During the 2008 presidential election season, a wide variety of political commentators and analysts expressed their views on where then-Senator Barack Obama (D-IL) fell along the ideological spectrum. In the popular press, evaluations of Obama's ideological leanings varied widely. While conservative commentators were motivated to paint Obama as a far-left liberal, pundits on the left recognized the potential electoral value of the Democratic nominee being seen as a moderate, or, at the very least, as an inclusive consensus builder. Whereas conservative columnists William Kristol and David Brooks wrote, respectively, that Senator Obama was “more liberal and inexperienced than any winning presidential candidate in modern times” (Kristol Reference Kristol2008) and “the most predictable liberal vote in the Senate” (Brooks Reference Brooks2008)Footnote 1, liberal commentators Paul Krugman and Frank Rich opined in turn that Obama “looks even more like a centrist now than he did before wrapping up the nomination” (Krugman Reference Krugman2008) and that his “vision of change is not doctrinaire liberalism or Bush-bashing but an inclusiveness that he believes can start to relieve Washington's gridlock” (Rich Reference Rich2008).

Outside of the nation's editorial pages, news coverage related to Obama's ideology displayed similar variability. Article titles such as “Tracing the Disparate Threads in Obama's Political Philosophy” (Powell Reference Powell2008) and “Obama's Ideology Proving Difficult to Pinpoint: Democrats Decry a Shift to the Left, but Republicans Still See a Liberal” (Balz Reference Balz2008) typified the uncertainty and controversy involved in attempting to place Obama on the liberal-conservative dimension that structures much of American politics. In short, citizens who followed politics were exposed to a wide variety of information and opinions regarding Senator Obama's political ideology.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, on a scholarly level, differences in beliefs regarding Obama's ideological positioning were comparatively muted. Objective methods of ideal point estimation have become increasingly prominent in the academic literature on elections, institutions, and representation (Clinton, Jackman, and Rivers Reference Clinton, Jackman and Rivers2004), and scholars have used some of these methods to locate presidential candidates in ideological space. Using first dimension DW-Nominate scores, perhaps the most widely used measure of the ideologies of members of Congress (Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Poole, Rosenthal, Boche, Rudkin and Sonnet2019; Poole and Rosenthal Reference Poole and Rosenthal1991; Reference Poole and Rosenthal1985), Obama's score of −.343 placed him as the 19th most liberal senator in 2008,Footnote 2 while McCain's score of .381 was the 31st most conservative score during the same congress. Bayesian estimates of senatorial ideal points lead to similar conclusions, both in terms of Obama and McCain's rankings within the Senate and their distance from the ideological center (Jackman Reference Jackman2009).Footnote 3

As Barack Obama's presidency played out, various events occurred that had the potential to change perceptions of how liberal his policy preferences actually were. The protracted battle to pass the Affordable Care Act (ACA), for example, highlighted Obama's support for a national health care policy that was significantly more liberal than the status quo at the time, even after some of the most liberal provisions of the bill, such as a proposed insurance plan to be run by the federal government (the “public option”), were dropped prior to passage. Indeed, the ACA became popularly known as “Obamacare,” a title that Obama himself later embraced. As another example, during the 2012 presidential election contest that pitted President Obama against former MA governor Mitt Romney, income tax rates were a significant campaign issue, with Obama proposing raising marginal rates on the highest earners and Romney proposing across-the-board cuts.

Not all developments, however, highlighted Barack Obama's liberal policy positions. For example, elsewhere in this issue, Filindra et al. (Reference Filindra, Kaplan, Buyuker and Jadidi D'Ursoforthcoming 2021) note Obama's mixed record on immigration issues, and in criticizing Obama for being insufficiently progressive, prominent social critic and scholar Cornel West argued that in Barack Obama's presidency, “We ended up with a Wall Street presidency, a drone presidency, a national security presidency” (Frank Reference Frank2014). Whether citizens looked to commentary provided by political elites, kept tabs on the policies that Barack Obama championed while in office, or developed more impressionistic readings of his ideological leanings, reasons could be found to see him as a liberal, as a moderate, or even as a conservative.

RACIAL ATTITUDES, POLARIZATION, AND PERCEPTIONS OF THE UNITED STATES' FIRST BLACK PRESIDENT

In this special issue, some scholars examine the substance of presidential rhetoric and action related to race and ethnicity and describe how presidents' decisions to speak and act have affected racial and ethnic politics in the United States (Flaherty forthcoming Reference Flaherty2021; Hero and Levy forthcoming Reference Hero and Levy2021; Lieberman and King forthcoming Reference Lieberman and King2021). Others focus on how citizens' attitudes related to race and ethnicity shape the electoral prospects of candidates for the presidency, whether those candidates are members of minority racial or ethnic groups or not (Filindra et al. forthcoming, Reference Filindra, Kaplan, Buyuker and Jadidi D'Urso2021; Nelson forthcoming Reference Nelson2021). The observation that position taking on key issues can affect the support that presidents and presidential candidates receive serves to tie these two strands of research together. Elsewhere in this issue, Reference UskupUskup (forthcoming 2021) describes how President Obama's shifting position on same-sex marriage affected his standing among segments of the Black Church; in this paper, I explore perceptions of Obama's ideological positioning, the attitudes associated with those perceptions, and extent to which those perceptions may have reflected positions and actions that President Obama took while in office.

As Filindra (et al. Reference Filindra, Kaplan, Buyuker and Jadidi D'Ursoforthcoming 2021) note, the Democratic Party's historic nomination of Barack Obama for the presidency and his subsequent election to the office brought increased public and scholarly attention to the interplay of race, ethnicity, and politics in the United States. Whereas race has always played a prominent role in the nation's politics, a black American holding the nation's highest elective office meant that even largely apolitical Americans living in areas with little racial or ethnic diversity would be regularly exposed to coverage and discussion of a prominent black officeholder's policy positions and actions. Americans more attuned to politics, and perhaps especially those with particularly liberal or conservative attitudes related to race, could hardly avoid being routinely reminded that much had changed since black Americans in many parts of the country were regularly being denied the right to vote less than 50 years earlier. In the language of political psychology, and as posited by Tesler and Sears (Reference Tesler and Sears2010), Obama's candidacy in 2008 and his subsequent presidency made race a chronically accessible consideration in American politics. While many Americans celebrated the changes that paved the way for President Obama's election, many others reacted to his presidency with intense disapproval.

