Introduction

Upon their arrival in the territory of the Inka Empire (or Tawantinsuyu as it was called in the Quechua language, Morris & Thompson Reference Morris and Thompson1985: 22), the Spanish conquistadors observed that the native peoples of the region worshipped a variety of deities. Some of these were heavenly, such as the Sun (Tayta Inti), the Moon (Mama Killa), the Stars (Qoyllor), and thunder and lightning (Illapa), while others included the earth (Pachamama), the sea (Qochamama), high mountains, caves, lakes and rivers (Montesinos Reference Montesinos1882: 194–95; Molina Reference Molina1947 [1572]: 51; Arriaga Reference Arriaga1968 [1621]: 24). In addition, the Inka also practised ancestor worship (Pizarro Reference Pizarro1965 [1571]: 192). Deities and ancestors were venerated and periodically provided with offerings, which included the sacrifice of domesticated animals. The Inka were convinced that, for example, a good harvest, healthy herds and success in armed conflict could be influenced by the deities and ancestors. Rituals were therefore of vital importance and were conducted on a monthly basis (Guaman Poma Reference Guaman Poma1936 [1613]; Molina Reference Molina1947 [1572]; McEwan Reference McEwan2008: 151–54). Cobo (Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990 [1653]: 8) provides the most informative account of Inka rituals, regarding the Inka as “one of the [peoples] most encumbered with ceremonies, superstitions, idols, and sacrifices”. Cobo (Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990 [1653]: 8) further stressed that the Inka performed “rites and sacrifices with so much determination and so often that practically all the products that they harvested and all the things they made, and even their own children, were consumed in sacrifices”. While the Capacocha ceremonies certainly did involve the sacrifice of children (Guaman Poma Reference Guaman Poma1936 [1613]: 247; Reinhard & Ceruti Reference Reinhard and Ceruti2010), llamas (Lama glama) and guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) were the most frequent sacrificial offerings (Cobo Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990 [1653]: 113).

Although the Spaniards provided the first written accounts of Inka animal sacrifices, they seldom described the specific types of sacrifices made. The most frequently mentioned animal sacrifices featured the slaughter of hundreds of llamas as part of community rituals, culminating in the probable consumption of the llama meat (as suggested by cut marks on the bones). The discovery of large quantities of camelid bones at the main Inka centres, including Tambo Viejo, supports the early reports of mass animal sacrifice. Guaman Poma (Reference Guaman Poma1936 [1613]) noted that during Inka times, huacas (sacred shrines), idols and gods often received llamas and guinea pig offerings. Beyond the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century accounts, however, the evidence for such offerings remained, until recently, unknown.

In 2018, an archaeological excavation was undertaken at the provincial Inka administrative centre of Tambo Viejo in the Acari Valley, Peru (Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Huamaní, Bettcher, Liza, Aylas and Alarcón2020). The expansion of the Inka state resulted in the annexation of new territories; the south coast of Peru was one of the regions brought under Inka control. In each of the valleys of this region, the Inka state established an administrative centre and Tambo Viejo was the one built in the Acari Valley. This excavation resulted in the unprecedented discovery of a number of naturally mummified llamas, as well as guinea pigs (Valdez Reference Valdez2019), deposited as dedicatory sacrifices (offerings). This new evidence demonstrates that the relationship between the Inka and livestock extended beyond the simple provision of meat, and indicates that domesticated animals played a key role in Inka ritual performances and political life. The dedicatory animal offerings demonstrate that the Inka invested resources and social energy to transform the pre-existing local associations of the newly conquered territory into a series of new cultural meanings associated with Inka imperial ideology and religion. Here, we describe and discuss the llama offerings, and propose that this new evidence is indicative of the efforts invested by the Inka state to legitimise its intrusive presence in the region.

