Introduction

Territorial analysis has been an essential aspect of sociological research into organised crime in the mafia mould. Mafias have been characterised by the development of close links with the context in which they operate. Furthermore, the marks of mafia violence are deeply imprinted on the social environment, with the effect that many traces of its presence can be observed (Parini Reference Parini, Mareso and Pepino2008).

Geographical space has many layers of semantic richness: as well as directly territorial meanings, it transmits others of a social, cultural, political and economic nature. City areas and the environments around them are defiled and devastated by mafia groups, who operate with contempt for any norms; they assert their silent authority over local populations as well as exercising an oppressive control over these territories.

Studies of the mafia have of course taken account of the territorial variable. In order to best describe the territorial embeddedness of the mafias, some scholars employ the concept of ‘signoria territoriale’ (territorial dominion), which Umberto Santino has described as ‘the institutional form of mafia rule’ (Chinnici and Santino Reference Chinnici and Santino1991).Footnote 1 This concept highlights the pervasive presence of the mafia, which exerts its authority over every aspect of life, be it economic, social or civil. It is one of the characteristics of mafia activity that challenges the state monopoly of violence. As Renate Siebert has put it, ‘this assertion does not stop at the front door: there is no privacy under mafia rule. Even personal relationships are directed towards the accumulation of wealth and the exercise of mafia authority’ (Reference Siebert1996, 18).

Much more often, geographical territory has been part of the analysis of the mafia phenomenon in both its socioeconomic and its cultural aspects. In regard to the former, the South's economic underdevelopment has been held to be both cause and consequence of the spread of the mafias (Centorrino and Signorino Reference Centorrino and Signorino1997; La Spina Reference La Spina2005). In regard to the latter, reference to territory has been employed in order to analyse its process of reproduction. We might refer to the interpretations that leant towards identifying the mafia with its environment to the extent that its existence was denied, and the idea that the mafia was ‘a difficult industry to export’ because it was ‘heavily dependent on the local environment’ (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993, 251).Footnote 2

Interpretation of mafia organisations has sometimes been marked by undue simplification of the spatial aspect: territory has been seen as inert space, and not as a highly complex system in constant transformation. This article takes a different approach; it belongs to the school of thinking that in recent years has restated the central importance of territory as an explanatory variable for the mafia phenomenon (Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone2011, Reference Sciarrone2014). A specific implication of this is that we need to consider the characteristics of the territory in which organisations operate at the same time as looking at the behaviour of the actors:

On the one hand, attention is therefore given to those conditions – demographic, socioeconomic, cultural, political and so on – that in varying degrees may favour the spread and establishment of mafia groups within a specific context. On the other, we observe the strategies of the criminal actors, or rather the skills and resources available to them, as well as the rationale for their action. (Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone and Storti2014, 17)Footnote 3

This perspective has proved suitable for interpreting both the complexity of the processes whereby mafia organisations are rooted in ‘traditional’ areas (Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone2011; Brancaccio Reference Brancaccio2017) and the changing nature of the processes of expansion and reproduction in ‘non-traditional’ areas (Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone2014; Martone Reference Martone2017; Sciarrone and Storti Reference Sciarrone and Storti2014; Belloni and Vesco Reference Belloni and Vesco2018).

The intention of this article is to develop the debate under way on the processes by which mafia organisations reproduce themselves, by examining a particular instance of anti-mafia mobilisation by civil society in an area with a marked mafia presence. The focus of this study, which employs innovative methodology, is the impact that the birth of the Addiopizzo movement in Palermo – Sicily's capital and the hub of the criminal organisation Cosa Nostra – has had in the spread of resistance against extortion, embodied in payment of the ‘pizzo’ (‘protection’ money).

