1. Introduction

In this paper, we investigate hierarchy effects in a specific type of German copula clause: so-called “assumed identity” constructions (Heycock Reference Heycock2012, Béjar and Kahnemuyipour Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017).Footnote 1 In these constructions, one DP is assigned the role or place of another DP, for example in the context of assigning roles in a play or during a game of charades. Two illustrative examples are provided in (1) ((1b) is adapted from Béjar and Kahnemuyipour Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017: 483).

Assumed-identity constructions differ in a number of respects from more standard types of copular constructions like predicational, specificational, and equative constructions, examples of which are shown in (2).

One important property of assumed-identity sentences is that the pre-copula DP (which we will refer to as “DP1” here) and the post-copula DP (which we will call “DP2”) are evaluated with respect to different worlds or scenarios. That is, (1a) does not claim that Mary and Ms. Brown are the same person in the actual world. Rather, the sentence conveys that Mary in the actual world is impersonating Ms. Brown in the play. As a result, inverting DP1 and DP2 does not preserve the truth conditions of the sentence. For example, in the context in (1b), the role assignment Mary is Sally is true, but the role assignment Sally is Mary is not. In this respect, assumed-identity sentences differ from the types of copular constructions in (2): While the sentence Your parents are the problem differs from The problem is your parents with respect to its information structure, they are truth-conditionally identical (Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005). This contrast can be seen particularly clearly from the fact that negating the inverted order does not lead to a contradiction for assumed-identity sentences (see (3)), but it does for the copula constructions in (2) (see (4)).

In this article, we investigate and analyze a restriction on the relative person and number values of the two DPs in assumed-identity sentences in German, a phenomenon that has also been observed for Spanish by Béjar (Reference Béjar2012, Reference Béjar2017). For person, the restriction prohibits a combination of a 3rd person DP1 and a 1st or 2nd person DP2, while the inverse is allowed, as in (5). Because 1st and 2nd person pronouns pattern together with respect to this restriction, we refer to them together as “part(icipant).” For number, the restriction prohibits configurations in which DP1 is singular and DP2 is plural; the reverse is allowed. Assumed-identity sentences are crucial because the truth-conditional differences which arise when the two DPs are reversed permit us to abstract away from the independent possibility of syntactic inversion, discussed further in section 4 below.

In contrast to German, no hierarchy effects exists in English. Here, all person and number combinations are allowed.

(7)

a. He is me.

b. He is them.

In section 2, we report on the results of two sentence-rating experiments that investigate the German contrasts in (5) and (6), and compare them to the English pattern in (7).

We develop an analysis of the German restriction that connects it to the Person Case Constraint (PCC), a family of prohibitions against certain person combinations in ditransitive constructions. An example of the PCC from Catalan is provided in (8). Here, ditransitive constructions in which the indirect object is 3rd person and the direct object is 1st or 2nd person are ungrammatical, whereas the inverse is possible.

Both the German restriction and the PCC instantiate hierarchy effects: given the descriptive person hierarchy in (9a), configurations in which a structurally higher DP (DP1 in the copula constructions; indirect object in ditransitive constructions) is lower on the hierarchy than a structurally lower DP are ungrammatical. In section 3, we propose that existing licensing-based accounts of the PCC can be extended to the copula restrictions.Footnote 2 Our account connects the emergence of hierarchy effects in German copula constructions to the fact that both DPs are nominative in this construction and are hence plausibly licensed by the same head. This also accounts for the absence of hierarchy effects in English, where DP2 is accusative. This unification has a number of implications. First, assumed-identity clauses present a new empirical domain in which hierarchy effects arise. Second, an important difference between the copula restriction and PCC effects is that the copula restriction also encompasses number (see (6)). Thus, in addition to the person hierarchy (9a), the constructions are constrained by the analogous number hierarchy (9b). This differs strikingly from PCC effects, which never seem to display sensitivity to number (Nevins Reference Nevins2011). While this difference between the two phenomena might at first glance suggest that they should not be analytically unified, we propose in section 3.2 that it can be attributed to an independent difference: PCC effects involve clitics, while the German copular clauses do not.

(9)

a. participant > 3

b. plural > singular

Finally, in section 4, we place the hierarchy restriction in assumed-identity sentences and our account of it into the broader context of agreement restrictions in other types of copular clauses. We investigate to what extent our account can shed light on such agreement restrictions and how it relates to other lines of explanation that have been proposed for these restrictions. We ultimately conclude that while our account formalizes a novel constraint on predication structures, it should be seen as complementing, rather than replacing, previously proposed semantic constraints on such structures.

2. Experiments

This section reports on an experimental investigation of the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity sentences. The results of these experiments support the claim that copular constructions are subject to the person hierarchy in (9a) and the number hierarchy in (9b) in the sense that German copula constructions are ineffable if DP2 is higher than DP1 on either of these hierarchies.Footnote 3 A number of factors motivate an experimental investigation. First, the intuitive judgments are not entirely crisp for many speakers. While the native speakers we have consulted generally agree with the asymmetry we report, the exact grammatical status of hierarchy-violating configurations is somewhat unclear. Second, assumed-identity sentences (in particular ones that involve a number mismatch such as (6)) are semantically marked, which we suggest increases variability in the judgments. Third, an experimental investigation provides quantitative data that can be used to assess our claim that English differs from German in not exhibiting hierarchy effects in assumed-identity configurations.

2.1 Experiment 1

Experiment 1 investigates the status of assumed-identity sentences like (10a) and (10b) in both English and German and compares them to uncontroversially ungrammatical control structures.

2.1.1 Design

In this experiment, we systematically manipulated the person and number specification of DP1 and DP2. To elicit ratings for the assumed-identity interpretation, a role-playing background was provided in which specific roles were assigned. For example, the sentence in (10) corresponds to the instruction that the hearer is to play the role of John. Each trial in the experiments presented one copular clause preceded by a context sentence.

(10)

a. [pointing at you, then at your friend John]

You are him.

b. [zeigt auf dich, dann auf deinen Freund Karl]

Du bist er.

Participants were asked to rate each sentence on a 6-point scale with “1” being completely unacceptable and “6” being completely acceptable.Footnote 4

As a control condition, the experiment included uncontroversially ungrammatical sentences in which the verb agreement is inconsistent with either argument (*You am him; *Du bin er). Twenty-three participants took part in the English experiment. The German experiment had 15 participants.

Because the items in the experiments only used pronouns, one unusual consequence of the type of sentences of interest here is that it is impossible to lexically vary the target structures (e.g., You are him). Because there is only one possible lexicalization of each condition, we did not manipulate item as a random effect. As a result, all participants saw the same sentences, but the order of presentation was randomized.

