Congenital cardiac disease is the malformation of the heart or the large blood vessels. The reported prevalence of congenital cardiac disease varies between 4 and 10 per 1000 live births.Reference Hoffman and Kaplan1 The formation of the human heart takes place during weeks 3–9 of foetal development. The process is an intricate one that can be influenced by both genetic and environmental factors. A periconceptional supplement of multiple vitamins, especially folic acid, could significantly reduce the incidence of congenital cardiac disease.Reference Goh, Bollano, Einarson and Koren2, Reference Botto and Mulinare3 The mechanism by which folic acid exerts its protective effect is largely unclear, and therefore, the teratogenic process that results from folate insufficiency is related to hyperhomocysteinaemia, an independent risk factor for congenital cardiac disease.Reference Jenkins, Correa and Feinstein4

Homocysteine is a type of thioalcohol amino acid, which is a comitant metabolic product of methionine demethylation and transsulphuration. An abnormality of homocysteine metabolism is shown to induce cardiac defects in developing chick embryos and folate-deficient mice models.Reference Boot, Steegers-Theunissen, Poelmann, van Iperen and Gittenberger-de Groot5, Reference Li, Pickell, Liu, Wu, Cohn and Rozen6 MTHFR and MTHFD are two important enzymes involved in the homocysteine metabolism. MTHFR have an important role in catalysing the conversion of 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate, which acts as a methyl group donor-induced homocysteine remethylation to methionine.Reference Frosst, Blom and Milos7 MTHFD is a trifunctional enzyme that catalyses the interconversion of three forms of one-carbon substituted tetrahydrofolate, the active form of folic acid. The one-carbon folates generated by MTHFD are used for the synthesis of purines, thymidylate, and serine, and to support the methylation cycle through the regeneration of methionine from homocysteine.Reference Hol, van der Put and Geurds8, Reference Christensen, Patel, Kuzmanov, Mejia and Mackenzie9 The MTHFD gene defects might lead to a decrease in enzyme activity that influences the methylation cycle through the regeneration of methionine from homocysteine and affects the supply of 10-formyltetrahydrofolate required for purine synthesis. These further affect the rate of DNA synthesis and the rate of cell doubling, which are likely to have a major impact on pregnancy and embryonic development.Reference Parle-McDermott, Kirke and Mills10, Reference Shi, Caprau, Romitti, Christensen and Murray11

The MTHFR gene has at least two functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms, c.677C>T and c.1298A>C. The MTHFR c.677C>T allele is associated with reduced enzyme activity, decreased concentrations of folate in serum, plasma, and red blood cells, and increased plasma total homocysteine concentrations.Reference Vizcaino, Diez-Ewald, Herrmann, Schuster, Torres-Guerra and Arteaga-Vizcaino12 Meanwhile, MTHFR c.1298A>C leads to lower enzyme activity and acts as a risk factor for hyperhomocysteinaemia.Reference Weisberg, Jacques and Selhub13 Rady et alReference Rady, Szucs and Grady14 identified another non-synonymous single-nucleotide polymorphism of the MTHFR gene, c.1793G>A, but its function was unknown. Earlier studies showed inconsistent results between MTHFR c.677C>T and c.1298A>C polymorphisms, and congenital cardiac disease.Reference van Beynum, den Heijer, Blom and Kapusta15–Reference van Driel, Verkleij-Hagoort and de Jonge20 However, no data were available for MTHFR c.1793G>A genotype and risk of congenital cardiac disease. Researchers had identified several potentially functional single-nucleotide polymorphisms of MTHFD, such as c.1958G>AReference Hol, van der Put and Geurds8 and c.401C>TReference Brody, Conley and Cox21, and c.1958G>A reported the influence of folate and homocysteine levels as well as congenital cardiac disease risk.Reference Cheng, Zhu, Dao, Li and Li22

This study aimed to investigate the role of the five single-nucleotide polymorphisms of MTHFR and MTHFD in susceptibility to congenital cardiac disease in a Chinese population.

