A large body of research suggests that the stability and deepening of democracy requires strong state institutions (for example, Andersen et al. Reference Andersen2014a; D'Arcy and Nistotskaya Reference D'Arcy and Nistotskaya2017; Fortin Reference Fortin2012; Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2005; Huntington Reference Huntington1968; Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996; Møller and Skaaning Reference Møller and Skaaning2011; Rose and Shin Reference Rose and Shin2001; Tilly Reference Tilly1992). However, there is no general consensus on the ‘state-first’ question – that is, whether or not certain state aspects need to be in place in order for democracy to thrive (Andersen, Møller and Skaaning Reference Andersen, Møller and Skaaning2014b; Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2014).

In this letter, we empirically examine the state-first argument. Our point of departure is that the state-first literature is characterized by fundamental conceptual and theoretical imprecisions and disagreements, and has traditionally lacked valid measures of the state with large temporal and spatial scopes, which makes it hard to identify the association with other factors, such as democracy (see Andersen, Møller and Skaaning Reference Andersen, Møller and Skaaning2014b; Gjerlow et al. Reference Gjerlow2018; Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2014).

We identify eight of the most popular versions of the argument, focusing on how two aspects of the state – state capacity and bureaucratic quality – relate to democratic survival and deepening in separate ways, either through their status at the time of the democratic transition (what we term ‘level at transition’ arguments) or through the year-to-year impact during the democratic spell (what we term ‘running impact’ arguments). We then empirically interrogate these arguments by matching each argument with the appropriate measures and estimation. Using the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset v9 (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2019b), we include indicators of state capacity, bureaucratic quality and polyarchy with a global coverage from 1789 to 2015. Our analysis thus covers the entire era of modern democracy, including the European and post-colonial case universes with contrasting trajectories of state and regime. The fine-grained measures of V-Dem and the long time series enable better tests of different state effects, regime outcomes and the processes that connect them.

We find stable support across regions for substantial, positive effects of bureaucratic quality, as indicated by a rigorous and impartial public administration, on both democratic survival and deepening. The effects hold when considering levels of bureaucratic quality at the time of the democratic transition as well as year-to-year changes in bureaucratic quality. By contrast, we find no stable effects of state capacity, as indicated by the territorial control of the state apparatus. It follows that the state preconditions democracy in some, but not other, ways: building capacity for territorial control has no (or only small) payoffs, whereas diminishing political polarization by means of bureaucratic quality furthers democratic development in the short and long runs.

Theory

Few studies have systematically investigated the state-first argument; the results from those that have are inconclusive (Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2014). One source of disagreement is that the theoretical understanding of the argument varies widely. Large-n and small-n studies, both classic and more recent, analyze and conflate different aspects of the state (Andersen, Møller and Skaaning Reference Andersen, Møller and Skaaning2014b; Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2014). In addition, the understanding of the causal process that connects state and democracy varies widely (Gjerlow et al. Reference Gjerlow2018). Finally, extant large-n studies typically focus on recent developments or specific regions due to measures that are temporally or spatially limited (Andersen et al. Reference Andersen2014a).

We narrow the scope of our investigations in three ways, thus covering the main versions of the state-first argument. First, we define democracy as polyarchy, that is, the procedure by which governments are chosen in contested, inclusive elections based on freedom of expression and association. This excludes the rule of law, which emerges in close interactions between the state and regime rather than in any of these two arenas in isolation (Mazzuca Reference Mazzuca2010). It also implies that we stay within the boundaries of the post-1789 period because we only see the combination of political liberties, contested elections and inclusive suffrage after the French Revolution (Dahl Reference Dahl1971).

Secondly, we consider two kinds of causal processes connecting the state and democracy by comparing democracies' survival and deepening based on either the strength of the state (1) at the time of the transition or (2) year to year throughout the democratic spell. The former comes close to a punctuated equilibrium theory (for example, Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996) where the level of, say, state capacity at the inauguration of democracy freezes and determines that regime's chances of survival. The latter assumes that the state may change under democracy and that these year-to-year changes, even when relatively small, can have a significant and immediate impact on a country's democratic development (for example, Bratton and Chang Reference Bratton and Chang2006).

