Are policymakers able to address citizens’ needs and requests? Without a doubt, most citizens would answer this question negatively: policymakers do not care about the priorities of public opinion and there is an increasing distance between the policies signalled as the most important by citizens, on the one hand, and actual government policy decisions, on the other (Chaqués Bonafont and Palau Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011). However, this perception has been proven wrong: indeed, many authors have demonstrated that policymakers are very concerned about what citizens want (Manin et al. Reference Manin, Przeworski and Stokes1999). Furthermore, both the legislative behaviour of parties and the issues that they emphasize in their election manifestos are influenced by voter policy priorities (Adams et al. Reference Adams, Clark, Ezrow and Glasgow2004; Ezrow and Hellwig Reference Ezrow and Hellwig2014; Klüver and Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2017).

In line with this, this article compares the policy priorities of public opinion and actual legislative production in Italy, Spain and the UK from 2003 to 2012. The main aim of this article is, therefore, to ascertain whether Italian, Spanish and British policymakers have been paying attention to the issues signalled as priorities by their respective citizens over the course of 10 years characterized by huge political and economic turmoil. It also aims to explore to what extent variations in the degree of correspondence between the public agenda and the policy agenda depend on (a combination of) politico-institutional and contextual factors.

After a long period characterized by a relative lack of interest in the topic, scholars have started to pay more attention to the alignment between citizens’ policy priorities and government legislation (Bevan and Jennings Reference Bevan and Jennings2014; Klüver and Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2016; Lindeboom Reference Lindeboom2012; Mortensen et al. Reference Mortensen, Green-Pedersen, Breeman, Chaqués Bonafont, Jennings, John, Palau and Timmermans2011). This renewed interest originates in the well-known work of Frank Baumgartner and his colleagues on the comparative analysis of policy agendas (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen and Jones2006): more and more scholars now analyse the extent to which policy agendas differ between countries, how much they match public opinion priorities and preferences (Esaiasson and Wlezien Reference Esaiasson and Wlezien2017; Wlezien and Soroka Reference Wlezien and Soroka2016), and which factors have an impact on these dynamics. In these terms at least, this article is anything but exceptional.

Yet the originality of this work is threefold: first, focusing on (among others) the Italian case is in itself a contribution, as most empirical analyses of the link between political activities and public priorities deal with the US and, more recently, the UK (Jennings and John Reference Jennings and John2009; John et al. Reference John, Bertelli, Jennings and Beavan2013), Spain (Chaqués Bonafont and Palau Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011) or the Netherlands (Lindeboom Reference Lindeboom2012). In other words, to the best of my knowledge, this is the first time that the level of correspondence of citizens’ priorities and government legislation in Italy has been empirically analysed and measured.Footnote 1

Simply adding the Italian case to the existing literature would not be a sufficient contribution. Thus, the second (and main) added value of this article is theoretical. More precisely, in a world where social phenomena are generally collinear and clustered, it is unlikely that a particular phenomenon is caused by a unique explanatory factor, and this is even more the case for the relationship between citizens’ priorities and government legislation, which is undoubtedly a very complex political process (Wlezien Reference Wlezien2016). Therefore, in this study, I present a combinatory and equifinal logic of explanation: whether governments address citizens’ priorities depends on the combination of multiple conditions rather than on the ‘net effects’ of different variables.

The combinatory nature of the analytical framework requires a methodological approach that is completely new within the literature on responsiveness, and here lies the third added value of this article; indeed, in order to unravel causal relationships, I run a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) in which causal conditions are represented by politico-institutional and contextual factors, while the outcome consists of the degree of overlap between public opinion priorities and legislation.

This article is arranged as follows: in the next section I briefly review the most relevant literature on policy responsiveness, with a particular focus on those studies that deal with the correspondence of the policy priorities of citizens and policymakers; then, in the third section, I develop two hypotheses as to how that same correspondence is related to the combination between politico-institutional and contextual factors. The fourth part explains the methodology and data. Based on this, the fifth section offers a descriptive analysis of both dynamics – public opinion priorities and government legislation – in each country, and shows the correspondence between the two. The sixth section consists of the QCA, while in the last part of the article I offer some concluding remarks and propose directions for future research.

How and why policymakers (do not) respond to public opinion priorities

How able are political parties to interpret the needs and requests of citizens? There is no doubt that this represents a ‘traditional’ research question in political science; yet, among the different conceptualizations that can be attributed to the complex and multidimensional phenomenon which ‘responsiveness’ certainly is (Wlezien Reference Wlezien2016), scholars have started analysing the level of correspondence between public priorities and government legislation only very recently (Bevan and Jennings Reference Bevan and Jennings2014; Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005; Blais and Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006; Chaqués Bonafont and Palau Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011; Klüver and Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2016; Lindeboom Reference Lindeboom2012).

Yet the necessity of a responsive government which is ‘in tune’ with the citizens it ought to represent is absolutely central in the analysis of any democratic system: one of the main functions performed by political parties (and, in turn, governments) in parliamentary democracies, in fact, is linking citizens and policymakers (Dalton et al. Reference Dalton, Farrell and McAllister2011). Being intermediate bodies between the electorate and the state, parties’ varying abilities to interpret citizens’ priorities and then transform those same priorities into public policies might tell us a great deal about the quality of the democratic political system in which they operate (Mansergh and Thomson Reference Mansergh and Thomson2007: 311).

