Introduction

During the last thirty years, national territorialization research about Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries has proliferated. Case studies of Czechoslovakia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Scotland, Switzerland, and Yugoslavia (Bassin Reference Bassin1999; Górny Reference Górny2013; Gugerli and Speich Reference Gugerli and Speich2002; Häkli Reference Häkli, Herb and Kaplan1999; Hansen Reference Hansen2015; Haslinger Reference Haslinger2010; Herb Reference Herb1996; Paasi Reference Paasi1995; Petronis Reference Petronis2007; Popova Reference Popova1999; Porter Reference Porter1992; Seegel Reference Seegel2012; Schweiger Reference Schweiger2014; Staliunas Reference Staliunas2015; Weber Reference Weber and Weber1991; White Reference White2000; Withers Reference Withers2001) support the universality of the argument that “Whatever else it may be, nationalism is always a struggle for control of land. […] The ‘land’ […] is intrinsic to the very concept of national identity” (Kaiser Reference Kaiser and Motyl2000, 316). Therefore, to imagine a nation means to differentiate it spatially (Cubitt Reference Cubitt and Cubitt1998, 6, 10) and provide it with distinct shape (Smith Reference Smith1969; Weber Reference Weber and Weber1991) and borders (Anderson Reference Anderson1991).

Recently, the case of Ukraine and Ukrainian national acquiring of a territory has attracted the attention of historians (Bilenky Reference Bilenky2012; Seegel Reference Seegel2012; Stebelsky Reference Stebelsky2011; Szporluk Reference Szporluk2008–Reference Szporluk2009). At the same time, one can not only enrich the pioneering accounts of the above-mentioned scholars with new data. These new and previously unnoticed details allow us to raise some crucial general methodological questions. Referring to the Ukrainian example and the story of the first published ethnographic map of Ukraine, in this article I argue that the story of a nation’s territorialization requires to be seen both from perspectives of mental geography and history of cartography. Moreover, cases similar to the Ukrainian one—situated in two or more imperial contexts—cannot be studied relying on sources from one empire only. The case of the first ethnographic map of Ukraine proves that once we combine the methods of history of cartography and of mental geography, widen the range of our documents by looking beyond the border between the Romanov and Habsburg empires, and make our narrative entangled and interdisciplinary, we might see its previously written story in a different light. Ukrainian activists in the Russian empire will emerge as unquestionably interested in the territorial extent of Ukrainian nation with Mykhailo Levchenko—not some anonymous intellectual from Lviv—being a probable author of the first published ethnographic map of Ukrainians. Contrary to existing scholarship (Padiuka Reference Padiuka2008, 437; Rovenchak Reference Rovenchak and Vavrychyn2000, 110; Seegel Reference Seegel2012, 195: Sossa Reference Sossa2007, 163; Symutina Reference Symutina1993, 25–27), I argue that the map, which appeared in Lviv at the end of 1861, was probably created in Russian Ukraine—not in Galicia—and was published in the Habsburg empire for unknown reasons.

Lviv—Habsburg Empire: A Conventional Story

In 1861, a serial “Lvovite. A handy and household calendar for the common year of 1861” (Lvovianyn. Pryruchnyi i hospodarskyi mesiatseslov na rik zvychainyi 1861) was launched in Lviv. Published by the then head of the Stauropegion Institute’s publishing house, Mykhailo Mykolaiovych Kossak (Symutina Reference Symutina1993, 25), it was continued annually until 1863. The three issues of Lvovianyn included mixed information on religious holidays, recent governmental instructions, postal prices, agricultural and household recommendations, statistics of the Habsburg Ruthenians and their ethnographic description, and literary works. An important detail about the latter was a relative abundance of texts written originally in the Romanov empire. Thus, the readers of the Austrian Lvovianyn could read the poems or stories by Taras Shevchenko or Hryhorii Kvitka-Osnovianenko, who lived in the Russian empire.

