In the last few decades some archaeologists’ scholarly understanding of the Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age (EBA) Avebury complex has set the traditional view of these monuments in disarray. Half of the complex has been written out of existence (see below) and an early preliminary suggestion from landscape phenomenology and archaeoastronomy (Sims Reference Sims2009a) to re-assess the issues was rejected (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013, 204). However, that early paper by the present author did not include a consideration of the West Kennet Palisades. This paper corrects that omission and finds, by an interdisciplinary integration of methods, that the Palisades reveal significant properties in their design and prescribed requirement of horizon views (Gaffney Reference Gaffney2021) that resolve these recent revisions to the Avebury monuments.

The traditional view of the Avebury monuments was set three centuries ago. William Stukeley (Stukeley 1743) described the Late Neolithic/EBA Avebury monuments as including the Beckhampton Avenue, Avebury Circle and Henge, West Kennet Avenue, Sanctuary stone circle, and Silbury Hill (Fig. 1). From excavations in 1931 and 1999 it has been found that, in addition to its stones, the Sanctuary simultaneously included nested circles of lintelled posts which did not support a roof (Cunnington Reference Cunnington1931; Pitts Reference Pitts2001; Pollard & Reynolds Reference Pollard and Reynolds2002, 106–10), and in 1987–92 (Whittle Reference Whittle1997) the discovery of the post enclosures of the West Kennet Palisades. However, over the last century much of this listing for the Avebury monuments has proved controversial to some leading archaeologists. For example, it is claimed that the Beckhampton Avenue did not continue beyond the Longstones Cove to its start at Fox Covert as claimed by Stukeley (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 109–11), that Silbury Hill is of an ‘inappropriate’ size as a Neolithic round mound (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013, 244), and that the West Kennet Palisades have been redated as Middle Neolithic structures and are therefore not part of the Late Neolithic/EBA monument complex (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Cartwright, Cook, Griffiths, Madgwick, Marshall, Reimer, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017).

Fig. 1. The Late Neolithic/Early Bronze Age monument complex in its landscape. Key: 1. Site of the West Kennet Palisade (see Fig. 2); 2. Silbury Hill; 3. Fox Covert; 4. Folly Hill; 5. Bray Street Bridge; 6. Avebury Henge and Circle; 7. Inner northern circle; 8. Inner southern circle; 9. West Kennet Avenue; 10. Break in West Kennet Avenue and site of North Kennet springs; 11. Waden Hill; 12. Sanctuary (adapted from Crocker 1820, in Mortimer 2003, 50–1)

Much of the details for these controversies hinge on interpretations made from single site excavation reports. But ‘… the avenues transformed a landscape of scattered monuments and significant places into a unified complex that was to be approached, read and understood in a very particular and prescribed way’ (Pollard & Reynolds Reference Pollard and Reynolds2002, 105). Rather than setting aside this property we will examine both the interpretations from the excavation reports and add to them the properties that emerge from landscape phenomenology and archaeoastronomy. By the interdisciplinary integration of these three methodologies we would expect properties to emerge at a higher scale of meaning than those that might emerge from a single methodology, such as site excavation. If found, any possible systemic meanings would then recursively provide the context for each single structure in the Avebury monument complex.

RECENT CONTROVERSIES AT THE AVEBURY MONUMENT COMPLEX

The Beckhampton Avenue

Opinion is divided within archaeology over what are the prescribed avenue routes through the Avebury monuments. Those who previously rejected the existence of Beckhampton Avenue had to reverse their view once it was excavated in 1999 ‘exactly where he [Stukeley] had identified it’ (Gillings & Pollard Reference Gillings and Pollard2004, 19). Nevertheless, it is currently understood by some (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 118) to extend only to the earlier site of the Longstones Enclosure/Cove and not beyond to Fox Covert. This view is based on a geophysics survey and 50 × 40 m excavation trench which found no evidence of stones or stone-holes south-west of the Longstones. According to the excavators this provides ‘conclusive proof that the avenue did not continue in its known form beyond the Longstones Cove’ (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 71). But if these Avenues did not have a standardised form then this is not ‘conclusive proof’ of much at all. Indeed, in 2003 a similar sized trench was dug along a previously unexplored section of the West Kennet Avenue in a roughly symmetrical location to that of the Longstones Cove. Here also no trace of the West Kennet Avenue was found (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 139). The authors conclude that ‘… the assumption of an unbroken line of stone pairs may not hold for the full length of both avenues’ (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 109). Since the West Kennet Avenue is known to extend beyond this gap to the Sanctuary, another 700 m to the east, then it is equally likely that the break in continuity along the Beckhampton Avenue is also a change in its form which then extends onwards to Fox Covert. In all, 24 reasons have been noted for accepting Stukeley’s understanding of the Beckhampton Avenue (Sims Reference Sims2009b; see also North Reference North1996, 262–4).

Silbury Hill

Leary (Reference Leary, Leary, Darvill and Field2010) and Leary et al. (Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013) report on rescue archaeology undertaken within the collapsed tunnels of Silbury Hill consequent from earlier archaeological failures to backfill them. By Bayesian modelling they found a date for completion of the Hill ‘… in the late 24th or early 23rd centuries cal bc’ (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013, 111). An extremely detailed picture emerges from these reports of at least 16 phases to the construction process of the hill. However, the model used to understand these important details makes a divide between the small, internal 5 m high organic mound and the external form of the over 30 m high flat topped truncated chalk cone around and above this internal low mound. The construction process model focuses on their materiality of the many interleaved layers that make up the small internal mound, the collective experience and memories of making it, and the landscape context of the hill’s location. But in its emphasis on the informal labour process of construction, most of which is opaque to the archaeological record, this model sets aside the possible prescribed ritual behaviour which may be revealed by the form and content of the monument complex. Instead, the model’s interpretation is categorically set against any formal model: ‘… there was no pre-existing concept for the final form of Silbury Hill in the heads of the builders’ (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013, 205). Beyond ‘the Upper Organic Mound which might be considered an appropriate sized structure for the everyday British Neolithic, just what was it that provided the catalyst to resume construction on such a huge scale?…[W]e can find no practical planned purpose for continuing to build such a monumental mound…’ (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013, 244). Instead of being faced with an ‘inappropriate’ or ‘purposeless’ largest prehistoric mound in Europe, the current paper assumes the unity of form and content, which is the basis of all thought, in which the internal content is the pre-condition for the external form. We will proceed by interrogating the form of Silbury Hill and the Avebury monument complex in its landscape and find that this procedure provides the key to understanding the internal properties and material relationships within Silbury Hill which are so carefully documented in these later reports.

