Personal Take VI – Richard Taylor Enjoy the Ride

My band – Everything for Some – wasn’t particularly good! In fact, we probably hold the record for the most number of gigs played to the least amount of people. Post-show overpriced service station pasties on the road at 3 am seemed to cost more than we ever got paid. Our music ‘career’ as a band was funded by numerous terrible minimum-wage temporary jobs. Once we split, I then got into independent promoting. On more occasions than I can remember, after preshow sleepless nights, I would inevitably be heading to the cash machine to cover the show loss and the remaining costs. Unless incredibly lucky (or compromising your passion), I don’t believe there is any other industry where you would put more work in to get so little out financially. However, I still look back at those days as some of the best in my life. Music is incredible, and music is shit!

To recall a 24 hours on tour, I remember travelling to Newcastle on a tour bus, drinking on the way and blasting out music with friends. Then followed a soundcheck, backstage shenanigans and an awesome gig in front of some actual people, followed by cocaine, pills, drinks and an after-show party and then back on the bus to the next city, absolutely loving life. Five hours later, after finally getting an hour of sleep and doing the cocaine luge in the bus bunk, I awoke to no serotonin left in my body, a horrendous stink from fifteen blokes in a bus, a lost bank card, the realisation we had left merch at the venue, my mouth chewed to bits and a general overall feeling of questioning my life choices.

This rollercoaster of emotions over a 24-hour period, for me, epitomises life in the music business and the mindset you need to be able to enjoy your passion. The highs are as high as you can get: to play a killer show, promote a band you love and feel part of that creative process, manage an artist you love to a level of success, and the friendships you make with likeminded people are, I believe, as good a feeling as you can get. The competitiveness, financial requirements, sense of injustice, pressure and worry and the lack of security in what you do can be very testing. If I can give one piece of advice to anyone beginning their journey, if you have the ability to sack off the negative shit and are comfortable in taking things as they come, then just enjoy the ride.

You never know where music will take you, the lows will be lows, but the highs, when they come, will be higher. The music industry beats a lot of people down, but you can experience more in a short space of time than most would in a lifetime.

I’m currently writing this at the tail end of 2020. At the beginning of this year, I was moving forward with some considerable investment for my live music promotional and software company. This very soon evaporated with the news and spread of Covid-19, alongside the possibility of making any revenue this year (and as I write for the foreseeable future). It would be difficult to think of a more damaging period for the live music industry. However, the friendships and relationships I have made throughout my time being involved in music have provided new opportunities from the crisis, and new projects I’m now working on in the recorded sector are beginning to build momentum. I cannot emphasise enough the importance of networking and building relationships in the music business. This is one industry where things can happen quickly, and there will always be opportunities if you keep moving forward.

Positive Mental Attitude is everything.

Richard Taylor, founder and CEO of MusicPlanet Live

For 23 hours, the red-white ferry will be at the mercy of dark, or even diabolical, forces! Heavy metal energises the darkest time of the year – and the floating stage will give you both an excellent sound and the chance to relax: after all, this is not a music festival with tents and beer fences, but a cruise ferry with everything from a spa and sauna to exquisite food.1

The tropical cruise was once the quintessential getaway of the elderly retiree – a relaxing voyage through sun-soaked climes augmented by the soothing sounds of the open ocean. Not any more. Come Sunday evening, the vast expanse of the Caribbean Sea will echo to the altogether more riotous noise of ‘Shiprocked’, a heavy metal festival aboard the giant Norwegian Pearl cruise ship. Setting sail from the port of Miami, Florida, the floating concert will alight in Great Stirrup Cay in the Bahamas five days later. Pina coladas by the pool and tranquil ocean sunsets from the cabin balcony this raucous event is not … According to ‘Shiprocked’ owner Alan Koenig the event will be ‘the ultimate hard rock festival at sea’.2

Consider what these pieces of marketing and reporting tell us about metal and its place in today’s global society. Viking Line (who published the first quote), a great name for a tourist corporation operating in northern Europe, is trying to get metal fans on board a metal holiday cruise with them. They target metal fans with a reference to ‘diabolical forces’ that will endanger the cruiser ferry. But they know that the marketing will work because metal and metal holiday cruises are an acceptable part of the tourism and leisure industry. The report from the CNN website (the second quote) is an older piece that is making fun of the idea that metal fans – headbangers who drink beer – would ever be found on a cruise ship sipping cocktails and soaking up the sun. As the reporter tells us, cruises typically have attracted older people, wealthy retirees spending their pension money.3 Now, of course, an entirely new cohort of music fans have been attracted to festivals taking place on cruise ships, not metal and rock fans but fans of every possible subgenre, who want the fun of a festival with the pleasure of sailing around in circles for a few days.4

In this chapter, metal as a space for leisure and tourism will be explored. I will first discuss how metal is leisure, for musicians and for fans, by exploring the meaning and purpose of leisure and leisure’s relation to modern society. I will look at how metal is a part of the wider entertainment industry, and how that industry is best defined as commodified popular culture. Finally, I will discuss three specific forms of tourism and leisure industries that align with metal: tours, festivals, and the recent growth of metal holiday cruises.

Leisure and Metal

First, what do we mean by leisure spaces and leisure activities? Both are taken to be things we do in our free time, of our own free will, when we are not compelled to be in other spaces and doing other activities that are forced upon us.5 That is, leisure activities are things that are not work activities: work, then, is the thing we have to do in workspaces. When we were hunter-gatherers, we worked to hunt and gather food. But we also worked to construct weapons, prepare and cook food, and look after our children. Our leisure was the free time we had (if we had any at all) to tell each other stories, sing and play music, or draw on the walls of our cave.6 Of course, the reality of any culture is that work and leisure activities and spaces can be and are blurred. The hunter-gatherers in our past almost certainly chatted to each other when they were out finding food. And at night, the chores of work and the activities of free leisure often merged. But the idea that leisure is the thing we do when we are fed up with the work that pays our bills is still meaningful today. Being a metal fan is a leisure choice.7 We put on a record or watch a video, and we are hooked, and this becomes our leisure identity as metal music and metal culture enrich our free time. Being a metal musician is also a free choice: metal musicians feel the urge to be creative because this is the music they love and feel gives them meaning and purpose.

In the preceding paragraph, we jumped back in time to a period before historical records began, then came right back to this century. It is necessary to do some more historical reflection, as it allows us to make sense of how leisure today has become constrained.8 In the Classical Age, the time of the Greeks and the Romans, work was something done by the lower classes, women and slaves. In Greece, elite men like the philosopher Plato spent their leisure time doing physical activity, writing and speaking to their fellows, and playing music. They nurtured an ideal of a leisured life but on the blood and sweat of the toil of others. In Rome, this ideal of what elite men did was adopted, but the Romans had a society in which significant numbers of lower-class men were free and had some influence in politics. That meant elite Romans had to create entertainment for the lower classes: chariot-racing, gladiatorial combat and other spectacles in the theatres. These were the first examples we have of what became the sports and entertainment of the wider leisure industry.

