Introduction

This article examines the role of state-induced migration in the formation and consolidation of the imperial state in East Asia during the Qin 秦 and Han 漢 periods (221 BCE–220 CE). By “state-induced migration,” we mean large-scale, distant movements of humans on a permanent or semi-permanent basisFootnote 1 that involved direct impetus on the part of state government. While other scholars speak of “coerced” or “state-organized migrations,”Footnote 2 in this article, we argue that such migrations are better understood as part of a broader process that also involved private resettlements informed by state policies and institutions such as frontier colonization, improvements in communication infrastructure, and urbanization in the capital area.

State-induced migrations shaped the human geography of early Chinese empires by contributing to the formation of circumscribed zones of governmental involvement in economic management, social engineering, and cultural production. These were often achieved through the concentration of military, government personnel, agricultural producers, and craftsmen in specific locations. Such enclaves of intensive and direct state administration constituted the frame of ancient polities that lacked infrastructural power to exclusively control the hinterland within more or less clearly demarcated boundaries, despite rulers’ claims to the opposite. In most cases, they could only exercise such power through the mediation of local elites, which severely restricted the degree of centralized control. Not infrequently, hostile groups in provinces formally incorporated into the empire overtly denied any degree of local control to the nominal sovereign.Footnote 3

The porous, discontinuous nature of imperial territoriality was primarily defined by the terrain that rendered some areas more amenable to military control and economic exploitation than others. It was in such relatively accessible regions that “state spaces” tended to form. The term “state spaces” was coined by the anthropologist and agrarian historian James C. Scott to describe a “geography more amenable to state control and appropriation” as opposed to “geography intrinsically resistant to state control (nonstate space).” These territories were the loci of state formation and served as conduits for state expansion. While the location of the state spaces was shaped by natural geography and topography, their key feature, according to Scott, was the “concentration of grain production and manpower” for the purposes of extraction and deployment in state projects such as military conquest and distribution of wealth among constituencies.Footnote 4 State spaces were created through government action, especially through the relocation of people.Footnote 5 The objective of the present study is to explore the relations between such state-induced migration and territorial distribution of state power in the early Chinese empires of Qin (221–207 BCE) and Han (202 BCE–220 CE), drawing on evidence from newly excavated texts and archaeological sources as well as from transmitted texts.

To do so, we first discuss the typology and factors of migration, then outline the organizational means, or institutions of state-induced migration. Next, the article analyzes the role of migrations and migration management in the rise of centralized states during the Warring States period (453–221 BCE), which were immediate predecessors of the early empires. Finally, we turn to the case of the metropolitan region of the Qin and Western Han empires, Guanzhong 關中 (“Within the Passes”) in the Wei River valley (Figure 1), to observe the intertwining between state-organized resettlement and private migration, and their combined impact on the demographic, economic, and cultural profile of the region.

Figure 1. Location of the main geographic regions mentioned in this article

The nature of human resettlements, their connection to local geography, the scope of state involvement, and interaction with local populations naturally differ from locale to locale as well as by the time period. This will be the subject of a book-length study currently in preparation. This article serves to introduce the concept and approach to the scholarly audience and test it on the case study of the Guanzhong region.

Migration in Early Imperial China and Beyond: Typology and Factors

Studies on migration, including the present one, customarily make use of migration typologies, most of which differentiate between various types of migration based on their organizational features. State-organized, forced (or coerced), and voluntary (or private) resettlements are the essential vocabulary in migration studies. However, these types are not entirely distinct. As Tacoma and Lo Cascio have observed, “the distinction between forced, state-organized and voluntary migration is important for analytical purposes, but … the three forms merit being studied together, as they impinged on each other.”Footnote 6 We go one step further and argue that in reality, the boundaries between them are fluid, one may trigger the other, and the impact of every type of migration can only be appreciated if its relationships to other types are taken into account. As we demonstrate below, mobile populations were a critical asset for state-building during the Warring States era. While in some cases the states directly triggered migration, mainly through deportation of the conquered and resettlement of criminals into forcibly emptied areas,Footnote 7 governments often capitalized on the existing flows of “private,” individual migration, voluntary as well as forced by factors such as overpopulation and natural disasters. When successful, state-sponsored settlement projects generated externalities that induced individual voluntary migrations and affected the geography of human mobility.

In spite of the criticism of its core terminology, the “push” and “pull” typology of driving forces in migration allows the analysis of otherwise complex motivations of individual agents.Footnote 8 State-orchestrated relocations by definition prioritizes government interests over those of migrants, rendering the push factors more visible than the pull ones, however, the latter were rarely wholly absent. In the case of coerced resettlement of the conquered, they were sometimes allowed to engage in potentially lucrative industrial enterprises,Footnote 9 while the criminals relocated to the colonies on newly conquered lands received amnesty meaning a potential betterment of living circumstances in comparison to hard labor or other forms of punishment.Footnote 10

When it comes to motivating factors, it becomes even more clear that the three previously mentioned types of migration are closely intertwined. Voluntary (private) migration was often “pushed” by population pressure or lack of land, also by the lack of social mobility or economic opportunity. It was “pulled” by the possibility to improve one's economic and social standing. State-organized movements likewise frequently took place in response to population pressure and attracted resettlers with the promise of economic opportunities, which materialized via state-regulated land distributions and government spending in subsidies and infrastructure projects. Similarly, natural disasters often intensified the already existing push for population movement rather than creating utterly new flows of forced migration. For example, river floods resulted in displacements of large groups of people when they hit regions already afflicted by high demographic pressure. For the state, refugees from disaster presented an enormous organizational challenge but also an opportunity to divert the stream of forced migration toward the desired destinations. Here, the strengthening of push factors in one type of migration reinforced the pull of organizational solutions offered by the other type.

