The study of political communication in Canada commonly considers the news media to be professionalized and nonpartisan. Historical accounts detail how these media, although once sponsored by political entrepreneurs whose newspapers focused on opinionated journalism, took a commercial and professional turn during the early twentieth century in Canada (Brin et al., Reference Brin, Charron and de Bonville2004), as well as in the United States (Williams and Delli Carpini, Reference Williams and Delli Carpini2011). Hallin and Mancini's (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004) seminal comparative study also classifies the Canadian media system as one of the least politicized in the Western world.

The thesis put forth by Hallin and Mancini (hereafter, H&M) is that media systems in Western countries are interconnected with the political systems within which they evolved. Using a comparative study of 18 countries in North America and Western Europe, they suggest that these countries can be classified into one of three types of media systems: the Polarized Pluralist (or Mediterranean) model, the Democratic Corporatist (or Northern European) model and the Liberal (or North Atlantic) model.

The degree of differentiation between the political and news media systems constitutes a fundamental distinction between these ideal types. H&M associate the Canadian media system with the Liberal model,Footnote 1 which is characterized by, among other things, a neutral commercial press and public broadcaster and an independent journalism culture (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 67, 240). The authors acknowledge, however, the parsimonious nature of their characterizations, which is an issue with any ideal-type construct. They recognize that some news organizations in Liberal media systems—such as Fox News in the United States and the National Post in Canada, as well as some radio programs—are more partisan, but they treat them as exceptional cases.

H&M also make clear that national media systems are not homogeneous and that regional variations do exist in some countries (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 71). Canada's media system could be one such case. In their assessment, H&M stressed the distinctiveness of the Quebec media environment, suggesting that it may be more politicized than it is in other Canadian provinces. In short, H&M put forward the idea that Quebec might be a distinct subnational media system. Is that the case?

In this article, we test H&M's hypothesis about regional differences within Canada and, in particular, the existence of a Quebec media subsystem. We use original data from the Canadian Media System Survey (see online Appendix A), the first expert survey in Canada of its kind, tapping approximately 200 experts from all 10 provinces. Our findings do not support H&M's hypothesis of regional variations between Quebec and other provinces. However, this study sheds light on the diversity of ideological and political orientations of Canadian news media, as perceived by experts. These findings have important implications for research on subnational media systems, as well as for Canadian political communication.

Context, Theory and Conceptual Considerations

National media systems are the product of specific historical contexts and political traditions that influence the evolution of journalistic cultures and media markets, as well as the role played by the state in defining, for instance, models of broadcast governance and the regulations governing the media (Hallin and Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004; Hardy, Reference Hardy2008). Comparative research on media systems, their characteristics and influences is a relatively recent endeavour. Its beginning is often associated with the publication of Four Theories of the Press, in which Siebert et al. (Reference Siebert, Peterson and Schramm1956: 1) argue that “the press always takes on the form and coloration of the social and political structures within which it operates.” In the following decades, this normative classification of media systems remained highly influential, although it was also criticized (see, for example, Nerone, Reference Nerone1995).

The publication of H&M's Comparing Media Systems in 2004 is viewed as a pivotal moment in almost half a century of typological analysis of media systems. For many, it signalled an empiricist turn in this subfield, which departed from the “normative, Cold War–induced” foundation of earlier approaches (Seethaler, Reference Seethaler and Moy2017). While some criticized H&M's work, calling it “fuzzy, impressionistic and unscientific” unless tested rigorously (Norris, Reference Norris2009: 334), others celebrated it as groundbreaking (Patterson, Reference Patterson2007; Hardy, Reference Hardy2008). As Voltmer (Reference Voltmer2013: 119) stresses: “Hallin and Mancini's book has hugely revitalized both theoretical and empirical scholarship on the origins and forms of media system structures across different political contexts.”

In the years following the publication of H&M's book, several researchers took up the task of testing various aspects of their proposals or used their conceptual framework to assess national and supranational media environments in the Western hemisphere and beyond (see, for example, Brüggemann et al., Reference Brüggemann, Engesser, Büchel, Humprecht and Castro2014; Jakubowicz and Sükösd, Reference Jakubowicz and Sükösd2008; Voltmer, Reference Voltmer2013; see also the collection edited by Hallin and Mancini, [Reference Hallin and Mancini2012]). Few analyses, however, have examined and compared variations within national media systems or examined the possible existence of media subsystems. Chakravartty and Roy (Reference Chakravartty and Roy2013), for instance, explore the variety of media systems within the Indian federation, while Gómez (Reference Gómez2016: 2,814) puts forward the idea that “the Latino media is a subsystem of the U.S. media system.” Studies on media regionalism and small media systems also shed light on the characteristics of media subsystems (see, for example, Puppis, Reference Puppis2009).

In their book, H&M do not use the concept of media subsystems, which appeared in the literature thereafter. However, they clearly hint at this possibility a number of times when discussing the distinctiveness of the media environments of Quebec in Canada, Catalonia in Spain, and Northern and Southern Italy (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 71). Hence, in launching this discussion, H&M grasped the relevance of examining the possible existence of media subsystems, given the diverse historical, cultural and political heritage of several countries—a neglected topic in the literature.

