Introduction

Tonsillectomy is a commonly performed surgical procedure, with an estimated 577 000 paediatric and 225 000 adult procedures performed every year in the USA.Reference Cullen, Hall and Golosinskiy1 While the actual procedure itself is one that an otolaryngologist can perform relatively safely and quickly, the healing process results in a few uncomfortable weeks for most patients. Tonsillectomy is associated with the risk of complications such as pain, dehydration, wound infection and secondary haemorrhage. Post-operative post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage occurs at an estimated rate of 3 per cent in paediatric patients and 6 per cent in adults. Dehydration presentations occur in approximately 4 per cent of paediatric patients and 2 per cent of adults. Presentations for pain occur in 2 per cent of paediatric patients and 11 per cent of adults. Presentations for infection or fever occur in 1 per cent of paediatric patients and 6 per cent of adults.Reference Curtis, Harvey, Willie, Narasimhan, Andrews and Henrichsen2

Despite this, very little has been published on wound healing after tonsillectomy. Thus, clinicians have limited evidence on how to direct therapies to improve tonsillectomy wound healing. Better knowledge in this area may lead to improved evaluation of adjunctive therapies that potentially improve the post-operative experience. This could reduce the wound healing complications that occur secondary to tonsillectomy, and prevent the large associated healthcare costs.

This article summarises the available literature surrounding wound healing post tonsillectomy, including the stages of healing, experimental models for assessing healing (in animals and humans) and the various factors that affect wound healing.

