INTRODUCTION

Visitors to Chinese firms often see organization units with a purely social function, which are unrelated to or only loosely coupled with firms’ core business units. These social function units are organizational substructures that offer social services supportive of but distant from firms’ business units and goals, such as kitchens, dining halls, medical clinics, and affiliated schools for the children of employees (Lu, Reference Lu1989; Pfeffer, Reference Pfeffer, Lawler III and O'Toole2006). Rather than outsourcing these services, many firms directly run them. Economists suggest that the creation of these social function units and provision of these social services are leftovers from the planned economy and that spinning off the social function units is essential for restructuring state-owned enterprises (SOEs), as part of building modern enterprises (Lin, Cai, & Li, Reference Lin, Cai and Li1998). Even without mandates and instructions from state and local governments, however, some newly established privately owned firms even now maintain social function units to provide social services internally (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2010).

Why do these firms in China still incorporate social function units and offer community services? Answering this question is practically and theoretically important because it helps us better understand how some contemporary Chinese firms operate and how they perform corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities, thereby advancing extant theories about organization.

This phenomenon found at Chinese firms resembles the idea of organizations as communities proposed by Pfeffer (Reference Pfeffer, Lawler III and O'Toole2006: 4), who suggested that in the past Western firms took care of employees (and their family members) in every aspect of daily activities, and ‘there were deeper connection between companies and their workers and more of a sense of communal responsibility than exists today’. Pfeffer listed the dimensions that characterize the degree to which organizations are communities; for example, helping employees when they are in need – whether financially, in personal relationships, or spiritually – building recreational facilities within firms, and extending concern to the health and well-being of employees’ families. However, at the time he was writing, a ‘trend toward more market-like and distant connections has spread throughout the world’. He claimed that ‘the absence of much sense of community in most organizations is quite real and quite important for understanding the evolution of work in America, the relationship between organizations and their people, and the attitudes and beliefs of the workforce’ (Pfeffer, Reference Pfeffer, Lawler III and O'Toole2006: 4). The diminished sense of community within organizations accounts for the decline in employees’ job satisfaction and commitment and the rise of incivility in the workplace.

The separation of community and business organization dates back to a century ago, when people started to build a modern industrialized society that favored a hierarchical structure of bureaucratic organizations (Janowitz & Abbott, Reference Janowitz and Abbott2010), because people thought ‘localistic sentiments could be barriers to participation in the large metropolis’ (Janowitz, Reference Janowitz1978: 266). Communities differ from organizations in their stability, boundaries, and internal cohesion, and communities mostly retreated to their geographical residence. Community is a method of social organization that involves personal mindsets and physical arrangements, as it is ‘a reflection of series of service and socialization institutions and the symbolic definition imposed on the locality in order to create a social order in which households seek to survive’ (Janowitz, Reference Janowitz1978: 266). As Janowitz states, community has retreated from industrial and work organizations; however, it persists as a way of organizing people and their physical goods at the social level.

More recently, some organization scholars have rediscovered the value of community, finding that communities have an enduring influence on organizational behaviors, such as CSR (Marquis, Glynn, & Davis, Reference Marquis and Battilana2007) and strategy (Lounsbury, Reference Lounsbury2007). Marquis, Lounsbury, and Greenwood (Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011) conceptualize community as an institutional order. Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury (Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012) further develop the concept of community into institutional logics, saying that community provides a unique institutional logic for organizations and individuals, among other institutional logics. Theorizing community from an institutional logics perspective advances our understanding of organizations. However, as Marquis et al. (Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011: xviii) write, ‘while there have been a number of recent advances in understanding how communities form an essential institutional order, in many ways the study of community logics is still in its infancy’. A decade later, this statement still largely holds, in that many fundamental questions remain unanswered – for example, Pfeffer's (Reference Pfeffer, Lawler III and O'Toole2006) question ‘What happened to the idea of organizations as communities'? Theorists taking a community logics perspective still view community and organization as separate entities, and few put the two together to inquire about the meaning for organizations and organizational studies.

In this study, we conduct our research in China to explore the changing and ongoing relationship between communities and organizations so as to understand the community institutional logics at the organizational and individual levels. Our goals are to better explain and explore the salience of community institutional logics and to identify new theoretical models for making sense of this phenomenon. Thus, we conduct a multicase qualitative study, rather than employing other methods (Ragin & Amoroso, Reference Ragin and Amoroso2018). Our data collection and analyses follow the rules of a holistic approach of grounded theory (Gioia, Corley, & Hamilton, Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). We applied inductive logic during our research and iteratively dialogue between extant theories and the evidence collected, in attempting to understand the Chinese organizational phenomenon from new perspectives, to reveal its unique characteristics, and to advance our theoretical understanding.

THE CHANGING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COMMUNITIES AND ORGANIZATIONS

Communities Within Organizations

In most societies, social services and public goods are commonly provided by and distributed within communities, rather than organizations. A community is a social entity that is often seen as a human group larger than an organization but smaller than a society. Tönnies (Reference Tönnies2001) uses the term community to refer to social groups that share the same moral code and have similar values, so community members are generally homogeneous and tied by reciprocal and personal relationships. Hillery (Reference Hillery1955) compares 94 definitions of ‘community’ and finds that the geographic area, interpersonal ties, and social exchanges are some of the universal characteristics of communities. In a community, individuals typically interact within a geographic range, even though the boundaries are not always fixed.

In addition to geographically bounded communities, other types of communities also interest organizational scholars. For example, Djelic and Quack (Reference Djelic and Quack2010) introduce the concepts of a transnational community and a virtual community to describe social groups that emerge from mutual interaction across physical boundaries, such as national boundaries, and social groups that are working on a common project or building a shared identity. These new concepts of community downplay geographic factors and enable expansion in the area of studies: transnational teams, transnational organizations, and even entire countries can thus be viewed as transnational communities.

There are scholars (e.g., Marquis & Battilana, Reference Marquis and Battilana2009) who reaffirmed the importance of geography in studying business organizations. In their view, communities are locationally dependent, which is in contrast to another notion in the institutional analysis of organizations: organizational fields. Distinguishing between communities and organizational fields helps organizational studies scholars recognize that organizations are embedded simultaneously in local and global networks. Marquis and Battilana (Reference Marquis and Battilana2009: 286) regard the community level of analysis in the study of organizations as ‘a local level of analysis corresponding to the populations, organizations, and markets located in a geographic territory and sharing, as a result of their common location, elements of local culture, norms, identity, and laws’.

Organizational scholars have extensively examined the relationship between communities and organizations. In general, formal organizations are viewed as key actors embedded in communities and interaction networks of organizations as helping to build the structure of modern communities (Galaskiewicz & Krohn, Reference Galaskiewicz and Krohn1984). In this sense, community building is in line with organization building. In addition to interorganizational networks, interpersonal networks across organizational boundaries help to build the structure of a community. For example, Galaskiewicz (Reference Galaskiewicz, Powell and DiMaggio1991, Reference Galaskiewicz1997) studies elite networks in an urban community, finding that social networks shape the behaviors of organizational leaders and that those leaders in return help to build the community's structure.