Materials and methods

Study population

The institutional review board of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China approved the study. The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University and Nanjing Children’s Hospital, Nanjing, China consecutively recruited congenital cardiac disease cases between March, 2006 and July, 2008. Surgical operations confirmed all cases that had non-syndromic congenital cardiac disease diagnosed by ultrasound. Cases with structural malformations involving another organ system or known chromosomal abnormalities were excluded. Exclusion criteria also included a positive family history of congenital cardiac disease in a first-degree relative that consists of parents, siblings, and children, maternal diabetes mellitus, phenyl ketonuria, maternal teratogen exposures, for example, pesticides and organic solvents, and maternal therapeutic drugs, including folate antagonist, and exposures during the intrauterine period. Information about regular multi-vitamin supplements, including regular folic acid intake during a period from 3 months before pregnancy to the first 3 months of pregnancy, rubella, influenza, and any febrile illnesses during pregnancy was also obtained. Control patients were non-congenital cardiac disease and age- and gender-matched outpatients in the same geographic area during the same time period as congenital cardiac disease patients. Most of these patients had a diagnosis of trauma or infection. The control group excluded any patients with known congenital anomalies. Both congenital cardiac disease and control patients were genetically unrelated ethnic Han Chinese. Using a structured questionnaire, trained interviewers personally interviewed patients and/or their parents after directly obtaining informed consent. After the interview, approximately 2 millilitres of venous blood were collected from each patient. This study used a cross-validated two-stage design to increase the efficiency of the comparison.

In all, 502 congenital cardiac disease cases and 527 controls were included during a period between March, 2006 and July, 2007 and grouped as stage I. The remaining 531 congenital cardiac disease cases and 540 controls were recruited between August, 2007 and July, 2008 and grouped as stage II samples.

Laboratory assays

Genomic DNA was isolated from leucocytes of venous blood by proteinase K digestion followed by phenol–chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The genotyping assays for the five single-nucleotide polymorphisms of MTHFR – c.677C>T, c.1298A>C and c.1793G>A – and MTHFD – c.1958G>A and c.401C>T – were previously described.Reference Wang, Ke and Chen23, Reference Shen, Newmann and Hu24 Briefly, the polymerase chain reaction primer pairs were c.677C>T F: 5′-TGAAGGAGAAGGTGTCTGCGGGA-3′, R: 5′-AGGACGGTGCGGTGAGAGTG-3′; c.1298A>C F: 5′-CTTTGGGGAGCTGAAGGACTACTAC-3′, R: 5′-CACTTTGTGACCATTCCGGTTTG-3′; c.1793G>A F: 5′- CTCTGTGTGTGTGTGCATGTGTGCG-3′, R: 5′-GGGACAGGAGTGGCTCCAACGCAGG-3′; c.1958G>A F: 5′-CATTCCAATGTCTGCTCCAA-3′, R: 5′-GTTTCCACAGGGCACTCC-3′; c.401C>T F: 5′-GGCGTACAAGGAATGAAAC-3′, R: 5′-GGATGTGGATGGGTAAGTG-3′. The 15 microlitres of polymerase chain reaction mixture contained approximately 20 nanograms of genomic DNA, 12.5 picomoles of each primer, 0.1 millimolar of each dNTP, 1 × polymerase chain reaction buffer – 50 millimolars of KCl, 10 millimolars of Tris HCl, and 0.1% Triton X-100 – 1.5 millimolars of MgCl2, and 1.0 unit of Taq polymerase. The polymerase chain reaction profile consisted of an initial melting step of 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 30 seconds, 67°C for c.677C>T or 62°C for c.1298A>C or 69°C for c.1793G>A or 66°C for c.1958G>A or 55°C for c.401C>T for 40 seconds and 72°C for 45 seconds, and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 minutes. We used the restriction enzymes HinfI, MboII, BsrbI, HpaII, and BsmaI (New England BioLabs, Beverly, Massachusetts, United States of America) to distinguish the c.677C>T, c.1298A>C, c.1793G>A, c.1958G>A, and c.401C>T genotypes, respectively. We also performed genotyping blindly and assayed approximately equal numbers of congenital cardiac disease cases and controls in each 96-well polymerase chain reaction plate with a positive control of a DNA sample with known heterozygous genotype. In the event of consensus on the tested genotype not being reached, two research assistants independently performed the repeated assays to achieve 100% concordance.

Statistical analyses

We evaluated differences in the distributions of selected variables and frequencies of the genotypes of MTHFR and MTHFD polymorphisms between cases and controls using the chi-square or Student’s t-test. We also estimated the associations between the genotypes and the risk of congenital cardiac disease by adjusted odds ratio and their 95% confidence interval from logistic regression analyses, with adjustment for sex. A goodness-of-fit chi-square test to compare the observed genotype frequencies tested the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium with the expected ones among control subjects. All of the statistical analyses were performed with Statistical Analysis System software (v.9.1.3e; SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, United States of America).

Results

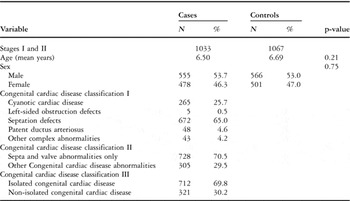

Of the 1033 congenital cardiac disease patients, 265 (25.7%) were with cyanotic cardiac disease, 5 (0.5%) were with left-sided obstruction defects, 672 (65.0%) were with septation defects, 48 (4.6%) were with patent ductus arteriosus; Table 1 shows other classifications.