Fast-forward to the start of the modern age, the period known by historians as modernity. In the nineteenth century, the United Kingdom became one of the most powerful of the imperial powers of Western Europe, but the rest of the West was outcompeting the rest of the world as well. This was because the West had new technologies such as steam engines and the new sciences of physics and chemistry that underpinned the Industrial Revolution.9 The West had capitalism, liberalism and had seen a shift from rural to urban economies. For the rulers of the British Empire, the lessons of Classical Age were close to their hearts: they all learned Latin and Greek in the British public schools such as Eton. They believed in the Greek ideal of the healthy body and the healthy mind. They also saw the importance of bread and circuses: keeping the lower classes from rioting and rising up by giving them things to consume and things to distract them. It was no surprise, then, that in the second half of the nineteenth century, modern sports such as athletics and football emerged.10 For elite men taking part in these sports, playing the game taught them to serve the Empire. But many of these sports quickly became entertainment, with paying spectators becoming hardcore fans in football clubs around the world wherever British imperial or commercial interests spread.11

Western society, at this point in time, became a site where technology and urbanisation and the interests of elites constructed the form of consumer capitalism we see today.12 Because there were more workers who were well-off, and men and women with free time, industries emerged that targeted them: pre-prepared food and domestic appliances; restaurants; public houses; tourism facilitated by trains and steamships; and music halls.13 Some of the elites in Britain loathed these attractions and bewailed the poor leisure choices of the working classes. Drinking alcohol in pubs was seen by many as a moral danger as well as a danger to the health of British workers. But others – the owners of breweries, for instance – defended pubs as places where hard-working men could quench their thirst.

Finally, modernity was where the divide between classical music and popular music was formalised and used as a way of controlling the meaning of culture. Popular music was at first dismissed by the elites as something simple-minded for the lower classes but increasingly co-opted by governments in the West as a means of stopping the urban working classes from taking part in morally bad leisure and politically bad activism.14 From the music halls to the invention of recorded music and radio, popular music like sports such as football soon became a leisure form shaped by mass spectatorship. Popular music became a leisure space that was used as both a site of control and a site of resistance. Metal music has emerged from rock music, itself a form of popular music. Rock‘n’roll offered young people a sense of belonging, of being different from their parents and rebelling against them. Rock music in the nineteen-sixties soon offered fans a chance to be a part of an alternative counterculture. And metal, like rock, has been created as alternative leisure space that stands against the mainstream of popular music and popular culture.

Metal has been unfashionable, situated in the margins of society and its culture, and its rules have been leisure spaces that are characterised as underground. Many metal fans spend much of their free time debating genres online, collecting vinyl and seeking out the most obscure black metal. Many metal fans revel in metal’s rebel, evil, Satanic stereotypes, believing that metal is the only form of popular music that resists mainstream trends.15 Metal fans and musicians believe they have found metal through their own free leisure choices. Metal is what we might call a communicative leisure choice, something found freely and entered into through our own will.16 Metal is not the clever choice that makes a musician money, or the one entered into because one wants to be best friends with the men in Darkthrone t-shirts. Metal is not imposed on its fans and musicians by government legislation or by the government putting adverts for metal in newspapers. Metal is not sold to its fans through the round of popular music competitions on television, or through the ubiquitous social media influencers. Nonetheless, it is not wholly true to say that leisure choices made by metal fans, or the creative choices made by metal musicians, are completely free. This is because metal is part of the entertainment industry.

Metal as a Part of the Entertainment Industry

The entertainment industry is a product of modern capitalism and the successive industrial and scientific revolutions we are all still living through. The German critical theorist Theodor W. Adorno was the first person to attempt to understand its purpose, though he called it the culture industry.17 For Adorno, modern sports and popular music in the first half of the twentieth century were intertwined with the media (at the time, newspapers, radio and films) to keep the masses believing they were free when actually they were being controlled by governments and corporations. This was hegemonic power, as Antonio Gramsci identified occurring in Fascist Italy: the working classes were fed lies in the media and sold products and fantasy stories, and were fooled into thinking the Fascists were working on their behalf.18 People did not give away their freedom, they were distracted by the magician’s sleight of hand and did not even notice they lost their freedoms. There is no doubt that totalitarian states manipulated the culture industry and used it to maintain power and keep their rivals and internal enemies in check. But Adorno saw the instrumental logic of the culture industry in totalitarian states operating to a lesser degree in liberal democracies in the West, such as the United States of America and the United Kingdom. Adorno loathed all forms of culture and leisure that were commodified, bought and sold to consumers by capitalists. He hated the rise of three-minute popular music played on radio and would have hated Instagram and TikTok if he had lived in our times for their reductive, artificial, inauthentic culture.

The culture industry grew into what we now know as the entertainment industry.19 At its greatest extent, the industry covers the following forms of modern leisure and culture: music, music-making and music audiences; dance; theatre; performance arts; comedy; books; magazines and newspapers; spectator sports; television; digital leisure; social media; active recreation; drinking and eating out (hospitality); and some elements of active recreation and tourism. The entertainment industry is one where millions of people around the world work full-time as professionals, with millions more working part-time or unpaid. Many of the people who work are paid poorly, whether they are musicians struggling with streaming contracts or delivery drivers carrying fast food. The entertainment industry’s workers are generally making things that are consumed by others in their leisure time: the 12-inch pepperoni pizza is exactly the same as the black metal vinyl; it is all a product that meets someone else’s leisure needs. It is all a product that is part of a capitalist exchange that has transformed what we think of as our leisure choices.

Imagine a slightly different modern society and its popular culture. This is a thought experiment, and what follows never happened. In this alternative Earth, modernity emerges exactly like it does, and the United Kingdom is replaced by the United States of America as the political power that shapes the twentieth century. Instead of jazz, African Americans create coastarama, dance music played on North African tribal drums inflected with English sea shanties. Coastarama spreads around the world as a form of popular music and creates variant subgenres green, blue and pink. Coastarama pink is adopted as the music of the middle-class counterculture in the sixties, then coastarama pink-brown becomes a darker version of coastarama pink. This music becomes popular among young, white, working-class men in the seventies and eighties, and was subsequently sold to them by the entertainment industry. There is no doubt that if this form of popular music actually existed, music fans and musicians around the world would believe that they had found coastarama pink-brown by their own free will. They would argue about who was an authentic coastarama pink-browner, who was a sell-out, who was a fashion victim, who was evil, who was underground. Coastarama would saturate every aspect of our lives, and its variants would be the subject of books, films, websites, blogs, television programmes and podcasts. Leaders of nations would be interviewed expressing their love of coastarama pink bands. Fans would be able to buy everything coastarama, spending billions of dollars every year on coastarama pink products. Transnational corporations would invest in coastarama pink festivals, tours and bands. These corporations would own recording studios, radio stations, television stations and websites, ensuring they had an economic stake in every part of the mechanical processes of the industry. Governments would be happy that their citizens were too busy arguing the merits of coastarama green (or blue or pink or pink-brown) to notice their rights were being eroded in successive waves of rationalising legislation.

Metal, then, is completely gripped in the talons of the entertainment industry. It has its own independent labels that operate as supposedly authentic voices of an underground subculture. It has bigger labels like Nuclear Blast or Earache that operate like the big transnational corporations that control mainstream popular music. And, increasingly, those large independent labels are being controlled or taken over by the transnationals. Metal music is constructed according to the templates and restrictions of popular music, using electric instruments and using recording studios to create products to sell. Metal music is sold to fans as a form of resistance and rebellion, but the labels and managers who control the bands are just replicating the business models of the wider popular music industry.20 Metal is about albums, not singles, but that is the same as rock music, or indie music, or folk music. And metal bands rely on music that is catchy enough – or kult enough – to make some impact as musicians. Of course, the advent of illegal downloads and legal streaming means it is difficult for any bands or musicians to make enough money from metal to turn their leisure activity into a work one. Once upon a time, bands quit their jobs or left school to try to become the next Manowar or Iron Maiden. In those days, managers and labels could make huge amounts of money from the labour of their bands, but the bands themselves could live off their earnings, too. Now, though, it is almost impossible for metal musicians to become full-time professionals – they have to keep other jobs and limit the metal music-making to times when they are free. But that does not mean metal is rejecting the norms of the entertainment industry. Musicians still want their songs to be heard and still conform to those norms. Musicians make demos and send them to labels, seeking contracts. They seek out the music press, the magazines and fanzines that remain important arbiters of taste, hoping that someone in the media will endorse them. Musicians seek out managers, producers, booking agents, accountants and stylists. They use social media and the internet to reach out directly to fans, using what is currently fashionable in that virtual space to carve a metal niche that sell their music.21 Musicians or their partners become adept at sourcing and selling their merchandise: knowing who can offer cheap rates for bulk purchase of black t-shirts; finding companies that print designs; setting up as limited companies to make sure every padded envelope is tax-deductible. Bands that build up a fanbase can get bigger deals for their merchandise or may choose to license their logo and imagery to companies that have money to advertise online and in metal magazines. Finally, metal remains part of the entertainment industry in the way it has adopted the model of selling the product through playing live.

