INTRODUCTION

Excavations and a watching-brief were undertaken by Cotswold Archaeology between November 2013 and August 2014 at 167 Barnwood Road, Barnwood, Gloucestershire, SO 8585 1818. This work was undertaken to satisfy a condition attached to the planning permission for the site's redevelopment. Prior to this it was occupied by buildings associated with a mid-twentieth-century fire station, likely built during the early part of the Second World War. The development area comprised c. 0.2 ha, of which an area of 0.1 ha was excavated in several stages. The site occupies gently sloping land at 25 m OD, to the north of and 200 m from Wootton Brook, a small stream that runs into the river Severn 4 km to the north-west. The bedrock geology comprises Blue Lias and Charmouth Mudstone formations of the Jurassic and Triassic periods. These deposits are overlain by Cheltenham Sand and Gravel deposits.Footnote 1 Compact yellow gravels and sand were encountered throughout the site during the excavation.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The site at 167 Barnwood Road lies immediately north of Barnwood Road, which follows the alignment of Roman Ermin Street, the road which ran from the early legionary fortresses at Kingsholm and Gloucester south-eastwards to Cirencester. The site is situated 2.7 km and 2.8 km to the south-east and east of Kingsholm and Gloucester respectively (fig. 1).

FIG. 1. Site location plan.

Prehistoric and Roman activity has been identified in the Barnwood area, with burials of early Bronze Age, Iron Age and Roman date having previously been recorded.Footnote 2 At Barnwood Cottage, c. 700 m to the south-east of the site, a Roman cemetery was found, containing a variety of inhumations and cremations, with and without urns, dating from the first and second centuries.Footnote 3 The Roman occupation at nearby Gloucester is also well known,Footnote 4 beginning with a legionary fortress at Kingsholm founded in the late a.d. 40s, followed, after its abandonment during the a.d. 60s, by a replacement established close to the present city centre.Footnote 5 This latter was refounded as a colonia by the end of the first century.Footnote 6

Within the immediate vicinity of the excavation site earlier discoveries included Roman pits and ditches and finds of Roman coins and pottery; a coin of Nero was recovered from the site itself during the 1950s. Ermin Street continued to be an important thoroughfare in the medieval and post-medieval periods, while the site lies within the bounds of the village of Barnwood, first attested in the twelfth century.Footnote 7

As a result of the previous discoveries, when a planning application for the site's redevelopment was submitted, Gloucester City Council required an evaluation of its archaeological potential. This comprised a desk-based assessmentFootnote 8 and a trial-trench evaluation, which revealed pits, a ditch and a possible trackway, as well as possible walls aligned with Roman Ermin Street, and pottery dating from the late first/early second century.Footnote 9 In light of these findings a condition was attached to the planning consent requiring excavation prior to the commencement of development. A more detailed stratigraphic narrative of the excavation results and fuller listings of the finds and environmental evidence is available as a grey literature report.Footnote 10

METHODOLOGY

Area excavation was undertaken in stages across the development site following the demolition of the fire station buildings. The timescale of the development and the consequent restrictions on the available space dictated that the site was excavated in a series of separate areas, meaning that the recovered plan was never seen in its entirety at any one time. Topsoil and subsoil were removed from the excavation area by a mechanical excavator equipped with a toothless grading bucket, under archaeological supervision. Exposed archaeological features were hand-excavated to the bottom of archaeological stratigraphy and environmental samples were recovered from deposits where it was believed there was a good chance of the survival of organic material. Features were sampled by hand-excavation at a rate of up to 20 per cent for linear features, 50 per cent for post-holes and pits and 100 per cent for likely funerary/ritual and domestic or industrial deposits.

EXCAVATION RESULTS

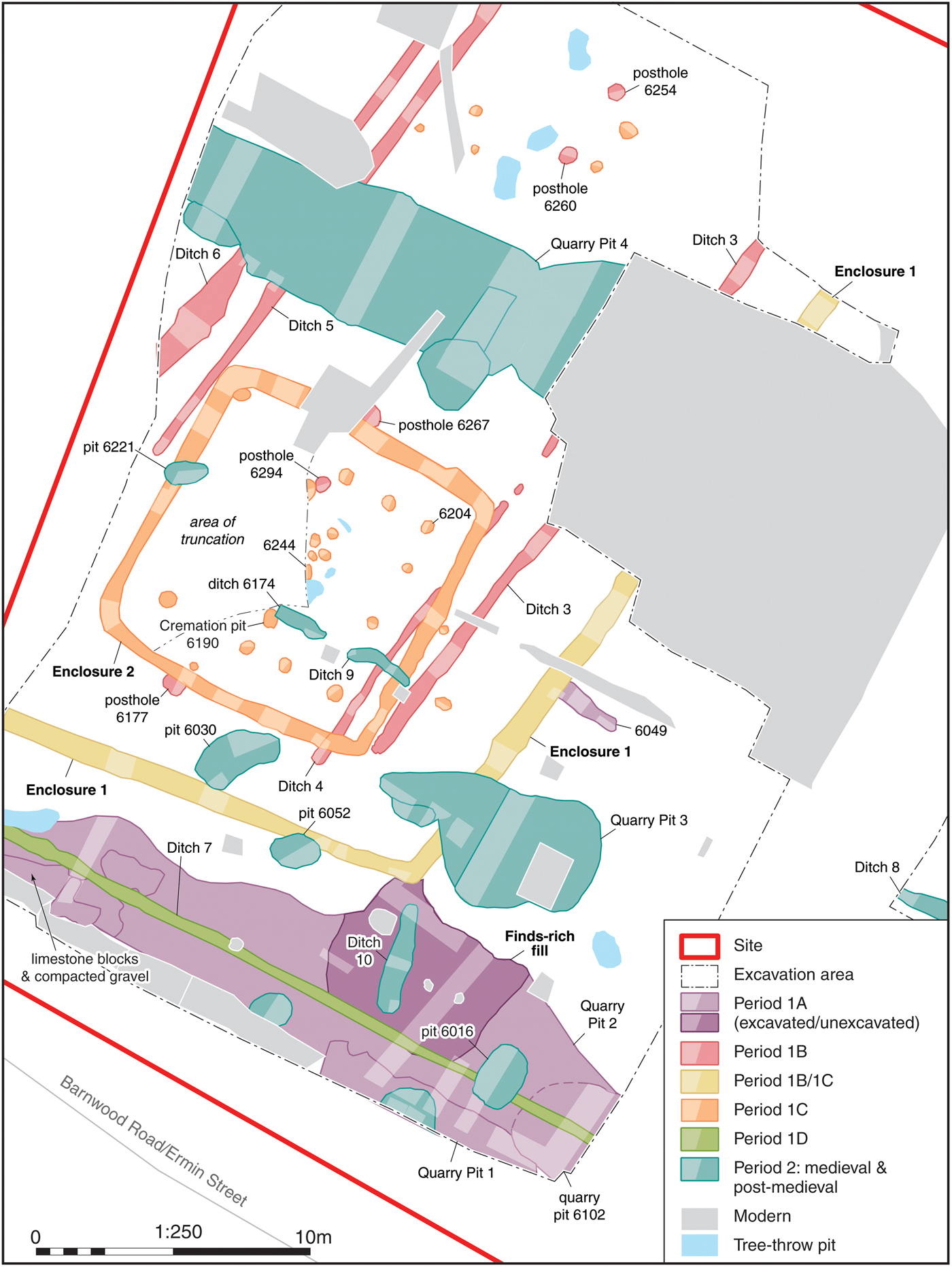

Archaeological features were identified across the excavated area, as well as several ancient tree-throw hollows. There was a particular concentration of early Roman features close to the south-west limit of the site. Features were assigned to periods based on the dates provided by recovered artefacts and their spatial and stratigraphic relationships. Many linear features were truncated, probably a result of ploughing during the medieval and post-medieval periods. The north-west side of Enclosure 2 (discussed below) had also been subject to greater truncation by modern activities than much of the rest of the site.

