Introduction

The history of political parties is also a history of political communication. Throughout the development of political parties, technological opportunity structures have shaped the ways in which parties communicate with citizens (Farrell and Webb, Reference Farrell, Webb, Russell and Wattenberg2000; Norris, Reference Norris2000; Gibson and Römmele, Reference Gibson and Römmele2001; Römmele, Reference Römmele2003).

Empirical research on the relationship between Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) and parties has focused mainly on either the functions performed by parties (opinion formation, interest mediation, electioneering) (Margolis et al., Reference Margolis, Resnick and Tu1997; Ward, Reference Ward, Ward, Owen, Davis and Taras2008) or internal party organization, particularly in terms of the level of internal democracy and distribution of power (Smith and Webster, Reference Smith and Webster1995; Gibson et al., Reference Gibson, Nixon and Ward2003). Other studies have identified ideal types of party ICT-enabled organization (Wring and Horroks, Reference Wring, Horrocks, Axford and Huggins2000; Heidar and Saglie, Reference Heidar and Saglie2003; Löfgren and Smith, Reference Löfgren, Smith, Gibson, Nixon and Ward2003; Margetts, Reference Margetts, Katz and Crotty2006).

Systemic approaches to the empirical analysis of the potential transformation of parties’ organizational models seem to be less common, in particular, those based on the combination of party-focused studies with the most recent digital literature. According to Gibson and Ward (Reference Gibson and Ward2009, 96), ‘traditional party-focused research has tended to downplay the role of ICTs, whilst the newer Internet field has arguably focused too extensively on the technology’.

The aim of our paper is to fill this empirical gap by focusing on political parties' organizational reactions to the challenges posed by new digital technology. We are interested in scrutinizing whether parties evince a transformative tendency towards virtual models in which new digital ICTs are used not only to carry out the traditional functions of communication and expression but also as ‘functional equivalents’ of the old organizational infrastructures. In other words, we want to verify whether ‘new web tools are actually breaking down traditional collective party structures and replacing or supplementing them with virtual networks’ (Gibson and Ward, Reference Gibson and Ward2009, 96).

To this end, the paper proposes a comparative analysis of the main Spanish political parties. Since the beginning of the crisis in 2008, the Spanish party system has changed radically, becoming a typical example of transformations of well-established political systems during the Great Recession. New parties such as Podemos (We can) and Ciudadanos (Citizens – C's) have appeared both on the left and right to challenge the old Partido Popular (Popular Party – PP) and the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party – PSOE). These new parties compete not only in terms of political proposals but also in terms of party-form and use of web tools. Parties that show similarities with Podemos and Ciudadanos – i.e. new parties that have challenged existing political forces also in terms of organizational aspects – recently emerged also in other European countries: the Movimento 5 Stelle in Italy, La France Insoumise in France or Alternativet in Denmark. The Spanish case is particularly significant because, differently from other political systems, the two new parties as well as the traditional parties, have different ideological orientations: this fact allows us to widen the comparative aspects, identifying similarities and differences in terms of adaptation to the new digital environment according to both the two cleavages: new/old and left/right.

Party change and new communication technologies

The wide literature on party change identifies the historical evolution of several party types. In the early 1950s, during the heart of the golden era of mass parties, Duverger (Reference Duverger1951) spoke of ‘left-wing contagion’. Some decades later, on the other side of the ocean, Epstein (Reference Epstein1967) spoke of ‘contagion from the right’ – this theme is closely associated with the preponderance of a catch-all tendency in party transformation (Kirchheimer, Reference Kirchheimer, La Palombara and Weiner1966). In both these cases (Duverger and Epstein-Kirchheimer), political change depended on external factors linked to the transformation of the social and economic structure as well as of democracy and of the State itself.

Based on these premises, the aim of the paper is to analyze the effects of the fourth industrial revolutionFootnote 1 on the organizational models of parties today.

Early research on ICT use in organizations has focused mainly on two approaches: one framed in terms of equalization and the other framed in terms of normalization (Gibson and Ward, Reference Gibson and Ward2009). According to the first approach (see Doherty, Reference Doherty2002; Bennett, Reference Bennett2003), outsider or fringe organizations are likely to benefit disproportionately from the rise of new ICTs in comparison to mainstream parties. The second approach (see Resnick, Reference Resnick, Toulouse and Luke1998; Margolis and Resnick, Reference Margolis and Resnick2000) conversely advances the so-called ‘politics as usual’ scenario: as the internet becomes increasingly normalized, large traditional political forces will come to predominate as they do in other media.

More recent studies (Gibson and Ward, Reference Gibson and Ward2009; Vaccari, Reference Vaccari2013) have rejected ‘one size fits all’ explanations, underlining that, ‘the internet may not make much of a difference for some parties and voters in some contexts, but it may do so for some others in other situations. Even in the same political system, the web may affect some political actors and groups of citizens but not others’ (Vaccari, Reference Vaccari2013, 18).

Starting from these theoretical premises, our hypothesis is that the reactions of parties to new digital ICTs can vary along a continuum of different degrees of innovation. Taking inspiration from research on innovations in the business worldFootnote 2, we hypothesize that the absorption or internalization of digital technologies can favour two polar types of reactions or innovations in the party organization. We might call the first type ‘sustaining innovations’: organizational changes that take place on the margins, in small steps. Parties use superficial communications technologies to disseminate information, attract new members, carry out electoral campaigns or simply survey public opinion. These are ‘symbolic reforms’ (Gauja, Reference Gauja2017) or peripheral innovations. In these cases, technology is used to reduce organizational and communication costs. If a member or supporter interaction is incidentally encouraged, it does not extend to the party's main activities (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Segerberg and Knüpfer2018). This type of innovations does not affect the parties' organizational structure or significantly alter the way in which they carry out their main functions (coordination, aggregation and integration, decision-making).

At the other end of the spectrum, we find ‘disruptive innovations’: intense and radical changes that create deep discontinuities within organizations and in their surrounding systems. ICTs are used both as instruments of structural and procedural coordination and as strategic elements. In this case, ‘technology platforms and affordances are indistinguishable from, and replace, key components of brick and mortar organization and intra-party function’ (Bennett et al., Reference Bennett, Segerberg and Knüpfer2018, 12). In other words, they can integrate, support or even substitute parties' structural architectures, contributing to solve the problem of coordination between the various parts of the organization, given way to lighter forms of organization (Gerbaudo, Reference Gerbaudo2019). In addition, ICTs can be used to perform the function of aggregation and integration: allowing new kind of linkages with voters, civil society and the self-same institutions. Finally, they can be adopted for participatory aims, offering new channels of members' inclusion in decision-making processes.