Metal Tours, Festivals and Holiday Cruises

For metal fans, there is nothing more authentic than listening to their favourite bands live. The live performance is at the heart of the relationship between musician and fan, and that relationship is based on authenticity. Metal fans want to prove to each other that they are true fans, so they attend gigs, enter the mosh-pit, raise their horns and buy the tour t-shirt. Metal fans tell each other about the bands they have seen, and they boast about seeing bands live when they talk to each other, to show how metal they are: ‘So, you saw Iron Maiden in 1985? I saw them down the pub in 1979’. Live albums and video recordings – and the infinite database that is the internet – allow fans who are unable to get to attend the gigs (or are too young, or in the wrong half of the world). Tours allow true fans to see the same band play the same set-list at different venues up and down a country. Some bands have huge, dedicated followings who meet each other when these tours happen, fans who take holidays to tour with their band. For metalheads, being a casual listener or consumer of metal is not enough. You must love the band and the music that you dedicate your holidays to and your free leisure time to: catching the bands live – or talking about tours. Watching bands play live is also important in metal because one of the founding ideologies is: metal is real music, played by real musicians. Popular and rock music has an infamous secret history of inauthenticity. In the sixties and seventies, many hit singles were constructed from the talent of session musicians, people not listed on the backs of the actual singles. Even pop singers would get a lot of help and were sometimes replaced altogether by someone who could sing perfectly. By the eighties, many popular music singles and albums were completely constructed from samples and artificial drums, guitars and pianos. Metal fans are fearful of fakery, so watching bands play live is a way of reassuring themselves that they are not being sold something artificial. Of course, metal bands are just as happy as pop artists to find ways of making recorded productions and live music as easy as possible. But they know their role in this part of the industry: they must try to perform as truly as possible, but as close to the album recordings as they can, even if that means a bit of fakery around the edges.

Bands tour because this is how the entertainment industry has evolved. Metal bands are like the rock bands of the sixties and seventies. They make albums, then they tour those albums. Early in their careers, many bands play support slots and do not make any money from the privilege of supporting an established band (sometimes support bands have to pay and lose money on the deal). Promoters want to ensure that they sell out the entire tour. Managers and accountants of the headline bands want to see better returns on merchandise in each new region the tour heads through. Before the internet allowed people to share music illegally, albums were the most important part of a band’s portfolio, and tours were viewed as the way to sell albums: metal fans hooked in the eighties and nineties would buy the whole back catalogue if they could. Since the internet made music fans reluctant to buy the music they loved, the entertainment industry changed the way it made its money.22 Now, the album was a new product that the bands had to play live to their fans who would not buy the album – but they would go to see their favourite metal bands play live. Touring, then, became the way already successful bands made money for themselves and their labels and managers and shareholders.23 Touring is still a lucrative route for metal bands, as metal fans are still happy to buy tickets to see their favourite bands, to buy the merchandise and even the new album on shiny new vinyl. Touring, however, has become harder, as bands and labels make less and less money, and established suppliers and venues reduce around the world. For many metal bands who are not signed to a big or at least respected label, or who have just established their own label, there is still the problem that becoming a full-time professional is difficult, especially in the age of streaming.24 So these bands are unable to tour extensively, tap into new markets and create media exposure because they do not have the leisure time or space. Metal musicians working as delivery drivers and raising children cannot easily abandon those commitments to go support Mastodon around South America.

Festivals have become the main space in the entertainment industry for metal bands and metal fans to reach out and find each other. Music festivals were first established for classical music – but in the post-war period, promoters and labels saw an opportunity to use the festival model for jazz, blues and popular music.25 Festivals allow a number of bands and artists to appear one after the other in the same place. In the sixties, Woodstock demonstrated that huge numbers of popular music fans could be encouraged to pay for tickets for such events if the range of acts on the bill was sufficiently diverse. Woodstock also showed that festivals needed proper security and support facilities. In the seventies and eighties, Glastonbury and others such as Pinkpop developed the model of the modern music festival, balancing the commodification of the event (the food stalls, the toilets, the fields for tents, the big fences, the showers, the marketplaces) with the desire of the fans to catch the acts they loved.26 Metal music, as it matured, developed its own dedicated music festivals, or became dominant in pre-existing music festivals. Wacken is probably the most famous metal music festival, though there are now metal music festivals in every part of the world. Metal festivals now have multiple stages, so fans can drift from one performance to the other. Some stages may be dedicated to extreme metal or to unsigned or local bands. Metal festivals offer VIP camping or hotel packages. They offer signing tents, beer tents and stalls selling everything a metalhead might need: burgers, chips, albums, tattoos, piercings, t-shirts. Again, metal festivals are exactly like any other modern music festival. They are sold as events, spaces to get away and get stoned, to live a liminal experience, like a pilgrim. But these liminal spaces are part of the entertainment industry and have been ever since free festivals and mass invasions of paying festivals disappeared. Instead of peace and love, there are things to buy, purchased from the businesses and corporations making huge amounts of money. Even where festivals are run by people with progressive politics, or for charity, the entertainment industry is never far away, making a profit from running ticket sales or catering or security.27

Metal festivals allow metal bands to play in front of fans without the need for extensive touring. Headliners can make more money from festivals than from playing multiple arenas, as festival owners know fans of the headline bands will always pay for a festival ticket even if they do not watch any band other than the one of which they are a fan. Multiple nights allow multiple headlines, so more tickets can be sold at a higher price. For bands halfway down the bill, there is not so much money as the headliners, but the fees are enough to make these bands happy and reluctant to lose money touring more extensively. Again, a carefully cultivated line-up means more dedicated fans are buying tickets just to see a band that may never come to this country again. For the bands at the bottom of the bill, there is often only the offer of a free pitch for their tents, or even a demand for money – these bands are living the dream, and festivals know there are other bands keen to share the bill if and when these bands give up.

Festivals invite fans to meet other fans and listen to their favourite bands in idyllic fields.28 They offer fans the idea of living in a tent by a stream, or a hedgerow, or a tree, watching the sun rise. Of course, real festivals are horrible spaces, filled with other people’s rubbish and excrement. Rain and wind make many festivals a nightmare of slipping knee-deep in mud and flash floods. It is no surprise, then, that some promoters developed the idea of music cruises. The cruise industry had grown at the end of the twentieth century as more and more middle-class people in the West retired early with comfortable pensions. Cruise holidays allowed these people to imagine they were authentic travellers, visiting islands in the Caribbean and the Mediterranean, but having the luxury of the all-inclusive hotel in a beach-side resort.29 Cruises also became a way for these people to travel to places beyond the seaside resorts, to Norway or the Baltics. Cruises allowed these people to claim a higher status than the working classes who flocked to the beach resorts in Spain and Mexico. Then some of the people who normally went to those resorts all started going on cruises as well, and the cruise industry expanded even more. This meant music fans, musicians and promoters were already going on cruises and enjoying the buffets and the bars and the spas. Meanwhile, the cruise industry itself was looking at ways to maximise its profits and the return on its capital investments: the enormous cruise liners packed with fun and luxury plumbing. The worsening economic climate in the second decade of this century and the fall in the number of people with secure pension schemes meant that the industry had to find new customers.