Of course, a government that simply takes care of citizens’ priorities and, in turn, legislates on issues that are of broad concern within public opinion cannot be considered as fully responsive, nor fully congruent with citizens’ preferred policies: the correspondence of priorities, policy responsiveness and policy congruence are not synonymous (Wlezien Reference Wlezien2016: 562–564). In fact, the alignment of priorities does not necessarily lead to the successful interpretation of citizens’ needs and requests. For example, citizens might be very concerned about public health, yet have a clear preference for extending public health coverage; in that particular case, the passing of a new bill on public health would certainly be a signal of attention (i.e. correspondence of priorities), but if that same bill had the aim of cutting public health coverage, citizens’ preferences and the government’s choice would go in opposite directions. Similarly, evidence of policy responsiveness does not mean that public preferences and policies are actually congruent: for congruence, we need to observe not only a positive relationship between preferences and policies, but an actual match. The ideal policy points of government on one side and citizens on the other should overlap perfectly.

More precisely, therefore, we can conceptualize the correspondence of priorities as a necessary but insufficient precondition for policy responsiveness, which in turn is a necessary but insufficient precondition for policy congruence. In other words, those same three concepts can be depicted as three concentric circles. This conceptual distinction helps in delimiting the aim and scope of this work, which focuses on the correspondence of citizens’ priorities with government legislation as a first step towards both policy responsiveness and congruence. While I do believe that this still represents an interesting topic, it is also a limitation that cannot be concealed.

Initially, the correspondence between citizens’ priorities and the legislative action of representatives was theoretically assumed rather than empirically demonstrated: politicians who do not represent anyone should have no chance of (re)election (Wlezien Reference Wlezien2004). Even though this assumption appears reasonable, scholars proceeded to its empirical test rather quickly. From this point of view, it is possible to distinguish different approaches on the basis of the level of analysis (micro- or macro-level), and of the temporal focus (static vs. dynamic) (Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005: 380). Micro-level studies generally focus on the correspondence between the votes of individual legislators and the preferences of their respective constituencies (Converse and Pierce Reference Converse and Pierce1986; Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963), whereas macro-level analyses have been carried out on the basis of different comparisons: between citizens’ positions and those of governments (Monroe Reference Monroe1995; Wlezien Reference Wlezien1995) and political parties (Jennings and John Reference Jennings and John2009), as well as between public opinion priorities and the policy agenda (Blais and Bodet Reference Blais and Bodet2006; Chaqués Bonafont and Palau Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011; Klüver and Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2016; Lindeboom Reference Lindeboom2012). With regard to the temporal focus, when scholars realized that causal mechanisms are discernible only by following a dynamic perspective (Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005), the original static approach was very soon abandoned (Page and Shapiro Reference Page and Shapiro1992).

What all these studies demonstrated was that the capacity of policymakers to respond to the preferences (and priorities) of citizens varies across issues, countries and policy venues. These variations depend on a number of factors, the first of which is the institutional arrangements that govern the political system. Indeed, many scholars argued that proportional electoral systems tend to generate more responsive legislatures and governments (Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005; Huber and Powell Reference Huber and Powell1994; Powell Reference Powell2000).

In a recent article dealing with the level of correspondence between citizens’ priorities and governments’ legislation in Spain from 1990 to 2007, Laura Chaqués Bonafont and Anna Palau (2011) focus on four politico-institutional factors favouring that same correspondence: (1) the level of the so-called ‘institutional friction’; (2) the degree of (de)centralization characterizing the issue (and the institutional arrangement of the country under scrutiny, more broadly); (3) whether the government has a parliamentary majority; and (4) whether the parliamentary session is close to elections.

Originally, the concept of ‘institutional friction’ was proposed by Bryan Jones and Frank Baumgartner (Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005): in their view, this is a two-dimensional concept, based on both the transaction costs associated with a particular policy venue and the number of individuals and collective actors whose agreement is required for decision-making. According to Jones and Baumgartner (Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005), as well as to Chaqués Bonafont and Palau (Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011), who built on their work, the higher the number of actors who can act as veto-players, as well as the higher the transaction costs, the lower the government responsiveness, and vice versa.

The same inverse relationship is generally hypothesized as existing between responsiveness and the level of decentralization characterizing the policy issue, too: as Fritz Scharpf (Reference Scharpf1999) originally argued, ‘the increase in the number of governments involved in the policymaking process makes it less clear which government is doing what in relation to specific policy areas’ (cited in Chaqués Bonafont and Palau Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011: 709–710); in these cases, the possibility of resorting to ‘blame avoidance’ strategies, in turn, reduces the incentives for policymakers to pay attention to public opinion.Footnote 2 Therefore, especially in federal systems, the level of correspondence of citizens’ priorities with government legislation will be particularly low in those policy areas where there is overlapping or shared jurisdiction. Moreover, a decreasing level of responsiveness is expected in all those countries that have recently witnessed the consolidation of a multilevel governance system due to the process of Europeanization. In sum, each political system where there has been increasing delegation of powers upwards towards the EU and/or downwards toward sub-national units is expected to show declining responsiveness over time (Chaqués Bonafont et al. Reference Chaqués Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015: 246).

Another factor that is generally considered relevant for responsiveness is the question of whether a government has a parliamentary majority (Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005). A minority government is expected to compromise more with a higher number of parties holding seats in parliament; this, in turn, implies the need to take into account a wider range of preferences and priorities and, as a consequence, to approximate the views of citizens more closely. In other words, there is less pressure on majority governments to widen their policy agenda to take into consideration the needs and requests of other parties, due to their parliamentary self-sufficiency. When this self-sufficiency does not exist, a growing number of parties are involved in the agenda-setting; this, in turn, has remarkable consequences for the number of priorities which enter that same policy agenda and, therefore, for the level of correspondence of legislative action with public opinion priorities.