Table 1 Distributions of selected variables in congenital cardiac disease cases and controls.

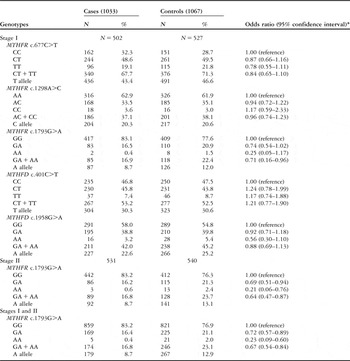

The MTHFR – c.677C>T, c.1298A>C, and c.1793G>A – and MTHFD – c.1958G>A and c.401C>T – genotype distributions in congenital cardiac disease; Table 2 shows the control patients. The observed genotype frequencies for these five polymorphisms in the controls were all in Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium. In stage I, we found the MTHFR c.1793GA/AA genotypes to be associated with a reduced risk of congenital cardiac disease, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.71 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.16–0.96 (p = 0.03), compared with the c.1793GG wild-type homozygote. There were no associations between the other four variants and congenital cardiac disease risk. In stage II, a similar association was found between congenital cardiac disease risk and MTHFR c.1793GA/AA, compared with the c.1793GG genotype, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.64 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.47–0.87 (p = 0.003). By considering both stages, the association between congenital cardiac disease risk and variant genotypes of MTHFR c.1793GA/AA, we found a 33% decreased risk of congenital cardiac disease, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.67 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.54–0.84 for c.1793AA (p = 0.0004; Table 2).

Table 2 Logistic regression analyses of associations between MTHFR c.677C>T, c.1298A>C, and c.1793G>A, and MTHFD c.1958G>A and c.401C>T polymorphisms and risk of congenital cardiac disease.

*Adjusted by age and sex

By dividing congenital cardiac disease patients into subgroups according to the five variants in stage I, logistic regression analysis revealed that MTHFR c.1793GA/AA had a significantly protective effect in the isolated ventricle septal defect, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.54 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.35–0.81, compared with the c.1793GG genotype, and c.1298CC variant homozygote was associated with a 3.96-fold increased congenital cardiac disease risk, compared with the c.1298AA wild-type homozygote in the isolated ostium secundum atrial septal defect, with an adjusted odds ratio of 3.96 and a 95% confidence interval of 1.20–13.05.

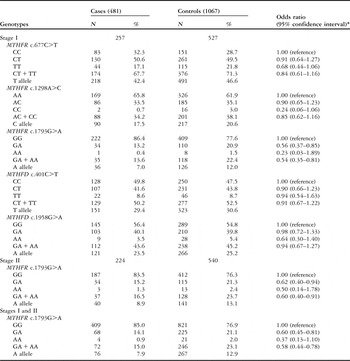

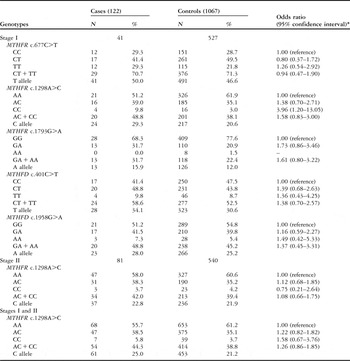

To further confirm the associations, we performed a replication study in stage II patients, including 224 isolated ventricle septal defect patients and 540 controls for MTHFR c.1793G>A, and 81 isolated ostium secundum atrial septal defect patients and 540 controls for MTHFR c.1298A>C. We found a similar association in MTHFR c.1793G>A, but not MTHFR c.1298A>C. By considering the two stages, the MTHFR c.1793GA/AA genotypes had a 42% reduced risk of the isolated ventricle septal defect, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.58 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.44–0.78, whereas the MTHFR c.1298CC genotype had no significant effect on the isolated ostium secundum atrial septal defect, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.58 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.67–3.76 (Tables 3 and 4). Furthermore, the stratified analysis of the isolated ventricle septal defect revealed a significant protective effect of MTHFR c.1793GA/AA on the isolated perimembranous ventricular septal defect, with an adjusted odds ratio of 0.60 and a 95% confidence interval of 0.43–0.83, compared with the c.1793GG genotype (Table 5).

Table 3 Logistic regression analyses of associations between MTHFR c.677C>T, c.1298A>C, and c.1793G>A and MTHFD c.1958G>A and c.401C>T polymorphisms and risk of isolated ventricle septal defect.

*Adjusted by age and sex

Table 4 Logistic regression analyses of associations between MTHFR c.677C>T, c.1298A>C, and c.1793G>A and MTHFD c.1958G>A and c.401C>T polymorphisms and risk of isolated ostium secundum atrial septal defect.

