Part III Other musics

12 Traditional music and its ethnomusicological study

Introduction

Oral musical traditions in France, vocal and instrumental, possess infinite wealth and diversity, not least because France is a multicultural and multilingual country. In several regions on the periphery – Brittany in the north-west, a Flemish region in the north-east, Alsace in the east, a southern region that is variously Mediterranean, Catalonia, Occitania, Basque country and Corsica – people mostly did not speak French before the twentieth century. Like languages and dialects, traditional music is usually defined according to regions. This leads to extraordinary diversity as, for example, in southern France, where thirteen different types of bagpipe have been identified, six of them still in use. One should also note that from the 1789 Revolution, France was committed to a major unifying programme that affected all provinces and their cultures; part of this involved the imposition of the universal use of the French language and new republican culture. The intellectual and political centralism that ensued for long decades eventually trumped the diversity and vitality of traditional music, at least until the folk revival revitalised ancient practices late in the twentieth century. This situation helps to explain why French traditional music has been less highly prized than some of its European and non-European counterparts, in spite of its current importance.

With an extensive national campaign of collecting in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, academic and institutional research under the auspices of major museums and national organisations in the twentieth and a major folk revival from the end of the 1960s, traditional music is now strongly supported. Today it is easy to learn traditional music or dance at associations and schools of music, to practise traditional dances at the many traditional balls and to hear numerous traditional regional groups, French and foreign, in concert halls and at national and international festivals (e.g. the Festival Interceltique in Lorient, Brittany, and Rencontres Internationales de Luthiers et Maîtres Sonneurs in Saint-Chartier, Indre). Finally, new research, bibliographies and above all recordings now proliferate.

Long before folk music and instruments started to be collected, traces of popular music, especially rural, appear in French art. Many of Watteau’s pastoral paintings depict traditional musical instruments played by aristocrats and mythical characters, notably shepherds. An instrument inspired by traditional instruments enjoyed great popularity in the French court and society at large in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It was the bellows-blown musette – a sophisticated instrument lavishly finished in wood and ivory that is thought to have been developed in the sixteenth century. Literature (travelogues, novels, etc.) periodically describes traditional music-making, often with remarkable precision. In the nineteenth century, in Les maîtres sonneurs (‘The master pipers’, 1853), George Sand described the performance of Bourbonnais and Berry bagpipes by local popular musicians. Finally, in a number of works of the Romantic or post-Romantic period, it is possible to hear traditional tunes, as in Camille Saint-Saëns’s Rhapsodie d’Auvergne (1884), Vincent d’Indy’s Symphonie sur un chant montagnard français (Symphonie cévenole, 1886) and Joseph-Guy Ropartz’s Dimanche breton (1893). These examples notwithstanding, favoured sources of inspiration for French composers of the time tended to be more exotic: they included Spanish and oriental influences.

Instrumental music

Overview

Apart from isolated cases, like the folklorist Félix Arnaudin (1844–1921) from Gascony, nineteenth- and early twentieth-century collectors were only marginally interested in musical instruments and repertoires. Song alone mattered. Only in the 1910s did Ferdinand Brunot (1860–1938), a grammarian and philologist, begin occasionally collecting the hurdy-gurdies and bagpipes in the Berry region. These early collections were complemented some decades later by Claudie Marcel-Dubois (1913–89) with much more systematic research. However, she concentrated mainly on ritual instruments like the crécelle (ratchet), the hautbois d’écorce (‘bark-oboe’) and the spinning friction drum (toulouhou) from the central Pyrenees used for charivari (a mock serenade also called ‘rough music’). It was the wave of collecting of the 1970s that brought to light an instrumentarium of previously unsuspected richness, even though the results of this exhumation must be put in proportion: the research in question was often conducted on dubious methodological grounds, as certain areas were disregarded simply because they had never previously been investigated. Similarly, for reasons pertaining to the process of constructing regional cultural identities, some instruments were favoured by the folk revival, to the detriment of others.

Traditional French instruments have a heterogeneous status with respect to the separation of oral and written traditions. Whereas their use and repertoires are found in the oral, predominantly rural sphere, the Spanish part of Catalonia and then its French counterpart produced an important written repertoire for its tenora and tibleoboes, which were essential components of the cobla, a traditional music ensemble of Catalonia. Provence underwent an identical process with the galoubet-tambourin, a pair of instruments played by one musician (one hand plays a flute, the other a type of drum, the tambour-bourdon). What makes this phenomenon stand out is the fact that it was documented both in Provence and in Paris, with composers like Joseph-Noël Carbonel (1741–1804) and Jean-Joseph Châteauminois (1744–1815). A new repertoire for the galoubet-tambourin was created, made up of specific types of works (contredanses and menuets) and transcriptions (extracts from opera and comic opera). This written tradition modified practice surrounding this dual instrument profoundly, undermining its oral, vernacular usage. Both developments affecting the Catalan cobla and galoubet in Provence took place in an urban setting and involved the moneyed classes of those societies (industrial bourgeoisie in Catalonia and urban aristocracy in Provence).

Bagpipes

A brief inventory of the main instrumental traditions in France reveals the important role played by bagpipes. In Brittany, apart from the great Scottish bagpipes adopted only recently, the typical bagpipe is the binioù-kozh (‘old bagpipe’), formed by a small, high-pitched chanter, which plays an octave higher than the bombarde (oboe), and a cylindrical, single-reed drone resting on the musician’s shoulder. The regions of Nantes, Guérande and Vendée also have a version of the bagpipe known as the veuze. Like the binioù-kozh it is made of a conical chanter with a double reed and a cylindrical, single-reed drone, which rests on the player’s shoulder.1 Other French bagpipes are to be found in Bresse, Berry2 and Bourbonnais, where we find a large, pewter-encrusted, superbly decorated instrument with a conical chanter, a parallel drone and a larger drone placed on the shoulder.3 In the Limousin, mouth-blown bagpipes called the chabreta (literally ‘small goat’) possess a conical chanter, two cylindrical drones, one parallel to the chanter and the other transverse, pressed to the player’s forearm.4 Its composition and appearance remind one more of Baroque concert instruments than of French traditional bagpipes.

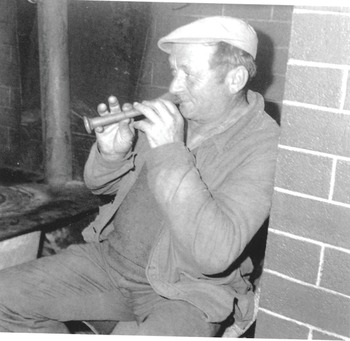

The cabreta, a native of the Auvergne and Rouergue, has only a single drone parallel to the chanter, but since the nineteenth century a bellows has supplied the air. It is also noteworthy that in the Auvergne several bagpipes named after their inventors (Béchonnet, Lardy, Chaput, Stormont) remained at the prototype stage or were manufactured in limited numbers; this was nevertheless all it took to grant some of them the status of regional instruments. Such was the fate of the Béchonnet bagpipes, of which fifty-nine copies have been documented. In addition to a chanter they possess three drones of unequal length and a bag supplied with air by means of a bellows. The boha (from the verb ‘bohar’, to breathe), found in the Landes of Gascony, is unique in Western Europe as it is composed of a chanter and drone bored into a common rectangular body, which makes it similar to Eastern European bagpipes (Figure 12.1).5 In Languedoc we find the voluminous bodega made of an entire goat’s skin, with a long chanter and large drone resting on the musician’s shoulder (Figure 12.2).

Figure 12.1 Jeanty Benquet (1870–1957), boha player, in Bazas (Gironde, Gascony), photographed in 1937

Figure 12.2 Pierre Aussenac (1878–1945), bodega player

Oboes and clarinets

In regions where we find bagpipes, numerous oboe traditions also flourished. The instrument, of varying shapes, can be made in one or two sections, or three in the larger instruments. French oboes possess six to seven finger holes, generally located on the front of the body, and are without keys, except for the Breton bombarde and the Sète oboe (from Languedoc). As a general rule, these oboes are neither chromatic nor tempered; their production seems to have been frozen in time, despite two centuries of potential modernisation. The bombarde in Brittany figures among the main traditional French oboes.6 It is sometimes known locally as the talabard, which denotes a small oboe in two sections. In its modern form it is chromatic with keys (Figure 12.3).7

Figure 12.3 Bombardes constructed by Jean-Pierre Jacob (1865–1919), a professional turner from Lorient (Morbihan, Brittany). From left to right, the instruments are in A, B♭ and B

In Bigorre, Gascony Pyrenees, the principal oboes are the clarin, a small instrument in a single section (Figure 12.4), and the claron, a large, three-section instrument. In Couserans (Gascony Pyrenees) we find the aboès, and in Languedoc the grailes,8 which, like the aboès, are large, three-section instruments measuring around fifty centimetres, devoid of keys.

