George Gershwin composed for the Broadway stage for two decades. Two songs – single numbers in shows featuring several songwriters – bookend this area of Gershwin’s output: “Making of a Girl” in the Passing Show of 1916 and “By Strauss” in the 1936 revue The Show Is On (both productions played the Winter Garden Theatre). In the intervening years, Gershwin was the sole credited composer on twenty-two musical shows, and songs by Gershwin were included in nineteen more productions. From 1924 to 1932, Gershwin was a dominant commercial and artistic force on the New York musical stage.

Gershwin was six years old in 1904 when Longacre Square – where Broadway crosses 7th Avenue – was re-named Times Square. The opening of the subway that same year spurred the rapid development of an entertainment district around the system’s 42nd Street and Broadway hub. During his early career as a song plugger on Tin Pan Alley – a cluster of popular song publishers on and around West 28th Street – Gershwin witnessed the explosive growth in theater construction just a few blocks to the north in the midtown rectangle loosely bounded by 6th and 8th Avenues and 41st and 54th Streets. He eagerly joined the ranks of Broadway songwriters as soon as he could, aspiring to compose, he remembered in 1931, “production music – the kind Jerome Kern was writing.”1 In 1919, at the age of twenty-one, Gershwin’s first full score for a Broadway show, La-La-Lucille!, played a modest 104-performance run at Henry Miller’s Theatre (today replaced by the Stephen Sondheim). As his career writing for the popular stage took off in the mid-1920s, Gershwin was at the center of Broadway’s heyday as an engine of American popular music (just before the emergence of mass media musical formats like network radio and sound film). His final shows faced the harsh effects of the 1929 Stock Market Crash (after which Broadway production activity plummeted).

Gershwin contributed to the full range of musical theater genres on offer between the two world wars. He composed entire scores for revues, musical comedies, and operettas – the three principal types of musical shows. Gershwin’s 1935 “folk opera” Porgy and Bess (124 performances) – a musical theater work outside Broadway norms for the time (although it opened in a commercial engagement at the Alvin Theatre) – sits squarely in the interwar genre of the black-cast show, the fourth sort of musical typical of the time. (For more on Porgy and Bess, see chapters 9 and 10, this volume.) No other Broadway songwriter or composer impacted every kind of Broadway musical show like Gershwin did.

Gershwin’s career began with songs interpolated into shows featuring multiple songwriters – a common practice for emerging talents. One of these songs, “Swanee,” scored as Gershwin’s first commercial hit after Broadway star Al Jolson added it to his specialty act in the Capitol Revue (1919). From 1920 to 1924, Gershwin had a recurring job composing songs for George White’s Scandals, an annual summer season revue that emphasized up-to-date song and dance. Isaac Goldberg, Gershwin’s earliest biographer and a helpful period guide to Broadway in the 1920s, noted in 1931 that the Scandals provided the young composer with “firmly-entrenched recognition on Broadway.”2 After some early opportunities to compose complete scores for book shows – Primrose (1924) for London’s West End; Sweet Little Devil (1924, 120 performances) for Broadway, in addition to La-La-Lucille! – Gershwin hit his stride as a theater composer with Lady, Be Good! (1924, 330 performances), a defining musical comedy of the decade. Gershwin wrote eight more musical comedies in the next five years, most all in the mold of Lady, Be Good! – set in the present, in fashionable East Coast locales, peopled with vibrant young characters who find love by way of farcical, lightly romantic plots. Gershwin’s older brother Ira, who became his principal songwriting partner with Lady, Be Good!, was the sole lyricist on all of these but Sweet Little Devil, whose lyricist was B.G. DeSylva. Any survey of George’s Broadway must include the equal contribution of Ira: this chapter is about both.

In 1925, Gershwin shared composing duties with composer Herbert Stothart on an uncharacteristic project, a romantic operetta about the Russian revolution set in Moscow and Paris titled Song of the Flame (219 performances; Stothart and Oscar Hammerstein II wrote the lyrics). But further operettas in this grand style were not in Gershwin’s future. Instead, the Gershwin brothers teamed up with bookwriters George S. Kaufmann and Morrie Ryskind to create three satirical, political operettas in the British tradition of Gilbert and Sullivan: Strike Up the Band (1930, 191 performances; a 1927 version closed during out-of-town tryouts before reaching Broadway); Of Thee I Sing (1932, 441 performances, winner of the Pulitzer Prize for drama); and Let ’em Eat Cake (1933, 90 performances, a commercially unsuccessful sequel to Of Thee I Sing). Gershwin’s final Broadway musical – the 1933 flop Pardon My English (46 performances) – has the sardonic edge of musical comedy, but its setting in Germany and several waltzes suggest Broadway operetta. Ira’s lyrics consistently reference or mock operetta yet select numbers, such as the love duet “Tonight,” would not be out of place in a work that takes itself more seriously. Tensions between “German” and American music, understood to be jazz, play out as well: with the operetta-singing ingénue prevailing romantically over her torch- and blues-singing rival. Porgy and Bess followed, after which the Gershwins moved to Hollywood where George died unexpectedly in 1937 after writing songs for two film musicals made by RKO and starring Fred Astaire (Shall We Dance and A Damsel in Distress, both 1937).

For virtually the entire span of his professional and creative life – even as he carved out a place in the concert hall with works like Rhapsody in Blue (1924) and An American in Paris (1928) – Gershwin was invested in the collaborative process of making Broadway musicals, a creative sphere with specific challenges within which he was an important commercial and artistic force. This chapter considers Gershwin’s work as a composer of scores and songs for the Broadway stage from two complementary angles: form and content. First: form. Successful Broadway shows in Gershwin’s time sought to reconcile a formal tension between the whole and the parts: shows succeeded as wholes (an evening’s or afternoon’s entertainment in a New York theater) but were composed of somewhat autonomous constituent parts (individual songs and performers). It was Gershwin’s job, working with a varied group of musical theater professionals, to balance these two imperatives in the musical realm (the primary focus in this consideration of musical theater, a multifaceted art of which music is only a part). Second: content. Gershwin’s Broadway songs and scores, like his concert music, were understood to be marked by the sounds of popular syncopated music of the 1920s – at the time called jazz. The content of his shows included many audible and textual links to this music, which was understood to be derived from African American sources but was swiftly being claimed by white Americans. Gershwin’s musical comedies did important and subtle cultural work moving jazz into mainstream white mass culture. But before exploring larger questions of form and content, the very accessibility of Gershwin’s Broadway shows from the perspective of the present bears consideration.