While the majority of dating evidence recovered was of early Roman date, four worked flints were found redeposited in three different Roman deposits. No other evidence for prehistoric activity was recorded, but the presence of these lithics suggests pre-Roman activity in the immediate area.

Although the stratigraphic relationship between some of the features indicates that there was more than one phase of Roman activity, all the artefactual material recovered was from a relatively restricted date range, primarily dating from the a.d. 60s. While the following phasing is based upon the stratigraphy, there is little to distinguish Periods 1A, 1B and 1C chronologically, and they should be regarded as being of essentially contemporary, Neronian, date.

PERIOD 1A

The earliest activity occurred at the southernmost extent of the excavated area, where two large quarry pits were found (fig. 2). Quarry Pit 1 was partially exposed in plan in the south-east corner of the site. With shallow sides and a flat base, it measured a little over 8.5 m long north-west–south-east, although how far it extended south outside the excavation area is unclear. The pit contained fills of sandy clay which included two sherds of samian, both dating from c. a.d. 40–70, one of which was a base from an unused Dr.27g cup with a complete stamp of Bassus ii-Coelus.

FIG. 2. Phase plan of excavated features.

Quarry Pit 1 was cut along its northern and western edges by Quarry Pit 2, another irregular pit with shallow sides and a flat base, which extended for 26.5 m across the full width of the site, continuing beyond the limits of excavation to the north-west and south-east. As both pits were located immediately to the north-east of Ermin Street (Barnwood Road), it is likely that they relate to gravel quarrying during the construction of the Roman road.

Quarry Pit 2 contained fills of silty sand and clay. Towards the south-east end of the excavated area it contained three very finds-rich fills of silty sand and clay, extending over an area c. 4.5 m in diameter. During excavation these fills were believed to be deposits within a pit which had been cut into Quarry Pit 2. While this is a possibility, as this putative pit was entirely within Quarry Pit 2 and extended to the same depth, it is perhaps more likely that the material represents a localised infilling of the quarry pit with very finds-rich fills. These fills contained large quantities of pre-Flavian South Gaulish samian, amphorae and other pottery, and artefacts, including military fittings and a possible situla jar/camp kettle. Significantly, much of the samian was unused, with the grits used to prevent the vessels from fusing together in the kiln still attached to several of the bases; the presence of the same stamp die on several of the vessels also suggests that the group is dominated by discarded, unused stock and does not represent evidence for domestic occupation. The stamps, the range of forms present and a relative abundance of Lyon ware pottery suggest that the deposit forms a uniform Neronian group, deposited in the a.d. 60s.

At the west of the site a spread of limestone blocks (6091/6092) sealed Quarry Pit 2, which in turn was sealed by compacted gravel, possibly creating an area of hard standing. At the south-east corner of the excavation area Quarry Pit 1 was also cut by a shallow quarry pit (6102). This contained a finds-rich fill of similar date but of markedly different character to that from Quarry Pit 2, being dominated by local pottery, especially Kingsholm fabrics, along with the notable presence of a Malvernian ware jar. Towards the south-east of the excavated area, feature 6049 was a linear cut of uncertain function, orientated north-west–south-east, 2.3 m long, 0.5 m wide and 0.7 m deep. The only find was a bodysherd from a Dressel 20 amphora, but the feature was truncated at its north-west terminus by the ditch of Period 1B/1C Enclosure 1, suggesting it also belonged to Period 1A.

PERIOD 1B

Two sets of parallel ditches (Ditches 3 and 4 and Ditches 5 and 6), aligned south-west–north-east, extended across the excavation area and continued beyond its limits to the north-east. The ditches were aligned perpendicular to Ermin Street, suggesting that they post-dated the construction of the road. There was a gap of c. 1.5 m between the ditches in both pairs, with a distance of c. 6 m between the two sets. An alignment of post-holes (6177/6294/6267/6260/6254), approximately mid-way between the two sets of ditches, shared the same orientation. Pottery recovered from Ditches 3 and 4 was Neronian in date, while a coin (a copy of a Claudian dupondius) also supports a mid-to-late first-century date for them. While the alignment of post-holes produced no dating evidence, post-holes 6177 and 6267 and Ditch 4 were cut by Period 1C Enclosure 2, suggesting that these features with a common alignment were all contemporary. Given the small size and depth of the post-holes (c. 0.3 m in diameter and 0.15 m deep), it is likely they formed a fence line within a land plot defined by the parallel ditches. A number of post-holes at the north of the site were undated, but might have been contemporary.

The ditches and post-holes appeared to have lain within a square or rectangular enclosure of uncertain extent, the south-east corner of which was represented by Enclosure 1. While the relationship between this enclosure and the ditches and post-holes within it is uncertain, their matching alignment suggests that they may have been related; the lack of evidence for such ditches outside the enclosure, to the south-east, may support such a suggestion, although it is possible that further ditches existed outside the excavated area. It is also conceivable, however, that Enclosure 1 was later in origin, constructed at the same time as Period 1C Enclosure 2 (discussed below).

Only two sides of Enclosure 1 were identified, measuring 16 m north-west–south-east and 14 m south-west–north-east, extending outside the excavated area in both directions. The enclosure ditch had moderately sloping sides and a flat base and was c. 1 m wide and 0.4 m deep. It contained a primary fill of brown silty sand and gravel and a secondary fill of silty sand, both with pottery of mid-to-late first-century date, including local pottery in Kingsholm and Severn Valley ware fabrics, along with samian dating from the period c. a.d. 45–70 (thus contemporary with that recovered from Ditches 3 and 4). While the pottery recovered from the ditch fills indicates that Enclosure 1 was broadly contemporary with the deposition of the material in the Period 1A quarry pits, the corner of the enclosure appeared to cut Quarry Pit 2 at its northernmost extent, suggesting that it was somewhat later than the Period 1A features. As noted above, however, it is not certain that the enclosure was constructed in Period 1B as opposed to Period 1C.

PERIOD 1C

Within the south-east corner of Enclosure 1 another square ditched enclosure (Enclosure 2) was created on a broadly similar orientation. Its ditch was c. 0.8 m wide and 0.4 m deep, with moderately sloping sides and a concave base, creating an internal area of c. 10 m by 10 m. It contained primary and secondary fills of silty, sandy gravel and clay, including pre-Flavian pottery. While the two enclosures were clearly related in some way, as previously noted there is ambiguity regarding the sequence in which they were constructed, in particular whether Enclosure 1 was dug at the same time as Enclosure 2, or whether it was of an earlier phase and already extant when Enclosure 2 was created. That the ditches of Enclosure 1 are more closely aligned with the Period 1B parallel ditches than those of Enclosure 2 may favour the latter scenario, although this is by no means conclusive; the Period 1B linear features may merely have been utilised as a guide during the construction of Enclosure 1. What is clear, however, is that Enclosure 2 replaced the Phase 1B ditches and post-hole alignment, as Ditch 4 and post-holes 6177 and 6267 were truncated by the Enclosure 2 ditches.

No evidence for an internal or external bank was identified for Enclosure 2, and within the interior of the enclosure a square alignment of post-holes extended to within 1.3 m of the interior edge of the ditch, suggesting that there would have been insufficient space for an interior bank, especially as only the base of the ditch was revealed in excavation; its original top would have been wider when originally dug.

Post-holes were identified along the south-west, south-east and north-east edges of Enclosure 2, apparently forming a square structure measuring 7 m by 7 m. The lack of post-holes along the north-west side of the enclosure was almost certainly a result of modern truncation. The post-holes were of broadly consistent size, c. 0.4 m in diameter and 0.2 m deep, with steep sides and flat bases. Dressel 20 amphora sherds, dated only broadly to between the first and third centuries, were recovered from post-hole 6204, associated with this internal structure.