Media systems are shaped in part by the journalistic cultures that evolve within them, especially in multicultural states. Over the years, comparative analyses of journalistic cultures at the subnational level have “found their niche” (Hanitzsch, Reference Hanitzsch, Wahl-Jorgensen and Hanitzsch2009: 416). In Canada, research exploring cultural differences in the practice of journalism between francophone Quebec and other predominantly anglophone provinces dates back to the 1960s (Gagnon, Reference Gagnon1981; Desbarats, Reference Desbarats1990; Hazel, Reference Hazel2001). Such differences were attributed to the distinction between an opinion-based, politically infused French journalistic tradition and a facts-based Anglo-American journalism, as conceptualized by Chalaby (Reference Chalaby1996) and others (for example, Benson, Reference Benson2002). These differences, especially between U.S. and French journalism, continue to be explored in the work of Benson (Reference Benson2013) on immigration news, Powers and Vera Zambrano (Reference Powers and Vera Zambrano2016) on online news startups, and Christin (Reference Christin2018) on audience metrics. Similarly, Canadian authors such as Gagnon (Reference Gagnon1981) and Siegel (Reference Siegel1996) have long argued about the historical, linguistic and intellectual influences of Anglo-American and French journalistic traditions on anglophone and francophone journalism in Canada.

Yet an important study by Pritchard and Sauvageau in 1999 challenged the idea of an anglophone-francophone cultural and linguistic divide between Canadian journalists. Based on a national survey, Pritchard and Sauvageau (Reference Pritchard and Sauvageau1999: 34–37, 90–95) showed that francophone and anglophone journalists in Canada shared a common set of convictions, a “Canadian journalist's creed.” Subsequent research provided more nuance for this finding, however. In a panel study of 205 journalists that participated in the original survey, Pritchard et al. (Reference Pritchard, Brewer and Sauvageau2005: 289, 300) found increasing variation between the views of anglophone and francophone journalists about core aspects of the Canadian journalist's creed, thus suggesting “the possibility of an emerging cultural divide” between the two groups. Other studies revealed differences between the coverage of French-language media in Quebec and English-language media in other provinces on issues such as climate change (Young and Dugas, Reference Young and Dugas2012) and Supreme Court rulings (Sauvageau et al., Reference Sauvageau, Schneiderman and Taras2006). Robinson (Reference Robinson1998), in her study of the 1980 Quebec referendum, showed how such differences in coverage could also be exhibited by francophone and anglophone media within Quebec during a period known for its political polarization.

As they assess the degree of professionalization and parallels between the political and media systems (which they labelled “political parallelism”) in Canada, H&M hypothesize that Quebec might feature a distinct media subsystem. The concept of professionalization is an encompassing one, and in discussing it, H&M emphasize the notion of journalistic professionalism. They argue that journalistic autonomy—the journalists’ ability to control the production of information within media outlets according to established principles such as impartiality, balanced coverage and journalistic independence from all forms of pressure—is a “central part” of journalistic professionalism (Hallin and Mancini, Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 34–37). They also suggest that the development of “distinct professional norms” and an “ethic of public service” are other important dimensions of journalistic professionalism (34–37).

Over the past few decades, several authors have highlighted the distinctiveness of Quebec's media environment, given the history of labour union activism among Quebec's journalists (Desbarats, Reference Desbarats1990; Saint-Jean, Reference Saint-Jean and J1998; Demers and Le Cam, Reference Demers and Le Cam2006). H&M also stress this point. Recalling Quebec's “unusual history of militant contestation by journalists over newsroom power,” H&M (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 224) contend that journalists’ autonomy is stronger in Quebec than elsewhere in Canada, as most journalists in major news organizations are unionized and have a record of militancy about negotiating “professional clauses” to shield their independence. They further note the existence of a stronger press council in Quebec than in other Canadian provinces. For H&M (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 37), such self-regulatory mechanisms are clear “manifestations of the development an ethic of public service.” With these features of journalistic professionalism in mind, we propose our first hypothesis:

H1: Journalistic professionalism is stronger in Quebec than in other Canadian provinces.

With respect to the concept of political parallelism, H&M refer to “the degree to which the structure of the media system” reflects the tendencies that characterize the partisan system (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 27). More specifically, they explain that political parallelism refers to the “organizational connections between media and political parties,” the “partisanship of media audiences,” the political involvement of media personnel and the differences in journalistic cultures (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 28–29). On the basis of a number of publications (Gagnon, Reference Gagnon1981; Saint-Jean, Reference Saint-Jean and J1998; Hazel, Reference Hazel2001), H&M (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 209) qualify francophone journalism in Quebec—with its opinionated style and a history of journalists’ involvement in politics (for example, René Lévesque, Jeanne Sauvé, Gérard Deltell, Paule Robitaille, etc.)—as “somewhat different” than anglophone journalism in North America. The recent brief political career of media mogul Pierre-Karl Péladeau with the Parti Québécois may also fuel this interpretation. Hence our second hypothesis:

H2: The politicization of journalism and the news media is stronger in Quebec than in other Canadian provinces.