Materials and methods

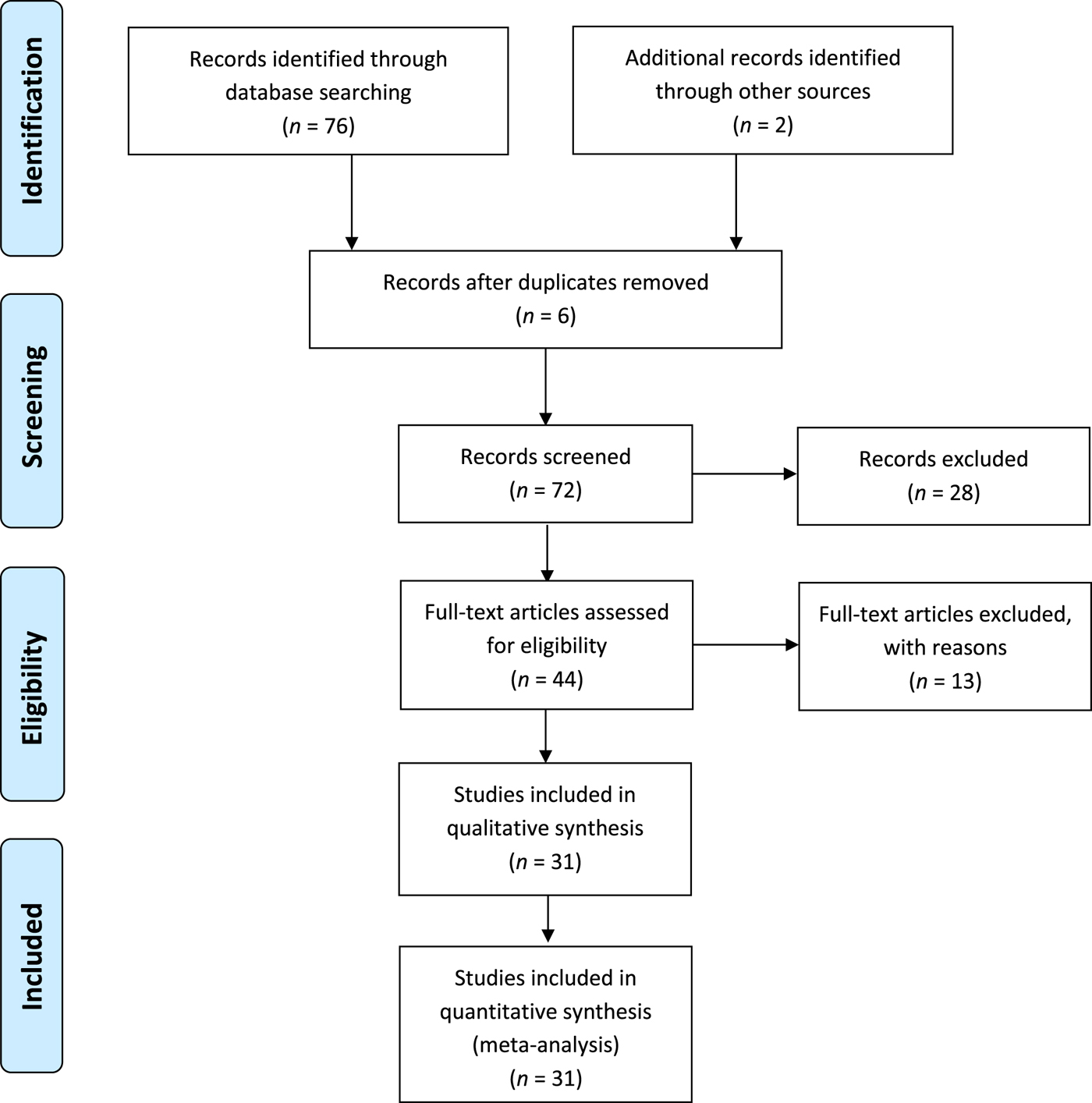

The review strategy is summarised according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) guidelines (Figure 1).Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman3 An Ovid Medline literature search was conducted to identify relevant publications published between January 1966 and September 2017, using the search terms ‘tonsillectomy’ or ‘tonsil’ and ‘wound healing’ (search performed on 25th September 2017).

Fig. 1. The review strategy summarised according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (‘PRISMA’) guidelines.Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman3

Seventy-six abstracts were initially found. The title and abstract of the articles were assessed for their potential relevance. The full text of relevant articles that focused on an objective assessment of tonsillectomy wound healing were retrieved. The references of all publications identified as relevant were manually searched for further potentially relevant titles. This resulted in two additional articles. Only articles written in English were included (26 studies were excluded). Six abstracts were duplicates and were therefore excluded. The full text of two articles was not available. The full text of the remaining 44 articles was retrieved and assessed. A further 13 studies were excluded because they were not relevant to the topic. Finally, 31 articles that objectively assessed tonsillectomy wound healing were included for analysis in this review.

Results

The various animal and human models assessing wound healing post tonsillectomy are summarised in Table 1. Prior animal studies have primarily evaluated the effects of various surgical instruments such as lasers and electrosurgical devices on oral wound healing.Reference Isaacson4 The assessment of tonsillar fossae healing has been described at macroscopic (direct examination)Reference Kataura, Doi and Narimatsu5 and microscopic levels (punch biopsies).Reference Kataura, Doi and Narimatsu5, Reference Johnson, Vaughan, Derkay, Welch, Werner and Kuhn6 Experimental models in humans have primarily evaluated healing through subjective direct clinical examination of the tonsillar fossae,Reference Park, Kim, Kim, Yeon, Shim and Lee7–Reference Elwany, Nour and Magdy32 serial photography of the areaReference Mat, Abdullah and Salim33, Reference Isaacson34 or using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).Reference Heywood, Khalil, Kothari, Chawda and Kotecha35

Table 1. Summary of methods used to evaluate tonsillar fossae healing in different experimental models

VAS = visual analogue scale; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging

Discussion

Healing stages

The healing of oral mucosal wounds post tonsillectomy is an area that has been poorly studied. At a macroscopic level, healing within the tonsillar fossae occurs via secondary intention. It involves keratinised squamous epithelium healing over a wound bed composed of muscle, and any remnant tonsillar lymphoid tissue in the case of partial tonsillectomy. This pattern of healing is thought to be similar in human skin, but occurs more rapidly and is less likely to scar.Reference Isaacson4, Reference Isaacson34 The pattern is also similar to that observed in canine and porcine oral wound models.Reference Isaacson34 The timeframe and processes that occur at these various stages can be sub-divided into early, intermediate and late phases of healing.

