The widely held view of the fascist regimes in Germany and Italy as pagan or even anti-Christian—promulgated not least by the Catholic and Protestant churches—has been the subject of much controversy in recent scholarship. Supporters of this view stress the frequent assaults by the two regimes on the churches and the persecution and resistance of many clerics.Footnote 1 They also point to the discrepancies between Christian doctrine and fascist ideologies, juxtaposing the gospels’ teaching of the equality of all human beings with the racism of fascist propaganda and policy. On the delicate issue of the origin of the Holocaust in particular, the Vatican has drawn a clear distinction between historic Christian “anti-Judaism,” based on religious differences, and the “modern,” racial anti-Semitism espoused by the fascists.Footnote 2

A large and growing body of scholarship has cast doubt on these arguments. Many Catholic priests and Protestant ministers actively supported the fascist regimes, while others were simply complacent or, in the words of Spicer, put up “quiet resistance.”Footnote 3 The churches remained silent about many fascist crimes and hence were, some scholars argue, complicit.Footnote 4 The ascent of the fascist movements to power put the churches and individual clerics in a difficult position. Their responses often reflected their ambivalent attitude toward the new regimes.Footnote 5 In a bid to stabilize their hold on power, these regimes frequently worked together with church leaders. In fact, during some periods the Vatican's relationship with Hitler's and, especially, Mussolini's government was far from hostile.Footnote 6

If many clerics found fascism compatible with their Christian beliefs, so too did many fascists believe themselves to be good Christians. Steigmann-Gall's The Holy Reich initiated an intense debate over his claim that Nazism was in many ways a Christian movement since many members of the Nazi elite promoted “positive Christianity,” an Aryanized form of the faith.Footnote 7 In his view, in addition to paganism, “positive Christianity […] expressed bona fide religious feelings” in the Nazi Party, and “Professions of Christian feeling were not the product of Nazi mendacity.”Footnote 8 Similarly, Williamson argues that many high-ranking party members and supporters sincerely thought of themselves as good Christians.Footnote 9 Other scholars, too, point out the close link between Nazi ideology and German Protestant culture in particular. Thus, Bergen shows the important role of the Deutsche Christen (German Christians), a völkisch organization that originated in the Protestant churches, in supporting the regime. Its goal was to fuse the Nazi movement and the Protestant churches by purging all Jewish influences from the latter.Footnote 10 Hastings, by contrast, contends that the embrace of positive Christianity by the early Nazi movement derived from its roots in the Catholic milieu of Munich.Footnote 11

Moreover, many scholars argue that the distinction between premodern anti-Judaism and modern racial anti-Semitism is spurious. Just as the churches promoted “modern” anti-Semitic themes along the lines of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion well into the twentieth century, the fascist regimes made ample use of premodern Christian tropes in their efforts to whip up hatred against the Jews.Footnote 12 Indeed, the Nazis found fertile ground for their ideas in Christian communities beyond the German Christians, which led Bergen to argue that Christian anti-Semitism was a crucial factor in making the Holocaust possible.Footnote 13 According to Probst, Protestant scholars and clerics, including many who belonged to the Confessional Church that opposed the Nazis, “reinforced the cultural anti-Semitism and anti-Judaism of many Protestants in Nazi Germany.”Footnote 14 Heschel's study of the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life reveals the explicit propaganda efforts among Protestant theologians to link anti-Judaism and Nazi anti-Semitism by “Aryanizing” Jesus.Footnote 15

Beyond the well-documented use of anti-Jewish Christian tropes, what is largely missing from these debates is examination of how the fascist regimes themselves made use of Christianity in demonizing the Jews. Exploring this question promises to shed further light on the issues of whether these regimes were openly anti-Christian or, to the contrary, cast themselves as the defenders of a Christian Europe, and whether, in doing the latter, they supported or criticized contemporary Christian clergy. In principle, the Nazi and Italian Fascist anti-Semitic campaigns should be crucial supporting evidence for those who argue that a distinction needs to be made between traditional Christian anti-Judaism and the racial anti-Semitism of secular fascist ideology. If “scientific” racism put the fascist regimes and the Christian Churches at loggerheads, these campaigns were prime opportunities for fascist attacks on Christian doctrine and clergy. At the very least, one would expect fascist propaganda to gloss over such differences with Christian dogma out of consideration for widespread Christian sensibilities. By contrast, an explicitly Christian justification in fascist propaganda for the vilification of the Jews provides further evidence for the argument that the proposed divide between religious anti-Judaism and secular anti-Semitism is untenable.

As we shall see, the way that the fascist regimes depicted Christianity and the Christian Churches in demonizing the Jews also has important implications for ongoing debates about fascism as a “political religion.” Were the Fascists and Nazis building an alternative religion, competing with the Christian faiths, or were they engaged in some kind of new church-regime collaboration, one in which the Christian churches continued to play a significant role?

In examining these issues, we provide a comparative analysis of anti-Semitic propaganda in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. Most of the scholarly contributions referred to above draw their findings from investigation into only one of the two regimes, with most attention paid to the German case. A comparative approach helps correct this imbalance and allows us to identify patterns of similarity and difference between the two. This, in turn, serves as a partial corrective to the twin pitfalls of over- and undergeneralization which often mar single-country studies. Such comparison promises to yield new insight into church-regime relations in Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. While these relations were fraught with difficulties in both countries, the German case was particularly complicated due to the existence of two major Christian confessions and increasing fragmentation on the Protestant side.

TOOLS OF PROPAGANDA: LA DIFESA DELLA RAZZA AND DER STÜRMER

To compare the use of Christianity in Nazi and Fascist demonization of the Jews, we examine the foremost anti-Semitic propaganda vehicle in each regime: La difesa della razza in Italy and Der Stürmer in Germany. Both periodicals circulated widely and enjoyed the direct support of their respective regimes. The Italian magazine served as the Fascist regime's official organ in its anti-Semitic campaign. The German weekly, although privately owned and run, had a privileged status in the Nazis’ anti-Semitic propaganda machine.

The introduction of the racial laws in September 1938 marked a startling new development in the Italian Fascist regime's policies. While Hitler had initiated anti-Jewish measures almost immediately upon taking power more than five years earlier, in Italy no such measures had been introduced. Indeed, a considerable portion of Italy's Jews took out memberships in the Fascist Party.Footnote 16 It was in the wake of Hitler's visit to Italy in May 1938 that the Duce, keen to impress his German allies, decided to turn against the Jews.Footnote 17 At the time, Italy's Jewish population was largely concentrated in a few urban centers and amounted to only one-tenth of 1 percent of the population (fewer than fifty thousand), compared to Germany, where Jews were about 1 percent of the population (roughly a half-million).

To convince the Italians of the need for action against their Jewish fellow citizens, Mussolini initiated a massive propaganda campaign. It started in mid-July 1938 with the Manifesto of Racial Scientists, prepared at Mussolini's direction, and published with great fanfare in the country's major newspapers. The manifesto proclaimed the existence of a pure Italian race and deemed the country's Jews a separate, noxious, foreign race. Exhorting Italians to be openly racist, the manifesto asserted that the Duce had in fact championed racism all along.

For Mussolini, it was important to launch an illustrated magazine with a popular touch to instill the new racial theories in the minds of ordinary Italians. Under his supervision, the Ministry of Popular Culture, which was responsible for the regime's propaganda, recruited a group of Fascist academics for the magazine's editorial committee, including some of the manifesto's signatories and its principal author, the young anthropologist Guido Landra.Footnote 18 Mussolini appointed as editor the prominent Fascist journalist and fierce anti-Semite Telesio Interlandi. Titled La difesa della razza (The defense of the race), the magazine was published under the authority of the ministry, which sent copies of each issue to schools and universities throughout Italy. Publication started in August 1938 and two new issues appeared each month until shortly before Mussolini was ousted in July 1943.Footnote 19

By contrast, Der Stürmer (The stormer) was not published directly by the National Socialist regime but was owned and edited by Julius Streicher, one of Hitler's most loyal followers since the early days of the Nazi movement in Munich. In 1923, Streicher launched Der Stürmer as a regional weekly newspaper in Nuremberg. Its subtitle proclaimed it to be “a weekly for the fight for the truth.” The truth was, as readers would learn week after week, that the German Volk were in a life-or-death struggle with the world's foremost enemy, Alljuda (pan-Jewry).

