1. Introduction

Corn (or maize) has been the main food of Mexicans since time immemorial, and it represents today around one half of the volume of food consumption in the country.Footnote 1 However, corn is not consumed as such, but must be processed into various edible products, of which the most common is the tortilla (a flat corn cake). For thousands of years, the labour required to make tortillas and other foods out of corn was carried out manually exclusively by women. All available sources, pre-Columbian ceramics, sixteenth-century codex, colonial and nineteenth-century travel accounts, and twentieth-century ethnographic studies show that an enduring gender division of labour was socially constructed that defined the transformation of corn into food as exclusive female labour, and prevailed for centuries together with the technology to perform it. It was only during the last decades of the nineteenth century that mechanised methods were developed to produce the nixtamal dough (masa) necessary to make tortillas and to shape and cook them, and it took many more decades for these methods to spread all over the country. First, they reached larger cities, such as Mexico City and gradually expanded to smaller towns and rural environments. This step took place earlier in the milling part of the process and later in the process of shaping and cooking the tortillas. Everywhere, when it did, it implied a greater transformation in the lives of Mexican women than any other technological development would produce.

Although a technological change relieved women from a very demanding chore that took most of their long working hours, it also posed a threat to them, since as tortilla production mechanised it also masculinised. However, during the early years of mechanisation, when the shaping and cooking of tortillas remained still largely unmechanised, many women found a window of opportunity in developing this part of the business. Women opened hundreds of manual tortilla shops (tortillerías) that employed large numbers of women.

Since the mechanisation of the milling process in Mexico City coincided with the Mexican Revolution (1910–1920) and its aftermath, manual tortillerías offered women a means of survival when, in addition to being displaced by mills in the production of masa, many women were displaced from their villages and forced to become heads of their families. Women's entrepreneurship was key to opening hundreds of manual tortillerías that employed mostly women. It can be considered as a survival strategy during a period of economic, social and political turmoil, coupled with technological change.Footnote 2 However, lack of capital restricted female entrepreneurship to the unmechanised tortilla-making microbusiness, while men dominated the mechanised milling sector that required more substantial investment and was more profitable. At the same time, a wide gender wage gap opened since mills paid higher wages than unmechanised tortillerías, and they employed a larger share of male labour than tortillerías.

Several decades ago, Dawn Keremitsis and Arnold Bauer unveiled the importance of this crucial technological change in the lives of Mexicans and particularly of women.Footnote 3 Some years later, Jeffrey Pilcher explored the topic further, emphasising the cultural aspects.Footnote 4 This article seeks to delve in greater depth into the consequences of the early phase of the mechanisation of the tortilla-making process. It explores how mechanisation took place in Mexico City during the 1920s by analysing hundreds of questionnaires carried out by employees of the Department of Labor in 1924 that reported on the capital, labour and working conditions in several mills and tortillerías. Studying the way this transformation took place in Mexico City during the 1920s is particularly enlightening since it was one of the first sites where the mechanisation of masa started.

The article is divided as follows. First, it provides an overview of the tortilla production process and its technological changes. Sections 2 and 3 then explore the way nixtamal mills and tortillerías operated in 1924. Part 4 examines gender wage gaps and the possible reasons behind them. Finally, conclusions are provided.

2. Tortilla production and technological change

Corn was the basis of human consumption in what now comprises Mexico, as well as North America and Central America, during pre-Hispanic times. The domestication of corn took place through a long process between 12,000 and 7,500 years ago in the central south of what now is Mexico.Footnote 5 Together with the domestication of corn, pre-Hispanic Americans discovered a peculiar form of processing corn, nixtamalisation, which requires boiling the corn with lime, and letting it rest for several hours. Nixtamalisation makes corn wholly digestible and increases its nutritional value. Without this processing, populations that eat corn as a large share of their food intake may develop a fatal disease called pellagra. This wet mixture was then ground on a grinding stone to form a masa. Nixtamal dough could be used in several ways, but the most common was in tortillas.

The production of tortillas requires arduous, slow and constant work that has many phases, including:

1. Threshing the corn.

2. Nixtamalisation (precooking the corn with lime).

3. Grinding of the nixtamal to make dough.

4. Extra grinding before shaping the tortilla.

5. Shaping the tortilla.

6. Cooking the tortilla.Footnote 6

Archeological evidence shows that some five thousand years ago both in ancient Egypt and in Mesoamerica, women ground cereals in a similar way, bent over grinding stones in Egypt or over its New World equivalent, the metate, in Mexico. However, the techniques of milling and grinding and the gender division of labour in those activities differed radically before the middle of the first millennium B.C. In the Eastern Mediterranean, the lever and hourglass mills, querns and revolving millstones were adopted to process wheat. These were adapted by the fifth century B.C. to use animal power and then water power. During the last century before the Common Era, this new technology spread from the Eastern Mediterranean through Greece into the Roman world and then outward to the rest of Europe. During the Middle Ages, water- and wind-powered grain mills were further developed.Footnote 7 With the Conquest, the technology accompanied these new grains to the New World. However, in Meso-America, the metate hand grinder, present in Teotihuacan before 3,000 B.C., was unchanged for the subsequent five thousand years. Well into the late nineteenth century, it remained the sole instrument for the production of the stuff of life for millions of Mexicans and Guatemalans, and the preparation of the basic staple food remained decentralised, at the level of the household.

