Introduction

In the spring of 1909, a debate in the German Reichstag about the budget for the army witnessed a peculiar detail: Eduard von Liebert, one of the speakers, had heard through the grapevine that blacks were serving in military bands of the German army, one of them even as a bandmaster: “If this turns out to be true,” he complained, “this would constitute an egregious act. . . . I would like to see a Briton or an American subordinated to a coloured man—this is unthinkable! It would end in rebellion and mutiny.”Footnote 1 The bandmaster that von Liebert had heard about was Gustav Sabac el Cher (1868–1934), the son of the Nubian August Sabac, who was donated to Prince Albert of Prussia during his trip to Egypt in 1843. August later made a career at court as a valet responsible for the silverware, participated in the German wars of unification and married a middle-class German woman. He finally received German citizenship shortly before his death in 1882. Growing up in such a socially protected environment, his son Gustav had early on decided to become a musician and, after a varied musical training at music school, the military, and, finally, the Berlin Academy of Music, he ended up as bandmaster of the First Grenadier Regiment in Königsberg in 1895.Footnote 2

It is probably no coincidence that von Liebert’s complaints about blacks in the German army and Sabac el Cher’s early retirement took place in the same year.Footnote 3 Notwithstanding the fact that other black musicians continued to serve in the German army, Sabac’s departure is a sign of the continual disappearance, if not concealment, of century-long traditions shaping military music in Europe: the reliance on foreign musicians, the adoption of instruments from other parts of the world, and, at least to some extent, the adaptation of musical styles from different cultural traditions. Indeed, after World War I at the latest, the ‘germanisation’ of military music and its dissociation from any foreign cultural influence was complete and military music was perceived as a matter of purely national origin and prestige.

This article investigates the role of the military in the dissemination of music all over the world during the nineteenth century. I argue that this story is first one of European and, more precisely, of German musical expansion. However, precisely because of this basic narrative of diffusion, it is highly important at the same time to bear in mind the cross-cultural fertilisation of European military music that Sabac el Cher represented at the turn of the century. In other words, to balance this one-way story, I will first examine routes rather than roots and deconstruct the musical idiom at least to some extent in showing that Western military music itself, as it began to travel in the nineteenth century, represented a glocal soundscape that was strongly influenced by cross-cultural encounters, primarily with the Ottoman Empire. In the second part, I will counter the all-too-straightforward stories of diffusion by analysing the complex harmonisation of the Western military music idiom in Europe itself. The third part highlights processes of professionalisation, first in Europe and then in the wider world. By using established analytical concepts of adoption and adaptation, I will shed some light on the highly uneven processes of appropriation.Footnote 4 However, in moving beyond the outdated discussion of homogenisation versus hybridisation—it is easy to see evidence of both phenomena in the actions of military musicians—I will, fourth and finally, stress the highly variegated musical missions that military musicians carried out beyond the simple dissemination of march music. I argue that military musicians, thanks to their training as musical all-rounders, were much more versatile musical brokers than missionaries or travelling virtuosos of the so-called classical realm. As such, they had a particularly broad impact on the making of glocal soundscapes worldwide. By the end of the nineteenth century, a global constellation of worldwide military band mobility had matured, and it was nurtured by the urge for national prestige in the age of high imperialism as much as it was by commercial interest at the dawn of local mass entertainment.Footnote 5

Before I start, a clarification about terminology is in order: by military music I include all kinds of music played by soldiers in uniform, that is, members of a national or state army. In this broad sense, military music served various purposes, from the transmission of messages and instructions and the ordering of military operations to ceremonial functions, social integration, and the entertainment of both troops and the nation or community.Footnote 6 This actor-centred definition is not only necessary with regard to the increasing extension of military music to the realm of civil society. It also avoids awkward musical predefinitions. As Didier Francfort has pointed out, there are scant grounds for delineating military music on the basis of aesthetics alone, since its very genre, the march, was never exclusively reserved for military purposes.Footnote 7

With respect to the extant literature on military music, I soon realised that its reputation is rather low. Accordingly, research into the genre stands in similar esteem within academia. Musicology only rarely engages with this historically influential branch of music, while military historians apparently conceive of it as a soft topic, unworthy of study. Hence, at some points, one is constrained to resort to official accounts of former army personnel or, occasionally and much more obscurely, amateur aficionados of military music. Nonetheless, several national histories of military music of individual countries have been indispensable for this first attempt to frame a global history of military musicians and their music in the long nineteenth century.Footnote 8

Of Janissaries and other Turquerie: Military Music before 1800

The sound we usually have in our ear when we think of military music is essentially that of a brass band with some percussion added. This instrumentation, however, was only fully established by the second third of the nineteenth century. Indeed, it took some time before the concept of a musical band, conceived of as “a diverse group of instruments playing some form of concerted music”Footnote 9 gained ground in Europe. While such bands were already common in India and the Middle East as early as the twelfth century, medieval European military music consisted of trumpeters and kettle-drummers on the one hand, and lansquenet pipers and drummers on the other. The former were associated with the princedoms and their cavalry. They got organised as a guild and enjoyed a heightened status at the courts. The latter became a constitutive part of the emerging mercenary armies. Both musical units, however, consisted of only a few players. Many courts featured no more than four trumpeters, and one section of 400 lansquenets usually featured two fifes and drummers only, which, in the German lands, were also called the kleines Feldspiel.Footnote 10