With Hitler's rise to power in January 1933, Der Stürmer evolved into a national paper and its circulation skyrocketed. The propaganda vehicle became a fixture of everyday life under the Nazi regime as, throughout the Reich, notice boards called “Stürmer boxes” were set up in central spots of even small towns, where each new issue could be read for free. These boxes were often elaborately decorated and sported the paper's signature slogans such as, “Those who buy at the Jew's betray their Volk,” or “The Jews are our misfortune!” Moreover, Streicher managed to reach an agreement with the German Labor Front—the Nazi labor organization that had replaced independent trade unions—which obliged most German businesses to acquire a quantity of copies in proportion to the size of their work force.

Exploiting anti-Jewish tropes of all kinds in the most extreme manner, Der Stürmer shaped the way many Germans saw the Jews living in their midst. This was particularly true for how Jews came to be depicted visually during the Nazi years. In his weekly cartoons, the paper's illustrator Philipp Ruprecht, under his pen name “Fips,” created the proverbial Stürmerjude, with his crooked nose, bulging eyes, and flat feet. The paper's vulgarity and recklessness attracted criticism even from other Nazis, who sought to put the regime's brand of anti-Semitism on a more “scientific” footing, yet all attempts to shut it down failed. Streicher was Hitler's personal protégé and his privileged status allowed him to pursue his propaganda crusade against the Jews with unrestrained ferocity.

In 1934, Streicher became the regional Nazi Party leader in Franconia (Northern Bavaria) and was widely known as the Frankenführer (Leader of the Franconians, in analogy to Hitler). His standing in the party later declined, and he lost all his party posts in 1940. On Hitler's direct order, however, he was allowed to keep his ownership and editorship of Der Stürmer, which by then had made him wealthy. The weekly's final issue was published in early 1945, only months before the Allies reached Berlin. The tribunal at Nuremberg declared Streicher to be “Jew-Baiter Number One” and sentenced him to death for crimes against humanity, pointing to his paper's critical role in fomenting hatred against the Jews and paving the way for the Holocaust: “In his speeches and articles, week after week, month after month, he infected the German mind with the virus of anti-Semitism, and incited the German people to active persecution.”Footnote 20

La difesa della razza

In Italy, the Roman Catholic Church had long been the major font of anti-Semitism. Unlike many other European countries, where nationalism and anti-Semitism were often conjoined, this was not the case in Italy. From the time modern anti-Semitism emerged in the last two decades of the nineteenth century, Church publications were the most consistent purveyors of its themes.Footnote 21

The announcement of Mussolini's new “racial” doctrine in July 1938, with its claim that there was a pure Italian race consisting entirely of Christians, with Jews forming a separate, lesser race, surprised many Italians. Pope Pius XI, although old and frail, expressed his disapproval of Mussolini's attempts to imitate the Nazis. The clerics around the pope, worried that the Church's mutually beneficial alliance with Mussolini might be in jeopardy, worked frantically to reign him in, but he remained unhappy with the Fascist government's embrace of Nazi Germany and its racism.Footnote 22

In this context, Fascist attempts to justify their anti-Semitic campaign by reference to the Church's long history of demonization of the Jews became central to their effort to win popular support. The risk of having the campaign denounced by the pope was ended on Pius XI's death in February of 1939 and the election of his successor, Pius XII, who would never publicly criticize Italy's anti-Semitic policies. Nevertheless, the Fascists still needed to win popular support for the campaign, which baffled many Italians.

As the main Fascist vehicle for whipping up popular support for the racial laws and the anti-Semitic campaign, La difesa della razza shows how regularly the regime invoked Church authority in these efforts. That said, there were signs early on that the Holy See was not entirely pleased with the journal. Shortly after the first issue appeared, the Vatican daily newspaper, L'Osservatore romano (15 Sept. 1938), published a brief, critical story about it. Bonifacio Pignatti, the Italian ambassador to the Holy See, immediately went to complain to the Vatican Secretary of State, Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli. As Pignatti reported to Italian foreign minister Galeazzo Ciano, on 16 September, Pacelli—soon to succeed Pius XI as Pius XII—downplayed the criticism. He attributed the critical remarks to L'Osservatore romano's editor, whom he deemed a loose cannon.Footnote 23 Yet Pius XI had made the Church's universal mission clear and fiercely opposed the Nazi doctrine of a racial hierarchy. In part for this reason, in instituting its anti-Semitic campaign the Italian Fascist authorities went to great lengths to claim that they were not copying the Nazis but building on a long Italian tradition of defending Catholic Italy from the perfidious Jews.Footnote 24

In fact, the portrayal of the Jewish threat found in La difesa consisted in good part of a marriage of the kinds of anti-Semitic portraits painted in the Italian Catholic press over the previous several decades with pseudoscientific claptrap authored by Italian university professors of anthropology, biology, and demography. The main arguments used in demonizing the Jews—the Jews were taught by the Talmud to hate and persecute Christians, the Jews were the secret conspirators behind capitalism and communism, et cetera—were arguments that had long been promulgated by Civiltà cattolica, the Rome-based, Vatican-overseen Jesuit biweekly. La difesa's very first issue contained an article devoted to Civiltà cattolica's anti-Semitic polemics, which concluded, “There is no incompatibility between the doctrine of the Church and racism, as it has been expressed in Italy.”Footnote 25

So rich was the store of anti-Semitic venom in Civiltà cattolica from which La difesa could draw that the magazine devoted yet another article to it in its third issue. The author quoted from the pages of the Jesuit journal: “As for anti-Semitism, it did not derive … from religious persecution.” Rather, the measures against the Jews “derived instead from the intolerable pressure that they exercised over the people who hosted them with their intrusiveness and their usury.” The Difesa article went on to quote Civiltà cattolica in castigating the Jews for their efforts to take over the societies in which they lived, to dominate their economies, acquire their newspapers, and practice fraud, criminality, and thievery. The lengthy article was accompanied by a caricature of Soviet Jews trampling sacred Catholic images.Footnote 26

Such was the profusion of religious images in La difesa that even a person unable to read could quickly grasp the extent to which the publication used the Church to justify the need to act against the Jewish threat. Its pages were littered with Church images, dozens of them. The many articles on the popes’ and saints’ campaigns against the Jews carried iconic images of the popes and saints. Other articles, while not directly about the evil of the Jews, had the apparent goal of convincing readers of the Catholic nature of the publication. Hence an article on “Family and racial policy” was decorated with a painting of the Madonna and baby Jesus, and the same issue also reproduced a painting by Raffaelo of Saint Cecilia looking heavenward. Two weeks later, La difesa carried a story on “Mothers and children in Italian art,” featuring yet another painting of the Madonna and baby Jesus, this one by Caravaggio.Footnote 27

La difesa's efforts to identify Italy's racial laws with the popes began in its fourth issue, with an article titled “The popes and Jewish doctors.” It explained, “The art of medicine was cultivated throughout the ages as a preferred choice by the Jews: not out of any spirit of sacrifice or sense of mission, but for ease of making money.” The author then chronicled a long list of church councils, dating back to the thirteenth century, aimed at barring Jews from practicing medicine on Christians. In a titillating detail, he asserted that a Jewish doctor of Pope Innocent VIII (1484–1492) wanted to treat the dying Pontiff with “the blood extracted from three boys around ten years old, murdered for the purpose,” but “the Pope rejected such an abominable proposal, and the evil doctor fled.” Following a review of the anti-Jewish orders of several popes of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the article concluded: “Today, after so many centuries, Fascism is reexamining the ‘vexed Jewish question’ and is resolving it not with compromises but with totalitarian, fascist methods.”Footnote 28

Articles over the following years continued to justify the Italian racial laws as simply following the practices that earlier popes had put into place in protecting Italian Christian society. Under the rubric “The sources of Italian anti-Judaism,” La difesa ran a story on Pope Paul IV, the pope who first ghettoized the Jews of the Papal States. The first page offered a large image of his funeral monument that depicts him sitting on his throne. “In that tomb,” the article explained, “lie the remains of Paul IV Carafa, whose legislative work was fundamental for the protection of civilization against the Jewish menace.” Several issues later, an article explained that his successor, Pope Pius V, “was forced to issue a third papal bull against the Jews, fully revealing, with caustic words, their malice and the harassments and dangers with which the people of the Papal States have been oppressed at their hands.” The same issue, in an article titled “The eternal enemies of Rome,” reminded readers that in 1215 Pope Innocent III had “among other measures taken against the Jews,” ordered that they be made to wear a sign on their clothes so that they could be easily recognized. “Observing the history of the Church,” the author of a 1941 article on Jews in the Papal States wrote, “one can note with what great persistent vigilance it sought to exclude the Jewish element from its bosom, contributing with the implacable work of the vicars of Christ to forming not only our Roman Catholic conscience, but also, as a corollary of this, our anti-Jewish conscience.”Footnote 29