It was not long before the first music cruises emerged as small events using spare cruise liners.30 Metal promoters followed their rock and prog equivalents and realised cruises were a perfect, safe environment for festival-style events. Cruise-liner owners saw metal fans as being well-behaved, high-spending consumers who could become future cruise-liner regulars. Onboard ship, the fans can mix with the bands, but the bands can also get luxury cabins. Onboard ship, fans can drink all day, eat all day, soak up the sun and mosh on a floor that is not a swamp. For the bands, the same benefits and problems occur on a cruise liner as they do at a festival. But at least the problems of being low on the bill on a cruise liner is you get to be on holiday in a sunny part of the world for a few days – and you might get the chance to make new fans and sell them your new merch.

Conclusion

Metal is inextricably part of the entertainment industry. No metal fan or musician has come to metal of their own free choice. All forms of popular culture are inherited by the people who live in them. But metal still gives meaning to people’s leisure lives and allows musicians to make the music they love, and for fans to be moved by that music. All leisure is constrained, but metal is less constrained than mainstream pop music, say, because it remains unfashionable to critics and uncool to trendsetters. Metal, therefore, provides a communicative leisure space in which fans and musicians can find meaning, belonging and solidarity. Musicians make the music because it gives them satisfaction and status in metal culture, and many do it in their free time alongside other things that pay their bills. Until metal becomes trendy, it retains some potential as a leisure form that resists conformity, commercialisation and control. Metal’s uncompromising riffs and unfashionable themes still make it more likely to be a space for resistance rather than a way for the entertainment industry to maximise profits.

Vignette 1: Israeli metal band Orphaned Land headlines this evening as the fourth band, and the audience seems relaxed and excited at the same time. As the song ‘All is One’ begins with a toned-down iteration of the main riff, the band’s singer, Kobi Farhi, claps along with the

![]() -time signature, emphasising the riff’s 3+2+2 accent structure as heard on the studio version of the song. He animates the audience to join in, which works surprisingly well considering the unusual rhythm. As the song continues – while maintaining the rhythmic structure throughout various formal sections – people engage bodily with the music in different ways. The bass player, for example, seems to be the most avid headbanger of the band, throwing his head up and down in a slightly tilted manner in strict synchronisation with the riff’s 3+2+2 structure. Meanwhile, Kobi Farhi, besides moving about on stage, performs his most expressive movements with his hands and, in part, with his shoulders. These include intricate hand gestures with minute finger actions, flowing movements and circular motions that extend to the shoulders. There is also a variety of movements among audience members, although the majority stands rather still. A few people continue clapping, others also headbang in synchronisation with the riff accents, but not as clearly as the bassist. Instead, heads are visible that are pointedly thrusting downwards on each downbeat, moving rather fluidly through the rest of the bar. Yet other audience members calmly sway from side to side, the shoulder leading the movement while slightly twisting the upper body according to the swaying direction.

-time signature, emphasising the riff’s 3+2+2 accent structure as heard on the studio version of the song. He animates the audience to join in, which works surprisingly well considering the unusual rhythm. As the song continues – while maintaining the rhythmic structure throughout various formal sections – people engage bodily with the music in different ways. The bass player, for example, seems to be the most avid headbanger of the band, throwing his head up and down in a slightly tilted manner in strict synchronisation with the riff’s 3+2+2 structure. Meanwhile, Kobi Farhi, besides moving about on stage, performs his most expressive movements with his hands and, in part, with his shoulders. These include intricate hand gestures with minute finger actions, flowing movements and circular motions that extend to the shoulders. There is also a variety of movements among audience members, although the majority stands rather still. A few people continue clapping, others also headbang in synchronisation with the riff accents, but not as clearly as the bassist. Instead, heads are visible that are pointedly thrusting downwards on each downbeat, moving rather fluidly through the rest of the bar. Yet other audience members calmly sway from side to side, the shoulder leading the movement while slightly twisting the upper body according to the swaying direction.

Vignette 2: During Orphaned Land’s rendition of ‘Sapari’ in Vancouver, the band is joined by belly dancer, artist and musician Mahafsoun, who contributes a dance performance throughout the entire song. She positions herself in the centre of the stage, her left leg slightly bent and her arms raised above her head. Together with the singer, she animates the audience to clap along to the intro vocals that are heard via playback. As the entire band begins to play, she starts moving her arms in a circular motion, performing intricate gestures, and she accents the musical hits with jolts of her hips and a forward-directed motion of her left leg. This complex interplay between her movements and the music – including synchronicity, ornaments and more – also incorporates a headbanging motion during a number of pronounced musical accents played in unison by the band. These are embodied by Mahafsoun as she thrusts her head from one side to the other in synchronisation with the accents. After headbanging, her movement focus shifts back to her hips, with which she continues to emphasise and embellish the musical beat.

As these introductory examples illustrate, people move their bodies to metal music and interact with it – they dance. Audience members and performers on stage do so in various ways, some of which have become iconic practices of metal, such as headbanging, and others that seem rather uncommon and are not as closely associated with metal at first glance, such as belly dancing. A dance practice that is not mentioned in the vignettes, but which has attracted considerable public and arguably the most academic attention of all metal dances, is moshing. The next section therefore investigates the social organisation of mosh pits and discusses them as contested communities because they offer communal experiences while simultaneously perpetuating existent obstacles to participation, especially in relation to gender identities. Revisiting the introductory vignettes, the final section’s outlook points out blind spots in research to highlight the need and possibilities for further research. This especially pertains to an extended scope of dance-related phenomena so as to account for practices beyond headbanging and moshing in extreme metal. Such an extended focus would additionally include perspectives on digital dance spaces, the global distribution of dance practices, histories of metal dance and further studies on the aesthetic relations of music and movement in metal. In this way, this chapter aims to provide an introductory overview of dance practices in metal, their social organisation and avenues for future research.

Contested Mosh Pit Communities

Moshing is one of metal culture’s most common forms of movement. There is no single practice to which this term refers, as the terminology varies across metal scenes and cultures. In this chapter, moshing is understood as a conglomerate of different movement practices that are mostly, though not exclusively, performed at metal concerts, such as pushing, jumping, running or clashing into each other and more.2 All these movements take place in the mosh pit (or just ‘pit’ for short), which is a performative, often circular, space that emerges in the audience, usually close to the stage. Depending on the size of the audience, there can be several mosh pits at an event, which are dynamic in that they can merge into a larger one, just as one large pit can separate into several smaller ones. Further practices that often involve the pit are ‘stage diving’ and ‘walls of death’. In case of the latter, the pit opens up, and participants split into two halves that face each other. Following a musical and/or verbal cue by the band, the two walls run towards each other and clash into each other, often leading to further moshing. If audience members manage to get onto the stage, they jump off the stage’s edge and dive into the audience below, which usually awaits them with outstretched arms, ready to catch them. Being caught by the audience opens up the possibility of crowd surfing, i.e., instead of dropping the stage diver, the audience continues carrying them and passes them on through the audience area, thereby surfing over the crowd.

Considering that pushing, running, jumping and clashing constitute a pit, moshing at first glance might make the impression to be nothing but violent chaos that happens to take place while music is playing. There is some truth to that in so far as participants might sustain injuries, and the numerous, fast-paced activities in a pit can be disorienting. Yet, research into the social workings of moshing has shown that it is more complex than that.