2.1.2 Results

While the items we used contained every possible person and number combination of DP1 and DP2, we will limit our attention primarily to the role of person and number hierarchies in (9) above. We consequently put aside combinations in which (i) DP1 is 1st person and DP2 is 2nd person (“1 > 2”) or (ii) DP1 is 2nd person and DP2 is 1st person (“2 > 1”); for these see footnotes 6 and 7.

The distribution of ratings for the person hierarchy from (5), averaged over number, is given in the form of boxplots in Figure 1(a). “3 > Part” represents the distribution of ratings for configurations in which DP1 is 3rd person and DP2 is a participant (i.e., 1st or 2nd person). “Part > 3” correspondingly refers to configurations where DP1 is a participant DP and DP2 is 3rd person. Finally, the column “Plateau” represents configurations in which both DPs instantiate the same person value (i.e., 1 > 1, 2 > 2, and 3 > 3). The number above each boxplot represents the condition mean. Analogous boxplots for the number hierarchy in (6) are provided in Figure 1(b). Here, the column “Plateau” refers to SG > SG and PL > PL configurations.

Figure 1: By-condition distribution of ratings in Experiment 1. The numbers above each plot represent the condition mean.

We analyzed the data using cumulative link mixed-effects regression modeling, using the R package Ordinal (Christensen Reference Christensen2015).Footnote 5 We fitted a model that predicted rating responses from the predictors (i) person hierarchy (Part > 3 vs. 3 > Part vs. Plateau), (ii) number hierarchy (SG > PL vs. PL > SG vs. Plateau), (iii) language (English vs. German), (iv) the interaction between person and language, and (v) the interaction between number and language. The factor language was sum-coded (English: –.5; German: .5). The 3-level factors person and number were Helmert-coded. In each case, the first comparison contrasted plateau configurations (coded as −2/3) with the two non-plateau ones (coded as 1/3). The second contrast compared the two non-plateau configurations to each other (for person Part > 3: –.5, 3 > Part: .5, Plateau: 0; for number PL > SG: –.5, SG > PL: .5, Plateau: 0). The models comprised the full random-effects structure, namely, random intercepts and slopes by participants for all fixed effects and the correlations between them.

The coefficients of this model are provided in Table 1(a), where “plt” abbreviates “plateau.” The model revealed significant main effects of the person and number hierarchy: Part > 3 configurations are rated higher than 3 > Part configurations and PL > SG structures are rated as better than SG > PL. Crucially, there was an interaction between these hierarchies and the factor language such that the effect of the two hierarchies was greater in German than in English.

Table 1: Results of cumulative link mixed-effects modeling for Experiment 1 (see main text for details)

***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05

In order to investigate these interactions more closely in the individual languages, we fitted a second model that nested the predictors person hierarchy and number hierarchy under the levels of the factor language. The full random-effects structure of the original model was preserved. The coefficients for this model are provided in Table 1(b). The model detected that in German, 3 > Part configurations are degraded relative to Part > 3 configurations, and that SG > PL is worse than PL > SG. Interestingly, we also found that English shared with German the preference for Part > 3 over 3 > Part. Notably, however, this effect was significantly smaller in English than in German. This effect may reflect a pragmatic preference for encoding a participant argument rather than a 3rd person argument as the subject, given the inherent availability (and topicality) of the participants of the discourse. Importantly, because the effect was significantly larger in German, it seems to go beyond this pragmatic effect.Footnote 6

Finally, the control items, which involved agreement on the copula that is compatible with the features of neither DP1 nor DP2 (e.g., *You am he; *Du bin er), and which are hence uncontroversially ungrammatical, received a mean rating of 1.4 in both English and German.

2.1.3 Discussion

The results provide evidence that assumed-identity copula constructions are subject to the person hierarchy (9a) and the number hierarchy (9b) in German. Configurations in which DP1 is lower in the hierarchy than DP2 are degraded. If DP1 is higher than DP2 or if they are equal, no such degradation ensues. The interactions of both hierarchies with the factor language (in the full model) reveals that the size of the effects is significantly greater in German than in English, and hence that these effects go beyond mere effects of pragmatics in German (as any pragmatic effect would also be present in English).

We should note, however, that while the configurations that violated the hierarchies received reliably lower ratings in German, they still received a relatively high rating compared to our ungrammatical controls (4.8 in Figure 1(a) and 4.4 in Figure 1(b), vs. 1.4 for the controls). One reason for this difference may be that in our control cases, agreement is incompatible with either DP, an error that is easily detectable, while in our test sentences, verb agreement is consistent with one of them. A second relevant factor, which we will investigate more closely in Experiment 2, is that hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences are ineffable, in the sense that they do not have a grammatical counterpart apart from forgoing the use of the copula in favor of a full accusative-assigning predicate. The lack of a clearly grammatical competitor might therefore have increased the ratings of the hierarchy-violating sentences. We return to this question in Experiment 2 and again in section 4 below.

Another worry one may have is to what extent pragmatic effects like the one observed in English may confound issues. Obviously a pragmatic account would not differentiate between the languages to account for the observed interactions, but there are other reasons to think that the nature of the phenomenon is really syntactic. For example, an assumed-identity sentences with a “camouflage DP” (Collins and Postal Reference Collins and Postal2012) such as meine Wenigkeit ‘my negligibility,’ which refers to the speaker but is syntactically third person, is entirely acceptable, in contrast to (5a):

Such examples are parallel to hierarchy-effect rescues in other languages, for example the use of a camouflage reflexive object in Georgian to ameliorate PCC violations (Harris Reference Harris1981), or the grammaticality of a 2nd person formal pronoun which agrees like a 3rd person pronoun in Kaqchikel Agent Focus hierarchy effects (Preminger Reference Preminger2014). Cases like these demonstrate that ungrammaticality cannot be attributed to the pragmatic (un)naturalness of a 1st or 2nd person discourse participant in a certain role, but rather must be connected to the grammatical features themselves, as in our analysis below.

2.2 Experiment 2

Experiment 1 tested only hierarchy-violating configurations in which the copula agrees with DP1. These configurations are degraded, but it is not clear, all else being equal, whether they are degraded because the underlying PredP structure is deviant, or because these configurations require the verb to agree with DP2, which in hierarchy-violating configurations is featurally more marked. Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017) demonstrate that assumed-identity sentences in Eastern Armenian display precisely such a requirement for the copula to agree with the more marked DP, as illustrated in (12).

(Béjar and Kahnemuyipour Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017: 483)

Because the 1st and 2nd person DP2 is featurally more marked than the 3rd person DP1 in (12), the verb is required to agree with DP2, and the corresponding DP1-agreement counterparts are ungrammatical.