Although organizations and communities are traditionally conceptualized as two different, even opposite mechanisms for social organization (e.g., Janowitz, Reference Janowitz1978), some perspectives challenge this dichotomy. Local residents and permanent workers are likely to see organizations in a community less through the lens of a power structure and more as structures that provide them with social services. According to Perrow (Reference Perrow1991: 726), the rise of large organizations makes them a key phenomenon in that ‘large organizations have absorbed society. They have vacuumed up a good part of what we have always thought of as society and made organizations, once a part of society, into a surrogate of society.’ Large organizations, formerly embedded in communities, are now absorbing community structures, goods, and services. It is possible for a large organization to absorb various groups and small organizations into its management scope and effectively turn them into parts of its superstructure. Thus, rather than having organizations embedded in the community, the community can be embedded in the organization.

On the basis of the foregoing, we see the relationship between communities and organizations as occurring in three ways. First, organizations are embedded in communities. In particular, organizations that were founded earlier are deeply rooted in local communities (Marquis, Reference Marquis2003). These organizations are also associated with one another and developed a strongly networked community (Galaskiewicz & Krohn, Reference Galaskiewicz and Krohn1984). Second, organizations absorb some functions and elements of communities. As Perrow (Reference Perrow1991: 726) observes, ‘Activities that once were performed by relatively autonomous and usually small informal groups (e.g. family, neighborhood) and small autonomous organizations (small businesses, local government, local church) are now performed by large bureaucracies'. Third, organizations are transformed into forms of community. According to Perrow (Reference Perrow1991), large organizations absorb elements of communities and operate in accordance with bureaucratic logic; it is also possible for some organizations to incorporate many elements of communities and operate in accordance with community logic. Both logics can be understood from the institutional logics perspective, which is a recent development in new institutionalism (Almandoz, Marquis, & Cheely, Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2017; Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991; Marquis et al., Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012).

Community Institutional Logic Within Organizations

Friedland and Alford (Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991) laid a foundation for theorizing institutional logics. They proposed that each of the central institutions in the contemporary capitalist West (capitalist market, bureaucratic state, democracy, nuclear family, and Christianity) ‘has a central logic–a set of material practices and symbolic constructions–which constitutes its organizing principles and which is available to organizations and individuals to elaborate’ (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991: 248). These institutional logics are potentially contradictory, and individuals and organizations can make decisions by ‘exploiting these contradictions’ (Friedland & Alford, Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991: 232).

Thornton et al. (Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012) developed Friedland and Alford's (Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell and DiMaggio1991) initial theoretical framework: because the set of material practices and symbolic constructions (i.e., culture at the institutional level) varies across institutions, they categorized order within institutions into ‘the root metaphors, sources of legitimacy, identity, norm, authority, and the basis of attention’ (55). They also included the ‘basis of strategy, informal control mechanism, economic system’ in the category. Thus, they urge us to look at institutional logics as in a coordinate, with different institutions as the x-axis and the elements of institutional order as the y-axis (56). They further developed Marquis et al.'s (Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011) initial thoughts and included community as an institutional order. The community logic differs from other institutional logics in terms of the content of its y-axis categorical elements – for example, its norm is based on group membership: in contrast to employment in corporate institutional logic, its basis for authority is the emotional connection of members, not their bureaucratic roles in firms. Although these categories and elements marking the axes may be seen differently by various researchers, Thornton et al.'s framework provides a more complete picture of institutional logics in many societies.

Thornton et al. (Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012) further suggest that it is vital to include community in institutional logic because its absence makes it impossible to know how the set of norms and practices started and spread. Applying the institutional logics perspective generated some insightful empirical studies, leading some scholars to discover how community and its institutional logic shape organizational behaviors and strategies (Lee & Lounsbury, Reference Lee and Lounsbury2015; Marquis & Tilcsik, Reference Marquis and Tilcsik2016).

Almandoz et al. (Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2017) worked on theorizing community institutional logic by including geographic and affiliation-based communities, the latter of which is enabled by information technology and transcends the need for physical proximity (O'Mahony & Ferraro, Reference O'Mahony and Ferraro2007). Extending the community institutional logic to virtual communities is important for understanding how people collaborate online and produce public goods, and it creates great potential for the application of community institutional logic. Thus, in the contemporary world, organizations grow not only by absorbing a large part of the society but also by encompassing virtual communities where community institutional logic dominates.

The community institutional logic perspective can enhance our understanding of the dynamic relationship between communities and organizations, as discussed earlier: (1) organizations embedded in communities; (2) organizations and communities jointly forming networks; and (3) communities embedded in organizations. It is obvious that organization scholars have studied the first two relationships, but the third is largely overlooked in organizational studies, our hunch is that this is where community institutional logic is more salient and can be easily observed and studied.

The institutional logic analysis of communities embedded in organizations helps to answer some questions left by the organization scholars mentioned above. For example, Almandoz et al. (Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2017) introduced the idea of degrees of community, but to what extent can we call a social entity a community? They viewed a small rural village as a community because of its loyalty, common values, and emotional attachment. However, based on Perrow (Reference Perrow1991), large industrial organizations involve a large portion of society and might tend to be more like communities than smaller groups. Older organizations might be more like communities simply as a legacy of the past. However, how do some newly founded firms operate using the community logic?

Neither Clans Nor Fiefs: Chinese Firms as Communities

China has a history of running socialist SOEs, and these organizations differ in many ways from those in the West. A Chinese SOE can be simultaneously an organization and a community, with elements of a factory bureaucracy and of a community. The smallest organizational element is called a ‘work unit’ (danwei; Frazier, Reference Frazier2002; Steinfeld, Reference Steinfeld1998). This model has also been employed by private firms, which for a time had no other organizational models to emulate (Han & Zheng, Reference Han and Zheng2016); for example, when it was founded, the computer manufacturer Lenovo mimicked the structure and positions of SOEs (Ling, Reference Ling2005).

Although work units can be traced back to a time before the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) took power in 1949 (Bray, Reference Bray2005), the socialist state dissolved other forms of firm ownership but legitimatized and popularized the danwei system (Lu, Reference Lu1989). Work units can be further divided into enterprise work units and institutional work units. The former includes businesses, factories, and other production, service, and distribution organizations; the latter include governments, educational institutions, and other state-supervised organizations. Both types of work units incorporate social services and employee welfare into their organization. Thus, in addition to their business goals, enterprise work units promote the goals of social stability and community betterment.

The Chinese state carried out a series of reforms designed to build an industrial system that would achieve socialist goals. For example, firms established before 1949 were all reorganized and restructured by 1955. The socialist reform in the manufacturing and service sectors during the early 1950s was an effort to convert all firms to state or collective ownership. During this process, firms undergoing reformation were labeled work units and charged with performing social welfare functions in addition to meeting production and service goals (Walder, Reference Walder1986). Consequently, workers received a wide variety of welfare benefits from their employers. For example, after being hired, workers understood that they had an implicit contract with their firm (i.e., the state) that virtually guaranteed them lifetime employment. In addition, workers received subsidized housing, free child care and education for their children, free medical care for their families, and a guaranteed pension, to name a few. SOEs thus incorporated a majority of these social functions into their management practices and built social function units along with their business units: ‘Through building into organizations service units (dining halls, public bathrooms, barber shops, schools, hospitals, cinemas, etc.) and making them not for profit, work units are actually providing social welfare services to their members’ (Lu, Reference Lu1989: 72).

