There is no dearth of International Relations (IR) scholarship on hegemony. But very little of it combines a concern with both the material world and ideas. Scholarship that does investigate the two does not treat ideas very robustly. Cox is perhaps the most prominent scholar to develop a theory of hegemony that gives prominent places to the material distribution of power, ideas, and international institutions.Footnote 1 Relying on Gramsci's theory of hegemony, Cox and his followers have written about how hegemonic authority rests on objective military and economic power, a legitimizing ideology, and a collection of institutions that can be transmission belts and socialization mechanisms for that ideology globally.Footnote 2 While Cox's theory is indeed quite convincing, its reading of Gramsci left out one of the most important elements in Gramsci's theory: common sense. In Cox's model, ideas, or ideology, are an elite construct about political economy. This reading of Gramsci ignores his deep concern with mass common sense, or the taken-for-granted ideas of publics about social life, and not just class relations.

Meanwhile, constructivist IR theory for the most part, despite its reliance on theories of social constructivism, has mostly avoided theorizing the role of the masses in the social construction of identity. Systemic constructivism, for example, provides a structuralist alternative to systemic realism. It does so by theorizing the distribution of identities, rather than power, in international politics. But these identities are the identities of states constructed through the interaction among states. The social construction of state identities in interaction with their own societies is ignored. One way to bring society back into social constructivism is through Gramsci's conception of common sense, and its relationship to the ideological projects of state elites.

In this article, I offer a neo-Gramscian constructivist account of hegemony that restores common sense to a more central theoretical role, a role as a structural variable in world politics, akin to distributions of material power or national identities. This common-sense constructivism aims at bringing the masses back into world politics. It also advances constructivism's growing interest in the social power of practices and habits—how states automatically perceive, feel, and act without conscious reflection on either costs or benefits or normative proscriptions and prescriptions.Footnote 3 It helps explain the obstacles semi-peripheral elites might have in moving their countries into the core, just as Gramsci lamented the difficulties common sense posed to Italian socialists trying to move the Italian peasantry to opt for progressive change.

I apply this model to the case of contemporary Russia. In so doing, I add insights from Wallerstein's world systems theory, in order to make more coherent sense of Russia's material position in the world.Footnote 4 The bottom line is that mass common sense in Russia is a stubborn barrier to a Russian elite intent on moving Russia into the neoliberal core of the world capitalist economy.

I begin with an analysis of the theorization of hegemony in IR scholarship, and I suggest how Gramsci's understanding of common sense should be incorporated into a constructivist account of hegemony in world politics. I discuss how I use a plausibility probe to assess the possible value of the neo-Gramscian constructivist theory I offer, including discourse analysis and the selection of texts to be analyzed for the recovery of both elite ideology and mass common sense. The empirical sections begin with the objective material positioning of Russia in the world capitalist economy, including both material resources and global connectivity. I then present what constitutes elite Russian ideology from 2007 to 2011 and then compare it to mass Russian common sense. The conclusion discusses the implications of the findings for theoretical accounts of hegemony and IR theory more generally. Recognizing the limits of a plausibility probe, I elaborate on future research strategies that could more convincingly test neo-Gramscian constructivist accounts of hegemony in the cases of Brazil, China, and India.

IR Theory and Hegemony

The earliest and most prominent theorists of hegemony were predominantly materialist in orientation. Kindleberger's argument, which has become standard, concludes that the crisis of hegemony in the 1930s could have been averted had the United States only recognized its material interests in succeeding Britain as the global lender and market of last resort.Footnote 5 Despite Kindleberger's obvious reliance on ideas, or, more precisely, misperceptions of presumably objective interests, IR scholars did not go on to develop a systematic account of ideas in hegemonic transitions. The same could be said for Krasner's hugely influential work on hegemony and world trade.Footnote 6 Arguing that rising concentrations of power in a single state facilitate an open global trading system, and declining hegemons beget closure, Krasner's theory is fraught with some important disconfirming eras in the past 200 years. British decline in the latter part of the nineteenth century did not result in Britain abandoning openness. And the U.S. rise in the 1920s and 1930s did not result in openness. As in the case of Kindleberger, the anomalies were explained by ideas. The City of London, long accustomed to being a financier of global trade and investment, did not recognize Britain's material interests until too late. U.S. finance capital, still parochial and inward-looking, did not recognize U.S. interests in replacing Britain as the global hegemon. Again, despite the reliance on ideas, the latter were not systematically included in any account of hegemony. I could add here the contemporary period of U.S. decline, and its continued commitment to a neoliberal order. Perhaps in twenty years, one could be told that the United States did not recognize its material interests because of its idea of itself as a postwar global hegemon.

Gilpin's theory of hegemony is materialist in the sense that powers rise and fall depending on their relative material economic and military resources.Footnote 7 Indeed, he argues that material decline is inevitable because of the diffusion of technology, knowledge, and best practices from the hegemon to its ultimate challengers. Keohane's account of hegemony also relies on material interests, arguing that hegemons construct international regimes to accord with their material interests.Footnote 8 Their decline may not result in the dismantling of the regime because, first, the regime assumes an institutional life of its own, and so has a material interest in its own perpetuation; and second, because of the material transaction costs that have to be incurred by any new prospective hegemon in its pursuit of creating a new collection of institutions. Snidal, surveying the hegemony literature from Kindleberger to Keohane, also concludes that material interests may save a declining hegemon's institutional arrangements. The master variable for Snidal is the material interests of the “k group,” or the states that are less powerful than the declining hegemon, but still significant enough players to derive continuing benefits from the present arrangements.Footnote 9 But the crucial variable is whether they have material interests in the preservation of the previous system. As I mentioned, however, the material interests posited for states by IR theorists are often ignored by those states' policymakers.

Finally, Wallerstein's world systems theory shares a primarily materialist ontology with the realist and neoliberal theories just discussed. World systems theory provides a macro-historical account of the operation of the world capitalist economy for the past thousand years. Its constantly operating principle is a division of labor in the world between an exploitative advanced core, an exploited impoverished periphery, and a semi-periphery that simultaneously exploits the periphery and is itself exploited by the core. Wallerstein stipulates that three major mechanisms enable a world system: (1) concentration of military power in the core, (2) an ideological commitment to the system as a whole, and (3) the existence of a semi-periphery that is both exploiter and exploited. In raising ideology, Wallerstein quickly robs it of any autonomy by asserting that “I don't mean the legitimation of the system … I mean rather the degree to which the cadres of the system feel that their own well-being is wrapped up in the survival of the system as such.”Footnote 10

Cox is the first scholar to systematically combine material power, ideas, and institutions in a comprehensive theory of hegemony. Relying on Gramsci's insight that hegemony is not only coercion, but subscription to a shared and legitimized ideology, Cox reinterprets British and U.S. hegemony from 1815 to 1985. He argues that British naval power and its ideology of free trade, combined with the institution of the City of London as the world's financial hub, allowed British domination of world politics to endure for most of the nineteenth century. Pax Americana, relying on the U.S. military, a neoliberal ideology of its own, and a far thicker set of international institutions, including the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, or World Bank, and the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs/World Trade Organization (GATT/WTO), has been in place since the end of World War II.

Despite Cox's huge advance over previous scholarship in developing a more complete theory of hegemony that productively marries material power, ideas, and institutions, Cox's theory still falls short of its Gramscian promise. It fails to capture Gramsci's concern with mass public common sense, not just elite ideologies, and it neglects Gramsci's concern with mass ideas about daily concerns, not just attitudes toward socialist or capitalist economic orders.