As is well known, extortion is one of the most important activities of mafia organisations in general and the Sicilian mafia in particular (Gambetta Reference Gambetta1993; Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone2009; Scaglione Reference Scaglione and La Spina2008; Varese Reference Varese and Paoli2014; Arcidiacono, Palidda and Avola Reference Arcidiacono, Palidda and Avola2016; La Spina and Militello Reference La Spina and Militello2016; Mete Reference Mete2018).Footnote 4 The enforced payment by businesses of the pizzo, especially in areas with a traditional mafia presence, is the fundamental way of confirming control of the territory (Lupo Reference Lupo and Shugaar2009; Santino Reference Santino, Fiandaca and Costantino1994a). However, in recent years the experience of Addiopizzo has contributed to a contraction of the extortion system in the city of Palermo.Footnote 5

In order to assess the impact of the Addiopizzo movement on the territory, this study cross-references geo-spatial data on the spread of its membership and the incidence of extortion. To estimate the spread and intensity of the imposition of extortion in Palermo, it undertakes mapping at two different levels. First, it illustrates the distribution of extortion, whether achieved or only attempted, across the city's many districts during the period between 2004 and 2015.Footnote 6 Second, it compares this to the picture generated by information about traders and business people joining the well-known anti-extortion movement.Footnote 7

To give a foretaste of the results discussed below, although the empirical evidence is partial and incomplete it reveals a heterogeneous picture: some districts were marked by heightened pressure to yield to extortion, while others had lower levels of penetration of this feature of mafia behaviour.Footnote 8 These observations invite a more thorough exploration. The second section describes the main factors, in relation to both context and actor behaviour, that have brought changes to the situation in Palermo in recent years. The third section first discusses the methodology and the limits of the analysis and then presents the research's main outcomes. The fourth and final section presents some concluding thoughts.

Ultimately, the intention of this article is to contribute to the academic debate on extortion and the anti-mafia movement. Although many other articles and books have been published on this topic, I would argue that the construction and analysis of an original empirical database, consisting of information that has not previously been brought together, provides something that is both new and of potential interest.

Causes of the Cosa Nostra crisis

Although the mafia is still well rooted and present across many areas of the city of Palermo and Sicily, the most recent empirical evidence has presented a picture that in some respects differs from that of the past and has important indications of change. It would seem that Cosa Nostra is at the very least in considerable difficulty, if not in actual crisis (Scaglione Reference Scaglione, La Spina, Avitabile, Frazzica, Punzo and Scaglione2013; Fiandaca and Lupo Reference Fiandaca and Lupo2014; La Spina et al. Reference La Spina and Scaglione2015; Visconti Reference Visconti2016; DNA 2017).Footnote 9

To explain the current situation of Sicily's mafia organisation, we need to mention three different factors that have emerged within the last 20 years, two external to Cosa Nostra and one internal: the sustained efforts of the forces of order since the second half of the 1990s; the opposition to extortion payments by a growing number of traders and business people; and Cosa Nostra's failure to carry out an internal reorganisation, which became increasingly urgent after capture of the leading figures in its brotherhood.Footnote 10 These three factors have been interacting, and in different ways can all be held responsible for the current crisis of the mafia system. It will therefore be helpful to analyse each of them in more depth.

In regard to the first factor, the results achieved by the forces of order have been very important:

Since 1990, the police have arrested more than 4,000 members of the Sicilian mafia; more than 200 are under the [heightened] prison regime of Article 41bis [of the 1975 Prison Administration Act, modified in 1992]. According to the 2015 report from the Direzione Investigativa Antimafia (DIA), Cosa Nostra's forces in the province of Palermo consist of 2,366 men. A list compiled at the beginning of 1999 gave more than 3,000. In 1992, there were 152 murders committed by Cosa Nostra; in 2007, there were 9; and in 2016, none at all. (Tondo Reference Tondo2017)

Finally, if we look at confiscated goods, we see that between 1992 and 2018 the state took from Cosa Nostra a vast fortune, with an estimated value of nearly 7 billion euros: more than six times the value of seizures from the Camorra, and almost four times that from the ’Ndrangheta.Footnote 11

In a report published in 2013, the transnational crime research centre at the Catholic University of Milan looked at Italy's three historically important mafias and estimated that Cosa Nostra's average annual revenue (1.87 billion euros) was only about half that of the ’Ndrangheta (3.49 billion) or the Camorra (3.75 billion) (Transcrime 2013).Footnote 12

Two of the most respected scholars of the Sicilian mafia, the lawyer Giovanni Fiandaca and the historian Salvatore Lupo, have commented on its increasing weakness:

Far from being relegitimated and strengthened, [Cosa Nostra] has been becoming progressively weaker as the result of effective action taken against it with a degree of continuity. It could therefore be said that the Sicilian mafia now finds itself in a state of crisis, which is moreover apparent from the comparison with other criminal organisations – such as the Calabrian ’Ndrangheta – that are currently more powerful and dangerous. (Fiandaca and Lupo Reference Fiandaca and Lupo2014, 32)

