The silence of Italian Renaissance thinkers on matters of commerce has long been a locus communis in the history of ideas. A society grounded in international trade, which produced such material magnificence, and spoke so precociously about politics, it is widely believed, had curiously little or nothing to say about political economy. This notion is already fully and elegantly formed in David Hume's essay “Of Civil Liberty” (originally “Of Liberty and Despotism”). “Trade was never esteemed an affair of state till the last century; and there scarcely is any ancient writer on politics, who has made mention of it,” he writes, adding that “even the Italians have kept a profound silence with regard to it.” In this way, the late Istvan Hont argued, Hume “bracketed the Renaissance with classical antiquity” as “pre-economic and hence premodern.”Footnote 1 Perhaps no Renaissance figure is more emblematic here than Niccolò Machiavelli, whose admission that “because Fortune has determined that, not knowing how to talk either about the silk business or the wool business or about profits and losses, I must talk about politics” has been read as an uncompromising (if ironically formulated) mission statement.Footnote 2 Transplanted from Italian to ultramontane soil, Machiavelli's professed inability to speak of economic matters metaphorically bloomed into nothing less than a dichotomy, so famously explored by J. G. A. Pocock, between wealth and civic virtue, the latter understood as an intellectual inheritance from Italian and especially Florentine (and Machiavellian) political thought. Yet recent work has argued that Machiavelli was indeed an economic (or at least fiscal) thinker and, more broadly, that “commercial interests, attitudes, and priorities were thoroughly accommodated by Renaissance republicanism” in Italy.Footnote 3

Hume, himself committed not to a wealth-virtue dichotomy but to showing that wealth and even luxury were compatible with public virtue, also looked to Florence. Indeed, Emma Rothschild has persuasively argued that Hume, in his essay “Of Refinement in the Arts,” employed a “Florentine model” of political economy. The quintessential “opulent republic,” Florence showed how wealth and virtue could coexist, and its model, Rothschild writes, “lay at the centre of Enlightenment optimism about the progress of commerce and industry.”Footnote 4 Hume knew that “the Florentine democracy applied itself entirely to commerce” and his argument is telling: “The same age, which produces great philosophers and politicians, renowned generals and poets,” he argues, “usually abounds with skillful weavers, and ship-carpenters. We cannot reasonably expect, that a piece of woolen cloth will be wrought to perfection in a nation, which is ignorant of astronomy, or where ethics are neglected.”Footnote 5 For Hume, the Renaissance Italians were good at doing political economy but bad at thinking it, bad at teaching it, leaving behind the evidence of riches and a “profound silence” about their role in politics and, even more so, the role of politics in acquiring them. But was Hume right about the silence of the Italians? In this essay we explore the politics (or perhaps the geopolitics) of the transformation of raw wool into finished cloth, using the case of Medici entrepreneurs in the sixteenth century. In light of this, we argue that context in the history of political-economic thought must mean not only the context of other books and ideas but also of business practices and—glancing at an even richer possible future of the field—that the history of political economy might well be incomplete without business history.Footnote 6 If we wish to know what Italian Renaissance thinkers had to say about politics, we ourselves cannot be ignorant, pace Machiavelli, of the “wool business” and of “profits and losses.” If we wish to hear voices where Hume heard nothing, we must attend to the “skillful weavers” and the perfection of pieces of “woolen cloth.”

When Voltaire famously opined that France, overfed with narrative and moral fantasies, “around 1750 . . . finally turned to reasoning about grain,” he captured with his usual crispness nothing less than the start of an “economic turn” in European Enlightenment thought, a turn manifested in step with the emergence of political economy as an increasingly distinct and increasingly indispensable science of human affairs at the very heart of which lay the literal (especially in France) and metaphorical problem of grain.Footnote 7 The coming decades witnessed the appearance in France of physiocracy (etymologically the “rule of nature”), an ideology associated with the thought of the économistes gathered around the court physician François Quesnay, which celebrated agriculture and devalued the urban world and saw land as a nation's sole source of wealth and clearly superior to “unnatural” and even “sterile” industry. Even though applied physiocracy led disastrously to food shortages, riots, deaths, and political destabilization, its influence was long lived, leaving an indelible imprint on classical economics from its inception.Footnote 8 But the physiocrats were not, of course, the first to weigh the relative merits of agriculture and industry in economic terms. This matter was already in the sixteenth century (if not much earlier) a quintessential problem of political economy avant la lettre. In his internationally best-selling On the Causes of the Greatness of Cities (1588), Giovanni Botero devoted considerable attention to precisely the question of “which is of greater value for improving a place and increasing its population: the fertility of its soil, or the industry of its people?” His answer, the opening of which is quoted at length below, was clear:

The answer is undoubtedly industry, first of all because the things made by skilled human hands are far more numerous and costly than those produced by nature, for nature furnishes the material and the subject, but human skill and cleverness impart to them their inexpressible variety of forms. Wool is a crude, simple product of nature, but how beautiful, manifold and varied are the things that human skill creates from it? How many and how great are the profits that result from the industry of those who card it, give it its warp and its weft, weave it, dye it, cut it, and sew it, and shape it [la scardassa, l'ordisce, la trama, la tesse, la tinge, la taglia, e la cuce, e la forma] in a thousand ways and transport it from one place to another?Footnote 9

Just as Hume more than a century and a half later unmistakably pointed to Venice and Florence, respectively, by invoking shipbuilders and silk and skilled weavers and wool, for Botero's audience the production of wool was tangibly linked to Florence, the wool city par excellence, to its greatness (grandezza), and to industria itself, understood both as a virtue, for men and women as for cities, and as an economic process of adding variety and value to nature's raw materials. The Italian cities of Florence, Genoa, and Venice “of whose grandezza there is no need to speak, and where the wool and silk industries support almost two-thirds of the inhabitants,” were proof enough of the power of industry.Footnote 10 In making these connections, Botero—the renegade Jesuit of Piedmont, secretary to the famed Milanese archbishop Carlo Borromeo, adviser to his nephew Federico in Paris and earlier to the Duke of Savoy Carlo Emanuele I, a thinker whose epochal importance is only now being fully recognized—was not alone.Footnote 11

Botero's extraordinary observation that “the power of industry is such that there is no silver mine or gold mine in New Spain and Peru that can be compared to it” seems to have informed if not inspired the 1613 Short Treatise on the Causes That Can Make Kingdoms Abound in Gold and Silver Even in the Absence of Mines of the jailed Neapolitan writer Antonio Serra, whom Joseph Schumpeter called “the first to compose a scientific treatise . . . on Economic Principles and Policy.”Footnote 12 And the eighteenth-century philosopher Ferdinando Galiani, who possessed a rare copy of the Short Treatise, explicitly followed Serra's precocious technical analysis (“If a given piece of land is only large enough to sow a hundred tomoli of wheat, it is impossible to sow a hundred and fifty there. In manufacturing, by contrast, production can be multiplied not merely twofold but a hundredfold, and at a proportionately lower cost”) in his devastating attack on the physiocrats in his 1770 Dialogues on the Commerce of Grain: “And voilà,” writes Galiani, “the great difference between manufactures and agriculture. Manufactures increase with the number of hands you put in, while agriculture decreases.”Footnote 13 And these are just furtive glimpses of what we have elsewhere called the “Italian tradition” of political economy, practiced from the late Middle Ages on and first theorized around the turn of the seventeenth century, a tradition that highlighted the individually competitive and civic benefits of pursuing and protecting high-value-added economic activities, such as the production of luxury woolen cloth.Footnote 14

The Business of Florence Is (the Wool) Business

In January of 1460 a civic debate (pratica) was held in Florence to address a proposal to move the Florentine Studio, the city's underfunded institution of higher learning, to Pisa, which had been purchased by the Florentines in 1402 and wholly subjugated four years later. The prominent lawyer Messer Otto Niccolini, who suggested that a university's proper functions—to train students in classical literature and the humane letters—were not compatible with the passions and interests of the Florentines, gave a striking speech in favor of the move:

This city, indeed from its very origins, has been dedicated to commerce and manufacturing, to which it has always devoted all its energies and efforts. Florentines believe that these activities are entirely responsible for sustaining and enhancing their republic, for ensuring the prosperity and the notable enrichment of private citizens, convinced that wealth has led to the growth of its reputation and authority. Putting other occupations to one side, they have always dedicated themselves especially to business.Footnote 15

The business of Florence, put simply, was and would always remain business.

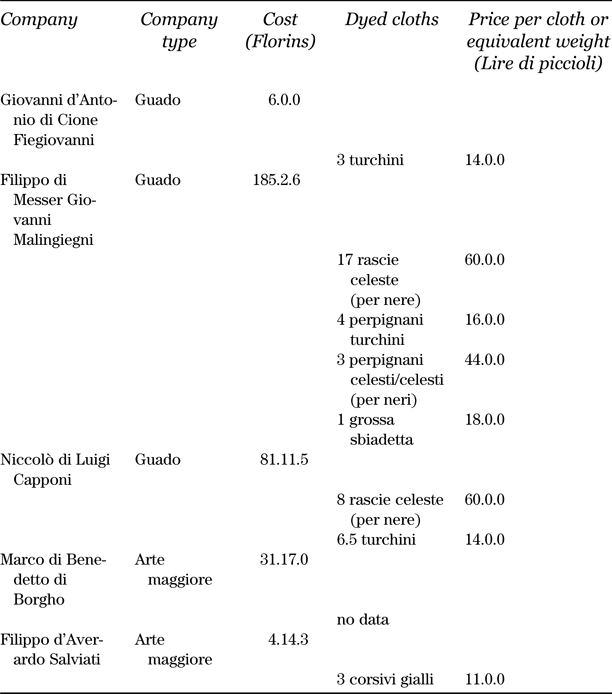

Although the economy of Renaissance Florence was diverse, and premodern merchants and entrepreneurs tended toward diversification and not specialization in order to guard against sector-wide downturns, the most important business in Florence was the production of woolen textiles. Woolens were the most significant domestic manufacture and export commodity in Florence between roughly 1200 and 1600. Wool textile manufacturing and, more broadly, the cloth and clothing sectors represented a large share of the Florentine rural and urban economies. In 1480, for example, they dominated the urban shop (bottega) economy, with nearly 8 percent of all shops, the highest for any group, being wool shops and nearly 27 percent dedicated to the cloth trade—very significant percentages especially if we keep in mind that a great deal of cloth production was done in the countryside and domestically (Figure 1). Profits from the local sale and regional and international exportation of woolens enriched Florence, increased its population, funded much of the cultural production for which it remains famous, and allowed Florentines to create a regional state in Tuscany that remained a major player in geopolitics for centuries. The export of woolens also allowed great Florentine families and family-centered partnerships to dominate the international banking sector in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, which in turn allowed Florentines to capture the English supply of very fine raw wool early in this period. Until its decline over the course of the sixteenth century, the Florentine woolen cloth industry sometimes outcompeted much larger wool-producing and manufacturing regions in Europe (chiefly England, and the Low Countries in manufacturing) to dominate some large markets for medium- and high-quality cloth in southern Europe, across the Mediterranean basin, and in the Near East.Footnote 16 Thus, the Florentine wool industry is an important early case of industry and commercial globalization that still has a great deal to tell researchers about international competition; the dynamics of comparative advantage, protectionism, and state capitalism; and the nature of East-West commercial encounters.Footnote 17

Figure 1. Shops (botteghe) in Florence by type, 1480. Darker shades represent closed or vacant shops. (Sources: Catasto 992-1024 [1480], Archivio di Stato di Firenze; Maria Luisa Bianchi and Maria Letizia Grossi, “Botteghe, economia, e spazio urbano,” in Gloria Fossi and Franco Franceschi, eds., Arti fiorentine: La grande storia dell’artigianato, vol. 2 [Florence, 1999], 27–64.) See supplementary material for a color version of this figure.