Within the centre of this square post-built structure there were a number of undated post-holes and a tree-throw pit, devoid of finds. However, also within this area a lead urn (ossuarium) (fig. 3) was found, containing the cremated remains of an adult human, possibly a mature male (see Supplementary Material, Sections 7 and 11). Osteological analysis of the cremated remains suggested that they comprised at most one third of the individual, indicating that only part of the deceased had been selected for burial, a frequently noted aspect of Roman cremation burials.Footnote 11 Analysis of the skeletal elements present suggested bias towards axial and upper limb bones, particularly those of the right side, with less cranial and lower limb elements than would usually be expected (see Supplementary Material, Section 11). However, as the urn was initially discovered and removed from the ground by the building contractors, who removed the lid, we cannot be certain that all the bone originally included in the ossuarium was available for analysis.

FIG. 3. Photograph of lead funerary urn recovered from Period 1C pit 6190 in Enclosure 2.

Subsequent investigation revealed the original context of the ossuarium as within pit 6190, located in the interior of the post-built structure, at the centre of its south-west side. This pit was markedly distinct from other cut features at the site, being sub-rectangular in shape with vertical sides and a flat base, 0.25 m deep. Located c. 2 m to the north-east, immediately south of the undated post-holes, sub-circular pit 6244 was badly truncated by the contractor's machine, but had vertical sides and a concave base, along with a fill containing charcoal, pottery sherds and two fragments of burnt bone, although it was impossible to determine whether these were of animal or human origin. An environmental sample collected from the pit contained a group of 17 nails and 13 hobnails, as well as the remains of burnt celtic beans, spelt wheat and some barley (although it is possible that the cereal grains were accidently incorporated with cereal chaff or straw used as tinder for a pyre; see Supplementary Material, Section 13). The nails were perhaps from a box or casket and the hobnails suggest the inclusion of nailed footwear on the funerary pyre (although it is unclear whether they were actually worn by the deceased). The fill of this pit either derives from the deliberate sweepings of pyre debris, or else debris from a commemorative ritual.Footnote 12 If the former the observation that the beans appear to have been raw when burnt suggests that they may have been thrown onto the funerary pyre raw rather than being deposited as part of a cooked dish, which thus casts some light on the cremation ritual. Enclosure 2, and the post-built structure within it, were thus part of a burial plot adjacent to Ermin Street.

PERIOD 1D

At the south of the excavated area, Ditch 7 cut Quarry Pit 2. The ditch was aligned north-west–south-east and extended for a distance of 24 m, continuing beyond the excavated area to the south-east. It was c. 0.3 m wide and 0.16 m deep, with steep sides and a concave base. Two sherds of joining samian ware of second-century date (the only second-century samian from the site) were recovered from its backfill, suggesting a second-century or later date for this feature, which was probably a roadside drainage ditch associated with Ermin Street.

PERIOD 2: MEDIEVAL TO POST-MEDIEVAL

At the east of the site, outside the main excavation area, a small additional area of excavation contained Ditch 8 orientated north-west–south-east. It was 1.2 m wide and 0.3 m deep, with shallow sides and a concave base and contained a brown, silty, clayey, sand backfill which included twelfth- to thirteenth-century pottery. In the main excavation area two fragments of a linear ditch (Ditches 9 and 6174) survived along the same alignment and may represent the continuation of Ditch 8. These were undated, but Ditch 9 cut both Period 1B Ditch 4 and Period 1C Enclosure 2, suggesting that it was at least later than the early Roman period. It seems likely that these ditches represent the rear boundary of plots fronting onto Ermin Street. It is possible that north–south Ditch 10, which cut Quarry Pit 2, at the south of the site, was also associated, forming part of a medieval plot boundary. While the only dating evidence recovered from Ditch 10 was first-century pottery, as the ditch truncated the finds-rich fill of Quarry Pit 2, it is highly likely that the pottery was residual. Quarry Pit 3 and pits 6052 and 6030 were all stratigraphically later than Period 1B Enclosure 1, and while twelfth- to thirteenth-century pottery was only recovered from Quarry Pit 3, it is likely that all three features were contemporary. Quarry Pit 3 also contained half of an upper stone from a rotary quern, likely residual from the Roman period and perhaps an import from the Continent (see Supplementary Material, Section 9). Pit 6221, which cut Enclosure 2 on its west side, also contained twelfth- to thirteenth-century pottery as did pit 6016 which cut Quarry Pit 2.

In the northern part of the site a series of linear quarry pits, oriented north-west–south-east (grouped together as Quarry Pit 4), cut Period 1B Ditches 5 and 6. This area of quarrying extended across the excavated area and was c. 5 m wide. The dating evidence from the pits indicates a long period of quarrying activity, with the earliest pottery recovered dating from the twelfth to thirteenth centuries. Quarrying continued during the post-medieval period, with pottery of eighteenth- to early nineteenth-century date recovered from the backfill of one large quarry pit (6337). The quarry pits were of very irregular depth, likely a result of variation in the level of the natural gravels at the site, the deepest being dug to a depth of 1.83 m.

THE FINDS

The following reports discuss the principal finds of interest recovered during the excavation. Methodological details and full catalogues for the artefacts and the biological remains can be found in the Supplementary Material; catalogue numbers refer to those presented in the relevant sections (https://doi.org/10/1017/S0068113X18000272).

SAMIAN By Gwladys Monteil

The samian assemblage recovered from the excavations is very uniform, being almost entirely made up of pre-Flavian South Gaulish material from La Graufesenque, the bulk of which was recovered from one of the fills of a large quarry pit. The presence of grits on almost all of the footrings and of several examples of the same stamp dies clearly indicates the unusual nature and significance of this group. The South Gaulish samian vessels recovered from Quarry Pit 2 are not the result of domestic activities but discarded unused stock.

The following report lists the various strands of evidence provided by the assemblage before discussing its date and significance. Throughout, comparisons with contemporary samian assemblages are made, focusing especially on other stock groups. Illustrations of the samian can be found in the Supplementary Material, online figs 1 and 2.

Assemblage composition

In total the excavation produced 543 sherds of samian ware, weighing c. 4 kg, for a rim EVE figure of 18.37. Only two pieces date to the second century; they are joining sherds from a Central Gaulish decorated bowl form Dr.37, recovered from the fill of Period 1D Ditch 7. The rest of the assemblage is made up of South Gaulish vessels from La Graufesenque, the vast majority of which were recovered from features assigned to Period 1A, particularly the finds-rich fills of Quarry Pit 2, which alone yielded 458 sherds (Table 1). A stamp by Senicio (cat. no. 46) and a few non-joining fragments from decorated vessels in Period 1A Quarry Pit 2 and pit 6102 (cat. nos 2; 31) suggest that the samian from these features is potentially from the same stock group. The comparative analysis, when based on quantified material, focuses solely on the material recovered from the finds-rich fills of Quarry Pit 2.

TABLE 1 QUANTIFICATION OF SAMIAN FROM FEATURES IN PERIOD 1A

Condition

The assemblage is in good condition with little wear or abrasion on the slip; grits are still present on the footrings and nine complete profiles were recorded. There was considerable fragmentation, however, with a relatively low average sherd weight (c. 15 g) and a brokenness index (sherds/EVE) of c. 27 for the samian recovered from the fills in Quarry Pit 2. When compared with contemporary stock groups for which data are available (Table 2), this brokenness index is twice as high as the one for the Colchester Second Pottery Shop, which perhaps suggests that the vessels were purposely smashed up or already broken when deposited, or that this is a secondary deposit. The index for the shop group recovered at One Poultry in London is even higher, but there the material was partly in situ within the shop and partly redeposited in overlying fire debris.Footnote 13

TABLE 2 BROKENNESS INDEX (SHERDS/EVE) FOR DISCARDED SAMIAN STOCKS

(For One Poultry, London, the index is based on data provided in Rayner Reference Rayner2011, table 21; for Colchester Second Pottery Shop the data are taken from Monteil and Silvéréano Reference Monteil and Silvéréano2011)

Stamps

All but two of the 14 name stamps recovered in this assemblage could be identified (online fig. 2; cat. nos 54–63). Eleven were recovered from the finds-rich fills in Quarry Pit 2 and are multiple examples of the same die on the same form by four potters: Senicio (cat. nos 54–63), associated potters Bassus ii-Coelus (cat. nos 57–59, die 6b on Dr.24/25) and a potter who used a known but illiterate stamp (cat. nos 63–65).Footnote 14 An additional two stamps by Bassus ii complete this small collection (cat. nos 55, 56): die 4e on dish form Dr.15/17 and die 15p on cup form Dr.24/25.