Turning to the data that reveals the crisis in extortion and the rebellion by businesses, investigations by the Public Prosecutor's office in Palermo have exposed a situation that differs from that of the recent past. Extortion no longer enjoys the widespread and blanket coverage of only a few years earlier (Grasso Reference Grasso and La Spina2008; Bellavia and De Lucia Reference Bellavia and De Lucia2009). Latterly, dozens of businesses have decided to rebel against the mafia and refuse to pay protection money to the gangs (La Spina et al. Reference La Spina, Avitabile, Frazzica, Punzo and Scaglione2013; La Spina et al. Reference La Spina, Frazzica, Punzo and Scaglione2015). The novel element in most recent episodes of attempted extortion is that business people, after years of submission and obstinate silence about their payments, have found the courage to come forward and provide details of the failed coercion.

This response of economic operators burdened by mafia demands was boosted by the birth of the Addiopizzo anti-extortion movement. The story of the ‘Comitato Addiopizzo’ (Addiopizzo Committee) has been thoroughly discussed in the literature, and it may be helpful to provide a brief summary of the key moments (Forno and Gunnarson Reference Forno, Gunnarson, Micheletti and McFarland2010; Mete Reference Mete2014; Di Trapani and Vaccaro Reference Di Trapani and Vaccaro2014). This movement, whose name literally means ‘Goodbye to the extortion payment’, started in 2004, during the night of 28/29 June, when a group of young people in Palermo decided that the way to communicate their statement of protest to the city was to cover the streets with hundreds of small flyers edged in black. What became their slogan, ‘an entire population that pays the pizzo is a population without dignity’, appeared here for the first time.

Out of this anonymous piece of action grew the Addiopizzo movement, which since then has operated from the grassroots and has become the mouthpiece of a ‘cultural revolution’ against the mafia. In a city in which surveys undertaken by trade associations have suggested that around 80 per cent of businesses have been victims of extortion, the reach of its message has been huge (SOS Impresa–Confesercenti 2007; Confcommercio–GfK Eurisko 2007).

The initiative generated a huge outcry, and in 2005 the new movement launched its first awareness-raising campaign with the aim of promoting an indication of resistance against extortion. The following year saw the publication of a list of more than a hundred businesses who were prepared to make public their protest against the pizzo. Within a few years, more than a thousand businesses had joined the movement.Footnote 13 Moreover, the decision to make the list of businesses public related to the wish to involve the general public in a strategy of ‘critical consumption’. In order ‘to pay those who aren't paying’, consumers were invited to purchase goods from outlets that had joined Addiopizzo (Battisti et al. Reference Battisti, Lavezzi, Masserini and Pratesi2018).

Over time, activists within the movement have launched numerous initiatives. In Palermo and its province, Addiopizzo has accumulated the support of more than a thousand businesses and about 13,000 consumers; these numbers can be seen as large in relation to the situation of 20 or 30 years earlier or still small in relation to that of today, but nevertheless constitute an extraordinary indication of change. In the early 1990s, the businessman Libero Grassi's refusal to pay the pizzo resulted in him being sentenced to death, more by omertà and isolation among his own peers than by Cosa Nostra.Footnote 14 Today, however, someone who makes a public complaint knows that they can count on the solidarity of a growing number of their business colleagues.Footnote 15

If businesses are forthright in their complaints, mafia members end up in prison; if on the other hand they refrain, they allow the gangs to strengthen their hold over the territory.

There is no doubt that for many mafia gangs demanding the pizzo has become fraught with danger, and they seem to be increasingly cautious about doing this. Court papers and newspaper stories both provide numerous accounts of mafia members who have given up on enforcing extortion from members of the anti-mafia movement.

Finally, a third mechanism, endogenous to the mafia itself, has helped to throw the extortion system into crisis; this relates to the more general issue of reorganisation of the mafia gangs. The phenomenon of pentitismo, the willingness of mafia members to testify against their own organisation, demolished a wall of omertà within the mafia organisation that had seemed impenetrable. The number of those collaborating with the justice system had fallen in the early 2000s, partly as a result of the toughening of the legislation, but more recently this has been rising again (DNA 2017), despite efforts by Cosa Nostra to stem the flow of pentiti slipping away from it: ‘the recruitment of new members now seems to be much harder, and yet takes place in a way that is much less widely shared and more secret, with a very restricted number of witnesses, for fear of later confessions’ (La Spina Reference La Spina2005, 52).