Gershwin’s musicals were built for the moment with no thought for posterity. Specific performers – and those performers’ connection with the New York audience – were essential to their effect. In historical terms, this has meant that none of Gershwin’s musicals enjoyed enduring afterlives. Only twice have commercial producers attempted to bring a Gershwin musical back to Broadway: a revived Of Thee I Sing lasted just 72 performances in 1952; a heavily-revised black-cast version of Oh, Kay! failed to find an audience in 1990. (The vibrant revival history of Porgy and Bess – brought back to the commercial New York stage five times between 1942 and 2012 – underlines this work’s aesthetic distance from Gershwin’s other theater scores.) But if Gershwin’s musical comedy and operetta scores failed to survive on the commercial stage, many of Gershwin’s theater songs endured, forming the core of both the repertory of jazz standards and the so-called great American songbook of pre-rock and roll popular music heard in cabaret and concert and on record. Beginning in the 1980s, a modest trend of “new” Gershwin musicals using select theater and film songs and completely new scripts found success on Broadway. But these “new” musicals – like Gershwin’s originals from the 1920s and 1930s – invariably served the commercial requirements of their respective production moments and do not provide any sense for how the shows Gershwin made in his time worked musically, dramatically, or as spectacle. An effective performance of Gershwin’s concert works – set down by the composer in standard musical notation – allows us to assess his power as a composer in that realm. How might Gershwin’s achievement as a composer of scores and songs for the Broadway stage be understood and re-experienced in similar fashion?

As it happens, a late twentieth-century confluence of scholarship devoted to the popular musical stage, fortuitous archival finds, the height of the compact disc as a recorded music medium, and financial support from the Gershwin family produced a group of ten complete recordings of Gershwin scores for Broadway. This ambitious recovery project – sound-only versions of shows not viable for commercial production – applied the values and priorities of the historical performance movement to works of the American commercial stage. Gershwin’s reputation in the concert hall and efforts to bolster his stature as a great American composer surely played into these efforts. Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, a noted Gershwin interpreter, initiated this cycle of recordings with a 1987 disc for CBS Masterworks, an elite classical label, pairing the operettas Of Thee I Sing and Let ’em Eat Cake.3 While orchestrations for the former survived, the latter required reconstruction of the piano-vocal score by John McGlinn and orchestration in historical style by Russell Warner. In the early 1990s, the Leonore S. Gershwin – Library of Congress Recording and Publishing Project released five complete musical scores on the Elektra Nonesuch label, each with liner notes detailing the challenges of reconstructing both musical texts and performance styles: Girl Crazy (1930, 272 performances), the 1927 version of Strike Up the Band, Lady, Be Good!, Pardon My English, and Oh, Kay! (1927, 256 performances).4 The death of Leonore S. Gershwin, Ira’s widow, prematurely ended this project before the already-recorded 1930 version of Strike Up the Band! could be issued (PS Classics released this recording in 2011).5 In 2001, New World Records – a non-commercial label devoted to American classical and folk music – brought out a box set of Tip-Toes and Tell Me More (both 1925, 100 and 192 performances).6 The above Nonesuch and New World releases all feature restored scores supervised by archivist Tommy Krasker. Tip-Toes proves an especially important addition to these discs. A complete set of pit orchestra parts for Tip-Toes was found in an extensive cache of Broadway scores discovered in a warehouse in Secaucus, New Jersey in the 1980s. The Tip-Toes materials, in Krasker’s words, offered “one of the very few totally authentic orchestrations from the mid-twenties.”7 The interest, energy, and resources expended on reconstructing Gershwin scores as recordings in the late 1980s and 1990s was facilitated by the historic high point of the compact disc format. Since 2001, this sort of scholarly yet entertaining disc – together with the compact disc itself as a commercially dominant media – has largely disappeared. Indeed, only one further score has been released in the twenty-first century: in 2012, PS Classics issued Sweet Little Devil (1924, 120 performances), the musical comedy Gershwin wrote just before Lady, Be Good! with lyrics by B.G. DeSylva.8

The above body of reconstruction recordings offer invaluable aural introductions to Gershwin’s Broadway. (All but Tip-Toes, Tell Me More, Sweet Little Devil, and the 1930 Strike Up the Band are available on the streaming service Spotify.) Crucially, these discs present Gershwin’s theater scores as wholes, helping the listener understand how individual songs – familiar and forgotten – were originally joined into a larger musical theater entertainment. The discs go some distance to revealing the expressive integrity and aesthetic balance that marked these ephemeral Broadway products. Two caveats obtain regarding these recordings: orchestration and singing style. As noted, some original orchestrations survive and can be heard on these discs. However, most of the orchestrations were commissioned expressly for these recordings in a period style. The choice of singers on these discs generally favors musical theater professionals with Broadway experience. Hearing such singers deliver Ira’s lyrics as theater songs – articulating for an imagined back row and singing in character – proves especially valuable to dislodging familiar tunes from jazz and pop contexts. (Important musical aspects, often linked to jazz practices, are similarly highlighted by the sensitive insertion of improvised instrumental performance and tap dance.) But Gershwin often composed for specific performers and, in some cases, these performers recorded pop records of songs they were singing onstage. Such period recordings of original stars offer a vital supplement to the reconstruction discs and are referenced below when appropriate: most can be found on the streaming site YouTube. For the purposes of this introduction to Gershwin and Broadway, the reader is referred to the reconstruction discs as representative of each show. However, any deeper study of these works necessitates a finer-grained assessment of the sources.9

Scores and Songs

A new musical playing eight shows a week in a midtown Manhattan theater faced stiff competition in the 1920s. Lady, Be Good! opened in December 1924 to a field of nineteen competing shows. At one point in its run, the Gershwins’ Funny Face (1927, 250 performances) faced off against twenty-four competitors. With the onset of the Great Depression in 1930, the number of new productions plummeted and the construction of new theaters – still going strong in 1928 – stopped cold. When Of Thee I Sing opened in December 1931 there were only nine other musicals playing midtown; for much of the summer of 1932, Gershwin’s operetta was one of only three musicals still running (the other two survivors were by Jerome Kern). But for most of Gershwin’s Broadway career, the musical stage was a vital and expanding commercial arena consistently producing a high volume of product. A run of around 250 performances – about eight months – marked a solid success.