Disrupting innovations do not necessarily involve at the same time all the functional and structural dimensions. Furthermore, in relation to participation, they do not necessarily imply a concrete strengthening of parties' internal democracy: new ICTs, although theoretically designed for participatory and horizontal aspirations, can be then practically used in favour of forms of top-down disintermediation (Lusoli and Ward, Reference Lusoli and Ward2004; Biancalana, Reference Biancalana2018; Gerbaudo, Reference Gerbaudo2019).

We must, therefore, ask what factors (a) push parties toward either pole of the sustainable-disruptive innovation continuum and (b) affect the direction – top-down/bottom-up – of innovations through digital tools.

On the demand side, factors including the characteristics of the electorate and, in particular, widening dissatisfaction and ‘protest potential’ increase the attraction of ‘extended mediatization’ (Mazzoleni, Reference Mazzoleni2012, 67–68) and disruptive innovations for fostering participation.

Our analysis focuses, however, on the supply side. On the basis of most recent research (Römmele, Reference Römmele2003; Padró-Solanet and Cardenal, Reference Padró-Solanet and Cardenal2008; Gibson and Ward, Reference Gibson and Ward2009; Vaccari, Reference Vaccari2013; Borge-Bravo and Esteve-Del Valle, Reference Borge-Bravo and Esteve-Del Valle2017), we hypothesize that given equal levels of systemic technological diffusion, parties use new ICTs in different ways depending on the characteristics of the parties themselves: (1) the age of the party in association with its place in the party system (2) the ideology and organizational goals of the party.

Party age and position in the party system (challenger/mainstream; incumbent/opposition): those parties born in the last decades are more likely to adopt new ICTs, especially those ‘political entrepreneurs’ that have emerged during the Internet age. According to Gibson and Ward (Reference Gibson and Ward2009), systemic and technological opportunity structures set the political and technological parameters within which political organizations operate, thereby influencing the extent and style of organizations' use of technology. As a consequence, digital tools can be an important feature of new parties' original model rather than a subsequent replacement for traditional bureaucratic technologies.

Moreover, for younger, new or genuinely new parties (Sikk, Reference Sikk2005; Morlino and Raniolo, Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017), the absence of pre-existing structures and consolidated dominant coalitions favours more radical innovations that affect both their organization and their relations with the environment and citizens. New digital technologies offer numerous opportunities to challenger or oppositional parties, especially since these benefits from the turbulence of electoral markets in 21st-century democracies. For these parties, ‘incentives are greater, as an Internet presence can give them a forum in which to compete for nodality on a more equal footing with more established parties’ (Margetts, Reference Margetts, Katz and Crotty2006, 530).

Conversely, traditional parties have well-established bureaucratic structures and communication channels. In these cases, the costs of change are very high and institutional inertia tends to prevail, thus limiting the party's capacity to adopt innovations. Despite these barriers, it is possible to hypothesize that a contagion effect will lead traditional parties to eventually introduce innovations. However, these changes will be minimal and aimed at increasing their competitive advantage. We can also expect the propensity for innovation to weaken when parties increase their political weight in the party system or are in power. As underlined by studies on parties' communicative strategy (Gibson and Römmele, Reference Gibson and Römmele2001; Vaccari, Reference Vaccari2013), while electoral failure or marginality trigger ambition and urge to change, the maintaining of an incumbent position absorbs the party in the business of government, limiting the change. The first part of our hypothesis is therefore that:

Hypothesis 1

New challenger parties will tend towards the ‘disruptive innovations’ pole, while old and mainstream parties and incumbent parties will tend towards the ‘sustaining innovations’ pole.

Party ideology and organizational goals: parties differ from each other in terms of both ideology and organizational goals. Despite what has been said about the crisis or end of ideologies, they are still key to understanding parties, their strategies and their role. Some clarifications are nonetheless necessary. First of all, here ideology must be understood in the ‘weak sense’ (Stoppino, Reference Stoppino, Norberto, Nicola and Gianfranco1983), as a set of shared values and beliefs that give meaning to reality and function as a goad to action. Ideologies are composed of two parts: the ethos and the doctrine (Ware, Reference Ware1996, 20–21). The first concerns the history of the party, its traditions and identity; the second consists of a coherent set of statements and judgments in relation to particular positions or issues.

Ideology is conditioned and interacts with other dimensions of the party (Panebianco, Reference Panebianco1989) such as its dominant coalitions and leaders, organizational structures and even communication technologies. In any case, ideologies are one of the factors that explain a party's ‘primary objectives’ of votes, office and policy (or some combination thereof) (Harmel and Janda, Reference Harmel and Janda1994). In this sense, parties cannot easily be rid of the constraints posed by ideology. Therefore left-wing parties generally tend to be more sensitive to the issue of internal democracy (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi2017), historically prioritizing it as a party aim, while right-wing parties give greater importance to hierarchical control. This difference, according to some studies, is also reflected in the use of digital tools. In particular, Vaccari (Reference Vaccari2013), through a comparative analysis of the websites of several parties in various political systems, has shown that left-wing parties are more open to facilitating online interaction in their webpages than right-wing parties. Similarly, Borge-Bravo and Esteve-Del Valle (Reference Borge-Bravo and Esteve-Del Valle2017), comparing the activity of Catalan parties on Facebook, showed a greater capacity for initiative and interaction of left-wing parties than their right-wing counterparts.

Thus, we further hypothesize that:

Hypothesis 2

The parties that identify themselves as or tend towards the left-wing give greater importance to participatory goals and to internal democratization by combining virtual democracy and direct participation, on-line forums and assemblies; parties self-identified as or leaning towards the right-wing tend to be more conservative and less prone to disruptive participatory innovations, using new technologies mainly for instrumental and communicative purposes.