Institutions Facilitating State-Induced Migration in Early Chinese Empires

Throughout their history, the early Chinese empires not only organized migration but also contributed to the development of structures and behaviors that facilitated private migration. Here, we consider these policies, structures, and practices as institutions of state-induced migration.

Colonization, i.e., sending people to settle among and project state control over the local population of another territory, was the key institution through which the Qin and Han rulers sought to manage migration. The government chose settlers from the general populace as well as prisoners of war, amnestied criminals, and manumitted slaves, and supervised their movement to agricultural colonies or urban settlements. Resettlement was often accompanied by land distribution. In some cases, state-organized colonization created extensive zones of settlement in previously sparsely populated regions. The foundation of agricultural colonies in the Hexi Corridor 河西走廊 (present-day Gansu Province) and the Juyan 居延 Lake area (present-day Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region) during the Western Han period, for instance, resulted not only in the profound transformation of the local society and economy but also in ecological change caused by the opening up of grasslands for farming.Footnote 11

Disaster relief and fugitive resettlement were official policies in at least some of the Warring States as early as the fourth century BCE.Footnote 12 During the early imperial era, some of the largest migrations occurred as the result of natural disasters, particularly the breach of dikes on the Yellow River and ensuing floods. The breach of Yellow River dikes in 132 BCE, followed by many years of disastrous flooding, caused the relocation of over two million people.Footnote 13 The imperial authorities responded with resettlement campaigns, two of which, involving 700,000 people in 119 BCE and at least 400,000 people in 107 BCE, were explicitly directed to recently conquered regions in the north, northwest, and southeast of the empire, where the government was struggling to establish strongholds and enhance agricultural production.

Besides immediate involvement in the organization of resettlement, the Qin and Han empires induced migration by providing communication and transportation infrastructures and improving security conditions for moving individuals and groups. By the end of the Han era, the total length of specially made roads is estimated at over 35,000 kilometers.Footnote 14 Official histories document state-organized labor projects aimed at improving water-borne transportation.Footnote 15 The imperial government contributed to travel security by developing a network of guard posts which also provided accommodation for travelers.Footnote 16 This dense network of facilities, one of the most extensive in pre-modern history, facilitated state-authorized migration while restricting vagabondism.

Besides the centralized institutions and policies, state-induced migration was informed by the institutions that lacked central regulation: markets created opportunities for employment, affected the flows of supplies and goods, and, in the longer run, distribution of population in production and consumption centers. One of the imperial government's key contributions to this otherwise less controllable mechanism was the supply of coinage, which, in the state of Qin, was first introduced in the fourth century BCE.Footnote 17 After almost a century of fluctuating monetary policies, in 113 BCE the Western Han Empire launched centrally issued high-quality wuzhu 五株 coins on a sustainable basis.Footnote 18 The introduction of a stable monetary system must have greatly facilitated trade at least within the core area of the empire. Under the condition of the monetized taxation system, when provinces had to annually remit cash to the capital, commerce, as well as temporary and permanent labor migration, can be expected to gradually reorient toward the loci of privileged access to coinage.Footnote 19 The longer-term effects were economic specialization in regions that enjoyed convenient transportation access to the capital, and probably also the growing standardization of consumer culture as metropolitan tastes informed production throughout the empire.

Historical Background: Human Migrations and the Rise of Centralized States in the Warring States Period (453–221 BCE)

Advances in technology and social transformations of the late Spring and Autumn (770–453 BCE) and the Warring States period triggered demographic growth and territorial expansion of the societies within the Zhou cultural sphere.Footnote 20 The use of ox-drawn iron plows facilitated agricultural expansion into areas marginal to previous population centers, particularly the reclamation of fertile alluvial soils in the river plains.Footnote 21 Farmer households splitting off from the mainstream lineage structure at old political cores of the Zhou world seem to have played an important role in the settler societies inhabiting the formerly peripheral lands.Footnote 22 These changes heralded a new age in the history of state management of settlement in East Asia. Starting from the early Bronze Age, palatial centers in northern China were operating large-scale metallurgical production. After the spread of iron metallurgy in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE, state-managed foundries became important suppliers of agricultural tools to farmers.Footnote 23 The emerging centralized, bureaucratic administrations of the major Warring States contributed to the construction of hydraulic infrastructure, especially massive dikes that enabled large-scale settlements along major rivers.Footnote 24

Textual evidence suggests that many of the new settlements in the alluvial plains became state spaces, where governments deployed literate administration and novel taxation techniques to consolidate power. In the fourth century BCE, the state of Qin moved its capital from the middle reaches of the Wei River into the wider plain of the lower Wei basin.Footnote 25 This political move probably capitalized upon, but also contributed to, the major demographic shift from the well-drained slopes of the basin to its flat center.Footnote 26 In 364 BCE, Qin's chief competitor for military dominance in northern China, the state of Wei 魏, developed the new metropolitan center around the city of Daliang 大梁 at the heart of the Great Plain, where an enormous state-managed hydraulic project opened up vast swaths of agricultural land.Footnote 27 Along the Middle Yangzi, the state of Chu 楚 incorporated the lowlands to the south of Dongting Lake in present-day Hunan Province.Footnote 28

While the governments of the Warring States often took the lead in processes of land reclamation, much of the agricultural expansion was likely carried out with no substantial contribution by the state. Distanced from the old political centers with their rigid social hierarchies, the settler and trading diasporas developed new, syncretic identities and exchange networks that allowed simultaneous participation in various cultural traditions and economic circuits.Footnote 29 To some archaeologists, the absence of large and wealthy tombs in the excavated Qin cemeteries on the Loess Plateau to the north of the Wei River, and the relatively loose social hierarchy reflected by the cemetery evidence from Changsha area in northern Hunan suggest a more egalitarian society where the enforcement of official sumptuary standards was less stringent and class boundaries more porous than in the old political centers.Footnote 30 The quests for social mobility and economic opportunities are likely to have been among the key pull factors driving the colonists from Qin, Chu, and other regions to settle in peripheral territories that offered not only cultivable land but also industrial and commercial options.