The results of Experiment 1 indicate that DP1 agreement is impossible in hierarchy-violating configurations in German, but the results leave open the question of whether DP2 agreement is licit. Native-speaker intuitions clearly indicate that it is not. For example, the sentence in (13) is ungrammatical on the interpretation ‘He is me,’ that is, with er ‘he’ being the subject of predication and ich ‘I’ being the predicate, which is to say, it cannot convey that he is playing the role me; recall from section 1 that assumed-identity copula constructions crucially have different truth conditions when the DPs are reversed. The surface string in (13) is grammatical only on the interpretation ‘I am him.’ We take this to indicate that this construction has a hierarchy-obeying base structure, agreement with the underlying DP1, and that the surface order is the result of V2-induced inversion (discussed further in section 4).

Experiment 2 is a replication of the design of Experiment 1, but also investigates experimentally the status of DP2 agreement in sentences like (13) in a way that allows a direct comparison between the two.

2.2.1 Design

The test items used in Experiment 2 were identical to those used in Experiment 1. In addition to these test items, Experiment 2 involved control sentences such as (14).

These sentences were preceded by a context sentence (in German) that conveyed the intended meaning. In the sample item in (14), the intended interpretation is that Josef is playing the role of the speaker. Under this interpretation, er ‘he’ is the subject of the underlying predication, and in this interpretation, (14) hence requires a DP2 agreement structure. In light of the intutive judgment reported in (13), we expect (14) to be rejected on the given interpretation, and in this respect, it should thus differ from the Eastern Armenian pattern in (12).

A group of 16 participants took part in Experiment 2. The analysis was identical to that used for Experiment 1, with the exception that we did not conduct an analogous experiment for English, and we therefore did not include a by-language comparison. As in Experiment 1, we separated 1 > 2 and 2 > 1 configurations because they are not of immediate interest to the critical questions about the role of the person and number hierarchies in (5) and (6) (see footnote 7 for analysis of these configurations).

2.2.2 Results

The by-condition means for the test items, which were identical to Experiment 1 and involved DP1 agreement, are given as boxplots in Figure 2.

Figure 2: By-condition distribution of ratings in Experiment 2. The numbers above each plot represent the condition mean.

We analyzed the results using cumulative link mixed-effects modeling using the contrast coding from Experiment 1. Responses were predicted from (i) the person hierarchy (Part > 3 vs. 3 > Part vs. Plateau) and (ii) the number hierarchy (SG > PL vs. PL > SG vs. Plateau). The model comprised the full random-effects structure. The coefficients of this model are provided in Table 2. The model detected an effect of the person hierarchy such that “3 > Part” configurations were rated significantly worse than “Part > 3” configurations. The model also detected an effect of the number hierarchy such that plateau configurations received higher ratings than non-plateau ones. Furthermore, there was a numerical difference between “SG > PL” configurations and “PL > SG” ones with “SG > PL” receiving lower ratings, but this contrast did not reach significance (![]() $\widehat{{\rm \beta}} = -0.51 \pm 0.33,\,z = -1.54,p = 0.12$).Footnote 7

$\widehat{{\rm \beta}} = -0.51 \pm 0.33,\,z = -1.54,p = 0.12$).Footnote 7

Table 2: Results of cumulative link mixed-effects modeling for Experiment 2

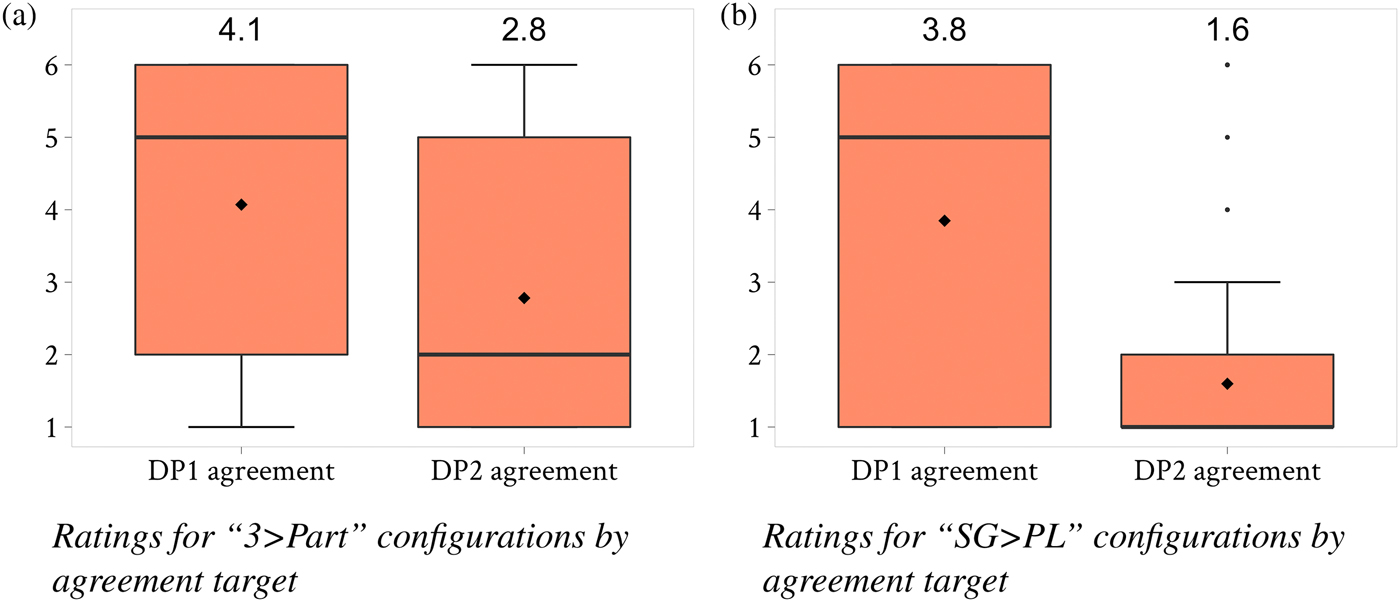

Next, we analyzed the hierarchy-violating configurations in which the copula shows DP1 agreement with the corresponding control items in which the copula agrees with DP2 (see (14)). For the person hierarchy, “3 > Part” configurations with DP1 agreement received a mean rating of 4.1 (see Figure 2(a)). Person hierarchy-violating sentences with DP2 agreement received a mean rating of 2.8. The distribution of ratings by condition are given in the form of boxplots in Figure 3(a). We used cumulative link mixed-effects modeling to assess the robustness of this difference. Limiting the data set to “Part > 3” configurations, we applied a model that predicted rating responses from copular agreement (DP1 vs. DP2). This model revealed that DP2 agreement structures were rated significantly lower than DP1 agreement structures (![]() $\widehat{{\rm \beta}} = -1.3 \pm 0.32,\,z = -4.0,p \lt. 001$).