The different tasks of military bands in war and peace, including their dual role in the military and civil realms, were for the first time thrown into sharp relief in Europe during the Ottoman Wars, when the so-called Janissaries time and again threatened the Holy Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Hungary, and the Republic of Venice. From the late middle ages to the early age of enlightenment, the music of these elite corps of the Sultan was “the symbol of pomp and majesty as well as of bellicosity and sheer might.”Footnote 11 The most important instruments of the mehter, as a janissary band was called, included the kettledrum, the trumpet, the zurna (a folk shawm), the bass drum, and cymbals. During battle, the “new soldiers” (that is, the Ottoman Turkish yeniçeriler) played constantly in order to set a march rhythm, to guide and end manoeuvres, and, most of all, to spread fear and terror among the enemy troops. Beyond warfare, the mehter performed for state ceremonies and in religious prayer rituals.Footnote 12

Paradoxically, the Türkengefahr (Turkish threat) so strongly felt and debated in central and Eastern EuropeFootnote 13 went hand in hand with an increasing fascination for every discovery made about the Ottoman culture in the course of the military conflict. In their recent examination of the so-called Turquerie, Alexander Bevilacqua and Helen Pfeifer have argued that “Ottoman culture offered an attractive vocabulary in which new conceptions of leisure, refinement, and the body could be articulated.”Footnote 14 Turquerie at this juncture signifies the fashion to dress, consume, and perform à la turque, a fashion the heyday of which the authors situate between 1650 and 1750. This period, which, in political terms, encompassed war and peacetime with the peace treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 as an important turning point, saw an increasing interest in Ottoman culture at European courts, among the gentry, and within the middle classes, even if representations of Turks as barbarians remained vital all along. While Turquerie so far was rather construed as part of early modern discourses on exoticism and orientalism, Bevilacqua and Pfeifer take the adoption and adaptation of Ottoman culture more seriously, conceiving them as a conscious process of “translations.”Footnote 15

The latter approach is especially convincing with regard to the appropriation of Ottoman military music in this period. First, European courts became so fascinated by the mehter that they increasingly used some variation of this Turkish music for their own official festivities such as weddings, baptisms, and coronations. Beginning in the states of central and north Germany, in opposition to Catholic restoration in the early seventeenth century, European musicians dressed in Ottoman clothes and imitated janissary music in one way or another. The coronation of King Carl VI of Sweden in Stockholm, in 1672, was likely to have been the first occasion of a mehter band composed of Turkish musicians playing at a European court.Footnote 16 Only one year later, janissary musicians were apparently part of Jan Sobieski’s booty from the battle of Khotyn; they were made to play on the occasion of his entrance to Warsaw. Sobieski’s successor on the Polish throne, Saxon elector August der Starke, was one of the princes most obsessed with Turquerie. Indeed, when celebrating the wedding of his son in 1719 in the so-called Saturnalia Saxoniae, the festivities climaxed with a procession of the miners accompanied by a military pageant of no less than 341 soldiers in Turkish uniforms, among them 27 musicians forming a janissary band. Far from being mere exotic padding, this corps performed the traditional function of the military ceremony, above all visualising the might and glory of the prince. However, not only Turkish but also black musicians stood in high demand among European princes. Prussia’s Friedrich Wilhelm I hosted around thirty pipers and drummers in Potsdam who, despite being mainly of African descent, soon received an empire-wide reputation as “janissaries.” In this sense, Gustav Sabac el Cher’s high position in the military band has to be considered a direct legacy of the eighteenth-century craze for Turquerie.Footnote 17

Second, given the high significance of janissary music at courtly festivities spreading all over Europe in the eighteenth century,Footnote 18 it is not surprising that some of its elements became integral parts of European military music. The most obvious Ottoman legacy was the integration of Turkish instruments into the music corps, which emerged as distinct musical units within standing armies. In 1770, most European infantry regiments informally used cymbals, the Turkish crescent, kettledrums, and bass drums. The Austrian military first officially included musicians of these instruments in their army budget around 1800. In the Prussian infantry, percussion instruments became part of the regular instrumentation after 1806.Footnote 19

On first sight, the integration of these percussion instruments was only of minor significance. However, the character of the music changed to such an extent that during the late eighteenth century it became common to classify military music into two categories: Harmoniemusik and Turkish music. These differed not only in terms of instrumentation—the former being limited to oboes, clarinets, horns, trumpets and bassoons, the latter extending to janissary percussion instruments—but also apparently in terms of their function. As the Yearbook of Music for Vienna and Prague of 1796 explained, “The field music is heard on the occasion of the deployment of the main guards and castle guards. The Turkish music is played during the summer months in the evenings in front of the barracks and sometimes in front of the main guards, when the weather is nice.”Footnote 20 In some ways, the latter preceded the so-called Platzkonzert, which would become so popular in the course of the nineteenth century.

Third, following the adoption of Turkish instruments, the use of additional European instruments such as the triangle and the piccolo not only completed the instrumentation of janissary music within the military realm. The combination of all these instruments was at the heart of European composers’ conception of how “Turkish music” should sound. Curiously enough, this mixture of instrumental integration and tonal imitation even left a mark on piano music. While it is common to cite Mozart’s Rondo alla turca in this context, it is little known that some piano makers at the turn of the eighteenth century equipped their instruments with a so-called janissary pedal, which was a mechanism that caused bells, cymbals, and drums to sound. At some point, the technique was so common that some composers explicitly prescribed its use in their pieces.Footnote 21 Despite its limited musical significance and longevity, the janissary pedal is a symbol of the fact that the Turquerie, beyond discourses on exoticism and representations of “the other,” bore a specific influence on material culture as well as on the arts in Europe.