The centralizing state administrations followed on the heels of the private “expansion through settlement.”Footnote 31 In the latter half of the fourth century BCE, the two polities at the periphery of the Zhou world, Qin and Chu, set up territorial administration in the regions that recently experienced an inflow of settlers. Between 328 and 324 BCE, the Qin founded the first of its commanderies, the Shang Commandery 上郡, on the Loess Plateau to the west of the Yellow River.Footnote 32 Around the same time, Chu established its first commanderies along the Yangzi.Footnote 33

Voluntary individual migration, augmented by state-organized population flows, emerged as the vital resource of centralized social engineering and economic management in the Warring States period. Some ideologists of the fourth century BCE Qin reforms maintained the view that the entire population of Guanzhong needed to be replaced by immigrants from overpopulated regions to the east.Footnote 34 While the feasibility of such a complete repopulation is doubtful, mortuary evidence suggests that large groups of settlers from the Fen River basin and the Great Plain moved to the Qin heartland in the late fourth and third centuries BCE, most likely as the result of some combination of private migration and state-organized resettlement of conquered populations.Footnote 35

Archaeological evidence for the arrival of people from all over the Zhou world can be found at cemetery sites such as Ta'erpo 塔爾坡, about ten kilometers west of Xianyang, which was in use from the Late Warring States through the imperial Qin period.Footnote 36 Here, both vertical shaft graves and catacomb tombs with various kinds of skeletal positions and alignment as well as a wide range of burial goods indicate diverse cultural origins of the tomb occupants.Footnote 37 Other cemeteries with graves of people from various cultural backgrounds have been observed across the Guanzhong Basin, suggesting that population of locals and immigrants of various origins coexisted there.Footnote 38 The assemblages of elite tombs from various sites show clear indicators of outside connection such as bronze vessels of types usually associated with the Sichuan Basin, vessels produced in Zhongshan (present-day Hebei), and other items from the Great Plain or other eastern regions. Nevertheless, the assemblages do not show any regularity in composition, and it is thus difficult to determine the place of origin or identity of the tomb occupants.Footnote 39

Many of the significant political, economic, and socio-cultural transformations in the mid-fourth century BCE state of Qin need to be understood against this background of heterogenous population. According to the Shiji, in 350 BCE Shang Yang ordered the “grouping” (ji 集) of small townships into thirty-one (or forty-one, according to alternative record) counties (xian 縣).Footnote 40 This radical change in settlement pattern was accompanied by a comprehensive survey of agricultural land in Guanzhong.Footnote 41 Land distribution was the key measure recommended for attracting migrants to Qin,Footnote 42 so it was crucial to have an accurate knowledge of the size of land under cultivation in each administrative unit, information that was also essential for the Qin system of land taxation. In the third century BCE, the Qin government presided over the construction of the Zheng Guo Canal (named after its chief engineer, Zheng Guo 鄭國, himself an immigrant from the state of Han 韓), a major irrigation project that, according to the historical records, converted around 40,000 qing (ca. 185,000 ha) of marshy and saline land into farmland available for distribution to cultivators.Footnote 43

At the state's core, the Qin government sought to manage migration in order to put human and natural resources under centralized control. In the outlying regions, resettlement and colonization were critical to the Qin strategy of territorial expansion and military provisioning. Agricultural colonies of settlers recruited in the Qin heartland, especially among the lower social ranks, were planted in the immediate rear of the critical war theaters to serve as a supply base to the Qin armies in the field. In several strategically important conquered areas, such as the lower Fen River valley (in the southwest of present-day Shanxi Province), Sanmenxia (western Henan Province), and the former Chu capital region on the Jianghan Plain (in Hubei Province), local populations were largely replaced by colonists who depended on the state not only for their land, farming tools, and seed grain but also for organization and security.Footnote 44

After the Qin had succeeded in conquering its rivals and “unifying” continental East Asia in 221 BCE, the management of human migration remained one of the critical tasks for the imperial government. The ability to direct population flows into desired directions became one of the markers of state power, and efficient responses to migration crises turned into an essential source of ruler legitimacy. At a more fundamental level, the empire's capacity to carry out its foreign and domestic policies, integrate and control territories, its very geographical shape were largely products of migration processes, many of which were organized or induced by the state.

