Introduction

The ageing of populations is one of the most important issues in society at present. The definition of population ageing, according to the United Nations (1956), is that the number of older people in a country or region aged 65 and above accounts for more than 7 per cent of the total population. Under this standard, China has been an ageing society since 1999. The data from China's National Bureau of Statistics (2018) shows that the population of people over 65 in China was 158.31 million by the end of 2017, accounting for 11.4 per cent of the total population. This large group of older people means that provision for the aged is a crucial issue in Chinese society.

Disease, loneliness, lack of self-care in daily life and so on are common problems faced by older people. It has been found that retirement migration or residential migration can help retired people improve their quality of life (Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Fernández-Mayoralas and Rojo1998), and in particular, that seasonal mobility can contribute to the health and physical wellbeing of seniors (Benson and O'Reilly, Reference Benson and O'Reilly2009). Retired people who migrate seasonally are called ‘snowbirds’ or ‘Grey Nomads’ (Onyx and Leonard, Reference Onyx and Leonard2005), and more and more seniors in China are observed as participating in seasonal mobility. However, seasonal mobility is still new to Chinese seniors, and the extent of their adoption of this lifestyle is unknown.

Gender plays a key role in the lives of retired people, and male and female seniors face different problems and challenges (Sobieszczyk et al., Reference Sobieszczyk, Knodel and Chayovan2003). Firstly, women are more likely to suffer from diseases in old age than men (Jagger and Matthews, Reference Jagger and Matthews2002), and moreover, they are at a disadvantage in terms of financial resources, pensions and medical insurance (Zhu, Reference Zhu2008). Secondly, due to the different work histories, social roles and life experiences of men and women, they have different challenges when adjusting to retirement (Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002). Thirdly, men's life expectancy is lower than that of women, which leads to the phenomenon of ‘feminisation of old age’, but the quality of life of older women after the loss of their spouses declines (Wang, Reference Wang2011). Overall, existing studies have looked at the gender differences of seniors in many aspects. Particularly, Simpson and Siguaw (Reference Simpson and Siguaw2013) showed that female winter migrants have more social activities and higher satisfaction levels than men. However, the impacts of gender on the wellbeing of retired people during seasonal mobility have not been explored yet.

This paper aims to examine the effects of gender on wellbeing during seasonal mobility. The study's fieldwork took place in Sanya, China. The study intends to address the following questions:

(1) What are the gender differences in the relationship between seasonal retirement mobility and the wellbeing of ‘snowbirds’ in Sanya?

(2) How do gender roles influence these gender differences in this seasonal retirement mobility–wellbeing relationship?

To answer these questions, the analytical framework of therapeutic mobility is applied (Gatrell, Reference Gatrell2013; Kou et al., Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017).

Literature review

Seasonal mobility of retired people

Retirement migration is an important form of mobility related to both tourism and permanent migration (Williams and Hall, Reference Williams and Hall2000; Wu and Xu, Reference Wu and Xu2012). The physical condition of retired people gradually deteriorates with increased age (Nikitina and Vorontsova, Reference Nikitina and Vorontsova2015), and in winter, the severe cold weather in some areas can damage the health of older people. Especially for people suffering from poor health (such as rheumatism, asthma, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, etc.), they tend to go to warmer places for the winter (Gustafson, Reference Gustafson2001), which has resulted in the development of seasonal retirement mobility for the purpose of rehabilitation.

The principal motivation of retired people to migrate seasonally is to search for a better way of life (Benson and O'Reilly, Reference Benson and O'Reilly2009), and the health benefits of warm weather are the most important pull factor (Casadodíaz et al., Reference Casadodíaz, Kaiser and Warnes2004). There is a wide connection between climate and health in people's minds (Benson and O'Reilly, Reference Benson and O'Reilly2009), and this relationship is also supported by scientific studies (Haines and Patz, Reference Haines and Patz2004; Liang et al., Reference Liang, Peng, Liang, Sun, Fan and Zhu2017). A warm and clean environment encourages retired people to spend more time on outdoor activities, which benefits their physical health and increases their social contacts (Rodríguez et al., Reference Rodríguez, Fernández-Mayoralas and Rojo1998). From a lifecycle perspective, some retirees accumulate enough savings to purchase second homes (Hall and Müller, Reference Hall and Müller2004; Montezuma and McGarrigle, Reference Montezuma and McGarrigle2018), which is also an important reason for seasonal mobility.

The seasonal mobility of retired people has been studied in different places, from Northern Europe to sun-belt areas in Southern Europe such as the Costa del Sol (Casadodíaz et al., Reference Casadodíaz, Kaiser and Warnes2004; Horn and Schweppe, Reference Horn and Schweppe2015), and from the United States of America and Canada to some Caribbean islands (William and Hall, Reference Williams and Hall2000), and reflects a variety of practices (Viallon, Reference Viallon2012). However, the phenomenon of internal seasonal retirement migration in China has only emerged in recent years.

The socio-cultural and institutional environments for seasonal retirement mobility in China are different from some developed countries (Kou et al., Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017; Wu et al., Reference Wu, Hannam and Xu2018). Firstly, family support is the most important part of support for seasonal retirees in China, and older people are encouraged to travel to tourism destinations in winter by their children, and are even financially supported by them. During their stays in the tourism destinations, older people obtain emotional support from their families through mobile phones. Secondly, tropical tourism destinations in China are normally more costly than the tourist-generating regions, but retirees from North American and European countries generally migrate seasonally to places with lower living costs. Thirdly, under the Chinese hukou household registration system, every citizen is assigned to and is registered in a particular place (Chen, Reference Chen2011), and access to medical insurance and other public welfare services is based on the place. Since most seasonal retirees’ registered residences remain in their hometowns, health care for them is restricted in travel destinations.