More lasting was the impact of Turquerie on military music. However, the appropriation proceeded so thoroughly that the ethno-cultural connotations of both the musical idiom and its agents, as Sabac’s fate makes evident, were submerged and forgotten with the rise of European imperialism in the long nineteenth century.Footnote 22 Particularly telling in this respect is the further trajectory of military music in the Ottoman Empire itself: when Sultan Mahmud II dissolved the janissary corps in 1826, their instruments were also destroyed. Instead, as part of his army reform, he stipulated the creation of a European-styled military band. Thanks to the Italian military musician Giuseppe Donizetti, the elder brother of opera composer Gaetano, who was hired as a European expert for this job in 1828, janissary music and its instruments returned to the Bosporus, albeit in the European adaptation described above.Footnote 23

Instrumental Expansion and Innovation: Forging the Western Military Band

Alongside the confrontation with and adaptation to janissary music, two other developments in Western European military music have to be mentioned, which were prior to and crucial for its spread around the world: the expansion of the music corps and instrumental innovation. As already noted, in early modern Europe the functions of military music were only gradually extended beyond purely martial purposes. In 1670, the bands of the Prussian infantry still encompassed not more than four players, three of them playing the shawm and one the bassoon. From an aesthetic point of view, their performance was unlikely to have been a pleasant musical experience. Their sound must have been terrible because these musicians were forced to march around thirty steps ahead of the troops. Around a century later, the band still consisted of only eight hautbois. The military bands of other European countries comprised similarly small outfits.Footnote 24

Significant expansion of regular Prussian military bands did not start until the decline of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806. It gained momentum during the Befreiungskriege (German War of Liberation of 1813), when citizens were called to arms and the size of the army increased considerably. However, the spread of military music was not only a matter of quantity. The patriotic sentiment that fuelled the war was also expressed in martial music and the collective singing of German songs. One example of this folk-driven military music was Ludwig van Beethoven’s Marsch für die böhmische Landwehr (March for the Bohemian Militia), which today is better known as the Yorckscher March because it later became a popular march in Prussian General Yorck von Wartenburg’s infantry regiment.Footnote 25

In addition to warfare in the age of Napoleon, the growth of military bands in Prussia and elsewhere in Europe was due to the increasing use of brass instruments such as the trumpet, French horn, and trombone, although the former two in particular still faced mechanical limitations at the turn of the nineteenth century. The intonation of horns was regulated through hand stopping only, while trumpets worked also with slides. In addition, variation of crooks increased the spectrum of keys. A French horn player employed as many as nine when playing orchestral music. This practise was circuitous, time consuming, and far from conducive to satisfactory results.

Against this backdrop, the invention of the valve—conceived as a mechanical device replacing the manual crook change—must be seen as the most important innovation in brass organology of the nineteenth century. The first valve patents were registered in St. Petersburg (as early as 1766) and Ireland (in 1788), though neither had much impact. In contrast, in 1813, the Prussian military musician and horn player Heinrich Stölzel developed the first mechanism to be widely adopted and commercialised. While the so-called Berlin valve of the Prussian military bandmaster Wilhelm Wieprecht influenced the development of new brass instruments in the middle of the century, in the long run it was French inventor François Périnet’s 1839 piston valve that proved the most successful device for brass instruments (except the French horn).Footnote 26

The integration of two, and later three valves together with the keying of instruments allowed for a much more flexible inclusion of brass in the orchestra, which represented a striking pre-condition for the advance of military bands in the European public sphere in the first half of the nineteenth century. To be sure, the technical innovation was initially met with great resistance among brass musicians who did not want to adjust to new instruments. Little by little, however, valved brass made its way into both the military band and the symphonic orchestra. This fostered strong competition among European instrument makers and, consequently, produced a great variety of instruments that to some extent ran counter to transnational standardisation.Footnote 27

At the same time, however, the idea of military music as a genre worth listening to on its own gained ground. Its canonisation started in Russia with the collection of military marches by the Bohemian musician Anton Dörfeldt around 1800. In 1817, King William Frederick III of Prussia ordered a similar collection, the first thirty-six marches of which were a direct adoption from the Russian one. March No. 37, the first piece chosen by the court, was Beethoven’s Yorckscher March.Footnote 28 This musical and aesthetical valorisation led to the composition of new marches as well as the arrangement of older ones for the expanded and technically improved military band. Thus, to cut a long story short, the military band with the musical idiom we have in mind today when thinking about military music did not become a full-fledged genre until the second third of the nineteenth century. As I will argue in the next section, military musicians from the German lands were of paramount importance for the dissemination of this musical idiom and the professionalisation of military music in Europe as well as in the wider world.

German Military Musicians abroad: From European to Global Professionalisation

In the summer of 1867, the world exhibition at Paris witnessed a spectacle the world had not seen before: military bands from nine different countries competed against each other before a music jury and a public audience of some ten thousand. Half of the participating states came from German-speaking lands,Footnote 29 including Prussia, Austria, Baden, and Bavaria. Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, Russia, and the host, France, also took part in the competition. Curiously, however, the event turned out to be a family meeting of German military bandmasters—except for the Spanish and the French bands, all orchestras were led by conductors from the German lands.Footnote 30

While the competition, including its results and significance, will be scrutinised more thoroughly in the next section, the focus here is on the striking dominance of German military musicians at this event, which did not come out of the blue. Rather, it points to the high reputation Germans had gained in this field of musical activity during the nineteenth century in Europe and foreshadows their global vocation towards the end of it. What is more, by studying the nationalities of the participants, it becomes clear that the 1867 competition was a European, or, more precisely, a purely continental contest, leaving out the British Empire, whose presence in other respects was strongly felt at the exhibition.Footnote 31