The Metropolitan Region as Center and Focus Point of Migration Movements

The Guanzhong Plain 關中平原 is located in the lower Wei River basin and extends across about thirteen thousand square kilometers. It is surrounded by mountains and highlands and gained its name, “Within the Passes,” from the four passes that provide access into the valley from different directions: Dasan 大散關 (in the west), Hangu 函谷關 (in the east), Wu 武關 (in the southeast), and Xiao 蕭關 (in the northwest). It encompasses the center of Shaanxi Province with its largest cities Xianyang 咸陽, Xi'an 西安 (Chang'an 長安), Baoji 寶鷄, and Weinan 渭南. This region was the center of the Neolithic Yangshao 仰韶 Culture; the core of the Western Zhou and, later, the Qin state, as well as the capital region for several imperial dynasties until and including the Tang (618–907 CE). The Qin are assumed to have originated to the west of Guanzhong Basin, in the uplands of modern-day eastern Gansu. Archaeological evidence—almost exclusively from graves—suggests that they moved from there into Guanzhong early in the Spring and Autumn period (771–453 BCE), settling first at the western extremity of the plain, then moving east to establish residence near Baoji in the seventh century BCE, and finally establishing their capital in the lower Wei River basin in the fourth century BCE.Footnote 45

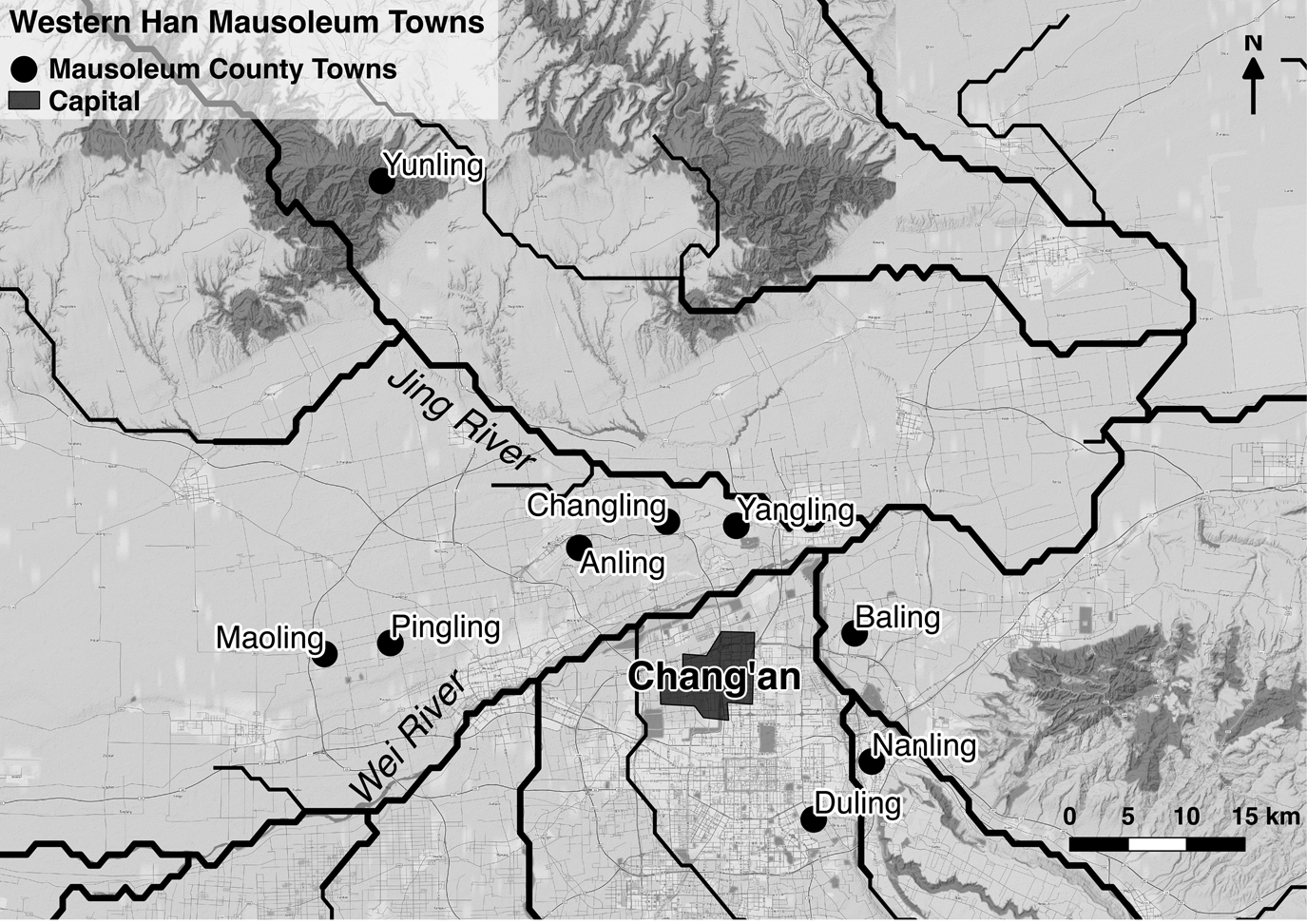

The administrative centralization in the mid-Warring States Qin and subsequent imperial “unification” made Guanzhong a very special region in the nascent empire. The exalted status of the emperor of Qin and the importance of his capital led to the construction of large-scale palatial buildings at the capital city of Xianyang, including the E'pang Palace 阿房宮 which was never completed.Footnote 46 Additionally, the First Emperor's mausoleum complex is located in the Guanzhong Plain, as is part of Qin's largest road project, the “straight road” (zhidao 直道), which commenced in the capital.Footnote 47 During the Western Han period, large settlements were built near the imperial tombs, the so-called mausoleum towns (lingyi 陵邑) (Figure 2).Footnote 48 All of these construction works required considerable manpower, while the capital and other urban centers in Guanzhong needed residents, administrators, artisans, merchants, cooks, artists, all in all considerably more people than were already present in the region. These mouths had to be fed, thus requiring agricultural intensification both in the Guanzhong and in other regions that became food suppliers for the capital.

