Introduction

There were over 50 000 overdoses involving opioids in the United States in 2017 (Ahmad et al., Reference Ahmad, Rossen, Spence, Warner and Sutton2017), which has contributed to an overall decline in life expectancy (Dowell et al., Reference Dowell, Arias, Kochanek, Anderson, Guy, Losby and Baldwin2017). There were over 44 000 suicides in the United States in 2016, representing more than a 30% increase since 1999 (Hedegaard et al., Reference Hedegaard, Curtin and Warner2018). Military veterans are at particularly high risk of overdose and suicide and have nearly twice the rate of suicides relative to the general population (Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Suicide Prevention, 2018). Veterans with an opioid use disorder (OUD) have among the highest rates (~120/100 000 person-years) of suicide even when compared to veterans with psychiatric disorders (Bohnert et al., Reference Bohnert, Ilgen, Louzon, McCarthy and Katz2017; Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Suicide Prevention, 2018). Overall, suicides involving opioids nearly tripled from 1999 to 2014 (640 to 1825, respectively) (Braden et al., Reference Braden, Edlund and Sullivan2017), despite the potential 10–30% underreporting given challenges of classifying overdoses as suicides and other reasons (Rockett et al., Reference Rockett, Smith, Caine, Kapusta, Hanzlick, Larkin, Naylor, Nolte, Miller, Putnam, De Leo, Kleinig, Stack, Todd and Fraser2014). The association of suicidality and opioid use is also reflected in non-fatal suicide outcomes as prescription opioid misuse is associated with suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts (Ashrafioun et al., Reference Ashrafioun, Bishop, Conner and Pigeon2017). Suicide attempts are particularly important outcomes because they occur more frequently than suicides, are a robust predictor of suicide and a significant burden on healthcare utilization, and often involve substances such as opioids (Shepard et al., Reference Shepard, Gurewich, Lwin, Reed and Silverman2016; Olfson et al., Reference Olfson, Wall, Wang, Crystal, Gerhard and Blanco2017).

Psychiatric comorbidities are key predictive factors of suicide and overdoses (Ilgen et al., Reference Ilgen, Bohnert, Ignacio, McCarthy, Valenstein, Kim and Blow2010; Bohnert et al., Reference Bohnert, Valenstein, Bair, Ganoczy, McCarthy, Ilgen and Blow2011). Furthermore, lifetime OUD, heroin use, and being prescribed long-term opioid therapy are associated with greater onset, prevalence, and recurrence of psychopathology, including depression, PTSD, and anxiety disorders (Martins et al., Reference Martins, Keyes, Storr, Zhu and Chilcoat2009; Martins et al., Reference Martins, Fenton, Keyes, Blanco, Zhu and Storr2012; Barry et al., Reference Barry, Cutter, Beitel, Kerns, Liong and Schottenfeld2016; Scherrer et al., Reference Scherrer, Salas, Copeland, Stock, Ahmedani, Sullivan, Burroughs, Schneider, Bucholz and Lustman2016a, Reference Scherrer, Salas, Copeland, Stock, Schneider, Sullivan, Bucholz, Burroughs and Lustman2016b). Although psychiatric disorders are robust risk factors of suicidal behavior and co-occur with OUDs at high rates, there is a paucity of research on the impact of their comorbidity on suicide risk.