Thirdly, we define the state as the organization that de facto commands the means of violence and extractive capacities within a clearly demarcated territory. We focus on the effects of state capacity and bureaucratic quality because they represent, respectively, the territorial and administrative aspects of the state (see Andersen et al. Reference Andersen2014a). These effects are also connected to democracy via different causal mechanisms.Footnote 1

State capacity refers to the state's physical and logistic ability to penetrate society and implement decisions (see Tilly Reference Tilly1992). Bureaucratic quality is the rigorous and impartial service of public officials in policy advice and implementation (see Dahlström and Lapuente Reference Dahlström and Lapuente2017). That is, state capacity refers to the territorial presence and strength of state organizations, whereas bureaucratic quality relates to the integrity of public officials' behaviour.Footnote 2

We expect the two aspects to produce different mechanisms with positive effects on democratic development. State capacity decreases the risk of democratic breakdown because it strengthens the ability to penetrate and police political extremist organizations and makes it harder for secessionists to build strongholds in the territorial periphery and gain access to the mainstream political system (for example, Tilly Reference Tilly2007). State capacity also furthers democratic deepening because it decreases economic transaction costs and increases tax revenues, which supports long-term economic development. This strengthens the regime's performance legitimacy, which is important for further institutionalizing polyarchy (for example, D'Arcy and Nistotskaya Reference D'Arcy and Nistotskaya2017).

Bureaucratic quality decreases the risk of democratic breakdown because impartial bureaucracies are less likely to be captured by political interests and less inclined to be politically biased in delivering public goods like civil rights, health care, education and social transfers. Such bureaucracies oppose interparty or general political polarization and brutal fighting over the control of the state apparatus, which would otherwise incentivize incumbent takeovers and military coups d’état (for example, Cornell and Lapuente Reference Cornell and Lapuente2014).

The impartial delivery of public goods and the facilitation of cross-cleavage dialogue also have downstream effects on democratic deepening. If the impartiality of the bureaucracy in the hands of political opponents is trusted, the costs of free and inclusive political competition decrease. In turn, the initial in-groups will be less inclined to reject the enfranchisement of new groups and install barriers to civil and political liberties for certain groups (for example, O'Donnell Reference O'Donnell2010; Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017).

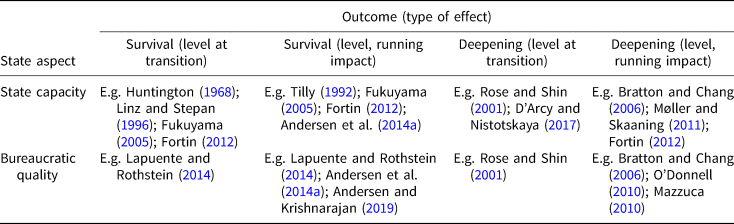

These arguments share the notion of ‘state first’ but underline different aspects of the state and different effects on democratic survival and deepening. If, for instance, bureaucratic quality effects trump state capacity effects, it is because the mediation of political conflicts and the quality of public goods delivery are relatively more important drivers of democratic development than policing and communication to the periphery. The arguments also differ between emphasizing state effects on a running basis throughout the democratic spell or by levels of state strength at the moment of democratic transition. This amounts to eight different versions of the state-first argument summarized in Table 1, which includes studies explicitly framed as contributing to the wider state-first literature.

Table 1. Eight versions of the state-first argument

Research Design and Data

Empirical Strategy

To examine the different versions of the state-first argument, we use varieties of the following specification:

where the dependent variable Democratic breakdown/deepeningi,t is either Breakdowni,t, a binary indicator for whether a democratic country i has broken down in year t, or deepeningi,t, a measure of the change in the level of democracy. β is the coefficient quantifying the impact of a given state measure on the likelihood that a democracy is either stable or deepens. To account for time-invariant determinants of state and democracy, we use δ i regional fixed effectsFootnote 3 in the level at transition (henceforth, LT) models and country-fixed effects in the running impact (henceforth RI) models. To control for common time shocks, we employ γ t year-fixed effects. Finally, X is a vector of country-variant (and time-variant) controls that predict both the state measure and democratic breakdown/deepening. All models use country-clustered standard errors. Due to the number of fixed effects, all models are estimated using ordinary least squares regressions. However, we also run robustness tests that estimate breakdown using logit models.Footnote 4 To ensure comparability between the results, we only use country-years where data are available for both state measures.