Cox's narrowing of Gramsci's ideas about common sense in turn narrows Cox's theorization of international institutions. The institutional dimension of hegemony concerns the international mechanisms by which the hegemon's material power and ideas are reproduced by acquiescent partners. Cox's model of hegemony treats institutions as transmission belts for the dominant powers' economic ideology. This is critical but ignores institutions that reproduce hegemonic power more broadly construed. It is not just ideas about how the economy works, or should work, that cement a hegemonic order.

There are more than economic institutions, such as the WTO, at work. Hegemonic orders are also reproduced through the myriad interactions that occur among states and their citizens in cultural, educational, and informational sites. Beyond both economic and security institutions are institutions that are not so tailored to specific functions, but do systematically cultivate hegemonic ideas in their participants. I have in mind here university and graduate education, cultural productions, media-scapes, tourism, and other structures of ideational exchange and contact.

According to Gramsci, hegemonic ideas are those that advance the interests of the dominant classes but are veiled in language that presents them as if they were advancing the universal interests of the people in general. Hegemonic power is maximized to the extent that these ideas become taken for granted by the dominated population. A taken-for-granted truth is one that people assume to be so without questioning its empirical or normative validity. A legitimate truth is one that people consciously regard as “right” in a given context. Hegemonic theorists, to the extent that they treat ideas at all, as Cox certainly does, limit themselves to assuming that the only ideas that matter are ideas about political economy. Ikenberry goes farther in assuming that the ideas that matter are those about the legitimacy of the hegemonic order.Footnote 11 Both are certainly important—but I do not think they get to Gramsci's notion of common sense.

Two problems accompany Cox's translation of Gramscian hegemony into IR: first, it privileges the material in that even the ideas that matter to Cox are ideas about economic order and class arrangements. Nonmaterial ideas about the good life, justice, political or social order, religion, values, norms, family relations, gender, and such are simply excluded from what matters. Moreover, this is not consistent with Gramsci's understanding of common sense. In addition, Cox's ideas are situated exclusively in the minds of ruling elites; publics are absent from Cox's account of hegemony.Footnote 12 But Gramsci's notion of common sense was all about the masses.

For Gramsci, one could not explain whether or not a hegemonic ideology on offer would resonate with the masses/proletariat without an investigation of their everyday common sense. He asserted that “one cannot but start in the first place from common sense” when analyzing a social setting.Footnote 13 There are two steps here, one of intelligibility, and one of legitimacy.Footnote 14 Gramsci addressed both of them. Common sense is not reducible to popular beliefs about political economy. Gramsci conceptualized it much more broadly, linking it, only in the last instance, to popular receptivity to different ideas about political economy and its attendant social and political order.

Gramsci asked “can modern [revolutionary] theory be in opposition to the (spontaneous) feelings of the masses, what has been formed through everyday experience illuminated by ‘common sense,’ that is, by the traditional popular conception of the world… ?” He answered unequivocally: “It cannot be in opposition to them.”Footnote 15 It cannot be in opposition, that is, if it ever expects to be, first, understood by them, and second, taken up as the legitimate way to think about the world. Common sense is “closely linked to many beliefs and prejudices, to almost all popular superstitions.”Footnote 16 Gramsci places so much emphasis on these “popular beliefs” that he calls them “material forces” in and of themselves.Footnote 17 Common sense is “the philosophy of non-philosophers, the conceptualization of the world that is uncritically absorbed.”Footnote 18

What is under discussion here is the “discursive fit” between a set of ideas being propounded by a revolutionary party and the set of ideas, mostly taken-for-granted, that inform the daily life-world of average people. In the context of this article, I am investigating the discursive fit between the Western hegemonic ideology of neoliberal democratic free-market capitalism and Russian elite and popular ideas about how their own local worlds work, and should work. If one ignores Russian common sense, one could be satisfied, following Cox, that if Russian political elites express a commitment to a democratic neoliberal ideology, Russia is helping to reproduce Western hegemony. But this ignores Gramsci's warning of common sense's capacity to thwart elite projects.

Constructivist IR scholars have long been preoccupied with the issue of discursive fit or resonance.Footnote 19 Consistent with Gramsci's discussion of the difficulties socialist organizers encountered in southern Italy, Keck and Sikkink conclude their book on transnational norm entrepreneurs by noting that the ideas being propagated must “fit or resonate with the larger belief systems and real life contexts” of the target societies.Footnote 20 Building on Gramsci and constructivist work on norm diffusion, one can divide discursive fit or resonance into two parts. In its thinnest conceptualization, one can merely look at intelligibility. Are the ideas and positions enunciated by the political elite comprehensible to the broad public? One could call this thin intersubjectivity. A thick conceptualization of discursive fit or ideological resonance would entail not only comprehension, but also evaluative agreement. In other words, not only do the masses understand the ideology, but it is compatible with their own commonsensical view of the good life, of how to go on in the world, of a desirable daily life.Footnote 21

Gramsci was aware that attempts at political mobilization will fail if there is no resonance between the ideology being propagated and mass common sense. But one can apply common sense in a different, but related, context. Instead of revolutionaries trying to mobilize Russian masses to overturn the status quo, Russia's place in Western hegemony depends on whether Russian political elites can convince Russian masses that democratic neoliberalism is compatible with their implicit sense of a good, just, and normal daily life.

Gramsci argues that for any hegemonic project to succeed it must make compromises with common sense. In this way the masses can exercise power over the political elites who are trying to impose their ideology on society. Given that this article is a “plausibility probe” to ascertain the potential value of pursuing common-sense constructivism as an alternative account of international order, it is premature to hypothesize which precise avenues of influence common sense may take in constraining an elite's hegemonic project. Moreover, since common sense is a structural variable, I cannot deduce determinate predictions for how common sense will work its way on policy outcomes. Instead, common sense may make its influence felt politically in myriad different ways. A common sense that is at odds with an elite hegemonic ideology may impose political, that is, selectoral or electoral, costs on an elite that ignores it. Failure to heed mass common sense may result in demonstrations against neoliberal policies, the emergence of alternative political parties and movements, and/or fractionation within the ruling party.

These are examples of common sense in active opposition to political elites. But mass common sense may not be limited to masses per se, or to open conflict. There is no reason to reject the possibility that state officials share the common sense of the masses, and so, in their implementation of the elite's hegemonic project they might behave in ways that undermine elite intentions. This institutional slippage allows common sense to infuse state practices with content contrary to the will of political elites. Finally, common sense works its way structurally, through the vast array of daily practices average Russians employ when going about their daily lives. These can be conscious “weapons of the weak,” or the unconscious habitual conduct of people whose taken-for-granted understanding of daily life is reflected in countless behaviors that daily undermine elite neoliberal prescriptions and proscriptions.Footnote 22

This article determines Russia's material place in the world, the hegemonic project of its political elite, and the relationship of that project with Russian mass common sense. What emerges is a Russia materially situated in the semi-periphery, or even periphery in some respects, of the world capitalist economy. This material semi-peripheriality tracks closely with only the most selective engagement with Western institutions. This semi-peripheriality is paradoxically accompanied by an elite discourse that aspires to become a neoliberal democratic part of the core, or of Western hegemony. This would make no sense at all if it were not that mass Russian common sense tracks nicely with a semi-peripheral, neo-Soviet, self-isolating Russia offering social protection to a people unwilling to tolerate what acceptance of Western hegemony would mean for their daily lives, thereby demonstrating the theoretical power of a theory of hegemony that takes into account mass common sense.

Resarch Design and Methods

As a plausibility probe, this article aims to establish the value of a research program on the connection between mass common sense and international order.Footnote 23 Eckstein suggested one way to increase the validity of a plausibility probe is to choose a crucially hard case for the theory under consideration.Footnote 24 While Russia is not a crucially hard case, it is a hard case in that one would not expect mass common sense to influence policy outcomes in an authoritarian state. So, if the evidence presented here makes a convincing case that mass Russian common sense affects Russian elites, one should expect this to be still more likely the case in more democratic countries, such as India or Brazil, if not China.