At first glance, these hypotheses may seem contradictory. In Liberal media systems, strong professionalization is typically associated with weak politicization. However, H&M (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 180, 192) argue that media systems of central and northern European countries associated with the Democratic Corporatist model, although characterized by strong journalistic professionalism (including robust self-regulatory mechanisms and strong unions), are also coloured by greater proximity between political and journalistic circles and more advocacy in the way journalism is practised. Hence, the possibility that the Quebec media subsystem, if it indeed exists, departs from the Liberal model.

We should stress that H&M's typology, in addition to weighing political parallelism and professionalization in distinguishing media systems, also takes into account other elements, such as media markets and the role of the state (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 21–45). We focus on professionalization and politicization, however, because H&M emphasize these elements when suggesting that Quebec might be a distinct media subsystem. That said, H&M's assessment of regional differences within the Canadian media system is peripheral. The goal of these authors was to draw a much broader comparative view of the relationships between media and political systems in the Western world. Given that the authors of this seminal work could not elaborate on their assertions about Quebec, and the general lack of knowledge regarding the existence of media subsystems in multicultural states like Canada, this study is an opportunity to test H&M's claims.

Methodology

We use original data from the Canadian Media System Survey, an expert survey conducted in 2018,Footnote 2 which is inspired by the European Media Systems Survey (Popescu et al., Reference Popescu2011). This methodology offers valid and reliable evaluations from experts, mostly academics, regarding the degrees of journalistic professionalism and parallelism between politics and the media in Canada. As Hooghe et al. (Reference Hooghe, Bakker, Brigevich, De Vries, Edwards, Marks, Rovny, Steenbergen and Vachudova2010: 689) summarize: “[w]hen the object of inquiry is complex, it makes sense to rely on the evaluations of experts—that is, individuals who can access and process diverse sources of information.”

This approach is already used in the study of a number of political phenomena. Among international organizations, Transparency International (2019) and the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (Skaaning, Reference Skaaning2017) rely on experts’ perceptions to assess public sector corruption and the state of democracy, respectively, in a wide range of countries. Political scientists have also used expert surveys to evaluate the influence of prime ministers on their government's policies (O'Malley, Reference O'Malley2007), the tone of electoral campaigns (Gélineau and Blais, Reference Gélineau, Blais, Nai and S2015) and, mostly, the ideological or issue positions of political parties (Benoit and Laver, Reference Benoit and Laver2006; Huber and Inglehart, Reference Huber and Inglehart1995).

To conduct this study, we compiled a database of journalism educators, as well as professors of communication and political science employed by Canadian universities, colleges and (in Quebec) CÉGEPs whose expertise relates to the news media. We sent an invitation to 476 experts and received 192 completed questionnaires, achieving a response rate of 40.3 per cent.Footnote 3 Partially completed surveys from 17 additional experts were included for a total of 209 participants.

Our survey includes general questions about the practice of journalism and the state of news media in Canada, as well as a series of questions about media outlets specific to respondents’ local market. Questions were designed to assess the level of professionalization and politicization in the Canadian media system. In each province, we surveyed the experts according to a list of the most politically significant media outlets. Each list combined major national and provincial television networks, daily newspapers with the largest readership in each province and the most popular private talk radio stations. Weighing the political significance of each media outlet led to the exclusion of some outlets whose journalistic activities and contribution to the structure of political debates are, arguably, limited (for example, most free newspapers that typically reproduce content from press agencies). We asked colleagues familiar with media outlets in different provinces to validate our lists. In order not to overburden respondents, a maximum of 10 media outlets were included in each version of the questionnaire (see online Appendix A). Due to space constraints, results displayed in this article focus on comparisons between Quebec and other provinces, in order to assess the hypotheses of a specific media subsystem, with more descriptive analyses presented in online Appendix B.

The State of Professionalization in the Canadian Media System

We asked experts to evaluate the level of professionalization in the Canadian media system through a series of statements about the state of journalism in Canada. To test our first hypothesis, we examine whether journalistic professionalism is perceived to be stronger in Quebec than in other Canadian provinces.

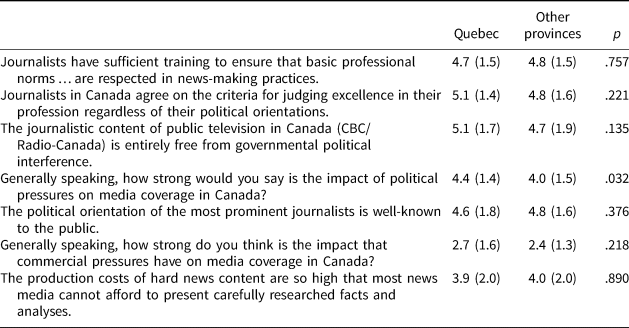

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for seven statements along with tests of mean differences between experts’ perceptions of the state of journalism in Quebec and other provinces. Experts were asked to indicate on a 7-point scale the extent to which they believe the statements listed in the table are true or untrue, or how strong the political or commercial pressures are on journalists. Because some statements were worded in opposite directions, we adjusted the coding such that the highest scores in Table 1 indicate stronger independence.