Finally, contextual factors are also expected to play a role in whether (as well as to what extent) policymakers care about the priorities of public opinion. In this regard, two factors have been particularly scrutinized: the timing of political elections and economic conditions. First, scholars are convinced that elections matter a great deal with regard to responsiveness (Jones Reference Jones1994; Klingemann et al. Reference Klingemann, Volkens, Bara, Budge and McDonald2006; Maravall Reference Maravall1999): before elections, parties are indeed expected to (try to) maximize their chances of re-election by taking into account as many citizens’ priorities and preferences as possible. By the same token, governments that have just been elected are expected to pay special attention to their electoral pledges during the parliamentary session after the election (Chaqués Bonafont and Palau Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011). Second, it has also been demonstrated that economic conditions have a remarkable impact on the governmental agenda (Chaqués Bonafont et al. Reference Chaqués Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015): generally, the diversity of the agenda declines under bad economic conditions. Yet this effect is (much) greater for the symbolic agenda (i.e. prime ministers’ speeches) than for actual legislation: as Chaqués Bonafont and colleagues (Reference Chaqués Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015: 239) clearly stated, ‘the machinery of government continues, no matter what the Prime Minister may be speaking about’.

Overall, what this literature has shown is that politico-institutional aspects have a great impact on responsiveness: proportional electoral systems, institutional friction, decentralization, the timing of elections – all these factors are significantly correlated with the variation in the level of correspondence between the priorities of citizens on the one hand, and government legislation on the other. Yet I believe that whether a factor leads to a correspondence of priorities depends on how that same condition combines with other – potentially relevant – factors. Furthermore, I expect that different combinations of factors may be associated with the same phenomenon – namely the capability of governments to pay attention to their citizens – in different cases. In other words, it is not one single combination of conditions that explains whether policymakers care about public opinion priorities, but, rather, a number of alternative causal paths may exist.

Analytical framework

As noted, scholars have so far demonstrated that responsiveness differs between countries and policy venues. Yet, not all governments within the same country are equally attentive to citizens’ priorities; furthermore, the correspondence of priorities can vary over time for the same government. The argument that this variation only depends on whether those governments are minority governments (Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005), or on whether they are near to elections, is not fully persuasive. There will be other factors influencing the ability of policymakers to pay attention to public opinion priorities. My argument is that the way in which politico-institutional factors and contextual conditions combine with one another has an impact on this dynamic.

As previously noted, the literature has tended to stress five politico-institutional factors: (1) the majoritarian/consensual nature of the institutional arrangement governing the country; (2) the degree of ‘institutional friction’ characterizing the issue; (3) the level of institutional decentralization; (4) whether the government is a minority government; and (5) the timing of elections. However, in my opinion, three of these five factors are not fully persuasive for the analysis developed here.

First, even though many scholars have argued that proportional electoral systems (and, more broadly, consensual institutional arrangements) tend to generate more responsive legislatures and governments (Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005; Powell Reference Powell2000), more recent studies challenge this picture: André Blais and Marc André Bodet (Reference Blais and Bodet2006), for example, have demonstrated that proportional representation does not foster closer congruence between citizens and policymakers. Furthermore, Christopher Wlezien and Stuart Soroka (Reference Wlezien and Soroka2012) confirmed that proportional and majoritarian systems both work to serve representation, but in different ways: the former provide better indirect representation via elections, whereas the latter better direct representation in between elections.

Institutional friction will not be taken into consideration in this article. The reason is very simple: this factor is mainly relevant in assessing the level of responsiveness across policy fields (Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005; Scharpf Reference Scharpf1999) but it has no impact when comparing responsiveness across governments within the same country, or over time (as I do in this article). A slightly different consideration can be identified with regard to institutional decentralization; in fact, within the same country it is possible to find important variations in institutional decentralization over time. However, institutional changes generally take many years to be implemented and, above all, to produce real effects. Furthermore, neither Italy, nor Spain, nor the UK experienced large institutional reforms between 2003 and 2012 – the time span analysed here. Political decentralization thus does not explicitly enter my theoretical framework; however, given the broad bulk of literature that assesses its impact on responsiveness, institutional decentralization enters my QCA as a sort of ‘control condition’. By doing so, it is possible to ascertain whether a decentralized institutional setting – when combined with other factors – represents an environment that does not foster responsiveness, as argued in the literature.

I am also sceptical about the so-called ‘minority government argument’. According to Chaqués Bonafont and Palau (Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011: 711), ‘when the executive does not have a majority … it is expected that a wider range of preferences of different political parties will be accommodated, and the outcome is likely to be closer to the preferences of the majority of the electorate’. However, whether the government is a minority government does not really matter; what matters is the number of parties whose preferences and priorities are taken into account for setting the policy agenda. Consider a case where a minority single-party government faces two parties that are in opposition: in this situation, it is very likely that the party in government only needs to convince one of the two opposition parties to set the policy agenda. And now consider a case where a majority government is sustained in parliament by four parties: in this case, all those four parties set the policy agenda. If we expect – as Chaqués Bonafont and Palau suggest – that the wider the range of preferences accommodated, the higher the responsiveness of the government will be, in the second case we should have a more responsive executive than in the first case.