Four empirical questions must be addressed: Russia's material position in Western hegemony, Russia's mass common sense, Russia's elite hegemonic project, and the discursive fit between the latter two. Establishing Russia's material position is straightforward. I have gathered both economic data and data on Russia's integration with the rest of the world. Establishing Russian mass common sense is much harder.

Common sense has both depth and variety. What is “taken for granted” may be so commonplace it is never articulated. Taken-for-granted common sense goes unchallenged or uncontested. In other words, there is a kind of consensus about what the world is, or should be, that often goes without saying. But when it is said, most people say more or less the same thing. That is the aspect of common sense that I explore. In order to see just how consensual common sense might be, I look at a variety of mass popular texts. The first are four textbooks on Russian history for seventeen-year-old high-school students.Footnote 25

Western media and some scholars have paid great attention to the alleged whitewashing of Stalinism in recent Russian textbooks. The advantage of collecting a sample of required Russian high-school textbooks is that it provides a more representative sample than merely relying on the two optional college textsFootnote 26 that have been singled out for their revisionist history, identified on the Russian Memorial website.Footnote 27 These two books do indeed present a far more “positive” rendering of Soviet domestic life and foreign policy than the high-school texts sampled for this article, but they are hardly constitutive of Russian common sense, since they are not read by millions of Russian high-school students, and they are outliers in any case in their treatment of the Soviet past.

The second contributor to the sample of Russian common sense is a best-selling novella by Pelevin, A Macedonian Critique of French Thought. The third is a best-selling novel by Marinina, A View from Eternity. Good Intentions, her first foray beyond her wildly popular, and lucrative, crime thrillers.Footnote 28 The last is the 24 September 2009 edition of Segodniashniaia Gazeta/Today's Newspaper from Krasnoiarsk, a city of one million in western Siberia.

These sources are chosen because their audiences are Russia's masses. Nearly all Russian teenagers are in secondary education and are compelled to take courses in contemporary Russian history. The four textbooks are required reading for several million Russian students. Pelevin's audience is the Russian upper middle class and intelligentsia. Marinina's audience is a broad swath of the Russian middle and working classes; her novels are almost ubiquitous on any random Russian subway ride. The newspaper was chosen based on its circulation in a “typical” provincial Russian urban area.

Russia's elite discourse is easier to sample than common sense, but it is not so self-evident as Russia's material position in the world. I read and coded all speeches, press conferences, and interviews given by Presidents Vladimir Putin and Dmitri Medvedev from September 2007 to September 2011 across both foreign and domestic audiences, yielding a sample of 1,446 individual texts. In order to generate a larger sample of elite ideology, I polled twenty experts on contemporary Russian politics, asking them to name the five most powerful people in Russia today. I also looked at the results of Nezavisimaia Gazeta's (NG) anonymous survey of twenty-seven experts: political scientists, political “technologists,” sociologists, representatives of the media, and representatives of Russia's political parties. Each year the newspaper asks them to rank the most powerful people in Russian political life.Footnote 29 Based on my poll and that of NG, the rankings of the most powerful are unanimous: Putin, Medvedev, Vladislav Surkov, Igor Sechin, Aleksei Kudrin, and Sergei Ivanov.Footnote 30 While the speeches of Putin and Medevedev have been systematically posted on the web since 2001, those of Surkov, Sechin, Kudrin, and Ivanov are not so universally available.Footnote 31 I have sampled them for the past five years using the yandex.ru search engine.

One of the advantages of a large-n discourse analysis is the capacity to put the most famous remarks of Putin about the Soviet Union in April 2005, namely, that its disappearance was “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century,” into context. First, it was uttered a single time and hence is hardly representative of Putin's dozens of other negative characterizations of the Soviet Union. And second, and most importantly, it was made in the context of the U.S. decision to unilaterally invade Iraq in March 2003, over the opposition of most of the rest of the world, including its North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) allies.

Russia's Position in the World

The most recent economic data available places Russia squarely within the semi-periphery of the world capitalist economy. Compared to the highly developed U.S., European, and Japanese core, Russia lags on many indicators of economic development. But compared to countries in the economically underdeveloped periphery, Russia is clearly closer to the core. While it has some peripheral characteristics of its own, such as being primarily a raw material and energy exporter, it also has its own regional periphery that it exploits like a typical semi-peripheral player. In this sense, Russia materially reproduces Western hegemony through its objective material position in the world capitalist economy. On the other hand however, and consistent with a counterhegemonic common sense at home, Russia is significantly more isolated from Western hegemony, institutionally speaking, than other, similarly situated, semi-peripheral states. Both these measures of Russia's position are elaborated below.

Russia's Semi-Peripheral Position, Materially Speaking

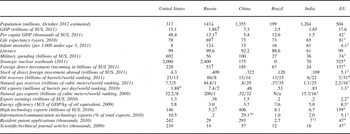

On most measures, Russia is located squarely in the semi-periphery, ranked around other semi-peripheral states such as China, India, and Brazil, but far behind core states such as the United States and Europe. Figure 1 illustrates Russia's semi-peripheral position.

FIGURE 1. Relative material capabilities

Russia's population, life expectancy, gross domestic product (GDP), per capita GDP, and level of annual foreign direct investment (FDI) place Russia squarely within the semi-periphery. But the concentration of that growing foreign investment primarily in the area of raw material extraction underlines Russia's peripheral status. Russia is emerging as a significant source of FDI abroad, but primarily in the former republics of the Soviet Union and Eastern and Central Europe. This cements its position as a part of the semi-periphery, both exploiting its own periphery, while simultaneously serving as a raw material appendage for the core. Russia's overseas investments are dominated by the same sectors that dominate its economy, state budget revenues, and foreign trade: energy and metals, accounting for about half Russia's foreign investment in 2006. Boston Consulting Group, however, includes only six Russian companies as “global challengers,” based on revenues, international presence, and overseas investments, compared to thirty from China, twenty from India, and thirteen from Brazil.Footnote 32

Russian foreign investment has concentrated in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), all of which are former Soviet republics. Armenia, Belarus, and Uzbekistan accounted for over three-quarters of that investment.Footnote 33 All of this shows Russia's material position as a regional semi-peripheral hegemon dominating its local periphery. The content of Russia's exports also demonstrates its semi-peripheral position. While earning $380 billion from its exports in 2010, 49 percent of this total came from oil and natural gas, only 5 percent from manufactured products. Only $5 billion of this, or much less than 1 percent, came from high-technology exports. Only three-fifths of 1 percent of Russian exports were information technology or telecommunications equipment. Looking at the “Balassa index of revealed comparative advantage,” one sees that Russia's competitiveness is almost completely concentrated in raw materials and energy.Footnote 34 Finished products rarely figure in the mix, with the important exception of weaponry. Of the top twenty most competitive Russian exports on the world market, only nuclear reactors, armaments, fertilizers, rolled steel, and boilers are nonperipheral products.Footnote 35 In several measures of technological prowess or potential, patent applications, scientific journals, and scientific and technical journal articles, Russia also is firmly semi-peripheral.Footnote 36

In sum, materially speaking, with the exception of military power, rates of infant mortality, and literacy, Russia is an unambiguous member of the semi-periphery: a country whose income is middling, whose export mix is dominated by low value-added raw materials, whose inward foreign investment is concentrated in producing the raw materials needed by the core economies, whose own foreign investment is directed primarily toward its periphery, and whose technological and educational development still ranks it among other semi-peripheral countries.