Figure 12.4 Marc Culouscou de Gèdre (High Pyrenees) plays the clarin

Arnaudin describes the manufacture of a tchalemine or ‘crude oboe’ in the Landes of Gascony. This instrument’s body, according to his account, comprised ‘a tube made of alder, willow, or old pinewood, slightly cone-shaped, approximately 30 centimetres long’.9 Marcel-Dubois observed the hautboisd’écorce (bark-oboe), made with chestnut bark rolled into the shape of a cornet; it is native to Vendée (west of France) and Bas-Comminges (Gascony), though it is also found in other French and European regions. It is used either as a kind of signalling instrument or for ritual purposes (in charivari and on Good Friday). Traditionally, on Good Friday there are ‘tumults’, which Marcel-Dubois described as ‘ceremonial rackets’.10 Men or sometimes young boys play noisy instruments made of wood (clapper board, ratchets, etc.) or strike metal objects (cans, stoves, pans, watering cans, etc.) with all their might. This acoustic evocation of the death of Christ is part of a noisy treatment of death in European societies over the past centuries in both funeral rituals and symbolic representations of death.

It was customary to make small clarinets out of oat, wheat, barley hay and elder wood. They were generically called chalemies; animal horns were added to them as bells, as in the case of the caremera in Gascony. In addition to being played by children and shepherds, these instruments could be used to teach music to people from humble social backgrounds. One should add that the clarinet, particularly the thirteen-key version found in the Breton musical tradition (where it is known as treujeun gaol, the ‘cabbage’s foot’), and in some other regions, sometimes substituted for the traditional oboe, as in Couserans.

Flutes

The most notable flute traditions are those of the fifer (pifre in Occitan) and of flutes played with one hand, accompanied by a drum drone (membranophone or chordophone), like the galoubet-tambourin. The fifer is a small transverse flute with no keys (or with a single key called ‘de Rippert’), which has been played in Western Europe since the end of the fifteenth century. For a long time it was used by the military or paramilitary, before being adopted by the urban and later rural male youth for conscription rites and carnivals (like the boeuf-gras – ‘fattened ox’ – in Bazas, Gascony). Today the fifer is to be found in French Flanders, Bazadais, Quercy, Languedoc, Provence and the environs of Nice.

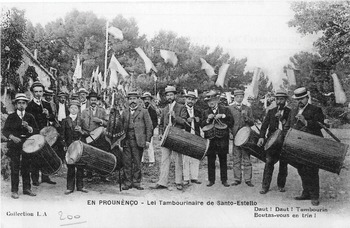

Flutes intended to be played with one hand are documented in three regions. The first is the Basque country, with its txirula in the Soule province and the txistu in the areas closer to the coast. The second region is Provence, where the galoubet or flûtet has the status of a typical regional instrument. It can have variable length and tuning, and is played with the accompaniment of a long, cylindrical drum (see Figure 12.5). The third region is Gascony, where this type of flute is known as flahuta, both in the mountainous area (Béarn) and in the plains. It is tuned in A in Béarn and in C in the plains, and is accompanied by a stringed tamburin, the so-called ttun-ttun (a zither with six strings, tuned to either the tonic or the dominant of the flute).

Figure 12.5 Group of tambourinaires (galoubet-tambourin players) in Provence: one musician is playing a pair of small drums attached to his belt

Violins and hurdy-gurdies

France does not have a lute tradition, if one excludes Corsica and certain traditions brought in by immigrants. Harps and lyres are absent too, except for the ‘Celtic’ harp of Brittany, whose tradition was invented recently. In the Vosges we find the épinette (a small zither played by plucking the strings), and in Gascony the stringed tamburin, whose six gut strings are struck with a cylindrical, leather-padded wooden stick. Setting these exceptions aside, bowed string instruments feature above all others in French musical traditions: they are the violin and the hurdy-gurdy, whose strings are sounded via a revolving wooden wheel.

The violin enjoys a privileged position in Brittany, Poitou, Gascony, Limousin, Auvergne and Dauphiné. It is sometimes made by the musician himself, who uses local woods and often only rudimentary tools, ill adapted to the purpose; paradoxically, the results are often masterpieces of popular art. The hurdy-gurdy is, in a sense, a polyphonic instrument, since its wheel can sound all its six strings at once. Four of these are sounded as open strings (called gros bourdon, petit bourdon, mouche and trompette), which allow the hurdy-gurdy to act as the main drone instrument (along with bagpipes, with which it is often associated in central France). It is found in a large variety of types and shapes: its body can be rounded, like a lute’s, flat, or 8-shaped, like a guitar’s. The instruments are often highly decorated with wooden inlays, painted decorations and a sculpted head. In these examples, the makers are frequently famous craftsmen of the nineteenth century, such as Pajot, Pimpard and Nigout in Jenzat (Auvergne). But when the players make the instruments themselves they can also have an unrefined appearance. The hurdy-gurdy is associated with the Savoy region (pedlars and chimney sweeps from this region are often depicted with a hurdy-gurdy), the area south of the Alps, all of central France (Limousin, Auvergne, Berry and Bourbonnais) and Brittany and Gascony.

Drums

There are numerous percussion instruments, many of which are generic in character and therefore not extensively studied. Some are worth mentioning on account of their extensive use and distinctiveness. The drum used universally in the accompaniment of fifre orchestras, oboes and various open-air musical performances is the tambour, known as bachas in Provence. No drum is struck with the naked hand in France: all are played with one or two sticks. The use of the drum is documented well before its employment in military music in the late eighteenth century and nineteenth century. It was extensively employed in processional urban music of the seventeenth century, and it has sometimes been used unaccompanied as a dance instrument, especially in rural areas.

Space dictates that the foregoing instrumental inventory omits many instruments, including some that have played an essential role in certain ritual and pastoral contexts, as well as in children’s music.

Ensembles

In the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there was a collective instrumental practice perpetuated by ménétriers (literally ‘minstrels’, in fact early popular musicians), semi-professional instrumentalists in rural areas and smaller towns and professionals in the larger ones, where they were organised in guilds. As poly-instrumentalists, they formed ‘bands’ or wandering orchestras that varied according to circumstance. They were made up of violins or oboes of different sizes and registers, and were systematically polyphonic. This tradition was largely defunct by the eighteenth century.11 Nevertheless, despite a decline in the status of this kind of music during the nineteenth century, certain orchestra-type ensembles have appeared in some regions.

In Brittany, the binioù-kozh (bagpipes) and bombarde (oboe) constitute the most representative regional ensemble. Since the 1950s and 1960s Brittany has also adopted the bagad, inspired by Irish and Scottish pipe bands; it is made up of binioùs, bombardes and drums.12 In Paris, among the community of Auvergne immigrants, the cabreta bagpipes united with the accordion around 1905–6. This union is attributed to Antoine Bouscatel, a famous player of the cabreta born in 1867, and Charles Peguri, a Frenchman of Italian origin born in 1879. This encounter is said to have marked the birth of the musette genre, one of the most significant in French popular dance music of the twentieth century. In the Pyrenees and Gascony, oral statements, old photographs, historical iconography and other evidence indicate that the one-handed flute and a violin were another musical duo. In Bas-Languedoc, the traditional oboe is played with the drum, either in small bands or as a duo. This last configuration is found, for example, on the occasion of ‘nautical jousting matches’, held along the coast of this region, particularly in Sète. Two contestants placed at the rear of a large boat try to push their opponent into the water, accompanied by an oboist and a drummer who play on the deck of the boat. In the Bazas region (Gascony), in the Var département (Signes inland, Fréjus and Saint-Tropez on the coast) and in the valleys around Nice, the fifer is still played in bands alongside drums and bass drums.