$\widehat{{\rm \beta}} = -1.3 \pm 0.32,\,z = -4.0,p \lt. 001$).

Figure 3: Comparison of DP1 agreement and DP2 agreement in person and number hierarchy-violating configurations.

An analogous comparison was carried out for number hierarchy-violating configurations. “SG > PL” configurations with DP1 agreement received a mean rating of 3.8 (see Figure 2(b)); analogous configurations with DP2 agreement received a mean rating of 1.6. The distribution of ratings is shown in Figure 3(b). Cumulative link mixed-effects modeling that predicted rating responses from copular agreement (DP1 vs. DP2) revealed this difference to be significant (![]() $\widehat{{\rm \beta}} = -2.6 \pm 0.40,\,z = -6.4,\,p \lt. 001$).

$\widehat{{\rm \beta}} = -2.6 \pm 0.40,\,z = -6.4,\,p \lt. 001$).

2.2.3 Discussion

The results of Experiment 2 replicate the person-hierarchy effect observed in Experiment 1. Furthermore, there was a numerical effect of the number hierarchy, which is compatible with the results of Experiment 1, but which did not reach significance in the statistical analysis. This might be taken to indicate that the effect of the number hierarchy is less robust than that of the person hierarchy. It is not clear at present whether this reflects a difference in the quality of the effect or a pragmatic difference (as number mismatch configurations are pragmatically marked to begin with, see the results for English in Experiment 1). Overall, the results of the DP1 agreement stimuli in Experiment 2 are thus consistent with those of Experiment 1.

Furthermore, we observed that agreement with DP2 in hierarchy-violating configurations not only does not improve these sentences, but in fact leads to significantly lower ratings for both hierarchies. This finding confirms experimentally the native-speaker intuitions reported in (13): copula agreement with DP2 is impossible, even in hierarchy-violating configurations, in contrast to so-called specificational copula constructions as in (30) below. This result also shows that our rather sparse contexts were successful in conveying the intended reading.

The results of Experiment 2 provide evidence that hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences are indeed ungrammatical (or at least severely degraded), regardless of which DP the verb agrees with. These configurations are simply ineffable, independently of the choice of agreement controller. In this respect, the situation in German clearly contrasts with that in Eastern Armenian (12).

3. Person, number, and the PCC

The results presented in the preceding section indicate that hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences are ungrammatical in German, and that this ungrammaticality holds whether the copula agrees with DP1 or DP2. In this section, we will investigate the analytical consequences of this restriction. Building on earlier work in Coon et al. (Reference Coon, Keine, Wagner, Lamont and Tetzloff2017), we show that this pattern closely matches hierarchy effects observed in other domains, in particular the Person Case Constraint (PCC), already mentioned in section 1. As noted above, the PCC prohibits combinations of arguments with certain person features, most frequently discussed in combinations of multiple internal arguments, as in ditransitive constructions (see Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2017 for a recent overview).

We propose that the hierarchy effects in German copulas arise in the same types of environments that have been proposed to cause hierarchy effects in both the PCC and a variety of other constructions cross-linguistically – namely, configurations with two accessible DPs in the domain of a single agreement probe – and that the two can be given a unified account. A similar unification of the hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences with the PCC is explored in Béjar (Reference Béjar2012), though see Béjar (Reference Béjar2017) for critical discussion. Like other recent work in this domain (e.g., Béjar and Rezac Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003, Reference Béjar and Rezac2009; Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou, Heggie and Ordoñez2005; Adger and Harbour Reference Adger and Harbour2007; Nevins Reference Nevins2007; Preminger Reference Preminger2014), we maintain that hierarchy effects are derived from independent morphosyntactic principles; the hierarchy itself has no independent status in the grammar. We offer an account of why German also shows number effects, while the PCC is famously limited to person.

3.1 German copulas and the PCC

We focus first on the person hierarchy effects. The generalization governing the distribution of person features in German copula constructions parallels the one governing the combinations of direct and indirect object clitics in PCC configurations. An examples from Catalan is repeated from (8) in (15). While the 2 > 3 configuration in (15a) is grammatical, the reverse configuration in (15b)—along with 3 > 1 configurations—is ungrammatical.

(Bonet Reference Bonet1991: 178–179)

PCC effects are found in a wide range of unrelated languages, and while there is cross-linguistic variation internal to PCC effects (see, e.g., Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou, Heggie and Ordoñez2005, Reference Anagnostopoulou, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2017; Nevins Reference Nevins2007; Pancheva and Zubizarreta Reference Pancheva and Zubizarreta2018), there are at least three facts about the PCC that are relevant to the discussion here: (i) the PCC is not a ban on specific configurations of arguments, per se, but rather on combinations of “phonologically weak” elements, usually pronominal clitics (e.g., Bonet Reference Bonet1991, Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou2003, Béjar and Rezac Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003, Preminger Reference Preminger2019); (ii) the PCC is syntactic, and cannot be reduced to problems with the specific morphological realization (e.g., Rezac Reference Rezac2008); and (iii) despite variation, violations arise only when the lower argument (the direct object in ditransitives) is 1st/2nd-person – there is no corresponding restriction with respect to number (e.g., Nevins Reference Nevins2011).

For the purposes of this article, we focus primarily on combinations involving a 3rd person DP and a participant (i.e., 1st or 2nd person) DP. Across both PCC configurations (with a higher indirect object and a lower direct object) and German copula constructions (with a higher subject and lower predicate nominal), we find that the hierarchy-obeying configuration in (16a) is grammatical, while the hierarchy-violating configuration in (16b) is ungrammatical.

Recall that combinations of two participant DPs are grammatical in the German sentences. There is variation in PCC as to whether combinations of participant DPs are allowed, but such combinations are grammatical in some PCC languages. This version of the PCC is usually referred to as the “Weak PCC,” and it is instantiated by Catalan, as shown in (17).

The person restriction we observed in the German data is therefore analogous to that in Weak-PCC languages, and we suggest that both are manifestations of the same underlying phenomenon. We thus propose that recent accounts of the PCC should be extended to the copula restrictions. Recent accounts of the PCC connect hierarchy violations like the ones in (16b) above to a configuration in which the two DPs are in the domain of a single agreeing probe, as in (18). We argue that it is exactly this property of German copula constructions which causes the hierarchy effects observed in the previous section (see also Béjar Reference Béjar2012).