Mosh Pits as Communal Spaces

Moshing is indeed a regulated practice that enables experiences of communal bonding and individual identity work. The most overt means of regulating moshing is the so-called ‘pit etiquette’, which consists of a rather loose collection of guidelines for how to act in a mosh pit. The etiquette’s specifics can vary in detail because it is part of metal’s informal cultural knowledge, which can change across times, locations, scenes and situations.3 Nevertheless, as pit etiquettes generally aim to prevent an escalation of violence and prompt moshers to be mindful of each other despite their transgressive interactions, there are basic elements that most, if not all, pit etiquettes share. These include, for example, limiting moshing to the pit so as not to involve those who do not want to participate, or the imperative to pick up moshers who have fallen down to prevent them from getting trampled and stepped on accidentally. The pit etiquette illustrates that while moshing involves violent practices, this violence is not uncontrolled. Although it might seem contradictory from an etic perspective, moshing’s violent character supports bonding among moshers.

Early research on moshing from the 1990s already noted this complex interplay. Harris M. Berger, investigating mosh pits at US-American death metal shows, pointed out that there is a continuous and dynamic tension between violence and order.4 Moshing not only enacts but also represents violence, according to Berger, and when the enactment steps into the background, the representation and portrayal of violence can bring camaraderie and friendship to the fore. In examining and comparing UK metal, punk and ska subcultures, dance scholar Sherril Dodds observes a similarly ambivalent role that violence plays for metal’s dance practices in fostering communal bonds among dancers.5 In another early ethnographic study, Katharina Inhetveen analyses movements and violence at hardcore concerts in Germany.6 Although hardcore’s and metal’s dance practices are not always identical, they do share similar movements that involve violence, and they have historical points of contact.7 Regarding the movements’ violence, Inhetveen also stresses the existence of rules of moshing and identifies three different forms of violence at hardcore concerts: negative (i.e., intentionally harmful), necessary (i.e., sanctioning) and positive violence. Instead of aiming to dominate others, the latter tends towards symmetrical interactions of the participants and is rather supposed to guarantee that everyone involved has a good time.8 Inhetveen calls this rather playful violence ‘sociable violence’ (Gesellige Gewalt).9 In order to accommodate this positive and socially productive violence that is at odds with everyday life’s conventions of bodily interactions, mosh pits have been conceptualised as ‘liminal spaces’.10 As such, they suspend rules to a certain degree that govern everyday life and temporarily replace them with other rules specific to that space, such as pit etiquette.

According to Gabrielle Riches, these liminal spaces tend to form in backspaces, as these offer participants relatively little official surveillance, the possibility to indulge in practices that may otherwise be off-limits, and a sense that these practices are generally sanctioned by other people in that space.11 Collectively producing mosh pits as liminal spaces within shared backspaces further contributes to moshing’s capacity to provide communal experiences for those involved. While engaging in these spaces, dancers must strive to maintain a balance between suspending everyday life’s rules of bodily comportment and not transgressing metal’s own moshing conventions. Doing so is a continuous and dynamic joint effort with its own contingencies, and therefore the participants need to be able to rely on each other, which requires and, in turn, builds trust among them.12 This illustrates that moshing’s intense and sometimes violent corporeality furthermore entails and is inseparable from its affective charge. Affective intensities are crucial to the experience of moshing and have been largely neglected in earlier research in favour of a focus on mosh pits as representational means of bonding.13 Rosemary Overell, in her study of Australian and Japanese grindcore scenes, pursues the foundational and extensive role affect plays for moshing’s ability to connect and collectivise people. When moshing, among other moments, ‘scene members feel a collective sense of belonging with other fans at the event. The self, as bordered, individualised subject, is effaced via the affective intensity of the gig’.14

Taking the complexity of moshing as social interaction into account, it is moshing’s ambivalent inclusion of violence, its liminal status and its bodily as well as affective intensity that enable the dancers’ bonding experiences. Viewed from these interlaced perspectives, mosh pits are embodied manifestations of metal communality.15

Mosh Pits as Contested Spaces

Although the communal aspect of moshing is repeatedly emphasised by many dancers and theorised by researchers, moshing is not an all-inclusive space, and there remain obstacles to equal participation in the communal experience it can offer. Most notably, this pertains to moshing as a gendered practice. Most research on moshing’s gender politics begins with the observation that far more men than women engage in moshing, thereby construing it as a male-connoted practice. For example, while Jonathan Gruzelier estimates that 70–75 per cent of moshers are male, Leigh Krenske and Jim McKay even observe a rate of 95 per cent or more male pit participation.16 Whatever the precise number, which is sure to vary over time, place and event, the quantitative dominance of men in the pit and their intimate interactions – including clashing, sweaty bodies – have prompted the theorisation of mosh pits as homosocial spaces.17 As such, the image of mosh pits as inclusive spaces that are open and welcoming to everyone is differentiated by the fact that they primarily foster male bonding. Crucially, Gabrielle Riches’ nuanced analyses of gendered pit experiences stress the existence and interaction of multiple instead of one monolithic masculinity within mosh pits.18 By engaging with these competing masculinities, she is able to show that not all masculinities are unreservedly welcome in the pit, further shattering the notion of an all-inclusive space, and demonstrating that mosh pits serve as spaces for the negotiation of metal masculinities. In her research on Canadian pits, Riches proposes what she calls ‘marginal metal masculinities’ as those that do not have access to traditional sites of discursive power and are therefore opposed to mainstream or hegemonic forms of masculinity. These marginalised masculinities were valorised in the pit, which is why it was experienced as inclusive by the men concerned. In order to maintain this sense of inclusivity, however,

performances of a traditional hegemonic masculinity were negated in that men who used moshpits to demonstrate feats of strength, to size up other men or who intended to display their dominance over other men were considered unwanted outsiders, or what the participants referred to as ‘meatheads’. These men embodied a hegemonic masculinity, which was understood as antithetical to heavy metal masculinity.19

As these so-called ‘meatheads’ exhibited what Inhetveen calls negative violence, it was legitimate for other moshers to engage in necessary violence so as to drive out the meatheads and ensure the maintenance of positive violence.

Although the predominance of men is especially striking at first glance, it is important to note that women also throw themselves into pits and engage in the transgressive whirlwind that is moshing. Riches and colleagues show that by doing so, female moshers can also inscribe themselves into this temporal metal community corporeally and experience themselves as part of a larger scene, in this specific case, the Leeds (UK) extreme metal scene.20 What mosh pits also potentially offer women is to defy traditional gender roles and expectations by rejecting conventionally female-connotated forms of leisure and instead participating in moshing’s violence.21 This participation empowers them as committed subcultural members and heightens their visibility as such, especially in practices such as stage diving.22

Moshing women not only transgress norms of everyday bodily interaction but simultaneously also the metal mosh pit as a male homosocial space. Male moshers’ ambivalent reactions, in turn, highlight the pit as a contested arena, as interactions range from continued moshing through especially protective behaviour – so as not to harm the women who supposedly cannot compete in a ‘regular’ pit – to women simply being forced out of the pit or to its margins by men in order to restore homosocial stability.23 These attempts are not always successful because female moshers do not simply accept but defy their exclusion by re-entering the pit and claiming participation.24 Yet, pit ejection is not the only way the moshing experiences of female moshers are undermined by men. As Riches and colleagues go on to explain, pit participation is fraught with risks for female moshers because they are potentially subject to sexual abuse due to the anonymity granted by the blurring disorientation in pits, especially during stage diving and crowd surfing.25

