The compiler of the Capirola anthology was no idealist.Footnote 1 In the remark he penned at the beginning of his precious lute book, meant as a gift for a friend who may have been his student, he showed no faith in the competence of future – or, indeed, present – generations:

Considering, o Vidal, that many divine little works have been lost owing to the ignorance of their owners, and wishing that this almost divine book written by me may be preserved in perpetuity, I wanted to adorn it with such noble paintings that in the event that it fell into the hands of people who lacked understanding, they would preserve it for the beauty of its pictures.Footnote 2

Although speculations on the survival rate of manuscripts are notoriously hard to verify, one suspects that the Capirola compiler was right: the proportion of illuminated manuscripts is probably much higher today than it was in the fifteenth century. In his introduction he clearly qualified this book as a gift, which lends his disclaimer a familiar, somewhat self-deprecatory aspect. It is as if he were distancing himself from the beautiful pictures of monkeys, birds, sheep and other animals (see Figure 1) as a mere means of ensuring the manuscript's survival.

Figure 1. Chicago, Newberry Library, Case MS minus VM 140.C25, fol. 20v. Photo courtesy of the Newberry Library.

That a remarkable portion of the surviving Renaissance musical sources should be presentation manuscripts is hardly surprising – they are beautiful objects, made with rich materials and often splendid decorations, all features which arguably fostered their preservation. One of the smallest and most beautiful of these books, Modena, Biblioteca Estense e Universitaria, MS α.F.9.9 (hereafter ModE) – similar in some respects to the Capirola collection and compiled roughly 15 years before it – stands out not only for its elegance and special decoration, but also for the unique textual apparatus through which its status as a gift is articulated.Footnote 3 As in countless cultures, the exchange of presents was a deep and consequential gesture in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Europe. In general, gift-giving is a voluntary action that creates the obligation of a return, thus starting a chain of events – among other things, establishing or strengthening relationships and affecting people's status.Footnote 4 In the following pages I will add more detail on special ramifications concerning the transmission of music.

ModE is an unusual object in many respects. A small book measuring just 165 × 110 mm, it is the only presentation manuscript of the time containing exclusively Italian vocal secular music, an anomaly to which I shall return. It is also an exceedingly rare collection of settings of a specific genre, the musical strambotto, and perhaps the earliest dated source of the genre that Petrucci would later include under the term ‘frottola’. The date (1496) is derived from the riddle copied in epigraphic script on fol. 6r, which also declares Padua to be the place of origin.Footnote 5 The artefact, however, is best known for its physical features and its exceptional paratext.