Today, China's SOEs still perform many functions for which other types of firms might not take responsibility, including systematic labor protection and social welfare. Compared to other organizational forms, work units have a division of labor and efficiency goals that are more likely to be influenced by the scientific management goals of the erstwhile Soviet Union. They might also perform some social functions that, while not defined by the state, are typical in communities in a modern society.

Privately owned enterprises (POEs) and joint ventures became increasingly important in the Chinese economy; however, SOEs still play a crucial role. Many SOEs were marketized and even privatized during the mass restructuring that took place in the late 1990s. After 1994, when the Chinese government enacted the Company Law, Chinese firms could choose to become either limited-liability corporations or limited-share companies, thereby gaining legal status as independent entities. The Company Law defined a separation of ownership and operations, and it affirmed the importance of corporate managers. It also helped create an official organizational model for firms: the ‘modern enterprise system’. The lengthy text of the Company Law laid out goals and specified means of building this new organizational model, which emphasized an autonomous market orientation. It also laid a foundation for the restructuring and privatizing of SOEs. Since the enactment of the Company Law, many policy makers and economists have encouraged Chinese firms to abandon the work-unit system and to follow the modern enterprise system, which is a model that imitates the efficient bureaucracy of Western firms. So, what is the organizational form used by Chinese firms? Have they completed the transition from work units to a modern enterprise system?

Boisot and Child (Reference Boisot and Child1988, Reference Boisot and Child1996) proposed that, because of China's distinctive political, institutional, and cultural characteristics, a new form of corporate governance had prevailed in China. They used a framework that views economic transaction-related information as the codification and diffusion of information. Consequently, economic organizations come in various forms: in addition to markets and hierarchies, there are fief- and clan-like organizations. When transaction-related information is uncodified and undiffused, societies tend to develop fief-like organizations, such as in China, as analyzed by Boisot and Child; when the information is uncodified but diffused, clan-like organizations tend to form (Boisot & Child, Reference Boisot and Child1988).

Since the start of China's economic reform in the late 1970s, many SOEs have become marketized, and many POEs have been established; hence, there has been a steady trend toward diffusing transactions and transaction-related information. Thus, many of those fief-like business organizations have developed into clans. Central control by the state has been devolved to local levels. The Chinese cultural value placed on face-to-face interpersonal communication persists, so there have been fewer efforts at the codification of transaction information. Boisot and Child (Reference Boisot and Child1996) argued that, because of the growth of marketized state-owned and collectively owned enterprises and the proliferation of POEs, Chinese businesses that once suffered the ‘iron law of fiefs’ were eventually transformed into clan-like organizations. Those new organizational forms serve as the basis of ‘network capitalism’, in which transaction information has been diffused yet is still not quite codified, unlike in market and bureaucratic organizations. China's economic scale significantly changed over the past three decades, but Boisot and Child (Reference Boisot, Child, Brown and Porter2018) retained their analytical initial framework and arguments unchanged.

The periods of stability and change experienced by Chinese organizations over the past three decades have to some extent challenged Boisot and Child's (Reference Boisot and Child1996) arguments. First, they stated that both fiefs and clans can handle only a small or moderate number of transactions and that the resulting transaction information is highly uncodified. The mass adoption of information technology and growth of large enterprises, however, enable Chinese firms to use codified information in addition to personal relationships in transactions. Second, they built their arguments on analyses of Chinese POEs, collectively owned firms, and marketized SOEs, with the implicit assumption that nonmarketized SOEs were no longer important. However, SOEs persist, making that assumption inaccurate. Third, they built their analysis of Chinese organizational forms on Ouchi's (Reference Ouchi1980) conception of clans.

Ouchi (Reference Ouchi1980) used the word ‘clan’ to refer to a type of organization that resembles a kinship network but that may or may not include blood relations. Specifically, he used Japanese firms as examples of clans: such firms hire inexperienced workers, socialize them into their corporate culture, and pay them according to a scale that depends on nonperformance criteria, such as years of service and number of dependents. Thus, socializing and learning are important ways of maintaining control in clans. However, Chinese firms and Japanese organizations fundamentally differ in some ways. For example, Chinese firms put less emphasis on training and learning as a means of socializing employees (Yu & Egri, Reference Yu and Egri2005). Also, whereas Japanese firms are still under the historical influence of the long-term or permanent employment, Chinese firms now rely heavily on contract labor. These workers typically have low levels of education and high levels of mobility across firms – although it is worth noting that better-educated employees have also begun to have higher levels of turnover in recent years. These facts clearly violate Ouchi's (Reference Ouchi1980) definition of a clan. If a Chinese firm is conceptualized as neither a clan nor a fief, it is necessary to develop a theoretical framework to identify its unique type and the extent to which this type fits well with the general economy and the social environment.

These contemporary Chinese organizational phenomena – the persistence of social function units, the digitization of transaction information, and the continuing importance of the work-unit system in the Chinese economy – challenge the validity of organizational theories about Chinese firms. The community institutional logic perspectives, as developed in recent years by Marquis, Thornton, and their colleagues, may be helpful in studying Chinese firms because they function like both organizations and communities. The study of Chinese firms with community institutional logic, in turn, can help to develop the theoretical perspective.

In studying Chinese organizations, some insightful studies apply institutional logics in general and community institutional logics in particular. However, they still view communities and organizations separately (Raynard, Lounsbury, & Greenwood, Reference Raynard, Lounsbury and Greenwood2012; Zhang & Luo, Reference Zhang and Luo2013), and they tend to use deductive logic to test existing theories, rather than ‘addressing grand challenges’ (Eisenhardt, Graebner, & Sonenshein, Reference Eisenhardt, Graebner and Sonenshein2016: 1119) posed by emerging markets. In the past three decades, academic attention has drawn on either micro issues of organizational behavior or macro issues of external control of Chinese organizations without taking into account the local geographical factors. As a result, community-level organizational analyses were largely overlooked. The Chinese organizational phenomenon mentioned at the beginning of this article inspired us to explore more on internal factors at Chinese firms to better understand the underlying mechanisms in firms’ community-like structures and social activities.

METHODS

Research Design

Our primary goals are to interpret the significance of the phenomenon of communities within organizations and to advance our scholarly understanding of it. Qualitative methods are more suitable for attaining our research goals (Eisenhardt et al., Reference Eisenhardt, Graebner and Sonenshein2016; Ragin & Amoroso, Reference Ragin and Amoroso2018). We conduct a multicase study with a grounded theory approach for the following reasons (Bansal, Smith, & Vaara, Reference Bansal, Smith and Vaara2018). Central to theoretical building from case studies is replication logic, so multiple cases allow us to replicate the theoretical logic or contrast it to others (Yin, Reference Yin2018). However, qualitative research suffers from disadvantages, such as the difficulty in balancing contextualization and generalization (Plakoyiannaki, Wei, & Prashantham, Reference Plakoyiannaki, Wei and Prashantham2019). Fortunately, for years, grounded theory method (GTM) scholars developed formal procedures for conducting qualitative research, balancing between clarity and flexibility in analyzing and presenting data. After careful considerations, we decided to follow a constructive version of GTM (Charmaz, Reference Charmaz2006, Reference Charmaz, Hesse-Biber and Leavy2008) and the Gioia methodology (Gioia et al., Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013) in conducting our research.

