Introduction

Population ageing has posed formidable challenges to the aged care system that many countries have to face. Such a challenge is particularly severe for Chinese societies (mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan), which together host one-fifth of the world's elderly population (World Bank, 2016). In traditional Chinese societies, family is a fundamental institution supporting the older people. An adult child is obligated to live with and take care of ageing parents (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Xie and Yu2011). However, profound social changes, such as declining fertility, emerging individualism and migration, have gradually decreased the traditional support from family (Logan and Bian, Reference Logan and Bian1999; Yu and Xie, Reference Yu and Xie2015; Courtin and Avendano, Reference Courtin and Avendano2016; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Pearce and Hu2018; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Bell and Zhang2019). Older people may encounter more obstacles to maintain their wellbeing than ever before.

Social scientists studying the determinants of subjective wellbeing claim that, although the traditional sources of support for the elderly have inevitably dwindled amid development, psychological wellbeing of the older people is not necessarily threatened (Chen and Short, Reference Chen and Short2008; Yamaoka, Reference Yamaoka2008). Social integration theory emphasises that social bonds, including the informal ties to family and friends and formal links to community groups and institutions, have powerful effects on physical and mental health (Berkman and Glass, Reference Berkman, Glass, Berkman and Kawachi2000). Researchers further speculated that the relative importance of informal and formal social ties depends on socio-economic development level (Höllinger and Haller, Reference Höllinger and Haller1990; Berkman and Glass, Reference Berkman, Glass, Berkman and Kawachi2000). In a traditional family-dominated society, nearly all the needs of an individual are fulfilled within the family. Attachment to family plays a determining role in individual's wellbeing. The process inherent in social development, however, is the transformation of a kinship-dominated society to one that emphasises individualism, independence, social/communal life and self-fulfilment (Inglehart, Reference Inglehart2006). Membership in broader social structures is more critical for obtaining information, resources, and opportunities in a more developed society (Portes, Reference Portes1998; Berkman et al., Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000). Thus, it is believed that the effect of social participation on subjective wellbeing would gradually surpass that of multigenerational co-residence when society becomes developed and less bound by traditional values (Helliwell and Putnam, Reference Helliwell and Putnam2004).

In this study, we test this conjecture by comparing Hong Kong, urban China and Taiwan. In contrast to previous studies of cross-country comparison, the three Chinese societies obviously share similar cultural characteristics but differ in socio-economic conditions (Wallace and Pichler, Reference Wallace and Pichler2009; Wu, Reference Wu2009; Yasuda et al., Reference Yasuda, Iwai, Yi and Xie2011; Yu and Xie, Reference Yu and Xie2011; Gierveld et al., Reference Gierveld, Dykstra and Schenk2012; Teerawichitchainan et al., Reference Teerawichitchainan, Pothisiri and Long2015). Such a comparison can provide more solid evidence to examine how the determinants of the elderly's subjective wellbeing evolve with socio-economic development by controlling for unobserved social and cultural heterogeneity to a great extent.

Background

Rapid population ageing and changes in family norms in Chinese societies

Chinese societies are ageing, and they will do so increasingly rapidly in the near future. The elderly made up 10.1, 15.8 and 13.2 per cent of the total population in mainland China, Hong Kong and Taiwan in 2016, respectively (World Bank, 2016; National Statistics of Taiwan, 2018). Rapid ageing in Chinese societies has been accompanied by a substantial change in family values. For centuries, the ideal Chinese family is a patriarchal extended family. An adult child, usually the eldest son, is obligated to live with his parents and take care of them, even after getting married and having children of his own (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Cong and Li2006). This tradition stems from Confucian doctrines that emphasise children's filial obligation to their parents (Nauck and Ren, Reference Nauck and Ren2019). Nowadays, however, declined preference towards multigenerational co-residence suggests that traditional family norms have changed (Logan and Bian, Reference Logan and Bian1999; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Pearce and Hu2018).

This change in family norms is taking place in the three Chinese societies at different paces. Hong Kong seems to be the least bound by traditional norms among the three societies. Yip and Forrest (Reference Yip and Forrest2014) found that 65 per cent of the young people in Hong Kong said that they would move out of their parents’ home as soon as they can afford to live independently. In contrast, the younger generation in Taiwan is most likely to adhere to filial piety; among those, 61 per cent believed that children should continue to live with their parents after getting married (calculated from the 2011–2012 Taiwan Social Change Survey). Mainland Chinese may be more conservative than Hong Kong people but less traditional than Taiwanese: 44 per cent of senior residents in mainland China reported that they would prefer to live with their adult children (calculated from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, 2011). The sixth wave of the World Value Survey also revealed that Taiwan people attached the greatest significance to family and tradition, followed by people in mainland China and Hong Kong (World Value Survey, 2019). Adults in Taiwan gave the highest score to the importance of family (3.89 out of 5) and tradition (4.58 out of 6), and the Hong Kong people reported the lowest scores (see Table S1 in the online supplementary material). Why do the three societies differ in the extent to which they are preserving traditional family values? The answer might be related to the divergent economic and political paths that they have taken in the past century (Wong, Reference Wong1975; Davis-Friedmann, Reference Davis-Friedmann1991; Logan and Bian, Reference Logan and Bian1999; Yu and Xie, Reference Yu and Xie2015; Courtin and Avendano, Reference Courtin and Avendano2016; Jin et al., Reference Jin, Pearce and Hu2018; Liu et al., Reference Liu, Bell and Zhang2019).