Figure 2. Mausoleum towns in the Guanzhong region

Creating an Imperial Space: Population Intensification in Guanzhong

Of the Qin capital Xianyang, only the location of roads, palaces, and workshop areas is known, and only a small part of them has been excavated.Footnote 49 Substantial residential areas or marketplaces are yet to be found, making it difficult to assess population size or living arrangements. Textual accounts suggest that the Guanzhong region was home to over 2.3 million people by the time of 2 CE census, suggesting that the area was densely populated. However, there are no similar accounts for the Qin or early Western Han.Footnote 50

Qin is known for its building projects, many of which took place in the metropolitan region and involved large number of laborers and managerial personnel. Not all of them were brought here by force. From textual accounts, we know that some members of the elite were attracted into Xianyang by financial incentives.Footnote 51 Additionally, many administrators and artisans would have been attracted by rewards and promised career progression.

Archaeological evidence casts some light on the origins of these migrants. Pottery tiles with inscriptions relating personal information such as name, rank, and birthplace found at the Zhaobeihu 趙背戶 cemetery show that these were individuals from further east, including Shandong, Henan, Hebei, and Jiangsu.Footnote 52 There is some debate as to if these and others buried in the vicinity were convicts, corvée laborers, or hired hands. It is clear that they were involved in the building of the mausoleum.Footnote 53 Mitochondrial DNA from the bones of nineteen individuals from a burial pit located at about five-hundred meter distance from the Terracotta Army at Shanren 山任 reflects the population more diverse than any of the modern local populations from across China that they were compared to, suggesting that people buried at this cemetery had come from a variety of locations across the empire.Footnote 54 The researchers who conducted these analyses suggest that there may be a relatively high proportion of people of southern origin among them; however, given the small number of samples and methodological issues with comparing ancient DNA data with modern populations, this hypothesis needs to be tested further.

Another study chose samples from the city of Liyi 麗邑 and Shanren, investigating their diets via isotope study and comparing the evidence to data from other sites across China.Footnote 55 The Liyi data shows a strong reliance on millet combined with varying amounts of protein from domestic animals, a result that fits with isotope, archaeobotanical, and zooarchaeological data from northern China.Footnote 56 Of the Shanren individuals, only one has a profile similar to those of Liyi while all others attest to lower levels of protein consumptions, as would be expected from a lower-status group employed to do manual labor as opposed to a group of city dwellers. The Shanren population survived on a mixed diet of millet, rice, and possibly wheat, likely supplemented with wild game. The closest comparanda were found in Hubei, but the spread of the values would also allow for origins further south. The authors of the isotope study suggest that these individuals may have been prisoners taken after the defeat of the southern state of Chu; but at present this proposition, though appealing, is entirely speculative.

It has recently been argued that Guanzhong never had dense forests during the Holocene, and that its natural vegetation ranged from shrubby grassland to mixed forest.Footnote 57 Whatever timber resources were available in the plain and at its hilly margins appear to have been exhausted by the imperial Qin times when logs were brought in from Sichuan for the construction of the E'pang Palace.Footnote 58 At the Loess Plateau to the north of Guanzhong, there is evidence for deforestation and soil erosion leading to higher sediment loads in the Yellow River, changes in river courses, and higher frequencies of flooding.Footnote 59 All of these were the results of large building projects, intensification of agriculture and various types of production activities, and the movement of people into the region. These trends and developments toward an increasingly anthropocenic environment commenced already in the Neolithic but accelerated considerably during the early imperial period.Footnote 60 There are some disagreements concerning the role of climate fluctuations in these environmental changes as opposed to the human-made impact.Footnote 61

By the mid-Han period, rather than having too few people, the Guanzhong region had become densely populated, and even less suitable lands on the Loess Plateau and in the mountains had to be opened up, especially in the pastoral region in the north that had previously been home to relatively few people.Footnote 62 Archaeological, inscriptional, and transmitted textual evidence combine to draw an impressive picture of state-orchestrated population intensification in the metropolitan region of Qin and Han Empires.

State-Organized Resettlements, Their Cost, and Limitations

Within less than a year after the proclamation of the Qin Empire in 221 BCE, its ruler ordered the resettlement of 120,000 “powerful and wealthy” (haofu 豪富) households from the recently conquered territories in the east to the imperial capital Xianyang.Footnote 63 Based on a very conservative assumption that each household consisted of five individuals, this party amounted to at least 600,000 individuals.Footnote 64

By the end of the Western Han two centuries later, the census recorded 2,436,360 residents, but the population during the Qin imperial period was probably considerably smaller (although we do not know by how much).Footnote 65 In any case, the 221 BCE migration event would have resulted in a considerable increase in Guanzhong's population and concomitant strain on the ecology and resources of the host community. Moreover, the sources explicitly state that these households were settled in the capital or its immediate vicinity,Footnote 66 so their arrival ushered in a dramatic surge in agriculturally nonproductive urban population. One recently published unprovenanced manuscript from imperial Qin times suggests grain imports to Guanzhong from as far away as the Middle Yangzi.Footnote 67 Even so, it seems that the Qin capital was in the end unable to cope with the influx of migrants. After less than ten years many of its residents were resettled to other locations in Guanzhong, including Yunyang and the First Emperor's mausoleum town near Mt. Li (see Appendix).Footnote 68

Incomplete as it might be, this data presented in the Appendix suggests that the most substantial state-organized resettlements took place at the beginning of the imperial era, particularly after the Qin conquest of the eastern states and on completion of the wars of Qin succession in 202 BCE. Scholars have pointed out that the resettlements to the metropolitan region pursued the double goal of increasing population numbers while at the same time uprooting aristocratic clans and wealthy landowners in the eastern part of the empire.Footnote 69 However, these motivations persisted throughout the empire's lifespan. To explain the rarity of large-scale, state-organized resettlements as well as why they occurred when they did, it is important to consider the cost of such projects.