A large number of factors arguably both cause and are caused by democracy. Including such factors involves the risk of post-treatment bias. We therefore opt for a parsimonious baseline model that relies on fixed effects, and add controls only as robustness tests.

Another core problem when examining the impact of the state on democracy is the possibility of reverse causality (Mazzuca and Munck Reference Mazzuca and Munck2014). In addition to a number of different tests of reverse causality presented later, our LT models measure state aspects before each country's first experience with democracy, which rules out reverse causality. The RI models lag the state measures by one year, which is a less effective strategy to mitigate reverse causality. Therefore, we add regime stock as a control in some of the RI models.

Outcomes

We measure democratic breakdown using the dichotomous indicator of democracy from Boix, Miller and Rosato (Reference Boix, Miller and Rosato2013, henceforth BMR), which requires free and fair elections with at least 50 per cent male suffrage – a reasonable proxy for polyarchy. The variable is coded 1 in years of democratic breakdown, and 0 otherwise. The sample excludes autocratic country-years.

We measure democratic deepening using the electoral democracy index from V-Dem. It measures the extent to which elections are free and fair, political and civil organizations can operate freely, and elections affect the composition of rulers (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2019a, 39). From the original index, we exclude indicators of electoral management body capacity and autonomy, as these may proxy for state institutions. The index is scaled from 0 to 1. Higher values indicate higher levels of democracy. We use variation in the level of democracy after each transition as our outcome.

Main Explanatory Variables

To estimate the impact of the state, the LT models use a country's score on the relevant state measure in the year of the first democratic transition in that country's history according to the BMR measure. The RI models measure the change in the level of the state measure following a country's first democratic transition and lag it by one year relative to the democratic outcome.

To measure state capacity and bureaucratic quality separately, we rely on two indicators from the V-Dem dataset v9. State capacity is captured using the ‘State authority over territory’ variable, which measures the percentage of the territory over which the state has effective control (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2019a, 175). A score of, for instance, 0.5 indicates that the state only effectively controls 50 per cent of the country's territory. We measure bureaucratic quality using the ‘Rigorous and impartial public administration’ (v2clrspcy) variable from V-Dem (Coppedge et al. Reference Coppedge2019a, 162). It is scaled from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating higher levels of rigorous and impartial administration of laws by public officials.

Table 2 presents an overview of the models. The Appendix provides further details on data sources, tests of measurement validity, robustness tests with alternative state indicators and additional details concerning our control variables.

Table 2. Overview of controls by model

Results

Democratic Breakdown

Table 3 presents the results from LT models estimating the likelihood of democratic breakdown. Models 1 and 2 indicate that transition-level state capacity has a positive impact on democratic survival. However, this result disappears when we add our additional controls (Model 3). By contrast, having greater levels of bureaucratic quality predicts subsequent democratic survival (Models 4–5), a result that is robust to adding the controls (Model 6). When further adding both state measures as controls of each other's effects, the impact of bureaucratic quality remains significant while the impact of state capacity is insignificant (Model 7).

Table 3. LT models of democratic breakdown

Note: standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

To ensure that our results are not driven by specific regional effects, we rerun Models 2 and 5, excluding each region in turn. The results stay the same (see Appendix Figure A3).

Table 4 shows RI models estimating the likelihood of democratic breakdown. The relationships largely mirror the LT results. There is no association between changes in the level of state capacity following a country's first democratic transition and the likelihood of democratic breakdown. By contrast, a substantial and significant negative correlation between positive changes in post-transition bureaucratic quality and democratic breakdown is evident in Models 4–7. As before, these results are similar across excluded regions (see Appendix Figure A4).

Table 4. RI models of democratic breakdown

Note: standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The results so far seem to indicate that bureaucratic quality is the relatively more important state aspect. However, this may be an artefact of a conditioning effect of state capacity on bureaucratic quality (see Tilly Reference Tilly1992). We therefore add an interaction term between state capacity and bureaucratic quality to the above models (both LT and RI), but find no robust results (see Appendix Table A3).

