As conventions become less sacrosanct with the passage of time, another (hopefully) emerging trend is their reassessment, particularly distinguishing myth from history. Paradigms that have been accepted as historical truth and entrenched in the field by a century of scholarship have been shown to be erroneous.

Michael Aung-ThwinFootnote 1Changing paradigms in Southeast Asian art and archaeology

In a recent article, Michael Aung-Thwin, a prominent historian of Southeast Asia, warns against ‘paradigms that have been accepted as historical truth and entrenched in the field by a century of scholarship’.Footnote 2 Certain old concepts are indeed well-established in Southeast Asian art and archaeology, one case being the assumption that religious affiliations define the political boundaries or the artistic style of ancient kingdoms.Footnote 3 For example, the view which holds that the culture of Dvāravatī was almost exclusively Buddhist, and that of Zhenla Hindu or Brahmanical, remains largely uncontested to this day. But perceptions and precise definitions of what is ‘Buddhist’ and what is ‘Hindu’ or ‘Brahmanical’, and the use of these terms to delineate early Southeast Asian ‘kingdoms’, need to be rethought and questioned.

The transitional period from late prehistory to early history circa the mid-to-late first millennium CE is evidenced by fragmentary inscriptions, numerous religious artefacts and sculptures, as well as the archaeological remains of monumental architecture and cities. It is also a period addressed in the early chronicles written some centuries later. It is finally a period about which there may never be ‘proven’ scenarios, and any interpretation of the data must remain largely hypothetical. The similarities of artefacts and lore found throughout Southeast Asia may suggest cross or common influences, or a commonality of socio-politico-religious ideas, as well as modes of artistic or linguistic expression across the region.Footnote 4 There are, however, a few facts which can be gleaned from the artefacts and inscriptions, and which must be addressed and accommodated in any interpretation. This body of facts, many of which have been documented and published in a recent collective effort,Footnote 5 continues to grow in Thailand and its neighbouring regions. The ‘facts’, however, are not of the ‘historical narrative’ type, but geophysical, scientifically-dated materials, symbolic elements, linguistic data, and so on. They are highly dependent on the source and mode of discovery. Any interpretation of these ‘facts’ requires an interdisciplinary approach and, even when source and discovery are clear, the distinction between ‘fact’ and ‘interpretation’ begins to get difficult and blurred.

In this article, I basically suggest that the use of such cultural labels as ‘Buddhist’, ‘Hindu’, and ‘Brahmanical’ must be qualified and a new way of looking at original sources in early Southeast Asia must be sought. To move forward in the disciplines of art history and archaeology, we need not only to assess or reassess the evidence from raw material, but also to understand and dismantle underlying paradigms which may bias our views of this material. The repercussions of this new approach in art history, religious studies, cultural anthropology, and other related areas, have been and promise to continue to be rewarding, yet ways must still be found for developing new insights that would be impossible were old assumptions retained.

In the following discussion, therefore, my reappraisal challenges the general scholarly opinion on Dvāravatī and Zhenla. This reassessment also tempers and questions the popular compartmentalisation categorising the common people and royal circles as being either ‘Buddhist’ or ‘Hindu’, at the same time emphasising the complex nature of the religion of the age as seen largely through the lens of the ideology of ‘merit’ (Skt, puṇya; P., puñña). That is not to say that the dimensions of power, royal protection, and even violence were unimportant in politico-religious matters during this period, especially at the level of the ruling elites, but the concept of puṇya was clearly essential in both the popular and royal milieus.

In this article, I also examine the religious affiliation, apparent in certain small-scale artefacts such as medallions, and their inscriptions, with merit-making. In so doing, I mainly consider material finds from Dvāravatī — without spontaneously attributing to them a Buddhist affiliation — by comparing these with other evidence found in the neighbouring region of Zhenla and further afield with those prevailing at the time in India, where ‘new Brahmanism’ had come to the fore and the cults of Śiva and Viṣṇu were clearly in ascendance.Footnote 6

However, before I embark on my ‘deconstruction’ of this old theory of religious affiliations, some definitions of what I mean exactly by ‘Dvāravatī’ and ‘Zhenla’ are in order.

Time and space: The relationship between Funan, Zhenla and Dvāravatī

It has been suggested in the past that Funan (扶南) in ancient Cambodia was the catalyst for the development of Dvāravatī in pre-modern Thailand.Footnote 7 As a hypothesis this makes sense, as similar artefacts and sculptures are found in both geographic zones. Legends of Funan, as well as the Chinese annals, support the view that there was a link between the two areas, and that the power of the early coastal Funan rulers, with its legendary links to ‘Indianised’ cultures of the Thai–Malay Peninsula, was presumably displaced by early Khmer inland rulers from about the middle of the sixth or early seventh century CE, that is, just before, or at the beginning of, the rise of what is called ‘Dvāravatī’ and ‘Zhenla’.

‘Dvāravatī’ is commonly used to refer to an archaeological and cultural typology, and an ancient art style (see Murphy, this vol.). In this article, it is predominantly taken to denote a historical polity vaguely located in western-central Thailand around the lower Chao Phraya river valley dated to circa the seventh–eighth centuries. The name has legitimacy in terms of references in the Indic literature, Chinese annals, and in inscriptions found in various sites.Footnote 8 The boundaries of this dominion or maṇḍala named ‘Dvāravatī’ are, however, not stated in early sources, as are the precise locations of many other place-names also found in the Chinese annals. Some earlier scholars have suggested that the area associated with Dvāravatī culture may be divided into two or, perhaps, even three or four zones.Footnote 9 Recent geophysical data and the archaeological distribution of early cities in central ThailandFootnote 10 indeed suggests three zones sufficiently separated to allow them to function independently within the economic and political network of the Pre-Angkorian period, but whether this dichotomy also applies to the sphere of religious art and practices is highly unlikely.