Thus, the only ‘traditional’ factor that explicitly enters my analytical framework deals with the so-called ‘elections matter’ argument. However, the simple fact that elections are approaching (or have just been held) does not always lead to a correspondence of priorities. It is true that policymakers are expected to (try to) maximize their chances of re-election by taking into account as many citizens’ priorities as possible precisely when elections are approaching. Similarly, it is also true that ‘new’ governments (try to) pay special attention to their electoral pledges precisely at the beginning of their mandate. Yet their capacity to actually do so is crucial. ‘Strong’ governments are better able to follow the abovementioned incentives, whereas potential political contrasts within a ‘weak’ cabinet may be exacerbated precisely because of close elections, thus leading to legislative stalemate and, in turn, less correspondence of priorities. In other words, governments with high decision-making capacities are more likely to take advantage of the electoral moment to legislate more ‘in accordance’ with citizens’ priorities, whereas governments with low decision-making capacities are less likely to do so. Thus, neither high decision-making capacity nor political elections alone is sufficient for a correspondence of priorities; in my view, high decision-making capacity and political elections together seem to be sufficient for it.

Nevertheless, I would like to add an often-neglected factor to this picture: the impact of citizens’ trust in government. In a seminal work published more than 40 years ago, Arthur Miller (Reference Miller1974) hypothesized a link between citizens’ trust, on the one hand, and a government’s ability to produce legislation, on the other. Building on his work, I believe that citizens’ trust in government may also push policymakers to be more or less attentive to the priorities of public opinion: precisely because negative public opinion ‘sentiment’ is likely to lead to electoral losses for parties in office, those same parties may try to counterbalance this negative dynamic through being more ‘in tune’ with the citizens’ priorities. In other words, it appears reasonable that – ‘when things go wrong’ – policymakers might attempt to increase their (slim) chances of re-election by seeking to create a higher level of correspondence between public opinion priorities and legislation. However, this appears to be more reasonable for a government with a high decision-making capacity facing imminent elections than for a government with a low decision-making capacity (at any moment). The former, if it is not under electoral pressure, is less likely to be scared by declining consensus: it has time to rebuild this consensus, as well as the political strength to do so. Where the latter is concerned, on the contrary, negative sentiment by public opinion is more likely to exacerbate political contrasts within the cabinet, leading to legislative stalemate and, in turn, threatening the correspondence of priorities. Therefore, only a growing consensus of citizens around the policies enacted by a government with low decision-making capacity might give rise to a virtuous circle of responsiveness, regardless of when elections are scheduled. In other words, that same government needs citizens’ trust in order to overcome its own ‘weakness’ and legislate in accordance with the priorities of public opinion. Again, neither citizens’ trust in government nor a low decision-making capacity alone are sufficient for a correspondence of priorities; low decision-making capacity and rising citizens’ trust in government together seem to be sufficient for it. Table 1 summarizes the analytical framework.

Table 1 Analytical Framework

From this scheme, it is thus possible to derive two explicit theoretical hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Regardless of citizens’ trust in government, the simultaneous presence of a high government decision-making capacity and political elections to be held in that particular year is sufficient for a correspondence of priorities between citizens and the government.

Hypothesis 2: Regardless of whether elections are held in that particular year, the simultaneous presence of a low government decision-making capacity and rising citizens’ trust in government is sufficient for a correspondence of priorities between citizens and the government.

Both hypotheses explicitly imply conjunctural causationFootnote 3 and equifinality.Footnote 4 Thus, they are perfectly suitable for set-theoretic methods, of which QCA (in all its different variations) undoubtedly is one (Ragin Reference Ragin1987, Reference Ragin2000; Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). Without doubt, the whole model represents an oversimplification of real-world dynamics: it is probably too optimistic to argue that a phenomenon as complex and multifaceted as policymakers’ attention to citizens’ priorities depends only on the conditions considered here (Arcenaux et al. Reference Arcenaux, Johnson, Lindstädt and Vander Wielen2016). Yet my reasonable expectation is that they are able to show a good part of the overall picture.

Research design

This study aims to explain to what extent, and why, Italian, Spanish and British policymakers have (or have not) paid attention to the policy priorities of public opinion between 2003 and 2012. The country selection can easily be justified on theoretical grounds. I compare, first, institutional systems that are variously centralized (the UK) and decentralized (Spain and, to a lesser extent, Italy); second, countries that are traditionally characterized by governments with high (the UK and Spain) and low (Italy) decision-making capacity; third, majoritarian (the UK), ‘quasi-majoritarian’ (Spain) and variously proportional (Italy) systems; fourth, countries that have experienced a deeper economic crisis in recent years and, in turn, a substantial decline of citizens’ trust in government (Italy and Spain), in comparison to another (the UK) where this dynamic has been less pronounced. In other words, the country selection – implying a good deal of variance on the conditions taken into account, as well as controlling for further potential intervening conditions – aims at producing more robust inferences.Footnote 5

The time span, too, is justifiable on theoretical grounds: indeed, I take into consideration a period of huge transformations in Europe, comparing two very different sub-periods of five years: 2003–7 (before the economic and financial crisis) and 2008–12 (throughout the economic and financial crisis). Therefore, the choice of the time span is influenced by the aim of verifying whether that same crisis has had an impact on the ability of policymakers to take care of the needs and requests of citizens.