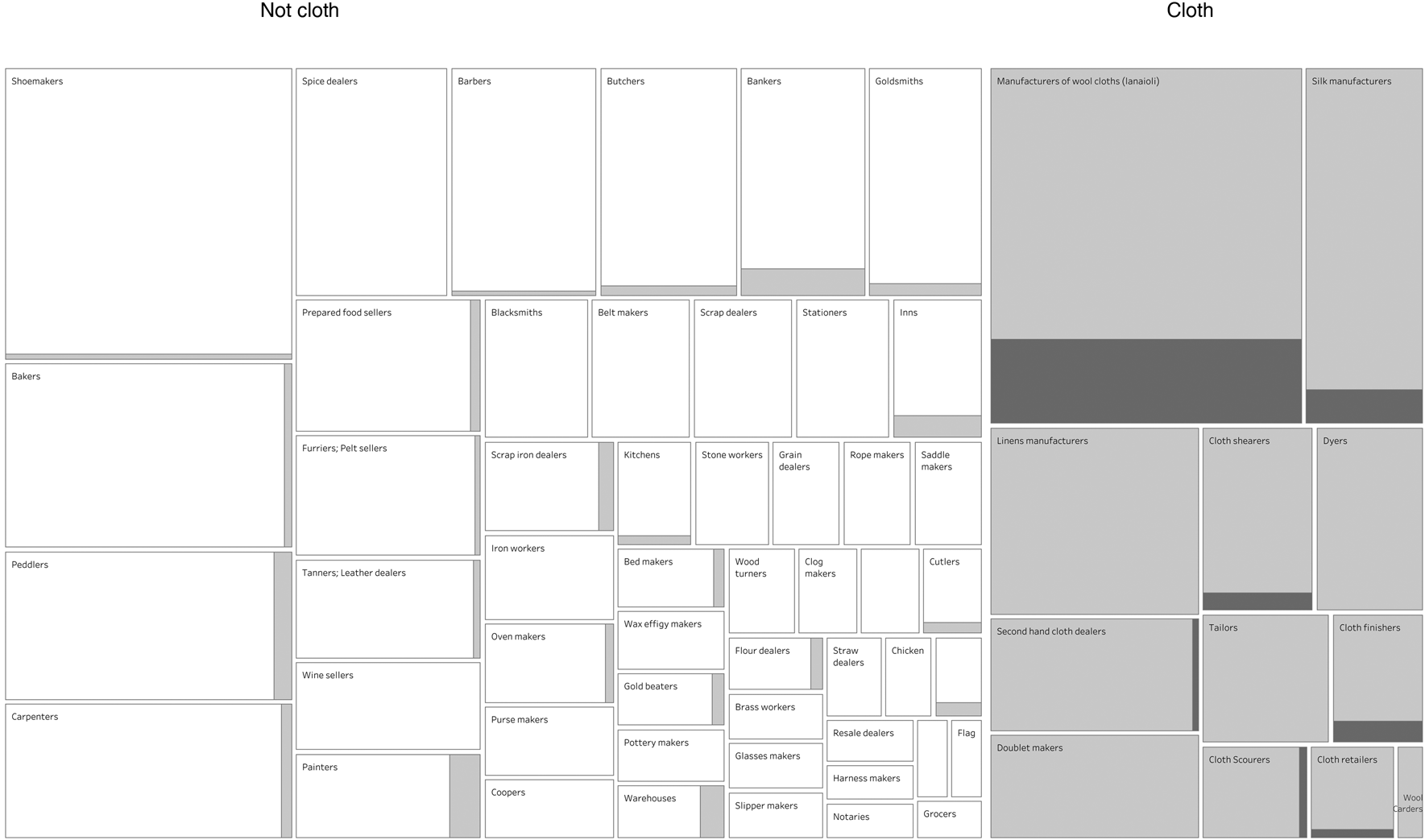

Unlike the silk and cotton textile industries, which relied in the earliest instance on the long-distance importation of raw materials and required larger-scale investments to get off the ground, the production of woolen cloth emerged organically all across northern and central Italy out of the traditional techniques and animal and material sources of longue durée domestic cloth production, and it dominated the industrial economy of the region, along with, for a while, the production of cotton-linen blends (fustians). By the early thirteenth century the production and export of cloth had become a global industry. Genoese merchants brought raw wool and dyestuff from North Africa; these were turned into low- and mid-quality cloths for mass consumption in Milan and the Lombard countryside and then traded by Florentine cloth merchants all over central Italy or exported to Mediterranean ports, especially Byzantine and Muslim ones, through Genoa. Yet Italian wool manufacturers could not, owing to technological inferiority and supply constraints, compete with the luxury woolens of Flanders and Brabant. On the Provençal market in 1308–1309, Florentine cloths fetched only around one-third of what the cloths of Ypres did.Footnote 18 In the early fourteenth century, the merchants of the famous Arte di Calimala (Cloth Merchants’ Guild) in Florence, such as the Del Bene company studied in detail by Armando Sapori in one of the early serious business-historical case studies, mostly purchased northern cloths for resale in other markets.Footnote 19 They also occasionally added economic value to their products by purchasing undyed and unfinished cloths from northern looms, finishing and dyeing them in Florence, and exporting them to the Levant, relying on their greater proximity to alum and dye supplies to undersell the Flemish in that market. Given industrial and supply factors, panni de Ypro tinti in Florentia (Ypres cloths dyed in Florence) could be more lucrative for Calimala merchants than local cloths.Footnote 20 As Giovanni Villani famously noted in his Chronicle, the Florentine wool industry saw enormous growth in price per cloth, and thus value, only when it switched its focus from the import and export of high-quality woolens to the local production of them, which required a steady supply of high-quality raw wool. The total production of woolen cloths fell precipitously between 1310 and 1336, the chronicler noted, but the later cloths, made from English wool, were worth twice as much as the earlier, which had been coarse and of low quality.Footnote 21 The 1330s, before the demographic collapse of the late 1340s, represented the high point of Florentine wool production value (Figure 2). It remains unclear to what extent this decline was the product of population decline, the shift to smaller-scale but higher-price cloths, or the contraction of the supply of English wool in relation to fluctuating royal policies and tariffs.Footnote 22

Figure 2. Wool production in Florence, 1300–1571. Production by amount (in braccia) and by amount per person. (Sources: For wool production, Francesco Ammannati, “L'Arte della Lana a Firenze nel Cinquecento: Crisi del settore e riposte degli operatori,” Storia economica 11 [2008]: 1–39; Ammannati, “Florentine Woolen Manufacture in the Sixteenth Century: Crisis and New Entrepreneurial Strategies,” Business and Economic History On-Line 7 [2009]: 1–9; Patrick Chorley, “Rascie and the Florentine Cloth Industry during the Sixteenth Century,” Journal of European Economic History 32, no. 3 [2003]: 487–526; and Chorley, “The Volume of Cloth Production in Florence, 1500–1650: An Assessment of the Evidence,” in Giovanni Luigi Fontana and Gérard Gayot, eds., La lana: Prodotti e mercati, 13–20 secolo [Padua, 2004]; Franco Franceschi, Oltre il ‘Tumulto’: i lavoratori fiorentini dell'Arte della Lana fra Tre e Quattrocento [Florence, 1993]; and Richard Goldthwaite, The Economy of Renaissance Florence [Baltimore, 2009]. For population figures, Maria Ginatempo and Lucia Sandri, L'Italia della città: Il popolamento urbano tra Medioevo e Rinascimento (secoli XIII–XVI) [Florence, 1990]; David Herlihy and Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, Tuscans and Their Families: A Study of the Florentine Catasto of 1427 [New Haven and London, 1985]; and David Nicholas, Urban Europe, 1100–1700 [New York, 2003].)

Until gradually surpassed by Spanish merino in the sixteenth century, England was the chief producer of the world's finest raw wool.Footnote 23 The best English wool was sourced from Lindsay and Lincolnshire (Lindisea), the Cotswolds (Contisgualdo), and the Welsh Marches (La Marcia), with the Herefordshire town of Leominster providing a common name for it (lana di limistri) in the Italian vernacular; by midcentury, it was precisely these “best of the best” regions that supplied the raw wool for Florentine firms.Footnote 24 After the invention of the foot-operated horizontal loom in the Middle Ages, production costs remained relatively steady, and the cost and availability of high-quality raw wool were the most important factors in the international trade.Footnote 25 Due to their high value-to-weight ratio, very fine woolens gave merchants a superior profit margin even in long-distance maritime and overland trade, where transportation and protection costs could be forbiddingly high for lower-quality cloths.Footnote 26 Until the third decade of the fourteenth century, though, the Italian wool trade centered on the sale of lower-quality textiles, while the Low Countries dominated the trade in fine wool cloth.Footnote 27 By the 1320s, though, and taking advantage of the disruption of western European industry caused by endemic warfare, Italian wool manufacturers were importing English raw wool of the highest quality directly from Southampton.Footnote 28 This transformation was also mirrored inside Florence by the simultaneous decline of the once-powerful Arte di Calimala, whose members had control of Florentine trade at the Champagne fairs, and the rise of the Arte della Lana (Wool Guild), whose producer-merchant members manufactured and exported woolens internationally.Footnote 29 By this time, Florentines dominated both international finance and the incredibly lucrative collection of taxes for the papacy. As a result, powerful “companies” like the Bardi and Peruzzi were able to make extensive loans to the English Crown, secured by income from English duties on the export of wool.Footnote 30 The “bill of exchange,” invented in medieval Italy, allowed Florentines resident in England to buy English wool with English papal taxes and to have their partners resident in Italy give the pope profits from other transactions in lieu of those English taxes.Footnote 31 By the mid-fourteenth century, three-quarters of the Florentine wool trade was in fine English wool imported raw to Florence and manufactured there for export, and the Arte della Lana had come to dominate the long-distance trade in high-grade textiles.Footnote 32 Similarly, Florentine lanaioli (manufacturer-merchants of woolen cloth), now working with the best wools, were better able to emulate the traditionally superior cloths of northern Europe: in 1341, for example, the firm of Cione and Neri Pitti and Co. offered cloths a modo di Borsella (in the style of Brussels), a modo di Doagio (of Douai), and a modo di Mellino (of Mechlin).Footnote 33 John Munro has cogently argued that this transformation also reflected and was causally linked to the decline of the Champagne fairs system under the weight of increasing transportation and transaction costs in western Europe as a result of endemic warfare and the decreasing costs of navigation and commercial transport at sea.Footnote 34 Similarly, later in the century, warfare in northern Italy may have disastrously increased the transportation costs for Lombard fustians heading to traditional markets in southern Germany, where new textile industries were then able to emerge.Footnote 35 Around the turn of the fifteenth century, if the accounts of the famed Datini firm of Prato are representative, the market in Spain—increasingly an exporter of raw wool—was still very hungry for finished Florentine cloths, with more than thirty times as many Florentine as non-Florentine cloths (including those of Prato) being sold at an average of more than double the price.Footnote 36