Apparently, it was the British government that had prohibited the participation of any British bands.Footnote 32 While the reasons for this decision are unknown, there is some evidence for the argument that the British military music was in the midst of a process of professionalisation that did not yet allow it to show up at such a prestigious event. Yet only five years later, following an invitation of Patrick Gilmore, the American doyen of military music, the British Grenadier Guards Band, led by Daniel Godfrey, performed at the Boston World’s Peace Jubilee and International Music Festival in 1872 and subsequently at the Chicago World Fair.Footnote 33

There is no doubt that the event on the other side of the Atlantic, so enthusiastically received by the public at both ends, constituted a cornerstone in the long process of British emancipation from German musicians’ tuition. Parallel to civil musical life, where—particularly in London—musicians of German descent abounded since the middle of the eighteenth century,Footnote 34 many military bands had a German bandmaster. One of the first was the oboe player Friedrich Wilhelm Herschel from Hanover, a son of a military musician who escaped to London after French occupation in 1757. While Herschel later became famous for his research in the field of astronomy, one of his earlier occupations included the position of bandmaster of the Durham Militia.Footnote 35 To give but one more example, the history of the band of the renowned Coldstream Guards began in 1785 with a delegation of twelve musicians from Hanover under the leadership of Music Major Christopher Eley. It was not until 1825 that the list of Germans was interrupted for the first time by an English bandmaster, Charles Godfrey, who had been a bassoon player for around ten years in the band. He was to establish the renowned Godfrey dynasty of military musicians in England.Footnote 36

In the course of the nineteenth century, the widespread presence of German and, to a lesser extent, Italian bandmasters and bandsmen in the British army became an issue for at least three reasons: first, foreigners as they were, these musicians remained civilians at heart and were not very interested in military obedience, which time and again led to conflict among the troops.Footnote 37 Second, and consequently, these bandmasters were often corrupt and colluded with the music business, especially instrument makers and publishers such as Boosey, who also acted as job intermediaries between regimental officers and foreign musicians. Third, this kind of market-based recruitment stood against any serious effort of professionalisation. The lack of professional organisation within British military music circles became apparent on the occasion of a military parade honouring the Queen’s birthday on May 24, 1854, in Scutari, Turkey, which brought together around 16,000 British and allied troops who were serving in the Crimean War against Russia. Echoing the general organisational muddle of the British army, some reports have it that the military bands played “God save the Queen” not only in different arrangements, but also in different keys, resulting in an embarrassing cacophony.Footnote 38

All these factors triggered an initiative to reform, the most striking of which was the foundation of the Kneller Hall Military School of Music in 1857. Thanks to the insistence of George, HRH the Duke of Cambridge, who had been an earwitness of the Scutari incident and was appointed commander in chief of the British army after his return from Crimea, the professionalisation of the British army proceeded alongside that of its military music.Footnote 39 Kneller Hall, despite its orientation toward military music and military musicians, became the most renowned music school in the United Kingdom for decades and was the first to receive government funding. The syllabus encompassed a two-year study of two instruments from different families, conducting, and courses in music theory, including harmony, counterpoint, arranging, and music history. Pupils were prompted to undertake regular visits to concerts and operas to train their musical judgment, and the military rank of bandmasters and their advancement closely depended on their Kneller Hall examinations. However, while in the long run foreign bandmasters were replaced and British military music successfully standardised, leading to the conferral of the institution, in 1887, as the Royal Military School of Music, during its first fifteen years it was a largely German establishment with predominantly German civilian musicians, including its first two directors, Henry Schallehn and Carl Mandel.Footnote 40

A brief glance at Russia shows roughly the same picture: Military musicians from the German lands dominated the scene even more than in the United Kingdom. On the one hand, this had to do with the German imprint of the Russian Empire by the invitation of Peter the Great and his successors in general. On the other hand, the perpetuation of serfdom until well into the nineteenth century made the mass recruitment of foreign professionals a necessity. Until the abolition of serfdom in 1861, most native musicians were serfs or former serfs, a fact that kept this occupation from improving its economic status and social prestige.Footnote 41

Among the many German military musicians serving the Russian Empire, the Bohemian clarinettist Anton Dörfeldt, mentioned above, takes most credit for the renovation of imperial military music. Arriving in St. Petersburg in 1802, he had to start virtually from scratch, since during his short reign (1796–1801), Paul I had forbidden any musical activity beyond the military code, cutting the bands down to only five wind players.Footnote 42 The mission outlined by Paul’s successor, Alexander I, was to put in order and educate all music corps of the guards in the capital and to found a school for military musicians under Dörfeldt’s direction. Thanks to his leadership, the adoption of the janissary section as well as of valved brass instruments to some extent resulted in the standardisation of instrumentation of Russian military music.Footnote 43

However, brokerage of musical knowledge via military paths was not a one-way street. Besides teaching, Dörfeldt composed and arranged innumerable marches for his bands and he became the father of the Imperial Collection of Russian Army Marches, which was the model for the Prussian one. Likewise, the Russian military tradition of singing, which despite all Western influences continued throughout the nineteenth century had some repercussions in the German lands. The melody of the most popular Russian song at the end of the eighteenth century, composed by Dimitri Bortnjanskij, found its way into the most important Prussian military ceremony, the Großer Zapfenstreich, which prevails still today. Conversely, thanks to the continued German presence, Russian soldiers became familiar with European opera repertoire. In 1875, Wilhelm Wurm, a trumpet virtuoso of German origin and Dörfeldt’s successor as bandmaster of the guards in the third generation, assembled around 500 court and regimental singers, 700 military musicians, and 40 drummers for an outdoor performance. Obviously emulating the “monster concert” style established by Wilhelm Wieprecht in Berlin in the middle of the century, Wurm conducted, inter alia, Hector Berlioz’s overture to Les Francs-juges and a chorus from Richard Wagner’s opera Lohengrin.Footnote 44

