gerhart Schürch, head of the ICRC delegation in Lagos during the second half of 1968:

In Lagos no one knew who was in charge. I wrote letters everywhere, to different services, letters which never reached the Nigeria–Biafra coordination office. Even the most urgent requests were only answered after long delays or not at all. The most critical information did not reach us, such as, for example, the decisions taken at the beginning of November as to whether or not the operation would continue. They forgot about or did not want to raise funds, which meant that at the end of September we had no money and had to pay our drivers and people from our own pockets. There was a lack of coordination which was immediately reflected in our work, causing us many problems.Footnote 41

This confusion had implications, not only for the daily running of the operation, but also for the decision-making process of an action that was still in the ICRC's name but was being carried out and organised almost outside of its control. Communication and coordination problems between Lindt and ICRC headquarters in Geneva arose as soon as Lindt took office.Footnote 42 They persisted throughout his mission, as recounted at a later stage by one of the Directorate members during this period:

Given the magnitude and the complexity of the task, you can understand that the head of the mission wanted a free rein. But handing over complete authority to him led to the Nigeria–Biafra operation developing in isolation, almost independently of the normal information, deliberation and decision-making channels that make up the organizational structure of the ICRC.Footnote 43

But it was the ICRC in Geneva that was accountable to its partner organisations and to the governments that had supported it, and it was the ICRC that had to answer the media's questions. Occasionally, Lindt's decisions, which were driven by a desire for effectiveness but were sometimes too radical, prompted the Committee to resume control of the operation. For example, at the end of 1968, when the authorities of Equatorial Guinea obstructed the airlift, Lindt decided to try to transfer the operation to Libreville. This was totally unacceptable to the Nigerian government, given that Gabon had recognised Biafra and that from its capital not only relief but above all arms made their way to Biafra.Footnote 44 To avoid totally alienating the Nigerian government, the ICRC was forced to step in, creating friction but finally causing Lindt to move part of the airlift to Dahomey (now Benin) rather than to Gabon. Lindt's resolve to treat the Nigerian government and the Biafran authorities on an equal footing,Footnote 45 and to push for the ICRC to maintain full control of the operation while some members preferred to delegate the task to other organisations, were other sources of friction between the commissioner-general and the Committee.Footnote 46 Overall, the commissioner-general's enterprising attitude, coupled with his strong personality, was beneficial to the operation. It helped shake up a Committee that had sometimes been overly cautious. However, it also contributed to the hardening of the Nigerian government's attitude towards the ICRC in the middle of 1969, which marked the beginning of the end of the organisation's activities in Nigeria and Biafra. Many factors contributed to the government's new stance,Footnote 47 but it initially manifested itself in relation to Lindt, who was arrested and declared persona non grata on federal soil. The Nigerian government's discontent was focused on the person of Lindt, described by some as too authoritarian and arrogant,Footnote 48 thereby demonstrating the risks of associating an operation with one individual. Besides the fact that such an approach can lead to organisational difficulties and differences of opinion, it can also jeopardise the future of entire operations. After the incidents in June 1969, for instance, the ICRC was stripped of its role as operations coordinator in Nigeria and was unable to resume the airlift.

At the end of the operation, the ICRC identified several lessons to be learned. A restructuring was required in order to be able to handle new situations as they arose. The measures taken also fitted into a more in-depth process of reform that had already been under way, as has been pointed out, even before the Nigeria–Biafra conflict made the need for reform so flagrantly obvious. A new structure was put in place in 1970 ‘to regroup the support services which participated in external activities in an Operations Department’.Footnote 49 This reflected the ICRC's awareness of the need to better coordinate and lead the growing number of external operations in which it was involved. It was in line with the idea of establishing a delegation service, which had already been discussed in 1968Footnote 50 and was part of a wider restructuring process undertaken by the ICRC in 1970.Footnote 51 The decision-making and governing bodies also came under scrutiny since the ICRC was faced with the resignation of both the president and one of the directors-general between 1968 and 1970.Footnote 52 This highlighted the need to recruit younger members who would be willing to make a long-term commitment to the ICRC's work. The distinction between the responsibilities of the Committee and the Presidential Council was made clearer in 1974, and humanitarian professionals gradually had more say in the ICRC's policies.Footnote 53

