1. Introduction

A broad view of the morphosyntax of Iranian languages (in the Old, Middle, and Modern era) reveals that those Iranian languages which have grammaticalized a split alignment system constitute the three types summarized below:

(i) A type whose splitness is sensitive to aspect (perfect versus imperfect/non-perfect) and transitivity.

(ii) A type whose splitness is sensitive to tense (past versus non-past) and transitivity.

(iii) A type whose splitness is sensitive to just tense (past versus non-past).

Representative examples of type (i) are the East Modern Iranian language Yaghnobi [yæqnobi], a descendent of a variety of Sogdian, spoken in TajikistanFootnote 1 and the South-Western Iranian language Old Persian.Footnote 2 Examples (1) and (2) are from Yaghnobi and examples (3) and (4) are from Old Persian. Examples (1) and (3) contain simple past tense imperfect predicates whereas examples (2) and (4) exhibit perfect aspect (with current relevance at the time of speaking).

With respect to example (1), Payne says “[it] illustrate[s] the nominative-accusative system with definite direct objects in the simple past.”Footnote 7 In his characterization of examples like (2), Payne writes:Footnote 8

“By contrast, the case-marking system in the perfect and plu-perfect is ergative, with transitive subjects in the oblique case, intransitive subjects in the absolute [namely direct] case, and all direct objects in the absolute [namely direct] case.”

Payne describes the function of -ḫ as: “[it] marks agreement in person and number with intransitive subjects and transitive object.”Footnote 9

To type (ii) belongs a large number of Iranian languages, e.g., Middle Persian and a long list of Modern Iranian languages and dialects such as Northern Kurdish, Central Kurdish, all varieties of Baluchi except for Baluchi of Zabol/Sistani Baluchi, Laki, Talyshi, Tati, Davani, Larestani, Delvari, Naini, Vafsi, Raji, Behbahani, Hawrami, Gazi, Abuzeidabadi, Pashto, and many others. In my corpus of the Iranian languages of Iran, I have been able to locate varieties belonging to the third type only in Khorasan area more specifically in Razavi Khorasan and mostly in Southern Khorasan.

The former dialect of Birjand (presently the center of Southern Khorasan province) in the late 19th and early 20th century, the present-day dialects of the city of Ferdows in Southern Khorasan, the village Khanik, in Kakhk of Gonabad in Razavi Khorasan province, and the dialect of the district Se-Ghal’e [se-qæl’e] in Southern Khorasan province are the dialects in this eastern part of Iran which have grammaticalized type (iii). However, the dialect of Birjand has completely lost its splitness and it is now several decades since it is restructured as uniformly Nominative-Accusative.

The very existence of these language and dialect islands in Khorasan, the reasons for the rapid change and drift in the former dialect of Birjand, and a linguistic description of the state-of-the-art in the dialects of Ferdows (which I have recently directly observed in my visit), Khanik, and Se-Ghal’e will be the main focus and concerns of the present paper.

This paper consists of three other sections. In Section 2, entitled “The Survey”, a linguistic analysis of the above-mentioned dialects will be presented. In Section 3, the findings will be evaluated in a historical context. In Section 4, I will present my explanation for why the split alignment in the former dialect of Birjand changed so rapidly. In Section 5, the findings will be summarized.

2. The Survey

In this section, a linguistic description and analysis of the alignment peculiarities of four Iranian dialects which geographically belong to Khorasan area in the east of Iran will be presented in separate subsections.

2.1 The former dialect of Birjand

Birjand is the center of Southern Khorasan province with a population of about 178020 residents according to the official statistics of 2011. This province is bounded on the east to Afghanistan, from south to Kerman and Sistan and Baluchestan provinces, on the west to Yazd province, on the north-west to Semnan province, and on the north in Razavi Khorasan province.

In the former dialect of Birjand, as it was spoken in late 19th and early 20th century, there are examples which reveal a uniformly Nominative-Accusative system in terms of indexation. In that dialect S (namely the subject of an intransitive verb) and A (that is the subject/agent of a transitive verb) could be indexed in the verb in the form of a verbal agreement suffix. The O/P (namely the object/patient) of a transitive verb is not indexed in the verb. Examples (5) – (9) substantiate these observations.Footnote 10

The examples in (5) – (9) which are perfectly grammatical in today’s dialect of Birjand were collected by Jamal Rezaee (1926-2001), a former professor of Ancient Iranian languages and cultures at Tehran University and a native speaker of that dialect. As a young researcher, Rezaee collected data which show that, there were two other patterns to encode the S and A of the verbs formed with past stems. One of those patterns was the indexation of S and A of past tense verbs by pronominal proclitics. A very interesting example of this pattern is found in item (10) which contains three verbs. The first verb in this example is an intransitive verb formed with the past stem. The S of this verb is indexed by a pronominal proclitic whose host is the verb itself. The two other verbs in example (10) are transitive verbs formed with present stems. The A of these verbs are indexed as verbal agreement suffixes. What makes this example more interesting is that it is a variant of example (7) above to which the intransitive verb indexes its S by an agreement suffix.

Examples (11) – (13) contain intransitive verbs formed with past stems. In all of these examples, S is indexed by pronominal proclitic and the verb is its host.

Examples (14) and (15) are complex clauses whose embedded and matrix clauses contain past tense intransitive verbs. Interestingly the embedded adjunct clause in both examples uses the verbal agreement suffix strategy to index S whereas the matrix clause verbs host the pronominal proclitic to index the S.

I tend to call examples (14) and (15) mixed in terms of the indexation of S.

Example (16) contains a complex clause whose verbs are transitive verbs which are formed with past tense stems. Both verbs are compound verbs and the light verb hosts the pronominal proclitic which indexes the A.