Sample

We combined the typical case sampling and heterogeneous sampling methods in three steps (Saunders & Townsend, Reference Saunders, Townsend, Cassell, Cunliffe and Grandy2018). First, we applied the typical case sampling method to identify the target firms. Popular though it may be in an emerging country, functioning as a community is not prevalent at all companies, and our research goal was to demonstrate and understand the forms of and reasons for this practice, so we initially selected typical firms that demonstrated at least some evidence of encompassing social services. Thus, we selected firms that had internally built social facilities such as cafeterias, which can be viewed as minimal and fundamental evidence of social function units. Second, we applied the heterogeneous sampling method and selected firms that varied across cities in various regions, industries, types of ownership, and sizes in order to achieve the maximum variation in our cases. Third, we contacted the target firms and requested permission for interviews and in situ observation, and we finalized the sampling list of firms that granted us permission. Applying these criteria and identifying a variety of cases allow us to compile detailed empirical descriptions of this particular phenomenon (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Reference Eisenhardt and Graebner2007).

Our final sample was based on two data sources. The first source was job advertisements in brochures that some companies sent to a key Chinese university in 2008 and 2009. The ads were publicly available to students at the university in an exhibition hall during the academic term. We paid special attention to ads that emphasized employee benefits rather than salaries. We selected eight firms and contacted them, explaining our research purpose and requesting permission for on-site visits. The second source consisted of personal connections of the first author. By evaluating the level of social services embedded in the company, the first author identified three large SOEs in the city of Lanzhou and contacted them. Accordingly, we received approval from six firms – three from each source. We dropped one firm from the second source because that firm was identical to another one in providing services to employees. The five focal firms are dispersed in three geographical divisions of mainland China; they can be understood as a nationwide sample. The dates on which the case studies were conducted were mutually decided on by the researcher(s) and interviewees. Table 1 provides a description of the five firms.

Table 1. Data sources

Notes: Revenue amounts and numbers of employees were obtained on the most recent interview dates, and the exchange rate as of the end of April 2012 was RMB 6.3: USD 1.

Each firm was given a code name in Table 1. Information on firms’ founding year, industry, revenue, number of employees, and statement of employee benefits was obtained from multiple sources: web pages, handbooks printed by the firms, and the city statistical yearbook at libraries. Information on the firms’ location came from in situ observations and online maps. We collected firm ownership information from their web pages or from direct phone calls to them.

Data Collection

We conducted 16 semistructured interviews; they ranged in length from 0.5 to 3 hours (1.5 hours on average) and included both open- and close-ended questions. The interviews were conducted in Chinese. Among the 16 interviews, 14 were with individuals and two were with groups. We aimed to have interviewees at different levels in the organization. For example, at each of the five firms, we interviewed lower-level employees; at three firms (CF, LS, and HT), we interviewed middle managers in different departments; and at two firms, we interviewed the top leadership, a vice president (and COO) of SD and the founder (and CEO) of JY.

Our data comes mainly from semistructured interviews and in situ observations (Alvesson, Reference Alvesson2003; Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015). In organizing the interview questions, the primary principle for researchers was to understand what, how, and why social function units actually operate at each of the firms. As such, we asked mainly formulated open-ended questions, such as what social function units the firm has, who can use them, when people can use them, and why the firm offers them. In addition to the interviews, the first author of the article and the assistants were allowed to visit either all or some of the firms’ units at least once. The researcher had the opportunity to visit three of the five firms more than once to cross-validate the observations. In all, the researcher spent many hours (excluding traveling and in situ observations) not only watching and observing the units in operation but also having informal conversations with different stakeholders at the company sites, such as workers, line managers, and middle managers.

We made two audio recordings of the interviews after receiving approval and took handwritten notes and wrote memos on all the interviews and observations. To ensure the quality of our data collected, we took several steps to achieve methodological triangulation (Flick, Reference Flick, Bryant and Charmaz2019) in our research: (1) in order to balance observer insights with interview reflections, not every author of the article performed in situ observations; (2) interview questions posed to employees and employers were essentially similar, enabling us to triangulate our information collected from different respondents; and (3) we distributed our tentative findings to interviewees to avoid individual biases. We deposited the collected and computerized data on the Open Science Framework for multiple robustness checks. The internet link toward datasets is provided at the end of this article. Thus, this was an evolving process – as we collected more data, read about more theories and methods, and consulted more experts, we obtained more detailed information and gained more insights into this organizational phenomenon.

Data Analyses

After we had the audio recordings transcribed and compiled the notes and memos, we followed the conventional data analysis procedures using an inductive approach by iterating between our interview and observational data, the existing literature, and our own emerging theory (Corbin & Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015). In particular, we adopted the two-stage coding method proposed by Van Maanen (Reference Van Maanen1979) and formalized by Gioia, Corly, and Hamilton (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013). In the first stage, we used open coding to help identify emerging themes. As we read the raw materials collected line by line, we paid particular attention to the themes related to community characteristics, such as what, how, and why firms adopted social function units. We continually triangulated interview data with in situ observations in order to achieve valid information. In the second stage, we used axial coding, which helped us identify similarities and relationships among empirical themes both within and among cases. In this stage, we aimed to identify conceptual categories that were well grounded in our data but also echoed relevant studies on organization as a community (e.g., Pfeffer, Reference Pfeffer, Lawler III and O'Toole2006). We then summarized the themes and categories as three theoretical dimensions.

After the coding process, we were able to draw a structured figure on moving from raw materials, concepts, and themes to the theoretical dimension in a process that Durkheim (Reference Durkheim2013) described as finding social facts from facts. We did not stop with the data structure that we found, as it provides only a static picture of the information. To reveal the underlying mechanism, we developed a theoretical model of building organizations as communities. In this stage, we followed Gioia et al. (Reference Gioia, Corley and Hamilton2013) and focused on identifying the dynamic relationships among the emergent concepts, themes, and dimensions that describe or explain the phenomenon of organization as a community as well as clarifying all the relevant connections between data and theory.

