The legalization of cannabisFootnote 1 in the United States remains a polarizing topic. In recent years, cannabis legalization initiatives have been passed in a handful of states and many other states have implemented medical marijuana programs. Presently, ten states have fully legalized recreational use of cannabis and twenty-one states have approved ballot initiatives that legalize the use of cannabis for medical reasons. Although support for legalization reached majority approval nationally in 2013, the flowering plant remains illegal under federal law and in the majority of U.S. states (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2018). Moreover, as of this writing, neither major political party platform currently advocates for the legalization of cannabis at the federal level.

In the popular culture, drug use, including cannabis, has been historically associated with undesirable facets of society and moral panics surrounding countercultures that threaten the socially normative hierarchy of White America (Schlussel Reference Schlussel2017). For example, cannabis prohibition in the 1930s was not based on scientific evidence of its adverse effects, but was instead based in racialized hysteria and paranoia surrounding the effects that cannabis had on users (Booth Reference Booth2005). The association of cannabis with socially deviant subcultures progressed over the decades from an association of cannabis with Black and Hispanic jazz musicians in the 1930s and 1940s, to the hippie movement of the 1960s, to “gangsta” rappers of the 1990s. Given the racialized rhetoric surrounding cannabis prohibition throughout American history, it follows that individuals who harbor more racial animus may indeed be more skeptical of marijuana legalization. However, to our knowledge, no empirical research has investigated this association. This research seeks to address this gap in knowledge about the correlates of marijuana attitudes by asking: Do Whites’ racial attitudes inform their opinions on marijuana legalization?

Additionally, it has been well documented that the manifestations of racial prejudice have shifted over the past several decades as subtler forms of prejudice have supplanted overt, blatant forms of old-fashioned racial prejudice (Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997; Bobo Reference Bobo2011). These newer forms of prejudice, while perhaps not as pernicious as old-fashioned prejudice, have nevertheless been shown to be relatively strong predictors of political attitudes among White Americans (Krysan Reference Krysan2000). Thus, it is important to assess whether different types of racial prejudice may have differential effects on attitudes towards marijuana legalization. Our second research question addresses this issue by asking: Do different types of racial prejudice have varying associations with attitudes towards cannabis legalization?

Finally, the shift in racial attitudes has occurred concurrently with the shift in attitudes towards marijuana noted above. Thus, it is possible that the association between different types of racial prejudice and attitudes towards cannabis legalization may have changed over time. Indeed, according to Phillip Schwadel and Christopher G. Ellison (Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017), time periods and birth cohorts have the largest effect on legalization attitudes, due to the cultural and political forces of certain eras. Thus, we assess the associations above in historical context by asking, has the association between racial attitudes and views of cannabis legalization changed over time or across generations as cannabis has become more socially accepted?

THE RACIST ROOTS OF CANNABIS PROHIBITION

Political forces often influence attitudinal trends in acceptance for cannabis legalization (Schwadel and Ellison, Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017). For example, the U.S. government’s marijuana prohibition propaganda proved successful in influencing public opinion for most of the twentieth century. The Great Depression saw colossal unemployment rates that created animus and paranoid angst towards “job-stealing” Mexican immigrants, leading to increased public concern surrounding the plant that was perceived as coming from Mexico. During this period, the negative perceptions of cannabis use were also extended to Black Americans, social degenerates, and Jazz musicians. A fomenting wave of pseudo-scientific research linked social deviance, criminality, and violence with marijuana use, particularly among members of non-White ethnic and racial groups (Booth Reference Booth2005).

In the 1930s, President Herbert Hoover appointed Harry Anslinger as the first commissioner of the newly created Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Anslinger, a staunch anti-drug crusader who pushed prohibition using racist characterizations of drug users, was the primary instigator of fear-mongering tactics used to influence public opinion on marijuana (Booth Reference Booth2005; Provine Reference Provine2011). One of his more memorable quotes on the issue of marijuana states: “There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S., and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos and entertainers. Their satanic music, jazz and swing result from marijuana use. This marijuana causes white women to seek sexual relations with Negroes, entertainers and any others” (Solomon Reference Solomon2020). Anslinger used myriad scare-tactics, alarmist rhetoric, and disinformation to firmly establish his narrative against cannabis. By implementing a massive, hyperbolic, and racially charged anti-marijuana crusade, he positioned cannabis as a catalyst of crime and social ills (Booth Reference Booth2005). The propaganda promoted by anti-drug and temperance coalitions cultivated public paranoia, subsequently pressuring the federal government to take action against the “demon weed.”