The effect of comorbid OUD and psychiatric disorders can be assessed by comparing the comorbidity's combined contribution to suicide risk to each of the individual contributions (Britton et al., Reference Britton, Stephens, Wu, Kane, Gallegos, Ashrafioun, Tu and Conner2015). Effects are conceptualized as being sub-additive when the sum of the individual contributions is less than their combined contribution (Nock et al., Reference Nock, Hwang, Sampson and Kessler2010). They are conceptualized as being additive when the sum of the individual contributions is equivalent to the combined contribution (Britton et al., Reference Britton, Stephens, Wu, Kane, Gallegos, Ashrafioun, Tu and Conner2015). Effects are conceptualized as being synergistic when the sum of the individual contributions are greater than the combined contribution (Gradus et al., Reference Gradus, Qin, Lincoln, Miller, Lawler, Sorensen and Lash2010). In prior analyses, we found a sub-additive effect of alcohol use disorders on depression for suicide attempts among veterans being discharged from inpatient hospitalization (Britton et al., Reference Britton, Stephens, Wu, Kane, Gallegos, Ashrafioun, Tu and Conner2015), but the nature of the relationship between opioid and psychiatric disordered has yet to be tested. Because individuals with OUDs and psychiatric disorders experience greater negative consequences (e.g. reduced quality of life, depression recurrence, increased pain severity) than either alone (Carpentier et al., Reference Carpentier, Krabbe, van Gogh, Knapen, Buitelaar and de Jong2009; Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2018), there is a potential for an additive or synergistic effect when considering suicide risk.

Understanding the nature of the effects of such comorbidity can help inform the need for tailored interventions for patients with complex presentations. It may be beneficial, for example, to address comorbidities concurrently because they independently increase the risk for negative outcomes such as suicide attempts. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis found that individual risk factors are modest predictors of suicidal behaviors and that prospective assessments of co-occurring risk factors are needed in at-risk populations to better understand their contributions when combined (Franklin et al., Reference Franklin, Ribeiro, Fox, Bentley, Kleiman, Huang, Musacchio, Jaroszewski, Chang and Nock2017). With these considerations in mind, the purpose of this study was to assess the associations of comorbid OUDs and psychiatric disorders with suicide attempts among veterans seeking pain care. We chose veterans seeking pain care as pain is associated with greater risk of OUDs, psychiatric disorders, and suicidal behaviors, providing a rich source of at-risk veterans with comorbid opioid use and psychiatric disorders (Kerns et al., Reference Kerns, Philip, Lee and Rosenberger2011; Barry et al., Reference Barry, Cutter, Beitel, Kerns, Liong and Schottenfeld2016; Ashrafioun et al., Reference Ashrafioun, Kane, Bishop, Britton and Pigeon2019). We hypothesized that both OUD and common psychiatric disorders (i.e. depression, alcohol use disorders, PTSD, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder) would be independently associated with suicide attempts in the year following the initiation of pain care, and that their effect on risk would be additive.

Method

Study population

The cohort consisted of veterans who had initiated Veterans Health Administration (VHA) pain care in fiscal years 2012 through 2014. Pain care was identified using a billing code that helps facilities define provider workload credits visits related to pain for both primary and secondary reasons. The billing code (i.e. stop code 420) is used for a range of pain-related services that vary from VHA facility. The index visit was the first pain care visit during the study period. The cohort did not include any veterans who had used these services within a year of their index visit to capture those who were transitioning to a higher level of pain care. This period of transition was selected given that veterans referred to these services have increased medical and psychiatric comorbidity (Kerns et al., Reference Kerns, Philip, Lee and Rosenberger2011) placing them at higher risk of suicide (Ashrafioun et al., Reference Ashrafioun, Kane, Bishop, Britton and Pigeon2019). We also excluded 2389 cases who had an attempt in the previous year to assess risk of one's first or more recent attempt (as we did not have lifetime data available). An additional 14 024 cases were excluded because they were the same veteran included multiple times in the dataset. The first time they were included in the dataset was retained. Two more cases were excluded because of missing data for the bipolar disorder variable leaving a total of 226 444 veterans in the final analyses. The study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board.

Data sources

The Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) was used to identify the study population and extract demographic, medical record-identified suicide attempts, psychiatric diagnoses, and physical health problems, and opioid prescriptions. The CDW is a comprehensive repository of national VHA data containing demographic, clinical, enrollment, financial, administrative, and treatment utilization data. Additional suicide attempts were identified using the Suicide Prevention Application (SPAN) database. Suicide Prevention Coordinators (SPCs) stationed across all VHA healthcare systems use a standardized process and report system to track suicide attempts by veterans. SPAN comprises the compiled reports of the suicide events identified by the SPCs.