‘Zhenla’ (真臘 or 真蠟), as Michael Vickery notes, is a temporal and areal reference designating ‘Cambodia more or less within its modern borders during the 7th and 8th centuries’.Footnote 11 Possible extensions of Zhenla have also been attested in the southern regions of Laos, the Mun and Chi river basins of northeast Thailand, and in eastern Thailand.Footnote 12 The main difference between the two place-names is that while Dvāravatī is attested in Sanskrit inscriptions discovered locally, Zhenla is a Chinese term for which a convincing reconstruction in Sanskrit or the vernacular is still wanting.Footnote 13 Zhenla was first described in the Suishu (隋書), the seventh-century History of the Sui [Dynasty] and later in the Jiu Tangshu (舊唐書) and the Xin Tangshu (新唐書), that is, the Older and Newer Tang History composed in the tenth to eleventh centuries.Footnote 14 While the political character and geographical location or extent of the Dvāravatī entity is much disputed, the latter Chinese toponym for Zhenla clearly refers to a political domain most likely centred upon the capital city Īśānapura, widely assumed to be today's Sambor Prei Kuk in Kampong Thom province, central Cambodia. But where does Zhenla end, and Dvāravatī begin?

Many more inland, independent, or vassal, ‘Mon-Khmer’ polities also existed in this geographical area besides the above two place-names, especially in the middle Mekong valley and on the Khorat Plateau or its margins (map 1). Robert Brown considers this space an ‘interface region’.Footnote 15 The most important regional polities may have been Si Thep, (Śrī) Cānāśapura, and the much-debated Wendan or rather Wenchan (文單). The latter appears in classical Chinese sources, shortly after the alleged eighth-century disintegration of the former ‘united Zhenla’ into the so-called ‘Land’ (陸) and ‘Water’ (水) Zhenla.Footnote 16 Vickery, however, considers the eighth century a period of consolidation for Zhenla after the seventh century's multitude of small semi-independent entities under local rulers or poñ.Footnote 17

Map 1. Dvāravatī and Zhenla in the 7th–8th centuries

Previously, the ‘Dvāravatī realm’ was largely described and associated with Mon settlements in which Buddhism was significantly and increasingly practised during the second half of the first millennium CE.Footnote 18 Based on the extant literature, Dvāravatī has long been assumed by scholars as almost exclusively a Mon-Buddhist domain,Footnote 19 although there has been a hesitant shift in recent years to argue for Brahmanism or Hinduism alongside Buddhism.Footnote 20 The old view of a ‘Buddhist Dvāravatī kingdom’, however, still persists in academia and museum displays. It has even been propounded by a few that ‘Dvāravatī art’ must exclusively be ‘Buddhist’ and that the Hindu images found in Dvāravatī cultural areas should belong to a separate artistic style.Footnote 21 For instance, the ‘Dvāravatī exhibition’ first held at the Musée Guimet, Paris, and later at the Bangkok National Museum in 2009, was subtitled ‘aux sources du bouddhisme en Thaïlande’, or ‘The early Buddhist art of Thailand’ in its English/Thai version.Footnote 22 The same biased stance has been repeated in the recent catalogue of ‘Lost kingdoms: Hindu–Buddhist sculpture of early Southeast Asia’ exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (14 Apr.–27 Jul. 2014). Particularly misleading, I think, is the claim that ‘state Buddhism’ — an unfitting designation as I shall clarify below — was responsible for the production of a shared ‘Buddhist artistic style’, not only in Dvāravatī central Thailand, but also in other neighbouring ‘city-states’.Footnote 23 Firstly, as Oliver Wolters has shown, the concept of ‘state’ does not really work for Dvāravatī or even other early Southeast Asian political systems;Footnote 24 secondly, there is often no evidence that the rulers of these polities were directly responsible for such artistic production, even on a massive scale, let alone that they were Buddhists.

In contrast, Brahmanism or Hinduism has long been perceived to operate primarily in the eastern margins of this territory, closer to Khmer settlements in Zhenla where followers of Śiva and Viṣṇu, as well as Harihara, a combination of both gods, presumably lived.Footnote 25 A strong proponent of this religious divide in the Chao Phraya river valley is Srisakra Vallibhotama. In his view, the western part (i.e. Dvāravatī) was exclusively Buddhist and the eastern part, centred upon Mueang Si Mahosot, Hindu.Footnote 26 This interpretation, however, goes against the region's archaeological evidence for, as the following will make clear, we find both Buddhist artefacts and inscriptions in the eastern region, and Hindu sculptures in the western zone. Besides the evidence elaborated further below from U Thong, Si Thep, and Nakhon Pathom, I am here thinking of two largely unnoticed early devotional images of Śiva and Viṣṇu from Ratchaburi and Kanchanaburi provinces.Footnote 27

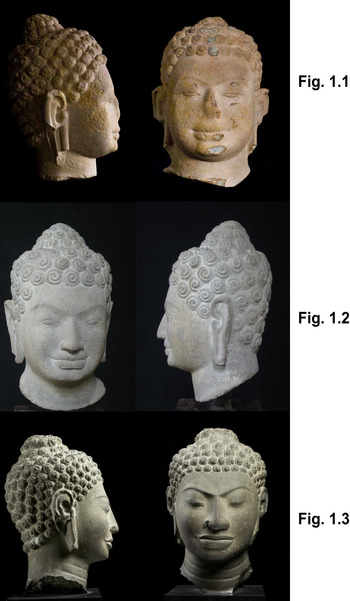

Buddhists are indeed attested in the regions of Mueang Si Mahosot and Zhenla; we have textual, epigraphic, and material evidence of their presence and activities in the seventh and eighth centuries.Footnote 28 Further north, there is also a growing body of Buddhist material found in the middle Mekong valley,Footnote 29 adding to the already rich data excavated from the lower Mekong Delta. Although Buddhism may not have always enjoyed pride of place in these lands, it never really disappears from the sacred landscape.Footnote 30 This early Buddhist sculpture, moreover, often features a common regional idiom and iconography, frequently labelled ‘Dvāravatī’ or ‘Pre-Angkorian’, that seems to transcend the notion of a specific and subregional art style before it becomes more strongly localised in the eighth to ninth centuries onwards.Footnote 31 This is particularly evidenced by the facial and hair treatments of several Buddha heads found in Cambodia, Laos, and Thailand with often lack of precise provenance (fig. 1).Footnote 32