Motion pictures were an additional element of the anti-marijuana crusade that warned against the moral turpitude and social degradation that cannabis use represented. Exploitation films like Reefer Madness (1936) and Marihuana (1936) sensationally depicted outrageous scenarios as a result of cannabis use. Late-night marijuana parties resulting in wild orgies, murder, and rape are common themes portrayed in these films. In characterizing cannabis as a deadly menace wreaking social havoc, these films assisted in pushing this narrative (Stringer and Maggard, Reference Stringer and Maggard2016). The alarmist approach to cannabis had an immense effect on public perceptions of the plant and subsequently garnered the support needed to make the plant illegal (Booth Reference Booth2005; Stringer and Maggard, Reference Stringer and Maggard2016). After a lengthy and deceptive anti-marijuana campaign, Anslinger was successful and the plant became federally illegal to sell or possess in 1937. Moreover, one of the first polls ever conducted on legalization in 1969 indicated that only 12% of Americans supported a change in cannabis laws (Swift Reference Swift2016).

The “moral panic” surrounding cannabis continued during the Nixon administration, which imposed harsher criminal sentencing of street drugs (Nielsen Reference Nielsen2010). Moving away from blatant racial rhetoric, the post-civil-rights discussion of drug use cleverly contained dog whistle terminology to render support from Whites to get behind an increasingly aggressive stance toward drug offenses. Using terms like “tough on crime” and “law and order,” President Nixon was able to communicate to his White supporters a symbolic form of racial aggrandizement that assisted in garnering support for increasing punitive consequences of using cannabis. A 2016 Harper’s Magazine article included a 1994 quote from former Nixon domestic policy-maker, John Ehrlichman, who stated: “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or Black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and Blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did” (Baum Reference Baum2016). The revelation from this Nixon whistleblower exhibits the racial undertones that government officials used in order to racialize drug policy without employing explicitly racist rhetoric.

Continuing the legacy of increased severity of penalization for marijuana use, the Reagan administration ramped up their enforcement of drug use by expanding the “War on Drugs.” Before Reagan was even sworn in as president, he claimed “Marijuana is probably the most dangerous drug in America” during his 1980 presidential campaign. During his term as president, Reagan signed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act and the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, establishing mandatory sentencing for drug possession and heightened penalties for federal marijuana offenses. The Anti-Drug Abuse Act would later be amended by the Clinton administration to include a “three-strikes” provision that mandated life sentences for repeat drug offenders (Sacco Reference Sacco2014).

The racial rhetoric that surrounds cannabis use is seen in every corner of government. During his time as a federal judge in a 1986 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing, then Alabama Senator Jeff Sessions stated that “I thought those guys [the Ku Klux Klan] were OK until I learned they smoked pot,” surmising that he believed that the infamous terrorist organization was comprised of decent people until he found out some were using cannabis. Nearly two decades into the twenty-first century, publicly elected officials continue to subscribe to blatant racism and factually incorreect opinions on cannabis legalization. On January 6, 2018, Kansas State Representative Steve Alford addressed marijuana legalization at a town hall meeting in Kansas. The following statements that Rep. Alford publicly delivered were recorded on video and posted to YouTube:

What you really need to do is go back in the 30s, when they outlawed all types of drugs in Kansas and across the United States. And what was the reason why they did that? One of the reasons why—I hate to say it—is the African-Americans were basically users and they basically responded the worst to all those drugs because of their character makeup, their genetics. So, basically, what we’re trying to do is a complete reverse, with people not remembering what’s happened in the past.

This display of a White public official inserting the racist myths of the 1930s prohibition campaigns into the debate about cannabis in 2018 exemplifies how prejudiced attitudes may continue to shape marijuana legalization support. However, statistics show that most of the country would disagree. At the time these recent statements were made, approval for marijuana legalization had never been higher, especially among Whites. In 2016, the majority (59%) of Whites approved legalizing cannabis (Pew 2016). The current research aims to unravel the relationship between Whites’ prejudice attitudes and their belief that cannabis should be made legal. How deeply embedded is racial prejudice into Whites’ attitudes towards cannabis legalization?

ATTITUDES TOWARD CANNABIS

According to recent Pew (2018) and Gallup (McCarthy Reference McCarthy2018) polls, a strong majority (62% and 66% respectively) of Americans support the legalization of marijuana. Showing a significantly stark contrast from public acceptance in 1990 when a mere 16% (Pew 2018) approved of legalization, marijuana attitudes have rapidly changed among most facets of society. Until recent years, very little research has been conducted on public attitudes about marijuana legalization, leaving a dearth of literature exploring the issue. Many studies have inquired into marijuana use and health effects, but public opinion research about the predictors of support for legalization has been neglected. Of the few studies conducted on marijuana legalization attitudes, key findings suggest that time periods and cultural and political shifts have the largest effect on positive legalization attitudes, as young Americans and those completing surveys in more recent years are the most supportive of legalization (Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Twenge and Carter2017; Schwadel and Ellison, Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017).

When the earliest survey responses on marijuana legalization attitudes were recorded, legalization was not particularly popular. In 1969, 12% of Americans were favorable to legalizing marijuana (Pew 2018; Swift Reference Swift2016), a stark contrast to current attitudes. Through the 1970s we see a minimal increase in positive marijuana legalization attitudes, peaking in 1977 with 28% of the public approval (Swift Reference Swift2016). Entering the 1980s, a sharp and steady decline in positive legalization attitudes starts to occur, remaining under 15% until 1990. However, since 1991 there has been a significant and rapid increase in support for legalization.Footnote 2 Presently, 62% of the public supports legalization. Moreover, research indicates that there has been an increase in support among almost every demographic group. However, due to the paucity of research exploring marijuana legalization attitudes, there are only a handful of studies that have analyzed data on socio-demographic predictors.

