Countries with relatively strong records on gender equality and women's representation in politics tend to be less conflict-prone than those with poorer records. This empirical relationship has emerged from recent studies of gender in international relations and is quite robust.Footnote 1 These studies, however, overlook the opposite causal direction: how conflict and peace affect underlying gender inequalities. Ignoring the potential for conflict and peace to influence gender inequalities might contribute to invalid inferences when attributing a causal direction to an inequality-conflict correlation. The potential for conflict to reinforce or undermine gender norms also has ramifications for the prevalence of both gender inequality and armed conflict.

So, does war exacerbate domestic gender inequality as men are called to arms?Footnote 2 Or might war provide opportunities for women to have greater political, social, and/or economic responsibilities, as dominant narratives in the United States suggest about World War I catalyzing women's suffrage and World War II broadening women's labor force participation? Some strands of scholarship contend that war opens up opportunities for women's empowerment, while other work has argued that militarization and external threats to a country reinforce that society's gender inequalities.Footnote 3

We specifically focus on over-time changes in women's empowerment, which we define as the extent to which women have influence in political and social spaces. Variation in women's empowerment is one component of variation in gender (in)equality and is a manifestation of variation in domestic gender hierarchy—which we define as a power imbalance that, when patriarchal, privileges men generally, as well as masculine and feminine characteristics that support a male-dominant order.Footnote 4 Through analyzing how the preparation for and experiences during war shape women's empowerment, we contribute to the understanding of both cross-national and cross-temporal variation in domestic gender hierarchy in the modern era.

We draw on existing research to examine several potential mechanisms for how conflict and peace might influence women's empowerment, including militarization, demographic changes, changes in social orders, and changes in political orders. Then, we identify observable implications of each and test them on a cross-national data set that spans from 1900 to 2015. We find strong support for arguments positing that, at least in the short and medium term, war shakes up established social and political orders and creates an opportunity for gains in women's empowerment. At the same time, we do not find conclusive evidence that such gains persist beyond ten or fifteen years.

We conclude that domestic gender hierarchies are indeed robust equilibria and resistant to change. Societies often need a major catalyst—like war—to shake up the social and political orders. In the presentation of the findings, we reflect at some length on the examples of El Salvador, Liberia, and China, which illustrate some of the proposed mechanisms and also point to some important limitations to how war relates to changes in women's empowerment.Footnote 5 While each demonstrates how war can open up opportunity for women's empowerment, they also underline war's destructive power for both women and men and the potential for gains in women's empowerment to be short lived. Our study does not imply that war is a net positive for societies nor that shaking up the social and political orders will inevitably result in more egalitarian ones, especially in the long run. One takeaway from our study, which we return to in the conclusion, is that reforming institutions and mainstreaming gender during peace processes has important legacies for gender power relations in postconflict societies, although additional effort may be needed to keep up the momentum for reforms and the establishment of more permanent equilibria.

Conflict and Change in Gender Hierarchies

War's ability to transform social power inequalities has been a topic of rich scholarship.Footnote 6 Charles Tilly has prominently argued that war and the preparation for it have shaped the organization of states and that the organization of states has shaped the conduct of warfare.Footnote 7 Recognizing that war and social orders can be mutually constitutive, we attempt to cut into the interchange and consider war's social legacies for gender power inequalities.

Focusing on women's empowerment as a manifestation of (attenuating) gender hierarchy, we draw on strands of scholarship that produce different expectations. One implication from perspectives linking militarization and threat to gender hierarchy is that we should observe decreasing levels of women's empowerment in societies facing major security concerns. Militarization, or the growth of a country's security sector, and external threats are separate from active conflict: they can happen during war, but they also occur in anticipation and preparation for armed struggle.Footnote 8 From this perspective, we should therefore see the anticipation of war as a hindrance to women's empowerment. Another perspective—not necessarily mutually exclusive from the firstFootnote 9—considers how major shifts in a society's ability to function under the existing order, as might happen amidst destructive war, can create space for women's empowerment and lead to the expectation that war functions as a catalyst for women's empowerment.

War's Anticipation as a Hindrance to Women's Empowerment

One school of thought considers investment in security and gender hierarchy as mutually constitutive and reinforcing: societies that highly value security commit a disproportionate amount of resources toward the education and social development of male leaders and fighters because of the perception that such investment produces greater returns compared to alternative allocations that invest more in girls and women.Footnote 10 Specifically drawing from social role theory, militarization and the expectation of fighting creates and perpetuates gender hierarchy as a means to enhance a society's war-fighting effort.Footnote 11 This process entrenches gendered roles, with men valorized for their potential heroism in war as protectors and women valorized for their potential supporting efforts and their need for protection.Footnote 12 Pateman argues that a gendered social contract emerges in which men are expected to protect and in return receive legitimate authority from the women who benefit from the order provided.Footnote 13 In these ways, the preparation for war fundamentally shapes the distribution of power between those who are normally involved in security production (men in most societies past and present) and those who are not (women). Relatedly, the postwar environment might be associated with backlash against any gains in women's rights and empowerment experienced during war.Footnote 14

The implication from this logic is that periods of heightened readiness for physical protection entrench social support for gender hierarchy. For example, Schroeder argues that interstate conflict and rivalry decrease women's political representation because women are seen as less capable than men of leadership under security threats.Footnote 15 Barnes and O'Brien similarly find that states that are engaged in military disputes and that spend more on their militaries are less likely to appoint women as defense ministers.Footnote 16

The argument that the anticipation of war hinders women's empowerment suggests two potential mechanisms: militarization and a society's threat perception. Building on the existing scholarship we discussed, militarization contributes to gender power imbalances as societal investments in the security sector increase—men are privileged and expected to lead while women are expected to serve in supporting roles. The key implications here are that increases in the size and scope of the military should be correlated with decreases in women's empowerment. An important caveat is that the entrenchment of gender inequality might occur in the absence of ongoing or recent armed conflict, so long as a society is still investing in its military. This line of reasoning leads to two closely linked hypotheses: in the first, militarization has an independent effect from war, and in the second, militarization is an intermediate step on the pathway from war to social changes.

Militarization Hypothesis

Increases in the size of the security sector, regardless of whether there is an active conflict, will lead to decreases in women's empowerment.

Militarization as an Intermediate Step Hypothesis

Periods of war will lead to increases in the size of the security sector, which in turn will lead to decreases in women's empowerment.

Similarly, the threat perception mechanism suggests that when a polity faces a security threat, its citizens prioritize their security.Footnote 17 Prolonged peace, in contrast, can erode the underlying social power imbalances as alternative social orders to militarization become attractive and role expectations change, however slowly. Note that here we mean positive peace—a type of peace that is more than the absence of violence and includes cooperation and trust among societal groups and states—since a perception of threat can exist without active armed conflict. This expectation that positive peace can undermine existing social hierarchies is consistent with scholarship positing that reduced security threats create the potential for a postnational, cosmopolitan orientation of security organizations that, in turn, become more hospitable to gender-based reforms.Footnote 18

During periods of high threat, defense readiness increases in value, with a corresponding emphasis on masculine values and characteristics. Note that this often overlaps with the first mechanism—militarization can be a specific response to perceived threats—but the force acting on women's empowerment is broader in this case. Roles traditionally associated with women and femininity are de-emphasized, which can be compounded by civil liberties reductions in the name of defending the homeland. This effect is most pertinent for external threats because internal threats are more likely to disrupt, rather than entrench, traditional social norms and institutions. Tir and Bailey add that during periods of external threat, although the government and public may expect all citizens to rally around the flag, there might be an increase in skepticism toward the notion that women can enhance security production because of their presumed peaceful nature and expected opposition to war.Footnote 19 Rally around the flag can mean rally around nostalgia for traditional, “men-as-protectors” social orders.Footnote 20 Here the observable implications are fairly precise: we expect the threat perception mechanism to be strongest during interstate wars and, more generally, during periods of threat from external adversaries (contrary to the militarization mechanism, which can operate in the absence of a specific external threat).