The West Kennet Palisades

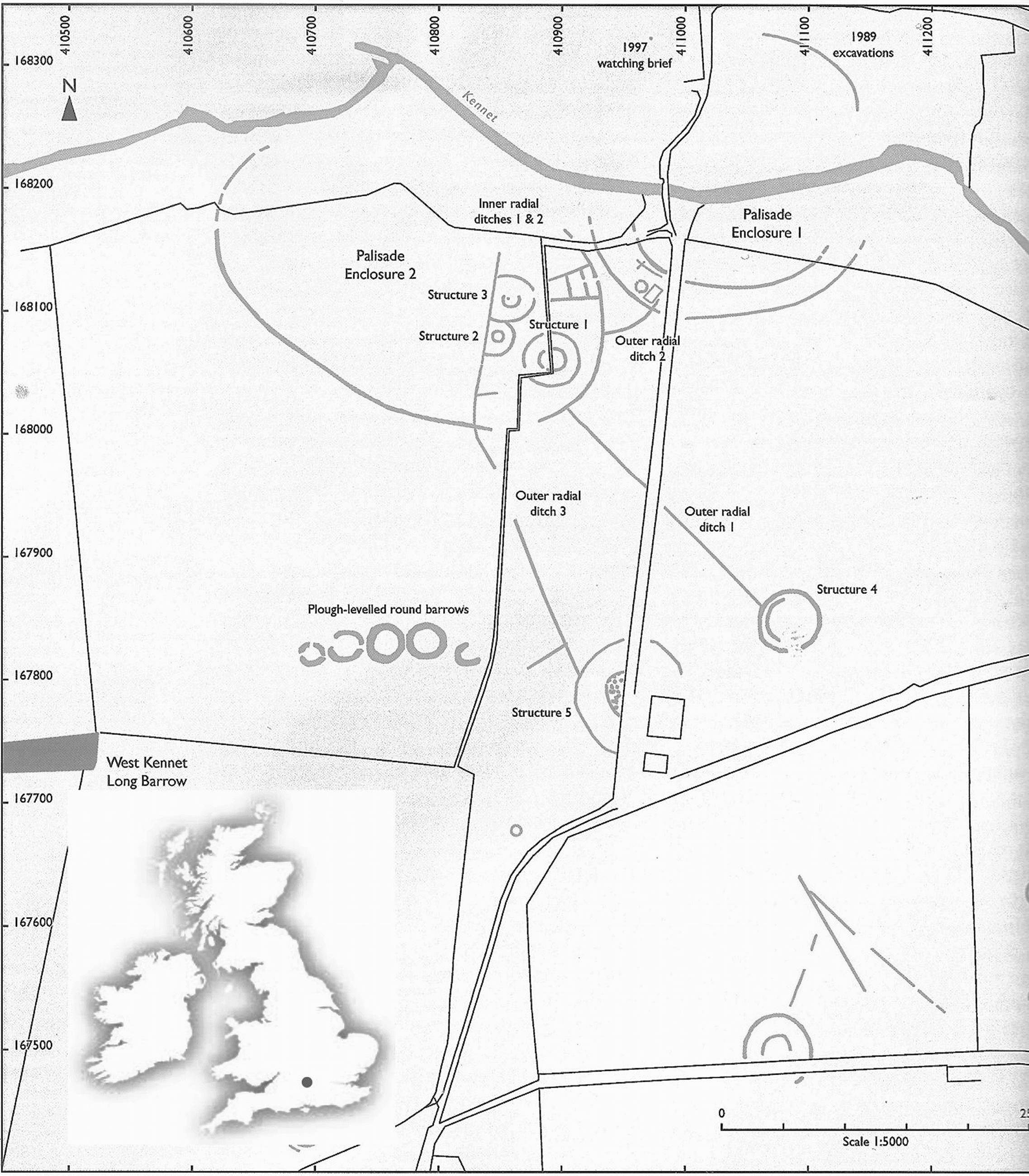

The West Kennet Palisades were two large timber-fenced enclosures, labelled by Whittle as Enclosures 1 and 2, linked by the connecting fence, outer radial ditch 2, and two other outer radial fences, 1 and 3, connecting Enclosure 2 to two outlying smaller timber enclosures called Structures 4 and 5 (Fig. 2; Whittle Reference Whittle1997). They were located on flat land close to the southern end of Waden Hill, matching the Avebury circle and henge’s location close to the northern end of Waden Hill (Fig. 1). Within a kilometre west of the Palisades was Silbury Hill and 700 m east was the Sanctuary, and the Palisades were linked to both the Avebury circle and the Sanctuary by the West Kennet Avenue (Fig. 1 and below; Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008; Sims Reference Sims2009b). By these arrangements and by excavation findings Whittle concluded a Late Neolithic/EBA date for their construction (Whittle Reference Whittle1997). However, in 2017, a Historic England (HE) restudy of some of the materials from Whittle’s excavations came up with the surprising redating for the West Kennet Palisades of about 3320 cal bc (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Cartwright, Cook, Griffiths, Madgwick, Marshall, Reimer, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017; Pitts Reference Pitts2017).

Fig. 2. West Kennet Palisades. During excavation all ‘ditches’ revealed they once contained closely spaced posts. Hence what for the excavators were ‘ditches’ were originally palisade fences (adapted from Barber Reference Barber2003, fig. 12)

The redating is based on the Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) dating of 21 pieces of charcoal of oak sapwood analysed using Bayesian statistics, and the re-analysis exercise was prompted by the unusual spread of the original radiocarbon dates found by Whittle. While Whittle’s excavation showed a uniform Grooved Ware and flintwork material culture indicating dates of 2600–2200 cal bc, his own radiocarbon dates showed an 800 year dating range to bones found in the outer ditch of Enclosure 1. Returning to the collection, the HE team had selected 25 red deer and pig bones and antler picks and 24 pieces of charcoal found by Whittle in the two enclosures. The bone and antler dates all confirmed the Late Neolithic/EBA dates indicated by the material culture; three pieces of charcoal from oak sapwood gave dates from 1200–1100 cal bc, and the 21 remaining pieces of charcoal provided 3325–3215 cal bc dates for both Enclosures. The HE team set aside all the later dates and suggested that these early dates came from the oak Palisade now re-assigned to the Middle rather than Late Neolithic, and that all the later material culture found there – the bone, antler, and pottery dated to about 2400 cal bc – attested to a separate, later ‘Grooved Ware settlement’ (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Cartwright, Cook, Griffiths, Madgwick, Marshall, Reimer, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017, 260–3).

The choice of using AMS dating of some of the charcoal alone ignores a number of issues. Brophy and Noble (Reference Brophy, Noble and Gibson2012, 23–6) have pointed out from evidence at Forteviot in Scotland and elsewhere the danger of attributing monument dates from charcoal radiocarbon dates alone, since some sites have a highly variable date range covering a millennium or more. Further, Whittle presented many examples of pig bones and Grooved Ware potsherds which had been deposited alongside the oak posts, often at 2 m below the surface, which ‘must be contemporary with construction’ (Whittle Reference Whittle1997, 116–17). In numerous examples he shows how both bones and potsherds were placed upright touching the sides of the posts ‘well down’ (Whittle Reference Whittle1997, esp. 63, and 61, 62, 66, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85). According to Bayliss ‘… the artefacts fell into the soft charcoal-rich sediments and voids of the post-pipes from overlying Grooved Ware occupation in the area of the enclosures’ (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Cartwright, Cook, Griffiths, Madgwick, Marshall, Reimer, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017, 261). If bones, antlers, and sherds all sank 2 m underground from an EBA settlement surface 800 years after a mid-Neolithic palisade then we would expect much to be abraded and mostly in the backfill, some in the post-pipe, and a very few if any to be found upright and touching the sides of the post-pipes. Instead, the pottery was found in a fresh condition, none in the backfill, some in the post-pipes and frequently 2 m below the surface leaning against the edge of the post-pipes (Whittle Reference Whittle1997, 116). This is the reverse distribution to that expected by Bayliss (see also Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Gillings, Chan, Cleal, French, Allen, Banfield, Pike, Carle, Eve, Rowland, Thompson, Clifton and Snashall2019, 9).

The dates given by Bayliss for eight other English and Welsh palisades all span from about 2700 cal bc for Hindwell, Radnorshire, to about 2300 cal bc for Marne Barracks, North Yorkshire. Instead of a typology that places the West Kennet Palisades alongside the near identical Hindwell enclosure (see below), the new date of c. 3320 cal bc places the Palisades a few centuries after the earlier and different Avebury monumental structures of Windmill Hill causewayed enclosure and the West Kennet long mound and contemporaneous with cursus construction, with no contemporaneous or immediately posterior parallels (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Cartwright, Cook, Griffiths, Madgwick, Marshall, Reimer, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017, 264–6, 268). This typological misfit is avoided if we consider the alternative explanation that the Late Neolithic Palisade activity has become churned with earlier Middle Neolithic activity, which included burning episodes separate to and preceding that of the Palisades (Pitts Reference Pitts2017; Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Gillings, Chan, Cleal, French, Allen, Banfield, Pike, Carle, Eve, Rowland, Thompson, Clifton and Snashall2019, 8–9). These new dates do not solve the earlier wide dispersion of 800 years found by Whittle but now compound it with a revised dating range of about 2120 years.