Before the mechanisation of tortilla production, women spent a large share of their long working day in the different chores of tortilla making. This means that for the past several hundred years while women in wheat cultures spent perhaps no more than 3–4 hours a week on bread (and less if bought from the village baker), in maize cultures, women worked at least 35–40 hours a week on tortillas alone.Footnote 8 Moreover, since the nixtamal undergoes a process of fermentation, neither the nixtamal nor the dough can be kept for several days so tortilla-making needs to be carried out daily.

A 1902 newspaper article called ‘The Slavery of Metate’ stated:

The metate has been a curse for the Mexican people, a curse on our poor people which has been passed down from generation to generation, from the most remote past until the present day. The metate has been a form of slavery for the Mexican woman who has spent her energy, her health and her time on the wretched task of grinding nixtamal day after day, so that her entire family can eat breakfast, lunch and dinner. No matter whether her family be large or small, they consume dozens of tortillas at every meal [ … ] Unhappy women of Mexico! It breaks our hearts to see them bent double, with their hands, knees and feet hardened by work that has such a poor reward.Footnote 9

Among peasants and workers, tortillas were made at home daily by the women of the family who had to wake up before dawn in order to have the tortillas ready for breakfast. It was usual that at noon, they would take warm tortillas along with the rest of the lunch to the sites where the men of the family were working. More well-off families, as well as ecclesiastical or military institutions, hired a servant devoted to making tortillas, called tortilleras.Footnote 10 An English traveller who visited Mexico City in the 1890s observed this among wealthier families where during mealtimes the tortillera ‘must serve each person at the table with hot tortillas as fast as they can eat them’, since even ‘the poorest Mexican thinks it a hardship to eat a cold tortilla. And he is right, for it is as tough as shoe-leather’.Footnote 11

Mills for grinding cereals were not suitable for grinding the corn to produce tortillas since it was not ground dry, as are other grains. A particular machine needed to be developed that was able to grind the wet nixtamal without getting stuck. The first patents were developed during the 1850s, and more patents appeared sporadically between then and 1890. During the last decade of the century, a spurt of invention took place, and more than 13 new patents for improving the grinding of nixtamal were registered; during the first decade of the twentieth century, more than 78 new patents were registered.Footnote 12

However, it took several decades before the Neolithic technology of the metate began to be replaced by the electric, steam and gasoline-powered grist mill (the molino de nixtamal).Footnote 13 The same English traveller cited above, who described the process for making tortillas he observed in his visit, remarked: ‘This system of preparing the food has existed from time immemorial, and today the Mexican eats the tortillas made in the same way as in the time of his Aztec and Toltec forefathers’.Footnote 14

Technological development prompted the growth of commercial nixtamal mills that could produce masa of reasonable quality at a good price during the early years of the twentieth century. Moreover, since the more efficient mills worked with electricity, their spread took place along with the diffusion of electricity through the country.

The same newspaper article of 1902 went on to explain:

We are delighted to witness the diffusion of the nixtamal mill, which happily is now in use from Guerrero to Nueva León, as yet on a small scale, but increasingly displacing the accursed metate. How we have longed for the arrival of this day, so blessed for our fellow female citizens of the humblest class! [ … ] Blessed invention! It comes to liberate the female sex of our land, allowing her without doubt to dedicate her energies to a thousand tasks which, even if they are as arduous as that of grinding metate will still be more productive.Footnote 15

The last part of the process for making tortillas – shaping the dough into tortillas and baking them – took longer to become generally mechanised. The first patent of a very rudimentary version of this machinery appeared in 1899, developed by Luis Romero. However, the quality of the tortillas it produced was very poor.Footnote 16 The few mechanised tortillerías that existed during the first decade of the twentieth century produced tortillas mostly to satisfy the demand of hospices and prisons. Another newspaper article of 1902 indicated:

The delicious smelling and hot tortilla, which emerges from the pan light and airy to become the classic taco, the Aztec sandwich, is threatened with disappearance, with being replaced by a corn poultice, tasteless and odourless, made according to factory rules, but against all culinary ones of ancient times, rules which had been preserved by a conquered race.Footnote 17

Throughout the following decades, new patents for the forming and cooking of tortillas appeared sporadically. In 1919, Enrique Espinoza patented the first machine that incorporated running bands with gas burners which went over and below the bands. However, the tortillas produced by this machinery were still very thick and lacked flexibility, which were significant problems, since the way Mexicans eat tortillas requires that they can be folded around other foods without breaking. In 1921, this process was further improved with the system developed by Luis Romero. However, it was not until 1947, when Fausto Celorio patented a machine to make and cook tortillas, that the quality improved significantly.Footnote 18 New versions with different trademarks of this machine have been developed to this day, but improvements have not been significant.