RESULTS

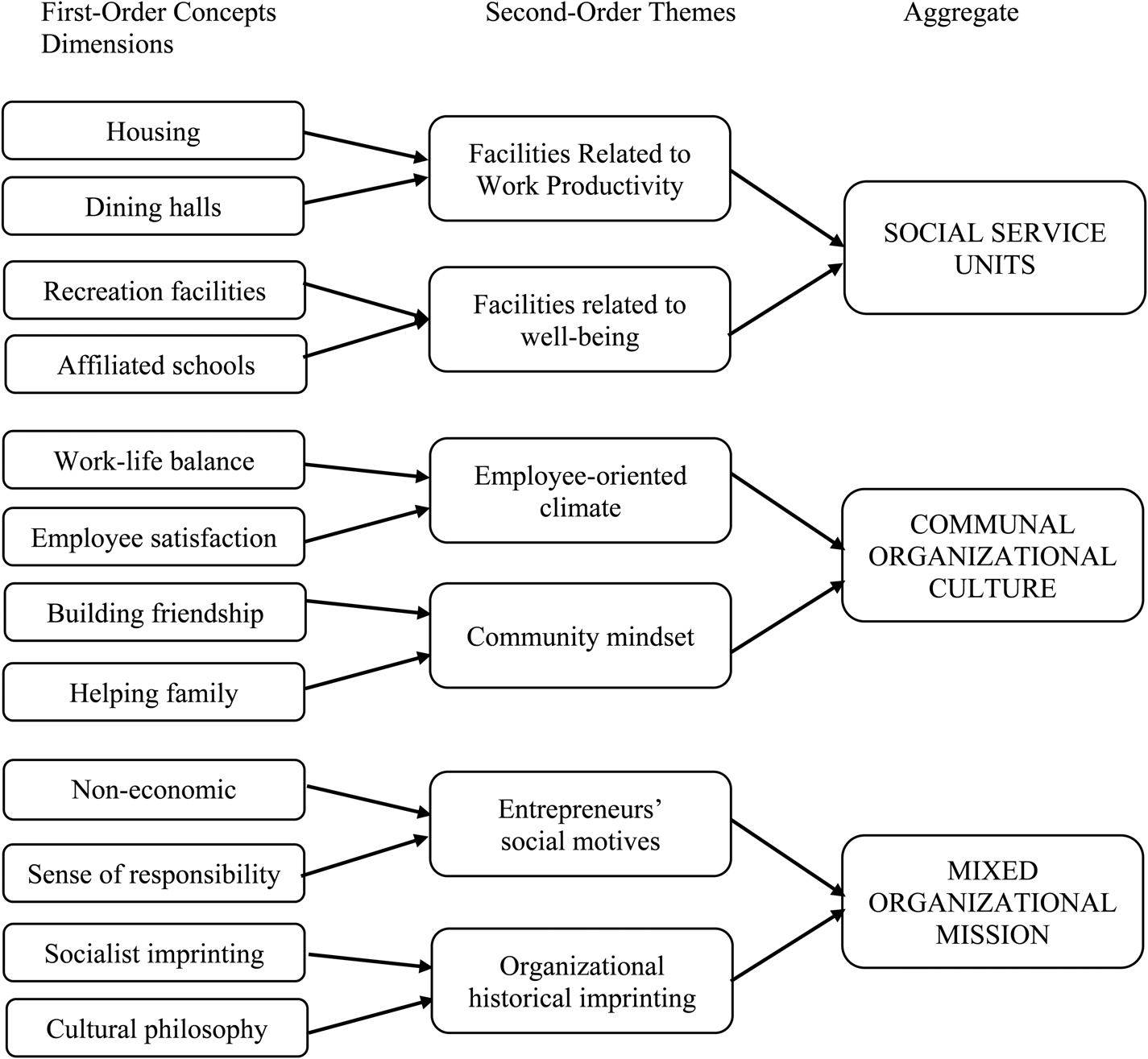

The data structure obtained from our two-stage coding is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Data structure

Social Service Units

All the firms incorporated some types of social service units in addition to housing and dining facilities, even at the privatized SOE (SD) and the POEs (HT and JY). Housing and dining facilities are indispensable in indirectly enhancing employees’ work productivity and efficiency. CF was a typical example showing how a firm incorporates various social function units. Essentially, the firm's facilities were divided between business units (changqu) and social function units (shenghuoqu), the latter of which consist of living quarters for most employees, with the two groups of buildings separated by a narrow street. With the exception of the administration building and a residential apartment building, buildings were mostly built in the 1950s. According to a human resources (HR) manager (CF 2), before 2001, CF provided free apartments for all married employees and free group dormitories for single employees. At the time of our interview, CF no longer provided free housing for married couples. All employees had access to a large dining hall that served meals at below-market prices. According to a worker in her fifties: ‘One does not have to go outside the factory [firm] to get stuff for everyday life’ (CF1).

We directly observed that the layout at LS was more dispersed, but it had similar social function units. CF and LS were both located within surrounding communities that also provide ample goods and services, so their employees could satisfy their everyday needs at their social function units or on the market. In contrast, SD was located somewhere that social services cannot easily be accessed. Through our direct observations and a group interview with SD's managers (including a vice president and the heads of HR, sales, and production), we learned that SD had provided dining halls, medical clinics, and dormitories for its employees since it was founded in the 1940s as a military factory. One manager was proud that SD is ‘good at providing food and residence services’ (SD 1). We also visited JY, a privately owned firm with only 200 employees, 150 of whom came from farming backgrounds. We interviewed JY's founder and CEO and seven randomly selected employees from the company's roster. We were given access to all areas of the company. In addition to its main business units (e.g., HR, research and development, production), JY has several social function units: a well-decorated dining hall that resembles a family kitchen, a small gym, a TV room, and a library with technical documents as well as materials for leisure reading.

In addition, we found that all the firms also offered more extensive services and facilities to support employee well-being. LS had a recreation center, a soccer field, and a library, all of them free for employees and their family members to use. LS also built an affiliated elementary school and an affiliated middle school for children of employees. A worker at LS confirmed the relative stability of the internal management structure, adding to the discussion of the social function units as well as the business units: ‘Although the affiliated middle school now claims to be independent, 80%-90% of its students still come from LS employees’ families’ (LS 3). Overall, we found two different types of social function units. The first type concerned employees’ everyday lives, such as food and housing, and the second type concerned employees’ families and offered extended services for them. Table 2 displays interview data and our observations on social service units at these firms.

Table 2. Data display illustrating building social function units within firms

Notes: Each interview was recorded as the initials of the company and a number, for example, JY 1; each in situ observation was recorded as Dir and a number, for example, Dir 2.

Communal Organizational Culture

We learned from our data that the five firms have common characteristics regarding their emphasis on work–family balance and employee satisfaction, based on our interviews with the employers and the employees. For example, the owner of SD mentioned that ‘we care more about the satisfaction of our customers and our employees [than short-term productivity]. We provided places and rooms for them to rest and to have cups of tea during their work breaks. We did not overwork them; rather, we let them achieve a balance between work and their lives’ (SD 2). The employees’ statements show that they were satisfied with their work–life balance. One employee even said: ‘If the company only paid me money, I would not have a sense of belonging’ (HT 3). This implied that the employees viewed their relationship with the firm as more than just an economic exchange.

During our several visits to the headquarters of HT, a large POE, we saw that its employees also enjoyed many conveniences, thanks to the company's numerous social function units. Along with its main business units (e.g., HR, research and development, production, sales, and customer service), HT had built social function units, such as state-of-the-art cafeterias, dining rooms, medical clinics, and residential apartment complexes. As the manager of the Supply Department said: ‘HT employees spend most of their time at the company. We want them to feel as if they live in a friendly community. The company pays employees’ salaries, and employees use their salaries to support their families. Why not support our employees’ families directly? Some families of employees receive money directly from the company if their spouse works abroad for a long time, and if their elders are ill and have additional expenses. There are no written rules for these kinds of firm activities; we perform them at our own discretion’ (HT 1).

Because HT has built a ‘community-like’ culture, it manages employees according to ‘community rules’, not ‘organizational rules’. An engineer who worked at HT for over ten years regarded building a community within the company as ‘natural’: ‘People say “business is business,” but it is hardly true in China. We are here not just to make money. We have goals for our lives. Families and friends are important. If you work long hours at the company, your colleagues are your friends, and they can help you take care of your family when you need it’ (HT 2).

Table 3 displays interview data and our observations on organizational culture favoring community.