The ongoing (Covid-delayed) restudy of the Palisades will include new dating information (Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Gillings, Chan, Cleal, French, Allen, Banfield, Pike, Carle, Eve, Rowland, Thompson, Clifton and Snashall2019) and harbours similar reservations as these towards the HE dating study. The Living with Monuments team have shown that dates from oak charcoal are not consistent with dates from bone and antlers in the same primary contexts. Table 1 shows that from the same contexts where Bayliss et al. found charcoal dated to the Middle Neolithic came bone and antler, all dated to about 2400 cal bc – ie, in the Late Neolithic/EBA: ‘It is these dates that must provide the chronology for construction of the palisades’ (Pollard et al. Reference Pollard, Gillings, Chan, Cleal, French, Allen, Banfield, Pike, Carle, Eve, Rowland, Thompson, Clifton and Snashall2019, 9 & appx 5). These considerations suggest that all the dates found are possibly correct and refer to an overlay of Neolithic and Bronze Age activity in this area spanning two millennia, consistent with similar findings elsewhere.

TABLE 1. DATES OF ANIMAL BONES AND ANTLERS FOUND IN THE SAME CONTEXT AND PACKING MATERIAL AS OAK CHARCOAL, DATED TO THE MIDDLE NEOLITHIC BY BAYLISS et al. (Reference Bayliss, Cartwright, Cook, Griffiths, Madgwick, Marshall, Reimer, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017)

Adapted from Pollard et al. (Reference Pollard, Gillings, Chan, Cleal, French, Allen, Banfield, Pike, Carle, Eve, Rowland, Thompson, Clifton and Snashall2019, appx 5)

Both groups of radiocarbon dates from Whittle and HE, for both Enclosures 1 and 2, are identical (Bayliss et al. Reference Bayliss, Cartwright, Cook, Griffiths, Madgwick, Marshall, Reimer, Bickle, Cummings, Hofmann and Pollard2017, fig. 17.5 & 266), both enclosures share the same construction techniques and Outer Radial 2 (Fig. 2) connects both enclosures. These properties suggest the two enclosures were contemporaneous. Further if one enclosure replaced the other this would not explain why they differ from each other. For much of its circuit Enclosure 1 has a doubled nested concentric sub-circular palisade while Enclosure 2 has a single circuit oval palisade. By these properties alone they suggest they serve different but interlinked functions that do not support the notion that each could replace the other. This inference is supported at Hindwell palisade enclosure, dated to c. 2800 cal bc, which is almost identical to the West Kennet Palisades (Jones Reference Jones2014). Each part of the Hindwell enclosure clearly relies on the other, suggesting the same condition applies to the near identical West Kennet Palisades. By these criteria, the West Kennet Palisades are little different from other Late Neolithic/EBA palisades.

These considerations bring all the components of the Avebury monuments: Avenues, Avebury Circle and Henge, Sanctuary, West Kennet Palisades, and Silbury Hill, into a single complex built between 2600 cal bc and 2200 cal bc (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 204). This is as predicted by Parker Pearson’s materiality model in which the materiality of stone and wood act as metaphors for the dead and the living, all in the service of funeral rites of passage from the living to the dead (Parker Pearson Reference Parker Pearson2012). If we, like the materiality model, are in error in accepting a Fox Covert start and Silbury Hill and the West Kennet Palisades as all being part of the Late Neolithic/EBA monument complex, then an interdisciplinary exercise including landscape phenomenology and archaeoastronomy should find that the monument complex exhibited no new emergent properties.

QUANTIFIED LANDSCAPE PHENOMENOLOGY

Landscape phenomenology draws upon the embodied experience of walking the prescribed routeways through a monument complex. Processing along Beckhampton Avenue from Fox Covert and then through Avebury Circle, along the West Kennet Avenue to the Sanctuary, and then to the West Kennet Palisades (Fig. 1) will select and disallow certain views and impressions. These experiences might suggest the possible motivations of the builders and hence possible meaning of the monuments. But the Late Neolithic/EBA Avebury monuments are a paradox. They are dispersed in a landscape divided by two hills – Folly Hill and Waden Hill (Fig. 1). This means that for nearly 80% of the routes prescribed by the Beckhampton and West Kennet Avenues there can be no mutual intervisibility between them, or any sight of the Avebury Circle, the Sanctuary, West Kennet Palisades, or Silbury Hill. This could have been avoided if the builders had chosen for their monument complex the flat open landscape immediately north of the Avebury Circle alongside the Early Neolithic causewayed enclosure of Windmill Hill. But taking just the one route specified by the two avenues would open us up to looking for those properties that confirm our own assumptions for their choice. Following a suggestion made by Thomas (Reference Thomas1999, 217), we can guard against this by exploring all other possible routes within the locality. This method was extended by a rigorous search for alternative meanings by positing a proxy population of other possible Avebury monument complexes that could have been built in the immediate neighbourhood. This enabled the isolating of what portfolio of properties was offered by the chosen site compared to those alternative sites available nearby. Minimally, the local landscape allows adding four possible additional avenues, alternative northern sites for both Silbury Hill and the Sanctuary, while holding the Avebury Circle as constant to all possible models (Fig. 3). Each possible complex would be composed of a pair of avenues from the now available six possibilities, with each radiating from two of the four entrances/exits of Avebury Circle, so allowing 15 possible avenue combinations. Secondly, another 15 combinations would be available if Silbury Hill and the Sanctuary were relocated within the open landscape north of Avebury Circle, so generating a total proxy population of 30 possible Avebury monument complexes. By fieldwalking along the actual and possible routes, a quantitative record can be made of what can be observed and experienced.

Fig. 3. Avebury complex with schematic avenues, including other possible avenues and alternative location for Silbury Hill. Key: 1. Avenue ‘starting’ at alternative northern location for Silbury Hill (black circle) and ‘ending’ at northern entrance of Avebury Henge; 2. Avenue ‘ending’ at eastern entrance to Avebury Henge; 3. West Kennet Avenue ‘ending’ at Sanctuary; 4. Avenue ‘starting’ at Silbury Hill and ‘ending’ at western entrance to Avebury Henge; 5. Beckhampton Avenue ‘starting’ at Fox Covert and ‘ending’ at western entrance to Avebury Henge; 6. Avenue ‘starting’ in west-north-west and ‘ending’ at western entrance of Avebury Henge (adapted from Powell et al. Reference Powell, Allen and Barnes1996)

We can compare the properties of each possible pairing of avenues against those exhibited by the actual chosen avenues: number 3:5 in Figure 3. From fieldwalking, only avenue combinations 1:2, 1:6, and 2:6 (Fig. 3), with Silbury Hill situated to the north of Avebury Circle, allow any possibility of intervisibility between both avenues and the Avebury Circle, Sanctuary, and Silbury Hill. All other possible combinations do not allow intervisibility between the Avebury Circle and the Sanctuary but do allow intervisibility from each and Beckhampton Avenue to Silbury Hill. Therefore, the monument builders did not require intervisibility between all the monuments but did require some view of SilburyHill from each.

Turning to avenue 1, with Silbury Hill in the north, and avenue 4 with Silbury Hill in its actual southern location, we see that both lead directly to Silbury Hill. They offer uninterrupted views of Silbury Hill in which its apparent size grows for an observer approaching it along these routes. With the builder’s choice of avenues 3:5 we can see that their skirting route around the Avebury monuments keeps Silbury Hill at a roughly constant distance in which its apparent size remains unchanged. Therefore, the builders did not want the analogue views of Silbury Hill offered by avenues 1 and 4. Yet avenue combination 2:6 also keeps a skirting distance from a Silbury Hill in the north, but here on a flat featureless plain it is in stark contrast to the actual chosen routes of the Beckhampton and West Kennet Avenues. Unlike in any other combination of monument configuration avenues 3:5, which travel around the backs of Folly and Waden Hills, offer a maximum number of on/off views of Silbury Hill (see Sims Reference Sims2009a for full treatment). Therefore, by the builder’s choice of monument complex location and avenue route we can reduce this part of the interpretive narrative down to a single characterisation – the builders required skirting digital on/off views of Silbury Hill of a certain number and not analogue views. To consider what were these views we first need to summarise some of the other prescribed horizon views in the Avebury monument complex.