As a British colony for one and a half centuries, Hong Kong is the most modernised Chinese society due to long-term exposure to industrialisation and internationalisation (Chiu and Lui, Reference Chiu and Lui2009). Western institutions and culture brought new values and norms into Hong Kong people's daily life, giving way to a unique mix of Eastern and Western cultures. Hong Kong took a fast track to industrialisation in the 1950s and 1960s, much earlier than mainland China and Taiwan. Industrialisation disrupted the traditional family norms by emphasising new values, such as individual achievement, economic independence, and social and geographical mobility. The nuclear family, consisting of a married couple with or without unmarried children, became the most common family structure in Hong Kong even before the 1960s (Wong, Reference Wong1975). Hong Kong continued to develop rapidly, thanks to its unique geographic position and practice of laissez-faire capitalism (He and Wu, Reference He and Wu2019). The city eventually emerged as a highly modernised industrial-commercial centre in Asia in the 1990s and has become the most modernised society among the three in this study.

Taiwan is similar to Hong Kong regarding its colonial history and economic miracles back in the 1970s. However, Taiwan may have preserved more traditional Chinese family values than Hong Kong for several reasons (Yu, Lin and Su, Reference Yu, Lin and Su2019). First, during its half a century of Japanese colonisation, Taiwan did not undergo an industrial revolution or internationalisation. The colony was regarded as an agricultural appendage to be developed as a complement to Japan. It was still an agriculture-dominant society in 1945 when the Nationalist Party took power. Moreover, the Japanese colonial government made no explicit efforts to modify family life in Taiwan, which contributed to the persistence of principles of patrilineality and patrilocality (Thornton and Lin, Reference Thornton and Lin1994). Second, Taiwan's economic growth after the 1960s relied heavily on export-oriented industrialisation facilitated by small- and medium-sized family enterprises. Supported by the government, family firms emerged on a large scale and eventually made Taiwan one of the ‘Four Little Dragons’ in the 1970s. These firms were organised along the lines of the patriarchal extended family and adopted collectivist ethics. They were competitive in the market because of their flexibility, specialisation and underpaid labour resources, and because employees worked tirelessly for the long-term benefit of the family (Greenhalgh, Reference Greenhalgh1994). Nowadays, family businesses account for more than 70 per cent of Taiwanese enterprises (Chinese Family Business Global, 2013). This proportion is much higher than average in Asia (Claessens et al., Reference Claessens, Djankov and Lang2000). Family firms served as a place to practise and preserve traditional family values, which were legitimised through economic success.

Industrialisation and economic growth in mainland China affected traditional family values in a way similar to that in other areas, especially after its economic reform and opening up to the world in the late 1970s (Wu, Reference He and Wu2019). The uniqueness of mainland China lay in the fact that political campaigns in the 1950s to the 1970s have undermined the influence of traditional family norms. After 1949, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) considered patriarchy family norms backward and feudalistic, and attempted to eliminate them from new socialist China. The CCP adopted a variety of measures to reduce parental authority, and to promote egalitarianism between parents and children. For instance, it offered young people jobs in state sectors or the military to increase their independence. Campaigns on reforming family norms reached a peak in the Cultural Revolution, in which young people were encouraged to draw a clear line between themselves and parents from an undesirable political background and to criticise their parents who made mistakes (Davis-Friedmann, Reference Davis-Friedmann1991). These measures may have contributed to the greater decline in traditional norms in mainland China than in Taiwan today, even though Taiwain is more socio-economically developed than China as a whole (Wu, Reference Wu2009; Yu and Xie, Reference Yu and Xie2011).

Living with adult children and subjective wellbeing

The impacts of co-residence with adult children on emotional health vary across countries. It may be attributed to normative attitudes towards family responsibility related to socio-economic development (Logan and Bian, Reference Logan and Bian1999; Chen and Short, Reference Chen and Short2008). Researchers have shown that in developing societies where intergenerational ties are strong, living with adult children usually has beneficial effects on the wellbeing of older parents (Samanta et al., Reference Samanta, Chen and Vanneman2015; Yamada and Teerawichitchainan, Reference Yamada and Teerawichitchainan2015; Teerawichitchainan et al., Reference Teerawichitchainan, Pothisiri and Long2015). They claimed that, in the societies whereby filial piety is deeply embedded in the culture, living with adult child may improve the elderly's emotional wellbeing because it fulfilled the culturally prescribed expectations (Chen and Silverstein, Reference Chen and Silverstein2000). Furthermore, co-residence with adult child may facilitate financial support and aid in daily life, and reduce loneliness and isolation, and thus is beneficial for the wellbeing of the elderly (Li et al., Reference Li, Liang, Toler and Gu2005).