Table 1 Mean Differences on Professionalization Items

Notes: Values in cells are mean scores (with standard deviations in parentheses) on scales from 1 to 7; p values are from t tests for independent samples. Questions 4 and 6 are drawn from Pfetsch et al. (Reference Pfetsch, Mayerhöffer, Moring and Pfetsch2014).

Generally speaking, experts think that Canadian journalists have strong professional ethics. On a 1–7 scale, the highest mean score (4.93) is related to the statement that “journalists in Canada agree on the criteria for judging excellence in their profession regardless of their political orientations.” Similarly, journalists are perceived as “hav[ing] sufficient training to ensure that basic professional norms like accuracy, relevance, completeness, balance, timeliness, double-checking and source confidentiality are respected in news-making practices” (4.75). Experts tend to agree that journalists do not typically make their political orientation known (4.74), while also believing the “journalistic content of public television in Canada (CBC/Radio-Canada) is entirely free from governmental political interference” (4.85).

Experts are less confident that journalists can operate independent of economic constraints. For example, when asked whether the “production costs of hard news content are so high that most news media cannot afford to present carefully researched facts and analyses,” the average score is at the centre of the scale (3.95), and the standard deviation (2.01) is the largest among those observed in Table 1. Experts also generally perceive media coverage as being influenced by commercial pressures (2.47). These results corroborate H&M's suggestion that in Liberal systems, “[j]ournalistic autonomy is more likely to be limited by commercial pressures than by political instrumentalization” (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004: 75).

As shown in Table 1, the mean values are higher among Quebec experts for four of the seven statements. However, the difference is statistically significant (p < .05) for only one item: the impact of political pressures on media coverage. Because we inverted the coding in such a way that highest scores mean stronger professionalism, values indicate that experts from Quebec perceive the impact of political pressures to be slightly lower (4.4) than experts from other provinces (4.0). Overall, mean differences in Table 1 are too small to accept any hypothesis about a regional media subsystem.Footnote 4

Another way to assess the professionalism of Canadian journalists is to examine the influence of media ownership. We asked participants “How much is the political coverage of each of the following media outlets influenced by its owners?” For media with content on multiple platforms (for example, print, radio, television, websites and mobile apps), experts were instructed not to distinguish between platforms. Participants were also asked to “think about the general content of these media outlets; that is, their news coverage, but also their editorials, columns, blogs and other opinion pieces, if that applies.” Figure B1 (in online Appendix B) plots the mean and standard deviation of experts’ assessments of owners’ influence on political coverage for each media outlet on a scale from 1 (“not at all influenced”) to 7 (“strongly influenced”). CBC/Radio-Canada, whose perceived autonomy from governmental political interference was asked in a previous question, is not included.

Generally speaking, experts believe that owners of private media outlets have a strong influence over political coverage. With a median value of 4.9, this distribution indicates that about 50 per cent of media outlets surveyed received a mean score of 5 points or more on this 1–7 scale. Only one-quarter of media outlets assessed by experts in the survey received an average score below the scale's midpoint (first quartile = 4.05). The Toronto Sun (6.13), the English-language radio station CJAD in Montreal (6.00), the Calgary Sun/Edmonton Sun (6.00) and the Brunswick News newspapers Times & Transcript, Telegraph Journal and the Daily Gleaner (5.92) are perceived as being most influenced by their owners. On the other hand, three of the four news media whose political coverage is perceived as the least influenced by their owners are in Nova Scotia: allNovaScotia.com website (3.50), CJNI-FM (News 95.7) (3.33), and the Metro Halifax Footnote 5 (2.50). In Quebec, the independent newspaper Le Devoir (3.00) belongs to the group of media outlets perceived as least influenced by their owners.

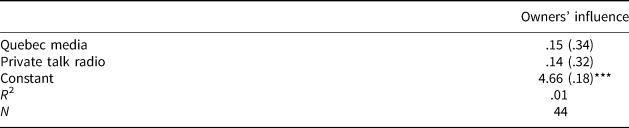

To further test hypothesis 1, we compare experts’ average assessment of owners’ influence over political coverage in Quebec to that of other provinces in a multiple linear regression, which controls for the impact of private talk radio stations. This type of media is sometimes known for its political and provocative broadcasts, as evidenced by studies of various radio stations and programs across the country (see, for example, Saurette and Gunster, Reference Saurette and Gunster2011; Vincent et al., Reference Vincent, Turbide and Laforest2008). One could argue that this genre of talk radio may encourage the perception that media content is more likely to be influenced by owners’ political preferences—hence the need to control for this type of media. Moreover, because our dataset includes more talk radio stations in the questionnaires distributed in Quebec, this variable must be controlled.

Table 2 presents the results from an ordinary least square (OLS) regression. This multiple linear regression shows that political coverage among Quebec-based news media is perceived as no more influenced by its owners than in other provinces. Similarly, private talk radio stations are not perceived to be more or less affected by their owners’ preferences than are other types of news media.