Aside from the most salient predictors of marijuana legalization attitudes (time period and birth cohort), some socio-demographic factors are also significant predictors of marijuana legalization support. Using aggregated GSS data from years 1973–2014, Schwadel and Ellison (Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017) find that males are more likely than females to support legalization. Those with a bachelor’s degree or higher are more likely to support legalization than those with less than a high school diploma. Democrats are more likely to support legalization compared to Republicans or Independents. Income has a positive association with legalization support; as income goes up, so do the odds of supporting legalization. Pacific region residents are the most likely of any region to support legalization. Additionally, religion has a strong negative effect on support for legalization, with Evangelical Protestants and those who regularly attend religious services being much less likely to support cannabis legalization compared to those with no religious affiliation. All racial groups have shown steady increasing support for legalization since 1990, but in the twenty-first century, Whites appear to be more likely than Blacks or Hispanics to support legalization, as support among Whites has increased dramatically in the past decade (Schwadel and Ellison, Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017).

Education is an additional correlation of marijuana attitudes—through much of the 1980s, differences in education levels had little effect on positive marijuana attitudes. However, since 1990 educational differences have been growing and as of 2014, those with a bachelor’s degree and those with a high school diploma were much more likely to support marijuana legalization compared to those without a high school diploma. These patterns illustrate that the previous hysteria surrounding marijuana appears to be receding over time. Through broad, generational changes, the perceived threat of marijuana today is a far cry from when the first polls on this topic were conducted and support for legalization amongst all socio-demographics has never been higher. This research seeks to build on the limited literature on marijuana attitudes by examining its association with characteristics beyond the basic demographic factors examined to date.

THE SHIFTING FORMS OF RACIAL PREJUDICE

Just as attitudes have evolved about cannabis legalization over the past several decades, so have racial prejudice attitudes. During the Jim Crow era, overt, legal racism against Blacks was the status quo (Drakulich Reference Drakulich2015); in this era, Black Americans were subjected to forced segregation, public hangings, and formal exclusion from economic, civic, and governmental participation. The two related facets of the “old-fashioned” prejudice that characterized the Jim Crow era are racial essentialism and biological superiority. Racial essentialism is the idea that individuals can be classified into distinct, discrete, biological races that have behavioral significance. Biological superiority is the taken-for-granted belief that Whites are biologically superior to Blacks. For example, a key component of this racist regime was laws forbidding miscegenation. These laws were based directly on these dual ideological girders because they assumed that inter-racial marriages and their potential progeny represented a threat to the racial purity and superiority of Whites (Pascoe Reference Pascoe1996).

Whites’ public attitudes espousing racial inferiority among Blacks significantly declined following the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s as it became socially unacceptable to overtly declare that Black Americans are biologically inferior to Whites. However, racial prejudice has not vanished from contemporary society. According to substantial literature, racism has transformed from the overt expressions of the Jim Crow era to symbolic forms of racial prejudice (Bobo and Kluegel, Reference Bobo and Kluegel1993; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2002; Henry and Sears, Reference Henry and Sears2002; Quillian Reference Quillian2006). Namely, in the post-civil-rights era, Whites are more likely to use attributes such as cultural differences or individualistic values to justify their general antipathy for people of color and explain social inequalities based on race. Furthermore, new racism’s far subtler racial hostility allows individuals to foster socially acceptable racial resentment without being categorized as “racist” amongst society at large. Whether it is dubbed “modern,” “colorblind,” “symbolic,” or “laissez-faire,” racial prejudice has taken on new forms in recent decades.

In order to achieve precision in the measurement of modern prejudice, this research employs laissez-faire prejudice as the modern form of racial animus. Laissez-faire prejudice frames racial inequality as a result of dispositional attributions of non-Whites rather than biological differences. In addition, individuals who subscribe to laissez-faire prejudice oppose government intervention to promote racial equality, but justify this opposition as part of a general belief in meritocracy and the general principle that the government should stay out of economic matters and not “pick winners and losers.” Importantly both old-fashioned and contemporary forms of racism downplay or dismiss the role of historical and contemporary prejudice and discrimination in shaping contemporary racial inequalities (Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997). This belief implies that contemporary racial inequality is attributable to the character and cultural deficits of racial minority groups (Bobo Reference Bobo2011; Bonilla-Silva Reference Bonilla-Silva2002; Bonilla-Silva et al., Reference Bonilla-Silva, Lewis and Embrick2004). Adhering to these kinds of beliefs allows Whites to ignore the continuing role played by White privilege in structuring economic opportunity in contemporary society. For example, Whites may attribute Black Americans’ lower socio-economic standing to a culture of laziness, rather than to unequal opportunities due to historical and systematic discrimination (Bobo et al., Reference Bobo, Kluegel, Smith, Tuch and Martin1997; Bobo Reference Bobo2011). The main component of this framing is the belief that the Civil Rights Movement has eliminated ubiquitous racial discrimination and systematic racism, resulting in racialized oppression being obsolete (Bonilla-Silva et al., Reference Bonilla-Silva, Lewis and Embrick2004).