That the divide between “racial” and “religious” demonization of the Jews was elided in the pages of La difesa is also clear from the way the publication used Christian imagery. One of its first issues took up the subject of Judas's betrayal of Jesus, a theme that would reappear often. The article, “The Jew in art,” bore the ponderous subtitle, “The hateful face of Israel is distinguished everywhere from the features of Italians. In the pictures of our painters as in the crannies of the ghetto the features of Judas spark aversion and disgust.” Four Christian images were offered in support of this racial distinction, three of them well-known artists’ depictions of Judas, along with an image known simply as “The Jew,” from a Catholic devotional complex in northern Italy.Footnote 30

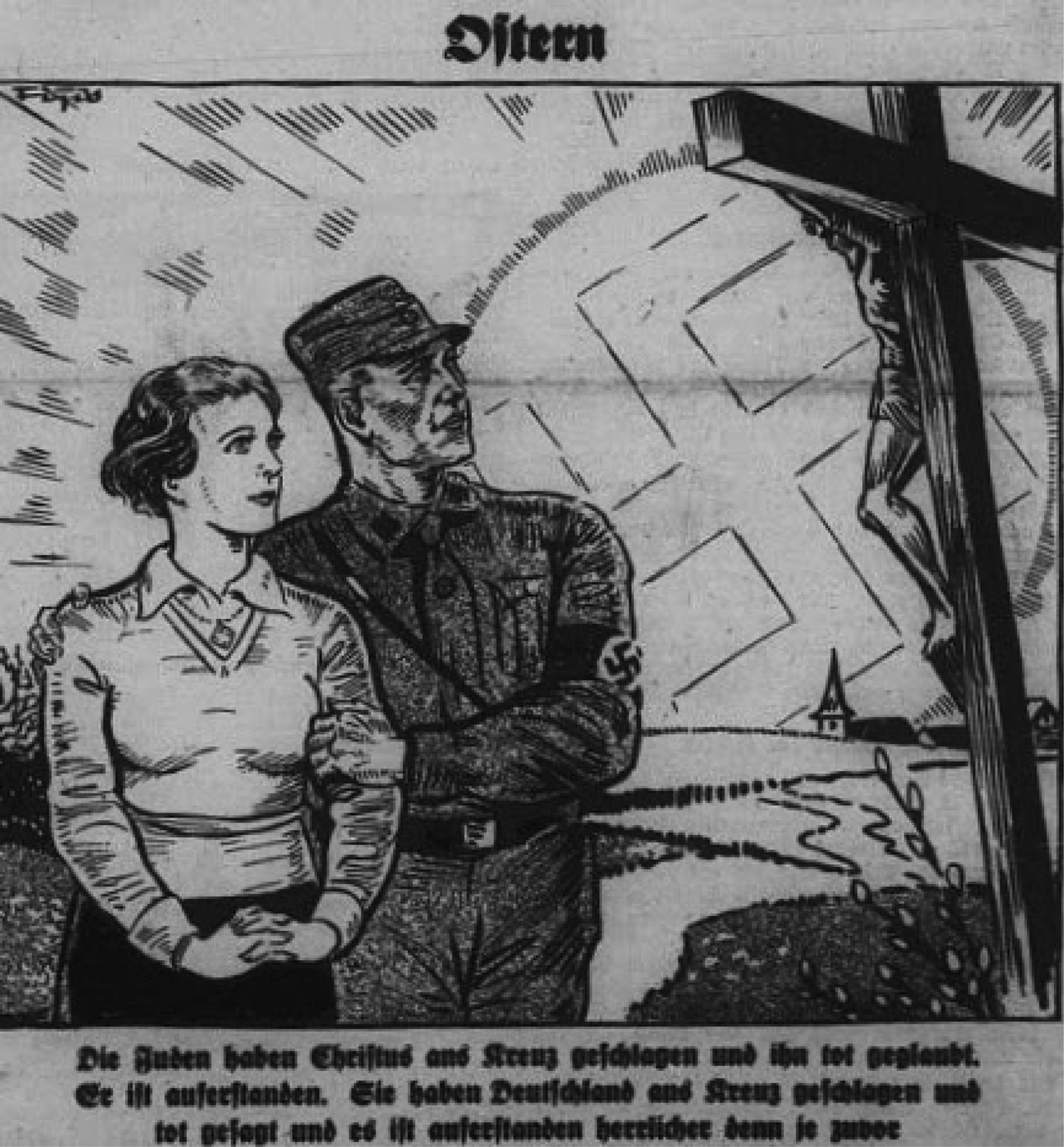

The following year, La difesa returned to the theme of Judas as the archetypical treasonous Jew. One article featured an image of a section of Giotto's fresco in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua showing Judas collecting his bag of gold for his betrayal, and another later in the year showed a second image from Giotto's frescoes depicting “Judas's kiss.” A year later, in 1940, two images of Judas, one labelled “Judas and Christ,” and the other “Judas in the Last Supper by Andrea del Castagno,” accompanied one article, while an article later that year republished Giotto's fresco of Judas's kiss. Nothing, however, demonstrates the elision between race and religion in the use of the Judas imagery better than the story carried in the last issue of La difesa, of 1941, titled “Judas the Jew: Judas Negroid.” It included four different religious depictions of Judas kissing Jesus and minutely examined Judas's features to show that he belonged to an inferior race (see Image 1).Footnote 31

Image 1. The Kiss of Judas (detail). Fresco by Giotto in the Cappella degli Scrovegni, Padua (La difesa della razza 2, 20 [20 Aug. 1939]: 47; Brown University Library).

One characteristic of the centuries-long Christian demonization of the Jews was the attention given to the Talmud as a font of Jewish evil. It proved a useful tool for reconciling the recognition that Jesus and his disciples were Jewish with the desire to characterize Jews as evil by nature. Hence, while the Jews of the Hebrew Bible were God's chosen people, by rejecting Jesus and then embracing the Talmud (a work dating to a time after the Christian sect had diverged from its Jewish roots), the Jews turned away from God and set out on their evil ways.Footnote 32

La difesa devoted an article to this theme in one of its first issues, titled simply “Talmud.” “Beginning in 1239 and until 1320, Gregory IX and other popes,” the article recounted, “ordered that it be burned. In the second half of the sixteenth century, the Talmud was burned six times…. Julius III issued a curse against the Talmud in 1553 and in 1555; Paul IV in 1559; Pius V in 1566; Clement VIII in 1592 and 1599.” La difesa's next issue continued the story, one article telling how an abbot in 1826 sent the pope a copy of his book that revealed the hidden secrets of the Talmud. A second article in that issue focused on the Talmud as well, claiming that it instructed Jews to despise Christians and have them do all the work for them. Although no sources are given, the style of the piece, with a large number of presumed quotes from the Talmud, shows all the signs of having been lifted from earlier Catholic sources.Footnote 33