The cases: a look at the Spanish parties

Most of the studies on the ICTs–party relationship focuses on the analysis of the US case or on the Northern European democracies, while Southern Europe countries remain less frequently investigated (Vaccari, Reference Vaccari2013). In order to contribute to expanding the range of analysis, we will focus on the Spanish democracy. It is a particularly suitable case study for two main reasons. First of all, the level of digitalization in Spanish society has grown rapidly in recent years, reaching rather high levels. According to the International Telecommunication Union, Spain's ICT development index in 2010 was 6.73, increasing to 7.79 in 2017. While it remains lower than in Germany or France, is similar to other European countries, like Italy, Portugal or also Belgium. Secondly, the Spanish democracy is a paradigmatic case of the political transformations that most European (Southern European in particular) democracies have undergone since the beginning of the economic crisis (Morlino and Raniolo, Reference Morlino and Raniolo2017). It allows us to compare both relevant (Sartori, Reference Sartori1976) new and old parties situated across the entire ideological spectrum: the PSOE, Podemos, the PP and Ciudadanos. In other words, the Spanish party system provides sufficient variability between the analyzed characteristics of the parties. The study of the four Spanish parties, therefore, makes it possible to verify and further clarify the hypotheses formulated in the previous paragraph, extending their potential application to similar cases.

The PSOE is a social-democratic party with a long history. Since the beginning of the economic crisis, it has faced electoral decline (Table 1), the challenge of a new competitor on the left, Podemos and a series of problems related to internal cohesion.

Table 1. Electoral results of the main Spanish parties: PP, PSOE, Podemos and Ciudadanos (2008–19)

a The electoral result gained by Podemos and its partners in three Autonomous Communities was 20.6%.

b Unidos Podemos (Podemos, IU, Equo); the entire coalition made up also of territorial partners gained 21.1%.

c Unidas Podemos (Podemos, IU, Equo); the entire coalition gained 14.3%.

Source: Ministerio del Interior

On the centre-right is the PP, traditional competitor to the PSOE. In recent years the PP has remained the predominant party despite losing part of its consensus (Table 1) and led the government in 2011 and 2016. More recently, however, it was subjected to a vote of no confidence due to corruption scandals and thus was forced to cede leadership to the PSOE. The latter came first in the early elections of 2019, while the PP lost much of its consensus in favour of Ciudadanos and partly of the new far-right party Vox.

Podemos is a genuinely new party. It was born in 2014 from a politicization of anti-austerity and democratic regeneration discourses, which had already emerged as key topics in 2011 with the Indignados movement. Following its unexpected success in the 2014 European elections, the party obtained 12.7% in the 2015 political elections and was the third most-voted party overall (20.6%) thanks to its collaboration with local organizations in several Autonomous Communities (see Table 1). In the following elections, Podemos joined with the radical left party Izquierda Unida (IU) and various territorial formations (Unidos Podemos). Despite substantial difficulties (the loss of more than 1 million of votes), the coalition maintained the third position in the party system until 2016, further suffering a consistent reduction in votes in the last elections (Table 1).

Ciudadanos was born in 2006 as a centre-right regional party active only in Catalonia. It subsequently became a state-wide party. It has built a moderate image, opposing nationalist forces and showing itself in favour of the current regional state organization, albeit improved by some reforms. After entering the EP in 2014, it became the fourth political force in the 2015 and 2016 general elections, almost surpassing the PP in the 2019 elections (Table 1).

In order to see how these four parties have adapted to new digital ICTs, we adopt an analytical perspective focused on the identification of three main dimensions of parties' organizational models: the participants in the organization, the organizational configuration and the decision-making process. We will examine whether and how digital tools are used by parties in each of these dimensions, beginning with a comparison of how the four parties thematise the issue of new digital ICTs in their political documents.

The web and the partisan identity

Since 2008, the PSOE has demonstrated willingness to modify its organizational culture in response to transformations of the ‘knowledge society’ and the ‘immediacy and bi-directionality typical of Internet’ (PSOE, 2008). The 2008 statute dedicates an entire section to the theme of the web and ICTs: Un partido en la red por una sociedad en red (an online party for an online society). The party shows an awareness of the need to dismiss ‘slow or excessively bureaucratic and hierarchical methods’ (PSOE, 2008, 156), strengthen new ICTs to expand external communication, facilitate internal communication and allow participation through new social networks. In 2012 the PSOE confirms the need to offer ‘a new model of party that is much more attractive for new generations’ and to be able to act as a forerunner of changes induced by technological progress (PSOE, 2012, 144). Finally, the 2017 statute both marks a strengthening of the party's left-wing identity and declares the intention to ‘offer new solutions and horizons to digital citizenship’ (PSOE, 2017, 43) by enhancing the digitalization of all its operational systems (PSOE, 2017, 146–147).

In comparison, the issue of digitalization is much less developed and is broached years later in the PP's documents, though it is not completely absent. In the 2008 Statute, the PP refers to new ICTs (in particular the website) in terms of tools to improve the functioning of the party (PP, 2008). Beginning in 2012, the PP centred the problem of adapting its organization to social changes in response to citizens' growing distrust of parties. New technologies thus became framed as tools with which to engage in ‘continuous contact with citizens’ (PP, 2012, 3), spread information (PP, 2012, 3) and expand internal and external communication (PP, 2017, 66), as well as a means to practice ‘virtual democracy’.

Unlike the two traditional parties, neither Podemos and Ciudadanos need to adapt their organizations to the digital environment. Although the former belongs to the radical left and the latter to the centre-right, both present themselves as innovators with respect to policy proposals and the party form. According to Podemos, the new ICTs are essential tools ‘to promote the acquisition of power by citizens inside and outside the organization and the direct participation of people in adopting public and political decisions’ (Podemos, 2014, 9). Similarly, the web 2.0 changed politics considerably for Ciudadanos by forcing the party to establish direct relationships with citizens beyond electoral campaigns, in their everyday lives (C's Secretary of Communication cit. in Prnoticias, 2015; Rivera, Reference Rivera2015, 19–20).

For Podemos, ICTs are among its constitutive factors and reflect a project of greater openness and internal democracy. Ciudadanos, on the other hand, has ‘regional-national’ origins, meaning its formation and development are linked to Catalan politics. ICTs initially were integrative factors and successively fundamental tools in the party's transition from the regional to the national context. They undertake a vote-seeking function rather more than a democracy-seeking function.

In summary, from the point of view of self-representation, all the Spanish parties give (different types of) importance to new technologies and link them to improving communication and widening participation. The main differences arise between the traditional parties, which face the problem of changing their cultures and organizational models (to stop the electoral crisis), and the new parties, that both propose themselves as challengers and innovators despite their different approaches.