This rapid turnover in new musicals (by later and certainly contemporary Broadway standards) rewarded creators who worked quickly and confidently, as Gershwin did. Shows were made in a matter of weeks around the talents and personas of individual performers. Topicality informed the plots, the jokes, and the singing and dancing. Revues were constructed around comic sketches, often including song and dance, and production numbers and musical specialties. Musical comedies and operettas told two-, sometimes three-act stories through spoken dialogue and sung lyrics. The plots, especially in musical comedies, were often perfunctory. Still, as shown below, a fair amount of the music Gershwin composed in these story-centered genres (and especially in operetta) supported lyrics that set the scene or moved the story forward.

Broadway scores for revues, musical comedies, and operettas alike were made of songs structured around a thirty-two-bar chorus (usually including and repeating the song’s title) typically preceded in performance by a freer form verse. Different sets of lyrics for the verse (and sometimes the chorus) helped extend these rather short musical forms into numbers that could also include dancing (usually done to an instrumental arrangement of the chorus). (Operettas generally included some extended stretches of continuous music in varying forms.) Select songs in every musical score were chosen for marketing independently from the show. These separate song commodities had their own commercial lives in the popular music market as sheet music for domestic use and, more and more across the 1920s, also generated income on records and radio, emerging mass media platforms that, together with a show’s theatrical run, in turn encouraged sheet music sales. Overtures – rousing medleys of tunes from the score heard before the curtain when up and assembled shortly before opening night – hinted at the anticipated hit songs or, more cynically, tipped the listener to the tunes tapped for sheet music promotion by the show’s creators. Not every song in a show was a candidate for such “exploitation,” to use an industry term of art. For example, songs sung by the chorus to open acts or scenes were frequently too specific to the show’s story and setting to prove suitable for individual sale. Key to song exploitation from show scores were the ballads and rhythm tunes sung by leading characters that featured generic romantic or dance-oriented lyrics: such songs were designed as much for singing out of context as in. But these tunes were sometimes tailored to their original performers’ individual talents, in Gershwin’s case performers such as Fred and Adele Astaire and Ethel Merman.

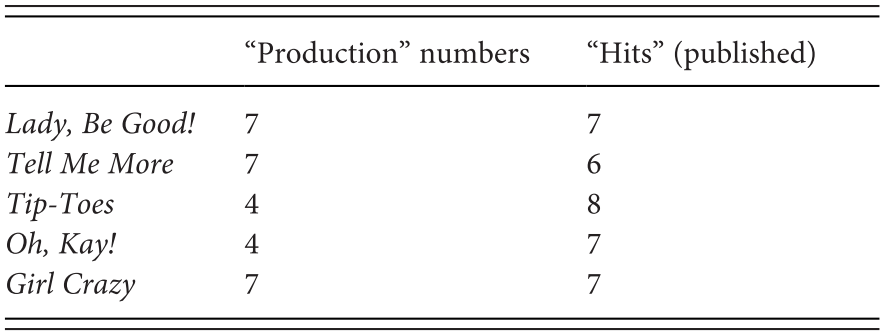

And so, to borrow two period terms from Goldberg, successful Broadway composers worked to write both “production” songs “intended for the stage spectacle chiefly” and “hits … aimed at the public purse.”10 An appreciation for this division between music for the show in the theater and music meant to translate to the pop music market proves a useful way to think about the compositional challenge faced by Broadway songwriters. The Gershwins were successful creators on the 1920s commercial stage because they could write both kinds of songs. The balance between “production” songs and “hits” in the Gershwins’ musical comedies varied (Table 6.1), but both types were crucial. This accounting of the number of discrete songs needed to make a musical comedy suggests the importance of “production” music: writing a Broadway score involved much more than simply writing “hits” that could sell.

“Production” music at the start of an act or scene used the men and (especially) the women of the chorus to usher the audience into the world of the show and the dramaturgical sphere of the musical as a genre, a theatrical space where singing and dancing require no dramatic excuse. Such numbers also immediately satisfy audience desire for song and dance (and performers who sing and dance as objects of desire; Goldberg described opening choruses as an excuse “to exhibit the female wares”).11 Choruses like “A Wonderful Party” and “Linger in the Lobby” (Lady, Be Good!) and “The Moon Is on the Sea” and “A Woman’s Touch” (Oh, Kay!) alike set the scene, whether a party, a public space, the beach, or a living room. Some such numbers divide the chorus into contrasting groups for a dramatic and musical effect: Tell Me More’s “Shopgirls and Mannequins” distinguishes between different female groups within a luxury department store setting, much as a number in a revue might, and sorts the female chorus almost literally into the standard Broadway categories of “ponies” (“girls” who dance and sing) and “clothes-horses” (“girls” who primarily parade in fancy clothes). Male and female choruses play contrasting roles in Girl Crazy’s “Bronco Busters”: the women excitedly arrive in a Western town from the urban East; the men, residents of the town, boldly declare their cowboy credentials. In Tip-Toes’s “Florida,” the men of the chorus enter first, selling options on real estate in the state’s land boom; the women of the chorus, entering second, turn out to be “brokers too.” The real-estate bubble that sets the topical tone for Tip-Toes has drawn in everyone and all join in a jerky, blues-inflected dance tune that, in the lyrics, references Irving Berlin’s 1911 hit “Everybody’s Doing It Now” (a ragtime dance song).

The music and lyrics the Gershwins provided for these book numbers – destined to be heard only in the context of the show – are consistently engaging and clever. “Lady Luck,” the scene-setting chorus number for the gaming tables at the Palm Beach Surf Club in Tip-Toes, concludes with a lyric and music quote from the Gershwins’ own “Oh, Lady Be Good,” plugging the title song from the pair’s earlier show but also suggesting a continuity across all their shows. In a Broadway context where new musicals played short runs and audiences craved novelty, such moments established a musical comedy world built on frequent theater attendance and a continuity of affect and energy that was attached not to one show only but to the creativity of special talents, such as the brothers Gershwin, whose tunes and shows opened a world understood by audiences to be distinctly “Gershwinian.”12 Gershwin’s music for musical comedy chorus is uniformly bright and snappy, with patter verses (many fast notes in even values) and strongly syncopated choruses that administer an energetic kick to the show (“Love Is in the Air,” a leisurely strolling tune opening Act II of Tell Me More, proves an exception). Ira’s lyrics often draw subtle but sharp attention to the artificiality of “production” music moments. In “A Wonderful Party,” a chorus of excited young people sing “sounds like our entrance cue,” a lyric that works as a sly critique of fashionable posing among the Smart Set (the characters are performing for each other) and as a self-reflexive moment (the number is, literally, the chorus’ entrance cue). The corporate nature of such lyrics allows for further comic touches that declare in no uncertain terms that song and singers inhabit the stylized world of musical theater. For example, the cowboys in “Bronco Busters” declare exultantly, in a moment of urban fashion awareness unlikely for real Westerners, that their “pants have never been creased.” Their chorus climaxes with a robust high note sung “à la Romberg,” a reference to well-known operetta composer Sigmund Romberg, that locates these cowboys firmly in the confines of the musical stage. The clarity with which the Gershwins wrote for the voice allowed these lyrics to be comprehended on first hearing – as, indeed, they had to be in the theater and can be on the reconstruction recordings. And Gershwin did not skimp on the music for these choruses. For example, the chorus of “Linger in the Lobby” juxtaposes a melody in triple meter against a duple meter accompaniment, in its own way as rhythmically complicated as Lady, Be Good!’s more famous syncopated “hit,” “Fascinating Rhythm.”

