I

We are at present in a moment of geopolitical transition that has some fascinating parallels with the world of a century ago. Then the most mature economy was Great Britain, but it was growing more slowly than the larger challengers: the US, and in Europe the heavily export-oriented German Empire (Buchheim Reference Buchheim1984).

The financial operations of the world in the early 1900s nevertheless were concentrated in Britain, and specifically in the City of London, the dominance of which Youssef Cassis has extensively explored (Cassis Reference Cassis1994, Reference Cassis2012). Since exporters could not have financial agents in every city that imported from them, the trading finance of the world was run through London merchant banks. If a Hamburg or New York merchant wanted to buy coffee from Brazil, they would sign a commitment (a bill) to pay in three months’ time on arrival in their port; it might be drawn on a local bank, or it could be turned into cash by the exporter (discounted) at a London bank.

Walter Bagehot's classic and still influential study of finance Lombard Street (Reference Bagehot1873) consequently described the City of London as ‘the greatest combination of economical power and economical delicacy that the world has ever seen’ (p. 4). He presented the development as a very recent phenomenon, deriving from the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War.

Concentration of money in banks, though not the sole cause, is the principal cause which has made the Money Market of England so exceedingly rich, so much beyond that of other countries . . . Not only does this unconscious ‘organisation of capital’, to use a continental phrase, make the English specially quick in comparison with their neighbours on the continent at seizing on novel mercantile opportunities, but it makes them likely also to retain any trade on which they have once regularly fastened. (Bagehot Reference Bagehot1873, pp. 6, 15)

The power was the result of the complexity of the system that assessed risks across the world and allocated financial flows accordingly. Power here can be conceived of as influence through the web of dependent relationships that were created: most notably, other governments needed access to London markets if they were to be able to finance their debt (and hence their capacity for military power projection). But that power was, as Bagehot put it, also vulnerable (‘delicate’) in the sense that it could easily be disrupted by panics in which confidence collapsed. Making power more robust necessarily then involved experimentation with financial innovation.

A physical infrastructure provided the basis for the financial links. The initial contacts between buyer and seller, the bills of exchange, the insurance all depended on the transoceanic cable. The first transatlantic cable had been laid in 1866, and with the increased use of the steamship provided the basis for a gigantic expansion of commerce. At the beginning of the twentieth century, a new innovation, wireless telegraphy, meant that cargoes could be reallocated while they were in transit at sea (Lambert Reference Lambert2012).

In addition, most of the world's marine insurance – even for commerce not undertaken in British ships or to British ports – was underwritten by Lloyds of London. As in the case of trade finance, there were gigantic network effects: a very deep financial market was required in order to be able to absorb potentially large losses. But the network ran together in a single node, with the result that the City of London controlled the world's interactions.

Many features of this world have been reproduced in the modern era of hyper-globalization (Subramanian and Kessler Reference Subramanian and Kessler2013). Like Bagehot's world it is both highly complex and vulnerable to dislocation and interruption. The modern equivalent to the financial and insurance network that underpinned the first era of globalization is the connectivity established through electronic communications. Like the nineteenth-century trading and insurance network, it is in principle open to all on the same terms. But its complex rules are set in a limited number of jurisdictions, to some extent in the EU but mostly in the United States. The data that connect the information economy depend on complex software and interaction systems managed by large and almost exclusively US corporations: Google, Microsoft, Facebook, as well as by (again mostly US) telecom firms (Sprint, Verizon).

The panic of October 1907 showed the fast-growing industrial powers the desirability of mobilizing financial power. It was a crisis which unambiguously originated in the US, where it had been preceded by financial stress in late 1906 and a stock market collapse in March 1907. The October panic affected at first the new trust companies, but the New York banks were forced to restrict convertibility of deposits into currency. The demand for cash produced an interest rate surge that drew in gold imports, but also pushed spikes in interest rates elsewhere, with great bank strains in Italy, Sweden and Egypt, but also in Germany. Only one country seemed quite immune to the panic, even though its market was the central transmission mechanism of price information and interest rate behavior. British observers congratulated themselves on their superiority in a world that was increasingly ‘cosmopolitan’ as a result of the ‘marvellous developments of traffic and telegraphy’, as the Economist put it. ‘We have no reason to be ashamed. The collapse of the American system has put our supremacy into relief . . . London is sensitive but safe.’Footnote 1 More explicitly: ‘Our banking system is so much sounder, and those who control it command and deserve so much more confidence, than is the case in less favored countries.’Footnote 2

Outside the UK, not only in peripheral countries like Egypt or Italy, but especially in the challenger countries, 1907 looked like a credit inflation that threatened momentarily to implode (Taylor Reference Taylor2012). The new credit had been driven by financial innovation: in particular the emergence of the guaranty trust, a sort of investment fund, in the US, and the expansion of activity of the German Great Banks.