Mixed Organizational Missions

Some firm owners whom we interviewed expressed some non-economic motivations regarding the operation of social function units. The owner of SD said: ‘We don't always maximize profits’ (SD 2). The owner of JY stated: ‘I was born to think this way: the problems of the world are my problems, and the problems of human beings are my problems, so I have a duty and responsibility to solve these problems and to work for the betterment of society’ (JY 2). When asked about his motivation for founding the firm, he responded: ‘My goal in setting up this company is fairly clear: happiness, for me and for everyone who works here–not to keep growing and making a large sum of money’ (JY 2). We inferred from these statements that the entrepreneurs’ motivations shape the organizations’ missions, which influences the adoption and operation of those social function units.

In addition to the reasons articulated by the firm owners, we also found that socialist imprinting and cultural philosophy played an important role. According to an HR manager (LS 1), the company underwent a years-long restructuring after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001. Like many other SOEs, LS is subject to the 1994 Company Law regulations requiring it to set up a modern enterprise system. However, LS has also maintained some stability. LS retained the affiliated schools and hospitals, and the only difference was that the social function units started to operate independently of the firm's administration; at the time of the interviews, they also admitted students and patients from outside the company.

Likewise, the managers at SD were worried that they would have to change their organizational structure and culture to adapt to the parent firm that had acquired it. They were also worried about changes to their organizational identity and leadership style: ‘We were an SOE, and we are influenced by military discipline and Confucianism. … Our management team did not look for one leader to solve problems; we relied on collective wisdom’ (SD 3). But the managers agreed that they ‘would not destroy good things that have already been established’. When asked what the ‘good things’ were, they referred to the social services and social function units that SD continued to offer its employees. The managers even wanted the parent firm to adapt its structure and culture somewhat more toward theirs: ‘We can change more, and [the parent firm] changes less. But it is good for them to change a little bit, too’ (SD 3).

Ten years earlier, JY's CEO was a sole owner who wanted to partner with an SOE in Shanghai. He knew a lot about the pros and cons of SOEs at that time, but he told us that he ‘always looked at the positive sides of SOEs and of governments’ because they, too, wanted to do things better – although they were constrained by time and a lack of opportunity (JY 2). He told us, ‘I knew ten years ago what kind of organization I would like to build. Modern management does not treat people as humans, and it's a terrible mistake. We give priority to [job] applicants with whom we are familiar. There are over twenty couples in our company, including parents and children. I personally like such configurations’ (JY 2). According to one JY employee, the CEO is a patient teacher who cares about everyone: ‘He told us, when we have difficulties in life, come to the company first for help. For example, we can borrow money from the company at no interest. It is faster and better than the social insurance [we are all provided]. I heard that someone's mother-in-law was ill and needed money, and the CEO got money from our company [for that employee]’ (JY 1).

In sum, all five firms in our case studies incorporated some social function units into their organizations. None of them are required by laws or regulations to do so. For the SOEs, however, doing so was part of their tradition and their historical imprint; when we asked the managers and employees at LS about the history of their current employee welfare practices, they referred to the founding years in the 1950s. As one HR manager at LS said, ‘Ever since this firm was established in the 1950s, we have given lots of benefits and welfare to the workers. This is our tradition’ (LS 1). Both CF and LS face problems in providing enough welfare benefits for their employees because of a lack of resources in today's market economy. According to one worker at CF, a decade earlier, her family could live on the welfare benefits from the factory without spending much of her salary, but this is no longer the case (CF 1). Nevertheless, thanks to social function units and the sense of community that they instill, the turnover rates of experienced workers at these companies remain relatively low.

The private firms in our case studies had purposefully built social function units at their establishments, but they did not adopt a universal organizational welfare system on the basis of equality; rather, they devised bonus systems through which they rewarded employees on the basis of performance. Although their first organizational model was the structure of the SOE, not that of Western firms, they tended to apply new management skills in making their social function units more efficient. Even though they later learned new organizational models and management practices from the West, such as the matrix structure and the Key Performance Index (KPI), they were more likely to modify their business units than their social function units. As a senior engineer at HT told us, ‘People think that we obtained our first successful model from IBM. Actually, when we started from nothing, we had nothing but policies [for starting new enterprises in special economic zones]. We had no model to follow but SOEs–our initial organizational structure was the same as that of an SOE. We set up positions according to that structure. And we used advanced management skills for managing factories to manage these functional units’ (HT 2). Table 4 displays interview data and our observations from visits about firms’ mixed goals and missions.

The majority of Chinese SOEs were established in the 1950s under the state's first economic five-year plan. During this period, the market form of organizations was abandoned. Employee performance was judged according to several criteria, such as tenure, political status, and efficiency. At their founding, SOEs were imbued with multiple goals, including production and social functions, for example, maximizing the rate of employment in society. Employees received low wages from work units but received generous welfare and additional compensation from social support within the organization, such as at CF.

After 1994, when the Company Law was first enacted, SOEs such as LS and SD were reformed to adapt to the new market economy, both nationally and internationally. Based on our case studies, although their business units were restructured according to the model defined by the modern enterprise system in the Company Law, their social function units were largely unchanged. HT and JY were established as private firms, so we expected them to follow the Company Law and build an organizational form that is isomorphic to firms in affluent Western countries. However, they still built organizational forms that included social functions and social services.