The highlighting of the importance of race in American politics that accompanied Obama's presidency occurred as other significant changes in the nation's politics were playing out. The American public was becoming increasingly well-sorted into distinct and antagonistic social and partisan groups (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016; Mason Reference Mason2015; Reference Mason2016; Mason and Wronski Reference Mason and Wronski2018). While the extent to which the population became more ideologically extreme is still a matter of some debate (Abramowitz and Saunders Reference Abramowitz and Saunders2008; Fiorina, Abrams, and Pope Reference Fiorina, Abrams and Pope2008; Levendusky Reference Levendusky2009; Webster and Abramowitz Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017), there is general agreement that affective polarization—the holding of increasingly negative feelings toward members of social and political outgroups—has increased substantially in the 21st century (Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Mason Reference Mason2013; Reference Mason2016; Webster and Abramowitz Reference Webster and Abramowitz2017). Moreover, it is increasingly evident that social sorting and affective polarization have important behavioral effects (Abramowitz and Webster Reference Abramowitz and Webster2016; Davis and Mason Reference Davis and Mason2016). Of particular relevance to perceptions of the Barack Obama's ideology, social and partisan sorting may be leading to a more nationalized politics in which evaluations of presidents and presidential candidates are critical to the success of candidates running for congressional, state-level, and local offices (Davis and Mason Reference Davis and Mason2016).

In light of these developments, understanding how citizens perceived the ideological leanings of the first black president may contribute significantly to our understanding of other important features of contemporary American politics. Beyond affecting the level of electoral support that he received in 2008 and 2012, the ways in which citizens developed views of Barack Obama's ideological positioning may have ramifications for the success of other African American candidates and office holders. Moreover, as Filindra et al. (Reference Filindra, Kaplan, Buyuker and Jadidi D'Ursoforthcoming 2021) note, recent scholarship has documented how voting behavior in congressional elections, partisanship, and opinion on a number of policy issues became increasingly racialized during Obama's time as president (Tesler Reference Tesler2012; Reference Tesler2015; Reference Tesler2016). Given that members of racial and ethnic minority groups are identifying increasingly strongly with the Democratic Party and that Republican Party identification among racially resentful whites increased substantially while Barack Obama was the standard-bearer of the Democratic Party (Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2017), perceptions of even white Democratic candidates may be affected by the Obama presidency.

In this paper, I examine perceptions of Barack Obama's ideology from 2006, during his time in the U.S. Senate, to 2016, during the final year of his presidency. In winning the Democratic nomination for the presidency in 2008, Obama provided social scientists with a novel opportunity to examine in detail the factors that influence how citizens perceive the ideology of an African American candidate for a major public office. Concurrent with Barack Obama's tenure on the national political stage, the administration of the Cooperative Congressional Election Studies (CCES) provided researchers with a large volume of data on perceptions of candidates and office holders. Employing both CCES and ANES data, I model major factors that affected where respondents placed Barack Obama on liberal-conservative scales.

I test four hypotheses, including the hypothesis that perceptions of Obama's positioning shifted to the left over time and the hypothesis that perceptions of his positioning became more racialized over time. I find that white Americans perceived Barack Obama to be significantly more liberal than black and Hispanic Americans. Analysis of CCES data suggests that respondents scoring higher on measures of racial resentment saw Obama as more liberal than those exhibiting lower levels of racial resentment, although analysis of ANES data is less conclusive on that front. Perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological positioning shifted leftward early in his presidency, but shifted rightward after 2010. Notwithstanding this rightward shift, Obama was perceived to be very liberal from the beginning of his presidency, and perceptions of his ideological positioning were highly racialized from the start. There is some evidence that citizens' perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological positioning became more racialized between 2012 and 2014. Moreover, placements of Hillary Clinton were racialized in 2016, suggesting that the Obama presidency may have lasting effects on the ideological stereotyping of Democratic candidates, regardless of their race.

PERCEPTIONS OF CANDIDATES' IDEOLOGIES AND THE ELECTORAL PROSPECTS OF BLACK CANDIDATES

While Barack Obama's election in 2008 made it clear that African American candidates could win electoral victories that seemed almost unthinkable just a few decades earlier, black Americans aspiring to political office often still face substantial obstacles due to their race (Krupnikov, Piston, and Bauer Reference Krupnikov, Piston and Bauer2016; Piston Reference Piston2010; Redlawsk, Tolbert, and Franko Reference Redlawsk, Tolbert and Franko2010). Obama's election to the U.S. Senate and then to the presidency are rare examples of a black candidate winning election to a major office in a majority-white constituency.

Even now, voters in majority-white districts rarely elect black candidates to serve in institutions such as Congress (Lublin Reference Lublin1997; Tate Reference Tate2003). Although the number of African American representatives in the U.S. House had risen to 39 by 2008, only four blacks represented districts in which whites comprised a majority of the voting population at that time. While blacks made up approximately 8.3% of the population in majority-white districts, only 1.0% of the 378 majority-white House districts were represented by African Americans. While some scholars argue that the electoral chances of black candidates in majority-white districts have improved in recent decades (Bullock and Dunn Reference Bullock and Dunn2003; Swain Reference Swain1995), the number of majority-white districts electing black representatives actually decreased after 2004 before rebounding modestly by 2016 and ticking up sharply 2018.Footnote 4 In short, while the electoral prospects of black candidates in majority-white districts may be improving (Lublin et al. Reference Lublin, Handley, Brunell and Grofman2020), majority-white constituencies still rarely elect black candidates.Footnote 5 Rather than being typical in terms of electoral outcomes for black candidates running in majority-white districts, Barack Obama's successes in the 2006 senatorial election in IL and the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections were clearly exceptions to the rule.

The fact that Obama overcame some of the disadvantages that typically plague black candidates, however, does not mean that race played only a minor role in the electoral contests that he won. Indeed, ample scholarship has documented the effects of race and racial attitudes on levels of support for Barack Obama. Some studies show measures of explicit racial prejudice to be strongly associated with evaluations of Barack Obama and presidential voting decisions, at least among some segments of the population (Pasek et al. Reference Pasek, Stark, Krosnick, Tompson and Keith Payne2014; Piston Reference Piston2010; Tesler Reference Tesler2016). Others document substantial effects of measures of symbolic racism, racial resentment, and other attitudes related to race on attitudes regarding Obama (Jacobson Reference Jacobson2015; Lewis-Beck, Tien, and Nadeau Reference Lewis-Beck, Tien and Nadeau2010; Pasek et al. Reference Pasek, Tahk, Lelkes, Krosnick, Keith Payne, Akhtar and Tompson2009; Reference Pasek, Stark, Krosnick, Tompson and Keith Payne2014; Schaffner Reference Schaffner2011; Tesler Reference Tesler2016; Tesler and Sears Reference Tesler and Sears2010; Tien, Nadeau, and Lewis-Beck Reference Tien, Nadeau and Lewis-Beck2012).