The commercial relationship between England and Florence around high-quality raw wool is revealing: wool was England's most lucrative export and one of the chief concerns of royal fiscal policy. Until approximately 1400, duties on English wool continued to rise and, since the cost of wool was the most important factor in profitability, to decrease profit margins in the international trade. Florentines, because of their loans to the Crown, were exempt from some of these duties but, even so, were quickly losing their competitive advantage over England and the Low Countries, particularly once the English Crown began a policy of systematically favoring the export of cloth over raw wool to encourage domestic industry.Footnote 37 Florentines therefore had to seek out other sources of wool. Florentine wool manufacturing firms fell into two distinct classes or sectors: the convent of San Martino, which manufactured English wool; and the convents of Garbo (in the neighborhoods of San Pancrazio and San Piero Scheraggio and in the Oltrarno), which manufactured wool sourced in Castile, Majorca, Minorca, and Provence and from Italian producers (so-called lana matricina). Beginning in 1408 the Arte della Lana demanded a strict separation between the two in order to maintain the international reputation of exporters in the San Martino cloths.Footnote 38 Nor did the power of the Arte della Lana end at the city walls: in the 1420s, the Florentines organized the entire Tuscan industry in terms of permitted and forbidden wool sources, privileging the capital and prejudicing the production of possibly rival city-industries like that of Pisa.Footnote 39 Such measures meshed nicely with the overall political-economic policies of the pre-Medicean Florentine state, which involved, in the words of Franco Franceschi, “support for and stimulus of textile manufacturing, regarded as the foundation of the Florentine economy; and protectionism on a massive scale to regulate in- and outflows.”Footnote 40

By the late 1480s, after a steady decline in the availability of English wool, the Garbo sector in Florence was dominant, at least in terms of production volume, with less than 25 percent of the total cloths produced based on English wool.Footnote 41 It was around the same time that Spanish wool began to overtake matricina in Florentine production, both in price and in volume. By the end of the fifteenth century, Spanish merino wool was beginning to rival English wool in quality and was becoming an essential part of the Florentine luxury woolens trade. After the mid-fifteenth century, the most important markets for Florentine garbo cloths were Ottoman territories in the Eastern Mediterranean and the panni di levante shipped eastward were made from matricina and from the wool of Castile.Footnote 42 By the 1470s as much as half of the total production of the Garbo sector was bound for the Levant, and this market helped revive the Florentine woolens industry, in a slump since the second half of the fourteenth century even though San Martino cloths remained popular in domestic and luxury markets.Footnote 43 The Florentine-Ottoman trade was fostered in the later period by Lorenzo de’ Medici's peaceful diplomacy with the Turks, including the Sultans Mehmed II and Bayezid II, and the opening up of new overland routes to compete with shipping from the Florentine ports of the Tyrrhenian Sea.Footnote 44 Florentine lanaioli, such as those of the collateral branch of the Medici family discussed at length later in this essay, imported raw wool from Spain, manufactured and finished it in Florence, and shipped the finished woolens by sea and then across overland routes (such as that through Nuovo Bazzaro, today's Novi Pazar, in the Raška region of Serbia) developed by the Turks to Pera, the Christian trading quarter of Constantinople. Silks from Bursa, at the end of the fabled Silk Road, along with other precious commodities, were then shipped back to Florence and on to other markets, like Lyon (Figure 3). Yet the late 1520s saw another serious downturn in the Florentine woolens industry: the product of plague, war (Rome would be sacked in 1527), more competition and higher prices for Spanish wool, and, very possibly, the rapidly diminishing Levant trade. Though silk was by this point coming largely from local and western sources, Sultan Selim I's embargo, from 1514 to 1520, on the import of Persian silk into Ottoman lands played havoc with the western trade at Bursa, where raw silk had once been lucratively traded for finished Florentine woolens, and which would soon lose its central role in the East-West cloth trade to Aleppo, giving an advantage to the Venetians over the Genoese and Florentines.Footnote 45

Figure 3. The Medici wool business in the Mediterranean, ca. 1520. (Sources: Simplified schematic from Mss. 553 and others, Selfridge collection. Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School; and Gertrude R. B. Richards, Florentine Merchants in the Age of the Medici [Cambridge, MA, 1932].)

The Selfridge Collection and Renaissance Business History

The scale, industrialization, and centralization of Florence's late medieval wool industry became an essential issue in economic historiography when Alfred Doren, at the turn of the twentieth century and in a monumental volume subtitled “A contribution to the history of modern capitalism,” presented, on the basis of chiefly normative sources like guild statutes, premodern Florentine lanaioli as highly organized, large-scale “supercapitalists” with partly centralized control over labor and production in their workshops. In his terms, they were industrial magnates (Industriemagnaten) with a huge accumulation of capital (gewaltige Anhäufung von Kapital) and of great capital (Großkapital) and with enormous economic power (ungeheure wirtschaftliche Machtmittel), in control of the guild of great industrialists par excellence (die Zunft der Großindustrielle κατ' εξοχήν).Footnote 46 In a long note in the later edition of his Modern Capitalism (1916–1919), Werner Sombart, who along with his near exact contemporary and critic Max Weber shaped the debate on the origins of capitalism in the first half of the twentieth century, rebelled against Doren's view, declaring wool firms in the city “essentially craft-based (handwerksmäßige) or at best small capitalist (kleinkapitalistische) enterprises,” adding, “Nowhere do we find the beginnings of large-scale enterprises. Any operations exceeding the dimensions of individual enterprises were built by the guild (e.g., the Tuchspannen),” the lattermost term being a reference to large structures for wool stretching (tiratoi), of which there were four in late sixteenth-century Florence.Footnote 47 Sombart was right. Wool manufacturing in Florence—which remained in essential ways the same from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries—was largely decentralized due to the protoindustrial system in place there, commonly called the “putting out” system. Wool was initially distributed to and worked by artisans, often women on the borders of Florence or in the countryside, in their own homes using their own tools. The wool was then collected and distributed to urban weavers and dyers.Footnote 48 Very little of the labor or production was centralized in a central workshop (Doren's zentralwerkstatt), and most occurred outside of direct oversight. Nearly all of the workers in the system earned piecework pay, rather than wages, and the presence of large numbers of precariously situated urban woolworkers in the city had been a significant cause of political agitation in the second half of the fourteenth century.Footnote 49 The consequences of this unrest led to decreasing (not increasing) centralization in the Florentine woolen cloth industry, which did survive the political strife, the demographic collapse of the Black Death, and significant regional depressions but ultimately fell victim to international competition.Footnote 50 Our image of the scale of the industry is now quite clear: the well-known and relatively large Del Bene firm, studied by the great Japanese business historian Hidetoshi Hoshino, produced (using over 98 percent English wool) an average of around 155 cloths per year in the period from 1355 to 1359 and, in its best year, had a profit margin of 40 percent before a sudden downturn in its business (Figure 4). And Franceschi has found, on the basis of production totals for 402 firms, that the average in precisely this period (1355–1374) was 122 cloths per annum.Footnote 51 The Arte della Lana was, as Doren had argued, controlled by the interests of the lanaioli, the full members or artefices pleno iure of the guild; however, they had likely never been, as in Flanders, master weavers or loom operators, but instead were and remained petty industrial entrepreneurs whose role in manufacturing was largely restricted to continuous processes of capital generation and management.

Figure 4. Del Bene wool manufacturing firms, 1355–1369. (Sources: Hidetoshi Hoshino, L'arte della lana in Firenze nel basso Medioevo: Il commercio della lana e il mercato dei panni fiorentini nei secoli XIII–XV [Florence, 1980], 213.)

An unusually auspicious confluence of women, men, and institutional support in the 1930s led to the earliest extensive use of a firm's account books to understand the business-historical and entrepreneurial dynamics of Renaissance wool manufacturing. And it was this approach that, practically speaking, consigned Doren's view to obsolescence and spurred much of the most vibrant premodern business-historical research of the twentieth century. The shift in approach came, like a bolt, with the publication in 1941 of Raymond de Roover's essay “A Florentine Firm of Cloth Manufacturers,” which had been written while the young Belgian business historian was an MBA student at Harvard Business School—working under N. S. B. Gras, holder of the first chair in business history and architect of HBS's business history curriculum—and submitted originally as a thesis for a Harvard University prize in 1938.Footnote 52 De Roover's “fresh perspective” in the article “led to a major revision in our understanding of the organization of the cloth industry in Florence,” according to Richard Goldthwaite; it did so by focusing on the “actual business practice of an individual firm” and by “de-emphasizing the guild and revealing the considerable fluidity in human relations inside the system and therefore the more amorphous quality of industrial society” in the Renaissance.Footnote 53 De Roover would go on to become, in the words of David Herlihy, “the historian sans pair of medieval business and banking institutions,” his reputation having been secured in perpetuum with his 1963 masterpiece The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank. Footnote 54 De Roover's preliminary investigation of the Medici bank had been published fifteen years earlier and dedicated to Gras, “whose teaching inspired this study on one of the most famous business firms in history,” and there is no doubt that de Roover's background in accounting—he had been an accountant in Antwerp before emigrating to the United States—and training in business methods under Gras were together the foundation of his extraordinary talents and productivity.Footnote 55 But the “Florentine Firm” was based, more immediately, on the work of another scholar, Florence Edler de Roover, who, before meeting Raymond in Antwerp and marrying him in England in 1936, had worked under Gras's supervision on a project funded by the Medieval Academy of America to prepare a lexicon of medieval Italian business terms, the detailed appendices of which—based on her extensive use of the collection of Medici family business manuscripts (focused on cousins of the more famous branch of the Medici dynasty that was comprised of bankers, popes, and later Grand Dukes of Tuscany) donated to HBS by the Anglo-American retail magnate Harry Gordon Selfridge—laid the groundwork for Raymond's study.Footnote 56 That Edler de Roover's extraordinary paleographical skills permitted her husband to reconstruct the account books of the “Florentine Firm” is without doubt, just as her discovery of the libri segreti (secret books) of the Medici bank provided the foundation for his magnum opus.Footnote 57 This essay, in returning to the same Selfridge manuscript books used by Edler in her Glossary and de Roover in “A Florentine Firm,” is similarly based upon the couple's pioneering efforts.