Rezaee explicitly calls the pronominal proclitics which index S or A (without using our typological terminology today) as “verbal agreement markers and have no independent use and always accompany the verb.”Footnote 23

In sum, I have introduced two patterns which were grammaticalized to index S and A of verbs formed with past tense stems in the former dialect of Birjand: (a) Indexation by verbal agreement suffixes and (b) Indexation by proclitics. Now, I introduce the third pattern. In this pattern, S and A of the verbs formed with the past tense stems are realized as independent pronouns and the verb is used in its bare past form for all persons. Paradigms (17) and (18) exemplify this pattern. These paradigms are quoted from Rezaee.Footnote 24 The first paradigm contains an intransitive verb and the second paradigm has a transitive verb.

In order to have a complete picture of the indexation system in the former dialect of Birjand, I quote paradigms (19) and (20) from Rezaee which illustrate the second pattern counterparts of paradigms (17) and (18) respectively.Footnote 25

The first pattern of indexation corresponding to paradigms (17) and (19) on the one hand and paradigms (18) and (20) on the other hand are cited from Rezaee in (21) and (22) respectively.Footnote 26 In (21) and (22) the verb indexes S and A by verbal agreement suffixes (see examples (5) – (9)). In paradigm (21), -e in the 3SG could also be glossed as 3SG perfect.

Rezaee points out that “occasionally like Persian both personal pronouns appear before the stem and agreement markers after the verb.”Footnote 27 Paradigm (23) contains his examples.Footnote 28 This paradigm, in fact, is not different from the very first pattern in which S is indexed by a verbal agreement suffix.

In my consultation with every native speaker of the present-day dialect of Birjand irrespective of their age, sex, and education, I received only one pattern which is grammaticalized for all verbs irrespective of tense and transitivity. They only allow a uniformly Nominative-Accusative system whether or not S or A are present in the clause. More specifically, they only allow the verbal agreement suffixes as used in paradigms (21) – (23) in all tenses in order to index S and A.

To summarize, the dialect of Birjand in late 19th and early 20th century had grammaticalized four patterns to index S and A as follows:

(24)

a. With present tense stem verbs, S and A were indexed by verbal agreement suffixes (e.g., examples (5) and (8) and embedded verbs in (7), (14) and (15)).

b. With past tense stem verbs, S and A were indexed by pronominal proclitics on the heavy/ light verb (e.g., examples (11) – (13), (16), (19) and (20) as well as matrix verbs in examples (10), (14) and (15).

c. With past tense stem verbs, S and A could appear as independent pronouns and verbs would remain unchanged for all persons (e.g., paradigms (17) and (18)).

d. A uniformly Nominative-Accusative system for all past tense verbs irrespective of transitivity (e.g., examples (6), (9), (21) – (23) and the matrix clause in (7)).

The sets of examples in (25) and (26), which show the conjugation of an intransitive and a transitive verb in the present perfect forms, are very illuminating examples of the productivity of the three patterns (20)b – (20)d in the former dialect of Birjand. These examples are cited from Rezaee.Footnote 29 It may be noted that each set conveys the same proposition.

The evidence which were presented in this subsection suggest that the former dialect of Birjand was split along the parameter of tense. However, the existence of mixed alignment systems in the former dialect of Birjand can be taken as an indication of a drift towards a uniform Nominative-Accusative alignment which is now grammaticalized.Footnote 30 In Section 4 of the paper, I will describe the factors which pushed the Nominative-Accusative alignment to be fixed.

2.2 The present-day dialect of Ferdows

Ferdows is an ancient city in Southern Khorasan with a population of about 24,703 residents. I visited Ferdows in 14th and 15th of March 2018. The data which I will present here, unless otherwise specified, were collected during that memorable visit. I also visited the nearby village Gastaj [gæstæǰ] with a resident population of around three hundred. My grammatical analysis of Ferdows is valid for the dialect of Gastaj as well. I was told that the teenagers in the village tend to speak in Persian, the dialect of Tehran, because they think that having a local accent is unpleasant.

My main informant of the dialect of Ferdows is Mohammad-Jafar Yahaghi, seventy years old, who was born, lived, and educated up to the university level in Ferdows. Dr. Yahaghi is professor of Persian language and literature at Ferdowsi University of Mashhad. Dr. Yahaghi notified me that he did not know Persian before starting his primary school education.

The dialect of Ferdows is split in terms of subject marking which is merely sensitive to tense. In verbs formed with the present stem, S and A are indexed in the verb by verbal agreement suffixes. Examples (27) – (32) illustrate this observation.

In constructions containing past tense verbs, S and A are realized in two pronominal forms: As independent pronouns and as pronominal enclitics. When S and A appear as independent pronouns, the bare past tense stem of the verb remains unchanged for all persons. Paradigms (33) and (34) exemplify clauses with S and A respectively. The first paradigm was elicited from Yahaghi in my consultation session with him and the second one is cited from his paper.Footnote 31 Glosses are added by me.

Additional examples which substantiate the same conclusion are provided in sentences (35) – (38) below. In (35) and (36), S is a noun whereas in (37) A is a pronoun and in (38) S is a pronoun. These examples are also taken from Yahaghi.

It is noteworthy that in example (37) the object is marked as such, therefore in terms of case marking the examples in (35) – (38) show the Nominative-Accusative alignment. On the other hand, in clauses formed with past stem verbs, S and A may be realized as pronominal enclitics. Paradigms (39) and (40) correspond to paradigms (33) and (34), respectively. Paradigm (39) is elicited from Yahaghi and paradigm (40) is cited from Yahaghi.Footnote 32

Now, I present paradigm (40) in which a transitive verb is used.

The pronominal enclitics which index S and A in the dialect of Ferdows are mobile. Examples (41) – (44) provide very informative information about the possible hosts of a pronominal enclitic which indexes S. In example (41), the S is overtly present, thus no corresponding pronominal enclitic to index it is needed. Example (42) is ungrammatical. In example (43), the adverb is the host for the pronominal enclitic. In example (44), the negative morpheme is the pronominal enclitic host.

In example (45), which is the past tense counterpart of example (29), the adverb hosts the pronominal enclitic which indexes the S.