Apart from the issue of collaboration with the justice system, the criminal capacity of mafia gangs has been compromised by difficulties in recruiting the new intake needed to replace the increasing number of members behind bars. It is clear enough that this is not a quantitative problem, in that any large city has clusters of petty crime that provide a vast reservoir for reorganising the ranks of frontline gangsters who can be called on to commit extortion and other crimes. The Public Prosecutor Pietro Grasso has made this clear:

It is not that the mafia can no longer find initiates. Rather, there is a mass of young people who have no other expectations. This, however, is a labour force suited to killings, collecting the pizzo, and various sorts of dirty work. The difficulty occurs higher up, in the managerial ranks. (Grasso and La Licata Reference Grasso and La Licata2007, 163)

This qualitative deficit is of a much more serious nature, because it can establish people of poor trustworthiness within Cosa Nostra's ranks. A DIA report has commented on this:

The many and significant arrests made by the police forces have effectively pushed the mafia brotherhoods towards making use of new recruits, even for delicate matters; while these have made good the numerical losses suffered and have permitted greater criminal freedom of movement, they have not been able to provide those guarantees of discretion and protection, typical of the true ‘man of honour’, that are necessary for ensuring the secrecy of the mafia's operation and restricting the negative consequences for the group in the wake of any arrests. (DIA 2010, 17)

Moreover, the men of honour themselves have been well aware of this difficult time; the forces of order have taped numerous conversations that touch on this.Footnote 16

Cosa Nostra has been greatly weakened by the decline in the quality of its membership; there seem to be increasingly fewer men who match past standards of professionalism in the provision of supposed ‘protection’, and a greater number of amateurish predators (Punzo Reference Punzo, La Spina, Frazzica, Punzo and Scaglione2015).

There are now increasing numbers of business people who have therefore decided to reject mafia demands and have reported the extortionists to the authorities. However, it would be difficult for Cosa Nostra to give up its extortion activity, because the proceeds have been central to its internal welfare provision and social cohesion, ensuring its survival over time (Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone2009, Reference Sciarrone2011; La Spina Reference La Spina, Siegel and Nelen2008b; La Spina et al. Reference La Spina, Frazzica, Punzo and Scaglione2015). Extortion payments are still very widespread and to fight against them is to do more than just resist their repressive aspect. Furthermore, it should be remembered that this criminal organisation is a long way from being defeated. The mafia clans have been particularly active in the area of business and contracts in order to monopolise receipt of public resources, where the existence of a vast ‘grey area’ has given rise to the development of an extensive and complex system of collusion and corruption which ‘moves away from recourse to threats and intimidation, favouring instead the pursuit of agreements based on mutual benefit’ (DIA 2017, 67). This is also highlighted in a recent report from the Direzione Nazionale Antimafia (DNA 2017).Footnote 17

The empirical research

The spatial mapping of crime has been widely undertaken in both the academic and investigative worlds (Harries Reference Harries1999; Chainey and Ratcliffe Reference Chainey and Ratcliffe2005; Santos Reference Santos2013); its application to the extortion activity of criminal organisations is a useful way of analysing the mafia in its territorial dimension. The shape taken by the information gathered can provide important information on the intensity of mafia demands and can also be related to other variables. Territorial analysis allows us to link the act of extortion to the territory under examination; this is an extraordinary source of information for aiding our understanding of the links between criminal activity and the environment in which it develops.

As already mentioned, this study presents results from the comparative analysis of two different databases. The first is a sort of record of episodes of extortion in different districts within the city of Palermo between 2004 and 2015, both attempted and achieved, that have emerged from enquiries. The data has been gathered from two types of source: on the one hand, court material regarding anti-mafia operations that the forces of order brought to a conclusion in the relevant period, including the mafia ‘libri mastro’ (ledgers); on the other, the columns of local newspapers, featuring news items and articles on attacks and episodes of damage, intimidation and extortion.Footnote 18

The database used represents an enhancement of the information collected during the enquiry by the Fondazione Rocco Chinnici with the title ‘I costi dell'illegalità in Sicilia’ (La Spina Reference La Spina2008b), which was then further developed under the EU-funded ‘Global Dynamics of Extortion Racket Systems’ (GLODERS) project (www.gloders.eu). This database clearly has some problematic aspects, two of which I will mention here. In the first place, as is well known, extortion is a crime whose incidence is substantially hidden; it is difficult for its victims to report it, which means that the statistics collected normally underestimate its actual degree of coverage. The second problem relates to the nature of the sources used, especially the court material. The places where extortion has been uncovered largely correspond to the areas where the forces of order have focused their enquiries. The risk here is that the actual extent of this crime will not be accurately represented in the areas that have not been subjected to long-term and sustained investigative activity.