Llamas and the Inka state

At the time of the Spanish conquest, llamas were a ubiquitous animal species across Tawantinsuyu. They were known to the Spaniards as carneros or ovejas de la tierra (sheep of the land) (Molina Reference Molina1947 [1572]: 95 & 99; Cieza de León Reference Cieza de León and de Onis1959 [1552]: 102; Cobo Reference Cobo and Hamilton1979 [1653]: 16). Herds of llamas (and alpacas (Lama pacos)) owned by the Inka state reportedly numbered in the millions (Gade Reference Gade and Ochoa1977: 116; Bonavia Reference Bonavia2008: 158; D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy and Shimada2015: 100). Early Spaniards who travelled from Cajamarca (the location of the first encounter between the Inka and the Spanish) to Cuzco—the Inka capital—stated that in “all this land there is much sheep livestock” (Xerez Reference Xerez1968 [1534]: 235; see also Zárate Reference Zárate1968 [1555]: 130). Similarly, during his journey from Cajamarca to Pachacámac—a pre-Inka sanctuary near present-day Lima—Estete (Reference Estete1968 [1534]: 244) observed that “all along the road there is a great number of livestock with herders looking after them”. Murra (Reference Murra1984: 121), reflecting on these early reports, asserted that the “European observers were stunned by the omnipresence” of the camelids, and that by 1567, some local lords “had more than 50 000 head of stock”.

Llamas were key to the Inka economy and religion (Gade Reference Gade and Ochoa1977: 116; Murra Reference Murra1983: 82–83; D‘Altroy Reference D'Altroy2003: 278, Reference D'Altroy and Shimada2015: 108). While both llamas and alpacas provided wool, hide, meat, fuel and fertiliser, llamas specifically were highly valued as beasts of burden (Rowe Reference Rowe and Steward1946: 219; Browman Reference Browman1974: 189). Moreover, llamas were symbols of prestige. Indeed, the Sapa Inka, or ruler, often walked the streets of Cuzco with his white llama (Rowe Reference Rowe and Steward1946: 255; Murra Reference Murra1983: 104; Bonavia Reference Bonavia2008: 159), called napa, which was regarded as a royal insignia. It is also reported that during public festivities, the Inka sang in the presence of a red llama (Guaman Poma Reference Guaman Poma1936 [1613]: 318–19). Consequently, the state devoted considerable time and energy to managing its own llama herds (Polo de Ondegardo Reference Polo de Ondegardo1940 [1561]: 184).

The importance of llamas to the Inka is further highlighted by the fact that these animals were the primary choice for sacrifice (Arriaga Reference Arriaga1968 [1621]: 42; Calancha Reference Calancha1975 [1638]: 850–51; Cobo Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990 [1653]: 113). Inka rituals involved the slaughter of hundreds of llamas, seemingly to provide for great feasts at the conclusion of ritual celebrations. In the month of October, for example, a total of 100 llamas were sacrificed to promote rain (Murra Reference Murra1983: 105), while in February, another 100 black llamas were sacrificed to stop the rain (Zuidema Reference Zuidema, Dover, Seibold and McDowell1992: 22–23). In March, llama sacrifices were made to the mountains and the dead ancestors (Guaman Poma Reference Guaman Poma1936 [1613]: 239–40). Furthermore, many llamas were sacrificed during similar celebrations conducted at Cuzco (Arriaga Reference Arriaga1968 [1621]: 42; Betanzos Reference Betanzos, Hamilton and Buchanan1996 [1557]: 46–47), while other activities, such as maize planting and harvesting, were also occasions for llama sacrifices (Rowe Reference Rowe and Steward1946: 212). It appears that some of these sacrifices were for human consumption.

Although 100 was the preferred number of llamas to be sacrificed in the monthly rituals, stressful periods, such as drought, sickness and war, required the slaughter of thousands of llamas as part of the Capacocha ceremonies (Rostworowski Reference Rostworowski and Rostworowski1988: 79). Finally, the ideal types of llamas for sacrifice were young males of uniform colours (Murra Reference Murra1983: 104). It is crucial to note that, according to Cobo (Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990: 113), brown llamas were sacrificed to the Creator God (Viracocha), white llamas to the Sun, and particoloured (Cobo's term for ‘multi-coloured’) llamas to thunder. Unfortunately, Cobo did not elaborate further on how the offerings to Viracocha and the Sun were conducted, although it appears that he was referring to dedicatory offerings. Nonetheless, the new evidence from Tambo Viejo aligns with his initial observations concerning the colours of animals and the deities to whom they were offered.