Examples (46) – (50) contain a transitive verb formed with the past stem. In example (30), I presented the present tense counterpart of (46) and in (37), its past tense counterpart with an independent pronoun functioning as A was mentioned. In examples (46) – (50) below possible and impossible hosts for the pronominal enclitic which indexes the A are illustrated.

In the above set of examples prepositional phrase, direct object, and the non-verbal constituent of the compound verb are the possible hosts for the pronominal enclitic which indexes the A. By looking at examples (39)-(50), the following rule can be proposed for the placement of the clitic which indexes S and A in the dialect of Ferdows: Any constituent except the subject and the light verb (in a compound verb) is the potential host for the clitic which indexes S and A.

In my trip to Ferdows, I heard example (51) in the conversation between two men on the street. Example (52) was uttered by a primary school girl to her teacher apologizing for her inaccurate reading of a verse. In both examples the non-verbal constituent of the compound verb hosts the pronominal enclitic which indexes the subject of the clause.

In example (53) which I cite from YahaghiFootnote 34 the direct object is the host for the pronominal enclitic which indexes the A. The verb in this example is a simple verb.

Examples (54) – (58), which are cited from YahaghiFootnote 35 add another interesting dimension to the peculiarities of the dialect of Ferdows. In these examples, both A and O are indexed as pronominal enclitics. In examples (54) – (56), the pronominal enclitic which indexes O appears on the adverb, whereas the host of the pronominal enclitic which indexes the A is the verbal constituent.

It is worth noting that example (56) is a counterpart of example (53). In (53), the direct object is an independent pronoun whereas in (56) it is a pronominal enclitic. In the former example, the direct object hosts the pronominal enclitic which indexes the A, but in the latter example the verb is its host. In example (57), both A and O pronominal enclitics appear on the verb, and in example (58) they are realized on the verbal constituents.

In my consultation session with Yahaghi I noticed that example (55) has a counterpart in which the pronominal enclitics which index A and O appear on the adverb. This alternant is mentioned in example (59).Footnote 36

Examples (60) and (61), which I elicited in the same consultation session are like examples (55) and (59). The only difference is that the A is now a first person plural enclitic.

The description and analysis of the indexation of A and O as pronominal enclitics require one further clarification. In the dialect of Ferdows, when the direct object is inanimate it is encoded as =e. Yahaghi has described =e as “inanimate … objective pronoun.”Footnote 37 This form is ambiguous between a singular or a plural interpretation. The paradigm in (62) shows the conjugation of a past tense verb. Interestingly, as the pronominal enclitic for O is a vowel, the plural forms preserve the final nasal (i.e. =man ‘1PL’, =tan ‘2PL’, and =šan ‘3PL’).

The pronominal enclitic =e encodes inanimate singular or plural direct object of verbs which are formed with present tense stems as well. Examples (63) and (64) are cited from Yahaghi.Footnote 38 As expected, in these examples A is encoded as a verbal agreement suffix.

Finally, in examples (65) – (67) which also contain a present tense transitive verb, A is indexed by a verbal agreement suffix and O which is animate is indexed by a pronominal enclitic. These examples are cited from Yahaghi.Footnote 39

To conclude this subsection, I claim that the generalizations listed in (68) below capture the typological peculiarities of the dialect of Ferdows in terms of S, A, and O indexation.

(68)

a. With present tense stem verbs, S and A are indexed by verbal agreement suffixes (e.g., examples (27) – (32) and examples (63) – (67)). The O (whether animate or inanimate) if indexed, it is indexed by a pronominal enclitic (e.g., examples (63) – (67)).

b. With past tense stem verbs, S and A are indexed by pronominal enclitics (e.g., paradigms (39) and (40), examples (43) – (48) and (51) – (62)). The O if indexed, it is indexed by a pronominal enclitic (e.g., examples (54) – (61) and paradigm (62)). However, it should be mentioned that when O is inanimate and indexed by pronominal enclitic and the A is also indexed by pronominal enclitic, and the verb is the host for both of them, then the A enclitic precedes the O enclitic (e.g. paradigm (62)), whereas under the same circumstances but O being animate the order is reversed (e.g., example (57)). Examples (59) and (61) also support this last observation though here the host of the enclitics is an adverb.

c. With past tense stem verbs, S and A may appear as independent pronouns and the verb stem remains unchanged for all persons (e.g., paradigms (33) and (34), examples (35) – (38), and example (41)).

Therefore, I claim that the dialect of Ferdows is split in terms of the category tense. That system belongs to type (iii) in the introduction section (namely Section 1). More specifically, with present tense verbs, the dialect of Ferdows is Nominative-Accusative. With past tense verbs, when S, A, and O are indexed, they are indexed by pronominal enclitics. This pattern, I call a tri-oblique system. The tri-oblique system is a special instance of the type which Comrie has labeled as the neutral type.Footnote 40

2.3 The present-day dialect of Khanik

The village Khanik whose dialect will be described in this subsection is located in the district of Kakhk in the city of Gonabad in Razavi Khorasan. The distance between this village and the city Gonabad is 32 km. Khanik is located between Gonabad and the city Ferdows. According to the official statistics in 2006 its population was 350 persons. Mr. Rajabali Labbaf-Khaniki 71 years old (born in 1948 in Khanik) is a researcher in archeology. He knows the area very well. He served as the director of the Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organization in Razavi Khorasan and is now retired. He kindly served as one of my informants. Mr. Rajabali Labbaf-Khaniki notified me in my visit to Ferdows that currently there are about 100 residents living in Khanik, most of them old, but many former inhabitants of Khanik have a house there and visit the village during Now-Ruz ‘Iranian New Year’ and other holidays and for special ceremonies. According to Mr. Labbaf-Khaniki, the residents of Khanik speak Persian as well; and the young residents do not show much tendency to speak and use the dialect of Khanik. Thus, I intend to claim that this dialect is an endangered one.