Further, we use the Lexical Index of Electoral Democracy (henceforth LIED) as an alternative measure of democratic breakdown by employing the scale's level corresponding to competitive, multiparty elections with full male or female suffrage (Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevicius Reference Skaaning, Gerring and Bartusevicius2015). The correlation between the LIED and BMR measures is relatively high (Pearson's R of 0.83) but may still provide different estimates. However, using the LIED measure does not alter the findings (see Appendix Figure A5). Appendix Figure A6 further shows that the robust effect of bureaucratic quality is substantially important.

Democratic Deepening

Table 5 presents LT models that estimate the relationship between the transition levels of the two state aspects and democratic deepening. Models 3, 6 and 7 include a control for the level of democracy on the electoral democracy index at the time of each transition to account for possible convergence effects. Models 1–3 and 7 show that transition levels of state capacity have no robust association with post-transition improvements in the level of democracy. Conversely, Models 4–7 show that higher transition levels of bureaucratic quality are positively related to post-transition changes in levels of democracy. Thus, the results suggest that bureaucratic quality furthers democratic deepening while state capacity does not.

Table 5. LT models of democratic deepening

Note: outcome is changes in the ‘Electoral democracy index’ since each transition to democracy. Standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 6 reports equivalent estimates from RI models. As before, we account for convergence effects by including a control for changes in the electoral democracy index at t – 2 (Models 3, 6 and 7). State capacity is significantly related to democratic deepening in Models 1–3 but not in Model 7. Bureaucratic quality has a positive, running impact irrespective of which controls are added (see Models 4–7). The results for democratic deepening remain largely unaltered when each region is excluded in turn (see Appendix Figures A7–A8). Also, we find no consistent support for a conditioning effect of state capacity on the impact of bureaucratic quality (see Appendix Table A4).

Table 6. RI models of democratic deepening

Note: outcome is changes in the ‘Electoral democracy index’ since each transition to democracy. Standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

To investigate whether these results reflect improvements in the level of democracy or merely a reduced likelihood of experiencing negative changes in the level of democracy, we split the outcome into positive and negative changes in the democracy level since the initial democratic transition. We find a robust association between bureaucratic quality and democratic deepening, but not between state capacity and deepening (see Appendix Tables A5–A6).

To alleviate endogeneity concerns, we also instrument state capacity and bureaucratic quality using, respectively, a country's type of terrain and inheritance rule (of land) during pre-industrial times. We find similar results (see Appendix, IV estimation section and Table A7). Finally, to address time dependence we include cubic polynomials and lagged levels of the state measures in different models and estimate generalized method of moments and survival models (see Appendix, Alternative specifications section). All these tests yield similar results.

Conclusion

Based on new and more accurate measures and estimations of state-first arguments, this letter finds stable support for a positive impact of bureaucratic quality on democratic survival and deepening, both at the time of the democratic transition and on an ongoing basis. State capacity, however, has little consistent effect on any of these outcomes, nor does state capacity condition the effects of bureaucratic quality.

These findings suggest that self-reinforcing aspects of democratization are unlikely to substitute for a weak state. Nevertheless, future research should study whether different aspects of democracy strengthen bureaucratic quality, and whether these effects vary across different modulations of the causal process. This will nuance knowledge of possible processes of reinforcement between state and democracy. The findings also show that a general state-first argument conflates fundamentally different state aspects and mechanisms. Building state capacity for territorial control likely yields no (or only small) payoffs, whereas nurturing bureaucratic quality may diminish political polarization and enhance democratic development in the short and long runs.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/O7R8FT and online appendices at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000083.

Acknowledgements

We thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editor for highly constructive comments and suggestions. We also thank participants of the State and Democracy panel at the Annual Meeting of the Danish Political Science Association, 2018, and participants at the 2019 ECPR Joint Sessions workshop on The State-Democracy Nexus in Historical and Comparative Perspective, in particular Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jørgen Møller, Matthew Wilson, Agnes Cornell and Andrej Kokkonen.