The Medici as Industrial Entrepreneurs

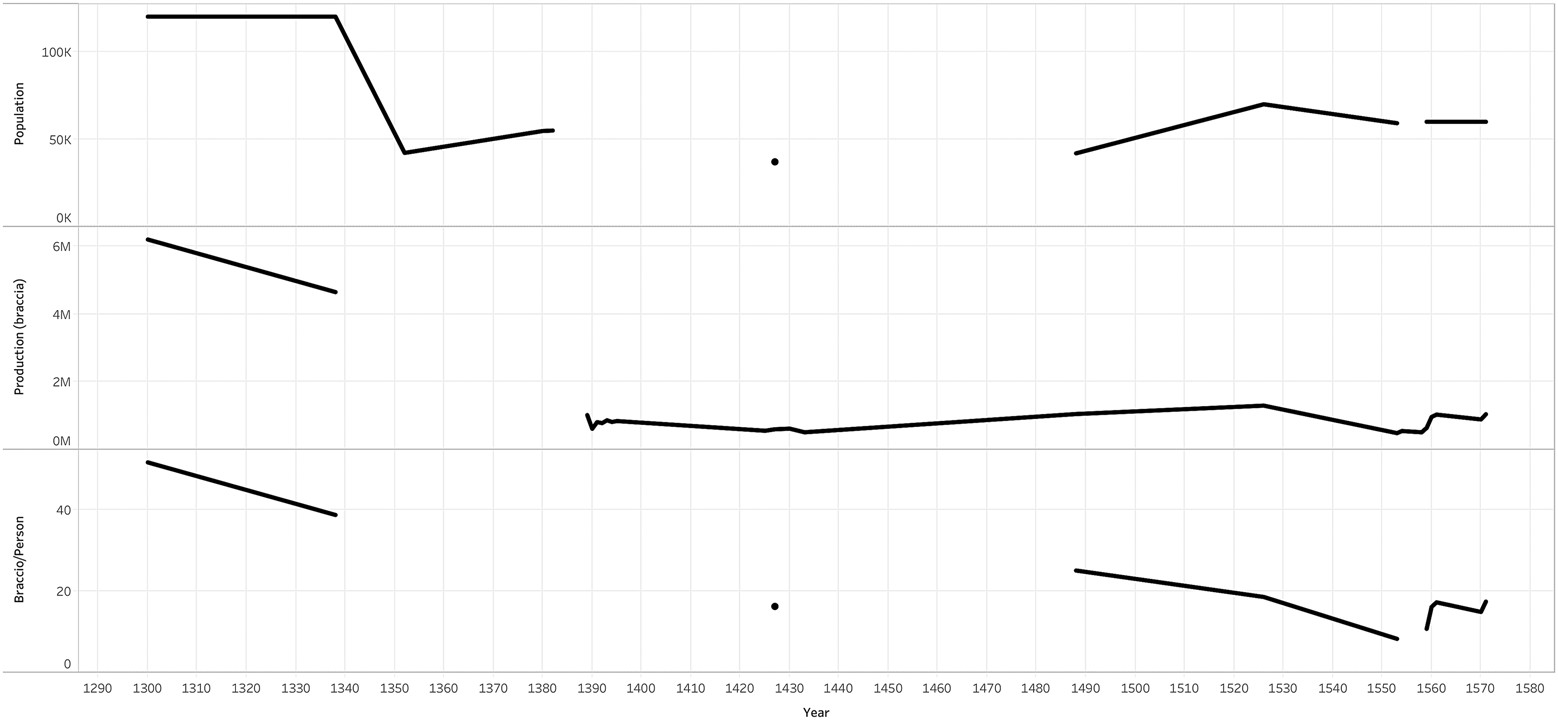

In his classic The Rise and Decline of the Medici Bank, Raymond de Roover devoted one chapter to “the Medici as industrial entrepreneurs,” examining the main branch's investment in three cloth manufacturing botteghe, two wool and one silk. These shops were not, compared with the family's banking activities, a large source of profits; in the period from 1420 to 1435, for example, the one wool shop then operating provided only 3.1 percent of the bank's profits.Footnote 58 But de Roover's idea of industrial entrepreneurship provides us with a model for presenting a case study of a single Medici wool firm's operations. Compared with some of the other wool manufacturing firms in the Selfridge collection, the firm of Francesco di Giuliano di Raffaello de’ Medici and Co. (1556–1558), which produced only seventy-one woolen cloths, was relatively small. The survival of nearly all of its account books, however, allows for the fullest reconstruction of a firm from the Medici branch represented by the collection. All but one (a book of weavers) of the firm's eight account books, purchased as a set in 1556 from the firm of stationers (cartolai) Giovanbattista Fontani and Co. for 48 lire di piccioli (6.86 florins), are extant (Figure 5).Footnote 59 These books were organized hierarchically, with the ledger (“debtors and creditors” book), in which the tally of sold cloths (panni finiti) functioned to calculate profits and losses, as the book of final entry into which fed two subsystems of books: one dealing with the direct costs of manufacturing (Filatori, Tessitori, Tintori e Lavoranti, Manifattori) and the other with the operation's indirect costs and cash expenditures (Quadernaccio, Entrata e Uscita e Quaderno di Cassa, and Giornale). Figure 6 shows the middle volume. Like nearly all the wool companies of the period, the firm itself, which operated for the two years from May 1, 1556, to April 30, 1558, was little more than a small core of employees and an amount of capital. The firm rented its bottega and equipment and had only four salaried employees: Rosso di Giovanni de’ Medici, maruffino (two-year term beginning May 1, 1556, salary of f.40/year), who kept the firm's books; Amerigo di Giovanni de’ Medici, giovane (eighteen-month term beginning November 1, 1556, salary of f.16/year); Francesco di Piero Tucci, giovane (thirteen-month term beginning November 1, 1556, salary of f.20/year); and Antonio d'Agnolo fornaio, fattorino (six-month term beginning November 1, 1556, salary of f.6/year).Footnote 60Figure 7, which shows a breakdown of the firm's total operating costs of 3,076.75 florins, also serves as a basic schematic of the entire manufacturing process (from preparation to spinning to weaving to dyeing to finishing).Footnote 61 The firm was not profitable, but its overall costs (excluding the cost of raw wool; see below) were not unlike those of other Medici firms, even much larger ones. Figure 8 shows the two Medici firms operating in the period of 1530 to 1543, which were more than five and fifteen times the size, respectively, in total output.

Figure 5. System of account books. For the firm of Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione A, 1556–1558. (Sources: Mss. 567-2, 567-7, 567-8, 567-11, 568 v.6, 568 v.9 [12], and 600-5, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

Figure 6. Cover of a Medici Account Book. “Inflow and Outgo and Cash Notebook,” Entrata e uscita e quaderno di cassa, Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione A, 1556–1558. (Source: Ms. 568 v.6, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

Figure 7. Breakdown of operating costs of a Medici wool firm. Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione A, 1556–1558. (Sources: Mss. 567-11 [quaderno de’ manifattori] and 567-8 [libro grande bianco A], Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

Figure 8. Two Medici wool firms. (Sources: Mss. 554-6 and 558-7, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

The firm was operated by Francesco's father, Giuliano, for whom we have in the Selfridge collection an extant set of richordanze beginning with his 1547 marriage to Margherita, the daughter of Giovanni de’ Nerli, who brought him a 2,700 florin dowry. In them, Giuliano records family milestones—the births and baptisms of his children, first Costanza, then Francesco (so named “to reinstate the name of Francesco my uncle and Francesco my brother”), Caterina, and Giovanni (named for his father-in-law), who died in his ninth month; and the deaths of Margherita at age thirty-three and of his father, both in 1555—and civic honors, from his service as Podestà of Montepoli in the Arno valley and as consul of the Arte della Lana to his election to the Otto di Pratica and Dodici Buonuomini, by this point two magistracies in the ducal administration of Tuscany.Footnote 62 Giuliano's memoranda also included a number of property transactions and were kept at the end of a giornale containing accounts of chiefly personal or domestic business, with about one-quarter of all entries in the first two years of his marriage to Margherita pertaining to his wife's expenses.Footnote 63 Giuliano himself would die in 1569 at the age of sixty-three.

At the start of May 1556, the merchant Jacopo Pandolfi sold the firm its first supplies of raw material: eleven bales of Spanish wool “of varying types [di piu sorte]” with a combined weight, including ropes and packaging, of 3,214 pounds. The firm paid f.10 s.10 per 100 pounds, which was calculated after the subtraction of combined tare (“tara per tutte le tare #297”) equal to 9.25 percent of the weight, or f.306 s.5 total for a nominal weight of 2,917 pounds.Footnote 64 This wool was unpacked, likely in the firm's bottega, and sorted into twenty-two sacks (of variable weight, ranging from 125 to 160 pounds) with a combined weight of 3,110 pounds.Footnote 65 In 1556–1557 the firm acquired around 8,675 pounds of raw wool all told, of which approximately 63 percent was Spanish and the rest Italian (Tuscan matricina and wool from castroni, castrated bucks), which was sorted into sixty sacks and, in the case of the Italian wool though not the Spanish, graded (as fina, seconda, or grossa). The purchase of raw wool accounted for 30 percent of the total production costs of this firm, by far the largest single category, even though it was lower than the 35 percent and 44 percent spent on wool by the related Medici firms operating from 1530 to 1543 and by the Brandolini firm examined by Goldthwaite at 40 percent. The Spanish lana della serena supplied by the Spaniard Lopez Gallo, which made up more than a quarter of the total, was by far the most expensive at f.24 s.10 per 100 pounds, followed by Italian wool shorn from castrated sheep at f.13 per 100 pounds (Table 1).

Table 1 Medici Wool Supplies, 1556–1557

For the Firm of Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione A

Sources: Mss. 600-5 and 567-8, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.

* additional expenses of f.0 s.1 d.5 were paid for the canvas sacks, ropes, the gabella di Cortona, etc. ** combined with the 3 August 1557 total below.