In none of the cases are the new digital technologies and the ‘virtual structures’ considered completely viable alternatives to ‘real structures’: they are integrative and not exclusively tools. Left-wing parties seem more oriented towards innovations that allow for greater internal participation, but at the same time, they place great importance on conventional forms of participation in the physical territory. More specifically, in the case of the PSOEFootnote 3, the blend of real and virtual structures seems to be a prerequisite for organizational adaptation-innovation. For Podemos, as we will see later, the combination of virtual and real instruments reflects an awareness of the gap produced by digital participation (digital divide, disintermediation) gained gradually during its process of institutionalization.

Multi-speed membership and digital tools

All the Spanish parties recognize different affiliation models according to a multi-speed membership logic (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2015). Of all the parties here considered, the PP is the party that uses new ICTs least to encourage adhesion to its organization. The PSOE, conversely, can, in this case, be considered an early adopter.

Since the beginning of the 2000s, the PSOE, being in opposition and faced with the need to regain the trust of its supporters, had started a process of renewal of its organization, trying to blur the boundaries between members and sympathizers, making the organization more open and participatory, according to a leftist tradition (Méndez-Lago, Reference Méndez Lago2006). In the following years, in the face of the growing informatization of society, digital tools were adopted precisely because of the same organizational goal.

In 2008, the PSOE introduced the category of cyber-militant: an affiliate with the right to participate in online consultations, have an official email, connect his/her personal blog to that of the party, receive the party's digital publications and participate in cyberactivism campaigns (PSOE, 2008, 161). In more recent years, the party has distinguished between sympathizer (a member who does not pay any fees, receives political information and has the opportunity to participate in open internal electoral processes) and militant (a member with full rights and duties that pays a membership fee). Both the sympathizers and the militants can join the party electronically, but the latter must be confirmed by their local executive committee. Since 2013, the main novelty is the ‘direct affiliate’ (afiliato dírecto): a category created to respond to the low increase in supporters' subscriptions (PSOE, 2013). The direct affiliates, unlike militants, do not belong to a local party unit (agrupación local) and do not have to participate in the political life of the basic units but rather participate directly at the regional or federal levels. Direct affiliates enter the organization by filling out an online form and participate only occasionally or through online tools. They pay a membership fee and, with the exception of participation in internal party elections at the territorial level, enjoy the same rights as militants (PSOE, 2017). In its 2013 political resolution, the party states that cybermilitance is a complementary formula for participation available to members seeking to further engage via Internet (PSOE, 2013, 56). However, this greater flexibility in the forms of participation has not yet yielded the expected results, increasing membership extension only slightly (Table 2) after years of substantial decline (in 2008 there were 351.239 militants, while in 2014 they had fallen to 201,000, http://www.projectmapp.eu/database-country/).

Table 2. Membership data for the main Spanish Parties (2017–18)

a The total number of current Podemos membership is 507,827.

Sources: Data provided by the parties' website or collected from the press (C's: https://www.ciudadanos-cs.org/transparencia; Gálvez (Reference Gálvez2018); Podemos: https://participa.podemos.info/es; InfoLibre, 2017; PP: http://www.pp.es/participa/afiliate; Riaño (Reference Riaño2018); PSOE: http://web.psoe.es/ambito/afiliadasyafiliados/docs/index.do?action=|View&id=98014; Público (2017)).

Unlike the PSOE, the PP has declared a steady increase in the number of members since the 1980s (Astudillo and García-Guereta, Reference Astudillo and García-Guereta2006), claiming to be the largest party in Spain (PP, 2017, 13). It divides its membership into militants and sympathizers. The two categories comprise different rights and duties and differ regarding the payment of the registration fee. The same distinction is also found in Ciudadanos (Table 2) (https://www.ciudadanos-cs.org/afiliate). However, the whole process of affiliation to Ciudadanos takes place online, while to join the PP one can download the online form but then must physically deliver it to the local party unit (PP, 2017, 28–38).

For both Ciudadanos and Podemos, the web facilitates the construction of a community of adherents, bridging the organizational gap with traditional parties.

Ciudadanos introduced online affiliation without the requirement to join a territorial branch in 2007. According to Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio (Reference Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio2016), this new way of recruiting members made facilitated Ciudadanos' transformation from a regional party to a state-wide party. Within a few years of this change, membership had indeed increased from 4000 people in 2007 to 12,000 in 2015 (Ibidem), and currently reaches 160,000 members (Table 2). Thanks to these new members, the party was able to participate in the 2015 local elections without the benefits of a physical organization in many areas of the country (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, Reference Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio2016).

Podemos is certainly the party that has introduced the most innovations regarding membership. In the early years, there was only a single category of affiliation, enabling anybody to enjoy full rights to participation. To become a member, one simply needed to sign up on the party's website and agree with its political platform and organizational rules. Unlike all the other parties, there was no membership fee and no probation period or endorsement required to join. Spanish citizenship was not a prerequisite, nor was belonging to another party forbidden (Gomez and Ramiro, Reference Gomez and Ramiro2017).

These flexible affiliation procedures and low ‘membership costs' (Scarrow, Reference Scarrow2015) allowed the party to reach 200,000 members in 2014 (Franzé, Reference Franzé, García-Agustín and Briziarelli2018, 53) and grow rapidly in the following years (Table 2). At the same time, a wide membership has not guaranteed the ‘intensity’ of members' commitment to participation in the party's internal processes. For this reason and in order to measure turnout in the internal online decision-making processes, the party has begun differentiating between passive and active adherents. The latter are those members that have participated in online decision-making processes within the last 12 months (Gomez and Ramiro, Reference Gomez and Ramiro2017); at the time of the II Congress – Vistalegre II – there were 283,175 active members out of 456,725 total membersFootnote 4. After the second Congress in 2017, Podemos created the militant registry. Like basic affiliation, militant membership is accessible online and no fee is required, though donations are accepted. However, the personal information requested of militants is much more detailed than that required for a basic affiliation, and an identity document is now required, just as in the other parties under consideration (see Secretaría de organización y programa Podemos, 2017).

Despite these recent changes, Podemos remains more inclusive and cost-free than other new parties that have chosen to implement fluid notions of membership (e.g. the Pirates parties) (Gomez and Ramiro, Reference Gomez and Ramiro2017, 4).