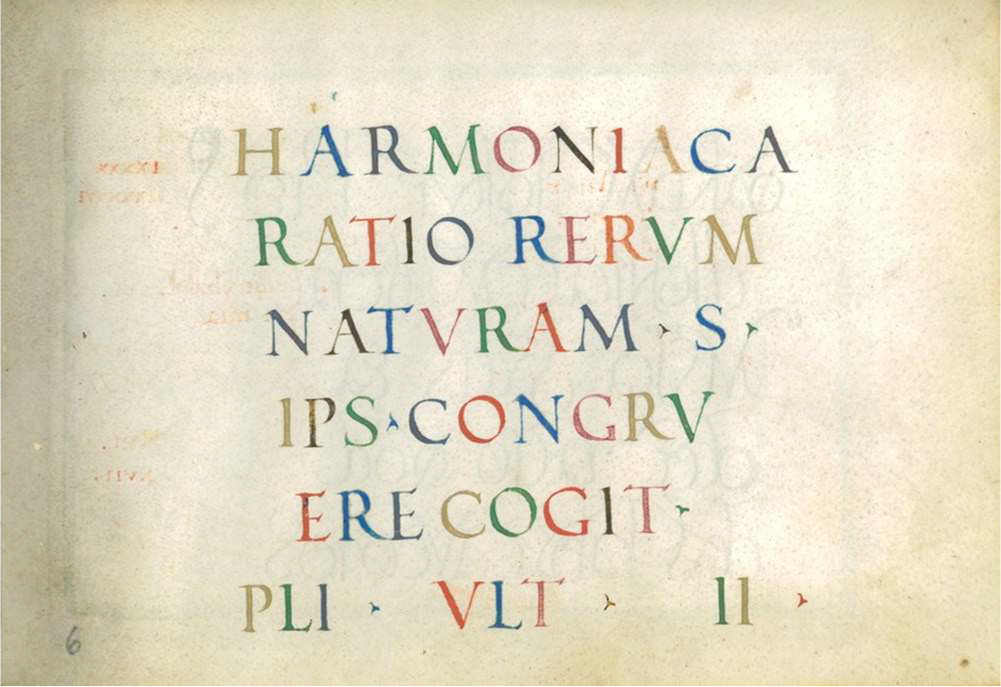

ModE is composed of two sections, the first consisting of eight folios of parchment with dedicatory material and an index, the second originally formed of 104 folios of paper containing 104 musical compositions, four of which are textless and do not appear in the index. Despite the use of paper, the book was produced very elegantly. The music writing is assured and airy, and the poetic text is elegantly copied in different kinds of humanistic calligraphy, with multi-coloured initials decorating every page. Delightful naturalistic reproductions of plants, fruits, birds and insects – added after the music was copied and possibly later than the completion of the manuscript – are present on numerous pages of the second section of the manuscript.Footnote 6 ModE's introductory parchment fascicle is a rare feature among Renaissance music books.Footnote 7 The paratext it contains – copied with great care and imaginative graphic solutions – features classical citations in Latin and in Italian translation in praise of music, including Isidore of Seville's Etymologies, 3:17 (fol. 2v) and Pliny the Elder's Natural History, 2:113 (fol. 6r; see Figure 2), as well as an index (fols. 3v–5v) and a dedicatory sonnet (fol. 7r) in which the muses address the recipient, Franciscus, on behalf of the donor, Johannes.Footnote 8

Figure 2. Modena, Biblioteca Estense e Universitaria, MS α.F.9.9, fol. 6r. By kind permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo, Italy.

In this article, I examine the nature and symbolic value of this very special manuscript in its context. After surveying the meaning and practice of the giving of music in the milieu of late fifteenth-century Italian intellectual circles, I compare the musical and poetic contents of ModE with those of similar coeval collections, and suggest that the manuscript originated in the environment of Padua Cathedral. Its luscious appearance does not indicate that the manuscript originated in a courtly environment; rather, I propose that ModE was meant to dignify the singing of strambotti, a pastime presumably shared by Giovanni and Francesco but involving a repertory that did not normally convey enough of a sense of prestige to constitute a gift. As I claim, the emphasis on the performative aspects adopted by Johannes, the probable compiler of the manuscript, represented an original, if short-lived, approach to music before authorship became the dominant and classicizing marker of cultural value during the sixteenth century.

Music as a ‘present for the mind’ in late fifteenth-century Italy

In an engrossing monograph, Natalie Zemon Davis has documented the crucial importance of gift exchanges in sixteenth-century France; her study is especially useful in the present context because many of her insightful remarks can be applied more generally to the whole culture of the Renaissance. Zemon Davis underlines the pervasiveness of this model of exchange even in money-based economies such as those current in early-modern Europe, as well as the importance of what she calls ‘gift rhetoric’ in all sorts of exchanges. Then as now, gifts celebrated special times of the year, accompanied rites of passage or reflected social obligations and expectations.Footnote 9

This rhetoric is beautifully exemplified in Erasmus of Rotterdam's letter of 1515 to his friend Pieter Gillis, in which the Dutch humanist highlights the central implications of gift-giving in a learned Renaissance environment. The letter figured as the preface to the Parabolae sive similia:

Friends of the commonplace and homespun sort, my open-hearted Pieter, have their idea of relationship, like their whole lives, attached to material things; and if ever they have to face a separation, they favour a frequent exchange of rings, knives, caps and other tokens of the kind, for fear that their affection may cool when intercourse is interrupted. […] But you and I, whose idea of friendship rests wholly in a meeting of minds and the enjoyment of studies in common, might well greet one another from time to time with presents for the mind and keepsakes of a literary description. […] Our aim would be that any loss due to separation in the actual enjoyment of our friendship should be made good, not without interest, by tokens of this literary kind. And so I send a present – no common present, for you are no common friend, but many jewels in one small book.Footnote 10

Erasmus's rhetorical gesture is evident. His book is a ‘present for the mind’ that sets him and Pieter apart from those more ordinary people who exchange tangible signs of their relationship. Instead, Erasmus's book functions as a keepsake that underlines the spiritual affinity of the two exceptional men and their common citizenship in the republic of letters.

If we move south from Erasmus's England, we realize at once that the importance of ceremonial gift exchanges in Italian intellectual centres like Padua, Venice and Florence cannot be overestimated. Because in these as in many other Renaissance centres rank was not completely predetermined, the ability to manage personal relationships skilfully was key to the pursuit of honour and ultimately to success. The early Medici regime is a good example. The banking family effectively controlled the Republic of Florence for most of the fifteenth century without destroying the façade of its institutions. This was achieved through a dense network of exchanges, favours and recommendations – in short, of clientship – whose obligatory character Cosimo the Elder, Piero and Lorenzo carefully exploited to gain and consolidate their family power. One needs only to open the edition of Lorenzo's letters or his protocol registers to understand the power management that took place at the Palazzo Medici.Footnote 11

Lorenzo de’ Medici received numerous gifts from various people or institutions, for which his secretaries sent due thanks.Footnote 12 The Florentine aristocrat also donated and received music, a favourite token of exchange among Italian Renaissance leaders.Footnote 13 A case of musical gift exchange especially relevant here involved Lorenzo de’ Medici and Girolamo Donà, the Venetian ambassador to the papal court. Lorenzo sent Donà a songbook with compositions by Heinrich Isaac – a gift discussed in more detail below. In their correspondence, the two Italians articulate some of the points found in Erasmus's letter to Gillis, in one of the earliest attempts at redefining the exchange of music as a ‘present for the mind’ and a ‘token of a literary kind’, like Erasmus's later Parabolae.