Russia's Relative Isolation from Western Hegemony, Practically Speaking

A semi-peripheral country should contribute to the core's reproduction of its hegemony by participating in those institutional arrangements that facilitate the propagation of its ideology and its material power. I have shown that Russia certainly contributes to the material reproduction of the core by its role as raw material and energy exporter and site for foreign investment. But institutionally speaking, Russia is less connected to Western hegemony, and so less reproductive of its ideology, than one would expect from a typical semi-peripheral state. Later, I suggest this is because of a counterhegemonic mass common sense prevailing in Russia, but for now, I present evidence on Russia's relative isolation from Western hegemony.

In terms of Internet use and broadband availability, Russia has little communication with, and connectivity to, the rest of the world. According to indexes of international connectivity, Russia finds itself far behind the United States and the West, and mostly behind the other BRICS.Footnote 37 In a similar measure, the 2010 Digital Economy rankings of the Economist Intelligence Unit, Russia again is far down the list, at fifty-ninth, slightly behind China and India, and well behind Brazil. Russia does much better than both China and India, although still behind Brazil, in the Knowledge Economy Index of the World Bank, largely because of its high levels of literacy and universal access to education. Even so, it is still semi-peripheral.

The Foreign Policy “globalization index” includes measures for political engagement (foreign aid, treaties, organizational memberships, and peacekeeping), personal contacts (phone calls, travel, and remittances), technological connectivity (Internet users, hosts, and secure servers), and economic integration (trade and FDI). Of 125 countries rated in 2011, all emerging economies are relatively “unglobalized,” with Russia ranked fifty-second. While there is a pretty strong correlation between prosperity and high rankings, Jordan is ranked ninth overall, Malaysia twenty-third, Panama thirtieth, Ghana thirty-third, the Philippines thirty-eighth, and many other lower-income countries above the BRICs, including Russia.

On another, perhaps increasingly archaic, measure of global interconnectivity, international postal traffic, Russia is relatively isolated. In the age of e-mail, most countries' international postal traffic peaked in 1996–97, but the figures are striking, nonetheless. Russia ranks second to last among BRICs, above only Brazil, in the sending and receiving of mail internationally, with only about 32 million letters in 2007. This compares with more than 800 million in the United States in the same year (which peaked at nearly one billion in 1996).Footnote 38

According to the 2010 Quacquarelli Symonds Top 200 Universities,Footnote 39 Moscow State University, at ninety-third, was the only Russian school to make it into the top 200. More telling, however, is the absence of any Russian business schools in the top 100, according to the Financial Times ratings of 2011. This newspaper, given its ideological commitment to neoliberal economics, is a perfect source for measuring how deeply Russia is integrated into the world capitalist economy. If Russia has business schools with faculty and curriculum devoted to mastering the hegemonic canon, it is good evidence of progress toward training Russians to participate in that hegemony. Instead, Russia has zero top-one-hundred business schools, implying that Russian business elites are not being captured by neoliberal orthodoxy, at least not in their formal training.

One of the most important institutions of hegemonic reproduction are universities and graduate schools. The more foreign undergraduate and graduate students a country can educate in its own universities, the more likely its hegemonic ideology will be propagated throughout the world. Two features from the data in Figure 2 stand out: first, the United States and the core dominates the education of the rest of the world; second, Russia is a solid semi-peripheral player, educating many thousands of students from its regional periphery.

FIGURE 2. Relative global integration

Almost one million foreign students are at U.S. and UK universities, accounting for more than one-half of all foreign students abroad. The United States and Western Europe account for two-thirds of all foreign students. In terms of the semi-peripheral countries that I track in this study, each of them sends the overwhelming majority of its students to hegemonic centers. The top five destinations for Chinese students are the United States (110,000), Japan (78,000), Australia (58,000), the UK (45,000), and South Korea (31,000). A third of Brazilian students abroad study in the United States. The top five destinations for Indian students are the United States (95,000), Australia (27,000), UK (26,000), New Zealand (4,000), and Germany (3,000). Russia, as well, while in far smaller relative numbers than either China or India, has most of its students opting for education in the core. The top five destinations for Russian students are Germany (10,000), the United States (5,000), Ukraine (5,000), France (3,000), and the UK (3,000).

But at the same time, Russia, while hosting only 60,000 foreign students, has become a regional core for a number of peripheral countries, fulfilling its role as a true semi-periphery. Students from Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia, and Ukraine make Russia their top choice for studies abroad. Central Asia is the only region in the world for whom North America or Western Europe is not the top spot for studies abroad. Only 17 percent of them go to school there, while 78 percent of them travel to Eastern and Central Europe and elsewhere in Central Asia.

Finally, Russia is a relatively rare destination for international meetings. The Union of International Associations reports that in 2009, there were almost 8,900 meetings of international organizations with at least 300 participants of which at least 40 percent were foreigners to the host country. Again, it is the practical significance of this that matters. Somehow, Russia is neither desired as a site for the rest of the world, nor is Russia making effective efforts to make itself into a more desired locale. More interestingly, perhaps, is that Russian elites are trying to make Russia more attractive, but it has not worked. Either the rest of the world still prefers other destinations, or the Russian public, through its own commonsensical daily practices, thwarts the efforts of Russian elites to make Russia into a site that resonates with the rest of the world.

To summarize Russia's material place in the world, by most economic measures it is squarely in the semi-periphery, simultaneously a raw-material appendage of the core and a neocolonial investor and trading partner with its own collection of peripheral states. One critical anomaly, however, concerns its relative lack of connectivity with the rest of the world, partly depriving Western hegemony of its full potential in colonizing Russia ideologically. By having less communication with the world, hosting fewer international meetings, visiting tourists, and foreign students, Russia has denied the West full hegemonic advantages. On the other hand, as I will show, this lack of integration into Western hegemony is consistent with Russian common sense, but not with the elite's hegemonic project.

Elite Russian Discourse and Mass Common Sense

Elite Russian discourse reflects a semi-periphery that aims to become a member of the democratic neoliberal core, a part of Western hegemony. Meanwhile, Russian mass common sense does not reflect this aspiration, neither in positively asserting the desire to become part of Western hegemony, nor in having features that resonate with elite discourse. Instead, it is infused with a neo-Soviet identity for Russia that makes it a less-than-perfect fit with the democratic neoliberal project. The Russian elite has not succeeded in masking its neoliberal ideology in such a way as to make it resonate with taken-for-granted Russian realities.

Elite Neoliberal Discourse

One could position the six members of the Russian political leadership used to uncover Russian elite discourse along a continuum ranging from Kudrin and Medvedev, who are the most consistent advocates of a Russian move from the semi-periphery to the Western core, to Ivanov and Putin, who are solid proponents of such a course, but who are also more accommodative to Russian common sense, to Surkov, who is most open to permitting common sense to dictate the terms of Russian entry into the world capitalist economy.

According to elite neoliberal aspirations, Russia should be joining the world market economy, adopting neoliberal economic market principles at home, developing an economy that can export competitive industrial and high-technology products, attracting foreign investment and expertise, and adopting modern European standards of domestic economic regulation. Such a positive vision of Russia's aspirations comes with a negative Other that must be rejected or transcended. This includes most of the Soviet economic and political, if not social, past, Russia's continuing position as a raw-material appendage of the world economy (or its position as a periphery, not semi-periphery), the Wild West capitalism and democracy of the 1990s, and any attempts at economic autarky. There is also a recognition that Russia has its own periphery in the post-Soviet region.