Altogether, one should neither overestimate the German imprint on the professionalisation of European military music in the nineteenth century nor its degree of standardisation. Not every European country was so dependent on musicians from the German lands as Great Britain and Russia. Whereas Italy was somewhat prone to Austrian influences between 1815 and 1848, France, despite all material and personal exchange, rather found her own way to the modern military band.Footnote 45 Moreover, great variation with regard to band size, pitch, and instrumentation, including the use of distinct instrument brands, continued throughout the nineteenth century, as the Prussian military bandmaster August Kalkbrenner pointed out in his comparative study, Die Organisation der Militärmusikchöre aller Länder (Organisation of military corps of all countries), published in 1884. For a start, it took a lot of effort to standardise these elements at the national level.Footnote 46

Nonetheless, Kalkbrenner also identified a common thread in the European military music band: its “cultural mission for a wider audience”—and, one may add, not only at home, but also abroad. From the last third of the nineteenth century onwards, the Europeanisation of military music, so overwhelmingly promoted by military musicians from the German lands, left its core area and took a more global shape. Colonial occupation in general and the expansion of the European empires, especially the British and the French, were critical to this development.Footnote 47 However, outside these colonial realms, more often than not it was German military musicians who acted as cultural brokers and got involved in modernising the military and its music in such diverse countries as Japan, Chile, Turkey, and Hawaii. Strongly conditioned by political as well as socio-cultural circumstances on the spot, each of these processes led to a distinct transformation of the respective local musical life.

When the German military bandmaster Max Kühne arrived with his band in Santiago de Chile in 1910 during the visit of Prince Heinrich of Prussia, brother of Wilhelm II and inspector general of the Imperial Navy, the journey through the crowds to the hotel was accompanied by military marches very familiar to the officer. Later, the parade of the Chilean military took place, headed by the German military instructor Emil Körner. According to Kühne, it was “a magnificent spectacle. The troop units paraded in pretty much the same uniforms as our old German ones with spiked helmet.”Footnote 48 Even the prince was strongly impressed by the performance of the Chilean military. Later on, he wrote to his brother that he would treasure the memory of these defiling Chilean troops for a long time. Heinrich took some pride that in faraway South America, “our drill so often scoffed at by so many has become common in a nation . . . that, seriously aspiring to make the army a means of national mass education, absorbed the spirit of the German-Prussian army organisation.”Footnote 49

The global professionalisation of military music at the end of the nineteenth century and beyond was often a by-product of the larger issue of army modernisation of independent nation states in the making, as this episode reveals.Footnote 50 The Prussian military, especially after the wars of unification, enjoyed a high reputation outside Europe and was considered a role model for this process. Indeed, in the 1880s, when Chile’s legation in Berlin received the order to ask the German government for a military mission, Jacob Meckel, the military expert most in demand, declined because he preferred to accept a Japanese invitation to modernise the army in the Far East.Footnote 51 From 1885 onwards, Emil Körner, who was chosen instead, led the so-called Prussian reform in the Andean state, subsequently reaching the position of supreme commander of the army in 1901, the highest possible post. He adopted Chilean citizenship and ultimately managed to preside over a Chilean army that in the minutest details followed the Prussian paradigm.Footnote 52

Similar reform processes, albeit with slight variations, occurred in Japan and Turkey. Beginning in 1868, the so-called Meiji Restoration triggered a process of deliberate, state-led, westernisation of Japanese society to an extent unprecedented in history. As in Chile, modernisation of the army included the establishment of military music that roughly followed the Western role model. In contrast to Chile (and Turkey), however, apart from the particularly efficient German Major Jacob Meckel, the impact of military brokers from other countries, especially France, could also be felt. In Turkey, where military reform according to the Prussian model had already been introduced in 1882, it apparently required some kind of soft power on behalf of the German Emperor vis-à-vis the Ottoman sultan, before the latter agreed to include the realm of music in the reforms of the army.Footnote 53

A lasting imprint of German military musicians in countries in which German-inspired army modernisation did not take place was rather rare. A notable exception was Heinrich Berger. Born in 1844 in Berlin and raised by a Stadtmusiker family in Coswig, Berger became a military musician in Berlin in 1862 and participated at the Paris competition five years later. At the request of the Hawaiian King Kamehameha V, in June 1872 the German War Department dispatched Berger to the Pacific island chain to act as bandmaster for the Royal Hawaiian Band for four years. After a short return to Imperial Germany in 1876, he left the army, decided to settle on the Pacific island and adopted Hawaiian citizenship in 1879. Retiring in 1915, he remained musically active in Hawaii as well as in the United States. He died only in October 1929, aged 85. Until today, his reputation oscillates between “the Father of Hawaiian music” and the “Grand Old Man of Music in Hawaii.”Footnote 54