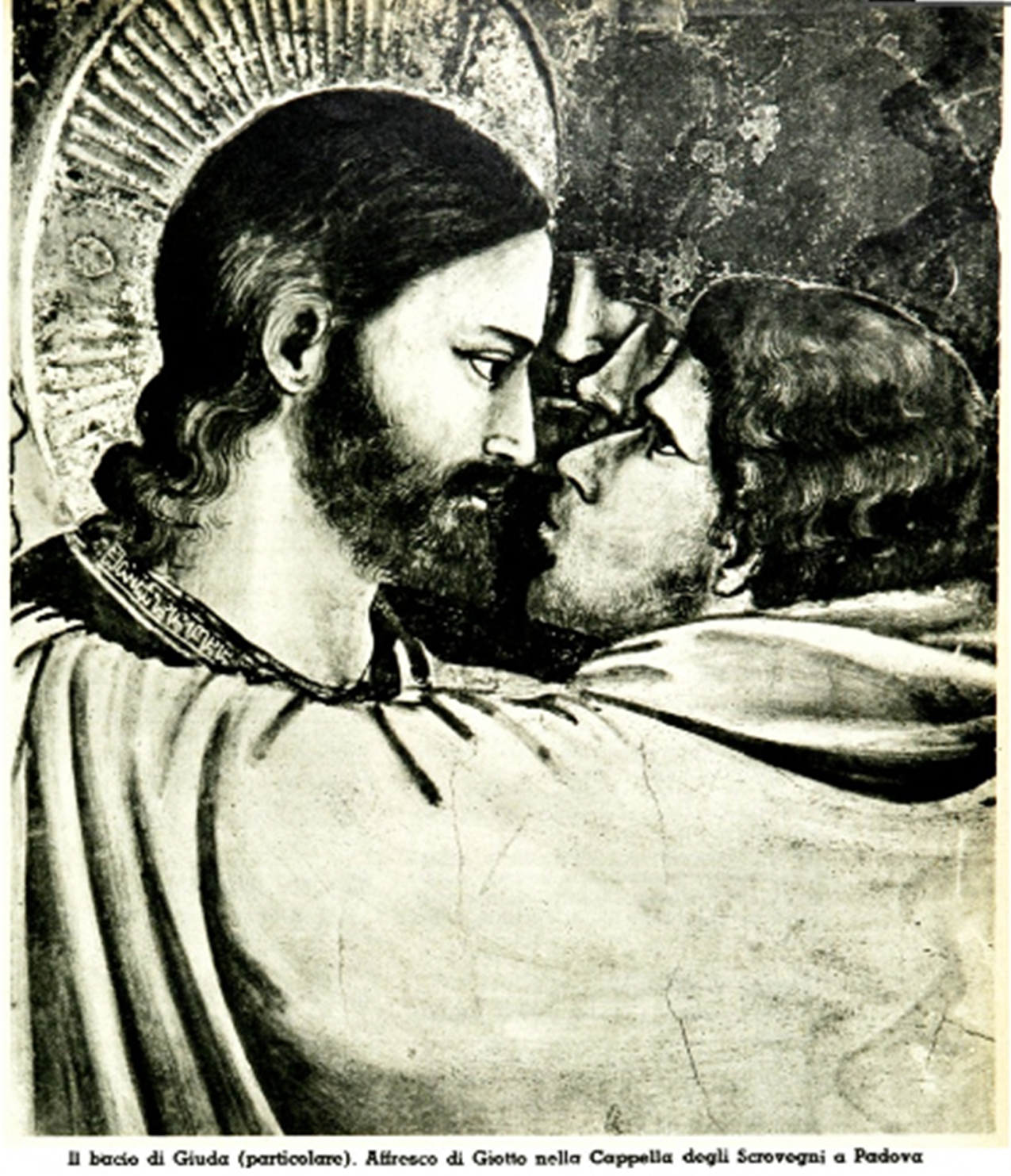

In its second year of publication La difesa continued to hammer on the theme of the Talmud as the source of Jewish evil, again wrapping its campaign against the Jews in the mantle of the Catholic Church. In a 1939 article titled “Christ and Christians in the Talmud,” the journal asserted that the Talmud instructed Jews to hate and oppress Christians. Giving the theme special weight, the subtitle promised the “imminent publication” of a book devoted to the subject, to be published by La difesa itself. In this same issue La difesa republished an article by the prominent nineteenth-century French Catholic journalist, Louis Veuillot, “How the Jews view the non-Jewish woman.”Footnote 34 It purported to reveal the Talmudic instruction that Jewish men were to regard Christian women as beasts. “They give the goyim the status of the donkey and the pig.” Lest the sexual ramifications of this revelation be missed, each of the two pages of the article contained a drawing of a blonde woman tied up, one to a tree, the other in a pose of crucifixion on a star of David, as the evil figure of the Jewish man is poised to assault her. In the latter the Jew stands before an open book labeled “Talmud” (see Image 2).Footnote 35

Image 2. “We address the Nations who think they can escape persecutions: we who have always been the most implacable persecutors:—the Jew Samuel Roth” (La difesa della razza 2, 14 [20 May 1939]: 23; Brown University Library).

Also common in the pages of La difesa were stories about the various saintly figures of the church who warned of the danger posed by the Jews. Three different issues in 1939 recounted the anti-Jewish diatribes of the Blessed Bernardino of Feltre, whose haloed, robed, barefooted figure adorned the first of these stories. The monks of his order, wrote the author, “coordinated and directed a vast movement against the Jews, those ‘merchants of tears, drinkers of human blood.’” The next issue's follow-up story, “Usury, sacrilege and fraud and the ban on the Jews in the Papal States,” told how Bernardino “came in 1473 to urge the bolognesi to drive out the Jews.” Later that year, in an article titled “Saints of the Italian race. Bernardino da Feltre,” the author explained that “the Blessed Bernardino's desire, which was the same as that of the Church, was to isolate the Jews.” Over the next three years, articles were similarly devoted to the anti-Jewish campaigns of various other saints. “It is generally believed,” one asserted, “that, after his conversion, the apostle Saint Paul was the greatest tormentor of the Jews.”Footnote 36

The question of conversion was potentially a delicate subject for La difesa, because the Church's doctrinal position seemed clear: a Jew who was baptized should no longer be considered a Jew but rather a Catholic, a position in evident contradiction with a racial understanding of the difference between Jew and Christian. The subject was taken up in one of the journal's first issues, which assured its readers, “The Church knows that conversion will not change the Jew's membership in the people of Israel, knows that baptism changes the type of Jew as little as it does that of the Negro and knows, that from the ethnological and anthropological point of view, the Jew remains a Jew.”Footnote 37 Two years later, in 1940, the journal reiterated this view: “The Jew always remains a Jew, even if he changes his religious label. Indeed, the convert becomes even more Jewish than before….” Lest this be thought to be the view of someone outside the church, it is worth noting that its author's recent anti-Semitic book, Under Israel's Mask, had been positively reviewed by Civiltà cattolica. The one unacceptable point the author had made in that work, according to the Vatican-approved pages of the review, was the notion that the Jesuit journal had called only for “charity and conversions” in dealing with the Jewish threat, while the Civiltà cattolica reviewer insisted that, to the contrary, it had long urged governments to take steps to protect Christian society from the Jews.Footnote 38

Perhaps most effective in making the point was the cartoon published in La difesa's first issue of 1943. Titled “‘The Aryanized’ at Heaven's gates,” it showed a conversation between a haloed Saint Peter, holding the keys to heaven, and a hooked-nosed, bald Jew in fur-lined coat presenting him with a piece of paper with a cross on it:

“You can take me in without fear; here is my baptismal certificate.”

“Hmm! I believe that it has little value here!”

“Little value? … a piece of paper that cost me more than ten thousand francs!”Footnote 39

Among the other themes found throughout the pages of La difesa was the charge that the Jews were the enemies of the Catholic Church and had to be stopped lest they destroy it. Typical was an article in late 1938 titled “How the Jews tried to take possession of the Church's patrimony,” which told how Jews in the nineteenth century had sought to gain control of the agricultural properties of the Papal States. A few issues later, joining the themes of Jewish conversion and Jewish threats to the Church, La difesa recalled that when Sicily ordered the expulsion of all Jews in 1492 there had been a great rush to the baptismal font. And so, the journal recounted, “ninety thousand Jews found safety.” Yet they had duped the Church authorities, for “The Jews … have always been the declared and irreducible enemies of the Catholic Church.” The next issue returned to this theme, asserting that while Jews might be forced by circumstances to accept baptism, the Jew remained “the enemy of the Roman Church.” Telesio Interlandi dedicated several other articles over the next years to this theme, describing what a late-1942 article referred to as “the war in which, for twenty centuries, Judas has used all the means and resources possible to fight against the foundations of the Catholic message.”Footnote 40

Nor did La difesa fail to make regular use of the most medieval Christian charges against the Jews, with several articles devoted to the Jewish ritual murder of Christian children, along with one on the Jewish profanation of the Host. A name that stands out among the authors of these articles is Giorgio Almirante, who would later serve as longtime head of Italy's postwar neo-fascist party, the Movimento Sociale Italiano. One article he wrote featured an image of two women, one of whom holds up a cross. Its label reads: “These two Polish Jewish women … are caught by a German soldier in the act of mocking and profaning the symbol of Christ.” Almirante added, “Catholics and fascists might usefully reflect on this image: Rome has no other enemy in the world than Judaism.”Footnote 41

In one of La difesa's last issues, published as the Allies began to close in on Italy in the spring of 1943, the journal called for another moment of reflection. “But while today the war goes on,” the author, most likely Interlandi himself, concluded, “and one can expect the most barbarous acts by the enemy, incited by Judaism and aroused by the greed for gold, the Italian … knows that God is with him because He is with the best and God will keep him from ruin.” Beside this meditation is a large cartoon-figure of a skull-capped, bearded Jew, a knife clutched in one hand and in the other a revolver pointed straight at the reader.Footnote 42

Der Stürmer

Like La difesa, Der Stürmer offered itself as a stout defender of Christianity against its enemies, and regularly justified the state's anti-Jewish campaign by reference to Christian teachings. Yet, while La difesa wrapped itself in the mantle of the Roman Catholic Church, Der Stürmer had a more complicated relationship with the existing Christian denominations in Germany. In fact, the paper's owner and editor, Julius Streicher, like chief of propaganda Joseph Goebbels, was among the fiercest anti-clerics in the Nazi establishment.Footnote 43

Der Stürmer regularly argued that, far from seeing everyone as equal before God, Christianity was not only compatible with a racist worldview but in fact embraced it. Symptomatic was a cover cartoon by staff illustrator Philipp Ruprecht in the first issue of 1936 titled, simply, “Creation.”Footnote 44 God, represented by two gigantic hands from heaven, is shown blessing a naked Aryan couple with golden complexion as a black man crouches in the dark below. A priest looks on, holding a pamphlet that declares that human races do not exist, as a Jew hides behind him. Next to them a little man cowers in a vial labeled “Uniform Man.” The caption, written in pseudo-poetic style, explains, “The human races are the works of the Eternal One/Don't interfere in His craft, you minnow/Don't seek to meld what He split/Negating Creation's purpose for Judas's sake/World and Eternity would perish/If God and Satan united.”