Recruiting, training, and managing field staff

ICRC resources fell dramatically after World War II, leading to staff cutbacks. A Group for International Missions was set up in Bern to give the ICRC access to people recruited from academia, the military, public services, and industry, available on call for two-month assignments.Footnote 54 The Nigeria–Biafra war exposed the limitations of that set-up, however. This prompted the ICRC to explore other staff recruitment options as part of its reflection about the profile of its humanitarian workers.

During the first year of the Nigeria–Biafra conflict, the ICRC's involvement was largely limited to sending medical equipment and personnel to war-torn areas. Staff recruitment difficulties therefore first became apparent in this sector. The ICRC turned first to the Swiss Red Cross, which, with the financial support of the Swiss government,Footnote 55 was supposed to provide field teams. The results were inconclusive, however; new recruits seemed to be hard to find. So two doctors, Guido Pidermann and Edwin Spirgi, both of whom had worked several times for the ICRC, ended up setting up the first two medical teams in Nigeria and Biafra. It quickly became clear that there were not enough Swiss staff to meet the ICRC's needs, and the organisation was forced to internationalise its operation by asking various other National Societies to provide medical teams, much like it had done for its operations in the Congo and Yemen.Footnote 56 It also accepted the support of other organisations, including religious groups such as the World Council of Churches. However, these joint efforts were still not sufficient. Some National Societies were slow to act and were hampered by the same difficulties that the ICRC had encountered in dispatching field teams.Footnote 57 In the spring of 1968, refugees and other civilians ‘who lack everything’Footnote 58 were in desperate need of food aid, but the ICRC was unable to maintain a team in Biafra. This highlighted its serious problem with recruiting staff – in fact it had no medical personnel in Biafra between January and July 1968, while in Nigeria it was understaffed.Footnote 59 The difficulties brought to light by the Nigeria–Biafra conflict led the ICRC to explore possible longer-term solutions to overcome this lack of medical staff:

As regards the lack of medical staff, some members pointed out that, since this problem has still not been resolved, it is high time that the project previously proposed by Mr Petitpierre – setting up a ‘humanitarian contingent’ ready to serve in any circumstances – should go ahead as soon as possible. This project could even go beyond the Swiss context to be handled at the international level.Footnote 60

Media coverage of the Nigeria–Biafra crisis in the summer of 1968 brought a solution to this problem as more and more people responded to the ICRC's call for volunteers. By the end of August, in addition to its own staff, the ICRC had more than 200 American and European workers on the ground who had been seconded from other organisations. In addition to the Danish, Finnish, Norwegian, and Swedish Red Cross Societies, which provided most kwashiorkor specialistsFootnote 61 and aircrews, the American, Dutch, Swiss, and Yugoslav Red Cross Societies provided the ICRC with medical and technical staff.Footnote 62 Around 70 people working for the ICRC's operations had been sent by the Salvation Army, Oxfam, the World Council of Churches, the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, the Save the Children Fund, and the International Union for Child Welfare.Footnote 63 As well as this cooperation between various Western organisations, the Nigerian Red Cross Society was increasingly involved in the ICRC-coordinated operation. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3. A medical team from the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, Biafra, July 1968. © ICRC photo library.

This strategy enabled the ICRC to pursue its work, but it was also a source of friction owing to the volunteers' diverse institutional, cultural, national and generational backgrounds. In addition, the relative openness of the ICRC when it came to recruiting medical and technical staff contrasted with its recruitment policy for key positions in the operation, and more generally for the position of delegate.Footnote 64 While it was facing the same staff shortages in these areas, its strategy for finding new delegates remained Swiss-centric.