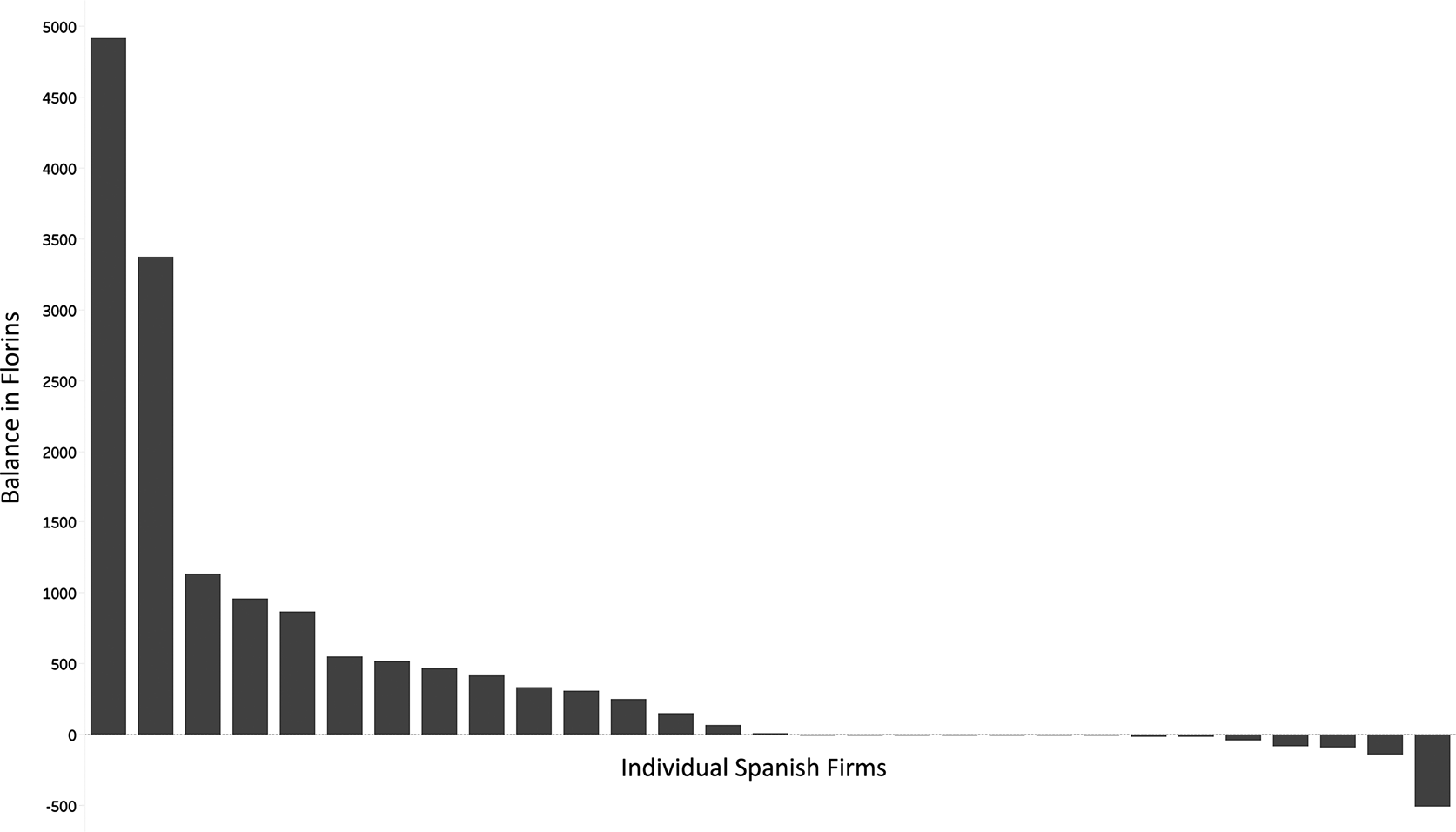

The raw wool purchased in the period from 1491 to 1495 by the Medici firm of Giuliano di Giovenco and his son Francesco, “wool manufacturers in Porta Rossa,” included both matricina and garbo, from local merchants—among them the wealthy and influential Jacopo di Giovanni Salviati, who was married to Lorenzo de’ Medici's daughter Lucrezia, sister of the future pope Leo X, and a number of his relatives—and from Spaniards resident in Florence including Miguel de Miranda, Miguel de Silos, and Fernando and Juan de Castro.Footnote 66 Raw wool was delivered in bales, wrapped in cloth and tied with rope, and distinguished in accounts by gross weight (e.g., “one bale gross weight 237 pounds”); the final purchase price (netto a pagamento) was calculated by the pound after the assessment of tares (tare), with allowances for ordinary wear-and-tear (per uso), for humidity or wetness, dirt or sand, and the weight of the ropes and packaging materials. So, for example, when on July 18, 1492, Miguel de Silos delivered six bales of wool weighing 1,381 pounds to the Medici partners, the tares combined for 117 pounds (nearly 8.5 percent of the total), and the final price (f. 145, s. 6) reflected a weight of 1,264 pounds.Footnote 67 The notebook of first entry (quadernaccio) of Giuliano di Giovenco's great-great-grandson Giuliano di Raffaello's firm (1552–1555) similarly shows the Medici wool manufacturer sourcing raw wool from a variety of sources. Six decades on, Spaniards were even more common as suppliers of raw wool, both Spanish and Italian matricina, and notably also as buyers of finished cloths: one Luis de Polanco, for example, sold the Medici wool from central Italy (matricina di toschanella) and bought both undyed cloths (panni bianchi) and smooth black rascie, the most expensive cloths sold by the Medici in the sixteenth century; while Lopez Gallo, who supplied raw Spanish wool, bought lower-quality coarse cloths (panni corsivi), both undyed (bianchi) and dyed blue (turchino) and pink (roseseche), as well as undyed twill (lana alla piana) and again especially the fine black rascie. These Spaniards specialized in selling wool, but that was not all; in August of 1563, for example, Juan Alonso de Malvenda sold Giuliano di Raffaello and Co. sugar from the Canary Islands (zuchero di canaria), where the Spaniards had introduced sugar cane at the end of the previous century, and larger quantities of lower-quality sugar from India (zucheri rottami d'India).Footnote 68 In 1556, the same Lopez Gallo bartered his raw wool for some of the black rascie it would produce, or 1,000 pounds of the finest Spanish wool for 3 bolts of rascia together weighing 201 pounds and valued at 222.74 florins, a weight-value ratio of about five to one between the raw material and the manufactured good.Footnote 69 In the period between 1490 and 1550, studied by Bruno Dini, the Salviati firm did business with some twenty-six Spanish merchants; of them, more than half either broke even (bartering goods for goods: 60 percent of the time Spanish raw wool, and 32 percent of the time Spanish silk, for finished silks and woolens) or ended up with a negative balance with the Salviati (Figure 9).Footnote 70 In addition to wool, this firm directly purchased a number of other supplies, including some of the dyestuffs used in the dyeing process; as the company's ledger records show, these included “various red dyes, orchil, and others to dye this firm's cloths [piu robbie, oricello, e altro per tignere i panni di questa ragione].”Footnote 71 Other necessary supplies for the manufacturing and finishing processes included soap and, costliest of all, oil. The Medici paid l.373 s.19 d.0 in total for 22.5 barrels of oil, purchased over a period of fourteen months from “various oil sellers [piu oliandoli]” at prices ranging from l.13 s.5 d.0 to l.18 s.14 d.0 di piccioli per barrel.Footnote 72

Figure 9. Spanish merchants’ balance with Salviati firms, 1490–1500. (Source: Bruno Dini, “Mercanti spagnoli a Firenze (1480–1530),” in Dini, Saggi su una Economia-Mondo: Firenze e l'Italia fra Mediterraneo ed Europa, (secc. XIII–XVI) [Pisa, 1995], 289–310, at 297.)

In addition to wool quality, dyeing and final color had historically strongly affected the quality and price of sold textiles, and the cost of dyeing was itself affected by the quality of the dyestuffs being used, the quality of the wool being dyed, and whether the cloths needed to be dyed only once or re-dyed to produce the final color.Footnote 73 An exemplary case of the role played by the dyestuffs themselves relates to the etymology of the word “scarlet.” Munro has amply shown that, before it was an adjective referring to a bright red-orange color, “scarlet” signified the most expensive and luxurious woolen cloth of the Middle Ages—in Italy called scarlatto di grana, which was produced with the finest English wool and the red dye kermes, commonly called “grain” or grana and derived from the tiny, dried eggs of Mediterranean shield lice.Footnote 74 In a 1339 statute, the Florentine Arte di Calimala promulgated strict guidelines for maintaining the unique, luxury status of scarlatti: authentic scarlatti, called scarlatti di colpo, had to be dyed from white or an intermediate shade of gray only with the red dye kermes, which itself cost more than one-third of the total cost of production in the early fourteenth century, while cloths dyed with a mixture of kermes and madder, a cheaper vegetal dye called robbia in the Tuscan vernacular, had to be sold as scarlattini or panni di mezzagrana.Footnote 75

Dyeing was a craft (arte), but it was also a chemical process requiring, in addition to the dyestuffs, the application of heat and use of mordants or fixants in order to make the finished cloths colorfast, that is, with colors resistant to running or fading. Inexpensive and locally available mordants included tree bark and, especially in woad dyeing, wood ash, with its high alkalinity; in contrast, high-quality dyeing, especially with vibrant reds, increasingly came to rely on chemical mordants like gromma (potassium bitartrate, or cream of tartar), a byproduct of winemaking, and, especially, allume (alum), of which several types were known, the best being the so-called allume di rocca (potassium alum, or the potassium double sulfate of aluminum).Footnote 76 The demand for allume di rocca could be great—and acquiring it even played a role in the decision of Lorenzo de’ Medici, then the de facto prince of the Republic of Florence, to participate in the sack of Volterra in 1472 after its leaders reneged on a concession of its newly discovered alum deposits—as reflected in the amounts required for a dyeing firm's annual operations: in the year between July 1498 and July 1499, for example, in addition to dyes including robbia, oricello, and scòtano, and smaller amounts of gromma, the firm of Raffaello di Francesco de’ Medici and Co., tintori d'arte maggiore, purchased from the Arte della Lana more than 24,000 pounds of allume di rocca for a total of f.288 s.4 d.3, at a rate of 12 florins per 1,000 pounds.Footnote 77

In order to produce a wider range of final colors, Florentine lanaioli relied on the layering of colors, with a first and second stage of dyeing. The first stage was often performed by tintori di guado, dyers who used woad, a vegetal indigo dye, to produce a wide range of blues and who often dyed “in the wool” as well as in the thread or in the finished cloth. The blue hues common in Tuscan sources ranged from allazzato (very light) to turchino to sbiadato (etymologically linked to our word “blue”) to cilestro to perso (very dark). The second stage, generally done in the finished cloth, was executed by tintori d'arte maggiore, dyers who performed the more important part of the dyeing process, using a variety of dyestuffs, among which reds commonly predominated.Footnote 78 The large chromatic range available to Florentine lanaioli, and the two-stage dyeing process sometimes used, can be seen in the cloths produced by the wool manufacturing firm of Raffaello di Francesco de’ Medici (1531–1534). Figure 10 depicts the intermediate and final colors of the cloths sold by the firm in the terminology employed in its end-of-period ricordo of sold cloths.

Figure 10. Cloths sold by intermediary and final color. Raffaello di Francesco de' Medici & Co., ragione L, 1531–1534. (Source: Ms. 554 [4], Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