Another example of die 2a by Senicio was recovered on a Dr.29 base in quarry pit 6102 (cat. no. 72) and a third stamp by Bassus ii on cup form Dr.27g came from Quarry Pit 1 (cat. no. 54). Both of those are on unused bases like the examples from Quarry Pit 2.

Of the small group of potters represented by the stamps, Senicio has the earliest date rangeFootnote 15 and the die identified at Barnwood Road, 2a, normally appears on vessels in styles ‘ranging from Tiberian to Neronian’. Here, however, the two examples with decoration remaining are associated with bowls in a style more typical of the T-1 group (cat. nos 23 and 28), a stylistic group normally dated to the mid-to-late Neronian period. The vessels from Barnwood Road are important additions to the only other recorded Dr.29 from a T-1 mould with Senicio's die 2a.Footnote 16 The other stamps, by Bassus ii and Bassus ii-Coelus, are Neronian.

There are no direct parallels with the stamps and potters represented in either of the Colchester pottery shops, the One Poultry group in London or a dumped stock group from a defensive ditch at Cirencester, for which no quantification is available;Footnote 17 Senicio is present in the latter but with a different die and on a plain form. This is not unexpected, even in contemporary assemblages, and is probably a reflection of distribution networks.Footnote 18

Decorated ware

Several Dr.29 vessels have decoration with motifs associated with the anonymous T-1 mould maker(s) group;Footnote 19 seven vessels can be linked to this style (cat. nos 13, 14, 23, 24, 27, 28 and 31). T-1 moulds were used by a range of potters to make bowls, particularly by Bassus ii-Coelus and Niger. Indeed, several of the parallels quoted in the catalogue are to vessels with stamps by those potters, a trait shared with the One Poultry shop group.Footnote 20 Perhaps more unexpectedly, two of the Dr.29s in a T-1 style are stamped internally by potter Senicio, but with a die not normally associated with this style (see stamp above). A third example of this association between T-1 and Senicio die 2a is represented by a bodysherd (cat. no. 13) with decoration identical to a bowl from Moers-Asberg.Footnote 21 The final connection to the T-1 group is a Dr.30 with an ovolo known for potter Calus ii and decorative motifs that can be linked to the T-1 group (cat. no. 32).

The other Dr.29s have parallels with vessels with internal stamps by Calvus i and Mommo (cat. no. 8), Masclus (cat. no. 29), Modestus i (cat. no. 25), Primus iii (cat. no. 26) and Manduillus (cat. no. 5). The other Dr.30s for which parallels could be found have links to potter Sabinus iii (cat. nos 33, 38–41 and 43). Sabinus iii is dated a.d. 50–80 by Hartley and DickinsonFootnote 22 and the two ovolos represented here are more common between a.d. 50 and 70.Footnote 23 A Dr.30 with decoration almost identical to one from Barnwood Road (cat. no. 33) was part of a discarded stock group from the early fortress at York,Footnote 24 so his wares were still being distributed in the later Neronian and early Flavian period.

Forms

The range of forms represented in the stock group is relatively limited (Table 3), with two types of decorated bowls (Dr.29 and Dr.30) present alongside a number of plain forms, including Dr.15/17 and Dr.18 dishes, with a few examples of their larger versions. Two types of cups, Dr.24/25 and Dr.27, both appear in two sizes, although the larger module (c. 110–140 mm) dominates. There are a few examples of spouted plain form Rt.12. The forms present bear many similarities to the ones recovered from other contemporary stock groups (Table 3),Footnote 25 but also from domestic assemblages including Kingsholm, particularly the group from pits 22, 23, 25 and 26.Footnote 26 Cup forms RT8 and RT9, present at the Colchester Second Pottery Shop, One Poultry (London) and Cirencester,Footnote 27 are, however, absent from the fills in Quarry Pit 2 at Barnwood Road. The single RT9 recorded in the assemblage is from a later feature, Period 1C Enclosure 2, and is not necessarily part of the stock. Perhaps the most obvious absentees from the repertoire recovered from Barnwood Road are inkwells. Though rare, samian inkwells are regularly found on military sites in Britain, especially in the first century;Footnote 28 they are present in the group from Kingsholm and the dumped stock from Cirencester.

TABLE 3 SAMIAN FORMS FROM THE FINDS-RICH FILLS OF QUARRY PIT 2 AND FROM TWO DISCARDED SAMIAN STOCKS

(For One Poultry the data provided are from Rayner Reference Rayner2011, table 24, for Colchester Second Pottery Shop the EVEs data are taken from Monteil and Silvéréano Reference Monteil and Silvéréano2011; the MNV from Millett Reference Millett1987, 112)

Cups play a prominent role in the group from Barnwood Road, accounting for over 71 per cent of the total rim EVEs from the fills of Quarry Pit 2, with forms Dr.24/25 and Dr.27 present in almost equal quantities. Decorated bowls come in second place, with Dr.29 and Dr.30 making up more than 18 per cent of the total samian rim EVEs. The third statistically large group is made up by dishes, with Dr.15/17 and Dr.18 accounting for c. 9 per cent of the total rim EVEs.

Discussion

This is a small but very coherent group with a relatively small number of potters represented. It is particularly interesting to note that two of the potters known to have made bowls using moulds made by the T-1 group, the main style in this collection, are also represented by three stamps on plain ware. Most of the potters represented or quoted have entirely pre-Flavian careers and, found individually, the stamps and the decorated vessels would normally be assigned a date range in the Neronian period (a.d. 50–65/70). Cat. nos 5 and 32 in the Supplementary Material, linked to potters dated a.d. 60–80, suggest that this group was discarded sometime in the a.d. 60s.

The uniformity of the vessels, the coherence of the potters represented by the stamps and the decorated vessels suggest that there is no residual element in the group (i.e. old unsold vessels or those associated with domestic activities) and that all the vessels were transported and intended to go on sale together. How and why the stock ended up being discarded is harder to explain. The fragmentation index is high, suggesting that either the vessels were purposely broken before being dumped or that this is a secondary deposit of damaged stock, albeit one that retained some homogeneity.

The functional profile is not particularly ‘military’ in nature; samian assemblages from military sites in Britain are generally dominated by dish and platter forms, with decorated bowls in second place and cups in third position.Footnote 29 Here, cups dominate and inkwells are entirely absent. However, it is perhaps unwise to compare a stock group with more typical samian assemblages, unusual compositions being relatively common among discarded samian stock groups.Footnote 30

AMPHORAE By David Williams

The amphorae assemblage comprised some 230 sherds (2,228.1 kg), all belonging to two commonly found forms: the globular-shaped, thick-walled Baetican olive-oil container Dressel 20 and the thinner-walled, flat-bottomed Gauloise 4 wine amphora. The quantities for the two forms need to be put into some kind of perspective, since Dressel 20 were large, thick-walled vessels, prone to breaking into small fragments. In contrast, the Gauloise 4 were much smaller sized and thinner walled. The full catalogue of sherds can be found in the Supplementary Material, Section 2.