At the beginning of the conflict, the ICRC had trouble assigning a delegate to Biafra. A few people were considered, but they encountered obstacles in the field – it was difficult to get into the secessionist region, and they were greeted with suspicion. In the summer of 1967, the Biafran authorities were more concerned about strengthening the security of the young Republic of Biafra and obtaining the support of foreign governments than about humanitarian issues. Meanwhile, some ICRC delegates thought that a mission to Biafra would be pointless and were not particularly enthusiastic about going there.Footnote 65 So, after a few weeks, the ICRC turned to Karl Jaggi, a Swiss citizen and representative of the Swiss Union Trading Company who was based in what had become Biafra. He became the ICRC correspondent there. He has been described as knowing nothing of the principles of the Red Cross but being well established in Biafran circles.Footnote 66 Calling on expatriate Swiss citizens was a relatively common ICRC practice. In the case of Biafra, however, the situation was slightly different, because Jaggi's duties were not to represent the ICRC in occasional dealings with the authorities but rather to mount a humanitarian operation in a civil war. Nevertheless, Jaggi seems to have been the right choice because his temporary appointment became a more permanent one. He became the head of the ICRC delegation in Biafra at the end of 1967, a position that he held until the end of the airlift to Biafra at the end of the summer of 1969.Footnote 67 The decision to turn to people not connected with the ICRC, or indeed with the whole Red Cross Movement, was a case in point of the ICRC's recruitment policy for positions of responsibility during the conflict.

The famine in the summer of 1968 led to an influx of food relief, which created a new set of problems for the ICRC. From June 1968, governments and charities sent thousands of tonnes of aid to the port of Lagos, which then had to be transported to the east of the country. Identified as a neutral intermediary specialising in humanitarian aid, it was the ICRC's task – in conjunction with the Nigerian Red Cross, the Nigerian government, and various humanitarian organisations – to organise the storage, transportation and distribution of relief for the civilian population. These tasks required the recruitment of medical personnel and staff able to plan, coordinate and carry out such a large-scale distribution operation, involving many different agencies and organisations. Dissatisfaction at the ICRC's handling of the operation was already being voiced in Lagos in June. The Swiss ambassador reported that the ICRC delegation did not seem up to the task. Food shipments held up in the port of Lagos were spoiled, and there were complaints about the behaviour of some members of its teams.Footnote 68 Once again, to retain control of the operation, the ICRC had to be seen to be taking the situation in hand. It first sent the Swiss director of an international transport company, to whom it entrusted the coordination of the relief operation in federal territory. This measure proved to be insufficient, and a new head of delegation was recruited: Gerhart Schürch. He was an elected member of the Grand Council of Bern and member of the City of Bern Executive Council who had carried out assignments for the Don Suisse organisation in 1947 and 1949.Footnote 69 Just like Jaggi in the summer of 1967, Schürch was recruited from outside the ICRC and, in fact, had no connection to the Red Cross Movement. Thus, from the summer of 1968, those who held the key positions in the rescue operation – namely the commissioner-general and the heads of delegation in Nigeria and Biafra (Lindt, Schürch and Jaggi) – were not ICRC delegates but Swiss citizens recruited from political and economic circles. (Fig. 4)

Figure 4. From left to right: Mr Falk (from Sweden), Mr Lindt and Mr Jaggi, in Biafra. © ICRC photo library/R. With.

In the late 1960s, the ICRC viewed this approach as a solution not only in crises but also more generally to deal with the problem of recruiting delegates. Indeed, in July 1968, the ICRC director-general went to the Federal Political Department in Bern to explain the organisation's recruitment difficulties. He requested the secondment of some of the department's staff to the ICRC for delegate assignments lasting several months. He also wanted the Department of Economic Affairs to lobby large Swiss companies to make some of their employees available to the ICRC on a temporary basis.Footnote 70 The second scenario was most closely followed.Footnote 71 For example, after the resignation of Auguste Lindt in June 1969, Enrico Bignami, vice-president of Nestlé-Alimentana and founder of the IMEDE business schoolFootnote 72 in Lausanne, was tasked with conducting negotiations between Nigeria and Biafra.