*Adjusted by age and sex

Table 5 Logistic regression analyses of associations between MTHFR c.1793G>A polymorphism and risk of the subgroup of isolated ventricle septal defect.

*Adjusted by age and sex

Discussion

Goh et alReference Goh, Bollano, Einarson and Koren2 have reported an association between the dietary intake of folic acid and the risk of congenital cardiac disease. A striking finding was that regular periconceptional folic acid use, from 3 months before pregnancy through the first 3 months of pregnancy, could prevent approximately 25% of major cardiac defects.Reference Botto and Mulinare3 It is known that folate provides methyl groups required for intracellular methylation reactions and de novo deoxynucleotide synthesis. MTHFR and MTHFD are two central regulatory enzymes in the folate metabolism and it is likely that not only folate deficiency, but also functional polymorphisms in genes associated with the folate-mediated homocysteine pathway, may contribute to congenital cardiac disease risk.Reference Shaw, Iovannisci and Yang25–Reference Verkleij-Haqoort, Bliek, Sayed-Tabatabaei, Ursem, Steeqers and Steegers-Theunissen28

Earlier studies have discrepancy conclusions in relation to MTHFR c.677C>T, c.1298A>C polymorphisms, and risk of congenital cardiac disease.Reference van Beynum, den Heijer, Blom and Kapusta15 A meta-analysis of 13 retrospective studies showed that only five independent studies reported an association between MTHFR c.677C>T polymorphism and different congenital cardiac disease types and others did not find the relationship. This meta-analysis found no substantial evidence for any association between congenital cardiac disease risk and the MTHFR c.677C>T polymorphism.Reference van Beynum, den Heijer, Blom and Kapusta15 Our results are consistent with the analysis. Thus far, five studies reported on the association between the MTHFR c.1298A>C polymorphism and congenital cardiac disease. Hobbs et alReference Hobbs, Cleves, Melnyk, Zhao and James16 reported a protective effect of the MTHFR c.1298 C allele on congenital cardiac disease risk. Additional independent studies showed no significant association between the MTHFR c.1298 A>C polymorphism and the risk of congenital cardiac disease in the other four studies.Reference Storti, Vittorini and Lascone17–Reference van Driel, Verkleij-Hagoort and de Jonge20

In this study, we investigated the associations between MTHFR c.677C>T, c.1298A>C, c.1793G>A and MTHFD c.1958G>A, c.401C>T polymorphisms, and congenital cardiac disease risk in Chinese population. The variant genotypes of MTHFR c.1793G>A, but not MTHFR c.1298A>C, were found to be associated with a decreased risk of congenital cardiac disease, significantly in patients with isolated perimembranous ventricle septal defect.

Differences in risk estimate for MTHFR polymorphisms in association with congenital cardiac disease might be caused by multiple factors, including aetiologic heterogeneity between populations, geographical variations of the studied populations, different selection of controls, study design, type of cardiac defects, and lack of information on potential effect modifiers. In this study, we conducted a two-stage design to validate the findings and reveal the substantial association between MTHFR c.1793G>A polymorphism and congenital cardiac disease. It is likely that MTHFR c.1793G>A is associated with increased enzyme activity, notwithstanding that it needs to be clarified in further studies. It is also possible that MTHFR c.1793G>A is not functional and might be linked with another casual variant that plays an important role in the aetiology of congenital cardiac disease.

Several limitations in this study need to be addressed. First, this study was a hospital-based case–control study and the hospitalised patients may not be representative of the general population. For example, congenital cardiac disease patients were collected from two large hospitals in Jiangsu province whose patients were prone to heavy cases, which may result in admission rate bias. Second, we failed to collect blood samples from patients’ parents, and therefore it was difficult to analyse whether congenital cardiac disease was associated with parents’ genetic background and folate levels during the pregnancy. Third, the functional relevance of MTHFR c.1793G>A is unclear, making it difficult to determine whether the polymorphism is casual loci or proxy. Finally, the sample size in this study was moderate, especially in stratifications, and therefore further studies with larger sample size are warranted to confirm the findings.

In conclusion, cardiac development is a complicated process, involving the expression of many genes at different times, spaces, and orders. The results of this study, MTHFR c.1793G>A, may be useful biomarkers for congenital cardiac disease, and could help to identify the risk populations for congenital cardiac disease.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30872544), the Jiangsu Province Natural Science Foundation (BK2006248, BK2009207), the Jiangsu Province Import Foreign Talent Program Grant (S2008320072), and the Jiangsu Top Expert Program in Six Professions (06-B-031). Jing Xu, Xiaohan Xu, Lei Xue and Yijiang Chen contributed equally to this study.