Some production songs include the names of characters or locations in the show. Others come across as less tightly connected to a show’s setting and instead as theatrical in a more general sense, as songs whose fundamental nature demands musical theater staging. For example, “Bride and Groom” (Oh, Kay!) would function perfectly well in a revue scene on a wedding theme. “End of a String” (Lady, Be Good!) and “When Do We Dance?” (Tip-Toes) both feature young people dancing in a domestic party setting. The former mines the inherent theatricality of a “cobweb party,” a Victorian parlor game where young men and women follow twisted ribbons around a room to find their dancing partners.13 Ira’s lyrics update this quaint game to the current younger generation, about whom there was great concern in the decade: using 1920s slang, the chorus members declare themselves “full of pep” and promise to be “a peppy partner” until three in the morning. In a more functional manner, “When the Debbies Go By” and “My Fair Lady” (Tell Me More) and “Dear Little Girl” and “Oh, Kay!” (Oh, Kay!) are purpose written to feature a leading performer in an energetic solo backed up by a chorus.

Songs conceived as special material for specific performers fall into a gray area between “production” music and “hits.” Lady, Be Good! includes four custom-made numbers for Fred and Adele Astaire: “Hang on to Me” (with a lyric about siblings, which the Astaires played in the show); “I’d Rather Charleston” (another sister–brother number added for London); “Juanita” (a comic Spanish routine for Adele and the show’s “boys”), and “Swiss Miss” (an end-of-the-evening excuse for nutty comedy – an Adele specialty – and the pair’s signature runaround, a sustained physical gag that had them high-stepping, side-by-side in increasingly larger circles to an oom-pah beat). Only the first two were judged potential “hits” and released as sheet music. To succeed on Broadway, the Gershwins had to be adept at writing special material for whomever was brought into a show, be it the scat-singing pop singer Cliff “Ukulele Ike” Edwards (Lady, Be Good!), for whom they wrote the jazz-centric tunes “Fascinating Rhythm” and “Little Jazz Bird” (both published), or comedian Lou Holtz (Tell Me More), for whom they crafted a waltz full of Jewish jokes titled “In Sardinia,” or the dancer Queenie Smith (Tip-Toes), for whom the show’s title song provided a chance to show off her signature dancing (neither published). In the case of Ethel Merman, special material for the role of Kate in Girl Crazy famously made her a star. Merman/Kate sang three numbers: “Sam and Delilah,” a bluesy ballad, immediately followed by “I Got Rhythm,” near the end of Act I; “Boy! What Love Has Done to Me,” a wry torch song near the close of Act II. “I Got Rhythm” – like “Fascinating Rhythm” – stands alone: a historically successful “hit” that was put over in Girl Crazy in a manner that made Merman an instant star.14 Merman’s other two tunes were crafted to fit her character and the show more closely: the “he done her wrong” lyric of “Sam and Delilah” strikes an appropriately non-urban note for Girl Crazy’s Nevada setting and a character hailing from the “wilds” of San Francisco; the verse of “Boy! What Love Has Done to Me” deals with Kate’s specific problems and includes her name and that of her lover, Slick. All three of Merman’s songs were published. Each of the above described numbers was an excuse for a star performer to meet their Broadway audience. In each case, the Gershwins opened a custom-tailored space within a given score where this encounter could take place to the best advantage of all: the performers, the audience, the show, and – in a few cases – the song itself as a commodifiable “hit.”

Gershwin’s “hits” – extractable songs built for independent, hopefully profitable lives – can be sorted into the two main categories of popular music at the time: ballads and rhythm tunes. The Gershwins’ excelled in the making of ballads with an up-to-date attitude: love songs, introduced by leading players, frequently sung as duets but usually also workable as solos, with lyrics that dissected modern love in an often rueful but never sentimental tone. The predictable shapes of musical comedy plots (boy meets girl, complications ensue, boy gets girl) played into the generic address of these ballads and the connection of the lyrics to the specifics of any given show’s story is, with a few exceptions, altogether loose.15 George’s melodies encourage rhythmically vital performance at a moderate tempo in a popular style: these are smart, not sentimental love songs where the words matter. Subtle touches give several of these tunes an unmistakably “blue” edge; for example, the unaltered and lowered third scale degrees alternating in the A phrases of “Looking for a Boy.” These ballads are eminently singable by just about anyone: they do not require trained voices, do not have propulsive patter rhythms (as “production” choruses often do), and favor an informal, breezy delivery. In this, the leads in a Gershwin musical comedy often sang less technically challenging music than did the chorus members. The combination of clear-eyed lyrics and lightly rhythmic melodies helped transfer more than a few of these ballads to the pop marketplace and beyond that into the canon of jazz and pop standards.16

Rhythm tunes, often with lyrics about the power of rhythm, were central to the Gershwins’ “hits.” These songs often suddenly and somewhat arbitrarily jumpstarted the proceedings in their shows of origin, more loosely connected to the plots than the ballads (which required love stories to make minimal dramatic sense). With their frequent allusions to jazz and blues, extractable rhythm songs often drew links to popular culture outside the theater, an expected strategy for a song designed to, literally, live beyond the confines of the show in which it was introduced. Given the frequent appearance of racially coded or direct lyrics referencing jazz and blues, rhythm tunes about the power of rhythm are discussed in detail in the following section.