Figure 1. 1.1. Pre-Angkorian and Dvāravatī Buddha heads from Wat Phu Museum, Laos; 1.2. National Museum of Cambodia; 1.3. Bangkok National Museum (Photographs courtesy of Stanislas Fradelizi, National Museum of Cambodia and Thierry Ollivier)

Finally, it is worth noting that the name ‘Dvāravatī’ is also attested in Cambodia in two donative inscriptions (K.89, K.165) from the late tenth, early eleventh centuries which are found in a non-Buddhist environment. Indeed, K.89 (l. 22, 24) records in Old Khmer the ‘gifts’ of persons made to a certain V.K.A. Parameśvara (i.e. Śiva), and K.165 (l. 7–8, 13) the installation of a V.K.A. Śrī Cāmpeśvara (i.e. Viṣṇu) in ‘the land (sruk) of Dvāravatī’,Footnote 33 although it is doubtful that the place-name refers here to the same early polity known in Thailand that is the focus of the present article.Footnote 34

Numismatic and archaeological evidence

Several important discoveries of inscribed medallions of pure silver have been made in Thailand over the past decades. The first medallions were found during the Second World War — albeit only published in the 1960s — in a small earthen jar beneath a now ruined chedi at Noen Hin, near the complex of Chedi Chula Prathon in Nakhon Pathom. These ritual medallions bear identical legends in Sanskrit using late southern Brāhmī characters palaeographically datable to the seventh century.Footnote 35 The reverse reads śrīdvāravatīśvarapuṇya, that is, according to George Cœdès, ‘œuvre méritoire du roi de Śrī Dvāravatī’ or, according to Peter Skilling, ‘merit of the glorious lord of Dvāravatī’ (fig. 2.1, right).Footnote 36

Figure 2. 2.1. Dvāravatī silver medallion found in Khu Bua with auspicious symbol on the obverse (left) and Sanskrit inscription on the reverse (right), Ratchaburi National Museum (Photograph courtesy of Thierry Ollivier); 2.2. Jar containing ritual coins excavated at Khok Chang Din, U Thong National Museum; 2.3. Gold medallion of Īśānavarman (reverse/obverse) reportedly found in Angkor Borei with Sanskrit inscription on both sides, National Bank of Cambodia (Photograph courtesy of Guillaume Epinal)

This formula is quite evocative and reminiscent of another panegyric expression frequently found in India, i.e. dvāravatīpuravarādhiśvara, ‘the overlord of Dvāravatī, the best of cities’, with which the later Yādava kings of Devagiri (tenth–fourteenth century), in particular, prided themselves upon as an epithet.Footnote 37 As we shall see later, the place-name Dvāravatī or Dvārakā (the modern Dwarka), in western Gujarat, was considered the legendary capital of Lord Kṛṣṇa in Indian epic and purāṇic literature.

Indeed, several allusions are made in Sanskrit texts to a legendary ‘city of Dvāravatī’ (dvāravatīpuraṃ); it is also known in Chinese records by a myriad of variant transcriptions (Duheluobodi 杜和羅鉢底; Duoheluo 墮和羅; Duheluo 獨和羅; Duoluobodi 堕羅鉢底; Tuhuoluo 吐火羅), and described as a ‘country’ (guo 国) located between Śrīksetra (Myanmar), to the west, and Īśānapura (Cambodia), to the east.Footnote 38 The parallel occurrence of a certain ‘ruler of Dvāravatī’ (dvāravatipateḥ), found on a stone inscription at Wat Chan Thuek (see infra), confirms that we are dealing with an anonymous lord who may or may not have been the same person as that cited in the silver medallions. Incidentally, Xuanzang (玄奘, c.602–64 CE) and Yijing (義淨, 635–713 CE) give Duoluobodi, which may be restored as ‘Dvārapati’Footnote 39 (the ruler of Dvāra[vatī]?), in lieu of ‘Dvāravatī’.

Other inscribed medallions have been found more recently in the Thai provinces of Nakhon Pathom, Ratchaburi, Suphan Buri, Sing Buri, Lop Buri, and Chai Nat.Footnote 40 As important as these artefacts are for the history of the region and for clearly establishing the presence and location of the elusive Dvāravatī entity somewhere in present-day central Thailand (map 1), their religious character is also apparent due to the likely participation of this ‘lord of Dvāravatī’ in installation rituals (pratiṣṭhā). Because the first inscribed medallions were allegedly found under a chedi in Nakhon Pathom, the assumption has long been that this ‘lord’ must have been a Buddhist ruler and, by extension, that his ‘kingdom’ was a Buddhist domain. The possible association of the chedi with this ‘work of merit’ or pious foundation seemed to confirm in the eyes of many that the religious context was clearly Buddhist. For example, in a very influential article, Jan J. Boeles wrote in 1964: ‘The new evidence [the silver medallions] establishes with certainty a Buddhist king of Śrī Dvāravatī, reigning in the area of Nakorn Pathom in the 7th Century A.D. or 1300 years ago’.Footnote 41