A Model of Building Organizations as Communities

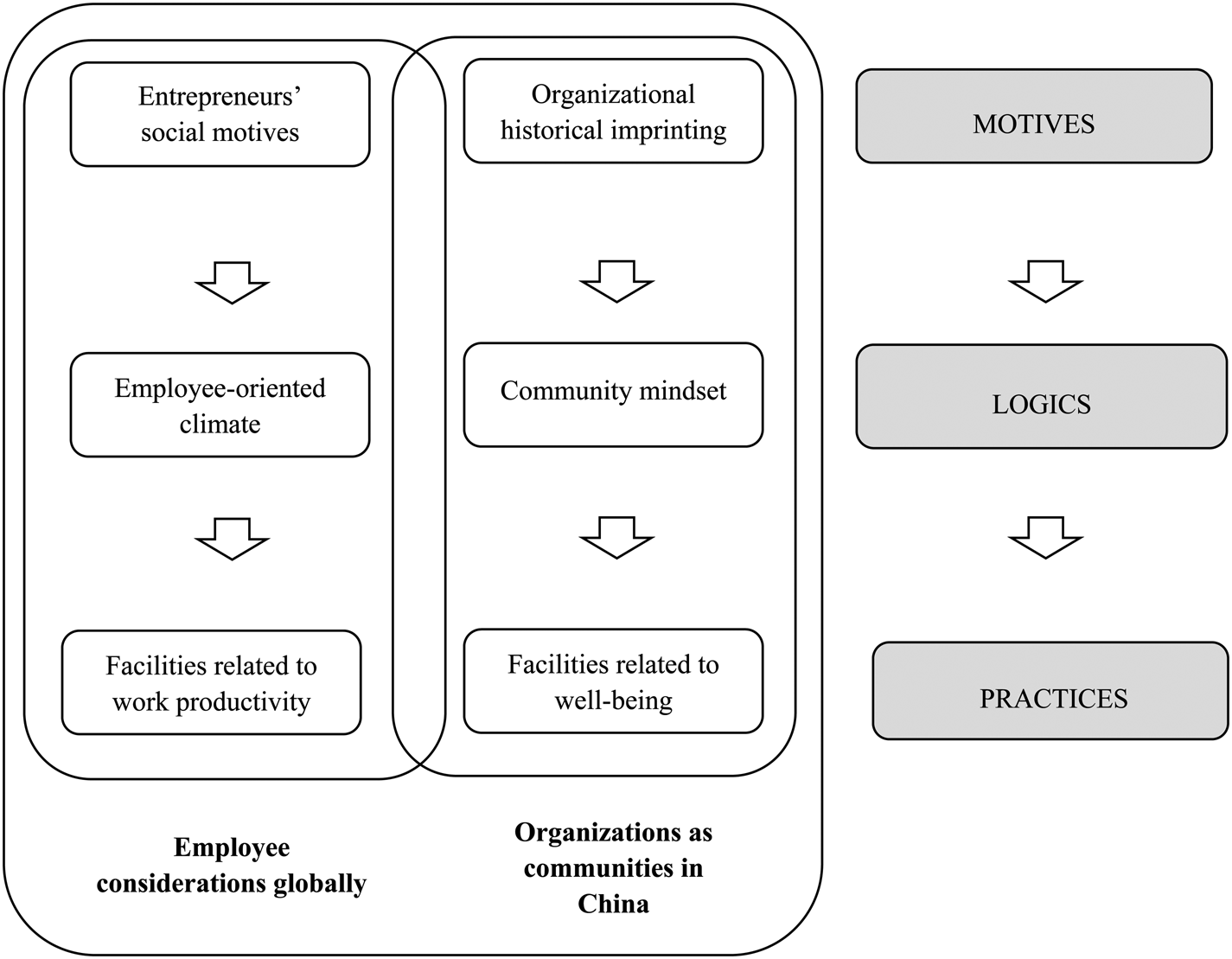

Based on the foregoing analyses, we found that all five firms tend to view social function units at firms as necessary conditions. Some of the firms (CF, LS, and SD) tend to view setting up these units and providing services for their employees as traditions that employees take for granted, whereas other firms (HT and JY) tend to view these units as way to increase employee productivity and the efficiency of the company in the long run, especially units such as health care, dining rooms, and housing near the production facilities, because they reduce employees’ commuting time. Social function units such as schools, cinemas, and libraries, however, fall into a less efficiency-oriented category. Our findings enabled us to identify two mechanisms that link the themes and dimensions in our empirical studies, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. A model of building firms as communities to illustrate how community institutional logic works

In Figure 2, the left-hand axis measures employee considerations globally, because we can identify similar practices, logics, and motives across countries when the company takes care of its employees (Heckscher & Adler, Reference Heckscher and Adler2006; Janowitz, Reference Janowitz1978; Marquis et al., Reference Marquis, Lounsbury, Greenwood, Marquis, Lounsbury and Greenwood2011; Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Ocasio and Lounsbury2012). Some firms in China also try to find a rationale along these lines to legitimatize their community-building activities. Among our cases, HT and JY, for example, which are both privately owned and have good financial performance (see Table 1), seem to fit on this axis.

The right-hand axis in Figure 2 measures China's socialist imprinting at enterprises (Han & Zheng, Reference Han and Zheng2016; Marquis & Qiao, Reference Marquis and Qiao2018), and we label it ‘organizations as communities’ in China. Their practices, logics, and motives are unique. Many scholars have believed that this mechanism originated in socialist state-building (Walder, Reference Walder1986), from a combination of Chinese rural culture and military bases (Lu, Reference Lu1989). However, others have found that the blueprint for work units has deeper roots that trace back to before 1949, when firms in big cities such as Shanghai and Chongqing hired peasant workers (Bray, Reference Bray2005). Our study does not involve a historical analysis, but we find that the mechanism shown on the right-hand axis captures some unique characteristics of organizations and startups in China. We are aware that the imprinting effects of a community logic might exist elsewhere in the world (Gupta, Briscoe, & Hambrick, Reference Gupta, Briscoe and Hambrick2017; Simsek, Fox, & Heavey, Reference Simsek, Fox and Heavey2015); however, those imprints might differ from those that we found.

The two mechanisms, employee-centered management and community building within organizations, are two different main lines of practices, logics, and motives, but they are not mutually exclusive (Kish-Gephart & Campbell, Reference Kish-Gephart and Campbell2015). For example, units related to work productivity (e.g., cafeteria) might also function to make life more convenient and respect employee health, whereas units related to well-being (e.g., affiliated schools) might serve as a motivation for employees’ organizational commitment and job loyalty. Therefore, the overlap between the two mechanisms in Figure 2 suggests that understanding them might require an integrated perspective, as many practices, logics, and motives apply to both of them.

DISCUSSION

We began our qualitative research with inductive logic in mind, trying to introduce insights from Chinese firms and the community institutional logic perspective. Taking a new perspective on organizations, we developed a process model from data (Figure 2) to understand communities embedded within organizations such that organizations can resemble communities, regardless of their size and age. We also implied that the community institutional logic varies across countries, with some global elements in the logic and some local elements in the logic. Based on the new understanding of organizations as communities in China, an emerging market, our research offers some implications that may be helpful for organizational researchers and practitioners.

Theoretical Contributions

Our research makes a number of contributions to the literature on organizational studies, three of which emerge from the research findings. First, after reexamining the relationship between communities and organizations, we found that, in addition to the fact that firms are physically embedded in communities (e.g., implied by Granovetter, Reference Granovetter1985), it is possible that communities are essentially embedded in firms. Our research captures the unique characteristics of some Chinese firms and conceptualizes them as an ideal type: the community model of organizations. If an organization incorporates many social function units into its structure, that organization can be viewed as a community; thus, studies of communities also be included in organizational studies. To be sure, some management scholars have long recognized that offering employees nonmonetary rewards could be a factor in motivating them (Herzberg, Mausner, & Snyderman, Reference Herzberg, Mausner and Snyderman1959). However, we introduce a new theoretical perspective to conceptualize organizations as communities, allowing us to revisit the relationship between communities and organizations.

Second, the process model we built intends to reveal two mechanisms: the first type of community-like organization is found globally, and the second type has some unique characteristics based on Chinese social–historical culture. Matten and Moon (Reference Matten and Moon2008) proposed that, unlike the US which values explicit CSR, such as philanthropy, European countries tend to focus more on implicit CSR, such as protecting employee welfare. They recently called for future research because ‘there are particularly rich opportunities for exploring the processes of explicitization and implicitization in developing or emerging business systems’ (Matten & Moon, Reference Matten and Moon2020: 20). Thus, our empirical study responds to the call and supports the notion that many community-like Chinese firms follow the implicit CSR logic proposed by Matten and Moon (Reference Matten and Moon2008, Reference Matten and Moon2020). We show that some employee-oriented practices at Chinese firms are more than a unique practice of CSR; rather, they are part of an integrated organizational structure that follows a community format.