Most macroscopic evaluations of post-tonsillectomy wounds have been in humans, while histological studies have relied on canine tonsil wounds or surrogate models in other species.Reference Kataura, Doi and Narimatsu5, Reference Johnson, Vaughan, Derkay, Welch, Werner and Kuhn6

Early stage

At the early, inflammatory phase of healing (within 24–48 hours), evaluation at a macroscopic level reveals soft tissue oedema, inflammatory exudate and uvula oedema.

Evaluation at a microscopic level within the first 24 hours reveals soft tissue oedema involving the uvula, tonsillar pillars and tongue.Reference Isaacson34 This occurs as part of the inflammatory cascades triggered by the surgical removal of the tonsil (regardless of the technique used), venous engorgement from compression of the tongue by the tonsillectomy gag, and mucosal damage from retractor edges.Reference Isaacson36 Exposed nerve fibres and muscle fibre injury within the open pharyngeal wound may result in pain.Reference Cohen and Sommer37 The inflammatory response is compounded by the presence of commensal bacteria within the oral cavity, causing a fibrinous clot containing inflammatory cells and bacteria to form in the tonsillar fossae.Reference Johnson, Vaughan, Derkay, Welch, Werner and Kuhn6, Reference Isaacson34, Reference Isaacson36 Granulation tissue forms underneath this. The mucosa lining the tonsillar pillars begins to contract.Reference Isaacson34

Intermediate stage

The intermediate, proliferative phase (at day 5 to approximately day 14) encompasses the time until epithelialisation has occurred across the whole wound.

Macroscopically, by day 5, white material fills the tonsil fossae, which can be removed easily. This has previously been termed a ‘fibrinous clot’, but it has not been proven to contain fibrin or haemostatic clot products. By day 7, the peripheral epithelial edges seem to be in-growing, with pink mucosa. By day 9, the pink epithelial edges are covering larger areas. There are very little white debris remnants in the centre of the wound. As the pink, normal mucosa of the oral cavity epithelialises over the wound area, it gradually replaces the areas containing white material. By day 12, the pink mucosa almost completely covers the entire tonsil wound bed.

Microscopically, angiogenesis within the tonsillar fossae commences from pre-existing vessels in the extracellular matrix, facilitating granulation tissue formation.Reference Couto, Ballin, Sampaio, Maeda, Ballin and Dassi38 The granulation tissue further proliferates within the tonsillar fossae, often protruding beyond the pillars by day 5.Reference Isaacson34, Reference Isaacson36 Continued oropharyngeal epithelial ingrowth from the periphery and epithelial contracture results in separation of the fibrinous clot by day 7, exposing the underlying granulation tissue,Reference Isaacson34, Reference Isaacson36 often coinciding with a period of increased risk of secondary haemorrhage.Reference Isaacson36

Late stage

The late, remodelling phase (after approximately day 14) occurs once epithelialisation is complete.

Macroscopically, by day 17, full epithelialisation has occurred. Continued ingrowth of advancing epithelium leads to coverage of most of the tonsillar fossae by day 12, commencing the simultaneous involution of the vascular stroma.Reference Isaacson34 The tonsillar fossae appear to have a normal epithelial lining by approximately day 17 as a result of coverage by a thickened layer of epithelium.Reference Isaacson34

Models of assessment

Few animal and human experimental models for assessing oral wound healing exist. The vast majority of post-tonsillectomy complications, such as pain, reduced oral intake and secondary haemorrhage, occur during the various phases of healing. Measures to minimise the occurrence and severity of these complications may rely in part on a clinician's ability to adequately assess wound healing. We discuss a summary of findings within the literature surrounding the various methods employed to assess wound healing post tonsillectomy.