While all the Spanish parties are on the main social networks, Podemos has the greatest following through these channels (Table 3). All of the parties except the PP have digital platforms for discussion and participation: the PSOE introduced the MìPSOE platform in 2013, Ciudadanos uses Red Naranja, and Podemos uses Participa/Plaza Podemos (see Section 7). Lagging behind the other parties, the PP stated in the 2017 statute that it will introduce virtual platforms into the party's territorial organizations (PP, 2017, 115). The delay of the PP derives from the absence of a participatory tradition, linked to a centralistic and elite-driven conception of the party that also in the past had prevented other forms of empowerment of the membership (Ramiro-Fernández, Reference Ramiro-Fernández2005).

Table 3. Spanish parties on the main social-networks

Official data, Last access 19 August 2018.

Traditional architecture vs. the network

From the perspective of organizational configuration, all the Spanish parties present a rather classical architecture. New ICTs can only be considered functionally equivalent to traditional architectures in the case of Podemos' initial phase.

The PSOE's main political organ between Congresses (where delegates are selected by provincial congresses) is the Federal Committee, which is made up of almost 300 members, including the members of the Federal Executive Commission, the 17 regional general secretaries, the sector coordinators, the institutional spokesmen, the secretary of the youth organization, the socialist representative of the FEMP (Federación Española de Municipios y Provincias), and various members elected by the Federal and Regional Congresses and, since 2017, also by militants and direct affiliates (PSOE, 2017). The main executive body is the Federal Executive Committee, which over time has become the main decision-making body (Magone, Reference Magone2009). It is composed of 49 people elected during the Congresses and is chaired by the Secretary-General. Other party organs include the guarantor, ethics and auditing commissions, all entrusted with the task of ensuring compliance with the Party Statute. The organization is articulated at the territorial level into municipal and local units (agrupaciones), grouped into Provincial, Comarcal and Island Federations. These last then form part of the Regional Federations. In recent years a parallel sectoral structure has been developed alongside the existing territorial structure in order to encourage member participation in various areas of interest (PSOE, 2017).

The PP's main organ is the Junta Directiva, which is composed of members of the National Executive Committee, 30 representatives elected by the Congress, institutional representatives at every level, ministers, regional presidents and secretaries, representatives of large cities and of the FEMP. Between Congresses, the Executive Committee functions as the governing and administrative body for the party. It is composed of 35 representatives elected by the Congress, the spokesmen for the parliamentary groups, the regional and local presidents (both in institutional and internal roles), the party's President and the Secretary-General. The Management Committee, led by the President, undertakes the management and coordination of the party. Finally, the Electoral Committee deals with election issues, the Guarantee Committee guarantees compliance with the Statute and the Autonomous Committee handles territorial issues. This structure is reproduced at both the regional and provincial level (PP, 2017).

As previously shown, the Internet has been a fundamental resource in Ciudadanos' expansion beyond the borders of Catalonia, particularly as a tool for organizational coordination around membership. Despite this, from a structural point of view, Ciudadanos appears to be ‘a new party dressed in traditional garb’ (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, Reference Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio2016, 596). The party organs include: the General Assembly, made up of members or delegates and convened every 4 years; the General Council, which acts as the decision-making body between congresses and is made up of 125 members elected by the General Assembly, a part of the members of the Executive Council (max 20), the spokesmen for the Regional and International Committees; the Executive Committee, which is responsible for the administrative and economic management of the party and is made up of 20–40 members including the President and the Secretary-General; the Standing Committee, a coordinating body; the Guarantee Commission and the Disciplinary Commission, which are responsible for compliance with internal regulations. The party is articulated at the territorial level into regional councils and local units (agrupaciones). Finally, the President is the political representative of the party, while the General Secretary has a coordinating role (Ciudadanos, 2017).

Podemos was founded in 2014 by a mixed group of intellectuals and university professors, social activists and members of the radical left party Izquierda Anticapitalista. In this primordial phase, social networks and the web were fundamental tools, used to spread the political message and to organize and coordinate the first assemblies. The list for the 2014 European elections was decided on the basis of online support from 50,000 people, and candidates were selected via open online primaries.

It can, therefore, be argued that new ICTs were constitutive of the organization. They should not, however, be considered exclusive instruments but rather fundamental channels within a trans-media logic (Raniolo and Tarditi, Reference Raniolo and Tarditi2017). The promoter of the initiative and current General Secretary, Pablo Iglesias, had already used modern communication tools before the formation of the party, presenting and participating in programs on local and national TV. The party's virtual network is supported by the most popular social networks (Facebook and Twitter) and various platforms for discussion and deliberation (Plaza Podemos), coordination (Loomio) and voting (Appgree and Agorà voting). Simultaneously, the party has promoted the parallel formation of a territorial network through the so-called círculos, the basic units inspired by the Indignados movement's assemblies. From its beginnings, the party has always linked the virtual dimension to the real dimension, that made up of physical organizations, assemblies and congresses (Tarditi, Reference Tarditi, Bianchi and Raniolo2017).

Podemos does have a physical headquarters and a series of organs which perform functions similar to those of any party: the Citizens' Assembly, composed of all party members, defines the political line and selects party and institutional representatives; the Secretary-General is the political and institutional representative of the party; the Citizens Council acts as the political direction board and consists of 62 members elected by the Assembly, the Regional Secretaries, a Representative of members abroad and, since 2017, four representatives of the circles; the Coordination Council is organized into secretariats and plays an executive and internal coordination role; and the Guarantee Committee, consisting of 10 people elected by the Assembly, has the task of ensuring compliance with internal principles and rules. Finally, the Circles are those sectorial and territorial units in which any interested persons may participate, whether enrolled in the party or not (Podemos, 2017a, 2017b).

Deciding online

In this paragraph, we will distinguish between two types of decision-making processes that express the ‘struggle for power’ in democratic and associative contexts (Raniolo, Reference Raniolo2013): the choice of people (decisions on nominations) and the choice of things (decisions on policies). The first category includes the choice of the party leader (secretary or president), the government leader (or the ruling coalition), election candidates (candidate selection processes) or other roles (eg. local administrators or party internal offices). The second category concerns the approval of political strategies or alliances, political-electoral programs and specific issues or policies.

This last dimension highlights the differences in the Spanish parties' relationships with the new ICTs. Once again, Podemos is the most innovative party, followed by Ciudadanos and the PSOE with the PP lagging behind.