How would the US and Germany respond? Financial panics had a significant security dimension. The risks were highlighted in the Second Moroccan Crisis in 1911, when in response to an aggressive German act (the dispatch of a gunboat to Agadir) French holders sold off German assets and provoked a financial panic in Germany in the hope of making German policy-makers reverse course. At the same time, Austria–Hungary, whose businesses hoped for further access to the French capital market, abandoned its German ally and lined up with Paris (Fischer Reference Fischer1969, pp. 133–4). The arguments made by reformers as to why a significant strengthening of the financial system was needed in crisis countries in consequence encompassed political as well as purely economic logic.

II

The 1907 experience convinced some American financiers that New York needed to develop its own commercial trading system that could handle bills in the same way as the London market.Footnote 3 At that time, federal legislation actually prohibited trade acceptances as well as foreign banking activity (Eichengreen and Flandreau Reference Eichengreen and Flandreau2010). There was also a discussion as to whether some institution analogous to the Bank of England was required. The politicians quickly picked up the message that finance could bring power and influence in the world. Notably President Taft and his Secretary of State made ‘substituting dollars for bullets’ the centerpiece of their diplomacy (Taft Reference Taft1912; see also Rosenberg Reference Rosenberg1999).

The central figure on the technical side in pushing for the development of an American acceptance market was Paul Warburg, the immigrant younger brother of a great (and fourth-generation) Hamburg banker Max Warburg, who was the personal adviser of the German autocrat Kaiser Wilhelm II. Paul had started his banking training in the Hamburg bank, then worked in London and Paris before moving back to Hamburg; but then he married Nina Loeb, the daughter of a prominent New York financier, and moved across the Atlantic. But he maintained excellent, cordially intimate relations with his older brother, and a very close commercial relationship: Warburg raised money not only on the German market but throughout continental Europe for the purchase of US (mostly railroad) securities issued by Kuhn Loeb; when the US started to export capital, Warburg in Hamburg sold back US securities onto the American market.

Paul Warburg was a key player in the bankers’ discussions on Jekyll Island and then in drawing up the institutional design of the Federal Reserve System. The two banking brothers Warburg were in fact on both sides of the Atlantic energetically pushing for German–American institutions that would offer an alternative to the British industrial and financial monopoly (see Cassis Reference Cassis2012). They were convinced that Germany and the United States were growing stronger year by year while British power would erode.

Paul Warburg responded immediately to the events of 1906–7. His first contribution had appeared well before the panic of October 1907 demonstrated the terrible vulnerability of New York as a financial center, and was a response to the market weakness of late 1906. That initial contribution, ‘Defects and Needs of Our Banking System’, came out in the New York Times Annual Financial Review on 6 January 1907; its main message was about the need to learn from continental Europe. Warburg started with a complaint:

The United States is in fact at about the same point that had been reached by Europe at the time of the Medicis, and by Asia, in all likelihood, at the time of Hamurabi . . . Our immense National resources have enabled us to live and prosper in spite of our present system, but so long as it is not reformed it will prevent us from ever becoming the financial center of the world. As it is, our wealth makes us an important but dangerous factor in the world's financial community.Footnote 4

The Cassandra warning about the danger posed by the American financial system would make Warburg look like a true prophet after a renewed period of tension after October 1907. The panic, the need for a response coordinated by J. P. Morgan, and the debate about whether Morgan had profited unduly from his role as lender-of-last-resort is one of the most celebrated incidents in US financial history. By 1910, Warburg had firmly established himself as the preeminent banking expert on reform of the monetary system.