In the following discussion, however, I wish to question the idea that this lord of Dvāravatī would necessarily be a Buddhist ruler or that his meritorious actions were only produced as part of Buddhist foundations. If we turn to ancient India for comparative purposes, the Yādava kings claimed their genealogical descent to Kṛṣṇa and Viṣṇu and, for example, King Bhillama II (r. c.970–1005 CE) styled himself as ‘supreme lord of the city of Dvāravatī’ (dvāravatīpuraparameśvara), and a ‘scion of the race sprung from Viṣṇu’ (viṣṇuvaṃśodbhava).Footnote 42 Earlier on, the imperial rulers of the Sātavāhana, Ikṣvāku, or Gupta-Vākāṭaka dynasties, although they appear at first sight to have been great patrons of Buddhism, were most likely Śaiva or Vaiṣṇava and seemed to have also participated in a variety of Vedic rituals as a means of legitimisation for their power.Footnote 43 In general, ‘royal patronage’ of Buddhist institutions was dwarfed by the quantity if not the scale of gifts given by others, including non-elites and monastic communities. In the early inscriptional record, royal donors were indeed greatly outnumbered by monks, nuns, merchants, bankers, craftspeople, farmers, and other lay people, many of them women.Footnote 44 In Indian Buddhism, kings and royalty, in the main not Buddhists, were thus conceived more as protectors rather than sponsors of Buddhist sacred sites and stūpas. I see no reason for supposing that this was not also the case in early Southeast Asia.

Moreover, the notion of merit-making is not exclusive to Buddhism, as Brahmanism is steeped in the same ideology. Jan Gonda, in a thorough study of the notion of merit-earning in Vedic India, has shown that a principal feature of ancient Vedic sacrifice (yājñā) had been, through the merit thereby generated, the creation of a loka, or sphere of well-being embracing one's activities both in this life and in the world to come.Footnote 45 An illustration of this ancient Indic belief possibly relating puṇya to some kind of ritual involving a pious donation to Brahmins is attested in several yūpa (‘sacrificial post’) inscriptions of King Mūlavarman found in East Kalimantan.Footnote 46 These are amongst the oldest Sanskrit inscriptions in Indonesia, as well as Southeast Asia, and are now datable to approximately the fifth century on palaeographic grounds.Footnote 47 In addition, many inscriptions occur in mainland Southeast Asia where the Sanskrit word puṇya is found in an apparently Brahmanical or Hindu milieu, including one of the oldest stone inscriptions in Sanskrit from Thailand discovered at Si Thep (K.499), Phetchabun province.Footnote 48 In most cases, a king or other high official claims merit for having established a religious (i.e. Śaiva or Vaiṣṇava) foundation or sculpture, or donated to an existing one. It should be borne in mind, however, that the Brahmanical or Hindu concept of puṇya is not necessarily the same as that of the Buddhists. Indeed, the earliest meanings of puṇya in a Vedic or Brahmanical sense appear to be ‘auspicious, propitious, good, virtuous, holy, sacred, etc.’,Footnote 49 where the term was used mainly in a ritual framework, while the Buddhists invested it with a new moral and ethical sense.Footnote 50 In other words, I am inclined to conclude that śrīdvāravatīśvarapuṇya found on the above silver medallions should be understood as Brahmanical Sanskrit, that puṇya should be consistently translated as ‘meritorious work’ (or ‘work of merit’, ‘good deeds’, etc.), and that the so-called lord of Dvāravatī believed that both Hindu and Buddhist foundations constituted meritorious works.

In 1997, indeed, three similar inscribed medallions were scientifically excavated at Khok Chang Din, monument 7, near U Thong, inside a jar containing several other uninscribed ritual coins stuck together along with chopped silver ingots (fig. 2.2).Footnote 51 This archaeological site, however, has only yielded Hindu remains, including a rare stone ekamukhaliṅga (fig. 3.1).Footnote 52 The possibility that this Dvāravatī lord also sponsored the erection of a Śiva-liṅga may indicate the necessity of reaffirming his presence and authority over the area. Interestingly, other Śiva-liṅgas, including one very peculiar ekamukhaliṅga, were found in the same area of U Thong.Footnote 53 Lucien Fournereau equally reported a liṅga and a huge Pre-Angkorian channel or water receptacle (somasūtra) during his late-nineteenth-century visit to the Phra Pathom Chedi in Nakhon Pathom.Footnote 54 Recent excavations by the Fine Arts Department of Thailand (FAD) at the nearby Dvāravatī structure of Wat Thammasala likewise revealed a surprising quadrangular yoni-like base in stone, presumably for erecting a Śiva-liṅga or a Hindu idol inside one of the corner shrines on top of what was previously thought to be exclusively a Buddhist monument (fig. 3.2).Footnote 55

Figure 3. 3.1. Stone ekamukhaliṅga excavated at Khok Chang Din, U Thong National Museum; 3.2. Quadrangular yoni (?) excavated at Wat Thammasala, Nakhon Pathom, in situ; 3.3. Head of a Harihara allegedly found in Chanthaburi province, Prachin Buri National Museum

The above Dvāravatī medallions display on the obverse various auspicious symbols of fertility and prosperity that belong to a shared sacred Indian culture such as the ‘wish-fulfilling cow with its calf’ (kāmadhenū) (fig. 2.1, left). They are, therefore, open to multiple readings and do not give us clues to the exact religious affiliation of our local īśvara or lord of Dvāravatī. Vickery indeed contends from Pre-Angkorian inscriptions that while most of the names ending in -īśvara are deemed to be Śiva followers, a few actually indicate Viṣṇu and some others connote a more general sense of ‘lord’ or ‘temporal ruler’.Footnote 56 A unique gold medallion recently discovered in 2012 in the region of Angkor Borei, Cambodia, however, is less ambiguous in this regard.Footnote 57 The medallion bears an inscription in Sanskrit on both sides. Arlo Griffiths reads these as īśānavarmma[ṇaḥ] on the obverse, and īśānapu(ra) on the reverse, meaning ‘of Īśānavarman’, and ‘Īśānapura [Sambor Prei Kuk]’ (fig. 2.3).Footnote 58 Because of this inscription, the medallion can be identified as the production of this king of Zhenla. The obverse shows a recumbent humped bull which may denote the vehicle of Śiva, from whom the ruler took his official name.Footnote 59 The king also named the city he occupied after the deity.