Table 2 Perceptions of Owners’ Influence on Political Coverage

*** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05 † p < .10

Notes: Values in cells are OLS regression coefficients; standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is the mean value on a 1–7 scale from “not influenced at all” to “strongly influenced.”

The robustness of this analysis is tested with four additional multiple linear regressions presented in online Appendix C. First, we replaced the dependent variable by the median (rather than the mean) value of the perceived impact of owners on political coverage in Table C1.1 (see Lindstädt et al., Reference Lindstädt, Proksch and Slapin2018). Second, we also ran the model presented in Table 2 without five media outlets for which we had fewer than five experts (mostly in Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia) (Table C1.2). Third, we ran the model with the mean values computed without the experts who indicated never getting news and information about Canadian politics from the corresponding media outlet (Table C1.3). Fourth, we recoded the “Quebec media” variable to keep only French-language media outlets in the “Quebec” category (coded 1), the English-language Quebec media, the Montreal Gazette and CJAD, being coded 0, along with other Canadian media (Table C1.4). There is no significant difference between these supplemental analyses and the one presented in Table 2. Clearly, hypothesis 1 is not supported: experts’ perceptions of the degree of professionalization do not differ substantively between media in Quebec and the rest of Canada.

The Politicization of the Canadian Media System

Hypothesis 2 states that politicization of journalism and news media is stronger in Quebec than in other Canadian provinces. We test this hypothesis with indicators relating to the perceptions of ideological orientation and partisanship of the content provided by Canadian news media.

The ideological orientation of the media

Experts were invited to assess whether they believe national and local media outlets exhibit political preferences on specific issues. Using a 7-point ideological scale ranging from left to right—with the centre of the scale meaning that the media coverage is balanced or neutral—and including a “don't know” option, we asked the experts to qualify the political leanings of national and local media coverage based on four statements reflecting economic issues, social issues, the accommodation of religious minorities, and issues concerning Quebec. We instructed respondents to think about the general content of these media on their different platforms, if applicable. Complete question wording is available online in Appendix A.

As shown in figures B2.1 to B2.4, in online Appendix B, experts perceive ideological diversity in the Canadian media landscape, although some specific patterns emerge. Concerning the media's coverage of economic issues, experts place most news media on the right side of the ideological spectrum, with a few exceptions. On social issues, experts also position most news media surveyed on the right of the ideological scale, but closer to the centre, with several outlets on the left. For example, the Tyee in British Columbia, the Telegram in Newfoundland and Labrador, the Toronto Star and Le Devoir are perceived as the most left-leaning outlets in Canada, with respect to their coverage of both economic and social issues. The two public broadcasters, CBC and Radio-Canada, are also positioned on the left but closer to the centre. Quebec City private talk radio stations (CHOI Radio X, FM 93) and the Toronto Sun are viewed as the most right-leaning outlets.

The Canadian news media is considered more divided on issues relating to religious diversity and accommodation, having a median score equal to the centre of the scale and the largest interquartile range of the four issue domains. CHOI Radio X, FM 93, Le Journal de Montréal/de Québec and the Toronto Sun are considered as having the least favourable coverage of religious accommodation, whereas the Tyee, the Toronto Star, the Independent in Newfoundland and Labrador, and the CBC are seen to have the most favourable coverage. This is the only issue where one of the two public broadcaster networks (CBC/Radio-Canada) is not within one standard deviation from the midpoint of the scale (explicitly labelled as “balanced” in the survey).

Naturally, Quebec media are viewed as offering the most favourable coverage of Quebec, whereas private talk radio stations in British Columbia (980 CKNW), Alberta (News Talk 770 / 630 CHED) and Saskatchewan (650 CKOM / 980 CJME), as well as the Winnipeg Sun, Toronto Sun and National Post, were perceived as offering the least favourable coverage of the province.