As Goldberg notes, “Not all the fine music [in a show] was printed for the racks of the parlor pianoforte.”17 A curious type of rhythm tune, commonly found in Gershwin’s musicals, was not typically seen as a candidate for publication. All five shows discussed here include a frisky male–female rhythm duet, often with sexual undertones, and usually sung by the show’s secondary or tertiary couple. These include: “We’re Here Because” (Lady, Be Good!), “How Can I Win You Now?” and “Baby!” (Tell Me More), “Nice Baby! (Come to Papa!)” (Tip-Toes), and “Don’t Ask” (Oh, Kay!). The male solo “Treat Me Rough” (Girl Crazy), sung to a bevy of chorus girls, also fits this category. In all these numbers, the implied tempo is brisk and the tune is smartly syncopated – suitable for dancing – but, as several of the titles suggest, the lyrics carry flirtatious content laced at times with sexual innuendo (or as much as Ira, a rather prudish lyricist – compared to Cole Porter, for example – allowed himself). Such numbers – apparently seen as essential to the variety of an evening in the theater – were not, generally, viewed as candidates for publication: only “Baby!” and “Nice Baby! (Come to Papa!)” from the above songs were issued as sheet music. Perhaps this type of song was judged too difficult for amateurs to pull off, implying the need for strong, highly theatrical performance by comic singing actors in the theater to succeed. Whatever the strategy, it was assumed that sheet music buyers did not especially want to take this kind of theater song home for parlor use.

But while “hits” were intentionally made to be commercially transferrable outside their respective shows, they can often be found serving important plot or character functions within a show’s score by way of reprises and re-written lyrics. The line between “production” songs and “hits” is far from clear in these examples, which do not suggest integration of music and plot – as found in operettas more generally and in the musical plays of later Broadway decades – so much as an attempt to tie the music in a musical comedy score together as tightly as possible. For example, “Oh, Lady Be Good” is sung multiple times in the eponymous show with sly changes to the title lyric. Initially, the character Watty Watkins addresses the song to Suzie, singing “Suzie be good,” when enlisting her in a scheme to impersonate the widow of Jack Robinson. When Suzie refuses, Watty transfers his attentions to a group of willing chorus girls and sings “lady be good.” A cute production number ensues. In neither case does the full chorus lyric make much sense, especially the line about the singer being alone in a “great big city” (Lady, Be Good! is set among the upper crust of Beacon Hill, Rhode Island). But the song’s repeated and earnest if casual plea from man to woman – the yearning yet snappy descending gesture that sets the title – works in both cases. In Act II, the tune returns, this time sung as “wifey be good” by Jack Robinson as a teasing taunt to Suzie (who eventually does impersonate Jack’s supposed widow). And so, in the context of the score, “Oh, Lady Be Good” functions multiple ways to tie the musical whole that is Lady, Be Good! together. (On the reconstruction recording these connections can be experienced by the listener.) “Fascinating Rhythm” serves a similar function in the same show, its lyric recomposed for the finale as “fascinating wedding” with each of the show’s four couples given a moment to consolidate their affections in song – a labor of the lyricist and not the composer. This formal approach – re-written lyrics to an extractable ballad serving plot development during a finale – also occurs in Tip-Toes, with “That Certain Feeling,” and in Oh, Kay!, with the Act I finale’s wholesale revision of the lyric of “Maybe” into a choral response to the revelation that “It was Jane!” making noise in the master’s bedroom.18 The above examples draw mostly on the lyricist’s art: Ira was tasked with making these moments work. A more musically expressed tying of the score together can be heard in “Tell Me More,” which has the chorus respond to a leading character with the useful phrase “tell me more” on several occasions across the score.

The balance between “production” numbers, native to a given show’s world, and “hits,” designed for standalone success, tips strongly in favor of the former in the case of Gershwin’s three operettas. Built on the model of Gilbert and Sullivan’s operettas composed for London in the late nineteenth century, the lyrics for almost every song in Strike Up the Band, Of Thee I Sing, and Let ’em Eat Cake include show-specific content, whether related to the plot and characters or delivering a satirical blow against whatever political or cultural establishment sits in a show’s crosshairs. The Gershwins did not write florid extractable love songs typical of Broadway’s romantic operettas – such as the hit songs “Serenade” in Rudolf Friml’s The Student Prince in Heidelberg (1924) or “Lover, Come Back to Me” from Romberg’s The New Moon (1928). Political operettas offered few openings for non-ironic romance or even flirtation between romantic couples; for example, the romantic leads in Of Thee I Sing are most strongly linked by the man’s attraction to the woman’s wonderful corn muffins. Furthermore, the themes of the Gershwin operettas worked against the making of extractable popular “hits.” Strike Up the Band is a bitter burlesque of war-mongering on the part of American big business and of militarism generally in American culture. Of Thee I Singand Let ’em Eat Cake alike present a cynical, frequently incompetent nexus of politics, the media, and sex. The latter show engages with the rise of fascism in Europe and toys with nihilism in its most indicative number, “Down with Everything That’s Up.” There’s some evidence Gershwin and his collaborators recognized the need for an extractable tune or two in the operettas. One of the substantive changes made in the revised Strike Up the Bandof 1930 – which unlike the 1927 version made it to Broadway – was the addition of two ballads: “Soon” (an easy fit for any musical comedy) and “I’ve Got a Crush On You” (interpolated from the Gershwin’s Treasure Girl [1928, 68 performances], which had failed to hold an audience). The tune for “Soon” was heard in the 1927 version of Strike Up the Band as part of an extended finale with words relating only to the plot – another bit of evidence that Gershwin approached “production” music with a full investment in its melodic potential.

Black Music in White Shows

Rhapsody in Blue for “jazz band and piano” made a splash on the New York scene in February 1924 in a concert at Aeolian Hall. Ten months later, Lady, Be Good! opened at the Liberty Theatre. These two venues hosting Gershwin premieres were located within three blocks of each other on West 42nd Street. Audiences heard the two works as similarly marked by select inclusion of the new syncopated popular music of the day: a music called jazz.

Jazz rapidly displaced ragtime as the urban dance music of choice shortly after the end of World War I in 1919, just as Gershwin was assuming composing duties for George White’s Scandals. Like ragtime, jazz grew out of and was closely associated with African American migration and the growth of black urban populations in Northern cities. Also, like ragtime, jazz was linked to new social dances innovated by the black working class and taken up by the white middle class. Gershwin’s Broadway songs and scores brought jazz song and dance to the New York (and London) musical stage. In this, Gershwin was following the lead of Irving Berlin, who had introduced ragtime themes and rhythms to the Broadway stage in the pre-World War I years.19 (Indeed, among the first songs Gershwin wrote with lyrics by his older brother Ira was “The Real American Folk Song (is a Rag),” a tune interpolated in the 1918 show Ladies First. The topical title and lyric rendered the song decidedly out of date shortly after its premiere.)