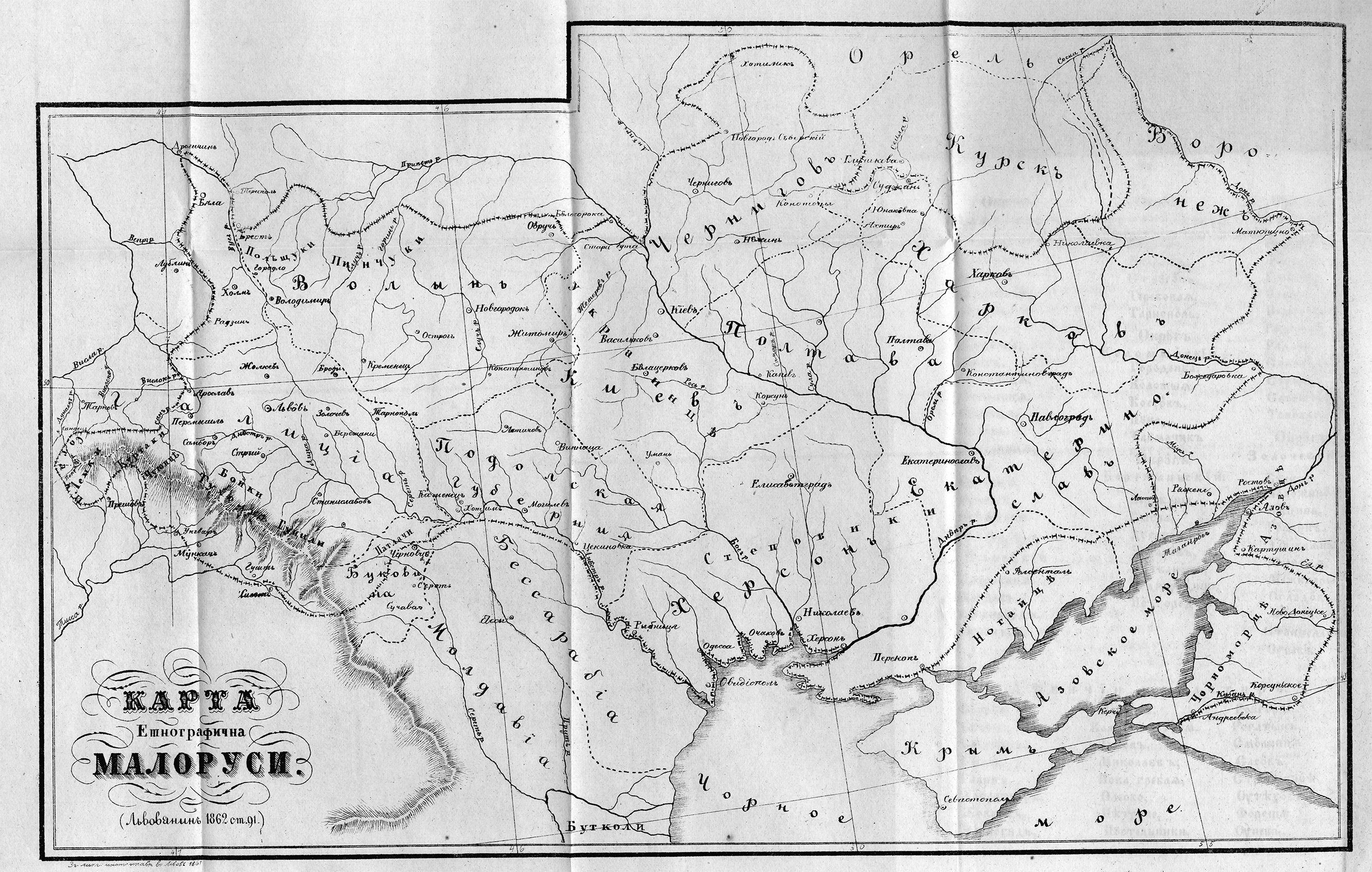

One of the interesting publications, which appeared in Lvovianyn, was an unsigned “Ethnographic map of Little Russians” (Karta etnohrafichna Malorusy) (Figure 1). The date at its bottom signified that the map was printed separately from the calendar in 1861. Taking into consideration its inclusion into the 1862 issue, one might hypothesize that it probably appeared at the end of 1861.

Figure 1. Ethnographic map of Little Russians (Karta etnohrafichna Malorusy). Printed in Stauropegion Institute’s printing house in 1861, published in Lvovianyn in 1862.