Human models

Experimental models in humans that have investigated wound healing post tonsillectomy have almost exclusively evaluated the macroscopic appearance of the tonsillar fossae. This review did not identify any studies that have examined the actual wound site at a histological level. Because of the lack of histological evidence, most of the understanding of human tonsillar wound healing is based on the macroscopic appearance.

The vast majority of studies gauge the area of epithelialisation within the healing tonsillar fossae as a marker of wound healing. The most common approach described in the literature is to estimate epithelialisation by direct clinical examination of the oral cavity,Reference Kara, Erdogan, Altinisik, Aylanc, Guclu and Derekoy8–Reference Ozcan, Altuntas, Unal, Nalca and Aslan16 or fibre-optic nasopharyngoscopic evaluation of the tonsillar fossae by a clinician.Reference Vaiman, Eviatar, Shlamkovich and Segal17 Other studies have utilised clinical photography to estimate the area of healing by obtaining either macroscopicReference Isaacson34 or endoscopic photographs.Reference Park, Kim, Kim, Yeon, Shim and Lee7, Reference Mat, Abdullah and Salim33

The thickness of the presumed fibrinous clot or amount of wound exudate present within the healing tonsillar fossae has also often been cited as a surrogate marker of tonsillectomy wound healing. Most of these studies utilise a four-pointReference Mozet, Prettin, Dietze, Fickweiler and Dietz21 or five-point grading system (i.e. full slough = 0 per cent healed; no slough = 100 per cent healed).Reference Celebi, Tepe, Yelken and Celik18, Reference Ragab20 Other studies utilised the interpretation of a single clinician based on examinations conducted on designated days post-operatively (e.g. appointment at day 7 post tonsillectomy).Reference Hahn, Rungby, Overgaard, Moller, Schultz and Tos22, Reference Cook, Murrant, Evans and Lavelle24 One study used the absolute size of the slough present as an arbitrary indicator of healing rate.Reference Tepe, Celebi, Oysu and Celik19 Another study simply used the absolute presence or absence of slough as a marker of healing.Reference Akbas, Pata, Unal, Gorur and Micozkadioglu23

Visual analogue scales (VASs) have frequently been utilised by authors to assess wound healing. The most commonly used method has been described by Magdy et al.Reference Magdy, Elwany, el-Daly, Abdel-Hadi and Morshedy31 and others.Reference Hanci and Altun26, Reference Aksoy, Ozturan, Veyseller, Yildirim and Demirhan27, Reference Elwany, Nour and Magdy32 Mucosal erythema, oedema, fossae whitening and wound healing (utilising size of slough as a surrogate marker) were graded as being absent, present or severe (scores of 0, 1 or 2, respectively).Reference Magdy, Elwany, el-Daly, Abdel-Hadi and Morshedy31 The wound healing scores were then recorded at each follow-up appointment. Other studies have used similar VASs, employing various permutations of clinical examination findings, such as the amount of tonsillar slough, degree of mucosal oedema and amount of epithelial regrowth.Reference Orlowski, Lisowska, Misiolek, Paluch and Misiolek28, Reference Auf, Osborne, Sparkes and Khalil30 The authors of one study assessed wound healing through the use of a VAS by having a single examining clinician compare the degree of granulation and epithelialisation within the tonsillar fossae at various days of follow up.Reference Aydin, Taskin, Altas, Erdil, Senturk and Celebi25 Another study simply compared the percentage of ‘redness’ and ‘whiteness’ within the tonsillar fossae as a marker of wound healing.Reference Windfuhr, Sack, Sesterhenn, Landis and Chen29

Magnetic resonance imaging has also been used in peri-operative assessments, in an attempt to characterise the appearance of inflammatory lesions produced by bipolar radiofrequency volumetric tissue reduction within the tongue base, soft palate and via tonsillectomy.Reference Heywood, Khalil, Kothari, Chawda and Kotecha35 The authors were able to demonstrate sequential changes in the appearance (size and signal intensity) of the inflammatory lesions on follow-up MRI.Reference Heywood, Khalil, Kothari, Chawda and Kotecha35