Threat Hypothesis

Increases in the external armed threats to a society will lead to decreases in women's empowerment.

War as a Catalyst for Women's Empowerment

Another expectation emerges if we consider war's potential to disrupt social institutions. For many scholars, gender hierarchy is institutionalized—it is embedded in social structures and reinforced by both explicit and implicit norms and practices. If this is the case, then it might require massive disruption to normal social functioning to depart from an equilibrium of unequal power distribution toward greater women's empowerment.

Some scholars have posited that war can disrupt gender hierarchy, at least in the short term.Footnote 21 For example, as men mobilize to fight and die in combat, opportunities emerge for women to enter traditionally male-dominated vocational and social roles. With a greater representation of women in spaces traditionally open only to men, women become valued for a wider array of characteristics and for performing more functions.

Aside from the opening of space for women's representation, war can lead citizens to critique the existing gender hierarchy. Resonating with the earlier arguments related to militarization and threat, if a male-dominant order is justified by a logic of protection, then war's occurrence might cause citizens to first question if the existing order has failed to protect and then consider alternative social orders. For example, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, when reflecting on why she felt Liberia needed a woman president after a long and traumatic war, observed that “the country had been led by men for 150 years—and look where that had gotten us.”Footnote 22

The argument that war can disrupt existing social orders and open up space for women's empowerment requires a few important qualifications. First, one scope condition for this argument is that there has to be some opportunity for the order that replaces the old one to be more egalitarian. The argument might not apply to pre-modern periods when emerging global norms were not contributing to widespread trends pointing to greater women's empowerment.Footnote 23

Second, better representation does not easily translate into empowerment,Footnote 24 so the argument is more one of necessity than sufficiency. That is, without improvements in women's representation in key political, economic, and social spaces, improvements in women's empowerment would be infeasible. Moreover, we recognize the important downstream effects from changes in women's representation that can contribute to women's empowerment.Footnote 25 Once women have served in key roles during times of national crisis, they gain legitimacy as relevant actors in social and political spaces and members of society become more aware of women's capability to fulfill the gamut of social and political roles, including those with formal authority.Footnote 26

Third, women's empowerment gains during periods of massive social disruption are neither costless nor necessarily permanent: women's empowerment can come at the expense of massive loss of male life in combat, and/or at the expense of other underprivileged groups who are forced to serve in the military. War also negatively affects women's life and health in profound ways.Footnote 27 Furthermore, gains during conflict could be followed by retrenchment afterwards,Footnote 28 particularly in the daily lives of ordinary women.Footnote 29 The process of women's empowerment is not likely clean or linear and may exacerbate other social hierarchies, such as those based on race or class.

Taken together, the arguments—and caveats—related to war as a catalyst for women's empowerment include several potential mechanisms with specific implications. First, wars can transform a country's demographics: large percentages of men often die in combat. Even in cases where women represent a noticeable percentage of fighters, men die at higher rates than women and are more likely to become prisoners during or after war.Footnote 30 Women could need to fill the gaps in social and political roles that men originally provided. This mechanism should hold for particularly catastrophic interstate wars, where the male death toll is so overwhelming that it leads to a dearth of men to fill the roles typically reserved for them.Footnote 31 In this case, the clear prediction would be that wars with large male population losses should be correlated with women's empowerment increases.

Demographic Shifts Hypothesis

Periods of severe interstate war will lead to decreases in male population sizes, which, in turn, will lead to increases in women's empowerment after the conflict.

A related mechanism is the “Rosie the Riveter” effect. Even when war does not produce a significant demographic change, when men leave to fight during conflict, space could open up in the labor force for increased women's participation. Economic openings during wartime might then improve women's empowerment if economic activity spills over into political and social activity. This effect should be most pronounced if the war coincides with a period of job creation (e.g., through increased defense spending), such that women are needed to meet the new labor demands. When wars occur during periods of a stagnant or contracting economy, there will be fewer opportunities for women's empowerment via this mechanism. In contrast with other mechanisms, this mechanism points to a conditional expectation that war would lead to empowerment via an impact on the labor market only when economic growth accompanies war. This mechanism is also distinct from the demographic shifts mechanism because it should be shorter term; women might be displaced by the men returning from military service. This is therefore a mechanism that operates most strongly during conflict, rather than before or after, and especially during severe interstate war that would displace significant proportions of men.Footnote 32

Labor Shifts Hypothesis

When accompanied by increases in economic production, periods of severe interstate war will lead to short-term increases in women's empowerment.

The next mechanism for the argument that war is a catalyst for women's empowerment pertains to the shaking up of entrenched social orders. If gender hierarchy (patriarchy) is an equilibrium social order, a major event like war might be necessary to force societies to select a new equilibrium. War might fundamentally transform the roles that women expect and are expected to fill in a number of ways. If women become fighters too, they could become valorized for providing protection and undermine the gender social contract. Additionally, during the conflict, women might participate more in civil society and social movements, especially in anti-war movements, gaining critical leadership experience.Footnote 33 For example, women founded and led key civil-rights groups amid intrastate conflicts in Peru and Argentina (during the Dirty War), and they also served as the principal interlocutors with the state during civil wars in El Salvador, Sri Lanka, and Peru.Footnote 34 As women take on new roles, traditional expectations for women to primarily birth and raise children might also erode, leading to fertility rate decreases.

The key here is that conflict opens up the opportunity for women to fundamentally change their normal social roles and positions, making the hierarchical equilibrium untenable. This mechanism differs from the demographic and labor shifts hypotheses because it is not necessarily related to the absence (temporary or permanent) of men. Additionally, the change in women's roles should continue to operate long after war is over; a new social equilibrium implies durability. This mechanism should be particularly strong for intrastate conflicts when status quo power arrangements are critically challenged by armed groups and their sympathizers within society. Many rebel groups have intentionally tried to recruit women and provide them a chance to become fighters.Footnote 35 For example, Wood finds that women made up approximately 30 percent of rebels in civil wars in Peru, El Salvador, and Sri Lanka, and 25 percent in Sierra Leone.Footnote 36

Roles Shift Hypothesis

Periods of war will lead to increases in women's empowerment, decreases in the fertility rate, and increases in opportunities for women to take on new social r oles.

War might shake up not only the social order but also the political order. If a new regime emerges after conflict is over, there could be several ways for women to become more empowered. For example, with a regime change comes a demand for new political actors, and women are often seen as more legitimate after conflict because they are perceived (correctly or not) as less responsible for it.Footnote 37 When a conflict leads to a regime change, it can also cause fundamental shifts in the government structure, most commonly through a new constitution. These new constitutions, often associated with democratic institutions, can require electoral quotas for women, improved legal status for women, and/or the implementation of proportional representation systems, which present lower barriers to entry for women. Therefore, if this mechanism is in play, we would expect to see war positively correlated with improvements in female political power, particularly after wars ending in regime change.

Political Shifts Hypothesis

Periods of war will increase the propensity for regime change, which, in turn, will lead to increases in women's empowerment.