And indeed, music fulfilled a number of functions both for special occasions and in the everyday life of the European aristocracy. It provided a sounding symbol of wealth and power. The ubiquitous wind ensembles that accompanied rulers and elected officials of important cities served to highlight their military and political status, as did the ceremonial motets composed on occasions such as investitures and coronations.Footnote 14 Polyphonic Masses were often performed in memory of the dead, but in the eyes of the living they also represented a gesture of private and collective devotion, as did prayers and motets.Footnote 15 Even private music-making would display the host's refined taste to the distinguished few admitted beyond closed doors. These kinds of performances would feature the most recent or celebrated among the compositions belonging to the international repertory – such as the French chansons so common in lavish manuscripts from all over Europe – or to various local secular traditions.

The ceremonial and entertainment value of art music was highly underscored in narratives, literary works and iconography throughout the Middle Ages. Renaissance scholars, however, newly articulated the philosophical and ethical aspects of music-making; in particular, educators such as Pier Paolo Vergerio and Guarino Veronese embraced music in their pedagogical plans in the early fifteenth century not for the abstract properties that had long made it part of the quadrivium, but for very practical reasons. On the authority of Aristotle's Politics, they made it part of the curriculum for young nobles, declaring (in the words of Vergerio) that ‘it will certainly not be inappropriate [for them] to relax with song and stringed instruments’.Footnote 16 Although a fair number of religious leaders and lay people expressed strong positions against polyphonic music, by the end of the century, music-making was gaining general acceptance among Italian aristocrats as a worthy leisure activity, a fact that would be prominently sanctioned a few decades later in Baldassarre Castiglione's Book of the Courtier.Footnote 17

In light of the respect paid to music (whether for liturgical, ceremonial and political functions or for private recreation), its use as a gift should not surprise. Indeed, many Renaissance musical gifts survive in the form of beautiful manuscripts, most of which can be recognized because of the splendour of their manufacture and the symbolic elements hidden in their decoration or in the music itself – most commonly the receiver's coat of arms illuminated in the initials of the first opening.Footnote 18 The proper rituals of giving, however, were generally carried out around the manuscript rather than inside it. There might be a special occasion during which the object would be formally offered and gratefully accepted, or there might be an exchange of correspondence creating the same kind of narrative of presentation.

This type of narrative is well exemplified through the epistolary exchange mentioned above between Lorenzo de’ Medici and Girolamo Donà. In the spring of 1491, the latter asked the Florentine ambassador Pietro Alamanni to petition Lorenzo for music by Isaac, the most celebrated composer then active in Florence.Footnote 19 Lorenzo replied to Alamanni:

Thank the Magnificent Venetian ambassador for having requested these songs of me, because I count it a favour to have been so requested by his Magnificence, to whom, because of his virtues and learning, I am much obliged and whom I hold in affection, and also because I know that I am much loved by his Magnificence, to whom commend me. And I am putting the aforesaid songs in order and shall send them to you quickly, I believe by the first post. If I knew what kinds he likes best, I could have served him better, because Arrigo Isaac, their composer, has made them in different ways, both grave and sweet, and also capricious and artful. I shall send a selection of everything, and after he has tasted it I shall know better what wine I shall need to serve.Footnote 20

Evidently the dispatch arrived promptly, because on 17 July Donà sent a most eloquent note of thanks:

Excellent sir, all are in your debt who love letters, who love noble manners, and in a word who love the virtues. But I am now bound to you by a tighter bond. I have received a book, or rather a large volume of music by our favourite Henricus Isaac, most eminent in that art, whose compositions have always given me wondrous pleasure; whenever it is time for music (which it is every day), there is nothing I more like to hear. In that volume I was able to take pleasure in every form of the art. How capable Henricus is in each one anybody with even an elementary knowledge can easily perceive. I wonder at that cheerful generosity of yours, I revere it, and I am grateful for it. Any leisure I have I gladly devote to music; the art is noble and gentlemanly enough in itself and has commonly been praised even by the ignorant. There are some who pursue it to make their names, others by custom, others for other reasons; and therefore only in a very few is it refined and polished. But to me the fruits of that art seem not so much pleasant as useful. For others it [induces?] sleep, it lightens my graver cares, it drives out sordid ones. I omit that it is an excellent gift of nature and so to speak the model of our mind.Footnote 21

The dominant feature of this narrative is the value of music in general and Isaac's compositions in particular. The manuscript Lorenzo sent to Donà is now lost, but one can imagine the selection of ‘songs’ from contemporaneous Florentine sources such as FlorBN 229. This manuscript contains a treasure trove of Isaac's music, including French songs such as He, logierons nous (fols. 1v–2r) and Mon pere m'a donne mari (fols. 3v–4r), Italian compositions such as the quodlibet Donna di dentro (fols. 154v–156r), and even isolated sections of Masses, such as the Benedictus from his Missa Quant j'ay au cueur (fols. 9v–10r), all in alternation with pieces by Johannes Martini.Footnote 22 Lorenzo categorizes Isaac's songs by drawing attention to the variety of compositional styles and through this critique equates the creation of music and literature – a most unusual gesture at the time. This emphasis seems to echo the contemporaneous reflections of Angelo Poliziano on classical and modern literature and his formulation of the rhetoric of docta varietas in his Miscellanea.Footnote 23 Donà expresses appreciation for the gift, mentioning the variety and the high quality of the compositions.