Key evidence of this shift is that although beliefs in biological superiority have declined, Whites are still hesitant to support specific social policies to ameliorate racial inequality (Krysan Reference Krysan2000). For example, according to GSS data, Whites’ support for laws against interracial marriage dropped from 36% in 1972, to 11% in 2002. Furthermore, beliefs among Whites that racial differences are due to inborn disability of Blacks dropped from 25% in 1974, to 7% in 2016. However, rather than illustrating an amelioration of racial prejudice, we see a shift of racial attitudes emerge that indicate an evolution of Whites’ racial attitudes, not an elimination. In 1975, 11% of Whites supported the government helping improve the conditions of Blacks’ social and economic standing, changing little to 8% in 2016. Moreover, in 1994 48% of Whites thought Blacks should overcome prejudice without special favors, changing little to 42% in 2014. These attitudinal trends illustrate a theoretical juxtaposition to the narrative that prejudiced attitudes are things of the past. Instead, we see racial attitudes about cultural deficiencies replace racial superiority as the cause of Black Americans’ low social standing. For example, David O. Sears and colleagues (Reference Sears, Laar, Carillo and Kosterman1997) find that Whites’ support for racial policy issues are motivated less by sensible forethought of general effectiveness of the policy, but rather a resentful amalgamation of beliefs about Blacks receiving special favors and not working hard enough to overcome their disadvantages. In light of these shifting racial attitudes, here we examine both whether different types of racial prejudice shape marijuana attitudes and if these associations have changed over the past forty-six years.

SUMMARY AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Despite the well-known links between drug prohibition campaigns and racist political rhetoric, there has been a paucity of research exploring whether racial prejudice is associated with attitudes towards cannabis legalization. This study explores the association of different manifestations of Whites’ racial animus and cannabis legalization attitudes longitudinally. The longitudinal research strategy pursued below will allow us to unpack the political and cultural trends regarding attitudes towards both race and cannabis. Specifically, we establish periods of political forces coupled with eras of racial prejudice to examine whether Whites’ racial resentment is a predictor of cannabis legalization attitudes over time and how this association may have changed as racism evolved and society became more accepting of cannabis use. Our empirical analyses are designed to test the following four hypotheses.

H1: Higher levels of old-fashioned prejudice will be associated with lower support for marijuana legalization.

H2: Higher levels of laissez-faire prejudice will be associated with lower support for marijuana legalization.

H3: The association between old-fashioned prejudice and marijuana legalization attitudes will be weaker in a) more recent cohorts and b) more recent eras.

H4: The association between laissez-faire prejudice and marijuana legalization attitudes will be stronger in a) more recent cohorts and b) more recent eras.

METHODS

Data for this research is drawn from 1972–2018 General Social Survey Cumulative File (GSS). Administered to non-institutionalized English or Spanish speaking adults, the GSS is a repeated cross-sectional survey using a nationally representative equal-probability multi-stage cluster sample of U.S. households. The GSS has been administered since 1972 and has a response rate ranging from 69% to 80% (Schwadel and Ellison, Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017). Because we are interested in Whites’ attitudes towards cannabis legalization, we use only White respondents; also due to very small frequencies we exclude GSS respondents born prior to 1901. All results presented below are weighted using the GSS weight WTSSALL.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable for this research is respondent’s views on marijuana legalization. Respondents were asked if they “think the use of marijuana should be made legal or not;” we code for support of legalization of marijuana as a binary measure with “1” indicating support for marijuana legalization.Footnote 3

Cohorts and Time Periods

Our approach to examining how marijuana attitudes have changed over time diverges from previous work. Specifically, whereas Schwadel and Ellison (Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017) treated each GSS year as a time period and each birth year of GSS respondents as a birth cohort, we instead create substantively meaningful time periods and birth cohorts that correspond with cultural shifts in U.S. society over the forty-six years covered by the data. Specifically, we employ four meaningful birth cohorts to capture the effects of generational changes that may shape marijuana legalization attitudes. We specify individuals born between 1901 and 1944 as the “World Wars Cohort,” individuals born between 1945 and 1964 as the “Baby Boomer Cohort,” individuals born between 1965 and 1980 as “Generation X Cohort,” and individuals born after 1981 as the “Millennial Cohort.” Our sample includes respondents born each year between 1901 and 2000. Similarly, we operationalize time periods using four distinct eras; we specify the years 1972 to 1980 as the “Pre-War on Drugs Era,” the years 1981 to 1996 as the “War on Drugs Era,” the years 1997 to 2012 as the “Medical Marijuana Era,” and the years 2012 through 2018 as the “Legal Marijuana Era.”