Dressel 20 (147 sherds, weighing 15,284 g)

This form had a long life, from the reign of Augustus till just after the mid-third century,Footnote 31 and it is difficult to closely date most ordinary bodysherds.Footnote 32 The Dressel 20 bodysherds from Barnwood Road tend to be quite ‘gritty’, suggesting an early date. Moreover, included in this Dressel 20 assemblage are a complete rim and a small number of dateable handles, including one containing a clear stamp. On typological grounds the rim and a number of the handles from Period 1A Quarry Pit 2 are all Neronian–Vespasianic in shape.Footnote 33 The amphora handle from the same feature contains a complete impressed stamp in ansa which reads M. I. M.Footnote 34 Production of Dressel 20 vessels bearing this stamp is associated with several sites along the valley of the river Guadalquivir, the most important of which was probably La Catria, just to the south of Axati, on the south bank of the river.Footnote 35 The stamp is an early one and is dated to the period c. a.d. 40–70 at Augst.Footnote 36 It is not uncommon in Britain, where it occurs at a variety of sites.Footnote 37

Gauloise 4 (83 sherds, weighing 12,812 g)

The flat-bottomed amphora Gauloise 4, which normally carried wine, was predominantly made in southern France, more particularly around the mouth of the Rhône in Languedoc, where a number of kilns are known.Footnote 38 Production of Gauloise 4 seems to have begun around a.d. 50 and during the second and third centuries it became the commonest wine amphora imported into Roman Britain. However, its arrival in Britain does not seem to have occurred until shortly after the Boudiccan revolt.Footnote 39

The above implies that the bulk of the Dressel 20 vessels may well have arrived at the site at some point between the reign of Nero and the early Flavian period, while the Gauloise 4 material must have arrived sometime after the Boudiccan revolt. If both forms arrived at the site more or less at the same time, this would suggest a time-span from the second half of the reign of Nero into the early Flavian period.

Discussion

It is instructive to compare the Barnwood Road amphora assemblage with that from the nearby Kingsholm fortress, an essentially pre-Flavian deposit.Footnote 40 The Kingsholm amphorae are represented by some 1,431 sherds (110 kg), a much larger group than is present at Barnwood Road. Moreover, where only two forms are present at Barnwood Road, there are nine identifiable types at Kingsholm: Dressel 20, Carrot, Dressel 2–4, Haltern 70, Rhodian, Dressel 8, Southern Spanish and Dressel 28, which jointly come from Baetica, Italy, Palestine and Rhodes. Dressel 20 would have contained olive oil, Dressel 2–4, Rhodian and Dressel 28 wine, Dressel 8 and Southern Spanish fish products and the Carrot and Haltern 70 types specialised goods. By comparison, the amphorae from Barnwood Road were much more restrictive in origins and produce carried, coming from Baetica and southern Gaul only and carrying olive oil and wine respectively. The presence of Gauloise 4 amphorae at Barnwood Road and their absence at Kingsholm indicate that the date of the amphorae assemblage at Kingsholm is slightly earlier than at Barnwood Road. If, as is suggested below by both McSloy and Holbrook, there was a military garrison in the vicinity of the excavated site, this may suggest that Kingsholm was earlier than it, although of course it is quite possible that earlier supplies of wine were brought to Barnwood in other forms of container, possibly barrels or even leather skins.

ROMAN COARSE POTTERY By E.R. McSloy

A Roman assemblage amounting to 1,162 sherds (9,592 g) was recorded from 37 deposits relating to 31 features or discrete layers. The bulk of the assemblage was hand-recovered, with a small proportion (85 sherds weighing 64 g) retrieved from bulk soil samples. Material described here excludes the samian ware and amphorae reported on above, although integrated totals for all Roman material are included in Table 4, and consideration is given to all material in respect of dating.

TABLE 4 SUMMARY OF ROMAN POTTERY SHOWING FEATURE TOTALS AS NUMBER OF SHERDS

(The grand total incorporates material from post-Roman phases)

The pottery was fully recorded, sorted by fabric and quantified by sherd count, weight and rim EVEs (estimated vessel equivalents). Vessel form and rim morphology were recorded where possible, together with any evidence for use and post-firing marks. Pottery fabric codings used for recording relate to the Gloucester City type seriesFootnote 41 and a concordance is provided in Table 4 matching fabrics with the National Roman Fabric Reference Collection,Footnote 42 where these apply.

Condition

The condition of the assemblage is mixed, largely a result of the burial environment and the varying characteristics of represented fabrics. There are a number of vessels reconstructable to full profile or present as large joining sherds (online fig. 3, nos 1–2, 9–11). The low mean sherd weight (8 g) is to a large extent reflective of extremely high fragmentation exhibited by some fine ware fabrics, most notably Lyon ware (TF 11H). This type, and to a lesser degree Severn Valley ware (TF 11B/TF 11D) and Kingsholm type (TF 24), were clearly affected by the burial environment, which has resulted in common and severe surface loss. With type TF 11H excepted, the mean sherd weight for the group is significantly higher at 11.3 g.

The large majority of the Roman assemblage comes from Period 1A quarry pits. The pottery and other finds from these features are strongly suggestive of military associations. The concentrations of pottery, its chronological coherence and the presence of substantially complete vessels are suggestive of deposition of material as a single ‘event’. The pottery recovered from the finds-rich fills of Quarry Pit 2 is likely to represent dumping following a period of reorganisation or abandonment.

As discussed above, the large samian group from Quarry Pit 2 has been interpreted as a discarded (unused) stock group. While poor surface survival makes interpretation impossible for a proportion of the coarse pottery, the wear to mortaria vessels and limey residues preserved on some jars from the Quarry Pit 2 dumps make it clear that some at least had been used prior to disposal.

Discussion

The clear focus of interest in this assemblage lies with material deposited within the quarry pits along the southern edge of the site. There are no indications that the activity immediately further north (including the burial plot) is significantly later.

The abundance of pre-Flavian continental wares and of specialist wares (flagons and mortaria) mark this assemblage as distinct from the majority of contemporary ‘transitional’ or early Roman assemblages from the area. The concentrations of continental types and ‘specialist wares’ are characteristics shared by pre-Flavian military-derived assemblages, including Kingsholm,Footnote 43 UskFootnote 44 and Cirencester.Footnote 45 The location of the Barnwood Road group, 2.5 km south-east of Kingsholm, is a tantalising hint that this group relates to a second and previously unknown military establishment, most likely an auxiliary fort. Although the precise circumstances can never be known, there are good indications for deposition (at least for the bulk of material from Quarry Pit 2) as a single episode. The context for this might be a period of reorganisation following the abandonment of Kingsholm and the building of the Gloucester fortress, c. a.d. 66/67.Footnote 46

Factors including the high fragmentation of the Lyon ware and a samian component made up of unused ‘stock’ mean that fully meaningful comparison with material from the (Neronian) military phases at Kingsholm Close is problematical. Nevertheless, the assemblages share characteristics of substantial reliance on continental sources (for fine wares and amphorae) with coarse wares/‘specialist wares’ supplied from local sources. Coarse wares/specialist wares in both groups are of a similar profile, largely confined to local products. Kingsholm products (TF 24) and coarse ware type TF 213 were clearly important at both sites; however, Severn Valley ware and ‘native’ types are better represented at Barnwood Road. There are differences also in (non-samian) fine ware representation; the range is greater at Kingsholm, although at both sites Lyon ware is heavily dominant. Interestingly, there are differences in the forms occurring in this fabric (TF 11H): the Kingsholm group comprising ‘tripods’ and roughcasted cups/beakersFootnote 47 and Barnwood Road material including roughcasted vessels and cups decorated with applied decoration (online fig. 3; nos 18–21). The most striking differences in the comparison of types present are with the amphorae, and the far more extensive list at the Kingsholm site. Williams (above) has seen these differences, most particularly the absence of Gaulish amphorae from Kingsholm, as chronological, with the Barnwood group being a slightly later assemblage. If this is accepted, it is tempting to see the compositional differences, such as those among the Lyon ware forms, as explicable in the same way.