Migrations entail costs associated with the disruption of habitual lifestyles, liquidation of immobile property, travel expenses, and settlement at a new place. In the case of state-organized migration, these costs were partly shouldered by the government. Textual evidence of the logistical aspects of resettlement is scanty and primarily focuses on convicted criminals serving terms outside of their home areas. According to a looted manuscript from the Yuelu Academy collection, the Qin law required parties of convicts escorted under the official supervision to progress at the speed of 60 li (ca. 25 kilometers) per day and to stay at designated places overnight.Footnote 70 Travelling parties had carts to carry their belongings. These carts were pulled by oxen but probably more often by convicts themselves.Footnote 71 The same conditions applied to conscripted frontier soldiers en route to their service destinations.Footnote 72 Like all travelers on state commission, convicts and conscripts received food rations at the state-managed storage facilities along the route of their journey.Footnote 73 That travel expenses were a serious concern is suggested by legal regulations that insisted on rigorous control over travel speed and repeatedly emphasized that no delays would be tolerated.

How large were these expenses? Two relatively well-documented resettlement episodes of 221 and 199 BCE mainly targeted the populations at the Central Plains and the Shandong region (see Appendix). Today, a trip from the Linzi 臨淄 area in the lower reaches of the Yellow River, where the capital of the state of Qi 齊 was located, to Guanzhong would take around 900 kilometers, or c. 2,000 li. Of course, it was a considerably longer route in antiquity over roads that were often in less than ideal condition. Additionally, migrants would have been heavily burdened with their belongings, and the elderly and children could hardly be expected to march fast. The abovementioned travel speed of 60 li (ca. 25 kilometers) per day prescribed by the Qin statute for the convict parties was probably unrealistic,Footnote 74 but we will use this figure for now as it is the only number recorded in contemporary sources. Based on these assumptions, which greatly downplay the real duration of travel, the resettlement would require thirty-six days.

While on the way, resettlers were organized in parties accompanied by officials, and probably received grain rations, as did all other state-organized travelers during the early imperial period. The size of these rations was determined by each individual's age and gender. An official was entitled to one dou (two liters) of grain per day: the same as the rations for the working convicts.Footnote 75 If the same norm was applied to resettlers, supplying one person for the whole period of travel would have required 36 dou (or 3.6 shi = 72 liters) of grain. Although women and children received smaller rations than adult men, this figure is still a gross underestimate based on unrealistically optimistic assumptions about travel distance and speed. It also does not take the provisioning of cart-pulling oxen or supervising officials into account. When all these factors are considered, the estimate should be at least doubled. Moving 100,000 people, as in 199 BCE, would have required a minimum of 7.2 million liters (360,000 shi) of grain, and moving 600,000 people in 221 BCE, 43.2 million liters (2.16 million shi).

How large a percentage of the central government's grain reserves do these numbers represent? No data is available for the imperial revenues during the Qin or early Western Han periods. Two hundred years later, at the end of the Western Han, a populous and economically prosperous province, the Donghai 東海 Commandery in what is now southern Shandong and northern Jiangsu, reported an annual grain revenue of 506,600 shi, of which 412,600 were spent locally and the remaining 94,000 shi available to the central government as a surplus.Footnote 76 It remains unclear whether this surplus was eventually shipped to the state granaries elsewhere or stockpiled within the commandery's territory. Assuming that Donghai represented roughly 1/40 of the imperial revenue, the total volume of annual grain reserves of the central government would have been 3.76 million shi (ca. 58,656 tons of millet grain).Footnote 77 The resettlement of 600,000 people in 221 BCE would have taken about 58 percent of the annual grain revenue by the most conservative estimate and more likely well above 100 percent, especially considering that the migrants had to be supplied for a long period after arrival at their destination. In other words, if we accept the number provided in our sources as more or less accurate,Footnote 78 such a resettlement would have required years of reserve accumulation and still put the state coffers under extreme pressure.

These estimates, of course, need to be qualified in many ways. Some of the resettlers could have been asked to finance their move themselves. It can be assumed that wealthy individuals had their land and maybe other property confiscated, thus balancing out some of the costs involved in their relocation. One should also consider the composition of state revenue, which was considerably more monetized by the end of Western Han period than in the late third century BCE. The poll tax collected in coin (suanfu 算賦) was introduced at the beginning of Western Han.Footnote 79 Another major step in the monetization of state revenue was the establishment of iron and salt monopolies under Emperor Wu (141–87 BCE), the regime under which the local agencies of the central government engaged in commerce to draw profits from the expanding markets.Footnote 80 At the same time, on completion of the Qin wars in 202 BCE, the tax base was undoubtedly much smaller than after two centuries of relative peace and economic prosperity under the Western Han.Footnote 81 The above estimate, crude as it is, conveys the degree of pressure that the massive resettlements at the dawn of the imperial era exerted on the government's resources.

The high cost of organizing and financing migrations helps to explain why large-scale resettlement projects took place either immediately after massive internal warfare or in the wake of great natural disasters such as the break of the Yellow River dikes (Table 1). While wars and floods caused enormous economic damage, they also generated masses of displaced population who could be deployed in colonization campaigns on a scale unachievable in regular state-organized resettlements. These groups would require much less incentive to move, given that they had already been uprooted, and their expectations in terms of provisions along the road would be a lot more moderate than in the case of people who first had to be persuaded by the government to move elsewhere.