Independent Variables

The main independent variables are two manifestations of racial prejudice. First, we operationalize old-fashioned racism with an item asking respondents their opinion on miscegenation. The variable Favor law against racial intermarriage is a dichotomous item indicating a belief that interracial marriage should be illegal (1=Yes)Footnote 4. Second, we operationalize laissez-faire prejudice using an item asking respondents their opinion on government spending to “improve the conditions of Blacks.” For simplicity, we compare respondents who answered “too much and about the right amount,” coded “1” to those who answered “not enough,” to get a binary measure where “1” reflects endorsement of laissez-faire prejudice in the sense of opposition to increased government spending to help Black Americans. Results using the original three categories yielded substantively identical results to those presented below.Footnote 5

Due to different coverage of the measures of prejudice in the GSS, models using the different independent variables cover different periods of survey years and utilize different sample sizes. For example, the “favor law against interracial marriage” variable was only asked from 1972 through 2002 and as such was never asked in the Legal Marijuana Era. Additionally, only nineteen respondents from the millennial generation answered this question. As such, analyses using this independent variable exclude millennials, do not cover the legal marijuana era, and use an unweighted sample of 11,068 respondents. The laissez-faire prejudice measure has coverage in the GSS from 1973 through 2018; the analysis using this independent variable includes respondents from all cohorts and responses for all eras and use an unweighted sample size of 15,125 respondents.

Control Variables

Following Schwadel and Ellison (Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017), all models include controls for age, gender, religion, political affiliation, education, region, and income. These variables are all known predictors of cannabis attitudes, as exhibited by Schwadel and Ellison (Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017). Age is coded in years of age. Gender is measured with a dummy variable for female. We measure religious affiliation with a dummy variable for no religion and Evangelical Protestant (Evangelical Protestants attend religious services more frequently than other Americans and religious service attendance is associated with marijuana attitudes). Political affiliation is measured with dummy variables for Democrats and Independents (Republican is the omitted reference category). Income is a continuous level variable and is measured in dollars.Footnote 6 Education is measured by dummy variables created for bachelor’s degree and did not graduate high school (graduated high school is the omitted reference category). Because of their relatively high levels of positive marijuana attitudes, we include dummy variables that index the Mountain, Pacific, and New England census divisions with all others serving as the reference category. Furthermore, the models include dummy variables that control for children (under 18) in the home, marital status, and urban residence.

RESULTS

Bivariate Results

Tables 1 through 4 present a series of cross-tabs which show how racial attitudes have evolved over the past several decades. Table 1 shows the joint distribution of old-fashioned prejudice and birth cohort. This table shows the decline of old-fashioned prejudice among Americans from more recent birth cohorts. Among those in the World Wars Cohort (born between 1901 and 1944), over one-third of respondents (36.3%) favored a law against interracial marriage. This percentage dropped precipitously to just 13.7% among those in the Baby Boomer Cohort (born between 1945 and 1964) and fell even further to 9.3% among respondents from Generation X. Table 2, which presents the association of old-fashioned prejudice with time period, shows very similar patterns. Namely, in the Pre-War on Drugs Era, over a third of White respondents favored a law against interracial marriage (33.7%), whereas during the War on Drugs Era the percentage favoring such a law had dropped to 20.3%. In the Medical Marijuana Era, the percentage of Whites who favored a law against interracial marriage had dropped to 11.3%.

Table 1. Percentage Distribution of Old-Fashioned Prejudice by Birth Cohort

Source: GSS 1972–2018; N= 11,068; Weighted data

Table 2. Percentage Distribution of Old-Fashioned Prejudice by Time Period

Source: GSS 1972–2018; N= 11,068; Weighted data

Table 3. Percentage Distribution of Laissez-Faire Prejudice by Birth Cohort

Source: GSS 1972–2018; N= 15,125; Weighted data

Table 4. Percentage Distribution of Laissez-Faire Prejudice by Time Period

Source: GSS 1972–2018; N= 15,125; Weighted data

Tables 3 and 4 show the results for laissez-faire prejudice. Table 3 shows that although there has been a decline in adherence to laissez-faire prejudice among more recent cohorts, the shift has not been nearly as dramatic as the change in old-fashioned prejudice beliefs. For example, while the percentage who oppose additional spending on improving conditions for Black Americans declined from the 77.3% seen among the World Wars Cohort, a strong majority of millennials (56.9%) continue to hold this belief. Further, comparing Table 4 to Table 2, while only 11.3% of respondents in the Medical Marijuana Era believed in a law against interracial marriage, 73.2% are against additional government spending on racial equality. The patterns in Tables 1 through 4 underscore the shifting nature of racial attitudes in the United States in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, while overt prejudice has declined markedly, a majority of Whites remain opposed to governmental action on behalf of racial minorities.