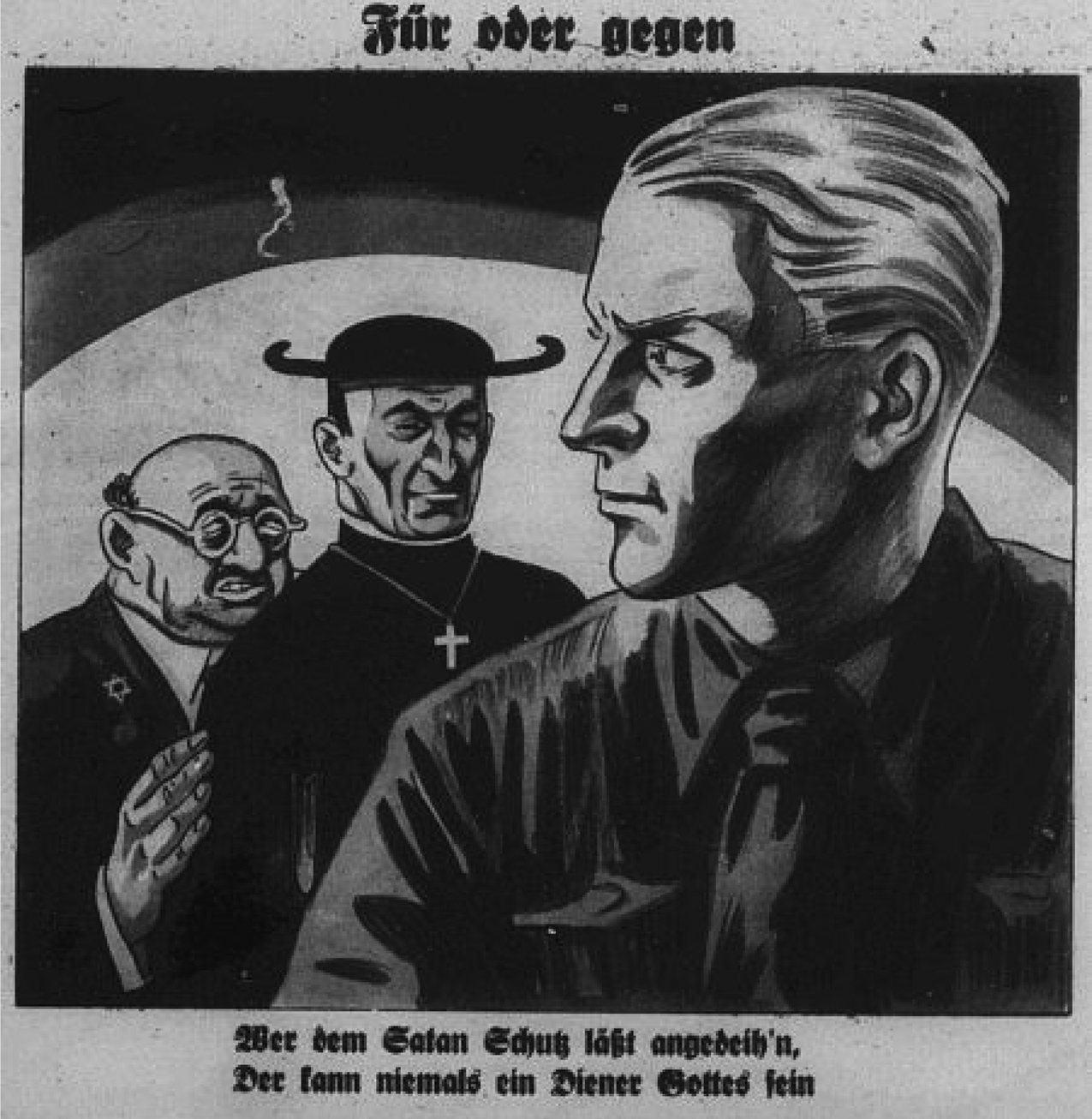

Indeed, for the German weekly, contemporary Catholic doctrine on racial matters was at odds with God's will. In a 1938 cover story boldly titled “The pope denies God's law,” Streicher took issue with a speech in which Pius XI had condemned the recently announced racial policy in Italy.Footnote 45 Streicher wrote: “Man too is God's creation…. And just as stones, plants, and animals differ in shape, color, and purpose, so there is no sameness among humans.” He added, “Those who deny the existence of human races, deny the existence of God…. If the pope did justice to National Socialism and Fascism, he would repudiate the doctrine of his Church…. A pope who puts forth such a doctrine acts against reason. And he who acts against reason is a denier of God's truth.” To hammer home the point, in an accompanying cartoon a blond German man turns around to see a Jew hiding behind a sinister-looking Catholic priest. The caption reads: “He who protects Satan cannot be God's servant” (see Image 3).

Image 3: “He who protects Satan cannot be God's servant” (Der Stürmer 34 [1938]: 1; Harvard Widener Library).

Even more than Der Stürmer's staff writers, Streicher cast the Nazi fight against the Jews in Christian and millenarian terms, frequently relying on biblical imagery and language. In the cover story titled “Our faith” in the first issue of 1937, Streicher explained: “We believe in the mission of German blood and therefore in the mission of German nature. We believe that the path, blessed by God and so wondrous, taken by the German people in the Third Reich will not end in darkness. We believe in the final victory of the German people and the salvation of non-Jewish mankind. He who defeats world Jewry delivers himself from the devil!”Footnote 46

Whereas La difesa justified anti-Semitism by the alleged Jewish oppression of Christians, but recognized Judaism as a religion, Streicher argued that it was not a religion at all. In a 1942 cover story titled “Criminality disguised as religion,” he wrote: “We conceive of religion as everything that links man's actions with the transcendental and the divine.”Footnote 47 Citing the works of Jewish writers like Alfred Döblin,Footnote 48 Streicher asserted that even “leading Jews” confessed to Judaism's essentially worldly orientation and obsession with material concerns: “This view is reflected in the biblical tradition of the Torah. In it, what people call the Jewish God is depicted as a diabolical being that commands the Jews to consider themselves God's Chosen People among the non-Jewish peoples, destined to seize all non-Jewish property.” In a similar cover story from 1940, Streicher asserted that, in truth, the Jews were nothing more than an “association for the representation of economic and political interests.”Footnote 49

Not surprisingly, for Der Stürmer the conversion of Jews was meaningless. A 1934 article reported on an exhortation for prayer in a paper published by the archdiocese of Freiburg.Footnote 50 Local Catholics were encouraged to pray for the upcoming Jubilee to help speed the conversion of the Jews. Der Stürmer wrote dismissively of “The ancient delusional belief of solving the Jewish question with baptismal water…. How much longer does the Church think it can ignore the laws of blood and race?” Der Stürmer called on its readers to recite a very different prayer: “Pray that the Lord may help usher in a time when no Jew walks around in Germany anymore. Such a prayer makes sense.” A particularly ironic 1935 cover cartoon depicted an unremarkable scene of a group of people on a street.Footnote 51 The caption clarified what it showed: “We see eighteen Jews in this illustration. Four of them were baptized as Catholics and three as Protestants. There are people who claim that baptized Jews are no longer Jews but Christians. Readers who can identify the baptized Jews to Der Stürmer by marking them with a cross will receive a prize.” Needless to say, nothing in the illustration distinguished the Jews from the converts.