This black and white image presented a continuous territory populated by “Little Russians” in the Habsburg, Romanov, and Ottoman empires, demarcated by a dotted border, which more or less followed a border of “Little Russians” from the 1842 “Slavonic Ethnography” (Slovanský národopis) and “Slavonic Geography” (Slovanský Zeměvid) by Pavel Jozef Šafařik (Padiuka Reference Padiuka2008, 437–438; Rovenchak Reference Rovenchak and Vavrychyn2000, 110; Symutina Reference Symutina1993, 26). The map acquainted the readers with the current administrative structure and regional divisions of “Little Russians,” indicating towns, rivers, and mountains of this territory. The latitude and longitude lines could have helped the readers to locate all the data in space referring to Ferro line as the prime meridian. Even though it depicted none of the existing interstate borders, according to the map Ukrainians lived on the territory from Poprad (in the Habsburg empire) to the western districts of Voronezh province and Kuban (in the Romanov empire) and Dobruja (in the Ottoman empire). Curiously, it also presented their main regional divisions by inscribing the names of “people from Polissia” (polishchuky), “people from Pinsk area” (pinchuky), “Ukrainians” (ukraintsi) from the Kyiv province, “steppe people” (stepovyky) from the Kherson province, “Black Sea people” (chornomortsi) from Kuban, and a number of small regional groups in the Carpathian mountains (sotaky, lemky, kurtaky, chukhontsi, tukholtsi, boiky, hutsuly), Bukovyna (patlachi), and Dobruja (butkoly). The importance of the map, however, lay not in its scientific merits—as far as we know, it did not become a blueprint for subsequent similar images. Yet the map is considered by many to be the first ethnographic map of Ukrainians. Thus, it has justifiably called the attention of historians of cartography (Padiuka Reference Padiuka2008, 437; Rovenchak Reference Rovenchak and Vavrychyn2000, 110; Seegel Reference Seegel2012, 195; Sossa Reference Sossa2007, 163; Symutina Reference Symutina1993, 25–27).

The map did not stand alone in the calendar but was an appendix to the unsigned article “Ruthenians. Fragments of a larger historic-ethnographic text, which is currently being prepared for a publication” (Rusyny. Uryvkovi vypysy iz bilshoho do pechatania pryhotovliaiuchoho sia istorychno-etnografichnoho sochineniia). As the author of the text put it, “the article above is accompanied with a map” (Rusyny 1862, 105). This story described “Ruthenians,” where they lived, their regional divisions, and their history. Both the text and the map were supposedly created under a substantial influence of works by P.J. Šafařik. This hypothesis is supported by the author’s rendering of the name of the central Ukrainian town of Poltava: similarly to the Czech Slavist, the unknown author of the article in Lvovianyn transcribed this toponym as “Pivtava” (Rusyny 1862, 91). Supposedly, the author of the article was Mykhailo Kossak himself, who did not sign it, presumably, because he did not want to “advertise his authorship until the work was completely finished” (Symutina Reference Symutina1993, 25). It is only by changing the methodology of our research, extending the range of our sources, and bringing the Romanov empire into the focus that we will be able to substantially refine this conventional narrative of the appearance of the map from Lvovianyn. New geography provides the map (and Ukrainian nationalism) with a new genealogy.

Zhytomyr, Maiorske, Saint Petersburg, and the Romanov Empire: A Revised Account

Kostiantyn Mykhalchuk was a Ukrainian linguist famous for his 1871 “Map of Southern Russian dialects and vernaculars” (Karta yuzhnorusskikh narechiy i govorov). Published in 1877, this map became the most authoritative 19th century ethnographic map of Ukrainians. In the beginning of February 1862, however, Mykhalchuk’s house in the Volhynia province was searched by a local policeman on suspicion of his “dissemination of dangerous books among the local peasants.” Indeed, the policeman dug up more than 300 copies of 23 books, although all of them were published with a censorship’s consent (TsDIAK Footnote 1862, 1–3).Footnote 1 Importantly for the story of Ukrainian national territorialization, the policeman also made a second significant finding. Among Mykhalchuk’s papers, he discovered “a handwritten map of some Russian provinces under the name of ‘Ukrainians or Ruthenians’” (rukopisnaya karta nekotorym rossiyskim guberniyam pod nazvaniem “ukraintsy abo Rusiny”) (TsDIAK Footnote 1862, 3).Footnote 2 The map was confiscated and Mykhalchuk was put under surveillance.