Recent research at Tambo Viejo

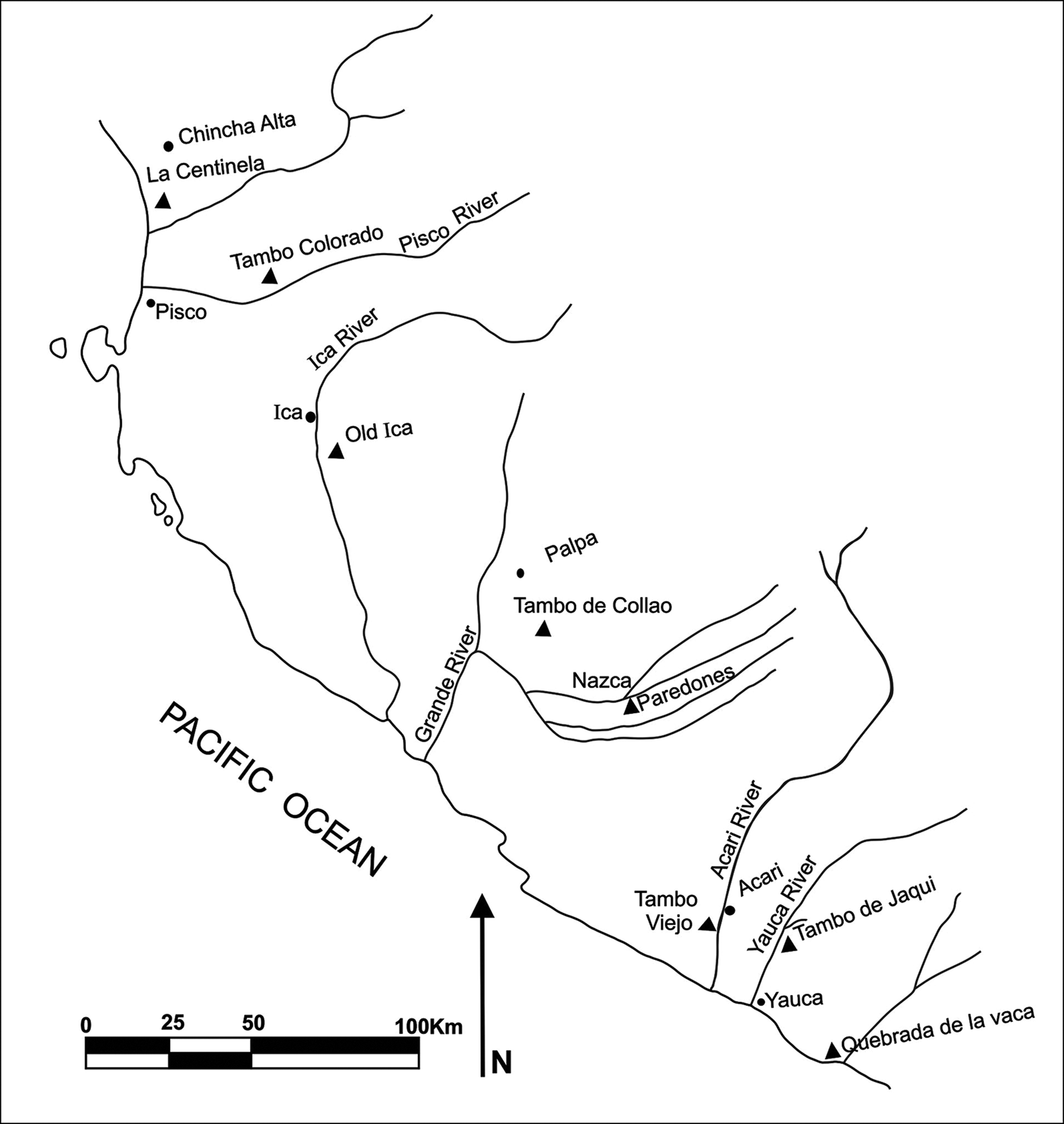

Based on Spanish documents, Menzel (Reference Menzel1959: 126) argued that the southern coast of Peru was peacefully incorporated by the Inka. Subsequently, the Inka state established several administrative centres in the region. Tambo Viejo was one such centre, in the Acari Valley, founded close to an earlier settlement, but in an area with no evidence of previous occupation (Figure 1; Menzel Reference Menzel1959: 129; Valdez Reference Valdez2014). Tambo Viejo's walls were built of cobble stones set in clay mortar and plastered to create a smooth outer surface. This style of construction, known as pirca, was already in use in the Acari Valley long before the arrival of the Inka (Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Huamaní, Bettcher, Liza, Aylas and Alarcón2020). The pirca walls were topped with large rectangular adobe bricks (averaging 0.58 × 0.36 × 0.15m in size) identical to those found at the other Inka centres of the southern coast of Peru (Menzel & Riddell Reference Menzel and Riddell1986; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Huamaní, Bettcher, Liza, Aylas and Alarcón2020).

Figure 1. The location of Tambo Viejo in relation to other Inka centres on the Peruvian south coast (figure prepared by M.A. Liza).