3. The first nixtamal power grinding mills and ‘Tortilla Factories’ in Mexico City

The first nixtamal power grinding mills began to be established in Mexico City during the first decade of the twentieth century, and they spread increasingly during the following decades. By 1913, there were 72 nixtamal power grinding mills operating in Mexico City which employed 200 women and 85 men.Footnote 19 Eleven years later, in 1924, there were 147 mills that employed 555 workers.Footnote 20 By 1930, there were already 291 mills operated by 862 workers: 451 men, 405 women, and 6 children.Footnote 21 By this year, the mills of Mexico City produced 20 per cent of the masa produced mechanically in the whole country, although the city only represented 7.5 per cent of the total population.Footnote 22 In contrast to mills established in rural environments that processed nixtamal brought by the public to be milled into masa for a fee, mills in Mexico City acquired sacks of corn and lime that they transformed first into nixtamal and then into masa for sale. They carried out phases 2 and 3 of the tortilla production process described in the previous section.

The establishment of nixtamal mills formed part of a more extensive process that took place in Mexico City at the turn of the twentieth century by which, as John Lear remarks, a few companies organised around large, semi-mechanised workshops increasingly dominated many crafts. This generated a high concentration of ownership and a deskilling of the labour force. In addition to corn grinding, this took place in shoemaking, baking, metalworking and printing. Overall, the effect was a drop in the relative importance of manufacturing employment in Mexico City, declining from 37 per cent in 1895 to 33 per cent in 1910.Footnote 23

Women made up 35 per cent of the paid labour force of Mexico City in 1910, according to the population census, far above the national average of 12 per cent.Footnote 24 The diffusion of the nixtamal mills displaced many of them. According to the censuses, there were 1,182 molenderas (female grinders) in Mexico City in 1895, 2,836 in 1900 and only 349 in 1910. From the 1921 census on, the occupation of molendera disappeared altogether.Footnote 25 The censuses also report that in Mexico City, there were 3,763 tortilla makers (tortilleras) in 1895, 2,604 in 1900 and 1,813 in 1910.Footnote 26 However, these numbers refer solely to women exclusively devoted to these tasks for commercial purposes. Before milling was mechanised, most corn was ground, and tortillas made at the household level and were thus not reported in the census as an occupation.Footnote 27 Nonetheless, it is possible to estimate the number of women that must have been required to make the tortillas consumed daily in Mexico City using the calculations made by Miguel María de Azcárate in the 1830s. According to him, every person ate eight tortillas daily, which required 1.5 pounds of masa. He considered that the most efficient and hard-working woman could grind 24 pounds of corn daily.Footnote 28 Since in 1900 Mexico City had 541,516 inhabitants,Footnote 29 using Azcárate's assumptions, 4,332,128 tortillas would have been required to feed its population daily, which production would have required the work of 33,845 women.

Teresa Rendón and Carlos Salas observe that the vast majority of women working in the food manufacturing industry in Mexico between 1895 and 1910 were corn-grinders (molenderas). According to them, the number of women working in the food industry in the country increased between 1895 to 1910 from 247,020 to 330,791, but then declined drastically to 37,919 in 1921, and to 16,650 in 1930, which they consider could have been a result of the expansion of nixtamal mills. Rendón and Salas also suggest that the decrease in the number of women working in domestic services from 184,255 in 1910 to 131,970 in 1930 could have been related to a technological change in masa production.Footnote 30 Nixtamal mills thus had a significant negative impact on women's labour participation in these occupations.

Since pre-Hispanic times, the production of masa had been an exclusive female job; once production was industrialised, it was dominated by male labour. Only a few women were employed, segregated into a limited set of activities that did not require the use of machinery. The mechanisation of the process broke the long-established social stigma against male participation in masa and tortilla production, as happened in other types of work, such as cloth-making, that were considered female labour before mechanisation.Footnote 31 While in 1913 women represented 70 per cent of nixtamal mills' labour force, by 1921 they were only 44 per cent. By 1930, this figure increased slightly to 47 per cent, but fell to 40 per cent in 1935.Footnote 32

The masculinisation of masa production must have been partly a result of prejudice about the capacity of women to work with machinery, and also a result of the muscular strength such work required, given the heavy loads that needed to be carried once the masa was produced on a large scale, as the description of the process by a medical inspector of the Department of Labor during the early 1920s suggests.Footnote 33 According to his account, to prepare nixtamal, water was poured into large buckets with a capacity of more than 1,000 liters each. A constant current of vapour heated the water to a temperature of 68 degrees centigrade. Then the workers poured into it 750 kilos of clean corn grain, together with 3 kilos of lime. The mixture had to remain in maceration for six hours at a temperature that should not reach 100 degrees centigrade. Then it was taken out, allowed to cool down and taken to another device with a sloping plane, where it was washed until the corn became entirely white and stripped of its outer shell. Finally, it was taken to the mill where it was ground into masa that was then subdivided for sale. The mill visited produced around 1,000 kilos of masa daily.