Khanik, which is locally pronounced Khunek [xunek], is situated in a valley on the Siyah-Kuh ‘black mountain’ heights surrounded by the mountains of the south of Gonabad. This geographical location has led to the isolation of this village.Footnote 41 Ekhtiyari quotes Farahvashi’s Pahlavi dictionary Footnote 42 who has glossed xānīk as “spring [of water]; well of water; main; related to spring.”Footnote 43 Ekhtiyari mentions that “in this village, there are many springs and subterranean canals. It has thirty subterranean canals and about ten permanent springs and it is known as the most beautiful countryside village of Gonabad.”Footnote 44

Typologically, the dialect of Khanik behaves like the dialect of Ferdows in terms of the indexation of S, A, and O (see the three generalizations listed in (68)). Examples (69) – (79) show the first generalization (i.e. (68)a) which says that with present tense verbs S and A are indexed by verbal agreement suffixes.Footnote 45 Examples (69) – (75) contain intransitive verbs and examples (76) – (79) have transitive verbs.

In examples (80) – (83), sentences (80) and (81) as well as the pairs (82) and (83) convey the same propositional meaning. The difference is that in the first member of each pair the O is an independent pronoun but in the second member the O is an enclitic. In both examples with an enclitic O, the A is the host for the O-enclitic.

In examples (84) – (87), A and O are indexed in the verb. A is indexed by a verbal agreement suffix and O is indexed by a pronominal enclitic. It is noteworthy that when O is inanimate, it is indexed by =e. This enclitic may refer to a singular or to a plural inanimate object. The function of =e is identical with that of the Ferdows dialect (see examples in (62)-(64)).

The examples in (81), (83), and (87) in which A is indexed by a verbal suffix and O is indexed by a pronominal enclitic clearly indicate a Nominative-Accusative system in terms of indexation. It may be noted that in (86) and (87) the negative and the complete aspect markers are the host for the pronominal enclitics which index the O.

The dialect of Khanik, like the dialect of Ferdows as summarized in (68)b, indexes S and A of verbs formed with past stems by pronominal enclitics. In examples (88) – (93), the intransitive verb serves as the enclitic host.

In examples (94) and (95), the negative morpheme in the intransitive verb hosts the pronominal enclitic which indexes the S.

Examples (96) – (98) contain the compound verb meaning ‘to work’. This intransitive compound verb formed with past stem is used in several clauses which convey the same propositional meaning. In these clauses, we observe that different constituents may host the pronominal enclitic which indexes the S. The constituent which hosts the pronominal entclitic is under focus. Variant (99) is ungrammatical because the S is not indexed in it.

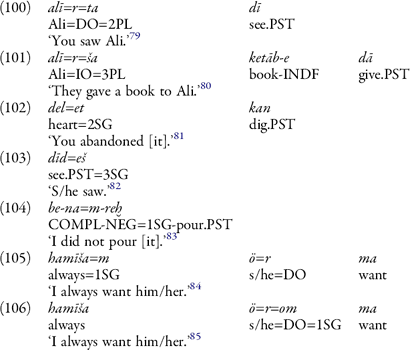

Also in the past tense domain, A is indexed by a pronominal enclitic. In this domain, direct objects, indirect objects, non-verbal part of compound verbs, the heavy verb, negative particle, and adverbs may serve as the host for the enclitic which indexes the A. Examples (100) – (106) support this generalization.

About examples (100) – (106), three additional points deserve mentioning. First, a comparison of examples (100) and (101) shows that the postposition enclitic =r marks both a direct object and an indirect object in the dialect of Khanik. Second, examples (105) and (106) show that the pronominal enclitic may attach to an adverb or ignore it and attach to the O. This variation seems to be motivated by putting focus on the constituent which hosts the pronominal entclitic. Third, in examples (105) and (106), the verb which means ‘want’ behaves like a transitive verb formed with past stem. Further data with the verb which means ‘want’ reveal that sentences containing this verb have grammaticalized both the system of agreement suffixes to index A and the system of pronominal enclitics to index A. In examples (107) – (109) the first system is realized and in examples (110) – (112) the second system is manifested. I cite these examples from Labbaf-Khaniki.Footnote 86

The dual behavior of the verb meaning ‘want’ with respect to the indexation of A is pertinent in the debates on the genesis of ergativity in the Iranian languages.Footnote 88 In example (107)-(109) the verb behaves like a transitive verb whose A is indexed by verbal agreement suffixes. In example (105), (106) and (110)-(112) the verb behaves like a modal verb whose subject is indexed by pronominal enclitics.Footnote 89

In verbs formed with past stem, O may be realized as a pronominal enclitic. In examples (113) – (115), A, which is an independent pronoun, hosts the pronominal enclitic which indexes the O.

In examples (116) – (118), both A and O are indexed by pronominal enclitics in the verb.

Thus, on the basis of examples in (88) – (106) and examples (110) – (118) I conclude that when S, A, and O are indexed by pronominal enclitics we are dealing with a tri-oblique system.

The dialect of Khanik has also grammaticalized the pattern in which S and A are realized as independent pronouns and the verb stem which is in the past tense form remains unchanged for all persons. This is the pattern which was also found in the dialect of Ferdows as summarized in (68)c. Examples (119) – (124) indicate that pattern in the dialect of Khanik.

Example (125) shows the same pattern which we observed in examples (119) – (124). The difference is that the verb form is not past but it behaves like a past tense transitive verb. Example (125) expresses the same propositional meaning which is expressed by examples (105) and (106).