The repertoires of instrumental music

The oral nature of the music-making and the lack of interest in musical instruments among French collectors in the Romantic era explain the lack of historical documentation of traditional instrumental repertoires. Research undertaken in the twentieth century, especially since the folk revival of the 1970s, tells us most about the nature of these repertoires.

Ethnomusicological investigations have produced evidence of numerous regional dances, often very distinctive, which constitute the major share of traditional instrumental repertoires. These include gavottes, an-dro, hanter-dro, ronds and dañs tro in Brittany – some of which could also be sung; maraîchines and avant-deux in Poitou; bourrées in Limousin, Auvergne, Berry and Bourbonnais, with significant differences in rhythm and the dance sequence between these regions; rondeaux in Gascony; branles and sauts in Bearn; branles and farandoles in Languedoc and Provence; rigaudons in Dauphine; and so on. In the nineteenth century new partner dances appeared throughout Western Europe, including waltzes, polkas, mazurkas and schottisches (a round dance) which were imported into France. They generated local compositions adapted to indigenous musical forms and instruments. Whether it was the regional dance forms or more recent, standardised dances, these repertoires were most often taken up by the bagpipers and violinists early on, though in some regions the hurdy-gurdy and one-handed flute have accompanied these dances. The diatonic accordion at first and later its chromatic successor eventually became the leading instrument of dance music. Dance performed at balls, village festivals, weddings and banquets, on Sunday afternoons in cafes and at annual events like carnival remains by far the main pretext for instrumental music. The exceptions to dance music include laments comprising slow melodies, sometimes dérythmées (without rhythm), played in diverse circumstances, such as weddings in the Auvergne, where cabreta players produced sad, plaintive melodies that were designed to render the bride tearful.

Finally, musical instruments were involved in many rituals such as annual public holidays: carnival in winter, the Easter egg hunt, farm holidays in summer, rituals connected with the grape harvest in autumn, and Christmas. There was also music for weddings; for holidays related to such rites of passage as conscription; for local political processes, including the election of new mayors; and others. Finally there are religious rituals such as pardons (a popular form of penitential pilgrimage) in Breton-speaking parts of Brittany; religious processions, including one where the chabreta played in processions of religious brotherhoods in sixteenth-century Limousin; and midnight Mass at Christmas.

The ritual contexts having mostly disappeared by the time the folk revival was under way in the 1970s, it was the dance music that remained to be collected and played by today’s traditional musicians.

The voice in traditional music

In France vocal styles and timbres are very varied in character, but it is possible to identify some constant elements in terms of techniques and vocal colour. For example, the voice will be powerful in the context of agricultural labour, as in the briolée (ploughing song) recorded in Nohant (Berry) in 1913 by Ferdinand Brunot; here the singer interrupts his own song with cries and exclamations, as well as holding notes over very long breaths.13 In Mediterranean countries, and therefore also in southern France, these powerful voices are high-pitched, which partly explains the importance of the tenor voice in polyphonic music of the Pyrenees and Alps. These high-pitched, powerful male voices, which are described in France as ‘clear voice’ (voix claire), are found in varying degrees in the Balearic Islands, Catalonia (especially in the cant d’estil), Malta and even Romania, where singing in a very high chest voice constitutes a dangerous physiological exercise.14 Historically opposed to the hoarse voice of the devil and so adopted by Western Christian culture, the ‘clear voice’ became the characteristic sound of Pyrenean and Alpine shepherds in southern France. Enjoying a special status in traditional Christian societies, the shepherd’s vocal style was highly valued, especially by folklorists of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; witness Jean Poueigh, who collected Pyrenean songs.

Whereas ornamentation styles in traditional singing more or less follow regional French traditions, the use of portamento is virtually universal. This vocal technique connects various notes by rising and falling glissandos and emphasises the general outline of the melody; it also allows both the stress and mitigation of significant intervals, such as the fourth that starts many melodies sung in France. Singers frequently place grace notes on the accented notes of a melody (see Example 12.1), which strengthen the rhythmic aspect of their interpretation and personalise it.15 Another method of ornamentation is sometimes to interpolate ornamental melismas, especially in longer songs with a relatively free rhythmic structure.

Example 12.1 Grace notes on the accented notes of a melody

All folklorists and researchers who have studied the songs in oral traditions note the extremely stereotypical nature of their texts, which consist of a succession of images and character types (the prince, the shepherdess, the miller and so on). These songs are predominantly timeless and refer to stereotypical places that are not identified and localised (‘behind me’, ‘the clear fountain’, etc.). In spite of the presence of some rare songs on historical subjects in French regional directories, the impersonal and the stereotypical dominate. In Britanny this makes the gwerzioù (plural of the word gwerz) a notable exception, for these songs are substantial laments (or ballads) about historical events, more often than not criminal, from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Their authenticity has been established by a search in the Breton judicial archives of the ancien régime.16 In Brittany, the corpus of gwerzioù known to date is considerable; it comprises thousands of songs, many of which possess dozens of stanzas in the Breton language. Some of these songs were printed on loose leaves at the time, but many remained in the oral tradition, awaiting collection in recent times. The tradition of the lament spread quite widely in France under the ancien régime and in the nineteenth century. But unlike in Brittany, these laments are few in number and almost never sung in local languages. Alongside the songs in the oral tradition, urban as well as rural France knew to varying degrees the art of the songwriters, who were more or less literate local poets. They described the life of their times in texts of their own composition. Unfortunately, this tradition did not arouse the curiosity of folklorists at first or the later ethnomusicologists, at least not until recently.

It is of interest to focus on the linguistic status of songs in the oral tradition in the regions where different forms of French are spoken. In these regions most traditional songs are sung in the local language, but it seems that some regional songs might be conceived entirely in French (as in the Pyrenees) or bilingually. The study of bilingualism gives us valuable insights into the status of regional languages versus French.

In France, many popular songs combine local texts (which have many variants) with melodies in vogue at the time. The song then has the inscription ‘sur l’air de … ’, and the melody is referred to by the incipit of the original song, as in ‘on the air of “Malbrough s’en va-t-en guerre”’. This process is extremely interesting because it allows one to measure the historical impact of some borrowed melodies away from their local context. In addition, these melodies often originate in operas, vaudevilles and operettas of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries – a remarkable hybridisation between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture.

Traditional songs have many functions: educational and recreational for children, amorous, social, ritual, initiation and so on, for adults; they were the subject of a homogeneous categorisation in important nineteenth- and twentieth-century anthologies. There are, however, two outstanding functions, one universal, the other very common, that give rise to specific vocal practices: funeral lamentations and dance-songs. The first were still practised everywhere in France in the nineteenth century, as witnessed by Arnold Van Gennep in his Le folklore français, where he writes that they ‘moaned and cried’, and ‘emitted such shrill cries’ and ‘frightful howls … that one could hear them two kilometres away’.17 In Corsica these lamentations have produced several literary genres, including the voceri and lamenti, and are still in use in some localities where it is not uncommon to hear women in charge of the ritual lamentation at funerals.

From a stylistic point of view, these lamentations are close to actual sobbing. They consist of long, monotonous litanies in which the virtues of the deceased are shouted out in a very stylised manner. To turn to the other category, dance-song has been in vogue in many French rural areas. These songs are performed by specialised singers who are really ball musicians, and could be taken up by the dancers in responsorial forms, as in the Pays Vannetais (Brittany). It has often been suggested that dance-song was performed in the absence of instrumentalists. I think that this purely functionalist explanation is unsatisfactory. Singing to dancing brings voice and body into a gestural unity, and also implies that the dancers sometimes become their own musicians. This gives a special energy to the dance and promotes social unity among the dancers. I had occasion to encounter several dance-song singers in valleys of the small region of Couserans (Gascony Pyrenees) in the late 1980s; they were then very old and no longer sang, but they vividly remembered how it was done. For Christmas, carnival, Easter and vigils at night in homes or cafes in these villages, a singer au tralala (the custom of singing to dancing) stood alone, away from the dance, and it was only the sound of his voice, sometimes supported by clapping or striking a stick, that got everyone dancing. The repertoire comprised ‘old’ dances (bourrées), sung by men (only one woman was reported to me), whose voice was often very high-pitched, very resonant and very noisy, sometimes mimicking certain instrumental sonorities.