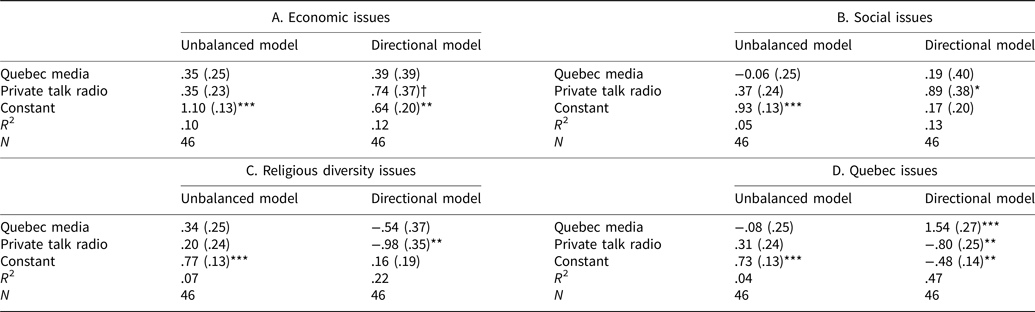

To test the second hypothesis, we conducted eight multiple linear regressions assessing whether Quebec media's mean scores on each of the above issue areas are different from other provinces. For aforementioned reasons, we again controlled for private talk radio stations. For each issue area, Table 3 presents two models. The first model aims to determine whether Quebec-based media outlets are less balanced than other news media. In this unbalanced model, the dependent variable is the absolute difference between the midpoint of the scale (4) and the observed mean value. For example, mean scores of 3 and 5 would both have a value of 1 point—that is, the absolute distance from the centre of the scale. In this model, the dependent variable ranges from 0 to 3 points. The second model tests whether Quebec media lean more toward one side than do news media from other provinces. In this directional model, the dependent variable is the difference between the midpoint of the 1–7 scale and the observed mean value, thus ranging from −3 to 3.

Table 3 Perceptions of Ideological Leanings in Media Content

*** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05 † p < .10

Notes: Values in cells are OLS regression coefficients; standard errors in parentheses. In unbalanced models, the dependent variable is the absolute difference of values between the balanced point and the observed mean, ranging from 0 to 3 points. In the directional models, the dependent variable is the difference of values between the balanced point and the observed mean, ranging from −3 to 3 points: that is, from left to right (economic and social issues), or from less favourable to more favourable (religious diversity and Quebec issues).

The first interesting finding related to the unbalanced model is that all four constant terms significantly differ from 0, which suggest that Canadian news media (excluding those in Quebec and private talk radio stations), on average, do not present a balanced coverage of these issues. That said, the data do not support the hypothesis of a distinct media subsystem in Quebec. News media from Quebec are no more unbalanced than are media from other provinces regarding the coverage of economic, social, religious diversity and Quebec issues. The same conclusion applies to private talk radio stations.

There is more to say about the directional model, however, especially regarding private talk radio stations, which are perceived by experts as being significantly more conservative on economic and social issues and less favourable toward accommodating both religious minorities and Quebec. These coefficients show that private talk radio stations are significantly more oriented than other news media. They lean even further to the right on economic issues and are even less favourable to Quebec than other news media. Concerning social issues, experts place talk radio stations clearly on the right side of the spectrum, while the other types of outlets are nearer the centre. Similarly, while other news media score closer to the centre of the scale with respect to religious diversity, talk radio stations are seen as much less favourable to it.

Compared to news media from other provinces, Quebec-based media are rated on average about one-and-a-half points (1.54) more favourable in their coverage of Quebec on the 1–7 scale. This model has the highest proportion of explained variance (R 2 = .47). On economic and social issues, Quebec-based media outlets have positive regression coefficients (indicating their coverage leans to the right side of the ideological spectrum), but they are not statistically significant. On the issue of religious diversity, the coefficient for Quebec media is negative (less favourable toward accommodation for religious minorities), but again, it is not statistically significant.

As for the analysis of experts’ judgment on the impact of ownership, the robustness of these analyses has been tested. Online Appendix C presents the results of alternative models using median values (Table C2.1), without the media outlets whose ideological orientation is assessed by fewer than five experts (Table C2.2), without the experts who reported not getting news and information about Canadian politics from a given news media (Table C2.3) and with French-language media outlets only in the “Quebec” category (Table C2.4). In most cases, the direction and statistical significance of the coefficients for Quebec media remain unchanged. However, when we code only French-language media outlets in the “Quebec” category, coefficients related to religious diversity issues become significant: these media are perceived as more oriented and more opposed to religious accommodations. Also, in tables C2.1 and C2.3, the unbalanced models show that private talk radio stations are more oriented than other media (p < .10). So far, the evidence does not support hypothesis 2.

Media partisanship

To assess perceptions regarding media partisanship, we asked experts to characterize the “political colour” of national and local media outlets. For each media outlet, respondents could select which federal and provincial political party its coverage tends to agree with most often. Each scrollable list of answers also included the options “None” and “I don't know” (see online Appendix A for exact wording). We use answers to these questions to analyze media partisanship through a two-stage process.

In the first stage, we examine the percentage of respondents identifying a federal party rather than the “None” option (Figure B3.1 in online Appendix B). Among the 46 media outlets assessed in the survey, the mean proportion is 65.7 per cent and the median value is 75.4 per cent. On average, two-thirds of experts associated media outlets with one of the federal parties, and half of the media outlets assessed in the survey were perceived as having a federal partisan leaning by at least three-quarters of experts in the sample.

In the second stage, we took into consideration the variation in the number of experts who selected a political party from the list of those represented in the federal legislature at the time of the survey. We did so by calculating, for each media outlet, the value of the index of qualitative variation (IQV), a comprehensive measure of dispersion for nominal variables, whose values range from 0 to 1, where 0 means no diversity (all judgments concentrated into one category) and 1 means a maximum variation (an equal number of responses in all categories) (Frankfort-Nachmias and Leon-Guerrero, Reference Frankfort-Nachmias and Leon-Guerrero2014: 138–43). The IQV was computed following equation 1:

where K is the number of categories (that is, political parties with members in the legislature) and ∑Pct2 is the sum of the squared percentages of experts for each party (among those who selected a political party, excluding those who chose the option that a given media agrees with no party in particular). The lower the IQV, the higher the perception of partisanship among experts who indicated the media outlet agrees in most cases with one specific political party. In contrast, the higher the IQV, the weaker the consensus among experts regarding the party a particular media outlet agrees with most often.