The database thus constructed includes geo-referencing data on the location of the commercial outlet or business targeted, as well as information on the episodes of extortion. This has enabled the reconstruction of the territorial distribution of this phenomenon with a degree of detail, differentiating the cases in which extortion was accomplished from those where it was not successful. This picture could then be compared with that emerging from analysis of the second database, which has allowed the mapping of the businesses that have joined the Addiopizzo movement.Footnote 19 As mentioned earlier, its launch marked a turning point in the battle against extortion; membership of the movement thus became an effective deterrent against mafia action.

The empirical evidence provides a profile of the phenomenon of extortion that differs in some aspects from the image usually conveyed by the media. The data gathered covers a fairly wide time frame, from 2004 to 2015, which was deliberately chosen to match the start of the action taken by the young people of Addiopizzo.

To be really clear about the impact of the spread of the anti-extortion movement in Palermo, it would have been helpful to have data on the period prior to the emergence of Addiopizzo; the territorial analysis could then have been complemented by a longitudinal evaluation. This gap is a clear limitation of the current study, but also represents a methodological choice. As discussed, the first database comprises incidences of extortion revealed by investigations, and therefore reflects the engagement of the forces of order in identifying crime rather than providing a picture of the actual dimensions of this phenomenon. A before-and-after comparison would certainly have enriched the analysis, but it would not have made these issues any less problematic. Given the absence of a comprehensive database with good geo-spatial information for the period before 2004, it was decided not to try to extend the territorial analysis of extortion into the earlier period.

The first point suggested by analysis of the first database is that extortion is actually achieved in 65 per cent of cases, and thus that more than a third of attempts are unsuccessful.Footnote 20 This is very surprising in the face of the widely held idea that in a city like Palermo it was impossible to resist payment of the pizzo. This important information counters and to some extent weakens the image of Cosa Nostra's pervasive hold on the economy exercised by the blanket imposition of extortion payments. Analysis of the episodes reveals a growing number of cases in which the victims refused to pay, but there were also more instances in which the mafiosi themselves withdrew. Many gang members are now more cautious about demanding payments, and often stop when confronted by their victim's unexpected but stubborn resistance.Footnote 21

The phenomenon of extortion thus no longer has the same level of intensity in Palermo. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical distribution of episodes across the 25 districts of Sicily's capital, with each district graded by intensity in terms of the number of episodes recorded.Footnote 22 Bearing in mind the limitations of the database, discussed earlier, it can certainly not be argued that the situation is less serious where we can see fewer instances, whether successful or only attempted; in view of the hidden nature of the crime, extortion payments in these areas might conversely be even more widespread than in those where more cases have come to light. Furthermore, we should note that there are significant dissimilarities between the different districts.Footnote 23 Although the various parameters may have had a differing impact on extortion, in this study it was decided not to try to adjust the data allowing for the different variables, but to simply focus the analysis on the districts with most cases, bearing in mind that the nature of the empirical evidence means that they are not totally comparable.

Figure 1. Numbers of known extortion episodes, Palermo city districts, 2004–2015.

The districts with the highest empirical evidence of extortion are shown in black in Figure 1. More than 60 per cent of the total of almost 750 cases were in fact recorded within just six districts, the central areas where most of the Sicilian capital's economic activities are concentrated: Tommaso Natale-Sferracavallo, which incorporates the areas with the same names that border the sea and mark the western edge of the metropolitan area; Resuttana-San Lorenzo, an enormous part-residential and part-commercial area that was once the centre of the citrus groves and in the 1960s endured much unregulated building during the ‘sack of Palermo’; Libertà, which takes its name from the wide nineteenth-century boulevard with its Liberty-style villas and elegant shops with big names and prestigious brands; Politeama, the centre of the city; Tribunali-Castellammare, the original centre of the urban settlement; and finally Oreto-Stazione, a densely populated working-class area whose construction started after the Second World War, behind the central railway station, in the city's south-western area.