However, these options did not excuse the ICRC from developing a robust policy for recruiting, training and managing field staff. Following his experience as head of delegation in Lagos, Schürch made a number of observations about the impact of the ICRC's recruitment and management system on the effectiveness of relief operations.Footnote 73 He identified several shortcomings. First, he believed that the three-month duration of a field delegate's assignment was too short, given how long it took to adapt. In addition, it resulted in an excessively high staff turnover, with the ensuing problems of recruiting new staff at the end of each assignment and ensuring the continuity of the operation. The situation at the Lagos delegation at the end of 1968 was another case in point. Although Schürch's assignment was due to finish at the end of December, at the beginning of the month his replacement had not yet been found. He was therefore unable to properly prepare his handover with the authorities in Lagos.Footnote 74 Schürch also emphasised the lack of professional experts in the ranks of the field volunteers, saying: ‘the system of recruiting volunteers, while necessary, I concede, has serious shortcomings, in that you will always find adventurers who are worthless professionally, and idealists who have good intentions but are unable to execute them in practice’.Footnote 75

This problem was compounded by the lack of a training and selection process for volunteer field staff. One interview in Geneva prior to the staff's departure for the field was insufficient, especially as they did not always go via headquarters. These deficiencies forced the delegation in Lagos to set up a selection and training system in the field.Footnote 76 They affected not only the efficiency of the ICRC's work but also its relationship with the Nigerian authorities and relief organisations. For example, Schürch described how some volunteers' poor grasp of English helped to fuel the federal authorities' suspicions about relief organisations.Footnote 77 Some Nigerian aid workers viewed some of the ICRC staff as inexperienced and with poor cultural adaptability.Footnote 78 This impression was accentuated by the fact that, in the early days of the conflict, the ICRC significantly underestimated the need to include Nigerians in its ranks. This amateurishness on the part of the ICRC when it came to managing staff in the field fuelled criticism by the Nigerian authorities regarding the conduct of humanitarian organisations, as exemplified by the Nigerian head of state, who said: ‘it will help if the Organizations drop their racist overtones of the “whiteman's burden in Nigeria” and quietly and more effectively supplement our local efforts where they can’.Footnote 79

The Nigeria–Biafra conflict starkly exposed the need to professionalise the ICRC's workforce (particularly its delegates), to improve recruitment, and to rethink the length of their assignments. In 1970, a more rigorous recruitment process was introduced, whereby candidates were selected on the basis of applications and interviews, followed by three to five days of training in Cartigny, near Geneva. Delegates were hired for renewable assignments lasting around six months. In addition, the ICRC realised that it could no longer rely on volunteers and that, if it wanted a competent workforce, it would have to find ways to keep staff in the organisation. Starting in 1974, thirty permanent delegates were hired for a period of five years. This became the norm in the late 1970s.Footnote 80 These decisions signalled a major shift in the ICRC's staff management policy.

Is communication necessary?