Imitation processes lie at the heart of popular, primarily instrumental musical practices. One of the most popular instruments for imitation is the violin, with traditional violinists imitating animals – the braying of a donkey, birdsong – and other musical instruments (e.g. hurdy-gurdy and bagpipes). The voice is also an imitator. In a village in Haut-Languedoc, Le Mas-Cabardès, an old local bagpipe player (of the bodega), too old to play at the time he was discovered, could sing and imitate the sound and playing of his pipes, notably ornaments made with the thumb of the left hand on the lower hole of the chanter. In Limousin one observes a strong practice of dance-song among the violinists, who alternate sung and instrumental verses in bourrées of their repertoire.

Song can be associated with the male or female voice according to function. While domestic songs, especially for the education of children, and funeral lamentations are usually reserved for women, dance and ritual songs are the domain of men. Work songs are sexually divided depending on the activity concerned. Songs not associated with a specific context (historical and sentimental songs, for instance) may fall to either sex, even though many women are nowadays among the leading figures of traditional singing in France.

Recordings of vocal music are mainly of solo song, so it is difficult to classify the distinct vocal forms requiring two or more voices, except by resorting to the general and vague concept of heterophony, the superposition of different realisations of essentially the same melody, simultaneous variations of which create a form of polyphony. On the other hand, the Breton form of responsorial song, the kan ha diskan, is very specific: two voices answer each other, overlapping for a brief moment at the end of phrases, following the process of tuilage, which denotes the overlapping created when the second singer repeats the last syllable of the first singer, thus making the song seamless.18 In addition, in Bigorre and Bearn in the Gascony Pyrenees and in the southern Alps, there are forms of a cappella tonal polyphony where two (more rarely three) voices sing in parallel thirds over a bass. In these regions, major exponents of polyphonic singing in the oral tradition have survived until recently or still exist, including Zéphirin Castellon of Belvedere (Vallée de la Vésubie, département of Alpes-Maritimes), singer, author and composer of polyphonic songs, fife player and bell ringer. In the Pyrenees one encounters many male choirs in the folk style, whose origin dates back to the nineteenth century and whose repertoire comprises choral classics, including hymns and excerpts from the works of Halévy, Gounod, Meyerbeer and others, plus local songs in the Occitan language, harmonised in a tonal manner.

This geographically distinct area of traditional tonal polyphony in France, on the southern margins of the country, merges with a much larger area (a large part of the Iberian peninsula, the Alps, Italy, etc.). However, in a few exceptional regions of southern Europe, there are forms of modal polyphony. Sardinia is a good example, as is Corsica, with its tradition of paghjella. Especially evident in northern Corsica (the Casinca and Castagniccia regions), this form of vocal polyphony is traditionally male and most often involves three different voices entering in succession. First, the main voice (a seconda) launches the song alone, setting the tone; it is immediately joined by the bass (u bassu), which supports it; and then by the highest voice (terza), which is essentially responsible for ornamentation. In general, melodic motion is descending, and a major chord at the end replaces the many minor chords we hear throughout the song. With no predefined function, the paghjella’s subjects are generally secular (they include lamentation, seduction, satire, etc.), but it may also take on religious forms. Recorded by Félix Quilici on three field trips that he led on the island between 1948 and 1963, the paghjella still plays a significant role, especially for its visual spectacle and very specialised polyphonic organisation. With the religious a concordu and secular a tenore polyphonies of Sardinia it forms an ensemble of modal polyphonies, unique and highly localised. This explains why the paghjella has become a strong symbol of cultural identity in Corsica. In 2009 it was added to UNESCO’s list of the world’s intangible cultural heritage for urgent protection.

While vocal performance is still a viable subject of research, the last traditional instrumentalists are almost all gone. In France, Patrice Coirault (1875–1959) was the first to approach the study of the songs in the oral tradition in a critical and scientific manner; he established an analytical method for form, structure and other elements that made up folksong, such as linguistic duality of regional versus the French language, song subjects and phraseology (clichés, versification, metric and strophic forms).

Melodic and rhythmic structures

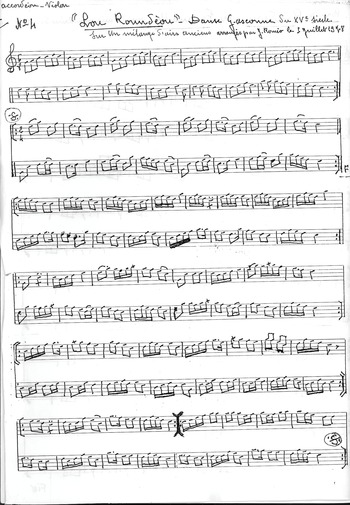

Many melodies are not specific to a region or tradition, for they derive from fairly recent and widely diffused repertoires, such as eighteenth-century operas and operettas, military music, partner dances, nineteenth-century country dances, amateur ‘popular’ choral music and so on. Other melodies taken down in the nineteenth century or gathered recently have a modal structure. So in Gascony, besides an essentially tonal instrumental repertoire we find rondeaux in the Lydian mode. Sometimes melodies display modal-tonal ambiguity: for example, the violinist Camille Roussin (in Dauphine) plays a mazurka whose first phrase is in G major, whereas the second phrase is Mixolydian. Furthermore, certain melodies in dance-songs can be analysed as consisting of two phrases in different keys, such as D and A. In certain cases musicians build instrumental suites, following not only the type and rhythmic structure of the dance they are accompanying but also certain melodic modes (see Figure 12.6). We commonly find songs, especially dance-songs, in which the range is limited to just a third or a fourth, as in Example 12.2 from the Gascony Pyrenees.19

Figure 12.6 Rondo suite from Gascony, constructed and written by the violinist Joseph Roméo (1903–89), active 1920–30 in the area of Agen

Example 12.2 In this sung branle from the Pyrenees, the range of the melody is just a third

Vocal and instrumental repertoires not related to dance sometimes display complex rhythms simply because of the flexibility shown by the performers; notating them by means of a regular time signature becomes something of a challenge. For this reason, Jean Poueigh, a Pyrenean folklorist of the beginning of the twentieth century, considered that the rhythmic notation of the songs was problematic: ‘Apart from dances, for which a firm structure is indispensable, popular melody is fluid and shifting … Anyone who has tried to notate the old airs on a peasant’s lips knows what problems they sometimes present. They are so undulating, and bar lines are so rigid.’20 Nineteenth-century folklorists, brought up with metric phrasing, tried to erase these rhythmic ‘irregularities’ from their anthologies and, as in the work of Frédéric Rivarès (1812–95), did not hesitate to ‘constrain the rhythm, restore the bar, and thereby give regularity to the air’.21 Dance music, generally regular, is in either simple or compound time, though some rondos from Gascony display a degree of ambivalence. Example 12.3 shows two rondos taken from the repertoire of Léa Saint-Pé (1904–90), an accordion player from the region of Lombez (Gers, Gascony). The B phrase is such that it could just as well have been notated in 6/8. This accordion playing shifts between binary and triple time (2/4 and 6/8).

Example 12.3 Two rondos taken from the repertoire of Léa Saint-Pé (1904–90), region of Lombez (Gers, Gascony)

Within the same instrumental tradition, ornamentation varies greatly between regions, sometimes even between musicians. There is a tendency to attack the openings of phrases by a fast leap of a fourth. Some instrumental styles exhibit ornamentation of amazing virtuosity. For instance, in some bagpipe performance traditions, notably the cabreta in the Auvergne, the tonic note is played between every other note by covering all the holes of the chanter (the so-called piqué technique, which requires very fast fingering).