Without discounting both men's sincere love of music, the correspondence is hardly free from posturing. Donà clarifies, perhaps a little defensively, that he practises the art of sounds for the right reasons, that is, as an honest recreation and not out of habit or to become famous. In Lorenzo's case, the emphasis – with the extraordinarily effective metaphor of the sommelier – is on his high connoisseurship and his full access to the bountiful trove of Isaac's compositions. Indeed, in this context Isaac's authorship works as a powerful ‘literary’ validation of Lorenzo's collection. As mentioned, presentation manuscripts are largely distinguished by the use of precious materials and decoration, but nothing of the sort is mentioned by Lorenzo or Donà in their exchange.Footnote 24 Rather, both seem to conform to Erasmus's view of the ‘present for the mind’. What makes the manuscript worthy, according to both letters, is the enjoyment that can be derived from the everyday practice of music, and more specifically the compositional value of the music contained in it, its novelty, and the fact that it was composed by Isaac. Very significantly, Donà describes it as ‘a large volume of music by our favourite Henricus Isaac, most eminent in that art, whose compositions have always given me wondrous pleasure’. If the anthology really contained only compositions by the Flemish master it would be an almost unique case in the history of music before 1500. Single-author music collections are exceedingly rare before Ottaviano Petrucci's successful monographic Mass Ordinary prints of 1502–15.Footnote 25 This detail alone reveals how this correspondence is at the forefront of the integration of Renaissance humanism and music, in which the latter is treated as a decidedly authorial art akin to literature.

A similar attitude is found in the introduction to the Capirola manuscript discussed at the beginning of this article. The compiler of this lute book was aware that not everyone could understand the true gift – that is, its repertory. After discussing the role of the images, his introduction continues:

And certainly the things notated in this book contain in themselves as much harmony as the musical art can express, as he who will peruse it with diligence will openly realize. [The book] even more deserves to be preserved because many of the things found in it have been entrusted by their author to me only.Footnote 26

As a gloss to this statement, he (and subsequent owners, apparently) commented on the pieces in the index: ‘[Part] of a Mass. Beautiful.’; ‘Part of a Mass, and more beautiful’; ‘Part of a Mass, beautiful, and beautiful’, to which a different hand added ‘delomo arme’. And so forth, in a string of Bello bellissimo bellissimissimo.Footnote 27

A gift of strambotti

To return now to the primary object of this study, the songbook ModE also reflects a learned enterprise, yet its compiler framed his gift narrative in a completely different way. If Lorenzo was putting together a manuscript of songs by one of the most celebrated living composers, the compiler of ModE faced a remarkable challenge – his gift was a collection of Italian secular compositions belonging to a genre with very little literary prestige, the strambotto. As already explained, in the Paduan manuscript the presentation ritual is carried out by way of the special vellum fascicle bound at the beginning of the manuscript. In contrast with Lorenzo de’ Medici's taxonomy of Isaac's songs and his posture as wine connoisseur, ModE's praises of music from ancient authors are inevitably formulated in non-technical terms and emphasize the practice of music rather than its composers or artistic dignity. This is reinforced by the dedicatory sonnet, copied in coloured inks, in which the ‘Pierians of Magister Johannes’ – that is, the muses of the donor and compiler – address Franciscus, the receiver of the gift (see Figure 3):

Pierides M(agistri) Io(hannis) ad Fran(ciscum) de Fa(ci) Alumn(um) s(uum)

Figure 3. Modena, Biblioteca Estense e Universitaria, MS α.F.9.9, fol. 7r. By kind permission of the Ministero dei Beni e delle Attività Culturali e del Turismo, Italy.

(The Pierians of Magister Johannes to Franciscus de Faci his student

Since you were not slow to revere us, nor to honour our sacred font – on the contrary, you wanted to commit to our worship from the beginning. Receive this, so you will be rewarded for the heavy thinking and the sweat, for the steps and time that you used up, and for all the hours that you spent visiting us under rain and wind. This sacred book, woven in your name, you will take with its tempered notes to the green hills and among the rivers. But beware – you will have only the use of it and after you fly to Heaven it will freely return to whence it came.)

As is clear from the first eight lines, Franciscus receives the book as a prize for persistently attending the service of the muses in spite of effort and adverse weather. The poetic text is of very modest literary quality, so one should not over-interpret individual words; yet it seems clear that the book has been put together for Franciscus (‘woven in your name’) and is probably defined as ‘sacred’ because it comes from the muses, rather than because of its content. Indeed, its recreational value is clear from the exhortation to bring it ‘to the green hills and among the rivers’. The enjoyment of the gift, however, should not be a lonely one, as the motto pasted on fol. 1v declares: ‘For our solace and that of our friends’.Footnote 28