POTTERY LAMPS By E.R. McSloy

Fragments from a minimum of four pottery lamps were recorded, all from Period 1A Quarry Pit 2. For all, the fabric form is indistinguishable from that of pottery type TF 12H (Lyon ware). The condition of the lamp fragments is very poor; the original reddish slip largely lost and the surfaces powdery.

The lamps are only partially reconstructable and many details are unclear. Two at least (and probably all) are volute spouted forms, either of Loeschcke Type I or IV.Footnote 48 Neither of the surviving discus designs can be closely paralleled, although the erotic and classical subjects are common to this milieu.Footnote 49 Type 1 and IV lamps are known from Britain from the second half of the first century, and Lyon ware examples can be expected to be pre-Flavian (c. a.d. 43–69).

COINS By E.R. McSloy

Two coins were recovered, both Claudian (dupondii) copies of the type in common circulation in the period c. a.d. 48–64.Footnote 50 Claudian as and dupondius copies made up the majority of the pre-Flavian coins (17 from 26) from Kingsholm Close, a site associated with Neronian military use.Footnote 51 One of the coins (cat. no. 1) is crude, weighs only 9 g, and is typical of the examples from Kingsholm Close. The other (cat. no. 2) is better executed and its weight close to official issues.

METAL OBJECTS By E.R. McSloy

The metal finds assemblage included 54 objects of iron, four of copper alloy, three of lead/lead alloy and one of silver. Iron items from Roman-dated deposits comprise mainly nails (or nail shaft fragments) and hobnails. Included is a group of 17 nails/fragments and 13 hobnails from 6243 (the fill of pit 6244). This feature was central to square Enclosure 2, and there was some suggestion from the charred plant remains that this deposit related to funerary activity. The presence of nails/hobnails is not uncommon in funerary contexts, indicating a box/casket and nailed footwear.

All of the non-ferrous metal items were recorded from Period 1A deposits. Three objects, a harness pendant, a probable pendant and a possible copper-alloy situla jar or ‘camp kettle’ (cat. nos 2–4; fig. 4) have certain or probable military associations, two of which suggest the presence of cavalry. Among these, the harness pendant (cat. no. 2) is of a form known mainly from Claudian-to-Flavian contexts, which accords with the Neronian dating (probably a.d. 60–65) suggested by the large samian assemblage from the finds-rich fill of Quarry Pit 2. The presence of one or more auxiliary cavalry units at Gloucester in the mid-first century is evidenced by finds from Kingsholm, which include a helmet cheekpiece and three pendants.Footnote 52 In addition, the well-known tombstone of Rufus Sita,Footnote 53 a Thracian trooper with a mixed cavalry/infantry cohors equitata unit, was found at Wotton Pitch, 1.5 km north-west of the Barnwood Road site.

FIG. 4. Drawings of selected silver and copper-alloy artefacts (see individual catalogue entries for full descriptions).

The lead ossuarium recovered from Period 1C Enclosure 2 (cat. no. 6; fig. 3) consisted of an undecorated cylindrical vessel with a simple folded-over lid, measuring c. 145 mm high and 168 mm in diameter, which contained cremated human remains. The use of such lead urns appears to be a mainly first- or early second-century phenomenon, with the majority known from large urban centres and military sites. PhilpottFootnote 54 noted 28 examples of ‘ossuaria’ in lead from British sites, the majority of which are plain or feature rudimentary decoration. Since Philpott's survey, more recent finds from Gloucestershire comprise a cylindrical vessel buried next to a walled cemetery in the Western Cemetery of Cirencester,Footnote 55 a lead box from a villa at Harnhill, near Cirencester,Footnote 56 and a lead container which was housed within a hollow cut into a pair of stone blocks from Well's Bridge, Barnwood, only 1 km distant from the present site.Footnote 57 That simple lead containers for this purpose occur from as early as the mid-first century is indicated by an example from Colchester associated with the centurion Facilis, dateable before a.d. 60 and probably before a.d. 50.Footnote 58

GLASS By H.E.M. Cool

The excavations produced a small but interesting group of Roman vessel glass belonging to the first century and clearly relating to both domestic and sepulchral use. A full description and catalogue of the glass is presented in the Supplementary Material, Section 8. The domestic material mainly came from the finds-rich fills of Quarry Pit 2 and included fragments of a blue/green pillar-moulded bowl (cat. nos 1–2), common on military sites from the time of the conquest to the early Flavian period, and fragments from two mould-blown vessels (cat. nos 3–4; fig. 5), regularly found on Claudio-Neronian sites. Of particular interest, two finds seem likely to be related to the funerary activity recorded on the site. A tall conical unguent bottle (cat. no. 5; fig. 5)Footnote 59 represents a development of the very common mid-first-century tubular unguent bottle and may be dated to the second half of the first century. The fragment has been deformed by heat in a manner which strongly suggests that originally it was a pyre good, though as it was found unstratified there is no certainty of this. The use of unguent bottles as pyre goods during the first century is well attested at Gloucester, as can be seen at the Wotton/London Road cemetery.Footnote 60 Another fragment (cat. no. 6; fig. 5) has also been melted and possibly came from pyre activity, but in this case it is not possible to identify the form with any certainty.

FIG. 5. Drawings of selected glass vessel fragments.

DISCUSSION By Neil Holbrook

The earliest Roman features found in the excavations respected the alignment of Ermin Street, which indicates that the course of this long distance route from south-eastern England towards a crossing of the Severn at Kingsholm had been established before Roman activity commenced here. The line of the road was likely laid out when the fortress at Kingsholm was established c. a.d. 49/50. The present site lies 2.5 km south-east of that site. The quarry pits found in the excavation were probably dug to provide the primary gravel metalling of Ermin Street. As Quarry Pit 1 was cut by Quarry Pit 2, which was partially backfilled with a substantial dump of pottery that almost certainly dates before a.d. 70, this is useful evidence that Ermin Street was constructed as a metalled road hereabouts within three decades at most of a.d. 43. Elsewhere in Britain some roads were not metalled until several decades after the initial ‘tactical route’ was established.Footnote 61 Of the other first-century remains found on the site, four broadly parallel ditches (Ditches 6, 5, 4 and 3) laid out at right angles to Ermin Street stopped short of the zone of quarry pitting adjacent to the road, which may have either been partially open features at this time or else have lain within a state-controlled road zone. Sometimes this zone was defined by a ditch which lay a little distance beyond the edge of the metalled road, but seemingly not in this case. The other possibility is that the ditch lay hard up against the edge of the road and thus lies entirely beneath modern Barnwood Road. Ditch 7 may have subsequently fulfilled this role; it cut through the infillings of the abandoned quarry pits and produced second-century pottery. However, there is no necessity for such a ditch from the outset, as excavations along the route of Ermin Street between Cirencester and Birdlip did not routinely find roadside ditches where the road traversed open country, but rather only where it passed the settlements at Birdlip Quarry and Field's Farm, Duntisbourne Abbots. At the latter the ditches were dug right up against the edge of the metalling and varied from c. 1 to 2 m in width.Footnote 62

Ditches 4 and 5 lay 11–13 m apart with a central row of post-holes between them and are best seen as defining a ditched plot with a central fence line. The concave profiles and insubstantial nature of these features precludes an interpretation as beam slots for a timber building, which in any case would have been at the upper width limit of Roman wooden structures. Some 1.0–1.5 m outside these ditches lay further Ditches 6 and 3. It is conceivable that they marked further ditched plots, with the narrow gaps providing pedestrian access to fields behind. No corresponding ditch was found further to the south-east which might have defined the other side of a plot, but given the limited areas examined in this part of the site, its existence is not precluded. Alternatively, this may represent the redefinition of a single plot by the cutting of replacement ditches on a slightly different alignment, in which case the plot could have been as much as 14 m wide if it was defined by Ditches 6 and 3.