Apart from a certain degree of variability between individual musicians, ornamentation contributes to determining a regional style, as can be verified if one compares the violin traditions of Gascony and central France (Auvergne and Limousin). The impact of classically trained teachers is significant too. After being largely self-taught, some traditional Gascony violinists have been influenced by a local teacher with a classical background. This influence is noticeable in an ‘academic’ posture (where the instrument rests on the neck, not on the chest as in regional traditions) and handling of the bow at the heel, not two-thirds or half of the length up, as sometimes occurs in the Auvergne, Limousin and Dauphine. Playing techniques are also significantly marked by this phenomenon: in Gascony, violin playing is often more sober and less ornamented, and makes more use of vibrato; bowing is more detached, strong beats are emphasised, and the violinist marks the strong beats in dance music, at the beginning of either phrases or bars, with double stops or even quadruple stops when the melody is in G major (sounding, in order of ascent, G–D–B–G).

Some violinists from Gascony know how to play in the instrument’s high register (third or fifth position), which enables them to perform the brilliant and highly technical mazurka, polka and schottische dances. In contrast, in the Limousin region bowing is much more legato (one bar or more per bow stroke) and the style is highly ornamented. This ornamentation, which the ethnomusicologist Françoise Étay describes as ‘luxuriant’, has several functions:22 to accentuate certain notes, to re-launch the beginnings of new phrases, to tie two phrases together via a group of notes and to accentuate the general dynamics of the melody. Here, variation appears not just in the form of ornamentation; it also encompasses rhythm by prolonging a beat at the expense of the next one, resulting in a syncopated effect.

Most pieces of dance music are made up of two, sometimes three, phrases played twice; each is usually limited to four or eight bars. In this static construction, the parts cannot be interchanged – a rigid structure known as ‘mono-modular’. It is not a specifically French quality; it is found in numerous instances of dance music throughout Europe. Despite the musician’s creativity and personalisation of practice and style, this type of construction does not allow for any improvisation. At best it permits some variation.

Nineteenth and twentieth centuries: ethnomusicological studies of French traditional music

Nineteenth-century Europe: a ‘pre-history’ of ethnomusicology

According to the few histories of ethnomusicology that have appeared to date, the discipline was born at the end of the nineteenth century. But one wonders how it is possible that the Eastern European school (created by Béla Bartók and Constantin Brăiloiu), one of the three founding schools of ethnomusicology, appeared ex nihilo. How could they have dispensed with the precursory role played in the nineteenth century by Western Europe and especially France? The link between European ethnomusicology at the start of the twentieth century and the European Romantic collecting trend of the nineteenth century is evident in the observations and recommendations found in the methodological works of the two founders of the Eastern European school.

In France, the collector movement had a peculiar history in that it was conceived and organised as a centralising force, an initiative of the political powers; and as it had perforce to adopt successive methodological stances, it is no exaggeration to identify the early origins both of ethnomusicological field research and of ethnographical empiricism in general in this movement. The nineteenth century was studded with political initiatives motivated by the will to preserve cultures that were thought to be in decline; their aim was to promote and structure a national policy of collecting ‘traditional’ songs. One example of these initiatives is Emmanuel Crétet de Champmol, minister of the interior under Napoleon I, who produced a document in which he suggested a ‘[gathering of] the monuments of the Empire’s popular idioms’ in 1807.23 There is also Narcisse-Achille de Salvandy, minister of instruction publique, who in 1845 created a Commission of French Religious and Historical Songs, which had the task of gathering and publishing folksongs. Finally one should add Hippolyte Fortoul, minister of instruction publique and cultes, who on 13 September 1852 signed a famous decree ordering the publication of a general inventory of French folk poems.24

This movement is inscribed in the long history of the awakening of a European sensibility to exoticism and oral culture, but it is already apparent in the sixteenth century’s numerous accounts of journeys and autobiographical texts of ethnographical character and, later, in the publication of ‘exotic’ folksongs, which began around 1750. In order to understand this history, it is necessary to place it in the much broader context of the history of Western societies’ discovery of an ‘internal exoticism’, which would later contribute to the development of the human and social sciences.25 From 1790 onwards, this process of discovery in France is marked by several specific initiatives: the investigation of regional languages conducted by the abbot Grégoire; the creation of the short-lived Société des Observateurs de l’Homme (1799–1804); the founding in 1804 of the Académie Celtique (in 1812 it became the Société Royale des Antiquaires de France, which lasted until 1830); the creation in 1839 of the Société Ethnologique de Paris (to 1848), replaced in 1859 by the Société d’Ethnographie de Paris; the launch by the minister of instruction publique of the Monographies Communales (a series of monographs compiled by local teachers, each on an individual town or village, which described its history, culture, population, etc.) in 1887; and the emergence and structuring of the notion of ‘heritage’ and concomitant policies on a national level, a process which endured throughout the nineteenth century. Above all there is the crucial achievement of the Statistique Départementale. Introduced in 1800 and placed under the authority of the newly instituted préfets (officials assigned to a specific département), this inventorial undertaking is, among other things, an immense ethnographical taxonomy in which ‘the arts, customs and habits of the inhabitants of the départements – rural life and popular traditions – are given significant weight’.26

Ethnographical research in nineteenth-century France was characterised by the significant social and cultural gap, particularly evident after 1852, between researchers and the population being researched; this tends to reinforce the problematic dichotomies between ‘learned’ and ‘popular’ spheres, and thus between written and oral traditions. They are evident, for example, in the case of the Comité de la Langue, de l’Histoire et des Arts de la France instituted by Fortoul, where the ‘section for philology’, responsible for a ‘collection of traditional poems’, was formed by twelve members, all of whom came from the Académie Française, other academies, the École des Chartes and ministerial cabinets. This committee relied on a national network of 212 regional correspondents, including members of the clergy, functionaries and notables, lawyers, archivists, librarians and occasionally composers. These researchers discovered the world of oral traditions, whose existence had previously gone unnoticed, as well as the unsuitability of their writing tools for any kind of faithful transcription of these traditions. The Fortoul research generated numerous publications, which are valuable sources for the ethnomusicology of French traditional music.

The twentieth century: institutional and academic ethnomusicology of French traditional music

Whatever the precursory role played by the nineteenth century in its birth, ethnomusicology began its institutional history in France only in the first decades of the twentieth. This history is a unique phenomenon in the global history of ethnomusicology because of its bipolar development: on the one hand investigations were conducted in France, and on the other, researchers travelled to foreign territories.

The Musée d’Ethnographie, founded by Ernest Hamy in 1877 and located in the Palais du Trocadéro from 1879, was directed by Paul Rivet in 1928, with the collaboration of Georges-Henri Rivière (1897–1985). Between them they transformed this museum of ethnography into the Musée de l’Homme. Rivière appointed André Schaeffner to the section dedicated to music. In 1929 Schaeffner created a Département d’Organologie Musicale, which became the Département d’Ethnologie Musicale in 1932, and has existed until recently under the name Département d’Ethnomusicologie. As well as – and to some extent in opposition to – this institution, which looked outside France, especially to traditions outside Europe, Rivière created the Musée National des Arts et Traditions Populaires (MNATP) in 1937, first as part of the Musée de l’Homme, then as an autonomous institution. It was explicitly bound to a ‘folkloristic ethnography’ operating within the field of French cultures. Rivière entrusted the ethnomusicological component of the new museum to Marcel-Dubois. She subsequently founded the Département d’Ethnomusicologie de la France et du Domaine Français in 1944. The institutional division between research on foreign and French provinces was clear-cut and admitted no exceptions.

One of the characteristic traits of folkloristic collections in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries before the large-scale institutional campaigns was the predominance of the method of copying under dictation, rather than recording the sources directly with a phonograph, the use of which was only occasional. However, we know of a wax cylinder engraved around 1890 by the abbot Privat from Mur-de-Barrez (Aveyron), which presents an anonymous singer from Cros-de-Ronesque (Cantal).27 It constitutes the oldest European evidence of this kind. In addition, the Breton singer Marc’harid Fulup from Pluzunet (1837–1909) was recorded in 1900 by François Vallée. The first to make systematic use of recording was Brunot, who created the Archives de la Parole in 1911, thanks to Pathé’s donation of an experimental recording device. He organised three successive trips, to the Ardennes in 1913 and to Berry and Limousin in 1914. The Archives de la Parole became the Musée de la Parole et du Geste in 1932, then the Phonothèque Nationale in 1938; it is currently known as the Département Audiovisuel of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France. Roger Dévigne, its first director (1938), conducted several ‘phonographic field trips’ in 1939 to the Alps, Provence and Niçoise regions; in 1941–2 to Languedoc and Pyrenees; and in 1946 to Normandy and Vendée.