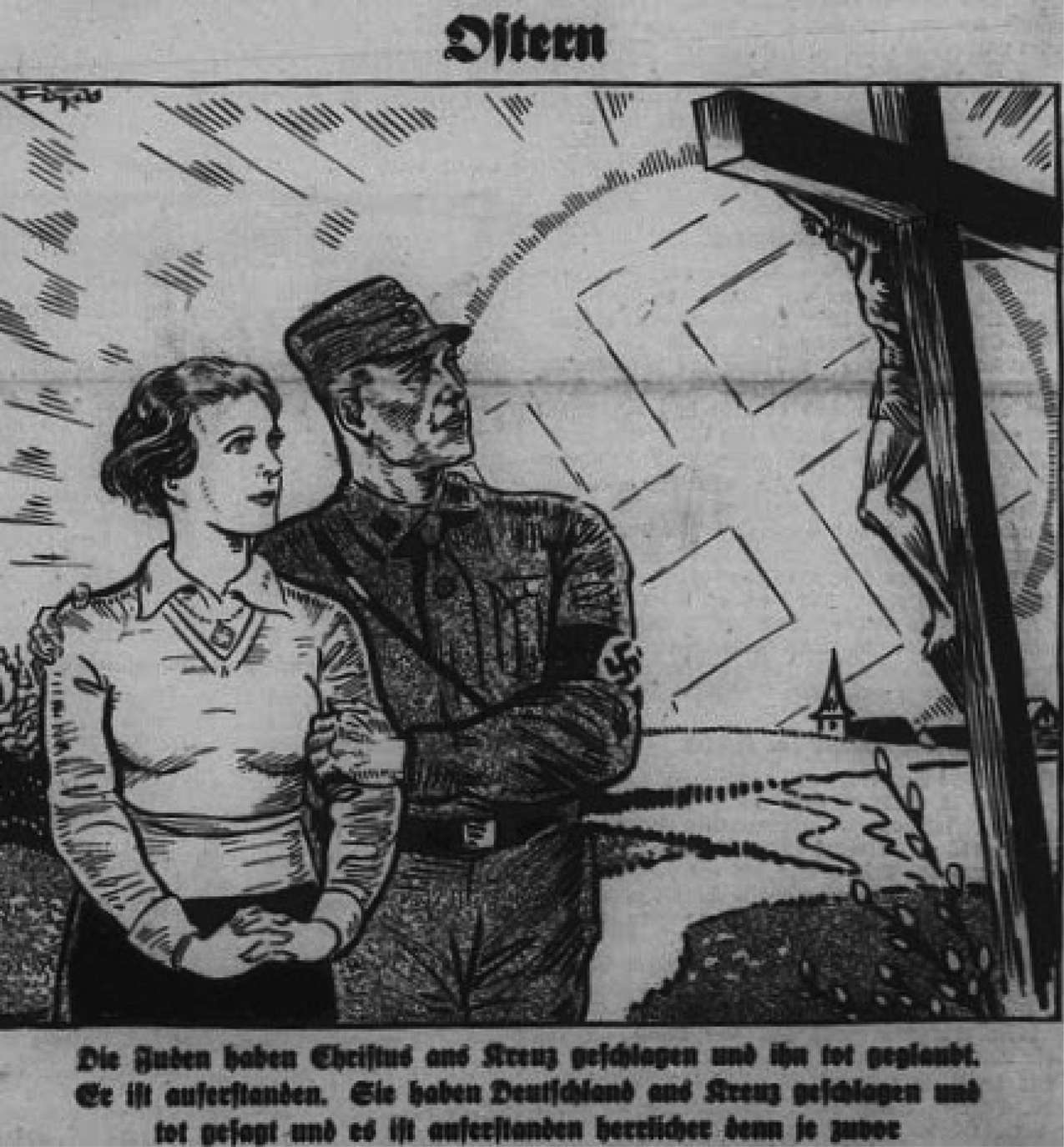

The pages of Der Stürmer, like those of La difesa, were suffused with religious imagery, but the German weekly relied much less on images from familiar, often centuries-old Christian works of art so ubiquitous in the Italian publication. Instead, Der Stürmer featured original drawings by Philipp Ruprecht. These illustrations emphasized National Socialism as a distinctly Christian force and never shied away from bold analogies, such as that between Christ on the one hand and Germany, the Third Reich, and Hitler on the other. For instance, in the cover cartoon of the Easter edition of 1933, Ruprecht celebrated Hitler's recent ascent to the Chancellery by depicting a German couple—the man in SA uniform—looking at a crucified Christ as a Swastika sun rises behind flourishing fields.Footnote 52 The caption explains: “The Jews nailed Christ to the cross and thought him dead. He was revived. They nailed Germany to the cross and thought her dead, but she has been revived and is more glorious than ever before” (see Image 4). Similarly, a title cartoon from 1939 portrayed a Jew smiling at a crucified German man.Footnote 53

Image 4: “The Jews nailed Christ to the cross and thought him dead. He was revived. They nailed Germany to the cross and thought her dead, but she has been revived and is more glorious than ever before” (Der Stürmer 34 [1938]: 1; Harvard Widener Library).

Another 1933 cover cartoon portrays the Nativity scene with modern Germans rather than ancient Jews as curious onlookers. A Jewish man with claw-like fingers despondently turns away, complaining, “Their God does not let them down. As soon as you think them lost, someone is always born who will lead them to the light.”Footnote 54 The allusion to the Führer was unmistakable. The analogy of Christ and Hitler could be found not only in Ruprecht's cartoons; a 1938 article quoted a report in a “Jewish newspaper” from Chicago on a Protestant minister in New Jersey who had stated in an interview that it would be a good thing if they hanged Hitler.Footnote 55Der Stürmer commented: “It is obvious that the Jews are very happy when a Christian minister joins them in their wailing: ‘Crucify him!’”

While Streicher's paper often portrayed itself as a defender of Christianity, in almost every issue it poured vitriol on the established churches of both confessions. In a contribution from 1937, Christa-Maria Rock blamed the very division of Christianity into different confessions on the Jews and their effort “to weaken and grind down the great masses through division.”Footnote 56 She lamented, “The clear awareness of the popes [of the need to keep Jews from positions of authority] was first buried and covered with heresies when full-blooded Jews first seized the Holy See and tainted it with their vices. Since then, Jewry has freely raised its head in all confessions and sects.”

Der Stürmer frequently attacked individual priests deemed guilty of straying from Nazi ideology by their efforts to show the common descent of Judaism and Christianity. Not all priests were bad, though, and the weekly consistently made a distinction between Priester and Pfaffe, the latter a traditional derogatory term for a priest. According to a 1936 article, the German people knew how to distinguish between the two: “Priests are true disciples of the Son of Man.… Priests give to God what is due to God, and give to the state what is due to the state.”Footnote 57 By contrast, a Pfaffe saw his post merely as a means for conducting political business and he poisoned, rather than shepherded, his flock. While many clerics were unfortunately Pfaffen, some had experienced a change of heart since the Nazi rise to power: “Today hundreds of them wholeheartedly come out in favor of Adolf Hitler. They thank National Socialism for saving the Christian faith from imminent doom. They thank him for saving the churches from the torch of Communism.”

In his March 1937 encyclical Mit brennender Sorge, Pius XI condemned aspects of Nazi ideology and the German government's many breaches of the Reichskonkordat treaty that it had signed with the Vatican in 1933. In response, Hitler authorized the ramping-up of the well-publicized “immorality trials” of monks, nuns, lay brothers, and priests. Given that Der Stürmer had been eagerly reporting on these trials since they had begun the previous year, it is no surprise that the paper played an important role in this campaign to undermine the Catholic Church's reputation. In one cover story from 1936, staff writer Ernst Hiemer, a long-time collaborator with Streicher, wrote: “Week after week the public learns about new sexual crimes by clergy, friars, and nuns. They have caused a wave of indignation among the German people.”Footnote 58 He also pointed out a silver lining: “Those who wish the people well and contribute to building their future are grateful to destiny that it opened the eyes of those who still believed in the illusion of the virginity and sanctity of what is happening inside the monastery walls.”

Der Stürmer repeatedly contrasted the pro-Jewish and, it said, thoroughly corrupted contemporary churches with the words and deeds of past Christian authorities. In this respect, Der Stürmer and La difesa were similar, since Streicher's paper portrayed the Nazi racial laws as a logical extension of traditional church practices mandating the separation of Jews from Christians. In a 1940 article, a Leipzig University professor proclaimed: “The Nuremberg Laws, too, are not an invention of National Socialism! No! Already in the medieval period, measures were taken to oppose racial pollution.” National Socialism's goal, he stressed, was to end racial pollution once and for all.Footnote 59

In a 1942 article, in response to reports that the Vatican library employed a Jew, staff writer Hans Eisenbeiß provided a detailed list of the anti-Jewish measures that various popes had introduced, writing, “There was a time when the popes did not employ Jews as librarians. Back then they were considered the descendants of the killers of Christ and were treated accordingly. Testimonies to this period are the papal bulls decreed for the protection of the Church from the people of the devil.”Footnote 60 In a later article on Paul IV's 1555 bull that confined Jews to the ghetto, Eisenbeiß commented: “The best among the popes have always been the fiercest enemies of the Jews.”Footnote 61Der Stürmer drew on many other historic Christian figures as witnesses against the Jews, and frequently quoted such churchmen as Tertullian, Ambrose, Thomas Aquinas, and Martin Luther.