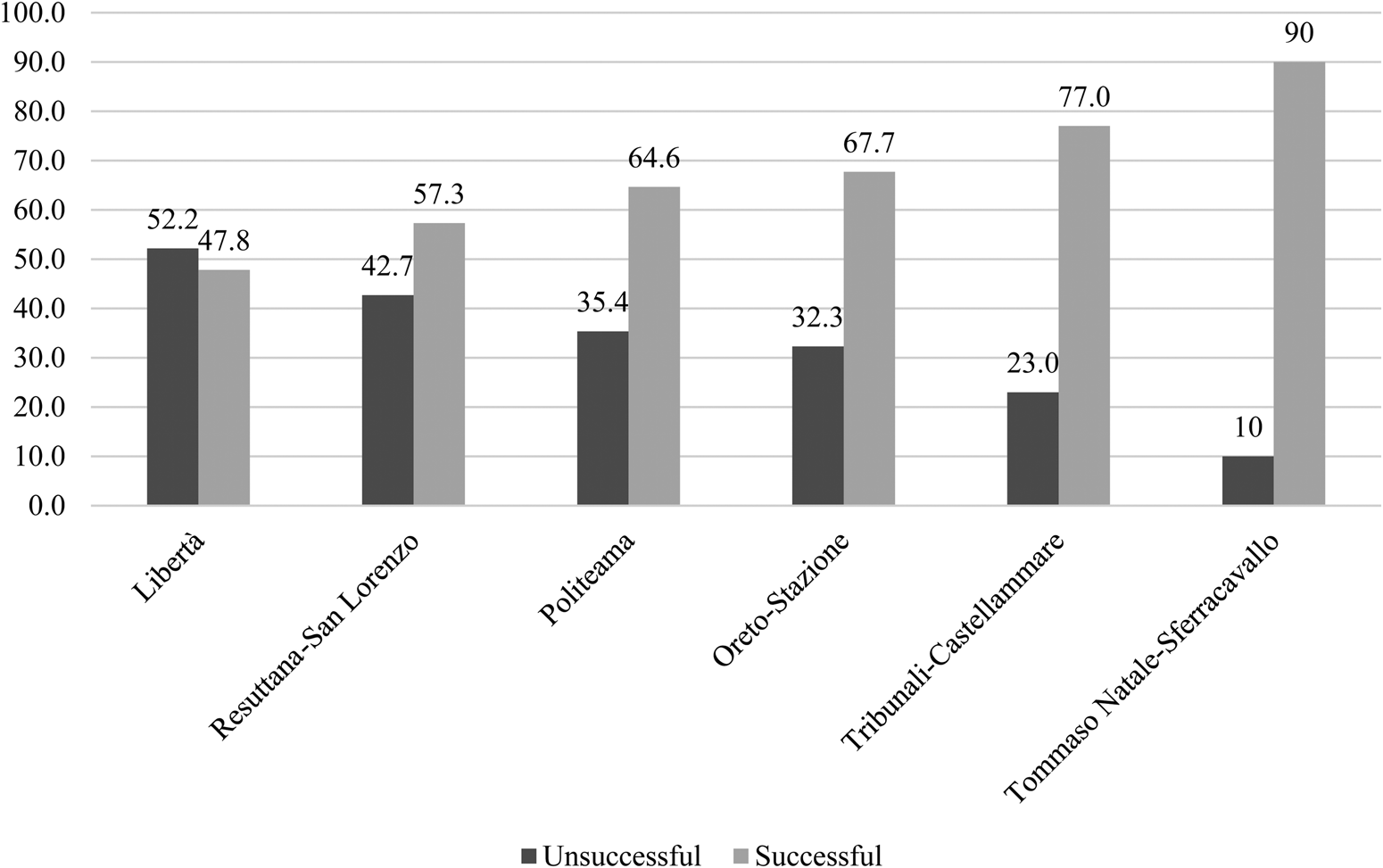

Analysis of these six districts offers a very mixed picture in relation to achievement of the aims of extortion. As can be seen in Figure 2, in some areas the phenomenon seemed to be encountering less resistance, while in others the gangs appeared to be in difficulty, judging from the number of attempts at extortion that had not come to fruition. In the Libertà district, most notably, more than half these attempts met with failure; at the other end of the spectrum, 90 per cent of episodes in the old areas of Tommaso Natale and Sferracavallo concluded with payment of the pizzo.