This motto seems to reveal the ultimate meaning of the gift, which resonates with both Erasmus's and Donà's letters – the shared enjoyment of art, be it literature or music. In the case of ModE, sharing may have happened in a more literal sense than for Erasmus and Lorenzo. Silvia Fumian has proposed the cathedral of Padua as the environment in which ModE was created, and has identified the donor and recipient respectively as Giovanni Francesco da Vaccarino – who taught music at the cathedral school in 1492 – and Francesco de Fazi, a young and very promising jurist who was also on his way to becoming a prelate.Footnote 29 A few factors seem to support these identifications. The one unattributed citation in the initial fascicle (fol. 6v) has recently been recognized as a passage from Gaffurio's Theorica musicae, a text published only four years before the compilation of ModE, and this seems to point to an environment at least contiguous with professional music-making.Footnote 30

Circumstantial evidence can also be found in the main body of the manuscript. The most apparent corroboration is the last strambotto, Crispin van Stappen's farewell to the Padua Cathedral choir. Crispin (c.1465–1532) was master of the choirboys in 1492 and again in 1498, a singer in the papal chapel after 1492, and generally an elite musician. His text reads:

(Farewell, holy choir of Padua and you, wise shepherd with your flock. Farewell, golden shining Padua, with your divine school and sacred laws. Farewell, each of my works and you, sweet schoolboys without a guide. Farewell, each of you, great or small: Crispin leaves and goes on his way.)

Giovanni da Vaccarino was one of the students of Crispin cited in this composition. He temporarily succeeded his teacher in the position and eventually became master of the choirboys from 1499 to 1510. The presence of this attributed strambotto and of an Ave verum corpus also with an explicit attribution to Crispin (fols. 65v–66r) has rightly been read as corroboration of the Paduan origin of the collection. However, the fact that a Netherlandish composer would dedicate a musical strambotto to his students may also suggest that he was embracing a genre that was current in the musical community of the cathedral. To be sure, the position of the piece at the end of ModE bears witness to the standing of Crispin in Padua a few years after his first departure in 1492.

Another suggestive feature of the Paduan manuscript is the number of devotional pieces and of texts that cite liturgical Latin often in a humorous or ironic context. Examples include Alta regina, a te piangendo vegno (fols. 39v–40r), Ave verum corpus (fols. 65v–66r), Circumdederunt me gemitus mortis (fol. 17v), Fora, fora, fora, ingrata (fols. 52v–53r), Miserere mei (fol. 9r), Quem queritis (lost, but listed in index), Requiescat in pace (also lost) and Summa virtù, divina potentia (fol. 66v). Knowledge of liturgical Latin, of course, was hardly limited to people associated with cathedrals, but the concentration in ModE seems significant enough to make this at least an interesting clue. One can imagine that people in the orbit of Padua Cathedral would respond both to the humorous puns and to the devotional texts. At any rate, the Isaac manuscript and the Paduan strambotto collection were musical gifts of a very different kind.

In fact, one could stretch the contrast between Lorenzo de’ Medici and Giovanni da Vaccarino even further, and claim that the Paduan manuscript is really an anti-authorial collection. Among its 104 songs, almost no composer is mentioned in the various poems in the paratext or in the index on fols. 3v–5v. Only one international musician (Crispin) is credited in the main body of the manuscript, along with a few composers active in the Veneto, such as the mysterious Giovanni Brocco – author of Mai più serà (fols. 44v–45r), a textless piece (fols. 70v–71r) and Se me abandoni (fols. 71v–72r); and Franciscus Venetus (Francesco d'Ana or Dana, c.1460–1502), to whom La luce de questi occhi (fols. 13v–14r) is explicitly attributed.Footnote 31 Admittedly, this is hardly the only Italian secular manuscript yielding few attributions – the aura of musical authorship was in no way as engrained a concept among musicians as the literary auctoritas that delighted Renaissance erudites. Yet if attributions in secular Italian collections are often sparse, the almost complete absence of references to composers in ModE becomes odd in its specific context, preceded as it is by hallowed graphic elements pointing to ancient Rome and explicitly attributed classical quotations in the initial fascicle. It is as if, while they were praising music, the Great Men populating the paratext – Pliny, Isidore of Seville and the enigmatic Olympians – devalued by comparison the main contents of the manuscript, which are largely anonymous and uncomplicated songs. Indeed, one suspects that such an august introduction could become a rhetorically inappropriate gesture for a vernacular collection. Surely, wrapping a humble gift in a precious package would only make it more disappointing. But perhaps emphasizing authorship and assimilating music to literature as Lorenzo de’ Medici did was not the only way to confer cultural value on music. Other strategies were possible, but before examining them it will be useful to describe the special connotations conveyed by the poetic and musical genres in ModE.