The problem of the American system in his eyes was that it relied on single-signature promissory notes: when confidence evaporated in a crisis, the value of these became questionable and banks would refuse to deal with them. Warburg proposed to emulate the trade finance mechanism of the City of London, where the merchant banks (acceptance houses) established a third signature or endorsement on the bill, a guarantee that they would stand behind the payment; the addition of this guarantee provided a basis on which a particular bank favored by a banking privilege conferred by law, the Bank of England, would rediscount the bill, i.e. pay out cash. ‘The authority for the government bank to buy three months' dollar paper, also bearing at least three signatures, including a bank's or banker's indorsement or acceptance, is added for the purpose of encouraging the creation of such paper, the lack of which is largely the cause of the immobilization of the resources of our banks’ (Warburg Reference Warburg1907b, p. 32). The accumulation of a deep and liquid market for three-signature bills would free the US from dependence on clearing house certificates, where the liabilities of the bank members of the clearing house were potentially very large. Clearing house certificates in Warburg's eyes exacerbated the panic, because they were a confirmation of the existence of some doubt or question. The purpose of the emulation of European banking was to avoid the periodic disruption of normal commerce through worries about the financing mechanism.

The second element of the Warburg plan was fundamentally a state bank, an innovation that recalled the early experimentation of Alexander Hamilton but also the controversies about the charter renewals of the First and the Second Bank of the United States. The model for the initial reform proposal was not just the Bank of England system, but that of Imperial Germany, where the Reichsbank existed as a deliberately created analogue to the Bank of England, but with a specific right to issue notes beyond those backed by gold on payment of a charge to the government. The result was that there were no liquidity panics in Germany at all, and Warburg explicitly referred to the German parallel rather than to that of the Bank of England:

The idea that the issuing of clearing-house certificates in itself implies the existence of a crisis would soon disappear, and before long the general public would be as little excited by it as is the German public when the limit of the amount of notes which may be issued without paying a tax has been reached. The issue of clearing-house certificates would mean, in general, that it is time to go slow, but it would not necessarily imply the imminence of a panic. (Warburg Reference Warburg1907b, p. 33)

The adoption of this system would obviate the precarious pyramiding of reserves under the US National Banking system, that so easily and readily reversed itself in a crisis.

The language of Warburg's public appeals made analogies to armies and defense: ‘Under present conditions in the United States … instead of sending an army, we send each soldier to fight alone.’ His proposed reform would ‘create a new and most powerful medium of international exchange – a new defense against gold shipments’ (Warburg Reference Warburg1907a, pp. 9–10). The experience of US financial crises in the past, in 1893 and in 1907, where there was a dependence on gold shipments from Europe, indicated a profound fragility. Building up a domestic pool of credit that could be used as the basis for issuing money was a way of obviating the dependence. The reform project involved the search for a safe asset, not dependent on the vagaries and political interferences of the international gold market.