Luther had pride of place in the paper's anti-Semitic arsenal. In a 1941 contribution, Siegfried Goetze wrote: “Luther an anti-Semite? Some may have been surprised when not long ago they heard about Luther's fierce commitment against the Jews. That is because his anti-Jewish writings had remained ‘forgotten’ and unknown until very recently.”Footnote 62Der Stürmer did its best to ensure that its readers would know of Luther's loathing of the Jews, and more than fifty articles from 1933 to 1943 included quotes from his tract On the Jews and Their Lies and his Table Talk. The paper regularly criticized the contemporary Lutheran Church for straying from Luther's teachings. As Goetze wrote, the Lutherans had recently promoted the belief that Luther viewed the Jewish problem as a religious rather than a racial one, to be overcome by conversion. Goetze declared: “The fact that today they can spread such an interpretation is proof of how alien Luther's struggle against all things un-German has become to his own Church and how they could successfully render ‘forgotten’ Luther's words against the Jews.” It was Luther's knowledge of the Jewish “will to destroy,” argued Goetze, that led him, in his attempt to defend the German people, to demand the expulsion of the Jews and the burning of their synagogues.

Yet, for Der Stürmer the greatest anti-Semite in history was not Luther but Jesus himself. Streicher set this out in a long 1943 article, “What did Jesus of Nazareth really teach? He taught what to do in order to pass muster before God and men. He warned about the hypocrisy of the Pharisees and the high priests.”Footnote 63 Streicher went on to paraphrase a passage from the Gospel of John (8:44), one frequently invoked in his paper: “He warned about the Jewish threat with the words: ‘The Jews are murderers from the beginning, their father is the devil!’” Streicher added: “These were the morals that gave the Jews reason to make Christ suffer the torment of a Bolshevist martyrdom and to let him perish on the cross on Golgotha.” According to Der Stürmer's editor, the Jews did not want Christian pastors to remind their flocks of this history, because they knew that “no true Christian can feel love for the descendants of Christ's killers. That is why they praise those priests who preach one should love even his enemies.” Streicher and other Stürmer writers routinely branded such priests “Pharisees.” A 1935 article predicted what lay in store for them: “One thing is certain: the time will come when every single German Christian will speak with profound contempt of those who abused their priestly robes by taking the side of those who have been cursed by Christ for all time.”Footnote 64

With its embrace of Jesus, Der Stürmer took a clear stance on a potentially delicate issue. Some völkisch currents in the Nazi Party, notably the “neo-Paganists” around Alfred Rosenberg, sought to abolish the worship of Jesus on the grounds that he was a Jew,Footnote 65 while Streicher's paper was adamant that Jesus was Aryan. A 1938 cover story by staff writer Karl Holz provided a lengthy discussion of this issue.Footnote 66 Holz attacked the neo-Paganists, writing, “They are the supporters of a so-called ‘religious movement,’ which has nothing to do with religion or with a movement.” He faulted them and other “one-hundred-and-fifty-percent völkisch” currents for siding on this issue with the “Jews’ clerical minions” when they claimed that Christ was a Jew. “With this view and their shouting, both [groups] promote neither the truth nor the German people. They only help the lie and the Jews.” Holz then expounded on the proper völkisch perspective with reference to “the great racial laws” to which men are subject: “One of these laws says: A teaching that does not come from Nordic blood and does not contain the Nordic spirit cannot spread among Nordic peoples.” He added: “Christ was one of the greatest and most brilliant figures that Earth has ever produced. Those who say this Christ was a Jew say something incredibly stupid.” The accompanying cartoon showed Christ's bleeding feet nailed on the cross and a mischievously grinning Jew.

If Christ was not a Jew, then neither should the Old Testament be considered part of Christianity. In fact, according to Der Stürmer, the God of the Jewish scriptures had nothing to do with the God of the New Testament. Streicher wrote in a 1944 cover story: “It was a great error to believe that the God whom the criminal Jews created for themselves was the same God non-Jews had to believe in…. The Jewish God Jehovah told the Jews to devour the peoples of the Earth and to enslave them.”Footnote 67 While Jehovah preached hate and crime, the Christian God proclaimed love and bestowed eternal peace on humanity. If a people had ever been “chosen,” it was the German people, destined to deliver mankind from the Jewish scourge.

In a 1936 cover cartoon, a boy and a girl, blond and dressed in the garb of Nazi youth organizations, cast a skeptical look at a giant book labeled “Old Testament.” A sinister-looking Jewish man eyes them from behind the tome as a Catholic priest looks on. The caption reads: “The German youth does not understand the spirit that emanates from the book.”Footnote 68 A 1940 article reported Luther's regret later in life, having by then gotten to know the Jews better, that he had translated the Old Testament. Such regret, Der Stürmer commented, was unnecessary, for the Old Testament was in fact a useful record of age-old Jewish crimes: “The Old Testament, in the hands of the enlightened and the free, is a weapon that helps fulfill Martin Luther's demand in his book ‘On the Jews and Their Lies’: the destruction of the Jew!”Footnote 69

CONCLUSIONS

The vast majority of both Italians and Germans were at this time at least nominally Christian. The two regimes were determined to render the alleged Jewish threat intelligible and visceral to the people, and they found it effective to do so at least in part in Christian terms. The most important propaganda vehicles against the Jews in each country, La difesa della razza and Der Stürmer, regularly affirmed that the regimes’ anti-Semitic ideas and measures were not a break with Christian tradition but its culmination. A proper Christian, they argued in issue after issue, seeks to destroy those who killed the redeemer of mankind and have fought his followers ever since. For support, they could rely on the abundant anti-Semitic themes and figures found in the Christian tradition.

While the two publications showed many similarities in the way they demonized the Jews, the styles they employed were quite different. Julius Streicher and his staff were frank about the fact that theirs was a Kampfblatt (“paper for the struggle”) to “enlighten” working people on the Jewish question with the goal of making anti-Semitism a mass movement. In a lengthy 1936 cover story, Ernst Hiemer wrote that it was in order to advance this mission that the paper employed “simple,” “repetitious,” and even “salacious” language “of the people.”Footnote 70 Many issues also featured writings from academic contributors, whose credentials Der Stürmer staff had no compunctions about exploiting. Yet Hiemer observed in his article that “puny ‘intellectuals’” would not solve the Jewish question.Footnote 71

La difesa della razza, by contrast, though it hardly lacked in vulgar anti-Semitic and racist caricatures, sought to wrap itself in a cloak of scientific authority. Each issue carried the subtitle “Science, Documentation, Debate,” and its pages were filled with articles by university professors employing all the academic prestige of their positions. Yet, while its articles on the scientific basis of racism and the geographical distribution of races were typically penned by authors in positions of academic authority, the same was not true for its many articles detailing the Catholic warnings against the dangers posed by the Jews. These were not generally written by professors of theology or even by priests.

If the two papers were similar in equating Christianity with anti-Semitism, their contrasting stance towards the church(es) mirrored the very different church-regime relations found in Italy and Germany. Despite recurrent frictions, Mussolini largely succeeded in his attempt to make the Catholic Church a supporting pillar of his regime, especially after the 1929 signing of the Lateran Pacts. Pope Pius XI's death in early 1939 prevented an open confrontation between the Vatican and the regime over Mussolini's new racial doctrine, since Pius XII moved quickly to repair frayed relations with the Fascist regime. Accordingly, the authors of La difesa papered over any potential conflict on issues such as the conversion of Jews and painted themselves instead as the defenders of the Catholic Church against the Jewish enemy.

Mussolini and his associates had been well aware that their new “racial” laws could provoke conflict with the Roman Catholic Church and took measures from the very beginning to play down any contrast between the newly unveiled Fascist racial doctrine and Church teachings. To this end, they constantly stressed that they were not imitating the Nazi racial doctrine but articulating something very different. The authoritative, Vatican-overseen Jesuit bimonthly La Civiltà cattolica called attention to this difference in its first coverage of the new racial policy, in 1938.Footnote 72 Germany's National Socialist regime adopted no such defensive attitude in introducing its anti-Semitic policies, yet, as shown by the case of Der Stürmer, even one of its famously anticlerical publications would not openly cast itself as opposed to Christian teachings. The tensions between the Nazi regime and the Christian churches derived primarily not from its racial or anti-Semitic policies but, at least in the case of the Roman Catholic Church, from Nazi attempts to limit the influence and position of the Church itself and to substitute the state for the Church as the center of the people's allegiance and identity.