Under one family of approaches, the ungrammaticality of forms like (15b) is attributed to a failure of nominal licensing (e.g., Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou2003, Reference Anagnostopoulou, Heggie and Ordoñez2005; Béjar and Rezac Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003; Adger and Harbour Reference Adger and Harbour2007; Baker Reference Baker2008; Preminger Reference Preminger2019). Simplifying somewhat, the underlying idea is that 1st and 2nd person DPs bear a [ + part(icipant)] feature, and this feature must be licensed by entering into an Agree relationship with a functional head, as proposed by Béjar and Rezac (Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003: 53).Footnote 8

Ungrammaticality arises when a lower [+ part] DP is blocked from agreeing with the licensing probe by an intervening higher DP, as schematized in (20). In the reverse configuration, in (21), the higher DP is successfully licensed by the probe while the lower 3rd-person DP does not need to be licensed, in virtue of being [–part].

This intervention-based account derives the basic contrast between grammatical 1>3 and 2>3 configurations on the one hand and ungrammatical 3>1 and 3>2 configurations on the other. What about combinations of two [+part] DPs? All else being equal, these are predicted to be ungrammatical. Nevins (Reference Nevins2007) proposes a Multiple Agree account (Hiraiwa Reference Hiraiwa and Matushansky2001, Reference Hiraiwa2005; Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou, Heggie and Ordoñez2005) of such configurations, according to which a single probe may under certain circumstances agree with two DPs. We adopt this approach within the licensing-based account we assume. Nevins (Reference Nevins2007) proposes that Multiple Agree is subject to Contiguous Agree in (22).

Nevins (Reference Nevins2007) proposes that probes may be relativized to certain features. The condition in (22) then states that (Multiple) Agree between this probe and a DP matching this feature is possible only if all intervening features also bear this feature. Applied to the case at hand, the relevant probe is relativized to [+part]. As a result, it is possible for this probe to agree with two participant DPs, as in (23). As a result of this Multiple Agree, both [+part] DPs are licensed, and the structure is well-formed.

By contrast, in 3>1 and 3>2 configurations, Multiple Agree is ruled out because a [–part] intervenes between the probe and the lower [+part] DP (see (20)). The latter remains unlicensed, and ungrammaticality results.

This type of account provides an explanation for why hierarchy effects arise precisely in copula constructions in German. These are the configurations in which we find two DPs in unmarked nominative case that are in need of licensing by T, as schematized in (18) above. Because both DPs need to be licensed by the same head, interference arises, which manifests in hierarchy effects. By contrast, in standard transitive sentences the object bears accusative case and is hence licensed by a head other than T (presumably v). Because the subject does not intervene between v and the object DP, no hierarchy effects obtain. This account also gives us a rationale for why no such hierarchy effect arises in English assumed-identity sentences. In English, DP2 appears in the accusative case. It thus stands to reason that DP2 is licensed by a head other than T. If so, no intervention by the subject obtains, and hierarchy effects are absent.Footnote 9

As noted above, there is an important difference between PCC and copular environments. The PCC is specifically about person features; there are apparently no attested cases of “Number Case Constraint” (NumCC) effects in the domains for which PCC effects have been described (Nevins, Reference Nevins2011). In German copulas, however, we found hierarchy effects for both person and number. While this may initially seem to suggest that the two phenomena should not be treated on par, we argue below that the appearance of number effects is derivable from independent differences between the two constructions.

3.2 Deriving the presence and absence of number effects

One important account of the asymmetry of person and number with respect to hierarchy effects is developed by Nevins (Reference Nevins2011), who proposes that this asymmetry reflects an ontological difference between person and number features. Specifically, Nevins (Reference Nevins2011) proposes that person features are binary, while number features are privative. Thus, while 3rd person contains a negative feature specification ([–part]), singular number corresponds to the absence of a feature. For Nevins (Reference Nevins2011), this means that while a 3rd person (hence, [–part]) DP intervenes for Agree with a lower [+part] DP creating a person hierarchy as in (20) above, no such intervention will arise for number agreement in SG > PL configurations, because singular DPs simply have no number features at all.

The hierarchy effects in German assumed-identity sentences pose a challenge to this approach because the person-hierarchy effect is accompanied by an analogous number-hierarchy effect. Because Nevins’ (Reference Nevins2011) account locates the absence of NumCC effects in the ontology of number features, it predicts that number-hierarchy effects should be crosslinguistically absent (at least unless one stipulates that the representation of singular differs in German, which seems entirely unmotivated). The German pattern demonstrates that this prediction is too strong, and that number-hierarchy effects do arise under the right circumstances.Footnote 10 We therefore conclude that number features do not differ ontologically from person features, and in particular that singular does not correspond to the absence of a number feature.

To reconcile the absence of NumCC effects with the emergence of number-hierarchy effects in German, we adopt an approach due to Béjar and Rezac (Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003). Their account is based on two crucial assumptions. First, they take the probe in configurations like (18) above to be divided into at least person and number probes, “π0” and “#0,” respectively. Furthermore, these two probes are extrinsically ordered so that π0 will always probe first (see also Preminger Reference Preminger2011), as shown in (24).

Second, they propose that the operation which triggers the pronominal clitic-doubling found in PCC constructions also renders the doubled DP invisible to subsequent operations (in their terms, cliticization leaves an inactive trace). Similar proposals have been put forth by Anagnostopoulou (Reference Anagnostopoulou2003) and Preminger (Reference Preminger2009). As a consequence, in ditransitive constructions, clitic doubling of an indirect object as a result of Agree with π0 removes it as an intervener, clearing the way for subsequent Agree between #0 and the direct object. Since PCC configurations always involve clitic doubling, the indirect object will never cause intervention for number agreement with the direct object, deriving the absence of NumCC effects, as shown in (25).

While Béjar and Rezac (Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003) do not explicitly discuss the absence of number-hierarchy effects in PCC languages, their assumptions that (i) the probing order of π0 and #0 is universal, and (ii) clitic-doubling removes the higher DP as an intervener derive this absence naturally, without appeal to ontological differences between the representation of person and number.

A striking prediction of this account is that number hierarchy effects should emerge if the higher DP is not clitic-doubled as a result of Agree with π0. We suggest that this is precisely what happens in German, which altogether lacks clitic doubling. As a result, Agree between π0 and DP1 in copula constructions does not render DP1 invisible for subsequent Agree by #0. DP1 therefore still causes intervention for Agree between #0 and DP2 if the number hierarchy is violated. Two additional assumptions are crucial to this extension. First, [+pl(ural)] requires licensing in the same way as [+part] does (Rezac Reference Rezac2008, Baker Reference Baker2011, Coon et al. Reference Coon, Keine, Wagner, Lamont and Tetzloff2017). Second, singular is not represented as the absence of a number feature (contra Nevins Reference Nevins2011), but instead as [–pl], i.e., a negative feature value analogous to [–part]. The resulting structure for an illicit 3SG > 3PL configuration in German copular constructions is shown in (26).