The establishment consisted of two areas, one where the corn was prepared to be ground, and another, where the mill was located and sales were carried out. The inspector considered the conditions in the first room could be damaging to the health of the workers since they experienced abrupt temperature changes. According to this account, this room had little light or air. In this room, ‘the men who worked those rude chores’ were barefoot, so they frequently experienced rheumatic problems. The other room, where the mills were located, was better lit and ventilated, and it was free of dust. It was in this room where most of the women worked, weighting and selling the masa.Footnote 34 Thus, labour was segregated among the sexes, not only according to occupations but also in the workspace.

The information gathered on 86 nixtamal mills by employees from the Department of Labor in 1924 enables us to understand better the way nixtamal mills operated. These surveys were part of the project of the Workers' Census that also included other sectors.Footnote 35 The mills for which information is available in this source represented over half of the total mills established by 1924 according to a report of the Department of National Statistics.Footnote 36

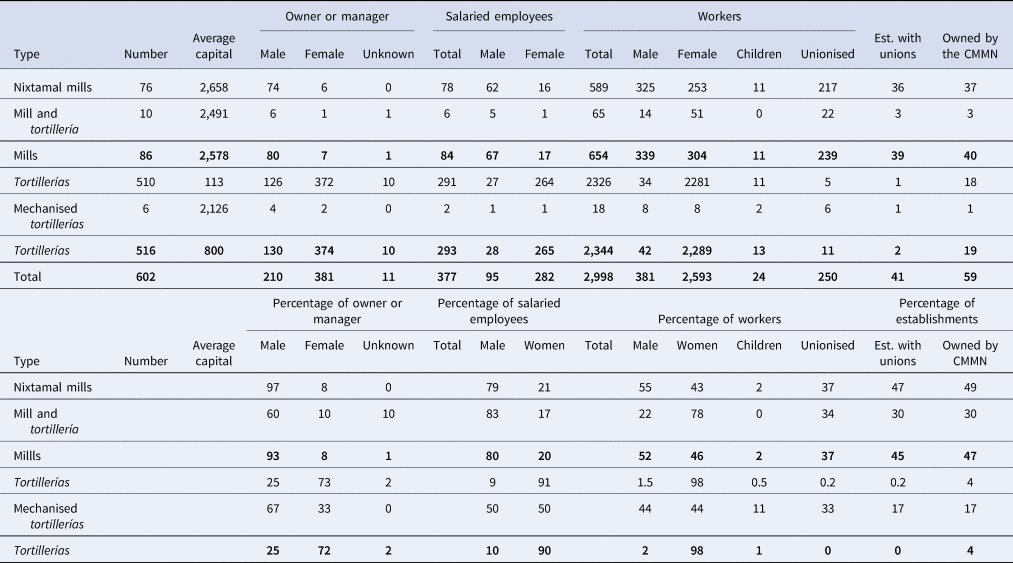

According to these surveys, nixtamal mills were a relatively small business; they had on average a capital of 2,578 pesos (around 1,300 US dollars of the time), and they hired on average one salaried employee and eight workers (see Table 1).Footnote 37 For equipment, they usually had a boiler of between 5 and 20 horsepower, large tubs where they boiled the corn, one or two mills to grind the mixture run by one or two engines of between 10 and 25 horsepower that operated with diesel or electricity. Most of them (80) were owned or managed by men, while only 7 mills were owned or managed by women. The mills run by women had relatively less capital (see Table 2).

Table 1. Nixtamal mills and tortillerías in Mexico City, 1924

Source: Archivo General de la Nación, México, Fondo del Departamento del Trabajo, Sección Estadística, Cajas 776 exp. 1 y 2 y caja 777, exp. 1 y 2, ‘1924, Distrito Federal, Censo Obrero, correspondencia y cuestionarios mensuales relativos a los molinos de nixtamal’.