Rectangular plots laid out at right angles to major roads are a common facet of Roman roadside settlements, both civilian ‘small towns’ and military vici associated with forts. The plots were frequently occupied by strip-buildings on the road frontage with allotments or paddocks in the backlands to the rear. Not every plot contained a structure, however, and some, especially towards the periphery of settlement, might have served a purely agricultural or horticultural function. At this site, however, the demonstrable funerary use in the succeeding phase suggests that caution should be adopted in necessarily interpreting these spaces as horticultural plots, as conceivably the area might have been designated for funerary use from the outset, with the square burial monument that contained the ossuarium a later addition. Certainly the plots with the central fence would have been very narrow strips compared with roadside plots elsewhere.Footnote 63

The relationship between these plots and rectilinear Enclosure 1, of which only the south-west and south-east sides were found, is undetermined. It is possible that the plots were laid out within the enclosure, or alternatively that Enclosure 1 is a later addition associated with the construction of the burial plot (Enclosure 2). If the plots were contemporary with Enclosure 1 this would make for an unusual arrangement, as the south-west enclosure ditch would have served to separate the plots from the road frontage. In this regard it is perhaps more likely that Enclosures 1 and 2 were contemporary and later than the plots. The ditch of Enclosure 1 cut Quarry Pit 2, although this relationship only occurred in a very small area and it is clear that the south-west side of Enclosure 1 was laid out to respect the zone of Period 1A quarry pitting. There may have been only a short interlude between the filling of the quarry pit and the laying out of Enclosure 1. One of the fills of Quarry Pit 2 contained a rich finds assemblage, but as this particular fill did not lie in the area where the quarry pit was cut by Enclosure 1, it should not be assumed that the deposition of the artefacts necessarily precedes Enclosure 1 or indeed the burial plot contained within Enclosure 2. This deposition could feasibly be contemporary with the cremation burial, or even post-date it.

The burial plot defined by Enclosure 2 measured c. 11.5 m square externally and was clearly later than the Period 1B arrangement as its ditches cut Ditch 4 and post-holes 6177 and 6267 of the central fence. Enclosure 2 was not precisely aligned with Enclosure 1, but nevertheless seems to have been deliberately set within its southern corner. In the centre of the enclosure there was a cluster of small pits or post-holes. One of these pits contained a human cremation, tentatively identified as that of a mature adult male, contained within a lead canister. Another pit had burnt residues from raw celtic beans and cereals, either sweepings from the funeral pyre or else debris from a commemoration ritual (the former interpretation is perhaps more likely given the presence of nails and hobnails in the pit). There was also a tree-throw hole in this area, but as these features occur across the site it could be somewhat later than the enclosure (the only stratigraphic relationship is that one tree-throw cut Quarry Pit 1). Numerous post-holes were found inside the burial monument, although the western part of the interior had been truncated so that the layout there cannot be considered complete. A good number of these post-holes can be reconstructed as a fence which lay 1.0–1.5 m inside the ditch. Wooden structures have been found associated with similar burials elsewhere, as at the villa settlement at Roughground Farm, Glos., where a ditched enclosure 6 m square contained an early second-century urned cremation; within the enclosure there was an irregular arrangement of post-holes, which possibly had been burnt.Footnote 64 At Holborough, Kent, a stake-built structure, 4.3 m by 4.9 m, appears to have formed a shelter used during the burial ritual above a central cremation grave; the structure was then burnt and covered by a barrow.Footnote 65 At Barnwood the upcast from the surrounding ditch might also have been mounded up to form a low square barrow above the burial and the pit containing the plant remains. The mound was perhaps retained by the wooden fence (there certainly would not have been enough space between the inner edge of the ditch and the wooden fence to have accommodated a bank).

Small cremation cemeteries, or a central cremation burial marked by wooden post-built monuments and/or ditched enclosures, have a long tradition stretching well back into the later Iron Age in the maritime regions of northern France, as well as in the Champagne-Ardenne region and eastern Picardy.Footnote 66 The tradition spread into south-eastern England in the late pre-Roman Iron Age, as an example from Westhampnett, W Sussex, testifies. There a ditched enclosure, 4.4 m square externally, surrounded a central urned cremation which lay within a four-post timber structure.Footnote 67 Cremation within ditched enclosures did not continue beyond the early Flavian period at most at Verulamium,Footnote 68 while in a rural context at Stansted LTCP site, Essex, two contiguous ditched enclosures 13 m square each contained single cremation burials, which probably date to the period c. 20 b.c.–a.d. 70.Footnote 69 The tradition must have spread from south-east England into Gloucestershire, but it was never common here and only two other examples are known to the author within the county. One is at the Roughground Farm villa mentioned above. The second is a 10 m square enclosure adjacent to Ermin Street at Field's Farm, Duntisbourne Abbots, that probably dates to the first or early second century; a centrally located pit might have held a cremation burial.Footnote 70 The presence of a lead cremation vessel marks the Barnwood burial as having some special status. Such vessels were a Roman introduction to Britain and their distribution concentrates around the major centres of Colchester, London and York.Footnote 71 At Colchester a lead container was associated with the famous tombstone of Facilis, a centurion of Legion XX, which surely pre-dates the establishment of the colonia in a.d. 49.Footnote 72 There can be little doubt that the tradition of lead cremation vessels was brought to western Britain by the Roman army, which would explain their presence at Caerleon. It is conventionally maintained that Legion XX transferred from Colchester to a fortress at Kingsholm c. a.d. 49/50. If so, and it is worth bearing in mind that it is by no means assured that the Kingsholm fortress was capable of holding a full legion (see below), it is tempting to suggest that it was the movement of that particular legion which brought the tradition of square burial monuments and lead cremation vessels to the Gloucester region. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that the Barnwood cremation burial was of a member, or veteran, of the Roman army, or their immediate family.

The burial plot defined by Enclosure 2 may therefore have been a subsequent addition to an area designated for funerary activity from the outset; perhaps other burials and/or monuments lay outside of the excavation area? One possibility is that the Period 1B ditches and fence, and the Period 1B/C Enclosure 2 were part of a garden surrounding a tomb (cepotaphion). Such gardens are best known through epigraphic and archaeological evidence from Italy.Footnote 73 They were used to embellish the setting of a burial monument, as well as potentially providing an income for its maintenance through the sale of produce and being a source of plants (such as roses) and fruit for use in commemoration rituals. Perhaps the land plots at Barnwood were occupied by orchards or market gardens; we need not necessarily envisage extensive grounds around the tomb as inscriptions show that Italian examples could sometimes occupy quite small areas. If the cremation burial was covered by a mound, and perhaps set within attractive surroundings, it would have been a visible feature for travellers along Ermin Street. Indeed, the approach to the fortress/colonia at Gloucester along Ermin Street and the branch road to the North Gate was quite monumentalised over a distance of at least a kilometre, as far as the area of grave stelae at Wotton Pitch.Footnote 74

The Period 1A finds-rich fill of Quarry Pit 2 produced a highly unusual artefact assemblage. The pottery has clear affinities with that used in the Kingsholm fortress, which was occupied c. a.d. 49/50–65/70, including Kingsholm-type flagons and mortaria, Lyon ware, Pompeian red slip ware and samian. The latter is particularly instructive as multiple examples of the same potter's die are found on identical forms with grits still adhering to the footrings, indicating that these samian vessels had never been used. The samian was heavily fragmented, suggesting that it was either both purposefully broken and deliberately dumped, or that this is a secondary deposit of damaged stock. The coarse pottery, however, presents a different picture, with wear visible on mortaria and lime-scale deposits on jars indicating that at least some of this material had been used prior to deposition. There is one potentially telling difference between the pottery from Barnwood Road and that from Kingsholm: the presence here of Gauloise 4 amphorae but their absence from Kingsholm. Williams suggests above that this indicates that the excavated groups from Kingsholm Close might date slightly earlier than the pottery found here. We might also note the absence of terra nigra at Barnwood, although less significance can be attached to that given that it is present in only very small quantities at Kingsholm.Footnote 75