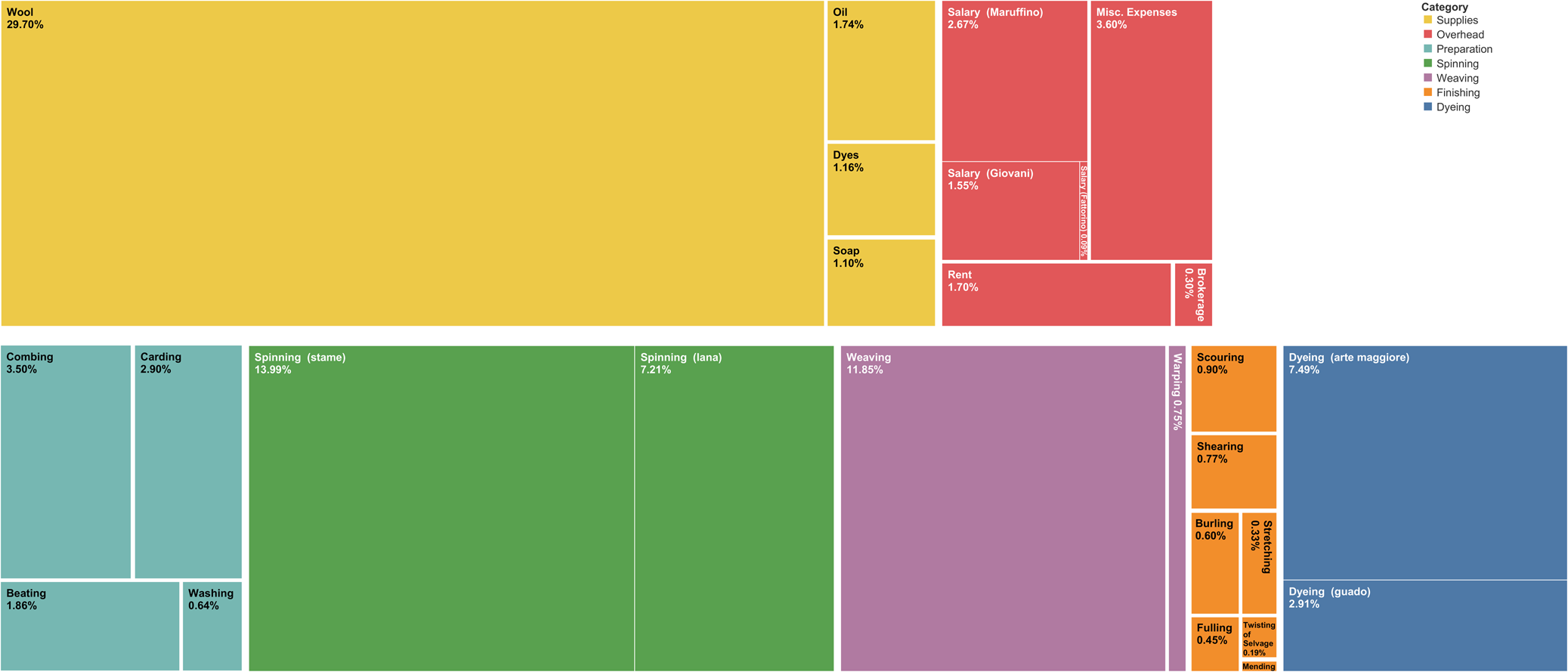

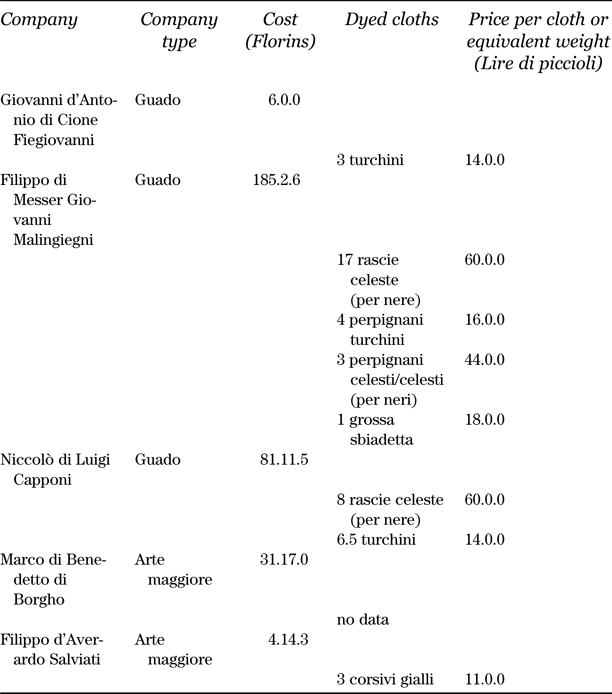

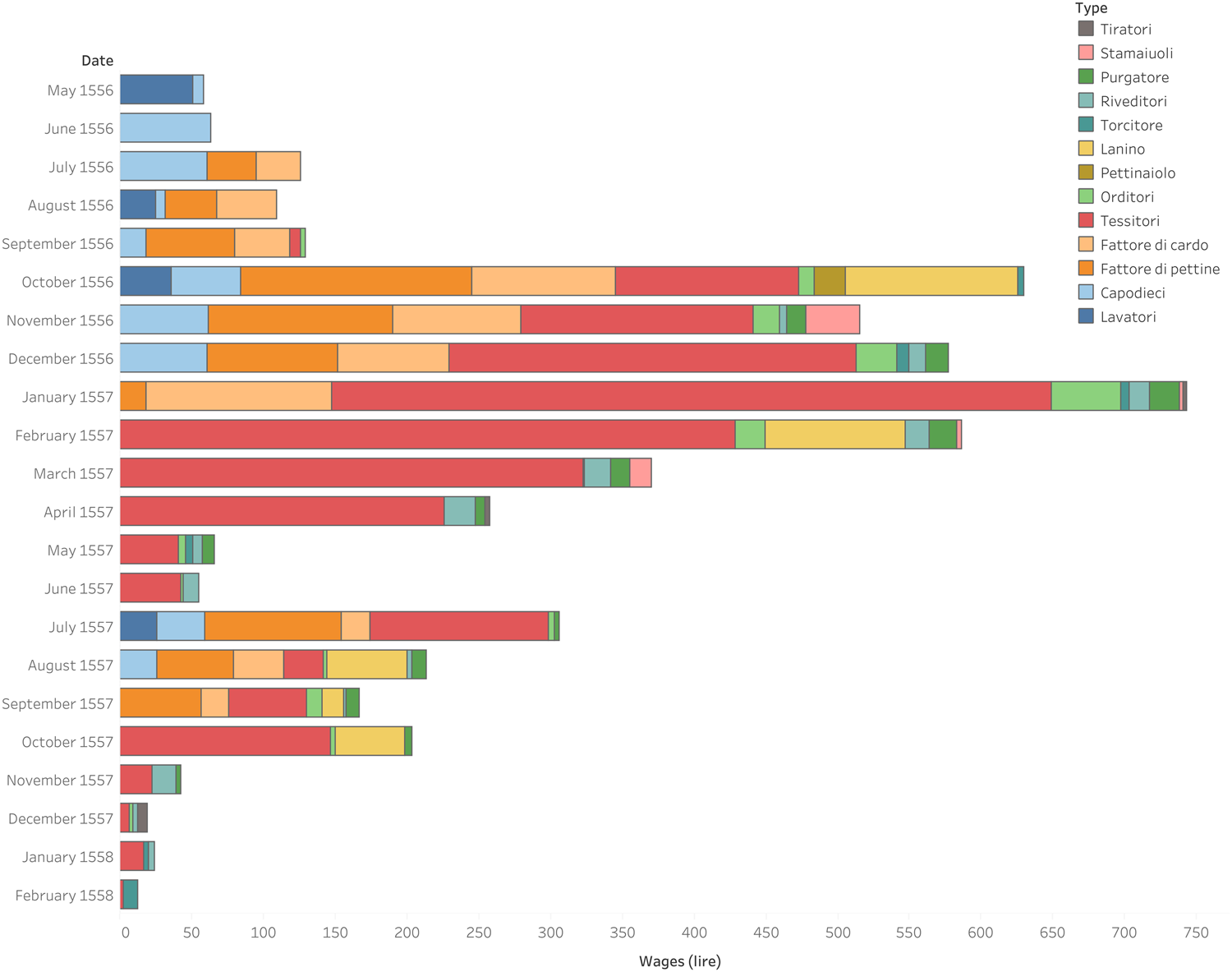

Only 8.4 percent of the cloths remained undyed. Nearly 56 percent of the cloths were dyed blue; of these, some 18 percent remained sky blue (cilestro), 30 percent were dyed red after being dyed cilestro to produce a final black (nero), and 42 percent ranged from sbiadato to paonazzo (a popular dark purple) or to dark shades of green. The remaining 36 percent ended up as grays, tans, yellows, oranges, and a mix of other colors. The firm of this case study, Francesco de’ Medici and Co., outsourced the dyeing of its cloths, which represented a little over 10 percent of its total operational costs, to five outside firms (Table 2).

Table 2 Medici Outsourcing to Dyers

Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione A, 1556–1558

Sources: Mss. 567-7 and 567-8, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.

The data for the arte maggiore dyeing is incomplete, but the guado firms, as expected, charged more for producing darker shades of blue and for dyeing higher-quality cloths. The costliest procedure was dyeing so-called rascia cloth sky blue so that it could then be dyed a second time, or overdyed, probably with a mix of kermes and madder, in order to produce the most sought-after cloth on the mid-sixteenth-century Florentine market: rascia nera, or black rascia. Quality of cloth was a crucial variable: the cost of dyeing a rascia cloth sky blue resulted in a 36 percent cost increase over dyeing a perpignano the same color. The gradual shift from the predominance of blues in the fifteenth century to more costly, twice-dyed blacks in the sixteenth was naturally the result of changes in fashion, but the intervention of the Arte della Lana had also been crucial. Florentine rascie, plausibly deriving their name from the city of Raška in Serbia, were originally intentionally developed as an import-substitution measure to compete with the so-called rascie di schiavonia that were of a surprisingly high quality and were entering the Florentine market in the mid-fifteenth century. In February of 1488, the Arte della Lana, considering the invasion of foreign cloths, decided to forbid the sale of Slavic rascie and to encourage the manufacturing of native rascie by instituting production quotas. The Arte della Lana had in 1418 similarly encouraged the production of perpignani cloths, a kind of light and elastic serge commonly used for making men's hosiery, named for the cloths of Perpignan, and made from Spanish garbo and local Italian wools. The perpignano was the major Florentine textile of the fifteenth century and again in the seventeenth, when the cheaper fabric entirely overtook rascia. But it was the production of black rascie that, almost alone, contributed to a spike in the 1560s (see Figure 2) and for the first time allowed Florentine cloths to penetrate ultramontane markets.Footnote 79

Once wool was purchased and sorted, the firm of Francesco di Giovanni di Giunta and Co., “washers at the canal [lavatori alla gora],” was hired to wash the sorted raw wool in an industrial canal and paid a flat rate of l.1 di piccioli per 100 pounds of washed wool in addition to being compensated for the alum used in the process at a rate of l.20 di piccioli per 100 pounds. On Saturday, May 2, 1556, for example, the washers received the first twelve sacks of Jacopo Pandolfi's Spanish wool, weighing 1,660 pounds. The washed wool weighed 1,350 pounds, representing a loss of 18.7 percent of the original weight (near the average of 19.45 percent loss), and the washing cost l.13 s.10 piccioli, paid along with l.12 for the 60 pounds of alum used.Footnote 80 All told, 6,630 pounds of wool (final weight) was washed and returned to the Medici in 1556–1557. The washed wool was then entrusted to Battista di Pasquino da Bacchereto, a kind of foreman in the Medici operation called a capodieci (i.e., one nominally in charge of ten workers), who distributed the wool for picking, beating, and cleaning (a process called divettatura, from vetta, a stick or pole used to strike the wool); he then collected it and sent it on for further work. The capodieci was paid by the pound—d.8 (for 554 lb.), s.1 (for 2,729 lb.), s.1 d.4 (for 783 lb.), and s.1 d.8 (for 2,207 lb.) for a total of l.391 s.2 d.8 di piccioli—with the rate dependent on the cloth that would ultimately be produced, such that wool destined to become rascie fetched the highest rate and wool for selvage (vivagno) the lowest.Footnote 81 The capodieci sent some of the cleaned wool directly for dyeing in the wool (nel colore)—for example, between August 5 and August 10, 1556, Battista di Pasquino sent 741 pounds (equivalent to 9.5 panni of 78 lb. each) to two companies of woad dyers (tintori di guado) that were paid l.14 per panno for turchini—but most was dyed after weaving, as part of the finishing process.Footnote 82 The capodieci was not the only such figure in the enterprise. Indeed, Medici and Co. similarly delegated two of the other major steps in the manufacturing process, combing and carding, to agents (fattori) to whom it made variable cash payments on a weekly schedule (almost always on Friday or Saturday) when active and who were in turn responsible for organizing and paying workers, with whom the firm itself had no direct contact, to do the necessary work. Over the course of two active periods (July 1556 to January 1556/7 and July to September 1557), Agniolo di Giovanni—called “nostro fattore di petine [our agent who oversees combing]”—received thirty-three cash payments (ranging from l.2 s.12 d.8 to l.43 s.8 di piccioli) in the total amount of l.724 s.15 d.4 di piccioli, while Antonio di Domenico da Prato—“nostro fattore di chardo [our agent who oversees carding]”—received thirty-seven weekly cash payments (ranging from 1.5 to 1.37 s.10 di piccioli) in the total amount of l.592 s.9 d.8 di piccioli.Footnote 83