Wellbeing and therapeutic mobility

Mobility plays an important role in maintaining wellbeing in later life, e.g. Gustafson (Reference Gustafson2001) found that for Swedish retirees, a seasonal move to Spain was associated with health, wellbeing and activity, representing variation, freedom and independence. Mobility in physical space is ‘a mental disposition of openness and willingness to connect with the world’ (Friederike and Tim, Reference Friederike and Tim2011: 758). Seniors gain a feeling of independence and autonomy through their ability to move (Friederike and Tim, Reference Friederike and Tim2011), and for seasonal retirees in some developed countries, the practice of mobility contributes to their sense of perceived success in their new lives (Benson and O'Reilly, Reference Benson and O'Reilly2009; Benson, Reference Benson2011).

In order to explore the relationship between mobility and wellbeing, Gatrell (Reference Gatrell2013) proposed the concept of ‘therapeutic mobility’, which is derived from therapeutic landscapes. ‘Therapeutic landscapes’ refers to environments that can play a role in rehabilitation, including physical, artificial, social and perceived environments (Gesler, Reference Gesler1992, Reference Gesler1996). Similarly, the concept of therapeutic mobility emphasises the function of rejuvenation in mobility itself as well as with regard to place. Combining the ‘steps’ to wellbeing proposed by the New Economics Foundation (see www.neweconomics.org) and the ‘walking’ context, Gatrell (Reference Gatrell2013) explains the influence mobility has on wellbeing through the ‘active body’ and the ‘social body’. Kou et al. (Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017) applied this conceptual framework in the seasonal retired mobility context, and found that seasonal mobility promotes wellbeing.

The understandings of wellbeing in studies about mobility–wellbeing relationships among older people are diverse, and most are related to hedonic and eudaimonic approaches within psychology as well as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and lay-view approaches (Nordbakke and Schwanen, Reference Nordbakke and Schwanen2014). Hedonic approaches with regard to psychology focus on individual experience, such as subjective wellbeing, which refers to the overall emotional and cognitive evaluation of quality of life and consists of life satisfaction and positive and negative emotions (Diener, Reference Diener1984). The most widely known approach regarding eudaimonic traditions is psychological wellbeing, which explores the rules of human existence and life challenges (Zhang and Wu, Reference Zhang and Wu2014) and includes six core dimensions (self-acceptance, positive relationships, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life and personal growth) (Ryff, Reference Ryff1995). HRQoL approaches emphasise the importance of physical and mental health as they relate to quality of life in later years (Bowling, Reference Bowling2005; Phillips, Reference Phillips2006), while lay-view approaches are focused on one's own understanding of perceived wellbeing (Bowling and Gabriel, Reference Bowling and Gabriel2007). Nordbakke and Schwanen (Reference Nordbakke and Schwanen2014) noted that approaches that mix subjective and objective and hedonic and eudaimonic understandings of wellbeing are needed in future work.

Based on studies of the wellbeing of older people, this study examines this wellbeing from six dimensions: life satisfaction, physical wellbeing, mental wellbeing, social wellbeing, self-development and environmental mastery. Life satisfaction is one's subjective satisfaction with life overall (Diener, Reference Diener1984), and physical and mental wellbeing refer to the perceived physical and psychological health conditions of individuals (Kou et al., Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017). Social wellbeing refers to positive interpersonal relationships with others and getting enough support (Ryff, Reference Ryff1989; Kou et al., Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017), while self-development refers to one developing his or her personal characteristics and potential (Ryff, Reference Ryff1989). Lastly, environmental mastery refers to one's ability to manage their life and control complex surroundings (Stanley and Cheek, Reference Stanley and Cheek2003). This is important, considering that seasonally, mobile older people need to adjust to new environments and that the adjustment process can be a challenge for them.

Gender roles of retired people

Gender is socially constructed (Freud, Reference Freud1994; Lorber and Farrell, Reference Lorber and Farrell2003; Xu, Reference Xu2018), and each individual often has to follow the behaviours and norms defined by their gender roles. Individuals evolve gradually in the process of socialisation, and adapt to their own physiological gender (Pleck, Reference Pleck1987), reflecting the normative expectations of the social and cultural behaviours of men and women (Shaffer, Reference Shaffer2008). Gender roles have an effect throughout one's whole life, including old age.

After retirement, one's life undergoes significant changes. These changes and people's adaptation to the changes influence both the physical and mental health of older people. ‘Retirement adjustment’ refers to the adaptive changes in the psychology and behaviours of people when their social roles and life rhythms change after retirement (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Yang and Huang2003). Some scholars have implied that women are better adjusted to a life of retirement (e.g. Barnes and Parry, Reference Barnes and Parry2004; Price, Reference Price2003), since women in China are generally focused on both work and family before retirement, they have more ‘role consistency’ afterwards (Sherman and Schiffman, Reference Sherman and Schiffman1984), and therefore ageing for women in China is a more gradual process compared to men (Beeson, Reference Beeson1975).

In contrast, higher self-expectations in the work field make older men more likely to feel a sense of loss after retirement than women (Shi, Reference Shi1989). Men are supposed to participate more in work and public affairs in the traditional gender division of labour (Rose, Reference Rose1993), and after retirement, their focus of life shifts from work to family. Their core roles as breadwinners for their families abruptly decline (Griffin et al., Reference Griffin, Loh and Hesketh2013), and they may feel a loss of meaning in their daily lives.