The MNATP carried out field trips in musical folklore after the Second World War. These brought Marcel-Dubois to Lower Brittany (1939), the Pyrenees (1947), the Landes (1965), Bayonne (1951), Aveyron (1964–6), Haute-Loire (1946, 1959, 1962), Cantal (1959) and Aubrac (1963–5), in a campaign conducted by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in which Jean-Michel Guilcher, Jean-Dominique Lajoux, Francine Lancelot and Maguy Pichonnet-Andral also participated. The resulting collections allow one to study vocal and instrumental styles, plus their musical contexts, that have now disappeared. Until recently, one could listen to them at the MuCEM (Musée des Civilisations d’Europe et de la Méditerranée), which succeeded the MNATP (the recordings have been given to the Archives Nationales).

Numerous other large-scale collections, not necessarily academic or institutional, survive: Marc Leproux, a teacher, operated in Charente Limousin between 1939 and 1946; Pierre Panis researched traditional dances; Félix Quilici was active in Corsica within the framework of CNRS and MNATP initatives; and Michel Valière conducted research in Poitou from 1965 onwards for the University of Poitiers. Their collections appeared at a time when it was possible to hear and witness repertoires and musical styles, vocal and instrumental, alongside their dance sequences before they disappeared or fundamentally changed.

In most French regions, in the late 1960s large-scale associations appeared whose purpose was to collect material with a view to sustaining musical and dance practice, instituting a form of education in support of these practices, undertaking editorial projects and so on. In the 1980s and 1990s, thanks to the initiative of the ministry of culture and revivalist musicians and collectors, traditional music and dance collections started acquiring a certain structure, at first on a national level with the creation of a Fédération des Associations de Musiques et Danses Traditionelles in 1985, then on a regional level with the appearance of regional centres for traditional music and dance. All these structures are associated with the state. The result was impressive: in fifteen years France saw more collections arising from ethnographical fieldwork than the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries had achieved.

These collections have allowed a census of the last living traditional musicians and dancers. They have made it possible to film and record them, to gather up a part of their repertoire and to record their stories. They have also filmed traditional regional dances and studied instruments, including bagpipes, oboes, flutes and hurdy-gurdies, which have since become models for reproductions by skilful craftsmen.

Whereas the first revivalist collections were essentially utilitarian in nature (one amassed musical material and tried to rehabilitate it in order to save a threatened culture), a more scientific approach was gradually introduced, typically because several researchers entered third-level and doctoral programmes. A revivalist ethnomusicology concerned with French fieldwork gradually came together and ended up finding a place in schools of music and conservatoires thanks in part to the ministry of culture.28

Methodological considerations

Following in the footsteps of the French Romantics, the research by or for the national institutions (the Archives de la Parole, Phonothèque Nationale, MNATP) is almost exclusively conducted within rural contexts, which perpetuated the tradition of Bartók and Brăiloiu. Brăiloiu had a great influence on Marcel-Dubois. Like him, she worked intensively and only chose subjects that were musically illiterate: the material thus collected (6,000 documents between 1945 and 1959), thanks to the detailed study of certain musical rituals, allowed her to shed light on ‘vestiges of a musical proto-history’ of the French rural culture, ‘medieval, perhaps ancient, or older’.29 In the 1970s, revivalists pursued their research entirely in the rural dimension.

A reform of the objects, priorities, and places of interest has increasingly led the ethnomusicology of France nowadays to study multicultural types of music and dance (whether they belong to a given community or not), which occur in broadly suburban or urban contexts. Because the modern world is intercultural, a certain form of dynamic anthropology is replacing the old models of classic anthropology (social, cultural, or structural), thereby rearranging the set of questions that form the methodological foundation of the discipline.

Europe, a society essentially based on written traditions, cannot, despite the oral dimension that characterises the study of ethnomusicology, ignore the history and contributions of written sources when dealing with the discipline. This is the reason why I have conducted musico-anthropological historical research into the role of minstrels (ménétriers), who would nowadays be classified as ‘traditional’ musicians, their social organisation, status, the contexts within which they operated, their collective and multifarious practices and their instruments.30 This first round of research was succeeded by a second, more anthropological in nature, which aimed to clarify the history of these musical practices through a structural analysis of their distinctive forms in their evolution through time.31

This global research allowed us to reconstruct the history of this type of traditional and popular music and to understand its progressive marginalisation from the eighteenth century onwards. It also allowed us to decipher its present reality, updated through fifteen years of revivalist ethnomusicological research. Thanks to the historical taxonomy of the forms and functions of this music, which this research has helped to determine, a credible explanation of the role played by traditional music in establishing identity and of the musical choices adopted by the folk-revival movement is now available to us.

The current situation

After two centuries of Romantic pre-history and scientific-institutional history, both academic and revivalist, French ethnomusicology needs, at present, to rethink its themes, goals, and methods of research, and to bring researchers together. Modern issues grappled with by ethnomusicology in France and in other industrialised countries constitute a wide and inexhaustible terrain for research: urban music, regional identities or identities of different communities, changes in aesthetics, modern cultural syncretism, globalisation, women’s emancipation in musical practice, the emergence of new practices, etc. The revivalist movement, already forty-five years old, also constitutes fertile ground for an anthropological study of the process of building or institutionalising a heritage.

Because of its historical depth, its protean nature and its permanent quest for an identity, the ethnomusicology of France has always had to redefine its scientific strategy, but this very need also occurs because of the disappearance of most of its primary research material. Perhaps this experience can be its contribution to global ethnomusicology, which is itself being forced to question its methodology because it is universally confronted with the consequences of contemporary cultural life and globalisation.

Notes

1 (ed.), Musique bretonne: histoire des sonneurs de tradition (Douarnenez: Le Chasse-Marée/ArMen, 1996), 328–57.

2 , and , Les cornemuses de George Sand, autour de Jean Sautivet, fabricant et joueur de musette dans le Berry (1796–1867), exhibition catalogue (Montluçon: Musée des Musiques Populaires de Montluçon, 1996), 28–38.

3 , La tradition de cornemuse en Basse-Auvergne et Sud-Bourbonnais (Moulins: Éditions Ipomée, 1982).

4 and (eds), Souffler, c’est jouer: chabretaires et cornemuses à miroirs en Limousin, exhibition catalogue (Saint-Jouin-de-Milly: FAMDT, 1999).

5 , La cornemuse des Landes de Gascogne (Belin-Béliet: Centre Lapios, 1986).

6 , ‘La bombarde, aux commandes du couple traditionnel des sonerien’, in and (eds), Les hautbois populaires: anches doubles, enjeux multiples (Saint-Jouin-de-Milly: Modal, 2002), 142–3; Jean-Christophe Maillard, ‘Talabarderien mod koz: le jeu et la technique de la bombarde chez les sonneurs bretons de tradition’, in Charles-Dominique and Laurence (eds), Les hautbois populaires, 150–4.

7 Colleu (ed.), Musique bretonne, 343.

8 , ‘Variations sur un même instrument: le hautbois en Bas-Languedoc du XVIIIe au XXe siècles’, Le monde alpin et rhodanien, 1–2 (1993), 85–126.

9 , Chants populaires de la Grande-Lande, ed. and , 2 vols (Paris, 1912; Bordeaux: Éditions Confluences, 1995), vol. I, 397–9.

10 , Fêtes villageoises et vacarmes cérémoniels ou une musique et son contraire (Paris: CNRS, 1975), 604. See also , ‘La paramusique dans le charivari français contemporain’, in and (eds), Le charivari (Paris: École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, 1981), 45–53.

11 , ‘Les bandes ménétrières ou l’institutionnalisation d’une pratique collective de la musique instrumentale, en France, sous l’Ancien Régime’, in (ed.), Entre l’oral et l’écrit: rencontre entre sociétés musicales et musiques traditionnelles, conference proceedings, Gourdon, 20 September 1997 (Toulouse: FAMDT, 1998), 71–4, 79–82.

12 Yves Defrance, ‘Le bagad, une invention bretonne féconde’, in Charles-Dominique and Laurence (eds), Les hautbois populaires, 135–6.