In attempting to determine whether racial considerations affected voters' decisions to vote for or against Obama and whether Obama's race influenced citizens' degree of affect for him and approval of his performance in office, most social-scientific studies estimate the direct effects of explicit prejudice or racial resentment on voting decisions or attitudes. As previously mentioned, the estimated effects have been substantial, but they do not exhaust the ways that racial considerations might affect attitudes towards Barack Obama or attitudes towards other black candidates and office holders. Citizens' affect for and propensity to vote for candidates may depend in part on how citizens perceive candidates' ideologies, and citizens' perceptions may be influenced by candidates' racial identities and citizens' attitudes about race.

A growing body of scholarship that draws from both experimental studies and analysis of observational data demonstrates that black candidates tend to be seen by white citizens as more liberal than ideologically similar white candidates (Jacobsmeier Reference Jacobsmeier2014; Jones Reference Jones2014; McDermott Reference McDermott1998; Visalvanich Reference Visalvanich2017). Recent research further suggests that such race-based misperceptions of black candidates' ideologies disadvantage black candidates at the ballot box (Jacobsmeier Reference Jacobsmeier2015; Visalvanich Reference Visalvanich2017).Footnote 6 Thus, understanding the factors that influence perceptions of black candidates' ideological positioning is critical to our understanding of how race affects electoral politics in the United States. Whereas some social-scientific literature dealing with race and the Obama presidency has briefly discussed how racial attitudes affected perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological positioning (Jacobson Reference Jacobson2015; Tesler Reference Tesler2016), this paper provides a more detailed examination of the factors that influenced perceptions of Obama's ideology and how his presidency may have lasting effects on perceptions of candidates' ideologies more broadly.

In many studies related to perceptions of candidates' ideologies, ideology is described in terms of coherent constellations of relatively consistent policy preferences or issue positions. While early seminal work in public opinion found ideological thinking along these lines to be quite rare among the American public (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964), subsequent work challenged that view (Achen Reference Achen1975), and more recent research demonstrates a significant degree of ideological constraint and voting based on issue positions and ideological proximity (Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2008; Jessee Reference Jessee2009; Reference Jessee2012; Joesten and Stone Reference Joesten and Stone2014). Hence, racial considerations aside, understanding factors that influence perceptions of candidates' ideological positioning are critical to understanding voting behavior.

At the same time, it has long been recognized that ideology has both a policy-based component and a component not tightly bound to policy positions. Free and Cantril (Reference Free and Cantril1967), for example, described Americans as philosophically conservative but operationally liberal. More recently, scholars have distinguished between policy-based (or operational) ideology and symbolic (or identity-based) ideology (Ellis and Stimson Reference Ellis and Stimson2012; Mason Reference Mason2018). Mason finds that identity-based ideological identification may contribute to the increasing level of affective polarization described earlier.

When it comes to ideological stereotypes of black candidates and officeholders, both policy-based ideology and symbolic ideology are potentially important. On the one hand, voters may prefer candidates who seem likely to have policy preferences similar to their own. On the other hand, voters may prefer candidates who seem to reside within the identity-based group or groups that they most closely identify with. In either case, if the race of a political figure causes citizens to perceive that figure to be more different from themselves than they would otherwise perceive that figure to be, the likelihood of those citizens voting for that figure or approving of that figure's performance in office will decrease.

HYPOTHESES

I expect that the racial identification of respondents affected where those respondents placed Barack Obama on ideological scales. More specifically, I expect that non-Hispanic white respondents placed Obama further to the left than black respondents, even when other relevant factors are controlled for. In essence, I hypothesize that non-Hispanic whites saw more ideological distance between themselves and Obama than would be expected based solely on (ostensibly) non-racial factors.

Given that Obama, while not a non-Hispanic white, was still a member of a racial out-group among Hispanic respondents, and that Hispanic respondents tend to display racial attitudes regarding black Americans more similar to the attitudes of non-Hispanic whites than blacks (Segura and Valenzuela Reference Segura and Valenzuela2010), but that Hispanics are also members of a minority ethnic group, I expect that Hispanic respondents placed Obama further to the left than black respondents, but less far to the left than white respondents. As such, I test the following hypothesis and sub-hypotheses:

• Hypothesis 1: Non-Hispanic whites saw Barack Obama as more liberal on average than members of other racial and ethnic groups.

– Hypothesis 1a: Non-Hispanic whites saw Barack Obama as more liberal on average than non-Hispanic blacks.

– Hypothesis 1b: Non-Hispanic whites saw Barack Obama as more liberal on average than Hispanic respondents.

– Hypothesis 1c: Hispanics saw Barack Obama as more liberal on average than non-Hispanic blacks.

After testing Hypothesis 1, I focus on non-Hispanic white voters, both because racial attitudes are expected to be most important as determinants of placements of Obama among white citizens and because the measures of racial resentment used in the CCES and ANES are sometimes thought to be inappropriate, or at least to tap different concepts, among black respondents.

In addition to the importance of racial identification in determining ideological placements of Barack Obama, I expect that attitudes regarding race will play an important role among white respondents. More specifically, I propose the following hypothesis:

• Hypothesis 2: White respondents scoring higher on measures of racial resentment placed Obama further to the left on average than those scoring lower on these measures.

In addition to the effects of racial attitudes, public stances and actions that President Obama took while in office may have affected how liberal citizens perceived him to be. While Obama took some actions that might be seen as reflecting a conservative or moderate ideology, I expect that between being the standard-bearer of the Democratic Party, supporting the economic “bailout” packages of 2008 and 2009, spearheading healthcare reform through the ACA, and reconfirming many of his liberal policy preferences during his 2012 campaign for reelection, Obama was seen as more liberal as his presidency progressed. In other words:

• Hypothesis 3: The mean ideological placement of Barack Obama by white respondents became more liberal over time.

Moreover, scholars have suggested that Barack Obama's election as the nation's first black president has increased the degree to which policy preference on many issues differ both by race and across levels of conservatism of racial attitudes (Tesler Reference Tesler2012; Reference Tesler2016; Tesler and Sears Reference Tesler and Sears2010). In addition to a black president being elected for the first time, events such as the rise of the birther movement have potentially increased the extent to which some citizens see black politicians as “others.” This type of racialization may affect the degree to which race and racial attitudes predict ideological placements of Barack Obama, and accordingly I test the following hypothesis:

• Hypothesis 4: The importance of racial resentment as a predictor of ideological placements of Barack Obama among white citizens increased over time.

DATA

Perceived Candidate Ideology

The subsequent analysis of perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological positioning uses data from the biennial CCES surveys conducted between 2006 and 2016 and the ANES time series surveys administered in 2008 and 2012. During the 2006 and 2008 waves of the CCES, respondents were asked to place Obama (and other candidates and office holders) on ideological scales ranging from 0 to 100, with 0 being the most liberal and 100 the most conservative placement.Footnote 7 In the subsequent waves of the CCES and both waves of the ANES used here, survey questions asked each respondent to place Barack Obama on a more standard 7-point scale ranging from more liberal to more conservative placements.