Table 2. Share of establishment, employees and workers by the gender of owners or managers

These mills hired 84 salaried employees, of which 67 were men and 17 were women (20 per cent) (see Table 1). The average daily wage of male salaried employees in this sample was 5.25 pesos (see Table 3), whereas that of women was 2.56 pesos, that is less than half the average wage of men. Mills also employed 654 workers, of which 339 were men (52 per cent), 304 were women (46 per cent) and 11 were children (2 per cent) (see Table 1). While the average daily wage for male workers was 2.43 pesos, women workers earned, on average, 1.73 pesos (see Table 3). Around 45 per cent of the workers of nixtamal mills belonged to the Millers Union (Sindicato de Molineros) that formed part of the largest confederation of the time, the Mexican Regional Workers' Confederation (Confederación Obrera Regional Mexicana, CROM) (see Table 1). Wages in these mills were around 4 per cent higher than in non-unionised mills (see Table 4). Nixtamal mills operated on average seven days a week and eight hours per day, although a few of them operated 12 hours per day.

Table 3. Average wages of employees and workers in mills and tortillerías, 1924

Source: See Table 1.

Table 4. Average wages of employees and workers in unionised establishments, 1924

Source: See Table 1.

In terms of marital status, around half of the male salaried employees and one-third of the male workers were married (see Table 5). In contrast, only 15 per cent of female salaried employees and 11 per cent of the female workers were married. The surveys also report that there were 23 sons or daughters of male salaried employees, and three of female salaried employees, as well as 93 sons or daughters of male workers and 39 of female workers (see Table 5). The separate registration of sons or daughters suggests that they were not hired by the mills but were helping their parents without a wage. These figures indicate that salaried employees were more likely to have daughters or sons working with them than were workers and that this took place more often among male than among female salaried employees and workers (see Table 5). This suggests that many mills operated as family businesses, and that male employees and workers had more leverage to bring their children along to work than women.

In spite of the relatively small capital nixtamal mills required, and the basic technology they involved, nixtamal mills had a high concentration of ownership. By 1915, the Compañía Mexicana Molinera de Nixtamal (CMMN) owned by the Spaniards Moisés and Benjamín Solana, owned 100 of the 130 total corn mills in the city, and a few years later, a Labor Department inspector observed that the company could set the price of masa in the city at will.Footnote 38 In 1924, 119 of the 147 mills operating in Mexico City (81 per cent) belonged to this company.Footnote 39 Of the 88 mills visited by the Department of Labor, 39 (51 per cent) were owned by the CMMN. Thus, the percentage of firms that belonged to this company is under-represented in our sample. In the CMMN mills, around 50 per cent of the workers were unionised, and they represented 87 per cent of the unionised workers in all mills. Since the mills that belonged to this company were more highly unionised, but they are under-represented in our sample, the actual percentage of unionised workers must have been higher. The reasons behind the high concentration of mills in this company remain to be explored.

4. The first Tortillerías

Before the production of masa was mechanised, tortilla shops – tortillerías – that carried out the whole production process manually were established in urban environments such as Mexico City. Early tortillerías hired several women to make the nixtamal, grind it and make tortillas, as the account by an English traveller during the late nineteenth century cited earlier indicates.

Here and there in the side streets, we hear the sound of patting hands and know that a tortilla house is not far off. In a dingy, foul-smelling room squat several women in tattered, dirty, garments, grinding the maize; others, on their knees, are making the cakes, while at the charcoal fire stands the cook. ( … ) The implements used are a flat, rough stone, which stands in a sloping position on three legs in front of the grinder, and a heavy metate held in the grinder's hands. Taking a handful of maize, the woman sprinkles it with water, mixed with a little lime, and grinds it with the metate to the bottom of the slab. She then replaces it at the top, and again moistens and grinds it, repeating the process until it has become a compact white paste. This she hands to the maker, who kneads it into a little round lump, which she pats between the palms of her dirty hands until it has become a thin round wafer. The cook then takes it, toasts it slightly on both sides, and the tortilla is ready to be eaten.Footnote 40

The appearance of tortillerías in urban environments reflects the fact that there were increasingly fewer homes where a woman would spend several hours carrying out this chore, either because they had other jobs or because they had enough income to prefer using their time on other tasks, whilst not being rich enough to hire servants to make tortillas. Migration and urban expansion also made it more challenging to eat at home or to rely on a woman to bring warm tortillas together with the rest of the lunch to family members on the job, as had been customary in rural environments.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, when nixtamal mills began to spread in Mexico City, tortillerías no longer made the masa but bought it from the mills and specialised in the last part of the tortilla making process, that is from phase 4 to phase 6 of the process described in the beginning of this paper.Footnote 41 The spread of nixtamal mills in Mexico City coincided with the Mexican Revolution, which started in November 1910. Although the end date is not precise, violence began to abate by 1917. Although internal migration to Mexico City had been considerable since the late nineteenth century, and had distinguished itself from that of other areas of the country in that the sex ratio favoured women, it increased as a consequence of the Revolution.Footnote 42 Several villages surrounding Mexico City were affected by the war, especially in the state of Morelos – the stronghold of Emiliano Zapata – which faced severe episodes of warfare and repression.Footnote 43 Many people from these villages fled to Mexico City to find refuge from the war. By 1922, it was calculated that around 100,000 people had gone to Mexico City during the revolutionary war.Footnote 44 Thus, while the Mexican population decreased by 5.4 per cent between 1910 and 1921, the population of Mexico City increased by 25 per cent and that of Morelos decreased by 42.4 per cent. If we consider the more extended period between 1910 and 1930, for which census data are more reliable, Mexico's population increased by 9.2 per cent, that of Mexico City by 70.6 per cent and the population of Morelos decreased by 26.5 per cent.Footnote 45 More women emigrated than men, so that between 1910 and 1930, the female population in Mexico City increased by 76.7 per cent and that of Morelos decreased by 27.1 per cent, while figures for men were 63.8 per cent and 25.9 per cent, respectively.Footnote 46 As a result, in 1930, men represented less than 45 per cent of Mexico City's population.Footnote 47