LUNAR-SOLAR ALIGNMENTS OF THE AVEBURY MONUMENT COMPLEX

We can now turn to the archaeoastronomy of the Avebury monuments.

Avebury Henge and Circles

The external bank and internal ditch of the Avebury Henge, has an ‘overall calibrated range span[ning] 2840–2460 cal bc, but is weighted towards the 26th century bc’ (Pollard & Cleal Reference Pollard, Cleal, Cleal and Pollard2004, 121). The outer circle of 98–100 megaliths inside the ditch enclosed two smaller northern and southern megalithic circles (Smith Reference Smith1965, 205). In addition, a post circle is offset to the north-east of the northern inner circle (Ucko et al. Reference Ucko, Hunter, Clark and David1991, 227) and a supernumerary Ringstone offset to the south-west of the southern inner circle. Following the method of landscape archaeology in view-shed analysis (Exon et al. Reference Exon, Gaffney, Woodward and Yorston2000) and viewing clockwise from the outer stones in the lowered east, south, and west sections of the outer circle, these four central features coincide with alignments on a sharp horizon (Fig. 4; North Reference North1996, 271–6; Sims Reference Sims2007; Reference Sims and Campion2010; Reference Sims2016b; Reference Sims2019 Fisher & Sims Reference Fisher and Sims2017). Standing by stone 64 in the north-east of the outer circle and looking south-west and uphill as a tangent to the post circle and into the Cove at winter solstice the Sun can be seen setting through the southern corner gap of the Cove at the centre of the northern inner circle. Walking slowly uphill towards the Cove the rising eye of the observer counterbalances the descent of the setting Sun, so apparently holding it stationary for about 7 minutes. The same arrangement pertains at Stonehenge from the Heel Stone (North Reference North1996). Moving back to the outer stones and looking uphill from stone 78 towards the southern side of the oval southern inner circle (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Barker, Pollard, Strutt and Taylor2017) and continuing towards the Ringstone there is an alignment on the southern major standstill of the Moon. This is to the south-west and almost parallel to the alignment on the winter solstice sunset. For a period of about 2 years every 18–19 years the Moon returns to this horizon limit every 27.3 days – the cycle length of the sidereal Moon (Fisher & Sims Reference Fisher and Sims2017; Sims Reference Sims2019).

Fig. 4. The chief internal astronomical alignments in the Avebury Circles. Key: M – Moon; S – Sun; U V W – timber circles (adapted from North Reference North1996, 274)

By combining the solar alignment to the south-west with the lunar alignment also to the south-west, then in their conflation the Sun illuminates the far side of the Moon and the Moon is dark to earthly observation. This celestial arrangement will therefore coincide with the start of the longest, darkest night – winter solstice sunset at dark Moon. A similar arrangement pertains at Stonehenge, but there conflates winter solstice sunset with the southern minor standstill moonsets, which occurs 9–10 years before or after the major standstill of the Moon (Sims Reference Sims2006; Reference Sims2016a). Moving clockwise to the south from stone 94 of the outer circle a ray over the Obelisk and extending tangentially past the northern inner circle sees the summer solstice Sun setting into Windmill Hill, and from the west of the outer circle at stone 21 an alignment through the Cove and tangential to the post circle sees the rising northern major standstill of the Moon. All these alignments are found in many monuments of the period (North Reference North1996; Ruggles Reference Ruggles1999) and at Avebury none of these intersect with Silbury Hill.

West Kennet Avenue

The prescribed exit from the Avebury Circle is by the southern entrance onto the West Kennet Avenue (Fig. 1) dated, like Beckhampton Avenue, to c. 2600–2000 bc (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 202–4). From Keiller’s reconstruction of the northern section of the West Kennet Avenue (Smith Reference Smith1965) nearly 37 paired stones, or their concrete markers, mark the route. Out of 362 possible pairings 145 lunar, solar, and cardinal alignments to adjacent, opposite, and diagonal stones have been found – well beyond any chance event (North Reference North1996, 248–62; Sims Reference Sims, Silva and Campion2015b; see also Sims Reference Sims2013b; Reference Sims, Pimenta, Ribeiro, Silva, Campion, Joaqunito and Tirapicos2015a; Reference Sims, Rappenglück and Shaltout2021). When walking just outside the West Kennet Avenue it can be seen that most of the heights of the opposite stones were chosen to coincide with the height of the background horizon (Sims Reference Sims, Silva and Campion2015b, fig. 5.2). This allowed the artifice of seeing these solstice Suns, standstill Moons, or cardinal horizon events descending into or rising out of the tops of all the stones. For those walking within the Avenue this suggested, by their agency, that they followed a route through the underworld. And since both settings and risings were prescribed by these alignments, then this required moving in both directions along the line of the Avenue – either towards the Avebury Circle or towards the Sanctuary and the West Kennet Palisades – for both major and minor standstills and the solstices.

The route of this section of the West Kennet Avenue has been selected to combine high horizons to the west of about 7º altitude with low horizons to the east of about 2º. Since at this latitude a 1º increase in altitude reduces the horizon azimuth of any transiting celestial object by about 2º, then this 5º difference in horizon gearing reduces azimuth differences between adjacent and opposite horizon transiting sky objects by about 10º. At this latitude this is the horizon difference between any solstice alignment and the adjacent minor and major standstills alignments (Fig. 5). Therefore, this route would have allowed the builders to counterpose the setting winter solstice Sun in the south-west exactly opposite the rising northern major or minor standstill Moons in the north-east. Such horizon gearing would have made it possible to prescribe a vista of full Moons emerging from the tops of the eastern line of stones. In fact, by manipulating the orientation of the Avenue sections and the placement of each stone such a combination was chosen only for stone pair 15 (Sims Reference Sims, Silva and Campion2015b). Fifteen pairs south of this full Moon position, stone pair 30 never had a stone placed on the west side of the Avenue at position 30b. In this third example of a discontinuous form along the avenues, and since the lunar synodic month alternates between 29 and 30 days, then to find this gap allows us to infer that vacant position 30b, 15 stone ‘pairs’ after pair 15, coincides with the day of the 29.5 dark Moon part of the synodic month. This inference is emphasised by the great mass of flint tools and flint debitage found at this stoneless position 30b compared to the one small sherd of Grooved Ware found at stone 15b (Smith Reference Smith1965, figs 73 & 232). Reversing the sequence back 15 pairs from 15b to the southern entrance into the Avebury henge therefore brings us back to another dark Moon position at the start of the Avenue which is also the entrance to the Avebury Circle. This doubly confirms the earlier finding from of the archaeoastronomy of the Avebury Circle’s alignments, but now with the number of days of the synodic month instead of the sidereal cycle of lunar alignments, that the Avebury Circle is a place for a dark Moon ritual.

Fig. 5. Standardised azimuths of lunar standstills and Sun’s solstices at Latitude 51º 26´ North for 2500 bc compared to azimuths of prescribed views of Silbury Hill’s top terrace around the Avebury monument complex. Key: Solid arrowed lines: standardised azimuths from above and below west–east line, assuming zero horizon altitude; horizon alignment on upper limb of Sun and Moon; there is no single point estimate for any lunar standstill, since each varies by about ±1º.5 (Fisher & Sims Reference Fisher and Sims2017); every lunar standstill exhibits this small variation in observably different ways from every other standstill (Sims Reference Sims2019) (adapted from North Reference North1996, appx 3): Dashed bold lines: azimuths of prescribed views of Silbury Hill’s top terrace around the Avebury complex

The Sanctuary

The Sanctuary, as first suggested by the excavator (Cunnington Reference Cunnington1931; see also Pollard Reference Pollard2014), was a single phase unroofed nested and interleaved set of circles of megaliths and lintelled posts at the end of the West Kennet Avenue, dated to about 2500 bc (Pollard Reference Pollard2014). In the uphill Avenue approach, it appeared as a ‘solid wall’ of stones and posts (Pitts Reference Pitts2000, 239; Sims Reference Sims, Henty and Brown2020, fig. 6.2). When viewing from the outer circle of stones a lower window at an altitude of about 1.5º and an upper window at about 6.5º altitude presented themselves within this ‘wall’. As along the northern section of the West Kennet Avenue again, by this gearing of 5º altitude difference, two apertures to the sky were opened which brought together winter solstice sunrise in the lower window directly beneath the southern minor standstill moonrises in the upper window. Without this difference in altitude, they would be 10º apart on a level horizon. The same double window feature appears within all four cruciform inter-cardinal corridors through the Sanctuary. Summer solstice sunrises and sunsets are combined with the northern major standstills in the two northern quadrants and winter solstice sunrises and sunsets are combined with the southern minor standstills in the two southern quadrants (Fig. 5 and Sims Reference Sims, Henty and Brown2020). As at the Avebury Circle, by conflating solstice Suns on the same azimuth with a lunar standstill for all four quadrants, together by geared altitudes they each combine when the Moon is dark. Further, since the Avebury Circle has its axial alignment on the major standstill of the Moon and, we will find below, the West Kennet Palisade are aligned to the minor standstill of the Moon, then since the stone and timber Sanctuary has alignments on both the major and minor standstills, like the West Kennet Avenue, it also mediates between and prescribes movement to both the stone Avebury Circle and the timber West Kennet Palisades.