Racial Identification

I use a set of dummy variables to denote the racial identification of respondents. With non-Hispanic white respondents serving as the omitted reference category, positive coefficients on the racial identification variables for black respondents and Hispanic respondents in the regression analyses would indicate that, ceteris peribus, white citizens see Barack Obama as more liberal than members of other races do.

Respondent Ideology

A respondent's own ideological positioning could shift perceptions of a candidate's ideology either left or right. On the one hand, respondents might perceive candidates with ideologies similar to their own to be more typical, and hence more moderate, than they actually are, while also perceiving the distances between their own ideologies and those on the opposite side of the political spectrum to be greater than they actually are. This would result in a negative coefficient on respondent ideology.

On the other hand, due to projection effects, respondents may assume that candidates hold views similar to their own (Conover and Feldman Reference Conover and Feldman1989; Koch Reference Koch2002). Because respondents who perceive themselves to be to the left of Obama may tend to shift their perceptions of him to the left, while those to the right of Obama may shift their perceptions of him to the right, the coefficient on respondent ideology may be positive. In either case, as Jacoby, John Ciuk, and Pyle (Reference Jacoby, John Ciuk and Pyle2010) note, the inclusion of respondent ideology in the analysis should also account for the phenomenon of persuasion, in which respondents' begin to see themselves as more ideologically similar to candidates that they think highly of. In the 2006 and 2008 CCES data, respondent ideology is on a scale from 0 (the most liberal response) to 100 (the most conservative response). In the other years of CCES data and the ANES data, respondent ideology is measured on a 7-point scale.

Racial Attitudes

Examining the relationship between racial attitudes and perceptions of Barack Obama's ideology has the potential to shed light on the importance of what scholars have referred to as symbolic racism (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981). In short, the theory of symbolic racism suggests that whereas displays of explicit racial prejudice are no longer broadly socially acceptable, prejudice against blacks may be couched—consciously or not—in terms of conservative positions on ostensibly non-racial issues.

In describing the concept of symbolic racism, Kinder and Sanders (Reference Kinder and Sanders1996) write that “At its center are the contentions that blacks do not try hard enough to overcome the difficulties they face and they take what they have not earned. Today, we say, prejudice is expressed in the language of American individualism.” In this framework, rather than believing that blacks are biologically or innately inferior to whites, those who hold symbolically racist attitudes believe that blacks tend to have ostensibly non-racial personal attributes that are deficient in some way.

To the extent that ideological liberalism is seen by some as being in opposition to American individualism, having liberal preferences or promoting liberal policy proposals may be good examples of the sorts of negative personal attributes that those holding symbolically racist attitudes may attribute to black Americans. The tendency of black Americans to fall on the left side of the political spectrum may allow for prejudiced individuals to frame their prejudice in terms of ostensibly non-racial political preferences. While it may not be socially acceptable to vote against a candidate just because that candidate is black, it may be socially acceptable for a conservative citizen to vote against that candidate because that candidate is black and black candidates tend to be liberal.

If a given black candidate is actually as liberal as a voter thinks he or she is, this may be normatively unproblematic. However, as previously noted, there is evidence that white voters tend to see black candidates as more liberal than ideologically similar white candidates. Moreover, it may be the case that more racially conservative citizens see black candidates as more liberal than less racially conservative citizens.

While methods of measuring symbolic racism are not without controversy (Carmines, Sniderman, and Easter Reference Carmines, Sniderman and Easter2011; Feldman and Huddy Reference Feldman and Huddy2005; Zigerell Reference Zigerell2015), the racial resentment scale devised by Kinder and Sanders (Reference Kinder and Sanders1996) has been frequently employed in research on race and politics, and racial resentment continues to be a powerful predictor of policy preferences and political behavior (DeSante Reference DeSante2013; Knuckey Reference Knuckey2011; Tesler and Sears Reference Tesler and Sears2010; Tuch and Hughes Reference Tuch and Hughes2011). The 2008 and 2012 ANES surveys contain the full battery of four questions necessary to create Kinder and Sanders' scale of racial resentment.Footnote 8

Unfortunately, while the 2010, 2012, and 2014 waves of the CCES contain an abbreviated two-question battery that allows for the creation of racial resentment scales in those years, the 2006 and 2008 waves of the CCES do not include any of the questions necessary to create such a scale. For the 2006 and 2008 rounds of the CCES, a question tapping opposition to affirmative action policies is used to serve as a proxy for racial resentment. Because the responses to the affirmative action question available to respondents were different in 2006 and 2008, z-scores based on one's degree of opposition to affirmative action are used in the models when comparing 2006–2008. The four-question version of racial resentment scale can be calculated for the 2014 round of the CCES, but the two-question version of the scale is used in the 2010, 2012, and 2014 CCES models to allow for comparability over time.Footnote 9 In 2016, the CCES replaced the questions used to gauge racial resentment with four new questions tapping racial attitudes. These four questions were used to create a racial attitudes scale for the models using the 2016 CCES data.Footnote 10

Education and Political Sophistication

While much scholarship portrays citizens as politically ill-informed (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Delli Carpini and Keeter Reference Delli Carpini and Keeter1996), other research shows that many citizens are able to correctly identify the voting decisions that their representatives make on key votes (Alvarez and Gronke Reference Alvarez and Gronke1996). Moreover, politically knowledgeable citizens are more likely to be able to place candidates on ideological scales and to do so accurately (Koch Reference Koch2003; Powell Reference Powell1989; Wright and Niemi Reference Wright and Niemi1983).

While a significant percentage of respondents who are able to place candidates on 7-point scales place those candidates at reasonable positions, it is evident that some respondents provide essentially random responses, or guesses, when asked to provide candidate placements (Powell Reference Powell1989). As Powell notes, mean placements of candidates among guessers will tend to be close to a moderate 4 on a 7-point scale. Partly because levels of education are associated with guessing, I include a respondent's highest level of formal education in the analyses. Due to guessing, the mean perception of Obama's ideology among all respondents will be less liberal than we would expect it to be if guessing were not present. In the aggregate, the extent to which non-guessers correctly perceive liberal candidates to be liberal may be masked by the less liberal mean perception among guessers. The extent to which race affects the perceptions of non-guessers could therefore be underestimated if guessing were not accounted for. As Obama presumably falls to the left of “moderate” in actuality, I hypothesize that the coefficient on education will be negative.

Controlling for education is also important because higher levels of education tend to result in more accurate perception of candidates' ideologies. Furthermore, education levels vary by race, with whites having completed more years of formal education on average than blacks. Lower average levels of formal education among black citizens may result in blacks having less accurate perceptions of candidates' ideologies on average than whites. As Griffin and Flavin (Reference Griffin and Flavin2007) argue, differences in the accuracy of information that citizens have about candidates may result in black citizens being less likely than white citizens to hold their representatives accountable for congressional behavior that is at odds with constituency preferences.