The communication policy of humanitarian actors – necessary for informing and mobilising public opinion – is usually approached in terms of speaking out. Indeed, there has been much debate about this aspect in the literature on humanitarianism, largely as a result of the ICRC's decision not to publicly denounce the genocide of the Jewish people during World War II.Footnote 81 More generally, the ICRC's policy of discretion has been called into question.Footnote 82 The literature on MSF has particularly singled out the Nigeria–Biafra conflict as the moment when this approach was challenged by the future founders of the organisation.Footnote 83 While the importance of the Biafran experience for the founders of MSF should not be underestimated,Footnote 84 a more in-depth study of the relationship between the French doctors and the ICRC offers a more nuanced view of this split. It is possible to distinguish between two types of reaction by the ICRC when confronted with the field delegates' declarations, which were made not only by the French doctors but also by other delegates. When it came to communicating about the activities of the ICRC, the statements of the French volunteers were tolerated and even well received within the ICRC. But when it came to denouncing the actions of the Nigerian government, this proved to be more difficult for the organisation. Nevertheless, this did not bring about any profound changes in the attitude of the Committee vis-à-vis its staff in the field. The question of whether or not to speak out, as fundamental as it may be, was therefore just one of the issues facing the ICRC in terms of its communications policy during the conflict. Michael Barnett has noted that one of the peculiarities of humanitarian crises of the 1960–1980 period was the scale of the response, even though they mostly occurred in parts of the world that did not usually arouse the interest of public opinion in the West.Footnote 85 For the ICRC, the increasingly important role played by the media and the growing number of humanitarian organisations raised the question of its interaction with these different players. Into the 1960s, the ICRC did not make it a priority to inform them about its activities. It therefore devoted relatively few of its resources to communication, all the more so in that it retained an ideal of action based on discretion.Footnote 86 Just as the Nigeria–Biafra war had exposed the weaknesses in the functioning of the organisation and its staff, it also revealed the ICRC's failure to give due consideration to its information policy.

At the start of the Nigeria–Biafra conflict, the ICRC had no real information policy. It did make tentative efforts to improve its external relations, as evidenced by the introduction in February 1968 of a system of monthly press conferences on ICRC activities.Footnote 87 When the situation started deteriorating on the ground in the late spring of 1968, the ICRC tried to alert world opinion and win media support for its efforts to roll out a large-scale humanitarian operation in Biafra, where the needs were most obvious. Its efforts met with limited success. More than anything else, they succeeded in angering the Nigerian government, illustrating the ICRC's amateurism in its public relations.Footnote 88 The lack of a clear policy and of staff responsible for information mattersFootnote 89 led to the conclusion that the ICRC had not taken public relations seriously enough:

There have been dozens of misunderstandings due to lack of information. In my opinion we should set up our own press service, with a ‘public relations’ professional heading up a team of one or two journalists. They would be posted with the field staff so as not to have to wait for news, because it is natural that ICRC delegates often do not find time to write reports. A press team could resolve all sorts of problems. They would arrange regular visits with photographers and cameramen. Such a team would certainly be more useful than the amateurs currently running the information desk.Footnote 90

The conditions in which the Nigeria–Biafra operation unfolded made it particularly necessary to have a solid policy for communicating with the media and with the ICRC's partners. Firstly, the intense media coverage from the summer of 1968 contrasted sharply with the trickle of information provided by the ICRC during that period. As its difficulties in setting up the Biafra operation were earning it a great deal of criticism, some within the Committee pointed out that communicating better about what it had already accomplished in the conflict could boost its image.Footnote 91 In addition, the growing number of humanitarian agencies involved in civilian relief put pressure on the ICRC to prove its effectiveness if it was to hold onto its position as a key player in the humanitarian sector. Within the Red Cross Movement, some National Societies questioned the merits of making the ICRC responsible for relief efforts in armed conflict. More generally, relief operations run by religious organisations attested to the fact that the ICRC was not indispensable and that others could take its place.Footnote 92 The ICRC therefore needed to assert its position and credibility, which would be achieved in part by improving its communication. As one of the Committee members pointed out, ‘the ICRC's real worth is measured by people's trust in it. If it wants to preserve that, the Committee should break its silence without delay because the press is growing increasingly critical of it’.Footnote 93 The ICRC's silence over its representations to the parties to the conflict and over the state of the negotiations tainted its relationship not only with the press but also with potential partners, who did not like the way they were treated by the ICRC.Footnote 94 Similar questions were being raised within the organisation itself, and some delegates took the liberty of communicating with the media.Footnote 95