On the contrary, in developed western countries, residence with children did not promote or could even be detrimental to elderly parents’ mental health, except in times of crisis (De Jong Gierveld and Van Tilburg, Reference De Jong Gierveld and Van Tilburg1999; Jeon et al., Reference Jeon, Kawachi, Rhee, Jang and Cho2007; Oshio, Reference Oshio2012). Multiple reasons may contribute to the different roles of co-residence with children in developing and developed societies. First, researchers have revealed age-related norms for home leaving in developed countries (Veevers et al., Reference Veevers, Gee and Wister1996; Settersten, Reference Settersten1998). Violating the norms regarding intergenerational co-residence may lead to stigma that was associated with decreased subjective wellbeing of parents (Mitchell and Lovegreen, Reference Mitchell and Lovegreen2009). Second, studies found that parents tended to give on average more support to their adult children than they received from them in developed countries (Grundy, Reference Grundy2005; Smits et al., Reference Smits, Van Gaalen and Mulder2010). This phenomenon became more common as the economic insecurity of younger cohorts accelerated (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2012; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Goldscheider and García-Manglano2013). The increased material and emotional burden may reduce the wellbeing of the elderly. Frictions in family life and lack of privacy may also diminish the elderly's psychological health (Ren and Treiman, Reference Ren and Treiman2015).

The association between living with grandchildren and the elderly's psychological wellbeing also depended on social attitudes towards family responsibility. Co-residence with grandchildren was more likely to associate with better wellbeing in a more familism society (Teerawichitchainan et al., Reference Teerawichitchainan, Pothisiri and Long2015). Multiple generations living together was considered a great joy for the elderly in traditional Chinese society which emphasised collective family goals over individual goals (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Liu and Mair2011, Reference Chen, Bao, Mair and Yang2014). Grandparenting may optimise labour division within the family by easing the burden of the younger generation (Chang, Reference Chang2015). By living with and taking care of grandchildren, the elderly gain self-worth and respect from others (Silverstein et al., Reference Silverstein, Cong and Li2006).

Based on the above analyses, we derive our first research hypothesis as follows:

• Hypothesis 1: As society becomes more socio-economically developed and less bound by traditional family norms, co-residence with younger generations plays a less important role in promoting the elderly's subjective wellbeing. Because Hong Kong is more developed and preserves fewer traditional values than mainland and Taiwan, then:

• Hypothesis 1a: The elderly living independently with a spouse enjoy greater subjective wellbeing than those co-resident with their adult children, and this is more likely to be the case for the elderly in Hong Kong than for those in mainland China and Taiwan.

• Hypothesis 1b: The presence of grandchildren is associated with the elderly's subjective wellbeing to a lesser degree in Hong Kong than in mainland China and Taiwan.

Social participation and subjective wellbeing

Social participation may be more closely related to a person's subjective wellbeing in more-developed societies. Social integration theory claims that membership in broader social structures plays a determinant role in individual's wellbeing in modern society because links to community groups and institutions are crucial for obtaining information, resources and opportunities (Portes, Reference Portes1998; Berkman et al., Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000). At the same time, when people and societies become more affluent and modernised, people’ needs shift from the lower-order ones (biological and safety-related needs) to the higher-order ones (self-esteem and self-fulfilment) (Hagerty, Reference Hagerty1999). Social participation is an important way to satisfy one's higher-order needs. By joining social organisations and participating in social activities, individuals gain a sense of value, belonging and attachment (Berkman et al., Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000).

Social participation affects subjective wellbeing through both social and psychological processes. Participating in social organisations may diversify and broaden one's social networks, through which people share information, provide and receive support, and work together to achieve collective goals that could not be accomplished by any individual (Portes, Reference Portes1998). Also, taking part in various social groups may create or reinforce meaningful social roles, such as occupational and community roles, which in turn provides a sense of value and attachment, and promotes self-esteem and self-worth. These psychological resources can improve subjective wellbeing by enhancing the ease with which people adapt to stressful life events, promoting positive effect and preventing depression (Berkman et al., Reference Berkman, Glass, Brissette and Seeman2000). The positive relationship between social participation and the elderly's subjective wellbeing has been well established in the United States of America and in European countries (Wallace and Pichler, Reference Wallace and Pichler2009). Yet, the beneficial effect of social engagement is seldom observed in Chinese societies (Yip et al., Reference Yip, Subramanian, Mitchell, Dominic, Wang and Kawachi2007; Yamaoka, Reference Yamaoka2008). One possible explanation is that the meaning of social participation differs from that in developed countries partly due to political reasons. The Chinese government has adopted restrictive regulation on social organisations. Thus, participating in social organisations may be less effective in generating social capital that would improve subjective wellbeing (Yip et al., Reference Yip, Subramanian, Mitchell, Dominic, Wang and Kawachi2007).