We also know from other inscriptions that Khmer royalty and elite of the Pre-Angkorian period were generally associated with either Śiva or Viṣṇu, or even perhaps a combination of both, that is Harihara.Footnote 60 This Indic practice of naming or identifying oneself with the Hindu gods, usually Śiva in the form of a liṅga, enhanced the legitimacy of the rulers, facilitated the establishment or restoration of temples to the deities, and even contributed to the creation of what Alexis Sanderson has coined a ‘Śaivization of the land’ in ancient Cambodia.Footnote 61 Furthermore, as Wolters maintains with his concept of ‘men of prowess’, this royal appeal to Indic potent deities in early Southeast Asia also resonated with local understandings of power and influence.Footnote 62 Although power and victory in warfare were certainly the major concerns of kings, these ‘elite-sponsored religious foundations’, as Paul Lavy makes it clear, were also likely important means for local rulers to exert control over a certain area and were liable to be instrumental in the development of early political entities.Footnote 63 As a concrete example, Michael Vickery has shown that King Jayavarman I (c.657–80 CE), said to be a ‘portion’ (aṃśa) of Śiva,Footnote 64 and his immediate successors, also Śaivas, made real efforts to unify Zhenla under their control. Vickery also observed that it was out of this politico-religious context that the practice of establishing edifices as an act of puṇya was instituted in seventh to eighth century Cambodia.Footnote 65

Undeniably, Buddhist sculpture also started to appear widely in central Thailand during the seventh century and Buddhism grew powerfully in the following centuries. Was Buddhist art, however, the fruit of a vast religious and royal feeling in this regional ritual complex? Perhaps the flourishing of Buddhist sculpture in Dvāravatī was not so much the ‘result’ of Buddhist expansion and royal patronage, but one of the ‘means’ through which lay and monastic Buddhism expanded. In other words, a regional programme of Buddhist sculpture may have produced strong visual propaganda, based on powerful economic lay support that gradually transformed the religious landscape.Footnote 66 But comparing the regional evidence from large-scale sculpture with small-scale artefacts like seals, ‘amulets’, medallions and coinage, it becomes obvious that the ‘religious eclecticism’ is reflected in the proliferation of both Buddhist and non-Buddhist deities and symbols. Thus, the early religious interaction between the common people, the ritual specialists, and the ruling elite seems far more complex than had previously been thought or written about and must have been particularly intense during the period of so-called ‘Indianisation’.Footnote 67

Based on the above suppositions, it seems at odds to continue to label the Dvāravatī polity solely as a ‘Buddhist kingdom’ or to speak of ‘state Buddhism’, and a strong case can be built that it experienced the same phenomenon as Zhenla and was largely associated with settlements where Brahmanism or Hinduism was also an important practice amongst its common people or the nobility. Adding to this reasonable statement, Claude Jacques recently suggested that Dvāravatī could be identified with the ancient city of Si Thep, partly because of its well-known affiliation with the early cult of Viṣṇu, or rather Viṣṇu's eighth human manifestation or avatar as Kṛṣṇa.Footnote 68 Indeed, two rare images of Kṛiṣṇa Govardhanadhāra were discovered at Si Thep and are dated respectively to circa the late sixth or the late seventh century (figs. 4.1 and 4.2).Footnote 69 In Indian mythology, Kṛṣṇa is clearly related to the foundation of the legendary capital of Dvārakā or Dvāravatī (also spelt Dvārāvatī), ‘the many-gated [city]’, just like Rāma (Viṣṇu's seventh avatar) is related to the capital city of Ayodhyā. Kṛṣṇa as ‘lord of Dvārakā/Dvāravatī’ is mainly described in the Mahābhārata, the Harivaṃśa, and the Bhāgavatapurāṇa.Footnote 70 It is also significant that the sacred geography of Sanskrit religious classical texts was often replicated in mainland Southeast Asia during the first millennium CE.Footnote 71

Figure 4. Statues of Kṛṣṇa Govardhanadhāra. 4.1 and 4.2 from Si Thep, Bangkok National Museum (Photographs courtesy of Paisarn Piemmettawat); 4.3, 4.4 and 4.5 from Phnom Da and its region (Photographs courtesy of the National Museum of Cambodia and the Cleveland Museum of Art)

But whatever the ultimate location of Dvāravatī was,Footnote 72 these fresh ideas are evidently challenging since, to date, it has been perceived as almost exclusively a Buddhist stronghold. Conversely, this biased assumption echoes another fragile hypothesis concerning the near-demise of Buddhism from Angkor Borei, if not Zhenla, in the late seventh century.Footnote 73 This suggestion is mainly drawn after the ill-informed account of Yijing, travelling in maritime Southeast Asia at the time. Yijing, indeed, spent most of his time in Shilifoshi (室利佛逝 or 屍利佛誓), that is, Śrīvijaya in today's Palembang in Sumatra. He did not visit Zhenla in person and much of his second-hand information was probably inexact or out of date. In any case, the latter Chinese monk recorded numerous Buddhists fleeing ‘the country of Banan’ (跋南, i.e. Zhenla?), formerly known as Funan, and where a ‘wicked king’ was said to have seized power and persecuted all Buddhists.Footnote 74 Be that as it may, in Funan, Zhenla or Dvāravatī, the archaeological evidence gives us a quite different picture of the practice of religion in this unified ritual complex. In the same way as in Si Thep, for example, several ‘Pre-Angkorian’ statues of Buddha and Kṛṣṇa Govardhanadhāra have been found near one another in the region of Angkor Borei/Phnom Da, in southern Cambodia (figs. 4.3, 4.4, 4.5), that is, approximately where the above gold medallion of Īśānavarman was recently discovered (fig. 2.3). Moreover, as Geoff Wade informs us, ‘the religious hybridity of mainland Southeast Asian societies during this period is clearly reflected in the Chinese texts’.Footnote 75