The choice of people – decisions on nominations

The PSOE was the first party in Spain to introduce a candidate selection process for the Presidency of the Council of Ministers in 1998. Subsequently, in light of the problems that arose from that processFootnote 5, the party used traditional mechanisms for selecting its candidates for many years.

More recently, in 2014 and 2017, militants voted to choose the Secretary-General: Pedro Sánchez won with 49% of 132,702 votes (PSOE, 2014) and more than 50% out of 149,951 votes (http://consultasg.psoe.es/), respectively. Candidate selection processes were also held for regional presidents and mayors of big cities (Méndez-Lago, Reference Méndez Lago2000). However, digital tools were not used in any of these cases. Instead, members voted in person through their local party units.

Alone of the four parties, the PP never chose any of its institutional or internal candidates through member voting until 2018. The leadership, in fact, has historically thought that the primaries could give an ‘external projection’ (Raniolo, Reference Raniolo2013) of a fragmented party, leading to electoral defeat (Ramiro-Fernández, Reference Ramiro-Fernández2005). Following corruption scandals and facing the need to re-legitimize itself, the PP allowed its militants to choose the party president at its most recent Congress in 2018, albeit without using digital channels. Only the 66,706 militants who had previously enrolled to vote and regularly paid their membership fees were allowed to participate in the voteFootnote 6. The low number of participants has led many commentators to doubt the party's published membership data (Collado, Reference Collado2018).

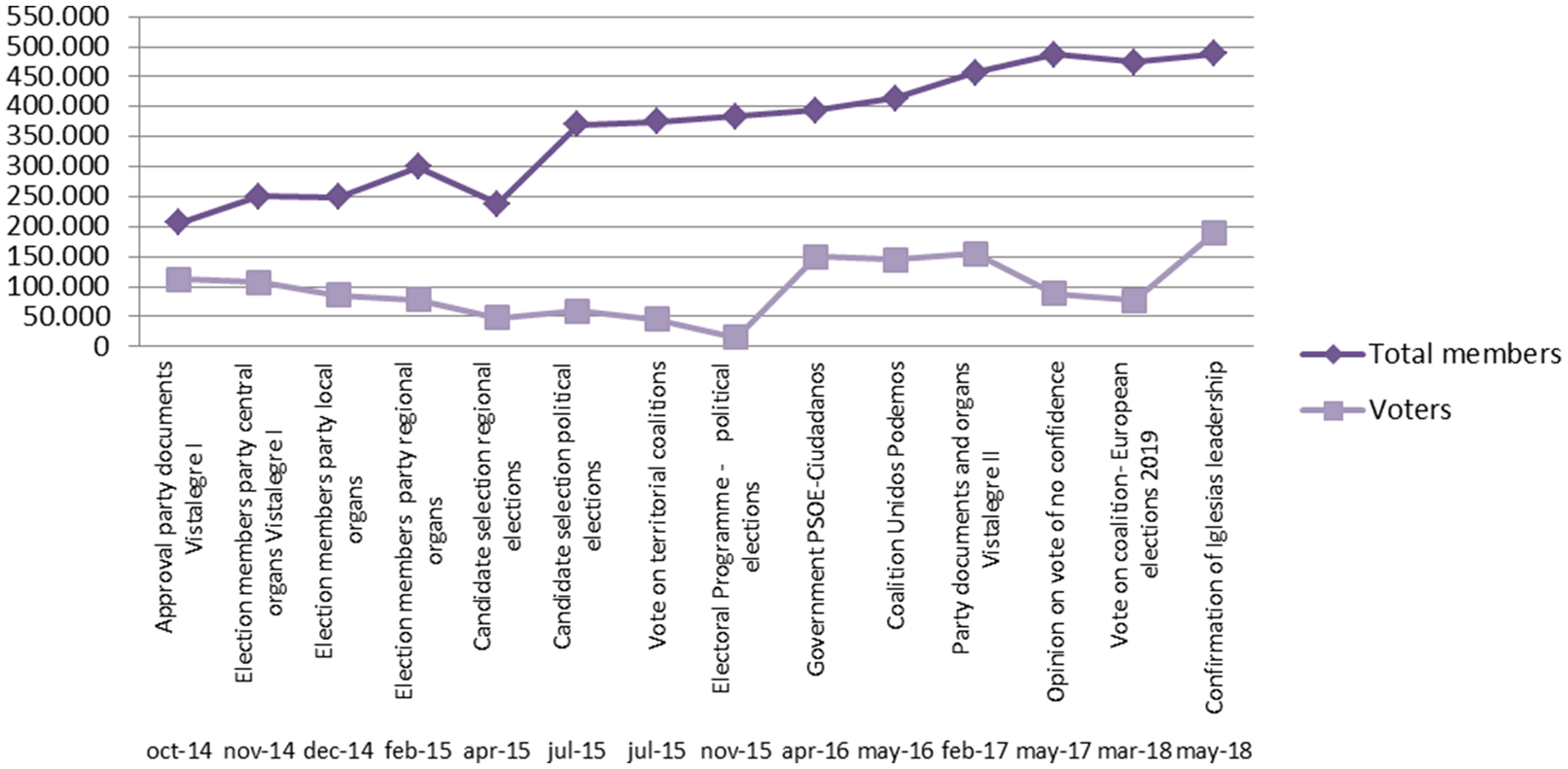

Of the two new parties, only Podemos has regularly and systemically involved all its members in online open selection procedures for all its internal and institutional representatives at every territorial level (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Participation in Podemos.

In the past, Ciudadanos held closed primaries for the top candidates in some local (Barcelona 2011 and 2015), regional (2010, 2012 and 2015), European (2009 and 2014) and national elections (2008; 2015) (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, Reference Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio2016).

The European elections in 2014 provided C's militants with the first opportunity to select candidates via the webFootnote 7. On that occasion, 3292 members expressed their preferences (Libertad Digital, 2014). Since then all primaries are carried out via the party's website, but only militants are allowed to participate. During the 2007 and 2011 Congresses the disposition of the party's internal offices was decided by the Congress delegates. In 2017, Albert Rivera was instead confirmed as party leader through an online vote held in response to a grassroots push for greater involvement in leader and candidate selection (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, Reference Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio2016). Passing from the regional to the national dimension and abandoning a peripheral position, the party had used the web to facilitate the adhesion to its organization, reducing however online spaces for discussion and participation. While Rivera won 87.3% of the votes cast, only 6874 out of 20,065 militants participated (Estebán, Reference Estebán2017).