Based on the above studies of socio-economic development and social engagement, we propose our second research hypothesis:

• Hypothesis 2: Social participation is associated with the elderly's subjective wellbeing to a greater degree in Hong Kong than in urban China and Taiwan.

Data, measurement and method

Data

Our sample consists of Chinese people aged 60 and above and is drawn from the 2011 wave of the Hong Kong Panel Study of Social Dynamics (HKPSSD), the 2010 wave of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) in mainland China and the 2010 wave of the Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS). The HKPSSD is the first household panel survey in Hong Kong. It generates a representative sample of Hong Kong households and collects a broad range of information on household and individual characteristics (see details in Wu, Reference Wu2016). The CFPS is a nationally representative longitudinal survey. Using a multi-stage sampling method, it collects extensive information on the demographic, socio-economic and health status of individuals and families (for details, see Xie and Hu, Reference Xie and Hu2014). The TSCS is a long-term, repeated cross-sectional survey project that has been following five-year cycles since 1985. It aims to track social changes in Taiwan by providing data on various topics covering family lives, economic activities and social behaviours (for details, see Chang and Fu, Reference Chang and Fu2004). The data used in this study come from the Health and Risk Society questionnaire modules of the sixth (2010) wave of the TSCS. To facilitate comparison between the three societies, we restricted the sample to urban residents in mainland China and Taiwan.

Observations with missing information for any variables account for 11.2, 6.1 and 8.5 per cent of all cases in HKPSSD, CFPS and TSCS, respectively. We use multiple imputations chain equations to create plausible values to fill in for missing cases (Royston, Reference Royston2004). Twenty imputation samples are created using Stata's ‘mi’ procedure. We use all cases for imputation including those having missing values on the dependent variable; then we exclude such cases from the analysis (Von Hippel, Reference Von Hippel2007). The final sample size is 1,658, 3,198 and 790 for HKPSSD, CFPS and TSCS, respectively.

Measurement and method

The dependent variable, subjective wellbeing, is measured by happiness. This measurement is both valid and comparable. It is well documented that happiness, though not perfectly, does reflect respondents’ feelings of wellbeing and capture a substantial amount of variance (Veenhoven et al., Reference Veenhoven, Ehrhardt, Ho and Vries1993). Researchers claim that the factors that normally determine how happy people feel, such as making a living, family life and health, are similar across societies. Hence, answers to a happiness question are comparable although the question leaves everyone free to define his or her wellbeing (Gundelach and Kreiner, Reference Gundelach and Kreiner2004). We standardised the happiness scores in this analysis. As a sensitivity check, we measured happiness with a dichotomous variable. It equals 1 if the respondent reported ‘very happy’ and ‘happy’ on a five-point scale (the CFPS and version A of the TSCS) or ‘extremely happy’, ‘very happy’ and ‘happy’ on a seven-point scale (HKPSSD and version B of the TSCS). We find no significant differences in results between the two measurements (results not shown).

We classify the living arrangement into five categories: living alone, living independently with a spouse, living with children (two-generation family), living with children and grandchildren (three-generation family) and ‘generation-skipping family’. The last group consists of grandparent(s) and non-adult grandchildren but no members of the middle generation. This new form of household has rapidly emerged in the past two decades in mainland China because of increasing internal migration (Ren and Treiman, Reference Ren and Treiman2015). Many children have been left behind or sent back to live with grandparents by parents who are too busy to take care of their children. We exclude 92 respondents living with others (i.e. uncles/aunties, nephew/nieces) rather than immediate family members (31 from HKPSSD, 31 from CFPS and 30 from TSCS) because they account for a relatively small proportion of all cases. As a sensitiveness check, we include this category in the analysis and find consistent results.

Social participation is measured by a dummy variable, which equals one if the respondent participated in any organisation, such as fraternity groups, service clubs, political clubs, labour unions, religious groups, sports groups, literary, art, discussion or study groups, and hobby clubs. This measurement is based on group membership. One may argue that intensity (i.e. time spent on participation or role in the organisation) is a more important dimension of social participation (Maier and Klumb, Reference Maier and Klumb2005). However, membership is the only information about participation collected by the three surveys. Previous studies revealed that membership captured the effect of social participation to a large extent, although it is an imperfect measure (Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010).

The control variables include individual monthly income, whether the respondent completed senior high school education, labour market participation, self-reported health status and self-assessed social status. The income includes all kinds of financial sources that the respondents received, including pension, support from family members, social security allowance and investment revenues. The TSCS offers only income categories, so we calculate individual income by taking a mean of each category. We calculate the standardised scores for individual income, self-reported health status and social status to make them comparable across different samples. We also control for a set of demographic characteristics, including age, gender and marital status. Marital status is a dichotomous variable that equals 1 if the respondent is married. We are aware that the absence of a spouse due to divorce, separation or death may have different implications for the subjective wellbeing of the elderly (Stack and Eshleman, Reference Stack and Eshleman1998). The divorced and separated older people only account for 2.4, 1.7 and 1.9 per cent in the Hong Kong, urban China and Taiwan sample, respectively. Thus, we do not make a distinction between divorce, separation and widowhood in the analysis.