Strambotti and music

Apart from its paratext, ModE is exceptional for its choice of poetic forms. Even on the basis of a cursory examination, the almost exclusive use of the strambotto stands out. The strambotto – a series of four couplets of 11-syllable lines with alternate rhymes (AB AB AB AB or AB AB AB CC)Footnote 32 – often appears in contemporary collections of Italian secular music, but it is never granted the same centrality. Indeed, as many as 98 of the 104 compositions in ModE are strambotti,Footnote 33 a concentration not observed in any other musical source. Although specific interest in the strambotto is documented in Neapolitan and Florentine musical collections from the 1480s and early 1490s,Footnote 34 Magister Johannes appears unique in his almost obsessive focus on this poetic form. To a different degree, other sources compiled in the decade after ModE reveal that a keen (if not quite as besetting an) interest in the genre existed in northern Italy. As Table 1 shows, strambotti constitute roughly 50% of the compositions in three collections – Milan, Biblioteca Trivulziana e Archivio Storico Civico (Castello Sforzesco), MS 55 (olim I 107; hereafter MilT 55), probably compiled, like ModE, in the Veneto; the Mantuan source Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Département de la Musique, Fonds du Conservatoire, MS Rés. Vm7 676 (hereafter ParisBNC 676); and Ottaviano Petrucci's fourth book of frottole of 1505, significantly entitled Strambotti, ode, frottole, sonetti et modo de cantar versi latini e capituli (hereafter Pe1505).Footnote 35 After this time, the proportion of strambotti in musical collections seems to decrease to roughly 10%.Footnote 36 It is difficult to offer a comprehensive explanation, as any number of parameters may have contributed to this trend, including the taste of individual collectors, specific geographical predilections and the availability of musical material. The fondness for musical strambotti at the turn of the sixteenth century, however, appears to occur mostly in northern Italian sources, and ModE is the most exclusive and representative testimony of the phenomenon.

TABLE 1 Strambotti in Selected Frottola Collections

| Source | Total no. of compositions | Total no. of strambotti | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| ModE | 104 | 86–98 | 1496 |

| MilT 55 | 64 | 41 | c.1500 |

| ParisBNC 676 | 69 | 33 | 1502 |

| Pe1505 | 91 | 47 | 1505 |

The other contextual aspect emerges when one aligns the data on attributions and source distribution with the musical style of the settings. Strambotti are part of the composite archipelago of Italian vernacular music that Petrucci labelled ‘frottola’ in his prints, probably after the poetic frottola or barzelletta most commonly set in these songs. These euphonious and uncomplicated compositions are not noted for a tight relationship between text and music – barring remarkable exceptions, their composers strove to provide a pleasant and efficient aural decoration for a given poetic text or metre without undertaking the interpretative endeavours that would distinguish the later madrigal. This important aspect is linked to the strophic nature of many frottole, in which the same music is reused for the refrain and the different stanzas, and thus needs to be generic enough somehow to fit all of them. The most common metre – the barzelletta – involves a poetic distinction between the refrain and the stanzas, but the difference is often not underlined by the music, since they are commonly set to the same melody. The strambotto is even more economical. In the most common settings, music is provided only for the first couplet, with a cadence between the first and second lines, and occasionally further subdivisions. This melody is repeated indefinitely, and could set two 11-syllable lines, a single strambotto or the whole of Ludovico Ariosto's Orlando furioso.Footnote 37

The generic character of the musical strambotto is evident in virtually every composition copied in ModE. Gridan vostri ochi, on a text by the celebrated poet Serafino Ciminelli Aquilano (1466–1500), is an especially instructive case in which the poetry itself is as modular as the music. The poem develops the age-old allegory of love as war by playing on repeated specific words at the end of each line in a way that is meant to evoke the chaotic atmosphere of a battle:

| Gridan vostri ochi al cor mio ‘fora fora!’ | A |

| c'ha le difese sue sì corte corte; | B |

| ‘su suso, a saco a saco, mora mora, | A |

| arda arda, fredo fredo, forte forte!’ | B |

| Io pian pian dico dico allora allora | A |

| ‘vien vieni, acurri acurri, o Morte Morte!’, | B |

| e grido grido alto alto or muto muto | C |

| ‘acqua acqua, al foco al foco, aiuto aiuto!’ | C |

(Your eyes scream to my heart, ‘out out!’, since its defences fall so short, short; ‘go go, sack sack, die die, burn burn, cold cold, strong strong!’ I then then say say softly softly: ‘Come come, rush rush, o Death Death!’ and scream scream loudly loudly or quietly quietly: ‘Water water, fire fire, help help!’Footnote 38)

This is one of the instances in which the generic musical setting (see Example 1) fits the poetry very well. Indeed, almost all the lines follow a fairly regular trochaic pattern after an initial proparoxytone gesture (‘c'HA le di-FE-se SUE sì COR-te COR-te’). The poetic expedient of the repeated words for intensive effect allows for an agreeable contrast between syllabic settings (Example 1, bars 12, 24–5) and long melismas preparing the cadences (13–16, 26–31). Finally, the four couplets develop a continuous narrative, without any particular break.

Example 1. Gridan vostri ochi. Modena, Biblioteca Estense e Universitaria, MS α.F.9.9, fol. 19v.

In most strambotto texts, however, the 11-syllable lines observe very dynamic and changeable patterns of accents. Therefore, the musical intonation – whose accentual system is necessarily rigid – will generally fit the first couplet but seldom work as well with the others.Footnote 39 Given the largely homophonic character of these settings, it is fair to surmise that performers preserved the prosody by emphasizing the textual accents over musical rhythm, but the problem is symptomatic of the general lack of compositional concern for the text. In fact, one could even claim that the most common musical setting of a strambotto denies its larger poetic structure. The strambotto toscano includes three AB couplets, but closes with a CC rhyme. The difference is often exploited rhetorically, but is completely lost in most musical settings, which dictate exactly the same music for the last couplet as for the previous ones (thus treating it as a Sicilian ottava: AB AB AB AB).