Inscriptional evidence

At this stage, it should be pointed out that all of the inscribed medallions cited earlier and inscriptions to be studied further below were written in Sanskrit. As Sheldon Pollock has magnificently demonstrated, Sanskrit was the language of the gods and royal elite in first-millennium South and Southeast Asia.Footnote 76 Naturally, the sacred use of Sanskrit was also intimately connected with the presence of Brahmins in those regions. Brahmins had always been involved in ‘state affairs’ and royal ceremonies, even if these rituals were sometimes performed in a Buddhist environment.Footnote 77 In Thailand, the participation of Brahmins and Buddhists in joint rituals is probably first attested to in the Wat Maheyong inscription (K.407), said to be from Nakhon Si Thammarat, composed in Sanskrit and datable to around the seventh or eighth century.Footnote 78 In contrast, Pāli or Prakrit was the main language used in Buddhist canonical inscriptions in early mainland Southeast Asia.Footnote 79

A unique panegyric inscription in Sanskrit (praśasti) from central Thailand can be seen in the engraved copper sheet from U Thong (K.964) (fig. 5.1). The inscription may palaeographically be datable to the seventh centuryFootnote 80 and records gifts made to two liṅgas by a certain Harṣavarman, ‘grandson [naptā] of King [rājan] Īśānavarman’.Footnote 81 The possible identity of the latter as the king of the same name ruling over Īśānapura (c. mid-610s–37 CE) is highly interesting and is becoming increasingly accepted among scholars, although one Īśānavarman and two other kings named Harṣavarman, ruling in the tenth century, are also known in Khmer epigraphy.Footnote 82 The real issue is whether the Harṣavarman of K.964, who is said to have obtained the ‘lion throne’ (siṃhāsana) through regular succession, represents a local offspring of seventh- or tenth-century Khmer royalty, in which case the use of naptā may have just meant a ‘descendant’ (nephew?), rather than precisely a ‘grandson’. If the former dating is to be accepted, the precise relationship between this presumed king (varman) and the local lord (īśvara) of Dvāravatī would remain unknown, that is, unless we are dealing with one and the same royal figure. At any rate, one can safely conjecture that these various mainland Southeast Asian polities were probably related through intermarriage, family ties, and/or vassalage. This also involves, quite possibly, a good deal of court intrigue and regional feuds for the sake of royal power or succession.

Figure 5. 5.1. Engraved copper sheet of Harṣavarman with Sanskrit inscription K.964 found in the ancient moat of U Thong, U Thong National Museum; 5.2. Stone inscription in Sanskrit K.1155 found at Ban Phan Dung, Nakhon Ratchasima province, Mahaviravong National Museum

We cannot exclude as well the possibility that the U Thong engraved sheet had been moved from elsewhere (Zhenla?);Footnote 83 yet the production of inscribed copper sheets or plates, although common in ancient India and Indonesia, is unknown in Cambodia to date. However, in spite of the above uncertainties, the evidence from ancient Thailand and Cambodia, both archaeological and epigraphic, sufficiently demonstrates the close relationship between these rulers and the erection and worship of Śiva-liṅgas. At this juncture, one cannot help thinking of Citrasena-Mahendravarman (c.550–611? CE), known as the first king of Zhenla, who is also recorded in the inscriptions to have erected Śiva-liṅgas and the bull as the symbol of his ‘conquest’ over the entire territory.Footnote 84

Subsequently, what might be said about court entourages and consorts? Again if we turn to India, local sovereigns often ruled according to ‘Brahmanical principles’, while support for the Buddhist community and temples frequently came from their wives and ministers, as well as from the laity. This division of ritual responsibilities between male and female representatives of a dynasty seems traditional in ancient India. There is a good deal of evidence that, in general, the king was a Śaiva or Vaiṣṇava, while one of his queens, or his sisters or mother, may have led the congregation of Buddhists (or Jains). The Ikṣvāku rulers of Nāgārjunakoṇḍa, most likely Śaivas, provide an early example from the third century. There, it was Cāṃtasiri, sister of King Cāṃtamūla I (r. c.229–60 CE), who was responsible for patronage of the Buddhist mahācetiya.Footnote 85 Later on, a great school of Buddhist stone sculpture flourished at Sārnāth, in the homeland of the Hindu Gupta kings in northern India. The dedicatory inscription of a fine and rare bronze image of the Buddha from Dhanesar Kherā in Uttar Pradesh, for example, records ‘the deyadharma of Mahādevī the queen of Śrī Harirāja born in the Gupta lineage’. The ruler Harirāja, as his name implies, was probably a Vaiṣṇava ruling in the early sixth century and was married to Queen Mahādevī, a Buddhist supporter.Footnote 86

It could legitimately be argued that the above division clearly speaks about the existence of a cultic and ritual hierarchy, and therefore of a possible divide between Brahmanism and Buddhism in ancient India. Indeed, if the two religions were perceived as both equally ‘effective’, this ritual distinction amongst kings and queens would have probably been meaningless. In all fairness, however, the occasional inversion of roles in Indian society is also indicated. For example, in seventh-century Jajpur, ruled by the Buddhist Bhaumakaras, Śaiva patronage was assigned to the female representatives of the dynasty, when it was Mādhavadevī, wife of King Śubhākara I, who caused the temple of Mādhaveśvara to be built.Footnote 87 Similarly, King Mahāśivagupta Bālārjuna of South Kośala discontinued his mother's adherence to Vaiṣṇavism, in favour of Śaivism and Buddhism, thereby aligning himself with the liberal policy of the rising Pāla king Dharmapāla, his powerful neighbour in the eighth century.Footnote 88 In the same manner, the Pālas were never aligned exclusively with one particular faith, preferring instead to show at least token respect to all.Footnote 89