Export-led growth

One canonical position of neoliberal hegemony is that states should develop industries that can competitively export goods, and import those goods that are produced more efficiently abroad. They should not engage in import substitution, or the protection of industries that are not competitive relative to foreign producers, in order to save jobs or domestic production capacities. Russian elite discourse on this element of neoliberalism is the most mixed of them all, often reflecting the mass commonsensical position of social protection from free trade. One might expect the Russian elite to systematically talk like neoliberals on the international stage while reassuring Russians at home that they are committed to social protection. Wanting to present itself as ready for the neoliberal core, Russian elites should express their commitment to the neoliberal orthodoxy. But wishing to assure Russian workers and businesspeople that they will not throw them to the wolves of the most developed parts of the world capitalist economy, they should point out how they are protecting them from competition. This would be an instrumentally rational use of discourse. Instead, Russian elites present a consistently ambivalent view about free trade and social protection regardless of prospective audience costs, implying a less-than-wholehearted elite commitment to neoliberal hegemony.

When speaking before the Russian airline industry, for example, Medvedev explained that he and the Russian government would like to be able to create conditions for the privileged purchasing of Russian planes, but that he could not do that until they produce planes that could compete with foreign planes on price, quality, fuel economy, noise, avionics, etc.Footnote 40 In a meeting with foreign reporters, Medvedev explained to them why Russia, and any other country for that matter, should restrict the presence of foreign media on their soil to allow their own sovereign media to develop. He concluded, “I imagine you take the same view with regard to your own countries.”Footnote 41 So much for a neoliberal market in information.

Open to foreign capital

Also consistent with aspiring to become part of the neoliberal core are the frequent efforts by Russian elites to attract foreign investment to Russia, and not just capital, but also the arrival of foreign technicians, specialists, and scholars to live and work in Russia and share their expertise.Footnote 42 As on the issue of export-led growth versus import substitution, Russian leaders not only advertise their country as open for foreign capital when speaking with foreign leaders and businesspeople, but do so as well to more skeptical domestic audiences. In Bashkortostan, Putin expressed embarrassment at the low level of foreign investment in Russia:

Foreign investment outside the financial sector is on the rise here. It came to $28.6 billion in 2006, and reached $24.6 billion for the first half of 2007, as I mentioned in my opening remarks. This is 1.5 times more than last year. This looks like a good result, but compared to other developing markets there is still a long way to go. [It is] right to compare us to some of the Eastern European countries. You can see here on the graph. It is shameful to look at.Footnote 43

In a discussion on education in Magnitogorsk, Medvedev commented that Russia should be inviting many more foreign academics to teach in Russian universities, and that “an influx of foreign students and certainly lecturers is a very positive factor, and should be viewed as one of the indicators of the quality of education.”Footnote 44 Surkov criticized “the stupid distrust of foreign specialists,” pointing out that foreigners had helped establish the Russian Academy of Sciences, “even the autarkic Bolsheviks invited foreign specialists,” the rest of the world is doing it, and it is “only strange and Soviet” to think differently.”Footnote 45 Medvedev directed attention to the international rankings of countries on their “investment climates,” and he noted that Russia was 120th out of 183 countries, while “our closest partners, Belarus and Kazakhstan, are 58th and 63rd, respectively … and unlike Russia, they are moving up the list.”Footnote 46 In terms of foreign investment, Russia was not just semi-peripheral, but slipping into the periphery.

Privatization

Consistent with the neoliberal canon, the role of the state in the economy must be curbed over time. In his November 2009 address to the Federal Assembly, Medvedev declared that “state enterprises have no future in the modern world.”Footnote 47 In June 2010, Medvedev announced a one-third reduction in the number of state enterprises in Russia.Footnote 48 At the Davos meeting in January 2011, Medvedev even took to task the neoliberal core for responding to the 2008 global financial crisis with anti-neoliberal measures:

During the financial crisis, many states considered that course of action and many of them chose that option, including states with highly developed liberal economy. We don't have a sufficiently developed economy in Russia but we did not resort to that option, and I believe we were right in doing that. I am confident that in most cases it is possible to find solutions to crises through the efforts of the private sector, and in the long-term perspective, this is the most effective way of dealing with things.Footnote 49

Capitalist education

I note that Russia's lack of a single top-one-hundred business school demonstrates the failure of Russia to be fully integrated into neoliberal hegemony. Medvedev recognized this as a problem that must be rectified, rejected any “third path” for Russia, and intimated a desire to be a normal participant in neoliberal hegemony:

With regard to business education … it was not up to scratch until Russian business realized that we had been following our own distinctive path, as the classics said, whereas we should be following the global path. But we have a few achievements too. We have been trying to establish such business schools. I hope we will see some success in this area; at least, I hope the business school at Skolkovo will be a success. I don't know, maybe I'm being overly optimistic, but we tried to follow international standards there.Footnote 50

Escaping the periphery

One of elite Russia's greatest fears is remaining a raw-material periphery. Surkov, in a speech before the Russian Academy of Sciences in June 2007 in which he elaborated his theory of “sovereign democracy,” put Russia's position most eloquently:

People come to our country to buy oil, gas, and the notorious round timber … We are not the engineers, the bankers, the designers, or the producers and managers. We are the drillers, the miners, the lumberjacks. So we are the rather dirty-faced fellows from the working-class suburbs … What are we … doing feeding the mosquitoes in the oil-bearing swamps? We are such cultured and talented people.Footnote 51

Putin tried to link Russia's quest to become a member of the capitalist core to the country's very survival as a relevant player in world politics, asking, “What choice can there be between the opportunity to become a leader in economic and social development, a leader in ensuring our national security, and the threat of losing our economic standing, losing our security and ultimately even losing our sovereignty?”Footnote 52 In an interview with Der Spiegel, Medvedev lamented that “the trade in raw materials is like a drug,” and “a road to nowhere.”Footnote 53

Being Western, European, modern, civilized, and developed

The rejection of any unique Russian way to modernization, as well as the repudiation of any Russian pretensions to a universalist ideology are connected to a frequent invocation of Western modernity and civilization as the endpoint for Russia's contemporary project. It should be noted that these positive references to the contemporary West as Russia's aspirational Other are made primarily before domestic audiences. In addition, it is worth remembering how recently elite political discourse in the Soviet Union just twenty-five years earlier was devoid of any positive identification with the West at all.Footnote 54 Besides broad statements about modernity and civilization, Putin and, especially Medvedev, identify countless features of daily life in the neoliberal core that Russia should emulate, and soon. Perhaps most revealing are the many discursive asides, the casual, taken-for-granted quality of the West, Europe, and the United States, as the model.

For example, in discussing new housing construction in Russia, Putin commented that “these are decent houses by not just Russian but also American or European standards.”Footnote 55 Medvedev preferred how people drove in other countries,Footnote 56 wondered why Russia did not have its own “Discovery Channel” like in the United States,Footnote 57 suggested that Russia get rid of its many time zones (eleven) since the United States had far fewer,Footnote 58 hoped that the practice of private philanthropy would develop in Russia,Footnote 59 wished that Russian companies would treat their workers in Russia as well as Western multinational companies treated them,Footnote 60 proposed borrowing U.S. and British models of education for gifted children,Footnote 61 recommended the new Russian Law on the Police adopt the “Miranda Warning” from the United States and change the name of the Russian police from “militsia” to police,Footnote 62 agreed that the number of citations should be used to assess the quality of Russian academics,Footnote 63 and singled out U.S. baggage inspections systems at airports to counter terrorism as the model Russia should emulate.Footnote 64

There was also explicit Russian identification with Europe and European standards of life. Speaking in Ulyanovsk, Medvedev tried to convince his audience that there was no reason to develop Russian standards or practices. “We need to bring our technology and our road and infrastructure construction costs in line with international standards, with European Union standards.” And he noted that he met resistance on this issue. “When this subject comes up I hear the lament that we cannot do this because our conditions are different, our life is different, the Europeans have their standards, but our case is special and we will continue following our own road as we have for the last decades.” He rejected this unique Russian path, instead arguing for the incorporation of European standards into Russian practice. He concluded, “there are no irresolvable problems here.”Footnote 65

On the 150th anniversary of Alexander II's emancipation of the serfs, Medvedev took advantage of the moment to compare Russia then with the current Russia. He argued that Russia was at “the same crossroads” then, either to follow Europe, or not. As now, “Russia also needed to change, to become an advanced country that shares values with Europe.” He then disparagingly compared that choice, the European choice, to the mistaken choices of Nicholas I and Stalin, both of whom turned away from a “normal, humane order.”Footnote 66

Becoming a democracy

Joining the hegemonic Western core is more than just neoliberal economic policies; it is about democracy, as well. With the important exception of Surkov, there has been an elite commitment to the universal principles of democracy as practiced in the West, and pleas to the core to realize that Russia is just twenty years old or so, and so is still on the road to becoming the core. But what it is not is some “special” kind of democracy, some third way, some unique brand of democracy. Or, at least, that is not the aspiration. Again, one might expect that Russian leaders would make pledges about its commitment to Western democracy before Westerners; and it does. But they also make the same pledges at home.