In general, the longer German musicians were active overseas and the more flexible their attitude was towards the elites, the more recognition they received in these countries. Probably no other German cultural broker in uniform gained as much fame overseas as did Berger in Hawaii. Throughout the changing political status of Hawaii from kingdom to republic to U.S. territory, he remained in charge of the same band. Like Berger, both Franz Eckert and Paul Lange Bey, the most influential German musicians in Japan and Turkey, stayed there far beyond their mission, and, including Eckert’s time in Korea, both lived for more than thirty years in their host countries. As with Berger, Eckert and Lange Bey were rather successful in adapting to new political circumstances. After the takeover of the Young Turks in 1908/09, Lange fell out of favour for only a short time and returned with even greater success to his position as bandmaster of the sultan’s band. And Eckert succeeded in manoeuvring his Korean military band through the troubles following the Japanese annexation in 1907.Footnote 55

The scope of action of these three cultural brokers transcended by far the realm of military music proper and to influence civilian musical life. Unlike his colleagues, Lange was not even trained in military music. Educated as a church musician, he went to Constantinople on his own initiative, his first job being as vocal teacher at the German school and organist at the German embassy. Indeed, Lange became one of the most renowned figures in the (Western) musical life of Constantinople, where he founded a symphony orchestra and, with meagre success, a conservatory. Only after the intervention of Wilhelm II did Lange take an interest in the reform of the Ottoman military music. His civilian background points to the fluidity between these two musical worlds, or even the lack of distinction between them, at the end of the nineteenth century.Footnote 56 A military musician by education, Eckert was sent out by the German Navy Department in 1879 at the request of the Japanese government, in order to become bandmaster of the Japanese Navy Band, which had been founded by his British predecessor, John William Fenton. Later, he taught music theory and ensemble play at the first Japanese music school and became chief of the Gagaku, the Japanese court musicians.Footnote 57 The musicians Berger had to train in his Royal Hawaiian Band were not soldiers but native Hawaiian musicians, who received a salary to be paid from the military budget. This hybrid civilian-military situation became most obvious when in 1893, Queen Lili’uokalani was overthrown, and subsequent U.S. governance virtually transformed the band into an institution funded by state, county, and later municipal authorities. In fact, only in 1911 did Berger meet his “old comrades” again, when he began to teach U.S. military bands stationed on the islands.Footnote 58

Beyond their main task of music teaching and playing, all three men composed musical works that more or less adapted to local music genres and styles and thus contributed to the making of glocal soundscapes. Eckert is often credited as composer of the Japanese national anthem. However, the genealogy of Kimi ga Yo is more complex, since Eckert’s composition, which is still in use today, draws on an earlier version by Fenton as well as on a theme by the Japanese composer Hiromori Hayashi or his pupil Oku Yoshiisa. In fact, Eckert’s main achievement was to add Western harmony and instrumentation. In many other compositions for the Japanese navy band, Eckert also used material from “traditional” Japanese music.Footnote 59 Lange, apparently out of gratitude for having been pardoned, composed the march “Yachassin Vatan” (Long live Young Turkey) for the Young Turks. This became his most famous musical work, not the least because of his incorporation of the freedom song of the Young Turks in the trio of the march.Footnote 60 Berger’s early works and arrangements, even when given a Hawaiian name, followed mainly European (light) classical traditions. Gradually, however, the integration of vocals according to the Hawaiian mele tradition became essential for this compositional oeuvre. It is interesting to note that the share of music labelled “Hawaiian” in programmes grew in proportion to the increasing loss of political autonomy of the islands. Berger played a crucial role in the attempt to bolster Hawaiian music culture and to produce soundscapes that served desires for locality and authenticity. Even today he is credited with having composed Hawai’i’s anthem and with transcribing Hawaiian melodies that previously had only been passed on orally.Footnote 61

The strongest adoption of European musical works took place in Chile—at least with respect to the repertoire of army bands. The Chilean historian Alberto Díaz Araya identified the marches “Ich hatt’ einen Kameraden,” the “Bayrischer Defiliermarsch,” and excerpts from The Nibelungen by Richard Wagner among others. He concludes that “these melodies, and even more so the uniforms, spiked helmets and armament, symbolised an institution that intended to imitate the German military prototype, making its soldiers the ‘Prussians of South America’.”Footnote 62 However, despite this precise adoption of the German model in musical terms, there were unintended consequences that were equally significant, in Díaz Araya’s eyes. He argues that in the course of administrative and military reform, many indigenous people from the Northern Andean regions enrolled as military musicians. Learning brass instruments unknown before in local musical practice, these conscripts were crucial for the spread of brass band music on the occasion of festivities in the Andes. Trumpets, cornets, and trombones replaced or were added to older traditional wind instruments, especially different types of flutes and pan flutes, and thus contributed in some way to bridging the gap between indigenous and non-indigenous cultures. Similar processes occurred in Japan, where, inspired by military music, domestic civilian bands performed Japanese songs on European instruments. Footnote 63

In a nutshell, the global professionalisation of military music left its mark beyond the barracks yard and parade ground. Transcending the civilian-military divide, it became a constituent feature of commercial musical life all over the world, as I will argue in the following section.