Multivariate Results

Previous research on marijuana attitudes using the GSS has utilized the Age, Period, and Cohort (APC) model developed by Yang Yang and colleagues (Schwadel and Ellison, Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017; Yang and Land, Reference Yang and Land2006; Yang Reference Yang2008). This model is used to differentiate the effects of age, period, and cohort by overcoming the linear dependency that exists between these disparate conceptualizations of time (i.e., one can calculate age if you know the survey year and birth year of a respondent). This approach was needed because the authors defined each birth year as a cohort and each survey year as a time period. In this study, our use of a smaller number of substantive cohorts and time periods eliminates the need for the APC specification and allows the research questions to be answered using a standard logistic regression analysis which uses dummy variables to capture the effects of cohort and time period. For each independent variable, we present three models; a main effects model, a model with interactions between prejudice and era, and a model with interactions between prejudice and birth cohort. We use the most recent cohort or time period as the reference categories for these dummy variables.

Table 5 presents results using old-fashioned racial prejudice. Consistent with previous research (Schwadel and Ellison, Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017), our model shows that Democrats (b=.407; p<.001) and Independents (b=.467; p<.001) are significantly more likely to support legalization compared to those who identify as Republican. Furthermore, this model also shows the positive effect for college education (b=.498; p<.001) on support for legalization. Also, consistent with previous literature, Model 1 shows females (b= -.225, p<.000), married respondents (b= -.432, p<.001), and those with minor children at home (b= -.295; p<.001) are less likely to support marijuana legalization. Additionally, Evangelicals (b= -.207; p<.001) and those who attend religious services more often (b= -.205; p<.001) are less supportive of cannabis legalization.

Table 5. Logit Coefficients for Models for Whites’ Support of Marijuana Legalization

Source: GSS (1972–2018); N= 11,068; Weighted Data

Notes: a Reference group for birth cohort is Generation X;

b Reference group for time period is Medical Era

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the main effect for old-fashioned prejudice in Model 1 (b= -.886, p<.001) indicates that support for old-fashioned prejudice has a significant negative association with marijuana legalization support. Specifically, those who support a law against interracial marriage are 59% less likely to support marijuana legalization. Model 1 also shows that, compared to Generation X Cohort, respondents from the Baby Boomer Cohort are more likely to support marijuana legalization (b=.345, p<.001). Additionally, Whites’ support was lowest during the War on Drugs Era (b=-.544; p<.001), with respondents in this time period having odds of supporting legalization about 43% lower compared to respondents in the Medical Marijuana Era.

Model 2 in Table 5 adds the interaction effects of old-fashioned prejudice across birth cohorts. The results are consistent with Hypothesis 3a, indicating that association of old-fashioned prejudice with attitudes towards marijuana legalization has decreased among more recent birth cohorts. This pattern is displayed graphically in Figure 1. As Figure 1 shows, among those in the World War and Baby Boomer Cohorts there are substantial differences in opinion on marijuana legalization based on adherence to old-fashioned prejudice. However, in the Generation X Cohort, opinion on marijuana legalization has no association with old-fashioned prejudice beliefs.

Fig. 1. Support for Legalization of Marijuana by Old-Fashioned Prejudice and Birth Cohort

Source: GSS (1972–2019)

Model 3 in Table 5 shows us the interaction effects of old-fashioned prejudice across eras. In contrast, to the predictions in Hypothesis 3b, Model 3 indicates that the association of old-fashioned prejudice and support for marijuana legalization does not vary by era among Whites. Overall, the results from Table 5 are generally consistent with our expectations that old-fashioned prejudice is associated with support for marijuana legalization among Whites, but the association between old-fashioned prejudice and legalization attitudes has declined among more recent birth cohorts.

Table 6 presents results using the laissez-faire prejudice measure of opposes government spending on helping Black Americans. Results for the control variables essentially mirror those from Table 3. Further, consistent with Hypothesis 2, Model 1 shows that laissez-faire prejudice is significant and negatively associated with support for marijuana legalization (b= -.264, p<.001). This result indicates that those who oppose government spending on assisting Black Americans are 23% less likely to support the legalization of marijuana across all of the survey years.

Table 6. Logit Coefficients for Models for Whites’ Support of Marijuana Legalization

Source: GSS (1972–2018); N= N= 15,125; Weighted Data

Notes: a reference group for birth cohort is Generation X;

b Reference group for time period is Medical Era

Model 2 in Table 6 shows the interaction effects of laissez-faire prejudice on marijuana legalization support across birth cohorts. Consistent with Hypothesis 4a, the model indicates that the negative association between laissez-faire prejudice and marijuana legalization is most pronounced in the Millennial Cohort. This pattern is shown in Figure 2. Figure 2 shows, among early cohorts, adherence to laissez-faire prejudice did little to distinguish respondents who supported legalization of cannabis compared to those who did not. However, among millennial respondents, laissez-faire prejudice is clearly associated with Whites’ legalization attitudes. Specifically, millennials who oppose government spending for Black Americans are nearly 20% less likely to support marijuana legalization, compared to millennials who support additional spending to aid Black Americans.Footnote 7

Fig. 2. Support for Marijuana Legalization by Laissez-Faire Prejudice and Birth Cohort