Table 1 presents an overview of our hypotheses that arise from the different frameworks. Note that the demographic shifts hypothesis, political shifts hypothesis, and one version of the militarization hypothesis imply that the respective mechanisms are intermediate processes. The labor shifts hypothesis implies a conditional (interactive) relationship. The roles shift hypothesis implies more specific outcome variables.

TABLE 1. Summary of hypotheses and expectations

Research Design

Data and Dependent Variables

The data we use cover all states in the international system from 1900 to 2015. Our unit of analysis is the country-year. We examine changes in women's empowerment for up to fifteen years, at which point the model coefficients are estimated with high uncertainty, partly because of the reduced sample size. Our data structure does not allow for the examination of longer-term, generational change in social institutions.

The outcome of interest is the change in women's empowerment in a given country. We rely on the women's political empowerment index (v2x_gender) from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project.Footnote 38 The variable is a broad measure of women's influence in society: it incorporates not only political power but also civil liberties and social roles, matching well to the concept of women's empowerment in our arguments. The V-Dem Project defines women's political empowerment as “a process of increasing capacity for women, leading to greater choice, agency, and participation in societal decision-making.”Footnote 39 It is the most comprehensive measure of female empowerment in the V-Dem data set and provides advantages over many traditional measures of women's equality because it captures multiple facets of women's rights and participation.Footnote 40 An aggregated index ranging from 0 to 1, it takes the average of three, equally weighted, intermediate indices: the women's civil liberties index (v2x_gencl), the women's civil society participation index (v2x_gencs), and the women's political participation index (v2x_genpp). According to Sundström and colleagues, “the index is based on assessments from thousands of country experts who provided ordinal ratings for dozens of indicators.”Footnote 41 Those expert ratings are then compiled into an index using a Bayesian item response theory model.

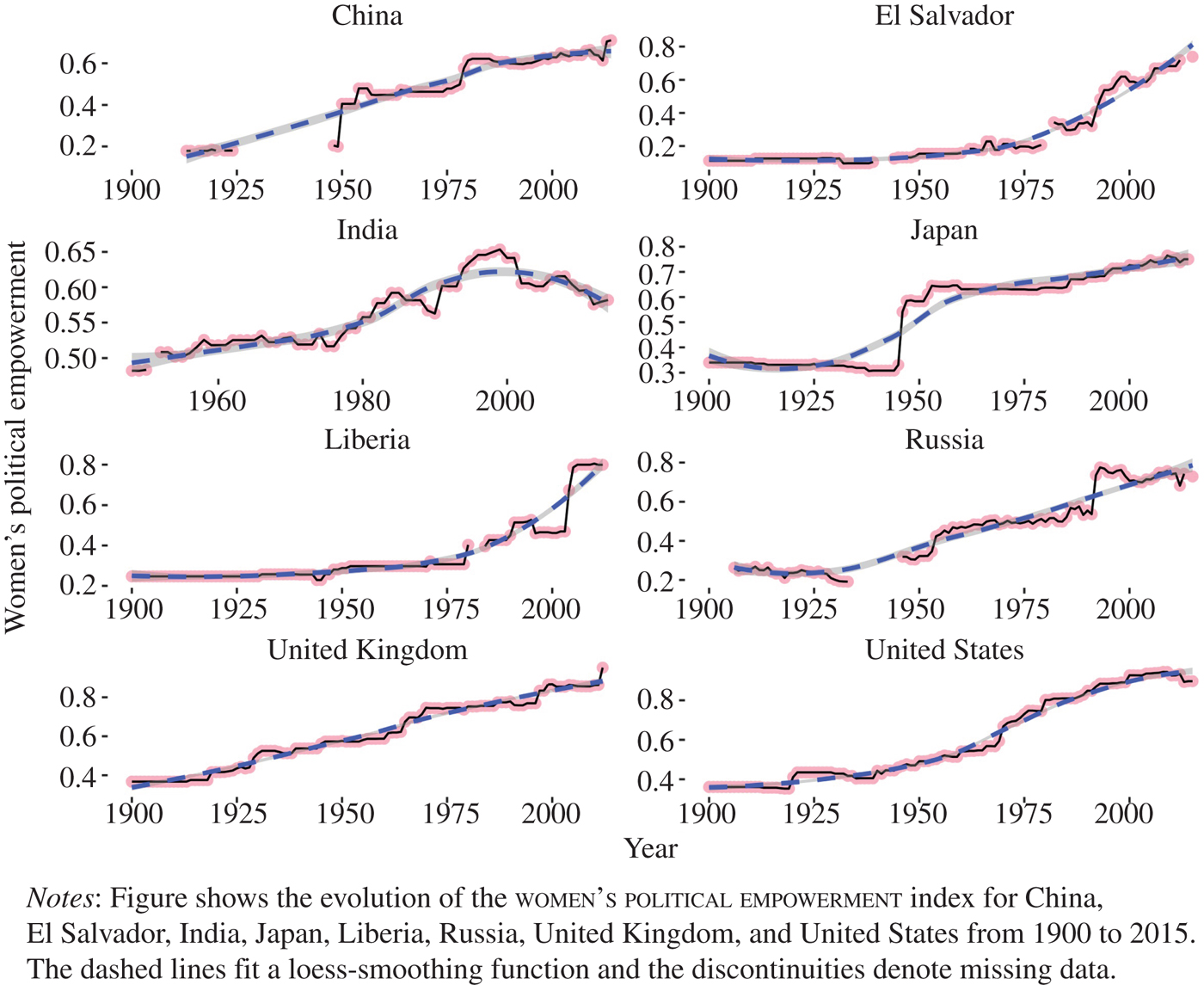

For an overview of the women's empowerment variable, graphs in panels (a) and (b) of Figure 1 illustrate the geographic distributions of women's political empowerment at two points in time (1950 and 2005), while panel (c) shows the global average trend of women's empowerment from 1900 to 2015. On average, the world has evolved toward more women's political empowerment, and the rate of change has been faster since the end of World War II. Figure 2 shows the evolution of gender equality in terms of women's political empowerment for eight countries over time.Footnote 42 We note that change can be either drastic or gradual, suggesting that the coding picks up both major legal and constitutional reforms as well as more gradual changes in social norms.

Figure 1. The evolution of women's empowerment, 1900–2015

Figure 2. Women's empowerment for select countries, 1900–2015

Our hypotheses focus on changes in women's empowerment, so we use the differences in women's political empowerment from the previous year to current or future years as the dependent variables. Measuring women's empowerment in differences produces stationary dependent variablesFootnote 43 and also reduces the potential for inferences to be confounded by country-specific and time-invariant characteristics that predispose some countries to be more egalitarian than others.Footnote 44

For the roles shift hypothesis, we also examine other dependent variables that allow us to see specific changes in women's social roles. First, we use changes in the women's civil society participation index to measure changes in how active women are in civil society. Second, we use measures of changes in fertility rates, from the World Bank's Development Indicators.Footnote 45 If war leads to women's empowerment by transforming their expected social roles, we expect declining fertility rates, since high fertility rates reflect expectations for women to fulfill traditional social roles associated with child bearing and care giving.

Independent Variables

We use a number of variables to measure war. We use the Correlates of War (COW) dataFootnote 46 to create three binary variables: interstate war, intrastate war, and war (if either interstate, intrastate, or both occur in a given year). Panel (c) of Figure 1 plots trends in these types of conflict from 1900 to 2015. We also create a binary variable of existential war, since not all interstate wars threaten a country's survival. Existential war is coded as true when the country was fighting an interstate war with a contiguous state, and/or a war against a major power.Footnote 47 Wars against noncontiguous and non-great-power states, such as the American wars in Vietnam or Iraq, should be less threatening to the homeland.