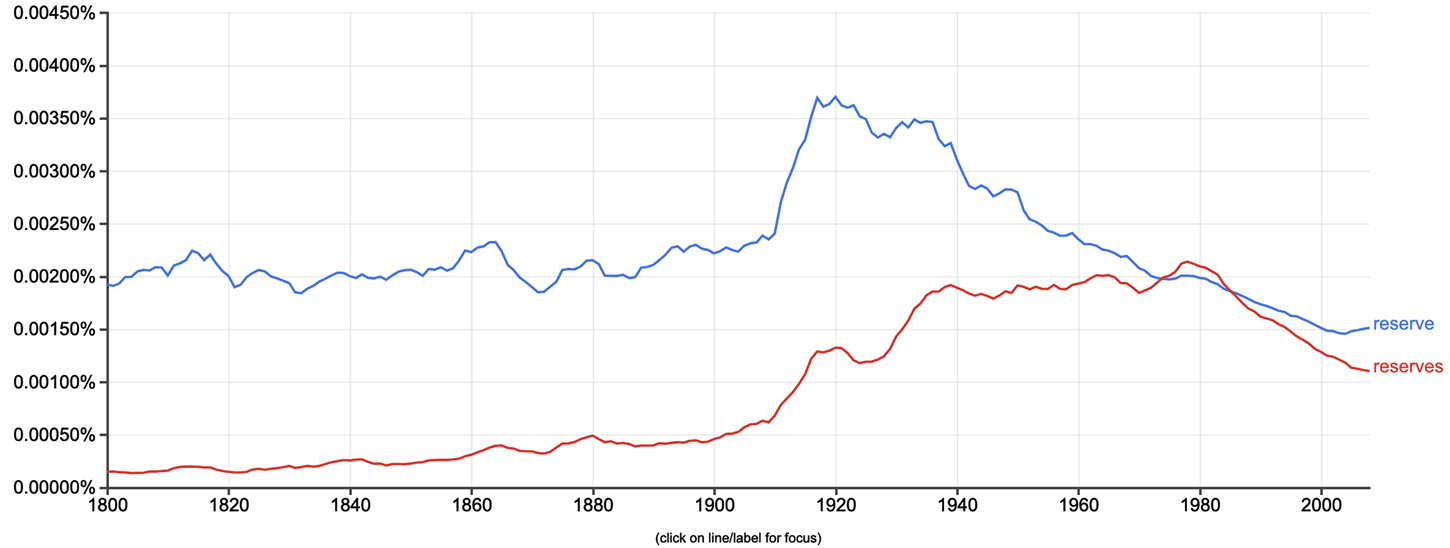

Reserves became a more fashionable concept in the 1900s, as both its narrower financial usage and its general meaning increasingly appeared on the printed page, as captured in the Google N-Gram chart that measures relative frequency of word use (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Google N-Gram viewer: ‘reserve’ and ‘reserves’

Another way Warburg made the point about making the US system more robust and secure was to urge the reduction of the dependence of the New York banks on stock exchange loans (which were obviously prone to valuation changes in the securities posted as collateral), and substitute the much more secure basis of commercial credit. ‘By modernizing the form of our commercial paper and by creating a central bank we should aim to transform our commercial paper from a non-liquid asset into the quickest asset of our banks’ (Warburg Reference Warburg1907b, p. 28).

For the next years, Warburg continued to promote this idea. In particular, he worked with Senator Nelson Aldrich, the chairman of the Senate Finance Minute Committee and the key figure in the National Monetary Commission that examined the lessons to be learnt from the panic of 1907. A key concern of Aldrich was what the US should learn from Europe – and fitted very obviously with Warburg's long-standing passion for this subject (Whitehouse Reference Whitehouse1989). In 1910, Paul Warburg wrote: ‘In Europe an effective discount rate protects the country from foreign and domestic drains alike, while no such protection exists with us’ (Warburg and National Monetary Commission Reference Warburg1910, p. 39). Warburg first proposed in 1910 the creation of a central bank with 20 regional branches controlled by bankers but regulated by government officials. This institution, provisionally named the United Reserve Bank, would rediscount bills of exchange for its member banks, thereby providing liquidity to the market (Bordo and Wheelock Reference Bordo and Wheelock2011).

He also worked on the institutional realization after World War I: in 1919, he founded and then accepted the position of first chairman of the American Acceptance Council. He also organized the International Acceptance Bank of New York in 1921, whose capital was supplied by a wide range of foreign banks, including M. M. Warburg, Hamburg, N. M. Rothschild, Credit Suisse and Swiss Bank Corporation.Footnote 5

Warburg and Aldrich were the central drivers at the secrecy-shrouded Jekyll Island bankers’ meeting of November 1910, which also included Frank Vanderlip, president of National City Bank; Harry P. Davison, a partner of J. P. Morgan; Benjamin Strong, vice president of Banker's Trust Co. which was close to J. P. Morgan, as well as A. Piatt Andrew, the former secretary of the National Monetary Commission and now assistant secretary of the Treasury. This produced the Aldrich Plan for a National Reserve Association which was similar to Warburg's plan but had a more decentralized administrative structure: a National Reserve Association with its headquarters in Washington, but with branches across the country. Transformed by the political situation after the victory of the Democrats and Woodrow Wilson in 1912, the Aldrich bill was modified so as to form the basis of the Federal Reserve System. Warburg engaged in detailed negotiations with Carter Glass, chair of the House Banking Committee, and with Parker Willis, the committee's economist; but also in parallel with the administration through Wilson's confidant Colonel House. Subsequently, he engaged in bitter polemics with Glass when he demonstrated how much Aldrich and how little Glass there was in the actual Federal Reserve Act. Glass had responded to the publication of extracts from Colonel House's papers by minimizing House's role, and trivializing Warburg as a maniacal and earnest foreign bore who only supplied the real makers of the Federal Reserve Act with ‘mental calisthenics’: ‘Mr. Warburg exhibited a sort of religious zeal for the ideas he entertained on the subject of banking and currency reform. Moreover, he presented them with a force of reasoning and an ingenuity of expression that were not exceeded by his earnestness’ (Seymour Reference Seymour1926; Glass Reference Glass1927, pp. 209–11; Warburg Reference Warburg1930).