As additional proxies for political sophistication, I also include in the models the age of respondents and, where available, the level of interest that respondents have in news coverage at the time of the survey. Age is expected to be associated with both higher levels of political knowledge and lower levels of guessing, as older respondents have had more experience with the political world (Powell Reference Powell1989). Interest in news is also expected to be associated with higher levels of political sophistication (Luskin Reference Luskin1990). Hence, both age and interest in news are expected to move perceptions of Barack Obama's ideology in the negative direction. It should be noted that while age may act in part as a proxy for political sophistication, it may also be the case the older white citizens tend to hold stronger stereotypes regarding the ideological positioning of black candidates.

Party Identification

As previously noted, research indicates that citizens sometimes use partisan stereotypes as informational shortcuts in evaluating the ideologies of candidates. Additionally, research in social psychology suggests that in the context of in-group/out-group situations, in-group members misperceive characteristics of out-group members for several reasons (Brewer and Kramer Reference Brewer and Kramer1985; Duckitt Reference Duckitt, Sears, Huddy and Jervis2003). One such reason is that when group boundaries are explicit, as is the case when Democratic and Republican citizens compare Democratic candidates to Republican candidates, in-group members tend to perceive differences between themselves and out-group members to be greater than they actually are. This suggests that, ceteris paribus, Democratic respondents will perceive Republican candidates to be more conservative than they actually are, and Republican respondents will overestimate the extent to which Democratic candidates are liberal.

To test for such effects, I include the partisan self-identification of respondents in the analysis. Respondents were coded as Democrats if they identified themselves as either strong Democrats, Democrats, or leaning Democratic on a 7-point scale, and as Republicans if they identified themselves as strong Republicans, Republicans, or leaning Republican. The reference category in this case consists of independents.Footnote 11

RESULTS

Consideration of ideological placements of Democratic presidential nominees over time provides a sense of roughly how liberal citizens perceived Barack Obama to be. In the 2008 ANES, the mean placement of Barack Obama was 2.96 on a 7-point scale from liberal to conservative, with 4 representing moderate, and in 2012, the mean was an even more liberal 2.65.Footnote 12 These two mean placements are the most liberal mean placements of Democratic presidential nominees since 1972, the first year that the placement questions were asked, and when George McGovern, the Democratic nominee, received a mean placement of 2.44. More recent Democratic presidents were not seen as being as liberal as Obama, with Bill Clinton being placed from 3.19 to 3.24 and Jimmy Carter being placed from 3.25 to 3.75 on average, depending on the year of the survey.

Regardless of perceptions, of course, not all Democratic nominees are equally liberal in actuality. While ideology may be multi-dimensional, the first-dimension DW-Nominate scores of Obama, Clinton, and Carter provide a measure of how liberal the revealed policy preferences of those three Democratic presidents actually were on the economic dimension that is dominant in American politics. At least on this measure, Obama was clearly the most conservative of the three most recent Democratic presidents, scoring a −.378 on a liberal-conservative scale from roughly −1 to +1, as compared to Clinton's score of −.438 and Carter's quite liberal score of −.504. While care should be taken in interpreting these scores, the standard deviation of DW-Nominate scores of members of the House within a given year tends to be roughly .5, suggesting that the actual differences in ideological location between Obama, Clinton, and Carter were substantial, with Obama clearly being the least liberal of the three. This, of course, is at odds with the perceptions of citizens, who, on average, clearly saw Obama as the most liberal of the three recent Democratic presidents. This contrast is, at a minimum, consistent with findings that black candidates tend to be seen as more liberal than is warranted by the policy positions that they take.

Bivariate analysis also suggests that the race of respondents affects perceptions of Obama's ideology. This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows the mean values of the CCES perceived ideology variable in 2008 by respondent race.Footnote 13 Mean perceptions of John McCain's ideology are provided for purposes of comparison.

Figure 1. Mean Ideological Placement of 2008 Presidential Candidates by Respondent Race (CCES).

Among non-Hispanic white respondents, the mean perception of Barack Obama's ideology was a quite liberal 22.6, while among black respondents, the mean perception was a much more moderate 41.8. The mean among Hispanic respondents was a fairly liberal 32.4. Clear differences in perceptions of Obama's ideology are apparent, then, between respondents of different racial and ethnic backgrounds.Footnote 14 On average, white respondents had the most liberal perceptions, followed by Hispanic respondents, and finally black respondents, who tended to see Obama as much more of a moderate. This result is consistent with Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c.

In contrast, perceptions of John McCain's ideology varied very little across racial groups. While white respondents gave him the most conservative placements on average, black and Hispanic respondents placed McCain almost as far to the right, and neither black nor Hispanic respondents' placements differed from those of white respondents to a statistically significant extent at the conventional p = .05 level.