Table 1. Largest state-organized resettlements, third to first centuries BCE

Admittedly, the social background and circumstances of these migrants varied greatly. What nevertheless makes the cases listed in Table 1 similar is the strong political motivation on the side of the central government to manage resettlements in spite of the enormous pressure on the state finances. The powerful aristocratic lineages of the exterminated eastern states were perceived as an existential threat to the newborn empires that had to be reduced at all costs. The settlement of flood refugees was not something that could be neglected without risking major social turmoil. In other words, political externalities made the imperial government willing to accept economic costs that would probably be perceived as too large under normal circumstances. In order to exert a sustainable demographic and socio-economic impact, these rare cases of large-scale state-organized migrations had to be augmented by more stable population flows such as voluntary migration. Let us see how this relationship between the state-organized and private migration played out in the capital region.

Stimulation of Urban Demand

The largest of the state-managed resettlement campaigns to the metropolitan region, the relocation of 120,000 elite households in 221 BCE, specifically targeted the imperial capital of Xianyang. In 212 BCE, 30,000 Xianyang households were resettled to the newly founded town near the First Emperor's mausoleum at Mt. Li. During the Western Han, mausoleum towns became the backbone of the resettlement programs.Footnote 86 In almost all recorded episodes of state-organized resettlement, immigrants to the capital region ended up in one such town (see Appendix). By the beginning of the first century CE, the registered population of the largest “mausoleum county,” Maoling 茂陵 (mausoleum of Emperor Wu, r. 141–87 BCE; town founded in 139 BCE), comprised 277,277 people, surpassing the capital Chang'an with its 246,200 residents. The population of another mausoleum county, Changling 長陵 (mausoleum of Emperor Gao, r. 202–195 BCE; mausoleum town probably founded around 199 BCE), numbered 179,469 people.Footnote 87 No population numbers are available for the other seven Western Han mausoleum counties mentioned in the geographical treatise (Dilizhi 地理志) of the Hanshu, but they must have been considerable.Footnote 88 Some scholars argue that half of the population of the three metropolitan districts, which numbered 2,436,360 people at the turn of the common era, resided in the mausoleum counties,Footnote 89 but large cemeteries to allow the numerical assessment of these population centers have yet to be found.

The newly founded mausoleum counties probably included groups of locals as well as immigrants. Although some scholars view these figures as referring to urban populations,Footnote 90 the Hanshu mentions larger territorial units, counties, rather than towns. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that population numbers included both urban and countryside dwellers.Footnote 91 This said, settlement data—unfortunately gained exclusively from surveys rather than excavation work—suggests that the mausoleum towns were urban centers of a considerably greater scale than the standard county towns and probably approached the commandery centers and capitals of regional princedoms in terms of area and population.Footnote 92 Moreover, new towns were built even when the county in question already had an administrative seat of its own. This suggests that the mausoleum towns were intentionally founded as new urban centers and that resettlers there were primarily urban dwellers. Therefore, the high urbanization rates in the lower Wei River valley during the Western Han period were probably mostly caused by the rise of mausoleum towns.Footnote 93

Was the urban growth in the metropolitan region achieved through state-organized resettlement projects? While some scholars argue that migrants brought to the region at the beginning of the early imperial period formed the backbone of Guanzhong's urban population,Footnote 94 one needs to bear in mind that pre-modern urban populations were subject to attrition due to unhealthy sanitary conditions, resulting in demographic decline at the annual rate of approximately 1 percent for large cities.Footnote 95 Indeed, of three major urban centers of Chang'an, Changling, and Maoling, the household to population rates in the former two were, respectively, 1:3.0 and 1:3.5, and only the latter one probably had positive population dynamics with a rate of 1:4.5.Footnote 96 Steady arrival of new residents was needed for the reproduction and expansion of the Guanzhong cities.

What we know about the size of settler parties suggests that only a relatively small portion of this population influx was brought about by state-managed migration. Although such numbers are available just in a few cases, it seems that a standard size of settler party was about 5,000 households (see Appendix),Footnote 97 a far cry from the great resettlements of 221 and 199 BCE. Moreover, in many recorded instances, this number represents a quota for households allowed to move to mausoleum towns and not the size of the settler party organized and funded by the state. Regardless the degree of state involvement in the resettlement, the government in many cases targeted wealthy groups. In cases when the migrants were commoners (presumably bringing little or no wealth of their own), the government awarded them large amounts of cash, sometimes also land and dwellings. Moreover, cash could also be granted to the wealthy households (see Appendix). Some scholars suggest this money was partly used to pay for housing construction when the government provided only land plots,Footnote 98 but food was also a major concern. Between 129 BCE and 2 CE—i.e., during the period of mausoleum town development and concomitant resettlements to the metropolitan region—official grain imports to Guanzhong increased twelve-fold, from 20,000 to 245,000 tons.Footnote 99