Before I terminate this subsection, I present the short dialogue cited in (126) below from Ekhtiyari in which three occurrences of the pronominal enclitic, one on an adverb, one on the past participle of an intransitive verb, and one whose host is the negative particle, are used.Footnote 103 Ekhtiyari has described the context for this dialogue as follows: A driver takes passengers from the village (namely Khanik) to Gonabad everyday. Somebody was supposed to send a parcel to Gonabad by the driver, when s/he reaches there s/he notices that the driver had already gone.Footnote 104

To conclude this subsection, I propose that the dialect of Khanik has grammaticalized a split indexation system which is sensitive to tense: In the present tense domain, S and A are indexed by verbal agreement suffixes whereas in the past tense domain S and A can be indexed by pronominal enclitics. We also noticed that with the modal verb ‘want’ used in its present stem form the subject is indexed by a pronominal enclitic (example (105), (106) and (110)-(112)). Taking into consideration the fact that in the present tense domain if O is indexed, it is indexed by a pronominal enclitic, we can call this system a Nominative-Accusative system. In the past tense domain, when O is indexed it is indexed by a pronominal enclitic. Therefore, this system may be called a tri-oblique system.

2.4 The present-day dialect of Se-Ghal’e

The town Se-Ghal’e is officially a district which belongs to the city Sarayan [særayan] in Southern Khorasan. Sarayan geographically stands between Ferdows and Birjand. According to the statistical survey of the country in 2016, the population of Se-Ghal’e is 4436 persons. Abbas Riyahi writes that the name Se-Ghal’e is given to this town because there existed three main Ghal’e ‘castle’ in the past there.Footnote 105

Now, I turn to the indexation system of the dialect of Se-Ghal’e. In the sentences in the present tense domain, S and A are indexed by agreement suffixes which appear in the predicate. Paradigms (127) – (129) exemplify this pattern. These paradigms are elicited from Riyahi.Footnote 106

This pattern of indexation is the one we observed in the present tense domain in the dialects of Birjand, Ferdows, and Khanik (see generalization (68)a).

In the past tense domain, one option is that S and A are indexed mainly as pronominal proclitics. Examples (130) – (135) substantiate this observation with an intransitive verb formed with a past tense stem. These examples are cited from Riyahi.Footnote 107

Examples (136) and (137) are the past equivalents of the present tense examples in (128). These examples are quoted from Riyahi.Footnote 108

Example (138) is the negative counterpart of (133).

In example (139), the habitual event of going to school in the past is negated.

Examples (140) and (141) show the present perfect conjugation of the verb ‘to go’ and sentence (142) exemplifies the past perfect conjugation of this verb.

In example (143), which I quote from Riyahi, the paradigm for the conjugation of a past tense transitive verb is presented.Footnote 114

In paradigm (144), the conjugation of the passive form of the verb meaning ‘to see’ is presented.Footnote 115

In paradigm (145), the conjugation of the present perfect of the verb meaning ‘to eat food’ in its negative form is cited from Riyahi.Footnote 116

A negative progressive (namely incomplete aspect) form of the verb meaning ‘to eat food’ and an instance of the negative form of the past perfect conjugation of the same verb are quoted in examples (146) and (147) below.

A new dimension is added to our discussion of the pronominal clitics indexing the A in the dialect of Se-Ghal’e when variations of the kind we observe in paradigms (148) and (149) are compared. These two paradigms are mentioned in Riyahi.Footnote 119 Riyahi describes these two paradigms as expressing the same propositional meaning. The difference between the examples in the two paradigms is that in the former, the pronominal clitics indexing A are proclitics whereas in the latter paradigm they are enclitics. Riyahi points out that the occurrence of the clitics as enclitics, particularly with the plural forms, is lower in acceptability compared to their occurrence as proclitics.

To these paradigms, sentences (150) – (153), which I cite from Riyahi, can be added.Footnote 120 Examples (150)-(153) show that the clitic indexing A is mobile and that an adverb can be its host.

A very important question would be why the variations in (149) – (153) exist? Can these examples be considered as indications of the beginning of a reanalysis in pronominal clitics indexing A? If so, then one might aptly ask what triggers these variations? Are they triggered by a language internal force or they are triggered by a language external force, specifically interference due to language contact with the surrounding dialects? These are obviously promising avenues of research in this part of Khorasan. For now I reiterate my generalization about indexation of S and A as pronominal clitics in the past tense domain in the dialect of Se-Ghal’e: They are (mainly) grammaticalized as pronominal proclitics. I asked my consultant, Abbas Riyahi, whether the use of pronominal enclitics instead of pronominal proclitics in the above mentioned examples is attested in the speech of younger speakers or it is not a generatiolect. His response was that he does not feel it to be a recent development.

In the past tense domain, the use of O in the form of a pronominal clitic is not common. Examples (154) and (155) are the occurrences which I elicited from Riyahi.

The second pattern grammaticalized for the indexation of S and A in the past tense domain in Se-Ghal’e dialect is observed in their use as independent pronouns. As independent pronouns, the verb form of the sentence containing them is the bare past tense stem of the verb which remains constant for all persons. Paradigms (156) and (157) which I elicited from Riyahi substantiate this observation.

On the basis of the data presented in this subsection, it can be claimed that the dialect of Se-Ghal’e’s system of indexation is split. The splitness is sensitive to the category tense: present tense versus past tense (see type (iii)) in the introduction (Section 1). Furthermore, in the past tense domain, S, A, and O may be indexed by pronominal clitics. Thus the dialect of Se-Ghal’e allows a tri-oblique pattern.