13 World Library of Folk and Primitive Music: France, ed. , Rounder Records 82161–1836–2 (2005).

14 and , ‘La voix méditerranéenne: une identité problématique’, in and (eds), La vocalité dans les pays d’Europe méridionale et dans le bassin méditerranéen, conference proceedings, La Napoule, 2000 (Saint-Jouin-de-Milly: Modal, 2002), 9–14; Jacques Bouët, ‘Une métaphore sonore: chanter à tue-tête au pays de l’Oach (Roumanie)’, in Charles-Dominique and Cler (eds), La vocalité dans les pays d’Europe, 72–5.

15 Example 12.1 is from , Chansons populaires des Pyrénées françaises (Marseilles: Laffitte Reprints, 1998), 324.

16 , La complainte et la plainte: chanson, justice, cultures en Bretagne, XVIe–XVIIIe siècles (Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2010), 175–202.

17 , Le folklore français, vol. I: Du berceau à la tombe: cycles de carnaval–carême et de Pâques (Paris: Laffont, 1998), 582–5.

18 , ‘Le kan ha diskan: à propos d’une technique vocale en Basse-Bretagne’, Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles, 4 (1991), 137–8.

19 Example 12.2 is from Poueigh, Chansons populaires des Pyrénées françaises, 223.

20 Defrance, ‘Le kan ha diskan’, 31.

21 , Chansons et airs populaires du Béarn (Pau: Vignancour, 1844).

22 , ‘De l’art de la broderie chez les violoneux’, Modal, 5 (1986), 17.

23 et , ‘Réhabiliter, repenser, développer l’ethnomusicologie de la France’, Musicologies (Observatoire Musical Français), 4 (2007), 50–1.

25 , ‘L’apport de l’histoire à l’ethnomusicologie de la France’, in and (eds), L’ethnomusicologie de la France: de ‘l’ancienne civilisation paysanne’ à la globalisation, conference proceedings, Nice, 2006 (Paris: L’Harmattan, 2008), 128–9.

26 , Déchiffrer la France: la statistique départementale à l’époque napoléonienne (Paris: Archives Contemporaines, 1988).

27 Cantal: musiques traditionnelles, two audio cassette tapes, ADMD 001–2, held at the Agence des Musiques Traditionnelles d’Auvergne.

28 , ‘La dimension culturelle et identitaire dans l’ethnomusicologie actuelle du domaine français’, Cahiers de musiques traditionnelles, 9 (1996), 280–2.

29 , ‘Ethnomusicologie de la France 1945–1959’, Acta musicologica, 32 (1960), 114.

30 , Les ménétriers français sous l’Ancien Régime (Paris: Klincksieck, 1994).

31 , Musiques savantes, musiques populaires: les symboliques du sonore en France, 1200–1750 (Paris: CNRS, 2006).

13 Popular music

Introduction

For the English speaker especially, understanding French popular music means engaging with the problem of naming it. In French the term populaire in la musique populaire or its plural les musiques populaires has traditionally denoted not ‘popular’ in the sense of enjoyed by a large, sociologically diverse audience, but ‘folk’: the untutored, unwritten, supposedly spontaneous music of the rural and urban working classes. It is only fairly recently, after urbanisation and industrialisation turned French entertainments into commodities disseminated by the mass media, that the English sense of the word has begun to contaminate the French, though the two meanings still exist side by side. This chapter will use ‘popular’ in the English sense and will focus on the development of urban music, in particular song, after very briefly sketching its folk roots.

For centuries, and especially since the Revolution of 1789, there has been a common myth in France that it is not a musical nation. While the present Companion might suggest that this is inaccurate, the myth does at least highlight an inadequacy in French musical culture. While the republican education system set up in the 1880s privileged reason, science, philosophy and the written word over the creative arts, conservatoires were characterised by a deep-seated conservatism and an overemphasis on theory until well after the Second World War.1 To this extent, then, the myth contains a truth. French popular music, however, offers an essential corrective to it, for it has arguably helped foster what has been called a ‘musicalisation’ of French culture.2 With illiteracy endemic in the early nineteenth century, and still at 43.4 per cent of the over-twenties as late as 1872,3 in practice the written word counted for relatively little, whereas singing or the untrained playing of instruments had been virtually universal for untold centuries. It was only as peasants relocated to towns in the nineteenth century that a separation evolved between producers of music (composers, lyricists, singers, musicians, publishers, impresarios) and consumers. It is with this specialisation that French popular music in the modern English sense really begins, though again a different taxonomy has developed in French, at the centre of which lies la chanson, a polysemic category whose meanings are complex, having developed by accretion.

Inventing chanson: from amateur to auteur

The ancient roots of French song are discussed in more detail elsewhere. Briefly, its story begins with the troubadours and trouvères of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, who wrote for the aristocracy, and with vernacular, itinerant street singers called jongleurs. According to Calvet, the term chanson became mainly identified with the latter, that is, with the street.4 Popular song in fact remained a largely anonymous, collective form until the fifteenth century, which saw a burst of creativity in the chanson populaire.5 By this time, the transcribing and anthologising of songs (most famously in the manuscrit de Bayeux) had begun and their forms had become established (lai, rondeau, ballade, etc.). Such works then achieved greater permanence with the invention of printing, which allowed popular lyrics sung to existing melodies (timbres) to be anthologised. This means of circulation remained largely intact until the late nineteenth century, when a number of social, institutional and technological changes professionalised and commodified the chanson.

The Revolution of 1789 is a useful starting point for understanding these changes. In its wake came a concern to foster national unity and educate the people, with the result that the organic growth of popular culture becomes entangled with its ideological manipulation by political and cultural elites. The rediscovery of folk music and the encouragement of amateur music-making throughout the nineteenth century by both religious and secular authorities are cases in point. After the Revolution, regional cultures were despised as repositories of particularism and ignorance. But the Romantic movement’s interest in a rural idyll produced an intellectual and literary concern to preserve folksongs. After Napoleon III seized power in December 1851, he furthered this endeavour by ordering the ministry of instruction publique to survey and collect France’s ‘popular poetry’. Since the songs collected were redrafted in standard grammar and notation to remove all local colour and form a common treasury for educational purposes, these initiatives began a process of transforming an oral tradition into a homogenous written culture.6 One outcome was a new consciousness of song’s place in national cultural memory.

Another important form of voluntarism in popular music was the orphéons. Invented in the 1820s to educate, socialise and improve the morals of the people by offering them a musical apprenticeship and an outlet for collective endeavour, orphéons were initially choral societies of schoolchildren and workers; but increasingly from the mid nineteenth century the term came to mean brass bands (fanfares) or wind bands (harmonies). Although they were primarily individual initiatives by a school, factory or ex-army musician, the orphéons were usually supported by the local mayor, who would authorise outdoor public performances. They were also facilitated from the 1850s by the setting up of outdoor bandstands (kiosques).7 This public support can be explained by the perceived civic and ideological benefits of the orphéons in politically turbulent times. As the official organ of the movement, ‘L’Orphéon’, put it: ‘hearts come very close to agreeing when voices have fraternised’.8

The orphéons were also seen as ramparts against the potentially subversive pursuits that the ‘people’ traditionally engaged in when left to their own devices. In the seventeenth century, the oldest bridge in Paris, the Pont-Neuf, had become notorious for popular songs of sedition, but by the Revolution such dissent was moving indoors. Middle-class singing clubs (sociétés chantantes) had in fact been growing up in Parisian ‘cabarets’ (bars) and comfortable restaurants since the early eighteenth century, being associated especially with topical satire. The first such venture in Paris was Les Dîners du Caveau, set up around 1734. Modelled upon it, caveaux (literally ‘vaults’, but in this context ‘clubs’) sprang up across France, where groups of well-heeled songwriters (known at the time as chansonniers) and other artists would meet to carouse and hear each other’s compositions. These crafted, witty songs were usually more epicurean than subversive; but when the Napoleonic Empire fell and monarchy was restored in 1815, less exclusive, working-class counterparts to the caveaux, known as goguettes, appeared. These were closed, even semi-secret clubs whose members would meet weekly or monthly in a cabaret or wine shop, paying a small subscription to drink heavily and sing their own compositions or the songs of the moment. Although bawdy drinking songs were probably more common there, some goguettes became centres of political opposition, being associated initially with Bonapartism or freemasonry and later with republicanism.9 Flourishing during the July Monarchy (1830–48), over 480 such clubs existed in Paris by 1845.10 Two songwriters were strongly identified with caveaux and goguettes: Pierre-Jean de Béranger (1780–1857), who was famous in both, and the less renowned Émile Debraux (1796–1831), known as the ‘Béranger of the rabble’.11 Both were imprisoned for the politically or morally subversive content of their work.