Medvedev linked the slow pace of democratization in Russia to the experience Russians had in the 1990s with what they understood as democracy: economic dislocation, corruption, violence, criminality, and political instability.Footnote 67 Putin, in an appearance before the Valdai discussion club, a meeting of foreign analysts of contemporary Russia, declared that “there is no other road we can take and there is no question of inventing some kind of home-grown local-style democracy. But this road is not simple.” Russia has needed time for the free market economy to develop and produce a large middle class, “which is to a large extent the standard bearer of this ideology.”Footnote 68

Rejecting (mostly) the Soviet past

If Russia has been aspiring to join Western hegemony in its core, one should expect that the Soviet past, its economic, political, and social system, would be rejected. And this is precisely what has occurred. Moreover, what positive regard there has been for the Soviet project has concerned those features of the Soviet past, such as its education system, that could contribute to impelling Russia into the neoliberal core today.

Putin and Medvedev continually have blamed the Soviet past for many of the current features of Russia that have been obstructing its progress on the democratic neoliberal road. As Medvedev ruefully concluded, “we have a semi-Soviet social system, one that unfortunately combines all the shortcomings of the Soviet system and all the difficulties of contemporary life.”Footnote 69 There are many ways in which disparaging the Soviet past has fed into making Russia an appropriate candidate for assuming a place in Western hegemony. The first has entailed a rejection of any universalizing mission, that is, a rejection of Russia as a model for others to follow, as opposed to an acceptance of Russia as part of an already ongoing Western project of democratic neoliberalism. Putin, for example, told the Valdai discussion group, that he had “no wish to see our people, and even less our leadership, seized by missionary ideas.” Instead, unlike in Soviet times, “[we] need to be a convenient partner for all members of the international community.”Footnote 70

In rejecting authoritarianism, Stalin's terror, the state authorities' habitual distrust of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), the lack of any competition with the Communist Party, the falsified history in Soviet textbooks, the treatment of foreign businesspeople as if they were spies, the repressive criminal code, and the restraints on free speech, Putin and Medvedev have paved the way for the adoption of the liberal democratic governance model of Western hegemony.Footnote 71 As Medvedev put it in referring to contemporary Russian attitudes toward the brain drain from Russia abroad: “We cannot have Soviet attitudes about it.”Footnote 72 This sentiment applied to most aspects of the Soviet project.

Putin and Medvedev also criticized the Soviet past for making it harder to implement neoliberal economic reforms. Soviet agriculture was a disaster.Footnote 73 The “cult of the state” has made contemporary Russians too dependent on the state for welfare and social security.Footnote 74 The Soviet Union left Russia with hugely inefficient and politically influential single-industry towns.Footnote 75 Soviet neglect of health and safety regulations in the workplace has continued to influence contemporary Russian practices.Footnote 76 The Soviet economic model, in general, was a failure, and led to the collapse of the Soviet Union.Footnote 77 Soviet environmental policies, or the lack thereof, have left Russia with vast wastelands of ecological catastrophe.Footnote 78 The Soviet economic and social model has left Russians with a deep suspicion of private businesspeople and entrepreneurs.Footnote 79 “The Soviet Union, sadly, remained an industrial and raw materials giant and proved unable to compete against post-industrial societies.”Footnote 80 Today's Russia faces the same fate unless it adopts neoliberal economic prescriptions. As Medvedev warned, “we have only a relatively short time to get beyond the point of no return to the models that would only lead our country backwards.”Footnote 81

What Russian elites valued about the Soviet past for the Russian future were features they thought would facilitate Russia's reentry into the core. Before foreign audiences, in particular, Soviet relations with the developing world were recalled as supportive and generous, and as serving as a good basis for bilateral relations today. In Windhoek, Namibia, for example, Medvedev not only reminded the media that the Soviet Union had helped gain Africans their independence from colonialism, but that, “unlike many European countries, we do not have a painful, somber colonial history.”Footnote 82 The Soviet education system, especially in areas of science, math, and vocational-technical training was singled out as an element of the Soviet past that should be resurrected in Russia, if it was ever to become a modern economic power.Footnote 83

Russia's movement toward the core

Russian elites repeatedly have acknowledged that Russia has been in a period of transition; it is becoming a member of the neoliberal democratic core. Often, most especially before foreign audiences, these leaders have pleaded for patience for Russia, explaining away its failure to live up to Western democratic ideals as a function of Russian immaturity, its location at only the beginning stages of modernization. Explaining the continuing need for a heavy state hand on civil society and the economy, Putin predicted, or promised, that “the growth of the middle class in Russia will certainly stabilize the political system and social life, but all of this takes time. Once we have a more consolidated and stable legal, economic and social foundation there will be no need for the manual/rukovoi/hands-on regime.” When asked for how long, Putin replied, “I think fifteen to twenty years.”Footnote 84

Medvedev advanced the same perspective, arguing that “there is no doubt that Russia is a democracy. There is democracy in Russia. Yes, it is young, immature, incomplete and inexperienced, but it's a democracy nevertheless. We are still at the beginning and for this reason we have a lot of work to do.”Footnote 85 He pointed out that “we have only been working on building political parties for ten years.”Footnote 86 Russia's failure to protect human rights is because “we are currently at an initial stage in the formation of our own political and legal system.”Footnote 87 The judicial system, in particular, Medvedev saw as “in a state of development.”Footnote 88 As an obstacle to the neoliberalization of Russia, Medvedev observed that Russia “is only beginning to protect property rights.”Footnote 89 It has only begun to develop a domestic financial market.Footnote 90 While visiting Brazil, Medvedev identified both Brazil and Russia as examples of modernizing, developing countries, placing Russia squarely in the semi-periphery with Brazil.Footnote 91

Russian common sense as an explanation for Russia's semi-peripheral position

Russian elites generally identify Russian mass common sense, habits, and customs as a major obstacle to the realization of elite plans. The only exception is Surkov, who argued that common sense must be treated as the foundation upon which the new Russia should be built. Both presidents, although especially Medvedev, spoke of the “bad national habits” Russians have, habits that make them averse to the kinds of changes necessary to make Russia part of the neoliberal democratic core. What average Russians have taken for granted as the good life has been an obstacle to the neoliberalization of the Russian economy and the democratization of the Russian polity.