Source: GSS (1972–2019)

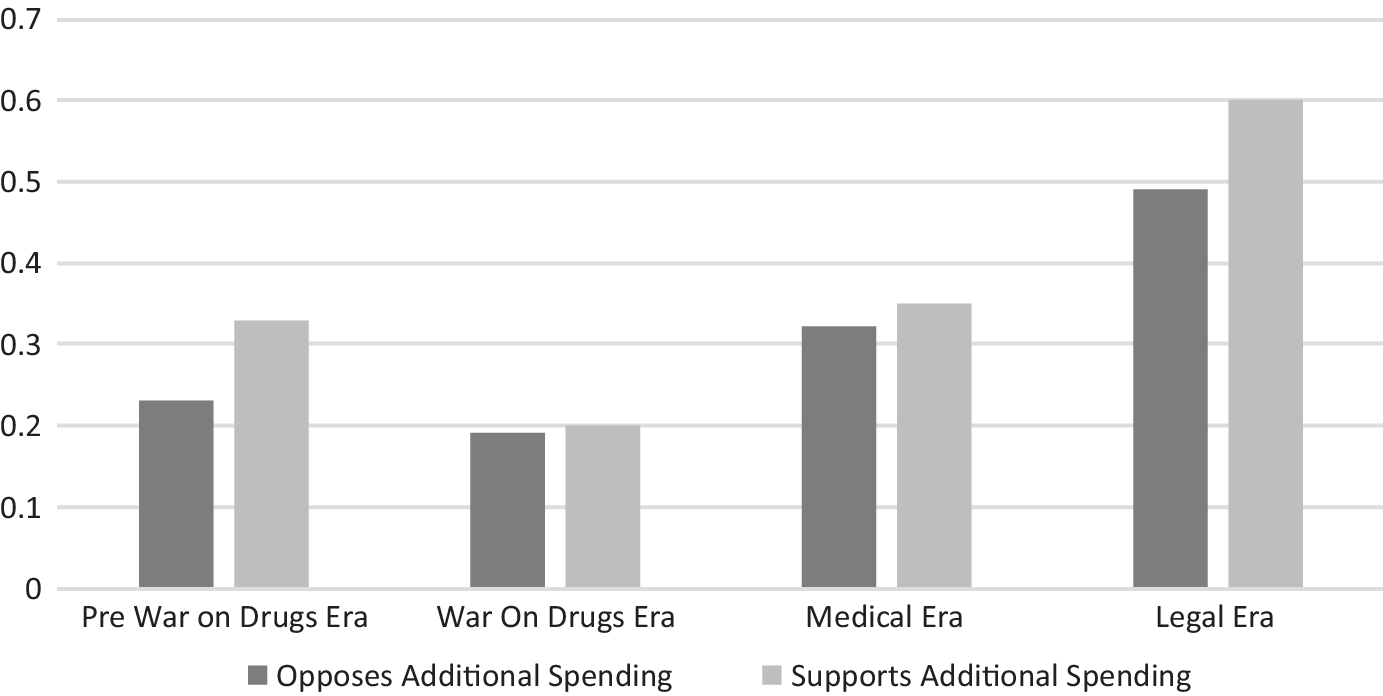

Model 3 adds the interaction of laissez-faire prejudice and era. In partial support of Hypothesis 4b, two of the interactions are statistically significant. These effects indicate that the association between laissez-faire prejudice and marijuana legalization attitudes varies across the War on Drugs, Medical Marijuana, and Legal Marijuana Eras. This pattern is displayed in Figure 3. Figure 3 shows that in the War on Drugs and Medical Marijuana Eras, adherence to laissez-faire prejudice is not associated with marijuana legalization. However, in the Legal Marijuana Era, those who oppose government spending on Black Americans are less likely to support marijuana legalization. Contrary to our expectations, laissez-faire prejudice is also associated with marijuana attitudes in the Pre-War on Drugs era.

Fig. 3. Support for Marijuana Legalization by Laissez-Faire Prejudice and Time Period

Source: GSS (1972–2019)

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Racism is like a Cadillac; they bring out a new model every year.

—Malcolm X, quoted in The Possessive Investment in Whiteness

(Lipsitz Reference Lipsitz1998, p. 183)This research examines how evolving forms of racial prejudice have shaped Whites’ attitudes towards marijuana legalization from the 1970s to today. This investigation produced two notable findings. First, consistent with our expectations, we show that both old-fashioned and laissez-faire prejudice are negatively associated with support for marijuana legalization. As discussed above, the history of marijuana prohibition was largely based on blatantly racist rhetoric that equated the use of marijuana with people of color in the United States. Given this history, the lack of research into the link between prejudice beliefs and attitudes towards marijuana is surprising. Here we demonstrate this link using nationally representative data spanning over four decades.