The level of correspondence between citizens’ priorities and government legislation is analysed using two separate time series of issue priorities: the first is based on the biannual Eurobarometer survey, including the well-known ‘most important issue facing the country’ (MII) question, which is generally used by scholars focusing on public opinion priorities (Jennings and Wlezien Reference Jennings and Wlezien2011); the second consists of the legislative acts initially sponsored by the government and then approved by the parliament.Footnote 6

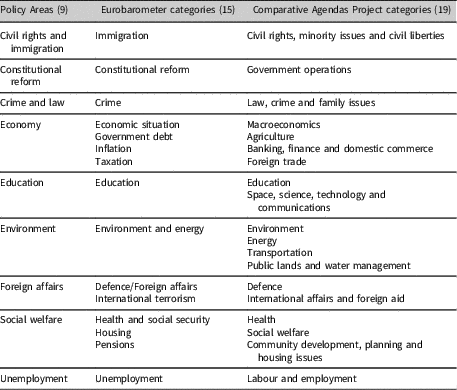

To code legislative activity, scholars tend to resort to the scheme proposed by the researchers of the Comparative Agendas Project (CAP) (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen and Jones2006; John Reference John2006). This scheme was originally developed in the US context to test the punctuated equilibrium theory (Baumgartner and Jones Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993). However, the proposed codebook is neither theoretically constrained nor necessarily linked to the characteristics of the US political system (Baumgartner et al. Reference Baumgartner, Green-Pedersen and Jones2006, 963–969) and scholars recognized its potential for comparative analysis very quickly. The original CAP coding scheme consists of 19 major topic categories and 247 subcategories. However, both CAP categories and Eurobarometer categories have been modified slightly to ensure comparability with one another. On this point, see Table 2.

Table 2 Eurobarometer–CAP Policy Areas

In order to measure the level of correspondence between citizens’ priorities and government legislation, I employ a statistical tool that is frequently used to measure the proportionality between two percentage distributions; the statistical formula, which builds upon the method of least squares, is as follows:

$${\rm Index}\ (0\,{\minus}\,100){\equals}\sqrt {{1 \over 2}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{{\rm i}{\equals}1}^{\rm n} {({\rm x}_{{\rm i}} \,{\minus}\,{\rm y}_{{\rm i}} )^{2} } } $$

$${\rm Index}\ (0\,{\minus}\,100){\equals}\sqrt {{1 \over 2}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{{\rm i}{\equals}1}^{\rm n} {({\rm x}_{{\rm i}} \,{\minus}\,{\rm y}_{{\rm i}} )^{2} } } $$

This index is probably the most common way of calculating average distances and is very frequently used in social sciences.Footnote 7 It ranges from 0 to 100: the lower the index value, the higher the proportionality between the two percentage distributions, and vice versa. More precisely, in this article the two percentage distributions are represented by the public agenda (citizens’ priorities) and the policy agenda (government legislation); therefore, the higher the level of proportionality between the two, the higher the level of correspondence between public opinion and government priorities.

Of course, we cannot expect the policy agenda to be immediately in accord with public opinion priorities: it is simply not possible to legislate ‘in real time’, and at least some time must be allowed to pass. With regard to this, Sara Binzer-Hobolt and Robert Klemmemsen (Reference Binzer-Hobolt and Klemmemsen2005) and Gert-Jan Lindeboom (Reference Lindeboom2012) found empirical support for the generally accepted rule-of-thumb of adopting a one-year lag before public priorities are translated into government legislation.Footnote 8 However, that rule might be inappropriate in analysing a crisis period, when policy decisions are passed more urgently. As a consequence, in this article I decided to adopt a six-month lag: therefore, combinations of country*semester (N=52), and not governments (N=13), are my units of analysis.Footnote 9

As I argued at the start of the article, to the best of my knowledge this is the first time that QCA has been used to study responsiveness. QCA represents a relatively new research approach (Ragin Reference Ragin1987, Reference Ragin2000, Reference Ragin2008; Rihoux and Ragin Reference Rihoux and Ragin2009). Nevertheless, in recent years it has attracted increasing attention within the social sciences (Wagemann and Schneider Reference Wagemann and Schneider2010), and some scholars consider QCA already to be a ‘mainstream method’ in political and sociological research (Rihoux et al. Reference Rihoux, Alamos-Concha, Bol, Marx and Rezsöhazy2013). As QCA scholars repeatedly argue, applying QCA means that the theoretical expectations could (and, in turn, should) be understood as representing necessity and sufficiency relations among sets (Ragin Reference Ragin1987). Moreover, there should be good reasons to believe that the outcome under scrutiny results from the conjunction of several conditions, as well as the possibility that it could derive from more than one causal explanation (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2010, Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). As I argued in the theoretical section, this is the case here: whether policymakers take note of citizens’ priorities depends on a combination of government decision-making capacity, citizens’ trust and the time of elections.

That said, (1) the level of government decision-making capacity originates from the recent government decision-making potential index (GDPI) proposed by Andrea Pritoni (Reference Pritoni2017); (2) whether the crisp condition ‘elections’ is present or absent depends on the fact that national political elections have been held in that country in that particular year; (3) the variation of the level of citizens’ trust in government has been collected thanks to the abovementioned Eurobarometer surveys; (4) the level of decentralization characterizing the country has been operationalized thanks to the well-known regional autonomy index (RAI) recently proposed by Marc Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Marks and Schakel2010).Footnote 10

Descriptive statistics: the evolution of public and policy agendas in the 2000s

As Baumgartner and Jones (Reference Baumgartner and Jones1993) noted, policy agendas are likely to vary both across countries and over time. A particular policy issue may be considered highly relevant in a particular country at a particular time, while receiving little or no attention in another country or at a different moment. Very often, policy agendas change incrementally over years (or even decades), yet there are periods of dramatic transformation that occur suddenly. Generally, huge changes are triggered by external shocks, which therefore tend to operate as detonators.