Warburg was nominated to the Board of the Federal Reserve, and was instantly the subject of a sustained political attack. The main complaint was that he was a representative of Kuhn Loeb and the Money Trust, but the critics also made a great deal out of the German connection. As the New York Times put it:

The opponents of Mr. Warburg also say he is actively connected with the Hamburg banking house of Max Warburg & Co., and that while under the terms of the law the great banking houses of the United States are not supposed to have a direct hand in the direction of the new banking system, the appointment of Mr. Warburg would give one of the powerful banking houses of Europe an unfair advantage.Footnote 6

In these tense debates, Warburg consistently presented the issue in terms of a need to increase American security in the face of substantial vulnerability. As Warburg presented it, the term chosen in the original Aldrich Plan, as well as the eventual name of the new central bank, brought a clear analogy with military or naval reserves.

The word ‘reserve’ has been embodied in all these varying names, and this is significant because the adoption of the principle of co-operative reserves is the characteristic feature of each of these plans. There are all kinds of reserves. There are military and naval reserves. We speak of reserves in dealing with water supply, with food, raw materials, rolling stock, electric power, and what not. In each case its meaning depends upon the requirements of the organization maintaining the reserve. (Warburg Reference Warburg1916)

He also consistently reverted to his original theme that had first been sounded in the early months of 1907: ‘The stronger the Federal Reserve Banks become, the stronger will be the country and the greater its chances to fulfill with safety and efficiency the functions of a world banker. The basis of this development must be confidence’ (Warburg Reference Warburg1915).

III

Germans felt initially much more self-confident about the virtues and the resilience of their financial system than did the US financial community. Jacob Riesser of the Darmstädter Bank, the elder statesman of German banking, for instance, enjoyed citing the New York Bankers’ Magazine, which had claimed that ‘German banking policy differs essentially from all others in giving full expression to the national genius.’Footnote 7 That was 1905 – but then the turmoil of 1907 prompted a reassessment.

In Germany in 1907 Paul Warburg's older brother Max was pushing a similar lesson to that drawn by Paul, but in a rather different way. He became consistently engaged in efforts to strengthen German–American cooperation, as a sort of balance against the threats posed by British power. From 1906 he became the central figure involved in the financing of the Hamburg–America Line syndicate (later HAPAG); within the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce he became a fervent supporter of colonial projects, a Colonial Institute, an Institute of Tropical Hygiene etc. The dominant figure in HAPAG was Albert Ballin, also from Hamburg, who although a tremendous Anglophile, saw himself in continual competition with Britain and with British power (Gerhardt Reference Gerhardt2010). Warburg was responsible for bringing Ballin together with Edward VII's friend Sir Ernest Cassel, a German-born banker who tried hard to stop the deterioration of Anglo-German relations.Footnote 8 But his greatest success was bringing the governments in Berlin and Washington closer together in a cooperative financing venture for Chinese railroad construction.Footnote 9 Working closely together with the United States seemed to Warburg like an act of balancing in the face of a destabilizing and preponderant British power.

In September 1907, when the American crisis was brewing, but had not morphed into a full-fledged panic, Max Warburg galvanized the German Bankers’ Association conference in Hamburg with a speech on ‘Financial Preparedness for War’ that he delivered on the invitation of Jacob Riesser. The brothers Warburg attained their unique degree of political influence by having prepared a diagnosis, but also a remedy, before it was evident to outsiders that such extreme measures were really needed.