How unused samian and used coarse wares came to be deposited together alongside fragments from four glass vessels (two mould-blown and two pillar-moulded bowls), and several items of military metalwork, including horse fittings and a ‘camp kettle’, is hard to explain. The military affinities of the assemblage are unmistakable. Perhaps deposition here was associated in some way with a funerary ritual which involved the deliberate placement in the ground of already fragmented material? While this might recall so-called feasting assemblages, sometimes associated with burials as at Folly Lane, Verulamium, and Holborough, Kent, the unused character of the samian, lack of charcoal in the pit fill and perhaps the absence of animal bone (although faunal remains were not well preserved on this site) argue against such an interpretation here.Footnote 76 A more utilitarian interpretation is therefore to be preferred. Conceivably this assemblage could have accumulated during clearance associated with the end of a period of military activity, hence the amalgam of bulk used material and unused samian which was deliberately broken to prevent reuse or resale. Had a larger area been examined it is possible that further groups of such material might have been found. Comparisons may be drawn with the deliberate destruction of unwanted material in the deposits found in the ditches outside the forts at Cirencester and Tiverton, Devon.Footnote 77 The roadside location might also be significant. The samian could have been stock damaged in transit along Ermin Street and disposed of in a partially filled quarry pit alongside more general refuse derived from a nearby military installation.

A burial tradition most likely introduced into western Britain by the Roman army and an unusual assemblage of military-related finds some 2.5 km from the Kingsholm fortress raise the possibility that there was a pre-Flavian military site at Barnwood contemporary with occupation at Kingsholm.Footnote 78 Where the landscapes surrounding first-century legionary fortresses can be appreciated, it is not uncommon for other military installations to exist, which can include an auxiliary fort.Footnote 79 The area around Wroxeter provides a telling example, with a vexillation fortress at Leighton 4.5 km to the south-east (and perhaps pre-dating) the legionary fortress and an auxiliary fort 0.9 km to the south of the fortress controlling a ford across the Severn, as well as temporary camps.Footnote 80 Might there have been a similar situation in the Gloucester region, with an auxiliary fort at Barnwood contemporary with the Kingsholm fortress? At Carnuntum on the Danube epigraphic evidence demonstrates that a fort outside the legionary fortress housed a cavalry regiment, while at Wroxeter WebsterFootnote 81 considered that a tombstone of a cavalryman from a part-mounted cohort of ThraciansFootnote 82 most likely indicated the garrison of the fort at the river crossing. The military garrison of Kingsholm is poorly understood. It is by no means assured that the fortress was large enough to accommodate a whole legion, and it might have been a vexillation fortress where detachments of legionaries and auxiliaries were brigaded together.Footnote 83 This suggestion arose from a desire to explain the tombstone of Rufus Sita, a trooper of the Sixth part-mounted Cohort of Thracians, which was recovered from the cemetery at Wotton Pitch, 1 km south-east of Kingsholm.Footnote 84 But Wotton Pitch is also only 1.5 km from Barnwood (fig. 1) — might the Thracians in fact have been the garrison of a fort here? While by no means conclusive, the recovery of military horse fittings from Quarry Pit 2 might lend some support to the notion of a fort containing some cavalry near here.

The location of the possible fort, and indeed the nature of Roman activity at Barnwood more generally, are worthy of discussion. The line of Ermin Street through Barnwood traverses an area of flattish lias clay with patches of gravel between two watercourses — the Wotton Brook just to the south and the Horsbere Brook c. 1 km to the north. It would seem most plausible, therefore, that if a fort existed hereabouts it would have lain to the north of Ermin Street but south of the floodplain of the Horsebere Brook, perhaps in the area now occupied by Sainsbury's supermarket and the offices of EDF Energy. Iron Age activity is also attested in Barnwood to judge from the pottery salvaged by Mrs Clifford before 1930:Footnote 85 SavilleFootnote 86 ascribes it to both the middle and late Iron Age periods, so there was possibly conquest-period settlement here. Occupation evidently continued at Barnwood after the Roman army moved westwards from Gloucester, but it is difficult to say much about its form. An evaluation close to, but on the other side of Ermin Street from the present site (128 Barnwood Road) found evidence for ditched plots laid out at right angles to the road with some suggestions of buildings (fragments of opus signinum suggest a nearby building of some status).Footnote 87 Other building traces were recorded at the next door property (126 Barnwood Road) during a watching-brief in 2003. The pottery recovered from the evaluation at 128 Barnwood Road suggests that the occupation there dates predominately to the late first to early second centuries. Subsequently the site seems to have been given over to burial, and indeed Barnwood is best known for its Roman burials thanks to the salvage recording of both cremations and inhumations by Mrs Clifford at Barnwood Cottage.Footnote 88 The most plausible interpretation of her results is that burial took place in the late first or early second century based on the cremation vessels; the inhumations might be of the same date or later.Footnote 89 Inhumation burial evidently became quite extensive to judge from records of skeletons at a number of other sites.Footnote 90 So inhumation was undoubtedly widespread in Barnwood, and the limited data from the evaluation at 128 Barnwood Road suggests that the cemeteries might have spread to cover areas formerly used for occupation (a not uncommon later Roman phenomenon at major urban centres). At the moment, therefore, we might suggest a chronological model of pre-Flavian military activity at Barnwood, which was followed by a late first-/early second-century roadside settlement laid out on either side of Ermin Street, with some burial activity (cremation and conceivably inhumation as well, if a coin of Domitian is indeed securely associated with an inhumation found at 177 Barnwood Road).Footnote 91 The use of urned cremations suggests close links between the population at Barnwood and that at the colonia at Gloucester, as this burial rite was never common in rural Gloucestershire. Some parts of the roadside settlement seemingly fell out of use by the early second century (to judge from 128 Barnwood Road) and areas were subsequently devoted to inhumation burial, although we know next to nothing of the chronology of this or the degree to which the evidence from No. 128 is representative of other parts of the settlement. The absence of later Roman activity on the present site is notable, as no other features were found in the excavation dating from before the twelfth or thirteenth century.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL: CONTENTS

For Supplementary Material for this article please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X18000272.

Note: the Supplementary Material includes online figs 1–3 and online tables 1–6.

section 1: Samian By Gwladys Monteil

section 2: Catalogue of amphorae By David Williams

section 3: Coarse Roman pottery By E.R. McSloy

section 4: Catalogue of pottery lamps By E.R. McSloy

section 5: Post-Roman pottery By E.R. McSloy

section 6: Catalogue of coins By E.R. McSloy

section 7: Catalogue of metal objects By E.R. McSloy

section 8: Glass By H.E.M. Cool

section 9: Worked stone By Ruth Shaffrey

section 10: Worked flint By Jacky Sommerville

section 11: Cremated human remains By Sharon Clough

section 12: Animal bone By Philip Armitage and Sarah Cobain

section 13: Plant macrofossils and charcoal By Sarah Cobain

section 14: Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The work was carried out at the request of Barnwood Construction Ltd. Fieldwork was undertaken by Daniel Sausins and Rebecca Riley, managed by Ian Barnes. Post-excavation analysis and reporting was managed by Martin Watts. The illustrations were prepared by Aleksandra Osinska and Lucy Martin, conservation of artefacts by Phil Parkes of Cardiff University and x-ray fluorescence analysis by Pieta Greaves of Drakon Heritage. The fieldwork was monitored by Andrew Armstrong, City Archaeologist for Gloucester City Council. The archive is currently held by Cotswold Archaeology and is intended for deposition with Gloucester Museum. We are grateful to the anonymous referees for many useful comments on an earlier version of this paper; to one of them we owe the possible interpretation of a tomb garden.