Even though no traces of this map have yet been discovered, its story makes one certain that already in the beginning of 1862 Russian Ukrainian activists were at least interested in the territorial extent of their nation and had some handwritten maps of Ukrainian national territory in their possession. One more proof of this spatial interest of Russian Ukrainian activists was a case revealed during the interrogation of Volodymyr Antonovych approximately a year before the search in Mykhalchuk’s house. A future grey eminence of Ukrainian national movement in the Romanov empire, in 1861 Antonovych told the policemen that from 1858–1859 he traveled around the Kingdom of Poland, Kyiv, Kherson, and Katerynoslav provinces, “wishing to get acquainted with the folk way of life, language, and customs” (TsDIAK Footnote 1860–Footnote 1862, 234).Footnote 3 One of the most remarkable objects found during a search in Antonovych’s house was a map of part of the Lublin province, “drawn by him one day while studying Šafařik to indicate the border between the Southern Rus’ people (yuzhno-russami) and Poles” (TsDIAK Footnote 1860–Footnote 1862, 235, 258).Footnote 4

Alongside the clandestine cartographic activity of young students of the Kyiv University, the beginning of 1860s was of great importance for the territorialization of the Ukrainian national idea for other reasons. The undoubtedly major Ukrainian intellectual endeavor of the period was the journal “Foundation” (Osnova), published by Vasyl Bilozersky in Saint Petersburg in 1861–1863. Its first book was prepared for publication in December 1860 (Dudko Reference Dudko2013, 280) and appeared in print in January 1861, which means that all its articles were written much earlier. Aside from its tremendous importance as a medium for discussing Ukrainian language, literature, and history, Osnova also paid the utmost attention to Ukrainian national territorialization, and, thus, might be rightfully called a Ukrainian “National Geographic” of the time. In addition to publishing special articles dealing with careful delineation of Ukrainian national territory, its editor also vigorously promoted and printed travelogues “around Ukraine,” discussed Ukrainian geographic nomenclature, and subtly tried to popularize the name of “Ukraine” instead of the more common “Southern” or “Little Russia” (See Kotenko [Reference Kotenko2012] on Osnova and its attempts to territorialize the Ukrainian nation).

The significance of national territorialization for Ukrainian activists of the time was underlined by the publication of one of the most vocal territorial texts in the very first book of Osnova. The text, titled “The present-day places of living and local names of Ruthenians” (Mesta zhitelstva i mestnye nazvaniya rusinov v nastoyashchee vremya), was written by retired army officer Mykhailo Levchenko. Over four pages, Levchenko described the territory populated by the continuous mass of “the Southern Rus’ people, Little Russians, or, more correctly, the Ruthenians” (Levchenko Reference Levchenko1861, 263). According to Levchenko, they lived as a solid mass in various locations: the Poltava, Kharkiv, Kyiv, Volhynia, and Podillia provinces; the Land of the Black Sea Cossacks; parts of the Chernihiv, Kursk, Voronezh, Katerynoslav, Kherson, Tavria, Lublin and Hrodna provinces; the Bessarabian region and Azov city municipality; in Galicia, Hungary, and Bukovyna; on the Volga River; in Siberia; behind the Baikal; and in Dobruja (Levchenko Reference Levchenko1861, 263–264).

All these Ukrainians were further divided by Levchenko into regional groups: Hetmanate people (hetmantsi) in the Chernihiv province, steppe people (stepovyky) in the Poltava and Katerynoslav provinces, Ukrainians (ukraintsi) in the Kyiv province, Polish people (polshchaky) in the Podillia province, Polissia people (polishchuky), long-haired people (patlachi) in Bessarabia and Bukovyna, Pinsk people (pinchuky) in the Grodno province, Ruthenians (rusyny) in the Lublin province, and various other groups in the Carpathian mountains (sotaky, lemky, kurtaky, chukhontsi, tukholtsi, boiky, hutsuly), Bukovyna (patlachi), and Dobruja (butkoly) (Levchenko Reference Levchenko1861, 264).