Because [–pl] does not require licensing, PL>SG and SG > SG configurations are allowed. PL > PL configurations are well-formed due to Contiguous Agree (22), analogous to combinations of two [+part] DPs.

As a reviewer notes, apparent SG > PL configurations are not always ungrammatical in German copular constructions. The reviewer provides the example of Stanley Kubrick's movie Dr. Strangelove, in which Peter Sellers plays three roles: Captain Mandrake, President Muffley, and Dr. Strangelove. It is possible to describe this role assignment with the sentence in (27). This is initially surprising, as it seems to instantiate a SG > PL configurations, which our account predicts to be illformed.

Coordination seems to play a crucial role here. The sentence in (28) is noticeably degraded.

There are at least two possible explanations for this contrast. First, (27) might plausibly involve clausal coordination in combination with conjunction reduction (Hankamer and Sag Reference Hankamer and Sag1976, Hirsch Reference Hirsch2017, Schein Reference Schein2017). In this case, each conjunct contains a SG > SG configuration and no number-hierarchy violation arises. Second, it is conceivable that plural features that are the result of coordinating singular DPs are not subject to the licensing requirement (i.e., that the licensing requirement only holds for number features that are present on heads), in which case intervention by a [–pl] DP would be harmless. Both options reconcile the grammaticality of (27) with a licensing-based account, and we will not attempt to decide between them here.

3.3 Summary and outstanding questions

In summary, we proposed an account of the presence of number hierarchy effects in German copula constructions as well as the absence of such effects in PCC configurations. Crucial to this account is that there are no deep ontological differences between person and number features. The account also makes testable predictions about the types of hierarchy effects found in different constructions. As noted above, we follow other works in taking hierarchy effects to emerge exactly in configurations in which more than one accessible DP is found in the domain of a single probe. Assuming the universal ordering of articulated probes in which π0 always probes first, we predict number effects to be systematically absent in configurations where the higher DP undergoes clitic-doubling and is thus removed as an intervener for the #0 probe.Footnote 11 This prediction appears to be borne out in PCC constructions, but could also be tested in copula constructions in languages in which subjects are systematically clitic-doubled, for example in certain Romance languages commonly referred to as North Italian Dialects. We leave this as a topic for future work.

Our proposed unification of the hierarchy effects in copular constructions and the PCC raises a number of immediate questions.Footnote 12 We observed that the hierarchy effect in copular constructions displays a significant degree of variability, and that hierarchy-violating configurations are much less degraded than uncontroversially ungrammatical control structures. All else being equal, we might then expect PCC effects to display a similar status. Whether this is the case is not entirely clear to us. The literature on the PCC does report substantial ideolectal variability (Bonet Reference Bonet1991, Reference Bonet, Harley and Phillips1994; Bianchi Reference Bianchi2006; Nevins Reference Nevins2007; Pancheva and Zubizarreta Reference Pancheva and Zubizarreta2018). Furthermore, we are not aware of experimental investigations that would allow us to compare the level of degradation of PCC violations to that of outright agreement violations in a way similar to Experiment 1 above. It is therefore difficult to assess the severity of our copular effects relative to that of PCC effects. We leave a systematic attempt to do so for future work.

Second, a reviewer asks why the PCC seems to be limited to clitics but the German restriction arises in the domain of agreement. While this asymmetry appears striking, it is not entirely clear that it is correct. Basque exhibits PCC effects (e.g., Rezac Reference Rezac2008), and Preminger (Reference Preminger2009) provides an empirical argument that agreement with direct objects in Basque is an instance of agreement, not clitic doubling. Similarly, PCC effects are described in Kiowa by Adger and Harbour (Reference Adger and Harbour2007), a language in which core arguments are cross-referenced via a series of portmanteau forms on the verb. If these cases are taken to be agreement, then it suggests that the PCC is not in fact confined to clitics. Alternatively, if it turns out that all instances of the PCC do involve clitics (see Arregi and Nevins Reference Arregi and Nevins2012 for Basque), it is conceivable that this asymmetry is epiphenomenal. PCC effects have been most frequently described in the domain of double-object constructions (e.g., Anagnostopoulou Reference Anagnostopoulou, Everaert and van Riemsdijk2017). Woolford (Reference Woolford2008) and Nevins (Reference Nevins2011) have raised the possibility that apparent agreement with object is in fact clitic doubling (see also Kramer Reference Kramer2014). If so, then the fact that the PCC conditions only clitics would not reveal anything deep about the PCC as such, but merely reflect the fact that it typically arises with objects, which either rarely or never control true agreement. See also Coon and Keine (Reference Coon and Keine2018) for an account that unifies hierarchy effects in both clitic-doubling and agreement environments.

4. Constraints on predication structures

In this section, we investigate agreement restrictions in predicational and specificational copular clauses that at first glance appear amenable to the hierarchy-based account developed in section 3. We then contrast the distribution of these agreement restrictions to that of the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity sentences. We conclude that the two classes of restrictions emerge from distinct constraints.

In many languages, copula constructions exhibit unusual agreement patterns (see Béjar and Kahnemuyipour Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017 for a recent overview and references). Examples are provided in (29) and (30), which show the agreement options in predicational and specificational copula constructions in German and English. The agreement pattern in English is unsurprising: the copula consistently agrees with the linearly first DP (DP1), but the same is not the case for German. Here the copula must agree with the pronoun du ‘you,’ regardless of its linear position.

An account of the German agreement pattern in (30) must derive two generalizations. First, it must allow agreement with the linearly second (and hence structurally lower) DP (which we will refer to as “DP2”), that is, du ‘you.’ Second, it must rule out agreement with the structurally higher DP das Problem ‘the problem.’

The first objective is fairly straightforward. Due to the word order flexibility in German, which allows both scrambling and DP inversion brought about by V2, agreement with du ‘you’ in (30) follows directly if it is derived from the underlying predication structure in (32). In this structure, das Problem functions as the predicate and du as the subject of the underlying predication, and T0 agrees with the structurally closest DP du (note that this agreement may or may not be accompanied by raising of du to [Spec,TP]; see Béjar and Kahnemuyipour Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017 for discussion). Realization of the resulting structure yields the grammatical version of (29); optional movement of das Problem above du (indicated as “![]() ”) results in the grammatical version of (30). On this analysis, the specificational sentence in (30) derives from the same underlying PredP structure as the predicational sentence in (29), but involves inversion of the two DPs (Heggie Reference Heggie1988, Moro Reference Moro1997, Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005, Heycock Reference Heycock2012, among many others), a process that does not affect verb agreement.