In some models, we use nonbinary indicators of war exposure to specifically examine how war duration and severity shape women's empowerment. Duration counts a country's years of continuous war. Battle deaths (logged) is the natural log of the number of battle-related fatalities in war, as measured by Lacina and Gleditsch.Footnote 48

To test the militarization hypothesis, some models include military personnel per capita from the National Material Capabilities Data (NMC, v5) in the COW Project.Footnote 49 We focus on this variable rather than military spending per capita because we expect that the number of people in a military has a more direct effect on a country's social dynamics than a purely monetary variable.Footnote 50 We convert this to logged military personnel per capita.Footnote 51 Because of our interest in the changing pace of militarization, we use the first difference and also control for overall militarization levels by including the temporal lag of the military personnel variable.

We have four additional explanatory variables used to investigate our hypotheses. First, for the threat hypothesis, we use a measure of territorial threat from Gibler and Tir.Footnote 52 This is a “predictive measure of probable, latent threat to the territorial core of the state”; it ranges from 0 to 1, with greater values indicating greater threat to homeland territory.Footnote 53 We are most interested in the year-on-year change in territorial threat as an explanatory variable but also include the one-year lag of territorial threat to control for a society's baseline threat level.

Second, to test the demographic shifts hypothesis, we use the natural log of population size from the NMC data to examine how population size changes during and after war influence women's empowerment. Again, we focus on the first difference of population size and include the overall lagged population size as a control. We use additional measures that break down population changes by sex as robustness checks.

Third, to address the political shifts hypothesis, we use the Archigos political leader data to create a binary variable, irregular leadership change, that is true when there was an irregular leader entrance or exit.Footnote 54 We use a measure of irregular leadership change because these are the type of regime transitions that provide openings for new equilibria and therefore can affect the rapid adoption of new social policies. These are more likely to occur in a war's aftermath and are therefore more closely linked to our arguments. We include in the robustness checks section in the appendix models with alternative measures of regime change.

Fourth, the labor shifts hypothesis—about wars during economic output booms—implies a conditional relationship where a war's effect on women's empowerment gains should be stronger during times when war coincides with economic growth. We thus interact the one-year change in logged energy consumption from the NMC data with the occurrence of war. We expect that the marginal effect of war is more positive when there are substantial energy consumption increases.

Note that we do not have any mechanism-specific independent variables for the roles shift hypothesis. While the Thomas and Wood data have information on female rebel fighters,Footnote 55 its temporal coverage (1979–2009) is too constrained for inclusion in our models. As mentioned earlier, we use changes in fertility rates and women's civil society participation index as the dependent variables in two tests of the roles shift hypothesis.

For additional control variables, we consider the potential for democratic countries to have greater levels of gender equality and lower militarization, so we control for regime type using the Polity IV index.Footnote 56 We include both the lag value and the first difference. We also control for the level of economic development because the propensity for war and gender norms vary with economic growth. We thus use the logged NMC energy consumption variable and include both the temporal lag and the change as control variables. In addition, we also control for the calendar year because we anticipate an increasing trend of women's empowerment.

Model Specification

We rely on two approaches to model the relationship between war and women's empowerment: fixed effects regression and an instrumental-variable approach with an endogenous binary-treatment variable.Footnote 57 First, we use fixed-effects regression models that hold constant all the unobserved time-invariant influences on changes in women's empowerment. To address the reverse-causality expectation from the existing literature that gender inequality increases the potential for war, which would bias the estimates toward finding that war has a negative relationship with the outcome of women's empowerment, we control for the temporally lagged level of women's empowerment in these models. To address the potential for spatial autocorrelation arising from neighborhood-wide factors that shape women's empowerment across multiple states at the same time, we control for the spatial lag—the average change in women's empowerment in neighboring states.Footnote 58

Second, we use an instrumental variable approach—specifically, endogenous treatment regression—to further account for war's potential to be endogenous to society's levels of gender inequality.Footnote 59 We use as instruments for war counts of the number of civil and interstate wars occurring in a country's contiguous neighborhood at one- and two-year lags because existing work has shown that armed conflict tends to diffuse.Footnote 60 Neighboring war and instability can create a number of negative externalities, including refugee flows, regional economic depression, and demonstration effects. Moreover, neighboring war often involves transnational armed actors that can similarly destabilize neighboring countries and aggrieve neighbors. Countries that border states at war are at greater risk for war for reasons that are often largely outside of their own control.Footnote 61 Diagnostic least-squares models show that war activity in neighboring states during the previous two years well explains war onset.Footnote 62

For both types of model, we generate standard errors that are robust to clustering on the country of observation to account for additional within-panel autocorrelation. Since the fixed effects models rely on fewer modeling assumptions and since the instruments are not consistently strong for all of the types of war treatment variables, we emphasize the fixed-effects models and use the endogenous treatment-regression approach to demonstrate the robustness of the findings.

Results

Core Models: Broad Effects of War

We first examine the effect of war (interstate or intrastate) on the change in women's empowerment in the current year and in future years at one-year, two-year, three-year, four-year, five-year, ten-year, and fifteen-year increments.Footnote 63 Coefficient tables of all results are in the appendix. We plot the marginal effects distributions via a simulation approach. Specifically, we follow Hanmer and Ozan Kalkan and run 1,000 simulations based on the posterior distribution of the model parameters (i.e., the coefficients and variance-covariance matrix).Footnote 64 For each simulation, instead of presenting the marginal effects of an “average case,” we hold the other covariates at each case's observed values, generate marginal effects for each case, and then average over all observations. The goal of this “observed value” simulation approach is to obtain an estimate of the average effect in the population.

Panel (a) of Figure 3 shows that, with the fixed-effects regression approach, war is positively associated with change in women's political empowerment in the medium term. That is, the war variable is statistically significant (95 percent confidence interval in a two-tailed test) and positive in the models of forward changes in women's empowerment at three to five years ahead. The uncertainty increases for the predicted marginal forward effects farther out as the sample size decreases.