The combination of the percentage of respondents who indicated that a media outlet agrees with any party and the IQV allows us to calculate, for each media, an index of partisanship with equation 2:

We then summarized the information into a partisanship index ranging from 0 to 1, where 0 means no perceived partisanship and 1 means strong perceived partisanship. Figure B3.2 in online Appendix B plots the value of this partisanship index for each media outlet, regarding federal parties. Overall, there is a good range of variation among these 46 media outlets: the mean value of the partisanship index is .48, the first quartile is .24, the median is .43 and the third quartile is .75.

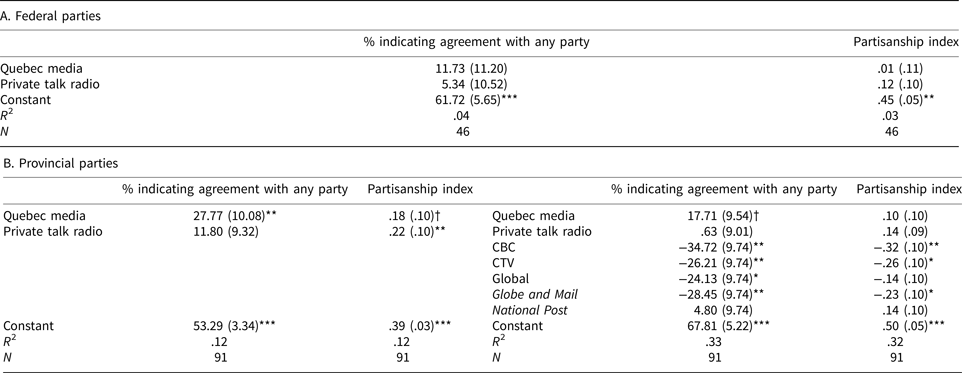

As before, we tested hypothesis 2 using OLS regressions where the media outlet is the unit of analysis, and scores on the variables are aggregated across experts. Table 4 presents the findings with two basic models: in the first model, the dependent variable is the percentage of experts indicating that a given media agrees with any political party. In the second model, the outcome is the partisanship index. Panel A of the table presents the regression results regarding federal parties. Quebec-based media have positive coefficients in both models, but they are not statistically significant. The same conclusion applies for private talk radio stations, which do not appear to be more partisan than other media outlets. Alternative models restricted to news media judged by at least five experts (Table C3.1) or based on judgments from experts who reported getting some of their political news from them (Table C3.2) or French-language media outlets in Quebec (Table C3.3) confirm these findings.

Table 4 Perceptions of Media Partisanship

*** p < .001 ** p < .01 * p < .05 † p < .10

These models also allow us to assess media partisanship at the provincial level. However, some adjustments are required for national news media whose provincial partisanship is assessed in multiple provinces (CBC, CTV, Global, the Globe and Mail and the National Post). So as not to merge all answers collected across the country into a single variable per outlet, we created 10 provincial variables for each of these networks, thus increasing the number of observations from 46 to 91. Panel B of Table 4 presents these multiple linear regressions, with and without dummies for these national networks.

The percentage of experts who perceive outlets as agreeing more often with one of the provincial parties is higher among Quebec-based media. With controls for private talk radio and the national networks, the percentage is 17.7 points higher for Quebec media (p < .10). The partisanship index also appears statistically higher for Quebec media (p < .10) without the network dummies, but this relationship is no longer significant in the full model. Also, these rare statistically significant coefficients for Quebec media do not withstand the robustness tests presented in online Appendix C (Tables C3.1, C3.2 and C3.3). Overall, the evidence once again does not suggest meaningful differences in politicization between media outlets in Quebec and the rest of the country. Thus, hypothesis 2 is not supported.

Discussion and Conclusion

In their seminal work, H&M (Reference Hallin and Mancini2004) acknowledge the heterogeneous nature of several countries’ media systems and the possibility of subnational media systems. Speaking to the uniqueness of Quebec's media environment, the authors suggest that it may be more professional and politicized than that of other Canadian provinces. Hence the question: Does Quebec constitute a distinct media subsystem? Data from the inaugural Canadian Media System Survey do not support this thesis. There is scant evidence of regional variations across provinces with respect to the level of professionalization and politicization within the Canadian media system. That said, the data reveal a variety of ideological and political preferences displayed by Canadian news media organizations.

These findings have empirical and theoretical implications for the study of political communication in Canada. The literature on media ownership and convergence (for example, Soderlund et al., Reference Soderlund, Brin, Miljan and Hildebrandt2012) aside, content analyses of political news are more commonly designed to select a few national news media as “representatives” of the whole media landscape (Bastien, Reference Bastien and Gingras2018). Hence, increased attention could be dedicated to understanding differences between media outlets across provincial media markets in a more systematic way.