While conceptions of mosh pits as contested homosocial spaces already touch on aspects of sexuality, and Riches even suggests a (homo-)erotic perspective on pits,26 the role moshing plays for queer metal fans has not received much academic attention so far. Yet, Amber Clifford-Napoleone’s study on queer metal provides an account of how queer metalheads consume moshing.27 About one-fifth of her survey participants claim to focus on moshing at metal concerts, and those who actually participate in the pit point out the contribution of moshing to their metal identity and sense of being part of a metal community, similar to the experiences described above. For those queer metal fans that focus on moshing without physically participating in it, mosh pits offer a spectacle that allows for queer desire because ‘disorganized movements of sweaty, out-of-control bodies slamming into each other provides a way to consume bodies in physical action without being policed as a queer person in a heteronormative space’.28

As the various perspectives on moshing’s gender dynamics highlight, mosh pits are ambivalent spaces and not simply sites of an all-encompassing metal community. They offer communality, empowerment, good times and much more to metal fans, and therefore they occupy a central place in the lives of many metalheads. Yet, mosh pits simultaneously present themselves as contested and, at times, fragile social spaces where different masculinities compete; female moshers face additional physical risks and obstacles when claiming their place in the pit; and queer fans covertly navigate the mosh pit’s heteronormative terrain. In doing so, mosh pits and their conditional inclusivity mirror a gap between metal’s proclaimed inclusivity and its remaining mechanisms of exclusion that have been observed in metal culture more widely.29 While this chapter has addressed and illustrated moshing’s conditional inclusivity in terms of gender, further aspects of identity and difference could and should be pursued, such as exclusions due to race or ability. These identities are likely to face similar challenges concerning pit participation as those relating to gender, although research on these issues is scarce in the realm of mosh pits.

Outlook and Avenues for Future Research

Research into metal’s dance practices spans more than twenty years and provides numerous insights and sophisticated analyses, all of which further the understanding of these corporeal activities. Nevertheless, there are common foci that have established specific representations of dance and the resulting blind spots. The remainder of this chapter points beyond these representations and highlights desiderata for future research as well as first steps that have already been taken towards addressing them.

Beyond Headbanging and Moshing in Extreme Metal

When considering the majority of the literature cited so far in this chapter, one might be tempted to equate dance in metal with moshing practices and headbanging at live concerts of extreme metal bands, primarily in the Global North. As the introductory vignettes hopefully illustrate, there are more movements, cultural interactions and spaces involved in metal dance than that. Since headbanging and moshing are so prominently associated with metal, other forms of movement are easily overlooked. The intricate gestures and movements of Orphaned Land’s singer or the performance of a belly dancer are striking examples and by no means the only ones. During my ongoing research on metal dance, I encountered numerous forms of movement: spontaneous circle dances during the performance of folk metal band Korpiklaani; humorous conga lines initiated and choreographed by the musicians of Trollfest; or the collective swaying of smartphones during metal ballads, to name but a few. Metal’s movement repertoire is more complex than its depiction in research. Besides the prominence of headbanging and moshing, this is probably connected to the fact that the focus is mostly on extreme metal, which tends to be conceptualised as locally self-contained subcultures or scenes. The implicit depiction of moshing and headbanging as (extreme) metal’s only dance forms reinforces such a conception and, in effect, contributes to an essentialist notion of ‘what metal is’. By broadening the scope beyond extreme metal and viewing metal’s subgenres as porous formations that interact with other music cultures, different movements come into view. Such a perspective can also better account for the movement variety, as some fans literally move through different movement cultures – physically and via media – potentially disseminating and modifying dance practices along the way. Thereby, for example, belly dancing is combined with headbanging at metal concerts, and hip hop and electronic dance music cultures have adopted mosh pits as they see fit.

Digital and Global Dances

Another blind spot concerns the spaces where dancing in metal takes place. Due to dancing’s embodied, interactive nature, facilitated by the loud music, the numerous potential fellow dancers and further social conditions, live concerts are the main dancing events in metal. Research has attended to them with insightful results, as described above. Yet, dancing is not restricted to physical spaces such as live concerts but also takes place digitally. This became especially apparent when the Covid-19 pandemic forced concert venues to close down, encouraging alternative formats such as live streams of bands performing while audience members sit individually at home and simultaneously inhabit a shared digital space via platforms such as Zoom or Twitch. Although physical bodily interaction is prevented that way – precisely the aim of these formats – audience members film themselves raising their horns, banging their heads or otherwise going wild in their homes. The workings of these hybrid dance experiences have yet to be explored, and their investigation might reveal fluid body/media constellations and contribute to dismantling nature/culture dichotomies. This possibility is slightly touched upon by Paula Rowe when her interviewees, some of whom have never physically participated in a mosh pit but have watched recorded performances, describe feelings of care and community in mosh pits.30

Digital space is not the only dance environment scholars have scarcely paid attention to so far. Despite the fact that metal is heard, played and lived all over the world, metal studies have less to say about metal dance in the Global South, as significantly more of the usually ethnographic research has been conducted in the Global North, especially in English-speaking countries.31 A simple extrapolation of these findings to the Global South would reinforce a hegemonic overgeneralisation that assumes the Global North as the universal norm. In order to prevent this, it is necessary to take the situatedness of dance practices seriously and investigate how they figure into the lives and experiences of metal cultures and fans from the Global South. A similar argument motivated Eliut Rivera-Segarra and colleagues in their research on mosh pits in Puerto Rico.32 Furthermore, the global circulation of metal and its movements also begs the question of how movements are consumed and how their meanings have shifted as they have travelled the globe. When Mahafsoun performs at a concert in Vancouver, as described in vignette 2, issues surrounding exoticising gazes, for example, emerge that warrant further investigation.

Metal Dance Histories

A further aspect that is crucial to dance as a cultural practice is its historical development, and a more thorough understanding entails grasping transformations and continuities throughout situated dance histories. However, since research on these embodied performances usually relies on ethnographic approaches with valid arguments, insights into metal’s dance histories largely remain a desideratum. Two approaches that exemplify such a perspective are provided by Stephen Hudson and Wolf-Georg Zaddach. Hudson investigates headbanging with a focus on the US and argues that it can be viewed as a continuation and exaggeration of movements already present in earlier styles of African American rock and blues music, therefore positioning it as a legacy and not as an entirely new form that first arises in metal.33 Zaddach’s study of metal in the German Democratic Republic vividly depicts the potential consequences faced by moshers and the musicians, who instigated mosh pits, when confronted with a repressive governmental system.34 This could include, for example, the forced break-up of bands because they were perceived to incite riot-like behaviour.

Relating Music and Movement in Metal

The last gap in knowledge to be briefly addressed in this chapter is the relation between metal music and metal dance as aesthetic and performative practices. While side notes frequently mention the central importance of music for dance, research has barely examined their relation in detail.