We use ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to estimate the association between living arrangement, social participation and subjective wellbeing among elderly Chinese. We run separate models for each society, and then use the post-estimation Wald test to investigate whether the associations differ among societies at different levels of socio-economic development.

Results

Descriptive evidence

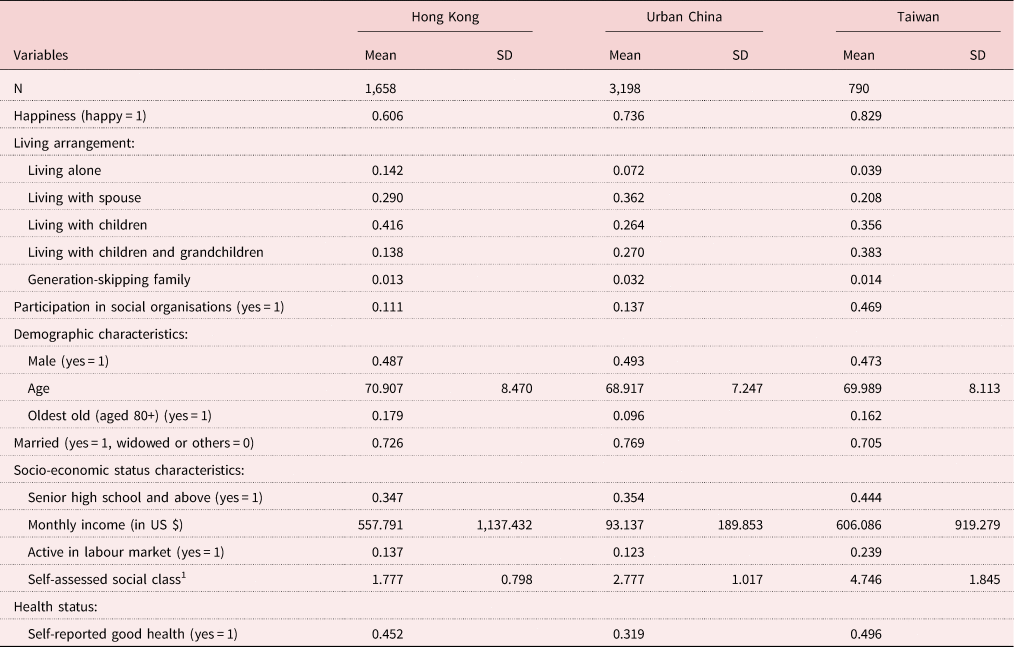

Table 1 provides a comparative profile of the elderly in the three Chinese societies. The aged in Taiwan seem to enjoy better psychological wellbeing than their counterparts in Hong Kong and urban China, with 83 per cent of them reporting they were happy. Hong Kong is most developed, but nearly 40 per cent of its elderly reported feeling unhappy. In general, the elderly in Hong Kong live more independently than their counterparts in urban China and Taiwan: 14 per cent of the senior people in Hong Kong live alone. The proportion is twice as high as that in urban China and three times as high as that in Taiwan. Living alone is rare among the Taiwanese elderly (3.9%). One possible explanation is that Taiwanese people attach more significance to the traditional family values, and they are more likely to live with and take care of their older family members compared with their counterparts in Hong Kong and urban China. We find that 42 per cent of the elderly in Hong Kong live with their adult children. The percentage is the highest among the three societies. Hong Kong is notorious for its high housing prices. Many young people cannot afford to rent, let alone to buy, an apartment, and have no choice but to live with their parents even after they get married. Besides, as is the case in other developed societies, late marriage has become a common practice in Hong Kong. The median age at first marriage was 29.1 for Hong Kong women and 31.2 for men (Hong Kong SAR Census and Statistics Department, 2015; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Wu and He2017). Young people have been postponing their plans to start family.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the elderly (60+) in Hong Kong, urban China and Taiwan

Notes: 1. Self-assessed social class is an ascending five-point scale (1 = lower class, 5 = upper class) in the HKPSSD and the CFPS. It is a ten-point scale in the Taiwan Social Change Survey where 1 is the lowest class and 10 is the highest class. SD: standard deviation.

Sources: The 2011 wave of the HKPSSD (2011), CFPS (2010) and TSCS (2010). Survey.