The scale of cash disbursements to immigrants suggests that this was one of the major channels for pumping liquidity into the economy. The award of 100,000 cash (the minimal award amount mentioned) per household to just 5,000 households would have resulted in a one-time distribution of 500 million cash, more than twice the annual output of the imperial mints at the height of their productivity between 112 BCE and the first century CE.Footnote 100 In addition to the newly cast coins, the central government collected large sums of cash in taxes and through state monopolies, which, according to some estimates, amounted to as much as 7 billion cash by the end of Western Han period, while the total revenue equaled more than 18 billion.Footnote 101 While some levies were collected in kind, the tax system was considerably monetized by the turn of the common era, and vast majority of taxes were received in cash. This means that the central government had funds for massive cash distributions to the resettlers in mausoleum towns, yet such distributions would have represented a comparatively large part of its annual spending and resulted in enormous concentration of liquidity in the metropolitan region. Although it cannot be ruled out that some of these grants assumed the form of tax breaks rather than actual money handouts, other lines of evidence suggest that the capital region was the major concentration of demand for agricultural and manufactured products as well as for labor. This made possible the market-driven logistical initiatives of the central government such as grain shipments to regions of high demand, and also served as an economic impetus for the reorientation of human mobility networks toward the imperial core.Footnote 102 Records of individuals voluntarily resettling to Guanzhong are scattered across the transmitted histories and seem to have been a typical pattern of private geographic mobility in the Qin and Han empires.Footnote 103

The centers of artificially high demand for material goods, initially created through state-organized resettlements and redistribution of wealth and sustained by ongoing private migration, might also have been instrumental in the standardization of consumption standards and the spread of metropolitan material culture.Footnote 104 The Han era was a time of unprecedented commercial florescence, and some amounts of cash was available even in remote borderland communities. Nevertheless, a large portion of state spending was directed to a relatively small and compactly residing group of people, and the monetary economy was very uneven in terms of spatial distribution. Apart from its political and cultural attraction, the metropolitan region would also have exerted great economic appeal for producers and merchants in the taxpaying provinces, informing production decisions and ultimately material culture choices. This would have led to an increase in human movement—some only temporary in connection with trade and other business, but some permanent resettlement—toward the capital region and also to some other locales, such as the military frontiers, where state spending and organizational effort contributed to the emergence of new population centers with new opportunities.

Conclusion

In early imperial China, population mobility was inextricably intertwined with state power. The rise of the Qin and Han empires was accompanied by relocations of elite clans from the vanquished eastern states to the imperial metropolitan center in the west. Territorial expansion involved the movement of even larger masses of colonists to the frontiers. At the same time, unauthorized mobility, including flight from natural disasters, presented a crucial challenge to state power. Some imperial dynasties failed to come up with an efficient response and collapsed. Others were able to utilize the waves of migration and flow of fugitives by channeling them to the locations where they could be of use for various state projects. Moving large numbers of people was also an efficient instrument for communicating the power of the imperial government to the population at large.Footnote 105

In his study on the resistance to state formation in Southeast Asia, James Scott argues that state spaces were defined less by the topography and natural environment than by the actions of the aspiring state-builders who caged populations within agro-ecologies that people found difficult to escape. A considerable proportion of the populations held in these state spaces were brought in by force as war captives or slaves, but others migrated voluntarily. They could also vote with their feet by out-migrating when the state institutions failed. A state's rise, survival, and fall was closely bound to, even determined by migration management.Footnote 106 Scott's analysis focuses on small “mandala states” in Southeast Asia, but the present study argues that his insights are applicable to greater political formations, the empires, which can be viewed as networks of state spaces created and maintained through state-induced migrations.

Recent scholarship has paid much attention to the enormous scale of coerced state-organized migration during the Qin, which some historians see as the key factor in the fall of China's first empire.Footnote 107 Our calculation of the costs of resettlement projects under the early empires is congruent with this argument, however, we contend that the imperial government's attempts to interfere in human geography were not necessarily harmful. One of our main arguments is that state-induced, rather than state-organized or coerced, migration is an appropriate framework for understanding the relationship between population mobility and empire building. With its limited organizational and financial capacity, the central government was probably unable to thoroughly reshuffle the empire's population, although such measures were certainly conceived and possibly attempted on a more limited territorial scale already in the mid- and late Warring States Qin. What the empires were capable of was maximization of the longer-term impact of state-organized migration projects. The metropolitan region is a case in point. Recorded instances of state-organized resettlements during the imperial Qin and Western Han periods are relatively few and, for the most part, limited in scale. Considering the natural decline in the premodern urban populations, such sporadic resettlements were probably insufficient to maintain high and increasing population numbers in the vast metropolitan agglomeration over many decades. Yet, augmented by state investment in transportation infrastructure, a stable currency, and the removal of political blocks on the movement of goods, people, and information, these resettlements created centers of consumption and socio-economic opportunity that attracted needed inflow of private migration.

Although still in its very early stages, archaeological science, especially isotope studies, have already revealed the complex patterns of relationship between migration and cultural adaptation.Footnote 108 More such studies and multidisciplinary investigation of individual sites will be needed to allow for a reconstruction of a more complete picture not only of the movement of various types of resettlers but also of their integration into host communities and adaptation to local environments. In future, new document finds and more fine-grained archaeological evidence may allow us to identify migrant populations and map the movement of people, goods, and technologies to a degree impossible at present time.

The process of empire-building in East Asia has often been described in terms of “acculturation,” “Sinicization,” or “Hanification.” The point missed by this terminology is that the empire never succeeded in becoming the sole form of connectivity, and its metropolitan culture was never the only point of reference for its subjects in the construction of their identities. Impressive as their monumental architecture and landscape-transforming capacity might have been, state spaces were fragile.Footnote 109 While migrations were a key factor in the formation of state spaces and, consequently, the empire, persons and communities within them could simultaneously participate in other interaction networks, including those competing with the empire. To understand the historical trajectories of each of the state spaces and the empire as a whole, we need take into consideration not only the government policies and origins of populations but also the complex process of identity formation and transformation that informed individual and group decisions about participation in or withdrawal from the imperial interaction network, such as the one that was focused on the metropolitan region. This will be a task for the future studies to come.

Appendix: State-organized resettlements to the capital region, third to first centuries BCE