Valorisation, Competition, Commercialisation: Why Military Music Mattered

Going back to the Paris exhibition of 1867, the military music competition not only reflected German domination in this field, but also pointed to the high reputation and the degree of valorisation military music had reached. A glance at the jury of the competition reveals some celebrities of the (highbrow) European music scene: among the twenty members from all the participating countries were the German conductor Hans von Bülow, the Austrian critic Eduard Hanslick, and the French composers Ernest Boulanger and Leo Delibes. The aged Giacomo Rossini was designated to act as honorary president of the event, though he declined due to illness. Likewise, only court mourning prevented Napoleon III from participating. Nonetheless, he personally welcomed every band the day before the competition. Finally, more than 25,000 listeners followed the performances of the ten military bands, the smallest of which included 51 players, and the largest 86. Each band had to perform two pieces, one of them Carl Maria von Weber’s Oberon overture, the other one of their own choice. Tellingly, however, all bands chose works from renowned contemporary composers as their second piece. Hence, the audience listened to arrangements from Meyerbeer’s Le prophète (Prussia), Wagner’s Lohengrin (Bavaria and the Paris Guards), and Glinka’s A Life for the Tsar (Russia). Even the highly virtuosic Carnival in Venice by Berlioz was performed by the French Imperial Guards.Footnote 64

The artistic ambition of the military musicians was perfectly in key with the aesthetic estimation of the jury and the audience, as many newspaper reviews and contemporary reports about the event show. Even if he complained about the hard work and the fact that the constant repetition of the Oberon overture had spoiled for him his favourite piece for years, Hanslick was highly impressed by the achievements of the Prussian and, even more so, of the Austrian band: “The Prussians received an applause seemingly unsurpassable; but after the music of the Austrians, the hall boomed like a hurricane.” Also, the Paris Guards played “as precisely as clockwork.”Footnote 65 Indeed, many reviews approved the decision of the jury to award these three bands the first prize.

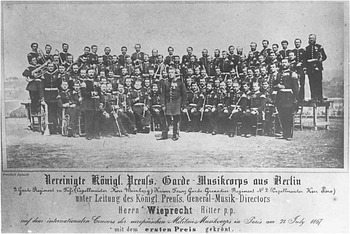

Whom to consider primus inter pares, was of course highly contested. Hanslick saw his Austrians on top, while Wilhelm Wieprecht, the conductor of the victorious Prussians, concealed the fact that the first prize was shared with others altogether (see also figure 1).Footnote 66 In contrast, a French commentator explained that the three first prizes had to be understood as pure courtesy; the common opinion was by far in favour of the Imperial Guards. Others, in turn, complained that the latter did not constitute a military band but was mainly composed of virtuoso players from Paris theatres. Thus, the competition bore witness to the artistic ambitions of European military music as much as it reflected the strong national rivalries finding expression in this specific cultural field.Footnote 67

Figure 1 Picture taken from BArch, MSG 206-14.

National competition was also at stake at the Boston World’s Peace Jubilee that Patrick Gilmore organised in June 1872. To this end, a coliseum for 50,000 people was planned. Backed by the U.S. government, Gilmore managed to entice to Boston the best military bands from European countries large and small, but his great coup was to engage the famous waltz king, Johann Strauss II, for the entire two weeks of the festival. His performance became a daily feature of the concerts, which were nationally framed as American, English, German, and French, and so on. According to the Boston Globe, however, Germany’s Kaiser Franz Grenadier Regiment, under the leadership of Heinrich Saro, apparently stole the show from Strauss. It seems like these military bands themselves represented a great attraction to the American audience. In any case, they and not the great European symphony orchestras were the pioneers of transatlantic cultural diplomacy in the musical field. Their role as ambassadors of peace, celebrating the harmony of the nations, reveals the high esteem and important civic functions that military bands played within nineteenth-century Western society.Footnote 68

In contrast to the Paris exhibition, the Boston Jubilee was of a more cooperative character, not the least because of the absence of any official contest. What is more, both events stood for the increasing state-based mobility of military bands all over the world, which was particularly characteristic of the age of high-imperialism between 1880 and the outbreak of World War I. The missions of marine bands, as well as the formation of bands in the colonies themselves, led to a great many encounters of military bands from different countries.Footnote 69 Again, these oscillated between competition and cooperation. For example, the aforementioned bandmaster Max Kühne had played in the German colonies of Togo, Cameroon, and German-South-West-Africa as well as in the German expatriate community in Blumenau, Brazil, before he witnessed the parade in Santiago de Chile in the spring of 1914. This trip, on the SMS König Albert, was as much a test run of the new battleship as it was a demonstration of power in the context of the Anglo-German naval arms race, which was also shaped by such cultural manifestations.Footnote 70

Willy Höhne, in contrast, served as military music instructor on the spot. Between 1903 and 1909, he formed a band from indigenous musicians in the German colony of Cameroon. Highly ambitious, he taught them how to read music (see figure 2) as well as harmony and brass technique.

Figure 2 Willy Höhne and the Cameroon military band, around 1907. Picture taken from Dornseif, Schwarzweisse Militärmusik.

His efforts and the talent of the musicians proved so successful that Cameroon’s Governor Jesko von Puttkamer began to take the band along on his journeys. Subsequently, the band visited Togo and the then-Spanish island of Fernando Pó (today Bioko) in the Gulf of Guinea on the occasion of the wedding of King Alphonso III. Most interesting, according to Höhne, was the encounter with an indigenous military band in what was then British Old Calabar, today Nigeria. Commenting on how his band was received when it played upon its arrival, Höhne stated that “when the sounds of The Geisha, the favourite English operetta, sounded across the vast piers, the Britons, usually so cool, completely lost their calm.” The bandmaster considered it a veritable demonstration “that the Germans as well, if not first and foremost, are capable of acting as cultural pioneers and of standing their ground.”Footnote 71

Such struggles for national prestige and distinction were everyday practice in the age of high imperialism. Nonetheless, in the Far East in the early 1900s, following the Boxer rebellion, the international administration of Tientsin brought together military musicians from Russia, Germany, France, and Great Britain (see figure 3).Footnote 72

Figure 3 Military bands meeting at Tientsin, around 1905. The Germans wear epaulettes and hats with white bands. The British wear grey uniforms and dark hats. The Russians wear dark uniforms and big hats. The French wear grey uniforms and hats with white bands. Picture taken from BArch, MSG 206-13.