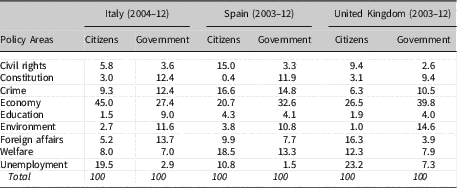

The opinions of citizens are likely to vary in a similar way: indeed, public perceptions of the relevance of issues seem to evolve based on external shocks, too. However, ceteris paribus, public opinion fluctuations are generally considered to be both more frequent and more randomly distributed. In fact, policymakers’ attention is much more characterized by ‘path dependency’ than the preferences and priorities of citizens: governmental agendas are expected to be more stable than the public’s (Breeman et al. Reference Breeman, Lowery, Poppelaars, Resodihardjo, Timmermans and de Vries2009; Jones and Baumgartner Reference Jones and Baumgartner2005).Footnote 11 All this, in turn, makes it hard for government legislation to mirror citizens’ priorities perfectly. On this, see Table 3, which shows how similar the public agenda and the policy agenda have been between 2003 and 2012.

Table 3 Percentage of Attention by Policy Area: Italy, Spain and the UK in a Comparative Perspective (2003–12)

Sources: Author’s elaboration of Eurobarometer data and Comparative Agendas Project data.

Table 3 confirms that there is not always correspondence between the public agenda and the policy agenda: there are topics that are consistently considered to be more relevant by citizens than by policymakers – unemployment and civil rights – and topics that, on the contrary, are consistently considered to be more relevant by policymakers than by citizens – constitutional reform and environment. Moreover, viewed across countries, policy agendas are more similar than public agendas: this empirical finding is not unexpected, giving support to the familiar hypothesis that European countries are substantially interlinked and, in turn, are called to face similar problems at the same time. However, the level of correspondence between citizens’ priorities and government legislation varies considerably across both countries and governments, as well as within the same country over time. See, on this, Figure 1.

Figure 1 Correspondence between Citizens’ Priorities and Government Legislation: Diachronic Trends (2004–12) in Italy, Spain, and the UK Sources: Author’s own elaboration of Eurobarometer data and Comparative Agendas Project data.

Figure 1 clearly shows that the correspondence of priorities varies considerably within the same country over time: in both Italy and the UK, the line follows a fluctuating path, yet it is not possible to see a clear diachronic trend. On the contrary, Spain is characterized by a very neat diachronic tendency: the index of disproportionality decreases over time, showing an increasing level of correspondence between public opinion priorities and government legislation. This finding is interesting because it seems to openly contradict previous research on the topic: in fact, Chaqués Bonafont et al. (Reference Chaqués Bonafont, Palau and Baumgartner2015: 244) recently noted that, in Spain, ‘responsiveness is decreasing over time’. However, their time span is longer than mine, since they analyse more than 30 years of Spanish politics, the period between 1982 and 2013, finding the level of responsiveness in the 1980s and the 1990s decreased in the 2000s, whereas I focus only on the 10 years between 2003 and 2012. While they explain their trends on the basis of institutional reforms implying more decentralization over time and rising Europeanization, neither decentralization nor Europeanization varied greatly in Spain between 2003 and 2012. This probably explains why empirical findings are (apparently) contradictory.

Another interesting consideration can be seen in an analysis of the many ups and downs that follow one another: for example, in the UK the level of correspondence between citizens’ priorities and governmental priorities grows impressively between the second semester of 2011 (the index of disproportionality, in this case, is equal to 47.9) and the first semester of 2012 (disproportionality: 28.5), yet the government did not change (Cameron I), nor can this huge difference be imputed to political elections, which were held in 2010. An even more interesting pattern is observable if we analyse the Italian case between the first semester of 2010 and the first semester of 2011: disproportionality/correspondence of priorities first collapses/goes up, then grows/declines impressively, without any change in the government (Berlusconi IV), or any political elections (held in 2008 and 2013). This clearly means that ‘traditional’ politico-institutional factors are not in themselves a sufficient explanation for variations in the extent to which policymakers pay attention to the priorities of public opinion.

Public opinion priorities and government legislation: a configurational analysis

In this article, I use fuzzy-set QCA (fsQCA) in order to test empirically the theoretical argument that the combination of government decision-making capacity, citizens’ trust and the time of elections plays a crucial role in influencing the level of correspondence between the priorities of public opinion and government legislation. Yet, the ‘elections’ condition is obviously a crisp one: elections are either held or not held in a particular year: no intermediate options are possible.

One of the first steps in each fsQCA is the so-called ‘calibration’ of sets (both conditions and the outcome) (Ragin Reference Ragin2008; Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2012). In this fundamental process – which should be as transparent as possible, and which should be discussed in detail (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2010: 403) – it is particularly crucial to specify qualitative anchors for full membership (1), full non-membership (0) and for the point of maximum ambiguity (0.5).Footnote 12Table 4 summarizes all the choices made (see the online Appendix for all original data and fuzzy values of all cases, as well as for the discussion of the thresholds chosen).

Table 4 Calibration of Sets: Conditions and the Outcome

Sources: Decision-making capacity: government decision-making potential index (GDPI) (Pritoni Reference Pritoni2017). Elections: author’s elaboration. Variation (%) in citizens’ trust in government: Eurobarometer (2003–12). Decentralization: regional authority index (RAI) (Hooghe et al. Reference Hooghe, Marks and Schakel2010). Correspondence of priorities: author’s elaboration on the basis of both Eurobarometer data and Comparative Agendas Project (CAP) data.