The German Warburg was concerned with a different sort of risk to financial stability than the American, whose concern was over-dependence on stock exchange loans. The issue was the increasing diplomatic and military tensions in Europe after the first Moroccan crisis. Market participants were beginning to think about war, and its potential consequences in an internationally interdependent system. Riesser's textbook on German banks had laid out how financial war plans might work: ‘The enemy may endeavor to aggravate a panic . . . by the sudden collection of outstanding claims, by an unlimited sale of our home securities, and by other attempts to deprive Germany of gold. Attempts may also be made to dislocate our capital, bill, and securities markets, and to menace the basis of our system of payments’ (Riesser Reference Riesser1911, p. 23). Warburg formulated the policy task as ensuring that war finance did not disturb the gold standard or the norms of the peacetime economy, and that preparations for war did not cramp German development or change the nature of its business structure. Germany would be strong enough to stand the panic sales that would come about in the case of conflict only if it could develop a really deep financial market: hence, for different reasons but with the same logic as Paul, he recommended not only the acquisition of a substantial privately held portfolio of foreign securities, but also the development of a German acceptance market that would permit operations in government securities.

Warburg started his presentation at the bankers’ conference by refuting the commonly held idea that a future war would necessarily be short. He then drew some lessons from the stunningly successful Japanese financial mobilization in the war with Russia. Unlike Japan (or indeed Russia), Germany could not rely on allies that would promote bond issues. Instead there was a simple message: ‘The state which creates the highest form of development for its monetary and payments mechanism, and through the best organization of its banks and stock exchanges supplies currency with the least risks, has the advantage in the struggle of nations.’ He concluded: ‘It would be a wicked shortsightedness not to recognize how vital for domestic confidence and for the final success in war it is whether our economic order supports the course of military events or proves itself to be a constraint on the deployment of our power.’Footnote 10

The financial crisis offered a test case of how financial insecurity would operate. In the fall of 1907, as the US drew gold across the Atlantic, interest rates surged, and the Reichsbank was supposed to have failed in its responsibilities to protect the German economy. The longstanding president, Richard Koch, was let go, and replaced by an official from the Prussian State Bank (Seehandlung), Rudolf von Havenstein (Borchardt Reference Borchardt and Bundesbank1976, p. 47). As in the United States, private banks played the central role in restoring confidence and stability. The Warburg bank took on some of the attributes of J. P. Morgan on the other side of the Atlantic by acting as an intermediary for foreign sales that stabilized the market. Notably it skillfully managed to sell German government securities in the middle of the panic to Japan. But further reform was needed. A Bank Inquiry was instituted, whose remit included a discussion of how vulnerability might be reduced by limiting the expansion of bank credit; and how government securities could be brought in as the basis or secure asset of a more stable monetary system. The debates of the German Inquiry were subsequently translated into English for the US National Monetary Commission and represented one of the starting points for its deliberations.

Max Warburg was not the only German financier to push for reform. Riesser also prepared a book-length statement about financial preparations for war. Karl Helfferich of Deutsche Bank (the future mastermind of Germany's financial mobilization during World War I) also had a book on the lessons of Japan's victory over Russia in the 1905 war. Arthur Fischel of the Berlin bank Mendelssohn, which like the Warburg bank was intimately concerned with the management of German government debt, noted that:

There are three leading countries of prime economic importance and making use of a vast amount of gold in their business transactions which have the gold standard and therefore are equally interested in having a continuous stream of gold coming to them, with the result that they are active competitors in this regard. But apart from the fact that these three countries are very differently situated with respect to the advantages which they possess for procuring their gold, there are essential differences with regard to the terms prescribed in the matter of the purchase of gold. These three countries are England, the United States, and Germany. (Havenstein Reference Havenstein1908, p. 451)

He then concluded that Germany was making some progress: ‘As a result of our energetic way of doing business, the German bill of exchange is now also accepted, if not to the same extent as the English, at least to such an extent that our industry is thereby greatly benefited’ (Havenstein Reference Havenstein1908, p. 458).