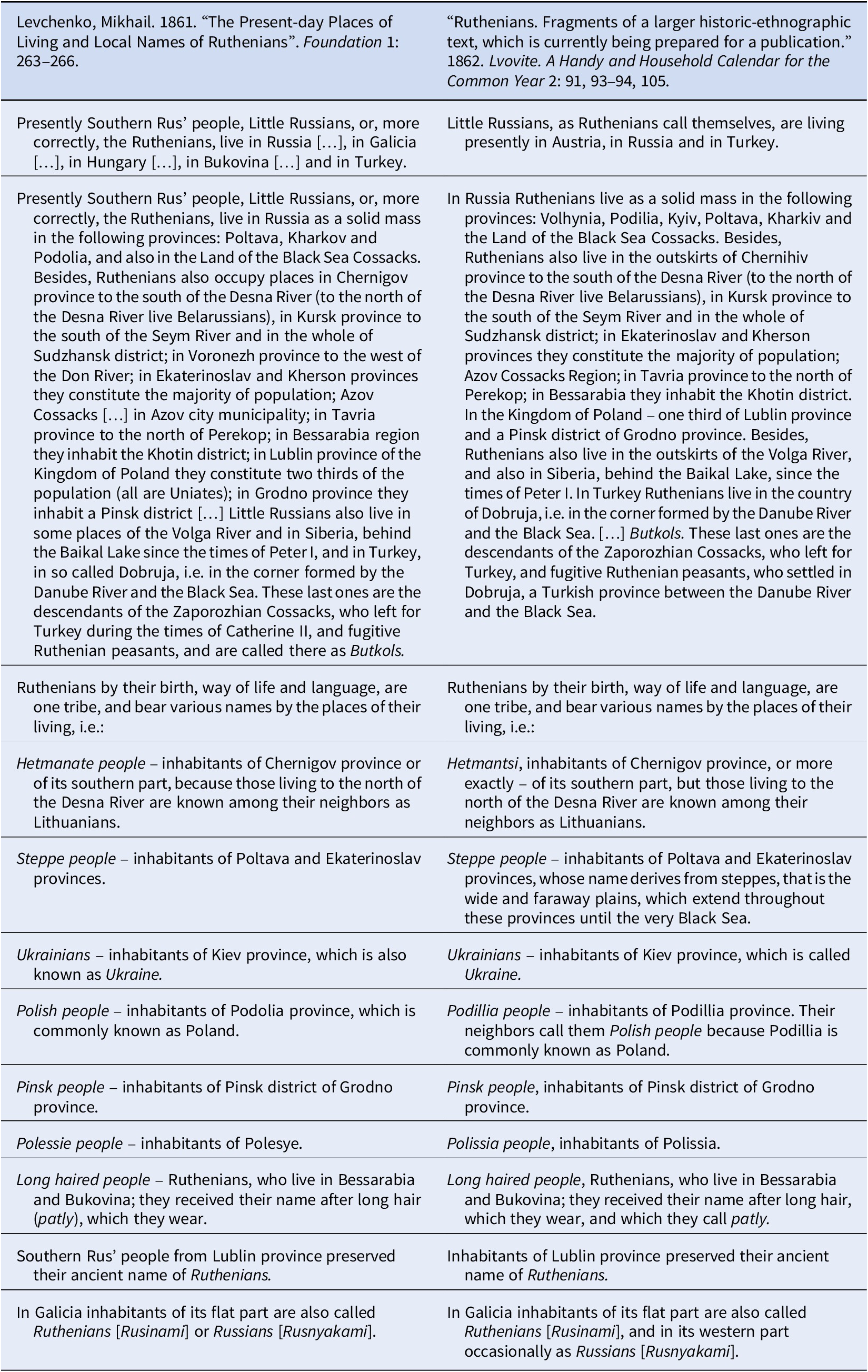

“Hetmanate people,” “steppe people,” “Ukrainians,” “Polish people,” “Polissia people,” “long-haired people,” “Pinsk people,” “Ruthenians”—the same regional divisions of “Ruthenians” were described and presented visually by the author(s) of the text and map in “Lvovite.” Close reading and comparison of both texts from Lvovianyn and Osnova reveals a striking similarity between the two: the article published in Lviv in 1862 supplemented the text published in Saint Petersburg in 1861 only in those cases when the Galician audience of Lvovianyn might not have understood some concept well known to Osnova’s reader in the Russian empire (Tables 1 and 2). For instance, it complemented Levchenko’s entry on the steppe people—that “Steppe people [are] the inhabitants of Poltava and Ekaterinoslav provinces” (Levchenko Reference Levchenko1861, 264)—with a short explanation of what the steppes were—that “Steppe people [are] the inhabitants of the Poltava and Ekaterinoslav provinces whose name derives from steppes, that is the wide and faraway plains, which extend throughout these provinces until the very Black Sea” (Rusyny 1862, 93–94).