Tambo Viejo was built on an almost perfect north–south alignment (Figure 2; Menzel & Riddell Reference Menzel and Riddell1986: 10). There is a large rectangular plaza (plaza 1) at the northern end of the site and the orientations of all the surrounding structures respect this plaza. These structures include a large rectangular mound built on the eastern side of the plaza that probably represents an Inka ushnu (a structure or feature with a religious and symbolic meaning (Hyslop Reference Hyslop1990: 69)). Furthermore, an important Inka road from the Nazca Valley enters the plaza at its south-west corner. To the south of plaza 1 is a second, smaller, rectangular plaza (plaza 2), around which were established a series of rectangular structures of various sizes. Two of these structures were the focus of excavations in 2018 intended to investigate their form and functions (see also Moore Reference Moore1996).

Figure 2. Map of Tambo Viejo showing the two excavated structures (figure prepared by Benjamin Guerrero).

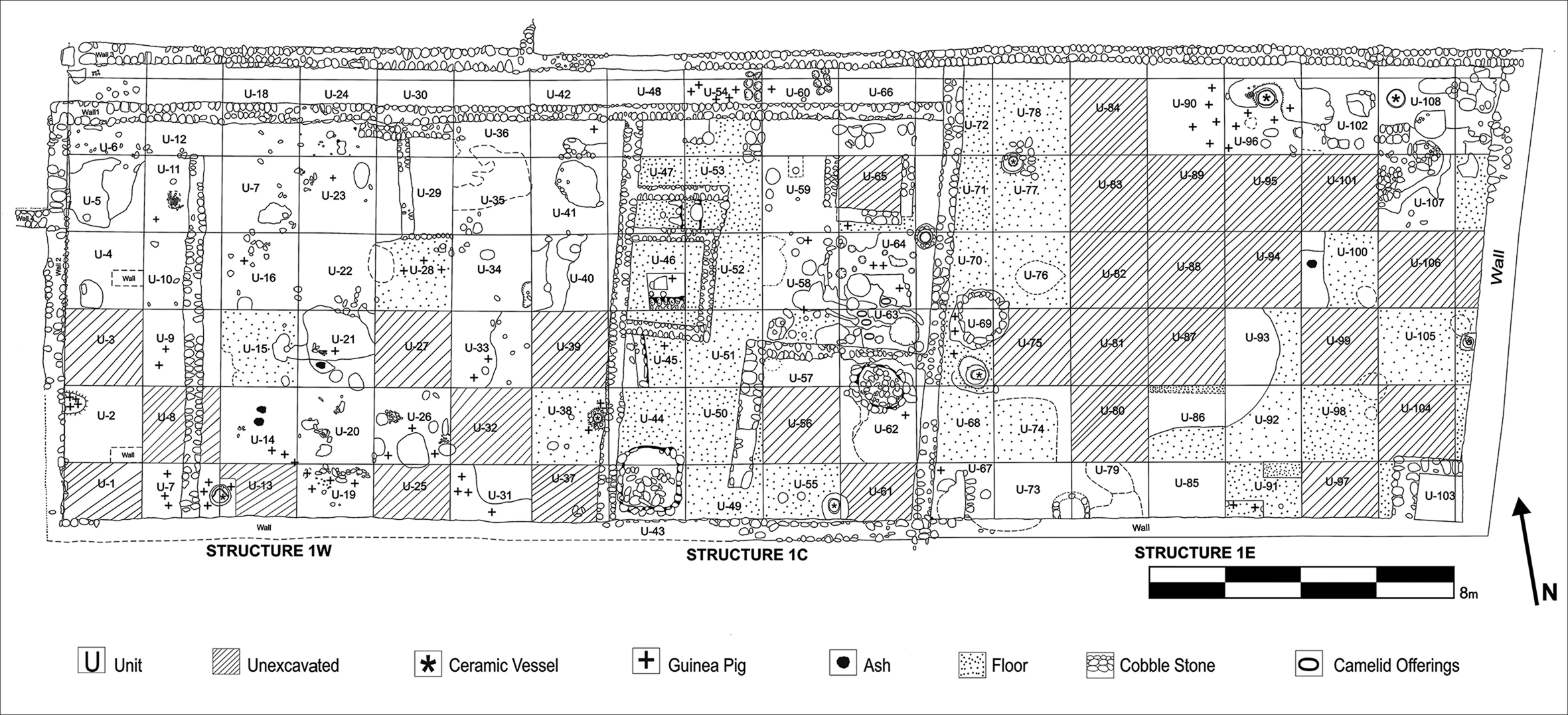

The first excavated building (structure 1 on Figure 2) is located immediately south of plaza 2. This building was modified several times, and, by the time of its abandonment, it had been subdivided into three sections, identified here as: structure 1E (the eastern section), structure 1C (the central section) and structure 1W (the western section) (Figure 3). The building as a whole is a large, rectangular structure occupying almost the entire south side of plaza 2. The second excavated building (structure 2) is located on the northern side of plaza 2. It is much smaller than structure 1, and is divided into two sections, identified here as structure 2N (the northern section) and structure 2S (the southern section). The excavation of these two structures suggests that the final layout of the site was the result of a number of structural changes, indicating that the construction of Tambo Viejo was accompanied by Inka ritual activities, in the form of various dedicatory offerings of types including sacrificed llamas (Valdez Reference Valdez2019).

Figure 3. Map of structure 1 showing the location of the four llama offerings in structure 1C (figure prepared by M.A. Liza).

The llama offerings

Llama burials, placed as dedicatory offerings, were recovered from beneath the floor of both of the excavated structures lining plaza 2. A single brown llama offering, facing to the east, was identified in the central-east portion of structure 2N, and four llamas (one brown, three white) were excavated in the central-east side of structure 1C, all buried side by side, facing to the east (Figure 4). As noted above, brown llamas were sacrificed to Viracocha and white llamas to the Sun (Cobo Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990 [1653]: 113).

Figure 4. The mummified sacrificial llamas found in structure 1C (photograph by L.M. Valdez).