In the years after the 1907, the only partially complete German financial preparations seemed slowly to be proving themselves. In the 1911 panic that followed the Moroccan crisis, the attempted financial attack was quickly thwarted. Max Warburg later proudly noted that the Paris market had been more shaken by the crisis of confidence than Berlin or Hamburg, and that his house had been able to assist a Russian bank that suffered liquidity problems in Paris.Footnote 11 The best account of the German response to the politically driven panic was given by Paul Warburg, who had an inside view of the crisis, in the Bankers’ Magazine:

When France, for reasons just explained and as a means of political pressure, withdrew from Germany more than 200 million marks that temporarily had been invested there, when English and Russian money was called back, when runs began upon savings banks, Germany had to face a very severe strain. But what happened? The German Reichsbank rapidly increased its credit facilities by about $150,000,000; moreover, it had accumulated in times of ease vast sums of foreign bills, and when rates of exchange moved up to a point warranting gold exports it began to sell these foreign holdings. At the same time a comparatively slight increase in its rate took place which brought new money, mainly American, to Germany's assistance. This inflow of foreign money was increased by the sale abroad of German treasury notes. What would have become of Germany without the Reichsbank?Footnote 12

There was still no complete security on the German market. Max Warburg continued to reflect on the British advantage, an exorbitant privilege that resulted not so much from the rules of the currency regime but from the highly developed character of the City's acceptance business that allowed firms with a very small capital base to undertake large-scale financing operations. During the Great War, he reflected in a letter to Ballin on Britain's continuing advantage, but also on its potential fragility:

In regards to finance, I don't underestimate England, the country up to now has lived on an enormous bluff . . . The people there are shameless, and I am firmly convinced that the War will at least bring the advantage that we won't let ourselves be so impressed by English soap bubbles. I believe that the English acceptance will be seriously damaged.Footnote 13

IV

The underlying idea or vision of the two Warburgs was fundamentally pacific: that a better distribution of financial capacity would make the world a more balanced and thus a more stable place. In their view, financial unipolarity or over-dependence on Britain as the center of the financial order made the world inherently dangerous. The structures that they devised held out the possibility of a model of central banking that could be exported to a wide range of countries, and would make for greater financial stability. In a similar spirit, in October 1913 the young Cambridge economist John Maynard Keynes drew up a memorandum on Indian currency reform in which he suggested a bank in which three banks in Calcutta, Bombay and Madras would form the head offices of a federal system analogous to the new Federal Reserve System or the German Reichsbank (Skidelsky Reference Skidelsky1983, p. 280).

The British strength, and the vulnerability elsewhere that the Warburgs had identified, increased because of the heightened concern of financial markets with security and with the arms race. The logic of the Warburgs’ argument required that other countries should develop their own financial infrastructure. A strong domestic financial system, underpinned by a safe asset would produce a reserve, a defense against attack, or a deterrent. In the US case, mechanism would be built around the commercial bill or bill of exchange, in the German case around government securities.

In June 1914, Max Warburg met Kaiser Wilhelm at a private dinner in Hamburg, where the issue of prevention and deterrence formed the center of the discussion. Max Warburg left a record of the conversation:

Oppressed by his worries, he even wondered whether it might be better to strike first than wait. I did not in fact have the impression that he was thinking seriously of a preventive war, but his gloomy assessment of the situation caused me dismay. I replied that I nonetheless saw things differently, Germany was becoming stronger with every year of peace. Waiting further could only bring us gains.Footnote 14

German and American financial reforms would free their economies from British financial hegemony. Even after war broke out, Warburg managed to convince the German government to send a high-level representative, Bernhard Dernburg from the German Colonial Office, to New York to arrange for the issue of a German bond on the US market: in practice, however, Dernburg arrived too late for this initiative to stand any chance of success. On a private charitable basis, Warburg did manage to continue German–American cooperation, however, in 1915: in particular in establishing with American money committees in support of the ‘unfortunate Jews’ in Poland and Galicia.Footnote 15

In the last-minute discussion with the Kaiser, Max had articulated the argument that the policy of building financial capacity as a security reserve would take time, and that financial strength both required and contributed to a peaceful international order. That view was also set out in political discussions on the other side of the Atlantic. While the US was still neutral, Paul Warburg was warning Colonel House that ‘the longer the war lasts the clearer will it become that the suffering and the burdens of the war will be out of proportion to its causes, and the feeling will gain the upper hand that, after all, we should have kept out of it’ (Chernow Reference Chernow1993, p. 161). From Hamburg, Max Warburg delivered a similar message to the German leadership, urging that on no account should Germany risk a break with the United States: ‘We should do our utmost to be in good standing with America, as we are only in the second act of the drama. The belligerent countries are preparing to continue the economic fight after the war.’Footnote 16