Political scientists who examine the relationship between exposure to news media, public opinion and political behaviour rarely design surveys that allow for distinctions between news media organizations. The Canadian Election Study, for example, typically distinguishes between media platforms (radio, television, newspapers, internet) instead of media outlets. The development of measures specifically targeting media organizations is thus critical to furthering our understanding of these phenomena.

On the theoretical side, our findings add to Soroka's claim about a single newspaper agenda in Canada. In his study on agenda-setting dynamics, Soroka (Reference Soroka2002) argues that beyond Quebec-specific issues (for example, national unity), there is strong inter-newspaper consistency, with very limited regional variation, especially when the saliency of an issue is high. With a dataset of election stories published in newspapers outside Quebec during the 2006 federal campaign, Gidengil (Reference Gidengil, Marland, Giasson and A2014) conducted a comparative analysis of newspaper coverage and reached the same conclusion. Our study lends further support to these claims, showing that experts’ perceptions of media coverage of economic, social and some cultural issues are largely similar in Quebec and other regions of the country.

However, when we examine the political and ideological orientations of news coverage for such issues, organizational differences appear. Experts place news media on a rather broad spectrum when evaluating the ideological and partisan positions of Canadian news organizations. In some cases, such preferences may not even be clear at first sight. For example, while a majority of the experts did not associate CBC/Radio-Canada with a federal party, almost all of the experts who did make this political connection associated the public broadcasters with the Liberal Party of Canada.

One must consider the critical ramifications of this perceived politicization of the Canadian news media. On the one hand, the survey data suggest that Canadian journalists are viewed as fulfilling a monitorial role, as conceptualized by Christians et al. (Reference Christians, Glasser, McQuail, Nordenstreng and White2009: 139–50), by having strong professional ethics and adequate training to ensure balanced and accurate reporting, “analysis and interpretation of events” for public benefit. On the other hand, the perceived ideological orientation and partisanship of Canadian news organizations call into question this monitorial perspective, which, as Rollwagen et al. (Reference Rollwagen, Shapiro, Bonin-Labelle, Fitzgerald and Tremblay2019) show, still very much defines the Canadian journalistic creed. Such conflicting views may signal increasing skepticism toward the Canadian media's capacity to act as impartial mediators of society's democratic debates, given their perceived ideological leanings. Canadian journalists must weigh these considerations against their capacity to perform their role as detached observers.

Our findings also challenge H&M's convergence thesis toward the Liberal model by exposing the coexistence of commercialization and politicization forces in the Canadian media system. This research echoes, in this regard, Nechushtai's (Reference Nechushtai2018) study of the U.S. news system, which she argues displays the characteristics of the Liberal and the Polarized Pluralist models, the latter known for its politicized nature. Nechushtai (Reference Nechushtai2018: 184, 194) suggests, in particular, that if there is convergence, it “will be toward a mixed model”—one, among other things, “that is both market based and ideology driven.” This hypothesis merits further consideration, as our findings suggest.

Our expert survey is not without limitations. The necessity of relying on a limited number of experts of news media in some areas of the country has affected our ability to study smaller provinces, as well as the news media serving linguistic minorities outside Quebec, ethnic communities and First Nations. Our concern not to overburden respondents also limited our ability to make relevant distinctions. For instance, some francophone respondents from New Brunswick commented that we should have listed Radio-Canada (instead of CBC) for the questionnaire in French for their province. This is a distinction that can be better served by future research. Furthermore, this survey methodology does not ensure that perceptions of experts in each geographical unit are perfectly comparable: coverage could be perceived as biased in one area of the country but not biased in another. In the same vein, experts in our sample are not free of ideological and political biases that may inherently colour their own judgments of media coverage. Examining expert ratings of political party positions, Curini (Reference Curini2010) reports some evidence of ideological bias among experts, with errors in estimation principally attributed to right-leaning political parties. In short, survey methods cannot do justice to all the nuances and complexities of media systems. More research drawing on a variety of methodologies—including content analyses, interviews, and surveys of journalists, as in Rollwagen et al. (Reference Rollwagen, Shapiro, Bonin-Labelle, Fitzgerald and Tremblay2019)—will continue to shed light on the characteristics of the Canadian media system.

With these limitations in mind, this expert survey provides a unique opportunity to investigate within-country variation of the partisan orientations of news media from a comparative perspective. By relying on experts’ assessments of both national and provincial media outlets, our survey methodology also allows us to examine the Canadian media system more broadly. Because we replicated the methodology and many questions from the European Media Systems Survey, we could, furthermore, compare the Canadian media system with European ones and assess to what extent it is as Liberal as H&M claim it is. Finally, our survey may serve as a starting point from which future researchers may analyze the dynamics of Canada's media landscape, thus providing scholars one more tool to examine, over time, the state of the news media in Canada at the national, regional and organizational level.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008423920000189

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful suggestions and Alisson Lévesque for her research assistance. This research is supported by an SSHRC Insight Development Grant. Principal Investigator: Simon Thibault (Université de Montréal).