Many of these immigrants were women who had to find a means of survival in Mexico City. An account from a woman from Tepoztlán, Morelos, who was interviewed between 1947 and 1948 by the anthropologist Oscar Lewis when she was 40 years old, suggests that several women must have found a means of subsistence in making and selling tortillas, atole (a drink made with nixtamal dough), or tacos (a rolled tortilla filled with other food). She recalled,

My mother was a widow. When I was nine, we went to Tacubaya [a neighborhood of Mexico City] because it was the time of the Revolution. My mother borrowed three pesos and made atole and tacos and sold them. She did well the first year. Then she prepared meals for 190 factory workers. I made tortillas when I wasn't going to school. I went to school for four years, and each morning, I got up at 5:00 A.M. and ground corn, and made coffee for my mother, brothers, and sister ( … ). I also made the tortillas for the family for lunch and supper. My mother hired three women and a boy to help her with her work, and she made a lot of money. After four years, she took us back to Tepoztlán because she didn't want us to grow [up in the wrong way].Footnote 48

This testimony provides a qualitative complement to the quantitative data that will be analysed below, data that show that women established a large number of tortillerías during this period, which in turn gave many jobs to other women. Several women found in tortilla production a way out of their difficult situation. Opening manual tortillerías and working in them can be considered a survival strategy since it allowed many women to support their households in a critical context when, as a consequence of the Mexican revolution and technological change, many had become heads of their families and found few alternative jobs. As Michael Redclift has acknowledged, surviving usually means accommodating to structural changes rather than resisting them, since resisting for too long carries the risk of not surviving.Footnote 49 However, strategies which enable groups of people to survive their incorporation into urban, industrialised societies often imply cultural forms of resistance, through the construction of ethnic and gender identities and social relationships, which reduce the impact of total assimilation or exclusion. Manual tortillerías did not only enable many women and their households to survive physically but also helped them to remain involved in a job that had historically been theirs, for at least a while longer.

Whereas women had been largely excluded from masa production as a result of mechanisation, the shops that made and sold the finished product, the tortillerías, remained their territory. The data collected by the employees of the Department of Labor in 1924 who visited 526 tortillerías allow us to take a closer look at how tortillerías operated. Most of them, 520, produced tortillas manually, while only six were mechanised. Only ten tortillerías were integrated into a mill. The 510 tortillerías that produced tortillas manually and were not part of a mill were tiny endeavours, with an average capital of only 113 pesos, or around 4 per cent of the average capital of mills (see Table 1). Their equipment was very rudimentary, generally a charcoal stove (brasero), some metates, a scale and a table. Only around half of them hired a salaried employee, and they generally employed around five workers, mostly women, to make the tortillas called ‘tortilleras’ or ‘palmeadoras’. Some also hired a woman to weigh the tortillas and sell them to the public, a ‘pesadora’ or ‘despachadora’. Most of the workforce in the manual tortillerías was female. In 1924, they hired 264 women as salaried employees (91 per cent), and 2,281 as workers (98 per cent), while only 27 men were hired as salaried employees (9 per cent) and 34 as workers (1.5 per cent) (see Table 1).

Most women working in manual tortillerías, either as salaried employees or as workers, were single. Of those who reported their marital status, only 29 per cent of the female salaried employees and 16 per cent of the female workers in tortillerías were married (Table 5). Although they were still a minority, these shares were larger than in nixtamal mills. Four female salaried employees (2 per cent) were widows. In contrast, most male salaried employees (82 per cent) and workers (72 per cent) in tortillerías were married. Figures show that there were 67 sons or daughters of salaried employees and 428 of workers. As in mills, salaried employees were more likely to have sons or daughters working with them than workers. However, it was more likely that both groups had sons or daughters working with them than in mills (see Table 5). This suggests that more tortillerías operated as family businesses than mills. Moreover, the fact that more workers brought their sons and daughters to help them may have been a result of their lower income. A smaller share of their children are likely to have gone to school, fewer workers could afford to have someone to take care of their children at home and more of them must have required their children's help to support the family. This was facilitated by the fact that most jobs in tortillerías were paid by the piece.