Once sets have been calibrated, the second step of each QCA – both crisp-set and fuzzy-set – consists of the analysis of necessity relations, which should always be conducted before the analysis of sufficiency conditions (Schneider and Wagemann Reference Schneider and Wagemann2010: 404). With respect to this, as Table 5 demonstrates, no condition (or its non-occurrence, indicated with the tilde ~) is necessary for the outcome (or its non-occurrence).Footnote 13

Table 5 Analysis of Necessary Conditions. Outcome: Correspondence of Priorities

Subsequent to the analysis of necessity, the empirical test of sufficiency set-relations between (combinations of) conditions and the outcome is conducted through a ‘truth table’. The online Appendix shows the details of the Boolean minimization process, but what is relevant here is to show the intermediate solution formula that derives from that same minimization process (see also Table 6 on this):

$$\eqalignno{ & {\rm Intermediate}\,{\rm solution {\equals}decision{\hbox-}making{^\asterisk}{\sim}\, trust {\plus} trust{^\asterisk}{\sim}\,decision{\hbox-}making {\plus}} \cr & {\rm \,{\sim}\,trust{^\asterisk}{\sim}\,elections {\plus} {\sim}\,decision{\hbox-}making{^\asterisk}{\sim}\,elections} $$

$$\eqalignno{ & {\rm Intermediate}\,{\rm solution {\equals}decision{\hbox-}making{^\asterisk}{\sim}\, trust {\plus} trust{^\asterisk}{\sim}\,decision{\hbox-}making {\plus}} \cr & {\rm \,{\sim}\,trust{^\asterisk}{\sim}\,elections {\plus} {\sim}\,decision{\hbox-}making{^\asterisk}{\sim}\,elections} $$

Table 6 Intermediate Solution: Solution Terms, Consistency, Coverage and Cases Covered

Notes: Solution coverage (proportion of membership explained by all paths identified): 0.745836. Solution consistency (how closely a perfect subset relation is approximated) (Ragin Reference Ragin2008: 44): 0.843632. Raw coverage: proportion of memberships in the outcome explained by a single path. Unique coverage (proportion of memberships in the outcome explained solely by each individual solution term) (Ragin Reference Ragin2008: 86). Empirically contradictory cases are shown in bold.

Theoretically, the (intermediate) solution above means that the correspondence between public opinion priorities and government legislation may be achieved following four different causal paths: first, it is linked to the combination of high government decision-making capacity and declining citizens’ trust in government. This solution term means that ‘strong’ governments try to recover consensus by focusing their legislation on public opinion priorities, regardless of political elections to be held in that particular year. In other words, this path seems to give support to what has been defined in media studies as the ‘permanent campaign’ (Blumenthal Reference Blumenthal1982) – namely governments’ continuous tracking of public opinion polls. When these same governments start losing consensus, they are incentivized to focus on the issues that citizens are concerned about, but only governments with high decision-making capacity have the political strength to do so. Interestingly, this first solution term is very useful to understand the phenomenon of correspondence of priorities in Spain and the UK, whereas its explanatory power is very limited with regard to the Italian case (only the second semester of 2011 in Italy is explained by this path): this is because, in short, Italian governments with high decision-making capacity are very rare (Pritoni Reference Pritoni2017), whereas the level of citizens’ trust in government – in Italy – is characterized by many ups and downs.

Moreover, whether governments take care of citizens’ priorities is also linked to a combination of rising citizens’ trust and low government decision-making capacity. This solution term perfectly resembles my second theoretical hypothesis, which is therefore confirmed by empirical findings: ‘weak’ governments need the support of public opinion to pay attention to citizens’ priorities. This path, in contrast to the previous one, is much more able to explain Italy and, to a lesser extent, Spain, whereas it is completely silent on governments in UK: this is because – as is very well known from the literature on parliamentary governments (Lijphart Reference Lijphart2012; Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002) – all British governments have high decision-making capacity, which mainly derives from their agenda-setting powers and from the fact that they are almost always single-party governments with high internal cohesion.

Third, the correspondence between public opinion priorities and government legislation is favoured by the simultaneous absence of both trust and elections. The interpretation of this solution term is not straightforward. At first sight, the fact that it identifies two simultaneous absences – no trust and no elections – seems to suggest that something has remained out of the picture: more contingent factors, such as early government dissolution or a reshuffle, or the macro-economic situation, might have an impact here. On this, of course, further research is needed. This is even more the case because this particular solution term characterizes all countries: the UK, above all, but also Spain and, to a lesser extent, Italy.

Finally, the logical minimization of the truth table gives no empirical support to my first hypothesis: at least with regard to the cases under scrutiny, the simultaneous presence of high decision-making capacity and political elections is not sufficient for a correspondence of priorities. On the contrary, it is the absence of both decision-making capacity and elections that is associated with this outcome. This solution term – which is very useful to explain both the Italian and the Spanish case – might mean that governments with low decision-making capacity (i.e. with limited agenda powers, and which are set up by several parties with different ideological stances) are not able to pay attention to citizens’ priorities in election years for two main reasons: in the semester before elections – because parties belonging to the coalition ruling the country have the highest incentives to differentiate their political claims in order to be rewarded at the polls, and this may lead legislative activity to stalemate – and in the semester after elections, because (coalition) governments with low decision-making capacity that form in highly consensual institutional settings generally need much more time to take office (Golder Reference Golder2010), and this reduces the time at the disposal of the newly formed cabinets to legislate (in accordance with public opinion priorities).