Jazz in the 1920s was both an array of musical practices revealed in performance – such as tempo, rhythmic style, choice of instrumentation, or improvised passages – and a set of textual references evident in a song’s title, lyrics, melody, harmony, or accompaniment as found in sheet music. Jazz as musical practice and textual reference show up across Gershwin’s Broadway scores and songs. Musical personnel provide evidence for occasions when jazz as musical practice was part of a Gershwin show. Popular duo pianists Victor Arden and Phil Ohman were featured in Lady, Be Good!, Tip-Toes, Oh, Kay!, Funny Face, and Treasure Girl – sometimes onstage – and were known to improvise on tunes from the score during intermission and after final bows “for the fans who refused to go home” (recalled Fred Astaire of Lady, Be Good!).20 Strike Up the Band (on Broadway) and Girl Crazy both included young white jazz greats such Benny Goodman, Red Nichols, Jimmy Dorsey, Gene Krupa, Glenn Miller, and Charlie and Jack Teagarden on winds and brass, lending the pit orchestra a dance-band quality.21 Given the intense topicality of musical comedy, jazz and blues references in the text of a Gershwin show – most prominently in Ira’s lyrics – can be understood as of a piece with the genre’s persistent popular culture references, be it to current events, other Broadway shows, or to advertising (e.g. a laugh line in Lady, Be Good! referenced the Camel cigarettes slogan).22

Gershwin’s Broadway shows are all set within white milieus: department stores, hotel lobbies, posh beachfront estates, a small Nevada town, the halls of political power in Washington DC, and Dresden, Germany. No performer of color played a leading or featured role in any of these shows and the members of the chorus were, similarly, visibly all white. Like most Broadway musicals across the twentieth century, Gershwin’s shows staged imaginary worlds devoid of African Americans where the complicated history of racial segregation in the United States is completely set aside – except when African American music or dance were part of the show. When – in this segregated context – were jazz or blues given a nod or directly performed?

The 1920s practice of slumming – white spectators traveling to a black area of town to enjoy African American music and dance, a much-discussed activity in the decade – was never represented onstage in a Gershwin show but was instead, on two occasions, described in song. The verse to “Sweet and Low-Down” (Tip-Toes) paints a picture of a “cabaret” the singer recommends: the “pep” to be found there offers a “tonic,” tapping into a current notion that jazz could renew the lost vitality of enervated white listeners. The tune’s chorus instructs the listener to “grab a cab” and travel to said club located in a vague but class-specific “down” location. Further cues, such as biblical references (“milk and honey”) and the racially marked word “shuffling,” indicate that the “syncopation” to be found at this “cabaret” derives from African American sources: the “band” blowing “that Sweet and Low-Down” is clearly black (why else travel “down” in the first place?). The A phrases of Gershwin’s AABA tune are built on a fourfold iteration of a bouncy, syncopated rhythmic idea followed by the invocation “Blow that Sweet and Low-Down.” Ira’s lyric, written after George composed the tune, puts the title phrase, preceded by an imperative verb, inside quotation marks, inviting the song’s singer to play a part in the musical energy of the club: the singer of “Sweet and Low-Down” calls out to the lyric’s imagined band – with a high, held note on the word “blow” – in a speech act that can be understood as both a command (“play that music”) and a response (“yes, that’s it”) signaling recognition on the part of the singer as to what jazz sounds like. The implied drama of the lyric and the tune crosses the color line – white singer/listener commanding and/or affirming black musicians playing in a style understood to be their unique racial gift. In Tip-Toes, “Sweet and Low-Down” was, in Ira’s words, “sung, kazooed, tromboned, and danced … at a Palm Beach party.”23 Performed in the Liberty Theatre on 42nd Street – where any visibly black patrons would have been relegated to the balcony in practice if not by law – this number displaced an interracial encounter (white singers and dancers with black music) to an effectively all-white space: in sum, “Sweet and Low-Down” named and enacted onstage the cultural work being done by musical comedy in the midtown theater district by putting black music into white mouths and bodies in an effectively all-white zone.

The song “Little Jazz Bird,” a specialty number for Cliff “Ukulele Ike” Edwards in Lady, Be Good!, extends a similar if more veiled invitation to white listeners to learn to “syncopate” by slumming: a “songbird” flies into a “cabaret,” hears a “jazz band,” stays “till after dark,” and finds that “singing ‘blue’” helps him shed his “troubles.” The distance Ira’s lyric affects between the bird (understood as a white listener) and black culture is telling: the practice of “singing ‘blue’” is kept at a remove and understood as a performance; the word “blue” set apart in quotes, nicely setting the seventh scale degree. “Sweet and Low-Down” and “Little Jazz Bird” typify the rather modest degree to which jazz and blues were mentioned in the Gershwins’ musical comedies: their white Broadway audience, more sensitive to the new sounds of jazz than listeners are today, would have caught these small touches well enough.