Variables

Suicide attempts

As recommended in a study of SPAN (Hoffmire et al., Reference Hoffmire, Stephens, Morley, Thompson, Kemp and Bossarte2016), identified suicide attempts were maximized by combining those identified in SPAN with those in the CDW. Suicide attempts were identified in the 365 days following the index visit. Medical record attempts in the CDW were identified using the International Classification of Disease-9th Edition Clinical Modification (ICD-9CM) (Buck, Reference Buck2013) codes EE950-EE959. SPAN-identified suicide attempts used the self-directed violence subclass system: (1) suicide attempt; without injury, (2) suicide attempt; without injury; interrupted by self/other, (3) suicide attempt; with injury, and (4) suicide attempt; with injury; interrupted by self/other.

Opioid use disorders

Opioid use disorders included diagnostic codes indicative of both opioid abuse and opioid dependence as the following ICD-9CM codes were used: 304.00-3, 304.70-3, and 305.50-3.

Psychiatric disorders

We extracted ICD-9CM diagnostic information from the year prior to the index visit on depression, alcohol use disorder, PTSD, anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorder.

Covariates

We controlled for other key covariates including demographics (sex: male/female), opioid prescriptions filled, and medical comorbidity. Prescription opioids filled included butorphanol, codeine, fentanyl, hydrocodone, hydromorphone, meperidine, morphine, oxycodone, oxymorphone, and methadone if the dispense instructions included the word ‘pain.’ Medical comorbidity was accounted for using the Gagne Index (Gagne et al., Reference Gagne, Glynn, Avorn, Levin and Schneeweiss2011), which is based on 17 conditions identified using ICD-9CM diagnostic codes. We modified the index to exclude alcohol use disorders given that it was already included in the analyses.

Statistical analyses

Frequencies, means, and standard deviations were calculated to describe the sample. The risk for suicide attempts among veterans seeking pain care was examined using the Cox proportional hazard regression model. Unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models were conducted to assess bivariate associations between suicide attempts in the year following the index visit with OUDs, individual groups of psychiatric disorders (depression, alcohol use disorders, PTSD, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder). The adjusted model tested two-way interaction between OUDs and the five psychiatric disorders mentioned above. Multiplicative and additive interactions were surveyed through the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) methods (Li and Chambless, Reference Li and Chambless2007). We also report on the attributable proportion due to the interaction, which is an indicator of the percentage of participants whose suicide attempt was attributable to the interaction of the comorbidity. Risk time started following the index visit, which was the first pain care encounter and ended either at the date of their suicide attempt, date of death, or a year following their index visit. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to account for the potential differences in identifying suicide attempts through SPAN and medical record data by examining SPAN only attempts and found similar results. All computations were performed using SAS software, Version 9 (Cary, NC).