Animal models

Experimental animal models have primarily explored the impact of different surgical instruments on wound healing in the oral cavity.Reference Isaacson4 Similarly to human models, wound healing assessment after a tonsillectomy has involved direct examination of the tonsillar fossae. Experimental animal models have, however, also been able to evaluate wound healing tonsillar fossae at a microscopic level via punch biopsies conducted at various post-operative days.Reference Kataura, Doi and Narimatsu5, Reference Johnson, Vaughan, Derkay, Welch, Werner and Kuhn6 In an attempt to provide an objective means to evaluate epithelial wound healing, the authors of one study proposed a novel five-point histological mucosal wound healing grading scale, in which scores of 0 (healed), 1 or 2 (inflamed) were assigned for histological features observed from the biopsy specimens, such as inflammatory surface crust, vessel wall necrosis, intact surface epithelium, neutrophilic infiltrate and myofibroblast proliferation.Reference Johnson, Vaughan, Derkay, Welch, Werner and Kuhn6

Factors affecting wound healing

Wound healing after tonsillectomy is an area that has been poorly reported. When evaluated in studies, it is often assessed in relation to other outcomes such as pain and secondary haemorrhage following tonsillectomy. Furthermore, the absence of a standard method of evaluating wound healing after tonsillectomy leads to variable reporting within the literature.

Technical factors

A summary of the statistically significant findings from studies evaluating differences in wound healing with various tonsillectomy techniques is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Findings from studies investigating the impact of surgical technique on wound healing in tonsillectomy

CO2 = carbon dioxide; KTP = potassium titanyl phosphate

Several studies have suggested that patients who undergo cold dissection tonsillectomy experience reduced tonsillar fossae healing time. It has been proposed that electrocautery methods produce high temperatures, which cause more damage to adjacent soft tissue, prolonging healing time.

An experimental canine model suggested that microdebrider intracapsular tonsillectomy resulted in quicker healing than electrocautery.Reference Johnson, Vaughan, Derkay, Welch, Werner and Kuhn6 At a microscopic level, that study found that this technique resulted in: higher rates of surface crust absence (at post-operative days 3 and 9), higher rates of intact surface epithelium (at post-operative days 3, 9 and 20), an absence of vessel wall necrosis, and slightly lower levels of neutrophilic infiltrate and myofibroblast proliferation (at post-operative days 3 and 9). The authors proposed that the spared tonsillar capsule acts as a ‘biological dressing’, which allows for improved healing.Reference Johnson, Vaughan, Derkay, Welch, Werner and Kuhn6

Other experimental animal models investigating the impact of surgical techniques on oral wound healing have suggested that cold steel dissection minimises tissue damage to surrounding structures, allowing for quicker healing.Reference Sinha and Gallagher39 Conversely, experimental animal models have shown that electrocautery and laser techniques used within the oral cavity cause more damage to collateral structures, delaying tissue healing.Reference Liboon, Funkhouser and Terris40

One study compared three methods of intra-operative haemostasis during cold dissection tonsillectomy; namely, gauze packing, bipolar electrocautery and local anaesthetic infiltration.Reference Hahn, Rungby, Overgaard, Moller, Schultz and Tos22 The authors found that tonsillar bed healing was delayed in the diathermy group (p = 0.04). Another study compared two types of tonsillar fossae packing (gauze swab and alginate swab) in terms of intra-operative haemostasis, and found no difference in the rate of post-operative healing.Reference Sharp, Rogers, Riad and Kerr13