Table 1. Comparative table of texts published in Saint Petersburg (1861) and Lviv (1862) in original languages.

Table 2. Comparative table of texts published in Saint Petersburg (1861) and Lviv (1862) in English.

This intertextual analysis of the text published in Saint Petersburg in 1861 and the text published in Lviv in 1862, allows us to reach at least one preliminary conclusion: an article, which was initially written and published in the Russian empire and had to overcome the regional differences of different parts of one “Ruthenian” nation, was at least carefully read and reworked in Galicia. Levchenko’s text seems to have been at least the main source of inspiration for the author of the map published in Lviv, and not P. J. Šafařík, W. Pol, Ia. Holovatsky (Padiuka Reference Padiuka2008, 437). Who was Mykhailo Levchenko and could he have any other bearing on Lvovianyn’s text and map?

Unfortunately, not much information is available about Levchenko. Being mostly known for the linguistic articles published in Osnova in the 1860s, his participation in the activity of the South-Western Section of Russian Geographic Society in Kyiv in the mid-1870s, and his 1874 Russian-Ukrainian dictionary, Levchenko remains absent from the conventional narratives of the Ukrainian national movement of the second half of the 19th century. One knows for sure, though, that his literary career started not in Ukrainian nationalist publications, but in Mikhail Pogodin’s conservative “Muscovite” (Moskovityanin). In 1855, it published Levchenko’s vivid memoirs of his participation in the Hungarian campaign of the Russian army in 1849. Being temporarily stationed in northwestern Hungary, Levchenko revealed his interest in the local population of this area. It turned out that, contrary to the data provided by P. J. Šafařík in his 1842 ethnographic map of the Slavs, this area was populated by the “Little Russians” or “Ruthenians”:

During a conversation with this old woman I discovered that all the inhabitants of this and the neighboring villages were Little Russians, or, as they were called here, Ruthenians (Rusnyaki), even though they were so magyarised that only old men remembered their native language […] To find Ruthenians here surprised me a lot and even more so since they were not indicated here by the ethnographic map of the Slavs by Šafařík.

(Luginskiy Reference Luginskiy and Levchenko1855, 71).Levchenko explicitly mentioned his “surprise”: it seems that by the end of the 1840s Šafařík’s map was a normative and respectable source of knowledge about various Slavs for Levchenko and his contemporaries (cf. with Antonovych’s map drawn during his studies of Šafařík).

Six years after his publication in Moskovityanin, in 1861 the newly established Osnova published Levchenko’s text with a detailed description of places of living and the local names of the “Ruthenians.” It was preceded by an epigraph taken from a famous text by the Russian diplomat of the 17th century, Grigoriy Kotoshikhin: “To write without too much sophistication, but about things which I heard from the reliable people and which I saw on my own eyes” (Levchenko Reference Levchenko1861, 263). This sentence was intended to provide credibility to Levchenko’s article, written not by an armchair traveller, but “partially on my own observation” (Levchenko Reference Levchenko1861, 265). It seems that the problem of “Ruthenian” geography had already interested him for a while, but he only found a way to express his ideas publicly in 1861.

What remained previously unknown, though, is that half a year after the publication of his article, in June 1861, Levchenko sent a letter to the editor of Osnova, Vasyl Bilozersky, from his village of Maiorske in the Kherson province. Levchenko informed Bilozersky that he read the May issue of Osnova, but did not find an answer to his question if the editor was going to publish Levchenko’s article “Ruthenian Homeland” (Rusinskaya Rodina):

I was intentionally hurrying to finish it, so that it was in the most possible, so to say, integral condition. I sent it to demonstrate it to you in an unpolished condition […], but there will be time to edit and complement it. […] If this does not bother you, I would like to ask you to return me the manuscript of the “Ruthenian Homeland.”

(OR RNB 1861, 1–2)Footnote 5In July issue of 1861 Bilozersky replied, acknowledging the receipt of Levchenko’s draft of Ukrainian “national geography” (pospyt narodnei zemlepysi), thanking him and promising to publish his “useful work” soon (Osnova Reference Levchenko1861, 34). However, no article with such name or content appeared in Osnova.