Although the 1917 Constitution had stipulated that the work-shift should be limited to eight hours and the working week to six days, this was not complied with by many tortillerías. They worked on average 8.14 hours a day; six worked for 9 hours, three for 10 hours and two for 14 hours daily. Most of them worked seven days a week, with only 127 tortillerías reporting that they had a day of rest. According to Susie Porter, employers often sought exemption from Sunday rest laws by arguing that women's work was more akin to domestic duties and that women's lack of morality disqualified them from the protection of the law. Mr. Agrove, a tortillería owner who had been repeatedly found in violation of the Sunday Law, argued in his defence that since the tortilla was an item of primary consumption, as its producer, he should be exempted from the Sunday Law. As an additional excuse, he argued that his female workers were unreliable and of questionable morality, and rarely completed a continuous week of work.Footnote 50

There was practically no unionisation in tortilla shops. Only five of the tortilla workers were unionised (0.2 per cent), including the tortillerías that worked together with a mill, as well as the mechanised tortillerías. They all worked in tortillerías that belonged to the Compañía Molinera Mexicana de Nixtamal (see Table 1). During the following years, women working in tortillerías and mills would carry out a critical struggle to become unionised and form their own unions. In Mexico City, this process lagged behind those of other cities such as Veracruz, where, by 1919, women had already organised a Union of Female Nixtamal Mill Workers (Sindicato de Obreras Molineras de Nixtamal),Footnote 51 or Guadalajara, where, in 1926, a Union of Male and Female Workers of Nixtamal Mills (Unión de Trabajadores y Trabajadoras en Molinos de Nixtamal) was formed. In 1930, women in this union decided to split away, creating the Union of Female Workers of Nixtamal Mills (Unión de Trabajadoras en Molinos de Nixtmal).Footnote 52 The strength of the CROM in Mexico City was likely behind this delay since studies for other sectors have shown that it marginalised women.Footnote 53 A better understanding of this issue would require further research that goes beyond the scope of this article.

Most of the unmechanised tortillerías, 75 per cent, were owned or managed by women. Many must have been family businesses since one-third of them indicated that their owner, one family member or both, worked in them. Female-run manual tortillerías hired almost exclusively women and hired a larger percentage of female labour than those run by men. As with nixtamal mills, tortillerías owned or managed by women had a lower capital investment than those run by men (see Table 2). Wages in tortillerías, for salaried employees and workers, were around one-third of those earned in nixtamal mills. Moreover, salaries for female salaried employees and workers in tortillerías were about 40 per cent of those of men (see Table 3). Tortillerías were less concentrated than the mills. The CMMN owned 18 manual tortillerías that worked as separate endeavours, and three that were integrated with mills.

Only six mechanised tortillerías were operating in Mexico City by 1924, one of which belonged to the Compañía Molinera Mexicana de Nixtamal. Mechanised tortillerías were larger businesses; they had on average a capital of 2,126 pesos, very close to that of nixtamal mills. One of them indicated that it had two machines to shape and cook the tortillas that were moved by two engines of one-quarter horsepower each. Around two-thirds of these tortillerías hired one salaried employee, and on average, they hired between two and three workers. Instead of recruiting women to make the tortillas, they hired a machine operator (maquinista). One of them also had a delivery man (repartidor) and a helper. In total, they hired two salaried employees and 18 workers. Their workers' wages were similar to those of nixtamal mills, well above those of manual tortillerías (Table 3). In mechanised mills, all male and half of the female salaried employees were single, while all the workers were single. None had children or daughters with them (see Table 5).

Mechanised tortillerías were owned or managed mostly by men (67 per cent), and although their percentage of female salaried employees (50 per cent) and female workers (44 per cent) was higher than that in mills, it was lower than that in unmechanised tortillerías (see Table 1). This indicates that as more tortillerías became mechanised, the share of female owners or managers, employees and workers would diminish in the business of making tortillas.