Figure 2. Proportion of successful and unsuccessful extortion episodes, Palermo city districts with higher numbers of known extortion, 2004–2015 (%).

The data just presented gives an unexpected picture of a situation hovering between subjection and rebellion. The fact that there are significant variations between the different quarters prompts further reflection on the reasons. How can these differences be explained? At this point, before analysing the information in the second database, we can identify the most important explanatory variables.

In this study, as mentioned, we have adopted an analytical process that examines at the same time the interaction between the behaviour of the actors – ‘agency factors’ – and factors relating to the context (Sciarrone Reference Sciarrone2014). Among the agency factors, the activity of the forces of order, whose effectiveness is affected and constrained by the resources available to them, should be singled out first of all. Although this variable is undoubtedly one of the most significant and possibly the most important, on its own it does not explain the variations in extortion activity: in some districts this phenomenon continues to have a powerful presence despite the forceful action taken against it. It could in fact be said that activity by the forces of order does not represent a strong deterrent to the mafia, whose members have factored in the risk of their arrest. It should be noted that the returns from collecting extortion payments, unlike what we know about other criminal activities, are set aside to support those arrested and their families.

Turning our attention towards the strategic approach of the criminal groups, it could also be suggested that in some districts the demand for payments has been deliberately less insistent. However, this theory also seems less than plausible, because extortion, unlike other illicit activities, represents a resource that in principle the mafia gangs cannot give up, in view of the part that it plays in nourishing the relationships of solidarity that underlie the associative bond (Bellavia and De Lucia Reference Bellavia and De Lucia2009).

A third potential explanatory ‘agency factor’ is the behaviour of the victim. The dominant view on this has been put forward by advocates of the theory of rational choice, who regard the decision to pay as the outcome of a simple utilitarian calculation: the result of a cost-benefit analysis. Without debating in detail the merits of this thinking, which has been widely discussed in the literature, there is no doubt that payment would seem a rational choice for some business people.Footnote 24 However, despite an observed reduction in the typical sum of money demanded since the 1990s, a growing number have chosen to rebel against the mafia levies.Footnote 25 On its own, therefore, victim behaviour also fails to account for the territorial variations that have emerged: it cannot explain why the decision to pay the pizzo might be judged rational in one particular district, but irrational in another.Footnote 26

Other factors are clearly also in play. Among those that might influence the decision whether or not to pay, we should consider the contextual factors and especially certain factors of a socio-economic nature. Across the six districts there were wide variations in the levels of unemployment, ranging from only 1 per cent in Politeama to 19 per cent in Oreto-Stazione and Tribunali-Castellammare. The populations resident in these districts were equally different in numerical terms: in Resuttana-San Lorenzo, Libertà and Oreto-Stazione the population density is much higher than in Tribunali-Castellammare and Tommaso Natale-Sferracavallo.

Aspects such as urban degeneration and widespread crime cannot be ignored, although in this regard the gangs have shown that they can adapt to any environment. Payment of the pizzo, however, has always been the norm in Palermo's well-to-do circles just as much as elsewhere. Perceptions of the ‘weakness of the rule of law’ (La Spina Reference La Spina2005; Costabile and Fantozzi Reference Costabile and Fantozzi2012), or even the absence of the state, may certainly increase the insecurity felt by a business person or trader and lower their resistance to the point where they are pushed into assessing extortion payments as ‘rational’ in exchange for a ‘protection’ service. The payment of mafia levies may undoubtedly feel more acceptable in these situations, but in this regard, as well, the districts under consideration are very heterogeneous. This is even more the case when we examine each of them individually: Politeama, for example, has elegant avenues in stark contrast with its areas of urban decay.

In summary, the factors so far considered do not seem able to fully explain the variable nature of extortion. At this point, one further variable can be introduced. We now consider social capital, embodied in this case by the network of relationships fostered by the Addiopizzo anti-extortion movement: another ‘agency factor’ that has had its impact on the situation. Apart from the numbers involved, the movement – through the civic commitment of its volunteers – has undertaken a powerful campaign to raise awareness, which has helped to change the way that both businesses and the wider community think about society (Frazzica Reference Frazzica, La Spina and Militello2016). Associative action, more than any other factor, seems capable of reinforcing the decision to refuse to pay mafia levies.