These cooperative musical encounters even extended to local military bands. A joint concert of the German Third Sea Battalion and a Chinese military band took place before the international legation in Peking in 1910 (figure 4).

Figure 4 Picture taken from BArch, MSG 206-13.

Thus, the increasing mobility of military musicians around the turn of the century served various means, from cultural brokering and musical professionalisation to strengthening its own national prestige and at the same time demonstrating goodwill vis-à-vis other colonial powers.

Finally, military band tours became a commercial venture, blurring the edge of the public and the private, of state affairs and civil society, and of high-brow and low-brow music consumption. World exhibitions and great music festivals such as the Boston Jubilee were as instrumental to the rise of the commercial military band concert as was the emergence of the brass band movement in the middle of the century. Driven largely by ex-military bandmasters, it proved to be particularly influential in Great Britain and in the U.S.Footnote 73

While at the end of the nineteenth century, the most famous military bandmasters, or more precisely bandmaster families, from the German lands were mainly of Austro-Hungarian descent—think of Franz Lehár or Karl Komzák juniorFootnote 74 —no one capitalised more on this global trend than the American march king, John Philip Sousa. Born in 1854 in Washington to a Franconian mother and a Portuguese father, the “Berlioz of the Military Band,” as he was known, was appointed bandmaster of the Marine Band at the age of twenty-five. Remarkably, he was the first American-born musician to hold this post. After twelve years of service, the trained violinist set up his own band in 1892 and, thanks to his own composing genius, conquered the garden pavilions and concert stages at home and abroad, with four European tours between 1900 and 1905 and one world tour in 1910–11. Sousa’s band is said to have travelled more than a million miles and is credited with being the best-known musical formation in the world before the establishment of radio. The band operated on a purely commercial basis and eventually made its leader a millionaire. Accordingly, Sousa’s self-description was that of a “Salesman of Americanism, globetrotter, and musician.”Footnote 75

While Sousa successively led a military and afterwards a civil band dressed in uniform, as did the German-Hawaiian bandmaster Heinrich Berger,Footnote 76 the commercial performance of military bands was generally a common feature on European as well as overseas stages. In the German Empire, military bands were regularly put on leave for guest performances in the Benelux, Russia, and, especially, Switzerland, where some German regimental bands stood under contract for as long as an entire year.Footnote 77 Inland, military musicians represented the hardest competitors for civilians, causing the German Music Union to address a cry-for-help in 1904. Read against the grain, the pamphlet testifies to the omnipresence of military bands in German musical life.Footnote 78 Beyond Europe, the conditions were similarly competitive. The diary of Marie Stütz, a member of a travelling women’s orchestra in the last third of the nineteenth century, is a case in point. Whether in Scutari or in Cairo, in India or in Bulgaria, wherever the orchestra arrived, there were competing military bands right around the corner. Conversely, it could also happen that travelling musicians were put under contract of a military regiment—as occurred with musicians from Salzgitter who temporarily served with the Indian army.Footnote 79 Oscillating between perdition and prospect, civilian musicians’ perceptions of their uniformed colleagues at home and abroad are important evidence of the fact that military music mattered, not only as a means of cultural diplomacy, but also in the commercial realm.

Conclusion

This article has highlighted the role of military musicians and their music in the making of soundscapes in Europe and beyond during the nineteenth-century. The rise of military music as a social and musical formation was the result of army reorganisation, instrumental innovation, aesthetic developments, and musical professionalisation. Military musicians on the move were more or less instrumental in all of these processes. Cultural brokers by accident or by design, they disseminated Western musical knowledge from instrument techniques and reading skills to harmony and repertoire acquaintance. More often than not, these brokers came from the German lands, combining two properties that had become signs of “Germanness” in the course of the nineteenth century: musicality and drill.Footnote 80 Not least, their mediation did not confine itself to the army proper but extended to civil society. If it is true that the military became the “School of the Nation” in many parts of the world after 1850, it is no exaggeration to maintain that this school, to a considerable extent also affected the soundscapes of these nations in the making. Due to the length of their missions and their proximity to elites and because of their broad repertory covering every nineteenth-century genre imaginable, military musicians often had a much greater impact on the overall music scene of their host countries than short-term travelling musicians or missionaries, who rather targeted the ordinary population.

That said, Sabac el Cher’s career in Imperial Germany, as well as the fate of Ottoman elements in Western military music, point in several ways to the limits of cultural brokers’ agency, or at least their legacy. They are also a sign of the societal desire for transcultural agnotology and national authenticity. As much as Sabac did not fit the German racist concept of German military musicians after 1900, despite a century-long tradition of black army musicians, Chilean village bands probably did not perceive themselves as influenced by the Prussian military music tradition, either. And while Turkish influence was forgotten even though it could have been so easily audibly recognised, very few are aware that it was a German bandmaster from a provincial Saxon town who arranged “Aloha’Oe”—perhaps the Hawaiian song par excellence for brass band—and was responsible for its dissemination beyond the Pacific islands.Footnote 81 In the end, military musicians, even if they spent a great deal of time in their host countries, were not only reliant on a favourable local environment. More significant, they quickly lost control over the object they were brokering: the art and style of music. Consequently, the cultural brokers in uniform of the nineteenth century not only fostered the diffusion of Western military music but, more important, they incited more general processes of musical change and exchange.