Why was this text not published in Osnova? Perhaps it had to do with its editor, Bilozersky, who was notoriously famous for careless, slack, and disorganized performance of his editorial duties (Bernshtein Reference Bernshtein1959, 193–194). At the same time, the reason why the larger geographic description of Ukraine by Levchenko was not published in Osnova could have been related to some complications with the vigilant state officials or censors. Even though the most authoritative contemporary scholar of Osnova, Viktor Dudko, argues that the journal suffered much less from the censorship than was previously contended (Dudko Reference Dudko2013), it was still closely watched by the authorities. The latter were concerned about the potential danger of its national territorial messages. Thus, in February 1861, Sergey Urusov, an assistant to the Synod procurator and a state-secretary of the Emperor, shared the experience of his stay in one of the Ukrainian provinces with his superior, the Synod procurator, Aleksandr Tolstoy:

I spent the long-awaited day of 19 of February in Chernigov. Everything went nicely. The Little Russian spirit, though very cautiously and very cunningly, reveals itself among the people and landlords with some feeling of alienation towards everything Russian. There exists a peculiar journal, it seems that it is published in Petersburg, named Osnova, which is to be followed strictly; I was told that in one of its issues the borders of Little Russia were delineated very broadly

(Romanchenko Reference Romanchenko1939, 26).This reaction of Urusov was caused by the Levchenko’s article from the 1861 issue of Osnova, wherein he described the Ukrainian national territory. Moreover, Urusov did not read the article himself, but “was told” about it: territorial texts published by Osnova seem to have been discussed by the public. Thus, they were noticed by imperial officials.

Conclusion. Zhytomyr, Maiorske, Saint Petersburg, and Lviv—Toward a New Geography of the Ukrainian National Movement

Changing traditional methodology of history of cartography by engaging textual sources from both the Habsburg and Romanov empires allowed us to see the story of the 1862 map published in Lviv in a new light.

First, in the beginning of the 1860s, Russian Ukrainian activists were unquestionably interested in the territorial extent of the Ukrainian nation and even had some handwritten maps of the Ukrainian national territory in their possession. Therefore, the map printed in Lviv at the end of 1861 and published in the local calendar in 1862 should only be considered the first published ethnographic map of Ukrainians.

Second, in 1861, Mykhailo Levchenko, author of the geographic description of Ukrainians in the January issue of Osnova, tried to continue his short article with a larger study titled “Ruthenian homeland.” For some yet unclear reasons, it was not published in Saint Petersburg. One year later, an unsigned article and map were published in Lviv. Curiously, both bear a striking resemblance to Levchenko’s text, enlarging it in those places that could not be understood by the Galician audience. Taking into consideration the name of the article published in Lviv (“Ruthenians. Fragments of a larger historic-ethnographic text, which is currently being prepared for a publication”), we might hypothesize, that Levchenko was not just the main inspiration behind the article and the map from Lvovianyn, but he was, indeed, their previously unknown author. The probable reason to publish both of them in Galicia could somehow be related either to the poor management of the only Ukrainian publication in the Romanov empire at the time—Osnova—or to problems its editor could have had with the imperial authorities, who noticed the potentially subversive nature of its territorial publications.

Third, contrary to previous scholars (Padiuka Reference Padiuka2008, 437; Rovenchak Reference Rovenchak and Vavrychyn2000, 110; Seegel Reference Seegel2012, 195; Sossa Reference Sossa2007, 163; Symutina Reference Symutina1993, 25–26), all of this gives sufficient evidence to insist that the first textual and cartographic descriptions of Ukrainian national territory—which started to appear in the beginning of the 1860s in Saint Petersburg and Lviv—were created not in Habsburg but in Russian Ukraine, which was the center of contemporary Ukrainian national activity. Only later were these descriptions transferred to Galicia.

Fourth, the story of the article and map from Lvovianyn reveals the porous boundaries between the Habsburg and Romanov empires and emphasizes the importance of taking both contexts into account when studying the Ukrainian national movement of the 19th century.

Finally, the case of the first Ukrainian ethnographic map also supports the methodological necessity of examining both maps and texts together while studying national territorialization. The approach one should opt for has to be located at the juncture of history of cartography and intellectual history. Only then will it be possible to get a clear picture of the process of any national territorialization.

Acknowledgments.

This article was written in the framework of the Basic Research Program at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). I thank Darius Staliunas for organizing an ASEEES panel, where this paper was discussed, and Peter Haslinger with other panel participants for their valuable comments and questions. Its text would have been much worse without Nathan Marcus and his careful reading.

Disclosure.

Author has nothing to disclose.