FloSeal (Baxter, Deerfield, Illinois, USA) is a haemostatic agent containing human-derived thrombin. When in contact with a bleeding site, it forms a stable clot by converting fibrinogen into a fibrin plug. In a study comparing the effect of intra-operative haemostasis achieved via bipolar electrocautery or topical administration of FloSeal, patients in the FloSeal group showed significantly quicker wound healing throughout the post-operative observation period (p < 0.013 on days 1–5, 10 and 20).Reference Mozet, Prettin, Dietze, Fickweiler and Dietz21 Another study compared the effect of topically applied (spray method) fibrin glue (haemostatic and bacteriostatic agent) with that of electrocautery (bipolar or monopolar) on tonsillectomy wound healing.Reference Vaiman, Eviatar, Shlamkovich and Segal17 While the authors of the study reported that patients in the fibrin glue group experienced quicker healing, no statistical evidence was provided to corroborate this finding.Reference Vaiman, Eviatar, Shlamkovich and Segal17

Co-morbidities

Untreated laryngopharyngeal reflux has been previously shown to significantly slow wound healing after tonsillectomy (p = 0.016 at day 7, and p = 0.029 at day 14).Reference Elwany, Nour and Magdy32 The authors suggested that the proteolytic effect of gastric reflux contents, previously shown to cause significant damage to mucosal epithelium in other sites such as the oesophagus, could similarly slow healing by damaging the vulnerable healing tissue within the tonsillar fossae.Reference Elwany, Nour and Magdy32, Reference Tobey, Hosseini, Caymaz-Bor, Wyatt, Orlando and Orlando41

Adjunctive treatment

Patients who had autologous serum topically administered to a single tonsillar fossa (intra-operatively, and then at 8 and 24 hours post-operatively) experienced accelerated epithelialisation within the same tonsillar fossa compared to the contralateral side (p = 0.008 on day 5, and p = 0.002 on day 10).Reference Kara, Erdogan, Altinisik, Aylanc, Guclu and Derekoy8 The authors proposed that the presence of epitheliotropic factors within the autologous serum facilitated more rapid healing on the ipsilateral side.Reference Kara, Erdogan, Altinisik, Aylanc, Guclu and Derekoy8 They also suggested that the topical administration of autologous serum conferred a local bacteriostatic response due to the presence of antimicrobial substances such as immunoglobulin G and lysozyme.Reference Kara, Erdogan, Altinisik, Aylanc, Guclu and Derekoy8

Only two studies have objectively assessed the impact of antibiotic administration on tonsillectomy wound healing.Reference Akbas, Pata, Unal, Gorur and Micozkadioglu23, Reference Orlowski, Lisowska, Misiolek, Paluch and Misiolek28 Patients who were given prophylactic oral cefuroxime experienced slower healing, by having thicker slough (p = 0.037 on day 3) and more mucosal swelling (p = 0.030 on day 3, and p = 0.036 on day 7).Reference Orlowski, Lisowska, Misiolek, Paluch and Misiolek28 The authors of that study suggested that this may have been because the patients who did not receive antibiotics experienced less post-operative pain and swallow dysfunction, and thus had quicker healing.Reference Orlowski, Lisowska, Misiolek, Paluch and Misiolek28 In another study investigating the effect of fusafungine (an antibiotic with an anti-inflammatory agent) in a spray formulation on tonsillectomy wound healing, patients who were administered the spray experienced a quicker healing process when assessed post-operatively (p = 0.031 on day 10, and p = 0.001 on day 14).Reference Akbas, Pata, Unal, Gorur and Micozkadioglu23

Sucralfate is a cytoprotective agent that works by forming a ‘barrier’ over wounds.Reference Siupsinskiene, Zekoniene, Padervinskis, Zekonis and Vaitkus42 It is effective in treating skin ulcers, burns, and disease processes resulting in mucosal damage (such as gastritis and peptic ulcer disease).Reference Siupsinskiene, Zekoniene, Padervinskis, Zekonis and Vaitkus42 Two prior studies assessed the impact of topical sucralfate on tonsillectomy wound healing.Reference Freeman and Markwell15, Reference Ozcan, Altuntas, Unal, Nalca and Aslan16 Patients were asked to gargle the medication before swallowing it. When compared to placebo, neither study found sucralfate to be beneficial in tonsillectomy wound healing.Reference Freeman and Markwell15, Reference Ozcan, Altuntas, Unal, Nalca and Aslan16