Overall, the consistency value of the intermediate solution is rather good (0.84), and the coverage of the solution formula is substantial (0.75). However, as Figure 2 shows, there is an empirically contradictory case: the case of Spain in the second semester of 2006 is characterized by a value of 0.57 with regard to the final solution formula – meaning it is ‘more in than out’ of the set of ‘semesters in which policymakers are expected to pay attention to citizens’ priorities’ – and by a value of 0.28 with respect to the outcome – meaning that it is ‘more out than in’ of the set in which it should have been included. This contradictory case thus merits further in-depth analysis in order to be correctly explained.

Figure 2 Final XY Plot

However, nine cases – being above the diagonal in the upper-right corner – are explained by any (i.e. one or more) of the four equifinal solution terms: in other words, following Carsten Q. Schneider and Ingo Rohlfing’s (Reference Schneider and Rohlfing2013: 585) terminology, they are ‘typical cases’. Moreover, 14 further cases can be considered to represent good instances of any of the four solution terms and of the outcome; in fact, even though they are below the diagonal, they are still in the upper-right quadrant. Finally, while the 23 cases in the lower-left quadrant – not being good examples of either the solution terms, nor of the outcome – do not merit particular attention, the five ‘deviant cases for coverage’ in the upper-left quadrant (Ita2006b; Ita2010b; Spa2011b; UK2010a; UK2012a) are much more interesting: indeed, their positions indicate that they are not explained in my analysis. In other words, according to the analytical framework, they represent semesters in which policymakers should not pay attention to citizens’ priorities, but they do. Interestingly, three of those same five deviant cases for coverage are election years (Italy in 2006, Spain in 2011 and the UK in 2010); this probably means that the relationship between elections and a correspondence of priorities should be better conceptualized in further research.

Concluding remarks and future research

The results shown in this article may contribute to the literature on the correspondence between public opinion priorities and government legislation in many respects. First of all, traditional studies on this topic suffer from a blind spot: they have very often focused on politico-institutional factors, while other contingent factors generally remained in the background. With regard to this, traditional theories should probably be refined and broadened, with the aim of taking into account a higher number of potential causal conditions, among which, for example, is the level of citizens’ trust in government.

Second, so far, empirical analysis of the correspondence of priorities has been conducted following two methodological approaches only: on the one hand, qualitative case studies (Chaqués Bonafont and Palau Reference Chaqués Bonafont and Palau2011; John et al. Reference John, Bertelli, Jennings and Beavan2013; Lindeboom Reference Lindeboom2012) and small-n comparative analyses (Mortensen et al. Reference Mortensen, Green-Pedersen, Breeman, Chaqués Bonafont, Jennings, John, Palau and Timmermans2011) have contributed to our knowledge of a few countries by offering mainly descriptive findings; on the other hand, scholars have employed multivariate regression, yet their analyses are mainly focused on party manifestos rather than on government legislation (Klüver and Spoon Reference Klüver and Spoon2016; Spoon and Klüver Reference Spoon and Klüver2014).

A methodological approach that is unused within the majority of this literature is QCA. However, it seems that QCA is gaining momentum in the social sciences (Rihoux et al. Reference Rihoux, Alamos-Concha, Bol, Marx and Rezsöhazy2013): indeed, more and more scholars have recently started to refer to set theory and configurational analysis in order to unravel complex causal relationships. This article has followed the same path, and here lies one of its main added values: in a world where social phenomena are generally collinear and clustered, with statistics rejecting multi-collinearity (Bartholomew and Knott Reference Bartholomew and Knott1999), QCA – by contrast – considers equifinality and, above all, conjunctural causation as big positives.

Further, in statistical analysis, cases disappear behind coefficients and p-values: we do not immediately know which cases confirm the theory and which cases contradict it. Of course, it may appear to be a minor challenge in large-N studies; yet, even in analysing large-N cases, QCA still takes into account each and every case: in all moments of the empirical analysis, one is perfectly aware that, for example, theoretical arguments hold for some cases and not for others; this, in turn, allows for a potential refinement of those same theoretical arguments.

This leads to a likely direction for future research. As previously noted, Spain in the second semester of 2006 is an empirically contradictory case in my analysis; this means that theory is openly refuted in this case. Therefore, an in-depth analysis of the peculiarities characterizing this case could be very useful in refining and broadening theoretical arguments. Similarly, the five cases lying in the upper-left quadrant in Figure 2 (i.e. Ita2006b; Ita2010b; Spa2011b; UK2010a; UK2012a) could also help in refining the theory; in these cases, while the theoretical arguments are not contradicted, the theory nevertheless proves to be insufficient to explain the outcome. Again, a closer analysis of the context of those particular cases could enrich our understanding of the phenomenon under scrutiny.

In conclusion, this article represents a preliminary analysis of how and why policymakers in Italy, Spain and the UK do (or do not) pay attention to citizens’ priorities. The results that have been obtained are not insignificant: the combination of government decision-making capacity, citizens’ trust in government and the timing of elections seems to matter for a correspondence of priorities. Furthermore, each causal condition plays a different role according to either the presence or the absence of other causal conditions. It would not have been possible to detect this latter finding, in particular, with statistical analysis. This demonstrates very well why QCA is gaining momentum in the social sciences.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.28