If we now look at the database regarding Palermo businesses that have joined Addiopizzo, we can see that in total 629 have registered with the movement. Focusing on the districts already singled out for consideration, Figure 3 shows each district's share of unsuccessful extortion attempts in relation to their share of the businesses that have joined Addiopizzo, across the six districts as a whole. The figures show that, in general, the greater the movement's presence, the higher the failure rate of attempts at extortion.

Figure 3. Distribution of unsuccessful extortion episodes (2004–2015) and Addiopizzo membership (2004–2015) across Palermo's districts with high known extortion (% of total for the six districts).

As the image shows, the higher incidence of unsuccessful attempts at extortion occurred in the districts where the movement has had the greatest penetration. In Libertà, Politeama and Resuttana-San Lorenzo, for example, there were higher levels of Addiopizzo membership and episodes of extortion had a lower success rate; by contrast, in the Tommaso Natale-Sferracavallo, Oreto-Stazione and Tribunali-Castellammare districts, where the movement had encountered greater problems, attempts at extortion resulted in payment noticeably more often.

After the other agency and contextual factors have been taken into account, the ‘Addiopizzo’ variable seems to have considerable importance. Given the problematic nature of the data collected, one could logically put forward the theory, counter to the argument advanced so far, that the districts in which the lowest levels of extortion have been recorded are those in which Cosa Nostra is strongest and pressure to pay the pizzo most overwhelming, and therefore that higher levels of Addiopizzo membership are not the causal factor. Ultimately, however, in the districts with the highest membership of Addiopizzo, these figures and the number of failed extortion attempts indicate higher levels of active resistance by businesses; it seems likely that the presence of the movement has upset the previous equilibrium.

In the light of the discussion in the second section, we can acknowledge that Addiopizzo has undoubtedly operated as an effective deterrent. For this to be maintained, however, it will be necessary for the values and practices of the movement to be embedded in society. In sum, the data presented, despite being neither comprehensive nor unproblematic, in my view reflects an interesting set of circumstances for the analysis of mafia operation in its different manifestations, despite certainly not being enough to arrive at a comprehensive assessment of the impact of the anti-mafia movement on the distribution of extortion across the city of Palermo.

Conclusion

Using an original empirical basis, this article has sought to show that the imposition of territorial control can be reversed even in the areas where a criminal presence is most deeply entrenched.

The mafia is an organisation whose strategy is characteristically oriented towards acquiring a position of absolute supremacy within society, devoted to the control and parasitic exploitation of the resources within its territory. It is therefore clear that countering its activity requires more than just concentrating efforts on the crimes committed by its members.

Instead, it is necessary to actually take the territory away from mafia control and to revitalise and reorganise those environments in which a private and violent use of public resources has been embedded and enforced for decades. This use has effectively transformed vast urban areas into ‘a desolate no-man's-land, abandoned and sometimes wilfully despoiled in order to deny the very presence of the state and democracy’ (Parini Reference Parini, Mareso and Pepino2008, 542).Footnote 27

Although the data collected does not allow the hypotheses formulated here to be confirmed, there is no doubt that mafia extortion is in crisis. Cosa Nostra's activity is no longer the efficient and effective protection industry of the past. In the current phase, its organisational capacity has been compromised; it seems increasingly incapable of exercising control over the territory in its customary manner. The Addiopizzo movement has clearly played a decisive part in this. Obviously, the covert nature of extortion leaves a question mark, for this as for other analyses, but the cross-referencing of sources has allowed us to argue that Addiopizzo has probably had a deterrent effect in the short to medium term.

The picture is clearly far more complex than the reconstruction that has been possible in this work. Recent news stories have been full of scandals related to the ‘mafia dell'antimafia’ (mafia of the anti-mafia), as it has been called. Mafia members are well able to hide behind a façade of legality, and the picture just painted may therefore be far from the truth. Moreover, there still exists an uncharted and troubling grey area which needs some serious exploration.

Translated by Stuart Oglethorpe

Notes on contributor

Attilio Scaglione is a lecturer in sociology, working at the Department of Social Sciences of the University of Naples Federico II, Italy.