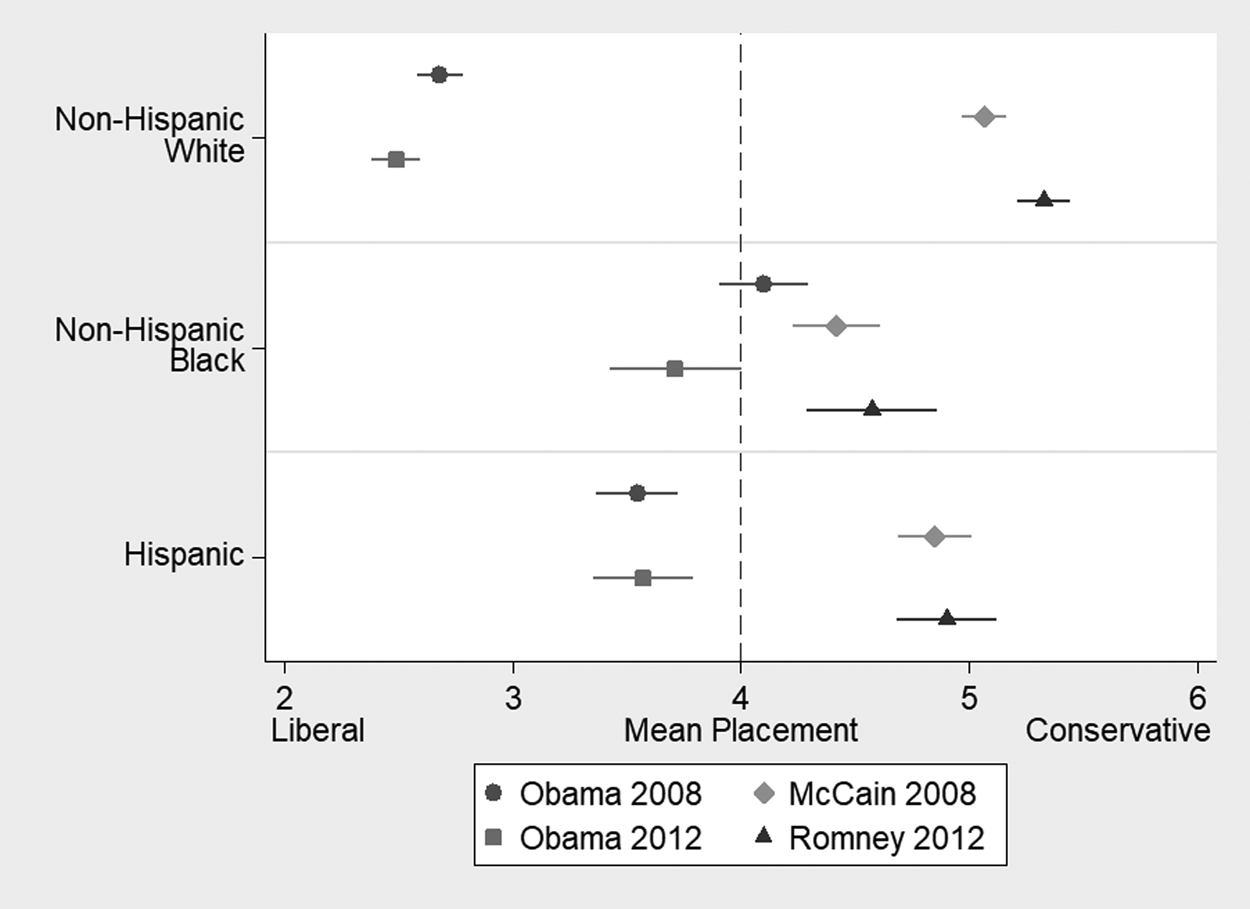

Figure 2 shows mean placements by racial group during the 2012 presidential election contest between Barack Obama and Mitt Romney. The pattern of placements of Barack Obama across racial groups is very similar to the pattern in 2008. Once again, there was much less difference in placements of the white Republican candidate across racial groups, although the mean placement of Romney by whites was a statistically significant degree further to the right than the placement of Romney by blacks. While Barack Obama is certainly not representative of all black candidates, Figures 1 and 2 are consistent with the possibility that white citizens tend to place black candidates further to the left than is warranted.

Figure 2. Mean Ideological Placement of 2012 Presidential Candidates by Respondent Race (CCES).

Mean placements of the presidential nominees during the 2008 and 2012 ANES surveys are shown in Figure 3. Due to the smaller sample sizes of the ANES surveys, the estimates are less precise. While placements of all nominees by black and Hispanic respondents tended to be somewhat closer to a moderate 4 in the ANES data, with the mean placement of Obama by black respondents in 2008 being positive but insignificantly different from zero, the results from the ANES surveys otherwise mirror those from the CCES.

Figure 3. Mean Ideological Placement of 2008 and 2012 Presidential Candidates by Respondent Race (ANES).

The difference in placements of Barack Obama between racial and ethnic groups remains strong even when controls are added to the analysis. Figure 4 presents the results of OLS regressions of placements of Barack Obama and John McCain during the 2008 CCES survey.

Figure 4. OLS Coefficients: Factors Affecting Placement of the 2008 Presidential Candidates (CCES).

When controlling for other relevant factors, black respondents placed Barack Obama 3.97 points to the right of where white respondents placed him on average, a statistically significant difference at the p = .01 level. On a scale from 0 to 100, four points is not overly large in substantive magnitude, but the coefficient is roughly half as large as the coefficient on Democrat, and partisanship is one of the most powerful predictors of placements throughout the analyses described in this paper. Hypothesis 1a, then, receives significant support, with white citizens clearly seeing Barack Obama as significantly more liberal than black citizens even when other determinants of ideological placements are controlled for.

On average, when controlling for other factors, Hispanic respondents placed Obama 1.31 points to the right of where white respondents placed him, a difference that is only statistically significant at the p = .10 level. Hispanic citizens were estimated to place Obama between white and black citizens, but the differences between Hispanic citizens' placements and placements by black and white citizens were less substantial. Hypotheses 1b and 1c, then, are less well-supported by, but still consistent with, the CCES analysis. At the same time, it is worth noting that Hispanic and black citizens viewed John McCain as being less conservative than white citizens did. Hence, respondent race is associated with the perception of even white nominees' ideologies, at least when those nominees are facing a black opponent.

As shown in Figure 5, regression results from the 2012 CCES lead to similar conclusions. With the ideological placement scale being a 7-point scale on the 2012 CCES, the coefficients are much smaller in size, but the signs and statistical significance of the coefficients from 2012 largely mirror those from 2008. One difference is that in 2012, Hispanic respondents were predicted to place Obama further to the right than black respondents, all else equal.

Figure 5. OLS Coefficients: Factors Affecting Placement of the 2012 Presidential Candidates (CCES).

Turning to Hypothesis 2, it is clear that racial attitudes, captured by opinions on affirmative action policy in 2008 and by level of racial resentment in 2012, had a substantial effect on placements of Barack Obama. As the values of the affirmative action measure range from 1 to 4, a citizen strongly opposed to affirmative action was predicted to place Obama approximately 14 points to the left of an otherwise identical citizen who was strongly supportive of affirmative action in 2008, even when factors such as partisanship and ideology are controlled for. This is particularly striking given that the dependent variable is a measure of a respondent's ideological placement of Obama, and not a measure of support for his candidacy or approval of his performance in office. The results from 2012 are similar. With the racial resentment scale ranging from 2 to 10, moving from the lowest to highest level of racial resentment would be expected to shift a citizen's placement of Barack Obama approximately .8 points to the left on the 7-point scale.

Racial attitudes had some effect on placements of John McCain and Mitt Romney, but the effects were much smaller than they were when respondents placed Barack Obama. This strongly suggests that racial attitudes were affecting placements of Obama largely because of his race; it does not seem likely that the measures of racial attitudes being employed here were mainly capturing non-racial ideological preferences. On the whole, analysis of the CCES data from 2008 and 2012 provides strong support for Hypothesis 2: citizens with more conservative racial attitudes placed Obama further to the left than those with more liberal attitudes on race.

Did perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological positioning change over time in accordance with Hypothesis 3? In 2006, Barack Obama was the junior senator from IL, and was not involved in a reelection campaign. On average, his constituents located him at rather liberal 33.2 on a liberal-conservative scale ranging from 0 to 100. By the time he was the Democratic presidential nominee in 2008, he was seen as being even more liberal, being located at 25.8 on average.Footnote 15 This leftward shift in perceptions occurred despite the fact that, at least according to DW-Nominate scores, Obama had not moved to the left, and as president, he would actually become more moderate. One might expect that if race-based ideological stereotypes affect placements of black candidates, they would do so to a greater extent in races for lower offices, where citizens tend to have less information about the actual policy positions of the candidates. This does not seem to be the case, however, when comparing perceptions of Barack Obama as a senator to perceptions of him as a presidential candidate.