Gender roles have impacts on the activity preferences of retired people as well, and women prefer activities with more social interactions (Jaumot-Pascual et al., Reference Jaumot-Pascual, Monteagudo, Kleiber and Cuenca2016). Studies have shown that retired women are more likely to take part in volunteer work than men because of their caring and other-oriented self-images (Rotolo and Wilson, Reference Rotolo and Wilson2007; Griffin and Hesketh, Reference Griffin and Hesketh2008; Manning, Reference Manning2010). One study about involvement in seniors’ centres showed a higher participation by women, and that activities in such social organisations increase physical and psychological wellbeing (Jaroslava, Reference Jaroslava2014). Wen and Peng (Reference Wen and Peng2010) found that older men tend to choose activities with a high degree of cognitive involvement, such as reading, while women were more involved in interpersonal activities. As for division of housework, Chatzitheochari and Arber (Reference Chatzitheochari and Arber2011) noted that British male retirees spent more time in outdoor activities, whilst female retirees continued to spend more time in household labour, and that therefore the men were more likely to have a Third Age lifestyle. However, the research by Leopold and Skopek (Reference Leopold and Skopek2015) showed that men doubled their total hours on housework after retirement, and that the gender gap in household labour shrank.

Since the gender roles of older people influence their psychological conditions, social interactions and activities, it is inferred that the relationship between therapeutic mobility and wellbeing is affected by gender. In addition, a few studies have shown gender differences in seasonal retirees regarding social activities and satisfaction levels (e.g. Simpson and Siguaw, Reference Simpson and Siguaw2013). However, current studies have not explored the impact of gender on wellbeing during seniors’ seasonal mobility. This study aims to fill this gap and enriches the theoretical connotations of therapeutic mobility.

Methods

Field area

The fieldwork for this research was done in Sanya, which is a tropical coastal city in the southern part of Hainan Province in China (Figure 1). The total land area of Sanya is about 2,000 square kilometres, and the number of permanent residents is about 650,000 (data from http://www.sanya.gov.cn/). There is abundant sunshine throughout the year, and Sanya is relatively light in industrial pollution and has extensive areas of greenery. Because of its superior geographical location, pleasant climate and good tourism infrastructure, Sanya has become the most popular destination for seasonal senior migrants in China, and in the past five years about 400,000 ‘snowbirds’ have come to Sanya each year (Wang, 2017).

Figure 1. The map of Sanya*.

*The base maps were from Google Map (http://www.google.cn/maps/place/Sanya).

Data collection

The research team has been working in this place for the past ten years, mainly with retired tourists, and therefore knows this place well. This familiarity with the place has enabled the researchers to develop appropriate strategies for the research design for this study. The first-hand data for this study were collected in the areas of Dadonghai and Sanya Bay in Sanya in January and February 2018.

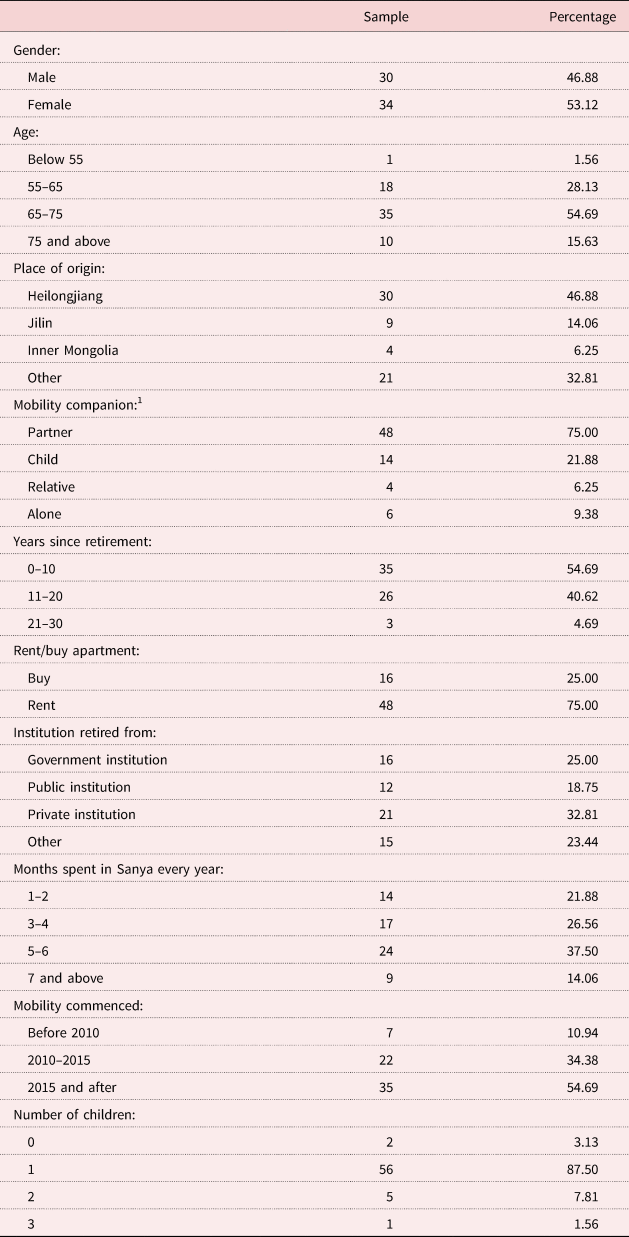

Semi-structured interviews were used to collect qualitative data, and a total of 64 ‘snowbirds’ were interviewed, comprising 34 females and 30 males. In order to compare the gender differences and exclude the impacts of economic conditions, regional culture and other factors, the interviewees included 11 couples. The basic information for the interviewees is shown in Table 1, from which it can be seen that the majority of the ‘snowbirds’ were accompanied by their partners, and some even with their children, with only six being single. Eighty-three per cent of the ‘snowbirds’ were between 55 and 75, with most living in rented apartments. The interviews included information about the daily activities and social contacts of the ‘snowbirds’, and how they obtained wellbeing during their mobility.