Second, we show that the association between racial prejudice and attitudes toward marijuana has changed over time and across birth cohorts as the racial attitudes of Americans have shifted. Specifically, our analyses revealed that the association between old-fashioned prejudice and marijuana attitudes were primarily observed among respondents from the World Wars and Baby Boomer cohorts, defined here as those born between 1901 and 1964. Among those respondents from Generation X (born between 1964 and 1980) there was no association between old-fashioned prejudice and marijuana legalization attitudes. Looking at laissez-faire prejudice we see the opposite pattern. Namely, this manifestation of racial animus has its most pronounced association with legalization attitudes among Millennial Cohort respondents (born after 1980) and in the Legal Marijuana Era (after 2012).

Past research has primarily focused on how marijuana legalization attitudes have shifted over time and have identified time period and birth cohort to be the most salient predictors of marijuana legalization attitudes (Schwadel and Ellison, Reference Schwadel and Ellison2017). This research builds on this work by showing that shifting racial attitudes also have an effect on support for legalization. Specifically, we argue that this research shows that marijuana legalization is a policy issue that Whites view through a racial lens. While more recent cohorts of Americans may have moved away from the explicit racism of the Jim Crow era, a substantial number remain opposed to government interventions to assist people of color; an attitude that correlates with opposition to legalizing marijuana. This pattern is consistent with a large body of research that shows how the nature of Whites’ prejudice and its effect in shaping racial policy attitudes has shifted over the past several decades. The result is that while overt forms of prejudice and their effects on racial policy attitudes have declined, prejudice, in the form of the subtle modern forms of racial animus, continues to animate the racial policy attitudes of Whites (Krysan Reference Krysan2000).

Recognizing the racialized nature of marijuana politics is important for understanding how and why opinions and laws surrounding marijuana are rapidly changing. For example, rather than highlighting the harm done by the War on Drugs in communities of color or the social justice aspects of marijuana legalization, marijuana legalization campaigns have hinged on promoting White middle-class entrepreneurship in the “cannabiz” to appeal to suburban voters (Schlussel Reference Schlussel2017). Whites in legal cannabis businesses are considered trailblazers, early adopters, and entrepreneurial pioneers, while Black Americans are essentially shut out from this burgeoning industry. As of 2017, Blacks owned only 4% of marijuana businesses in legal states, with 81% being owned by Whites (McVey Reference McVey2017). While a few states have established equity programs to deal with the racial disparity stemming from marijuana prohibition, most have chosen to ignore racial equity in the marijuana industry.

Moreover, limited preliminary evidence suggests that marketing campaigns for marijuana products in legal states primarily market legal cannabis in ways to appeal to hip millennials, White health conscious women, and upscale consumers, effectively painting a new norm for what it means to be a respectable marijuana user (Mabee Reference Mabee2019). We argue that these patterns coupled with the results presented here suggest that respectable marijuana use is yet another manifestation of White privilege in U.S. society. That is, we assert that as marijuana laws continue to change, White Americans, particularly middle-class Whites, will be able to use marijuana for recreational or palliative purposes whereas marijuana use by people of color may continue to be frowned upon and even criminalized. Research could easily address this possibility by using experimental designs to determine how Americans view different presentations of marijuana use.

Understanding these cultural patterns is also important because the enforcement of marijuana laws has been racialized for decades. From 2001 to 2010 the American Civil Liberties Union conducted a thorough investigation into marijuana arrests and found that Blacks were nearly four times more likely to be arrested for marijuana and while White arrest rates remained static at 192 per 100,000, Blacks arrest rates increased 32% over that time period to 716 per 100,000 (Edwards et al., Reference Edwards, Bunting and Garcia2013). Since 1992, almost half of all drug arrests have been for marijuana possession, which has had adverse effects on communities of color. Despite equal rates of marijuana use among Whites, Blacks, and Hispanics, in 2009, Blacks and Hispanics made up 83% of prosecuted marijuana cases (Provine Reference Provine2011).

Finally, the links between racial prejudice and marijuana attitudes are important to consider, as complex legal issues surrounding marijuana use are likely to arise, even if marijuana is legalized at the federal level. Namely, federal legalization will not end marijuana related arrests in states and municipalities across the country and given the links shown here, it is likely that communities of color will continue to bear a disproportionate burden. Early evidence suggests that in Colorado and Washington, where cannabis is legal, Black residents are still twice as likely as Whites to be arrested for marijuana related crimes, and Blacks are eleven times more likely to be arrested for public consumption compared to Whites in Washington D.C. (Drug Policy Alliance 2018). Moreover, federal legalization will not hinder more conservative state and local governments from creating marijuana related laws that target non-Whites. States will likely couch such efforts as ways to protect racial minorities from marijuana using paternalistic, patronizing rhetoric. In short, federal legalization will not end criminalization and given the links demonstrated here, it is likely that regions of the country with the highest levels of racial prejudice will work to enact the most restrictive marijuana policies. This line of argumentation suggests that legalization of marijuana, rather than ease the burden of mass incarceration in communities of color, could instead increase racial disparities in marijuana arrests.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Michelle Jacobs, Heather Dillaway, Zachary Brewster, and the anonymous reviewer for insightful comments on previous versions of this manuscript.