The traditional multigenerational family is most prevalent in Taiwan, in which three-quarters of the elderly live in two- or three-generation families. The percentage of the elderly living in multigenerational households is nearly identical in urban China and Hong Kong. The difference is that less than half of those in urban China live in two-generation families, but more than three-quarters of those in Hong Kong live in two-generation families. The findings suggest that, compared with their counterparts in Hong Kong, young people in urban China are more likely to move out of their parents’ house when they get married or find a job. They also have a higher tendency to live with their parents again for seeking assistance with childbearing when they have children (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Xie and Yu2011).

The level of social participation is higher in Taiwan than in urban China and Hong Kong: 47 per cent of the Taiwan elderly have taken part in a social organisation. This may be due to high religious participation, especially high participation in folk religion in Taiwan (Hu and Yang, Reference Hu and Yang2014). In this study, nearly half of the Taiwan elderly who have joined social organisations were members of religious groups.

Living arrangement and subjective wellbeing

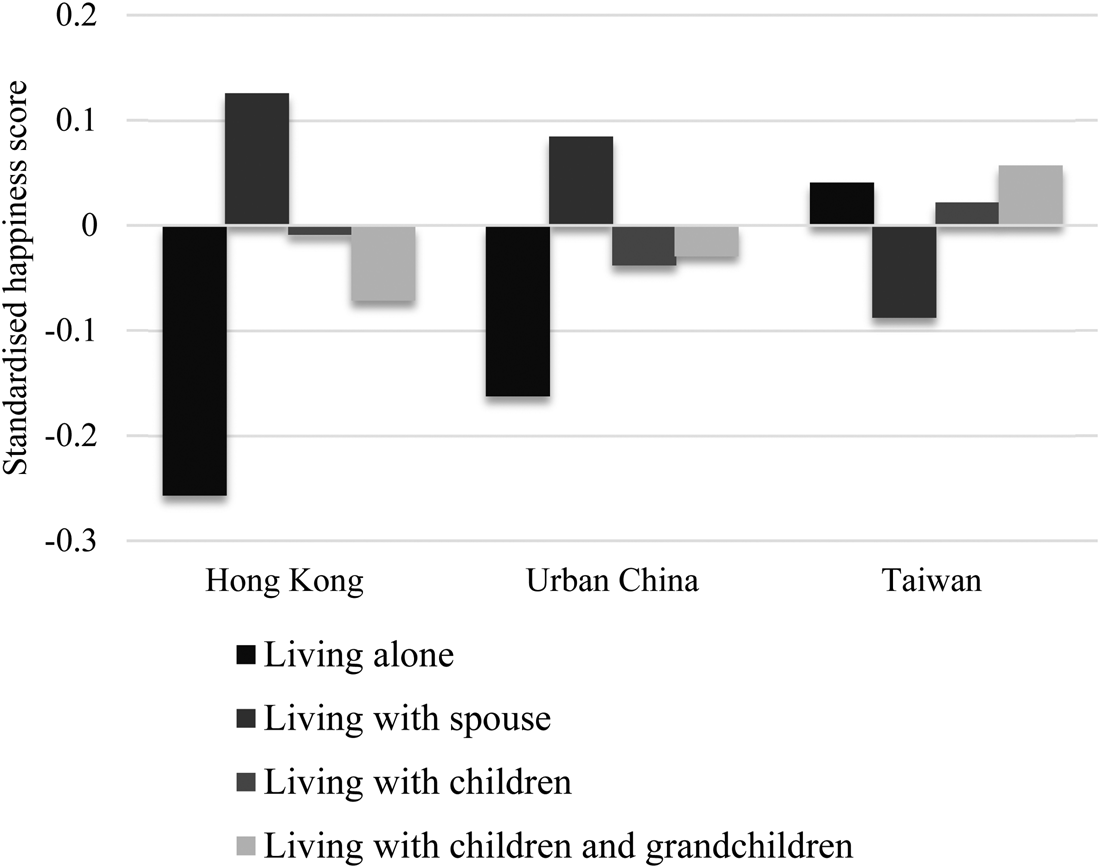

We begin with delineating subjective wellbeing of the elderly adopting various living arrangements in three Chinese societies. Figure 1 shows that in Hong Kong and urban China, the elderly living with a spouse independently reported the highest level of happiness. Those living alone experienced the worst emotional status. Taiwan elderly are significantly different from their counterparts regarding their preference for multigenerational co-residence. They are more likely to feel happy when they live with the next generations, especially with both children and grandchildren. Senior people living alone in Taiwan reported a relatively higher level of happiness than those living with family members. This may be attributed to the small sample size of this category (N = 30), rendering the result sensitive to within-category variation. Figure 2 shows the differences in subjective wellbeing between the elderly who are engaged and not engaged in social activities. Social participation seems to bring greater benefit for the elderly in Hong Kong than those in urban China and Taiwan.

Figure 1. Living arrangement and subjective wellbeing among the elderly in Hong Kong, urban China and Taiwan.

Sources: HKPSSD (2011), CFPS (2010), and TSCS (2010).

Figure 2. Social participation and subjective wellbeing among the elderly in Hong Kong, urban China and Taiwan.