Table 1. Basic information of the interviewees

Note: 1. The total percentage is more than 100 because one person may have more than one mobility companion.

Non-participatory observation was also used to obtain information about the daily activities of the ‘snowbirds’. The specific observation sites included Bailu Park, Gangmen Village, Haiyue Square, Dadonghai Square and other places where the ‘snowbirds’ gathered. Also, while conducting the interviews, we observed the daily activities of four couples in their homes. The observation content mainly included the types of activity and the movements, dialogues, expressions and emotions during the activities. These observations were recorded, and in order to gain insights into the lives of some of the seasonal senior migrants, the researchers established long-term contact with four of the ‘snowbirds’.

The research team used GPS devices to record the movements of the ‘snowbirds’, and applied the method of mobile ethnography to collect data. Mobile ethnography is a research method that can help researchers to know the immediate reactions and feelings of respondents at the time of an experience, rather than interviewing them afterwards for them to recall their experiences (Muskat et al., Reference Muskat, Muskat, Zehrer and Johns2013). When recording, the GPS devices were with the respondents all day, recording the location information every ten seconds. With the permission of the respondents, the researcher followed them on the recording days to observe their actions, emotions, language, etc., keeping specific activity logs and interviewing them during their movements. After the collection was completed, the GPS track data were imported into ArcGIS online in order to generate visual data.

Data analysis

Before the analysis, the second author sorted out the first-hand data obtained from the interviews and observations, and then numbered the 64 interviewees according to their research order. Next, the recorded interviews were converted into text form. Overall, 70,000 words of recorded material and observational notes were obtained. In addition, the GPS tracking data and activity logs were used as supplements in order to understand the activities of the ‘snowbirds’ in depth.

Theoretical thematic analysis was used to identify and analyse the qualitative data (Lin et al., Reference Lin, Julve, Xu and Cui2018), and the authors followed the guidelines of Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2008) to analyse the data. The second author was the main analyst, with the assistance of the first author. Firstly, through repeated readings of the interview transcripts and observational notes, the authors became familiar with the data. Secondly, content related to the research question was screened, and some words that had the same or special meanings were grouped in order to form analysis units. Thirdly, the authors searched for broader concepts and then divided the initial codes into potential themes. Fourthly, the data were searched in order to support or refute the proposed theory, i.e. the theory of therapeutic mobility. Lastly, after being refined and modified, themes were defined and named. The final compilation of these materials helped in the analysis of the seasonal senior migrants’ lives and wellbeing in Sanya from the perspective of gender.

Results

Daily activities, physical wellbeing and mental wellbeing

Daily activities are important for the physical and mental wellbeing of senior seasonal migrants. The gendered landscape of daily activities is obvious, and is reflected in both outdoor and indoor activities. Although the majority of the seniors came to Sanya as couples, and they often came and went back home together, their outdoor activities were generally different and were spatially separate.

The most conspicuous activities were those of the groups of dancers occupying the large open spaces, of which the main participants were women. Apart from dancing, group activities in the square also included tai chi, choral groups and so on. These activities were performed both by older men and women. Some people played with diabolos or went rollerblading on the square, and most of these were men. As well, on stone benches in the shade of trees, some male seniors played chess or cards. On the edge of the square, some older men exercised on fitness equipment, while some just stood by and did not participate in any activities (observational notes G1, 2 February 2018, Bailu Park; observational notes G02, 5 February 2018, Haiyue Plaza). In general, however, the participants in large-scale group exercises were mainly women, and the participants in individual exercise or intellectual hobbies were mostly men.

The observations were also supported by the interviewees. One couple stated that their daily activities were different:

I take a walk at the Bailu Park in the morning and do physical exercises in the afternoon. After dinner, we turn around together in the park. My wife's daily activities are more abundant. She dances every afternoon and plays badminton on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Sometimes she plays cards with a group of old ladies, so she knows many local friends. (M30, male, 69 years old)

In this example, the female ‘snowbird’ was more socially active than her male counterpart; the female participated in group activities more, while the male participated more in individual activities.

Outdoor activities benefit the physical wellbeing of ‘snowbirds’. In north-east China, the home area of most ‘snowbirds’, people rarely go out during winter because of the cold weather:

In my hometown, it is cold outside, and it is hot inside. Being cold for a while and hot for a while is bad for the body. The climate here is suitable and comfortable. Those who have cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases come here. If you cough, asthma, it's good to be here. (W43, female, 63 years old)

Compared to the cold weather in their hometowns, the warm climate and fresh air in Sanya is more comfortable, and therefore the seniors spend more time outdoors. Furthermore, ‘snowbirds’ perceive their role as ‘consumers’ in a tourism destination, and so they are more willing to enjoy the sunshine and air outdoors, through which their physical wellbeing is improved.