Stephen Hudson develops a construction-based theory of musical metre and turns to headbanging with the aim of identifying how music can invite people to headbang.35 To this end, he investigates two of metal’s most common metering constructions by which he means ‘any conventional association between a specific way of moving, a specific syntactic function or rhythmic interpretation, and specific sounding musical features’.36 The metering constructions he turns to are backbeats and 3+3+2 phrase endings.37 Analysing these by mainly focusing on the music of Metallica, Hudson relates headbanging movements to features of sounding music, especially rhythm. In this way, he is able to position headbanging as a cultural convention among metalheads while simultaneously considering the individual freedom in feeling and interpreting musical rhythm through the body as described in vignette 1.38 In his discussion of groove in doom metal, Jonathan Piper similarly emphasises that headbanging is not just an automatic reaction to imperious music. Instead, headbangers respond variedly to musical developments, including modifications in headbanging style, and actively embody their temporal experience of the music.39

A musical feature often associated with metal dance are so-called mosh parts, a term originating from fan and journalistic discourses and adopted in musicology. Generally, mosh parts designate sections in songs that seem to particularly invite moshing. According to Dietmar Elflein’s extensive study of heavy metal’s musical language, they are characterised by a perceived reduction in tempo, in that the pulse of at least one crucial sound layer (for example, drums or rhythm guitar) is halved or slowed down even further, and have gained in prominence, especially with the development of extreme metal in the 1980s.40 Although it might seem like a paradox, it is the perceived slowing down of the music that is accompanied by heightened dance activity. Glenn Pillsbury, whose work Elflein partly draws on, lays out a similar notion of mosh parts, which he integrates into his description of cycles of (musical) energy that ‘focus power and intensity into bodily experience’.41 Varying combinations of musical elements such as distorted and palm-muted timbres, rhythmic intensities, the register and range of riffs, and variations in the perceived speed amount to different levels of energy throughout a song. These are, in turn, embodied by musicians and audience members through headbanging and moshing as well as through rigid postures and jerking movements, for example.42 By considering the contribution of sound specifics and the register and range of guitar riffs, Pillsbury broadens the musical scope beyond the crucial role of rhythm and tempo for a bodily engagement with music.

Another formal section closely related to mosh parts and moshing is breakdowns. In his multifaceted analysis of breakdowns in twenty-first century metal(core), Steven Gamble observes that this musical structure stimulates moshing in a similar way to mosh parts and actually positions mosh parts as progenitors of breakdowns in recent metal music.43 In his definition, breakdowns are characterised by a two-part pulse structure: cymbals and snare drum create a solid backbeat that establishes a regular metre. The rhythm is set against this as a second structure that consists of potentially complex patterns of kick drum hits and guitar chugs played in unison and contrasting the regularity of the metre. This relation is asymmetrical in favour of what he calls a ‘metrical hegemony’, as audience members are more likely to engage with the regular backbeat. Gamble relates this musical tension between metre and rhythm in breakdowns to tensions and negotiations between local pit communities and ‘wider society’: ‘Breakdowns invite listeners to mirror perceptual properties of the music in the listening process, acting out the tension between rhythm and metre with their own imagined contest against constraints’.44

Despite these insightful contributions to the study of music-movement relations, further research is needed. Similar to the generally narrow focus mentioned above, a broader scope would be beneficial that extends beyond the relation of music to headbanging and moshing, beyond a focus on rhythm and tempo, and beyond 1980s extreme metal (particularly Metallica), although there is already significant work that addresses the latter two aspects. Finally, in terms of methodology, an integration of different research approaches would be a reasonable next step. While ethnographic investigations into metal dance as communities tend to neglect consideration of the music, musical analyses have tended to forego ethnographic fieldwork and rely instead on audio-visual recordings of concerts. Combining participant observation and approaches to music and movement analysis promises further insights into the interactive, embodied relationship between metal music and bodies.

Conclusion

As this introductory chapter has hopefully shown, research on dance practices in metal offers differentiated analyses and a rich understanding of these interactions. In the process, it becomes transparent that uninformed devaluations of dance and its practitioners are just as untenable as sweeping praise of aspects such as inclusivity and communality, as can sometimes be found in fan discourse. Nevertheless, considerable gaps and desiderata still need to be attended to. Although these have been described separately, they are actually intertwined, as, for example, the relationship between music and movement is not isolated from, but feeds into, the communal experiences offered by moshing and other practices. These intersections are what metal studies need to engage with if they are to further a notion of dance in metal as a heterogeneous, complex and culturally situated practice.

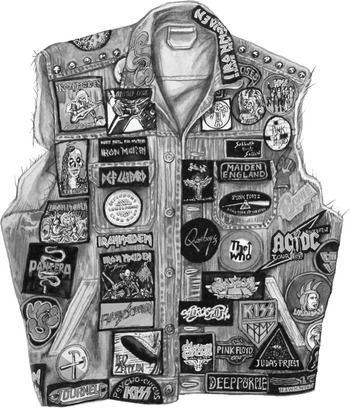

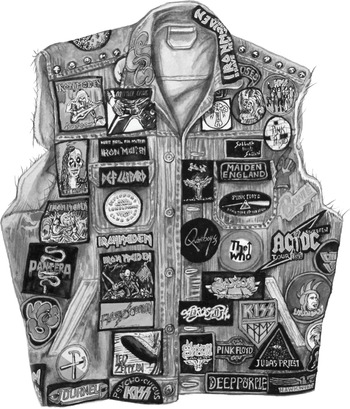

For anyone who has attended a heavy metal concert, or seen fans congregating outside one, the particular aesthetics of metal style will be familiar. Metal clothing is famously characterised by the fabrics denim and leather, to such an extent that the British band Saxon even named a song and album, Denim and Leather (1981), after this combination. The de facto uniform of the concert crowd is the band t-shirt, usually black, adorned with bold graphics and logos announcing the wearer’s band of choice. Paired with jeans and boots or trainers, the band t-shirt is the staple of most metal wardrobes. For the committed fan, the outfit is often completed by a customised ‘battle jacket’ uniquely configured to the wearer’s preference (see Figure 15.1). A battle jacket – also variously known as a battle vest, patch jacket, cut-off or Kutte – is a denim jacket, usually with the sleeves removed, decorated with patches, badges, studs, festival bands, handmade artworks and various other embellishments added by the owner to display their musical taste and allegiances.1

Figure 15.1 Tom Cardwell, Moonsorrow, 2020, watercolour painting on paper, 38 × 26 cm

Battle jackets are an important expression of metal identity for many fans and musicians and allow individuals to demonstrate commitment to metal subcultures and signify difference from mainstream styles and values. This chapter discusses the history and origins of battle jackets as a key component of metal style and considers the meanings and significance of these garments for those that make and wear them. The following argument makes reference to a series of interviews conducted by the author with jacket makers between 2014 and 2020.

Heavy Metal Style

As with the music itself, heavy metal style evolved in large part from the 1960s counterculture, as well as bringing influences from blues culture via 1950s rock ’n’ roll,2 both of which had connections with working class and manual labour, with the prevalence of denim as a workwear fabric giving rise to the term ‘blue collar’.3 Motorcycle culture also had a significant impact on the development of metal style, with the leather jackets, jeans and boots favoured by bikers becoming commonplace in rock and metal wardrobes by the 1970s.4 The historically masculinist codes of such working-class cultures, along with connections to military traditions, have caused many to view heavy metal clothing as at best nostalgic and at worst reactionary,5 with limited stylistic options available for women. Writing in 1985, Philip Bashe identified two alternatives for female metal fans when it came to clothing, either dressing like ‘the boys’ or else adopting the looks of the ‘goddesses they see in their heroes’ videos’.6 Whilst possibilities for more nuanced negotiation of gender identities through metal clothing arguably exist in today’s scenes (more on which later), these connotations ostensibly persist.

One of the key functions of heavy metal style is to mark the wearer as part of the ‘community of all metalheads’7 and to differentiate them from the perceived mainstream.8 As one fan I interviewed, Emily, put it when talking about her jacket: ‘You tend to exclude the mainstream from your insider [culture]. I call it “outsider/insider” because you’re an outsider, but you’re inside of this outsider culture’. This sense of distinction from wider culture is reinforced through the challenging and sometimes extreme nature of the images and texts that feature on metal clothing.9 The ‘insider’ or community aspect of metal fandom is expressed through individuality negotiated within the stylistic structures of the wider subcultural group. A sense of the tribal is apparent in metalhead style, for example, in the prevalence of long hair, beards, tattoos and DIY customisation of clothing.10 In these respects, the battle jacket is emblematic of many aspects of metal culture through its distinctiveness, connection to subcultural structures and traditions and personal construction.