EMERGENT PROPERTIES FROM INTEGRATING LANDSCAPE PHENOMENOLOGY AND ARCHAEOASTRONOMY AT THE AVEBURY MONUMENT COMPLEX

Figure 5 shows the standardised sea-level azimuths of the solstices and minor and major standstills of the Moon at the Avebury latitude of 51° 26' – very roughly 30–40–50° above and below the west–east line. From Figure 5 we can see that the azimuths of the sight lines towards Silbury Hill prescribed by the Avebury monuments do not coincide with any of the solstice or standstill azimuths that we have found. Nevertheless, we now have three aspects to the horizon views of Silbury Hill at Avebury which we can examine for what emergent properties arise in their combination: azimuth, elevation with respect to the background horizon, and ‘astronomy’.

We start from the finding that the Avebury Circle by alignment and the West Kennet Avenue by monthly lunar phases both specified a dark Moon ritual at winter solstice sunset at the Avebury Circle and this within a cosmology of a geocentric stationary planar Earth (Witzel Reference Witzel2012, 77–8). Minimally, this cosmology would include that the above world of the sky sandwiched this ‘flat’ Earth between it and the underworld.

After this long preparation of the data we are now ready to interpret the views of Silbury Hill prescribed by the Avebury monument complex. From Fox Covert (Fig. 6A) the first sighting of Silbury Hill is of its chalk top terrace just proud of the eastern horizon (5º south of east) and from the Sanctuary the last sighting before the West Kennet Palisades is of its flat top in line with the western horizon above its chalk terrace (16º north of west; Fig. 6D). Within this cosmology this means that if Silbury Hill is being symbolically constructed as either the Sun or the Moon, then as long as this direction of underworld travel is consistent across all the four prescribed views we have found, it must have travelled through the underworld from east to west. But since the Sun always sets in the west and rises in the east, this rules out Silbury Hill top terrace as a facsimile of the Sun. However, it is consistent with the Moon’s apparent behaviour, since waning crescent Moon is always observed on, and only on, the eastern horizon just before sunrise, which is then followed by 3 days of dark Moon, after which waxing crescent Moon is next seen setting on, and only on, the western horizon just after sunset. Therefore, within this cosmology the crescent Moons are understood to travel through the underworld from east to west, not west to east as in ours, and only during the period surrounding and including dark Moon. Processing from Fox Covert towards the Avebury Circle dark Moon winter solstice sunset ritual is therefore consistent with first seeing the top chalk terrace of Silbury Hill just proud of the horizon at 5º south of east as waning crescent Moon. To repeat, this only occurs before dark Moon. Notice that the lunar properties that we are now dealing with draw upon the lunar phases of the synodic 29.5 day month and not the sidereal 27.3 day cycle of lunar standstill alignments. If this inference is valid then we would expect the three other prescribed views of Silbury Hill up to and including the Sanctuary to provide representations of the Moon’s phases in a strict sequence through dark Moon culminating in and concluding with waxing crescent Moon.

Fig. 6. Views of Silbury Hill in clockwise rotating order from: A. Fox Covert; B. Briar Street Bridge; C. centre of Southern Inner Circle of the Avebury Henge; and D. the Sanctuary

The next prescribed view of Silbury Hill in this skirting clockwise route is from the present Bray Street Bridge over the River Winterbourne. Here it is seen at 77º south of east and therefore continues its clockwise movement from east to west, but its flat top is now level with the background horizon (Fig. 6.B). At this latitude the Moon’s maximum horizon azimuth to the south is never beyond 54º south of east or west (Fig. 5). There could not be a more dramatic signifier of Silbury Hill as the Moon having now set and moving westwards through the underworld. And for those within the habitus of a lunar-solar ‘flat earth’ cosmology the realisation of seeing the Moon in the underworld, by their agency alone, they must conclude that they also are now in the underworld. This is doubly confirmed by the circumstance of just having crossed a river – a universal mythic boundary between worlds (Witzel Reference Witzel2012, 77–8).

Once moving on and into the southern inner circle square feature of the Avebury Circle (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Barker, Pollard, Strutt and Taylor2017) we see the top terrace of Silbury Hill just proud of the north-western horizon edge of Waden Hill at 80º south of west. This is a further 23º shift to the west and again consistent with the Moon’s apparent underworld travel westwards not eastwards. Here again, we see the top terrace beyond the maximum horizon azimuth of 54º south of west for earthly observation of the Moon. To see the Moon at this azimuth in the south-south-west can only be interpreted that this is sight of the waxing crescent Moon in the underworld continuing its travel westwards through the underworld before its eventual emergence just above the western horizon as waxing crescent Moon. The Avebury Circle must therefore itself be a place of the underworld providing sight of events like this Silbury Hill-as-Moon during its underworld travel. This is consistent with what was previously indicated when crossing the River Winterbourne and with what was seen at Fox Covert.

At the Sanctuary we see Silbury Hill’s flat top in line with the background horizon at 16º north of west. Again, this is another westward shift in azimuth of 96º from the Avebury Circle’s southern inner circle, confirming a consistent westwards aspect to all four of Silbury Hill’s so far prescribed views. For its flat top to be in line with the background horizon also indicates that it represents the Moon still in the underworld but now under the western horizon and therefore just prior to its emergence out of the underworld as waxing crescent Moon. We have therefore found that these four prescribed views of the Silbury Hill top terrace are consistent with the scrolling lunar phases before and during dark Moon as would be understood within a lunar-solar ‘flat’ geocentric stationary Earth cosmology. Participants in such a habitus and witnessing these views could only conclude that they also were accompanying the Moon in its underworld travel. Just beyond the Sanctuary this clockwise circuit around the monument complex brings us to a fifth prescribed horizon view of Silbury Hill from Enclosure 2 of the West Kennet Palisades.

THE WEST KENNET PALISADES

Fieldwork visits to Avebury over two decades collected much of the data with the aid of a Suunto compass and clinometer, both accurate to half a degree. This was cross-checked in the field both by reverse measuring magnetic alignments and by the author’s sightings being repeated and checked in the field by post-graduate students. All azimuth values in the field were collected from northings and adjusted to allow for magnetic variation at the time of their collection. This method was appropriate when viewing Silbury Hill and mapping the Beckhampton Avenue, Avebury Circle, and West Kennet Avenue since enough of them remain to measure the azimuth and altitude of prescribed views. However, since this is not the case for either the Sanctuary (Sims Reference Sims, Henty and Brown2020) or the West Kennet Palisades, for which there are few surface remains, other measures had to be made. By careful integration of site plans and Ordnance Survey measurements desk-based checking allowed higher fidelity measurements than those possible in the field with a compass and clinometer. It was expected that this would be necessary so as to discriminate between the type of horizon views afforded by the variable design features of the West Kennet Palisades. Independent of this procedure a linked doctoral project was initiated to build a VRM of the Avebury monument complex by integrating digitised OS data and monument site plans with a working astronomy model of the sky (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2006). The convergent results between these two methodologies were gratifying and point towards the future need for a greater engagement with this technique (Zotti et al. Reference Zotti, Hoffman and Wolf2021).