As previously noted, ANES data shows that on average, citizens saw Obama as more liberal in 2012 than in 2008. While this is consistent with the idea that perceptions of Obama's ideology shifted leftward as his presidency progressed, the ANES only provides observations at those two points in time. The CCES provides more datapoints on mean perceptions of Barack Obama's ideology over time, with the surveys from 2010 to 2016 consistently using the same 7-point scale for ideological placements. Figure 6 shows the mean placement of Obama among all white respondents in each of these years, and also shows the mean placement among white respondents by party.

Figure 6. Mean Ideological Placement of Barack Obama among White Respondents over Time (CCES).

Among all white respondents, Hypothesis 3 is clearly not supported by the CCES data, at least over the period from 2010 to 2016. On average, Obama was actually seen as somewhat more moderate in 2016 than in 2010. Among independents, however, Obama was seen as more liberal in 2014 than in both 2010 and 2012. This perception was short-lived, though; by 2016, independents placed Obama roughly where they had placed him in 2012. Hence, whereas there appears to have been a leftward shift in placements of Obama over the early years of his presidency, the CCES data indicates that this shift seems to have stopped by 2010.

Turning to the question of whether the impact of factors that affected perceptions of Barack Obama's ideology changed over time, Figure 7 presents the results of OLS regressions of ideological placements of Obama using each of the biennial CCES surveys from 2006 to 2016.Footnote 16

Figure 7. OLS Coefficients: Factors Affecting Ideological Placement of Obama among White Respondents over Time (CCES).

The regression results for 2008 are fairly similar to those for 2006, although the much larger number of respondents placing Obama on the ideological scale in 2008 allows coefficients to be estimated with much greater precision in that year. The effect of opposition to affirmative action on placements of Barack Obama was estimated to be slightly larger in 2008 than in 2006, but the difference in the size of the coefficient between the 2 years is not statistically significant. There was no substantial change in the effect of racial attitudes on placements of Obama between 2006 and 2008, at least when using opinions on affirmative action as a proxy for racial resentment.

Looking at the CCES models from 2010 to 2016, the general consistency of the results across years is notable. Did the effects of racial resentment on perceptions of Barack Obama's ideology change over time? While the coefficient on racial resentment was −.08 in both 2010 and 2012, its magnitude increased somewhat to −.10 in 2014. A pooled model that includes an interaction between the year of the survey and racial resentment confirms that the increase in the magnitude of the effect of racial resentment is statistically significant. In terms of substantive significance, a citizen with the maximum racial resentment score would be predicted to place Obama .64 units further left on the 7-point than an otherwise identical citizen displaying the lowest level of racial resentment in 2010 and 2012. In 2014, this predicted difference increased to .80 units. As a point of comparison, in 2014, holding all else equal, Republicans saw Obama as being .59 units more liberal than independents did on average, and 1.28 units more liberal than Democrats did. Interestingly, as the coefficient on racial resentment increased between 2012 and 2014, the effect of being a Republican dropped by a substantively and statistically significant amount.

As previously noted, the measure of racial attitudes used in the CCES model for 2016 differed from the measure used in the models from 2010 to 2014. Because of this, the smaller coefficient should not be interpreted as evidence that racial resentment became a weaker predictor of placements of Obama. However, in the model for 2014, a one standard deviation change in the racial resentment measure was predicted to cause a change of approximately .25 points on the 7-point placement scale, whereas in 2016, a one standard deviation change in the measure of racial attitudes was predicted to cause a change of .16 in placement. It is possible that racial attitudes overall were not as important of a determinant of placements of Obama in 2016 as they were in 2014, but it is also possible that the measure of racial attitudes used in the 2016 CCES analysis did not capture the underlying racial attitudes relevant to candidate placement as well as the racial resentment measure used for previous years.

As suggested earlier, Barack Obama's time as the first black standard-bearer of the Democratic Party could potentially also racialize ideological placements of Democratic candidates, black or white, who run for office after his presidency. To examine this possibility, a model of ideological placements of Hillary Clinton in 2016 was also estimated. The results are shown in the last column of Table A4 in the online Appendix. The effect of racial resentment on placements of Hillary Clinton in 2016 was nearly identical to its effect on placements of Obama in 2012. While it is too soon to say whether this effect is long-lasting, the results are consistent with the idea that Barack Obama's presidency resulted in a racialization of evaluations of Democratic candidates in general that remains an important influence on electoral behavior in the United States. The results also mesh well with findings, reported in this issue, that racial resentment was associated with vote choice in the 2016 election contest between Clinton and Donald Trump and with voting intentions for the 2020 presidential election, even when xenophobia, sexism, and strength of white identity were controlled for (Filindra et al. Reference Filindra, Kaplan, Buyuker and Jadidi D'Ursoforthcoming 2021).

Before examining differences in the factors that affected placements of Obama across years in more detail, regression results from the 2008 and 2012 ANES surveys are shown in Figure 8 and described below.

Figure 8. OLS Coefficients: Factors Affecting Ideological Placement of Obama among White Respondents (ANES).

Again, the estimated effects of the independent variables are generally quite similar across years, especially when one considers the relatively small sample size of the 2008 survey as compared to the model for 2012, which uses the full sample of respondents from both face-to-face interviews and internet-based surveys. In contrast to the CCES models, however, the coefficient on racial resentment, while in the expected direction, is not statistically significant in the 2008 model and only significant at the p = .10 level in the 2012 model. Hence, while Hypothesis 2 is strongly supported by the CCES data, it receives only modest support from the analysis of ANES data. It is not clear what accounts for the difference in findings between the CCES analysis and ANES analysis.

One possibility is that a minor difference in wording between the CCES and ANES ideological placement questions account for at least part of the difference. In the CCES surveys, the most liberal and most conservative placements available are “Very Liberal” and “Very Conservative,” respectively. In the ANES surveys, however, the most liberal and conservative placements available are “Extremely Liberal” and “Extremely Conservative.” The word “Extreme” may make some respondents hesitant to place candidates at 1 or 7 on the 7-point scale. If respondents who displayed higher levels of racial resentment in the ANES would have been more likely to place Barack Obama at 1 on the scale if 1 had represented “Very Liberal” rather than “Extremely Liberal,” it is conceivable that the coefficients on racial resentment in 2012 would have been larger. In comparing the distribution of placements of Obama in the 2012 CCES to placements in the 2012 ANES, it is indeed the case that respondents were significantly more likely to place Obama at 1 on the CCES survey.Footnote 17 While over 41% of CCES respondents placed Obama at the most liberal location available, only 26% of ANES respondents placed Obama at the most liberal location.