Figure 3. Marginal forward effects of war on women's political empowerment

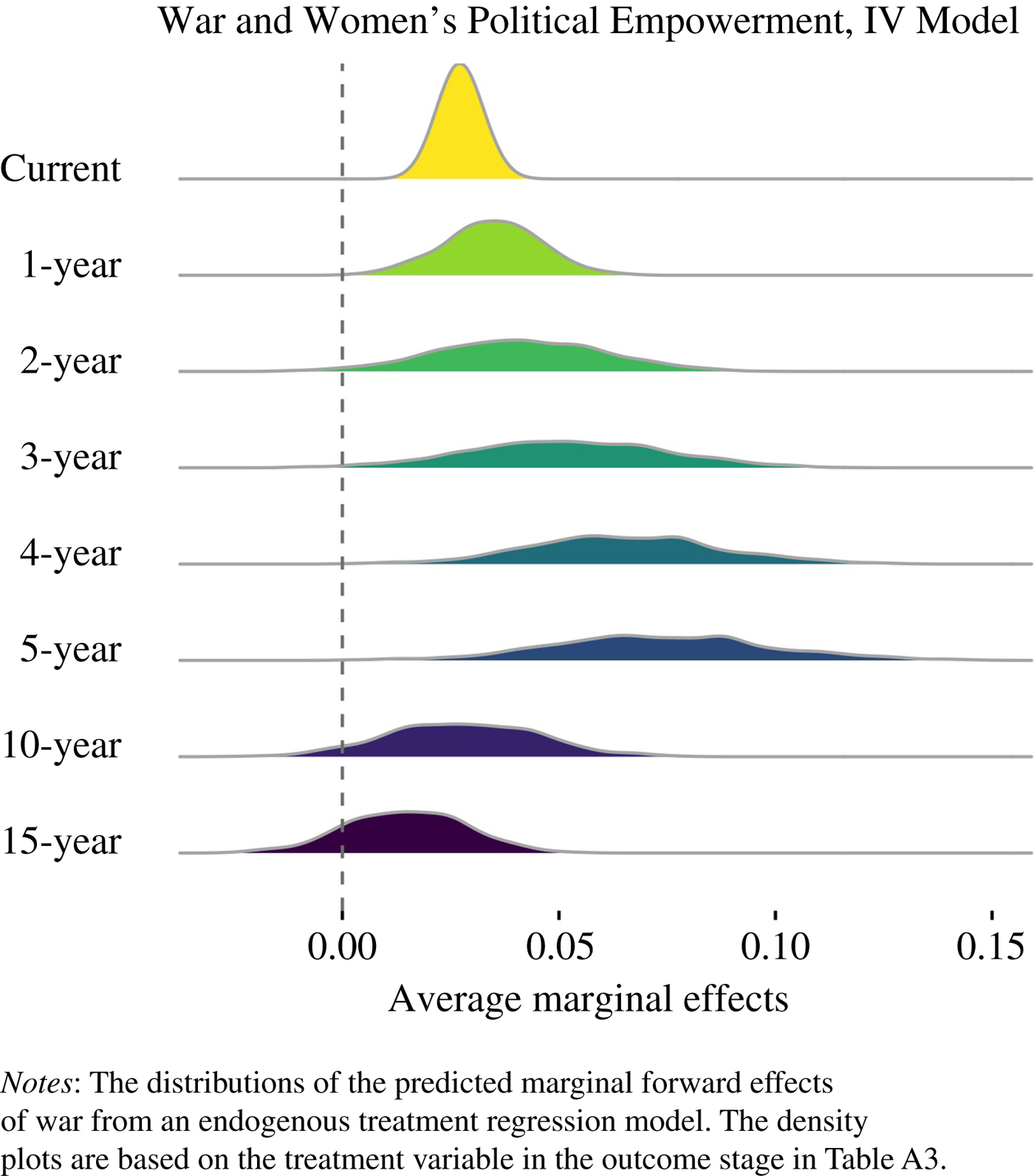

Figure 4 presents the marginal forward effects of war from the endogenous treatment regression models, which leverage the exogenous variation in war caused by neighborhood diffusion to isolate the war-to-empowerment causal direction. The results confirm that war has a positive medium-term effect on changes in women's empowerment. Moreover, we see that this model produces results in which war has a positive short-term effect as well, and the magnitudes of the coefficients are higher. One explanation is that the IV approach more completely reduces the potential for a countervailing endogeneity bias, given the expectation that gender inequality (low women's empowerment) contributes to the onset of war in the first place, making it difficult to see a positive effect of war on changes in women's empowerment. In this way, the fixed effects model appears to be the more conservative test, and we rely on it for the remaining results because it makes fewer assumptions, it allows us to consider the effect of multiple treatments (e.g., new war and ongoing war) in the same model, and it allows us to consider the effect of additional treatments (e.g., war duration and severity, as well as different war types) that are not as well explained by neighboring war.

Figure 4. Marginal forward effects of war on women's political empowerment, IV model

The temporal dynamics in our results are both interesting and puzzling: what might explain war's medium-term but not long- or short-term (in the fixed effects models) effects? To investigate this further, we first unpack the different relationships that periods of new war, ongoing war, and recent war have with women's empowerment. Each of those periods could relate to the effect that war has on women's empowerment since they are being compared to periods in which there has not been war for at least two years. In panel (b) of Figure 3, we see that the relationship between new war—when the current year has war but the previous year did not—and women's empowerment has a negative sign, though not statistically significant. This is different from ongoing war (panel c)—when both the current and previous periods experienced war—and recent war (panel d)—when the previous period experienced war but the current period does not. Ongoing war is associated with medium-term women's empowerment increases, while recent war is associated with short-term women's empowerment increases. States that have been experiencing war for more than a year can expect to experience increases in women's empowerment within a few years, and states that have recently come out of war can expect to experience immediate increases in women's empowerment.

The difference in the impact of new war and ongoing war provides insight into the temporal dynamics. First, the lack of a robust short-term effect appears in part to be a result of the fact that the overall war variable—a combination of new war and ongoing war—averages out opposite effects. Second, the estimated effects of new war and ongoing war also help rule out an alternative explanation for the observed relationship between war and women's empowerment in the medium term: if women's empowerment suffers during war, women's empowerment may just go up and return to “normal” in a few years when seen from the perspective of a period of war. This does not appear to be the case—new war is not associated with a statistically significant short-term drop in women's empowerment, or even a drop that is as great in magnitude that we see for the positive effects of ongoing war and recent war. Instead, these findings indicate that war leads to increases in women's empowerment beyond any short-term drops that tend to accompany the onset of war.

What explains the lack of statistically significant longer-term (ten to fifteen years) effects in the models presented so far? The growing uncertainty as the sample size gets smaller and smaller (when needed to make more forward expectations) likely explains some of the declining statistical significance. We should also expect greater heterogeneity in outcomes as more time separates the impulse (war) from the response (change in women's empowerment). In particular, longer time windows will skip over some periods of war that occur in the interim and that are not reflected in the coding of the war variable. Models presented in the appendix do not show much evidence that the attenuating effect is caused by the periods of war being followed by future year-on-year reductions in women's empowerment resulting from backlash.Footnote 65 Regardless, the results point to an important caveat: we cannot conclude that societies do well to consolidate the observed medium-term increases in women's empowerment.

