Introduction

Peritonsillar abscess, or quinsy, is one of the commonest emergency presentations to ENT departments, and is the most common deep tissue infection of the head and neck.Reference Galioto1 Traditionally, after confirming the diagnosis and anaesthetising the pharynx with a topical agent, tongue depressors are used to control the tongue. Then, either a scalpel can be used to make an incision or a needle inserted to aspirate the pus. Peritonsillar aspiration and incision and drainage have equivalent efficacy, are both well-accepted treatment options for quinsy, and are performed globally.Reference Maharaj, Rajah and Hemsley2 Prerequisites to performing the procedures safely are adequate lighting and access, both of which can be a challenge in an awake patient who is in pain and has trismus.

While junior doctors in the ENT team are taught to diagnose and drain quinsies as a part of their training, peritonsillar aspiration or incision and drainage can be difficult learning and teaching experiences. Even in optimal conditions, it is near impossible for more than one practitioner to view the pharynx simultaneously. This creates obvious difficulties for a trainer to demonstrate the procedure to their trainee, observe them perform it and then provide corrective advice in real-time. This lack of visualisation can often make trainers hesitant to let junior doctors perform the procedure.

In order to counter these difficulties, we have adopted the routine use of flexible video endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of peritonsillar abscess; in our department, this serves both as a therapeutic adjunct and as a training tool.

Materials and methods

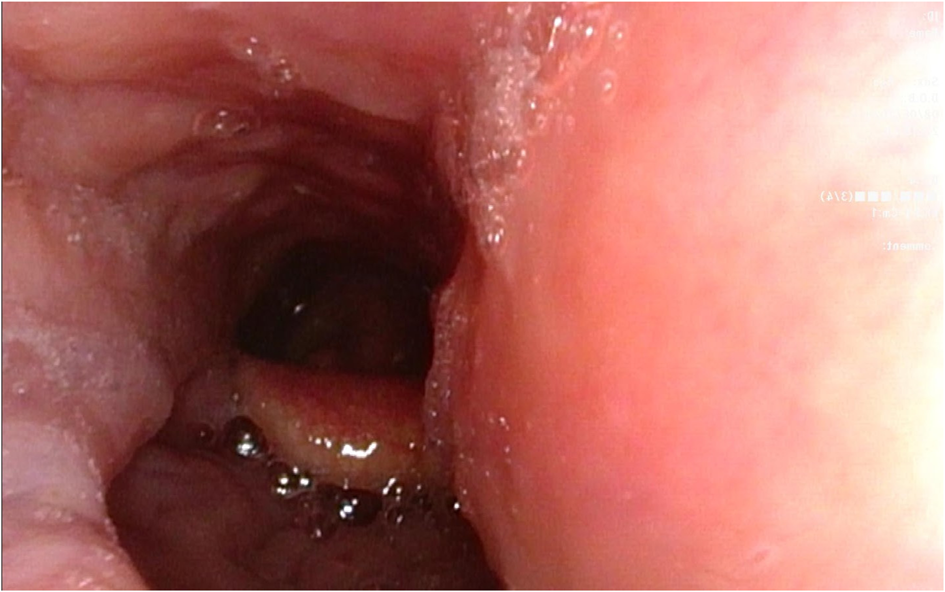

The initial examination to provisionally diagnose a quinsy is carried out in the traditional bedside manner. The patient is then prepared for the procedure by spraying a topical local anaesthetic agent on the anterior tonsillar pillar. The procedure is performed with the patient upright in a seated position, on a chair with fixed legs and a backrest. The flexible video endoscope, with its image displayed on a monitor, is introduced into the oral cavity by the assistant and the diagnosis confirmed (Figure 1). We use a 3.2 mm diameter Olympus© Flexible Video Endoscope (ENF-VH model) within our unit, and a disposable Ambu® aScope™ rhinolaryngoscope is used for patients in the emergency department or outside our own ward. At this time, a further injection of the local anaesthetic can be performed at the intended site of puncture if needed.

Fig. 1. Endoscopic view of left-sided quinsy in a patient with severe trismus that made traditional oropharyngeal examination difficult.

The surgeon performing the procedure sits opposite the patient, and the assistant manipulating the endoscope stands beside. The screen is adjusted so that both operators have a clear, uninterrupted view of the procedure. The operating surgeon can carry out the therapeutic procedure under direct vision or fibre-optic view, whichever they prefer (Figure 2). The authors routinely use an 18 G blunt needle attached to a 10 ml syringe for aspiration. A piece of 2.5 cm width tape is applied to the base of the needle, which serves as a depth gauge (Figure 3). The aspiration can be followed by a stab incision with a knife and further opening of the peritonsillar space with artery forceps, if needed.

Fig. 2. Placement of a video endoscope along the mucosal surface of the cheek, allowing room to manoeuvre the needle during peritonsillar aspiration under excellent lighting conditions.

Fig. 3. A 2.5 cm tape acting as a guard, allowing the trainer to be confident that the needle tip is at an appropriate depth while pus is aspirated.

After the procedure, the endoscope is passed through the nasal cavity, and the pharynx and larynx are examined to rule out deeper extension of the abscess (Figure 4). Still images are recorded before and after the procedure, and added to the medical records for future reference; a copy can be provided to the patient if requested.