Among the ‘snowbirds’ in Sanya, regarding the division of domestic work, most female ‘snowbirds’ were still responsible for housework, similar to the traditional division of labour by gender. Ms ZhaoFootnote 1 (W56, female, 76 years old) was from Inner Mongolia and had been a policewoman. After retirement, she came to Sanya together with her husband, Mr Qian, every year in October, and then returned to her hometown in March the next year. They bought a house in Sanya in 2016. Her daughter, son-in-law and grandson also came to Sanya on their winter vacations. Doing housework and exercising were the most basic daily activities for Ms Zhao, and her life was rhythmic and fulfilling. As Ms Zhao stated:

The usual activities are dancing, accompanying grandchildren and making three meals a day. In the morning, I make some milk tea, stir-fried rice and cheese. At noon, I go to the vegetable market to buy some ingredients and cook some garnish with rice. After lunch, I have a break. In the afternoon, I go to the tennis hall to play tennis and do some stretching exercise, and then go home at four o'clock. We eat some porridge or noodles at night. Then at 6 o'clock in the evening, there are some people dancing in the square, and I like to join them. When you are old, you have to move. (W56, female, 76 years old)

Different from Ms Zhao, her husband, Mr Qian, had much simpler daily activities. Mr Qian was 77 years old, and before retirement he had been a civil servant. According to the observations, Mr Qian went out twice a day. In the morning, he took walks in the park, played chess or watched others playing chess, and in the evening, he went to the square with Ms Zhao and watched her dance. When they were at home, Ms Zhao did the cooking and laundry, and Mr Qian sometimes helped mop the floor or buy food (observational notes G05, 3 February 2018, Huixin Village).

The differences in indoor activities are related to gender roles. Under the influence of traditional gender roles, housework is mainly undertaken by women. However, this unequal division of labour becomes an advantage for women after retirement, as women control the family space. Female ‘snowbirds’ gain a sense of fulfilment from housework and thus maintain a psychological balance after retirement, while in contrast, male seniors must change from a busy schedule to a state of idleness after retirement. The seasonal mobility leads to a further shrinking of the men's active spaces, so they are more likely to feel lonely and helpless, which has a negative impact on mental wellbeing.

Sociality, social wellbeing and self-development

Socialising is a way to establish new friendships, which plays an important role in maintaining social wellbeing and the self-development of senior seasonal migrants. Four types of social interaction were observed, of which the most important was companionship. Seasonal senior migrants who live together play a critical role in each other's lives, and they are the main providers of social support for each other. Among the 64 interviewees, 75 per cent lived in Sanya with their spouses. Seniors who lived in Sanya together with their spouses generally showed high levels of social wellbeing and life satisfaction. Female ‘snowbirds’ expressed the key role of their companions, especially their husbands, in their social and mental wellbeing in Sanya, e.g. ‘I won't miss home when staying with my husband’ (W35, female, 68 years old).

In contrast, widowed ‘snowbirds’ were less likely to make contact with others. They may have been forced to live alone in Sanya because of physical illnesses, and they faced greater challenges. For example, Ms Sun suffered from a cerebral infarction and her husband had died several years previously, so she came to Sanya alone, living in a rented house. In the interview, she repeatedly stressed that there were very few people she knew in Sanya:

I've only been here for a month, and I don't know anyone. I've talked to neighbours, but not familiar. My children were supposed to come here for the Spring Festival, but my grandson has a cold, he is still too young to go … I don't know many people here … It is certain that life is not convenient, and the most fearful thing is to suddenly fall ill and no one will find out. (W09, female, 66 years old)

In the familiar social networks in their hometowns, widowed female ‘snowbirds’ depended on their friends and relatives; however, after coming to Sanya, it was difficult for them to build a sense of trust and respect, and so they tended to avoid in-depth communication.

Friends with the same hobbies are also important to the social wellbeing of ‘snowbirds’, and they engage every day in their hobbies, such as singing, tai chi, calligraphy, etc., forming a close-knit circle of friends. Spontaneity and regularity are the important features of these social circles. Women are more likely to make lifelong friends with people with common hobbies. As one female ‘snowbird’ said, ‘The people we dance with sometimes get together, find a small restaurant and have a dinner together’ (W52, female, 69 years old), while another said, ‘For example, people who likes playing Hulusi Footnote 2 often get together at the beach, picnic and travel’ (W38, female, 70 years old). These social activities give them opportunities to chat, play together and accompany each other, thus reducing loneliness and helping their mental wellbeing. However, the interviews with the male ‘snowbirds’ were less likely to result in similar conclusions. In short, the men were more concerned with the activity itself, and the women were more concerned with companionship.

Local organisations and clubs that are set up and managed by seniors themselves are one way to establish new relationships. Participating in these organisations can give some seniors the feelings of re-employment and self-development. One participant, Mr Li, was 81 years old and had been a college teacher before he retired. Since 2010, he had gone to Sanya with his wife, Mrs Zhou, for about eight months every year. In the first few years, Mr Li actively organised the Spring Festival Gala in the community to enrich the cultural life of the ‘snowbirds’, and after the establishment of the Sanya Retirement Pension Association (a voluntary organisation providing service and help for ‘snowbirds’) in 2013, Mr Li volunteered to work in the association, and handled its daily affairs eight hours a day. As he stated, ‘My idea is that only being valuable to society do I feel happy’ (M02, male, 81 years old). Volunteer work made Mr Li feel that life was full of value. His wife, Mrs Zhou, was also an organiser of the Sanya Retirement Pension Association, but different from her husband, Mrs Zhou spent more time in household labour and interactions with neighbours rather than in working for the association (observational notes G05, 3 February 2018, Huixin Village). The work of social organisations is an important part of public life. Affected by traditional gender roles, men are more active in political pursuits, and being a founder of an organisation is a way of self-development for some people. Thus, they obtain a sense of fulfilment and achievement.