The ANES surveys also provided the opportunity to incorporate additional measures of racial attitudes into the regression analyses. Respondents were asked to rate members of different races on thermometer scales, and the difference between respondents' ratings of whites and blacks was used as one such measure. Respondents were also asked to what extent members of various racial groups are hardworking, and the difference between respondents' evaluations of whites and blacks was used as a second measure. When included in the 2008 and 2012 ANES regressions, neither of the coefficients on these variables is statistically significant in either model.Footnote 18

Whereas the CCES was first administered in 2006, and hence the CCES could not be used to examine whether perceptions of Democratic presidential candidates had already been racialized prior to Barack Obama winning the presidency, the ANES allowed for such analysis. Results of models of ideological placements of the Democratic presidential candidates in 2000 and 2004 are shown in Table A5 in the online Appendix along with the models of placements of Barack Obama and of Hillary Clinton in 2016. Racial resentment did not have a statistically significant relationship with placements of Al Gore in 2000 or John Kerry in 2004. However, as was the case in the CCES analysis, the effect of racial resentment on placements of Hillary Clinton was extremely similar to its effects on placements of Obama in 2012.

Almost all of the results presented up to this point indicate that, in addition to racial resentment, partisan identification of respondents is a very important determinant of perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological positioning. Partisanship may be part of the reason that the importance of racial resentment in determining placements ticked upward between 2012 and 2014 according to the CCES analysis. Figure 9 presents OLS results for models of placements of Barack Obama in 2012 and 2014, with the sample split according to the partisanship of respondents.

Figure 9. OLS Coefficients: Factors Affecting Ideological Placement of Obama among White Respondents by Party over Time in 2012 and 2014 (CCES).

While it should not be surprising given the in-group/out-group dynamics associated with partisanship, perhaps the most interesting thing to note in Figure 9 is that racial resentment is a substantially stronger predictor of placements of Obama among independents than it is among either Democrats or Republicans. This does not account for the uptick in the importance of racial resentment in the full sample between 2012 and 2014, though: analysis using interaction terms indicates that significant increases in the coefficient on racial resentment occurred among both Democrats and Republicans between 2012 and 2014, but not among independents.Footnote 19

It is unclear why racial resentment was a stronger predictor of perceptions of Barack Obama's ideology in 2014 than it was in 2012. The CCES and ANES do not provide the data necessary to test for connections between many major events that took place during Obama's presidency and the effects of racial resentment. Between 2012 and the midterm elections of 2014, however, George Zimmerman was acquitted of murder charges in the death of unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin, African-American citizen Eric Garner was killed by a police officer using a chokehold in NY City, and massive protests erupted following the death of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown at the hands of police in Ferguson, MO. As these events unfolded, the Black Lives Matter movement also rose to national prominence. It is conceivable that perceptions of the ideological location of Barack Obama, the nation's first black president, were further racialized by developments such as these.

Overall, it seems likely that Barack Obama's election to the presidency and his subsequent reelection occurred in spite of the fact that race-based stereotypes of his ideological positioning disadvantaged him. While scholars were generally skeptical that his election altered the fundamental nature of racial and ethnic politics in the Unites States, the importance of both race-based ideological stereotypes and racial resentment in determining perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological positioning throughout his presidency serves as yet another piece of evidence that his election did not, as some commentators suggested, usher in a post-racial era of American politics.

CONCLUSION

The preceding analysis demonstrates that a variety of factors had an impact on citizens' perceptions of Barack Obama's ideological location from his time as a senator through the second term of his presidency. While partisanship had a substantial effect on placements of Obama and factors such as education and interest in public affairs worked in the expected directions, racial attitudes also had a major impact on how liberal citizens perceived Obama to be. The relationship between racial resentment and ideological placements of Barack Obama comports well with theories of symbolic racism. Even in presidential elections, where attentive voters have no shortage of accessible information about the policy positions staked out by the major-party nominees, a candidate's race can have substantial effects on perceptions of that candidate's ideological orientations. Furthermore, elsewhere in this issue, Reference NelsonNelson (forthcoming 2021) reports that racial resentment is linked to candidate preference when electability is seen as an issue in primary elections; future research should examine relationships between perceived ideological positioning and perceived electability.

The race-based ideological stereotyping of Obama was similar in many ways to ideological stereotyping of black candidates for other offices. It is important to note, however, that the chronic accessibility of race as a consideration in political evaluations during Barack Obama's presidency had the potential to strengthen race-based ideological stereotypes. Moreover, recent scholarship has suggested that public opinion on various issues became increasingly racialized after Barack Obama became president. The results presented here indicate that racial resentment was associated with placements of Hillary Clinton in 2016, but not with placements of Al Gore in 2000 or John Kerry in 2004. This suggests that Obama's candidacy in 2008 and his subsequent presidency may have lasting effects on evaluations of Democratic candidates for the presidency and other offices, even if those candidates are not black.

In the case of Barack Obama, the perceived ideological distance between Obama and a given voter had a substantial effect on that voter's likelihood of casting a vote for him, both in 2008 and 2012, even when accounting for partisanship and the direct effects of racial attitudes (Knuckey and Kim Reference Knuckey and Kim2015). Hence, Obama's race seems to have had both direct and indirect effects on voting decisions during each of his runs for the White House. It is important to note that if candidates' perceived ideologies are included in models of voting behavior while race-based misperceptions of candidates' ideologies are not accounted for, the total effect of the race of candidates on voting decisions will likely be underestimated.

Of the four hypotheses tested here, two received substantial support and two received more limited support. On average, white citizens saw Obama as being more liberal than members of other racial and ethnic groups did. Moreover, white citizens holding more conservative racial attitudes placed Obama further to the left than less racially conservative white citizens. There is some evidence that ideological placements of Barack Obama became more racialized between 2012 and 2014, but such placements were racialized even in 2006. While placements of Barack Obama appear to have shifted leftward early in his presidency, citizens viewed him as less liberal in 2016 than they did in 2010.

More generally, understanding how citizens form perceptions of candidates' ideologies is an important part of developing a more complete understanding of voting behavior. The perception of ideologies is also an important determinant of the degree of congruence between the policy preferences of citizens and the policy positions of the candidates that they elect. Citizens that have more accurate perceptions of candidates' ideologies are better equipped to vote for candidates with preferences similar to their own, and less likely to rely on potentially misleading racial stereotypes in making voting decisions. Unfortunately, the evidence presented here suggests that such normatively troubling stereotypes likely kept some voters from casting votes for Barack Obama in 2008 and 2012.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2020.26