Sources: HKPSSD (2011), CFPS (2010), and TSCS (2010).

To understand better the association between living arrangement and subjective wellbeing, we conduct OLS regression analysis. Results in Table 2 show that, compared with living with younger generations, living independently with a spouse is associated with a higher level of happiness in both Hong Kong and urban China than in Taiwan. The cross-model comparison shows that the difference is statistically significant (p = 0.022). Hong Kong elderly report the highest level of happiness when they live with a spouse. Their happiness reduces by 0.211 standard deviations when they live with their grown-up children (Model 1a in Table 2). There is no negative association between living with the younger generation and psychological wellbeing among the Taiwanese elderly (Model 3a in Table 2). Hypothesis 1a is thus supported.

Table 2. Coefficients of ordinary least squares regression for happiness on living arrangement and social participation among elderly in Hong Kong, urban China and Taiwan

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. Ref.: reference category.

Sources: HKPSSD(2011), CFPS (2010) and TSCS (2010).

Significance levels: † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Living in a three-generation family is linked with the highest level of happiness among the Taiwanese elderly. However, it may be the worst situation for the elderly in Hong Kong. One possible explanation is that Taiwan preserves more traditional family values than Hong Kong and urban China. Multiple generations living together are considered the greatest source of joy for old people in traditional Chinese society. We note that the multigenerational co-residence and its consequence may be affected by housing conditions. As a robustness check, we control per capita living space for the Hong Kong and urban China samples. The results show that the elderly in Hong Kong and urban China are happiest when they live with a spouse independently even after the living space is taken into consideration (see Table S2 in the online supplementary material). The findings supported Hypothesis 1b, namely in more traditional Taiwan, the elderly are more likely to enjoy emotional benefit from living with their grandchildren than in Hong Kong and urban China.

Social participation and subjective wellbeing

Table 2 shows that the association between social participation and happiness is stronger in Hong Kong than in mainland China and Taiwan. The cross-model comparison reveals that the difference is statistically significant (p = 0.033). Model 1b in Table 2 shows joining social organisations is associated with a 0.19 standard deviation increase in happiness among Hong Kong elderly. There is no such association in urban China and Taiwan. The results lend support to our second research hypothesis stating that social participation plays a more crucial role in more modernised societies.

We do not observe a significant association between social engagement and subjective wellbeing in urban China. Other than its relatively lower development level, it may also be related to the unique nature of social organisations there. The Chinese government has adopted restrictive regulations on the registration of social organisations so grass-roots, self-initiated organisations find it difficult to gain legal status and autonomy. The social organisations may be less effective in generating social capital such as social support and self-fulfilment that would improve subjective wellbeing. We investigate whether the linkage between social participation and subjective wellbeing varies by living arrangement. The results indicate that the elderly living alone do not benefit more from taking part in social organisations in the three societies. One reason is that the solo-living elderly face more obstacles such as financial strains and accumulative depression that reduce subjective wellbeing than those living with others.

We further test our results using the vast regional disparities in urban China as a proxy for the different levels of socio-economic development. We divide urban China into two sub-samples: the four municipalities with higher economic development level (i.e. Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, Chongqing) versus the rest of urban China. Table 3 shows that, as a community in urban China becomes developed, the association between living with adult children and subjective wellbeing may decline. The results suggest that the determinants of happiness may become more similar between urban China and Hong Kong, as the mainland's economy continues to develop.

Table 3. Coefficients of the ordinary least squares regression for happiness on living arrangement and social participation among the elderly in Hong Kong, and developed and less-developed areas of urban China

Notes: Standard errors are in parentheses. Ref.: reference category.

Sources: HKPSSD (2010); CFPS (2010).

Significance levels: † p < 0.1, * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Discussion

How to meet increased demand for elderly care has become challenging for many countries, especially developing countries, where socio-economic development has not kept pace with the rapid population ageing. Population ageing in Chinese societies has been accompanied by a substantial change in the provision of elderly care. In traditional Chinese culture, the family is the fundamental platform for supporting the elderly (Chu et al., Reference Chu, Xie and Yu2011). However, the fertility rate has dramatically declined in the past four decades, which indicates shrinking support from the younger generations. When families are unable to provide the necessary support for the elderly, non-kinship social networks would become a viable substitute.

Sociologists focusing on the determinants of psychological wellbeing claim that the association between multigenerational co-residence and emotional wellbeing evolves with socio-economic development (Chen and Short, Reference Chen and Short2008; Yamaoka, Reference Yamaoka2008). The effect of social participation on subjective wellbeing would gradually surpass that of co-residence with children as a society attached less importance to the traditional values (Chen and Short, Reference Chen and Short2008; Yamaoka, Reference Yamaoka2008). In this study, we test this conjecture by comparing Hong Kong, urban China and Taiwan. In contrast to previous studies of cross-country comparison, the three Chinese societies obviously share similar cultural characteristics. Such a comparison can provide more robust evidence as unobserved social and cultural heterogeneity can be controlled to a great extent.