Meeting strangers often occurs in public places such as parks, and is generally random and short term. According to the observations in parks and squares, men communicate more with strangers than women (observational notes G1, 2 February 2018, Bailu Park), and although they may not know each other, they can sit and chat together, e.g. ‘People from different places brag and chat with each other in the park’ (M45, male, 65 years old). These short social interactions are difficult to develop into long-term, stable social relationships. As one male ‘snowbird’ noted:

No one knows anyone, I feel the same. Meet and say hello. Chat and take our own pleasure. And say goodbye at the end. No long-term and deep contact. It's a way to kill time. (M17, male, 67 years old)

For retired people, strong ties are more important than weak ones (Liu and Ji, Reference Liu and Ji2013). Family members (especially spouses and children) are the core providers of social support, followed by friends and neighbours, and, finally, formal support systems such as government (Cantor and Little, Reference Cantor and Little1985; Kabir et al., Reference Kabir, Szebehely and Tishelman2002). When seasonal retirees stay in Sanya, they often miss home and feel lonely, and therefore, their social wellbeing overall is negatively impacted. However, it seems that older males and females develop different strategies to cope with their social activities. Women still rely on their husbands in Sanya or on family members back home through mobile phones. Even when they develop new friends in Sanya, they tend to search for those from the same hometowns or with common hobbies so that they can maintain long-term relationships, while men are interested in participating in local organisations and communicating with strangers.

Gender roles affect how female and male older people make social connections. Women are expected to take on more family responsibilities such as parenting and maintaining family relationships, so women communicate more with family and friends. When they are in other places, they still rely on their family members, and because of the availability of mobile phones, it is easy for them to keep these connections. In addition, their household chores may be reduced in tourism destinations and they have more opportunities to be social, so their social wellbeing may not be much reduced.

However, men are expected to participate more in public affairs, but after retirement, their opportunities to make social interactions through public affairs are reduced. Further, only a small number of them have an opportunity to participate in public affairs, and so most male ‘snowbirds’ are idle. Although they can talk to strangers in a casual way, it is difficult to develop any deep relationships. Therefore, retired men have difficulties in maintaining their social wellbeing.

Context, life satisfaction and environment mastery

The context of therapeutic mobility refers to individuals’ motility, access to the environment and interactions with their surrounding contexts during the process of mobility (Kou et al., Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017). In large-scale seasonal mobility, ‘contexts’ refers to the natural, economic, social, cultural and other environments in Sanya, while in small-scale daily mobility, ‘context’ refers to a specific activity's environment, including streets, parks, squares and other spaces. Context mainly plays a role in the life satisfaction and environmental mastery of ‘snowbirds’.

Sanya is a tourist destination, and a large number of tourists and seasonal senior migrants flood into Sanya every winter, causing high prices, noisy environments, traffic jams and many other problems. Many ‘snowbirds’, both men and women, expressed that they were deeply troubled by these things. A female ‘snowbird’ said:

There is a morning market in the place where I live, and it starts at 5 o'clock. There are huge crowds of people. I just can't get a rest. At 7 o'clock, they start to sing and dance until 8 o'clock in the evening. It is very noisy and I feel a little annoyed. (W39, female, 75 years old)

Cost of living was the topic most mentioned by the ‘snowbirds’ in the interviews, as the prices of housing and daily necessities were high. Retirees complained:

Things are expensive and hard to buy. (W60, female, 63 years old)

There are more and more people coming to Sanya, resulting in higher prices. The peppers sold in the first market cost 20 yuan a kilogram now, which is higher than the price in first-tier cities. When it's Spring Festival, it's more than 20 yuan. (M41, male, 70 years old)

In addition, cultural differences between northern and southern China can make for difficulties between the ‘snowbirds’ and the local people, as they may be unable to understand some of each other's behavioural habits, and so the ‘snowbirds’ often try to avoid contact with the local people. During the interviews, some ‘snowbirds’ referred to the locals as ‘unfriendly’. Therefore, when choosing a place of residence, they will tend to choose a community of fellow outsiders and keep a distance from the local community. Overall, the assessments of the social and cultural environments of Sanya by the ‘snowbirds’ were mostly negative, and their life satisfaction was reduced. Regarding this point, the gender differences were not significant.

On the other hand, both male and female seniors had very high satisfaction with the natural environment, for example:

The weather is good, the water is good, and the sunshine is good. The living conditions are very important. We can't survive without air even seconds. Sanya is an ideal place for the older people. (M02, male, 81 years old)

This reflects that the climatic conditions of Sanya have brought improvements in physical health. An older woman who had stayed with her husband in Sanya said:

I think the happiness index is improving. The range of activities broadens when the physical quality getting better. We can walk from Xifeng Bridge to Yuya Road. (W31, female, 58 years old)

From her description, improvements in health enable them to do more physical activities.