Both Whittle and Thomas suggest that the architecture of the West Kennet Palisades structures movement and ritual progression through nested concentric enclosures with heavily prescribed views of associated monuments (Whittle Reference Whittle1997, 164; Thomas Reference Thomas1999, 217–20). Using a multiplier of 3.5 to post-hole depth Whittle estimated that the height of the closely butted palisades would have been 7 m for the outer circuits of both Enclosures 1 and 2 and Outer radial ditch 2, whereas the palisades of Outer radial ditches 1 and 3 would have been about 3 m high. In the expectation that errors in either estimate would be equally distributed across both, this would not affect their ratios and so not contribute further errors in the estimated altitudes of each palisade. There was no dwelling or occupation evidence inside either enclosure, being largely empty clean spaces, suggesting to Whittle that they had a ritual purpose.

First we consider the Palisades as a separate structure from the Avebury complex. Enclosure 2 was approached from the south east from post circles Structures 4 and 5 between the connecting Palisades of Outer Radials 1 and 3 (Whittle Reference Whittle1997, 157, 164; Barber Reference Barber2003, 21–33; Fig. 2). The converging timber fences of the 3 m high funnelling facade, when walking northwards from Structures 4 and 5 towards Enclosure 2, cuts off seeing much of the open landscape (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013, 182) to the west and the east. Simultaneously, for an adult Neolithic man with eye height of 1.65 m (Brothwell & Blake Reference Brothwell and Blake1965) the 7 m high palisade of Enclosure 2 will, after continuing about 30 m, cut off viewing all landscape to the north and north-west. From either the centre or the edge of Structure 5 the orientation to the summit centre of Silbury Hill is at an azimuth of about 38º north of west (see below). Since Silbury Hill’s flat summit is at an altitude of 1º.7, and at this latitude of 51º 26´ north every degree of altitude reduces the sea level azimuth by 2°, then the standardised sea level azimuth of this alignment becomes 41º.4 north of west. For 2250 bc at this latitude the alignment on summer solstice sunset is 41º.8 (North Reference North1996, 571) and this should mean that, since the unaided human eye can detect no difference in the Sun’s horizon position 3 days before and 3 days after the actual solstice, Structure 5 is in position to observe the week of summer solstice Suns setting into the Silbury Hill summit. However, Figure 7 shows that the builders placed Structure 5 behind a hill salient which, setting an intervening horizon of 1º.9, interrupts any direct view of Silbury Hill and of the summer solstice Suns setting into its summit. This is an unexpected finding.

Fig. 7. Transect from Structure 5 to Silbury Hill Summit, with sightline showing interrupted view by the nearby hill salient (Google Earth Pro)

According to an archaeoastronomy model which assumes observational astronomy from alignments, it makes little sense to place an ‘observatory’ behind a hill which obstructs the target horizon. However, the ‘ontological turn’ (Holbraad & Pederson Reference Holbraad and Pedersen2017) suggests that, when interpreting another culture, we follow ethnographic data which clashes with our modern concepts to see where they might lead, in which case our archaeoastronomy needs to examine the context for Structure 5 before ignoring this possible alignment. Turning to Structure 4, which is placed so that the view of Silbury Hill is not interrupted by the hill salient, the respective values are an azimuth of 32º north of west and an altitude of 1º.6, which becomes a standardised sea level alignment of 35º.2 north of west. Given that this orientation is as equally far from the northern minor standstill moonsets at 30º.9 north of west for 2250 bc at latitude 51º 26´ north as it is for the summer solstice sunsets at 41º.8 north of west (Fig. 5), we now come to a second conundrum. Faced with one seemingly unobservable alignment and one orientation about 5º apart from either a solstice or a lunar standstill alignment, the common response within archaeoastronomy would be twofold: either to seek some other celestial target for the second orientation and dispense with the first, or to discount any ‘astronomical’ significance to either finding. But since our earlier model predicts that the highly prescriptive views of Silbury Hill will display lunar properties, again by following the ‘ontological turn’ we stay with what to us might first appear to be a nonsensical horizon ‘astronomy’ and continue our analysis of the West Kennet Palisades to seek within what context these paradoxical findings are embedded. If we find no explanatory context, then our expectation that the ontological turn may reveal unanticipated meaning has failed.

The distance from Structure 4 to the 7 m high palisade fence of Enclosure 2 is about 220 m and for an eye height of 1.65 m this nearest palisade sets an altitude of 1º.4. However, the summit level platform of Silbury Hill is at an altitude of 1º.6. and so from Structure 4 the cropped top of Silbury Hill, which is the hill’s top chalk terrace, appears proud of Enclosure 2’s perimeter palisade – the same type of cropped view of the Silbury Hill top terrace as seen at Fox Covert and the Avebury inner Southern Circle. Processing forward towards Enclosure 2 within and surrounded by a funnelling corridor of walls of oak (Fig. 2) creates a sensation of slowly sinking as the tapering and encroaching horizons appear to grow higher. This effect narrows the view of Silbury Hill’s top terrace creating the effect that this sliver of chalk is simultaneously shrinking, sinking into the horizon and reducing its azimuth from 35º north of west until, after about 30 m of processing towards Enclosure 2, its last glint is at azimuth 33º north of west. Its apparent horizon setting position has moved south. This could not be signifying the Sun, for its horizon movements are towards 10º further north approaching the summer solstice limit of about 42º north of west. It could, however, be inferred that this was waxing crescent Moon moving south approaching its northern minor lunar standstill horizon limit of about 31º north of west (Fig. 5). Silbury Hill is next seen when inside Enclosure 2 and standing on the mound in the middle of Structure 1. From this position again the cropped top of Silbury Hill stands proud of the opposite north-west end of the Enclosure (Fig. 8). At an azimuth of 28º north of west and an altitude of 1º.6, the standardised azimuth is 31º.2 north of west, while the alignment of 31º north of west is the same as the northern minor standstill moonsets. This view 12º further west is also consistent with the Moon’s clockwise rotation through the underworld from when last seen at the Sanctuary at 16º north of west. Since the sidereal monthly horizon azimuth extremes for the two or so years of every lunar standstill are not precise but observably slightly different within a range of about 3º (Fisher & Sims Reference Fisher and Sims2017; Sims Reference Sims2019), it is interesting that the width of the flat top of Silbury Hill, when viewed from Structure 1 in Enclosure 2, also subtends an angle of about 3°, so ensuring that all the northern minor standstill moonsets over a period of about 2 years are seen to enter the top of Silbury Hill. Figure 6 shows four horizon views of Silbury Hill found up until the Sanctuary, and Figure 8 shows the computer simulation of the view from inside Enclosure 2 of the West Kennet Palisades. These architectural arrangements which constrain views simulate horizon ‘astronomy’ and clearly are, from all the examples found in our field work, a part of the material artefacts of the Avebury monument complex.

Fig. 8. Virtual model showing the view of the cropped top of Silbury Hill from Structure 1 in Enclosure 2 of the West Kennet Palisades (MacDonald Reference MacDonald2006)

STRUCTURE 5 AND SYNODIC AND SIDEREAL MOONS

What are we to make of the interrupted alignment on summer solstice sunsets at Structure 5? If it were an uninterrupted alignment on summer solstice sunsets combined with an alignment on the northern minor standstill moonsets from Structure 1 inside Enclosure 2, then they are in conjunction and the Moon is hidden in the glare of the Sun and it is dark Moon. Yet the arrangement of Silbury Hill’s top terrace, proud of the palisade artificial horizon, signifies waxing crescent Moon. If it were to be consistent and simulate dark Moon it would be in line and hidden behind the palisade, as it was similarly at Briar Street Bridge and the Sanctuary.