All of the strambotti in ModE are set, like Gridan vostri ochi, with music for one couplet to be repeated four times. The same is true for many of the settings in the slightly later manuscripts MilT 55 and ParisBNC 676. These sources and compositions are too few to lead to thorough hypotheses, but they could perhaps represent a particular phase of strambotto settings in which composers adhered to a very basic model regardless of their ability. This approach of providing music for only the first couplet somehow became a stylistic mark, as shown by Crispin's Vale vale de Padua (fol. 80v), the last setting in ModE. Crispin possessed superior training and perfect control of international compositional techniques, yet this song of his is undistinguishable from the others in ModE. Vale vale de Padua, obviously, was an attempt not at showcasing his musical skills, but at engaging with a specific musical language.

Evidence of a different compositional approach to the genre is reflected in Petrucci's fourth book of frottole. Its first two gatherings (see Table 2) contain pieces that break the received couplet-based mould, such as Bartolomeo Tromboncino's Deus in adiutorium meum intende and the anonymous Del tuo bel volto amor fatt'ha una rocha – both setting two couplets – as well as A che affliggi el tuo servo, with new music for each of the four couplets. Occhi mei lassi by Cara is also through-composed.Footnote 40 It may be no accident that this original – dare we say authorial? – treatment of the subgenre is associated with two of the most important vernacular composers and is featured so prominently in Petrucci's collection. Musical authorship was one of the printer's concerns, as is obvious both from the richness of attributions in his publications and from his de facto invention of the single-author musical anthology.Footnote 41 One can see how this authorial approach would work in the publishing world of early sixteenth-century Venice, where the works of the Latin, Greek and Italian classics were being eagerly printed. One could also claim that the compiler of the Paduan manuscript pursued a complementary agenda, in keeping with the tone of its paratext, shaped as it was by the citations and the visual elements in the first gathering.

TABLE 2 Strambotto Settings in the First Two Gatherings of PE1505

| Fol(s). | Incipit | Composer | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2r | Io son locel che sopra i rami doro | Marco Cara | first couplet set |

| 8r | Morte te prego che de tanti affanni | B.T. | first couplet set |

| 9r | Vana speranza mia che mai non uene | Philippus L. | first couplet set |

| 9v | Deus in adiutorium meum intende | B.T. | first two couplets set |

| 10r | Non fu si crudo el departir de Enea | Anon. | first couplet set |

| 10v–11r | A che affliggi el tuo servo alma gentile | B.T. | through-composed, repeat sign |

| 11v–12r | Occhi mei lassi poi che perso haueti | M.C. | through-composed |

| 12v | Si suaue mi par el mio dolore | Anon. | first couplet set |

| 13r | Del tuo bel volto amor fatt'ha una rocha | Anon. | first two couplets set |

| 13v | Vedo sdegnato Amor crudel e fiero | F.V. | first couplet set |

| 15r | O caldi mei suspiri fidi compagni | M.C. | first couplet set |

| 15v | Lassa el ciecho dolor che te transporta | Anon. | first couplet set |

| 16v | Tu mhai priuato de riposo e pace | Anon. | first couplet set |

In all the choices he made for his manuscript, Vaccarino programmatically underscored the performative aspect of music rather than its authorial distinction. This is evident in the citations at the beginning of the manuscript, which praise music as an activity rather than as an aesthetic object. The almost complete lack of attributions in the collection may be linked either to the compiler's lack of interest or to the modality of transmission of this repertory – both scenarios would strongly suggest a very open concept of the works selected. It is perfectly possible that strambotti of the more elaborate kind published later in Petrucci's fourth book were not available to him, but one should not discard the possibility that Giovanni was especially interested in the most ‘minimalistic’ kind of setting, in a more formulaic conception of the strambotto. If this was the case, he was hardly alone.

William Prizer and others have investigated the links between this vernacular repertory and the so-called unwritten tradition – the repertory of improvised music so fashionable in the fifteenth century among the Italian leading class. Philologists have also pointed out that to this day the strambotto belongs within a tradition at the crossroads between improvised, popular poetry and high-culture literary endeavours.Footnote 42 It would be problematic to maintain that a continuity exists between fifteenth-century improvised strambotti and the stock melodies now used in central Italy, or to suggest that the compositions in ModE were faithful transcriptions of improvised practices. However, by virtue of its complex literary and musical overtones, the strambotto provided aristocratic amateurs with an ideal medium, which they could enjoy as a simplified modality of improvisation. While we lack specific information on unwritten performance practices, it is easy to speculate that skilled singers might vary the iterations of the melody by adding embellishments, and certainly had to modify the accentuation of the music to adjust it to the different patterns of new couplets. Celebrated improvvisatori like Aquilano – the most famous composer and singer of strambotti – contributed to furthering the genre as a viable performance medium. The well-known coeval description by Vincenzo Calmeta significantly emphasizes the intensity of Aquilano's performance and his attention to the word–music relationship: ‘In reciting his poems he was so ardent, and he wove words and music together with such flair that it equally moved the soul of the listeners, be they learned, ordinary, plebeian, or women.’Footnote 43 In this context, the musical features of the single-couplet setting became valuable as an improvisational gesture and a direct cue to the sound of improvisation. This almost paradoxical quality of the strambotto melodies preserved in ModE, then, grants it a definite place in the system of Renaissance musical learning.