Gender influences the wellbeing of ‘snowbirds’ in the aspect of environmental mastery as well. On the one hand, female seniors generally do not choose to go out at night unless accompanied by someone, as women have been educated that they are vulnerable in public spaces (Valentine, Reference Valentine1989), and so the times and spaces for their activities are limited. As shown in Figures 2 and 3, the scope of women's activities is mainly concentrated in parks and squares, and is shorter time-wise than that of men. On the other hand, collective activities usually occupy the central position in outdoor spaces, and the main participants in such activities are women, which reflects the advancement of women and changes of gender roles to a certain extent.

Figure 2. Daily Activity path map of a female “snowbirds”.

Figure 3. Daily Activity path map of a male “snowbirds”.

Gender and intersectionality on mobility and wellbeing

This study also finds that gender is not the only influencing factor. Economic status, health conditions and family support all affect the wellbeing of ‘snowbirds’ in Sanya. Financial status is an important factor that retirees must consider when making decisions to travel (Benson, Reference Benson2010). Kou et al. (Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017) have pointed out that most Western seasonal senior migrants are middle class, while not all the ‘snowbirds’ who come to Sanya every winter have good economic conditions, and quite a number of people take seasonal mobility decisions due to physical illnesses.

The experiences of ‘snowbirds’ with different economic statuses reflect huge differences. Rich retirees can have a second house in their resettlement area, providing a feeling of ‘home’, while ‘snowbirds’ with average economic conditions must rent, and some of them have very poor living conditions. As one female ‘snowbird’ from Beijing stated:

If you have the economic condition to buy a small house here it is very good, because the house gives you the feeling of home. You won't have this feeling if you live in a rented house or hotel. In your own house, you can eat what you want, do what you want. This is your second home. (W39, female, 75 years old)

Another interviewee said, ‘Many retirees can't bear the price of housing, and live in cheap and uncomfortable rented houses’ (W06, female, 65 years old).

High prices for daily necessities were something that many retirees complained about during the interviews as significantly influencing their wellbeing, and some ‘snowbirds’ said that they would not come to Sanya the next winter because they could not afford the costs. Three interviewees mentioned that they had had to find odd jobs to support their daily expenditures in Sanya. Mr Wu and his wife came to Sanya because of the wife's poor health, and in order to support them, he got a job giving out leaflets. Both of them used to be factory workers, and their combined pensions came to 4,400 RMB a month, but they had spent 150,000 RMB to treat Mr Wu's wife's cancer. Mr Wu said:

My wife is in poor health. She feels uncomfortable at home but better here. I hand out leaflets to supplement family income. The wages are low, 50 or 60 RMB a day. (M50, male, 63 years old)

Being old and unskilled, he could only find low-paying jobs, and compared with those with good economic conditions, their life in Sanya was harder.

There are differences in the wellbeing of senior seasonal migrants of different ages as well, which is mainly reflected in the influence of health conditions on wellbeing. Older people have a higher possibility of suffering from disease, but health care throughout their seasonal movements is lacking (Kou et al., Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017). Also, they are more likely to have difficulty with physical mobility. An 80-year-old female ‘snowbird’ said that her activities were limited, i.e. ‘I'm not going anywhere else’ (W11, female, 80 years old). These people's daily activities are limited, which means that their capability to access the environment and interact with their surroundings is limited as well.

Family support is also an important factor affecting the wellbeing of ‘snowbirds’. In China, social support systems for older people are still inadequate, and so their families are their most important source of support. Therefore, the wellbeing of ‘snowbirds’ who are accompanied by their spouses or children is generally higher. Just like the example of Ms Sun, some older people are forced to come to Sanya every year for their health, far from their original social networks, and if emergencies occur, they still tend to contact their relatives or friends back home. Seasonal mobility brings them improvements in health, but at an increased risk of loneliness.

Discussion: the impacts of gender on mobility and wellbeing

As shown above, gender differences exist in the relationships between the seasonal retirement mobility of ‘snowbirds’ and their wellbeing. Female ‘snowbirds’ tend to have a more positive attitude towards changes in their environment, e.g. they take part in more group activities outdoors, and do housework indoors. Through their group activities they find social wellbeing, and through housework they gain a feeling of enrichment. This enrichment helps them maintain a balanced mental state, in contrast to their multiple stresses and workloads before retirement. In contrast, the attitudes of male ‘snowbirds’ are somewhat negative. They prefer to be bystanders rather than participants in collective exercise activities, and rarely do housework at home. Only a few men participate in the management of social organisations and gain a sense of accomplishment. As a result, female ‘snowbirds’ are more likely to benefit from seasonal mobility after retirement.

The gender differences regarding the choices of activities by ‘snowbirds’ were affected by the social expectations of their gender roles. Women undertook housework, maintained good relationships with neighbours and friends, and took a more active part in group activities such as dancing, all of which were in line with their gender roles. However, men chose to exercise alone, participate in public affairs and play chess. These are all things that Chinese gender roles expect of men. People tend to make their behaviours cater to their gender roles, but sometimes this tendency can become a barrier to their wellbeing. For example, some male ‘snowbirds’ may also want to participate in activities such as dancing, but they think it does not conform to the male image and feel that it is ‘inappropriate’.

In addition to the gender differences in the activities, sociality and interactions of ‘snowbirds’, gender also works as a moderator between mobility and wellbeing. There are different sources of wellbeing for men and women. Male ‘snowbirds’ tend to get higher satisfaction from physical exercise or intellectual hobbies, while females gain improvements in wellbeing through group activities and social interactions. In other words, men care more about what they are doing, while women care more about who they are with.