”) results in the grammatical version of (30). On this analysis, the specificational sentence in (30) derives from the same underlying PredP structure as the predicational sentence in (29), but involves inversion of the two DPs (Heggie Reference Heggie1988, Moro Reference Moro1997, Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005, Heycock Reference Heycock2012, among many others), a process that does not affect verb agreement.

The second generalization – that agreement with das Problem is ungrammatical in both (29) and (30) – poses a greater analytical puzzle. This is because it rules out the structure in (32).

Here the base positions of the two DPs in the underlying predication structure are reversed from (31), with du constituting the predicate and das Problem the subject of the predication. Just as in (31), T0 agrees with the structurally closest DP (das Problem in (32)), and du may optionally move over das Problem. In the absence of such movement, (32) corresponds to the ungrammatical version of (29); with such movement, it yields the ungrammatical version of (30). Because both structures are ungrammatical, it is clear that (32) must be ruled out in some way.

In order to rule out PredP structures like that in (32), Heycock (Reference Heycock2012: 230–231) proposes a semantic constraint on predicate structures, according to which the “more intensional” DP must be the complement of the Pred0 head (“F0” in her terminology). In sentences in which one DP is referential (du) and the other denotes a description (das Problem), the description has to originate in the lower position. This requirement is violated in (32). The PredP structure is hence ill-formed, for reasons unrelated to agreement. The PredP structure in (31), by contrast, is licit. Assuming that agreement is invariably established with the DP in [Spec,PredP], it follows that agreement can only be established with du. The specificational sentence in (30) is then derived by V2 inversion of das Problem, a derivationally late process that does not affect the agreement with du. Footnote 13 A related semantically-based constraint that might plausibly rule out the PredP structure in (32) has been proposed in terms of θ-role assignment by Moro (Reference Moro1997: 37–38).Footnote 14

Against the background of our morphosyntactic analysis of the hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences, we note that the impossible structure in (32) involves a hierarchy-violating 3 > 2 configuration. This raises the possibility that our analysis of hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences can be extended to the ungrammaticality of (32)– and hence to the agreement restriction in predicational and specificational sentences in (29)–(30).

We furthermore note that an analogous asymmetry holds for number (also observed by Heycock Reference Heycock2012: 211), as (33)–(34) show.

Here too a configuration must be ruled out in which das Problem ‘the problem’ is generated as the subject of the underlying predication and triggers agreement, followed by movement of deine Eltern ‘your parents’ around it.

Because the illicit PredP structure in (32) involves a hierarchy-violating SG > PL configuration, the account in section 3 correctly excludes it.

These considerations raise the question whether the agreement restrictions in predicational and specificational copular clauses can be altogether assimilated to the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity sentences and, more specifically, to the licensing account developed in section 3. Put differently, we might wonder whether our morphosyntactic account obviates the need for Heycock's (Reference Heycock2012) semantic restriction. In what follows, we evaluate the prospects of this potential extension. We document a number of differences between the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity sentences on the one hand and the agreement restriction in predicational and specificational sentences on the other. We then conclude from these differences that an analytical unification of the two restrictions is empirically untenable.

The first difference between the agreement restriction in predicational and specificational copular clauses on the one hand, and the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity clauses on the other, is based on Moro's (Reference Moro1997: 37) observation that specificational copular constructions are impossible in small clauses. Thus, while it is possible for nonfinite clauses that contain a copula to appear in either the predicational or the specificational form (36), the order in small clauses is strict (37).

Moro (Reference Moro1997) proposes an inversion account of this restriction, according to which the underlying predication structure of (36) and (37) is invariably (38a). The sentence in (36b) is produced by inversion, which in turn requires the presence of the copula, and which is therefore impossible in (37b). In other words, due to the impossibility of inversion in small clauses, (37) reveals – on Moro's (Reference Moro1997) account – that the underlying predication structure cannot be (38b).

If this line of reasoning is on the right track, then a constraint is required that excludes the structure in (38b). It is clear that (38b) (being 3SG > 3SG) violates neither the person hierarchy nor the number hierarchy, so they should not give rise to a licensing failure. Our licensing-based account of assumed-identity sentences therefore does not rule out (38b), suggesting that there is another constraint at work here. More fundamentally, we saw that assumed-identity sentences do not show hierarchy effects in English in the first place (which, we proposed, follows because the two DPs do not bear the same case in English and hence are licensed by distinct functional heads). This again strongly suggests that (38b) must be ruled out by a separate constraint, and Heycock's (Reference Heycock2012) semantic constraint is a plausible candidate.

A second argument for the necessity of a semantic constraint comes from German. The translational equivalent of English small-clause structures in German involves embedding DP2 inside a PP, as in (39). For ease of reference, we will refer to this construction as the “für-construction.”

Importantly, in für-constructions, the two DPs clearly do not agree with the same functional head. The DP den Schüsselfaktor ‘the key factor’ is case-marked by the preposition für ‘for,’ whereas the DP ihn ‘him’ receives case from the verb halte ‘hold’.Footnote 15

Against this background, we make two crucial observations. The first is that our account predicts that hierarchy effects will disappear in assumed-identity versions of für-constructions because the two DPs do not agree with the same head. This is indeed the case, as (40) attests.

The second observation is that predicational and specificational sentences still exhibit an asymmetry in für-constructions that mirrors the restriction in English small clauses in (37), as shown in (41).

In light of the fact that für-constructions do not exhibit hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences and are therefore not subject to the licensing interference (and hence hierarchy effects), we conclude that (41b) must be ruled out by some other constraint. The semantic constraint again fits the bill: In (41b), it is the more extensional DP dich ‘you’ that forms the predicate, violating this constraint.

A third argument for the necessity of a semantic constraint in addition to the morphosyntactic constraint is based on infinitival clauses in German. As in für-constructions, in infinitival clauses the hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences disappear, but the restriction on specificational sentences does not, suggesting that the latter cannot be reduced to the former. The disappearance of hierarchy effects in infinitival assumed-identity clauses is illustrated in (42).Footnote 16

Example (42) involves a 3>1 configurations, but it is nonetheless grammatical. It thus clearly contrasts with similar hierarchy violations such as (5b). We will not attempt to develop an account of this curious fact here. Instead, we merely note that similar amelioration in nonfinite clauses has been observed for morphosyntactic effects in Basque (Laka Reference Laka, Hualde and de Urbina1993, Preminger Reference Preminger2019) and Georgian (Bonet Reference Bonet1991, Béjar and Rezac Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003). See Preminger (Reference Preminger2019) for an analysis compatible with the licensing approach taken here and Coon and Keine (Reference Coon and Keine2018) for a different approach.Footnote 17

Crucially for our purposes, the restriction on specificational sentences does not disappear in infinitival clauses.