The bad national habit Medvedev described most frequently was the Russian habit of tolerating corruption and criminality. And he did not attribute this habit to the Soviet legacy alone, but to centuries of cultivation in Imperial Russia, as well. “I have said in the past and will say again that disregard of the law, legal nihilism, has become deeply entrenched in the national psyche.” And to combat it Russian elites “need to help people develop the realization that we need to be guided in our acts by the law and not by some other instinct.”Footnote 92 Instincts and psyche are the language of habit and common sense. Having created a National Anti-Corruption Council, Medvedev told its members, “you know, corruption has become a way of life in our country.”Footnote 93 In the September 2008 meeting with the Valdai discussion group, Medvedev pointed out that “unfortunately, the history of [the] eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and especially the history of the twentieth century in Russia is the history of a disregard for the law.”Footnote 94 Passing a law hardly ensures its observance. In a discussion with small businessowners, Medvedev noted that a law banning unscheduled inspections of small businesses had been passed, but “Let's see what will come of this, because we know that once something in Russia is forbidden, people often find a way of getting around it.”Footnote 95 In a discussion about the environmental degradation of Russia, Medvedev observed that leaders make a lot of decisions, “knowing beforehand that they won't be enforceable. And then, in accordance with our national habits, we don't bother to implement them.”Footnote 96 Later, Medvedev concluded, “Russia is ill with its disregard of legislation.” He then confessed: “Do I have a strong medicine against it? I will tell you the truth—I do not.”Footnote 97 On following the rules of the road, or, not following them: “No one really cares and so we bury tens of thousands of people annually.”Footnote 98

Medvedev blames Russian habits for the difficulty in implementing neoliberal market reforms, as well. Russians had a view of private property “that is less private than in other European nations. It is due to the fact that communes … were the core of the Russian society up until the early twentieth century. Later, as you know, we completely ceased to be part of the global development process with private property being nonexistent.” He concluded that Russian “social habits require a certain adjustment.”Footnote 99 Speaking to a congress of the United Russia political party, Medvedev declared that Russians also have bad “national working habits.” They have problems with “neatness, carefulness, and diligence.”Footnote 100 In an interview with the Financial Times, Medvedev argued that economic reform depended on “overcoming these habits,” especially mass hopes in leaders, czars, Stalin, rather than in themselves.Footnote 101

In his broad conclusion about the effects of these bad Russian habits, Medvedev asserted “we now have to work with this set of national customs and habits. But … this does not mean that we need to take these habits with us into the twenty-first century. We would have done well to leave some of them in the twentieth or earlier centuries.”Footnote 102 Similarly, “we have an enormous number of dubious traditions that should not be maintained. They are absolutely nothing to be proud of.”Footnote 103 Most critically, Medvedev recognized that mass common sense is not confined to the masses, but many, if not most, bureaucrats have been similarly socialized into a tolerance for criminality and corruption, contempt for the law, distrust of private entrepreneurs, and suspicion of independent initiative.Footnote 104

Surkov, on the contrary, attributed the failure of previous efforts to modernize Russia—by Stolypin, Stalin, Gorbachev, and Yeltsin—to the failure to recognize that “Russia has no future beyond the bounds of its own culture. Culture is our fate.” In particular, Russian common sense expects the centralization and personification of power, not decentralization and institutional pluralism. At best, there can be a “rapprochement” between the democratic neoliberal project and common sense. Having foreign specialists and FDI, for example, is “a price that has to be paid for an innovation-based Russian economy,” for a Russian transition from semi-periphery to core. He concluded that Russia's ideal future is to become “a globally significant economy of intellectual services, a flourishing sovereign democracy.” It bears stressing that Surkov alone among the Russian elite regarded Russian common sense as a foundation upon which to build instead of a foundation that must be gradually razed.

Russian semi-peripheral practices

Despite an elite discourse suffused with aspirations to become part of Western hegemony, Russian elites have clearly recognized where Russia is now: a semi-peripheral regional power. And they have endeavored to build the relationships and institutions that will allow Russia to be a solid core for its local periphery. The collapse of the Soviet Union created fifteen states out of one. But these new sovereign borders left in place an infrastructural network: pipelines, electricity grid, transportation links, and interdependent industrial production that objectively entangled each of the new states, imposing huge transaction costs on any effort to restructure these relationships. The Baltic states immediately chose to incur those costs, and reoriented their economies as quickly as possible toward the West. Perhaps Georgia has been attempting to do the same, but from a far more constrained geographical position.

Russian elites not only recognized these objective structural factors, but increasingly realized that there was a common sociocultural and political legacy left by the Soviet Union that also bound Russia to the other former Soviet republics. Anatolii Chubais, one-time leader of the liberal Yabloko Party, and simultaneously chairman of the Russian energy conglomerate, United Energy Systems (UES), gave this strategy the name “liberal imperialism” in an October 2003 Nezavisimaia Gazeta article. Although intended as a plea to adopt a less forceful foreign policy in the “Near Abroad,” it still advocated the neocolonial penetration and exploitation of Russia's regional neighbors. While the name has not been officially adopted, Russian practices have been perfectly consistent with a regional hegemon taking advantage of its relative economic superiority. As noted, Russian foreign investment has been concentrated in these post-Soviet countries. Moreover, through the widespread core method of debt for equity swaps, Russia has turned the energy debts of many post-Soviet republics into Russian ownership of electricity grids, hydroelectric dams, nuclear power plants, railroads, oil and gas pipelines, and industrial plants.

There has also been hope, whether through the Eurasian Economic Community, or more informally, through the weight of the Russian market in the region, for the Russian ruble to become the regional reserve currency.Footnote 105 In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Russia established a $10 billion stabilization fund for the region, a clear institutional substitute for core hegemonic institutions such as the IMF.Footnote 106

More recently, Putin and Medvedev have recognized various “soft power” resources Russia might deploy to deepen its hegemony in the region. They have understood that the Russian language, the lingua franca for many in the post-Soviet world, has been an institutional resource that should be nurtured. Putin noted the creation of “Russkii Mir,” or the Russian equivalent of Goethe House or Le Maison Francaise, as a vehicle for Russian language instruction in the near abroad. The Russian government also has been eager to supply countries such as Kazakhstan with Russian-language textbooks.Footnote 107 Putin also has announced the restoration of the old Soviet practice of holding “years of x-country's culture,” as opportunities to disseminate translations of Russian books into various local languages and the latter into Russian. Of course, he reassured those attending the CIS summit in Moscow, that the new “years of culture” would not replicate the “formalism” of Soviet years.Footnote 108 The Russian government has created the annual “Pushkin Medal” as a prize for efforts on behalf of “Russian language, culture, and literature.”Footnote 109

Russian universities have been opening a growing number of campuses in former Soviet republics, such as Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan. All nine CIS states have universities involved in the “CIS Open Network University,” for example.Footnote 110 As I noted, several post-Soviet countries have been the only countries in the world that have sent their students primarily to Russia for education, rather than to Europe or the United States. Medvedev showed a keen appreciation of the soft power associated with foreign students learning in Russia:

I am sure that these are investments that will pay off a hundredfold, because these are our students, our people in the broadest sense. They graduate from Russia's universities, and then go back to their native countries, and our bonds with them remain strong, so in the future they will help us build relations with their nations and help us solve the challenges that Russia faces. These are people who in a literal sense speak the same language and have the same educational level, the same higher education qualifications. So this is an extremely important issue.Footnote 111

Medvedev turned foreign students into “our students, our people,” expressing great confidence in Russian ability to cultivate a regional hegemony through the hearts and minds of peripheral elites.