It is also found that these differences were not static, but complex and dynamic. For example, some male ‘snowbirds’ helped with housework in Sanya. Also, some widows gained wider social interactions through participating in group activities and establishing new friendships to make up for their lack of family companionship. The different characteristics and attitudes towards the lives of males and females therefore influence the relationships and wellbeing of seasonal retirement migrants.

The special context of China provides a background to understanding these differences. Firstly, many Chinese women are able to control their family incomes and their statuses in their families are relatively high. After retirement, women are more dominant in the family space, showing higher life satisfaction and more positive emotions. Secondly, family is the most important support resource for older people. Therefore, seasonal senior migrants who lived alone in Sanya had much harder lives than those who did not. Lastly, as Rose (Reference Rose1993) pointed out in a study on gender issues, attention should be paid to the multiple roles of gender and other factors. The issue of gender is not an isolated difference between men and women, but involves integrated social, political, economic and cultural issues.

Conclusions

This paper finds that the wellbeing of older people is strengthened through seasonal retirement mobility but gender has impacts on that relationship. Gender not only influences their daily activities, sociality and environmental interaction, and therefore affects their wellbeing, but also moderates the relationship between mobility and wellbeing.

Many of the differences result from the formative influence of gender roles. Women, especially those who are accompanied by their husbands, get more benefits from seasonal retirement mobility. Firstly, the lives of female ‘snowbirds’ in Sanya are more fulfilling and positive if they are accompanied by their husbands. Compared with their hometowns, female seasonal senior migrants are more willing to explore outdoor spaces and spend more time on recreation in Sanya, where the infrastructure and natural environment encourage public activities. Secondly, housework is still mainly undertaken by women in Sanya, which is a continuation of their lives in their hometowns before retiring. Doing housework makes the lives of women more substantial and meaningful in Sanya, while men often have nothing to do. Thirdly, the social circles of female ‘snowbirds’ are dominated by strong ties, while male ‘snowbirds’ have weaker ties. Being with their husbands or friends in Sanya can meet the needs of women, while men often feel a lack of wider social interactions.

This study enriches the therapeutic mobility framework and applies this framework to seasonal retired mobility in order to explore gender differences. It also provides insights into the topic of seasonal retirement migration. People's lives change after retirement, and some people migrate seasonally in order to improve their quality of life. Kou et al. (Reference Kou, Xu and Hannam2017) noted the influences of health conditions and willingness for mobility on the relationships between seasonal retirement mobility and wellbeing, based on which this paper points out that gender differences exist in those relationships and shows how gender roles influence the differences. This paper also observes that ‘snowbirds’ are not a homogenous group, and thus the impact of seasonal mobility on their wellbeing cannot be generalised. Gender, age, economic conditions, health status, family support and other factors will affect the experiences of ‘snowbirds’ in a destination.

This research contributes to studies on gender and retirement. Discussions on the wellbeing of males and females at older ages have been going on since the 1960s (e.g. Cumming and Henry, Reference Cumming and Henry1962), and two opposing views are shown in contemporary studies (Wong and Shobo, Reference Wong and Shobo2017). Some believe that greater social inequality is experienced by women in their later years (e.g. Kim and Moen, Reference Kim and Moen2002), while others, by contrast, argue that women are better adjusted to retirement than men because of smoother role transitions (e.g. Barnes and Parry, Reference Barnes and Parry2004).

This study adds a nuanced dimension to studies regarding the ‘privilege’ of leisure for men in contrast to the ‘burden’ of household chores for women after retirement (Calasanti, Reference Calasanti1996; Chatzitheochari and Arber, Reference Chatzitheochari and Arber2011). It finds that for female seasonal retirees, doing housework might be a way to gain a feeling of fulfilment and control over the family space. Although this study was carried out in the Chinese context, the findings can be applicable in other social contexts, particularly in East Asian countries, where men are occupied with and dedicated to work before they are retired while women are more connected with family. Therefore, the adjustment to retirement of these working men may be difficult, even when they migrate to other places. In contrast, female seasonal senior migrants have more fulfilling daily activities and are more willing to establish new friendships, and as a result, they are more likely to adapt better to changes in their environment and generally maintain a higher sense of wellbeing than men. This lends support to the studies reflecting the better adjustment of women after retirement.

There are also practical implications. Firstly, support for older people in China mainly comes from family, and since some ‘snowbirds’ come to Sanya by themselves, they may have to live alone, with insufficient family and social support, and the lives of lonely older female ‘snowbirds’ are even harder. Therefore, social supports in the retirement destination are important, and community-based structures such as legal aid, health care, education, psychological counselling, and social and recreational activities should be provided, regardless of the person's hukou placement.

Secondly, and related to the previous observation, older people, especially men, often do not adjust well to life after retirement, resulting in depression and other psychological problems. The problems are even more serious when they are in a retirement destination and face an unfamiliar environment. Therefore, the mental health and subjective wellbeing of older people after retirement should be better addressed. Last but not least, the management of seasonal migration destinations such as Sanya faces great challenges. The seasonal influx of people makes the city overcrowded, and the infrastructure is strained in the winter. Resources are limited, but there is high demand, and the high prices can exclude locals and less-wealthy people from elsewhere from benefiting from Sanya's healthy environment, and so policies with regard to population access and resource allocation are needed. In addition, better spatial planning is needed in order to provide more public spaces and infrastructure, thereby increasing accessibility for people who are less wealthy.

Financial support

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 41771145, ‘Therapeutic Mobilities and Health Tourists’ Spatiotemporal Behaviours, Experiences and Mechanisms’).

Ethical standards

The study followed the required procedures of research conducts of Sun Yat-sen University.