Fig. 4. Transition to nasal endoscopy allows examination of the larynx – the image shows a left-sided bulge in the lateral pharyngeal wall caused by extension of the quinsy into deep neck spaces.

Discussion

Peritonsillar aspiration or incision and drainage in patients with quinsy can provide rapid relief from pain and discomfort. In addition, timely diagnosis and treatment is key in reducing the risk of deep neck space infection in the retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal spaces; such infection is associated with significant morbidities, including airway compromise, descending mediastinitis and Lemierre's syndrome.Reference Maharaj, Rajah and Hemsley2

Many methods, some more creative than others,Reference Bakir, Tanriverdi, Gün, Yorgancilar, Yildirim and Tekbaş3–Reference Kataria, Saxena, Bhagat, Singh, Kaur and Kaur6 have been described to enhance access, or improve visualisation and safety in the context of quinsy – this is indicative of the universal difficulties experienced by practitioners. While our method of oropharyngeal endoscopy mandates two practitioners and relies on equipment that may not be readily available in all healthcare settings, we believe it provides several important advantages for patients, trainers and trainees, as highlighted below.

Trismus

This is one of the hallmark features of quinsy, and almost all patients will present with trismus of varying degrees. It can impede access to the pharynx, and limit conventional oropharyngeal examination with a tongue depressor and headlight. The use of a flexible video endoscope provides an elegant solution to this issue. It allows detailed examination in the presence of even the most severe trismus, as most endoscopes are less than 5 mm in diameter and can be easily passed between the teeth. The endoscope itself is not a hindrance to visualisation, even in limited space, when positioned laterally along the mucosal surface of the cheek. From this position, it can be manoeuvred easily to provide adequate lighting and imaging at the time of drainage.

Lighting

By its very nature, the endoscope's powerful light source (the authors use the light-emitting diode based Olympus© CV-170 imaging platform) provides better lighting compared to a traditional headlight. Moreover, the endoscope can be positioned closer to the area of interest for better illumination, allowing for a more detailed inspection.

Supervision, teaching and training

Despite best efforts, it is near impossible for more than one surgeon to simultaneously view the oropharynx adequately using traditional examination with a headlight. This can make teaching particularly difficult, as the trainer is unable to easily orient the trainee to view altered anatomy and specific areas of interest.

Further, despite attending training and simulation courses, it can be daunting for inexperienced practitioners to perform the procedure independently, especially with the awareness of potential complications, such as carotid artery injury. Having the unobstructed supervision of a trainer and real-time feedback throughout the procedure is invaluable, and can help avoid errors and complications. The live endoscopic view displayed on the monitor is an ergonomic method for multiple practitioners to simultaneously view the procedure (i.e. trainees can observe the procedure being performed by a colleague). These videos can also be recorded and revisited for the purpose of training others at a later date.

Trainers themselves may feel more confident in letting the trainees lead the procedure while they guide them through the steps and correct the site, angle or the depth of the needle, as needed, under uninterrupted endoscopic vision. Using the tape guard as a reference point, the trainer can be confident that the needle does not enter into deeper spaces of the oropharynx.

Extended pharyngeal and laryngeal examination

Deep neck space infection is a recognised complication of pharyngeal infections.Reference Kataria, Saxena, Bhagat, Singh, Kaur and Kaur6 It can be difficult to rule out such infections by routine oral cavity examination with a tongue depressor. Having the patient and practitioners set up for endoscopy easily allows for a seamless transition to nasal endoscopy, and the opportunity for further examination of the pharynx and the larynx, to rule out extension of the collection into parapharyngeal or retropharyngeal spaces.

Recording, review and documentation

Most endoscopic stacks will have recording functionality for still and/or video images. This gives the operator the ability to document their findings, the procedure and the result. This serves several purposes, as follows. First, replaying captured images to the patient forms an important part of the therapeutic interaction. They have a better understanding of their pathology and are reassured to see the results of the intervention, especially because symptoms following the treatment can continue for several days. Second, photographic documentation of findings and treatment in the medical record has obvious advantages when communicating with other healthcare professionals. Third, in cases where unusual findings are encountered or complications from the procedure are experienced, images can be examined by more senior clinicians for review and feedback.

Infection control

ENT practitioners are at particularly high risk of contracting the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) from infected patients (who may be asymptomatic), through inhalation or the ocular projection of inoculated respiratory droplets, while manipulating the oropharyngeal cavity during peritonsillar aspiration.Reference Givi, Bradley, Chinn, Clayburgh, Iyer and Jalisi7 Employing a video endoscope allows the operator to sit to the side and further away from the patient, in contrast to traditional methods. This limits their direct exposure to droplet secretion and aerosolised material. This is in line with the guidance issued by both UK and European authorities, which recommend video monitoring for endoscopy wherever possible in the context of the coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19) pandemic.Reference Couloigner, Schmerber, Nicollas, Coste, Barry and Makeieff8,9

Conclusion

Oropharyngeal endoscopy as outlined above is clearly an invaluable training tool, having proven excellent in training junior colleagues within our department. In addition, even experienced colleagues have appreciated the level of detail possible in oropharyngeal examination, especially in difficult cases. This technique is of particular importance in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, as it presents a safer alternative to traditional methods for practitioners carrying out a procedure with a high risk of viral transmission. We fully advocate this technique as both a training tool and a therapeutic adjunct.

Competing interests

None declared