Results

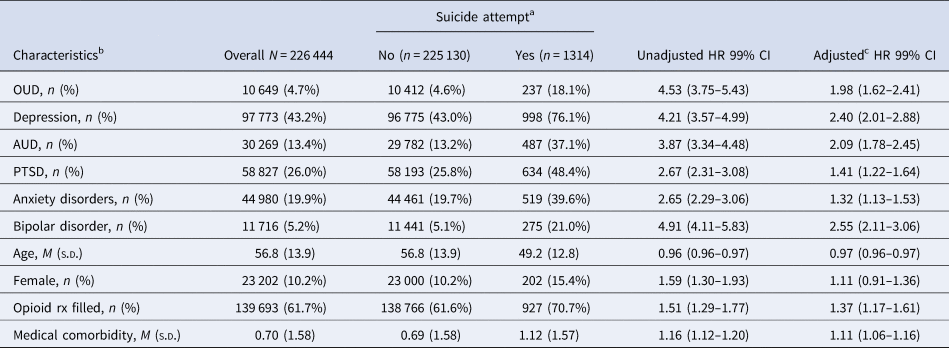

Overall, nearly 5% of the sample had a diagnosis of an OUD and 0.6% of the sample had a suicide attempt in the year following the index visit. Psychiatric disorder diagnoses were relatively high with over 40% with depression, over one-quarter with PTSD, 13% with alcohol use disorder, nearly 20% with an anxiety disorder, and over 5% with bipolar disorder (see Table 1 for additional sample characteristics). As depicted in Table 2, there were high levels of comorbid OUDs and psychiatric disorders. Over two-thirds of veterans with an OUD also had a depression diagnosis, while over one-third had comorbid alcohol use disorder, PTSD, or an anxiety disorder.

Table 1. Characteristics and hazard ratios of unadjusted and adjusted Cox regression models

AUD, alcohol use disorder; CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratios; OUD, opioid use disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder; Rx, prescription.

a Suicide attempt is for the year following the index visit.

b Diagnostic characteristics are based on the past year.

c Each of the characteristics was included in the adjusted analyses.

Table 2. Prevalence and unadjusted hazard ratios of opioid use disorder and comorbid psychiatric disorders and suicide attempts

AUD, alcohol use disorder; CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratios; OUD, opioid use disorder; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

a Suicide attempt is for the year following the index visit.

b Diagnostic characteristics are based on the past year.

c Among those with an opioid use disorder.

Unadjusted analyses revealed that OUDs (hazard ratios [HR] = 4.54, 99% confidence interval [CI] = 3.77–5.45) and each of the psychiatric disorders (e.g. HRDepression = 4.21, 99% CI = 3.56–4.97) were significantly associated with suicide attempts in the year following the index visit (see unadjusted HR column in Table 1).

In adjusted multiplicative interaction models (see Table 3), only comorbid OUD and bipolar disorder were significantly associated with suicide attempts; however, this association was protective (HR = 0.54, 99% CI = 0.35–0.82). In the additive interaction models, both comorbid OUD and depression (RERI = 1.07, 99% CI = 0.33–2.11) and comorbid OUD and AUD (RERI = 1.23, 99% CI = 0.42–2.05) were significantly associated with additive risk of suicide attempt. This indicates that the combined effect of OUD and depression is 7% more than the sum of the individual effects and the combined effect of OUD and AUD is 26% more than the sum of the individual effects. We found that 29% of the people attempting suicide with comorbid OUD and AUD is attributable to the additive interaction (AP = 0.29, 99% CI = 0.12–0.47). There was no significant additive interaction for bipolar disorder, PTSD, or anxiety disorders (see Table 3).

Table 3. Multiplicative and additive interactions for comorbid opioid use disorders (OUD) and psychiatric disorders

AP, Attributable proportion; AUD, alcohol use disorder; CI, confidence intervals; HR, hazard ratios; RERI, relative excess risk due to interaction; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

a Diagnostic characteristics are based on the past year.

b Models adjusted for gender, age, medical comorbidity, opioid prescriptions filled, OUD, depression, AUD, PTSD, anxiety disorders, and bipolar disorder.

c Relative risk ratios.

Supplemental analyses

Given our finding that comorbid OUD and bipolar disorder was protective of suicide attempt, we sought to help explain the findings. We hypothesized that veterans with comorbid OUD and bipolar disorder represent a very high-risk group and may be engaged in treatment, thereby serving to protect from suicide attempts. When examining the number of mental health visits in the previous year, we found those with bipolar and OUD had a mean of 16 mental health visits in the year prior to the index visit compared to just three in the remaining cohort. However, when including mental health visits in the model, comorbid bipolar disorder and OUD remained significantly protective of suicide attempts.

Discussion

The primary aim of the current study was to assess the effect of comorbid OUD and individual psychiatric disorders on suicide attempts among a large cohort of veterans seeking pain care. As expected, we found that there was an enhanced risk of suicide attempt across comorbidities in unadjusted analyses; however, comorbid OUD and depression and comorbid OUD and AUD were the only comorbidities demonstrating additive risk.