This dissident, urban subculture was one among several factors in the eventual emergence of a distinctive chanson tradition. In the short term, however, with political tensions following the revolution of 1848 and the start of the Second Empire (1851–70), censorship attempted to restrict the ideas that urban workers had access to. A decree of November 1849 prohibited song performances in cafes without a visa from the ministry of education; another, of March 1852, banned public meetings without police authorisation. As a result, both caveaux and goguettes were effectively closed down, which helped bring about a shift in French popular music from amateur social engagement to professional entertainment.12

Professionalisation was triggered by a legal dispute over songs performed without the composers’ consent in 1850 at the Café des Ambassadeurs near the Place de la Concorde in Paris. The case led to the setting up of the performing rights organisation, the Société des Auteurs, Compositeurs et Éditeurs de Musique (SACEM), the following year. Henceforth, songwriters could contemplate making a living from their work. Indeed, despite the disappearance of the goguettes, demand for songs in cafes remained high. One kind of institution that satisfied it were the intimate cabarets on the outskirts of the city, notably Montmartre. The most illustrious of the Montmartre cabarets was Le Chat Noir (1881), which was frequented by artists, writers and inquisitive bourgeois.13 It was here that the singer-songwriter Aristide Bruant (1851–1925), immortalised by Toulouse-Lautrec, first made his name, before setting up his own establishment on the same premises in 1885, Le Mirliton, when Le Chat moved elsewhere.14 With his characteristic Parisian accent and slang, working-class themes and declamatory delivery (a necessity before the microphone if singers were to be heard above the hubbub of the cabaret), Bruant developed what has become known as the ‘realist song’ (chanson réaliste): a melodramatic narrative of Parisian low life in keeping with the marginality of Montmartre. Like their audiences, cabaret songs were generally more literary than those of the goguettes. This, together with the Toulouse-Lautrec poster and the existence of early recordings of Bruant’s voice on cylinder from 1909, would transform him into a formative legend for twentieth-century chanson.15

Another response to the demand for live music took chanson closer to massification. Street singers, who had traditionally made their living by passing the hat and selling simple sheet music (called petits formats) of the songs they sang, had by the 1840s taken to working outside cafes to maximise income. These establishments, called cafés chantants after a formula dating back to the 1790s but banned under Napoleon, became favourite places of entertainment during the summer months. In 1848, the owner of the Café des Ambassadeurs (where the SACEM was shortly to be conceived) took the arrangements a momentous step forward by hiring singers and musicians, setting up outdoor and indoor stages for the purpose.16 This initiative gave birth to the cafés-concerts of the Second Empire and the Belle Époque, a period of cultural extravagance running from the last decades of the nineteenth century to 1914. Often rather sordid, rowdy locations in the early days, where sailors drank and prostitutes plied their trade,17 the cafés-concerts steadily became ‘the people’s opera house’. Certainly, they were the main form of mass entertainment for urban workers, artisans and petits-bourgeois before cinema.

The part played by the café-concert in the development and commercialisation of French popular music and mass culture is hard to exaggerate. In the goguettes the entertainment had been free of charge (aside from the small membership fee), amateur and participative. But with the hiring of singers and musicians by the cafés-concerts, followed in 1867 by the legalisation of performance in costume in drinking houses, cafes became venues, singing became spectacle, and the population became spectators.18 Commercialisation could only mean depoliticisation if proprietors were to please audiences wanting easy entertainment and the censors at the Inspection des Théâtres, who vetted all songs for performance.19 Jobbing composers, now remunerated by the SACEM, began producing specific repertoires for a range of stock characters, which had become a café-concert convention: comiques-troupiers, diseuses, réalistes-pierreuses and others.20 These repertoires were designed to elicit two principal emotions: laughter and tears.21 Many of the soon-to-be iconic nightspots of Paris like Le Moulin Rouge (1889) began life as cafés-concerts; and the evolution there of public singing as a commodity would in turn give birth to the highly paid national celebrity, starting with Thérésa (1837–1913) and Paulus (1845–1908). Some of their successors would also become France’s first international stars: Yvette Guilbert (1867–1944), another singer immortalised by Toulouse-Lautrec; Mistinguett (1875–1956), whose song ‘Mon homme’ became the model for the American torch song ‘My Man’; and Maurice Chevalier (1888–1972), Mistinguett’s lover on stage as in life and later the professional Frenchman of Hollywood.

Another defining element in urban popular music at the start of the twentieth century was the bal musette. Originally a village dance featuring bagpipes known as a musette, in its modern form it allowed working-class city-dwellers to gather in unsophisticated suburban venues and dance in couples to the accordion. Hollywood was soon to latch onto the accordion as a metonym of Frenchness, though it had in fact originated in Austria, Germany and England before being brought to Paris by migrant Italian musicians. Its portability, its cheapness and the fact that it was always in tune made it the ideal popular instrument for dancing, although – ironically given the iconic status it was to acquire – its arrival in France was resisted by both the church and folk purists, who saw it as a barbarous import.22 But outside influences of far greater magnitude were on the way.

Between approximately 1890 and 1914, the English-style music hall took the France of the café-concert and the bal musette into the modern age. By 1927 there were fifteen halls in Paris alone,23 including the Folies Bergères, Moulin Rouge, Bobino and Olympia. Music hall dispensed with the cafe setting, separated stage and audience, and demoted singers in favour of more varied forms of visual entertainment, from circus to ballet and the saucy, spectacular ‘revues’, which today have become a tourist cliché. Hence the term spectacle de variétés (variety show), which dates from this period and which, reduced to les variétés, has become a synonym for lightweight, commercial forms of chanson.24

A further component in the music-hall mix consisted of exotic dance musics. The tango reached France from South America shortly before the First World War. The cakewalk had arrived at the turn of the century, prefiguring the African-American jazz bands of the American Expeditionary Force in 1917.25 Still absorbing the shock of jazz, French audiences were even more astonished by the black dancer Josephine Baker, who appeared at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in La revue nègre of 1925. Virtually naked on stage, she exploited and subverted the perceived otherness of black America, simultaneously scandalising and arousing male critics.26 Soon, however, she would shape-shift into a more conventional chanson and revue artist, learning French and adopting the conventions of white music hall. Jazz itself, in both its American and Gallicised forms, in fact acquired a special status in France, as successive African-American musicians worked and even settled there (most notably Sidney Bechet) and white French singers and touring bands (Johnny Hess, Ray Ventura and his Collégiens, Grégor and his Grégoriens) appropriated swing in the 1930s. An association of jazz enthusiasts, Le Hot Club de France, was formed in 1932, and its journal Jazz hot, launched in 1935 (and still published on the Web in 2014), became a forum for expert jazz criticism under Hugues Panassié and Charles Delaunay. With their support, the celebrated Quintette du Hot Club de France, featuring Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli, also evolved its own style of French jazz.27

With the music hall of the 1920s showcasing variétés, spectacle and brashly cosmopolitan dance rhythms like jazz, some wondered whether there was any place there for chanson in its accepted form.28 By the late 1930s, however, singers had largely supplanted revue as the main attraction in the halls. As this suggests, a strategy of distinction was emerging which, in opposition to ‘variety’ (variétés), forged an identity for chanson drawing on the older, supposedly more authentically French culture of the goguettes, cabarets and cafés-concerts. Pivotal in this evolution were two historic but very different singers, Édith Piaf and Charles Trenet. Both borrowed from past conventions but, by example, helped shape the future of chanson and indeed its myth: the myth of song as a popular art at which the French excel and which thereby expresses an ineffable Frenchness; the myth in fact of la chanson française.

Singers, songwriters and la chanson française