All of the llamas were exceptionally well preserved, apart from the brown llama from structure 1C, which was missing its head and seems to have been moved from its original location. It appears that the area around the brown llama was partially looted. Indeed, prior to excavation, several neonate/infant camelid limb bones, representing a minimum of two animals, were observed on the ground's surface in structure 1C. Subsequently, excavation carried out in the western section of structure 1E (adjacent to structure 1C and separated only by a cobble stone wall) revealed additional neonate/infant camelid bones representing a minimum of three animals. It is notable that a large pit filled with sand and debris was found immediately behind the brown llama. This pit was large enough to accommodate a minimum of four additional infant llamas. A second, empty pit was encountered to the south-east of the southernmost white llama in structure 1C. We can therefore assume that the original number of llama offerings buried inside structure 1C exceeded the four specimens reported here.

As discussed earlier, the ideal llamas for sacrifice were young males of uniform colour (Murra Reference Murra1983: 104), and all of the llama offerings excavated at Tambo Viejo were young individuals. Following the criteria developed by Wheeler (Reference Wheeler1982) for the ageing of llamas and alpacas on the basis of their teeth, we have sought to determine the age of the Tambo Viejo llamas. The brown llama from structure 2N is the largest and oldest of the five. The lower and upper cheek teeth of this specimen indicate that the lower M3 was not yet fully erupted (Figure 5). According to Wheeler (Reference Wheeler1982: 15), M3 eruption completes at around 2 years and 9 months. The brown llama from structure 2N was therefore younger than this age at death. The epiphysis of a long bone accessible without disarticulation of the partially mummified llama is unfused, suggesting that the specimen was a sub-adult.

Figure 5. Mandible of the brown llama from structure 2N (photograph by L.M. Valdez).

The three white llamas from structure 1C were much smaller than the brown llama in structure 2N. Of the three white llamas, the one buried in the middle of the group is the smallest. Its teeth match the dentition of a neonate camelid, as illustrated by Wheeler (Reference Wheeler1982: fig. 1A–B). The other two white llamas also have deciduous teeth, suggesting that they were only a few months old at death. Additional assessment of the epiphyses of the visible long bones reveals that these were unfused. As noted above, the head, and hence also the teeth, of the brown llama from structure 1 was absent, and we therefore could only examine the accessible long bones without disarticulating the partially mummified specimen. Analysis of the long bones revealed that this individual was a sub-adult.