Back in Thailand, it may be significant that two further inscribed silver medallions, kept in private Thai collections, and unfortunately of uncertain origin, are reported to similarly celebrate ‘meritorious work of the queen of the glorious lord of Dvāravatī’ (śrīdvāravatīśvaradevīpuṇya).Footnote 90 However, a fragmentary seventh-century Sanskrit stone inscription, found on the base of a circular pedestal at Wat Chan Thuek, Nakhon Ratchasima province, and seemingly connected with the installation of a Buddhist image, also makes reference to a certain devī of the ruler of Dvāravatī. The inscription was first deciphered as: sutā(ṃ) dvāravatipateḥ mūrttim asthāpayad devī … īn tāthāgatīm imām, and translated as ‘the queen of the King of Dvāravatī had the daughter installed [sic] this image of the Tathāgata (The Buddha)’.Footnote 91 Not only would this be the first time that a reference to a certain ruler (pati)Footnote 92 and queen (devī) of Dvāravatī had been found on a stone inscription, but it would also form a rare example of the donation of an image of the Buddha as a mūrti,Footnote 93 a term widely used for the Hindu trimūrti composed of Brahmā, Viṣṇu, and Śiva.Footnote 94 Acknowledging the fragmentary nature of the inscription, Skilling nonetheless proposes a slightly different transliteration:

Fragment A: unreadable

Fragment B: xxxxxx -tava | sutā dvāravatīpateḥ |

Fragment C: mūrttim asthāpayad devī | x-īn tāthāgatīm imām ||

and offers a more cautious translation: ‘… daughter of the Lord of Dvāravatī … the queen set up the image … this of the Tathāgata’.Footnote 95 According to this reading, the queen and the daughter would be the same person and not two distinct people. But Jacques, who first deciphered Fragment C (K.1009), read: mūrttim asthāpayad devī-[śr]īn tāthāgatīm imām, tentatively translating it as ‘la princesse a fait installer cette statue de Śrī, qui est adepte du Tathāgata’.Footnote 96 Whether or not the name of the goddess Śrī was intended here, Jacques argued that the image should have commemorated a ‘female deity’, rather than the Tathāgata referred to in the inscription, in which case the meaning of this fragment and its implication for ritual practice remain unclear.

Two slightly later epigraphic examples from the same region of Nakhon Ratchasima indicate an even more complex religious and sociopolitical landscape. The first is K.1155, a Sanskrit inscription dated from the ninth century and found at Ban Phan Dung (fig. 5.2).Footnote 97 It begins with a salutation to Śiva and records the installation of a Harihara and a Viṣṇu image by a certain Śrīvatsa in 718 śaka (796 CE), along with an offering of gifts. Importantly, this is the first time that Harihara is mentioned in the corpus of inscriptions from Thailand although one head from a Harihara sculpture is also known to come from Chanthaburi province (fig. 3.3). Lavy has argued that, during the seventh and eighth centuries, efforts to consolidate political authority by Khmer rulers led to the deployment of this composite deity in ancient Cambodia.Footnote 98 Later on, K.1155 records the establishment of a hermitage (āśrama), as well as the installation of a ‘Buddha’ (sugata) image, possibly by the same donor Śrīvatsa in 747 śaka (825 CE).

A second epigraph, which should be read in conjunction with the previous example from Ban Phan Dung, is the nearby Mueang Sema inscription K.1141, dated 892 śaka or 970 CE.Footnote 99 Its Sanskrit verses recount the previous deterioration of the aforementioned Harihara image, and various other installations, maintaining the same narrative sequence of K.1155. These installations were as follows: a) in 747 śaka, a Buddha (munīndra, sugata), possibly replacing a Śiva (śaṅkara) and which was b) replaced shortly afterwards by a Devī installed by the Brahmin Śrī Śikharasvāmi; and finally c) the erection of a great Śiva-liṅga, replacing the Devī, by a certain king in 761 śaka (839 CE).Footnote 100 This royal liṅga would later be reconsecrated by Śrī Dṛḍhabhaktisiṃhavarman, a provincial governor during the time of Jayavarman V (r. c.968–1001 CE), along with an image of the Tathāgata, through the ‘eye opening’ ceremony.Footnote 101 This devout royal act, indeed, was the raison d’être for the Mueang Sema inscription (K.1141) commemorating more than two hundred years of religious activity at the site.Footnote 102 In these two related inscriptions (K.1141 and K.1155), Hindu deities were installed before and after a Buddha, with no indication that the latter was regarded as superior or inferior to the former ones.

One could legitimately argue that the presence of a Sugata image was necessary in order to cater to the needs of a Buddhist population who frequented the site. Incidentally, Face A of the well-known Bo Ika inscription (K.400), also found in the area of Mueang Sema, records the donation of the ‘glorious lord of Canāśa’ (śrīcanāśeśvara) to the local Buddhist community in hope to achieve bodhi or ‘Enlightenment’. In contrast, Face B of the same inscription, dated 790 śaka (868 CE), is an invocation to Śiva as supreme deity, and records the good deeds (puṇya) of a certain Aṃśadeva for the installation of a golden liṅga.Footnote 103

In Indian Vaiṣṇavism, moreover, the Buddha/Sugata is traditionally viewed as the penultimate incarnation or ‘descent’ (avatāra) of Viṣṇu from heaven to earth in human form to re-establish ‘true Dharma’ (saddharma) and protect worshippers from ‘heretics’.Footnote 104 In doing so, we are told that the ‘Hindu Buddha’ actually teaches heresy (adharma) in order to expertly delude ‘demons’ (i.e. Buddhists) and thus destroy evil.Footnote 105 It is not known for sure if this inclusive religious atmosphere applied to mainland Southeast Asia as in South Asia during the mid-to-late first millennium CE,Footnote 106 but the point I wish to make is that, in certain sociocultural contexts, the dedication of a Buddha image does not necessarily indicate sole adherence to Buddhist teaching and, vice versa, the installation of a Hindu icon in a given shrine does not automatically entail personal devotion (bhakti) towards that deity to the extent of excluding Buddhist practices. Indeed, Sanderson often speaks about an inclusivism of the lay people at the level of ritual and devotional practices in ancient Cambodia, although he differentiates it somewhat from the more elitist milieu of religious specialists, who warned against mixing different ritual systems.Footnote 107

Merit-making: Who holds the monopoly?