Classical learning and music

Music enjoyed high status in the Italian system of fifteenth-century learning, but the musical masterpieces of the ancient past – unlike those in the visual arts and architecture – were unfortunately lost. People of the Renaissance could thus only stand in awe of, and recount over and over, the ancient musical topoi, powerful images – like the stories of Timotheus, Arion and Orpheus – which spoke eloquently of the reverence the ancients had for the art.Footnote 44 Yet these inspiring narratives were akin to snippets of silent films. One could almost see cheeks blowing, fingers plucking the strings and beasts miraculously tamed; lips moving and sailors silently plunging into the sea – all without the privilege of personally experiencing the powerful charms of the aulos, the lyre or the song of the sirens. The only solution fifteenth-century men and women found was to fill the silence of history with new sounds.

This was a cultural world in which the imitation of and the dialogue with classical models dominated important aspects of literature, painting, sculpture, architecture and even science. Ancient music therefore could not be ignored, but viable musical gestures had to be created from scratch.Footnote 45 Approaches varied and for some time no single one prevailed. Instead, different groups of intellectuals tackled the issue in different ways, ranging from describing normal performances in suggestive terms to attempting ambitious archaeological reconstructions of aspects of ancient music.

At the most basic level, any musical performance could be described in strongly classicizing terms, emphasizing the act of music-making as a parallel with the ancient world rather than the actual features of the music. For example, in a letter of 1424 Guarino Veronese described musicians who pleased the senses so much that they seemed to be trained at the school of Timotheus, the legendary aulete whose music could push Alexander the Great into action or charm him again into repose.Footnote 46 The musicians whom Veronese heard probably sang and played vocal and instrumental polyphony – a sound radically different from that to which Alexander listened. But this did not matter in the context, since the classical framing of the narrative was sufficient to endow the musical event with a suitable learned aura.

A more powerful statement could be made by performing modern music that suggested the ancient culture or ancient practices through its texts, genre or arrangement. Such works include compositions that set classical texts, such as the very different settings of Dulces exsuviae (an excerpt from the fourth book of Virgil's Aeneid) by Cara and by Josquin des Prez and the numerous motets on newly composed texts in hexameters or in strongly classicizing Latin. Examples from the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries are hardly limited to Italy – one can cite the experiments of Conrad Celtis and Petrus Tritonius in the German-speaking lands.Footnote 47 The practice must have been successful enough, since Petrucci decided to include an aere per cantar versi latini in his fourth book of frottole.Footnote 48 A parallel gesture relied not so much on the text, which could be in the vernacular, but on the character of the music itself, which made reference to the rhapsodic improvisation and accompanied solo voice found in ancient descriptions. Whether or not the tradition was classically inspired to begin with, Italian improvisers like Aurelio Brandolini or Pietrobono of Ferrara obviously took full advantage of these models.Footnote 49 A few intellectuals pushed the search for classically inspired music further, by engaging in archaeological musical practices. In addition to performing ancient texts, they tried to reproduce key concepts of ancient practices, such as quantitative poetry (a special modal system codified in ancient treatises), or an explicitly evocative setup for performance. Examples include Marsilio Ficino's demonic song in Florence, and Jean-Antoine Baïf's musique mesurée à l'antique.Footnote 50

In light of these observations, it seems clear that Vaccarino compiled ModE as an attempt to promote the cultural value of the musical strambotto. He prefaced his collection with the initial narrative, obviously posed to provide a powerful classicizing framework. The quotations from Isidore, Pliny and Gaffurio all address the value of the practice of music as an activity, regardless of its artistic or authorial value. His obsession with strambotti probably reflected a more widespread northern Italian practice – as the attributions to composers born or active in the Veneto suggest – as well as a pastime that he and Francesco de Fazi probably had in common. The strambotto, however – both as a literary genre and because of its musical style – offered a cultural surplus through its roots in improvisation, which in turn allowed one to recontextualize it imaginatively with reference to the ancient world.Footnote 51

There is no evidence that different interpretations of classicizing music engendered a competition. Different solutions were acceptable in different circles, in which the relationship between learning and music was variously interpreted, making ModE a precious witness of musical culture in late fifteenth-century Italy. The dedicatory sonnet explicitly greets Fazi as a tireless lover of the arts and of music in particular. The instruction to return the book at his death – contained in the last tercet of the same sonnet – concords with the initial epigraph ‘For our solace and that of our friends’ and clearly points to the existence of a group of people, presumably gravitating around Padua Cathedral, who regularly engaged in the singing of musical strambotti. In compiling this special gift for his student, then, Vaccarino created a medium through which a recent genre could be ennobled in its own terms, and an object in which Pliny, Isidore and the humble strambotto could peacefully coexist within the same binding for over 500 years.