While this lack of information sullied the image of the ICRC, it also had an impact in terms of financial resources at a time when the ICRC was struggling to raise funds for its operations.Footnote 96 Its funding depended on maintaining relationships with the governments and National Societies that were its main sources of support. Otherwise, it risked seeing potential resources being given instead to other organisations that appeared to be more active. This is what happened at the end of 1968, when the US government decided to divide the resources it gave to Biafra relief between the ICRC and the churches.Footnote 97 Better communication could also help it resolve some of its staffing problems. To recruit qualified personnel in Switzerland, the Committee needed to raise the profile of its activities. Among other things, this meant making better use of the media, including through radio and television campaigns.Footnote 98 For these reasons, at the end of the summer of 1968, the ICRC took several concrete measures to respond to media pressure and to improve its relationship with other individuals and organisations involved in humanitarian operations. (Fig. 5)

Figure 5. Auguste Lindt at a press conference on Biafra, Geneva, 14 August 1968. © ICRC photo library (DR)/Jean Zbinden.

Briefings with partners and journalists were stepped up significantly from the end of the summer of 1968. The ICRC organised more press conferences and trips abroad by members of the Committee to boost the profile of its activities and to raise funds.

The ICRC also produced two films, one on Biafra and the other on Nigeria, which it distributed to National Red Cross Societies as well as to the public in order to showcase its activities in the conflict. In the spring of 1969, Lindt was featured in the British television show The Man of the Month. The use of visual resources was not new to the ICRC, which regularly produced films about its activities and had used photographs in its publications for many years. However, there was an increased awareness of the importance of pictures for disseminating information about the ICRC:

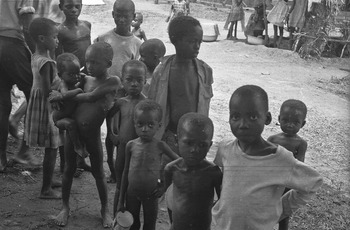

The interest in our Nigeria–Biafra relief efforts has led to an unprecedented output, but unfortunately we have reached the limit of our material capacity. While Mr Melley last year printed and distributed an average of 300 photographs, the figures he has achieved since the beginning of 1969 are as follows: 809 images distributed in January, 574 in February, and 962 in March. These results are very encouraging because quite often the publication of a single photo has greater impact than a lengthy text.Footnote 99 (Fig. 6)

Figure 6. Refugee children of the Nigeria–Biafra war, Awo Omama camp. This photograph appeared in No. International Review of the Red Cross, No. July 1968. © ICRC photo library/Adrien Porchet.

In addition to these measures, the ICRC did not hesitate to use the articles published by journalists or even by some of its volunteers to generate interest in its activities, for instance by reproducing them in the International Review of the Red Cross.Footnote 100 The ICRC therefore appeared relatively tolerant of the public statements made by its volunteers when they fit in with its communication policy. The ICRC went even further when it assigned a journalist from the Neue Zürcher Zeitung to its delegation, who was then tasked with negotiating the resumption of the airlift in the autumn of 1969. However, since the Committee did not deem the outcome of this experience to be particularly favourable for the organisation, it did not repeat it.Footnote 101 In late 1969, the new president decided on a new-look policy for the ICRC's media relations in order to raise the organisation's profile among reporters.Footnote 102 Finally, the conflict prompted the ICRC to rethink its position on publicly denouncing belligerents for their role in the suffering of the population. With some staff members calling for the ICRC to publicly denounce the Nigerian government's bombings of civilian targets, the organisation decided to draw up more precise guidelines for public denunciation.Footnote 103 This coincided with similar issues arising in other parts of the world where the ICRC was operating, such as Yemen, the Middle East, and Greece.