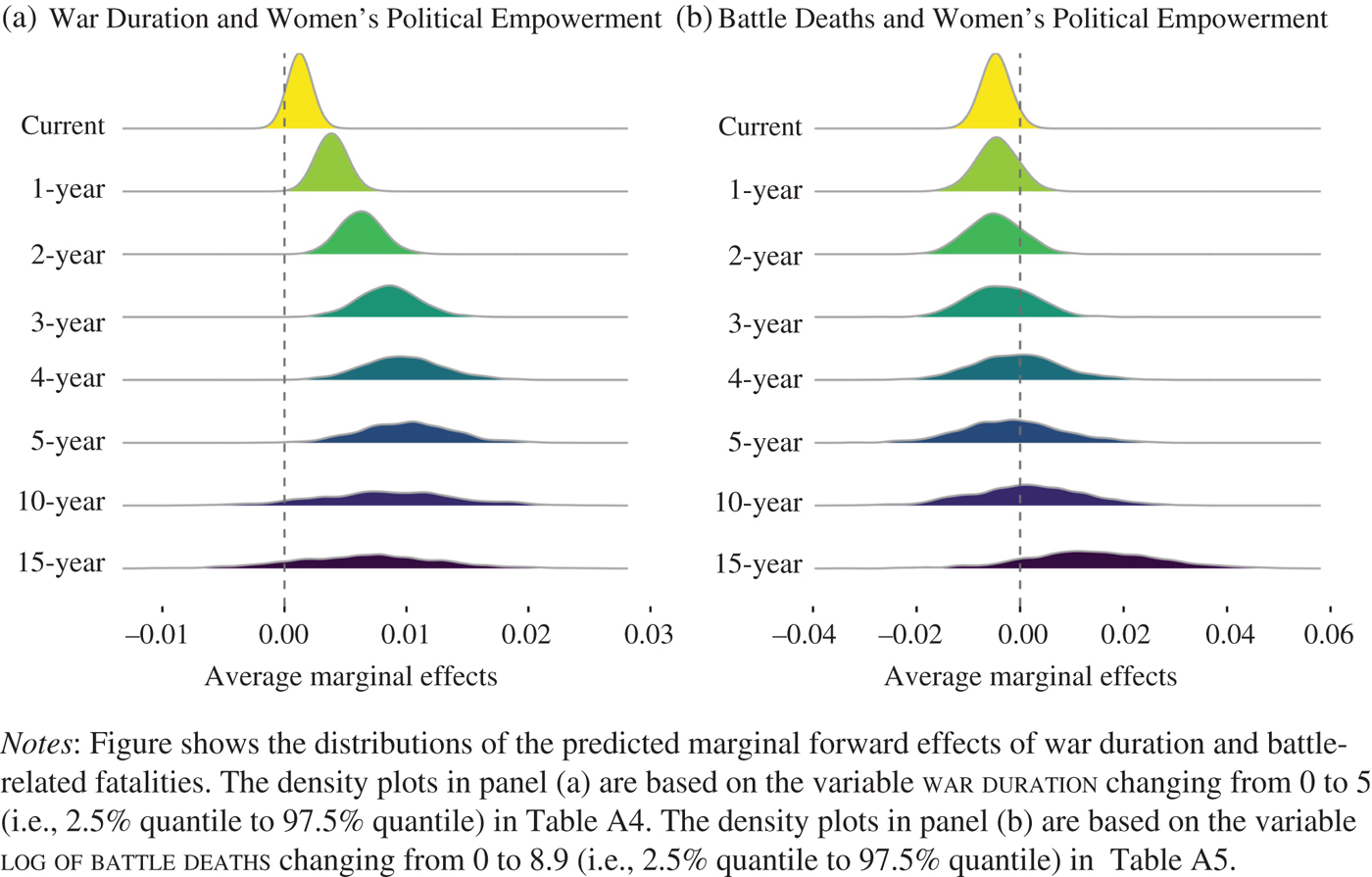

Thus far, we have explored periods of war as binary. Figure 5 presents models that consider the duration of war and the severity of violence as interval-level explanatory variables. The findings indicate that war duration is associated with short- and medium-term increases in women's empowerment. The longer a war, the more we can expect subsequent increases in women's empowerment. Battle-related fatalities, however, are not associated with significant increases in women's empowerment.Footnote 66 In fact, in the very short term, high battle deaths are associated with immediate decreases in women's empowerment.Footnote 67 That battle-related fatalities do not exhibit the same relationship points to the possibility that the positive impact of war on women's empowerment is not operating through processes related to war wiping out segments of the population. Rather, it is protracted struggle that shakes up society and opens up space for women's empowerment.

Figure 5. Marginal forward effects of war duration and battle deaths on women's political empowerment

In focusing on different types of war, we see in models presented in the appendix that there is not much difference in how interstate war, intrastate war, or existential war shape women's political empowerment.Footnote 68 Recent periods of wars of each type tend to be associated with short-term increases in women's empowerment, and ongoing periods of war of each type tend to be associated with medium-term increases.

Mechanisms: Roles Shift

The analyses indicate that wars, especially longer wars, are associated with medium-term women's empowerment increases. We have presented multiple mechanisms that might connect war to changes in women's empowerment. Thus far, we do not see much support for the militarization or external armed threats mechanisms because we are finding that war tends to increase, rather than decrease women's empowerment. We also have not seen much support for the demographic shifts hypotheses because war severity is not associated with women's empowerment. We now turn to additional models that help to further tease out the mechanisms in play. Table 2 provides a snapshot of the results.

TABLE 2. Summary of findings

To examine the roles shift hypothesis, we first find that recent war and ongoing war positively affect changes in women's participation in civil society.Footnote 69 Then, we turn to models where the dependent variable is immediate and future changes in fertility rates.Footnote 70 Figure 6 plots the average marginal effects. In general, we find that existential war lowers fertility rates in the medium term, while general wars are not as strongly associated with fertility-rate reductions.Footnote 71 In additional models in the appendix, we see that interstate wars tend to have a stronger relationship with changes in the fertility rate than intrastate wars.Footnote 72 It appears to take an interstate threat to society—rather than necessarily the domestic upheaval that comes with civil war—to affect fertility rates. The national call to arms that accompanies interstate war does apparently open up spaces for women to begin filling less traditional roles. In other models presented in the appendix that use battle deaths as the key explanatory variable, we again do not observe a statistically significant relationship.Footnote 73 So, similar to the models of women's empowerment, it is not war severity per se that is shaping fertility rates. Taken together, these findings offer some support for the roles shift hypothesis, though with two caveats. First, we do not have enough evidence to conclude that war leads to lasting (beyond ten years ahead) changes in social roles, so it might not be the case that war allows for the establishment of new equilibria of gender norms and institutions. Second, we do not find that intrastate conflict is especially important in the shifting of social roles, which means that the roles shift might not be specifically tied to domestic challenges to status quo power arrangements or opportunities for women to participate in insurgencies.

Figure 6. Marginal forward effects of war on changing fertility rates

The case of El Salvador demonstrates the potential for the roles-shift mechanism to connect war to women's empowerment, at least in the short and medium terms. As Wood notes, “civilian gender roles may also change dramatically during war. In El Salvador … women became the primary interlocutors with the state as they sought news of their detained or disappeared menfolk.”Footnote 74 Before the civil war from 1980 to 1992, women had very limited economic, social, or political power. The Catholic Church—extremely popular and powerful throughout the country—espoused a conservative gender ideology where a woman belonged in the house, and she lost status for working outside the home.Footnote 75 Although women had inheritance rights, few owned property; most did not work.Footnote 76 The war was transformative. Viterna notes that “regardless of the nature of their participation (or nonparticipation), the violence and upheaval of war forced a redefinition of gender roles.”Footnote 77 As men left to escape government repression or fight in the rebellion, women became household heads, so that, according to Mason, war—and the accompanying social, demographic, and economic changes—undermined the social structures of rural society.Footnote 78 Faced with severe economic problems and concerned with government abuses, many women started to organize, forming national nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to address economic concerns, human rights abuses, and women's rights issues.Footnote 79 Many became involved in the war effort, both in support positions and also as fighters. A woman was second in command of the main rebel group (FMLN), and 30 percent of the combatants were women.Footnote 80 They gained critical organizational experience, and as Shayne argues, their participation “helped to pave the way for a reconceptualization of the role and status of women in Salvadoran society.”Footnote 81 By the end of the conflict, over half of heads of all households were women, and women led a national campaign that successfully passed several pieces of legislation improving women's rights.Footnote 82