Additional camelid bones representing a minimum of three individuals were found immediately to the east of the four llamas in structure 1C (looters had discarded these bones). The presence of a right mandible with brown fur still attached leaves open the possibility that it could belong to the headless brown llama; the dentition matches that of a neonate lamoid. In addition, we identified a pair of mandibles (right and left) with white fur still attached and with dentition again matching that of a neonate (Figure 6); a further pair of mandibles (right and left) with white fur attached also exhibit neonate dentition. Finally, a skull with grey fur still attached exhibits dentition matching that of a neonate (Figure 7). Although we may never know the exact number of llama offerings originally buried in structure 1C, it is likely that they were all very young animals. Births among domesticated camelids occur anytime between the summer months of January and March (Bonavia Reference Bonavia2008: 47). Given that most of the sacrificed llamas from Tambo Viejo were either neonates or only a few months old, it is possible that rituals involving the sacrifice of the llamas discussed here were carried out sometime during the summer or early autumn (March to May). In the Acari Valley and the southern coast of Peru, late summer and autumn correspond to the harvest period. It is possible, therefore, that the rituals conducted at Tambo Viejo were associated with agriculture. According to Guaman Poma (Reference Guaman Poma1936 [1613]), April was the month during which painted llamas (often painted with a red line over the head and face) were offered to the huacas, idols and gods, while May was the month of the great harvest.

Figure 6. Mandibles of a neonate white camelid found in the western side of structure 1E (photograph by L.M. Valdez).

Figure 7. Skull of a neonate brown camelid found in the western side of structure 1E (photograph by L.M. Valdez).

The llamas selected for sacrifice at Tambo Viejo were elegantly adorned with long, colourful strings made of camelid fibres. The colours of the strings are the same in the case of each animal: red, green, yellow and purple (Figure 8). The strings were attached to the ears as tassels—a practice that has continued into recent times. The longest strings measure 0.36m and were associated with the white llama found next to the brown individual in structure 1C. The shortest strings, measuring 80mm in length, were associated with the brown llama from structure 2N. Additional adornment included colourful necklaces placed around the llamas’ necks. These necklaces were also made of camelid fibres with colours to match the ear tassels. The presence of a further set of colourful strings found next to the disturbed neonate camelid bones reinforces the possibility that the original number of llama offerings was greater than the four llamas reported here. Finally, the adornment of the llamas was completed by face painting. The three white llamas from structure 1C have a red dot on top of their heads and a red line descending from each eye towards the nose. The brown llamas may also have been painted, but no pigment can be identified. After the young llamas were fully adorned and painted, their limbs were flexed under the body and securely tied with a long rope made of camelid fibres (Figure 9) to hold the body in a resting posture (see Figure 4).

Figure 8. Colourful strings that were attached to the ears of the northernmost white llama of structure 1C (photograph by L.M. Valdez).

Figure 9. A mummified white llama from structure 1C bound securely with a rope (photograph by L.M. Valdez).

Early accounts note that sacrificial llamas were often slaughtered by slitting the throat (Malpass Reference Malpass2009: 71). In addition, Guaman Poma's (Reference Guaman Poma1936 [1613]: 880) illustration shows that llamas could be sacrificed by making an incision under the diaphragm, allowing the officiant to remove the beating heart of the animal. Heyerdahl et al. (Reference Heyerdahl, Sandweiss and Narvaez1995: 122) report that this technique, known as cardiectomy, was used to kill the llamas found at Túcume on the north coast of Peru, and Kent et al. (Reference Kent, Tham, Vasquez, Gaither, Bethard, Capriles and Tripcevich2016: 189) report that one Late Moche (pre-Inka, c. AD 550) camelid exhibited a cut mark on the fifth rib that could have been made during a cardiectomy. Other Late Moche camelids “exhibit blunt-force trauma to the head” (Kent et al. Reference Kent, Tham, Vasquez, Gaither, Bethard, Capriles and Tripcevich2016: 189). Similarly, camelids from the pre-Inka site of El Yaral in southern Peru were “killed by a massive blow between the ears” (Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Russel and Redden1995: 834). Our laboratory examination of the well-preserved animals from Tambo Viejo reveals no evidence of cuts to either the throat or the diaphragm, suggesting that the llamas could have been buried alive. The tying of the animals’ legs may also support this interpretation. If correct, this practice would parallel the evidence for the burial of living human sacrifices (Betanzos Reference Betanzos, Hamilton and Buchanan1996 [1557]: 46).