Depression is a robust risk factor of suicidal behavior (Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Suicide Prevention, 2018) and is associated with opioid use among people experiencing chronic pain (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2018). One potential explanation for the additive effects is supported by research finding many people high-risk patients with depression receive high-dose long-term opioid therapy (Braden et al., Reference Braden, Sullivan, Ray, Saunders, Merril, Silverberg, Rutter, Weisner, Banta-Green, Campbell and Von Korff2009). High-dose, long-term supply provides access to means to attempt suicide (Klonsky and May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). Furthermore, the endogenous opioid system is involved in both depression and chronic pain and opioids may be used to compensate for the reduced endogenous opioid response (Sullivan, Reference Sullivan2018). Research supports that changes in neurocircuitry induced by prolonged opioid use drives a need beyond pain relief thereby producing negative affective states (Shurman et al., Reference Shurman, Koob and Gutstein2010). Prolonged negative affective states with a blunted response to pleasurable cues may leave individuals vulnerable to attempting suicide (Elman et al., Reference Elman, Borsook and Volkow2013).

Comorbid OUD and AUD also had an additive risk for a suicide attempt. Our findings are consistent with previous research indicating that individuals with an OUD and a suicide attempt may be more likely to be using alcohol than individuals with an OUD and no suicide attempt (Maloney et al., Reference Maloney, Degenhardt, Darke, Mattick and Nelson2007). The combination of opioids and alcohol can have significant sedating effects and may be used in combination to attempt suicide (Klonsky and May, Reference Klonsky and May2015). When considered in the context of a conceptual model of substance use disorder and suicidal behavior (Conner and Ilgen, Reference Conner, Ilgen, O'Connor and Pirkis2016), a comorbid substance use disorder is a marker for increased severity that can produce aggression and impulsivity, negative affect and depressive episodes, and interpersonal conflict that increase the likelihood to attempt suicide.

We found that comorbid bipolar disorder and OUD was protective in multiplicative models. It is unlikely that this comorbidity actually decreases the risk of suicide attempts, so we looked at other factors that may have helped produce these findings. One possibility is that these veterans are more likely to be receiving treatment because of the combination of two high-risk problems (Blanco et al., Reference Blanco, Miran, Schwartz, Rafful, Wang and Olfson2013; Painter et al., Reference Painter, Brignone, Gilmore, Lehavot, Fargo, Suo, Simpson, Carter, Blais and Gundlapalli2018), and therefore, are at decreased risk of a suicide attempt. Although we found that veterans with this comorbidity had a higher number of mental health visits, the protective association remained significant. This may have been the result of having a relatively small number of people with comorbid bipolar disorder and OUD. Additional research is needed to further understand what factors may be contributing to reduced risk of suicide attempt among veterans with comorbid bipolar disorder and OUD.

One potential explanation for the non-significant effects for the other disorders is they (e.g. PTSD, anxiety disorders) are highly comorbid with depression, which drives the association with suicide attempts. Another possibility is that there are transdiagnostic features of functioning that affect suicide attempt risk (Braden et al., Reference Braden, Sullivan, Ray, Saunders, Merril, Silverberg, Rutter, Weisner, Banta-Green, Campbell and Von Korff2009; Nock et al., Reference Nock, Hwang, Sampson and Kessler2010). For example, a recent meta-analysis found that several transdiagnostic systems including arousal and regulation systems (e.g. sleep disturbance), cognitive systems (e.g. biased attention toward negative cues), negative valence systems (e.g. loss, sustained threat), and social processes (e.g. social withdrawal) are each significantly prospectively associated with suicide attempts (Glenn et al., Reference Glenn, Kleiman, Cha, Deming, Franklin and Nock2018).