Rhythm tune “hits” lent themselves particularly well to the sort of brief invocations of black music typical of the Gershwin show with an all-white cast and, given their positioning within the show, these tunes would have marked these musical comedies as especially engaged with current trends in popular culture. Four of the five shows discussed at length here included a rousing jazz-themed rhythm number at the midpoint of Act I, then reprised the tune at the end of the Act I finale, sending the audience into intermission tapping their toes to syncopated dance tunes that bore specific connections to black culture. “Sweet and Low-Down” served this function in Tip-Toes. In Tell Me More, “Kickin’ the Clouds Away” plays the exact same structural role. The song’s verse begins with the singer framing the chorus to follow as a “spiritual” (an alternate version reads “Southern spiritual”) suitable for every home with a “phonograph.” The distance between black and white is here bridged by a popular music commodity – the record – instead of the act of slumming. The accompaniment texture in the sheet music – thick block chords on every beat – supports the notion in the lyric. (This standard textural indicator of the blues also appears in the verse to “I’ll Build a Stairway to Paradise,” used to end Act I of George White’s Scandals of 1922.) The chorus lyric to “Kickin’ the Clouds Away” promises to make the listener happy – to “kick” away any lingering clouds – and uses the slangy exhortation “Hey! Hey,” again in quotes, Ira’s distancing way to include a hip phrase without adopting it into his own voice. In “Clap Yo’ Hands” (Oh, Kay!), Ira drops the quotation marks and moves in rare fashion entirely into black popular music slang: the title phrase, spelled throughout as “clap-a yo’ hand!,” repeated cries of “Halleluyah!,” biblical references to “the Jubilee” and, most surprisingly, a lapse into dialect, with “the Debble.” The spoken song cue dubs the tune “a Mammy song,” effectively putting the entirety of “Clap Yo’ Hands” under the sign of blackness. All the above numbers celebrate the power of music understood to be black in origin to cure the troubles or bring happiness to whomever sings or dances along – in this context, fashionable, white youth. Energetic, rousing songs designed to elevate the spirits are central to Broadway’s historic emphasis on feel-good entertainment. Linking such sentiments to blackness was in no way required in the latter 1920s. Indeed, the Gershwins wrote other rhythm “hits” that make no reference to blackness as a necessary “tonic” and simply advise the listener to be optimistic about life – for example, “It’s a Great Little World” (Tip-Toes) and “Heaven on Earth” (Oh, Kay!).

In the early 1920s, jazz was a controversial music, slowly moving toward general acceptance among white audiences. Bandleader Paul Whiteman’s description of Rhapsody in Blue and its concert hall premiere as an attempt to “make a lady” out of jazz signaled these anxieties in February 1924. The important music magazine The Etude highlighted “The Jazz Problem” in its August and September issues that same year, with prominent white male musicians and cultural figures weighing in on the music, many with grave concerns about its dangers. But jazz was winning this debate – Rhapsody in Blue rapidly became a global hit – and Lady, Be Good!, opening in November, offered jazz made safe for Broadway whiteness in the breakout performances of Fred and Adele Astaire. The Astaires’ personas as Jazz Age exemplars of youthful urban whiteness, unafraid of and glorying in the new syncopation, were reinforced several times over in the Gershwins’ score. (The dancers Vernon and Irene Castle – models for the Astaires – did similar cultural work on behalf of ragtime music and dance on the Broadway stage in Irving Berlin’s 1914 musical Watch Your Step.)

Like the rhythm tunes described above, “Fascinating Rhythm” was Lady, Be Good!’s Act I rouser and finisher. The number built from a solo for Cliff Edwards, into a duet for the Astaires, then, in the words of the script, into a “BIG ENSEMBLE DANCE NUMBER USING ALL THE GIRLS AND BOYS.” (There were twenty-four women and twelve men in the chorus, typical numbers for a Gershwin show.) The lyric to “Fascinating Rhythm” speaks, in the first person, of the singer being obsessed with a syncopated pattern that “pit-a-pats” through his brain and that he fears will drive him to insanity. The chorus lyric, addressed to the “fascinating” rhythmic pattern itself, has the singers begging to be set free, longing to live their former lives, before the rhythm started “picking” on them. Ira’s lyric neatly captures the dilemma some white listeners felt in the face of the new syncopated music, but it does so without dropping any load of moral opprobrium on jazz or without implying the music has any specific racial origins. All the rhythm does is get in the way of daily life. Crucially, any effective performance of “Fascinating Rhythm” ends up being a celebration of the new rhythmic world of jazz. Edwards, the Astaires, and the boys and girls of the Lady, Be Good! chorus helped secure such jazz “fascination” as something wholly part of the world experienced by fashionable, white elites – indeed, as an attractive and desirable feature of modern urban subjectivity. In short, the lyric protests too much: jazz is here to stay and, as Ira’s later lyrics suggest, offers a positive development in white culture. (Later songs following the model of “Fascinating Rhythm” include “Fidgety Feet” from Oh, Kay! and “I Got Rhythm” from Girl Crazy.)

The return of “Fascinating Rhythm” at the close of Act I staged just how delightful life with that “pit-a-pat” in your brain could be. The Astaires’ brother and sister characters, Dick and Suzie, are arguing loudly when Victor Arden and Phil Ohman, duo pianists onstage as specialty performers within the party scene, begin playing a reprise of the song. Verbal argument and jazzy musical specialty compete and the music – the rhythm – wins: Dick delivers the act’s final line, “Why is it every time we are having a good fight, somebody has to play that tune?” Stage directions describe what happened next: “The tempo proves too infectious for Susie and Dick, and they start dancing together. Business, during dance, continuing quarrel. Susie licking [sic.] Dick – making faces at one another etc. Work dance up to big climax and CURTAIN.” The word infectious, invoked here with no sense of societal danger, tracks a mid-1920s shift from jazz as cause for concern to jazz as a hallmark of youthful high spirits and vitality.

Fred Astaire powerfully embodied the new jazz-infused, white style on the Broadway stage that Gershwin introduced with such conviction in the concert hall. Indeed, the sensibilities of the two – both informed by black music – were understood to be remarkably similar. Kay Swift, Gershwin’s confidante and musical assistant, recalled in 1973, “Astaire and Gershwin were particularly one in music and dance. The dance expressed the music so well.” Astaire himself recalled, also in 1973, that he and Gershwin “had a good little game going with each other,” where both suggested ideas in the other’s domain: Gershwin in dance, Astaire in music.24

The title and lyric of Astaire’s solo in Lady, Be Good!, “The Half of It, Dearie, Blues,” explicitly and cheekily paired the racially specific musical indication “blues” with white 1920s slang of the sort Ira liked to mine for his lyrics. (A girl tosses off the line “You don’t know the half of it, dearie” in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s 1920 story “May Day.” It was also the catch phrase of the white vaudeville female impersonator Bert Savoy, who died in 1923.) But the full lyric is positively old-fashioned: the singer longs to wed. Ira’s pop culture reference and the song’s traditional sentiment are wrapped in music that tapped the current understanding of “blues” and that welcomed jazz-oriented performance, as one African American musical authority recognized. W. C. Handy, composer of “The Saint Louis Blues” (1914, the first pop blues song hit) and known as the “Father of the Blues,” included annotated sheet music for “The Half of It, Dearie, Blues” in his 1926 book Blues: An Anthology. Handy put the song beside excerpts from Rhapsody in Blue and Gershwin’s Concerto in F as evidence for the composer’s “place as a second pioneer in blues territory.” The annotations involved sample “breaks … fillers-in between the phrases of the old blues.”25 Astaire improvised his own breaks in tap dance onstage in Lady, Be Good! Astaire and Gershwin’s 1926 recording of “The Half of It, Dearie, Blues,” made during the show’s London run, reveals similar investment by Gershwin and Astaire in musical styles being innovated in Harlem in the 1920s: jazz tap and stride piano, respectively. In their respective areas on this disc, Astaire and Gershwin display evidence they had journeyed “down” to the sort of cabarets described in “Sweet and Low-Down” and listened closely: for these white men, slumming was professional research. Their similar career breakthroughs in 1924 mark the mainstreaming within white establishment culture of black-infused syncopated musical performance by young white talents who enjoyed access to the concert hall and Broadway stage their black peers and models did not.