The one-sided ability to mobilize financial resources had given Britain an unfair advantage in diplomatic confrontations, and as a result led Britain to play a game of chicken in which it could frighten its opponents because of the vulnerability posed by their more rickety (in the American case) or underdeveloped (in the German case) financial infrastructure. That was part of the fatal brinkmanship of the summer of 1914. The financial system was part of the power mechanism, and a strong financial system was a deterrent against diplomatic pressure and the threat of military action. Germany's preparations for war were less complete on the financial side than in the military domain. The consequent ineffectiveness of the financial deterrent was a contributor to the destabilizing imbalance that existed at the time of the July crisis. Yesterday's deterrent did not work.

The political impetus of the project – an assertion of financial power by rising powers against the established financial center – remained, amazingly, even while the US and Germany were engaged in military conflict. Volker Berghahn has recently traced the trajectory of a financial vision, propagated by figures such as Frank Vanderlip and later Charles Dawes, Owen Young and John Foster Dulles, which survived World War I, the Depression and World War II, and which used Germany as an alternative to restrain and supplant British power (Berghahn Reference Berghahn2014). Max Warburg consistently tried to set out the underlying logic of precisely this position during World War I. ‘I know,’ he said, ‘at least in Europe, of no place where I feel freer than in Germany’ and argued that if the US ever threatened Britain's position, Britain would turn to strangle the American challenge (Chernow Reference Chernow1993, p. 169). In a fascinating memorandum prepared for the German government on the question of submarine warfare he argued that although the submarine and air attacks (from Zeppelins) weakened British security and hence also the London acceptance market, unconditional submarine warfare should be avoided as it would in practice lead to greater US willingness to finance the British war effort.Footnote 17

The debates of that time have had long-term consequences. First, it is still common to think of reserves in terms of security interests and a zero-sum game logic. That thinking underlay some of the criticism of the Federal Reserve's willingness to extend currency swaps to other central banks during the recent financial crisis.

Second, the debate after 1907 about the desirability of developing the acceptance market also laid the foundation for policy mistakes in the subsequent monetary histories. A correct monetary response was seen as responding to the need for commercial credit as judged by the extent of the market for commercial bills. The American approach – a version of the real bills doctrine – made for severe deflation in the early 1920s and early 1930s (as in both instances there appeared to be a shortage of genuine trade bills, because commerce was collapsing). The German outcome appeared radically different, but its intellectual foundation was the same. In an environment characterized by what is now referred to as fiscal dominance, when state debt was used as a basis for money creation, and a larger volume of commercial bills was on offer as a consequence of monetized debt, the central bank continued to lend or buy (and thus monetize) commercial paper. The stage was thus set for the catastrophic inflation and hyperinflation of the 1920s.Footnote 18

In the aftermath of the recent financial crisis, a logic can be observed similar to that that one century ago drove German and American bankers to want to reform their financial institutions. The US, although it was the original epicenter of the 2007–8 financial crisis, pulled through better than other advanced industrial areas because of the depth and sophistication of its financial system. The experience has prompted in Europe and also in Asia a wide-ranging discussion of how the sophistication and robustness of the American system can be emulated, just as Germans and Americans wondered after 1907 how they should learn from the model of the City of London and the Bank of England.

As one century ago, the European and Asian emulators focus on different points. For Chinese policy-makers, the central focus is on giving China a much greater role in trade finance, with a rapidly increasing proportion of foreign trade being denominated in renminbi. They are reproducing the American debate of the turn of the century. For Europeans, the interest lies in establishing a better market for government bonds, and would involve moving to a standardized security such as the US Treasury bill. This is the equivalent of the German discussion of a hundred years ago. There are many European economists, as well as outsiders, who see the virtues of the early American experience when Alexander Hamilton built the new Republic around a consolidated national debt (he treated the debt as ‘the strong cement of our Union’). But that demands internal political and constitutional changes in the European Union that may be difficult to contemplate – just as a full development of Germany's debt market in the early twentieth century would also have required ultimately a much more extensive process of constitutionalization.