Despite the ICRC's efforts to develop a communications policy during the Nigeria–Biafra conflict, when the time came to review that experience, it was clear that there was a need to rethink the ICRC's external relations:

The ICRC's vulnerability to having public opinion ‘poisoned’ against it highlights the uncertainties of its information policy and the weaknesses of its system of communication with various bodies, which it must enlighten as to its goals and motives, as well as with world opinion, whose sympathy it must win. One of the ICRC's major ongoing tasks, and its primary concern in times of conflict, is to rally a force of humanitarian persuasion bringing together as many moral, diplomatic and material resources as possible, without which it is powerless. Such a common front can be forged in peacetime; a methodical campaign should be undertaken to establish and anchor the ICRC's role and image ever more strongly in the eyes of governments, the Red Cross, and among the various organizations with which it may be called upon to cooperate. It is precisely because humans are not by nature impartial that a sustained effort must be pursued relentlessly to sway world opinion by all direct and indirect means.Footnote 104

In practice, in 1970, this meant scaling up the information service, which was then attached directly to the Presidential Council.Footnote 105 While reaffirming its determination to balance action and discretion, the ICRC focused on improving the transmission of information from both headquarters and the field.Footnote 106 In addition, by stepping up its contact with potential major donors, it adopted a much more active approach to fundraising, thereby boosting its budget for relief operations.Footnote 107 This was at a time when humanitarian organisations more generally were looking at their relations with public opinion and the media. This was indeed the case within the Red Cross Movement. In 1967, a meeting of the information officers of the Movement's member organisations was held to ‘examine anew the capitally important problem of Red Cross public relations’.Footnote 108 A second, similar meeting took place in 1970, which addressed in particular the issue of ‘information in emergency situations’ and relations with the ‘mass media’.Footnote 109 Media relations were also a major concern for the new humanitarian actors that emerged in the 1970s.

Conclusion

The late 1960s, with the growing number of contexts in which the ICRC was operating, heralded a profound change in the organisation. Its experiences during the Nigeria–Biafra conflict drew attention to many aspects of the ICRC's set-up. First, the conflict marked the beginning of an increase in the organisation's assistance activities, which today represent a large part of its work. For observers of the time, the ICRC's involvement in the Nigeria–Biafra conflict, which was a relatively long-term commitment to a civilian relief operation for which it had the primary responsibility, in an internal conflict of an ‘international character’, was a ‘new type of engagement to which the development of contemporary international relations can lead the ICRC’.Footnote 110 For the members of the Committee, it marked a turning point in the ICRC's history, as evidenced by this reflection:

The Committee must therefore be fully aware that … it is now agreeing to embark on a new type of intervention, which is valid not only for the case that now concerns us but also for other future actions.Footnote 111

This shift was confirmed in subsequent years and is useful for understanding the role of assistance activities today. The Nigeria–Biafra conflict also highlighted the difficulties involved in this type of complex operation for an organisation whose resources remained limited. It underlined the need for various reforms, some of which were planned but were only implemented very slowly. The ICRC's simultaneous involvement in other parts of the world, such as the Middle East, accentuated this need. The 1970s dawned with a clear understanding that reform was imperative to enable the ICRC to ‘organize the unpredictable’.Footnote 112 When the Directorate was dissolved at the end of 1969, the Committee hired a new staff member, with the title of secretary-general, whose primary responsibility was to identify the ICRC's functioning and management problems and to propose improvements. The three areas specifically brought to light by the Nigeria–Biafra war, and addressed in this article, were among the priorities. Measures were taken in each of these areas, but it took time for them to pay dividends, as the Tansley report pointed out in the middle of the 1970s. It was a long road to the ICRC as it exists today and there would be other equally decisive events along the way, but the awakening of the early 1970s was a pivotal moment. Reforms gradually converged on the professionalisation that enabled the ICRC to become increasingly effective in the field. This process was a prerequisite for conducting major operations in multiple and varied contexts and for maintaining a dominant position in the increasingly competitive humanitarian sector.