At Tambo Viejo, the sacrificed llamas were deposited in pits dug by breaking through the clay floors that represent the second and final occupation phases of the structures. In structure 1C, the brown llama was buried in the northernmost part of the building, while the three white llamas were buried immediately to the south of the brown llama. Just before burial, a guinea pig was placed above the neck of the northernmost white llama. Furthermore, 0.10m-long sticks with an orange feather from a tropical bird securely tied to one end (Figure 10) were placed vertically next to the eyes of each of the three white llamas as an additional ornament. While it is possible that the brown llama was similarly adorned, later looting precludes confirmation. A similar ornament, with a feather still tied to an end, was found in association with the disturbed young camelids. Finally, a handful of black lima beans was deposited in front of the southernmost white llama. Once all the necessary components had been positioned in the graves, people would have pushed down on the llamas’ necks while clean sand was poured over the animals. A layer of clay was then spread over the sand in order to both seal the offerings and repair the floor surface. The presence of the naturally mummified llamas clearly indicates that these were not sacrifices intended for consumption. Based on Cobo's (Reference Cobo and Hamilton1990 [1653]: 113) report, it can be asserted that these llamas were offerings to Viracocha the Creator and to the Sun, the most important Inka deity.

Figure 10. Orange feathers of tropical birds had been tied to one end of a wooden stick and placed as decorations for the white llamas from structure 1C; these two were found in association with the white llama from the centre (see Figure 4; photograph by L.M. Valdez).

A number of charcoal samples were collected during the excavation. One sample was taken from the context of the middle white llama in structure 1C and produced a calibrated radiocarbon date ranging between AD 1432 and 1459 (at 95.4% confidence; median AD 1447). This and the other dates from elsewhere within structures 1 and 2 are earlier than the assumed date of the Inka conquest, which, according to Rowe (Reference Rowe1945: 277), took place c. AD 1476. If these radiometric dates are accurate, it appears that the Inka arrived in the Acari Valley much earlier than 1476.

In addition to the pits cut beneath the floors for the sacrificial llamas in structure 1C, a series of small holes were purposely made in the hard clay floor to hold deposits of maize cobs, lima beans and guinea pigs. An additional offering within a small hole consisted of a small package of ash wrapped in a piece of cloth. The ash appears to be toqra (or lime), specially made for use in coca chewing. It is possible that the rituals conducted at Tambo Viejo included the chewing of coca and the drinking of maize beer. Although no coca leaves have been found, excavation inside structure 2S yielded coca seeds, indicating that the plant was locally available. A bag to carry coca leaves was also found at the south-east corner of structure 1E.

In structure 1C, two narrow channels, oriented east–west, run immediately behind the location of the three white llamas. Although the purpose of these channels is uncertain, the sacrifice of the llamas perhaps included libations of chicha (a fermented beverage with a low alcohol content, usually made from maize). Finally, adjacent to the llama offerings in structure 1A was a large earthen oven. Its presence suggests that ritual celebrations culminated in the sharing of food in the form of feasts. The size of the oven suggests that food was prepared for a large crowd. Cieza de León (Reference Cieza de León and de Onis1959 [1552]: 191) noted that ritual celebrations included “solemn banquets and drinking feasts”, and this appears to have been the case at Tambo Viejo.

Discussion and conclusion

The evidence from the excavation of structures 1 and 2 at Tambo Viejo can be interpreted to suggest that Inka expansion involved elaborate rituals intended to incorporate conquered peoples and their lands. As the Inka expanded from their Cuzco heartland, they interacted with groups who were culturally and linguistically diverse, and whose final annexation produced the great cultural fusion that characterised the Inka Empire (Morris & Thompson Reference Morris and Thompson1985: 24). The Inka sought to understand the economic potential of the lands and peoples brought into their empire (D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy, Alconini and Covey2018: 214), and to create reciprocal relationships with the newly conquered subjects.

The Inka presence probably disturbed the extant socio-cultural conditions, which the Inka attempted to normalise by befriending the locals and providing gifts and food to the conquered peoples, while also acknowledging the local huacas and gods (Chase Reference Chase, Alconini and Covey2018: 519). The Inka believed that it was not possible to take something without giving something back; this implied that the annexation of peoples and their lands required an exchange to normalise the otherwise abnormal situation. This was especially the case with groups who were annexed peacefully, such as the inhabitants of the Acari Valley (Menzel Reference Menzel1959). Inka recognition of local deities was a necessary step to guarantee a long-lasting relationship between the conquerors and the conquered. To fulfil this requirement, the Inka often adopted local shrines as their own (Morris & von Hagen Reference Morris and von Hagen2011: 44–46), Pachamacac being perhaps the best example of such a practice (Eeckhout & López-Hurtado Reference Eeckhout, López-Hurtado, Alconini and Covey2018).