One might say that Russian leaders recognize that they and their colleagues in the near abroad share the same “habitus,” that is, “we speak the same economic language and share the historical traditions. [Therefore] we are in the best situation” to pursue “economic integration.”Footnote 112 As Medvedev told his Kazakh hosts, “the fact that in the 1990s a boundary line was drawn between our countries does not mean that the hearts of our people were divided.”Footnote 113 Another effort to forge a common post-Soviet identity for the region was the creation of the “Year of the Veterans in the CIS,” an effort to make the Soviet victory in World War II a common experience to be commemorated not by Russia alone, but by all those who shared the “same” historical event: its slogan: “We Won Together.”Footnote 114 Using the very language of Gramscian hegemony, Medvedev refers to the CIS as Russia's “natural” partners, objectivizing Russia's authority in the region. Especially close relations are expected with the “fraternal” states of Ukraine, Belarus, and Kazakhstan.Footnote 115 This ethnonational affinity has been expected to be reinforced by the efforts of the Russian Orthodox Church, an institution with many affiliates in each of the post-Soviet republics.Footnote 116

Whatever doubts there have been of the CIS ever becoming a European Union of Eurasia, it has been an institution of Russian regional hegemony to the extent it can regularly hold CIS-wide meetings that create a kind of shared collective identity. For example, beyond the regular meetings of presidents, foreign, defense, interior, and emergency ministers, there have also been meetings of various social groups, such as the intelligentsia and young scientists.

Russian Common Sense: Mass Support for Remaining Semi-Peripheral

Russian mass common sense mostly contradicts elite neoliberal discourse and more accurately reflects Russia's objective semi-peripheral position. One could say that Russian political and economic elites, whether intentional or not, have ended up implementing, or practicing, Russian common sense, as much, if not more than neoliberal discourse. The objective material position of Russia can be explained by Russian common sense. The latter shows virtually no positive regard for neoliberal economic principles or liberal democracy.Footnote 117 It also has little to criticize about daily corruption and criminality in society. Moreover, while critical of the Soviet experience, it is far more positive about many features of Soviet life than elite discourse. Finally, while Russian common sense is as enamored of Western material accomplishments as elite discourse, it wishes to consume them, but not adopt the neoliberal practices that elite discourse thinks is necessary to attain them. In other words, Russian mass common sense is a bulwark of Russia's semi-peripheral position in Western hegemony, and hence a significant obstacle to Russia's elite aspiration to join the neoliberal core, just as the Russian elite, save Surkov, have recognized and lamented.

With the single exception of a reporter in Krasnoiarsk who argued against protectionism for Russian shoe producers, because “our designers have no imagination, and we consumers pay for it,” none of the other texts contained a single sentence lauding a neoliberal Russia, or recommending it as Russia's future.Footnote 118 Like the neoliberal model in general, the idea of Russia becoming a democratic state with the rule of law finds little resonance in Russian common sense. With the exception of Volobuev's textbook lamenting the lack of a Russian middle class a hundred years ago, and Aleksashkina observing that a law-governed state is one of Medvedev's objectives, the other texts surveyed here instead vindicate elite fears about habitual traditional Russian attitudes toward law and criminality.Footnote 119

The presence of corruption and criminality is just taken for granted. Pelevin, for example, has a character who grew up in Soviet Tatarstan, Nasykh (Kika) Nafikov, “in whose circle while growing up, nobody would use the words ‘buyer of stolen goods’ as an insult.” In Marinina's novel, Ministry of Internal Affairs Major Nikoali Golovin has a daughter Tamara, who is the hairdresser to the stars, including to Culture Minister Ekaterina Furtseva.Footnote 120 As a consequence, she gets gifts as tips. She meets a boyfriend, a tailor, who makes her a dress. Her father, accusing the tailor of “speculation” for making a dress at his own house, literally throws Tamara out of the house, onto the street, for wearing this “blackmarket” dress in his house. The book is littered with his tirades over chocolates, flowers, and other gifts that Tamara brings home. Marinina depicts him as ridiculous, that is, enforcing Soviet law is presented as absurd.Footnote 121 Meanwhile, Major Golovin's son-in-law, Rodik, also a cop, thought that his job of policing “crimes against socialist property” was silly; he should be tracking down “real” criminals, like murderers and robbers.Footnote 122 In other words, stealing from the state, just like President Medvedev feared, should not even be deemed a crime, thinks Rodik.

Finally, of ten articles in Today's Newspaper, three concerned corruption. Lednyeva's “Rightless Existence” informed readers that it cost 80,000 rubles to get your driver's license back once it was revoked, part of which went to pay off the judge. Drunk drivers paid off judges to get their licenses back, and those just driving on New Year's Eve could expect to pay 30,000 to any cop who happened to stop them, whether they have been drinking or not. This article was not a critique of any of these practices, but a handy practical guidebook for what the local corruption market costs. This was exactly the taken-for-grantedness of criminality that Medvedev would like to “drive out of Russian heads.”Footnote 123

Anna Merzliakov wrote a travelogue about her hitchhiking from Krasnoiarsk to Moscow. She was picked up by a truck driver, Slava. She asked about cops and bribes; he told her 500 rubles got you on your way again. Sure enough, they were stopped. Slava paid 400 rubles for a load that was somehow measured as 500 kilograms heavier than when he left that morning. Artem Mikhailov's article pointed out that despite the labor code, employers often fined their employees at work. At the end of the article, the author helpfully suggested that if this happened to you, you should contact the Inspectorate of Labor.

The four history textbooks offered a more mixed, somewhat more positive, assessment of the Soviet project than either Putin or Medvedev. While there were many differences in interpretation of particular historical events, it was accurate to say that the four texts shared some broad common evaluations. First, the Bolshevik project and its Stalinist successor were mostly disastrous. Second the period from 1953–85 was a complicated time with some pluses and some minuses. The Gorbachev years were a disaster. The Yeltsin years were mostly disastrous, but at least he had the good sense to appoint Putin in December 1999. Putin's reign has been an unblemished string of successes and correct decisions. There was not a single sentence in these four books that criticized Putin in any way. So, it was not Stalin who was whitewashed in history texts, but Putin. It should be noted that alone among all the sources of Russian common sense surveyed here, as well as elite neoliberal discourse, the textbooks maintained a Marxist-Leninist ontology, discussing events in terms of class relations, proletarian consciousness, national liberation movements, imperialism, and other Soviet commonplaces. This in itself produced a Soviet common sense about how to understand the world.Footnote 124

Pelevin's Macedonian Critique of French Thought is a relentlessly ironic critique of the Soviet Union. It is also the most elite of the texts under review, read more by members of the Russian middle class, intelligentsia, and elite than Marinina's more middle-brow and working-class novels. Pelevin's novel resonates most with Putin and Medvedev's consistent derogation of the Soviet experience. Indeed, Medvedev, asked what he reads in his free time, answered he kept Pelevin's latest works on his nightstand next to his bed.Footnote 125

Pelevin ironizes Russia's love-hate relationship with Europe. As his stand-in for “Russia” he creates the character of Kika, a Tatar, who criticizes French (European) philosophy from the standpoint of a (Russian) “ignoramus who never in his life has read these philosophers, but has only heard several citations and terms from their works.” Pelevin also offers a theory of how the Western victors in the Cold War will ultimately be defeated by the loser—the Soviet Union. The West, but the United States, in particular, will become infected by the same disease that afflicted the Soviet Union, “the aggressive military paranoia of their leaders.” Using good old Soviet jargon, Pelevin concludes that “the international financial plunderers (the United States and the West) have miscalculated—instead of sucking the blood out of Russia, they have sucked out the centuries-old poisonous rot which they now cannot digest.”Footnote 126 This “blood” of which Pelevin writes is the “Soviet afterlife.” As a child, Kika asked, “Where did the builders of developed socialism go? Where are they now, the happy builders of Magnitka, the virgin land tillers, the subjugators of the Gulag and the Arctic? Where have the millions of those who believed in communism in their souls gone after the closure of the Soviet project?”Footnote 127 Kika finds out that all these good Soviets have been turned into oil, just like “dinosaurs” of previous eras. “Here is revealed the mystery of the disappeared Soviet people … The life of a miner-Stakhanovite is ticking in a diamond Cartier watch or foaming in a bottle of Dom Perignon.” Others have gotten rich off of the thankless toil of Soviet workers.