All the rhythm numbers described above were introduced by men. Women on the stage at the time, especially the “girls” in the chorus, might join in and dance, but the jazz “tonic” was first served by men. And while men like Gershwin and Astaire might be in a position to make jazz “a lady” in the concert hall or on Broadway, the relationship of leading ladies to jazz in the Gershwins’ musical comedies proves more tentative. For example, Adele Astaire was less identified with jazz and more praised for her silly faces and “nutty” persona. The Astaires’ specialty number late in Lady Be Good!, “Swiss Miss” (recorded by the duo in 1926), captures Adele’s comfort zone as a performer (while also providing ample evidence for the Gershwins’ ability to compose to order for established personalities). Other recordings, such as the Astaires’ version of “Hang On to Me” with Gershwin at the piano, suggest Adele did not inflect her singing with the jazz-derived rhythmic style that was Fred’s signature. On this disc, George and Fred shape their respective fills within a common feeling of swing: George slyly leans on a syncopated triplet figure; Fred falls right into this relaxed, stride-derived groove. Adele, in sharp contrast, phrases stiffly with square little fills set against George’s swung triplets.

The London Lady Be, Good! included a new duet for the Astaires: “I’d Rather Charleston,” with music by George and lyrics by Desmond Carter. This rhythm tune situated the Astaires in the popular dance craze of the mid-1920s, casting Adele as a young lady gone “dancing mad” and Fred as a frowning fuddy duddy of a brother. The song’s conceit, however, gets the Astaire siblings precisely backwards: Fred was much more likely to Charleston than Adele. On their 1926 recording, Adele sings the syncopated rhythm of the Charleston in as square a manner as possible and gives no musical expression to the lyric about the dance making her feel “elastic.” Adele, a major star of the 1920s, was surely too good of a dancer not to have felt the pulse of her times. Any performer with her credentials did not do things accidentally. The squareness in her style was a choice – just as rhythmic flexibility was for her brother. Gender holds a key to understanding why the brother gets to swing while the sister stays square. In her recording of “I’d Rather Charleston,” Adele comes off as a girl who wants to Charleston but doesn’t know how – a girl who is not especially experienced, who apparently has not gone slumming, who has only heard about the Charleston and is certainly no expert in the dance. She remains a suitably marriageable young white woman, an ingénue worthy of a wedding at show’s close. And indeed, in 1932 Adele Astaire left the stage, married Lord Charles Cavendish, and moved into a castle in Ireland. Not putting her whole self into a dangerous new beat like the Charleston kept Adele to one side of a cultural line while also offering her Broadway and West End audiences a glimpse across that line, into the world of syncopated social dancing they had perhaps heard about but which was not necessarily onstage in all its glory. A similar moment was offered Gertrude Lawrence in the title song to Oh, Kay!, which had British stage star sing a slangy “Hey! Hey!,” spiking her big number with just enough jazz to show she was up to date but not enough to compromise her credentials as an ingénue (a stage type defined by whiteness as much as conventional femininity).

The blues persona that was open to white women was that of the torch singer, “a specialized blue mood in which is sung (by a female) the burning pangs of unrequited love.”26 The Gershwin shows set among fashionable East Coast society opened no space for such low-down female characters. Girl Crazy and Pardon My English, however, did. In the former, Merman’s Kate hails from San Francisco – a “down” location for finding “red hot” music, as suggested in the lyric for the song “Barbary Coast.” Two of Merman’s songs suggest a torch singer persona informed by “low-down” music: “Sam and Delilah” and “Boy! What Love Has Done to Me.”

In analogous fashion, the Dresden cabaret singer Gita in Pardon My English sings two torchy songs, although her numbers are more analytical. “The Lorelei” spikes the German legend of a singing female river creature who lures sailors to their deaths with a jazzy idiom taken from the black bandleader Cab Calloway: Gita’s German temptress sings in Harlem-ese – “hey ho dee ho hi dee hi” – that, by 1933, had been fully absorbed into the global white mainstream. Offering a more concrete geographical explanation, Gita’s Act II solo “My Cousin in Milwaukee” spells out the source of her skills – an émigré relative, resident in an American city with a large German population, who sings “hot” and “blue” and “always gets the men,” she explains, “taught me how.” Lyda Roberti introduced the role of Gita. Born in Warsaw to a showbiz family, Roberti built a short American stage and film career on comically accented and fractured English and a sexy, giggling, bleached blonde, shimmying-shoulders persona (exemplified in her recording of “My Cousin from Milwaukee”). On the 1994 reconstruction recording of Pardon My English, the role of Gita is taken by African American performer Arnetia Walker, a performer with Broadway experience in black-cast shows like The Wiz (1975) and Dreamgirls (1981). Walker substitutes Roberti’s now perhaps offensive (or just unfunny) bad English and oversexed persona with a forceful belted vocalism and a flexible rhythmic sensibility that stays just this side of the black diva persona familiar from many post-1970 Broadway scores. Walker sings her numbers straight, with no gospel-derived pyrotechnics.27 Her approach delivers Gershwin’s songs, with their textual links to jazz and blackness, in a style more appropriate for a 1990s listener: in the process, the original show’s joking use of Roberti and equation of black style with ditsy sexual availability is lost.

Gershwin’s scores for the Broadway stage, built to succeed under specific conditions, are period pieces in form and content. And while reconstruction recordings might restore each show’s combination of “production” songs and “hits,” the larger theatrical whole of these musicals in live performance in a Broadway theater is gone forever. Still, examining the shows George and Ira made for Broadway – a creative arena that defined their partnership – adds nuance to our understanding of Gershwin’s achievement as a songwriter and expands to the realm of commercial musical theater his importance as a white concert hall composer known for incorporating jazz content into his music.