Both Podemos and Ciudadanos' candidate selection processes have been criticized in multiple instances.

Most of Podemos' selection procedures took place using the so-called lista plancha, which allowed voters to select groups of candidates all together with a single click. This generally benefited the groups which included the party leader and the most visible media figures (though not always). This effect has been amplified by the tight time limits for submitting a candidature. It would seem that online primaries, though they constitute an innovative element in the Spanish party context, have been mostly used as a means of consolidating direct links (between leader and electorate) and therefore as a ‘plebiscitary instrument’ (Roberts, Reference Roberts, De la Torre and Cynthia2013) rather than a participatory instrument. They consolidate the process of the party's personalization. At the same time, however, primaries, especially at the regional level, have also facilitated the election of members of the ‘critical sector’ (e.g. Teresa Rodríguez in Andalusia or Pablo Echenique in Asturias). This fact has ensured that a certain level of internal pluralism is maintained (Tarditi, Reference Tarditi, Bianchi and Raniolo2017).

C's primary elections have been criticized for the strict requirements they impose upon militants seeking to participate as candidates. Militants must have the support of a rather large number of members to be eligible. As a consequence, in many territorial contexts, the only members to successfully participate in internal elections have been those backed by the leadership (Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio, Reference Rodríguez-Teruel and Barrio2016). According to some of the party's activists, ‘the party apparatus’ essentially imposed some candidates, thereby reducing the competition (Piña, Reference Piña2015). Albert Rivera, for example, ‘won’ the nomination for the Presidency of the Government in the 2015 general elections completely unchallenged.

The choice of things

Since the 2012 Congress and after coming back in opposition, the PSOE has declared itself favourable to introducing ways to consult with its militants on decisions of particular importance (PSOE, 2017). Until now, however, the party has involved its militants only in a single non-binding consultation on the virtual MìPSOE platform. Faced with the absence of a clear majority following the 2015 elections, the PSOE solicited its militants' position regarding the possibility of a governmental coalition with what it termed ‘progressive forces’. This internal referendum was couched in very general terms and did not indicate potential coalition partners. At that time an agreement was reached with Ciudadanos, but not with Podemos. Of the PSOE's 185,887 militants, 96,062 participated in this consultation and 78.94% of them voted in favour of the agreementFootnote 8.

In the case of the PP, there is no decision-making process which is open to the direct participation of its members.

Of the new parties, on the other hand, only Podemos has frequently carried out internal consultations for competitive choices or single issues (Figure 1).

Although Ciudadanos claims to have more than 14,000 digital activists (http://www.ciudadanos-cs.org), it seems to use the Red Naranja virtual platform more as a forum for discussion and for the dissemination of information than as a decision-making arena. The party describes the platform with these words: ‘we are the orange force in the social networks; we spread the C's message across all over Spain; we talk with people and we offer solutions’ (https://www.ciudadanos-cs.org/red-naranja).

C's sympathizers can also sign up for three types of participatory events via the web: Cafè con Albert (Coffee with Albert), Encuentro twittero (Meeting on twitter) and Parlamento Abierto (Open Parliament). These are meetings in which the party leader and MPs meet sympathizers and answer their questions. These events are clearly driven by vote-seeking logic and a consumerist strategy (Löfgren and Smith, Reference Löfgren, Smith, Gibson, Nixon and Ward2003) aimed at creating linkages with sympathizers. There is no real deliberation involved in these encounters. Like Ciudadanos, Podemos also promoted meetings with citizens, known as El Congreso en tu plaza (The Congress in your plaza). These meetings were held before the 2016 general elections to ‘give an account' of the work being done inside Parliament.

More generally, however, Podemos' use of digital tools seems to be driven by a participatory and deliberative logic, according to a ‘grass-root strategy’ (Löfgren and Smith, Reference Löfgren, Smith, Gibson, Nixon and Ward2003). The party is also undoubtedly the political force that stands out most in the Spanish context for introducing parallel digital channels since its origin.

Even before Vistalegre I in 2014, the first Podemos Congress, there was a 2-month series of virtual and physical meetings in which members contributed to composing the party's basic documents and approved them through online voting. Online participation was also promoted while preparing the program for the 2015 general elections. In the first phase of this preparation, members could make proposals through the plaza podemos virtual platform. In the second phase, members could vote on the proposals (Meyenberg, Reference Meyenberg2017). Finally, Podemos' members used digital channels to approve the territorial electoral coalitions in 2015, the electoral coalition with Izquierda Unida in 2016, the new party's political and organizational documents at the second Congress in 2017 and took various votes on single issues.

Criticisms have also emerged regarding internal referendums and the elaboration of party documents, in particular regarding the ways in which the leadership influenced the outcome of the decision-making processes through public declarations and greater media access (Donofrio, Reference Donofrio2017). Similarly, the Plaza Podemos digital platform did not appear to be completely satisfactory. Unlike the other parties' virtual platforms, Plaza Podemos is designed as an arena for discussion and deliberation, where affiliates can propose political initiatives and proposals. Thus far, the deliberative aspect has not actually worked. According to Borge-Bravo and Santamarina-Sáez (Reference Borge-Bravo and Santamarina-Sáez2016), Plaza Podemos offers the widest potential for inclusion and for parity between participants without moderator intervention. It is, however, weak in terms of its external impact. The imbalance between members of the platform in total and the number of actual participants has usually hampered the deliberative process, preventing members' proposals from gaining the necessary support to be included in the party's program.Footnote 9

Despite the limits of virtual democracy, we must underline that Podemos has been able to use the new ICTs to multiply its participatory channels of communication (Donofrio, Reference Donofrio2017). This confirms Podemos to be the main innovator in the Spanish context with regard to using ICTs.

Moreover, when faced with the limits of digital democracy as clearly demonstrated by the fluctuating level of participation (Figure 1), Podemos reacted by trying to strengthen its territorial network of circles. As the party's leadership admits (Podemos para Todas, 2017; Recuperar la Ilusión, 2017), the circles, initially designed as deliberative and participatory spaces, have often been used as tools for electoral campaigning and have fallen prey to a progressive detachment between the territorial base and the rest of the party. This transformation can be attributed both to the difficulty of structuring a complex organization in a short period of time and to the leadership's attempt to ‘gather social strength starting from media and electoral campaigns' (Lago and Bustinduy, Reference Lago and Bustinduy2016). Podemos' recent attempt to reimagine the circles as essential tools to anchor territories, reach citizens in both rural and urban areas and ultimately overcome the digital divide can be considered typical of the leftist tradition.