3. The Historical Context

In this section, the evidence and findings which were presented and analyzed in the previous section will be discussed in a historical context. In this discussion, I will benefit from the data in Abdul Hai Habibi, Ali Ravaghi, and Jamal Rezaee.Footnote 121

Abdul Hai Habibi, an eminent Afghan scholar in Persian literature, in his edition of the Persian text Tabaqat-us-Sufiyah dictated by Shaykh-ul-Islam Khwajah Abdullah Ansari Herawi (circa 11th century A.D.) mentions that one of the peculiarities of Tabaqat by Herawi is that its language is archaic. Habibi adds (my translation):

“it [Tabaqat-us-Sufiyah] must be considered closer to the early era of the formation of the Dari language and the books which have remained from Al-e Saman era [namely 874 A.D. –999 A.D.]”Footnote 122

Habibi notes that a number of the Sufiyah books are written in a dialect which is close to the colloquial speech of the common people, avoiding literary and elevated style, in order to be understandable to their general audience.Footnote 123 Here I cite a few examples from Tabaqat which show the indexation system of that text.Footnote 124

‘They asked a generous youth with what he [lit.you] knew the truth? He said I knew it through it.’Footnote 125

In terms of indexation, the verbs goft-and, šenāḫt-ī, and goft-Ø have indexed their A by verbal agreement suffixes. In the last clause, the pronominal enclitic =m whose host is the O, ū ‘it’, indexes the A. The verbal form be-šnāḫt is the past tense stem form showing no agreement marking. Thus, in this example, the grammaticalization of verbal agreement suffixes as well as pronominal enclitic to index A is observed. Example (159) provides further information about the indexation in this text.

‘An old person was dying, they told him what wish do you have? He said before I pass away, a little bit of knowledge.’Footnote 126

In example (159), there are five occurrences of the verb as follows: mī-raft-Ø, goft-and, dār-ī, goft-Ø, be-rav-am. Three of them are formed with past stems and two with present stems. In all of them S (the first and last verb) and A are indexed by verbal agreement suffixes. Example (160) adds another piece of information to our elaboration on indexation marking in Tabaqat.

‘One year, I had gone for pilgrimage to Mecca, on my way I fell into a well, two persons passed over the well.’Footnote 127

Example (160) contains three clauses. In the verbs of the first two clauses, S is indexed by verbal agreement suffix. The S in none of these two clauses is overtly expressed. In the third clause, the S, namely do tan, is overtly expressed in the clause. The verb of this clause is a bare past tense stem with no agreement marking with its S, which is by the way a plural noun.

Rezaee after mentioning example (161) says that the subject of the embedded verb dīd ‘saw’ is a first person pronoun which is dropped.Footnote 128

In the matrix clause of example (161) the verb is in the present stem form and its A is indexed by verbal agreement suffix. Also noteworthy is example (162), which I quote from Rezaee.Footnote 130 In this example, the S which is man ‘I’ is overtly present and the verb shows no agreement with it. Rezaee explicitly mentions that na-bīd means na-būd-am, literally ‘not-was-I’, ‘I was not’.

In example (158), we encountered a clause (the final clause in that example) in which the A of a past tense verb is indexed by a pronominal enclitic. In this clause, the O is the enclitic host. Rezaee mentions that this kind of the occurrence of the subject is seen with transitive verbsFootnote 132 and since no intransitive verb indexing its subject in this way in Tabaqat-us-Sufiyah is observed, we can conclude that “this structure and conjugation in the old dialect of Herat just like Middle Persian was specific to transitive verbs.”Footnote 133 In example (163), the A of the embedded verb is indexed by a pronominal enclitic whose host is the IO.

Both Habibi and Rezaee explicitly express that the embedded sentence means ‘I gave you something’, namely the pronominal enclitic indexes the A.Footnote 135 In example (164), the complementizer ke is the host for the pronominal enclitic which indexes the A. HabibiFootnote 136 writes that k=om is the shortened form for ke=om. Both Habibi and Rezaee (1976: 102) have described this pronominal enclitic as the subject of the transitive verb biyāft ‘found’.Footnote 137

In example (165), the pronominal enclitic ot appears not to have a host, though historically it may be analyzed as o=t and consider the particle o as a clitic host particle.Footnote 139 Habibi and Rezaee have described this pronominal enclitic as the subject of the past tense stem of the verb ‘know’.Footnote 140

Earlier I quoted Rezaee who has claimed that the occurrence of the pronominal enclitics (in my terminology) to index subject in the old dialect of Herat just like Middle Persian was specific to transitive verbs.Footnote 142 Ali Ravaghi (1969 A.D.) states “in my study of a number of Persian texts I came across a structure with past tense verbs that was new to me.”Footnote 143 The structure which had attracted the attention of Ravaghi contains past tense verbs whose subjects are indexed by pronominal enclitics (using our terminology) in the verb. Example (166), which Ravaghi mentions that he cites it from Tarix-e Bæl’æmi (10th century A.D.), contains two pronominal enclitics. The first one indexes an S and the second one indexes an A.

In example (167), three past tense verbs are used. In the first verb the A is indexed by a verbal agreement suffix. In the last two verbs, which are intransitive, the S is indexed by a pronominal enclitic in the verb. Ravaghi points out that the example is cited from Tæfsir-e Abolfotuh-e Razi (13th century A.D.).

Example (168) is cited in Ravaghi from Tæzkeræt-ol-æwliya’ written by Attar Neyshaburi (13th and 14th century A.D.).Footnote 147 In this example, the first past tense verb has indexed the third singular form of its A by a verbal suffix. In the second verb which is an intransitive past tense form, the S is indexed by a pronominal enclitic in the copula.

In example (169), the first verb is an intransitive past tense verb and its S is indexed by a verbal agreement suffix for a third person singular. In the second verb, the same subject now serves as an A for a ditransitive past tense verb. In this verb, A is indexed by a pronominal enclitic. Ravaghi has quoted this example from Tarix-e Bæl’æmi (10th century A.D.) and has pointed out that this =aš form has been called “redundant =aš” and “subjective =aš” in previous traditional studies.Footnote 149

On the basis of the evidence from early New Persian era which I quoted from Ravaghi it seems just to claim that in some of those texts a pattern which indexes the S and A of past tense verbs by pronominal enclitics in the verb had been grammaticalized.Footnote 151 Looking at all the examples which were presented in this section, I propose that the generalizations which are listed in (170) characterize the indexation system of some of the early New Persian texts.