Because the licensing-based restriction must not apply to infinitival clauses (given (42)), the ungrammaticality of (43b) cannot be attributed to this restriction. As before, a second constraint is thus required, and the semantic constraint produces the desired result.

The final difference between agreement restrictions in predicational and specificational clauses and the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity clauses concerns the level of degradation. While we have presented evidence that hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences are degraded, their degradation is uncontroversially less severe than analogous violations with specificational copular clauses. Example (44) compares the relative severity of the violation in each case.

While it is generally difficult to use perceived degrees of degradation to draw inferences about the nature of the underlying constraint that is violated, the contrast in (44) is robust enough to be in need of explanation. Clearly, if the degradation of (44a) and (44b) were due to a violation of the same constraint, this contrast would not receive an immediate explanation. A more successful characterization of this contrast becomes available if (44a) instantiates a violation of our morphosyntactic constraint, whereas (44b) involves a violation of the semantic constraint (possibly in addition to a violation of the morphosyntactic constraint). Crucial for this line of explanation is of course that these two constraints coexist.

To summarize the discussion so far, we have provided several arguments that the agreement restriction in predicational and specificational copular clauses cannot be subsumed under the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity sentences in general and to our licensing-based account of these hierarchy effects in particular. A separate constraint is therefore necessary, and we have suggested that Heycock's (Reference Heycock2012) semantic requirement that the more intensional DP be construed as the complement of the underlying PredP structure is a plausible candidate for such a constraint.

At the same time, it is important to emphasize that the opposite line of reduction – reducing the hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences to Heycock's (Reference Heycock2012) semantic constraint – is also unsuccessful. The reason is that hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences do not violate the semantic constraint, but are nonetheless ungrammatical. Consider the by-now familiar example in (45). On the intended interpretation of (45) where a third-party individual is assigned the role of the speaker, the sentence has the underlying predication structure in (46). This structure must therefore be ruled out.

However, the semantic constraint does not exclude the PredP structure in (46), because the more intensional DP is ich ‘I’ (which is not evaluated with respect to the actual world, but rather with respect to the fictional scenario of the play). The DP er ‘he’ is evaluated with respect to the actual world, and it is hence the more extensional DP. The structure in (46) thus obeys the requirement that the more intensional DP must be the complement of Pred0. The fact that (45) is nonetheless ungrammatical therefore cannot be attributed to this requirement. Our licensing account developed in section 3 is therefore necessary in addition to the semantic constraint.

To summarize, we have evaluated the prospects of subsuming the agreement restrictions in predicational and specificational copular clauses to the hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences. We documented a number of clear distributional differences between the two, which indicate that there are at least two constraints at play here. Thus, while we have argued that assumed-identity sentences reveal a novel, licensing-based constraint on predication structures, this constraint coexists with, rather than replaces, existing semantic constraints on such structures.

5. Conclusion and outlook

In this article, we documented and investigated a novel hierarchy effect in assumed-identity copular constructions in German, and we argued that these hierarchy effects provide evidence for a morphosyntactic constraint on predication structures akin to PCC effects. We then developed an account of this constraint in terms of nominal licensing, extending existing treatments of PCC effects to this novel domain. We then assessed the relationship between this licensing constraint and previously-proposed semantic constraints on predication structures by looking at agreement restrictions in predicational and specificational copular clauses. We concluded that the two types of constraints coexist as complementary restrictions on predicational structures.

In closing, we will briefly discuss some of the issues that emerge from this investigation. First, while we have largely limited our discussion to German, the generality of our account leads us to expect similar restrictions in assumed-identity sentences in other languages as well, as long as both DPs are licensed by the same head (minimally, they appear in a case normally associated with verb agreement). In line with this expectation, Bhatia and Bhatt (Reference Bhatia and Bhatt2019) observe person-hierarchy effects in assumed-identity sentences in Hindi-Urdu. Second, we observed one important difference between the hierarchy effect in assumed-identity sentences and that in PCC configurations: while the former show number-hierarchy effects, the latter do not. Building on work by Béjar and Rezac (Reference Béjar, Rezac, Perez-Leroux and Roberge2003), we proposed that this difference results from independently motivated differences with respect to clitic doubling: because clitic doubling of a DP removes this DP as an intervener, a number-hierarchy effect arises only if the language does not have clitic doubling. If this account is on the right track, we expect a connection between these two factors to hold across languages more generally.

Third, hierarchy effects seem to disappear in certain configurations even in German. We already saw one such configuration in (42), where the copular construction is inside a nonfinite clause. Additionally, hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences seem to improve significantly under syncretism. This is especially clear in the past tense and the subjunctive, where the copula exhibits fewer paradigmatic distinctions. For example, the past tense copula does not morphologically distinguish between 1SG and 3SG, and in this case, a 3SG > 1SG configuration is improved, as (47a) shows. The same is true for the subjunctive, as shown in (47b).Footnote 18

Our licensing-based understanding of the hierarchy effect does not lend itself in an obvious way to an explanation of this ameliorating effect of syncretism. Coon and Keine (Reference Coon and Keine2018) propose an alternative account not framed in terms of nominal licensing that extends to (47) more straightforwardly.

Fourth, the status of hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences appears to differ across languages.Footnote 19 While these configurations are ungrammatical in German, they are possible in Eastern Armenian, but require agreement with DP2 (Béjar and Kahnemuyipour Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017), as shown in (48), repeated in part from (12).

Moreover, Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017) show that in Persian, hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences are grammatical with DP1 agreement, as (49) illustrates.Footnote 20

There thus appears to be considerable crosslinguistic variation in the status of hierarchy-violating assumed-identity sentences. As a reviewer notes, Béjar and Kahnemuyipour (Reference Béjar and Kahnemuyipour2017) did not conduct the kind of experimental investigation into the agreement pattern in Eastern Armenian and Persian that we reported for German above, so it is at least conceivable that their status is less disparate than the above data suggest. But assuming that the patterns above are robust, a comprehensive theory of assumed-identity sentences must be flexible enough to accommodate this crosslinguistic variation. It is not clear at present what underlies this difference or whether there is an independent correlate, but the observed variability does raise the question of how the account for German might be parametrized to accommodate the Persian or Armenian pattern.Footnote 21 We leave this, and other questions raised here, as topics for future work.