We find that living independently with a spouse is more likely to be considered the best living arrangement in a more-developed Chinese society (i.e. Hong Kong) than in relatively more-traditional ones (i.e. urban China and Taiwan). The association between social participation and subjective wellbeing is stronger in the former than in the latter. The findings suggest that the importance in traditional patterns of shared residence between older parents and their adult children for the elderly's subjective wellbeing are likely to decrease as societies develop, where the social and communal life is likely to become increasingly important.

This study contributes to the literature on living arrangment and subjective wellbeing by showing that the impacts of multigenerational co-residence are embedded in cultural and socie-conomic context. Multiple generations living together is often considered to be important for the elderly because it is a platform for exchange of material, social and emotional support between the older parents and the younger generations (Gierveld et al., Reference Gierveld, Dykstra and Schenk2012). Several recent studies have attempted to establish the causal effect of co-residence with children on wellbeing of the elderly. However, they often reported inconsistent results (Do and Malhotra, Reference Do and Malhotra2012; Johar and Maruyama, Reference Johar and Maruyama2014; Courtin and Avendano, Reference Courtin and Avendano2016). Some scholars claim that whether living with adult children could benefit the older parents greatly depends on the flow of exchanged support (Grundy, Reference Grundy2005; Smits et al., Reference Smits, Van Gaalen and Mulder2010). As the economic insecurity of younger cohorts increases, a growing number of adults choose to stay with their parents, which may bring an extra financial and pychological burden on the elderly (Kaplan, Reference Kaplan2012; Kahn et al., Reference Kahn, Goldscheider and García-Manglano2013). The findings of this study suggest that family-oriented cultural norms which emphasise collective family goals are helpful to avoid the dark side of multigenerational co-residence. However, the importance of living with children would eventually decrease as a society becomes more developed and modernised.

Notably, there are some limitations to this study. First, we use a cross-sectional design to understand the associations between living arrangement and subjective wellbeing, as well as the relationship between social participation and happiness. Interpretation of the results may encounter challenges from selection or omitted variable biases. For instance, a positive parent–child relationship usually predicts an increased likelihood of co-residence with children, as well as the happiness of older parents (Reczek and Zhang, Reference Reczek and Zhang2016). We expect that the panel data-sets across Chinese societies that share the same themes and measurements could provide a useful next step. Qualitative studies are also needed in the future to understand the micro-level mechanisms of living arrangements, and the social process through which social participation affects subjective wellbeing. Second, social participation is measured with group membership, because membership is the only information about participation collected by all the three surveys. Although previous studies revealed that membership captured the effect of social participation to a large extent (Levasseur et al., Reference Levasseur, Richard, Gauvin and Raymond2010), we are fully aware that intensity of participation (i.e. time spent on participation or role in the organisation) is also a crucial dimension of social participation that predicts the subjective wellbeing (Maier and Klumb, Reference Maier and Klumb2005). Thus, we call for more detailed measurements in future research. Further studies are also needed to assess the impact of different kinds of activities and how their consequence varies by health capacity and socio-economic status.

Our study by no means implies that elderly Chinese are not inclined to be taken care of by their children. As previous studies have shown, family-focused networks have remained relatively stable and continue to provide many people in later life with substantial levels of social support (Suanet and Antonucci, Reference Suanet and Antonucci2017). However, such networks endure challenges brought by a decrease in fertility and traditional family norms. Our findings highlight that social participation plays an increasingly important role in promoting the elderly's subjective wellbeing as Chinese societies become further developed. Thus, the government may provide more opportunity for older people to take part in various social and cultural activities. For instance, the Hong Kong government has rapidly increased expenditures on neighbourhood-based elderly care networks in recent years (Hong Kong SAR Social Welfare Department, 2016). A growing number of neighbourhood elderly centres were built to encourage social participation by providing a place for social contact and organising various recreational, social or educational/developmental activities. The elderly who enjoy better access to such resources reported a lower level of depression (Miao et al., Reference Miao, Wu and Zeng2018). Our study in Shanghai also reveals that older adults who frequently interact with their neighbors and participate in voluntary activities may perceive an increased level of social cohesion and enjoy improved mental health (Miao et al., Reference Miao, Wu and Sun2019). Besides psychological benefits, older people can contribute their lifetime of experience and knowledge to the community through active social participation. An active and productive life, in turn, may improve their physical and psychological wellbeing.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19001272

Author contributions

JM interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. XW is the Principal Investigator of the HKPSSD. He designed and supervised this study and revised the manuscript.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (RGC) through the Collaborative Research Fund (CRF) “Community and Population Aging” (C6011-16GF). The HKPSSD data collection was conducted by the Center for Applied Social and Economic Research (CASER) at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST), with funding support from the RGC Central Policy Unit's Strategic Public Policy Research Scheme (grant number HKUST6001-SPPR-08).