The war in Liberia, which experienced civil war from 1989 to 2003, also reveals the potential for war to lead to major (but not complete) women's empowerment as a result of women's participation in both the fighting and the peace movements. According to Tripp, Liberia “illustrates how the decline of conflict led to the introduction of women's rights provisions in the peace agreement, women's heightened engagement in electoral politics, and their increased involvement in legislative reform affecting women.”Footnote 83 During the war, some estimate that tens of thousands of women participated as armed combatants.Footnote 84 Because so many men were killed or in hiding, more women became primary breadwinners and in general were more active in their communities.Footnote 85 Women-led social movements, especially the Liberian Women's Mass Action for Peace (LWMAP) which emerged from the Women in Peacebuilding Network (WIPNET), formed during the war and played an important role in using protests, including a sex strike, to move Taylor's government and the LURD rebels toward negotiations and to keep them negotiating.Footnote 86 The Mano River Women Peace Network (MARWOPNET) sent delegates to the peace process that ended the war.Footnote 87 The LWMAP movement also led efforts to reconcile and reintegrate child soldiers and sexual violence victims after the war.Footnote 88 The women's movements also mobilized voters for Ellen Johnson Sirleaf's successful 2005 campaign to become the first female president in all of Africa.Footnote 89 The war upended Liberian society so much that it opened up space for a woman president and created the impetus for major security-sector reform, including increasing women's representation in the Liberian National Police and creating new institutional initiatives, such as forming the Women and Children Production Unit.Footnote 90

The cases of El Salvador and Liberia also demonstrate the struggles for war to lead to lasting changes in the shifting of women's roles and thus empowerment. In the case of El Salvador, the partial gains in women's empowerment experienced in the aftermath of war were difficult to fully consolidate. Viterna notes that while women occupied many postwar community leadership positions, postwar opportunities were not equally available (not even to all former combatants), and over a quarter of former guerrillas expressed frustration over “lost promises.”Footnote 91 In the case of Liberia, role shifts during war and legislative and electoral wins shortly after peace were followed by challenges in consolidating long-term gains. Despite Ellen Johnson Sirleaf's rise to the presidency, men still dominated the highest levels of government, including her cabinet.Footnote 92 Socially, men have remained less supportive of the changing roles, and norms like female genital mutilation still persist.Footnote 93

Intermediate Mechanisms

Turning to other findings related to the mechanisms, a number of the hypotheses imply intermediate mechanisms, so additional analyses examine whether military personnel per capita, population change, and irregular leadership change are intermediate variables on the pathway from war to women's empowerment. We first run a set of models to test whether war can explain changes in these variables. We then include these variables as covariates in the core regression models run earlier to see if they are associated with women's empowerment independent from the effect of war. The marginal effects of war with and without these intermediate variables can also be compared to see how much of the relationship between war and women's empowerment is accounted for by these intermediate processes. Figure 7 summarizes the results.Footnote 94

Figure 7. The effect of war via intermediate variables

We find that military personnel per capita increases during periods of war as expected, but this change is not strongly associated with changes in women's political empowerment (panels a and b of Figure 7), and the medium-term direction is actually positive instead of the negative direction expected by the militarization hypothesis. To further examine the militarization hypothesis, we use per capita military expenditures as an alternative measure to military size by personnel. We see that for two and three years ahead, increases in military expenditures are associated with a decline in women's empowerment at the 90 percent confidence level, consistent with the militarization hypothesis. There is some indication that war leads to more militarization, which then produces a countervailing force that partially limits the extent to which war opens up space for women's empowerment.Footnote 95 The long-term effects at ten and fifteen years ahead, however, point to a positive relationship between changes in military expenditures and women's empowerment, which is not expected. We consider the findings here inconclusive, and the difference in the short-term and long-term effects of military expenditure could merit further study.

The Liberian case demonstrates the potential for this countervailing effect of militarization. The militarization of Liberian society during protracted war had profound implications for women's (dis-)empowerment and security. The war itself diverted resources to the security sector and away from female education.Footnote 96 The presence of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL), which entailed the deployment of thousands of international troops during the peace-building period, resulted in widespread sexual exploitation and abuse perpetrated by the peacekeepers.Footnote 97 This example points to the potential for international peacekeeping efforts to contribute to the overall militarization of society with potentially stark gender implications.

Turning to population shifts as an intermediate variable (panels a and c of Figure 7), we see that population change is negatively associated with women's empowerment in the longer term, but war does not have a statistically significant relationship with decreases in a state's population (for both men and women).Footnote 98 These findings should be considered along with the results presented earlier, in which we do not see a relationship between battle-related deaths and women's empowerment, which we would expect to see if population decline from severe war is a key intermediate variable from war to women's empowerment. The combination of evidence does not sufficiently support the demographic shifts hypothesis.

Irregular leadership change is the most viable candidate of the intermediate mechanisms explored in these analyses. We find that war increases the likelihood of irregular leadership change, and irregular leadership change is associated with positive changes in women's political empowerment (panels (a) and (d) of Figure 7). Combined with the decreased marginal effects of war when the intermediate variables are included, as seen in panel (e) of Figure 7, this supports the political shifts hypothesis. The political adjustments that are more common in the wake of war appear to be an important mechanism by which war can lead to women's empowerment.

The case of the Chinese Civil War exemplifies how war can contribute to women's empowerment via political shifts. This can be seen specifically when considering the adoption of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s 1950 Marriage Law.Footnote 99 Women and men in the Confucian society belonged to a “rigid hierarchy of submission and dominance, passivity and activity, weakness and strength.”Footnote 100 Before the CCP came to power in 1949, all cycles of Chinese dynastic decline resulted in calls for restoring the male-dominant Confucian gender hierarchy. During interstate war with the Japanese and the civil war with the Nationalist Party from the 1930s to 1940s, the position that changing women's relationship to production would naturally change their familial, societal, and political status had become dominant in the CCP.Footnote 101 Immediately after the 1949 establishment of the PRC, campaigns were launched for the 1950 Marriage Law; 1950–1953 was the “high tide” of promoting women's rights and political and economic participation. Women's rights activists, such as Soong Ching-ling, Deng Yingchao, and He Xiangning, assumed prominent positions in the new communist government. These campaigns and appointments swiftly raised women's overall status and political gender equity in postwar China.Footnote 102 At the same time, the case of China demonstrates how initial momentum toward women's empowerment can quickly taper during the Great Leap Forward campaign (1958–1962) and the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), as illustrated in Figure 2 and the persistent male dominance seen in high male-to-female population ratios.Footnote 103

In terms of other mechanisms, we do not find support for the threat hypothesis. In fact, contrary to expectations, in results shown in the appendix, territorial threats (measured in both changes and lagged levels) has a positive relationship with changes in women's empowerment at leads of five and ten years when included as an independent variable in models with and without war.Footnote 104 Territorial threats tend to accompany periods of war and produce a positive increase in women's empowerment. Here, our findings are not necessarily at odds with existing studies that have shown that international threats decrease the descriptive representation of women in positions of political authority—selection of female leaders is not the same as women's empowerment in general.Footnote 105

We also do not find much support for the labor shifts hypothesis.Footnote 106 In models presented in the appendix that regress changes in women's empowerment on the interaction of the change in energy consumption variable and the war variable,Footnote 107 we do not see evidence of a conditional relationship in which war is especially likely to lead to increases in women's empowerment during times of economic growth. This is contrary to popular tropes, but it is possible that we fail to find results because our data are limited.Footnote 108

We run several sets of robustness checks to demonstrate that our findings are generally consistent across alternative measures of some key variables and alternative sets of controls. Our main findings hold in each set of robustness checks. A full discussion of these checks is available in the appendix Tables C1–C14.