Key Features of a Battle Jacket

Although individually customised, most battle jackets adhere to a set of tacitly agreed conventions amongst makers. The majority of jackets are based on the classic denim jacket epitomised by the ‘type III’ jacket created by Levi Strauss in the USA in the early 1960s;11 other popular garments are leather jackets, military jackets and workwear shirts. This includes a large rectangular area on the back of the jacket formed by the borders of the yoke, side panels and waistband. This area provides a prominent location to display patches or other artwork and is usually the site of a ‘backpatch’ – a large patch featuring detailed artwork and band logo, which is generally chosen to foreground a band that the wearer favours above most others. Around the backpatch, smaller patches can be displayed, often in closely-tessellated rows and columns (see Figure 15.2). The yoke area across the shoulders provides another large space but on a narrow landscape orientation, making it suited for large text-based logo patches, or a series of smaller patches. The area at the base of the back of the jacket is often populated by one or more ‘superstrip’ patches – wide horizontal patches, which usually bear a text logo appended by small artworks.12

Figure 15.2 Metal fan photographed at Bloodstock Festival, UK, August 2014.

The front of the jacket can be adorned with small patches as well as pin badges, studs and festival wristbands sewn on as strips (giving an effect similar to military rank colours) and other chosen additions (see Figure 15.3). Unlike the back of the jacket, the front does not afford any ideal spaces for bigger patches, as it is interrupted by fastenings (for example, buttons and buttonholes), collar, pockets and vertical seams. Nonetheless, some fans manage to feature large patches or artworks on the front, perhaps by changing the orientation of the patch, or cutting the patch in half and sewing half on each side of the front, so that the image is unified when the jacket is closed. Most battle jackets have the sleeves removed, allowing them to be worn over another garment (hence the popular term ‘battle vest’ used interchangeably with ‘battle jacket’), although some choose to retain them, in which case further patches can be added.

Figure 15.3 Tom Cardwell, Aidan’s Jacket (Front), 2015, watercolour painting on paper, 38 × 26 cm

Amongst jacket makers like those interviewed, there are variously acknowledged ‘rules’ about how a jacket should be composed and what type of patches these should feature. These rules are rarely universal but may be upheld as important by certain groups of makers or fans of particular genres of metal. Perhaps the most commonly held view is that a jacket should only feature patches relating to bands that the wearer has a sincere appreciation for. Some extend this to a qualification that one should own physical music (vinyl, cassettes, CDs) by the featured band, and others argue that they must have attended live concerts by each artist. Another common ‘rule’ is that a jacket should not be ‘double patched’, that is, feature only one patch by any particular band. There are many exceptions to this rule, however, notably in the genre of ‘tribute jackets’ that exclusively feature patches representing a favourite band.

Some fans maintain that a jacket should be genre-specific, featuring only patches for 1990s death metal bands or black metal bands, for example. Many jacket makers emphasise the importance of personal choice above genre conformity, however. As a maker called Pete put it:

Because this is documenting my life and my taste in music, and consequently, there’s a lot of non-metal stuff on here as well, which really f**ks people off! The ‘true metal heads’ go, ‘How can you have that next to that?!’, and I say, ‘Because I like ’em!’.

For all the credence extended to various rules by some, a common rejoinder to this attitude is expressed by Simon Springer, founder of Pull the Plug patches: ‘The overarching theme is (that) there should be no rules! It’s metal, it’s supposed to be rebellious’.13

History and Development of Battle Jackets

Whilst it is difficult to say for certain when battle jacket-making first started, it seems to have been well established by the time heavy metal music became widely popular in the 1970s.14 Methods of customisation around this time included hand embroidery, which was practised by fans as a way of rendering band logos on their jackets in the absence of readily available commercial patches.15 Once bands began to cater to the demand for patches, these became a way of commemorating particular gigs and tours, with unique editions sold at merchandise stands in concert venues. This means of distribution lent a sense of authority to the patches, as possessing a particular patch would usually indicate that the wearer had attended the concert it had been sold at. The battle jacket thus became a garment that testified to lived experience, with a heavily patched vest marking its wearer as someone who was deeply invested in the subculture.

The sense of a battle jacket as a marker of subcultural status owes much to the heritage of motorcycle jackets, and particularly the denim or leather ‘cut-offs’ worn by members of ‘outlaw’ bike clubs, which feature patches bearing logos of club affiliation and rank.16 The quasi-military order of the patches on bikers’ jackets is arguably linked to the formation of such clubs by returning veterans after World War II and the Vietnam War in America.17 Military uniforms themselves have been highly influential in heavy metal style, just as themes and imagery of war and conflict feature regularly in metal music. Some bands produce artworks and merchandise that directly reference military insignia and patches,18 and items of combat gear such as camouflaged clothing and army boots are staples of metal fans’ attire. Indeed, the term ‘battle jacket’ directly connects the garments to such traditions. During World War II, bomber crews wore leather flying jackets (most popularly the A2 type), which were often custom painted with the nose artwork from the plane they operated, as well as tally markings that enumerated missions flown or targets destroyed.19

Going back even further in history, early antecedents for metal fans’ jackets might be found in the heraldic tabards and armour worn by combatants in the Middle Ages.20 The tradition of heraldry has continued in folk costumes, such as those worn by Morris dancers, which are customised with badges, bells, coloured fabrics and small objects,21 in a parallel of the customisation of battle jackets. Like battle jackets, these costumes are worn in a performative context and play a key role in marking the wearer as part of the group and a participant in the festivities at hand.

Amongst twentieth century youth subcultures, there are many examples of customised clothing that compare directly to the jackets of heavy metal fans.22 During the 1950s in Britain, informal motorcycle subcultures such as the ‘rockers’ and ‘ton-up boys’ customised their leather jackets (often based on the famous ‘Perfecto’ style popularised by Marlon Brando in the 1953 movie The Wild One) with bike logos, club badges and ‘run patches’, which commemorated particular rides, in much the same way as metal band patches commemorated concerts.23 During the 1970s and 1980s, punks re-appropriated leather biker jackets, which were decorated with hand-painted logos and slogans, studs, chains and other additions.24 A number of post-punk subcultures, such as goths and crustpunks, also used hand-painting on leather jackets as a key mode of individuation.

Whilst battle jacket-making has remained an important part of metal subcultures since the practice was first established, there have been periods and genres of metal in which it has been particularly popular. The early 1980s was one such period when genres such as the New Wave of British Heavy Metal (NWOBHM) in the UK and thrash metal in the USA both saw an emphasis on battle jackets amongst musicians and fans. During the 1990s, battle jackets were perhaps less common, as the genres of nu metal and grunge changed the style and expression of metal fans,25 although even during this period, jacket customisation practices persisted in extreme genres such as black metal26 and death metal. After the turn of the millennium, the popularity of previous styles of metal grew once more, and battle jacket-making enjoyed a renaissance, which has continued until now.27 Today, battle jackets are very much in evidence in many metal scenes, with a large online community that post images of jackets and trade patches.28 Part of the present popularity may be driven by the nostalgic interest of veteran fans, who wish to revive the jacket-making of their younger days. Louis, a jacket maker who sells patches and jackets through an online store, comments: ‘I do get a lot [of customers] who are older …, and they had their own jackets back in the day, and they’ve either sold them or lost them, and now they see that they can get another one’.

Global Jacket Scenes

If battle jackets, like heavy metal music and culture more broadly, were once considered predominantly Western, today they are increasingly globalised.29 Metal fans and musicians in Australasia, Africa, Asia and South America, as well as Europe and North America, have taken up jacket customisation as part of their identification with metal culture.