These two mechanisms interact in our research context – for example, historical imprinting and entrepreneurs’ social motives might be closely related in a national context, and so are a community mindset and employee-oriented environment. Some firms (e.g., LS, an SOE) maintained social function units because it is part of their tradition, whereas others (e.g., HT, a POE) built social function units for efficiency purposes. However, they are not mutually exclusive, because employee well-being within organizations benefits the efficiency goal of firms, and vice versa. This model of dual mechanisms has some advantages in terms of transferability to other cultures and societies. For example, Figure 2 demonstrates elements of both global and local community logics; in countries without such organizational imprints, entrepreneurs’ ‘enlightened self-interest’ (Galaskiewicz, Reference Galaskiewicz1997) is important in building communities within firms.

Lastly, because of this new dual mechanism model that we discovered from studying Chinese firms, our research also enables a better understanding of the community institutional logic introduced by a number of organization scholars in recent years. As mentioned earlier, the conventional perspective of a community institutional logic still views a community and an organization as separate social entities, implying that community has enduring influence on organizational behaviors and strategies. Our research indicates the emergence of a form of relationship in which organizations not only influence their local community but incorporate communities as inseparable components. The communities within organizations might work differently from outside organizations. HT, for example, extends its management to its internal communities, and its kitchens, dormitories, and other social function units are closely controlled by the management to ensure the quality of services. Our multiple cases also reveal that a community institutional logic can work at organizations of various sizes, ages, and development levels, which is in contrast to the view of some scholars that a community works better at small, old organizations in less industrialized areas (e.g., Almandoz et al., Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2017).

In addition to the community institutional logic perspective in this article, other theories address community-like organizations. For example, taking the loose-coupling perspective, Weick (Reference Weick1976) uses a university as an example and argues that in multiple-unit organizations, all the units pertain to the main goal of the organization but function in irrelevant ways. A community form of an organization, however, can comprise business units and social function units; whereas business units stick to the main goal of the firm, social function units might or might not align their activities directly with the main goals of the firm. In addition, recognizing influences from communities seemed to position our theory in the thread concerning the external control of organizations (Pfeffer & Salancik, Reference Pfeffer and Salancik1978). However, our research shows that community influence can come from within firms, other than influences from external environments.

Practical Implications

Understanding this organizational model, employed by Chinese firms for decades, provides practitioners with insights into how to build their business relationships with Chinese firms as well as how to run businesses in China. First, there are important implications for firms that have already embedded some kind of community features, especially those in emerging markets, in facing a new business agenda, such as CSR. Restructuring firms to adapt to the world economy has been a main theme in Chinese economic reforms. In the 1990s, when a rational discourse of management dominated, an ideal type of the modern enterprise system that emphasized efficiency in management, production, and transactions was seen as a remedy for the problems experienced by SOEs, such as overinvestment in political capital and underinvestment in productivity and innovation. In the 21st century, however, firms have set new agendas, among them engagement in CSR, which includes employee well-being, benefits, and labor protection. Some Chinese firms now face a dilemma about whether to build a rational modern enterprise and incorporate CSR programs later on or to retain at least some of the social units that they have built over the years and let them serve CSR goals. Our suggestion favors the latter – social function units can simply undergo a goal-replacement process, from an emphasis on political goals to an emphasis on CSR goals.

Second, there are implications for firms that have not engaged in community building: doing so internally could help them do business better, especially in emerging markets and places where social services are absent or barely sufficient for the needs of organizational members. For example, in response to its Chinese employees’ concerns, Motorola built a community in which subsidized childcare facilities, family service centers, and shopping malls were made available to employees (Zhang & Zhang, Reference Zhang and Zhang2010: 203). This Motorola community resembles the typical surroundings and services enjoyed by Chinese workers in socialist China. Whereas Chinese firms adopt managerial ideologies and practices that they learned from Western societies, some foreign firms in China have started to incorporate ‘Chinese characteristics’ into their day-to-day management. Previous scholars have studied the role of transnational certifications and transnational firms (Bartley, Reference Bartley2007; Locke et al., Reference Locke, Qin and Brause2007) and the role of global private firms in promoting efficiency and advocating CSR practices in developing countries (Guthrie, Reference Guthrie1999). Some also find that local practices matter (Devinney, Reference Devinney2011), but few have theorized the phenomenon in which good practices might spread from less developed countries to the developed countries. Our research indicates that emerging markets can offer insights into the management of organizations as well.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our study has several limitations. First, we did not discuss the negative aspects of the community model for current and former firm employees, which have been studied by several sociologists who analyze labor relations (e.g., Lee, Reference Lee2000, Reference Lee2007). Our investigation took the perspective of firm managers and employees, many of whom spoke positively about the social services that their firms provided. We did not interview those who lost jobs in the organizational transition, which is a flaw due to our exclusive focus on successes in the Chinese economy in this research. So, what are the negative aspects of the community model? What motivates some firms not to adopt this community model? Research focused on these questions is critical for understanding the capabilities and limits of the community model of organizations.

Second, our research focus was the discovery and description of organizations as communities, and we introduced some perspectives from community studies. But what are the negative impacts of community-like organizations on local communities? Do they increase inequality in local communities? Worse still, do they absorb local communities and eventually make them vanish? Is there a crowding-out effect between the social functions offered by the firms and the local communities? We studied five firms but had limited only observations of their local communities. Future research should expand the research scope to include the perspectives of local communities as well.

Third, we focused our research on geographically bounded communities and did not look into other types of communities, for example, virtual communities that do not involve organizations (O'Mahony & Ferraro, Reference O'Mahony and Ferraro2007). The rapid development of information and communication technology made it much easier for individuals to collaborate across boundaries of organizations, communities, and countries. Teams of online communities may be more efficient than those in organizations. The development of new technology also made it possible to have task-oriented communities even without organizations. How does the community institutional logic work in this new kind of community? Almandoz et al. (Reference Almandoz, Marquis, Cheely, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby2017) conducted some initial theorizing analyses on the institutional logic of affiliation-based communities, in addition to geographically based communities. The empirical research on communities without organizations (or limited organizing) is promising.

CONCLUSION

Our study reveals some unique characteristics of Chinese firms, but it also reveals some general characteristics of doing business outside China as well. In the US, for example, firms with a community model were easily found in the past, but they gave way to ‘rational’ CEOs and management models (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg2009; Samuelson, Reference Samuelson1993). They existed, then vanished, and now have been rebuilt in places such as Silicon Valley. These firms, which offer social function units, albeit under a different name, might have different origins and founding blueprints from those in China. How does their operation differ from that of similar units at Chinese firms? Comparative studies across national boundaries are promising to learn how communities are built within various types of organizations.

Management scholars, especially scholars of new institutionalism, implicitly assume that the best practices are diffused from developed countries to developing countries. We suggest that developing countries can also generate sources of best practices, and these practices might be transferrable to business firms elsewhere. We hope that the community model of organizations proposed here will inspire more in-depth studies and that they in turn will help to improve the quality of work life at more firms.

NOTES

We thank three anonymous reviewers and the MOR editors for providing helpful comments and suggestions. Special thanks to Professor Joe Galaskiewicz at the University of Arizona and Professor Anne Tsui at Arizona State University for their supportive comments on an early draft of this paper. This research is partially supported by China Social Science Foundation (No. 20BSH147).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The main datasets that support the findings of this study are available in a database of the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/wr9vh/. Additional information can be requested from the corresponding author. All data users must abide by the ethics of doing research as well as ethics of doing businesses.