These emergent properties from integrating archaeology, landscape phenomenology, and archaeoastronomy appear contradictory and it seems we face another paradox. Thomas (Reference Thomas1999) pointed out that the top terrace of Silbury Hill is seen in sequence in a series of on/off views when moving through the monuments. However, he also suggests that movement around these monuments would have begun at the West Kennet Palisades ‘where the dead, stones and Beaker pottery were conspicuously absent’, and then from the Sanctuary, along the West Kennet Avenue to the Avebury henge as a movement ‘in the company of past generations’ through ‘a landscape peopled by the dead’. Like the materiality model this ‘suggests two entirely different sets of ceremonial practices between the Avebury henge and the Palisades’ (Thomas Reference Thomas1999, 217–20). Contrarily we have found so far that the Avebury monuments require ritual movement from Fox Covert along the Avenues through the Avebury henge to the West Kennet Palisades for a ritual that begins with ‘death’ at the monument of stone, not life at the monument of wood. Now, at Enclosure 2, we find it ‘ends’ with both waxing crescent ‘resurrection’ and dark Moon ‘death’.

We can step back from this riddle and re-examine its separate elements. Thomas observes that this structure’s design emphasises concentricity through multiple enclosed and nested spaces that would allow either secrecy or seclusion, or the discrete spaces of different size suggest a succession of or simultaneous social performances of constituencies of different size. ‘The structurally distinct interiors of the three smaller enclosures [in Enclosure 2] imply that the activities which went on inside them were differently organised and may have involved the reproduction or transfer of different knowledges’ (Thomas Reference Thomas1999, 218). A different knowledge is being displayed at the Avebury monument complex through monument lunar–solar horizon alignment limits. As shown in Figure 9, during a lunar standstill a complete suite of lunar phases will return close to its lunar limit every 27.3 days. As can be seen in Figure 9, with the top half of the Figure representing the variable northern minor standstill horizon limits, during the summer solstice the lunar phase is dark Moon and at the southern minor standstill, the lower half of Figure 9, during the winter solstice the lunar phase is also dark Moon. This property holds true also for the major standstills (Morrison Reference Morrison1980). Since both the Avebury henge and the West Kennet Palisades have lunar standstill alignments on the winter and summer solstices respectively then it allows just one archaeoastronomical interpretation. This confirms that these few prescribed views of the top of Silbury Hill are meant to be interpreted as centred on dark Moon, and not any other lunar phase, such as full Moon, but displaced and embedded within a 9–10 year period of alternating rituals synchronised with the major and minor standstills of the Moon.

Fig. 9. The minor lunar standstill of 1978, showing the reverse attenuated lunar phases at the horizon extremes. Declination values measure above or below the celestial equator and are not azimuth values, which are shown on Fig. 3. The top half of the figure shows the northern minor standstill and the lower half the southern minor standstill. The reversed lunar phase properties apply to all minor and major standstills of the Moon (Fisher & Sims Reference Fisher and Sims2017; Sims Reference Sims2019) (adapted from Morrison Reference Morrison1980)

Further complex properties are displayed in Figure 9 of what is observed on these horizon alignments every 27.3 days. Any lunar horizon alignment tracking lunar standstills abstract a time-lapsed sequence of lunar phases that reverses the normal sequence of lunar phases. This is because the Moon completes an irregular spiral round the Earth in one sidereal month of 27.3 days (Sims Reference Sims2007; Reference Sims2019), so returning to its original horizon position from which the earlier observation began. But because the Earth is also simultaneously orbiting the Sun, while it itself is being orbited by the Moon, it takes a further 2.2 days for the Moon to re-align in its Sun–Earth–Moon plane to return to its original lunar phase and complete the cycle of the synodic month of 29.5 days. Therefore, abstracting just the time-lapsed horizon extremes by alignments, which signify the 27.3-day completion of the lunar circuit around the Earth, the Moon displays the lunar phase 2.2 days earlier than what was previously seen at that horizon position. This results in a scrolling set of time-lapsed reversed lunar phases as shown in Figure 9. According to this cosmological property, for example, a monument’s alignment on waxing crescent Moon comes 27.3 days before dark Moon during a lunar standstill and not after when it is seen by direct observation during the Moon’s transit through the night sky. This property of lunar standstill alignments would be of great utility to a cosmology intending to reverse another cosmology utilising synodic lunar phases for its rituals. These reversed, time-lapsed, and attenuated lunar phases, culminating in solstice dark Moons which according to these findings are part of the content to Thomas’s ‘different knowledges’, are knowledge of a different and a higher order. Lunar alignments reverse, solarise, and attenuate by a decade the properties of direct lunar observation of the synodic phases of the Moon.

To return to our conundrum: at West Kennet, within Enclosure 2 we see Silbury Hill’s top terrace proud of the north-western palisade fence signifying not dark Moon but a northern minor standstill waxing crescent setting Moon. This contradicts the lunar phase predicted by the conflation of Moon and Sun at their northern standstill and summer solstice horizon limits when the Moon should be dark. But how can Silbury Hill, when seen from Structure 1 in Enclosure 2, signify both waxing crescent and dark Moon when, proud of its background horizon, it clearly can only symbolise waxing crescent Moon after it has emerged from its dark Moon underworld journey which started at Fox Covert? Nevertheless, we have yet to consider the archaeology of Enclosure 1, and we can investigate whether by again applying the ontological turn to this seemingly contradictory archaeoastronomy of Enclosure 2, we can unravel this seeming impasse.

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF ENCLOSURE 1 OF THE WEST KENNET PALISADES

Rather than seeing Enclosure 2 as an incomplete oval, the northern section of its circuit might be better thought of as completed by the course of the River Kennet (Fig. 10), just as was achieved at the Hatfield, Wiltshire and the Hindwell enclosures (Field et al. Reference Field, Martin and Winton2009; Jones Reference Jones2014). This feature allows access by river from or to Enclosure 1 (Fig. 2). There, its double 7 m high palisade and its placement tucked behind this southern end of Waden Hill would have occluded all views of Silbury Hill to the west (Fig. 1). While vision is constrained within Enclosure 1, the sound and senses generated by the dominant presence of flowing water is magnified. The south flowing River Winterbourne turns sharply to the east at Swallowhead Spring, flowing past many springs that all join an east flowing River Kennet through to the West Kennet Palisades. Marshall has shown at least 11 springs within the two West Kennet Palisades (Fig. 10; Marshall Reference Marshall2016, 100). The Waden Spring, which vents a large force of water during and after the winter rains, flows eastward into the River Kennet which continues to flow east through the centre of Enclosure 1. This association between springs and the Palisades was prefigured in the access route to the Palisades from the West Kennet Avenue. We have already noted that, when moving south along the West Kennet Avenue, about 250 m before the Palisades a section follows which had no stones marking its course (Gillings et al. Reference Gillings, Pollard, Wheatley and Peterson2008, 139–40, 202). Instead, Marshall shows that in this ‘empty’ section five springs of the North Kennet group fed a brook whose course continues the route of the Avenue and leads directly to the east entrance of Enclosure 1 (Fig. 10; Marshall Reference Marshall2016, 126, 137).

Fig. 10. The winter waterscape and springs of the West Kennet Palisades and Silbury Hill in 2200 bc (adapted from Marshall Reference Marshall2016, 100)

EMERGENCE FROM AND RETURNING TO THE UNDERWORLD AT THE WEST KENNET PALISADES

In this most secluded of all the structures at the Avebury complex, tucked behind the south-eastern edge of Waden Hill and dropping sharply down to below 145 m OD (Barber Reference Barber2003, 2), Enclosure 1 is completely out of sight of Silbury Hill while linked by avenue and water to both the Sanctuary and Enclosure 2. Before entering Enclosure 1 the Sanctuary’s view is of Silbury Hill’s flat summit in the west and in line with the background horizon, so signifying the Moon approaching the end of its journey through the underworld before it emerges at sunset as waxing crescent Moon. Continuing into Enclosure 2, that same flat summit is then seen just proud of the north-west horizon, and therefore signifying emergence as waxing crescent Moon after dark Moon. This sequence, from waning crescent Moon–dark Moon–waxing crescent Moon, to be consistent with lunar phases around dark Moon, leaves just one function for Enclosure 1 sandwiched between the Sanctuary and Enclosure 2. Not just by the archaeology fitting the role of a dark Moon seclusion chamber, but for those who walk this first clockwise lunar route between Fox Covert and the West Kennet Palisades, Enclosure 1 is therefore that last part of the Moon’s simulated journey through the underworld before leaving it to become waxing crescent Moon in Enclosure 2.