Hyaluronic acid is a glycosaminoglycan that is found in the various parts of the human body (e.g. extracellular matrix of the skin).Reference Hanci and Altun26 It is a growth factor that is naturally secreted during the wound healing process.Reference Hanci and Altun26 Patients in one study had 1 ml of PureRegen Gel Sinus (hyaluronic acid gel; BioRegen Biomedical, Hamburg, Germany) topically applied intra-operatively to a single tonsillar fossa; healing of this tonsillar fossa was quicker compared to the contralateral side (p < 0.001 at day 14).Reference Hanci and Altun26

Dexpanthenol is an alcoholic analogue with moisturising properties.Reference Celebi, Tepe, Yelken and Celik18 Patients in one study who received dexpanthenol pastilles post-operatively experienced less pain and quicker wound healing on every day they were assessed (p < 0.05 on days 1, 3, 7 and 14).Reference Celebi, Tepe, Yelken and Celik18

It has been shown that honey stimulates monocytes to release mediators that are involved in the regulation of the inflammatory cascade and healing.Reference Tonks, Cooper, Price, Molan and Jones43 These mediators may promote the formation of granulation tissue in wounds.Reference Mat, Abdullah and Salim33 Patients in one study who received tualang honey (Federal Agriculture Marketing Authority, Kedah, Malaysia) intra-operatively (2–3 ml administered topically to tonsillar fossae) and post-operatively (4 ml consumed orally thrice daily for 7 days) experienced significantly quicker wound healing on every day they were assessed (p < 0.001 on days 1, 3, 7 and 14).Reference Mat, Abdullah and Salim33

Two previous studies have objectively evaluated the impact of prednisolone on tonsillectomy wound healing. The intra-operative injection of prednisolone (20 mg) into the base of both tonsillar fossae did not produce any substantial difference in wound healing for patients in that study.Reference Anderson, Rice and Cantrell14 In a different study, both adult and paediatric patients given a 7-day course of oral prednisolone (0.25 mg/kg once daily) experienced quicker re-epithelialisation of their tonsillar fossae (p < 0.001 on days 7 and 14).Reference Park, Kim, Kim, Yeon, Shim and Lee7

Dietary modification

A single study that objectively evaluated the impact of three different post-tonsillectomy diets (‘rough foods’, ‘soft foods’ and ‘no specific advice’) on wound healing found no statistically significant effect of diet on wound healing.

Limitations

As this is a literature review, we are limited by the past research in this area. Given the lack of human research in this area, assumptions are made that mammalian wound healing is similar in animal models.

Conclusion

Wound healing post tonsillectomy has been poorly researched and reported. A better understanding of the wound healing process could potentially enable prevention, anticipation and management of complications that arise following surgery as part of the healing process. Most of the current experimental models in humans investigating tonsillectomy wound healing involve using serial direct clinical examinations to estimate the epithelialising area. There is a lack of validated assessment methods of tonsillar wound healing and human histological research.

Different patient and surgical factors have been shown to affect wound healing. The pre-operative management of pre-existing laryngopharyngeal reflux and the intra-operative use of gauze packing to achieve haemostasis (instead of bipolar electrocautery) both offer cost-effective means of improving wound healing post-operatively. While there is some research to suggest a role for the use of various adjunctive treatment options, such as FloSeal, Fibrin glue and autologous serum intra-operatively, along with the administration of oral prednisolone in the post-operative period, these are more expensive and have potential side effects. Further research needs to be conducted to ascertain if they are truly efficacious in improving wound healing post tonsillectomy.

Acknowledgement

Financially supported by the Garnett Passe and Rodney Williams Memorial Foundation.

Competing interests

Peter Luke Santa Maria is a listed inventor on a patent, currently owned by Stanford University, for a post-tonsillectomy wound healing treatment (US 2015/056651).