Intersection with Alternative Approaches

Using a positivist lens, our analysis has examined the link between armed conflict and gender power imbalances within society. From theoretical priors, we posited testable hypotheses and considered them using quantitative data. Our approach is not the only approach that can shed light on the research question. Sjoberg, Kadera, and Thies point to the value for dialogue across different epistemological and ontological approaches.Footnote 109 Indeed, our analysis resonates well with existing scholarship using alternative approaches. This is not to say that the alternative approaches are in perfect agreement or redundant. Rather, alternative approaches provide insight—such as the complex ways gender power manifests and the different ways that violence is experienced throughout society—that would be less well suited for our approach. At the same time, our analysis provides empirical support for some of the ways that violence shapes gender power dynamics and thereby speaks to other literatures on the consequences of war that have yet to consider the gendered consequences of violence.

The key findings—that war can serve as a catalyst for women's empowerment primarily via the mechanisms of role shifts and political shifts—are consistent with scholarship rooted in feminist theory and methods that has considered how war can provide an opportunity for women's empowerment, at least temporarily. Cockburn argues that anti-war movements successfully advance a feminist agenda because the gendered nature of war becomes so apparent.Footnote 110 War creates an opportunity for feminist movements to gain traction and for societies to be so shaken up that norms and institutions associated with hegemonic masculinities can become more egalitarian. Relatedly, Tripp suggests that war can disrupt societal gender norms and, when accompanied by political openings and women's movements, can lead to “gender regime change” that includes advances in women's rights and the rise of women to positions of power.Footnote 111

Mageza-Barthel identifies how the Rwandan genocide against the Tutsi shook up the society so much that women have become politically and socially empowered in the postgenocide era.Footnote 112 More broadly, Wood uncovers how war, especially civil war, can transform the accepted roles that women can fill.Footnote 113 During war, women are often needed as security producers and actively participate in the fighting. If women can be accepted as, or even valued for, being security producers, then it becomes more accepted and indeed normal for women to have authority in society. We should not assume, however, that the new roles are all virtuous. Sjoberg shows that women often perpetrate heinous violence during war, just like men.Footnote 114

Our finding that military spending responds to war and may, in turn, provide a countervailing pressure to limit women's empowerment during times of militarization resonates well with some existing scholarship rooted in feminist theory that focuses on the formation of gendered power dynamics within and through militarization processes. As Elshtain suggests, when preparing for national defense, men are valorized as “just warriors” fighting and protecting the “beautiful souls” at home.Footnote 115 Norms surrounding women as objects for security forces to protect appear in the construction of the laws of war and the practice of humanitarian intervention. Both view women as potential victims of insecurity while ignoring women's potential as security producers.Footnote 116 MacKenzie and Foster posit that in the midst of insecurity, “masculinity nostalgia” can accompany yearnings for peace and stability.Footnote 117 Militarization perpetuates a number of gender dichotomies, which generally imply men should monopolize protection. During militarization, societies thereby accord men (security producers) more resources and esteem, which are foundations of gendered power and hierarchy. It is not just that masculine characteristics are valued in militaries, but that specific masculine orientations—hegemonic and hyper masculinities—are actively cultivated while feminine and other masculine characteristics are at best marginalized and at worst actively belittled as part of the socialization process.Footnote 118

If militarization perpetuates gender hierarchies, demilitarization can enable the erosion of gender hierarchies. Kronsell notes that in many developed countries, such as Sweden, militaries focus on cultivating peace abroad. While this cosmopolitan orientation has opened up space for gender mainstreaming, gender dichotomies, especially around protection and fighting prowess, remain embedded and a source of gender power imbalance.Footnote 119 Indeed, our findings indicate that (de-)militarization has only a limited role in explaining changes in women's empowerment and should not be read as suggesting that a reduction in militarization is all that is needed to promote gender equality.

Implications and Future Research

While we do not advocate for war as a policy tool, our findings show that war can inadvertently produce social dividends.Footnote 120 The core finding that war is associated with women's empowerment produces a few implications for efforts to reduce gender power inequalities worldwide. One takeaway is that it takes massive upheaval to create the opportunity for improvements toward gender equality. This narrow implication, however, offers little guidance on how to improve women's empowerment and risks turning a blind eye to the suffering of women and men during war. In the case of El Salvador, women's wartime gains resulted in part from the death and disappearances of so many men. Many of the new heads of households were impoverished, and many women (and girls) who became rebels were refugees without husbands or children.Footnote 121 In Liberia, women experienced high rates of sexual violence, maternal mortality increases, and economic burdens from the loss of male heads of households and the destruction of their homes.Footnote 122 Women combatants were also ill-informed about demobilization and often harassed and/or ineligible for DDRR support during the peace-building process.Footnote 123

A more helpful implication is that gender mainstreaming during peace processes can be a powerful tool for cultivating norms and institutions of gender equality. Anderson and Tripp highlight how women's movements have pressed for reforms addressing sources of gender power imbalance to be on the bargaining table during peace processes.Footnote 124 Reforms include legal protections against sexual and gender-based violence, quotas for women's representation in government, and women's property rights reforms. Catalyzed internationally by the women, peace, and security agenda launched with UNSC Resolution 1325, and assisted by international organizations, more and more peace agreements include provisions explicitly related to gender or women.Footnote 125 The mainstreaming of gender and women during peace processes, such that active steps are taken to address the underlying sources of gender hierarchy, is crucial. The findings indicate that the period immediately after war has ended is especially ripe for immediate improvements in women's empowerment, and they also indicate that constitutional reforms and adoptions that occur in the midst of regime change are an important vehicle for change. If reforms that address gender power imbalance are postponed until times of relative peace and after constitutional negotiations have concluded, the window of opportunity for change can be easily missed.Footnote 126 As it stands now, our finding that war can open up space for women's empowerment is conclusive for only the short and medium terms; we cannot rule out the potential for backlash against gains in women's empowerment in the longer term. In addition to making the most out of the opportunity for reform during peace processes, intentional efforts domestically and internationally to maintain the gains in empowerment may be needed to help establish a lasting equilibrium of women's empowerment. For instance, it is imperative that peacekeeping and peace-building efforts take up the mantle of UNSC 1325 and prioritize the inclusion of gender equality as a core component of promoting peace.

Additional analyses in future research will continue to improve our understanding of how a society's security environment affects the level of gender hierarchy. Our study assesses the effects of war and threat up to only fifteen years into the future, at which point the uncertainty surrounding the estimated effects is high. To model even more long-term effects, future studies might aggregate the data to decade or generational-level units of analysis and see how societal threats and gender equality move in equilibrium. A related, useful agenda would be to identify conditions under which women's empowerment gains do persist in the long term. That approach would provide key insight for policy applications, including a more nuanced understanding of the barriers to more permanent gains. Future studies might also consider additional measures of gender equality. The index of women's political empowerment, even though it aggregates three different measures, captures only a limited portion of how gender hierarchy can be manifested and experienced.Footnote 127 Studies might use additional measures of gender inequality to capture the disparate manifestations of inequality, and they also might adopt research designs, including surveys, oral histories, and discursive analysis, which better capture the experiences of women in times of war.

Finally, we recognize the need for an examination of how changes in gender hierarchies intersect in powerful ways with other social hierarchies and sources of inequality. Most straightforward, it would be important to uncover if war can also empower other marginalized social groups, including ethnic minorities and lower classes. Conversely, war might empower women on the backs of men from disadvantaged groups as men from those groups are sent to fight in war at higher rates and are ultimately replaced by women, potentially from less disadvantaged groups. If this is the case, then an unqualified characterization of war as a catalyst for positive change misses more complicated social implications from warfare.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818319000055>.