Conclusions

Democracy in the 21st century is marked by the digital revolution and the shift toward the so-called democracy of the public (Manin, Reference Manin1997) and the democracy of leader (Calise, Reference Calise2015) in representative government. In the current scenario, dominated by new media and the advent of web 2.0, the relationships between parties and electors take on unusual, interactive, disintermediate forms.

Some authors have used the concepts of automedia (Lévy, Reference Lévy2002) and mass self-communication (Castells, Reference Castells2009), in the sense that communication continues to be mass communication ‘because it reaches a potentially global audience through p2p networks and Internet connection […]. It is also self-generated in the content, self-directed in emission, and self-selected in reception by many who communicate with many. This is a new communication realm, and ultimately a new medium, whose backbone is made of computer networks, whose language is digital, and whose senders are globally distributed and globally interactive’ (Castells, Reference Castells2009, 70).

The extended mediatization through ICTs offers new opportunities to cover the void (Mair, Reference Mair2013) which opens up between voters and leaders in individualized societies. Current digital communication promotes immediate networking flows and exchanges whose crucial aspects include ubiquity and widespread access to not only ICTs and TV on demand, but also to the traditional models of participation, which then become increasingly active, creative and unpredictable thanks to the internet (Mazzoleni, Reference Mazzoleni2012, 46–47; Vaccari, Reference Vaccari2013). In this sense, there can be a convergence between voters' growing dissatisfaction, electoral volatility and the new technologies that challenges the traditionally vertical relationships that characterize representation. However, much it depends on how and in what direction these tools are used.

The integration of new digital tools in the parties' organizations influence how the parties are and it interacts with and conditions what parties are (or say to be) and finally what they do. In this paper, we have studied how the main old and new Spanish parties are in relation to the three internal dimensions: participation, organizational structure and decision-making.

All the parties analyzed here use new digital ICTs, but each does so with different intensity and extension.

The first difference is between the old mainstream parties – the PSOE and the PP – and the new challenger parties – Podemos and Ciudadanos. In contrast to the ‘normalization’ approach, the analysis shows that the latter makes a more intense and radical use of new ICTs in all the three dimensions taken into consideration (Hypothesis 1).

The mainstream parties have been forced to deal with the problem of gradually adapting their organizations to the new digital and communications environment; the challengers have used new ICTs in order to create their organizations and solve the problem of coordination. More specifically, for Podemos the web is a constitutive resource that characterized its original model and was essential for aggregating and coordinating the supporters of its political message. For Ciudadanos, the web is a tool for extending the party's organizational presence over regional borders, allowing for a process of territorial penetration throughout the country.

In line with previous studies on communication, the other crucial difference is the left-right cleavage between the four parties. On the left, Podemos and the PSOE make greater use of ICTs in order to foster greater internal democracy and open the party to sympathizers when compared to their corresponding parties on the centre-right (C's and the PP) (Hypothesis 2).

Indeed, the virtual network's role in the dimension of participation draws a clear difference between Podemos and Ciudadanos. Podemos party members are regularly and systematically involved in both the ‘choice of things’ and the ‘choice of people’ through digital channels. For Ciudadanos this involvement is more sporadic, open only to the party's militants and limited to choosing people to fill party roles. The two parties' virtual platforms – Participa/Plaza Podemos and Red Naranja – are communicative spaces for discussion; however, only Plaza Podemos is designed to potentially function as a deliberative arena. Both parties have progressively reduced the participatory and decentralized use of ICTs, but only Podemos seems to thematize the issue. The party seems to be oriented to counterbalance the distortions of the concrete use of digital tools through the consolidation of off-line participatory channels.

With regard to the mainstream parties, only the PSOE shows an inclination to introduce digital tools which might facilitate lighter forms of adhesion and participation. The need to seize the opportunities of the digital revolution, attract younger members and experiment with new possibilities of participation has been a recurring theme for the PSOE since before the emergence of the new challenger parties. From this point of view, the PSOE shows similarities with other European social democratic parties, such as the Labour Party in the UK and the SDP in Germany, which, as noted by Gerbaudo (Reference Gerbaudo2019, 108), have also begun ‘internal discussions and limited experimentations with digital democracy tools’. The innovation boost in the PSOE has been strengthened in recent years, in the face of the need to rebuild consensus (H1).

Conversely, the PP is the less innovative party in terms of both the digitalization of its organization and its capacity to involve its members in party life. The use of new ICTs in this party is almost completely limited to communicative functions. This partly reflects the centralistic and top-down conception of the party that has historically shown to be reluctant to introduce ‘participatory incentives’ (Ignazi, Reference Ignazi2004) and, on the other hand, confirms how internal changes are unlikely when a party succeeds (Astudillo and García-Guerreta, Reference Astudillo and García-Guereta2006).

In conclusion, based on the transformations in the three dimensions – membership, organizational configuration and decision-making – none of the parties studied here can be considered as a proper virtual party. In relation to the organizational configuration, no party has completely replaced the real structures with the virtual network. Looking at the other two dimensions, Podemos is clearly nearest the disruptive pole on the continuum of innovation, followed by Ciudadanos and the PSOE, while the PP finds itself nearest the opposite extreme. It can be assumed that also the PP, following the recent defeat (Table 1), will introduce some other organizational changes, deepening a process of renewal partially started in June 2018 after losing the leadership of the government. Only by observing its evolution, it will be possible to verify if the changes consist of incorporation of new digital instruments.

In general, the analysis of the Spanish case shows how all parties (new/old, right/left) have to deal with the opportunities and challenges of the new communicative environment. The ability to integrate the new tools, approaching to sustainable or disruptive innovations, but also the direction and objectives for which the new tools are used seem to be influenced by specific party factors: the party age and position in the party system and the ideological approach.

In this regard, compared to the analysis proposed here, further research is needed to explore also the role and weight of the communication offices in the parties' organizations and in defining their innovation strategies.

Funding

The research received no grants from public, commercial or non-profit funding agency.