Ten years later we approach Enclosure 2 not from Enclosure 1 but along the southern timber avenue during the minor standstill of the Moon. From Structure 4 and within the avenue we see the top terrace of Silbury Hill shrinking, setting, and moving towards its minor standstill alignment before it is blinked out before entering Structure 1 in Enclosure 2. Once there we have a clear view of Silbury Hill’s top chalk terrace as waxing crescent Moon, as we start a new counter-clockwise circuit around the Avebury monument complex that will next enter the dark Moon seclusion chamber of Enclosure 1. This is the context for understanding Structure 5. When the Moon’s properties are abstracted to just this horizon alignment its lunar phases are reversed, so that the lunar phase before dark Moon is waxing crescent Moon 27.3 days before, not after, the summer solstice. We can now understand, after our ontological delay, why Silbury Hill and the summer solstice alignment from Structure 5 is obscured and the lunar orientation from Structure 4 is short – each anticipated by one sidereal month the movement towards summer solstice and the northern minor standstill, in a reversed, attenuated, and solarised sequence of lunar phases. How can this be achieved without direct sight of the Silbury Hill target from Structure 5? Very simply by raising the eye of an adult Neolithic man of eye-height 1.65 m by 60 cm, which would reveal the Silbury Hill flat summit in line with the flat foreground horizon of the intervening salient. This provides a level surface to the left of Silbury Hill upon which can be seen the sunset one sidereal month, at about 5° or ten solar diameters to the south, before it sets into Silbury Hill itself. There is plenty of complexity within Structure 5 to warrant this hypothesis. It has a double concentric sub-circular enclosure of 90 m and 40 m, the inner enclosure is offset, it has a gap in the inner circuit facing towards Silbury Hill in the north-west and it has about 30 pit or post features within the inner enclosure (Barber Reference Barber2003, 23). The double concentric timber circuit of Structure 5 offers a choice of centre or two tangents as alternative backsights and provides built in anticipation of between 3º.5–1º.5 of approach to the actual summer solstice horizon sunset alignments.

We can now see that the builders required the views of Silbury Hill to present as waxing crescent Moon for two different lunar cycles. The first simulates the synodic cycle of lunar phases by a clockwise route at winter solstice ending at waxing crescent Moon during the major standstill. The second begins 9–10 years later at the minor standstill in Enclosure 2, with waxing crescent Moon 27 days before summer solstice followed at summer solstice by an anti-clockwise route into Enclosure 1, simulating dark Moon. This can only be the case for a reversed set of lunar phases which, of course, is prescribed by the alignment on the northern minor standstill moonsets from Structure 1 onto the Silbury Hill summit. Counting these views by azimuths from north, the sequence of the counter-clockwise views of Silbury Hill are: Enclosure 2 (300º), Enclosure 1 (no view), Sanctuary (286º), Avebury Circle (190º), River Winterbourne (160º) and Fox Covert (95º). These views repeat the reversed and attenuated lunar phases seen in the monuments’ lunar–solar alignments that can be seen in Figure 9. Both circuits, clockwise and anti-clockwise, confirm by two different logics that Enclosure 1 of the West Kennet Palisades performed the function of a dark Moon ritual seclusion enclosure.

The reversed lunar phase views add a further complex property discerned in this cosmology. Waxing crescent Moon, as at the Palisades, is only seen on the western horizon and waning crescent Moon, as seen at Fox Covert, is only seen on the eastern horizon. Seen in this order on a counter-clockwise route these reversed views now represent the Moon moving through the underworld from west to east, not from east to west which is the normal apparent behaviour of the Moon in a planar geocentric Earth cosmology. But moving through the underworld from west to east is the Sun’s direction of travel through the underworld. This second order of manipulated knowledge has not only reversed and attenuated the lunar phases, but also solarised the Moon by its underworld movement. The first clockwise movement is appropriate for the first level of meaning of an initiatory cult for neophytes and the second counter-clockwise movement as the culminating meaning for those completing their initiation into the cult knowledge of a new type of reversed ‘Moon’ now conflated with the Sun. While the views are mirror versions of each other, they are not transposable. The synodic lunar cycle, seen clockwise, lasts 1 month, the sidereral cycle, seen anti-clockwise, lasts 27.3 days and is repeated over a 9–10 cycle. Dark Moon migrates through the year in its synodic cycle but synchronises with the solstices during the minor and major standstills. The sidereal Moon reverses the phases of the synodic Moon and it travels through the underworld from west to east as does the Sun. While they are mirror versions of each other they are antagonistic to each other – they are chiral Moons.

TABLE 2: SUMMARY OF CHIRAL LUNAR-SOLAR MODEL OF AVEBURY MONUMENT COMPLEX

The lunar and solar alignments we found at the Avebury Circle also allow closings to rituals over either a 9–10 year period or even over 19 years if it is stretched to span from one major standstill to the next. The Avebury Circle is therefore a place for entering an underworld ‘death’ at winter solstice during the major standstill of the Moon and emerging from the underworld at the West Kennet Palisades Enclosure 2. Ten years later the underworld is re-entered at Enclosure 2, exiting this second ‘death’ at the Avebury Circle. Having completed this counter-clockwise route for the lunar standstill’s alignments where we first entered the underworld at the Avebury Circle, initiands will then see the Moon emerging on the north-east horizon at the northern major standstill (Fig. 4). At summer solstice it will be dark and at winter solstice it will be full Moon. Once initiated into this ‘knowledge’, a knowledge that contradicts the synodic phases of the Moon, they would then qualify for greeting the next cohort scheduled for the following initiation beginning optimally at Fox Covert 9–10 or 19 years later.

CONCLUSION

The emergent properties found by combining the archaeology, landscape phenomenology, and archaeoastronomy of the Late Neolithic/EBA Avebury monuments supports the materiality model’s view that their structures of stone and wood are part of an integrated, contemporaneous complex. In addition to confirming that the West Kennet Palisades are part of this complex, the findings also confirm that the complex includes a Fox Covert start to the Beckhampton Avenue and, as suggested in 2009 (Sims Reference Sims2009a; Reference Sims2009b), that one of Silbury Hill’s functions was to act as a ‘dynamic lunar facsimile in dark Moon rituals’ (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013, 204). This analysis suggests that the Avebury monument complex is designed as a virtual underworld for the living to conduct initiation rituals. ‘Astronomy’ is here in the service of dark Moon portals to and from the underworld and the same cosmology is found at Stonehenge (Sims & Fisher Reference Sims, Fisher, Henty, Brady, Gunzberg, Prendergast and Silva2017; Reference Sims and Fisher2020).This does not exclude the significance of funeral rites of passage or burials, since walking the prescribed routes through the complex as an underworld is eminently compatible to walking through the land of the dead. But this integration is achieved only when the materiality model is revised to account for lunar governed rituals beginning with ‘death’ at stone monuments and ending after initiation into specialist knowledge by journeying through a simulated underworld (see also Sims Reference Sims2013a). This simulation is achieved through six staggered prescribed views of Silbury Hill’s top terrace which, according to the direction travelled around the monument complex, mimic two different cycles of the Moon. These chiral Moons point to contradictory symbolic properties to Silbury Hill which should allow unlocking of the hidden meaning to all 16 phases of its construction (Leary et al. Reference Leary, Field and Campbell2013). This cryptic specialist knowledge precisely fits the minimum requirements of a cult bent on estranging the legitimacy of an earlier lunar respecting cosmology onto another more suited for a cattle pastoral culture (Sims Reference Sims2006).

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank Bill Romain, Frank Prendergast, Dave Thomas, George Latura, Stephen Colmer, John Hill, Alison Sheridan, Josh Pollard, and three anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts of this paper.