At the artisanal core of every lanaiolo's operation was the process of turning spun woolen yarn into cloth: a matrix, tightly interlaced at right angles, of longitudinal warp threads, made from combed wool (stame) and held in tension on the loom, and the thicker transversally woven weft, made from carded wool (lana). Our firm used three nonsalaried agents to distribute stame and lana and pound-rate wages to spinners in the Florentine countryside, all of them women, and to collect and deliver the spun yarn to its bottega (Table 3): Tommaso di Christofano Brandolini (nostro lanino), who distributed lana; Alessandro di Domenico da berzighella (nostro stamaiuolo); and Pagholo di Lorenzo dal Borgho (stamaiuolo).Footnote 84

Table 3 Distribution of Combed and Carded Wool

For the Firm of Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione A, 1556–1558

Source: Ms. 567-2, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School. Notes: Excluded from Lanino: 276 pounds of lana grossa per vivagno at a rate of 0.2.0; 71 of grossa sbiadata per vivagno at 0.2.0; and 100 of bioccoli at 0.2.4. Excluded from stamaiuoli: 196 grosso per vivagno at 0.4.0; 51 grossa sbiadata per vivagno at 0.7.0; and 62 grossa per vivagno at 0.7.0.

* less than 15% at lower rate

As seen in Figure 11, which shows the cash payroll of the firm by month, the distribution/collection of yarn (including spinning, indirectly) and its subsequent weaving made up the bulk of the labor cost (in cash expenditures) and manufacturing process (in time), processes that occurred immediately after the acquisition and cleaning of new raw wool supplies.

Figure 11. Payroll (wages by type) of a Medici firm. Francesco di Giuliano de' Medici and Co., ragione A, 1556–1558. (Sources: Mss. 567-8, 567-11, and 600-5, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

The firm paid twenty-six weavers, though each likely worked as half of a pair operating the horizontal loom, to produce all of its fabric—a cascading process that occurred when the availability of yarn and cash (on the Medici side) and of weavers aligned. In the absence of more reliable data, we can use the dates of the cash payments to weavers as a proxy for estimating the duration of the weaving process, with a full-size cloth seeming to require around two calendar weeks of weaving (compared with, for example, three to four weeks for the Brandolini firm) (Figure 12). For example, the most productive of our firm's weavers, Catarina di Gabriello da Milano, worked four months to produce seven cloths.

Figure 12. Payments to weavers. September 1556–February 1558, Firm of Francesco di Giuliano de' Medici and Co, ragione A. (Source: Ms. 557-8, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

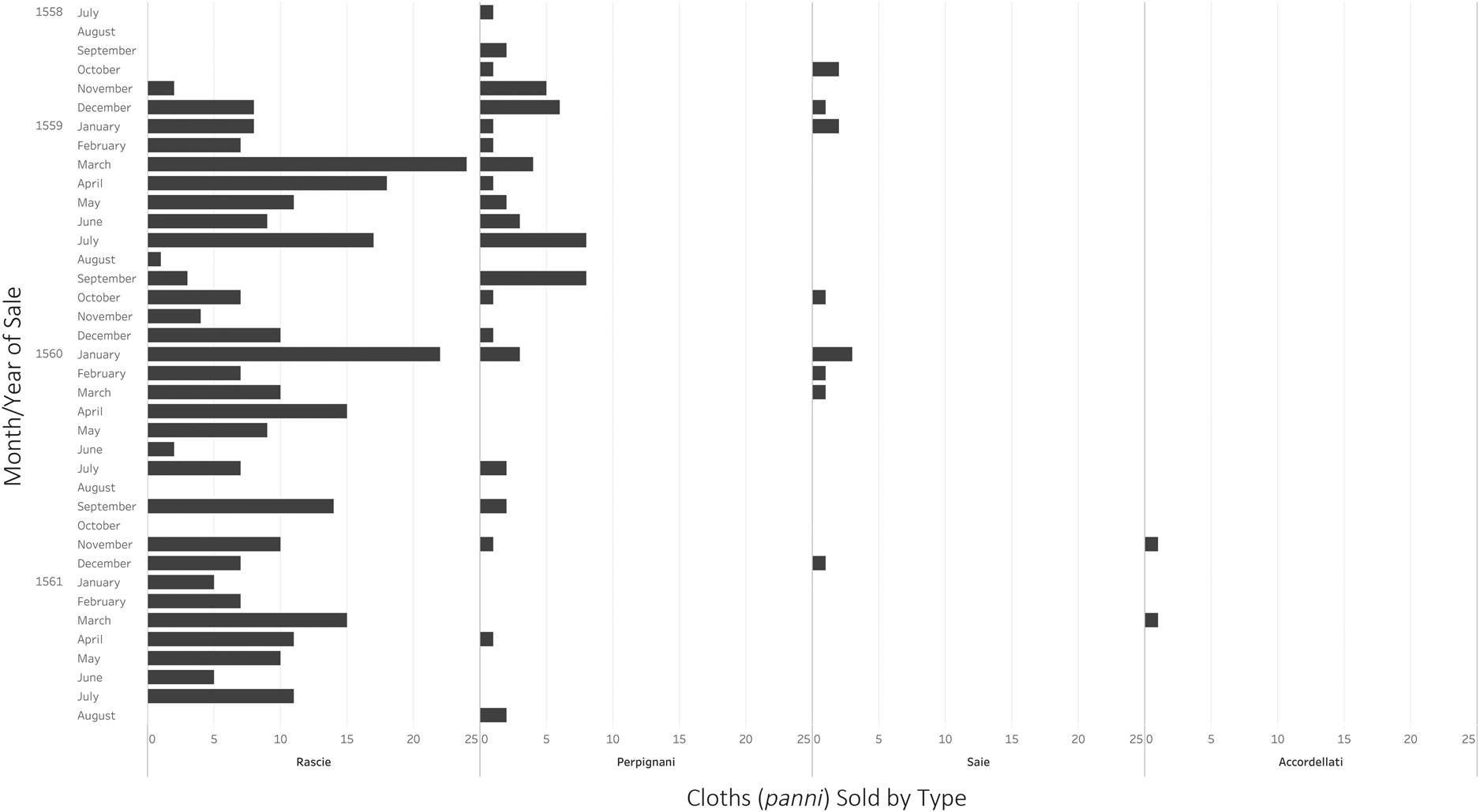

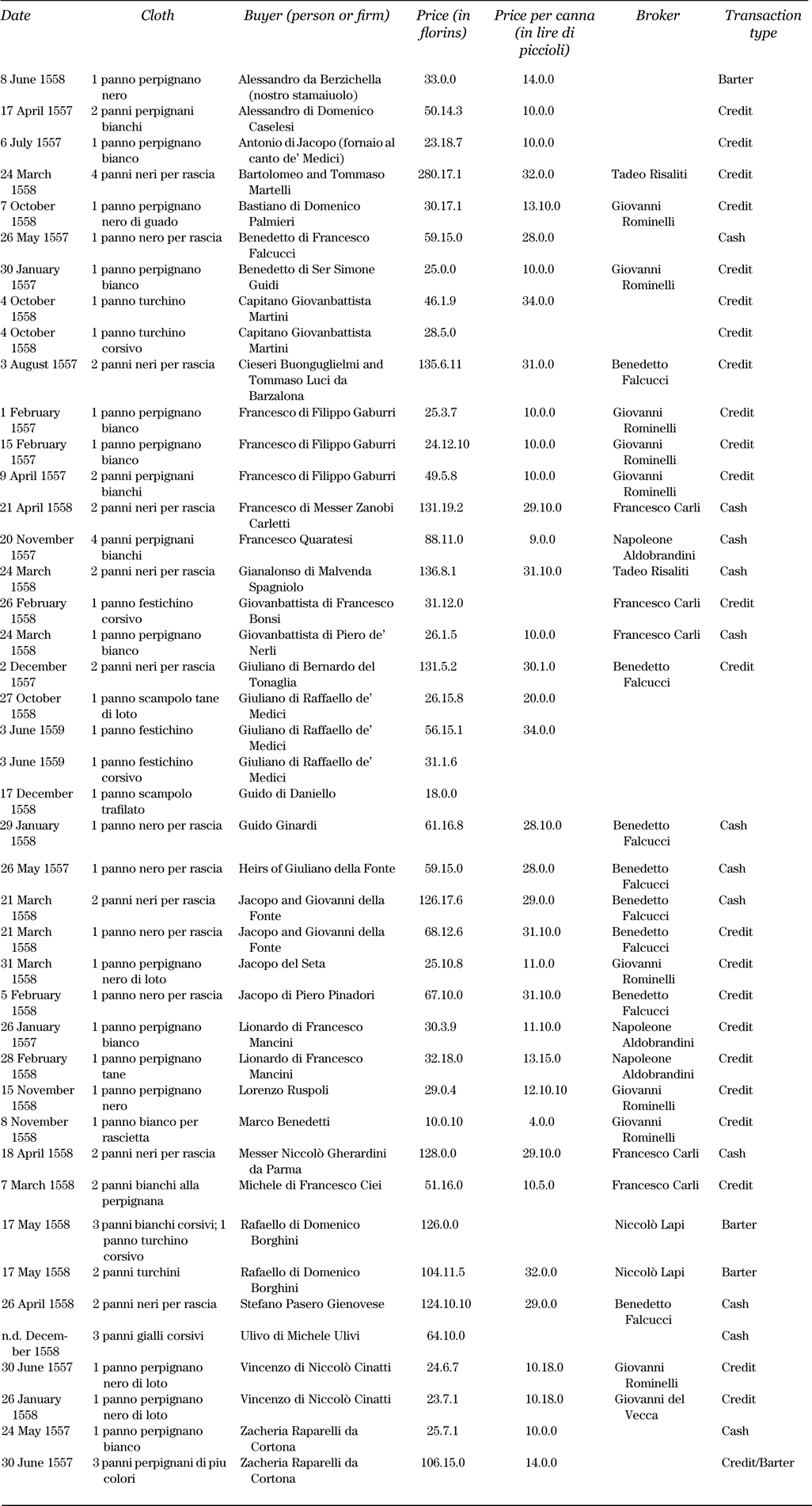

In the 1550s, the chief linear measures used in the Florentine cloth industry were the canna (pl. canne), roughly 2.33 meters or 2.55 yards in length, and the braccio (pl. braccia), about 58 centimeters or 23 inches, with four braccia combining to equal one canna. And wool manufacturers usually sold their product by the panno (pl. panni), with the whole woolen cloth, which varied in length, often at a rate expressed in lire di piccioli per canna (Table 4 and Figure 13).