5. The gender wage gap in tortilla production

As Susie Porter has shown, although women's participation in the Mexico City industrial workforce shifted between 1879 and 1930 from concentration in a small number of female-dominated occupations to a wide range of work in mixed-sex factories, significant gender wage gaps prevailed. Women's wages were lower than those paid to men, whether in large factories or small workshops. This was partly a result of the fact that women were generally employed in low-wage jobs while men worked in higher-paying positions. In the textile industry, for example, men were employed as weavers with an average wage of 1 peso per day in 1896, while women were employed in carding and were paid 50 centavos, or half as much. In the domestic production of shawls (rebozos) in the 1920s, men were hired as weavers and paid between 1.50 and 2 pesos a day, while women were employed as spinners and paid between 40 and 80 centavos a day, or as embroiders and paid between 75 centavos and 1.25 pesos a day. However, even when employed in the same job category, women frequently earned half of what men earned, as was the case among mattress makers.Footnote 54 Similarly, in agricultural production women earned as wage labourers half or less of what men earned for the same work, as salaries from Oaxaca in 1907 show.Footnote 55

Male and female wages in mills and tortillerías in Mexico City by 1924 show that a similar situation prevailed (see Table 3). Women received lower wages than men as a result of the different jobs they undertook. Occupations were defined in terms of gender, even by the name given to them in the workers' census. Thus, for example, tortilleras or palmeadoras had the female gender in the occupation's title, while peón or nixtamalero had the male gender in the title. Although there were some exceptions, there were very few occupations that were carried out by both genders. While 19 per cent of workers in ‘female occupations’ laboured in jobs with a higher pay such as encargada or cajera, 51 per cent of men worked in such occupations, such as nixtamalero or maquinista (see Table 6 and Tables A1–A3).

Table 6. Employment and wages of occupations in mills and tortillerías by gender, 1924

Notes: Male and female occupations were defined as such by the main gender.

The occupations included were those that comprised five or more workers.

Occupations considered as high pay for women were those who paid more than 1 peso per day, and for men, those who paid more than 2 pesos per day.

Source: See Table 1.

However, the wage gap was also a consequence of the way occupations were distributed among mills and tortillerías. The problem was that the share of workers in ‘male occupations’ was more abundant in the businesses with higher capital and more mechanisation, such as nixtamal mills and mechanised tortillerías, that paid higher wages, and the share of workers in ‘female occupations’ was concentrated in manual tortillerías, that paid lower wages. Moreover, most ‘female occupations’ were piece-rate jobs. According to Susie Porter, the prevalence of piece-rate work for women contributed to their low wages because after the passage of minimum wage laws, employers manipulated piece-rate wages to avoid compliance.Footnote 56 Even in similar positions, such as salaried employees in mills, men earned wages twice that of women.

6. Conclusions

The mechanisation of the production of tortillas shows some similarities with the early development of the textile industry. As has been described in several studies, when the textile industry began its development, the spinning part of the process was the first to be mechanised, allowing many weavers to continue carrying out the manual process, with the benefit of acquiring the yarn more cheaply from the spinning mills. Very soon, however, as the weaving part of the process became mechanised as well, it caused the laying-off of many of the former weavers.Footnote 57 In the mechanisation of tortilla production, a parallel process took place. Initially, the milling process was mechanised but not the process of shaping and cooking the tortillas. Many women continued to work in this last part of the process, and many owned or managed tortillerías. However, as mechanisation reached the tortilla-making part of the process, these businesses became increasingly controlled and operated by men.

The early development of the tortilla industry is in line with what Ester Boserup regarded as the main consequences of early industrialisation for women.Footnote 58 Industrialisation wiped out the home industries in which most women worked, and women's participation in industrial employment declined, remaining largely on the margins in low skilled and poorly paid work. Nonetheless, it is clear that when, as a consequence of mechanisation, the production of tortillas that had historically been a woman's endeavour, became increasingly masculinised, women did not remain passive. They found ways to continue participating in this production.

The mechanisation of milling took place during the same years that the revolutionary war forced many women to become the heads of their households, and in many cases to flee violence in their hometowns and find refuge in cities. Through this process, the population of Mexico City increased as well as the share of women in it. The testimony gathered by Lewis together with the quantitative data analysed attest to the significant number of women who found a way to support themselves and their families as owners of or workers in tortilla shops. It is remarkable that so many entrepreneurial women established tortillerías, providing jobs to many more women. This can be considered a means of survival in a context where a technological change was marginalising women. It was also a means to cope with the great difficulties that had caused the revolutionary war.

The fact that there were so many women who owned or managed manual, non-integrated, tortillerías but so few who owned or managed nixtamal mills or mechanised tortillerías tells that they faced severe difficulties in raising the much higher amounts of capital that were required to establish these last two types of businesses. This could have been a result of larger restrictions on women borrowing money through formal or informal capital markets. It could have also resulted from the fact that they were less wealthy, either as a result of being less educated and able to obtain only lower-paying jobs, as a consequence of heritage traditions that placed them at a disadvantage, or because these entrepreneurial women generally belonged to less well-off families than the men who established these types of businesses.Footnote 59 In any event, it suggests that the low participation of women as owners or managers of mills and mechanised tortillerías was not due to lack of entrepreneurship but as a result of lack of capital and education.

Appendix

Table A1. Female occupations

Table A2. Male occupations

Table A3. Both gender occupations