There are several limitations that should be considered in the context of the current findings. All diagnoses were restricted to those identified in the electronic medical record, rather than structured diagnostic interviews. As such, it is unclear about the accuracy of the diagnoses and some undiagnosed disorders may have been missed. Additionally, suicide attempts identified in SPAN and CDW only capture those attempts known to the VHA leading to a potential for underreporting. Diagnostic data in the year following the index visit. It also would have also been helpful to assess in incident psychiatric disorder diagnoses in the year following the index visit was associated with suicide attempts. Nonetheless, these limitations are balanced by strengths including medical record data and suicide surveillance data for over 200 000 veterans. Identifying suicide attempts through SPAN and CDW also averts concerns about self-report biases about suicide attempts while capturing more attempts than either of these datasets alone. Additionally, we included opioid analgesic prescriptions filled in the models to account for the potential that opioid therapy was associated with subsequent suicide attempts.

This study highlights the importance of being able to address comorbidities to mitigate suicide risk. For AUDs, naltrexone may be a potential solution as it is used to treat both alcohol cravings and opioid use. Naltrexone is greatly underutilized in the VHA (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Oliva, Bowe, Humphreys, Kivlahan and Trafton2012) and future research could prospectively assess the potential impact of using naltrexone to address comorbid opioid and alcohol use disorders and suicide risk. Naltrexone was found to reduce all-cause mortality in veterans (Harris et al., Reference Harris, Bowe, Del Re, Finlay, Oliva, Myrick and Rubinsky2015). A meta-analysis for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) found that naltrexone prevents premature death among persons with OUD (Ma et al., Reference Ma, Bao, Wang, Su, Liu, Li, Degenhardt, Farrell, Blow, Ilgen, Shi and Lu2018). Overall, MAT is underutilized in the VHA (Oliva et al., Reference Oliva, Harris, Trafton and Gordon2012), but provides the potential to decrease opioid use, while providing analgesic effects in case of methadone and buprenorphine (Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain Work Group, 2017).

There are numerous additional avenues for future work in this area. Research could examine these effects in VHA users as a whole, rather than only those receiving specialty pain treatment. Given that this sample was among a more medically and psychiatrically complex sample, the results may differ from a broader cohort. Larger cohort size may also be useful when assessing potential three-way interactions for effects of multi-morbidities (e.g. depression, OUD, AUD). Suicide death data would also provide a meaningful expansion to this work. It would also be interesting to assess if engagement in non-pharmacological pain treatments helps protect against suicide attempts in comorbidities that conferred additive risk.

Given that this was among patients initiating pain services, to the extent which pain is driving opioid use (Lipari et al., Reference Lipari, Williams and Van Horn2017), non-pharmacological options that address both pain and other mental health problems (e.g. cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain in substance use disorder patients; mindfulness-based interventions) may also be of use (Garland et al., Reference Garland, Manusov, Froeliger, Kelly, Williams and Howard2014; Ilgen et al., Reference Ilgen, Bohnert, Chermack, Conran, Jannausch, Trafton and Blow2016). Similarly, suicide safety planning could incorporate strategies to address suicide risk-related factors associated with depression, alcohol use, and opioid use as appropriate. In veterans presenting the emergency department with suicide risk, safety planning plus follow-up has been shown to be associated with a 45% reduction in risk for suicide attempts (Stanley et al., Reference Stanley, Brown, Brenner, Galfalvy, Currier, Knox, Chaudhury, Bush and Green2018). It is possible that implementation of safety planning among patients receiving treatment for opioids may confer protection, which is critical due to their access to potentially lethal means. The findings again support the use of interdisciplinary teams within specialty pain care to address the unique needs of veterans with comorbid substance use disorders, and suicide risk. For example, stakeholders in behavioral health, substance use disorders, and pain care will be better equipped to address the complex nature of the comorbidity and suicide risk.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Cathy Kane for assistance with data management. This work did not receive any external funding. The content of this publication does not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs, the United States government, or the academic affiliate.

Financial support

This study did not receive any external funding.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.