Figure 13. Cloth sold by month and type, 1558–1561. Firm of Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione B. (Source: Ms. 568 v.11 [14], Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

Table 4 Cloth Sales of a Medici Firm

Francesco di Giuliano de’ Medici and Co., ragione A, 1556–1558

Source: Ms. 557-8, Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.

So, for example, the Medici firm's first cloth sale on January 30, 1557, was to the firm of Benedetto di Ser Simone Guidi and Co., linaiuoli (manufacturers of linens), for one panno 17 canne 2 braccia in length at the price of 10 lire di piccioli per canna, or 175 total, equivalent to 25 florins.Footnote 85 Assessing a loss of f.105 s.3 d.4, the firm sold the cloths it produced at the combined price of f.2970 s.15 d.9.Footnote 86 Of this, f.191 s.17 d.9 (6.46 percent) represented cloth sold “by the cut [a taglio]” (i.e., in small pieces to various buyers) or by bulk weight, with the rest—some sixty-seven cloths—sold by the panno to thirty-one firms or persons with accounts in the firm's ledger. More than a third of the cloths (twenty-three cloths, or 34.33 percent) were black rascie sold for an average of l.30 s.4 d.0 per canna, and a quarter (seventeen cloths, or 25.37 percent) were undyed or white perpignani sold for an average of l.9 s.17 d.7. The remaining 40 percent of those sold were cloths—sometimes coarse (corsivo), sometimes shorter than regulation size (scampolo)—of various colors: blacks (nero, nero di guado, nero di loto), blues (turchino, biadetto), tawny (tanè), green (festichino), yellow (giallo), and purple (paonazzo). Six panni (nearly 9 percent of all the cloths sold) were bartered in exchange for Spanish wool; 20 panni (nearly 30 percent) were sold for cash; and 36 panni (nearly 54 percent) were sold on credit. Credit transactions were of three basic types: those requiring payment in equal monthly or weekly installments; in full at the end of a fixed period; or in two or three equal monthly payments at the end of a fixed period. The sales of 73 percent of the sold panni were brokered by a broker (sensale) or middleman (mezzano) and the firm paid a total of f.7 s.15 in brokerage fees (senserie).Footnote 87 The most prolific of the middlemen, Benedetto Falcucci, brokered the sale of more than half the firm's output of black rascie and purchased one himself. In the firm's account books, the language of cash and barter exchanges is simple. All of the former were recorded as “for cash [per li contantti]” and when the Medici and Raffaello di Domenico Borghini and Co. traded finished panni for five bales of wool they wrote in their Giornale only “to give in exchange for the Spanish wool gotten from them [per metere a rincontro della lana ispagniola avuta da lloro].” The language and varieties of credit exchanges were more complicated but nearly always more or less simple installment plans with no mention (in the firm's public books) of an interest payment. Francesco di Filippo Gaburri, for example, made three purchases and was required to repay the first two (f.49 s.16 d.5 combined) at a rate of 6 florins per month and the third at (f.49 s.5 d.8) at a rate of 8 florins per month. More common were plans involving staggered repayment after a term of n months (per tempo di mesi n), as in the case of the Spaniard Gianalonso di Malvenda, who was required to pay for his cloths in three equal monthly installments after a period of ten months.

Business Practices and the Threshold of Political Economy

The fine black rascie could mean the difference between a profitable wool enterprise and an unprofitable one, and in its subsequent period, the same firm—the highly profitable B ragione of Francesco di Giuliano's wool company, which operated from 1558 to 1561—produced and sold significantly more cloths. A higher percentage of them (80 percent) were black rascia (Figure 11), much as over 70 percent of his father's production, from 1531 to 1534, had comprised the middle-quality broadcloth sopramani, then the most profitable type of Florentine woolen (Figure 14).

Figure 14. Cloth sold by type, 1531–1534. Firm of Raffaello di Francesco de’ Medici and Co., ragione L. (Source: Ms. 554 [4], Selfridge collection, Medici Collection, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.)

The rascie, as we noted above, also briefly saved the Florentine wool industry but could not keep it afloat forever. By the turn of the seventeenth century, the Arte della Lana was complaining to Grand Duke Ferdinando I of Florentine producers attempting to pass off lower quality cloths as rascie, squeezed by growing Venetian competition for markets and, crucially, for the supply of fine Spanish wool, which increased prices and of which Cosimo I had already received complaints as early as 1573.Footnote 88

In the aftermath of their moment of success, however, the Florentine rascie also crossed the blurry threshold into theory from mere business-historical datum. In a chapter on “having in one's possession some mercantia di momento,” some commodity of particular or even unique value or quality, in his On the Causes of the Greatness of Cities, Botero mentions, of course, that the “best wool” comes only from “a few towns in Spain and England.” But “there are also excellent manufactures,” he notes, “that flourish in one place rather than another, either because of the quality of the water, the cleverness of the inhabitants, some secret method they employ, or some similar reason, such as the weapons of Damascus and Shiraz, the tapestries of Arras, the rascie of Florence, the velvets of Genoa, the brocades of Milan, the scarlet cloths of Venice.” The success of the rascie was the result not of the Arno's water but of a long-term convergence of management at the level of the entrepreneur, the guild, and the state.

Just as Machiavelli advised princes, so did Botero:

Above all he [the prince] must not permit the export of raw materials from his state, whether wool, silk, timber, metals or any other such thing. . . . The prince's revenues from the export of finished goods are much greater than from that of primary materials. . . . Taking account of this, in recent years the kings of France and England have forbidden the export of wool from their kingdoms, as the Catholic King [i.e., the king of Spain] later did too. But these prohibitions could not be obeyed at once, because those countries [provincie] abound in such incredible quantities of very fine wool that there were not enough skilled workers to use it all.Footnote 89

Botero's codification of political economy can, from this perspective, be seen as a crucial link between the successful business practices that drove the Italian Renaissance, on the one hand, and Serra's revolutionary theorization of economic phenomena, on the other. But if the insights here were new, the policies behind them were surely not: by the late 1400s numerous Castilian merchants (like Lopez Gallo) and other middlemen, like the Genoese traders who dominated the financial fairs at Medina del Campo, were resident in the city offering Castilian wool, but the Florentines, it is crucial to remember, had first been forced to turn to Spanish sources for fine raw wool only when English wool export duties on “aliens” were, beginning under Edward III, increased precipitously and wool prices were fixed to ensure that the cost would not be borne by English producers, which together reduced the Italian share of English wool sales from approximately 34 percent to 10 percent between 1370 and 1410.Footnote 90 Botero had centuries of models to follow, but, in many ways, his model princes were the contemporary Medici Grand Dukes of Tuscany, especially the first of them, Cosimo I, whom he called “a prince of outstanding judgment,” and his son Francesco, whose shared policy (“done most skillfully”) of attracting foreign skilled laborers served as a segue—in the first edition of his more famous The Reason of State (1589), the first work to use that expression in its title—for repurposing the argument, quoted at length immediately above, about prohibiting the export of raw materials from the Causes.Footnote 91 It is often hard to find the line between deserved praise and undue flattery in Renaissance writing about princes, and Medicean dirigisme under Cosimo I and Francesco has been little studied, but the best scholars have indeed highlighted its transformational ambition. Goldthwaite describes it as “an extraordinary policy, much ahead of its time, [that] clearly arose from Cosimo's initiatives and enthusiasm,” and Judith Brown characterizes it as “activism aimed at the transformation of the entire economy,” a full-fledged “political economy.”Footnote 92

Immediately after noting the “profound silence” of Italian Renaissance thinkers on political economy, Hume declared that “the great opulence, grandeur, and military achievements of the two maritime powers”—meaning the Dutch and the English—“seem first to have instructed mankind in the importance of an extensive commerce.”Footnote 93 But were those who first instructed mankind themselves without instructors? Were the Dutch and English really autodidacts? If not, who had taught them? And in what? The answer was known long before Hume, and was later powerfully explained by the German historical economist Gustav von Schmoller in 1884: “what, to each in its time, gave riches and superiority first to Milan, Venice, Florence, and Genoa; then, later, to Spain and Portugal; and now to Holland, France, and England . . . was a state policy in economic matters [eine staatliche Wirtschaftspolitik]”—an applied political economy first theorized and codified in the late Italian Renaissance by thinkers ignored by Hume; thinkers in scholastic, Counter Reformation, anti-Machiavellian, and Reason of State contexts rather than republican and humanist and, later, liberal ones; thinkers for whom wealth and virtue were natural partners; thinkers who drew their lessons not from the ancients, as Machiavelli had professed, but from the successful business practices and government policies of their time. Footnote 94 That said, much suggests that these insights were even more widespread than that. For Florentines seem to have been eminently aware of the importance of measures to protect and encourage domestic manufactures throughout the Renaissance. Already in 1458, a Florentine commission declared that the city had “became powerful and great through her industries and business, and thanks to these it defended itself from all oppression.”Footnote 95 And even the humanist Aurelio Lippo Brandolini would write, in his Republics and Kingdoms Compared (c. 1490), of how Florence could protect its “empire” only with “the help of large duties” on trade and by prohibiting the “importation” of goods that “we ourselves manufacture, all woolens and silks . . . so that we can sell our own, and to prevent foreign wares bringing down the price or reputation of ours.” This because, as Brandolini quoted the Roman playwright Terence, “everyone prefers his own betterment to another's.”Footnote 96

In line with Hegel's frequently quoted dictum that “the owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk,” the historical mechanisms of Italy's success were, however, only codified politically and theorized economically once decline already had set in and the center of gravity in the European economy had begun to move north and west. Soon enough, Italian writers themselves took note of how England and the Low Countries had come to beat them at their own game by adopting precisely the measures argued for by Botero, working their own raw materials and embracing import substitution. As Fernand Braudel concluded in his Out of Italy, the city-states of the peninsula declined also by virtue of teaching the rest of Europe their practices, or what he called “le Modèle italien.”Footnote 97 There are few better lenses for appreciating this process than that of Florentine woolen manufactures and the origins of political economy.

As such, a broadening of the traditional context for considering the history of political economy to include not only texts but the worlds of business enterprise as well as guild and government policies suggests fertile fields for future inquiry. For if Pocock delineated a powerful “Atlantic Republican Tradition” originating in Renaissance Florence, the extraordinary popularity of Botero's work in the European world— “the Italian tradition” more broadly—allows us to adumbrate a different but no less consequential conceptual arc (one that, because of its explicitly “economic” nature, Hont might even have called “modern”) similarly bridging Renaissance Italy to the rise of Britain, the birth of the United States, and the world that we inhabit.Footnote 98 Through careful readers such as Francis Bacon, William Petty, and Veit Ludwig von Seckendorff, Botero's original observation about the superiority of industry in Renaissance Florence and the importance of nurturing domestic manufactures to secure greatness in a world of relentless international competition was sequentially institutionalized in the theories, policies, and business strategies of emerging powers everywhere, from the Germanic world of Cameralism and John Cary's England to Alexander Hamilton's nascent United States of America and, eventually, well beyond to our day and age. To engage with the political economy of the Italian Renaissance is to engage with the development of our world as we know it. For better and for worse, we are still crossing Botero's bridge, its end perennially out of sight.Footnote 99

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S000768052000001X