It remains unclear whether the land within which Tambo Viejo was established had any earlier religious significance. It is evident, however, that the Inka either reinforced its religious connotations or transformed the location into one that was ritually important. As the evidence from Tambo Viejo illustrates, Inka rituals performed in the provinces aimed to project and magnify the importance of Inka ideology and religion, as manifested in the sacrifice of brown llamas to Viracocha and white llamas to the Sun. Such rituals conducted at Tambo Viejo therefore epitomised Inka imperial ideology. The llama and guinea pig (Valdez Reference Valdez2019) offerings are the material manifestations of ritual celebrations performed at the site. Ultimately, all of these ritual acts enabled the Inka to legitimise their presence in the Acari Valley.

Rituals consist of sequences of highly formalised and repetitive behaviour (Richards & Thomas Reference Richards, Thomas, Bradley and Gardiner1984: 191; Rappaport Reference Rappaport1999: 24) performed by highly skilled specialists. The Capacocha rituals, for example, were performed by such specialists (Reinhard & Ceruti Reference Reinhard and Ceruti2010: 123–25), and it is possible that Inka animal sacrifices were similarly organised. It is also quite possible that the associated celebrations included other activities, such as praying, singing and dancing (Marcus Reference Marcus and Kyriakidis2007: 47–48)—actions that do not necessarily leave tangible archaeological evidence. Moreover, these important ritual activities were probably staged in front of local audiences, whose presence was of the utmost importance. Such settings would have permitted the showcasing of the Inka imperial ideology that evoked Viracocha and the Sun. The presence of earthen ovens and associated, partially burned camelid bones (separate from the llama burials) and sweet potatoes at Tambo Viejo suggests that such rituals culminated in feasting, all of which were likely sponsored by the Inka state, as a sign of generosity.

Throughout its history, the Inka state was attached to purposefully constructed special places that were regarded as sacred. From Pacariqtambo to Qorikancha in Cuzco to the sacred, imaginary lines named Zeq'e that radiated from Qorikancha throughout the Inka realm, the Inka created culturally constructed landscapes (Urton Reference Urton1990; Zuidema Reference Zuidema, Dover, Seibold and McDowell1992; D'Altroy Reference D'Altroy2003: 145; Moore Reference Moore2005: 3). Emphasising the long-term Andean tradition of establishing sacred landscapes, some of those spaces had existed long before the Inka, such as Pachacámac (Eeckhout & López-Hurtado Reference Eeckhout, López-Hurtado, Alconini and Covey2018), while many others were newly established. To create spaces rich with meaning and imbued with Inka ideology, the Inka purposely established “culturally specific domains of the sacred” (Swenson Reference Swenson2015: 331) through ritual performances. The sacredness of a place was maintained and reinforced through periodic performances, while the collective participation of the local population created social memory. The ritual ceremonies conducted at Tambo Viejo were actions that not only transformed an existing place into something different, but also served to materialise the presence of the Inka state and its new sacred landscape. The evidence of Inka ritual activities at Tambo Viejo demonstrate the significance of the settlement as a provincial centre of negotiation and control.

The evidence discussed here demonstrates that the annexation of a new region involved ritual performances and the placement of special dedicatory offerings. It is through these measures that the Inka state established and extended its control by manipulating landscapes, animals, sacred places (huacas) and, ultimately, the inhabitants. In doing so, the Inka created new orders, new understandings and meanings that helped to legitimise and justify their actions to both the conquerors and the conquered.

Acknowledgements

Research at Tambo Viejo was carried out with authorisation from the Peruvian Ministerio de Cultura (Resolución Directoral 086-2018/DGPA/VMPCIC/MC). This field research was also possible thanks to the cooperation of many individuals, to whom we extend our gratitude: Wilber Alarcón, Miguel Ángel Liza, Cruver Jayo, Lucie Dausse, Katherinne Aylas, Abel Fernández, Luis Cahuana, Víctor Quintanilla, Yanina Laura, Charmelí Manrique, Nada Valdez, Oscar Bendezú, Valeri Valdez, Mario Ruales, Benjamín Guerrero, Karen Guzmán, Martín Roque, Bryan Guzmán, Modesto Canales, Eber Meléndez, Ángel Iglesias, Rosa Mazuelo and Diana de Cárdenas. The peer reviewers provided valuable comments and suggestions to improve the original manuscript. Any shortcomings are ours.

Funding statement

Funding for the research was provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (grant 435-2017-0478).