In contrast to the attempts of many among the Nazi elites to create a völkisch, Aryanized Christian church loyal to the regime, as explored by Steigmann-Gall, Bergen, and other scholars, less attention has been paid to the Italian Fascist regime's syncretic ambitions and successes. Examination of La difesa della razza offers several points worth pursuing along these lines. As noted above, references to warnings offered by Church authorities regarding the Jews in the magazine's pages overwhelmingly cited Italian sources: whether saints, popes, or religious iconography. Although there was no lack of Church anti-Semitic sources coming from outside of Italy to choose from, these received relatively little attention. This nationalization of Roman Catholicism found simultaneous expression in the decision of Pius XII, shortly after becoming pope, to proclaim Francis of Assisi and Catherine of Siena as the co-patron saints of Italy, the result in part of a campaign initiated by various Fascist youth organizations a decade earlier.Footnote 73

Our examination of the use made of Christianity in demonizing the Jews in these two publications also raises the question of how useful the concept of “political religion” is in characterizing the Italian Fascist and German National Socialist regimes. Rooted in a secularization theory in which these modern political movements take on many features of, and in some sense take the place of, traditional religions, the approach has generated a large literature.Footnote 74 There is little doubt that both regimes did promote secular forms of saint worship, myth-making, and ritual, and references to Mussolini and Hitler in quasi-divine terms are easy to find. Yet the claim that these were, or aspired to be, new forms of religion that would displace the old remains controversial.

Adamson, in recently raising this question in the context of the Italian case, notes that “the fact that Fascism and the Catholic Church enjoyed a ‘substantial collaboration’ or ‘cohabitation’ renders rather poignant the one major lacuna in the current historiography: our total lack of an account integrating this relationship with the fascist sacralisation of politics.” He adds that the most prominent exponent of the political religion approach to these two regimes, Emilio Gentile, in describing Fascism as a political religion, had rather little to say about its relationship with the Church.Footnote 75 Gentile, whose theory of political religion is grounded in his theory of the “sacralization of politics,” identifies this phenomenon with “the formation of a religious dimension in politics that is distinct from, and autonomous of, traditional religious institutions.”Footnote 76

Here our examination of the use of Christian images and authorities by Der Stürmer and La difesa della razza offers considerable insight. The two publications are particularly telling for this purpose in that they were produced by some of the most secular elements of the two regimes. That both made regular use of the most “traditional” religious materials available and portrayed themselves as defending traditional religion makes it difficult to portray the two movements as new forms of secular religion. Yet the differences we find between the two publications demand that we make some distinction here. Toward that end, rather than embracing the concept of “political religion,” it is worth considering whether the alternative concept of “clerico-fascism” may better characterize the relation of these regimes to the traditional churches.

Pollard has recently reviewed historical work that uses this concept of clerico-fascism to analyze forms of fascism in interwar Europe. They have in common, he writes, “a belief that fascist movements and ideas offered the best political vehicle for the protection and promotion of religious interests and objectives and a sense that those ideas were consonant with Christian ideals and practices.” As he notes, historians who embrace this approach stand in direct contradiction with those who portray these fascist regimes as a product of secularization.Footnote 77

The case of La difesa della razza clearly lends support to the conclusion that clerico-fascism is a better fit for the Italian case than is political religion, if the latter is taken to refer to a new, secular religion separate from the traditional churches. The magazine constantly cited Roman Catholic Church authority and portrayed what many have seen as the Fascist regime's greatest departure from Church authority—its racial campaign—as rooted in the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church itself.Footnote 78

Examination of Der Stürmer suggests that the German case is more complicated, partly due to the multiplicity of Christian denominations and their differing relations with the Nazi racial state. While virtually no criticism of the Roman Catholic Church was broached by the Italian publication, Der Stürmer's pages contained regular attacks on Christian clergy. Yet these attacks were phrased not in terms of the failure of those clergy to embrace a new, nationalist, secular religion but, on the contrary, their failure to stick to traditional Christian teachings, particularly those associated with Martin Luther. Our own observations in this sense are in line with Steigmann-Gall's argument: “Political religion theorists argue that the Nazis’ ‘theology of race’ was religious but anti-Christian; however, the Nazis themselves claimed that it was Christian.”Footnote 79 We would only modify Steigmann-Gall's statement by specifying that most of the Nazis thought that their views of race were in line with their Christian religion.

More recently, Munson, while pointing out that “the boundary between religious and racial anti-Semitism has often been blurry and porous,” and finding that Christian anti-Semitism provided important support for the Nazi campaign against the Jews, nonetheless insists, “The distinction between Nazi and fascist racial anti-Semitism and traditional Christian hatred of the Jew is real.” The former, in this view, was grounded largely in a pseudoscientific racism and was therefore distinct from Christian anti-Semitism.Footnote 80 But what may be “real” from an abstract, analytical perspective may be less useful when applied to historical analysis. To contrast Nazi/fascist anti-Semitism with “traditional Christian hatred of the Jew” leads to a view of the former that is shorn of its Christian sources and Christian themes, a view that, as our examination suggests, is misleading.

While, in general, Italy's clergy took enthusiastic part in this creation of a national Catholicism linked to the Fascist regime, the Vatican was more cautious. It is notable that the only evidence of Vatican displeasure with La difesa della razza during Pius XII's papacy that we could find in the Italian state archives puts considerable emphasis on just this point.Footnote 81 A Pro-Memoria (memorandum) complaining about La difesa della razza, which was sent from the Vatican Secretariat of State and ultimately made its way to Mussolini in late March 1939, took particular exception not to the demonization of the Jews but to La difesa articles that suggested Catholicism was founded in Rome and was by nature Italian.Footnote 82

Der Stürmer's unabashed disdain for the established churches clearly reflected its owner and editor's vehement anticlericalism. Streicher had considerable leeway in making all kinds of allegations against not only the Jews but also the churches, while an official paper such as the Nazi Party's Völkischer Beobachter had to show some restraint. Far from diminishing Der Stürmer's importance, this was precisely the role the paper was supposed to play in the Nazi propaganda machine.Footnote 83 As Lackey has shown, Streicher seems to have genuinely believed in the Christian basis of his vulgar anti-Semitism and was far from simply an opportunist in seeking to enlist figures like Jesus and Luther in his fight, including when on trial at Nuremberg.Footnote 84

Surprisingly, given the importance of Der Stürmer for the Nazis’ propaganda against the Jews, the existing literature has paid scant attention to the fact that the paper consistently framed its extreme anti-Semitism in distinctly positive-Christian terms.Footnote 85 In The Holy Reich, Steigmann-Gall devotes less than a paragraph to this issue, dismissing Der Stürmer as a “highly disreputable newspaper” that “leaves room for skepticism.”Footnote 86 Such skepticism may be reasonable when trying, as Steigmann-Gall does, to ascertain the Nazi elite's true beliefs. Leading Nazis’ views on religion were highly diverse, as Koehne argues, and their only apparent common denominator was that “religion had to measure up to their hyperracialized and anti-semitic ideology.”Footnote 87 In effect, the German weekly exposed ordinary Germans, including many who were unaffiliated with the German Christian movement, to positive-Christian ideas, including the embrace of an Aryan Jesus.Footnote 88

Indeed, Der Stürmer likely had a far greater influence on the masses than did the Institute for the Study and Eradication of Jewish Influence on German Religious Life highlighted by Heschel, since the Institute was a relatively obscure think tank. Similar to Steigmann-Gall, Heschel downplays the importance of Streicher's “propaganda rag,” arguing that, by comparison, “the moral and societal location of clergy and theologians lends greater weight to the propaganda of the Institute.”Footnote 89 She adds: “Propaganda coming from the pulpit calls forth far deeper resonance than that spoken by a politician or journalist.” This may be true, but Der Stürmer's vitriol against the Jews, if less authoritative than the corresponding pronouncements of the Protestant ministers, may have reached far more Germans. It was precisely the paper's crucial role in turning the Germans against their Jewish fellow citizens that led the judges at Nuremberg to send Streicher to the gallows.Footnote 90

Many recent important works have detailed how, in the years leading up to and including the massacre of Europe's Jews, the Christian churches behaved toward the German and Italian regimes and their persecution and eventual murder of the Jews. By looking instead here at the way the two regimes made use of Christianity in their demonization of the Jews, and pointing out ways in which the two differed in this respect, we hope we have cast new light on this relationship and pointed to new directions for further historical study.