(170)

a. Early New Persian texts had grammaticalized a split indexation system which was sensitive to tense: past versus non-past.

b. In the non-past tense domain, S and A were indexed by verbal agreement suffixes.

c. In the past tense domain, two patterns had been grammaticalized as follows: (i) when S and A were overtly present (or textually recoverable), the verb would appear in its fixed past stem form showing no indexation. (ii) S and A could be indexed by pronominal enclitics.

d. There existed a default indexation pattern which allowed S and A irrespective of the tense of their verb to be indexed by verbal agreement suffixes.

The generalizations which I enumerated in (170) are fundamentally the same generalizations which I mentioned for the former dialect of Birjand in (24). Therefore, in terms of indexation, the former dialect of Birjand and some of the early New Persian texts behave similarly. Based on these observations, it is clear that there is continuity between the structural behavior of some of the early New Persian texts and the dialect of Birjand in early 20th century.

If we evaluate the dialect of Ferdows (Section 2.2), the dialect of Khanik (Section 2.3), and the dialect of Se-Ghal’e (Section 2.4) in the historical context of some of the early New Persian texts, the generalizations in (171) will result.

(171)

a. The dialects of Ferdows, Khanik, and Se-Ghal’e have preserved a rigid split indexation system which is merely tense-sensitive, namely type (iii) as summarized in the introduction (Section 1). This system is currently productive in the speech of the residents of Ferdows, Khanik, and Se-Ghal’e.

b. The dialects of Ferdows, Khanik, and Se-Ghal’e are more archaic than the dialect(s) of those early New Persian texts whose examples were presented and discussed in the present subsection. Where they stand with respect to the Western Middle Iranian remains to be pursued in future research.

c. The pronominal clitics which index S and A in the past tense domain are proclitics in the former dialect of Birjand (see Section 2.1) and in the present-day dialect of Se-Ghal’e (see Section 2.4) but they are enclitics in the dialect of Ferdows (Section 2.2) and the dialect of Khanik (Section 2.3). In Section (3), examples quoted from early New Persian texts show that these pronominal clitics when used are enclitics. Further investigation is required to account for this dual grammaticalization of the indexation of S and A in the past tense domain.

4. Restructuring in the dialect of Birjand

Towards the end of my description and analysis of the data from the former dialect of Birjand, I summarized the findings in (24)a-d. These are the generalizations which capture the state-of-the-art of indexation in this dialect in the first decade of the 20th century. In this section, I will explore the factors which seem to have been responsible for the restructuring of the indexation of this dialect into a uniformly Nominative-Accusative type.

Rezaee published a valuable book entitled Birjand-Nameh ‘The Book of Birjand’ which describes Birjand as it was at the beginning of the 20th century.Footnote 152 This book is indeed a rich encyclopedia of Birjand in early 20th century. The book was published posthumously, about one year after Dr. Jamal Rezaee had passed away. In Birjand-Nameh, I found interesting information which shed light on the rapid linguistic restructuring I am concerned with. In Birjand-Nameh, it is explicitly announced that “the final decades of the 13th century [Islamic calendar, namely early 20th century] and the beginning decades of the 14th century [Islamic calendar] must be considered as the development period and the turning point of the change of this dialect.”Footnote 153 There were a number of external factors which, in my opinion, explain that rapid linguistic restructuring. Those factors, I have enumerated in (172) below:

(172)

a. In the 19th century A.D. when Birjand became the ruling center of Gha’enat area with a local ruler, the population of Birjand doubled or even tripled due to “migration of villagers from surrounding villages and regions to Birjand.”Footnote 154 The population of Birjand before it was chosen as the center of Gha’enat is estimated to have not been more than five thousand inhabitants. Birjand at that time was a big village and was officially a district. This population after the above-mentioned migration is estimated to have increased to around fifteen thousand inhabitantsFootnote 155 Rezaee makes it clear that the migration was from the surrounding villages and the villages of Gha’enat, namely they were all from Ghohestan area. J. Rezaee says “this point was one of the most important racial features of the people of Birjand.”Footnote 156 The villagers who had migrated to Birjand could be easily recognized from their names because the name of their birthplace was included in their name; furthermore, their dialect, their accent, and even their dress and way of life were distinct.Footnote 157 At that period, the inhabitants of sar-e deh (lit. upper village) and tah-e deh (lit. lower village) had little interaction with each other and that separation was reflected in their accent. deh in those combinations refers to Birjand.Footnote 158 Rezaee mentions that those dialectal differences were gradually leveled out which led to a relatively uniform dialect.Footnote 159 Rezaee describes the dialect of Birjand as a “pure” dialect because at the beginning of the 20th century, the lexicon of this dialect was “devoid of foreign words.”Footnote 160 In his words, “in the lexicon of the dialect of Birjand, the number of foreign words such as Arabic words, Turkish words, and Mongolian words, and … compared to the number of these words in standard Persian and some of the dialects of big cities is much fewer.”Footnote 161 The fact that Birjand was close to the desert and was located in a mountainous area and was not a very rich and flourishing territory, it had historically remained relatively immune of foreign invasions.Footnote 162 Thus, historically Birjand had remained in isolation, it was a language island.

b. The period which is described in Birjand-Nameh coincides with the fall of the Qajar dynasty and the beginning of Reza Shah of Pahlavi’s reign. Rezaee writes:

“I have limited my research to Birjand at the beginning of the 14th century [Islamic calendar] because at that era with the change of the monarchy, the administrative system of the country changed and the local rulers were replaced by the governors [assigned by the central government] and the governmental offices undertook the local affairs.”Footnote 163

c. The geographical situation of Birjand in the time period which is described in Birjand-Nameh and a few years before and after had become “strategically and commercially highly important.”Footnote 164 Rezaee cites a number of sources which have mentioned the important role which Birjand had played in the transportation of goods and supplies during the first and the Second World War. As Birjand is located in the middle way between Zahedan and Mashhad, the only commercial ground road linking Iran and India (more specifically Quetta which was then part of India) used to pass through Birjand. In Rezaee’s words, “all the goods which were imported from India to Iran or were exported from Iran to India used to enter or dispatch from this city and “the city” had an extraordinary commercial briskness.”Footnote 165

d. Due to the commercial importance that Birjand had gained in the final decades of the 19th century and the early 20th century, the governments of Britain and Russia each had established a consulate and a bank in this city. The Russian consulate and bank ceased its activities after the 1917 Soviet revolution. Also a number of Indian merchants as well as merchants from cities such as Mashhad, Yazd, Isfahan, Shahrud, and Kerman were doing trade in Birjand.Footnote 166

e. Birjand was among the pioneering cities in establishing modern schools in Iran. The first elementary school for boys was established in 1905 and the first elementary school for girls was founded in 1922. Within a decade after that a high school for boys and an intermediate school for girls were established. The schools were founded and funded by Mohammad Ebrahim-Khan-e A’lam known as Showkatolmolk. Hence, they were called Showkatieh. These schools and later established governmental schools proved to be academically very well-known. A long list of highly educated scholars received their pre-university education in these schools.Footnote 167

I suggest that the factors listed in (172) a-e were crucial external factors which jointly led to simplification of the grammar of the dialect of Birjand -- more specifically the growing influence of Standard Persian as the language of education, commerce, and administration. The linguistic complexities that the dialect of Birjand had carried from the past era and had preserved in isolation were simplified in the contact period of the last decade of the 19th century and the first decade of the 20th century. The reduction of the four grammaticalized patterns listed in (24)a-d to index S and A in the former dialect of Birjand and more specifically the restructuring of those patterns into a uniformly Nominative-Accusative pattern was the outcome of the mentioned simplification.

5. Summary and discussion

In the introduction of this paper (Section 1), I first mentioned three types of splitness in the Iranian languages: (i) a type whose splitness is sensitive to aspect and transitivity, (ii) a type whose splitness is sensitive to tense and transitivity, and (iii) a type whose splitness is sensitive to tense only. In Section 2, entitled “The Survey”, I provided a linguistic description and analysis of the alignment peculiarities of four Iranian dialects spoken in Khorasan in separate subsections. These are the former dialect of Birjand (Section 2.1), the present-day dialect of Ferdows (Section 2.2), the present-day dialect of Khanik (Section 2.3), and the present-day dialect of Se-Ghal’e (Section 2.4). What these dialects have in common is that the splitness of their alignment systems is only tense-sensitive (namely type (iii) above). This type, I have not found elsewhere in Iran. In Section 3, the evidence and findings reported in Section 2 were put in a historical context. It was shown that some of the early New Persian texts contain all of the typological peculiarities which were enumerated in Section 2. Discovery of this continuity of the alignments reveals the importance of the study of currently spoken dialects for our understanding of the developments and changes in the Iranian languages of Iran; namely what synchrony reveals about diachrony. In Section 4, attempts were made to bring to light the external factors which seem to have been influential in the restructuring of the four patterns of alignment which were observed with respect to the former dialect of Birjand (the patterns listed under (24)). This restructuring resulted in the grammaticalization of a uniform Nominative-Accusative type as is observed in the present-day dialect of Birjand. The restructuring led to a single system of alignment, hence it can be evaluated as an instance of linguistic simplification. The fact that the present-day dialects of Ferdows, Khanik, and Se-Ghal’e have still preserved their tense-sensitive splitness alignment and that the patterns they have grammaticalized in this respect (see the generalizations in (68)a-c) show a stage more archaic than the classical Persian data discussed in Section 3 once again highlights the importance of the local languages and dialects to understand and reconstruct the earlier stages of a group of related languages and dialects.

A lesson we may learn from the historical continuity in the preservation of the alignment in Khorasan is that geographical and socio-cultural isolation lead to linguistic complexity, in our case the grammaticalization of four alignment patterns in one dialect for instance (see the generalizations in (24)). Another lesson we may learn is that, the co-occurrence of a number of external factors can contribute to a restructuring which yields a simple and general alignment (see Section 4). With the formation of new external forces (e.g. mass media, public education, internet, social mobility), similar developments and restructuring in the case of the dialects of Ferdows, Khanik, and Se-Ghal’e appear to be inevitable.

A final point to unravel in future research is that why the type (iii) which shows a tense-sensitive alignment is a rarity in Western Iranian languages and is limited to Khorasan. For now, I simply bring to attention the following remarks.

Alice Harris (2008) in a chapter entitled “On the Explanation of Typologically Unusual Structures” has paid particular attention to Georgian Split Case Marking. She reports

“the subjects of active intransitives (unergatives) are marked like subjects of transitives, with the narrative case, while subjects of inactive intransitives (unaccusatives) are marked like direct objects, with the nominative case.”Footnote 168

Harris has made it clear that “narrative case [is] (also known as the ergative case).”Footnote 169 In the cited quotation the identical ergative case marking of the S of a group of verbs and that of A is brought to attention as an instance of rarity. What interests me more are the explanations which Harris discusses for the rarity of a linguistic structure. The first explanation is quoted from Joseph Greenberg and the second explanation is Harris’s own explanation. Greenberg said

“In general one may expect that certain phenomena are widespread in language because the ways they can arise are frequent and their stability, once they occur, is high. A rare or non-existent phenomenon arises only by infrequently occurring changes and is unstable once it comes into existence.”Footnote 170

Harris’s account of linguistic rarity is different. In her words:

“My explanation does not rely on appeal to infrequency of changes or instability of constructions. Rather, it assumes that the changes that produce the structure are common, it is only the combination that is uncommon, simply because it requires so many different steps or conditions … . My explanation makes the predictions that structures that develop in a single step, other things being equal, will be common among languages of the world, while those that require a large number of steps will be rare.”Footnote 171

With regard to the rare and unusual alignment that was described and analyzed in Section 2 of this paper, I propose that the indexation of S by a pronominal clitic is an additional step, namely the adoption of past tense transitive pattern of indexation by past tense intransitive verbs, which has led to an unusual and rare alignment within Iranian languages.