It may appear from the foregoing that I have created additional complications with respect to the religious affiliations and practices in pre-modern Southeast Asia to those that were already there. Indeed, these artefacts and selected inscriptions from the Dvāravatī and Zhenla areas seem to conflate ‘doctrinal categories’ that have been typically compartmentalised by scholars as either ‘Buddhist’, ‘Hindu’, or ‘Brahmanical’.

However, I would, on the contrary advocate caution when imposing discrete models on this period based on more modern perceptions, and expectations. For instance, Johannes Bronkhorst has recently warned against such modern attempts to assign Brahmanism to the category of ‘religion’, since, according to him, it represents first and foremost a ‘social order’.Footnote 108 This hypothesis is interesting but needs to be tested in the Southeast Asian environment where Brahmanism (as well as Hinduism) has routinely been classed as a religious practice and belief, not necessarily based on a caste system. For example, Wolters wrote that ‘these Indian representatives of Hinduism [i.e. the Brahmins] in Cambodia are unlikely to have insisted that some form of brahmanical society should be reproduced there’.Footnote 109 This point has also been made by Sanderson who does not consider Brahmanism and Śaivism coextensive but keeps them separated.Footnote 110

At any rate, these ancient Indic belief systems had much in common, interacted continuously, and, generally speaking, coexisted peacefully in pre-modern Southeast Asia.Footnote 111 Sharp, self-conscious, ideological distinctions between these systems may not have been adopted, at least amongst the popular devotional milieu and certain royal circles, until a much later date and may not be present in modern adherents of these religions even today. We have to remember, however, that the texts, many of which have not survived, were written by ritual specialists who had a clear notion of a certain religious divide and were competing for royal support. This of course did not apply to the popular and eclectic milieu and, to a lesser extent, to the royal context. We should thus keep separated the religious and ritual specialists from the lay adherents and rulers, both in the modern and ancient periods.

Indeed, we know of many contemporary cases in Thailand and Cambodia of Hindu images worshipped in Buddhist cultural contexts or by lay people who consider themselves Buddhists and not Hindus. A suitable example would be the royal title of Rāma- (i.e. Viṣṇu's avatar) used by many Buddhist kings of Thailand since the Sukhothai period. As pointed out earlier, however, adherents of Viṣṇu also believe in the Buddhāvatāra and hold him in high esteem. In this context, it may be worth mentioning the national epics of Thailand, Laos and Cambodia, known respectively as Ramakian (‘Glory of Rāma’), Phra Lak Phra Lam, and Reamker, all set up today in a Buddhist environment. In considering whether the Thai Ramakian is ‘essentially Hindu’ or ‘essentially Buddhist’, Frank Reynolds inevitably concludes that it is a ‘Buddhist-oriented Rāma story’.Footnote 112 Similarly in the Khmer Reamker, Rāma's divine nature, whose mission is to lead all creatures to deliverance, is simultaneously perceived as an aspect of Viṣṇu, the Buddha, and a Bodhisattva.Footnote 113

In addition, the archaeological and epigraphic evidence, when studied in its cultural context — that is, the items and placements which are found together — often confirm this assumption of the complex and evolving nature of religion in Southeast Asia since the earliest historical times. Only then can religious artefacts and inscriptions be studied as fragments of rituals and human behaviour, objects of veneration and, as we have seen, products of the ideology of merit. In this vein, it is not surprising to see that the ancient concept of puṇya (‘work of merit’) is shared by both Dvāravatī and Zhenla, be it a predominantly Buddhist, Hindu or Brahmanical culture. As has been pointed out, however, the common terminology shared by these faiths does not mean that such concepts are always understood in the same way.

As regards the role of royalty, Prapod Assavavirulhakarn states in his study of ancient kingship and religion in mainland Southeast Asia, ‘the much-debated issue of whether this or that king was Brahmanical or Buddhist should be dropped’.Footnote 114 Besides, in early India, Jan Gonda affirms that the ‘ideal king’ was not only a political but also a religious figure, a ritual specialist, and a consecrated mediator believed to extend blessings and protection over his country and subjects.Footnote 115 To the same degree, the various rulers and kings of mainland Southeast Asia, past and present, have often resorted to a balanced and efficient policy, supporting all ideologies so long as they bring about merit, power, and blessings for their good deeds. It is also conceivable that royalty similarly applied the same paradigm that the masses did, even if this approach clashed at times with the views and interests of their ritual specialists or official priests (purohitas) of different school affiliations.

Finally, the hypothesis that strong economic and lay support, in addition to royal protection, was also behind the diffusion of this common, joint ideology provides new avenues for interpretation of the social and cultural aspects linked to this religious development. It thus appears necessary to envisage Dvāravatī and Zhenla anew as parts of a ‘transregional ritual complex’, that is, a unified and all-encompassing venue for the ritualistic practice of śāsana/dharma or ‘religion’ in ancient times, with possible emphases varying from locale to locale. Although we cannot determine on the whole whether these ritual and popular practices amongst the nobility and the commoners leaned more towards what we may envisage today as Buddhist, Hindu or Brahmanical, they were probably not totally exclusive.